ABSTRACT

Background

Violence against women and girls (VAWG) is a major problem in Tajikistan, driven by conservative gender norms, the culturally ascribed position of young women, and poverty.

Objective

We evaluated Zindagii Shoista (Living with Dignity), an intervention developed with the aim of reducing VAWG through a combination of gender norm change, communication skills, and income-generating activities (IGA) over a period of 30 months.

Methods

The evaluation used a mixed-methods approach, combining quantitative and qualitative data collection. Eighty families from four villages were enrolled in the intervention and surveyed at baseline and on three subsequent occasions. From these families, 134 women and 102 men were interviewed at baseline, 153 women and 89 men 8 months later, 153 women and 93 men 15 months later, and 143 women and 82 men, 30 months after the baseline. Generalised random effects regression models were used to assess the trend in proportions or mean score over time.

Results

Over the 30 months, the proportion of women and men earning in the past month rose from 17.9% to 56.6% and 44.1% to 72%, respectively. Women and men’s gender attitudes became significantly less patriarchal, and they reported less harmful gender norms in the community. Women and men reported less male controlling behaviour and greater woman involvement in decision-making. Women’s reports of experience of emotional, physical, and sexual IPV significantly reduced. Depressive symptoms and suicidal thoughts reduced significantly for men and women, and self-rated health improved.

Conclusions

The quantitative findings are confirmed by the findings of the qualitative research and monitoring data. They demonstrate that Zindagii Shoista is a very promising intervention for strengthening gender relations, reducing IPV, and improving mental health and socio-economic circumstances for younger married women and their families in Tajikistan.

KEYWORDS: Violence against women and girls, intimate partner violence, domestic violence, women economic empowerment

Background

In Tajikistan, in the heart of Central Asia, violence against women and girls (VAWG) is a substantial problem, affecting at least half of women in their lifetime [1]. Levels of emotional abuse are particularly high, with a household survey in Khatlon Region reporting that it was experienced by 37.3% of women in the previous year, and 40.3% of women had ever experienced marital rape [2]. VAWG is driven by the patriarchal social norms, cultural traditions around co-habitation with the husband’s in-laws on marriage, and the privileging of elders over younger people, as well as severe poverty. Women generally marry young, moving into their husband’s family home, and are vulnerable to violence from their husbands, as well as members of his family [3–8]. Acceptance of violence and controlling behaviour is high and linked to norms, supported by men and women alike, around the importance of protecting family honour and linking this to younger women’s behaviour [3,8]. Tajikistan is a low-income country, with the greatest income generating opportunities for men lying in labour migration to Russia. Usually, when men migrate, their wives are left with their in-laws.

Recognising the nexus of patriarchy and poverty in driving VAWG and constraining women’s power and possibilities, researchers and implementers have sought to combine economic empowerment and gender transformative interventions, with different degrees of success in impacting VAWG [9]. There have been good examples of interventions that have effectively combined a gender transformative elements with microfinance [10], or cash transfers [11], but there has been little research with interventions that establish income-generating projects. Mostly, the economic intervention has targeted women, but a notable exception of Stepping Stones and Creating Futures, used in South Africa, which has had considerable success through also focusing on men [12,13]. Zindagii Shoista (Living with Dignity) was developed to prevent VAWG in Tajikistan, combining an attitudinal and gender norm change component with life skills and income-generating activities, drawing on the experiences of Stepping Stones and Creating Futures [14,15]. To our knowledge, it is the first intervention to be developed in Central Asia that seeks to prevent VAWG through working across two generations within the family and it is the first VAWG prevention intervention developed specifically for the Tajikistan cultural context. In this paper, we present the findings of research conducted with the aim of showing proof of the concept, particularly whether the intervention model combining behavioural change and income-generating activities showed promise in reducing VAWG in the target families and what other short- to medium-term impacts of the intervention might be attributed to the intervention.

Methods

Setting

The Zindagii Shoista intervention was piloted in four villages, two in the northern district of Penjikent and two in the southern district of Jomi, as part of the global DFID-funded ‘What Works to Prevent VAWG?’ programme. The Penjikent villages were in the northern mountainous region of the country with a predominantly Uzbek population, and the Jomi villages were on the southern plains region with a predominantly ethnic Tajik population. The villages had a comparatively low standard of living and limited economic opportunities, with a high level of external migration, high level of withdrawal of girls from school, early marriage, and divorce. The logic for choosing the four villages was to allow for a comparison between two areas with different regional dynamics (northern mountainous region vs. southern plains region) as well as different ethnic compositions (predominantly ethnic Uzbek and Tajik, respectively), and by comparing for proximity to an urban centre.

Participants

We selected 20 families from each village for the pilot and intended to involve two men and two women per family, across two generations. The sample size was based on feasibility. Families were selected based on vulnerability criteria developed jointly by Alert, Cesvi, and local NGO partners and based on the formative research findings. The families were known locally to have difficulties, including younger women experiencing intimate partner violence (IPV) and violence from in-laws.

