Abstract

Aims & objectives

Our study sought to determine if posterior wall (PW) involvement in associated both-column acetabular fractures (ABCAFs) is associated with different clinical outcomes, primarily rate of conversion to total hip arthroplasty (THA), in comparison to ABCAFs with no PW involvement.

Materials & methods

This retrospective observational cohort study was performed at two academic Level 1 trauma centers. Two study groups were identified. The first study group consisted of 18 patients who sustained an ABCAF with PW involvement (+PW). The second study group consisted of 26 patients who sustained an ABCAF with no PW involvement (-PW). All patients achieved a minimum 12-months of follow-up and/or received a THA conversion procedure at a time remote to their index open reduction internal fixation (ORIF) procedure. The primary outcome of this study was subsequent conversion to THA on the injured hip. The secondary outcome was the presence of post-operative pain at ≥6 months and/or complications.

Results

No difference in rate of conversion to THA between + PW (n = 4, 22.2%) and -PW (n = 3, 11.5%) groups was demonstrated (p = 0.419). Similarly, no differences were seen between groups regarding complication rate (p = 0.814) and post-operative pain (p = 0.142).

Conclusion

Involvement of the PW does not appear to create worse clinical outcomes in comparison to no involvement in ABCAFs particularly as it relates to ipsilateral joint replacement.

Keywords: Acetabular fracture, Associate both-column acetabular fracture, Posterior wall fracture, Total hip arthroplasty, Judet

Highlights

-

•

Posterior Wall involvement in Associated Both-Column acetabular fracture patterns may negatively influence patient outcomes.

-

•

Posterior wall involvement does not significantly increase the risk of conversion to Total Hip Arthroplasty (p = 0.419) or complication rate (p = 0.814) in Associated Both-Column acetabular fractures.

-

•

No difference was observed between groups regarding complication rates (p=0.814), long-term pain profiles (p=0.740) and survivorship (p=0.35).

1. Introduction

The treatment and morbidity profiles of acetabular fractures are principally associated with classification schema developed in the 1960's by Emile Letournel and his mentor Robert Judet.1 This classification system describes ten fracture patterns, five elementary and five associated, that specify various combinations of involvement of anterior (iliopubic) and posterior (ilioischial) columns, and anterior and posterior walls.2 Isolated posterior wall (PW) fractures are the most common of these patterns, accounting for approximately 24% of all acetabular fractures.2,3 This classification system also describes PW fracture involvement with transverse acetabular fractures as well as posterior column fractures separately, comprising two of the five associated patterns. Interestingly, PW fractures have been observed to occur in conjunction with the ABCAF pattern in an estimated 35–39% of all ABCAF cases, however, Judet and Letournel do not distinctly define this pattern.4,5 Currently, little is known as to the impact such PW involvement has on the clinical outcomes of ABCAFs.

Fractures of the PW can create gross hip instability given its role as the primary weight-bearing surface of the acetabulum. Accepted dogma is that disruptions of >40% of the PW creates hip instability, however more recent work has demonstrated similar instability with involvement of <20% of the posterosuperior wall.6,7 This compromise in joint integrity is reflected in a high total hip arthroplasty (THA) conversion rate of approximately 17% in acetabular fractures involving the PW.8 Gross instability of the hip is also a notable consequence of ABCAFs, in which the weight-bearing articular surface is split and detached from the sciatic buttress.2,4,9 When these injuries occur concurrently, articular surface disruption occurs in a novel pattern compared to elementary PW fractures or ABCAFs alone.5,10 The objective of this retrospective cohort study was to assess the effect this combined injury has on clinical outcomes, primarily rate of conversion to THA, in comparison to ABCAFs without PW involvement.

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

This study is a a retrospective cohort study comparing patients who sustained an ABCAF with PW involvement (+PW) to patients who sustained an ABCAF with no PW involvement (-PW).

3. Setting

This study was performed at two American College of Surgeons (ACS) Level 1 trauma centers. Study subjects were identified, and data was obtained using a Research Patient Data Registry query performed between the years 2007–2017.

