Abstract

To evaluate the postoperative surgical wound infection prevalence rates of patients undergoing SL, identify the causative organism and determine predisposing factors leading to infection. A retrospective study of all consecutive patients who underwent salvage total laryngectomy at our unit between 2015 and 2020 was performed. The following parameters were also analyzed: age, smoking history, pre and postoperative albumin level, history of radio and chemo-radiotherapy, reconstruction with pectoralis flap, intraoperative tracheoesophageal puncture, and tumor stage. A total of 12 of the 21 patients (57%) experienced a postoperative infection after SL during the study period. 82% of those patients whose preoperative albumin level below 3gm/dl developed postoperative infection. There is a significant increase (p < 0.01) in infection in patients with N1 and 2 stage tumor (68%) compared with the N0 stage tumors (40%). Multivariate analysis showed that preoperative albumin and nodal stage were significant risk factors for postoperative infection.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12070-021-02603-y.

Keywords: Salvage, Laryngectomy, Infections, Prophylaxis

Introduction

Postoperative Surgical site infection (SSI) in head and neck ablative surgery is related to the perioperative exposure of the wound to bacteria [1–3]. The source of infection is mainly made from auto-contamination of the surgical wound [4, 5].

Postoperative infection can cause wound dehiscence, skin flap loss, and the formation of pharyngocutaneous fistulae, leading to increased length of hospital stay, morbidity and mortality [6, 7]. Surgical site infection after total laryngectomy can cause delayed access to the postoperative adjuvant therapy which increases the risk of loco-regional recurrence [8–10].

Prophylactic antibiotics are given at induction of surgery to prevents any organisms that inevitably contaminate the wound during surgery from establishing infection to reduce the incidence of postoperative wound infections. The use of appropriate prophylactic antibiotics in head and neck oncological surgery has been reported to reduce infection rates from 85 [11] to less than 10% [2]. However, the use of prophylactic antibiotics can lead to the development of antimicrobial resistance.

Current guidelines [12] recommend that prophylactic antibiotics should be started within 30 min of the induction of anesthesia. Despite this, infection rates are still reported in up to 40–61% of cases [13–15].

With the increasing use of non-surgical organ preservation therapies (OPT) for laryngeal carcinoma, salvage laryngectomy (SL) may be the only curative option. However, complication rates in the salvage laryngectomies, especially infection and wound dehiscence remain high. Patients undergoing SL are in the highest-risk group for postoperative complications, the most common of which is pharyngocutaneous fistulae (PCF) [16].

Although many factors that result in PCF have been described, there is still no agreement on the most significant ones. Amongst the several factors, site of primary tumor, T stage, nodal stage, preoperative radiotherapy, type of pharyngeal closure (vertical and T closure), technique of closure (full-thickness interrupted, submucosal interrupted, submucosal continuous) suture material, preoperative tracheostomy, cut margin status, pre and postoperative serum hemoglobin, pre and postoperative albumin levels, postoperative infection, and experience of surgeons [17].

This study aimed to evaluate the postoperative surgical wound infection prevalence rates of patients undergoing SL, identify the causative organism and determine predisposing factors leading to infection.

Materials and Methods

A retrospective study of all consecutive patients who underwent salvage total laryngectomy at our unit between 2015 and 2020 was performed. All patients were discussed and their management was agreed at the Multidisciplinary Head and Neck Oncology Tumor Board Meeting before surgery. All patients received antibiotic prophylaxis according to the standard prophylactic antibiotic policy. This involved giving intravenous ampicillin–sulbactam 1500 mg and metronidazole 500 mg within 30 min of anesthesia induction. Patients with cN0 node disease underwent a lateral neck dissection (LND), while those with nodal disease (cN1 and 2) underwent a modified radical neck dissection (MRND). All postoperative complications were recorded. Wound infections were categorized according to Tabet and Johnson’s manual on control of infection in surgical patients. Grade 4 is classified as a purulent discharge either spontaneous or by surgical drainage, and Grade 5 is classified as a pharyngocutaneous fistula (PCF) [2]. All patients who developed postoperative wound infection received initially empiric antibiotics which were modified according to the results of culture and sensitivity of the samples. Bacteriology data including microorganism isolated and results of antimicrobial susceptibility testing from wound swabs of patients were collected. The following parameters were also analyzed: age, smoking history, alcohol, co-morbidities, pre and postoperative albumin level, history of radio and chemo-radiotherapy, reconstruction with pectoralis flap, intraoperative tracheoesophageal puncture, and tumor stage.

