Abstract

The Neck is a cylindrical structure containing vital neurovascular and visceral structures tightly packed in a relatively small volume. Mortality rate increases when there is an injury to vascular structures especially the carotid artery, surrounded by other vital neurovascular structures; injuring the neck leads to devastating morbidity when compared to other injuries. With increased awareness of screening techniques and improved detection rates, there is an urge in opting for selective neck exploration and initial aggressive antithrombotic therapy for blunt carotid artery injuries. Here we report a case of a 20-year-old male, with a lacerated injury of the right side of the neck causing transection of the right internal jugular vein, grade 4 (Denver classification) blunt carotid injury, along with cervical vertebral fractures without neurological deficits. The patient underwent emergency surgical neck wound exploration, flush ligation of transacted Right Internal Jugular Vein, and conservative management for blunt carotid artery injury using anti platelets (Aspirin and Clopidogrel) avoiding any immediate neurological deficits. Whenever lacerated neck wounds are evaluated, the chance of blunt injury to the carotid is to be borne in mind and such an injury can be managed with double antiplatelet therapy, if there are no demonstrable neurological deficits.

Keywords: Neck injury, Ischemia, Internal carotid, Angiography, Anti-thrombotic therapy

Introduction

Penetrating Traumatic neck injuries account for 5–10% of all injuries with high morbidity and mortality [1].Traumatic neck injuries following road traffic accidents are common these days following rash driving and due to increased use of alcohol [2]. Penetrating neck injuries (PNI) are those causes’ deep injuries breaching Platysma. They have a mortality rate of 3–6%, with massive haemorrhage being the most common cause of death. Evaluation of vascular injury is mandatory in all neck trauma patients. Blunt injury of carotids without any neurological deficits is unexpected in most of the penetrating neck injury cases. The management of neck trauma has gradually evolved from non-selective neck exploration to selective surgery with the help of high resolution computed tomography [3]. Only a few case reports are published based on penetrating neck injuries with blunt trauma injury (BCI) to carotids where usually a foreign body is commonly breaching the integrity of the neck as well as carotid sheath [4]. In this report, we describe how we managed a case of hemodynamically stable open neck laceration injury with complete transection of right side IJV and complete thrombosis of the cervical part of right Internal Carotid Artery (ICA) presented to us without any neurological deficits.

Case Report

A 20-year-old male with an alleged history of the road traffic accident, under influence of alcohol, had a fall over an iron rod, presented with 12 * 5 * 2 cm laceration over the right side of the neck (involving zone 2 and 3) transecting the sternocleidomastoid muscle, exposing the great vessels and extending to the right parotid region with complete avulsion of ear lobule (Fig. 1a). There was no difficulty in breathing, swallowing, voice change or haemoptysis, visual disturbances, facial swelling, and pain.

Fig. 1.

a Penetrating neck injury over the right side of neck with avulsed and necrosed ear lobule, b Post neck exploration wound suturing with glove drain in situ

On examination, he was conscious, oriented, vitals were stable, and were not having any neurological deficits (moving all four limbs). Facial nerve examination revealed a slight deviation of angle of the mouth towards the left with normal right eye closure. The patient management started according to Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) protocol. Initial Non Contrast Computed Tomography (NCCT) head and spine showed a transverse bone fracture of Lamina, Transverse process & body of C2-C3 vertebra. He was put on a Philadelphia collar with strict neck immobilization. Doppler Ultrasound Neck showed minimal color flow in the right carotid artery and collapsed right IJV at and above the level of external wound. Contrast-Enhanced Computed Tomography (CECT) neck & Computed Tomography Angiography (CTA) were revealing a filling defect in right cervical internal carotid (grade 4, Denver classification) and internal jugular vein above the level of the wound with multiple air pockets in right parapharyngeal, carotid, masticator, and prevertebral space(Figs. 2, 3a, b). Vertebral arteries were normal with hangman fashioned fracture-dislocation of C2-C3 and fracture of the right first rib with subcutaneous emphysema. Intracranial part of right ICA and circle of Willis visualized were normal. Neurosurgery, Cardio Thoracic Vascular Surgery (CTVS) opinion sought, advised starting Aspirin 325 mg OD and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) brain with the spinal cord. MRI brain reported as C2 bilateral pedicle fracture with fracture fragment impinging the spinal cord at C2 level with increased T2 signal within the cord. On T1, hyper-intensity or gradient hypo-density suggested contusion (Fig. 4). Posterior longitudinal ligament disrupted at C2 with no other spine injuries. Right ICA shows no signal in Magnetic Resonance Angiography (MRA) s/o thrombosis. Videolaryngoscopic examination showed a right vocal palsy with phonatory gap.

