Significance

The evolution of differentiated sex chromosomes has been intensively studied over many decades to address questions, not only about the sex-determining mechanism, but also on the genetic changes to sex chromosomes. A crucial question concerns sex chromosome turnover, whereby a novel sex gene defines a new pair of sex chromosomes, leading to rapid degradation of the sex-specific element. Mammals possess an extremely stable XY chromosome system, in which the Y has almost completely degraded. Exceptional mammals that have recently lost this degraded Y are of unique value for studies of the process of sex chromosome turnover in mammals. Our findings open the way to investigating Y-loss and the earliest evolutionary changes that repurposed an autosome into a new sex chromosome.

Keywords: sex determination, Y chromosome, XO, cis element

Abstract

Mammalian sex chromosomes are highly conserved, and sex is determined by SRY on the Y chromosome. Two exceptional rodent groups in which some species lack a Y chromosome and Sry offer insights into how novel sex genes can arise and replace Sry, leading to sex chromosome turnover. However, intensive study over three decades has failed to reveal the identity of novel sex genes in either of these lineages. We here report our discovery of a male-specific duplication of an enhancer of Sox9 in the Amami spiny rat Tokudaia osimensis, in which males and females have only a single X chromosome (XO/XO) and the Y chromosome and Sry are completely lost. We performed a comprehensive survey to detect sex-specific genomic regions in the spiny rat. Sex-related genomic differences were limited to a male-specific duplication of a 17-kb unit located 430 kb upstream of Sox9 on an autosome. Hi-C analysis using male spiny rat cells showed the duplicated region has potential chromatin interaction with Sox9. The duplicated unit harbored a 1,262-bp element homologous to mouse enhancer 14 (Enh14), a candidate Sox9 enhancer that is functionally redundant in mice. Transgenic reporter mice showed that the spiny rat Enh14 can function as an embryonic testis enhancer in mice. Embryonic gonads of XX mice in which Enh14 was replaced by the duplicated spiny rat Enh14 showed increased Sox9 expression and decreased Foxl2 expression. We propose that male-specific duplication of this Sox9 enhancer substituted for Sry function, defining a novel Y chromosome in the spiny rat.

Mammals typically have a very stable XY sex chromosome system in which the SRY gene on the degenerate Y chromosome triggers testis differentiation. SRY up-regulates SOX9 expression in undifferentiated embryonic gonads, resulting in supporting cell differentiation into Sertoli cells (1). This mechanism is almost ubiquitous in therian mammals (marsupials and placental mammals).

However, there are a few exceptional rodent lineages in which the Y chromosome, and Sry have been lost (2–5). This means testis differentiation must proceed without Sry, and raises questions about the identity of the genetic trigger that can up-regulate Sox9 expression. Searches for this trigger over three decades have been unsuccessful.

The Amami spiny rat (Tokudaia osimensis, Muridae, Rodentia) lacks a Y chromosome (2n = 25, XO/XO) and Sry is completely absent (2, 3, 6), which means that it has evolved a new sex-determining mechanism independent of Sry. The genus Tokudaia includes three species, each indigenous to only a single island in southernmost Japan. The Amami spiny rat lives on the Amami-Oshima island, which is one of the islands of the Ryukyu archipelago. In this species, Sox9 is highly expressed in the testis and downstream factors that encode sex differences are conserved (7, 8). Males and females show no obvious cytogenetic differences by G-banding, R-banding, or comparative genomic hybridization (9, 10), indicating that sex is determined by a cytologically cryptic, probably tiny, sex-specific chromosomal region. Although this species is endangered and heavily protected (11), and therefore presents many challenges for genetic study, the Amami spiny rat represents a unique opportunity to explore mammalian sex chromosome evolution.

The regulation of SOX9 by SRY has been intensively studied in mice and humans. XX transgenic mouse ectopically expressed Sox9 shows female-to-male sex reversal (12), suggesting that increased Sox9 expression can determine testis in the absence of Sry. In addition to sex-determination, SOX9 has a wide range of functions at various developmental stages (13), being expressed in various cell types in many tissues, so it is not surprising that the regulatory region is highly complex. Several cis-regulatory regions are spread over a gene desert of >2 Mb upstream of the SOX9-coding sequence (14). In humans, patients with disorders of sex development (DSD) have been reported who have a complete SOX9-coding sequence but mutations in the upstream region. Copy number variations (CNVs) mapping in the genome of DSD patients with SRY-positive 46, XY identify a 32.5-kb region located 600 kb upstream of SOX9, called XYSR (15). Subsequent analysis with DSD patients carrying CNVs refined this to a small 5.2-kb region (16). Additionally, a 68-kb region ~600 kb upstream of SOX9 called XXSR (also known as RevSex) was identified by screening of CNVs in the DSD patients with SRY-negative 46, XX (15, 17) and further refined to 24 kb (16). Thus several upstream enhancers are essential for SOX9 activation in early male gonads. By screening of additional patient genome and bioinformatic analysis, three putative enhancers have been identified: eSR-A in XYSR, eSR-B in RevSex, and eALDI (17). All three enhancers have shown synergistic activity in cell-based reporter assay with different combinations of testis-specific regulators including SRY, SF1 (also known as NR5A1), and SOX9.

