Abstract

目的

观察慢性肾脏病(chronic kidney disease,CKD)1~2期的初诊IgA肾病患者肠道微生物群的特征,进一步探索IgA肾病疾病进展因素与肠道微生物之间的关系。

方法

收集19例CKD 1~2期的初诊IgA肾病患者和15例年龄、性别相匹配的健康对照组的新鲜粪便样本,提取粪便细菌DNA,针对V3-V4区域进行16S核糖体RNA(16S ribosomal RNA,16S rRNA)高通量测序分析肠道菌群的组成,应用Illumina Miseq平台对粪便菌群测序结果进行分析。收集初诊IgA肾病患者的疾病进展因素,研究肠道菌群与IgA肾病疾病进展因素之间的相关性。

结果

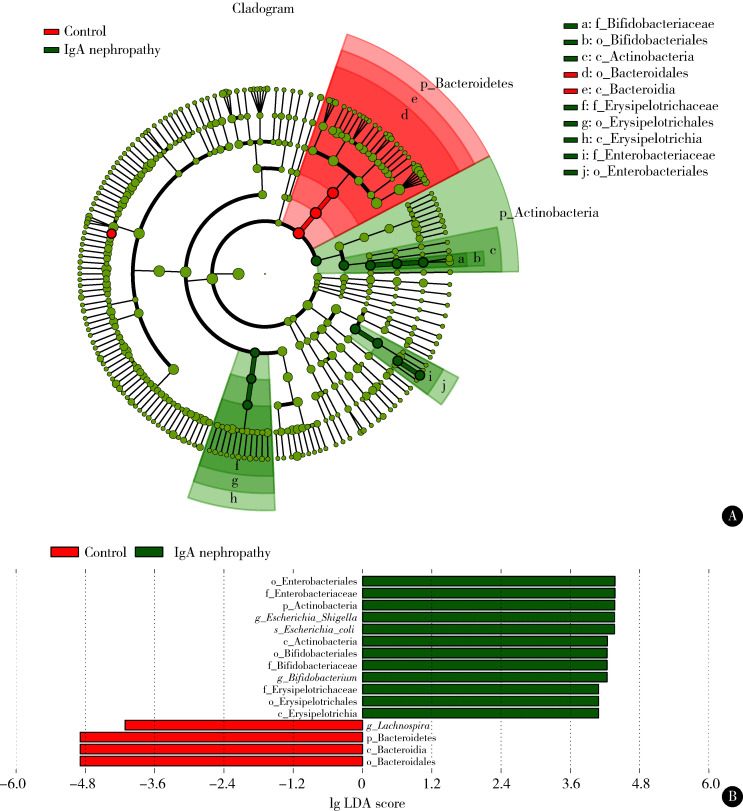

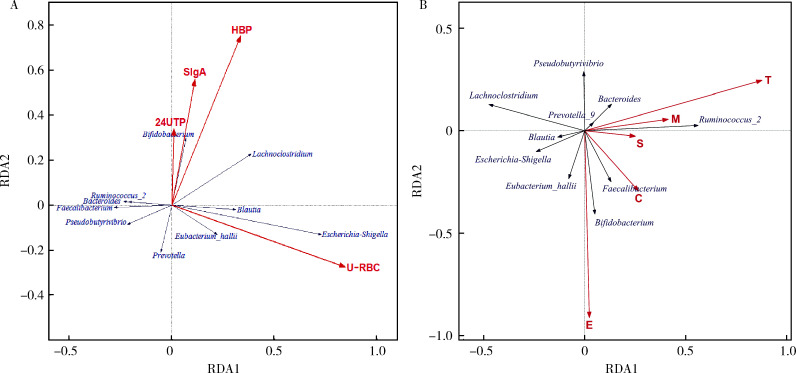

(1) 与健康对照组相比,在门水平上,拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes)的丰度显著降低(P=0.046),放线菌门(Actinobacteria)的丰度显著升高(P=0.001)。在属水平上,埃希菌-志贺菌属(Escherichia-Shigella)、双歧杆菌属(Bifidobacterium)、Dorea等菌属的丰度显著升高(P < 0.05),毛螺菌属(Lachnospira)、粪球菌属_2(Coprococcus_2)、萨特氏菌属(Sutterella)等菌属的丰度显著降低(P < 0.05)。(2)初诊IgA肾病患者与健康对照组之间肠道菌群的丰度比较差异无统计学意义(P>0.05),但两组肠道菌群的组成存在差异。LEfSe分析结果显示,初诊IgA肾病患者和健康对照组比较有16个差异菌,其中,初诊IgA肾病患者肠杆菌目(Enterobacteriales)、放线菌门、埃希菌-志贺菌属等的丰度升高,健康对照组拟杆菌门、毛螺菌属的丰度升高。(3)冗余分析(redundancy analysis,RDA)的结果显示,初诊IgA肾病患者粪便中双歧杆菌属与血清IgA水平、24 h尿蛋白定量和合并高血压呈正相关,Lachnoclostridium菌属与合并高血压呈正相关,埃希菌-志贺菌属与尿红细胞数量呈正相关,双歧杆菌属与毛细血管内增殖呈正相关,粪杆菌属与细胞/纤维细胞性新月体呈正相关,瘤胃球菌属_2(Ruminococcus_2)与系膜细胞增殖、肾小球节段硬化、肾小管萎缩/间质纤维化呈正相关。

结论

初诊CKD 1~2期IgA肾病患者的肠道菌群与健康对照相比存在差异,肠道的某些菌属与IgA肾病疾病进展因素呈相关性,需要进一步的研究来了解这些菌属在IgA肾病中的潜在作用。

Keywords: 肾小球肾炎, 免疫球蛋白A; 胃肠道微生物组; 疾病特征; 16S核糖体RNA

Abstract

Objective

To investigate the gut microbiota in newly diagnosed IgA nephropathy patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) stages 1-2 and the association between the gut microbiota and the clinical risk factors of IgA nephropathy.