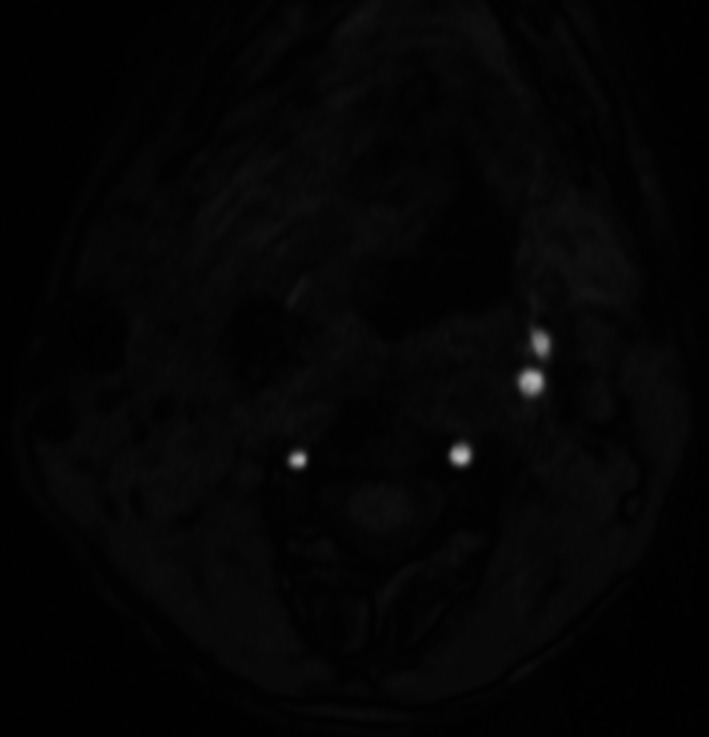

Fig. 2.

CTA axial view showing normal carotid enhancement on left side with absent enhancement on right side

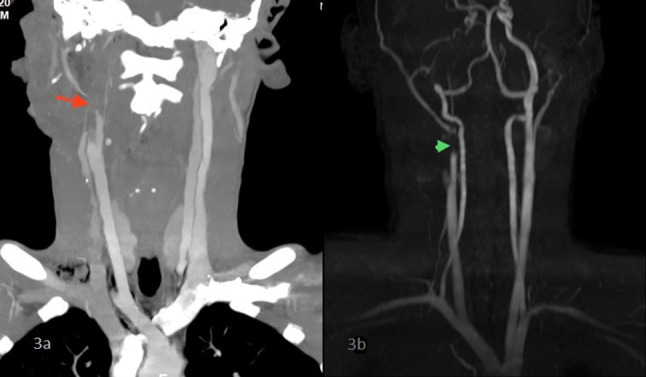

Fig. 3.

Coronal section neck showing carotid filling defect on right side in a CECT (orange arrow) and b CTA (green arrowhead)

Fig. 4.

