Abstract

Background

The spread of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States has centered the role of natural hazards such as pandemics into the public health sphere. The impacts of these hazards disproportionately affect people with disabilities, who are frequently in situations of social, political, or economic disadvantage. Because of these disadvantages, people with disabilities may have less access to necessary resources and services, putting them at risk due to unmet health needs. These disparities in access also highlight important regional, state, and county-level differences with regards to vulnerability and preparedness for natural hazards.

Objective

The objective of this paper is to examine the relationship between disability and disaster risk in the United States. We examine the geographic variation in the relationship between risk from natural disasters and the percentage of people with disabilities living in a community. Because emergency management functions in the U.S. are directed and enacted at the county level, we also explore how these relationships change across U.S. counties. In addition to the overall prevalence of people with disabilities, we disaggregate the population of people with disabilities by gender, race, ethnicity, age, and disability impairment type.

Methods

To measure risk of natural hazards, we use Expected Annual Loss index, a component of the 2020 National Risk Index, developed by Federal Emergency Management Agency, which identifies communities most at risk to18 natural hazards. We measure the percent of people with disabilities per county using the American Community Survey. We estimate the nationwide relationship between the proportion of people with disabilities and risk of natural hazards using ordinary least squares regression. To explore geographic differences in these relationships across the United States, we use a geographically weighted regression model to estimate local relationships for each county in the contiguous United States. We use mapping techniques to display regional differences across different disability demographic groups.

Results

Counties with higher percentages of people with disabilities have a lower risk of natural disasters. Across the United States, a one percent increase in prevalence of people with disabilities in a county is associated with two percent decrease in the natural hazard risk score. Small but statistically significant regional differences exist as well. County-specific estimates range from a five percent decrease to a one percent increase. Stronger associations between risk and the prevalence of people with disabilities are observed in the Midwest and parts of the Southwest and West, whereas the relationship across racial groups is more scattered across the United States.

Conclusion

In this study, nationwide results suggest that people with disabilities are more likely to live in communities with lower risk of natural hazards, but this relationship differs across U.S. counties and by demographic subgroups. These findings represent a contribution in further understanding the health and well-being of people with disabilities in the United States and the geographic variation therein.

Keywords: Disability, Natural disasters, County variation, Multi-scale geographic regression

1. Background

The increase in frequency and intensity of pandemics and extreme weather events have focused attention on vulnerability to natural hazards. Natural hazards are environmental phenomena that have the potential to impact societies and the human environment. In the context of natural hazards, vulnerability is the heightened probability of experiencing adverse impacts due to a natural hazard. Social vulnerability involves both heightened risks to the negative impacts of disasters, combined with lower levels of resources to rebound from the shocks associated with enduring a disaster [1]. The impacts of natural hazards disproportionately affect people with disabilities who are frequently in situations of social, political, or economic disadvantage [2]. Because of these disadvantages, people with disabilities may have less access to necessary resources and services, putting them at risk due to unmet health needs. The impacts of natural hazards on people with disabilities might vary geographically because hazards and resources differ by area. Prior studies suggest that mortality from natural hazards is spatially patterned [3]. More recent experiences from the COVID-19 pandemic revealed important social and geographic variation in incidence and mortality [4,5].

Growing evidence suggests that medically vulnerable populations—and in particular, people with disabilities—are at increased risk of adverse health and social outcomes resulting from natural hazards [6,7]; Gershon 2013, Stough 2018). Compared to persons without a disability, those with a disability experience disproportionate risks and encounter greater obstacles at all phases of disasters, including preparedness (Bethel et al., 2011; Smith and Notaro, 2015), response [6,8,9], and recovery (Stough et al., 2015). Evidence suggests people with disabilities shoulder disproportionate harm in the wake of natural disasters and face steep barriers in the disaster recovery stage [2]. For example, people with disabilities are up to four times more likely to die in disasters [10]. The families of people with disabilities also face challenges when trying to evacuate [11] and experience accessibility barriers, mistreatment, and exclusion when seeking assistance through emergency shelters [11,12]. People with disabilities can also face unique barriers during the recovery stage, like requiring more costly housing repairs relative to nondisabled residents [11].

Disability advocates have pointed to shortcomings in national and local emergency management systems as reasons for the disproportionate adverse outcomes faced by people with disabilities. In a statement to the U.S. House of Representatives Subcomitte on Emergency Preparedness, the U.S. National Council on Disability (NCD) argued that “… Frustratingly … people with disabilities and others with access and functional needs in emergencies are frequently overlooked or have their needs minimized, despite the urgency that surrounds the need to account for people with disabilities in all phases of emergency management, including mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery” [13]. A 2006 post-Hurricane Katrina and Rita report by the NCD noted that in New Orleans, “people with disabilities were disproprotionaltey affected by the Hurricanes because their needs were often overlooked or disregarded. Their evacuation, shelter, and recovery experiences differed vastly from the experience of people without disabilities” [14]. After Hurricane Sandy, a class action suit was filed on behalf of the city's residents with disabilities against the city for failing to adequately serve people with disabilities during and after the hurricane. The first of its kind, the suit went to trail and a federal judge ruled that the City of New York had violated the rights of residents with disabilities by failing to accommodate for their needs during emergencies [15]. These and other examples have increased calls to better identifying the areas of need for people with disabilities with the goal of improving disability-inclusive emergency management systems.

In a separate strand of inquiry, geographers and other social scientists have elaborated on the importance of place and local context in determining vulnerability to hazards. Existing evidence points to the joint significance of both individual and community-level factors in determining how people are affected by, and recover from, a hazardous event (Mitchell 1989; [[16], [17], [18]]. Recent evidence from the novel Coronoavirus-19 (COVID-19) pandemic has underscored the role of the local environment on social vulnerabilities to health emergencies, as well as highlighted the geographic disparities therein [5,19]; Tan et al., 2020).