Methods

Fresh fecal samples were collected from nineteen newly diagnosed IgA nephropathy patients with CKD stages 1-2 and fifteen age- and sex-matched healthy controls. Fecal bacterial DNA was extracted and microbiota composition were characterized using 16S ribosomal RNA (16S rRNA) high-throughput sequencing for the V3-V4 region. The Illumina Miseq platform was used to analyze the results of 16S rRNA high-throughput sequencing of fecal flora. At the same time, the clinical risk factors of IgA nephropathy patients were collected to investigate the association between the gut microbiota and the clinical risk factors.

Results

(1) At the phylum level, the abundance of Bacteroidetes was significantly reduced (P=0.046), and the abundance of Actinobacteria was significantly increased (P=0.001). At the genus level, the abundance of Escherichia-Shigella, Bifidobacte-rium, Dorea and others were significantly increased (P < 0.05). The abundance of Lachnospira, Coprococcus_2 and Sutterella was significantly reduced (P < 0.05). (2) There was no significant difference in the abundance of gut microbiota between the newly diagnosed IgA nephropathy patients and the healthy control group (P>0.05), but there were differences in the structure of the gut microbiota between the two groups. The results of LEfSe analysis showed that there were 16 differential bacteria in the newly diagnosed IgA nephropathy patients and healthy controls. Among them, the abundance of the newly diagnosed IgA nephropathy patients was increased in Enterobacteriales, Actinobacteria, Escherichia-Shigella, etc. The healthy control group was increased in Bacteroidetes and Lachnospira. (3) The result of redundancy analysis (RDA) showed that Bifidobacterium was positively correlated with serum IgA levels, 24-hour urinary protein levels and the presence of hypertension. Lachnoclostridium was positively correlated with the presence of hypertension. Escherichia-Shigella was positively correlated with urine red blood cells account. Bifidobacterium was positively correlated with the proliferation of capillaries. Faecalibacterium was positively correlated with cell/fibrocytic crescents. Ruminococcus_2 was positively correlated with mesangial cell proliferation, glomerular segmental sclerosis and renal tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis.

Conclusion

The gut microbiota in the newly diagnosed IgA nephropathy patients with CKD stages 1-2 is different from that of the healthy controls. Most importantly, some gut bacteria are related to the clinical risk factors of IgA nephropathy. Further research is needed to understand the potential role of these bacteria in IgA nephropathy.

Keywords: Glomerulonephritis, immunoglobulin A; Gastrointestinal microbiome; Disease attributes; RNA, ribosomal, 16S

IgA肾病是最常见的原发性肾小球疾病,其病理特征包括肾小球系膜区以IgA为主的沉积、肾小球系膜细胞(glomerular mesangial cells, GMC)增生和系膜基质增加。约40%的IgA肾病患者在确诊后20年内进展至终末期肾病(end stage renal disease, ESRD)[1]。国内外学者普遍认为IgA肾病是“免疫复合物引起的肾小球疾病”[2],目前,IgA肾病的病因和发病机制尚不明确。

近些年越来越多的证据表明,肠-肾轴和肠道菌群失调在IgA肾病中起着关键的作用。Hu等[3]的研究发现, 与健康对照者(18例)相比,IgA肾病患者(17例)梭杆菌门(Fusobacteria)丰度增加,互养菌门(Synergistetes)丰度降低。埃希菌-志贺菌属(Escherichia-Shigella)、依格斯氏菌属(Eggerthella)和Hungatella三个菌属显著增加并具有致病性。De Angelis等[4]对进展期IgA肾病患者(16例)、非进展期IgA肾病患者(16例)和健康对照者(16例)的肠道微生物群进行分析,结果显示IgA肾病患者的粪便微生物群发生了改变。根据Chao1和Shannon多样性指数分析,进展期IgA肾病患者的微生物多样性最低。应当指出的是,上述研究纳入的IgA肾病患者存在肾功能不全,因此IgA肾病患者粪便微生物群的改变可能是由于肾功能不全引起的,而不是IgA肾病本身[5],因此,有必要进一步研究IgA肾病患者中肠道微生物的特征。此外,目前缺乏探索肠道微生物群与IgA肾病进展相关因素关系的研究。

本研究探讨慢性肾脏病(chronic kidney disease,CKD)1~2期的初诊IgA肾病患者肠道微生物群特征,并进一步探索IgA肾病进展相关因素与肠道微生物之间的关系,以期有助于发现新的影响IgA肾病预后的因素,探索提示IgA肾病预后的新方法。

