Standard-of-care therapies for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (NDMM) include proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulatory drugs, chemotherapy, dexamethasone, or prednisone in various combination regimens.1 Addition of an anti-CD38 monoclonal antibody to standard regimens in the first-line setting can result in deep and sustained responses.1,2 Prognosis for patients with MM may depend on disease-related characteristics such as overall tumor burden and biology, as well as patient-related factors including older age, functional status, extent of renal impairment, and other potential comorbidities. Although recent therapeutic advances contributed to improve clinical outcomes in NDMM, patients not eligible for autologous stem cell transplantation still have limited survival, as they often receive less intensive therapy owing to their advanced age and/or the presence of comorbidities.1–3

Bortezomib-cyclophosphamide-dexamethasone (VCd) is an effective and generally tolerable 3-drug regimen used in NDMM, including treatment of both transplant-eligible and transplant-ineligible patients.4–6 Furthermore, VCd was previously considered a standard-of-care treatment for NDMM patients in the 2017 European Society for Medical Oncology (ESMO) clinical practice guidelines.6

The monoclonal antibody isatuximab (Isa) targets a specific epitope of CD38 and kills MM cells through multiple mechanisms of action; it is approved in various countries in combination with pomalidomide-dexamethasone and with carfilzomib-dexamethasone for patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma.7,8

To improve on outcomes with a widely used regimen and evaluate a novel anti-CD38 antibody quadruplet regimen, this multicenter Phase 1b study (NCT02513186) assessed safety and preliminary efficacy of Isa in combination with VCd for the treatment of transplant-ineligible NDMM patients.

Dose escalation of Isa in combination with fixed dosing of VCd followed a standard 3 + 3 design. Isa 10 mg/kg was chosen as the starting dose as it is the dose level (DL) below the recommended dose (20 mg/kg), based on prior monotherapy studies.9,10 Patients were then enrolled in an expansion cohort, to further evaluate the Isa–VCd combination at the selected Isa DL. Primary objectives were to determine the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) and recommended dose of Isa in combination with VCd, based on the dose-limiting toxicity (DLT) observed, and evaluate preliminary efficacy (overall response rate [ORR], complete response [CR] rate), according to the International Myeloma Working Group response criteria. Further details on study design, secondary objectives, patient inclusion/exclusion criteria, assessments, and statistical analyses are provided in Suppl. Information.

For the induction phase (12 cycles), patients received Isa-VCd with Isa (10 mg/kg or 20 mg/kg in dose escalation; 10 mg/kg in the expansion cohort) administered IV once weekly (QW) in cycle 1 (6-week cycle) then once every 2 weeks (Q2W) in cycles 2–12 (4-week cycles) (Suppl. Figure S1). In the maintenance phase, patients continued treatment with Isa at its initial assigned dose and dexamethasone 20 mg (or equivalent), both administered once every 28 days until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity, or patient/investigator decision to discontinue.

Seventeen transplant-ineligible NDMM patients were enrolled in the study: 13 at Isa DL 10 mg/kg and 4 at Isa DL 20 mg/kg. In dose escalation, 4 patients each received Isa 10 mg/kg or Isa 20 mg/kg plus VCd. With no DLTs reported at either DL, the MTD was not reached. As frequency and severity of the adverse events (AEs) did not appear to be dose-dependent and was not different between DLs, the recommended dose of Isa 10 mg/kg was chosen based on PK/PD modeling and simulations made for the TCD11863 (NCT01749969) Phase 1b study11 and selected for further Isa combination studies administered weekly for 4 weeks followed by every 2 weeks. Nine additional patients were then treated at the selected Isa 10 mg/kg DL plus VCd, in the dose-expansion part of the study, which was ongoing at the cutoff date (April 19, 2021; median duration of exposure 4.5 [0.02–5.33] years).

At study entry, median age of all patients (N = 17) was 71 (68–80) years, with 4 (23.5%) patients aged ≥75 years (Table 1). Twelve (70.6%) patients had ISS stage II–III and 11 (64.7%) patients had bone lesions. Five (29.4%) patients had an estimated glomerular filtration rate between 30 and <60 mL/min/1.73 m2. Eight (47.1%) patients were still on treatment at database extraction (June 8, 2021), while 9 had discontinued due to disease progression (29.4%), AE (17.6%), and withdrawal for transplant (5.9%). The median duration of exposure to the Isa-VCd regimen was 53.82 (0.23–64.01) months. Addition of Isa to VCd did not affect exposure to the combination as the median relative dose intensities were 95.5% (60.5–120%) for Isa, 95.0% (85.1–176.1%) for bortezomib, 94.5% (84.3–151.5%) for cyclophosphamide, and 96.1% (58.7–155.6%) for dexamethasone (Suppl. Table S1).