The Zindagii Shoista intervention

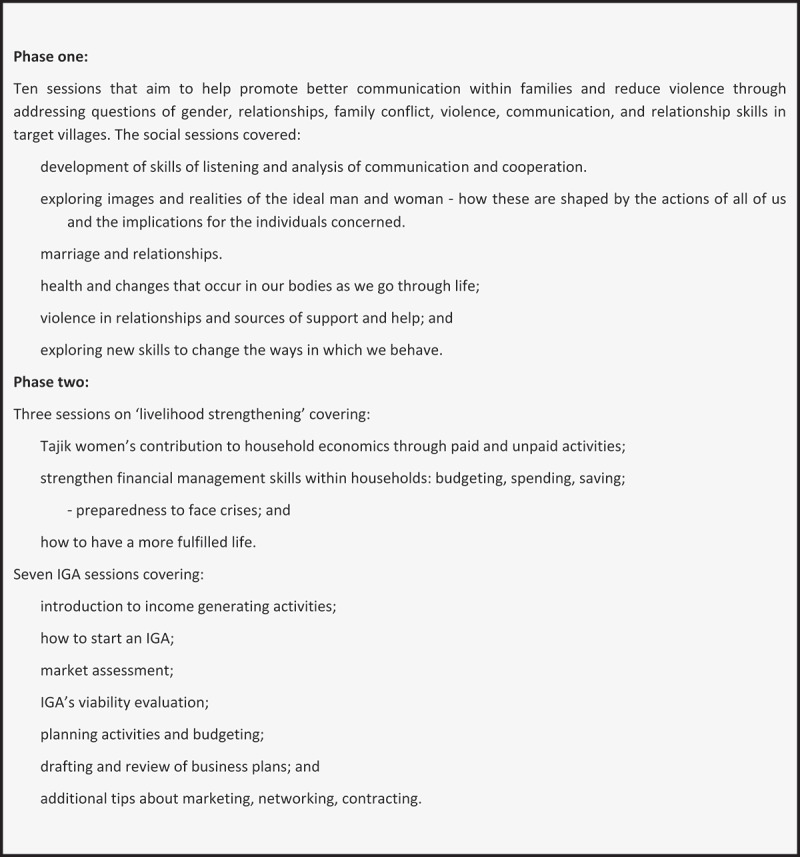

The Zindagii Shoista intervention was developed for use with multi-generational families and combines critical reflection on gender relations, the impact and origins of violence, social value of men and women in the home, and communication skills, and seeks to apply these skills to enhance family relationships (Figure 1). It combines these with a fully supported programme to enable the development of a small-family-led enterprise in which young women have an active role, with business skills, small start-up funds, and technical assistance. It is fully described in two intervention manuals, and its development is presented elsewhere [14–16]. The gender empowerment and communication skills component of 13 sessions was developed from elements of the South African adaptation of Stepping Stones [17] and the livelihood strengthening intervention Creating Futures [18], but the business development component of seven sessions was developed mostly anew, although, based on the business development model of our international non-governmental organisation partner Cesvi [18]. Whilst other gender empowerment and economic interventions to prevent IPV have been evaluated elsewhere when delivered to women and men, the approach chosen for Tajikistan was based on the extended family rather than a husband/wife dyad (cf. Falkingham and Baschieri 2009 [19]) and had not been previously tested [9].

Figure 1.

Outline of Zindagii Shoista.

The programme is based on participatory learning approaches, affirming participants’ knowledge, and enabling them to discuss and decide things for themselves. They were conducted by trained facilitators from the local NGO partners. Facilitators were selected based on their understanding of the local context, language, facilitation skills, and respect within communities locally, enabling them to gain access to families and facilitate discussions on sensitive topics. Business and technical assistants were chosen as individuals with previous experience of establishing IGAs, household money management, and understanding of the business environment. Facilitators for both components were first given a chance to experience the sessions as participants followed by teaching the sessions to their colleagues to build expertise. Additional 2-day gender-sensitisation training was conducted, mainly to build the capacity of male facilitators and business assistants implementing the two components of the project to ensure understanding of the gender-transformative aims of the intervention and how to implement this in a gender-sensitive manner.

The programme was delivered to age- and gender-divided peer groups of 15–20 people in each village: older men, older women, young men, and young women. But all groups came together periodically for joint discussions to share what they have been learning and discussing. The sessions were approximately 3 hours long and were delivered over 20 weeks. The sessions were given once to each group at the beginning of the project. The families afterwards were accompanied by the facilitators and business assistants throughout the project to help with the development and running of IGAs as well as monitoring the changes in power dynamics and relationships in the family. The average attendance rate in both economic and social sessions was approximately 72%. In all, 80 income-generating activities (IGAs) were established by the families and the businesses included baking, tailoring, beekeeping, cattle breeding, renting out plastic tables/kitchen utensils for events, poultry, and greenhouses.

Evaluation design and data collection

The pilot was evaluated using mixed methods, with careful monitoring of the intervention by observing sessions. In this paper, we present the findings of the quantitative component which was a modified interrupted time series with four data points. At baseline, in September 2016, 134 women and 102 men participating in the intervention were interviewed with a standard questionnaire. We repeated interviews 8, 15, and 30 months later, interviewing 153 women and 89 men at 8 months, 156 women and 93 men at 15 months (end point of the intervention), and 143 women and 82 men at 30 months (15 months after the end of the intervention). The number of men interviewed mainly fluctuated due to labour migration, mainly to Russia. The number of women was higher at subsequent interview rounds than baseline due to the latter being coincided during the cotton harvest season of the target districts, in which women are particularly engaged. The fieldwork strategy was adjusted after baseline to improve retention of the sample.

The questionnaire covered the socio-economic situation of respondents, family relations, gender attitudes, experiences of violence, physical and mental health, as well as hopes for the future. Complementary questionnaires were developed for women and men, with the focus of the violence questions on male perpetrated intimate partner violence and violence from the husband’s mother. Details of the items are presented in Table 1. The questionnaires were translated into Tajik and Uzbek languages. The interviews were conducted by male and female interviewers conducting same-sex interviews.

Table 1.