In mice, a 3.2-kb element located 13 kb upstream of Sox9 was first identified as an enhancer that controlled the gonad-specific expression of Sox9. This element was termed Testis-specific Enhancer (for TES of Sox9) and its conserved 1.4-kb core was termed TESCO (for TES COre element) (18). TESCO contains the binding sites of SRY, SOX9, SF1, and several other transcription factors known to have roles in sex determination or to maintain the Sertoli cells. Genetic studies suggest that TES/TESCO plays a major role in integrating both transcriptional activation and repression of Sox9 (19). Although targeted deletion of TES or TESCO reduced Sox9 expression levels in XY fetal gonads relative to wild-type gonads, sex reversal was not observed in either TESCO- or TES-deleted XY embryos or adult mice (20). By further screening based on chromatin accessibility screening methods, a 557-bp element (termed Enh13) located on the 565 kb upstream was identified in the region homologous to human XYSR. Knockout experiments provided evidence that Enh13 is an essential enhancer for the initiation of testis development (21). By comparisons of genome conservation among mammalian species, the orthologous region was identified as mXYSRa (22).

In the Amami spiny rats, there is evidence that other enhancers besides TESCO can act as TES of Sox9 (7). TESCO sequence is highly conserved in the spiny rat (83% identity with mouse TESCO), but nucleotide substitution(s) were found in two of three SRY-binding sites and in five of six SF1-binding sites. TESCO showed low enhancer activity in a reporter gene assay.

In the absence of a cytological marker that differentiates male and female spiny rats, molecular studies must be used to identify sex-specific sequences. We therefore sequenced the spiny rat genome and performed a mapping-based analysis to extract single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and CNVs that are specific to one sex. No sex-specific SNPs were identified, but we found, by CNV screening, a single sex-related genomic difference in a male-specific duplication of a 17-kb unit located 430 kb upstream of Sox9 on the short arm of chromosome 3. The duplicated unit contains a 1,262-bp element homologous to mouse Enh14. In vivo reporter assay showed that the spiny rat Enh14 drives Sox9 expression in embryonic gonads of XY mice, and embryonic gonads of XX mice in which Enh14 was replaced by the duplicated spiny rat Enh14 showed increased Sox9 expression and decreased Foxl2 expression. This suggests that the new sex-determining element in the spiny rat consists of a male-specific duplication of a cis-element that up-regulates Sox9 in the absence of Sry.

Results

Male-Specific Duplication Upstream of Sox9.

We generated a de novo assembly based on paired-end and mate-pair sequence reads for a male Amami spiny rat, resulting in a draft genome with an N50 of 11 Mbp and a size of 2.4 Gbp (SI Appendix, Table S1).

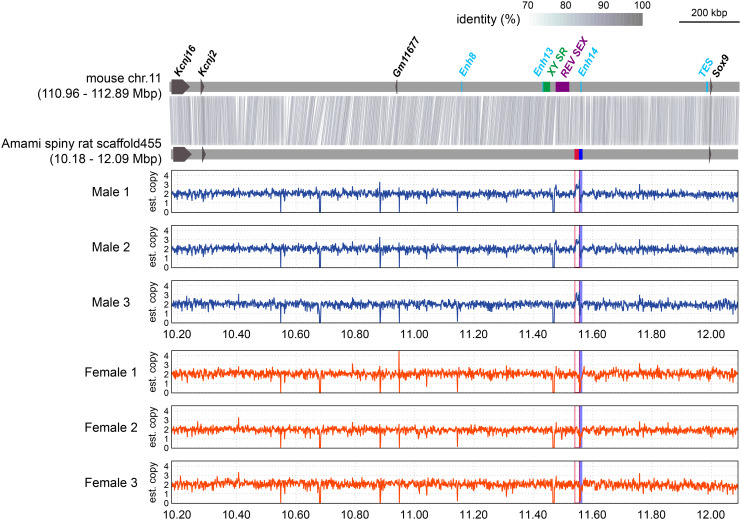

To identify genomic differences between sexes, we performed resequencing of six individuals (three individuals per sex; two other males and three females). Based on read mapping, we identified 83,451 candidate sex-associated SNPs. The top five high-density SNP regions were further examined using additional three males and three females (SI Appendix, Table S2), but did not show sex specificity. Next, based on 10-kbp windows, we identified 41 candidate sex-associated CNV regions (SI Appendix, Table S3). Of these, 39 CNV regions did not show sex differences when tested in the other animals. The remaining two were both on scaffold455, which was located 430 kb upstream of Sox9 on the short arm of chromosome 3. They were adjacent but showed a copy number difference (Fig. 1). No sex differences were observed on the X chromosome.

Fig. 1.

Alignment of the region upstream of Sox9 in mouse and Amami spiny rat (T. osimensis) genomes and estimated copy number distributions of three males and three females. The region at 10.18–12.09 Mb on scaffold 455 constructed from the male spiny rat genome is shown. Thick horizontal gray lines indicate upstream sequences of Sox9 in the mouse and spiny rat. Colored squares on the mouse genome indicate reported enhancers and genomic regions associated with human DSD or with gonadal differentiation in the mouse. Red and blue on the Amami spiny rat genome indicate sex-specific CNVs (SI Appendix, Table S3). Histograms show the distributions of estimated copy numbers from paired-end reads in male and female individuals.