1. 资料与方法

1.1. 研究对象

本研究纳入2016年3月20日至7月15日于北京大学第三医院肾内科住院期间经肾脏活检诊断为IgA肾病的新患者。纳入标准:经肾脏活检确诊为IgA肾病的新患者。排除标准;(1)估算的肾小球滤过率(estimated glomerular filtration rate,eGFR) < 60 mL/(min·1.73 m2);(2)急性肾损伤;(3)恶性高血压(舒张压≥ 130 mmHg);(4)3个月内应用过抗生素、益生菌或益生元;(5)糖尿病、神经系统或胃肠道疾病;(6)6个月内患急性心肌梗死或急性脑梗塞;(7)严重肝脏疾病、恶性肿瘤、怀孕或患有其他已知的自身免疫性疾病;(8)不同意参加本研究。

同时纳入来自体检中心的健康受试者,纳入标准:(1)18~65岁;(2)无高血压、糖尿病、肾脏病病史,3个月内血常规、尿常规、肝功能、肾功能、血糖、血脂检测均正常;(3)至少1个月内饮食和药物方面没有显著变化;(4)非妊娠和哺乳期妇女;(5)签署知情同意书。

本研究经北京大学第三医院医学科学研究伦理委员会批准(IRB00006761-2016023),所有受试者均签署知情同意书。

1.2. 研究方法

1.2.1. 资料收集

收集初诊IgA肾病患者和健康对照者的基本临床资料,包括年龄、性别、血肌酐、eGFR、肾脏活检组织病理结果。收集初诊IgA肾病患者治疗前的疾病进展因素指标,包括血压、血清IgA水平、24 h尿蛋白定量和尿红细胞数量。

1.2.2. 粪便样品收集与DNA提取

收集初诊IgA肾病患者和健康受试者的新鲜粪便样本,无菌条件下对粪便中段取样并置于无菌粪便收集管中,于-80 ℃低温冰箱冻存。使用PowerSoil DNA Isolation Kit (MoBio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA)试剂盒,按照说明书提取粪便DNA,用1%(质量分数)琼脂糖凝胶电泳和分光光度法检测DNA的纯度和浓度。

1.2.3. PCR扩增及高通量测序

细菌16S核糖体RNA(16S ribosomal RNA,16S rRNA)基因V3-V4可变区片段扩增采用338F(5′-ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG-3′)和806R(5′-GGACTACHVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′)引物,由北京奥维森基因科技有限公司合成[6]。PCR反应体系(总体系为25 μL):12.5 μL KAPA 2G Robust热启动预混液、1 μL上游引物(5 μmol/L)、1 μL下游引物(5 μmol/L)、5 μL DNA(加入的DNA总量为30 ng),最后加入5.5 μL双蒸水补足至25 μL。PCR反应程序:95 ℃预变性5 min;95 ℃变性45 s、55 ℃退火50 s、72 ℃延伸45 s,28个循环;72 ℃延伸10 min。PCR产物用于构建微生物多样性测序文库,在北京奥维森基因科技有限公司使用Illumina Miseq PE300高通量测序平台进行双端测序。

1.2.4. 数据分析处理

使用Pear(v0.9.6)软件对原始数据进行过滤、拼接,拼接时最小交叠设置为10 bp,错配率为0.1。进一步利用QIIME1(v1.8.0)软件根据Barcode序列拆分样本,并去除打分值低于20、含有模糊碱基或引物错配序列。拼接后使用Vsearch(v2.7.1)软件去除长度小于230 bp的序列,并根据Gold Database数据库用UCHIME方法比对去除嵌合体序列。使用Vsearch(v2.7.1)UPARSE算法对优质序列进行OTU(operational taxonomic units)聚类,相似性阈值为97%[7]。基于Silva128数据库使用RDP Classifier算法进行比对,设置70%的置信度阈值,得到每个OTU对应的物种分类信息[8]。

1.3. 统计学分析

使用R 3.1.0和SPSS 22.0统计软件进行分析,计数资料以百分数(%)表示,对计量资料先进行正态性和方差齐性检验,符合正态分布的计量资料采用x±s表示,不符合正态分布的计量资料采用M(min, max)表示。两组间比较采用Mann-Whitney U检验,两组肠道菌群OTU差异性比较使用Kruskal-Wallis检验。应用QIIME1(v1.8.0)软件进行α多样性分析,包括Shannon和Chao1指数;应用R 3.1.0软件进行β多样性分析,包括主成分分析(principal component analysis,PCA)和非度量多维尺度分析(nonmetric muhidimensional scaling,NMDS)。两组间肠道菌群物种差异性使用Phython(v2.7)软件进行LEfSe分析[线性判别分析(linear discriminant analysis,LDA)值>4认为差异有统计学意义][9]。IgA肾病疾病进展因素与肠道菌群之间的关系应用冗余分析(redundancy analysis,RDA)[10-11]。P < 0.05为差异有统计学意义。

2. 结果

2.1. 初诊IgA肾病患者和健康人群肠道菌群物种组成

本研究纳入19例初诊IgA肾病患者和15例年龄和性别匹配的健康对照者进行肠道菌群分析,IgA肾病患者和健康对照者的基本特征见表 1。对初诊IgA肾病患者和健康对照者的肠道菌群16S rRNA的V3-V4可变区进行高通量测序,稀释性曲线显示,随着测序量增加,样本的稀释性曲线逐渐趋于平缓(图 1),表明样本的测序深度和覆盖范围足够,适合下一步的分析和研究。

表 1.