Measures used in the survey instrument[20–28].

| Construct | Measure | Typical items | Origin |

|---|---|---|---|

| Severe food insecurity | Household members experiencing a lack of food in the previous 4 weeks (3 items) | In the past 4 weeks, how often was there no food to eat of any kind in your house because of a lack of money? Severely food insecure was defined as a reply of often to 1 or more of the questions | Coates et al [24] Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) |

| Income-seeking effort scale | Effort trying to get a job or earn money by selling or making things in the last 3 months (7 items) | Typical item: how often have you … Searched newspapers for jobs | Barker G, et al [25]. IMAGES study questionnaire. |

| Stress due to not having work or enough money | 4-item scale with questions about stress related to current work situation | ‘I am frequently stressed or depressed because of’ not having enough work or enough income | Barker G, et al [25]. IMAGES study |

| Unemployment shame | 4-item measure of shame and despondency | Typical item: I sometimes feel ashamed to face my family because I am out of work | Barker G, et al [25]. IMAGES study |

| Depression | CES-D scale (used as a continuous variable) | Typical item: During the past week, I felt I could not cheer myself up even with the help of family and friends Scored high = more depression | Radloff [26] |

| Alcohol | Women: 3 items on husbands’ drinking; Men: 3 items on their drinking | Does he drink? How often? In past 12 m, how often has she seen him drunk? Men asked: Ever drunk? Drunk in past 12 m? How often in past 12 m? | |

| Hope | Scale of 6 items | Typical item: I can think of many ways to get out of a difficult situation | |

| Disability | Disability due to a health problem or injury (6 items) | Typical item: Do you have difficulty walking or climbing steps? | Washington Group Scale |

| Suicidal thoughts | Single item on suicidality in last 4 weeks | In the past four weeks, has the thought of ending your life been in your mind? | |

| Self-rated health | Single item with five response categories | In general, would you describe your overall health as excellent, good, fair, poor or very poor? | |

| Individual gender attitudes | 22 items with Likert responses: strongly agree, agree, disagree, and strongly disagree | Typical item: I think that the daughters-in-law in my family must always obey their mother-in-law | Jewkes et al [29], lightly adapted for the Tajik context after formative research |

| Community gender attitudes (social norms) | 22 items with Likert responses: strongly agree, agree, disagree, and strongly disagree | Typical item: In this community, many people think that if a wife does something wrong, her husband has the right to punish her | Jewkes et al [29], lightly adapted for the Tajik context after formative research |

| Wife’s relationship with her husband | 4 items, statements with Likert responses | Typical item: My husband is a kind person | Based on Jewkes et al [20] adapted for the Tajik context after formative research |

| Man’s relationship with his wife | 5 items, statements with Likert responses | Typical item: My wife does everything she can to support me | |

| Women’s mother-in-law cruelty | 3 items summed: statements with Likert responses | Typical item: My mother-in-law is very strict and controlling | |

| Women’s mother-in-law kind | 3 items summed: statements with Likert responses | Typical item: My mother-in-law is a kind person | |

| Man’s assessment of his mother’s cruelty | 2 items summed: high = more cruel | Typical item: My mother can frighten me | |

| Man’s assessment of his mother’s kindness | 3 items summed: high = more kind | Typical item: My mother does everything she can to support me | |

| Women’s involvement in decision-making | 5 items scored high = more involvement | In the last three months, how often have your views been listened to on problems which your husband or family faces? | |

| Relationship control measure | 8 items, statements with Likert responses | A typical item is he won’t let me spend money on things for myself | Jewkes et al [21], adapted for Tajikistan |

| Frequency of quarrelling | Single item | In your relationship with your husband, how often would you say that you quarrelled? | Based on Jewkes [21] |

| Physical IPV | 5 items (exposure = experience of any act 1 or more times) | Typical item for men: In the past 12 months, how many times have you hit her with a fist or with something else which could hurt her? | Garcia-Moreno et al [22]; Fulu et al [23] |

| Sexual IPV | 3 items (exposure = experience of any act 1 or more times) | Typical item for women: In the past 12 months, how many times has your husband used threats or intimidation to get you to have sex when you did not want to? | Garcia-Moreno et al [22]; Fulu et al [23] |

| Emotional IPV | 11 items (exposure = experience of any act 1 or more times) | Typical item for women: In the past 12 months how, many times has your husband insulted you or made you feel bad about yourself? | Garcia-Moreno et al [22]; Fulu et al [23] |

Research implementation and ethics

The local NGO partners secured approval from local formal and informal leaders for the study. Access to villages and written permission to work in the villages was obtained from the local governments of the targeted district after several meetings with relevant local governmental officials to explain the details of the project and the research. The local partners also assisted the research team with the recruitment of respondents, administrative arrangements for the survey, and offering light refreshments to the respondents. The researchers ensured cohort retention by engagement with the families through the intervention and intermittently after the intervention support had finished.

The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the SAMRC’s Human Research Ethics Committee, and written informed consent was obtained from the study participants for the survey in all target villages. The research was informed by the WHO guidelines on research on violence against women [29]. Interviews were conducted by trained interviewers in private and were interrupted if participants expressed distress. Counselling after the interviews for any participants requesting it was available from the NGO partners, but we do not know if services were used.

Analysis of the data

Analysis was by intention to treat; thus, we included all participants enrolled into the intervention at baseline irrespective of their attendance in the intervention training programme. Descriptive statistics such as frequencies, percentages, means, and standard deviations were used to summarise socio-demographic characteristics of participants. We used percentages to summarise categorical or dichotomous outcomes at each data collection point. For scales such as relationship control, depression, gender attitudes, and decision-making scales, we derived a summative score from the item responses and presented mean scores as summary statistics at each time point. The level of missing data varied between items and scales. It was higher at baseline (up to 17%) than for the third and fourth waves (less than 10%). There were no significant differences in the proportion of missing item data between male and female participants. About 20% of participants were lost to follow-up (i.e were available at baseline but not available at either third or fourth data collection waves), with similar distribution between male and female participants. We performed missing data analysis to assess if there were any baseline socio-demographic factors that were associated with loss to follow-up. We defined loss to follow-up as not being available for interviews at 15th and 30th months (third and fourth data waves). We found no association between loss to follow-up and socio-demographic factors or with any of the study outcomes. In order to maintain the sample size, we used multiple imputation to deal with missing data in the item responses for continuous study outcomes at each data collection. Generalised random effects regression models were used to assess the trend in proportions or mean score over time, with each participant as a random component (cluster) in the model. Study time points were entered as the main exposure and were used to determine trends in each outcome measure over time. All random effects models were adjusted for the age of the participants and all analyses were done in Stata 14. We analysed the data for male and female participants separately.

