Abstract

The primary objective of this article is to consider the impact of the coronavirus disease-19 pandemic on pediatric anxiety from both a clinical and system-of-care lens. This includes illustrating the impact of the pandemic on pediatric anxiety disorders and consideration of factors important for special populations, including children with disabilities and learning differences. We consider the clinical, educational, and public health implications for addressing mental health needs like anxiety disorders and how we might promote better outcomes, particularly for vulnerable children and youth.

Keywords: Anxiety disorders, COVID-19 pandemic, Special populations, Disabilities, Children, Adolescents, System of care, Schools

Key points

-

•

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a disproportionate impact on communities of color and on under-resourced communities by imposing additional psychosocial stressors that contributed to persistent anxiety, worries, and distress for many children and adolescents.

-

•

Anxiety disorders and stress have been notable aspects of young people’s experience during the pandemic, and it will be important to consider ways to respond to anxiety and stress as we move into a recovery phase.

-

•

Intersectional identities are relevant to the experiences of young people during the pandemic, and this is important to think about for planning prevention and treatment interventions for anxiety and related stressors.

-

•

Youth from minoritized backgrounds with mental health and learning disabilities that predated the pandemic are potentially more vulnerable to experiencing anxiety disorders.

-

•

A combined clinical and system of care approach that includes identifying and addressing the specific needs of children and adolescents, implementing prevention, and resilience-promoting interventions within clinical services, schools, families, and the community are needed going forward.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a dramatic increase in the rate of anxiety problems and social risks among children, adolescents, and young adults in the United States and globally. The stressors heralded in by the pandemic disproportionately affected racial- minoritized and ethnic-minoritized school-age children, adolescents, and young adults.1 This is in context of pre-existing social inequities and growing mental health services needs experienced by children and adolescents more broadly. Even before the pandemic, there were already escalating rates of inpatient visits for suicide, suicidal ideation, and self-injury for children aged 1 to 17 years old, and just in the first 10 months of 2020, there was a 151% increase in these concerns for children aged 10 to 14.2 There has been a 61% increase in the rate of self-reported mental health needs since 2005.3 Anxiety has been an important problem to consider since the pandemic; one national survey found that more than one in four children report sleep problems due to worries, feeling unhappy, and anxious.4 In this review, we offer findings from recent studies on anxiety, particularly patterns identified during the pandemic. We also consider case illustrations and recommendations for assessment, clinical care, and system-based approaches for treatment and prevention.

Pandemic-Driven Anxiety and Mental Health Problems in Children and Adolescents

The mental health needs of youth shifted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Rates of psychological distress among young people, including symptoms of anxiety disorders (eg, generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorders, separation anxiety) and other broad anxiety symptoms (eg, worry and fears), and depression have worsened. Recent research covering 80,000 youths globally found that depressive and anxiety symptoms doubled during the pandemic with 20% of youth reporting that they are experiencing significant anxiety symptoms.5 There are several potential reasons. During the pandemic, children, adolescents, and young adults have faced unprecedented challenges as the pandemic radically changed their world, including how children and youths have attended school and been socialized. They missed important events, time with friends and teachers, and time with relatives. A recent study6 showed that children who already had subjective anxiety about their parents and themselves at baseline also had increased anxiety sensitivity, including what has been termed coronavirus anxiety (eg, feeling dizzy, lightheaded, faint, paralyzed, frozen, or other intense anxiety feelings when thinking about or exposed to information about the coronavirus). A study of distal and proximal predictors of child mental health found the pandemic to be a mediator between maternal history of adverse childhood experiences and her child’s traumatic stress symptoms, which were also associated with internalizing symptoms before the pandemic.7 Loneliness, social distancing, and internet usage also strongly correlated with mental health-related issues including stress, anxiety, and depression.6