In this paper, we examine spatial patterns in the United States at the county level in the prevalence of people with disabilities and risk of natural hazards. Our objective is to understand if and where people with disabilities are exposed to disaster risk. We use U.S. counties as our unit of observation because emergency management functions in the U.S. are directed and enacted at the county level, we measure risk of natural hazards using the Expected Annual Loss (EAL), which ranks communities’ risk according to the average economic loss in dollars resulting from natural hazards each year [20]. Our analysis examines the overall population of people with disabilities as well as subgroups based on gender, race, ethnicity, age, and type of disability. We use two types of regression analysis—ordinary least squares regression and Multiscale Weighted Regression Modeling (MGWR)—to examine the correlation between financial loss and disability prevalence. MGWR allows the relationship between people with disabilities and natural hazard risk to vary spatially in order to assess potential geographic differences in relationships. We test the hypotheses that (1) people with disabilities are more likely to live in counties where natural hazard risk is higher and (2) disability status is strongly predictive of living in counties that are at higher risk to natural hazards, even after controlling for other relevant geographic factors.

Documenting, analyzing, and mapping county-level variation in risk of natural hazards addresses a gap in place-specific information about the vulnerability of people with disabilities. Despite a rich existing literature, no study to our knowledge has simultaneously examined the vulnerability of people with disabilities to natural hazards and the role of the local geographies in which they live. This project bridges these two important ideas to fill an important gap in our understanding of disability and natural hazards through a combination of data collection, analysis, and data visualization.

2. Methods

2.1. Data and study sample

Our study sample includes almost all 3107 counties in the contiguous United States. We exclude counties in Hawaii, Alaska, and U.S. territories because the statistical method we use requires nearby county information [21]. We exclude three counties in the contiguous United States because of missing data on disability. The analysis also uses a number of publicly available county-level data sources from various federal agencies and academic sources. Measures of natural hazard risk come from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). County-level disability data are from American Community Survey (ACS) 5-Year Data Profiles, which estimate small-geography data as an average across five years. We use the ACS 2014–2018 5-Year Data Profiles, which were the most recent data available when we performed the analysis. We describe these data sources in more detail below.

2.2. Measures

2.2.1. Outcome measure

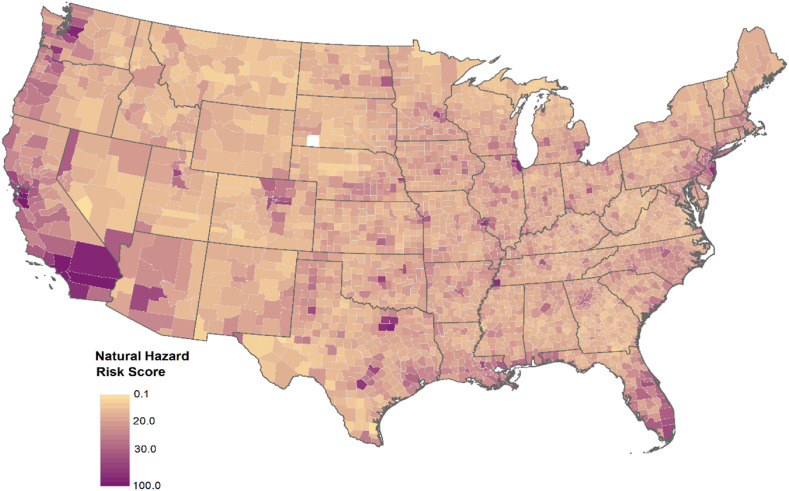

Our outcome of interest is the Expected Annual Loss (EAL) component of FEMA's National Risk Index. The EAL measures the average economic loss in dollars resulting from natural hazards each year. It is computed using 18 different hazard types including drought, wildfires, coastal flooding, hurricanes, landslides, heat and cold waves, and others. The EAL quantifies dollars lost—all inflated to 2020 dollars—across building values, agricultural land, and population. Building and agricultural losses are quantified in dollars based on physical loss. The EAL measures population loss as the number of fatalities and injuries, which is converted to dollar amounts using an actuarial Value of Statistical Life approach. The resulting composite index is a 0 to 100-point score for each county measuring the expected financial loss due to natural hazards. Dollar losses across relevant hazards are aggregated using specific mathematical formulas and then all county values are ranked [20]. Fig. 1 displays the geographic variation in EAL risk score across the United States at the county level.

Fig. 1.

Geographic variation in the Expected Annual Loss score for U.S. counties (N = 3107 counties). Source: FEMA EAL score from the National Risk Index.

The National Risk Index has two other components: Social Vulnerability, which measures susceptibility of social groups to natural hazards; and Community Resilience, which measures the ability of a community to prepare for and recover from the impacts of a natural hazard. Preliminary analyses revealed the Social Vulnerability and Community Resilience components of the National Risk Score might affect disability prevalence (and vice versa), creating an endogeneity issue that complicated using the National Risk Score as our outcome measure. The Social Vulnerability composite measure includes the percent of people with disabilities. Likewise, the Community Resilience metric does not directly include a count of people with disabilities but includes a number of social measures that are highly correlated with disability.1 Consequently, we cannot use either as an outcome measure.

We considered additional measures of disaster loss, including the Spatial Hazard Events and Losses Database (SHIELD) data, maintained by the Arizona State University. Ultimately, we chose the FEMA measure for a few reasons. First, the FEMA measure was a normalized index rather than a total dollar amount, which meant it was easier to make comparisons across counties that might differ in size or rurality. Secondly, the FEMA measure was, we thought, more recognizable and easier to download and manipulate, making any eventual replication of our work by others simpler.