Results

Social and demographic characteristics

The ages of the respondents ranged from 16 to 65 years old, and the women were a little younger than the men and most were currently married (Table 2). The proportion of ethnic Tajiks and Uzbeks was almost equal. Men were significantly more likely to have studied beyond secondary school than the women (59.8% vs. 27.6%). Women reported, much more commonly than men, living with their spouse’s family (39.0% vs. 5.9%), and 32.2% of women and 24.7% of men were living in a nuclear family (spouse and children). More women were reported to be in a polygamous marriage than men (14.9% vs. 4.9%). Labour migration patterns were heavily gendered, with 49.0% of men and only 8.2% of women having ever migrated for work.

Table 2.

Social and demographic characteristics of participants at baseline.

| Women (N = 134) |

Men (N = 102) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| Age group (women: n = 131; men: n = 100) | ||||

| 16–24 yrs | 22.0 | 16.8 | 13.0 | 13.0 |

| 25–34 yrs | 47.0 | 35.9 | 30.0 | 30.0 |

| 35–44 yrs | 25.0 | 19.1 | 18.0 | 18.0 |

| 45–54 yrs | 18.0 | 13.7 | 10.0 | 10.0 |

| ≥55 yrs | 19.0 | 14.5 | 29.0 | 29.0 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Tajik | 67.0 | 50.0 | 46.0 | 45.1 |

| Uzbek | 62.0 | 46.3 | 50.0 | 49.0 |

| Other | 5.0 | 3.7 | 6.0 | 5.9 |

| Education level (men n = 99) | ||||

| None | 6.0 | 4.5 | 2.0 | 2.0 |

| Primary | 11.0 | 8.2 | 5.0 | 5.1 |

| Secondary | 78.0 | 58.2 | 30.0 | 30.3 |

| Above secondary | 39.0 | 29.1 | 62.0 | 62.6 |

| Currently married | 92.0 | 68.7 | 78.0 | 76.5 |

| Married to a relative | 29.0 | 21.6 | 10.0 | 9.8 |

| Living arrangements | ||||

| Lives with husband/wife and children | 38.0 | 32.2 | 21.0 | 24.7 |

| With husband’s family (women) or wife’s family (men) | 46.0 | 39.0 | 5.0 | 5.9 |

| With husband/wife and own family | 6.0 | 5.1 | 39.0 | 45.9 |

| Living with children without a spouse | 13.0 | 11.0 | 14.0 | 16.5 |

| Living with natal family (no spouse or children) | 12.0 | 10.2 | 6.0 | 7.1 |

| Living alone | 3.0 | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| In polygamous marriage | 20.0 | 14.9 | 5.0 | 4.9 |

| Ever migrated for work | 11.0 | 8.2 | 50.0 | 49.0 |

| Average number of children (SD) | 4.0 | 1.9 | 5.0 | 4.9 |

Socio-economic status

At baseline, the socio-economic status of the participating families was low. Over the 3 months prior to the survey, less than a quarter of women (23.9%) and only just over half of men (54.9%) had earned money. Only 6.7% of women and 22.6% of men had any savings. Most men and women perceived it would be difficult to raise 500 Somonis (at the time, US$ 63.5) in case of an emergency. Most women and men said that they had borrowed money or food in the previous month due to not having enough (61.9% women and 54.8% men) and disclosed severe food insecurity (55.7% of women and 33.8% of men). Their socio-economic position caused them considerable stress and shame.

Over the period of 30 months, there were significant positive changes in the economic situation of the families, and most of these changes were reported as starting in the first year (Table 3). Substantial increases were seen in the proportion of women and men with earnings and savings in past month, and the proportion with overall savings. At 30 months, 56.6% of women and 72.0% of men had earned money in the past month, and 40.6% of women and 51.2% of men had savings. There was some reduction in the proportion of women with earnings and savings from 15 months to 30 months, but the proportion earning was still more than three times higher than that at baseline. The proportion of men with earnings and savings was sustained between 15 and 30 months. The positive changes in socio-economic indicators were mirrored by reports of change from the qualitative research and monitoring data [30].

Table 3.

Trends over time in socio-economic status of participants.

| Baseline | 8 m | 15 m | 30 m | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mean/% | mean/% | mean/% | mean/% | Coefficient (95% CI) | P value | |

| Women | n = 134 | n = 153 | n = 153 | n = 143 | ||

| Any earnings in past month (%) | 17.9 | 63.4 | 78.9 | 56.6 | 0.03(0.01,0.05) | 0.001 |

| Any savings in past month (%) | 6.7 | 43.8 | 55.1 | 40.6 | 0.03(0.01,0.04) | 0.002 |

| Any overall savings (%) | 6.7 | 59.5 | 62.2 | 53.9 | 0.04(0.02,0.05) | <0.001 |

| Done something to earn money in last 3 months (%) | 23.9 | 66.0 | 79.5 | 55.2 | 0.02(−0.001,0.03) | 0.065 |

| Difficult to find 500 Somonis in an emergency (%) | 87.3 | 13.7 | 10.9 | 22.4 | −0.08(−0.10, −0.06) | <0.001 |

| Borrowed food or money in past month because there was not enough (%) | 61.9 | 39.9 | 35.9 | 34.3 | −0.03(−0.05, −0.02) | <0.001 |

| Severely food insecure v. moderate or none (%) | 44.0 | 19.7 | 19.4 | 2.8 | −0.14(−0.17, −0.10) | <0.001 |

| Effort to get a job or earning money by selling or making things score (high = more effort) | 10.6 | 9.9 | 11.5 | 10.7 | 0.02(0.004, 0.05) | 0.022 |

| Stress due to not having work or enough money (high = more stress) | 10.9 | 10.8 | 9.4 | 8.5 | −0.08(−0.10, −0.07) | <0.001 |