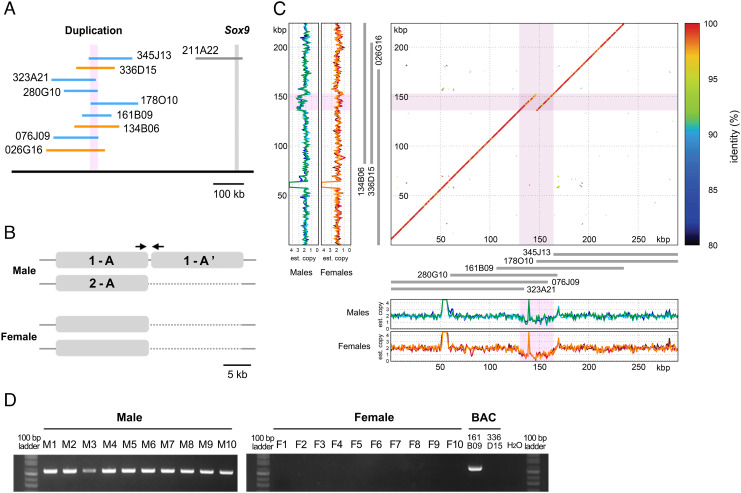

To determine the detailed haplotype structure, we screened and sequenced nine bacterial artificial chromosomes (BACs) that covered these CNV regions and derived from the same male sample, using the de novo assembly (Fig. 2A). The duplication consisted of an approximately 17-kb unit with pairwise sequence identities of 94.6 to 97.6% (Fig. 2B and SI Appendix, Table S4). All BACs were localized to the short arm of chromosome 3 of the spiny rat by FISH mapping (SI Appendix, Fig. S1), near to the location of Sox9 (7).

Fig. 2.

Male-specific duplication revealed by BAC sequencing. (A) Locations of BACs upstream of Sox9 containing duplications (345J13, 323A21, 280G10, 178O10, 161B09, and 076J09 shown in blue), no duplication (336D15, 134B06, and 026G16 shown in orange), and the Sox9 CDS (211A22 shown in gray). (B) Haplotype of CNV regions in male and female spiny rats. Identities between each unit (1-A, 1-A′, and 2-A) are shown in SI Appendix, Table S4. Arrows indicate primer locations for PCR in (D). (C) Dot-plot alignment of alleles upstream of Sox9 and histograms of estimated copy numbers in males and females. Axes on the dot-plot indicate the two alleles. Pink represents the duplication in the sequence constructed from male BAC clones. Histograms on the Left and Bottom show copy numbers estimated from paired-end reads in three males and three females. Gray lines between the dot-plot and the histogram show the layout of the screened BACs. (D) PCR amplification using primers at the boundary of the duplication. Genomic DNAs of ten males (M1–M10) and ten females (F1–F10) and two BAC clones with (161B09) and without the duplication (336D15) were used as templates. A 100-bp ladder marker is shown.

The BAC sequences were of two types, with and without a tandem duplication. The duplication was absent from the genomes of all three females but present in all three males (Fig. 2C), as only one allele of the male genome. We designed a pair of primers to span the boundary of the duplication unit (Fig. 2B). Amplification was observed only in males confirming that this duplication is male-specific in the spiny rat (Fig. 2D).

The Duplicated Region is Located on Sox9 Topologically Associated Domains (TAD).

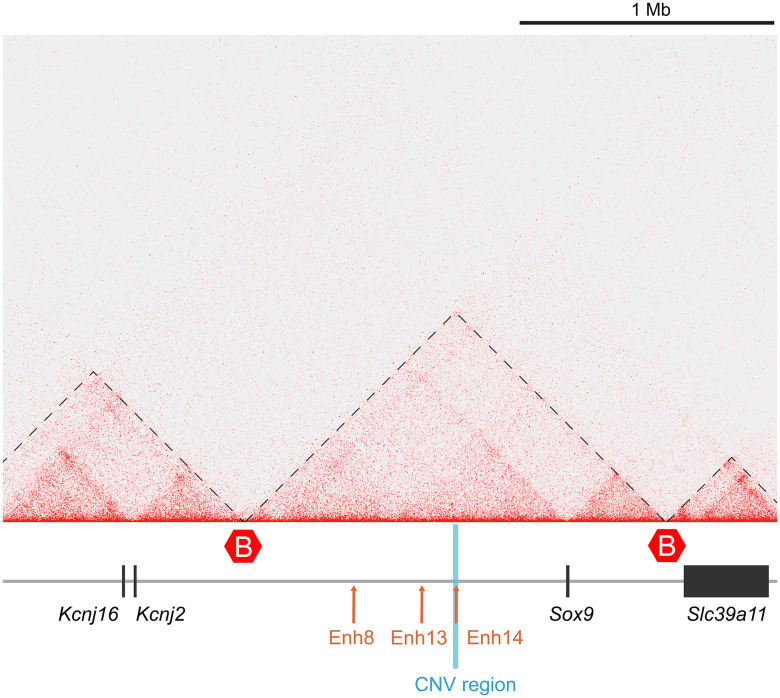

We hypothesized that the duplicated region is involved in Sox9 regulation in the Amami spiny rat cells. To test this possibility, we performed Hi-C analysis using male spiny rat cells to examine the chromatin conformation of this region. Because tissues of this endangered species are not available, we used cultured fibroblast cells for Hi-C analysis of the region upstream of Sox9 bordered by adjacent gene Kcnj2, which has a distinct expression pattern. Hi-C analysis showed that the Sox9-Kcnj2 region is divided in two TADs (Sox9 TAD and Kcn2j TAD), whose boundary is located approximately 1.3 Mb upstream of Sox9 (Fig. 3). This is consistent with the relationship of SOX9 and KCN2J TADS in human fibroblast cells to analyze DSD, ES cells, and mouse limb buds (23, 24). In the spiny rat, the duplicated region was included in the Sox9 TAD, suggesting that it has the potential to make chromatin interaction with the Sox9 gene.

Fig. 3.

TAD configuration at the Sox9 locus in male spiny rat cells. Hi-C from male cells with boundaries are indicated by B in red hexagons. The Sox9-Kcnj2 region locus is divided into two TADs, one containing Sox9 (Sox9 TAD) and the other containing Kcnj2 (Kcnj2 TAD). CNV that identifies the male-specific duplicated region (blue line) is included in the Sox9 TAD. Arrows represent known enhancers involved in gonadal differentiation (orange), and Enh14 is located on the duplication unit.