Statistical Methods

Data were coded and entered using the statistical package SPSS version 25. Data was summarized using mean and standard deviation for quantitative variables and frequencies (number of cases) and relative frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables. Comparisons between groups were done using unpaired t test. For comparing categorical data, Chi square (× 2) test was performed. Exact test was used instead when the expected frequency is less than 5. P values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

Results

A total of 12 of the 21 patients (57%) experienced a postoperative infection after SL during the study period. Of these 12 patients, all developed PCF. All patients required postoperative antibiotic therapy. The time of postoperative infections ranged between 5 and 17 days, with average time to onset of 11 days.

Patient Characteristics

The mean age of patients included in this study was 65 years, with the vast majority being male (95%). All patients smoked tobacco, with an average pack year history of 35. No patients experienced alcohol consumption. There were no significant differences in the infection rate regarding diabetes or smoking history. Fisher’s exact test showed a significant difference (p = 0.023) in the frequency of infection between those with a pre-operative albumin above (30% incidence) and below 3 g/dL (82% incidence). Sublimentary Table 1 demonstrates the relationship between infection and patient characteristics.

Tumor Characteristics

Eighteen (86%) patients had cT3 or cT4 tumors (staged post-operatively), while 16 (76%) had a cN0 tumor. There was no significant difference in infection rates between patients with cT1 and 2 versus cT3 and 4, though Fischer’s exact test showed a statistically significant increase (p ≤ 0.01) in infections in those with cN1 and 2 versus cN0. Sublimentary Table 2 demonstrates the association between infection and tumor characteristics.

Operative Characteristics

Five patients (24%) had combined chemo-radiotherapy (CCRT), while another 16 had radiotherapy alone (76%). For those patients receiving CCRT, 3 patients developed postoperative infection and PCF. For those patients receiving RT alone, 9 patients developed postoperative infection and PCF. There was no significant increase in infections in those treated with RT versus those treated with CRT (p > 0.5). 4 patients (19%) had intraoperative pectoralis major myocutaneous flap (PMMCF) reconstruction, and none had a tracheoesophageal puncture. Interestingly, there is significant increase in infection in those who did not have PMMCF (65%) vs those who had PMMCF (25%) (p = 0.03). Sublimentary Table 3 summarizes the relationship between infection and operative characteristics.

Bacteriology Results

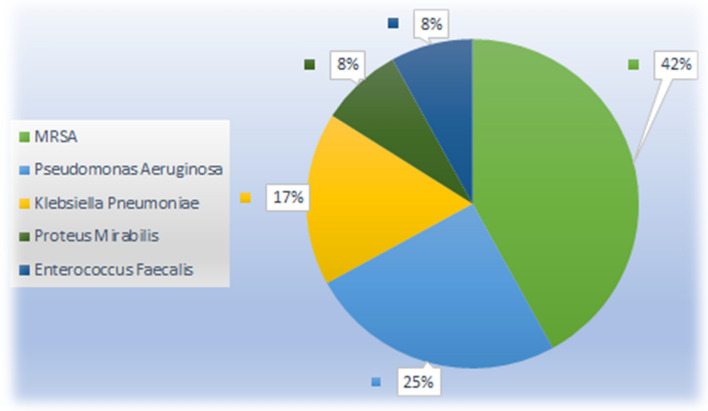

Bacteriological culture results were obtained for all patients who developed wound infections. The most common microorganism isolated from clinical specimens was methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in five patients (42%), followed by Pseudomonas aeruginosa in three patients (25%), Klebsiella pneumoniae in two patients (17%), Proteus mirablis and Enterococcus faecalis each occurring in one patient (8% each) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Bacteriology data regarding infectious organisms in PCF (n = 12)

Discussion

Surgical site infections are one of the most common nosocomial infections that increase postoperative length of stay in the hospital, morbidity, and mortality [18].

Salvage total laryngectomy remain the gold standard for management of failures of such treatment options and is more frequently associated with postoperative complications such as pharyngocutaneous fistulas and wound infection [19].

The local wound infection rates of 57% found in this study agree with other published reports. In a number of other studies infection rates have ranged from 40 to 61% [13–15]. In a study done by Weber et al. [20], analyzing data from the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group trial 91–11, stated that the overall wound infection rates is 59% of patients.

However, Park and his colleagues [21] stated that the local SSI rate after radical neck dissection in head and neck cancer was 19.7%. The local infection rate in our patients is higher than the previous study and this may be attributed to the preoperative chemo or radiotherapy that shares in the increase rate of infection.