Table 1.

Patient Demographic and Baseline Characteristics

| Isa-VCd (N = 17)a |

|

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Median (range), y | 71.0 (68–80) |

| Age group, n (%) | |

| <65 y | 0 |

| 65–74 y | 13 (76.5) |

| ≥75 y | 4 (23.5) |

| Male, n (%) | 9 (52.9) |

| ECOG PS, n (%) | |

| 0 | 9 (52.9) |

| 1 | 6 (35.3) |

| 2 | 2 (11.8) |

| ISS at initial diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Stage I | 5 (29.4) |

| Stage II | 6 (35.3) |

| Stage III | 6 (35.3) |

| Patients with high-risk cytogenetics, n (%)b,c | 1 (5.9)d |

| Patients 1q21+, n (%)e | 1 (5.9) |

| Median bone marrow plasma cells, % (range) | 30.0 (10.0–85.0) |

| Bone marrow plasma cells (%), by category | |

| 5–<20 | 4 (23.5) |

| 20–<50 | 10 (58.8) |

| ≥50 | 3 (17.6) |

| Plasmacytoma, n (%) | 1 (5.9) |

| Bone lesions, n (%) | 11 (64.7) |

| Creatinine clearance, n (%) | |

| GFR ≥90 mL/min/1.73 m2 (normal) | 2 (11.8) |

| 60 ≤ GFR <90 mL/min/1.73 m2 (mild) | 10 (58.8) |

| 30 ≤ GFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (moderate) | 5 (29.4) |

| 15 ≤ GFR <30 mL/min/1.73 m2 (severe) | 0 |

| GFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2 (end-stage renal disease) | 0 |

aIsa 10 mg/kg-VCd, n = 13; Isa 20 mg/kg-VCd, n = 4.

bMolecular subtypes were determined by cytogenetic analysis with both local and central fluorescence in situ hybridization assessments.

cTwo patients were not evaluable for 17p deletion or t(4;14) translocation.

dt(4;14).

eSix patients were not evaluable for 1q21+ status.

C = cyclophosphamide; d = dexamethasone; ECOG PS = Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status; GFR = glomerular filtration rate; Isa = isatuximab; ISS = International Staging System; V = bortezomib.

Among the patients enrolled at the Isa-10 mg/kg DL (n = 13) and 20 mg/kg DL (n = 4), 3 patients at each DL in dose escalation were evaluable for DLTs. No DLTs were observed. Any-causality grade ≥3 treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) were reported in 14 (82.4%) patients (N = 17) (Table 2) and study drug-related grade ≥3 TEAEs in 8 (47.1%). Any-causality serious TEAEs occurred in 9 (52.9%) patients, with grade ≥3 events in 8 of 9 patients. They consisted of pneumonia (n = 4, 26.7%), appendicitis, back pain, bronchospasm, gastroenteritis, septic shock, sudden death, and mesenteric vein thrombosis (preferred terms, n = 1, 5.9% each). Three (17.6%) patients died during the on-treatment period: 2 due to AEs (pneumonia/10 mg/kg DL, sudden death/20 mg/kg DL), and 1 due to disease progression (10 mg/kg DL).

Table 2.

Summary of TEAEs (Safety Population)

| n (%) | Isa-VCd (N = 17)a |

|---|---|

| Any TEAE | 17 (100) |

| Grade ≥3 TEAEs | 14 (82.4) |

| Drug-related TEAEs | 16 (94.1) |

| Drug-related TEAEs grade ≥3 | 8 (47.1) |

| Treatment-emergent SAEs | 9 (52.9) |

| Drug-related treatment-emergent SAEs | 4 (23.5) |

| TEAEs leading to deathb | 3 (17.6) |

| TEAEs leading to definitive study treatment discontinuationc | 3 (17.6) |

| TEAEs leading to premature study drug discontinuation | 1 (5.9) |

| Bortezomib | 0 |

| Cyclophosphamide | 0 |

| Dexamethasone | 1 (5.9) |

| Any DLT | 0 |

| Any AESI | 9 (52.9) |

| Any AESI grade ≥3 | 1 (5.9) |

| Any IR | 9 (52.9) |

| Any IR grade ≥3 | 1 (5.9) |

aIsa 10 mg/kg-VCd, n = 13; Isa 20 mg/kg-VCd, n = 4.

bPneumonia, sudden death.

cWhen Isa treatment was permanently discontinued, study treatment was terminated. TEAEs included grade 3 bronchospasm at day 1/cycle 1 in the context of a grade 3 IR, pneumonia, and sudden death.