Youths with intersectional identities, such as minoritized youths with low socioeconomic status, homeless youths, and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ) youths, have been especially vulnerable during the pandemic given the increased risks they have faced. LGBTQ youths have experienced disproportionate negative outcomes in housing stability, employment, and mental health and trauma due to COVID-19 resulting from the combination of their sexual and gender identity discrimination, foster care involvement, and lower socioeconomic status.8 Youths from the Asian and Pacific Islander communities have experienced an increase in abuse and discrimination, given the uptick in anti-Asian rhetoric and hate crimes that escalated during the pandemic.9 These discriminatory experiences have continued unabated and have resulted in the clinical presentation of generalized anxiety, social anxiety, and depression for many children and adolescents who, as a result, worry about their safety and that of their elders.10

Children, youths, and their families experienced multiple stressors throughout the pandemic. Some may have lost access to mental health care, social services, income, food, or housing. Some children may have had COVID-19 themselves, suffered from long COVID symptoms, or lost a loved one to COVID-related illness. Recent published estimates suggest that more than 200,000 children in the United States have lost a parent or grandparent caregiver to COVID-19.11 COVID-19 disproportionately affected the Black, Latinx, and other children and adolescents of color, where adult family members were more likely to be affected front-line workers. Cumulative data from the state of California indicate that the Latinos overall, and Latino children specifically, are over-represented in both infection rates and mortality rates.12 A study found that presenting to a health clinic with possible COVID-19 symptoms, being polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-positive for COVID-19, or being hospitalized with a verified disease, posed a significant risk to children and adolescents and the development of psychological disorders, including anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and sleep disturbances.13

Spencer and collegues14 assessed mental health symptoms and social risks during COVID-19 versus before the pandemic among urban, racial- minority and ethnic-minority school-aged children. The analysis included caregivers of 168 children (aged 5 to 11 years old) recruited from an urban safety-net hospital-based pediatric primary care practice with follow-up from September 2019 to January 2021.14 The researchers found that children had significantly higher levels of emotional and behavioral symptoms mid-pandemic versus pre-pandemic across all domains. During the pandemic, significantly more children reported clinical concerns and had positive pediatric symptom checklist screenings in primary care and mental health services. The caregivers reported significantly more social risks and behavioral changes in their children during the pandemic. The researchers found significant associations between less school assignment completion, increased screen time, and caregiver depression with worse mid-pandemic mental health in children. Although other research has suggested that bullying, cyberbullying, sexting, and fighting showed only small or no increases, anxiety and depression have dramatically increased relative to before the pandemic.15

One study pooled the estimates obtained from the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic5 that suggested one in five youth were experiencing clinically elevated anxiety symptoms. The authors concluded that an influx of mental health care utilization is expected, and the allocation of resources to address child and adolescent mental health concerns is essential. There was a correlation observed between mental health symptoms during the pandemic and the number of social risks before the pandemic. Girls and LGBTQ youths were particularly vulnerable during the months following the shelter-in-place requirements that were initiated in March 2020. Girls and LGBTQ youths experienced a greater risk of anxiety and depression, even as cyberbullying and other online threats were relatively unchanged. This increase in symptoms was at least in part attributed to a reduction in access to social support and an increase in psychosocial stressors in the context of the pandemic.15 Unhoused youths were at particular risk. One study found that young adults experiencing homelessness experienced more stressors compared with housed peers, described unmet basic needs, frustration, and anxiety, and increases in risk behaviors including substance use.16 Youths with chronic medical conditions such as diabetes were also at risk of poor disease management, stress, and anxiety which increased their vulnerability to medical emergencies during the pandemic.17

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis examined the prevalence of anxiety disorders in the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. Delpino et al. (2022) reviewed 194 studies that assessed the prevalence of anxiety among the general population globally during the pandemic. The general prevalence of anxiety was 35.1%, affecting approximately 851,000 participants across the studies. The prevalence in low- income and middle-income countries (35.1%; 95% CI: 29.5%–41.0%) was similar compared to high-income countries (34.7%; 95% CI: 29.6%–40.1%).18 In addition to reporting on the prevalence of anxiety disorders and the high impact across demographics, the authors note that one in 10 cases with anxiety during COVID-19 may be continuing to live with clinically meaningful anxiety symptoms. The challenge is identifying and helping the children and youths who are most in need.