IgA肾病和健康对照的基本特征

Basic characteristics of IgA nephropathy patients and health controls

| Items | IgA nephropathy (n=19) | Health controls (n=15) | P |

| * According to IgA nephropathy Oxford classification. CKD-EPI, The Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate. | |||

| Age/years, x±s | 33.53±3.96 | 34.95±8.58 | 0.529 |

| Male | 53% | 47% | 0.790 |

| Serum creatinine/(μmol/L), x±s | 84.9±19.3 | 64.4±6.7 | < 0.001 |

| CKD-EPI eGFR/[mL/(min·1.73 m2)], x±s | 90.7±17.7 | 126.0±21.0 | < 0.001 |

| Pathological features of IgA nephropathy renal biopsy* | |||

| Mesangial hypercellularity (M) | M0=0%, M1=94.74%, M2=5.26%, M3=0% | ||

| Endocapillary proliferation (E) | E0=26.32%, E1=73.68% | ||

| Segmental sclerosis (S) | S0=68.42%, S1=31.58% | ||

| Tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis (T) | T0=73.68%, T1=26.32%, T2=0% | ||

| Cellular/fibrocytic crescent (C) | C0=84.21%, C1=15.79%, C2=0% | ||

图 1.

样本稀释性曲线

Sample rarefaction curves

Alphabetic abbreviations in the figure are the patients' initials. OUT, operational taxonomic units.

对肠道菌群物种的组成进行分析,在门水平上共鉴定出11个门,初诊IgA患者和健康对照组均以厚壁菌门(Firmicutes)、拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes)、变形菌门(Proteobacteria)和放线菌门(Actinobacteria)丰度较高。初诊IgA肾病患者中,拟杆菌门的丰度显著低于健康对照组(P=0.046),放线菌门的丰度显著高于健康对照组(P=0.001,图 2,表 2)。

图 2.

IgA肾病患者和健康对照者肠道菌群门水平的对比

Comparison of gut microflora at phylum level in IgA nephropathy patients and health controls

表 2.

IgA肾病患者和健康对照者肠道菌群的相对丰度变化

Change in relative abundance of gut microflora in IgA nephropathy patients and health controls

| Items | IgA nephropathy (n=19), M (min, max) | Controls (n=15), M (min, max) | P |

| Phylum | |||

| Bacteroidetes | 3.13×10-1 (3.86×10-2, 7.65×10-1) | 4.13×10-1 (8.29×10-2, 8.61×10-1) | 0.046 |

| Actinobacteria | 2.47×10-2 (6.84×10-4, 1.91×10-1) | 2.59×10-3 (2.63×10-4, 7.52×10-2) | 0.001 |

| Lentisphaerae | 0 (0, 2.93×10-5) | 0 (0, 6.81×10-3) | 0.011 |

| Saccharibacteria | 5.07×10-5 (0, 6.40×10-4) | 0 (0, 4.25×10-5) | < 0.001 |

| Genus | |||

| Escherichia-Shigella | 2.88×10-3 (7.79×10-5, 3.88×10-1) | 3.79×10-4 (0, 6.38×10-2) | 0.025 |

| Bifidobacterium | 1.17×10-2 (2.409×10-5, 1.87×10-1) | 1.15×10-3 (5.42×10-5, 6.84×10-2) | 0.036 |

| Lachnospira | 1.43×10-3 (0, 1.82×10-2) | 1.73×10-2 (0, 1.25×10-1) | 0.002 |

| Dorea | 8.84×10-3 (7.77×10-4, 1.03×10-1) | 4.67×10-3 (1.29×10-3, 1.07×10-2) | 0.025 |

| Erysipelotrichaceae_UCG-003 | 7.42×10-3 (0, 1.65×10-1) | 1.75×10-3 (1.78×10-4, 3.03×10-2) | 0.013 |

| Coprococcus_2 | 0 (0, 8.76×10-3) | 3.97×10-3 (0, 4.59×10-2) | 0.028 |

| Sutterella | 0 (0, 1.87×10-3) | 3.73×10-3 (0, 4.08×10-2) | < 0.001 |

| Tyzzerella_3 | 0 (0, 2.52×10-2) | 2.90×10-3 (0, 1.61×10-2) | 0.012 |

| Thalassospira | 0 (0, 1.73×10-3) | 0 (0, 5.52×10-2) | 0.015 |

| Lachnospiraceae_UCG-004 | 2.78×10-4 (0, 5.13×10-3) | 2.50×10-3 (2.93×10-4, 1.27×10-2) | 0.001 |

| Eubacterium_ventriosum_group | 3.04×10-4 (0, 1.02×10-2) | 1.31×10-3 (2.13×10-5, 1.27×10-2) | 0.042 |

| Lachnospiraceae_ND3007_group | 1.37×10-4 (0, 1.95×10-3) | 1.68×10-3 (2.44×10-5, 1.08×10-2) | 0.002 |

| Eggerthella | 1.11×10-3 (0, 1.23×10-2) | 0 (0, 6.58×10-5) | < 0.001 |

| Ruminiclostridium_5 | 8.97×10-4 (7.78×10-5, 7.58×10-3) | 4.14×10-4 (0, 1.34×10-3) | 0.030 |