AESI = adverse event of special interest; C = cyclophosphamide; d = dexamethasone; DLT = dose-limiting toxicity; IR = infusion reaction; Isa = isatuximab; SAE = serious AE; TEAE = treatment- emergent AE; V = bortezomib.

Per protocol, if Isa was discontinued, the patient could not continue with the backbone therapy and discontinued study treatment. TEAEs led to permanent study treatment discontinuation in 3 (17.6%) patients (grade 3 bronchospasm in the context of grade 3 infusion reaction [IR] and grade 3 pneumonia [10 mg/kg DL], sudden death [20 mg/kg DL]). No patient had TEAEs leading to premature discontinuation of bortezomib or cyclophosphamide; 1 (5.9%) patient prematurely discontinued dexamethasone due to a TEAE (grade 2 amnesia).

The most common TEAEs, listed in Suppl. Table S2, were mostly grade 1–2 (back pain, 58.8%; diarrhea, 52.9%; IR, 52.9%). Non-hematologic grade ≥3 AEs reported in >1 patient were grade 3 hypertension in 3 (17.6%) patients and pneumonia in 4 (26.7%) patients. Overall, respiratory infections occurred as TEAEs in 13 (76.5%) patients, which were grade ≥3 in 4 (23.5%) patients (Suppl. Table S3). Any-grade IRs were observed in 9 (52.9%) patients, with a grade ≥3 event in 1 (5.9%, 10 mg/kg DL) patient. IRs generally occurred as a single episode at first infusion (Suppl. Table S4). In the Isa 10 mg/kg-VCd group, median duration of first Isa infusion was 2.83 (0.9–6.0) hours and 2.76 (1.0–5.0) hours for subsequent Isa infusions. Seven (41.2%) patients had grade 1–2 peripheral sensory neuropathy, leading to bortezomib dose reduction and dose delay/dose reduction in 1 (5.9%) patient each. Of note, no grade 3–4 peripheral neuropathy was observed and no patient discontinued study treatment due to peripheral neuropathy. This may be partially explained by the early switch to weekly bortezomib.

On-treatment, grade 3–4 hematologic laboratory abnormalities (n = 16) included grade 3 anemia in 2 (12.5%) patients (no grade 4), grade 3–4 neutropenia in 3 (18.8%), and grade 4 thrombocytopenia in 1 (6.3%) patient (no grade 3) (Suppl. Table S5). No neutropenic infections or febrile neutropenia were observed.