The duplicated region corresponded to the location of mouse Enh14 (Fig. 1), a putative Sox9 enhancer (21). In previous studies, the mouse Enh14 showed robust testis-specific β-Gal activity, and DNaseI-seq, ATAC-seq, and H3K27ac ChIP-seq data all suggested that this enhancer is active and open only in Sertoli cells (21). However, Enh14 deletion did not alter Sox9 expression in E13.5 XY gonads, indicating that Enh14 may either control Sox9 expression during a different developmental time window, and/or function redundantly to Enh13 and/or TES (21, 25). The sequence identity between mouse Enh14 (mEnh14, 1,288 bp) and spiny rat Enh14 (tosEnh14, 1,262 bp) was 87.7% (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). Although Enh13 and Enh8 (which is considered to be an intrinsic ovary-specific enhancer, 21) were also conserved in the spiny rat (identities are 90.0% and 86.6%, respectively), these enhancers were not located in the duplicated region (Fig. 1).

Duplication of Enh14 Affects Early Sox9 Expression in Embryonic Testis.

We hypothesized that the duplication of tosEnh14 increases Sox9 expression in the spiny rat. Since it is not possible to obtain tissues from the endangered spiny rat, we performed functional analyses using transgenic and gene-edited mice.

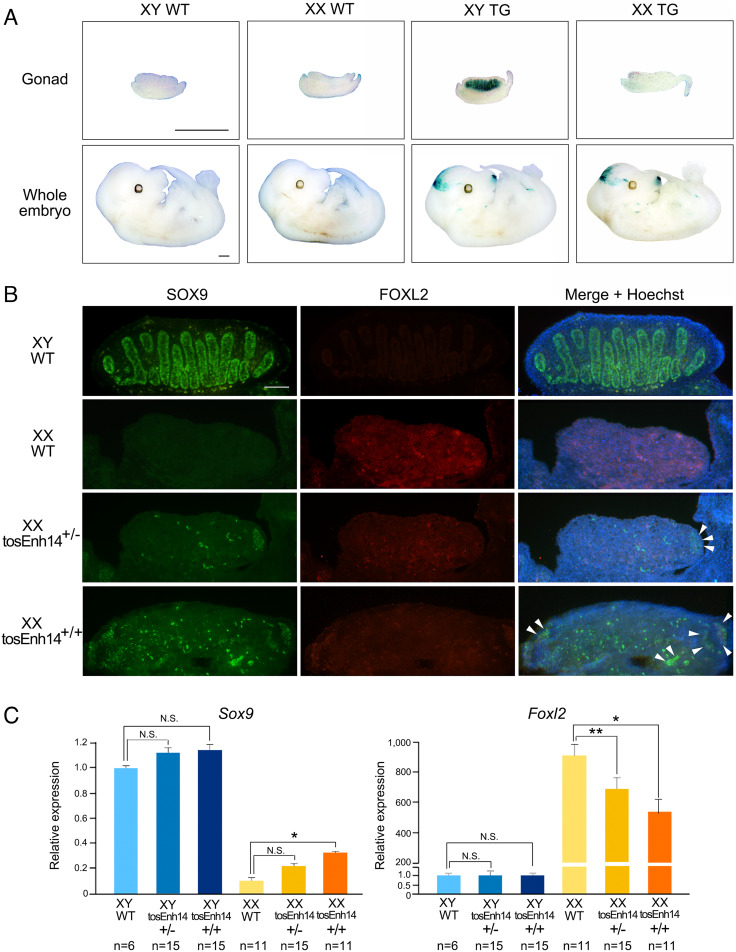

To assess enhancer activity in embryonic gonads, two fragments of tosEnh14 were cloned upstream of the Sox9 promoter with the reporter gene lacZ to generate transgenic mice. We obtained seven transgenic XX and eleven transgenic XY embryos at E13.5. XY transgenic embryos showed robust β-Gal activity in the testis (Fig. 4A), with a staining pattern similar to that of mEnh14 (21), suggesting that tosEnh14 can function as a spontaneous gonadal Sox9 enhancer in mice.

Fig. 4.

tosEnh14 is proposed to be a testis-positive enhancer. (A) X-gal staining (blue) of E13.5 testes, ovaries, and whole embryos of wild-type and transgenic mice carrying tosEnh14. The staining was observed in the testis of XY, snout, and brain of XX and XY embryos. (Scale bars, 1 mm.) (B) Immunostaining of E13.5 gonads in XY wild-type, XX wild-type, XX tosEnh14+/−, and XX tosEnh14+/+ mice for the Sertoli marker SOX9 (green), granulosa marker FOXL2 (red), and Hoechst (blue). Overall staining of the male marker SOX9 increases, and the female marker FOXL2 decreases in gonads from mice with tosEnh14 sequences. Arrowheads indicate a small structure of SOX9-postive cells. (Scale bar, 100 µm.) (C) Real-time quantitative RT-PCR of Sox9 and Foxl2 in E13.5 gonads of XY wild-type, XX wild-type, XX tosEnh14+/−, and XX tosEnh14+/+ mice. Data are presented as mean 2−ΔΔCt values and SEM, normalized to Tbp. *P < 0.01, **P < 0.05 (unpaired, two-tailed t test on 2−ΔΔCt values). N.S., no significance.