MRI Neck sagittal section showing fracture of C2 (red arrow) and fracture of C3 (blue arrow)

The patient was empirically started on intravenous antibiotics Crystalline Penicillin, Ciprofloxacin, and metronidazole and taken up for emergency Neck exploration under General Anaesthesia(GA); intubated using video laryngoscopy applying MILS maneuver without extension of the neck. Intra-Operative Findings noted; right-sided lacerated neck wound with the breach in platysma muscle. Right Sternocleidomastoid muscle transected at the level of upper one third. The tail of the Parotid gland was exposed with friable parotid parenchyma noted. Black, avascular, necrotic ear lobule was noted. No obvious injury was noted to the laryngotracheal framework. Right IJV visualized as completely transected & an intramural thrombus noted. The proximal and distal end of the right IJV was identified and flush ligation was done using 2-0 silk. Right common, external, and internal carotid arteries (ICA) were thoroughly examined up to the base of the skull and found to have no discontinuity or laceration, but right ICA appeared less pulsatile (Fig. 5). After wound debridement and freshening of necrosed edges, a thorough wash was given and closed in two layers. Right necrotic lobule excised and pinna also sutured back; glove drain was kept (Fig. 1b). Ryle’s tube was inserted following surgery. No Limb weakness was noted following the surgery. Glove drain removed on Postoperative date (POD) 3. On follow up opinion: CTVS advised continuing anti platelets. The patient was discharged on POD 8 following suture removal with advice to continue T. Aspirin 75 mg OD & T. Clopidogrel 150 mg OD and regular monthly follow up in the CTVS department.

Fig. 5.

Intraoperative carotid bifurcation (black arrowhead) and internal carotid artery (yellow arrow head)

Discussion

Vascular injury following penetrating neck injury accounts for 25%, with a 50% mortality rate [1]. Surgeons have to follow an organised approach since the neck contains several neurovascular and visceral structures [4].Knowledge regarding neck anatomy is necessary as neglecting the hidden injuries associated with laryngotracheal /pharyngoesophageal complexes or major vascular structures like carotid and jugular or injury to the spinal cord and vertebral bodies cause major morbidity in the post-management period. Contradictory to our beliefs, the occurrence of vascular injuries associated with penetrating neck injuries are lower than expected [5]. Screening for relative prevalence of carotid artery injury in all neck trauma cases helps in the prevention and management of devastating ischemic stroke and death. Early identification of blunt cerebrovascular injury using CTA and treatment with antithrombotic therapy helps in minimizing the risk of stroke/ death.

Previously, all cases of neck trauma were considered as life-threatening and underwent mandatory neck exploration that showed high negative results in asymptomatic cases [6]. This signifies the need for a protocol and specific management of neck trauma cases. The neck is classified into three zones according to anatomical landmarks [7] (Table 1).

Table 1.

Zones of Neck with anatomical landmarks and contents

| Zones | Anatomical landmarks | Contains |

|---|---|---|

| Zone 1 | From the level of the clavicle and sternal notch to the level of the cricoid cartilage | Subclavian artery and vein, jugular vein, common carotid artery esophagus, thyroid, and trachea |

| Zone 2 | From the level of the cricoid cartilage to the angle of the mandible | The common carotid artery, internal and external carotid arteries, the lower half of the internal jugular vein, larynx, hypopharynx, and cranial nerves X, XI, and XII |

| Zone 3 | From the angle of the mandible to the base of the skull | Internal and External Carotid arteries, the upper part of the internal jugular vein, lateral pharynx, and cranial nerves VII, IX, X, XI, and XII |

Penetrating neck injuries involve multiple zones or the zone is difficult to characterise. Physical examination with appropriate imaging techniques helps us to identify the majority of the injuries and to manage the cases properly [5].

Zone 1 & 3 neck injury characteristically require selective neck exploration with the adjuncts of vascular imaging techniques and following aerodigestive endoscopy but in zone 2 injury,cases are usually taken for immediate neck exploration [4].

The carotid artery is accountable for sufficient blood supply to the brain; enough patency and blood flow through ICA are the fundamental features requiring for brain function and survival [2]. Bouthillier et al. classified the ICA into seven segments based on its anatomical course [8].

According to Lee et al. [2] surgical ligation of the external carotid artery is being done without any consequence to cerebral perfusion. But in contradictory, the ligation of the cervical segment of the internal carotid artery has more adverse effects even though it is devoid of any branches. But this classification is not much helpful in cases of luminal injuries as in cases of blunt trauma neck injuries.