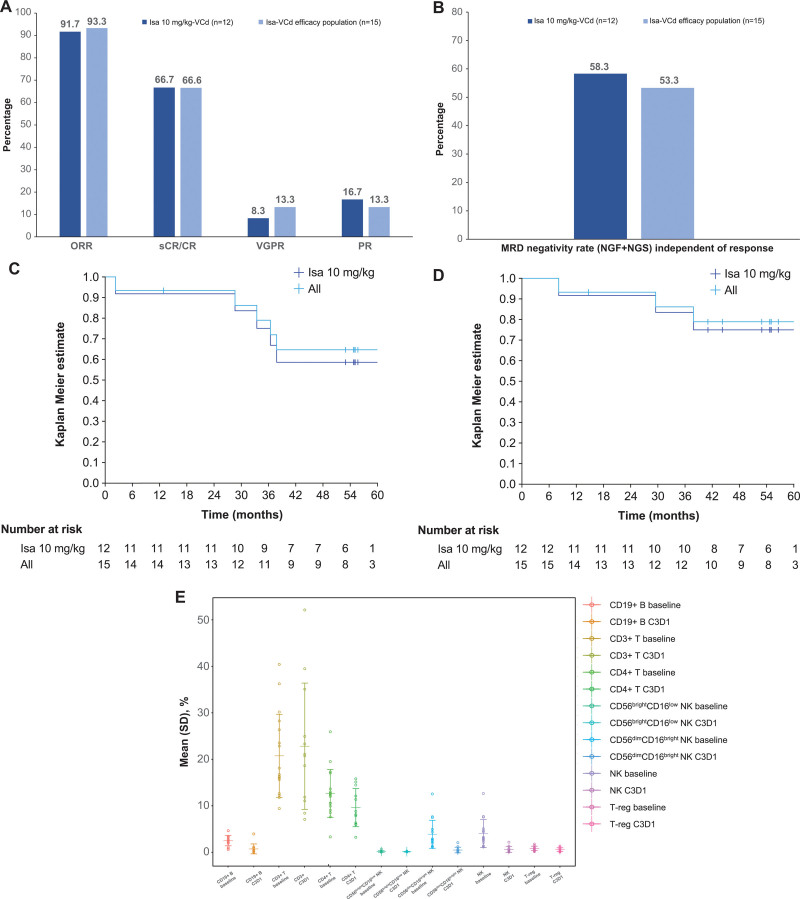

The ORR was 91.7% in evaluable patients treated with Isa 10 mg/kg-VCd (n = 12) and 93.3% in the overall efficacy population (n = 15), which also included 3 patients treated with Isa 20 mg/kg-VCd (Figure 1A). Ten (66.6%) patients achieved a stringent CR (sCR)/CR (8 [53.3%] a sCR, 2 [13.3%] a CR), 2 (13.3%) a VGPR, 2 (13.3%) a PR, and 1 (6.7%) patient had stable disease. CR/sCR rates may be underestimated due to potential Isa interference with M-protein assessment, as an assay to remove such an interference was not available at the time of these response evaluations.

Figure 1.

Best overall response (A), PFS (B), OS (C), MRD (D), and blood cell immunophenotyping results at baseline and day 1/cycle 3 (predose) (E). (A–D) Patients included in efficacy population (n = 15): Isa 10 mg/kg-VCd, n = 12; Isa 20 mg/kg-VCd, n = 3. All = all patients in the efficacy population. MRD was evaluated in patients with ≥VGPR by NGF and NGS methods at 10−5 and MRD negativity rate determined by combining both methods in the case of at least 1 method yielding negative results and the other method showing no positive result at the same time. (E) Patients included in baseline population: Isa 10 mg/kg–VCd, n = 13; Isa 20 mg/kg–VCd, n = 4 and in on-treatment population: Isa 10 mg/kg-VCd, n = 10; Isa 20 mg/kg-VCd, n = 2. Results expressed as percentage of leukocytes. C = cyclophosphamide; C3D1 = cycle 3 day 1; CR = complete response; d = dexamethasone; Isa = isatuximab; MRD = minimal residual disease; NGF = next-generation flow; NGS = next-generation sequencing; NK = natural killer; ORR = overall response rate; OS = overall survival; PFS = progression-free survival; PR = partial response; sCR = stringent CR; SD = standard deviation; T-reg = regulatory T cell; V = bortezomib; VGPR = very good partial response.

Median time to first response was 1.45 months. The patients with t(4;14) translocation, 1q21+ status or soft tissue plasmacytoma (n = 1 each) achieved a sCR. Among the 5 patients with renal impairment at baseline, 1 patient reached a sCR, 1 a CR, and 1 had stable disease (2 patients were not evaluable for efficacy). Complete renal response was observed in 2 of the 3 evaluable patients with renal impairment. At an overall median follow-up of 54.8 (4.3–63.3) months, responses were durable with an overall median duration of 52.2 (11.3–61.8) months, which was similar in the Isa 10 mg/kg-VCd (52.8 months) and Isa 20 mg/kg-VCd (49.8 months) groups.

Analysis of progression-free survival (PFS) showed an estimated median PFS of 63.3 (95% CI, 28.6-not calculable [N.C.]) months in the Isa 10 mg/kg-VCd group and 63.3 (95% CI, 33.5-N.C.) months in the overall efficacy population (Figure 1B, Suppl. Table S6). The probabilities of PFS at 60 months were 58% (95% CI, 27%-80%) and 65% (95% CI, 35%-84%), respectively. Median overall survival (OS) was not reached in either the Isa 10 mg/kg-VCd group or the overall efficacy population; the probabilities of OS at 60 months were 75% (95% CI, 41%-91%) and 79% (95% CI, 48%-93%), respectively (Figure 1C, Suppl. Table S6).