| Shame and despondency due to lack of work (high = more shame) | 10.7 | 8.4 | 7.5 | 6.5 | −0.11(−0.13, −0.10) | <0.001 |

| Men | n = 102 | n = 89 | n = 93 | n = 82 | ||

| Any earnings in past month (%) | 44.1 | 69.7 | 71.0 | 72.0 | 0.05(0.02, 0.07) | 0.001 |

| Any savings in past month (%) | 14.7 | 43.8 | 44.1 | 51.2 | 0.05(0.03, 0.08) | <0.001 |

| Any overall savings (%) | 22.6 | 69.7 | 66.7 | 72.0 | 0.07(0.04, 0.10) | <0.001 |

| Done something to earn money in last 3 months (%) | 54.9 | 68.5 | 77.4 | 73.3 | 0.03(−0.003, 0.05) | 0.083 |

| Difficult to find 500 Somonis in an emergency (%) | 87.3 | 86.5 | 85.0 | 70.7 | −0.06(−0.09, −0.03) | <0.001 |

| Borrowed food or money in past month because there was not enough (%) | 57.8 | 33.7 | 10.8 | 13.4 | −0.12(−0.16, −0.08) | <0.001 |

| Severely food insecure v. moderate or none (%) | 33.8 | 4.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −1.55(−2.38, −0.71) | <0.001 |

| Effort to get a job or earning money by selling or making things score (high = more effort) | 8.4 | 8.5 | 9.6 | 9.0 | 0.02(−0.01, 0.04) | 0.169 |

| Stress due to not having work or enough money (high = more stress) | 10.9 | 10.0 | 8.7 | 8.9 | −0.04(−0.07, −0.02) | 0.001 |

| Shame and despondency due to lack of work (high = more shame) | 11.5 | 9.3 | 8.1 | 8.1 | −0.06(−0.08, −0.03) | <0.001 |

Only two of the trends in socio-economic indicators were not statistically significant. One was the indicator of men’s efforts to get a job or earn, which showed improvement over the period from baseline to 30 months, although the highest score was at 15 months. The change in this measure was significant for women, although the actual scores did not show a convincing change. The other measure was the proportion of women and men doing something to earn money in the past 3 months, which increased twofold for women between baseline and 30 months (from 23.9% to 55.2%) and by one-third for men (from 54.9% to 73.3%), albeit with some back sliding from the 15 months highs at the end of the intervention, but these changes were not statistically significant.

Mental health outcomes

At baseline, mental health and general health in the participant families were poor. The mean score of the CES-D depression scale for women and men were 28.5 and 17.9, respectively; both were above the commonly used cut points for substantial depression symptomatology (16+) (Table 4). In the previous 4 weeks, 12.9% of women and 4.9% of men had had suicidal thoughts. A disability due to a health problem was reported by 9.4% of women and 8.4% of men. Less than three-quarters of women and men (73.9% and 68.6%) described their health as fair, good, or excellent at baseline; the others perceiving it to be poor or very poor.

Table 4.

Trends in mental health outcomes.

| Baseline | 8 m | 15 m | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %/mean | %/mean | %/mean | 30 m | Coefficient (95% CI) | P value | |

| Women | n = 134 | n = 153 | n = 153 | n = 143 | ||

| Depression score (low = good) | 28.5 | 17.4 | 15.1 | 13.6 | −0.36(−0.42, −0.30) | <0.001 |

| Hope scale (high = more hopeful) | 17.1 | 18.8 | 18.3 | 18.6 | 0.02(0.01, 0.04) | 0.009 |

| Disability score (high = more disability) | 9.5 | 7.0 | 7.9 | 7.6 | −0.03(−0.10, −0.02) | <0.001 |

| Suicidal thoughts in last 4 weeks (%) | 12.5 | 1.3 | 0.6 | 2.1 | −0.06(−0.1, −0.02) | 0.001 |

| Fair, good, or excellent general health (%) | 73.9 | 91.5 | 93.6 | 91.6 | 0.04(0.01, 0.07) | 0.006 |

| Men | n = 102 | n = 89 | n = 93 | n = 82 | ||

| Depression score (low = good) | 17.9 | 10.5 | 6.9 | 8.4 | −0.25(−0.3, −0.19) | <0.001 |

| Hope scale (high = more hopeful) | 16.9 | 18.0 | 18.4 | 18.4 | 0.06(0.04, 0.08) | <0.001 |

| Disability score (high = more disability) | 8.4 | 6.9 | 6.8 | 6.6 | −0.04(−0.05, −0.03) | <0.001 |

| Suicidal thoughts in last 4 weeks (%) | 4.9 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.47(−0.81, −0.13) | 0.007 |

| Fair, good, or excellent general health (%) | 68.6 | 96.6 | 97.9 | 92.7 | 0.07(0.02, 0.12) | 0.003 |

Over the time of the research, there was a significant and sustained decrease in depression among both women and men and a significant positive change in hope (Table 5). The 30-month mean depression scores were well within the non-depressed range for both women and men (13.6 and 8.4). The high proportion of women with suicidal thoughts at baseline was significantly reduced with only 2.1% of women and no men reporting suicidal thoughts in the past month at 30 months. The disability scores for men and women also significantly reduced. Self-rated health also improved, with 91.6% of women and 92.7% of men rating themselves as being in fair, good, or excellent health at the end line, a substantial improvement from baseline.

Table 5.

