Abstract

Pharyngeal lipoma of the upper aero-digestive system is extremely rare. It is typically benign, slow growing and symptoms would depend on its size and location. Surgical intervention is often needed especially for large tumour with impending airway obstruction. Here we present a case of potentially life threatening presentation of pharyngeal lipoma.

Keywords: Lipoma, Pharyngeal, Airway obstruction, Odynophagia, Tracheostomy

Introduction

Lipomas are composed of mature adipocytes which are well circumscribed and encapsulated within a thin fibrous capsule [1]. About 20% of lipomas occur in the head and neck region, however it is extremely rare to be found in the oropharynx or larynx. The incidence of pharyngeal/parapharyngeal tumour is said to be as low as 0.5% of all head and neck tumour and 80% of these tumours are benign with salivary gland pleomorphic adenoma being the most common [2]. Treatment is mainly surgical resection, however this can be challenging due to its location and nearby vital neurovascular structures [2].

Case Description

A 72 years old gentleman with underlying hypertension, presented with one-day history of odynophagia which started after allegedly ingesting fish bone. His symptom was made worse after he attempted to remove it using his finger.

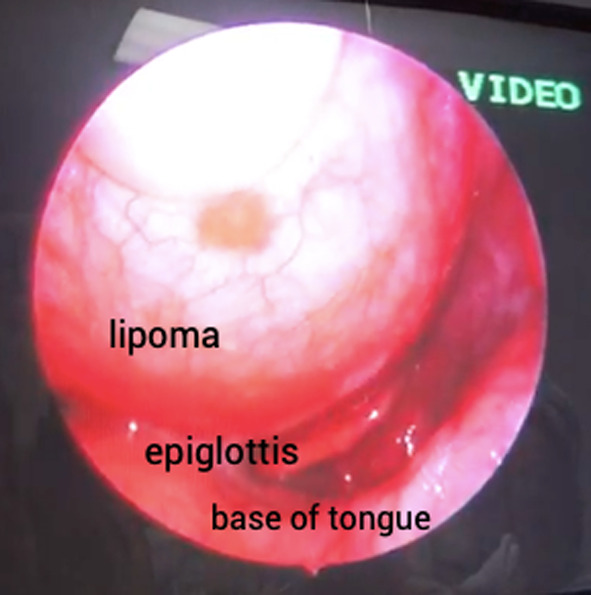

On examination, he was not stridorous and was comfortable under room air with no desaturation. His voice was muffled and there was a smooth bulging mass at the oropharynx. No external neck swelling was noted. Flexible nasopharyngolaryngoscopy showed a mass arising from the right lateral and posterior pharyngeal wall, occluding the laryngeal inlet (Fig. 1) and obstructing the view of the airway completely. No obvious foreign body was seen. As there was no prior clinical assessment of the mass and with a history of digital trauma by the patient himself, the concern was that the swelling was becoming oedematous and possibly enlarging. Anticipating an impending airway obstruction, a decision was made for an emergency awake fiberoptic intubation in the operating theatre which was uneventful.

Fig. 1.

Endoscopic image of right pharyngeal lipoma as seen on nasopharyngolaryngoscopy

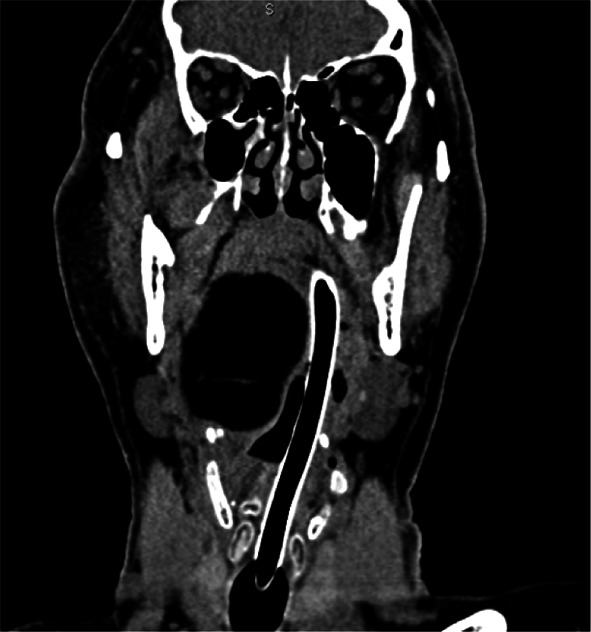

Subsequently, computed tomography (CT) imaging revealed a well-defined supraglottic encapsulated soft tissue lesion at the right parapharyngeal space measuring 4 × 5.7x7.5 cm (APxWxCC) with a predominant fat component,

which caused narrowing of the oropharynx and tracheal deviation to the left (Fig. 2 and Fig. 3). The mass did not involve the great vessels. No foreign body was seen on the scan. Due to the considerable waiting period at our clinical setting, no magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed.