2.2.2. Disability measures

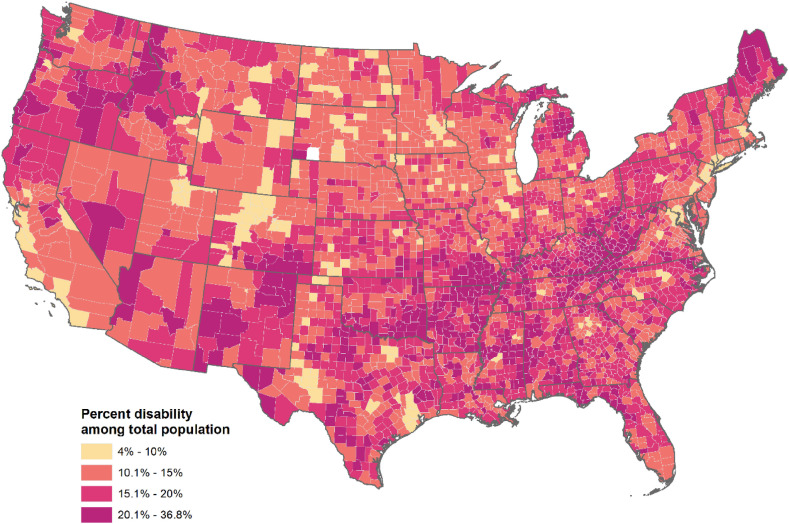

The disability measures come from the ACS. The ACS has a six-question sequence that captures six types of conditions: hearing difficulty, vision difficulty, cognitive difficulties, ambulatory difficulties, self-care difficulties, and independent living difficulties. Respondents have a disability if they report having one or more of the six conditions. The ACS disability measures are measured for all civilian non-institutionalized individuals; we include all respondents in our disability calculations. We calculate disability prevalence within each county as the number of people with a disability divided by the non-institutionalized county population, We also construct disability prevalence across subgroups based on gender (male, and female), race (White, Black, all other races, of any ethnicity), ethnicity (Hispanic, and non-Hispanic), age (ages 0–17 years, 18–64 years, and 65 years and over), and type of disability Following the ACS calculations, we calculate disability prevalence as the number of individuals in that subgroup with a disability divided by the non-institutionalized population of that subgroup within each county (ACS. The ACS records six impairment types, listed above. In our subgroup models, we tested all six impairment types separately. However, for four impairment types—cognitive difficulties, ambulatory difficulties, self-care difficulties, and independent living difficulties—our geographic weighted regression models did not converge. As such, in our discussion of subgroup analysis in this paper, we focus solely vision impairment and hearing impairment. (In our model of overall disability prevalence, all six impairment types are included in the total). Fig. 2 shows the geographic distribution of disability prevalence across the United States by county.

Fig. 2.

Geographic variation in the disability prevalence for U.S. counties (N = 3107 counties). Source: American Community Survey, 2014–2018 5-year estimates.

The ACS measures have been subject to criticism about a few notable limitations. One of the noted limitations of the ACS is the exclusion of incarcerated individuals. Given the high prevalence of disability among this population, this likely means the ACS disability counts are an underestimate of the true prevalence in a given county (Brault 2008). Moreover, because ACS measures focus on functional limitations, it may incorrectly count people with temporary difficulties and systematically undercount certain subgroups with enduring disabilities such as youth with psychiatric disabilities [22,23]. Still, the ACS is the only source of consistent, validated data on disability counts at county level (rather than a larger geographic area such as U.S. state or region). As such, we utilize the ACS measures despite these limitations.

2.2.3. Other county-level variables

The analysis includes a number of other county-level variables that were chosen based on existing literature. First, we consider land use within each county by calculating the percent of land that is barren and the percent that is highly developed. To calculate these statistics, we use information from the National Land Cover Database (NLCD). We obtained 30-m resolution raster data from the 2019 NLCD, which is satellite imagery data that classifies every 30-by-30 m unit of land into one of 16 mutually exclusive land cover categories using a modified Anderson Level II classification system (see https://www.mrlc.gov/data/type/land-cover for resources on land use classification). Barren land includes quarries, strip mines, gravel pits, bare rock, sand, clay, and transitional lands, whereas highly developed land include high intensity residential lands. To calculate the percent of barren land within a county, we divide the total area (in square meters) of barren land by the total area. We used an analogous approach to calculate the percent of highly developed land.

We also create a few additional control variables. To account for the density of agriculture without creating issues of collinearity with our outcome measure, we quantify the percentage of county employment in the agriculture and forestry industries. The data for this is from the ACS. We also measure county population density as the number of people per square mile using 2019 Census data. Our final set of county-level variables capture various demographic subgroups, including gender, race, ethnicity, and age. For each demographic subgroup, we measure county-level prevalence.

2.3. Statistical analysis

The analysis estimated two types of regression models to examine correlations between disability prevalence and EAL. In this section, we motivate and describe each regression model. We estimated all models using MGWR 2.2 software (available at https://sgsup.asu.edu/sparc/mgwr).

2.4. National model: ordinary least squares regression

We used ordinary least squares regression (OLS) to estimate the overall relationship between disability prevalence and EAL. We estimated 13separate OLS models in order to estimate the relationship with overall disability prevalence as well as the 12 subgroups These 12 additional models estimate the relationship between county-level disaster risk and the prevalence of people with disabilities of each of the following demographic subgroups: gender (male and female), race (White, Black, All other races), ethnicity (Hispanic and not Hispanic), age (under 18 years, 18–64 years, 65 years and older), and disability impairment type (vision and hearing). The models used identical control variables and specifications, except for subgroup-specific characteristics. We report results for each of these separate 13 models. The OLS model can be expressed as follows:

| (1) |

where y i is the log-transformed hazard risk score (expected financial losses) for county i, β 1 represents our parameter of interest, x 1i is disability prevalence, represents an array of county-level characteristics, and ε i is the random error term. The county-level characteristics in the array include the percent of land that is barren, the percent of land that is highly developed, the percent of employment due to agriculture, population density, and (for the subgroup models) the proportion of the county-level population the subgroup represents. We log-transformed the hazard risk score to adjust for non-normality. We searched for collinearity by assessing the variance inflation factor and tested for the presence and influence of outliers.

2.5. Testing geographic differences: multiscale geographically weighted regression

We also estimated a MGWR model to examine variation in the relationship between disability prevalence and hazard risk (Fatheringham, Yang & Wang 2017). Unlike OLS, MGWR captures the relationships between covariates and outcomes for every geographical unit in the regression, creating location-specific parameter estimates. To achieve this, MGWR performs a series of local regressions that utilize information from nearby locations, weighting the information based on distance from the location in question. Data from distant locations receive a relatively smaller weight than data from nearby locations. For each model covariate, a bandwidth parameter determines which neighboring locations are included in the estimation procedure [21,[24], [25], [26], [27], [28]]. Our analysis used an adaptive kernel function with a bi-square weighting function of the nearest neighbors to fit the MGWR model.