The patient characteristics of our study agreed with other studies [22]: the mean age was 65 years, 95% were male and 100% were smoker with average pack year history of 33.

This study showed two variables that had a significant correlation with postoperative wound infection, namely cN stage of tumor, and preoperative albumin levels.

In this study, 82% of those patients whose preoperative albumin level below 3gm/dl developed postoperative infection and PCF. In a similar study by Scotton et al. [23], preoperative hypoalbuminemia was found to be a risk factor for the development of SSI in patients undergoing salvage head and neck surgery.

There is no significant difference in infection rates between those patients with T1 and 2 versus T3 and 4 tumors (p = 0.38), this may be due to small sample size of T1, T2 patients (n = 3).

Given that patients with cN0 node disease underwent a less extensive neck dissection (lateral neck dissection) than those withcN1 and 2 nodal disease (MRND), there is a significant increase (p < 0.01) in infection in patients with N1 and 2 stage tumor (68%) compared with the N0 stage tumors (40%). These findings agree with the study done by Qurayshi and his colleagues [17] and in opposite to the results of other studies [23, 24].

This study showed that there is significant increase in infection in those who did not have PMMCF (65%) vs those who had PMMCF (25%) (p = 0.03) raising the importance of flap coverage in salvage head and neck surgeries to minimize the postoperative infection and PCF. These findings agree with the study carried out by Mebeed et al. [25].

MRSA infection was the commonest agent isolated from our patients who developed PCF in this study. Previous studies found comparable results [5, 26, 27]. Preoperative screening for MRSA, decolonization using chlorhexidine and mupirocin as well as aggressive management with culture-directed antibiotics may lead to a decrease in postoperative infective complications [8, 27]. The patient should be given a targeted anti-MRSA prophylactic agent such as teicoplanin or vancomycin along with the standard antibiotic prophylaxis of choice at induction and continued for a further three doses.

The limitation of this study is the retrospective nature and small sample size, which reduces the statistical power achievable. Given the relatively small number of salvage laryngectomies carried out, to increase the patient sample size it will be necessary to run larger multi-center studies.

Conclusion

Infection rates following salvage laryngectomies are still high. Multivariate analysis showed that preoperative albumin and nodal stage were significant risk factors for SSI. Lastly, the most discovered pathogen was MRSA. Based on our results, we can predict certain groups of patients who are at high risk of developing postoperative infection after major head and neck surgery. Close collaboration between surgical, microbiology and infection control teams is essential to reduce the likelihood of postoperative infections.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author Contribution

AAN; made substantial contributions to the data collection, and manuscript writing and gave final approval of the manuscript version to be published. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any special grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data Availability

All data generated or analysed during this study had already been included in this manuscript. Patient’s case file was retrieved from the medical record section of the institution. The clinical data had been collected from the prospectively maintained computerized database and the case file. The follow-up status was updated from the above-mentioned manner.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors do not have any conflict of interest to declare.

Consent for publication

Written informed consent to publish the patient’s clinical details information was obtained from the study participant.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Murdoch DA, Telfer MR, Irvine GH. Audit of antibiotic policy and wound infection in neck surgery. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1993;38:167–1692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tabet JC, Johnson JT. Wound-infection in head and neck-surgery—prophylaxis, etiology and management. J Otolaryngol. 1990;19:197–2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scher KS, Bernstein JM, Arenstein GL, Sorensen C. Reducing the cost of surgical prophylaxis. Am Surg. 1990;56:32–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ifeacho SN, Bajaj Y, Jephson CG, Albert DM. Surgical siteinfections in paediatric otolaryngology operative procedures. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;76:1020–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2012.03.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lotfi CJ, Cavalcanti Rde C, Costa e Silva AM, et al. Risk fac-tors for surgical-site infections in head and neck cancer surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;138:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogihara H, Takeuchi K, Majima Y. Risk factors of post-operative infection in head and neck surgery. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2009;36:457–4605. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2008.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grandis JR, Snyderman CH, Johnson JT, Yu VL, Damico F. Post-operative wound-infection—a poor prognostic sign for patients with head and neck cancer. Cancer. 1992;70:2166–21706. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19921015)70:8<2166::AID-CNCR2820700826>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Simo R, French G. The use of prophylactic antibiotics in head and neck oncological surgery. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;14:55–617. doi: 10.1097/01.moo.0000193183.30687.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weber RS, Callender DL. Antibiotic prophylaxis in clean-contaminated head and neck oncologic surgery. Ann Otol Rhinolaryngology Suppl. 1992;155:16–208. doi: 10.1177/00034894921010s104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swift AC. Wound sepsis, chemoprophylaxis and major head and neck-surgery. Clin Otolaryngol. 1988;13:81–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1988.tb00746.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Becker GD, Parell GJ. Cefazolin prophylaxis in head andneck-cancer surgery. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1979;88:183–186. doi: 10.1177/000348947908800206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) (2008) Publication number 104: antibiotic prophylaxis in surgery: a national clinical guideline. Health Improv Scotlhttp://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign104.pdf