Mechanism of Blunt Trauma Injury to Carotid Artery

Blunt injury to the extra cranial segment of the carotid artery can occur due to the following reasons (1) hyperextension, rotation, or flexion of the neck causing vessel stretching; (2) vertebral bony fracture causing vessel laceration; (3) direct impact over the carotid; (4) styloid process; (5) angle of the mandible during hyperflexion ( cervical segment runs medial to it) and (6) the lateral process of the cervical vertebral body during sudden rotation or compression movement [2, 9].

In our case, the Patient had an associated C2–C3 vertebral body hangman type of fracture along with right lateral process fracture. Intimal injury from the stretching of the vessels leads to dissection, intramural thrombus formation, and finally complete occlusion. Sometimes, degeneration of vessel wall upon stretch injury causes a hematoma formation, resulting in a pseudo aneurysm.

Etiology

The most common reported etiology of carotid injury is a motor vehicle accident, followed by assault and then hanging.

Denver proposed their classification system based on Luminal integrity [10, 11] (Table 2).

Table 2.

Denver classification Of blunt ICA injury

| Grade 1 | Luminal irregularity with less than 25% luminal narrowing |

| Grade 2 | Greater than 25% luminal narrowing, intraluminal thrombus or raised intimal flap, |

| Grade 3 | Pseudo aneurysm formation |

| Grade 4 | Luminal occlusion |

| Grade 5 | Vessel transaction |

This grading system also postulates effective prognosis in evaluating the risks of stroke & mortality. Our patient had a Grade 4 type of cervical part of internal carotid artery injury.

Great Vessels Injury

Presentation of blunt carotid artery injury may be asymptomatic (66–73%), stroke / TIA (33.7%), ipsilateral headache (58–92%), Horner syndrome (9–75%), neck pain (18–46%), bruit (12–49%) & tinnitus (13%). Even though most of the cases are asymptomatic at initial presentation, delayed neurological symptoms are noted anytime from 1 h to 30 days with a maximum of 7 days (82%) [12].

Investigations

Major imaging modalities for appropriate imaging and evaluation of blunt carotid artery injuries are CTA, MRA, Conventional Angiography, and Doppler Ultrasonography. But CTA is largely replaced DSA as a preliminary imaging modality because it is quick, reliable & easily accessible. MRA has the superiority of circumventing radiation exposure; considering it as more suitable in cases of trauma to children. Doppler ultrasonography has less sensitivity; however, it is advantageous in cases of follow up [10]. Most of the studies show CTA has high sensitivity and specificity compared to other modes of imaging techniques. CTA has shown high sensitivity and specificity for detecting all significant vascular and aerodigestive injuries [4]. Routine Angiography is contraindicated in patients with hypovolemic shock, airway obstruction and signs of vascular injury.

Treatment

Screening for relative prevalence of carotid artery injury among all neck trauma cases helps us in the prevention and management of developing devastating ischemic stroke and death [13].

Like all trauma cases, our patient management also started according to ATLS principles [14]. It includes an assessment of the airway and control of bleeding. Preliminary use of high-resolution CT scans with fine cuts helps in managing patients with a “no zones approach “ by easily classifying the patients into hemodynamically stable and unstable [4]. Hemodynamically unstable patients are taken up for immediate neck exploration. Stable patients are planned for high-definition fine cut CT angiogram. Based on the imaging and clinical findings; we can plan for the need for selective neck exploration.

The targets of management in blunt carotid artery injury with penetrating neck trauma comprises of stabilizing the circulatory shock, reducing the advancement of vessel injury, reducing the occurrence of ischemic incidents in asymptomatic patients, and improving overall neurologic and survival outcomes [1, 2].

Most of the physicians advocate for antithrombotic therapy alone in low-grade injuries; for high-grade endovascular injuries, prior or concurrent endovascular stenting is recommended.

Both heparin and antiplatelet therapies appear equally effective in minimizing the risk of stroke in asymptomatic patients and improving neurologic outcomes in symptomatic patients.

Even though the ability to reverse anticoagulation before any procedure is advantageous in the usage of heparin, a low risk of bleeding complications, relative ease of administration, and monitoring give an upper hand to antiplatelet therapy (325 mg aspirin daily or 75 mg clopidogrel daily).

