Abstract

Goldenhar syndrome is a rare genetic condition characterized by hemifacial microsomia, mandibular hypoplasia, auricular malformations, and epibulbar dermoids. The syndrome has both sporadic and familial occurrence. Incidence of congenital hearing loss in these patients is 1:1000 in children with a male to female ratio of 3:2. In our case study we report a case of Goldenhar Syndrome who underwent cochlear implantation. The patient had right side microtia, right hemifacial microsomia and right side torticollis, pterygium in her right eye, right hypoplastic thumb and unilateral right side kidney. Radiologically, there was narrow duplicated internal auditory canal on right side with absent right cochlear nerve with normal anatomy on left side and the left side showed malformed facial nerve at tympani segment and second genu. Therefore, the patient was planned for left side cochlear implantation. Intraoperatively, there were malformed ossicles with anomalous facial nerve covering whole of oval window and partially the round window. Thus, a separate cochleostomy was done. Impedance was < 5 Hertz in all electrodes and electrically evoked action potential (ECAP) thresholds were obtained on all electrodes.

Keywords: Goldenhar syndrome, Cochlear implantation, Hemifacial microsmia, Anomalous facial nerve

Introduction

Goldenhar syndrome is a rare genetic condition characterized by hemifacial microsomia, mandibular hypoplasia, auricular malformations and epibulbar dermoids. It was first described by Maurice Goldenhar in 1952. In 1963, Gorlin coined the term “oculoauriculovertebral dysplasia” to describe patients who presented with these similar features along with vertebral anomalies. Goldenhar syndrome occurs in about 1 in 3500 live births [1]. Etiology of the syndrome is unknown. The syndrome occurs sporadically but familial inheritance with autosomal dominant and recessive pattern has also been described [1]. Many environmental factors are also responsible which include maternal teratogenic exposures (tamoxifen, thalidomide, cocaine, oral anticoagulants, vitamin A derivatives), alcohol abuse, viral infections, and gestational diabetes mellitus [2, 3]. Pathogenesis is complex and may be due to interference with vascular supply and focal hemorrhage in the developing first and second branchial arch region. It may also be due to impaired interaction of cranial neural crest cells with branchial arch mesenchyme [1].

Incidence of congenital hearing loss in these patients is 1:1000 in children with a male to female ratio of 3:2 [4].

The structural disorder in hearing organ includes various degrees of hypoplasia of the pinna (microtia, anotia) co-existing with the stenosis or absence (atresia) of the external auditory canal, preauricular outgrowths [1], hypoplasia of the tympanic membrane, hypoplasia of the tympanic cavity, hypoplasia and lack of auditory ossicles, improper course of the facial nerve, lack of tensor tympani muscle, lack of chorda tympani, lack of oval and round windows, cochlear hypoplasia, underdevelopment or lack of semicircular canals, enlargement of the vestibular aqueduct, and internal auditory canal defects [5, 6]. Due to these anomalies variable degree of hearing loss is found in this syndrome.

Here we report a case of Goldenhar Syndrome with congenital hearing loss and multiple ear anomlaies who underwent cochlear implantation.