Children with special needs: returning to school and catching up

Crucially, remote learning at the height of the pandemic disrupted educational trajectories and school-based services. Children requiring special education and other specialized services struggled more than peers without such needs.19 It is important to consider how the combination of educationally-based stressors, learning disabilities, and other social factors can contribute to anxiety and exacerbate other pre-existing developmental and mental health conditions. The following clinical case studies illustrate some of these factors.

Clinical Case Studies

Carl’s story

“Carl” is a 14-year-old boy with inattentive Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and dyslexia. Right before the pandemic, he had started his freshman year at a new school with all new peers. He was taking prescribed ADHD medication, but not enough to help him fully manage his restlessness in the classroom. He faced additional pressures across racial differences as one of the few Black students at the school, too often subjected to disproportional discipline, as was the case for other students of color at the high school. He started to complain that he hated school because of these interactions and he did not have enough positive experiences to strike a balance. He said that his classes were too difficult and that it was too hard to stay on task. School was especially challenging when all instruction was conducted via Zoom during shelter-in-place. His parents struggled with how to best support him–taking care of his emotional needs or responding to pressure from teachers to increase their surveillance to keep him on task. They felt there was no middle ground.

For Carl, even physical education was hard when he was sheltering at home because he felt self-conscious exercising in front of his family in the only available space of the living room. He experienced feelings of anxiety and tension because he was unable to read content on the web pages for assignments. Now back at school, he is distracted and does not want to show up for class anymore. His struggles are complicated by his ADHD and learning disabilities. The teachers in his classes require that he do what others are doing, and he feels pressure to read as quickly as his peers in his Language Arts class. He cannot keep up but does not want to show it.

To make the classes more interesting, the teachers use “popcorn” pedagogy, where students randomly select the next person to talk or to read after they have finished their turn. This strategy is engaging for neurotypical students but can make students with learning differences anxious, invoking a fight or flight response. When this happens, Carl often wants to crawl under the table, but instead asks repeatedly to go to the bathroom to get out of class.

During COVID-19 remote learning, students with disabilities like Carl lacked the one-on-one classroom paraprofessional aid they had previously, and schools continue to be short-staffed in providing this resource. At home, at least Carl was able to get up and walk around more easily, using this as an escape strategy when stressed. However, with access to the entire internet to escape, Carl was doing many online activities outside of the class curriculum. Although this helped him manage his anxiety, he ultimately fell further behind. Now he has further to catch up.

Clinical Considerations

One study19 suggested that telehealth and remote learning were often complicated for children with disabilities, widening related disparities as youths re-enter school. Clinical and educational services were not reliably available in school settings. Families are understandably frustrated if their child has been unable to access services legally mandated through the child’s Individualized Educational Plan (IEP). An important first step is to reassess a child’s special education and emotional needs, implement an IEP that is responsive to the child’s current needs, and, whenever possible, in coordination with the mental health clinician. Some considerations.

-

•

Medication checks are an opportunity to ask about other issues, such as isolation and loneliness, frustration, and stress, which medications cannot help. For youth with increasing inattention and/or hyperactivity, the clinical impulse may be to increase ADHD medications or add on an antidepressant or anxiolytic medication for anxiety. In clinical situations such as Carl’s, it is important to examine the full range of circumstances influencing symptoms; assessing what educational, social, and behavioral supports are needed is an essential first step.

-

•

Find out about environmental issues. Intrusive thoughts may be directly connected to pandemic-related worries and hard for the child to stop when the child is stressed and lonely or worried about persistent stressors at home.

-

•

Provide children with strategies to manage their negative self-talk like “this is hard and yet I have to do this all again tomorrow” and address overwhelming thoughts about coping and readjusting to the school setting.

-

•

Offer school-based behavioral health services that include evidence-based treatments such as cognitive behavioral therapy and emotional regulation strategies.