Fig. 2.

Coronal view of the CT scan showing the mass displacing the airway

Fig. 3.

Axial view of the CT scan showing the mass with only the endotracheal tube maintaining the airway

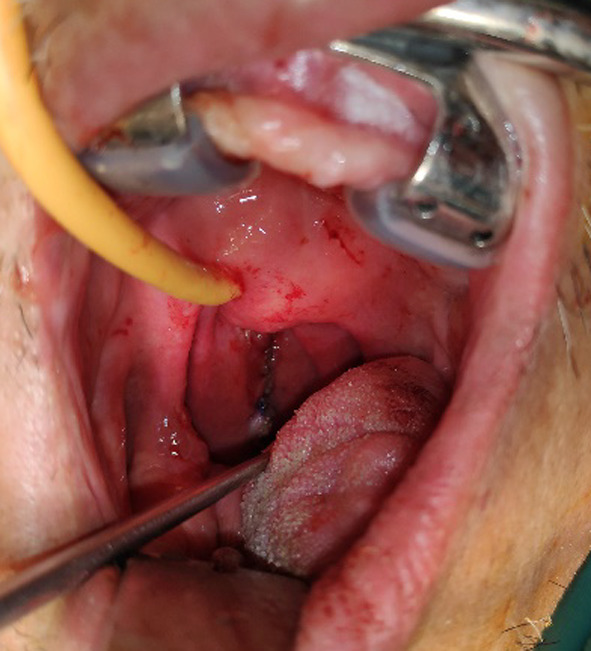

Tracheostomy, direct laryngoscopy and trans-oral tumour excision was subsequently performed. The mass was mostly confined to the oropharynx with no external extension, hence a trans-oral technique was chosen. Intraoperatively, there was a normal laryngeal inlet obstructed by the mass which extended from the level of the nasopharynx and down to the level of the epiglottis. Boyle-Davis mouth gag was then applied and held in place by Draffin’s bipod stand. A vertical incision made over the tumor which was submucosal and dissected along its plane via blunt dissection and removed in its entirety via the transoral route. The excised tumour was noted to be well encapsulated, soft in consistency and yellow in colour, measuring approximately 8 × 5 cm (Fig. 4 and 5). A nasogastric tube was then inserted for feeding purposes as patient was kept nil by mouth for the surgical site to heal. Due to the manipulation during surgery in removing the mass which was near the laryngeal inlet, a tracheostomy was performed in anticipation of post-operative laryngeal edema which may lead to airway obstruction. Patient’s recovery was uneventful and he was discharged 3 days after surgery. Histopathological examination reported this mass as simple lipoma with no malignancy features seen. During the outpatient clinic follow up 3 weeks post operatively, flexible nasopharyngolaryngoscopy showed a well healed surgical site. The nasogastric tube and tracheostomy tube were then removed. He was doing well on further follow up which was 3 months later and subsequently discharged from follow up.

Fig. 4.

Pharyngeal tumour specimen

Fig. 5.

Intra operative image showing the vertical intra-oral incision

Discussion

Oropharyngeal or pharyngeal space tumor may be of malignant or benign in nature. Eighty percent of them are benign and lipomas make up about 1–2% [2, 3]. Lipomas can be classified histologically into simple lipoma or its variants such as fibrolipoma, spindle cell lipoma, angiolipoma, myxolipomas, intramuscular/infiltrative lipoma, salivary gland lipoma, pleomorphic lipoma and atypical lipoma [4]. Intramuscular/infiltrating lipoma tend to have higher risk of recurrence if not completely incised as it usually infiltrates the surrounding skeletal muscle [5].

Despite its benign nature, pharyngeal lipoma can be fatal as it can potentially cause acute airway obstruction such as in the case mentioned above. An early diagnosis is a challenge as these benign masses do not usually cause any symptoms until the late stages. The ability to expand into the parapharyngeal space allows these tumours to grow to a large size before causing any symptoms [2, 6].

Presenting symptom depends on the location of the mass and its morphology i.e. sessile or pedunculated submucosal mass [7]. Some patients would complaint of dysphagia, change in voice, foreign body sensation, stridor, obstructive sleep apnea, snoring or even simply throat discomfort. In some cases, there has been reports of death secondary to pedunculated lipoma at the epiglottis, aryepiglottic fold or posterior cricoid causing laryngeal obstruction [7]. In our case, the patient’s presenting symptom of odynophagia post alleged fish bone ingestion pointed initially towards foreign body etiology, however further clinical examination revealed a different pathology.

