Abstract

Paragangliomas of the head and neck can arise in many locations along the carotid sheath and middle ear. A hypervascular tumor in relation to the major cervical vessels can be either a carotid body tumor or vagal paraganglioma. Carotid bifurcation separation is a characteristic feature of carotid body tumours. We present a case of vagal paraganglioma of the neck, causing carotid bifurcation separation similar to that of a carotid body tumor. In this case report, we highlight the imaging features that can differentiate these two paragangliomas in such a confusing situation.

Keywords: Vagal paraganglioma, Carotid body tumor, Neck mass, Carotid space mass

Introduction

Paragangliomas are rare tumors arising from the Amine Precursor Uptake Decarboxylation (APUD) cells. They represent 0.5% of all head and neck tumors [1]. Carotid body and vagus nerve (X) are the most common head and neck paragangliomas [1]. Carotid body tumors (CBT) are three times more common than vagal paragangliomas (VP). Symptoms of nerve deficit are present in 30% of patients with VP and 2% of patients with CBT [2]. Both these tumors are hypervascular, and most of the time, they are easily differentiated on imaging using computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. CBT is located at carotid bifurcation and produce characteristic Lyre’s sign due to separation of carotid bifurcation. While VP are often located superiorly, involve jugular foramina, and do not produce Lyre’s sign. Sometimes large VP can reach up to the infrahyoid neck and cause separation of the carotid bifurcation. In such cases, differentiation between the two becomes difficult on imaging. Our case describes one such case of VP closely mimicking CBT.

Case Presentation

An 18-year male patient presented with complaints of painless neck swelling on the left side for six months. The swelling was bluish, freely mobile, soft, and pulsatile. No difficulty in breathing, swallowing, or speaking was present. A highly vascular elongated mass was seen on the left side on ultrasonography, causing splaying of carotid vessels. Based on this, a presumptive diagnosis of a carotid body tumor was made. His urine and blood metanephrine levels were normal. For further evaluation, a computed tomography angiography of the neck (CTA) was done. CTA revealed an elongated highly vascular and intensely enhancing carotid space mass reaching superiorly up to jugular foramen and causing anterior and medial displacement of carotid vessels with splaying of carotid bifurcation (Fig. 1a–f). Despite the separation of the carotid bifurcation, other features of mass favored a diagnosis of VP over a carotid body tumor. Digital subtraction angiography confirmed the hypervascular nature of the tumor and blood supply from branches of the external carotid artery (Fig. 2a, b). A preoperative embolization and clamping test were performed. Surgery was done using an extended left cervical incision. Vessel dissection was done without any complications. Separation of cranial nerves from the tumor was difficult within the tumor capsule. Left vagal nerve could not be separated from the tumor and was sacrificed while complete tumor removal. Dysphonia and difficulty in swallowing were present in a post-operative period, which improved gradually with the help of speech therapy and conservative management. Surgical and histological findings confirmed the preoperative diagnosis of VP.

Fig. 1.

a–d CT angiography (CTA) axial images from caudal to cranial sections. a Avidly enhancing mass (white arrow) in left carotid space between a common carotid artery (red arrow) and internal jugular vein (blue arrow) displacing common carotid artery anteriorly. b Mass was displacing carotid bifurcation anteriorly (yellow arrow). c Mass was insinuating between carotid vessels causing their separation (dashed yellow arrow). d Cranially mass was reaching up to left jugular foramen (black arrow). e, f Maximum intensity projection (MIP) and Volume rendered CTA coronal images respectively shows irregularly shaped mass, having a larger vertical diameter and causing mild splaying of the carotid bifurcation

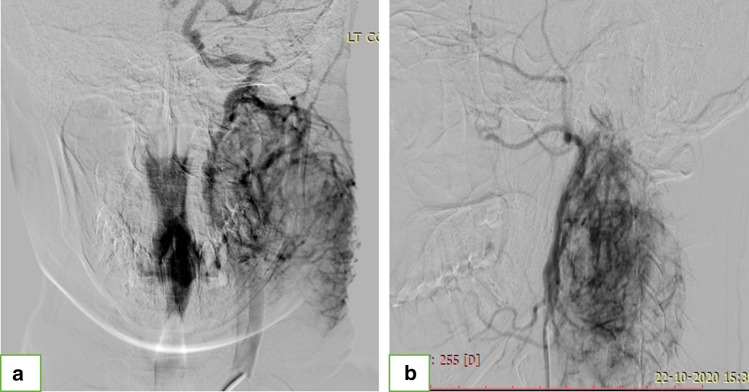

Fig. 2.

a, b Left common carotid and left external carotid artery (ECA) angiogram respectively shows marked tumor blush and blood supply from ECA

Discussion: The carotid space of the neck extends from the skull base to the aortic arch and traverses both the suprahyoid and infrahyoid neck. Differential diagnoses of lesions in this space are enlarged lymph nodes (present lateral to carotid and jugular vessels), mass arising from neural structures, and second brachial cleft cyst, which are usually cystic. Neurogenic mass in this space includes schwannoma/neurofibroma arising from cranial nerves or cervical sympathetic plexus, carotid body paraganglioma, and vagal paraganglioma [3]. Paraganglioma can be differentiated from other neurogenic masses by hypervascularity and intense post-contrast enhancement on cross-sectional imaging and salt-pepper appearance on MRI [3].