4. Participants

We used the Research Patient Data Registry and queried for patients with CPT codes for acetabular fracture surgery (Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes 27226, 27227, and 27228) at any time during the period from 2007 to 2017. ABCAFs (AO/OTA 62C) were identified of which all patients were ≥18 years of age at the time of injury.11 Of note, these fractures were ABCAFs as defined by the Judet-Letournel classification system. In other words, all acetabular fracture patterns with injury to both columns such as transverse fractures or anterior column posterior hemi-transverse fractures were not included. Injury radiographs, including Judet views, and computed tomography (CT) scans of these fractures were reviewed by 2 fellowship trained orthopaedic trauma surgeons to confirm the presence or absence of an ipsilateral PW fracture. Examples of ABCAF cases with PW involvement are presented in Fig. 1. Following separation into the +PW and -PW cohorts, patients were screened for achievement of 12-months of follow-up. Some included patients met this follow-up criteria via completion of a Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information Score (PROMIS) survey for a separate trial approved by our institution's IRB at a time point >12-months from their index surgery. This survey collected data on multiple outcomes measures, including reoperation, since the index surgery and therefore was a sufficient source of follow-up data for these select patients that overlapped between this current study and the previous one. Patients who received a subsequent THA on the injured hip without achievement of 12-months of follow-up were also included. However, patients who received a THA during their index procedure were excluded. There was no maximum time point for conversion to THA.

Fig. 1.

Pre-operative CT (A), 3D-CT reconstruction (B), and intra-operative fluoroscopy following open reduction internal fixation (C) from 3 associated both-column acetabular fracture cases with posterior wall involvement.

5. Variables

The medical records of all eligible patients were reviewed. Demographic and injury-associated factors were collected including gender, age, mechanism of injury, and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). The CCI is a validated method for quantifying disease burden in which a single value is calculated from the weighting of various comorbid conditions.12 Multiple operative and post-operative factors and outcomes were also collected. These included length of surgery (in minutes), weight bearing restrictions at discharge, if post-operative complications occurred, if post-operative infection occurred, and if pain was present at 6 months from the time of index ORIF. To assess for the primary outcome, records were examined to determine if the patient received a subsequent THA on the injured hip at a time remote to the index ORIF. In patients that received a conversion to THA, the time between index ORIF and THA (in days) was calculated and recorded.

Operative fixation of ABCAFs was performed by fellowship trained orthopaedic trauma surgeons at both hospitals. A majority of the operative fixations (>97%) were performed using the iliioinguinal approach (IL) to the acetabulum. Fractures were reduced and fixed utilizing the standard medial, middle and lateral windows of the approach. When present, fractures of the PW were addressed with a lag screw often using an offset clamp through the middle and lateral window. Only three patients were addressed using different surgical approaches. One patient underwent surgery through a standard Kocher-Langenbeck (KL) approach; another through an extended iliofemoral approach and one patient needed dual approaches (IL and KL). The decision to undergo a subsequent THA procedure was based on surgeon recommendation and patient amenability taking into account indicators of hip post-traumatic osteoarthritis such as pain and limited range of motion.13

5.1. Data sources/management

We identified potential cases using our institutions’ Research Patient Data Registry, which can identify patients with specific demographics, diagnoses, laboratory tests, medications, molecular medicine, health history, microbiology, procedures, and providers. Once eligible patients were identified, further data was collected via a retrospective review of their medical records.

6. Bias

THA is an elective procedure in which the decision to undergo surgery depends not only on clinical indications, but surgeon preference and other patient factors. Therefore, the primary outcome of subsequent conversion to THA may have been influenced by bias. Additionally, severe osteoarthritis non-traumatic in origin is also an indication for THA, creating the possibility that not all study patients who underwent THA did so because of long term sequalae of their initial acetabular injury. We assessed for the influence of this factor by comparing the time from initial ORIF to THA between groups.

6.1. Study size

ABCAFs are uncommon injuries. Therefore, we maximized the number of eligible patients using data from 2 Level-1 trauma centers over a 10-year study period.