Linda’s Story

Linda is a 5th-grade Latina girl with immigrant parents who are bilingual but Spanish-dominant. Linda is diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) but has received limited services. Her ASD symptoms are mild and she is in mainstream classrooms and had just begun receiving special education support before the pandemic started. Her parents are supportive but unsure how to help her and have received little useful information about ASD. Linda’s sensory issues made remote learning challenging for a variety of reasons. For example, when Linda’s computer was on the Zoom gallery view, there was too much going on, especially when many were learning how to use technology. There were often multiple students unmuted at the same time, and the transmitted background noise from their homes was stressful.

The Zoom video was visually overstimulating for Linda. Her neurotypical peers were able to filter out these distractions, but Linda could not and she became increasingly anxious. She sometimes responded to this overstimulation by skimming, for example, tapping and engaging in repetitive movements that were soothing to her, but these behaviors seemed disruptive for other students, and the teacher and staff responded negatively. Before the pandemic, Linda might also respond to overstimulation by eloping–running away, leaving the classroom, wandering away–which the staff could respond to by gently guiding her back to her seat. However, on Zoom, it was a struggle to keep her engaged in front of the computer as her anxiety rose. The teachers required that she keep her camera on for accountability and that she must remain in her seat; now back at school, the same expectations apply.

Like other children with ASD, Linda’s senses can go into overdrive, and as a result, her anxiety can escalate. This is usually related to sounds, and every noise feels that much louder for her than for her peers. When computer sounds or classroom noise feel too loud, her head feels like it is on a swivel, so she sometimes hits her head “to put it back together.” This behavior draws the attention of her classmates, resulting in increased anxiety for Linda.

Clinical considerations

Students like Linda had difficulty using virtual platforms for education and could not take the breaks they needed. School schedules were not typical schedules and often not a full day of classes. So, the teachers may have felt that they could go without breaks because of these fewer hours. These assumptions may not have been congruent with the needs of students in special education. Now back at school and in the classroom, the youths may be experiencing a need to catch up from losses in their educational, social, and developmental progress. The peers may misunderstand self-soothing behaviors. They then might tease or bully the student, who might then become dysregulated or withdrawn.

Clinicians and teachers should not assume that students with ASD are uninterested in being around children their age. Withdrawal may be a response to poor experiences with peers. Avoidance behaviors may have been exacerbated by the transition to virtual learning and then back to in-person learning, as transitions are a known challenge for those with ASD. Actions that can help include:

-

•

During virtual learning, asking questions about isolation and loneliness. Upon return to in-person instruction, asking about other activities, friends, hobbies, or sports that can help engage the child and getting information about this from parents as well as from teachers.

-

•

Knowing more about the child’s academic strengths and areas of need helps to avoid stereotypes and informs ways that clinicians can support parents in advocating for their children’s education.

-

•

Educators can integrate wellness skills into the school environment that inclusively support neurodiverse youth. There is evidence to support the benefits of school-based yoga programs and physical activity for neurodiverse children and adolescents. This includes improvements in self-concept, subjective well-being, executive function, academic performance, and attention.20

Discussion

Mental Health Provider Well-Being

During the COVID-19, pandemic health care providers found themselves under increased demands in the work environment and their professional and personal lives, creating physical and mental health challenges. The COVID-19 pandemic has posed a great risk to the mental health of health workers. There are additional concerns for staff working with youth with intellectual disabilities. A systematic review of original research examining the mental health of health workers working with people with intellectual disabilities found that many of these workers, including nurses, physiotherapists, health care assistants, social care workers, and personal caregivers, reported they had poor mental health including stress, anxiety, and depression.21