- 13.Penel N, Lefebvre D, Fournier C, Sarini J, Kara A, Lefebvre JL. Risk factors for wound infection in head and neck cancer surgery: a prospective study. Head Neck. 2001;23(6):447–45511. doi: 10.1002/hed.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Velanovich V. A meta-analysis of prophylactic antibiotics in head and neck surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1991;87(3):429–434. doi: 10.1097/00006534-199103000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sassler AM, Esclamado RM, Wolf GT. Surgery after organ preservation therapy analysis of wound complications. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;121:162–165. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1995.01890020024006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sundaram K, Wasserman JM. Prevention of unplanned pharyngocutaneous fistula in salvage laryngectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141:645–647. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qureshi SS, Chaturvedi P, Pai PS, Chaukar DA, Deshpande MS, Pathak KA, D'cruz AK. A prospective study of pharyngocutaneous fistulas following total laryngectomy. J Cancer Res Ther. 2005;1(1):51. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.16092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Berrios-Torres SI, Umscheid CA, Bratzler DW, et al. Centers or Disease Control and Prevention guideline for the prevention of surgical site infection. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:784–791. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kwon D, Genden EM, de Bree R, Rodrigo JP, Rinaldo A, Sanabria A, Rapidis AD, Takes RP, Ferlito A. Overcoming wound complications in head and neck salvage surgery. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2018;45(6):1135–1142. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2018.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weber RS, Berkey BA, Forastiere A, Cooper J, Maor M, Goepfert H, Morrison W, Glisson B, Trotti A, Ridge JA, Chao KSC, Peters G, Lee DJ, Leaf A, Ensley J. Outcome of salvage total laryngectomy following organ preservation therapy. the radiation therapy oncology group trial 91–11. Arch Otolaryngology Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:44–49. doi: 10.1001/archotol.129.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Park SY, Kim MS, Eom JS, Lee JS, Rho YS. Risk factors and etiology of surgical site infection after radical neck dissection in patients with head and neck cancer. Korean J Intern Med. 2016;31(1):162. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2016.31.1.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wakisaka N, Murono S, Kondo S, Furukawa M, Yoshizaki T. Post-operative pharyngocutaneous fistula after laryngectomy. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2008;35:203–208. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2007.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scotton W, Cobb R, Pang L, Nixon I, Joshi A, Jeannon JP, Oakley R, French G, Hemsley C, Simo R. Post-operative wound infection in salvage laryngectomy: does antibiotic prophylaxis have an impact? Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;269(11):2415–2422. doi: 10.1007/s00405-012-1932-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coskun H, Erisen L, Basut O. Factors affecting wound infection rates in head and neck surgery. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery. 2000;123(3):328–333. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.105253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mebeed AH, Hussein HA, Saber TKh, Zohairy MA, Lotayef M. Role of pectoralis major myocutanuos flap in salvage laryngeal surgery for prophylaxis of pharyngocutaneuos fistula and reconstruction of skin defect. J Egypt Natl Canc Inst. 2009;21(1):23–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirakawa H, Hasegawa Y, Hanai N, Ozawa T, Hyodo I, Suzuki M. Surgical site infection in clean-contaminated head and neck cancer surgery: risk factors and prognosis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2013;270:1115–1123. doi: 10.1007/s00405-012-2128-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jeannon JP, Orabi A, Manganaris A, Simo R. Methicillin Resistant Staphylococcus Aureus Infection as a causative agent of fistula formation following total laryngectomy for advanced head & neck cancer. Head Neck Oncol. 2010;2(1):1–5. doi: 10.1186/1758-3284-2-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study had already been included in this manuscript. Patient’s case file was retrieved from the medical record section of the institution. The clinical data had been collected from the prospectively maintained computerized database and the case file. The follow-up status was updated from the above-mentioned manner.