To examine the regulatory effects of the duplicated enhancer on Sox9 in mouse, mEnh14 was replaced with a duplicated tosEnh14 by genome editing (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). No signs of masculinization in external and internal genitalia were observed for adult XX tosEnh14+/+ mice (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 A–C and Table S5). Nor did we detect anatomical differences between adult ovaries of XX wild-type and XX tosEnh14+/+ mice based on HE-stained sections (SI Appendix, Fig. S4 D and E). However, we did detect changes in the expression of Sox9 and Foxl2 in mouse embryonic gonads by immunofluorescence staining and real-time qPCR (Fig. 4 B and C). The gonads of XY wild-type mice showed SOX9-positive cells at E13.5, which formed the seminiferous tubules. XX wild-type gonads exhibited FOXL2-positive cells (Fig. 4B). In XX tosEnh14+/− and tosEnh14+/+ gonads, small structures formed by SOX9-positive cells were observed, and FOXL2 signals were weaker than those in XX wild-type gonads. Analysis of real-time qPCR showed that Sox9 expression was higher in XX tosEnh14+/− and tosEnh14+/+ than in XX wild-type gonads (Fig. 4C). The absence of Sertoli differentiation and testicular development is explained by the lower Sox9 expression in tosEnh14+/− and tosEnh14+/+ gonads (23% and 33% of that in XY wild-type gonads), which is below the threshold (45% of normal) that is sufficient for sex reversal in mice (20).

Together, the results suggest that tosEnh14 can regulate Sox9 expression in embryonic gonads, acting as a TES in mouse embryos. The failure of duplicated tosEnh14 to cause sex reversal of adult XX mice is likely to reflect species differences between the Sry-dependent mouse and Sry-independent spiny rat. Bolstering of the effect of the enhancer duplication on Sox9 expression would be expected during the evolution of a robust new sex-determining system in the spiny rat.

Another possibility is that there are enhancers in the 17-kb unit other than tosEnh14 that support and maintain Sox9 expression. A broader analysis of the 17-kb unit may reveal other regulatory regions responsible for sex determination.

Discussion

Sex chromosomes are defined by the possession of a sex-determining gene such as the Y borne SRY in mammals, and the dosage dependent Z-borne DMRT1 in birds. Sex chromosomes diverged rapidly in many lineages, following a common pattern of loss of recombination and degradation of the sex-specific partner (the Y chromosome in XY male systems and the W chromosome in ZW female systems). The first steps of this progress are of considerable interest.

Sex chromosome turnover is frequent in some vertebrate lineages. In fishes, various sex-determining factors have evolved, with frequent sex chromosome turnover. For example, several turnovers have occurred within the last few million years in Oryzias species, including a transposition of an active copy of Dmrt1 in the medaka, and sex-specific mutations in a cis-regulatory element that drives sex-specific Sox3 expression Oryzias dancena (26).

However, mammals and birds have remarkably stable sex chromosome systems. Placental mammals have a highly conserved sex chromosome system with XY males and XX females. The X chromosome is entirely conserved among mammals and relates to an orthologous autosome in other vertebrates. The Y is substantially degraded as a result of the high mutation rate in the testis, and the lack of recombination with the X. Testis differentiation is initiated by the Y-borne SRY gene, which up-regulates its autosomal target, the related SOX9 gene, at the beginning of a highly conserved biochemical pathway. There is no evidence for sex chromosome turnover in the 150-My evolutionary history of placental mammals.

However, a few rodent species with atypical sex chromosomes have been described, which reveal a recent sex chromosome turnover. These include Ellobius species with XO males and females, or XX males and females (4, 5). However, decades of investigation of these aberrant systems have yielded no information on the identity of the new sex-determining mechanism that is independent of Sry.

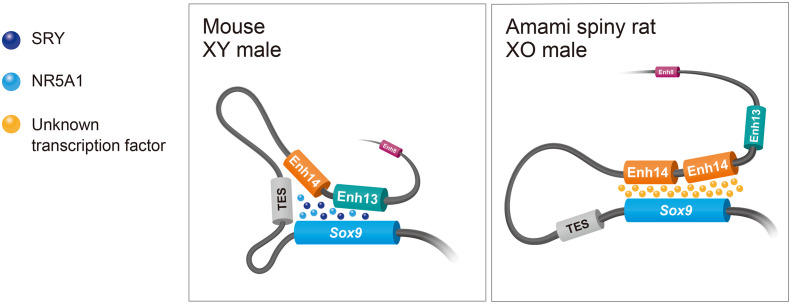

Our studies of the Amami spiny rat, with XO males and females and lacking a Y chromosome and Sry, have at last identified a tiny male-specific change in sequences that regulate Sox9. We found that the sex difference in the spiny rat genome was limited to the presence or absence of a 17-kb tandem duplication on chromosome 3. The repeated unit contains a cis-regulatory element that affects the activity of Sox9. We propose that this sequence change is responsible for upregulating Sox9 in the absence of Sry, and has become the new sex determiner in the spiny rat (Fig. 5). This new sex-determining sequence defines new sex chromosomes, which are still in their earliest evolutionary stages, showing minimal change from the original autosome, chromosome 3.

Fig. 5.

Schematic model of sex determination via a cis-regulatory element in a mammal lacking Sry, the Amami spiny rat. In mice, Enh13 has a critical role in the regulation of Sox9 by binding of the SRY and NR5A1 proteins. The other enhancers, TES and Enh14, may function as shadow enhancers with redundant functions. However, Enh13 and TES do not contribute to Sox9 regulation in the spiny rat lacking Sry. In individuals carrying the duplication upstream Sox9, Sox9 is up-regulated by binding unknown transcription factors to the two copies of Enh14, and Sertoli cells are differentiated (XO, male). This model is based on a mouse model of the regulatory landscape of Sox9 gene (25).