Anxiety and stress have essentially become public health issues and require a system-of-care approach for recovery, treatment, and prevention. Before the pandemic there was an increased demand for mental health providers, specifically, child and adolescent psychiatrists were exiguous.22 With even fewer clinicians available today, there has been increased attention on strategies that rely on peer23 and community health care workers.24 Current studies specific to the pandemic align with the results of a review of the impact of natural disasters suggesting that the youths will need positive social experiences and, in some cases, psychological interventions and treatment to restore emotional equilibrium in the months and years ahead.25 Because of the shortage of individual providers, clinicians may need to cultivate more system- and structurally-based approaches, and community-based or partnered approaches for addressing the public health urgency of the situation. Through the pandemic, technology approaches have also helped to deliver and/or augment care.26 Because there has been an increase in the development and availability of digital technology for mental health,27 these digital resources and related training opportunities should be explored as additional tools for the prevention or reinforcement of clinical services.

Schools and Primary Care

As students return to in-person learning, schools are often ‘ground zero’ where children are identified as needing mental health support. Because schools are uniquely positioned to provide support, they are frequently named in key federal and state policies. The American Rescue Plan Act and the Elementary and Secondary School Emergency Relief Fund, combined with other 2020 pandemic relief funds for schools, are federal responses that have been earmarked for more than $190 Billion in education and health grants available over the next 4 years, some of which can be spent on mental health.28 The money goes to states based on their school-age population, but local school districts have decision-making authority over the lion’s share of it. Ninety percent of the money allocated to states must be reallocated to school districts. Schools have wide discretion over how to spend the money if 20% or more is spent on programs to address learning loss, including summer school and after-school academic programs. Significant behavioral health resources are being provided to schools, through legislative initiatives and funding, but how to implement those effectively remains a critical concern.

Teachers have had a unique pandemic burden in managing student stress, learning new technology and COVID-19 safety protocols, and experiencing their stress, illness, and loss related to COVID-19 infection. An online survey of workers, including 135,488 teachers,29 found that teachers reported a significantly higher prevalence of negative mental health outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic, including anxiety and depression, when compared with health care and office workers. These additional stressors have led to job dissatisfaction and decisions to leave teaching.30 To best support students, we need to support teachers through wellness promotion, stress management, support groups, access to behavioral health services, and other supports.

In primary care, pediatricians are tasked with assessing, triaging, and initiating treatment of common mental health concerns such as anxiety and depression. Complicating the picture is long COVID, or long-term symptoms and consequences related to the infection after the acute stage has passed. The few studies conducted thus far provide initial evidence regarding neuropsychiatric symptoms including headaches, sleep disturbance, difficulty with concentration and memory, fatigue, and irritability,31 With much still unknown, we anticipate a growing need for psychological support. Additionally, strategies and tools for pediatricians and their office staff to address the mental health needs of their patients can include working with schools and obtaining consultation from mental health professionals. These approaches can be framed through a tiered approach.

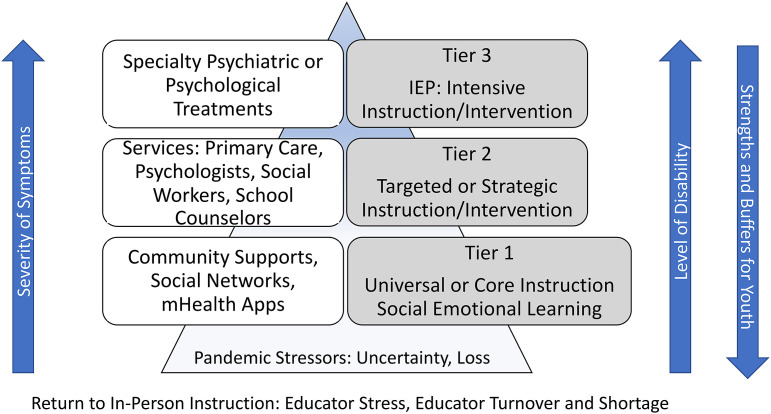

Fig. 1 demonstrates a model for organizing and implementing tiered services within systems of care that integrate psychosocial and mental health treatments, promote strengthening, and enable factors across child-serving systems of care including the school setting and primary care.

Fig. 1.