As previous studies show low responsiveness of grade 3 and 4 injuries towards antithrombotic therapy, in general, there is growing wide acceptance of endovascular stenting treatment nowadays. Major indications for endovascular stent placement include (1) failed medical management (new ischemic event, the progression of initial symptoms, or enlarging pseudoaneurysm); (2) stroke; and (3) contraindications to anticoagulation. Previously a case report suggests similar conservative management in a stroke patient following blunt carotid injury [15].

Conclusion

Blunt trauma to carotids among PNI is an unusual presentation. The management of neck trauma has gradually evolved from non-selective neck exploration to selective ones with the help of high-resolution fine cuts CT. Our patient was extremely lucky as he narrowly escaped from devastating stroke and its related complications even though he has a big lacerated neck wound exposing to major vascular injuries. Anti-thrombotic agents should be considered in blunt carotid injuries when there are no contraindications. This will prevent the progression of vessel injury that occurs with observation alone.

Funding

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Olivo M (2019) Zone 2 neck impalement: a case report and review of management. 2(3):3

- 2.Lee TS, Ducic Y, Gordin E, Stroman D. Management of carotid artery trauma. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2014;7(3):175–189. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1372521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bell RB, Osborn T, Dierks EJ, Potter BE, Long WB. Management of penetrating neck injuries: a new paradigm for civilian trauma. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2007;65(4):691–705. doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ng E, Campbell I, Choong A, Kruger A, Walker PJ. Forty hours with a traumatic carotid transection: a diagnostic caveat and review of the contemporary management of penetrating neck trauma. Chin J Traumatol. 2018;21(2):118–121. doi: 10.1016/j.cjtee.2017.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thoma M, Navsaria PH, Edu S, Nicol AJ. Analysis of 203 patients with penetrating neck injuries. World J Surg. 2008;32(12):2716–2723. doi: 10.1007/s00268-008-9766-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Richard SA, Zhang CW, Wu C, Ting W, Xiaodong X. Traumatic penetrating neck injury with right common carotid artery dissection and stenosis effectively managed with stenting: a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Vasc Med. 2018;2018:1–9. doi: 10.1155/2018/4602743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roon AJ, Christensen N. Evaluation and treatment of penetrating cervical injuries. J Trauma. 1979;19(6):391–397. doi: 10.1097/00005373-197906000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouthillier A, van Loveren HR, Keller JT (1996) Segments of the internal carotid artery: a new classification. Neurosurgery 38(3):425–432; discussion 432–433. 10.1097/00006123-199603000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Zelenock GB, Kazmers A, Whitehouse WM, Graham LM, Erlandson EE, Cronenwett JL, Lindenauer SM, Stanley JC. Extracranial internal carotid artery dissections: noniatrogenic traumatic lesions. Arch Surg. 1982;117(4):425–432. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1982.01380280023006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rutman AM, Vranic JE, Mossa-Basha M. Imaging and management of blunt cerebrovascular injury. RadioGraphics. 2018;38(2):542–563. doi: 10.1148/rg.2018170140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts D, Chaubey V, Zygun D, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of computed tomographic angiography for blunt cerebrovascular injury detection in trauma patients a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2013;257:621–632. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318288c514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burlew CC, Biffl WL, Moore EE, Barnett CC, Johnson JL, Bensard DD. Blunt cerebrovascular injuries: redefining screening criteria in the era of non-invasive diagnosis. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2012;72(2):539. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e31824b6133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Am BIC. Asymptomatic carotid blunt cerebrovascular injury: a new screening criterion. ANZ J Surg. 2013;84(6):491–492. doi: 10.1111/ans.12314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ATLS Committee (2012) Committee on Trauma, American College of Surgeons. Advanced trauma life support. Student course manual. Chicago: American College of Surgeons

- 15.Rattan A, Kataria R, Kumar A, Azam Q. Blunt carotid injury with thrombotic occlusion: Is an intervention always required for best outcome? Trauma Case Rep. 2019 doi: 10.1016/j.tcr.2019.100263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]