Case

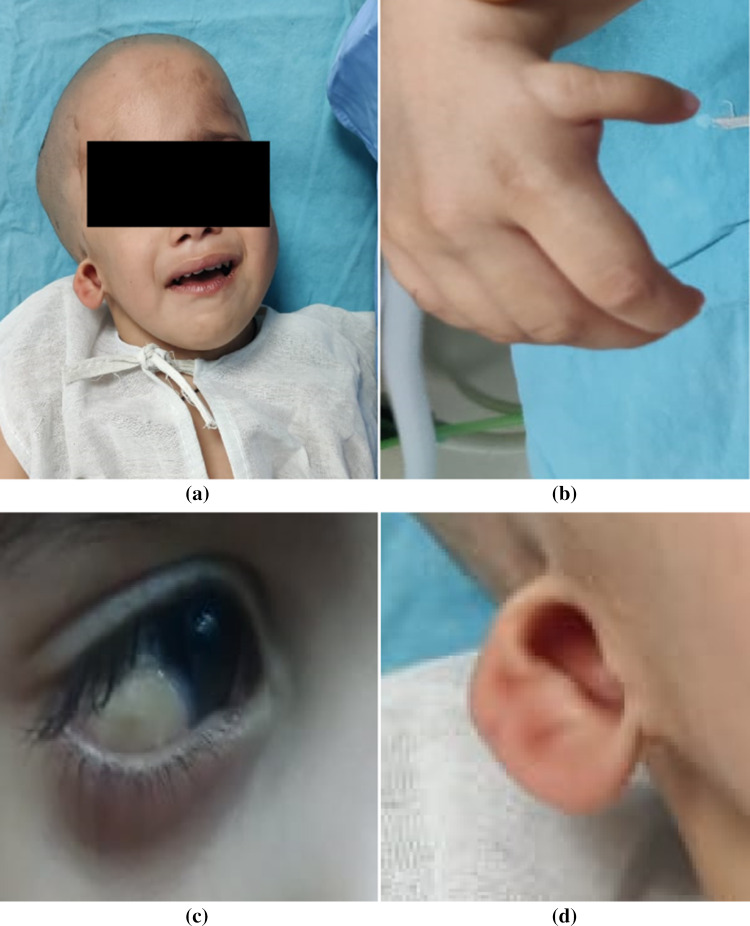

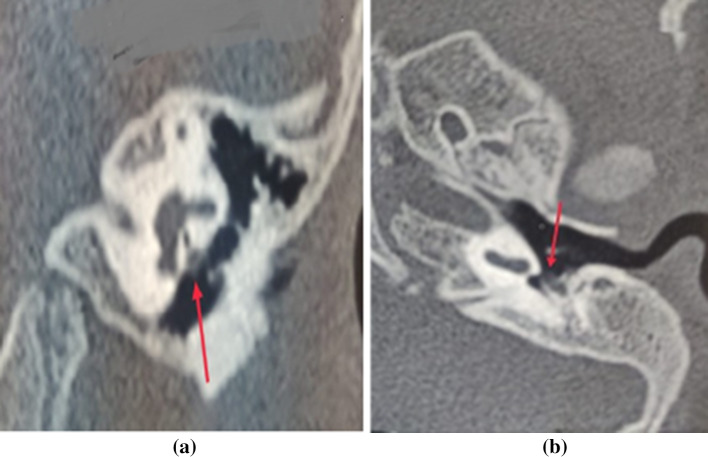

A two-year-old female child presented to ENT department of SMS Medical College, Jaipur, India with chief complaints of congenital hearing loss and speech delay. Patient also had right side microtia, right hemifacial microsomia and right side torticollis. She also had pterygium in her right eye, right hypoplastic thumb and unilateral right side kidney (Fig. 1a–d). On otoscopy, right side external ear couldn’t be examined due to stenosed external auditory canal while the left side was normal. Audiological assessment was done. On Brainstem Evoked Response Audiometery, Vth peak was not traceable even at 100 dB in both ears on both air and bone conduction. Otoacoustic Emission showed bilateral non-functional outer hair cells that is “refer" type. Tympanometry was As type on left side with absent stapedial reflexes in both ears. High resolution computed tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging of temporal bones showed narrow duplicated internal auditory canal on right side with absent right cochlear nerve with normal cochlear anatomy on left side, however the left side showed malformed facial nerve at tympani segment and second genu (Fig. 2a, b). On hearing aid trial, no improvement was there. Therefore,the patient was planned for left side cochlear implantation.

Fig. 1.

Clinical features of Goldenhar syndrome a. Hemifacial microsomia and right side torticollis b. Right hypolplastic thumb c. Right side pterygium d. Right side microtia

Fig. 2.

High resolution computed tomography of left side temporal bone a. Anomalous facial nerve covering oval window (red arrow) b. Anomalous facial nerve covering round window (red arrow)

Anesthetic clearance was taken. Surgery was done by transmastoid facial recess approach. There was glue in the middle ear cleft which was suctioned out. Malleus and incus were present as a single entity, which was connected to stapes head via a fibrous band. Stapes footplate and crura were absent. Facial nerve had anomalous course lying over promontory anteriorly and inferiorly covering whole of the oval window along with most of round window. Round window was barely visible and was confirmed through refraction by putting a drop of saline in posterior part of middle ear cleft just inferior to anomalous facial nerve. A separate anteroinferior cochleostomy was done (Fig. 3). Finally, Contour Advance implant of Cochlear Ltd was placed in the well and electrodes inserted through cochleostomy site in the scala tympani of cochlea. Flap was repositioned and wound closed in layers. Intraoperatively, impedance was < 5 Hertz in all electrodes and ECAP thresholds were obtained on all electrodes.