Twelve (80%) patients reached ≥VGPR as best response. Minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity (evaluated by combining next-generation flow and next-generation sequencing assessments, sensitivity 10−5) was achieved by 7 (58.3%) patients in the Isa 10 mg/kg-VCd group and 8 (53.3%) in the overall efficacy population (7 patients with sCR/CR, 1 with VGPR) (Figure 1D). Four patients with MRD-negative status at 10−5 were selected for an exploratory mass-spectrometry (MS) analysis of M-protein levels. Three of these MRD-negative (at 10−5) patients had detectable levels of M-protein by MS, including 1 patient with detectable serum M-protein levels and MRD-negative status at 10−6, indicating the high sensitivity of this method for residual M-protein beyond MRD negativity (Suppl. Table S7). Low levels of M-protein were detectable by MS up to 23 months after determination of MRD negativity (10−5), in progression-free patients.

Pharmacokinetic parameters for Isa following single- and multiple-dose administration are listed in Suppl. Tables S8, S9. Exposure of Isa, administered at 10 and 20 mg/kg QW/Q2W with VCd, appeared comparable to those estimated when Isa was administered alone.10

A descriptive, immunophenotyping analysis of the distribution of blood immune cell subpopulations, pre-dose (day 1/cycle 3) compared to baseline in treated, evaluable patients (n = 12), showed a slight increase in mean CD3+ T cell levels from 20.75% to 22.82%, a decrease in mean levels of CD4+ T cells (from 12.67% to 9.60%), total natural killer (NK) cells (from 4.04% to 0.60%) including CD56bright CD16low NK cells (from 0.17% to 0.12%), and T-regulatory cells (from 0.83% to 0.56%), as well as a more pronounced decrease in CD19+ B cells (from 2.52% to 0.72%) and CD56dim CD16bright NK cells (from 3.87% to 0.48%) (Figure 1E). These results suggest that Isa-VCd may be associated with T-cell–mediated immune activity and a reduction in T-cell immunosuppressive mechanisms in myeloma patients.

In conclusion, this was the first trial evaluating the safety and preliminary efficacy of adding Isa to a 3-drug regimen such as VCd for the treatment of transplant-ineligible NDMM patients. Isa-VCd has demonstrated promising clinical activity in this patient population, with a safety profile consistent with that of each individual drug and no new safety signals, suggesting that the combination of Isa with VCd is feasible. Although the small sample size represents a limitation of this study, our results compared well with triplet or quadruplet regimens including an anti-CD38 antibody, already approved in similar populations of NDMM patients (for further discussion see Suppl. Information).12,13

These findings support further studies of Isa in quadruplet combination treatments for NDMM patients. Isa-VCd is being evaluated in phase 2 studies, as induction therapy for transplant-eligible NDMM patients and NDMM patients with renal impairment (NCT04240054, NCT04786028). Although Isa in combination with VCd has shown substantial antimyeloma activity in this study, treatment strategies are evolving and the new 2021 EHA-ESMO guidelines do not recommend VCd as a standard-of-care.14 Thus, Isa-VCd is currently not being further evaluated in a randomized phase 3 trial versus VCd, which would not be considered an appropriate comparator arm for a general population of NDMM patients. Instead, other ongoing investigations are evaluating Isa in quadruplet combination with VRd. Randomized phase 3 studies of Isa-VRd are in progress in the front-line treatment of transplant-eligible (GMMG-HD7, NCT03617731)15 and transplant-ineligible NDMM patients (IMROZ, NCT03319667).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the participating patients and their caregivers, the study centers, and the investigators for their contributions to the study. Medical writing support was provided by S. Mariani, MD, PhD, of Elevate Medical Affairs, contracted by Sanofi for publication support services.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

EMO, JS-M, NLR, YD, SM, and M-VM designed the study, analyzed the data, wrote/critically revised the manuscript, and approved final version. SB, JM-L, SO, PR-O, and SD analyzed the data, critically revised the manuscript, and approved final version.