Thus genome information is nearly identical in the two sexes, except for the duplication upstream of Sox9. It may seem extraordinary that such a major evolutionary shift in the spiny rat should be sheeted home to such a tiny genome alteration. However, we know that many other processes required for sex determination, male differentiation and fertility, are directed by genes on other chromosomes, which are still present in the spiny rat. These include several genes from the discarded Y that were translocated to the X chromosome and are expressed in male and female gonads, and contribute to spermatogenesis (27, 28). These genes include Eif2s3y, which, along with Sry, is sufficient to generate germ cells and live progeny in mice (29). Our findings also support a previous report that induced pluripotent stem cells of the female Amami spiny rat not only contribute to the female germline in interspecific mouse ovaries but also differentiate into spermatocytes and spermatids that survive in adult interspecific mouse testes (30).

These results provide direct evidence for the sex chromosome turnover in mammals, in which the sex-determining region was moved to an autosome. With the identification of chromosome 3 as the site of the new sex-determining element, it will now be possible to investigate the first changes – genetic and epigenetic – that differentiate the neo X and Y chromosomes.

Materials and Methods

Animals and DNA Extraction.

The Amami spiny rat (T. osimensis) is endangered (The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species, DOI: e. T21973A22409638), and has been protected by the Japanese government as a natural monument and national endangered species of wild fauna and flora since 1972 and 2016, respectively. With permission from the Agency for Cultural Affairs and the Ministry of the Environment in Japan, all animals were released at their capture sites after a small piece was cut from the tip of their tail. DNA was extracted from the fibroblast cells cultured from tail tissues as reported previously (9). All animal experiments using the Amami spiny rat were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of National University Corporation, Hokkaido University, and were performed in accordance with the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals issued by Hokkaido University.

Hybrid F1 C57BL/6 X DBA/2 (B6D2F1), C57BL/6, and ICR mice were used to create genome-edited mice and Tg embryos. All mice were purchased from a local vender (Sankyo Labo Service Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Animal protocols were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the National Research Institute for Child Health and Development. All experiments using mice were conducted in accordance with approved animal protocols.

Comprehensive Survey of Sex-Specific Genomic Regions in the Amami Spiny Rat.

We performed whole genome sequencing assembly, de novo genome assembly, SNP analysis, and CNV analysis to detect the sex-specific genomic region in the spiny rat. Detailed methods are described in Supplementary text.

BAC Assembly.

Screening of BAC clones and sequencing are described in SI Appendix, Supplementary text. R-banded chromosome preparation and BAC FISH mapping were performed as previously described (7, 31).

Hi-C Analysis.

Hi-C library was constructed from the fibroblast-cultured cells using the Dovetail Omni-C Kit according to the product's standard protocol. The prepared Hi-C sample was sequenced (150-bp pair-end, NovaSeq 6,000) using Illumina technology. First, a raw count map was created using the Juicer pipeline (v1.6) (32). In the pipeline, raw reads were mapped to the whole draft genome using BWA (v0.7.17) (33). Then, a 5-kb resolution contact map was generated using Juicer tools (v1.22.01) (32) only for scaffold 455 (where Sox9 is located) from read- pairs with mapping quality (MAPQ) ≥30, normalized with Knight and Ruiz matrix balancing (32, 34, 35). TADs were predicted from the contact matrix using CaTCH (36) with the reciprocal insulation (RI) parameter set to 0.80. A contact matrix was extracted from the contact map result using Juicer tools dump command. Both contact map and TADs were loaded into JuiceBox (Desktop v1.11.08) (37) and visualized at 5-kb resolution.

Cloning the Enhancer-Reporter Plasmids.

Two fragments of T. osimensis Enh14 (tosEnh14) were PCR-amplified using tosEnh14_F1 +SpeI and tosEnh14_R1+SmaI as well as tosEnh14_F2+SmaI and tosEnh14_R2+EcoRI as primers and spiny rat gDNA as a template. Primers are shown in SI Appendix, Table S6. Two fragments were digested by restriction enzymes and cloned into the pBluescriptII KS (-) vector. After digestion by SpeI and EcoRI, blunt ends at both termini were obtained using Klenow Fragment (TAKARA BIO, Kusatsu, Japan). The fragment was ligated at the SwaI site of pBSII-Sox9p-LacZ-SW, which contained the mouse Sox9 promoter region (chr11:112,780,803–112,782,582 (GRCm38/mm10), LacZ, and SwaI recognition sequence, in order, in pBluescriptII KS (-).

Microinjection of the Sox9 Enhancer-Reporter Plasmid.

To prepare DNA for zygote injection, a plasmid containing the pBSII-Sox9p-LacZ-SW insert with two tosEnh14 fragments was prepared by HindIII digestion, agarose gel separation, extraction using the QIAquick Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), and ethanol precipitation. Oocytes were obtained from superovulated BDF1 females. Fertilized oocytes were prepared by in vitro fertilization of the oocytes and sperms obtained from male mice of the same genetic background. The purified fragment at 10 ng/µL was microinjected into pronuclei of pronuclear stage oocytes. Injected oocytes were cultured in KSOM. On the next day, they were transferred in oviducts of pseudopregnant ICR females.

X-gal Staining.

Embryonic gonad/mesonephros complexes were collected from pseudopregnant females at 13 d after embryo transfer. Gonad/mesonephros complexes were fixed with 1% (w/v) paraformaldehyde/20% glutaraldehyde and stained with X-gal following a standard protocol. For genotyping, genomic DNA was extracted from the yolk sac membrane of the embryo. Genotyping was performed by PCR amplification of the transgene using LacZ-3′F and pBlue-R primers together with control-F and control-R primers, located on Sox5, as a control (SI Appendix, Table S6).