Tiered psychological services (on left) and instructional supports (on right) for addressing youth anxiety, stress, and mental health needs in the context of pandemic stressors.

Community Networks, Support, and Healing

Yolanda is a 17-year-old adolescent who became the primary caregiver for many of the children in her extended family. The adults in the immediate and extended family, all essential workers, contracted COVID-19 and so separated themselves from the children, while Yolanda took charge of taking care of the siblings and cousins. She helped feed them and complete their schoolwork. This was all while she struggled with her classes and schoolwork. She worried that her parents and the other adults in her life would die. She was also aware that she was important to her family, and that she had helped everyone make it through a very difficult time. During the height of the situation, the anxiety and stress were extremely distressing, but Yolanda recovered well with the support of her family and community. Community resources were critical for maintaining her well-being and contributing to her resilience despite the severity of the stress and anxiety she experienced through the pandemic. The local food hub provided food and made sure that her family had enough to eat even when her parents could not work. Her local cultural center provided traditional dancing classes and the local church offered school tutoring for her and her siblings (and the other children she took care of during the height of the pandemic). They also helped Yolanda find an internship over the summer.

Churches, synagogues, mosques, youth development organizations, cultural centers, after-school programs, and tenant and block associations are among the many community-based places and networks that can be important for supporting youths such as Yolanda and their families. These institutions and agencies are especially adept at providing social support, community building, and assistance with basic needs. A key area for mental health promotion, including addressing youth anxiety, lies in building effective community networks that bring together members of the community with the health, education, and social service professionals and organizations that serve children and families. For most communities, building effective networks means building the capacity to identify needs, assets, and potential resources. Strategies that can be particularly helpful in community settings include building capacity for mental health through partnerships across child-serving systems. In addition, offering training on mental health interventions across community networks is essential.

Summary

Social and system-based approaches are important for complementing mental health services and for addressing escalating anxiety and other mental health needs. We also need creative solutions for supporting the increased mental health services demands exacerbated during the pandemic. Although community-level interventions to combat structural racism and reduce population-level risk are sorely needed, many youths will also continue to require treatment services for anxiety. Schools are important centering environments for implementing tiered interventions. Nurturing responsive relationships with adult caregivers across community settings has been consistently identified for fostering resilience.32 Teachers, parents, and community leaders must be supported to provide a multi-tiered and public health approach to care. Substantial structural, community, school, family, and individual level resources can help mitigate the long-term impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on child and adolescent mental health, and on children’s psychosocial and educational outcomes.

Clinics care points

To address the impact of the pandemic on anxiety disorders for youth, it is important to implement a tiered clinical, educational, and public health approach, including the following.

- Clinical Services in Primary Care and Specialty Care

-

•Establishing methods of screening to identify children, youth, and families who may be experiencing anxiety, and identifying patient groups in need of services.

-

•Using integrated and collaborative care models in primary care that include case management, behavioral health, and psychiatry consultation as needed.

-

•Providing grief counseling for youth who have lost caregivers and other important adults including educators.

-

•Digital delivery of prevention and evidence-based treatments should be explored to help with broader reach and access to care.

-

•

- School-Based Care from Clinical, Nursing, and Educational Staff

-

•Collaborating with school-based mental health professionals who provide direct support to students who are potentially at risk for emotional issues can help to implement screening processes in health centers and for referring students as appropriate to psychological support services and/or basic needs.

-

•Working with school nurses, who often encounter and identify when students are experiencing situations that are triggers for stress and anxiety.

-

•Supporting teachers and school staff in their experiences of anxiety and stress.

-

•Promoting student success by developing and implementing Section 504 plans, the health portion of Special Education IEP, and the Individualized Healthcare Plan.

-

•Promoting and practicing emotional regulation skills in schools—including supporting and contributing to implementing evidence-based programs and curricula in schools, which include strategies such as mindfulness, yoga, the arts, meditation, deep breathing, relaxation, and exercising for students and staff. Mindfulness and other wellness apps may be useful for older students.