Though the MGWR model uses a different methodology, the model specification follows a similar structure as the OLS model. Our MGWR model can be expressed as follows:

| (2) |

where y i is the dependent variable for county i, α i is the intercept for county i, x ij represents the jth covariate x for county i, λ ij is the parameter estimate for the jth covariate for county i, and ε i is the random error term for county i. We estimate 16 different model specifications, one for each demographic subgroup of disability and with identical control variables and log-transformed outcome variable—expected financial loss from hazards. Though MGWR has many advantages, it cannot simultaneously control for several categorical variables. Consequently, we estimate separate models for each demographic subgroup rather than estimating one model that controls for all subgroups of interest.

To facilitate interpretations of the results, we mapped meaningful parameter estimates generated from the MGWR model using ArcMap 10.8. These maps display the statistically significant local estimates for each covariate. We determined statistical significance using an adjusted t-statistic that accounts for multiple hypothesis testing and spatial dependency [29].

3. Results

Table 1 displays summary statistics for EAL, measures of disability prevalence by demographic group, and other county-level variables. The rightmost column describes correlations between the EAL risk score and the other measures. Across counties, the EAL range from a minimum of 0.1 (Loving County, TX) to a maximum of 100 (Los Angeles County, CA), with a mean of 14.1. The average prevalence of disability within a county is 16% and ranges between 4.0 and 36.8%. Disability prevalence also varies by demographic group. The mean disability prevalence for race, ethnicity, and gender are all relatively similar to the overall prevalence, ranging from 14.1% for people with disabilities of “all other” races to 17.3% for people with disabilities who are Black. As expected, disability prevalence is positively correlated with age: people aged 65 and older are more likely to have a disability than younger individuals. The prevalence of hearing impairments is approximately twice as high than that of vision impairments, at 6.9% and 3.4% prevalence, respectively.

Table 1.

Summary statistics for variables analyzed and bivariate correlations with county EAL Risk Index for all U.S. counties.

| Variable | Minimum | Maximum | Mean | Standard Deviation | Pearson's r (Risk Index) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EAL Risk Index, financial loss (0–100) | 0.1 | 100.0 | 14.1 | 7.2 | – |

| Percent with a disability (%) | |||||

| Overall percent with a disability | 4.0 | 36.8 | 16.0 | 4.4 | −0.32 |

| Gender | |||||

| Female | 3.6 | 36.3 | 15.5 | 4.4 | −0.27 |

| Male | 2.5 | 38.7 | 16.4 | 4.9 | −0.35 |

| Race | |||||

| White | 5.2 | 36.5 | 16.2 | 4.5 | −0.31 |

| Black | 0.0 | 100.0 | 17.3 | 15.9 | −0.11 |

| Other race | 0.0 | 100.0 | 14.1 | 9.4 | −0.22 |

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Non-Hispanic | 0.0 | 100.0 | 16.4 | 9.6 | −0.20 |

| Hispanic | 5.2 | 53.4 | 16.8 | 4.6 | −0.27 |

| Age | |||||

| Under 18 years old | 0.0 | 20.8 | 4.8 | 2.2 | −0.07 |

| 18–64 years old | 1.5 | 36.7 | 13.5 | 4.7 | −0.26 |

| 65+ years old | 0.0 | 67.2 | 28.6 | 8.1 | −0.18 |

| Impairment | |||||

| Hearing | 10.1 | 72.3 | 32.1 | 6.9 | −0.27 |

| Vision | 0.3 | 66.7 | 4.8 | 3.4 | −0.45 |

| Other county-level variables | |||||

| Land that is barren (%) | 0.0 | 14.5 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.11 |

| Land that is highly developed (%) | 0.0 | 8.8 | 0.2 | 0.4 | 0.64 |

| County employment in nature (%) | 0.0 | 60.5 | 6.7 | 7.4 | −0.35 |

| Population density (average population per square mile) | 0.2 | 72,053 | 272 | 1813 | 0.33 |

Source: Author's calculations of various data sources described in text.

Notes: Disability percentages are based on the civilian non-institutionalized population. For the subgroups, we define disability prevalence as the number of individuals in that subgroup with a disability divided by the non-institutionalized population of that subgroup. Pearson's r signifies the correlation coefficient between the row variable and the natural hazard risk score.

n = 3107 counties.

The correlation between disability prevalence and natural hazard risk is −0.32, implying that higher prevalence of disability within a county is associated a lower hazard risk. There is no discernible pattern in the correlations across disability subgroups expect that they are all negative. The correlations range from −0.07 (younger than age 18) to −0.45 (vision impairment).

3.1. National model: ordinary least squares regression

The results of the OLS model reveal a small but statistically significant negative relationship between the prevalence of disability and natural hazard risk in a county. Table 2 summarizes the results for all models for both the national model and the MGWR models. The leftmost column displays the results of the OLS model, where each row represents a different model considering a different demographic subgroup. The coefficient for overall disability prevalence is 0.98. Because these are exponentiated coefficients, the coefficient means that a one percent increase in disability prevalence in a county is associated with a 2% decrease in the EAL. The R-squared coefficient for the model is 0.44, meaning that are combined variables in the model explain 44% of the variance in natural hazard risk across counties.

Table 2.

Coefficients from national and local models of EAL Risk Index (financial loss, logged) of people with disabilities, total and for different characteristics.

| Disability measure | National model % Change |

Local model: mean | Local model: minimum | Local model: maximum | Percentage of counties that pass the significance threshold (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall percentage with a disability | −2.00*** | −1.60 | −5.10 | 0.90 | 61 |

| Gender | |||||

| Percent male with disability | −2.00*** | −1.80 | −5.70 | −0.80 | 62 |

| Percent female with disability | −1.80*** | −1.10 | −1.20 | −1.00 | 100 |

| Race | |||||

| Percent white with disability | −1.90*** | −2.10 | −5.10 | −0.90 | 68 |

| Percent black with disability | −0.20*** | −0.20 | −0.80 | 0.30 | 18 |

| Percent other race with disability | −0.60*** | −0.20 | −0.40 | −0.10 | 52 |

| Ethnicity * | |||||

| Percent non-Hispanic with disability | −0.40*** | −0.25 | −0.26 | −0.24 | 100 |

| Percent Hispanic with disability | −1.50*** | −1.34 | −1.60 | −1.19 | 100 |

| Age | |||||

| Percent under 18 with disability | −0.07** | −0.53 | −0.65 | −0.12 | 7 |

| Percent 18–64 with disability | −1.30*** | −1.92 | −6.13 | 2.30 | 29 |

| Percent 65 or older with disability | −0.50*** | −0.69 | −1.66 | 1.50 | 16 |

| Impairment (no ref, not mutually exclusive) | |||||

| Percent with disability: Hearing | −0.50*** | −0.45 | −0.45 | −0.44 | 100 |

| Percent with disability: Vision | −4.30*** | −5.30 | −14.87 | −1.27 | 73 |

Source: Author's calculations of various data sources described in text.