Plasmids and Construction of Single-GuideRNA (sgRNA) Vectors.

As a donor for homologous recombination, a plasmid (donor plasmid) containing a 5′-flanking region of mouse Enh14 (mEnh14), tandemly repeated tosEnh14, and the 3′-flanking region of mEnh14 was constructed. A 695-bp fragment of the 5′-flanking region of mEnh14 with NotI and SpeI restriction sites and a 714-bp fragment of the 3′-flanking region of mEnh14 with EcoRI and SalI restriction sites were amplified using mouse gDNA as a template with the primer pairs Mose_upF+NotI/Mouse_upR+SpeI and Mouse_downF +EcoRI/Mouse_downR+SalI, respectively. Two fragments of tosEnh14 with SpeI and SmaI and with SmaI and EcoRI were amplified with Amami spiny rat gDNA as a template using primer pairs tosEnh14_F1+SpeI/tosEnh14_R1+SmaI and tosEnh14_F2+SmaI/tosEnh14_R2+EcoRI, respectively. Primers are shown in SI Appendix, Table S6. Four fragments were digested by restriction endonucleases and ligated into the pBluescriptII KS (-) vector (SI Appendix, Fig. S3).

gRNA was designed using CRISPRdirect (38) (http://crispr.dbcls.jp). Recognition sequences of the sgRNAs were as follows: Enh14C gRNA: 5′-CATTGCTAGAATGGTAAGATGGG-3′; Enh14T gRNA: 5′-GTCAGTCCTTGAGCCGAGACAGG-3′ PAM sequences are underlined.

RNA Synthesis by In Vitro Transcription Reaction.

sgRNA were synthesized by in vitro transcription using the CUGA7 gRNA Synthesis Kit (Nippon Genetech Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) according to the instruction manual. Primers were Enh14C gRNA1temp and Enh14T gRNA1temp for the generation of Enh14C gRNA and Enh14T gRNA, respectively.

Microinjection.

Fertilized oocytes were collected as described above. In half of the oocytes, a mixture of 250 µg/µL Enh14C gRNA, 250 µg/µL Enh14T gRNA, 10 µg/µL donor plasmid, and Cas9 protein (Nippon Genetech Co. Ltd.) was microinjected in the pronucleus and cytoplasm of fertilized oocytes. The remaining oocytes were cultured without microinjection overnight; on the next day, the same mixture was injected in the nucleus and cytoplasm of one blastomere of the 2-cell-stage embryo. Microinjected embryos were transferred in oviducts of pseudopregnant ICR females.

Genotyping and Mating.

Genomic DNA was extracted from the tail or fingertips of newborn pups. The primer sequences and location are shown in SI Appendix, Table S6 and Fig. S3. PCR amplification was performed using KAPA Taq (NIPPON Genetics, Tokyo, Japan) and Ex Taq (TAKARA BIO). The PCR products were subjected to direct sequencing. Chromosomal sex was determined by PCR genotyping for Uba1 on the X chromosome and Uba1y on the Y chromosomes (39).

Six F0 individuals were obtained. The F1 generation was produced by mating F0 individuals with wild-type C57BL/6. Mutants were maintained by mating with wild-type C57BL/6. To generate homozygous mutants, heterozygous mutants of the same generation were crossed.

Analysis of Genome-Editing Mice.

We observed the anatomical differences of gonads of adult genome-editing mouse by hematoxylin and eosin staining. The expression of SOX9 and FOXL2 in embryonic gonads of genome-editing mice was examined by immunofluorescence staining and real-time PCR. Detailed methods of these experiments are described in SI Appendix, Supplementary text.

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to A. Tokuhisa, R. Kudo, Y. Nakamura, and M. Okano for supporting this study. We thank NODAI Genome Research Center, Tokyo University of Agriculture, Tokyo, Japan for supporting genome sequencing. This work was funded by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number 16H06279 (PAGS), 26113701, 19H03267, and 22H02667.

Author contributions

S.T., T.I., and A.K. designed research; M.T., Y.O., S.T., A.T., T.K., S.M., and A.K. performed research; T.J. contributed new reagents; R.K., M.O., Y.M., K.M., T.I., and A.K. analyzed data; and S.T., R.K., M.O., T.I., and A.K. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

The raw Illumina sequence reads for the whole genome and Hi-C data have been deposited in the DDBJ Sequence Read Archive (DRR066821–DRR066828 and DRR378863). The assembled genomes are available in DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under accession number BPMZ01000000. Phased genome sequences of the Sox9 upstream region are available under accession numbers, LC641707 (allele 1: duplicated), LC641708 (allele 2: nonduplicated), and LC641709 (BAC 199P19).