Trends over time in gender attitudes and relationships.

| Baseline | 8 m | 15 m | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| %/mean | %/mean | %/mean | 30 m | Coefficient (95% CI) | P value | |

| Women | n = 134 | n = 153 | n = 153 | n = 143 | ||

| Individual gender attitudes (high = patriarchal) | 49.8 | 49.0 | 46.1 | 45.2 | −0.16(−0.19, −0.12) | <0.001 |

| Community attitudes (high = patriarchal) | 53.6 | 52.1 | 48.0 | 48.2 | −0.18(−0.23, −0.14) | <0.001 |

| Woman’s relationship with husband (high = better relationship) (4 items) | 10.4 | 9.8 | 9.4 | 10.3 | 0(−0.01, 0.01) | 0.802 |

| Woman’s mother-in-law cruel (high = more cruel) (4 items)* | 9.9 | 8.7 | 8.0 | 9.0 | −0.01(−0.04, 0.01) | 0.271 |

| Woman’s mother-in-law kind (high = more kind) (3 items)* | 7.4 | 8.3 | 8.8 | 7.6 | −0.01(−0.03, 0.0) | 0.117 |

| Woman involvement in decision-making (high = more involvement) | 7.3 | 9.0 | 10.0 | 10.1 | 0.07(0.05, 0.01) | <0.001 |

| Women controlled by husband (high = more control) | 20.8 | 18.6 | 19.3 | 18.7 | −0.03(−0.05, 0.0) | 0.024 |

| Quarrelling frequently (%) | 12.7 | 4.6 | 4.5 | 5.6 | −0.02(−0.06, 0.01) | 0.232 |

| Husband drinks alcohol (%) | 27.6 | 17.7 | 12.2 | 16.1 | −0.02(−0.05, 0.0) | 0.088 |

| Men | n = 102 | n = 89 | n = 93 | n = 82 | ||

| Individual gender attitudes (high = patriarchal) | 52.8 | 46.3 | 41.2 | 42.9 | −0.27(−0.34, −0.19) | <0.001 |

| Community attitudes (high = patriarchal) | 53.7 | 52.7 | 46.5 | 45.7 | −0.27(−0.32, −0.22) | <0.001 |

| Man’s relationship with wife (high = better relationship) (5 items) | 15.3 | 16.1 | 16.9 | 16.2 | 0.01(−0.01, 0.03) | 0.186 |

| Man’s mother cruel (high = more cruel) (2 items)* | 4.4 | 3.4 | 2.5 | 3.2 | −0.03(−0.05, −0.01) | 0.006 |

| Man’s mother kind (high = more kind) 3 items* | 9.7 | 9.5 | 9.6 | 9.5 | 0(−0.03, 0.02) | 0.811 |

| Woman involvement in decision-making (high = more involvement) | 8.1 | 7.6 | 8.7 | 9.8 | 0.07(0.05, 0.10) | <0.001 |

| Women controlled by husband (high = more control) | 19.5 | 17.8 | 16.3 | 16.1 | −0.08(−0.11, −0.05) | <0.001 |

| Quarrelling frequently (%) | 5.9 | 3.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | −0.03(−0.12, 0.06) | 0.468 |

| Alcohol use in past year (%) | 34.3 | 41.6 | 23.7 | 14.6 | −0.08(−0.12, −0.03) | 0.001 |

*Analysis of married women and men aged <40 years.

Gender attitudes and relationships

Across the four-time points, women and men’s gender attitudes became significantly more equitable, with notable change in the views of men. In parallel with this, women and men perceived changes in social norms in the community, perceiving these also to become more equitable (Table 5). Women and men both reported over time significantly greater involvement of women in decision-making, and women and men reported significantly less controlling behaviour by husbands towards their wives. Men reported significantly less alcohol use over the time, and women also reported their husbands drinking less, although this indicator was not statistically significant despite the magnitude of change being great. Both men and women reported substantial reductions in their having frequent quarrels, this halved for women and reduced to zero reports for men, but the differences were not statistically significant.

The impact on some domains of household relations was less clear. Men reported that their relationship with their wife had improved, although there was some backsliding from 15 to 30 months, and the trend was not statistically significant. Women, however, did not report any improvement in their relationship with their husband. Women reported a reduction in cruelty from their mother-in-law and an increase in perceptions of her kindness, particularly between baseline and 15 months, but there was some backsliding at 30 months, although still showing overall improvement. The trend was not statistically significant. Men, however, reported that their mother’s relationship with their wives was significantly less cruel, but they did not report it to be more kind.

IPV perpetration or experience

The proportion of women reporting experiencing almost all forms of IPV decreased significantly across the time points, and was sustained to the 30 months’ interviews, which was 15 months after the end of the project support for the intervention (Table 6). Men’s reports of perpetration were at all points lower than reports of women but also decreased across the project, with the reductions sustained after the end of the intervention. The one exception was women’s reports of sexual IPV, which declined very greatly from baseline to 15 months, but at 30 months, were close to the levels reported at 8 months. This was not a significant decline, but it was a reduction of 50% from baseline.

Table 6.

Trends in IPV experience and perpetration of currently married women and men.

| Baseline | 8 m | 15 m | 30 m | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | % | % | Coefficient (95% CI) | P value | |

| Women | n = 107 | n = 131 | n = 133 | n = 121 | ||

| Physical IPV in past 12 months | 44.9 | 20.6 | 16.5 | 15.7 | −0.05(−0.08, −0.03) | <0.001 |

| Sexual IPV in past 12 months | 29.0 | 15.3 | 3.8 | 14.9 | −0.02(−0.05, 0.0) | 0.089 |

| Physical or sexual IPV in past 12 months | 47.7 | 29.8 | 18.1 | 24.8 | −0.03(−0.05, −0.01) | 0.008 |

| Emotional IPV in past 12 months | 64.5 | 43.5 | 32.3 | 28.1 | −0.06(−0.08, −0.03) | <0.001 |

| Severe sexual or physical IPV (more than 2 acts) in past 12 months | 42.1 | 22.9 | 14.3 | 16.5 | −0.05(−0.07, −0.02) | 0.001 |

| Emotional, sexual, or physical IPV in past 12 months | 66.4 | 49.6 | 33.1 | 37.2 | −0.04(−0.06, −0.02) | <0.001 |