-

•Identifying how earlier school closure might still be contributing to increased anxiety and loneliness in young people and child stress, sadness, frustration, indiscipline, and hyperactivity as they continue to adapt to the school setting.33

-

•Implementing evidence-based interventions including school-based cognitive behavioral therapy that are effective in decreasing anxiety symptoms and in sustaining improvements post treatment.

-

•

- Community/Public Health Supports

-

•Engaging with community networks and social groups, churches, and other community resources as part of the continuum of care and for cultural responsiveness.

-

○Promoting opportunities for positive relationships and positive environment

-

○Helping meet families’ basic needs

-

○Fostering strong parent–child relationships

-

○Promoting parents’ and other caregivers’ self-care

-

○Tapping into cultural strengths, family experiences, and stories that promote families’ well-being

-

○

-

•Remembering that resources that help with basic needs and address social determinants of mental health are best cultivated through community networks and work across child and family serving systems.

-

•

Disclosure

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Funding

NIMH Grant U01 MH131827-01 awarded to authors Dr L.R. Fortuna and M.A. Porche.

References

- 1.Fortuna L.R., Tolou-Shams M., Robles-Ramamurthy B., et al. Inequity and the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color in the United States: the need for a trauma-informed social justice response. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12(5):443–445. doi: 10.1037/tra0000889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leeb R.T., Bitsko R.H., Radhakrishnan L., et al. Mental health-related emergency department visits among children aged <18 years during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, January 1-October 17, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(45):1675–1680. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6945a3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mercado M.C., Holland K., Leemis R.W., et al. Trends in emergency department visits for nonfatal self-inflicted injuries among youth aged 10 to 24 years in the United States, 2001-2015. JAMA. 2017;318(19):1931–1933. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharma M., Aggarwal S., Madaan P., et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on sleep in children and adolescents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med. 2021;84:259–267. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Racine N., McArthur B.A., Cooke J.E., et al. Global prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(11):1142–1150. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Terin H., Açıkel S.B., Yılmaz M.M., et al. The effects of anxiety about their parents getting COVID-19 infection on children's mental health. Eur J Pediatr. 2022;1-7 doi: 10.1007/s00431-022-04660-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hagan M.J., Roubinov D.R., Cordeiro A., et al. Young children's traumatic stress reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic: the long reach of mothers' adverse childhood experiences. J Affect Disord. 2022;318:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.08.061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Washburn M., Yu M., LaBrenz C., et al. The impacts of COVID-19 on LGBTQ+ foster youth alumni. Child Abuse Negl. 2022;133:105866. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2022.105866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gee G.C., Morey B.N., Bacong A.M., et al. Considerations of racism and data equity among asian Americans, native hawaiians, and pacific islanders in the context of COVID-19. Curr Epidemiol Rep. 2022;9(2):77–86. doi: 10.1007/s40471-022-00283-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrasik M.P., Maunakea A.K., Oseso L., et al. Awakening: the unveiling of historically unaddressed social inequities during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2022;36(2):295–308. doi: 10.1016/j.idc.2022.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hillis S.D., Unwin H.J.T., Chen Y., et al. Global minimum estimates of children affected by COVID-19-associated orphanhood and deaths of caregivers: a modelling study. Lancet. 2021;398(10298):391–402. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01253-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.California department of public health (2022). COVID-19 age, race and ethnicity data. https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/Pages/COVID-19/Age-Race-Ethnicity.aspx Available at:

- 13.Önder A., Sürer Adanır A., İşleyen Z., et al. Evaluation of long-term psychopathology and sleep quality in children and adolescents who presented to a university pandemic clinic with possible COVID-19 symptoms. Psychol Trauma. 2022 doi: 10.1037/tra0001387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spencer A.E., Oblath R., Dayal R., et al. Changes in psychosocial functioning among urban, school-age children during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2021;15(1):73. doi: 10.1186/s13034-021-00419-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Englander E. Bullying, cyberbullying, anxiety, and depression in a sample of youth during the Coronavirus pandemic. Pediatr Rep. 2021;13(3):546–551. doi: 10.3390/pediatric13030064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gibbs K.D., Jones J.T., LaMark W., et al. Public Health Nurs; 2022. Coping during the COVID-19 pandemic among young adults experiencing homelessness and unstable housing: a qualitative study. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.García-Lara R.A., Gómez-Urquiza J.L., Membrive-Jiménez M.J., et al. Anxiety, distress and stress among patients with diabetes during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pers Med. 2022;12(9) doi: 10.3390/jpm12091412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Delpino F.M., da Silva C.N., Jerônimo J.S., et al. Prevalence of anxiety during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis of over 2 million people. J Affect Disord. 2022;318:272–282. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2022.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murphy A., Pinkerton L.M., Bruckner E., et al. The impact of the novel Coronavirus disease 2019 on therapy service delivery for children with disabilities. J Pediatr. 2021;231:168–177.e161. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2020.12.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hart N., Fawkner S., Niven A., et al. Scoping review of yoga in schools: mental health and cognitive outcomes in both neurotypical and neurodiverse youth populations. Children. 2022;9(6) doi: 10.3390/children9060849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chen Y., Allen A.P., Fallon M., et al. The challenges of mental health of staff working with people with intellectual disabilities during COVID-19--A systematic review. J Intellect Disabil. 2022 doi: 10.1177/17446295221136231. 17446295221136231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Findling R.L., Stepanova E. The workforce shortage of child and adolescent psychiatrists: is it time for a different approach? J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2018;57(5):300–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee J.B., DeFrank G., Gaipa J., et al. Applying a global perspective to school-based health centers in New York City. Ann Glob Health. 2017;83(5–6):803–807. doi: 10.1016/j.aogh.2017.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nelson E.L., Zhang E., Punt S.E., et al. Leveraging community health workers in extending pediatric telebehavioral health care in rural communities: evaluation design and methods. Fam Syst Health. 2022;40(4):566–571. doi: 10.1037/fsh0000742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Makwana N. Disaster and its impact on mental health: a narrative review. J Family Med Prim Care. 2019;8(10):3090–3095. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_893_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Psihogios A.M., Stiles-Shields C., Neary M. The Needle in the haystack: identifying credible mobile health apps for pediatric populations during a pandemic and beyond. J Pediatr Psychol. 2020;45(10):1106–1113. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsaa094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sorkin D.H., Janio E.A., Eikey E.V., et al. Rise in use of digital mental health tools and technologies in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic: survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2021;23(4):e26994. doi: 10.2196/26994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Conference of State Legislatures, Elementary and secondary school emergency relief fund tracker, Available at: https://www.ncsl.org/ncsl-in-dc/standing-committees/education/cares-act-elementary-and-secondary-school-emergency-relief-fund-tracker.aspx#relief-fund-table, 2022. Accessed November 19, 2022.

- 29.Kush J.M., Badillo-Goicoechea E., Musci R.J., et al. Teacher mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: informing policies to support teacher well-being and effective teaching practices. arXiv. 2021 https://arxiv.org/pdf/2109.01547.pdf Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gillani A., Dierst-Davies R., Lee S., et al. Teachers' dissatisfaction during the COVID-19 pandemic: factors contributing to a desire to leave the profession. Front Psychol. 2022;13:940718. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2022.940718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fainardi V., Meoli A., Chiopris G., et al. Long COVID in children and adolescents. Life. 2022;12(2) doi: 10.3390/life12020285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Komro K.A., Flay B.R., Biglan A. Creating nurturing environments: a science-based framework for promoting child health and development within high-poverty neighborhoods. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2011;14(2):111–134. doi: 10.1007/s10567-011-0095-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McMaughan D.J., Rhoads K.E., Davis C., et al. COVID-19 related experiences among college students with and without disabilities: psychosocial impacts, supports, and virtual learning environments. Front Public Health. 2021;9:782793. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.782793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]