6.2. Quantitative variables

Categorical variables assessed in this analysis were were reported as counts and percentages. Continuous variables assessed in this analysis were reported as mean one standard deviation.

7. Statistical method

Statistical analyses were performed using the software IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, N.Y., USA) and R (RStudio Team (2016). RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA URL http://www.rstudio.com/). A Chi-squared test was used to compare categorical variables between study groups. A Student's t-test was used to compare continuous variables between study groups. A Kaplan-Meier curve was applied to compare survivorship to THA conversion between groups.

8. Results

8.1. Participants

72 ABCAFs in 72 patients were identified. Imaging review of these fractures yielded 25 ABCAFs in 25 patients (34.7%) in which an ipsilateral PW fracture was also present. The other 47 ABCAFs in 47 patients (65.3%) did not demonstrate any PW involvement. Following screening, 44 of these 72 patients (61.1%) were identified for inclusion in the final analysis. Of note, 5 patients were identified and excluded who received a THA during their index procedure. Eighteen eligible patients (40.9%) had an ABCAF with PW involvement and comprised the final “+PW” study group. The other 26 eligible patients (59.1%) had an ABCAF with no PW involvement and comprised the final “-PW” study group.

9. Descriptive data

Demographic and injury data are presented in Table 1. Of the 44 eligible patients, 34 (77.3%) were male and 10 (22.7%) were female. Average age of included patients was 54.5 years ( 14.2). No significant differences in % male (p = 1.00) or age (p = 0.505) between study groups were observed. 22 patients (50.0%) were injured in a fall, 17 patients (38.6%) were injured in a motorcycle or motor vehicle crash (MCC/MVC), 4 patients (9.1%) were injured as a pedestrian struck, and 1 patient (2.3%) was injured through a separate mechanism. Percentages of patients in each mechanism of injury category were not significantly different between study groups (p = 0.718). Overall mean CCI was 1.33 ( 1.2) with no difference observed between groups (p = 0.981).

Table 1.

Demographic & injury characteristics.

| Characteristics | All (n = 44) | +PW Group (n = 18) | -PW Group (n = 26) | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||

| Male, n (%) | 34 (77.3) | 14 (77.8) | 20 (76.9) | p = 1.000 | |

| Female, n (%) | 10 (22.7) | 4 (22.2) | 6 (23.1) | ||

| Age | Mean (±SD), years | 54.5 (±14.2) | 51.4 (±12.0) | 48.5 (±16.7) | p = 0.505 |

| Mechanism of Injury | |||||

| Fall, n (%) | 22 (50.0) | 8 (44.4) | 14 (53.8) | p = 0.718 | |

| MCC/MVC, n (%) | 17 (38.6) | 7 (38.9) | 10 (38.5) | ||

| Pedestrian Struck, n (%) | 4 (9.1) | 2 (11.1) | 2 (7.7) | ||

| Other, n (%) | 1 (2.3) | 1 (5.6) | 0 (0) | ||

| CCI | Mean (±SD) | 1.33 (±1.2) | 1.28 (±1.1) | 1.27 (±1.2) | p = 0.981 |

CCI, Charlson Comorbidity Index; MCC/MVC, Motorcycle crash/Motor Vehicle Crash; SD, Standard Deviation.

10. Outcome data & main results

Operative and post-operative outcomes are presented in Table 2. Of the 44 eligible patients, 7 (15.9%) received a subsequent THA although no difference in rate of conversion was observed between + PW (n = 4, 22.2%) and -PW (n = 3, 11.5%) groups (p = 0.419). The difference in mean time from ORIF to THA (in days) was also not statistically significant between groups (p = 0.073), although it appeared to be trending towards significance in which on average, +PW patients (793.0 days ± 402.6) received later conversions than -PW patients (223.7 days ± 169.4). Similarly, no significant difference was observed between the mean length of the index surgery (in min) (p = 0.566) and % of patients who were non-weight bearing at discharge (p = 0.505) between groups. Other post-operative outcomes including the presence of complications (all) (p = 0.814), infection (p = 0.740), and post-operative pain (p = 0.142) were not significantly different between + PW and -PW groups.