| Lachnospiraceae_UCG-010 | 5.06×10-5 (0, 3.48×10-3) | 5.72×10-4 (0, 2.68×10-3) | 0.049 |

| Butyricimonas | 2.60×10-5 (0, 1.86×10-3) | 3.73×10-4 (0, 8.27×10-3) | 0.013 |

| Flavonifractor | 2.63×10-4 (0, 5.19×10-3) | 2.96×10-5 (0, 6.30×10-4) | 0.035 |

| Desulfovibrio | 0 (0, 1.82×10-3) | 0 (0, 1.25×10-2) | 0.045 |

| Ruminococcaceae_UCG-003 | 2.60×10-4 (0, 7.00×10-4) | 4.44×10-4 (4.25×10-5, 3.12×10-3) | 0.006 |

| Terrisporobacter | 2.53×10-5 (0, 8.71×10-3) | 0 (0, 6.58×10-4) | 0.003 |

| Granulicatella | 0.30×10-5 (0, 6.34×10-3) | 0 (0, 5.72×10-5) | 0.003 |

| Erysipelatoclostridium | 4.05×10-5 (0, 3.34×10-3) | 0 (0, 5.48×10-5) | 0.009 |

| Ruminiclostridium_9 | 2.16×10-5 (0, 1.19×10-3) | 2.36×10-4 (0, 1.14×10-3) | 0.015 |

| Victivallis | 0 (0, 2.93×10-5) | 0 (0, 6.81×10-3) | 0.011 |

| Cercis_gigantea | 2.53×10-5 (0, 4.07×10-3) | 0 (0, 3.33×10-5) | 0.015 |

| Ezakiella | 0 (0, 3.88×10-3) | 0 (0, 2.74×10-5) | 0.021 |

| Family_XIII_UCG-001 | 0 (0, 6.07×10-4) | 6.91×10-5 (0, 3.52×10-4) | 0.042 |

| Rothia | 0 (0, 2.47×10-3) | 0 (0, 8.91×10-5) | 0.030 |

| Gemella | 3.00×10-5 (0, 1.45×10-3) | 0 (0, 8.26×10-5) | 0.001 |

| Solobacterium | 2.16×10-5 (0, 7.25×10-4) | 0 (0, 3.33×10-5) | 0.045 |

| Acinetobacter | 0 (0, 2.13×10-4) | 0 (0, 2.74×10-5) | 0.028 |

| Corynebacterium | 0 (0, 2.13×10-4) | 0 (0, 0) | 0.005 |

| Olsenella | 2.16×10-5 (0, 8.09×10-5) | 0 (0, 3.33×10-5) | 0.007 |

| Atopobium | 0 (0, 1.20×10-4) | 0 (0, 0) | 0.035 |

| Leptotrichia | 0 (0, 1.20×10-4) | 0 (0, 0) | 0.010 |

| Methylobacterium | 0 (0, 8.69×10-5) | 0 (0, 0) | 0.019 |

在属水平上共鉴定出148个属,初诊IgA肾病患者和健康对照组均以拟杆菌属(Bacteroides)、普氏菌属_9(Prevotella_9)、布劳特氏菌属(Blautia)、粪杆菌属(Faecalibacterium)、假丁酸弧菌属(Pseudobutyrivibrio)的丰度较高。初诊IgA肾病患者中埃希菌-志贺菌属(Escherichia-Shigella)、双歧杆菌属(Bifidobacterium)、Dorea菌属的丰度显著高于健康对照组(P < 0.05),毛螺菌属(Lachnospira)、粪球菌属_2(Coprococcus_2)、萨特氏菌属(Sutterella)等菌属的丰度显著低于健康对照组(P < 0.05,图 3,表 2)。

图 3.

IgA肾病患者和健康对照者肠道菌群属水平的对比

Comparison of gut microflora at genus level in IgA nephropathy patients and health controls

2.2. 初诊IgA肾病患者和健康人群肠道菌群多样性及物种差异性分析

通过对肠道菌群α多样性和β多样性进行分析,对比初诊IgA肾病患者和健康对照者之间肠道菌群的丰度和组成。肠道菌群α多样性应用Shannon指数和Chaol指数进行分析,结果显示两组肠道菌群丰度差异无统计学意义(P>0.05,表 3)。肠道菌群β多样性应用PCA和NMDS进行分析,发现两组肠道菌群有离散趋势,说明两组肠道菌群组成存在差异(图 4)。

表 3.

IgA肾病和健康对照肠道菌群α多样性分析

The α diversity analysis of gut microflora in IgA nephropathy patients and health controls

| Items | IgA nephropathy (n=19), x±s | Controls (n=15), x±s | P |

| Shannon index | 4.31±0.47 | 4.05±0.99 | 0.316 |

| Chao1 index | 158±32 | 157±35 | 0.942 |

图 4.

IgA肾病和健康对照间β多样性分析

The β diversity analysis in IgA nephropathy patients and health controls

A, Principal component analysis in IgA nephropathy patients and health controls; B, Nonmetric muhidimensional scaling in IgA nephropathy patients and health controls. PCA, principal component analysis; NMDS, nonmetric muhidimensional scaling.