Note:***p < 0.001; **p < 0.01; *p < 0.05; n = 3107 counties. Each category of disability characteristic (ie. gender, race, ethnicity, age, and impairment) are run as categorical variables in separate models and represent the share of the total population of that characteristic. All models adjusted for population density, percent of land that is highly developed, percent of land that is barren, the percent of employment due to agriculture and forestry, and the total prevalence in the total population of the demographic group in question.

There is some limited variation in this relationship by demographic subgroup. The strongest relationship was between the hazard risk score and vision impairment: a one percent increase in the prevalence of vision impairment is associated with a 4.3% decrease in the natural hazard risk score. For several subgroups— people with disabilities who are Black, “all other” races, non-Hispanic age 65 and older, and having hearing impairments—the relationship between disability prevalence and natural hazard risk is very close to 1, meaning there is no relationship between prevalence and risk. For all other subgroups, coefficients for the national model were less than one, representing a negative relationship between disability prevalence and the risk of natural hazard. R-squared coefficients for all models are between 0.38 and 0.52.

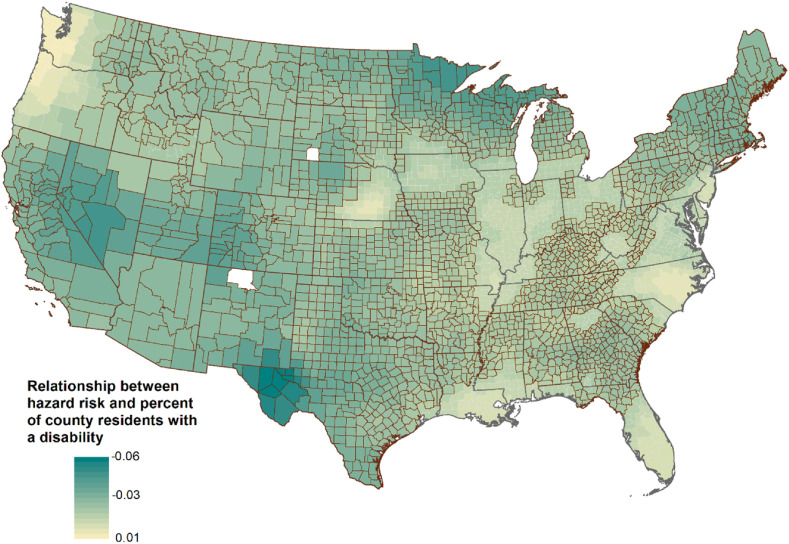

3.2. Testing geographic differences: multiscale geographically weighted regression

The remaining columns in Table 2 display the results of the MGWR models. These represent county-specific relationships between natural hazard risk and the prevalence of overall disability (in the first row) and demographic subgroups (in the remaining rows). Each coefficient can be interpreted the same way as the OLS model, representing the percent change in the risk score for a one percent increase in disability prevalence in that county. The county-specific estimates for overall disability range from 0.98 to 1.01, translating to a decrease in risk score of 1.6% to an increase of 1.0%. Model diagnostics show a spatialized element to the relationship: the R-squared coefficient for the local regressions are greater than for the OLS model, ranging from 0.70 to 0.82.

Not all county-specific relationships are statistically significant.1 Table 2 displays the percent of all counties in our sample that are statistically significant, and all results only report on the sample of statistically significant counties.2

Notes: Values of the legend represent the percent decrease in EAL risk score as a function of a one percent increase in disability prevalence. Counties with borders represent counties with statistically-significant coefficients.

Fig. 3 displays the geographic variation in county-specific relationships between the EAL hazard risk score and county disability prevalence. Stronger negative relationships between hazard risk and disability prevalence can be found in parts of the West and Southwest, the utmost northern parts of the Midwest and Northeast, and West Texas. Counties with small but positive relationships between hazard risk and disability prevalence are clustered largely in the center of the United States, the Eastern Seaboard, and the Appalachian region.

Fig. 3.

Geographic variation in the relationship between county disability prevalence and county natural hazard risk for U.S. counties (N = 3107 counties). Source: Authors' calculation of various data sources.