A carotid body tumor (CBT) is a paraganglioma that arises from glomus cells present at carotid bifurcation, and therefore they characteristically cause splaying of carotid bifurcation (Lyre’s sign) on imaging. Vagal paraganglioma (VP) of the neck arising from paraganglia along the vagal nerve is rare, comprising 5 to 11% of head and neck paraganglioma [4]. Imaging features that favor VP over CBT are anterior displacement of the internal carotid artery (ICA) without splaying the carotid bifurcation, involvement of jugular foramen, larger vertical diameter, and irregular shape (Fig. 3) [2]. Rarely splaying of carotid vessels may also be seen in VP, in such condition’s direction of vessel displacement and other features should also be considered for making a diagnosis. The direction of vessel displacement and involvement of jugular foramina combined has a diagnostic accuracy of 97% in identifying VP [4]. Thus, we can confidently differentiate VP from CBT on CTA or MRI using these imaging features on imaging.

Fig. 3.

Schematic diagram showing carotid body tumor a, b causing splaying of the carotid bifurcation and posterior displacement of carotid vessels. On the other hand, vagal paraganglioma c, d causes anterior displacement of carotid vessels with mild or no splaying of the carotid bifurcation. Vagal paraganglioma is also more elongated, irregular, and extends to the level of the jugular foramen (Red—carotid vessels; Blue- internal jugular vein; Brown—paraganglioma; Yellow—vagus nerve; Grey—jugular foramen)

Differentiating these two paragangliomas on imaging is essential from a surgical and prognostic point of view. Surgery of VP is challenging due to the involvement of multiple cranial nerves and skull base extension. Post-operative development of variable degrees of vagal nerve deficits is seen in almost all cases of VP [5, 6]. Therefore, therapeutic radiation is sometimes recommended for advanced VPs in elderly patients or patients with severe comorbidity, where there is a risk of significant swallowing or breathing or speech disorders [5]. In contrast, surgical resection is the treatment of choice for CBT where there is less risk of cranial nerve injury and more chances of vascular injury [5].

Conclusion

Vagal paraganglioma of the neck can rarely cause separation of the carotid bifurcation and closely mimic carotid body tumor. Anterior displacement of carotid vessels, elongated and irregular tumors reaching up to jugular foramen are the imaging features that help differentiate VP from CBT. There is a high risk of vagal nerve injury during surgery of VP, due to which radiation therapy is sometimes recommended for VP in high-risk cases. On the other hand, surgery is always preferred for CBT. Thus, preoperative differentiation of these two paragangliomas is essential for surgical treatment planning.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed sufficiently to the final version of manuscript.

Funding

No funding was received for this study.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from patient for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Priya Singh, Email: singhpriya2861990@gmail.com.

Surya Pratap Singh, Email: suryapratap10@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Singh S, Madan R, Singh M, Thakar A, Sharma S. Head-and-neck paragangliomas: An overview of 54 cases operated at a tertiary care center. South Asian J Cancer. 2019;08(04):237–240. doi: 10.4103/sajc.sajc_339_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zanoletti E, Mazzoni A. Vagal paraganglioma. Skull Base. 2006;16(03):161–167. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-949519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silver A, Mawad M, Hilal S, Ascherl G, Chynn K, Baredes S. Computed tomography of the carotid space and related cervical spaces. Part II: neurogenic tumors. Radiology. 1984;150(3):729–735. doi: 10.1148/radiology.150.3.6695075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wang X, Chen Y, Chen X, Xian J. Parapharyngeal space paraganglioma: distinguishing vagal paragangliomas from carotid body tumours using standard MRI. Clin Radiol. 2019;74(9):734.e1–734.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2019.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taïeb D, Kaliski A, Boedeker C, Martucci V, Fojo T, Adler J, et al. Current approaches and recent developments in the management of head and neck paragangliomas. Endocr Rev. 2014;35(5):795–819. doi: 10.1210/er.2014-1026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kotsis T, Christoforou P. Vagal paraganglioma: surgical removal with superior laryngeal nerve preservation. Vasc Spec Int. 2019;35(2):105–110. doi: 10.5758/vsi.2019.35.2.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.