初诊IgA肾病组和健康对照组间肠道菌群的物种差异性采用LEfSe分析(图 5),两组比较有16个差异菌,其中初诊IgA肾病患者中肠杆菌目(Enterobacteriales)、放线菌门、埃希菌-志贺菌属等的丰度升高,健康对照组的拟杆菌门、毛螺菌属丰度升高。

图 5.

IgA肾病和健康对照间LEfSe分析

LEfSe in IgA nephropathy patients and health controls

A, branch evolution diagram of LEfSe in IgA nephropathy patients and health controls; B, histogram of LEfSe in IgA nephropathy patients and health controls. LDA, linear discriminant analysis.

2.3. 肠道菌群与IgA肾病疾病进展因素的相关性

初诊IgA肾病患者的疾病进展因素见表 4。本研究RDA结果显示,初诊IgA肾病患者中双歧杆菌属与血清IgA水平、24 h尿蛋白定量和合并高血压呈正相关,Lachnoclostridium菌属与合并高血压呈正相关,埃希菌-志贺菌属与尿红细胞数量呈正相关(图 6A)。初诊IgA肾病患者双歧杆菌属与毛细血管内增殖呈正相关,粪杆菌属与细胞/纤维细胞性新月体呈正相关,瘤胃球菌属_2(Ruminococcus_2)与系膜细胞增殖、肾小球节段硬化、肾小管萎缩/间质纤维化呈正相关(图 6B)。

表 4.

IgA肾病患者的疾病进展因素

The clinical risk factors of IgA nephropathy patients

| Items | IgA nephropathy (n=19) |

| Data are presented as x±s or M (min, max). | |

| Hypertention (yes/no) | 7/12 |

| Systolic pressure/mmHg | 133 (121, 189) |

| Diastolic pressure/mmHg | 88.32±11.56 |

| Serum IgA levels/(mg/dL) | 4.15 (1.78, 47.60) |

| Urine red blood cells account (/μL) | 175 (12, 1 886) |

| 24-hour urinary protein levels/g | 1.86 (0.26, 9.37) |

图 6.

肠道菌群与IgA肾病临床进展因素及肾脏病理相关性分析

Correlation analysis of gut microflora and clinical risk factors or renal biopsy in IgA nephropathy patients

A, correlation analysis of gut microflora and clinical risk factors in IgA nephropathy patients; B, correlation analysis of gut microflora and renal biopsy in IgA nephropathy patients. RDA, also known as multiple direct gradient analysis, is based on linear model analysis, and combines correspondence analysis with multiple regression analysis. Each step of calculation is regression with disease progression-related factors and renal pathological staging, which can be used to detect the relationship between the progression-related factors, renal biopsy and gut microflora. The red rays represent influencing factors, and the length of the rays represents the degree of influence of the influencing factors on the composition of the flora. The direction of the blue vector indicates the direction in which the abundance of the species increases. The angle between the two represents the correlation between influencing factors and species (acute angle represents positive correlation, obtuse angle represents negative correlation). HBP, high blood pressure; SIgA, serum IgA; U-RBC, urine red blood cells account; 24UTP, 24-hour urinary protein. RDA, redundancy analysis. M, mesangial hypercellularity; E, endo-capillary proliferation; S, segmental sclerosis; T, tubular atrophy/interstitial fibrosis; C, cellular/fibrocytic crescent.

3. 讨论

IgA肾病是最常见的原发性肾小球疾病,临床表现和病理特征多样,目前IgA肾病的病因和发病机制尚不明确。国内外学者普遍认为IgA肾病是“免疫复合物引起的肾小球疾病”[2]。2011年,Suzuki等[12]基于IgA肾病的发病机制提出了“多重打击学说”,即IgA1发生糖基化异常,产生半乳糖缺失IgA1(galactose deficiency-IgA1, Gd-IgA1),血清中抗Gd-IgA1的IgG或IgA1抗体形成,Gd-IgA1与对应抗体结合形成循环免疫复合物(circulating immune complex, CIC),这些免疫复合物在肾小球系膜区沉积,从而引起GMC免疫炎症反应。近年来越来越多的证据表明,肠-肾轴和肠道菌群失调在IgA肾病中起着关键作用。人体IgA由黏膜分泌,通过促进细菌共生对肠道菌群的组成产生重要影响[13]。黏膜异常可能参与Gd-IgA1、大分子免疫复合物和系膜沉积物的产生[14]。IgA肾病患者肠道内γδT细胞亚群较健康人群明显减少[15],而与维持肠道菌群免疫耐受相关的血清B淋巴细胞激活因子(B-cell activating factor,BAFF)水平增高[16]。McCarthy等[16]在BAFF过量表达的转基因小鼠中发现,小鼠系膜区有IgA沉积,并且循环中异常糖基化聚合IgA水平较高,与IgA肾病相关。一项全基因相关研究显示,IgA肾病相关位点与免疫介导的炎症性肠病、肠道屏障的维护以及对肠道病原体的应答相关[17]。Grosserichter-Wagener等[18]证实肠道微生态可以影响抗体反应活性、Th细胞亚群和IgA反应活性。现有证据表明,肠黏膜免疫反应紊乱可导致IgA肾病的发生。肠道菌群与肠黏膜上皮细胞接触,通过改变肠道通透性和与黏膜细胞表达的Toll样受体相互作用,调节肠道免疫系统。肠道菌群与人体固有免疫系统和适应性免疫系统相互作用,产生影响[19-20]。