Fig. 3.

Intraoperative findings depicting posterior tympanotomy and malformed ossicles with abnormal facial nerve course and separate cochleostomy. Anomalous facial nerve covering the round window (yellow arrow). Malformed ossicles showing stapes head connected to incudomalleal complex via a fibrous band (black arrow). Separate anteroinferior cochleostomy over the promontory (blue arrow)

Discussion

Hearing loss is generally conductive type in patients with Goldenhar syndrome and is mainly due to developmental disorders of the hearing apparatus originating from the first and second pharyngeal arch [7, 8] i.e. external and middle ear. If structural deformity includes inner ear, then sensorineural hearing loss also coexists but this type of hypoacusis is less common [8–10]. Therefore, during evaluation bone conduction Auditory Brainstem Response should be done in all patients to rule out conductive hearing loss. A theory has been hypothesized that mandibular deformity and ossicular malformations are the result of developmental perturbation to the Meckel’s and Reichart’s cartilage [11]. Due to these developmental disturbances, secondary abnormalities of the facial skeleton, masticatory system and temporal bone develop [12, 13]. Since the intratemporal course of the facial nerve depends upon on the normal development of bony structures derived from the Reichart’s cartilage, ossicular malformations present in this syndrome predisposes facial nerve course to be more anteroinferior in its tympanomastoid part thus leading to more direct route to facial muscles [14]. There are disturbances in neural crest cell migration which could be the possible explanation behind the sensorineural hearing loss which cannot be explained by the concept of defective branchial development [15].

Castellino et al. in their case report on posterior semi-circular canal electrode misplacement in Goldenhar Syndrome also mentioned malformed (anteriorly displaced) facial recess and malformed ossicles, which was similar to our patient. They had a misplaced electrode array into the semicircular canal, which required a revision surgery. This should always be kept in mind when dealing with such patients with very few reliable landmarks [16].

Skarżyńskiet al in 2009 in their study on treatment of otological features in oculoauriculovertebral dysplasia (Goldenhar Syndrome) had described the cochlear implantation in two patients with OAVD and bilateral deep sensorineural hearing loss [17]. One of them had adefective structural anatomy of the inner ear while the other had normal anatomy of the inner ear.

MacArdle in 2002 [18] in their study on cochlear implantation in craniofacial anomalies described one case of Goldenhar Syndrome amongst four cases. Cochlear implantation was done and full electrode insertion was successfully achieved.

Umashankar et al. in 2019 [19] documented a report on cochlear implantation in a two year old child with Goldenhar Syndrome where they had assessed its outcome also.

There are various treatment modalities for hearing loss in these patients.When the hearing loss is mainly due to atretic external auditory canal, treatment of choice is mainly bone-anchored implants instead of only reconstruction of auditory canal. Ossiculoplasty can be considered as one option if hearing loss is due to malformed ear ossicles [20]. In cases with hearing loss due to serous otitis media, exploratory tympanotomy and insertion of ventilation tubes can help [20, 21]. In cases where sensorineural hearing loss is present, cochlear implant or brainstem implant are better alternatives [20].