| Men | n = 87 | n = 85 | n = 85 | n = 87 | ||

| Physical IPV in past 12 months | 28.7 | 9.4 | 0.0 | 2.6 | −0.21(−0.33, −0.1) | <0.001 |

| Sexual IPV in past 12 months | 21.8 | 10.6 | 0.0 | 1.3 | −0.22(−0.35, −0.09) | 0.001 |

| Physical or sexual IPV in past 12 months | 33.3 | 15.3 | 0.0 | 3.9 | −0.16(−0.24, −0.08) | <0.001 |

| Emotional IPV in past 12 months | 44.8 | 21.2 | 4.6 | 6.4 | −0.13(−0.18, −0.07) | <0.001 |

| Severe sexual or physical IPV (more than 2 acts) in past 12 months | 28.7 | 9.4 | 0.0 | 2.6 | −0.20(−0.32, −0.09) | <0.001 |

| Emotional, sexual, or physical IPV in past 12 months | 48.3 | 24.7 | 4.6 | 7.7 | −0.12(−0.17, −0.07) | <0.001 |

Discussion

The findings of the quantitative research, supported by those of qualitative research published elsewhere [30], suggest that Zindagii Shoista had a very substantial impact on the lives of the families participating, particularly the younger women in the families. There was a marked improvement in socio-economic status, and reports of physical, sexual, and emotional IPV in the past year reported by women more or less halved, and this was supported generally by significantly lower reports of perpetration by men, although the latter reports may have been less reliable. The reports of a decline in IPV were supported by evidence of a significant decrease in depression among both women and men, more equitable gender attitudes, and perceived social norms in the community and less controlling behaviour towards women. These findings were supported by the qualitative research, which provided specific examples of changes in gendered practices and family relations [30].

For the most part, the changes reported were sustained more or less across the period from baseline to 30 months, that is 15 months after the end of the project support. While there were some reductions in indicators of women’s earnings and savings between 15 and 30 months, the positive results of the intervention largely were broadly sustained over the period from 15 to 30 months. There was some backsliding on some of the measures of relations between the mother-in-law and daughter-in-law and husband and wife between 15 and 30 months, which resulted in the overall trend not showing significant change. These may have been real changes, outside the gaze of the project team, or there could be a weakness in the measures as they were investigator-designed for the survey, and it is possible that they had not been sufficiently tested and optimised. The changes across the more established measures were more consistent.

To our knowledge, our research is the one of very few evaluations of interventions to prevent violence against women ever conducted in Tajikistan, or in the wider Central Asian region. This intervention was lightly adapted for use in Nepal where it was named the Sammanit Jeevan. It was evaluated with a very similar mixed methods study design, and the results of the evaluation similarly show considerable evidence of success in enhancing gender relations and family harmony [31]. The findings show that the intervention in Nepal was promising, and the economic aspect was very successful after the first year, but there were some differences in the research methods and the findings in respect of gender relations were stronger in Tajikistan.

The main strengths of the evaluation lie in the fact the quantitative findings were triangulated with qualitative research as well as monitoring data, which include compilation of a case study of each family. The findings of all data were supportive, and, in many respects, the qualitative data provided the most powerful examples of change. There was comparatively little loss of participants from the quantitative research cohort across the time points, and standard measures were used for each assessment. The project approach and methodologies were discussed and agreed among local and international project partners, and the local context was reflected in the project methodologies, drawing on the findings of the formative research [8], and included a range of measures developed for the study, particularly around mother-in-law and daughter-in-law relations. The limitations of the research include the small sample size and the lack of a control arm, which prevented comparison of families who had and had not had the intervention. Labour migration posed a major challenge as it meant that young men were not all around all the time during the intervention and research. However, we have greater confidence in the findings given that we have four data points, and all the findings were triangulated.

Conclusion

The Zindagii Shoista intervention is one of the first evidence-based interventions to prevent violence against women in Tajikistan, and to our knowledge, the first to address the overlapping problems of poverty, patriarchy, and violence against women through a family focus. The research findings together show that the intervention approach shows particular promise in reducing IPV and other domestic violence against young women while simultaneously improving livelihoods, family dynamics, and emotional well-being. There is now evidence to support its promise from both Nepal and Tajikistan, which shows clearly that further research is warranted to assess the intervention’s effectiveness.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Zindagii Shoista participants for embarking on this journey with us and sharing their time and life stories. We would also like to thank the dedicated staff of our partner organisations ATO, Farodis and Zanoni Sharq for their tireless commitment to this project as well as our colleagues in our respective institutions and the What Works consortium for their support.

Biographies

Subhiya Mastonshoeva Conceptualisation, Project Administration, Methodology, Writing – Original Draft.

Shahribonu Shonasimova Conceptualisation, Project Management, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing, Funding Acquisition.

Parvina Gulyamova Conceptualisation, Project Administration, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing.

Rachel Jewkes Conceptualisation, Methodology, Writing – Original draft.

Nwabisa Shai Conceptualisation, Methodology, Writing – Review & Editing.

Esnat Chirwa: Data analysis.

Henri Myrttinen Conceptualisation, Methodology, Writing – Original draft, Funding Acquisition.

Responsible Editor

Julia Schröders

Funding Statement

The intervention and research have been funded by UK Aid from the UK government, via the What Works to Prevent Violence Against Women and Girls Global Programme. The funds were managed by the South African Medical Research Council. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Ethics and consent

The research received ethical approval by the Ethics Committee of the South African Medical Research Council EC032-9/2015. Informed consent was obtained from all participants interviewed in the study.

Paper context

In Tajikistan, the high prevalence of violence against women and girls (VAWG) is driven by the nexus of patriarchy and poverty, as they intersect in multi-generational family units. We describe an evaluation of Zindagii Shoista, the first theoretically grounded, multi-generational approach to prevent VAWG in Tajikistan. Economic empowerment and gender-transformative approach showed a strong and sustained impact on gender relations and economic indicators. Further implementation and evaluation are indicated in Tajikistan and similar settings.