本研究比较了CKD 1~2期的初诊IgA肾病患者和健康对照组的肠道菌群特征,发现与健康对照组相比,在门水平上初诊IgA肾病患者粪便中拟杆菌门的丰度显著降低,与其他研究结果一致[3-4],放线菌门的丰度显著高于健康对照组。在属水平上,我们发现初诊IgA肾病患者粪便中埃希菌-志贺菌属、双歧杆菌属、Dorea等菌属的丰度显著高于健康对照组,毛螺菌属、粪球菌属_2、萨特氏菌属等菌属的丰度显著低于健康对照组。RDA结果显示,初诊IgA肾病患者中双歧杆菌属与血清IgA水平、24 h尿蛋白定量和合并高血压呈正相关,Lachnoclostridium菌属与合并高血压呈正相关,埃希菌-志贺菌属与尿红细胞数量呈正相关,双歧杆菌属与毛细血管内增殖呈正相关,粪杆菌属与细胞/纤维细胞性新月体呈正相关,瘤胃球菌属_2与系膜细胞增殖、肾小球节段硬化、肾小管萎缩/间质纤维化呈正相关。

健康人群肠道内定居着种类繁多的微生物群,拟杆菌和厚壁菌占主导地位[21]。拟杆菌在维持肠道内环境稳态、免疫调节、代谢综合征、脑-肠轴中具有重要作用[22]。一些炎症或代谢性疾病(如炎症性肠病[23]和肥胖[24]等)与拟杆菌门的丰度下降相关,本研究证实了这种异常的肠道菌群分布存在于IgA肾病患者中。

既往研究显示IgA肾病患者中埃希菌-志贺菌属与eGFR呈正相关,可能是肾脏疾病的生物标志物[3],本研究结果显示初诊IgA肾病患者粪便中埃希菌-志贺菌属的丰度升高,也支持这一观点。双歧杆菌属属于放线菌门,我们的结果发现在初诊IgA肾病患者中,双歧杆菌属的丰度较高,且血清IgA水平、24 h尿蛋白和合并高血压与双歧杆菌属的丰度有关,但截至目前,高丰度的双歧杆菌对IgA肾病的致病作用尚无定论。有研究表明,黏膜免疫系统失调和对常见病原体或食物成分的免疫耐受缺陷,可能是触发IgA肾病的关键因素[25]。McCarthy等[16]的研究发现,过量表达血清BAFF的小鼠会发生共生菌相关的IgA相关肾病。共生菌群的存在是血清IgA水平升高的必要条件,并且在血液中发现了共生菌反应性的IgA抗体,小鼠肾脏系膜区有IgA沉积,并且循环中异常糖基化聚合IgA水平较高,与IgA肾病相关。双歧杆菌可以激活宿主的肠黏膜免疫系统,促进免疫球蛋白IgA的分泌[26]。我们推测,高丰度的双歧杆菌和对肠道正常菌群(如双歧杆菌)过度的肠道黏膜抗体反应可能在IgA肾病的发生发展中起重要作用。在IgA肾病患者中,双歧杆菌的高丰度以及是否在IgA肾病发展中起作用仍需进一步研究。本研究中,双歧杆菌属具有较高丰度,与既往研究不同。既往研究显示,IgA肾病患者粪便中双歧杆菌的丰度较健康对照组有所减少[4]。本研究中的IgA肾病患者的肾功能水平(通过eGFR评估)比既往研究要好。以往研究已证实,肾功能不全患者的肠道菌群结构失调,尤其是双歧杆菌的丰度降低[25]。因此,既往研究IgA肾病患者粪便中双歧杆菌丰度的降低可能是由于肾功能不全而非IgA肾病本身导致。由于非IgA肾病的种类繁多,目前每种肾病对于肠道菌群的影响也很难判断,在选择肾病时可能存在偏倚,因此本研究仅选取IgA肾病患者的粪便肠道菌群进行研究,今后我们会继续探索IgA肾病和不同种肾病的粪便肠道菌群比较。

本研究的主要局限性在于样本量有限,此外,观察性的横断面研究也无法明确IgA肾病疾病进展因素与肠道微生物之间的因果关系。

综上所述,本研究发现初诊IgA肾病患者和健康对照组的肠道菌群丰度和组成存在差异。与健康对照组相比,在门水平上初诊IgA肾病患者粪便中放线菌门门的丰度升高,拟杆菌门的丰度降低;在属水平上,初诊IgA肾病患者粪便中埃希菌-志贺菌属、双歧杆菌属、Dorea等菌属的丰度显著升高,毛螺菌属、粪球菌属_2、萨特氏菌属等菌属的丰度显著降低。RDA结果显示,初诊IgA肾病患者双歧杆菌属与血清IgA水平、24 h尿蛋白定量和合并高血压呈正相关,Lachnoclostridium菌属与合并高血压呈正相关,埃希菌-志贺菌属与尿红细胞数量呈正相关,双歧杆菌属与毛细血管内增殖呈正相关,粪杆菌属与细胞/纤维细胞性新月体呈正相关,瘤胃球菌属_2与系膜细胞增殖、肾小球节段硬化、肾小管萎缩/间质纤维化呈正相关。今后将进一步随访,探索IgA肾病疾病进展因素与肠道微生物之间的因果关系,并研究双歧杆菌在IgA肾病中的作用。