Table 2.

Operative & post-operative outcomes.

| Outcomes | +PW Group (n = 18) | -PW Group (n = 26) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Converted to THA | |||

| Yes, n (%) | 4 (22.2) | 3 (11.5) | p = 0.419 |

| No, n (%) | 14 (77.8) | 23 (88.5) | |

| Time from ORIF to THA | |||

| Mean (±SD), days | 793.0 (±402.6) | 223.7 (±169.4) | p = 0.073 |

| Length of Surgery | |||

| Mean (±SD), minutes | 197.0 (±63.3) | 214.8 (±93.7) | p = 0.566 |

| Weight Bearing at Discharge | |||

| Touch down WB, n (%) | 18 (100) | 24 (92.3) | p = 0.505 |

| Non-WB, n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (7.7) | |

| Post-Operative Complication (All) | |||

| Present, n (%) | 7 (38.9) | 8 (30.1) | p = 0.814 |

| Absent, n (%) | 11 (61.1) | 18 (69.9) | |

| Post-Operative Infection | |||

| Present, n (%) | 1 (5.6) | 2 (7.7) | p = 0.740 |

| Absent, n (%) | 17 (94.4) | 24 (92.3) | |

| Post-Operative Pain at ≥6months | |||

| Present, n (%) | 4 (22.2) | 1 (3.8) | p = 0.142 |

| Absent, n (%) | 14 (77.8) | 25 (96.2) | |

ORIF, Open Reduction Internal Fixation; SD, Standard Deviation; THA, Total Hip Arthroplasty; WB, Weight Bearing.

11. Other analyses

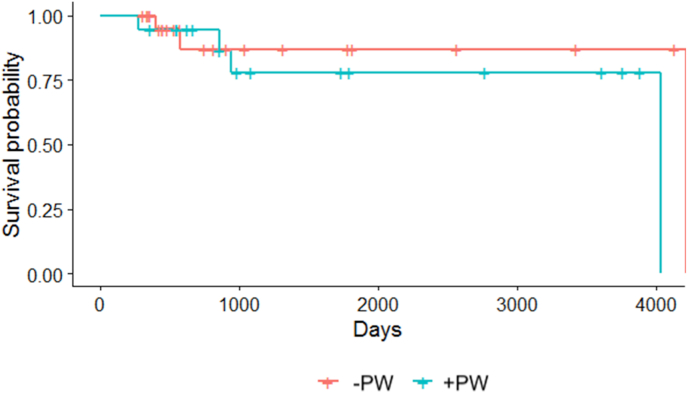

Fig. 2 is the Kaplan-Meier survival analysis comparing time to THA conversion between + PW and -PW groups. Results indicate no significant difference in survivorship (p = 0.350) between study groups.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan-Meier curve comparing survivorship to subsequent total hip arthroplasty between study groups. No difference between groups was demonstrated (p = 0.350).

12. Discussion

12.1. Key results

Associated both-column fractures of the acetabulum are highly unstable patterns characterized by complete dissociation from the sciatic buttress.2,4,9 We observed that in approximately one third of these injuries fracture of the PW is also present, a pattern not distinctly described in the Judet and Letournel classification system. Our study failed to demonstrate a difference in rate of conversion to THA (p = 0.419), presence of a post-operative complication (p = 0.814), or survival using the Kaplan-Meier Estimate (p = 0.350) between patients with and without PW involvement. It should be noted that our study demonstrated possible associations between increased incidence of post-operative pain as well as time from index ORIF to THA conversion in ABCAFs with PW involvement, although both differences failed to meet statistical significance at p = 0.142 and p = 0.073 respectively.