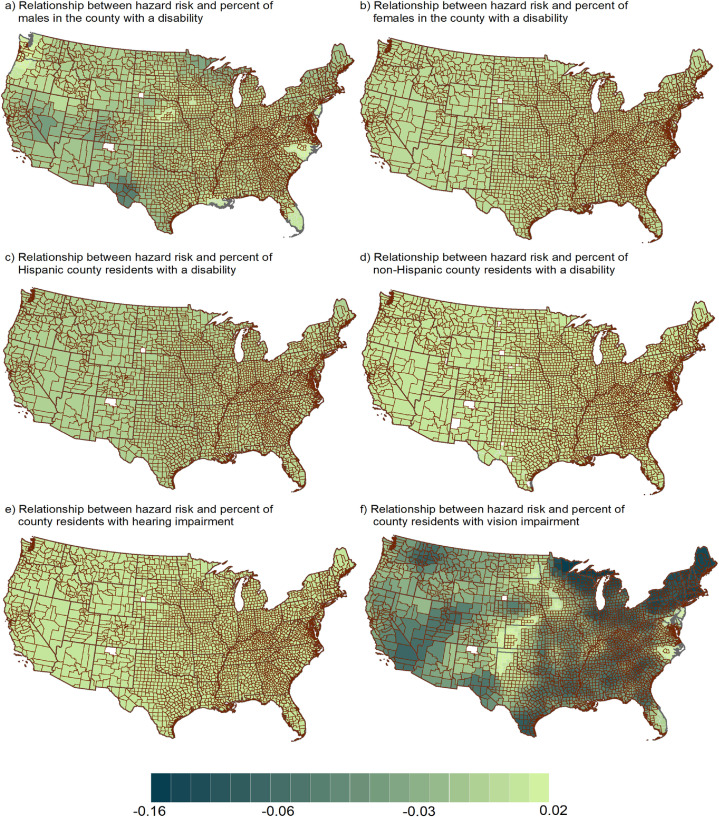

The intensity of spatial patterning between disability and hazard risk varied by subgroup (Fig. 4 ). For some subgroups, such as females and both ethnicity groups, there is little observed difference across counties. Other subgroups, such as vision impairments, exhibit a large range of relationships across counties. In addition, some models have greater shares of statistically significant counties. (As mentioned above, we do not report findings for four disability impairment types—cognitive difficulties, ambulatory difficulties, self-care difficulties, and independent living difficulties—because our models did not converge.)

Fig. 4.

Geographic variation in the relationship between and natural hazard risk and disability prevalence of select subgroups for U.S. counties (N = 3107 counties). Source: Authors' calculation of various data sources. Notes: Values of the legend represent the percent decrease in EAL risk score as a function of a one percent increase in disability prevalence. Counties with borders represent counties with statistically-significant coefficients.

Table 3 lists the 15 counties with the strongest and weakest relationships between overall prevalence of disability and natural hazard. The counties with the strongest relationships are nearly all in Texas, except for one county in New Mexico and two counties in Minnesota. The counties with the weakest relationships have a greater geographic distribution across the United States but are mostly in the South and the southern Midwest, including in Arkansas, Tennessee, Missouri, Virginia, and Alabama. The counties with stronger relationships usually have lower natural hazard risk scores, lower disability prevalence, and smaller populations. The mean value of the EAL risk score for the counties with the strongest relationship represents the 17th percentile, whereas the mean risk score for the 15 counties with the weakest relationship represents the 56th percentile.

Table 3.

List 15 counties with the strongest and weakest coefficients from MGWR regression (EAL and overall percentage of people with disabilities).

| County | State | Coefficient for EAL Score (%) | EAL Score | Total Population | Percent of population with disability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| The 15 counties with the strongest relationship between people with disabilities prevalence and natural hazard risk | |||||

| Loving | Texas | −5.49 | 0.1 | 82 | 21.42 |

| Reeves | Texas | −5.47 | 9.1 | 13,783 | 11.48 |

| Ward | Texas | −5.4 | 5.4 | 10,658 | 10.40 |

| Jeff Davis | Texas | −5.18 | 7.7 | 2342 | 14.01 |

| Winkler | Texas | −5.16 | 4.2 | 7110 | 11.23 |

| Culberson | Texas | −5.11 | 4.5 | 2398 | 20.47 |

| Pecos | Texas | −5.01 | 9.0 | 15,507 | 10.21 |

| Presidio | Texas | −4.95 | 6.6 | 7818 | 21.51 |

| Crane | Texas | −4.94 | 4.9 | 4375 | 6.67 |

| Eddy | New Mexico | −4.67 | 12.8 | 53,829 | 13.28 |

| Hudspeth | Texas | −4.54 | 3.6 | 3476 | 22.65 |

| Brewster | Texas | −4.53 | 12.2 | 9232 | 18.43 |

| Ector | Texas | −4.31 | 22.3 | 13,7130 | 10.78 |

| Cook | Minnesota | −4.29 | 5.1 | 5176 | 13.50 |

| Koochiching | Minnesota | −4.22 | 3.6 | 13,311 | 17.40 |

| Mean | −4.89 | 7.4 | 19,082 | 14.90 | |

| The 15 counties with the weakest relationship between people with disabilities prevalence and natural hazard risk | |||||

| Independence | Arkansas | −0.977 | 16.2 | 36,647 | 20.12 |

| Fayette | Tennessee | −0.977 | 13.3 | 38,413 | 16.28 |

| Oregon | Missouri | −0.981 | 9.8 | 10,881 | 26.56 |

| Sharp | Arkansas | −0.982 | 13.8 | 17,264 | 27.07 |

| Lee | Virginia | −0.983 | 10.4 | 25,587 | 26.01 |

| Dent | Missouri | −0.989 | 12.1 | 15,657 | 22.59 |

| Carter | Kentucky | −0.996 | 13.5 | 27,720 | 19.79 |

| Henderson | Tennessee | −1.002 | 13.4 | 27,769 | 18.44 |

| Marshall | Alabama | −1.004 | 16.3 | 93,019 | 14.72 |

| Barry | Missouri | −1.004 | 16.7 | 35,597 | 17.38 |

| Benton | Arkansas | −1.005 | 22.3 | 221,339 | 10.12 |

| Scott | Virginia | −1.006 | 9.9 | 23,177 | 27.81 |

| Cullman | Alabama | −1.008 | 16.2 | 80,406 | 17.70 |

| Vinton | Ohio | −1.018 | 9.9 | 13,435 | 21.88 |

| Neshoba | Mississippi | −1.019 | 13.4 | 29,676 | 20.86 |

| Mean | −0.997 | 13.8 | 46,439 | 20.49 | |

Source: Author's calculations of various data sources described in text.

Note: Top and bottom counties are ranked according to the size of the coefficient on the regression model with the overall EAL as the outcome variable. These listings include only significant coefficients at p ≤ 0.05. The listing includes all counties included in the regression, even counties with very small populations. The reader may note that the list of counties in Texas include some counties with very small population sizes, for example Loving County, Texas with a population of 82 persons. All models adjusted for population density, percent of land that is highly developed, percent of land that is barren, the percent of employment due to agriculture and forestry, and the total prevalence in the total population of the demographic group in question.