Conclusion

Cochlear implantation can be considered as one option for improving hearing of patients with Goldenhar Syndrome. During the surgery, correct identification of surgical landmarks is of utmost importance for electrode insertion. Therefore, a thorough study of pre-operative imaging and meticulous dissection becomes essential in this case. Other treatment modalities should also kept in mind as the syndrome includes complex external and middle ear defects. In-depth analysis is required in these cases as to decide proper line of management.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Andrews TM, Shott SR. Laryngeal manifestations of goldenhar syndrome. Am J Otol. 1992;13:312–315. doi: 10.1016/0196-0709(92)90055-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cullins SL, Pridjian G, Sutherland CM. Goldenhar’s syndrome associated with tamoxifen given to the mother during gestation. JAMA. 1994;271:1905–1906. doi: 10.1001/jama.1994.03510480029019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lessick M, Vasa J, Israel R. Severe manifestations of oculoauriculovertebralspectrum in a cocaine-exposed infant. J Med Genet. 1991;28:803–804. doi: 10.1136/jmg.28.11.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tuna EB, Orino D, Ogawa K, Yildirim M, Seymen F, Gencay K, et al. Craniofacial and dental characteristics of Goldenhar Syndrome: A report of two cases. J Oral Sci. 2011;53:121–124. doi: 10.2334/josnusd.53.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bisdas S, Lenarz M, Lenarz T, Becker H. Inner ear abnormalities in patients with goldenhar syndrome. OtolNeurotol. 2005;26(3):398–404. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000169796.83695.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Phelps PD, Lloyd GA, Poswillo DE. The ear deformities in craniofacial microsomia and oculo-auriculo-vertebral dysplasia. J LaryngolOtol. 1983;97(11):995–1005. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100095888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carvalho GJ, Song CS, Vargervik K, Lalwani AK. Auditory andfacial nerve dysfunction in patients with hemifacialmicrosomia. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125(2):209–12. doi: 10.1001/archotol.125.2.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sleifer P, GorskyNdeS Goetze TB, Rosa RF, Zen PR. Audiologicalfindings in patients with oculo-auriculo-vertebral spectrum. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;19(1):5–9. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1390137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yanagihara N, Yanagihara H, Kabasawa I. Goldenhar’s syndromeassociated with anomalous internal auditory meatus. J LaryngolOtol. 1979;93(12):1217–1222. doi: 10.1017/S0022215100088320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scholtz AW, Fish JH, Kammen-Jolly K, Ichiki H, Hussl B, KreczyA Schrott-Fischer A. Goldenhar’s syndrome: congenital hearingdeficit of conductive or sensorineural origin temporal bone histopathologyicstudy. Otol Neurotol. 2001;22:501–5. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200107000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Caldarelli DD, Hutchinson JG, Pruzansky S, Valvassori GE. A comparison of microtia and temporal bone anomalies in hemifacial microsomia and mandibulofacial dysostosis. Cleft Palate J. 1980;17(2):103–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cousley RRJ, Calvert ML. Current concepts in the understandingand management of hemifacial microsomia. Br J Plast Surg. 1997 doi: 10.1016/S0007-1226(97)91303-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grabb WC. The first and second branchial arch syndrome. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1965;36:485–508. doi: 10.1097/00006534-196511000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durcan DJ, Shea JJ, Sleeckx JP. Bifurcation of the facialnerve. Arch Otolaryngol. 1967 doi: 10.1001/archotol.1967.00760050621005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Meter TD, Weaver DD. Oculo-auriculo-vertebral spectrumand the CHARGE association: clinical evidence for acommon pathogenetic mechanism. Clin Dysmorphol. 1996;5(3):187–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Castellino A, Rayamajhi P, Kurkure R, Kameswaran M. Posterior semi-circular canal electrode misplacement in Goldenhar’s syndrome. Cochlear Implants Int. 2020 doi: 10.1080/14670100.2020.1802905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skarzyński H, Porowski M, Podskarbi-Fayette R. Treatment ofotological features of the oculoauriculovertebral dysplasia (Goldenharsyndrome) Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73(7):915–921. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacArdle BM, Bailey CM, Phelps PD, Bradley J, Brown T, Wheeler A. Cochlear implants in children with craniofacial syndromes: Assessment and outcomes: Implantescoclearesenniños con síndromescraneofaciales: evaluación y resultados. Int J Audiol. 2002;41(6):347–356. doi: 10.3109/14992020209090409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Umashankar A, Jayachandran D. Measurement of cochlear implant outcomes in goldenhar syndrome: a case report. Indian J Case Reports. 2019;5(5):448–450. doi: 10.32677/IJCR.2019.v05.i05.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bouhabel S, Arcand P, Saliba I. Congenital aural atresia boneanchoredhearing aid vs. external auditory canal reconstruction. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2012;76(2):272–277. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santarelli G, Redfern RE, Benson AG. Bone-anchored hearing aidimplantation in a patient with goldenhar syndrome. Ear Nose Throat J. 2015;94(12):E1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]