Our results are consistent with recent work by Min et al. who investigated outcomes of ABCAFs with and without PW involvement in a series of 42 patients.14 In this study the rate of conversion to THA in patients with PW involvement was found to be 17.6% compared to 12% in patients without such involvement with no significant difference between groups (p = 0.466). These conversion rates are nearly identical to those found in our review at 22.2% and 11.5% respectively. No difference in other complication rates between groups was found in this study (p > 0.405) which also agrees with our findings. In a separate study by Wang et al., a series of 99 patients with ABCAFs was investigated to determine the impact of PW involvement on clinical outcomes.15 This review did not record conversion to THA as an outcome measure, however, the presence or absence of severe hip arthritis was investigated demonstrating no difference based on PW involvement (p = 0.941). This study also utilized the Modified Merle d’Aubigne score to assess clinical outcome, finding no difference in the rate of excellent to good outcome scores between patients with and without PW involvement. Additionally, our finding that 35% of ABCAFs have associated PW disruption corroborates rates described by Gansslen et al. of 35% and Yang et al. of 39%.4,5

Results from our study failed to demonstrate PW involvement as a significant factor impacting the clinical course of ABCAFs. Despite creating a fracture profile with greater articular surface disruption, in our cohort we failed to demonstrate PW involvement as a significant risk factor that altered rates of THA conversion, distinct long-term pain, or complications in ABCAFs. The reason for this finding is hard to speculate, however, we believe that it relates to the unique PW fracture profile when it occurs in conjunction with an associated both-column injury. In an isolated PW fracture involving hip dislocation and/or impaction of the PW articular cartilage, poor outcomes including high rates of THA conversion are understood given this damage to the weight-bearing surface. However, when there is associated separation and displacement of both anterior and posterior columns as occurs in associated both-column injuries, damage to the PW occurs in a disparate pattern that does not appear to further compromise joint integrity.10,15 Therefore, the high THA conversion rate typically seen following PW fractures does not appear to compound THA conversion rates in ABCAFs with PW involvement in comparison to those without. It is also possible that ABCAFs with PW involvement have a worse natural history than those without, however, the unique treatment approach applied in these combined injuries is effective in offsetting the negative impact. Overall, this finding provides valuable information for providers and patients to help guide treatment decision making and predict long-term outcomes in these injuries.

13. Limitations & strengths

It is important that results of our study be interpreted in the context of the study design. Patient identification and outcome data was collected retrospectively allowing for potential surgeon and patient bias to impact results. THA is also an elective procedure and can be indicated when there is osteoarthritis of non-traumatic origin. This indicates that THA conversion rate is susceptible to surgeon bias, patient amenability, and other patient factors leading to potential over or under-estimation of the rate of THA conversion from PW involvement alone. We did assess for the potential impact of THA's performed for age-related rather than post-traumatic osteoarthritis by collecting time from ORIF to THA. No significant difference was demonstrated (p = 0.505) between average time from ORIF to THA between -PW and +PW groups suggesting neither group was particularly biased in comparison to the other by this factor. ABCAFs are also an uncommon injury with a low rate of conversion to THA, creating a small overall sample size and event group size with greater statistical fragility and chance for beta error. This study utilized a combined database of patients from two Level 1 trauma centers to create as large a patient cohort as possible considering this low incidence rate. This sample size was reduced even further following exclusion of 38.9% of originally identified patients for not meeting strict inclusion criteria. This may have introduced selection bias in our cohort but was a necessary step in preventing analysis of patients with inconclusive outcomes data that could bias results. This includes omitting the results of 5 patients who received a THA as their index procedure to protect the event rate from THA's biased by surgeon subjectivity and outcome assumptions. Minimum follow-up was also set at 12-months for those patients who did not receive a THA. This may have been a premature cutoff leading to the inclusion of patients who demonstrated clinical signs and symptoms of the need for arthroplasty at time points remote to their final follow-up. A minimum follow-up of 24-months was discussed as an alternative, although this would have excluded 16 of the 37 patients (43.2%) who did not receive a THA, drastically reducing overall sample size. In addition, more than 50% (4/7) of THA conversions occurred <12 months after index surgery, suggesting that 12 months was not necessarily too short of an interval to assess the primary outcome. Furthermore, the final mean and median follow-ups of included non-THA patients across both groups were 43 months and 26 months respectively. These factors ultimately led to the decision to keep the 12-month follow-up minimum. Lastly, we assessed outcome differences between study groups through multiple well-defined measures. It is possible, however, that other unmeasured variables exist that do effectively distinguish outcomes between groups.