3.3. Sensitivity analysis

To test the sensitivity of these analyses, we estimated two sets of model specifications. First, we ran the same models on the subset of counties above and below populations of 5000 people and 1000 people; the regression estimates were nearly identical. Second, we tested the sensitivity of our models to outliers. We re-estimated all OLS and MGWR models while excluding the top and bottom one percent of counties for each disability prevalence subgroup. Again, the results were very similar to the main model estimates.

4. Discussion

This study is the first to our knowledge to explore the geographic variation in hazard risk and disability. By focusing on spatial and demographic heterogeneity, this study provides a more nuanced view of these relationships. We find that counties with higher percentages of people with disabilities tend have a lower risk of natural disasters. Results reveal that though there is high geographic variation at the county level in risks for natural hazards, counties with higher disability prevalence tend to have lower risk of natural hazards. Nationally, a one percent increase in prevalence of people with disabilities in a county is associated with a two percent decrease in the EAL score. Though regional differences exist, the range of differences is small. County-specific estimates range from a five percent decrease to a one percent increase in natural hazard risk score. Stronger associations between risk and the prevalence of people with disabilities are observed in the Midwest, Northeast, and parts of the Southwest and West. The relationships across disability demographic subgroups and impairment types also exhibit variation, though the strength of the patterns differs by demographic group. We observe stronger geographic variation for certain impairment types and by gender, but less for race, ethnicity and age.

Our findings suggest that people with disabilities are more likely to live in parts of the country that have lower natural hazard risk, which does not support our first hypothesis. Initially, we found this result somewhat surprising, in light of the evidence about heightened individual risk that people with disabilities face in natural disasters. However, this paper highlights how studies using different unit of observations can reveal new findings [30]. Our findings suggest that at a county-level, the prevalence of disability is inversely related to disaster risk. However, these findings are not mutually-exclusive with growing evidence that at the individual level, people with disabilities may be more vulnerable and need more supports during natural disasters [10,31,32]. Individuals with disabilities may be less concentrated in regions of the U.S. with higher natural disaster risk, but may be have disproportionately adverse outcomes when natural disasters do strike [33] and face higher barriers to recovering following disasters [34].

With this in mind, these results lend themselves to a few potential explanations. One possible explanation for this relationship is that of residential selection, wherein people with disabilities chose to live in and move to lower-risk areas. While we have controlled for various aspects of the county, such as the urbanicity/rurality of a county, there are a number of aspects of the county that have not been considered. This could be because of these areas have lower risk of natural disasters, or because these counties with lower hazard risk score may be associated with other characteristics not considered in this analysis, such as higher presence of services or greater accessibility in the built environment. Little has been published on residential selection for people with disabilities. Still, people with disabilities cite accessible and affordable housing, access to transportation, and ample support services as key aspects of successful community living (Tanzman 2006; [35]. It's possible that counties with lower disaster risk may have more resources dedicated to infrastructure that makes these communities more desirable for people with disabilities. Evidence on whether households with members who have a disability are more prepared during a natural disaster is mixed [36]. On the other hand, people with disabilities typically have fewer financial and social resources available to them [37], perhaps making choices about moving more limited. Indeed, people with disabilities are less likely to move to another county relative to their non-disabled counterparts (U.S. Census 2022). Another possibility is that these results could reflect differential mortality in disaster risk; people with disabilities are four times more likely to die during natural disasters [38]. More research is needed to examine the potential mechanisms and explanations for this finding.

Understanding geographic variation in disaster risk is critical to mounting an equitable and inclusive policy strategy for individuals with disabilities in the face of future natural hazards, particularly as weather-related disasters increase in frequency and intensity around the United States (NOAA, 2022). Our findings suggest that while there is some variation across subgroups, geographic differences are relatively small and don't deviate much for the national average. As such, potential policy implications are of national concern and not concentrated to specific localized communities. While the magnitude of risk of natural hazards may differ across geography, every community in the United States is vulnerable to some sort of hazard, whether it be storms, extreme temperatures, floods, or myriad other risks.

Calls for disability-responsive natural disaster risk reduction have been growing, and efforts have been made by FEMA and other federal agencies to consider and plan for the specific needs of people with disabilities during natural disasters [20]. Still, many barriers remain and people with disabilities remain disproportionately affected by natural disasters.

These findings represent a contribution in further understanding the health and well-being of people with disabilities in the United States and the geographic variation therein. By providing an examination on county-level disaster risk for residents with disabilities, this project hopes to advance the policy discussion by helping policy makers identify regions where there are unmet disaster preparedness needs for people with disabilities.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

1Funding for this study was provided by the Research and Training Center on Disability Statistics and Demographics at the University of New Hampshire, which is funded by the National Institute for Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research in the Administration for Community Living at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) under cooperative agreement 9ORTGE0001. The contents do not necessarily represent the policy of DHHS, and the reader should not assume endorsement by the federal government (EDGAR, 75.620 (b)).

Statistical significance is adjusted for multiple comparisons using an adjusted t-statistic threshold.

The fact that different models have different percentages of statistically significant counties can be due to a number of factors, including the distributional differences in characteristics across counties (e.g. different concentrations of racial groups across counties in the U.S.) and potential differences in the localized relationships (e.g. depending on the risk of hazards and the prevalence of disability, some relationships may be meaningful in some geographies and not in others).