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Koopman P., et al. , Male development of chromosomally female mice transgenic for Sry. Nature 351, 117–121 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Honda T., Suzuki H., Itoh M., An usual sex chro mosome constitution found in the Amami spinous country-rat, Tokudaia osimensis osimensis. Jpn. J. Genet. 52, 247–249 (1977). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sutou S., Mitsui Y., Tsuchiya K., Sex determination without the Y chromosome in two Japanese rodents Tokudaia osimensis osimensis and Tokudaia osimensis spp. Mamm. Genome 12, 17–21 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Just W., et al. , Absence of Sry in species of the vole Ellobius. Nat. Genet. 11, 117–118 (1995). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fredga K., Lyapunova E. A., Fertile males with two X chromosomes in Ellobius tancrei (Rodentia, Mammalia). Hereditas 115, 86–97 (1991). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murata C., et al. , Multiple copies of SRY on the large Y chromosome of the Okinawa spiny rat, Tokudaia muenninki. Chromosome Res. 18, 623–634 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kimura R., Murata C., Kuroki Y., Kuroiwa A., Mutations in the testis-specific enhancer of SOX9 in the SRY independent sex-determining mechanism in the genus Tokudaia. PLoS One 9, e108779 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otake T., Kuroiwa A., Molecular mechanism of male differentiation is conserved in the SRY-absent mammal, Tokudaia osimensis. Sci. Rep. 6, 32874 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobayashi T., et al. , Exceptional minute sex-specific region in the X0 mammal, Ryukyu spiny rat. Chromosome Res. 15, 175–187 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobayashi T., et al. , Centromere repositioning in the X chromosome of XO/XO mammals, Ryukyu spiny rat. Chromosome Res. 16, 587–593 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamada F., et al. , Rediscovery after thirty years since the last capture of the critically endangered Okinawa spiny rat Tokudaia muenninki in the northern part of Okinawa Island. Mammal Study 35, 243–255 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vidal V. P., Chaboissier M. C., de Rooij D. G., Schedl A., Sox9 induces testis development in XX transgenic mice. Nat. Genet. 28, 216–217 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jo A., et al. , The versatile functions of Sox9 in development, stem cells, and human diseases. Genes Dis. 1, 149–161 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Symon A., Harley V., SOX9: A genomic view of tissue specific expression and action. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 87, 18–22 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim G.-J., et al. , Copy number variation of two separate regulatory regions upstream of SOX9 causes isolated 46, XY or 46, XX disorder of sex development. J. Med. Genet. 52, 240–247 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Croft B., et al. , Human sex reversal is caused by duplication or deletion of core enhancers upstream of SOX9. Nat. Commun. 9, 5319 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyon C., et al. , Refining the regulatory region upstream of SOX9 associated with 46, XX testicular disorders of Sex Development (DSD). Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 167A, 1851–1858 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sekido R., Lovell-Badge R., Sex determination involves synergistic action of SRY and SF1 on a specific Sox9 enhancer. Nature 453, 930–934 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uhlenhaut N. H., et al. , Somatic sex reprogramming of adult ovaries to testes by FOXL2 ablation. Cell 139, 1130–1142 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gonen N., et al. , Normal levels of Sox9 expression in the developing mouse testis depend on the TES/TESCO enhancer, but this does not act alone. PLoS Genet. 13, e1006520 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonen N., et al. , Sex reversal following deletion of a single distal enhancer of Sox9. Science 360, 1469–1473 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ogawa Y., et al. , Mapping of a responsible region for sex reversal upstream of Sox9 by production of mice with serial deletion in a genomic locus. Sci. Rep. 8, 17514 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Franke M., et al. , Formation of new chromatin domains determines pathogenicity of genome duplications. Nature 538, 265–269 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Despang A., et al. , Functional dissection of the Sox9-Kcnj2 locus identifies nonessential and instructive roles of TAD architecture. Nat. genet. 51, 1263–1271 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ridnik M., Schoenfelder S., Gonen N., Cis-regulatory control of mammalian sex determination. Sex Dev. 15, 317–334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takehana Y., et al. , Co-option of Sox3 as the male-determining factor on the Y chromosome in the fish Oryzias dancena. Nat. Commun. 5, 4157 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kuroiwa A., et al. , The process of a Y-loss event in an XO/XO mammal, the Ryukyu spiny rat. Chromosoma 119, 519–526 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arakawa Y., et al. , X-chromosomal localization of mammalian Y-linked genes in two XO species of the Ryukyu spiny rat. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 99, 303–309 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yamauchi Y., Riel J. M. Z., Stoytcheva Z., Ward M. A., Two Y genes can replace the entire Y chromosome for assisted reproduction in the mouse. Science 343, 69–72 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Honda A., et al. , Flexible adaptation of male germ cells from female iPSCs of endangered Tokudaia osimensis. Sci. Adv. 3, e1602179 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Washio K., Mizushima S., Jogahara T., Kuroiwa A., Regulation of the Sox3 Gene in an X0/X0 Mammal without Sry, the Amami spiny rat, Tokudaia osimensis. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 159, 143–150 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Durand N. C., et al. , Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Syst. 3, 95–98 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li H., Durbin R., Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25, 1754–1760 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rao S. S., et al. , A 3D map of the human genome at kilobase resolution reveals principles of chromatin looping. Cell 159, 1665–1680 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knight P. A., Ruiz D., A fast algorithm for matrix balancing. IMAJNA 33, 1029–1047 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhan Y., et al. , Reciprocal insulation analysis of Hi-C data shows that TADs represent a functionally but not structurally privileged scale in the hierarchical folding of chromosomes. Genome Res. 27, 479–490 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Durand N. C., et al. , Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell Syst. 3, 99–101 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naito Y., Hino K., Bono H., Ui-Tei K., CRISPRdirect: Software for designing CRISPR/Cas guide RNA with reduced off-target sites. Bioinformatics 31, 1120–1123 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chuma S., Nakatsuji N., Autonomous transition into meiosis of mouse fetal germ cells in vitro and its inhibition by gp130-mediated signaling. Dev. Biol. 229, 468–479 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

The raw Illumina sequence reads for the whole genome and Hi-C data have been deposited in the DDBJ Sequence Read Archive (DRR066821–DRR066828 and DRR378863). The assembled genomes are available in DDBJ/ENA/GenBank under accession number BPMZ01000000. Phased genome sequences of the Sox9 upstream region are available under accession numbers, LC641707 (allele 1: duplicated), LC641708 (allele 2: nonduplicated), and LC641709 (BAC 199P19).