References

- [1].World Health Organization . Violence against women. Report on the 1999 WHO pilot survey in Tajikistan. EUR/00/5019784, Copenhagen: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Prevention of Domestic Violence Project (PVD) . End-of-Phase appraisal. Final report, cited in Erich A (2015) From ‘programme transplants’ to ‘local approaches’: the prevention of domestic violence against women in Tajikistan [Unpublished PhD thesis]. Fakultät für Geisteswissenschaften der Universität Hamburg. Bad Homburg/Dushanbe Universität Hamburg; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Erich A. From ‘programme transplants’ to ‘local approaches’: the prevention of domestic violence against women in. Tajikistan: der Universität Hamburg; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Haarr R. Suicidality among battered women in Tajikistan. Violence against Women. 2010;16:764–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Haarr R. Wife abuse in Tajikistan. Fem Criminol. 2007;2:254–270. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Harris C. Control and subversion: gender relations in Tajikistan. Sterling: Pluto Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Harris C. Muslim youth - tensions and transitions in Tajikistan. Boulder: Westview Press.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [8].Mastonshoeva S, Ibragimov U, Myrttinen H. Zindagii Shoista: living with dignity – research findings of the formative research. Dushanbe/Pretoria: International Alert/CESVI/SAMRC; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kerr-Wilson A, Fraser E, Gibbs A, et al. What works to prevent violence against women and girls? Evidence review of interventions to prevent violence against women and girls 2000-19. Pretoria: South African Medical Research Council; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- [10].Pronyk P, Hargreaves JR, Kim JC, et al. Effect of a structural intervention for the prevention of intimate partner violence and HIV in rural South Africa: a cluster randomised trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1973–1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Haushofer J, Shapiro J. The short-term impact of unconditional cash transfers to the poor: experimental evidence from Kenya. Q J Econ. 2016. Nov;131:1973–2042. PubMed PMID: 33087990; eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Gibbs A, Corboz J, Chirwa E, et al. The impacts of combined social and economic empowerment training on intimate partner violence, depression, gender norms and livelihoods among women: an individually randomised controlled trial and qualitative study in Afghanistan. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5:e001946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Gibbs A, Jewkes R, Sikweyiya Y, et al. Reconstructing masculinity? A qualitative evaluation of the stepping stones and creating futures intervention in urban informal settlements in South Africa. Cult Health Sex. 2014. DOI: 10.1080/13691058.2014.966150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Jewkes R, Shai N. Zindagii Shoista. Living with Dignity. Workshop manual. Part 1. Dushanbe: International Alert; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- [15].Gulyamova P, Balboni S, Jewkes R, et al. Zingadii Shoista (Living with dignity) workshop manual Part 2: enabling economic empowerment through income generating activities. Pretoria: South African Medical Research Council, Cesvi and International Alert; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [16].Mastonshoeva S, Myrrtinen H, Chirwa E, et al. Evaluation of Zindagii Shoista (Living with Dignity), an intervention to prevent violence against women in Tajikistan: impact after 30. months Pretoria: SAMRC; 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Jewkes R, Nduna M, Jama-Shai N. Stepping stones South Africa: a training manual for sexual and reproductive health communication and relationship skills. Pretoria: MRC; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [18].Misselhorn A, Jama Shai N, Mushinga M, et al. Creating futures. Durban: HEARD/Medical Research Council; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- [19].Falkingham J, Baschieri A. Gender and poverty: how misleading is the unitary model of household resources? An illustration from Tajikistan. Global Social Policy. 2009;9:43–62. [Google Scholar]

- [20].Jewkes R, Sikweyiya Y, Morrell R, et al. Gender inequitable masculinity and sexual entitlement in rape perpetration South Africa: findings of a cross-sectional study. PloS One. 2011;6:e29590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Jewkes R, Nduna M, Levin J, et al. Impact of stepping stones on incidence of HIV, HSV-2 and sexual behaviour in rural South Africa: cluster randomised controlled trial. Br Med J. 2008;337:a506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Garcia-Moreno C, Jansen HA, Ellsberg M, et al. Prevalence of intimate partner violence: findings from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence. Lancet. 2006. Oct 7;368:1260–1269. PubMed PMID: 17027732; eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Fulu E, Jewkes R, Roselli T, et al. Prevalence and risk factors for male perpetration of intimate partner violence: findings from the UN multi-country study on men and violence in Asia and the Pacific. Lancet Glob Health. 2013;1(4):e187–e207 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Coates J, Swindale A, Bilinsky P. Household Food Insecurity Access Scale (HFIAS) for measurement of food access: indicator guide. Washington (DC): Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- [25].Barker G, Contreras JM, Heilman B, et al. Evolving men: initial results from the International Men and Gender Equality Survey (IMAGES). Washington DC: International Center for Research on Women; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- [26].Radloff L. The CES-D scale: a self report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- [27].Madans JH, Loeb ME, Altman B. Measuring disability and monitoring the UN convention on the rights of persons with disabilities: the work of the Washington group on disability statistics. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Jewkes RK, Levin JB, Penn-Kekana LA. Gender inequalities, intimate partner violence and HIV preventive practices: findings of a South African cross-sectional study. Soc sci med (1982). 2003. Jan;56(1):125–134. PubMed PMID: 12435556; eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].World Health Organization . Putting women first: ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence against women. Geneva (CH): World Health Organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Mastonshoeva S, Myrttinen H, Jewkes R, et al. Development, implementation and qualitative evaluation of Zindagii Shoista (Living with dignity) intervention to prevent violence against women in Tajikistan. Dev Pract. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Shai N, Pradhan G, Shrestha R, et al. “I got courage from knowing that even a daughter-in-law can earn her living”: evaluation of a family-centred intervention to prevent violence against women and girls in Nepal. PLOS One. 2020;15(5):e0232256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]