14. Conclusion

In conclusion, our findings support previous work suggesting that PW involvement in ABCAFs does not signify an adverse recovery course for patients especially regarding the need for subsequent conversion to THA. Although this conclusion relies on preceding variables such as surgeon skill and the characteristics of each fracture, understanding that PW involvement singularly does not affect outcomes can help guide surgical planning and patient risk stratification when forecasting recovery course in the aftermath of these injuries.

Funding/sponsorship

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Informed consent

Due to this being a retrospective review with little risk to human subjects, informed consent from study participants was not required by the IRB.

Institutional ethical committee approval

This study's IRB protocol number is 2019P001498 approved on August 11th, 2019. All study procedures were in accordance with the ethical standards set forth by each institution and with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013).

CRediT author statement

G. Bradley Reahl: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing – Original Draft, Visualization. Michael F McTague: Software, Validation, Formal Analysis, Resources, Data Curation, Writing – Review & Editing, Project Administration. Nishant Suneja: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – Review & Editing. Michael J. Weaver: Conceptualization, Writing – Review & Editing. Malcolm Smith: Conceptualization, Writing – Review & Editing. Arvind G. von Keudell: Conceptualization, Writing – Review & Editing, Supervision.

Funding statement

This research was not supported through external funding.

Declaration of competing interest

None.

Acknowledgement

None.

References

- 1.Johnson E.E. The life and contributions of Emile Letournel, MD, 1927-1994. J Orthop Trauma. 2019;33 doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001393. (Sii-i) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Judet R., Judet J., Letournel E. Fractures of the acetabulum: classification and surgical approaches. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1964;46(A):1615–1646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Giannoudis P.V., Grotz M.R., Papakostidis C., et al. Operative treatment of displaced fractures of the acetabulum: a meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87(1):2–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gänsslen A., Frink M., Hildebrand F., et al. Both column fractures of the acetabulum: epidemiology, operative management and long-term results. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2012;79(2):107–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yang Y., Zou C., Fang Y. Mapping of both column acetabular fractures with three-dimensional computed tomography and implications on surgical management. BMC Muscoskel Disord. 2019;20(1):1–7. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2622-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Firoozabadi R., Spitler C., Schlepp C., et al. Determining stability in posterior wall acetabular fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2015;29(10):465–469. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000000354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reagan J.M., Moed B.R. Can computed tomography predict hip stability in posterior wall acetabular fractures? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(7):2035–2041. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1790-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Firoozabadi R., Hamilton B., Toogood P., et al. Risk factors for conversion to total hip arthroplasty after acetabular fractures involving the posterior wall. J Orthop Trauma. 2018;32(12):607–611. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moroni A., Caja V.L., Sabato C., et al. Surgical treatment of both-column fractures by staged combined ilioinguinal and Kocher-Langenbeck approaches. Injury. 1995;26(4):219–224. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(95)00007-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tian S., Chen Y., Yin Y., et al. Morphological characteristics of posterior wall fragments associated with acetabular both-column fracture. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-56838-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Meinberg E.G., Agel J., Roberts C.S., et al. Fracture and dislocation classification compendium – 2018. J Orthop Trauma. 2018;32(Supplement 1):S1–S170. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0000000000001063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Quan H., Li B., Couris C.M., et al. Updating and validating the Charlson comorbidity index score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676–682. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sierra R.J., Mabry T.M., Sems S.A., et al. Acetabular fractures: the role of total hip replacement. Bone Joint Lett J. 2013;95(11 Supplement A):11–16. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.95B11.32897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Min B.W., Lee K.J., Jung J.W., et al. Outcomes are equivalent for two-column acetabular fractures either with or without posterior-wall fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2018;138(9):1223–1234. doi: 10.1007/s00402-018-2953-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang H., Utku K., Zhuang Y., et al. Post wall fixation by lag screw only in associated both column fractures with posterior wall involvement. Injury. 2017;48(7):1510–1517. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2017.05.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]