Computed tomography (CT) or Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) in these situations are important not only for diagnostic purposes but also for pre-operative surgical and anesthetic planning [7]. Lipomas have typical distinctive characteristic features on CT: non enhancing, well delineated from surrounding structures with low attenuation between 65 and 125 Hounsfield unit (HU) [7]. While CT is usually the initial preferred imaging as it is quick and easily accessible, MRI is more useful in terms of assessing and delineating soft tissue extension of the tumour [3]. It can also be useful to differentiate lipoma from liposarcoma as it can potentially highlight presence of hemorrhage and necrosis or complete fat suppression and lack of nodule/septa which is suggestive of liposarcoma. However, MRI is time consuming with a longer waiting time as it is not usually readily available.

Pharyngeal lipomas, especially those interfering with breathing, speech and mastication need to undergo complete surgical resection [1–3]. The approach of surgery depend on the location, size, benign or malignant nature and tumour vascularity. There are few surgical approaches to pharyngeal/parapharyngeal tumours, mainly trans-oral or external approach like trans-cervical, trans-parotid, trans-mandibular or combination of these [8]. Transcervical transparotid approach is commonly employed for large pharyngeal tumour with prominent extension into the parapharyngeal space. It has the advantage of wider access with sufficient visualization of surgical field, especially to the lateral aspect of parapharyngeal space and provide adequate exposure of adjacent neural and vascular structures [2, 8].. However, this method comes with a greater risk of injury to the facial nerve, Frey’s syndrome and post operative visible external scar [2]. Other external approaches are transcervical via submandibular or infratemporal fossa [2]. On the other hand, trans–oral approach is usually preferred as it comes with lower postoperative morbidity with no unsightly external surgical scar and faster recovery rate [6]. This approach is usually employed for relatively smaller oropharyngeal mass and with less prominent or no parapharyngeal extension such as in our case above [2, 9]. The recurrence rate for these lipomas post excision is very low and many patients recovered well post operatively [1].

| Article | Authors | Journal and year of publication | Diagnosis | Surgical approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoral excision of huge retropharyngeal lipoma | Umit aydin et al | Brazilian journal of otolaryngology, 2020 | Huge retropharyngeal lipoma | Transoral approach |

| Giant parapharyngeal space lipoma extending to the pterygoid region (anterior skull base) | Arsheed H hakeem, et al | Journal of craniofacial surgery, 2018 | Giant parapharyngeal lipoma | Transverse cervical approach |

| Oropharyngeal lipoma; a rare and dangerous cause of voice change | Jessica lunn et al | British medical journal case report, 2019 | Oropharyngeal lipoma | Transoral approach |

| Retropharyngeal lipoma causing dysphagia | Javed akhtar et al | European archive of otorhinolaryngology, 2001 | Retropharyngeal lipoma | Transcervical approach |

Table of comparison of some oropharyngeal/parapharyngeal lipoma reported in other journals.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Bandéca MC, de Pádua JM, Nadalin MR, Ozório JE, Silva-Sousa YT, da Cruz PDE. Oral soft tissue lipomas: a case series. J Can Dent Assoc. 2007;73(5):431–434. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Infante-Cossio P, Gonzalez-Cardero E, Gonzalez-Perez LM, Leopoldo-Rodado M, Garcia-Perla A, Esteban F. Management of parapharyngeal giant pleomorphic adenoma. Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011;15(4):211–216. doi: 10.1007/s10006-011-0289-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McNeill EJ, Samuel PR. England S Lipoma of the parapharyngeal space. J Laryngol Otol. 2006;120(2):e9. doi: 10.1017/s0022215105009990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fregnani ER, Pires FR, Falzoni R, Lopes MA, Vargas PA. Lipomas of the oral cavity: clinical findings, histological classification and proliferative activity of 46 cases. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2003;32(1):49–53. doi: 10.1054/ijom.2002.0317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marion F, Videlaine A, Piot B, Merlet F-L, Longis J, Betin H. A giant parapharyngeal lipoma causing obstructive sleep apnea. J stomatol, oral maxillofac surg. 2019;120(6):595–597. doi: 10.1016/j.jormas.2018.12.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghammam M, Houas J, Bellakhdher M, & Abdelkefi M (2019). A huge retropharyngeal lipoma: a rare cause of dysphagia: a case report and literature review. The Pan African medical journal. 33, 12. 10.11604/pamj.2019.33.12.18541 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Tan KS, Jalaluddin W. Lipoma of vallecula-a case report. BJR Case Reports. 2016;2(3):20150460. doi: 10.1259/bjrcr.20150460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hakeem AH, Hakeem IH, Budharapu A, Wani FJ. Giant parapharyngeal space lipoma extending to the pterygoid region (Anterior skull base) J Craniofac Surg. 2018;29(2):e149–e150. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000004384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Aydin U, Karakoc O, Binar M, Arslan F, Gerek M. Intraoral excision of a huge retropharyngeal lipoma causing dysphagia and obstructive sleep apnea. Braz J Otorhinolaryngol. 2020;86(Suppl 1):8–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bjorl.2016.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]