Funding Statement

中华医学会临床医学科研专项资金项目(14050460583)和中华国际医学交流基金会(Z-2017-24-2037)

Supported by the Clinical Medical Research Special Fund Project of Chinese Medical Association (14050460583) and the China International Medical Foundation (Z-2017-24-2037)

References

- 1.Schena FP, Nistor I. Epidemiology of IgA nephropathy: A global perspective. Semin Nephrol. 2018;38(5):435–442. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2018.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang M, Lv J, Zhang X, et al. Secondary IgA nephropathy shares the same immune features with primary IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int Rep. 2020;5(2):165–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ekir.2019.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu X, Du J, Xie Y, et al. Fecal microbiota characteristics of Chinese patients with primary IgA nephropathy: A cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21(1):97. doi: 10.1186/s12882-020-01741-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.De Angelis M, Montemurno E, Piccolo M, et al. Microbiota and metabolome associated with immunoglobulin A nephropathy (IgAN) PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99006. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hobby GP, Karaduta O, Dusio GF, et al. Chronic kidney disease and the gut microbiome. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2019;316(6):F1211–F1217. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00298.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Munyaka PM, Eissa N, Bernstein CN, et al. Antepartum antibio-tic treatment increases offspring susceptibility to experimental colitis: A role of the gut microbiota. PLoS One. 2015;10(11):e0142536. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0142536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Edgar RC. UPARSE: highly accurate OTU sequences from microbial amplicon reads. Nat Methods. 2013;10(10):996–998. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole JR, Wang Q, Cardenas E, et al. The ribosomal database project: Improved alignments and new tools for rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37(Suppl 1):D141–D145. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Segata N, Izard J, Waldron L, et al. Metagenomic biomarker discovery and explanation. Genome Biol. 2011;12(6):R60. doi: 10.1186/gb-2011-12-6-r60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitchell RJ, Hewison RL, Fielding DA, et al. Decline in atmospheric sulphur deposition and changes in climate are the major drivers of long-term change in grassland plant communities in Scotland. Environ Pollut. 2018;235:956–964. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.12.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li H, Li T, Beasley DE, et al. Diet diversity is associated with beta but not alpha diversity of pika gut microbiota. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1169. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki H, Kiryluk K, Novak J, et al. The pathophysiology of IgA nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;22(10):1795–1803. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011050464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakajima A, Vogelzang A, Maruya M, et al. IgA regulates the composition and metabolic function of gut microbiota by promoting symbiosis between bacteria. J Exp Med. 2018;215(8):2019–2034. doi: 10.1084/jem.20180427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Floege J, Feehally J. The mucosa-kidney axis in IgA nephropathy. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2016;12(3):147–156. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2015.208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olive C, Allen AC, Harper SJ, et al. Expression of the mucosal T cell receptor V region repertoire in patients with IgA nephropathy. Kidney Int. 1997;52(4):1047–1053. doi: 10.1038/ki.1997.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCarthy DD, Kujawa J, Wilson C, et al. Mice overexpressing BAFF develop a commensal flora-dependent, IgA-associated nephropathy. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(10):3991–4002. doi: 10.1172/JCI45563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiryluk K, Li Y, Scolari F, et al. Discovery of new risk loci for IgA nephropathy implicates genes involved in immunity against intestinal pathogens. Nat Genet. 2014;46(11):1187–1196. doi: 10.1038/ng.3118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grosserichter-Wagener C, Radjabzadeh D, van der Weide H, et al. Differences in systemic IgA reactivity and circulating Th subsets in healthy volunteers with specific microbiota enterotypes. Front Immunol. 2019;10:341. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Barko PC, McMichael MA, Swanson KS, et al. The gastrointestinal microbiome: A review. J Vet Intern Med. 2018;32(1):9–25. doi: 10.1111/jvim.14875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gomaa EZ. Human gut microbiota/microbiome in health and diseases: A review. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. 2020;113(12):2019–2040. doi: 10.1007/s10482-020-01474-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.包 文晗, 王 悦. 慢性肾脏病患者肠道菌群的变化及影响研究. 中国全科医学. 2018;21(24):2927–2931. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1007-9572.2018.00.168. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gibiino G, Lopetuso LR, Scaldaferri F, et al. Exploring Bacteroidetes: Metabolic key points and immunological tricks of our gut commensals. Dig Liver Dis. 2018;50(7):635–639. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2018.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lo Presti A, Zorzi F, Del Chierico F, et al. Fecal and mucosal microbiota profiling in irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1655. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Amabebe E, Robert FO, Agbalalah T, et al. Microbial dysbiosis-induced obesity: Role of gut microbiota in homoeostasis of energy metabolism. Br J Nutr. 2020;123(10):1127–1137. doi: 10.1017/S0007114520000380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Coppo R. The gut-kidney axis in IgA nephropathy: Role of microbiota and diet on genetic predisposition. Pediatr Nephrol. 2018;33(1):53–61. doi: 10.1007/s00467-017-3652-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liong MT. Beneficial microorganisms in medical and health applications. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2015. [Google Scholar]