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.Drakes O., Tate E., Rainey J., Brody S. Social vulnerability and short-term disaster assistance in the United States. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduc. 2021;53 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Subramaniam P., Villeneuve M. Advancing emergency preparedness for people with disabilities and chronic health conditions in the community: a scoping review. Disabil. Rehabil. 2020;42(22):3256–3264. doi: 10.1080/09638288.2019.1583781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borden K.A., Cutter S.L. Spatial patterns of natural hazards mortality in the United States. Int. J. Health Geogr. 2008;7(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-7-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cocco P., Meloni F., Coratza A., Schirru D., Campagna M., De Matteis S. Vaccination against seasonal influenza and socio-economic and environmental factors as determinants of the geographic variation of COVID-19 incidence and mortality in the Italian elderly. Prev. Med. 2021;143 doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2020.106351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Parcha V., Malla G., Suri S.S., Kalra R., Heindl B., Berra L.…Arora P. Geographic variation in racial disparities in health and coronavirus Disease-2019 (COVID-19) mortality. Mayo Clin. Proc.: Innovations, Quality & Outcomes. 2020;4(6):703–716. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2020.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chou Y.J., Huang N., Lee C.H., Tsai S.L., Chen L.S., Chang H.J. Who is at risk of death in an earthquake? Am. J. Epidemiol. 2004;160(7):688–695. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Balbus J.M., Malina C. Identifying vulnerable subpopulations for climate change health effects in the United States. J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2009;51(1):33–37. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0b013e318193e12e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahimi M. An examination of behavior and hazards faced by physically disabled people during the Loma Prieta earthquake. Nat. Hazards. 1993;7(1):59–82. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bloodworth D.M., Kevorkian C.G., Rumbaut E., Chiou-Tan F.Y. Impairment and disability in the astrodome after Hurricane Katrina: lessons learned about the needs of the disabled after large population movements. Am. J. Phys. Med. Rehab. 2007;86(9):770–775. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31813e0439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stough L.M., Kelman I. Handbook of Disaster Research. Springer; Cham: 2018. People with disabilities and disasters; pp. 225–242. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Willigen M., Edwards T., Edwards B., Hessee S. Riding out the storm: experiences of the physically disabled during hurricanes bonnie, dennis, and floyd. Nat. Hazards Rev. 2002;3(3):98–106. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Twigg J., Kett M., Bottomley H., Tan L.T., Nasreddin H. Disability and public shelter in emergencies. Environ. Hazards. 2011;10(3–4):248–261. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gallegos J. National Council on Disability; Washington, D.C: 2021. NCD Statement for the Record House Subcomitte on Emergency Preparedness, Response and Recovery. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Powell R., Sheldon G. National Council on Disability; Washington, D.C: 2006. The Impact of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita on People with Disabilities: a Look Back and Remaining Challenges. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Santora M., Weisner B. 2013. Court Says New York Neglected Disabled in Emergencies. New York Times, Nov. 7 issue. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cutter S.L. Vulnerability to environmental hazards. Prog. Hum. Geogr. 1996;20(4):529–539. [Google Scholar]

- 17.King D. Reducing hazard vulnerability through local government engagement and action. Nat. Hazards. 2008;47(3):497–508. [Google Scholar]

- 18.National Academy of Sciences . The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2012. Disaster Reslience: A National Imperative. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chin E.T., Huynh B.Q., Lo N.C., Hastie T., Basu S. Projected geographic disparities in healthcare worker absenteeism from COVID-19 school closures and the economic feasibility of child care subsidies: a simulation study. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01692-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Federal Emergency Management Agency . 2021. Expected Annual Losses. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu H., Fotheringham A.S., Li Z., Oshan T., Kang W., Wolf L.J. Inference in multiscale geographically weighted regression. Geogr. Anal. 2020;52(1):87–106. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ward B., Myers A., Wong J., Ravesloot C. Disability items from the current population survey (2008–2015) and permanent versus temporary disability status. AJPH (Am. J. Public Health) 2017;107(5):706–708. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ipsen C., Chambless C., Kurth N., McCormick S., Goe R., Hall J. Underrepresentation of adolescents with respiratory, mental health, and developmental disabilities using American Community Survey (ACS) questions. Disability and Health Journal. 2018;11(3):447–450. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2017.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fotheringham S.A., Li Z., Wolf L.J. Annals of the American Association of Geographers; 2021. Scale, Context, and Heterogeneity: A Spatial Analytical Perpective on the 2016 US Presidential Election; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Z., Fotheringham A.S. Computational improvements to multi-scale geographically weighted regression. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2020;34(7):1378–1397. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Z., Fotheringham A.S., Oshan T.M., Wolf L.J. Measuring bandwidth uncertainty in multiscale geographically weighted regression using akaike weights. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2020;110(5):1500–1520. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oshan T.M., Li Z., Kang W., Wolf L.J., Fotheringham A.S. mgwr: a Python implementation of multiscale geographically weighted regression for investigating process spatial heterogeneity and scale. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019;8(6):269. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wolf L.J., Oshan T.M., Fotheringham A.S. Single and multiscale models of process spatial heterogeneity. Geogr. Anal. 2018;50(3):223–246. [Google Scholar]

- 29.da Silva A.R., Fotheringham A.S. The multiple testing issue in geographically weighted regression. Geogr. Anal. 2016;48(3):233–247. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Andrews E.E., Forber-Pratt A.J. Disability culture, identity, and language. The Positive Psychology of Personal Factors: Implications for Understanding Disability Vol. 1. 2022 pp 27:40. [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDermott S., Martin K., Gardner J.D. Disaster response for people with disability. Disability and health journal. 2016 Apr 1;9(2):183–185. doi: 10.1016/j.dhjo.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Quaill J., Barker R., West C. Experiences of individuals with physical disabilities in natural disasters: an integrative review. Australian Journal of Emergency Management, The. 2018 Jul;33(3):58–63. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stough L.M., Kang D. The Sendai framework for disaster risk reduction and persons with disabilities. International Journal of Disaster Risk Science. 2015;6(2):140–149. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stough L.M., Sharp A.N., Resch J.A., Decker C., Wilker N. Barriers to the long‐term recovery of individuals with disabilities following a disaster. Disasters. 2016;40(3):387–410. doi: 10.1111/disa.12161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cepeda E.P., Galilea P., Raveau S. How much do we value improvements on the accessibility to public transport for people with reduced mobility or disability? Res. Transport. Econ. 2018;69:445–452. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han Z., Wang H., Du Q., Zeng Y. Natural hazards preparedness in taiwan: a comparison of households with and without disabled members. Health Security. 2017;15(6):575–581. doi: 10.1089/hs.2017.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.She P., Livermore G.A. Material hardship, poverty, and disability among working‐age adults. Soc. Sci. Q. 2007 Dec;88(4):970–989. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Craig L., Craig N., Calgaro E., Dominey-Howes D., Johnson K. People with disabilities: becoming agents of change in disaster risk reduction. Emerging voices in natural hazards research. 2019 Jan 1:327–356. (Butterworth-Heinemann) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.