DISCLOSURES

EMO received honoraria from Amgen, BMS/Celgene, GSK, Janssen, Oncopeptides, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Takeda; disclosed participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for AbbVie, Amgen, BMS/Celgene, GSK, Janssen, Karyopharm, Menarini, Oncopeptides, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Takeda; received travel and accommodation support from BMS/Celgene, GSK, Janssen, and Sanofi. SB received honoraria from Amgen, BMS/Celgene, and Janssen; consulting fees from BMS/Celgene, Janssen, and Takeda; disclosed participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for Amgen, Celgene, GSK, Janssen, Karyopharm, and Sanofi. JM-L received honoraria and consulting fees from BMS/Celgene, Incyte, Janssen, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi; travel and accommodation support from BMS, Janssen, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi. JS-M received honoraria and consulting fees from Amgen, BMS/Celgene, GSK, Janssen, Karyopharma, Sanofi, and Takeda. SO received honoraria from Amgen, BMS/Celgene, Janssen, Sanofi, and Takeda. PR-O received consulting fees from BMS/Celgene, GSK, and Pfizer; honoraria from Amgen, BMS, GSK, Janssen, Regeneron, Sanofi, and Takeda; disclosed participation on a data safety monitoring board or advisory board for AbbVie, BMS, GSK, Janssen, Kite Pharma, Oncopeptides, Pfizer, Sanofi, and Takeda. NLR is employed by Altran, contracted by Sanofi. YD, SD, and SM are employed by Sanofi and may hold stock/options in the company. M-VM is on the Editorial Board of HemaSphere.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This study was funded by Sanofi.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Trial registration: ClinicalTrials.gov, NCT02513186.

Data sharing statement: Qualified researchers may request access to patient level data and related study documents including the clinical study report, study protocol with any amendments, blank case report form, statistical analysis plan, and dataset specifications. Patient level data will be anonymized and study documents will be redacted to protect the privacy of our trial participants. Further details on Sanofi’s data sharing criteria, eligible studies, and process for requesting access can be found at https://www.vivli.org/.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mateos MV, San Miguel JF. Management of multiple myeloma in the newly diagnosed patient. Hematology Am Soc Hematol Educ Program. 2017;2017:498–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bonello F, Grasso M, D’Agostino M, et al. The role of monoclonal antibodies in the first-line treatment of transplant-ineligible patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2020;14:20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bringhen S, Mateos MV, Zweegman S, et al. Age and organ damage correlate with poor survival in myeloma patients: meta-analysis of 1435 individual patient data from 4 randomized trials. Haematologica. 2013;98:980–987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jimenez-Zepeda VH, Duggan P, Neri P, et al. Bortezomib-containing regimens (BCR) for the treatment of non-transplant eligible multiple myeloma. Ann Hematol. 2017;96:431–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mai EK, Bertsch U, Dürig J, et al. Phase III trial of bortezomib, cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone (VCD) versus bortezomib, doxorubicin and dexamethasone (PAd) in newly diagnosed myeloma. Leukemia. 2015;29:1721–1729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moreau P, San Miguel J, Sonneveld P, et al. Multiple myeloma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(suppl 4):iv52–iv61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Leleu X, Martin T, Weisel K, et al. Anti-CD38 antibody therapy for patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma: differential mechanisms of action and recent clinical trial outcomes. Ann Hematol. 2022;101:2123–2137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarclisa. Prescribing information. Sanofi. 2022. Available at: https://products.sanofi.us/Sarclisa/sarclisa.pdf. Accessed November 8, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mikhael J, Richter J, Vij R, et al. A dose-finding Phase 2 study of single agent isatuximab (anti-CD38 mAb) in relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Leukemia. 2020;34:3298–3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martin T, Strickland S, Glenn M, et al. Phase I trial of isatuximab monotherapy in the treatment of refractory multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J. 2019;9:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin T, Baz R, Benson DM, et al. A phase 1b study of isatuximab plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone for relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma. Blood. 2017;129:3294–3303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moreau P, Facon T, Usmani S, et al. Conference Abstract: Abstract OAB-039. Paper presented at: 19th International Myeloma Society Annual Meeting; August 25–August 27, 2022; Los Angeles CA, US. Available at: https://clin.larvol.com/abstract-detail/IMW%202022/58671731. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mateos MV, Cavo M, Blade J, et al. Overall survival with daratumumab, bortezomib, melphalan, and prednisone in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (ALCYONE): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;395:132–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dimopoulos MA, Moreau P, Terpos E, et al. Multiple myeloma: EHA-ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:309–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldschmidt H, Mai EK, Nievergall E, et al. Addition of isatuximab to lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone as induction therapy for newly diagnosed, transplantation-eligible patients with multiple myeloma (GMMG-HD7): part 1 of an open-label, multicentre, randomised, active-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Haematol. 2022;9:e810–e821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.