Abstract

Tonsillectomy is one of the most common surgical procedures performed by otolaryngologists. Postoperative complications, although rare, can be observed in tonsillectomy. This study aimed to investigate the effect of anterior and posterior pillar suturing on dysphagia, hemorrhage, and pain complications following tonsillectomy in adult patients. The study included 80 patients (32 males, 48 females; > 18 years) who underwent tonsillectomy. The patients were divided into two groups: Group 1, in which the tonsillar lodge was closed by anterior–posterior pillar suturing with a 3–0 chromic catgut suture after hemostatic compression and Group 2, in which the tonsillar lodge was exposed following hemostatic compression and bipolar cauterization. Post-surgical pain was assessed using the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS). Oropharyngeal dysphagia was evaluated using the Eating Assessment Tool (EAT)-10. None of the patients experienced postoperative primary hemorrhage. However, postoperative secondary hemorrhage was observed in seven patients, two from Group 1 and five from Group 2. There was no significant difference in postoperative hemorrhage between the two groups (p = 0.449). Furthermore, no statistically significant difference was observed between the two groups in terms of the NRS scores on postoperative day 1 and at postoperative week 2 (p = 0.130 and 0.142, respectively) or the EAT-10 scores at postoperative week 2 and postoperative month 6 (p = 0.925 and 0.090, respectively). Anterior–posterior pillar suturing, which is performed for hemorrhage control after tonsillectomy, is not superior to the conventional bipolar method in terms of postoperative dysphagia, hemorrhage, and pain.

Keywords: Adult tonsillectomy, Pillar suturing, Pain, Dysphagia, Hemorrhage

Introduction

Tonsillectomy is one of the most common surgical procedures performed by otolaryngologists [1]. Postoperative complications, although rare, can be observed in tonsillectomy, with the common examples being hemorrhage, pain, dehydration, velopharyngeal insufficiency, obstructive pulmonary edema, and nasopharyngeal stenosis [2]. Hemorrhage is the most important and dangerous complication; therefore, there are many studies on safe and bloodless techniques in the literature.

Post-tonsillectomy pain is considered to be due to nerve irritation, inflammation, and pharyngeal muscle spasm [3]. Post-tonsillectomy pain lasts for approximately two weeks and may delay the patient’s start of normal activity and diet. In addition, it increases the patient’s risk of dehydration. Severe postoperative pain can result in delayed discharge, emergency room admission, or readmission for hydration [4]. Although postoperative oropharyngeal dysphagia is a common complication after tonsillectomy, it usually occurs secondary to pain during swallowing and mostly resolves after postoperative day 10 [5].

This study aimed to investigate the effects of anterior–posterior pillar suturing on dysphagia, hemorrhage, and pain complications in adults who underwent tonsillectomy.

Methods

After receiving local ethics committee approval numbered 2020/16, this retrospective study was conducted with individuals over 18 years who underwent tonsillectomy between January 1, 2015 and January 1, 2019. Patients with bleeding disorders and active infections were not included in the study.

All operations were performed by the same surgeon (SMA). Patients who underwent anterior posterior pillar suturing were randomly selected by the surgeon. In all the patients, both tonsils were medialized with clamps, and the anterior pillar was incised with a number 15 scalpel blade. The tonsil capsule was dissected from the surrounding pharyngeal muscles and the posterior pillar and removed with a snare. Group 1 (Fig. 1) comprised patients whose tonsillar lodge was closed by suturing the anterior and posterior pillars with a 3–0, 26 G chromic catgut suture (Covidien Polysorb™ Braided Absorbable Suture) following hemostatic compression, and Group 2 consisted of those who underwent hemostatic compression and bipolar cauterization before their tonsillar lodges were exposed. The low-energy bipolar cautery technique of 25 watts was used to reduce heat trauma to the tonsillar bed and associated postoperative pain.

Fig. 1.

Image of a patient whose tonsillar region was closed by suturing the anterior and posterior pillars

In all the patients, oral food intake was initiated at postoperative hour 4, and they were hospitalized for at least 24 h postoperatively. At the time of discharge, oral amoxicillin/clavulanate 1000 mg and paracetamol 500 mg were prescribed as two tablets per day, and the patients with postoperative hemorrhage were recorded.

Post-tonsillectomy pain was assessed using the Numeric Rating Scale (NRS) [6]. The patients were directed the question “how much are you disturbed by pain at the moment?” and asked to give a score between 0 and 10, where 0 represents no pain and 10 represents unbearable pain. The NRS scores of the patients were evaluated on postoperative day 1 and at postoperative week 2.

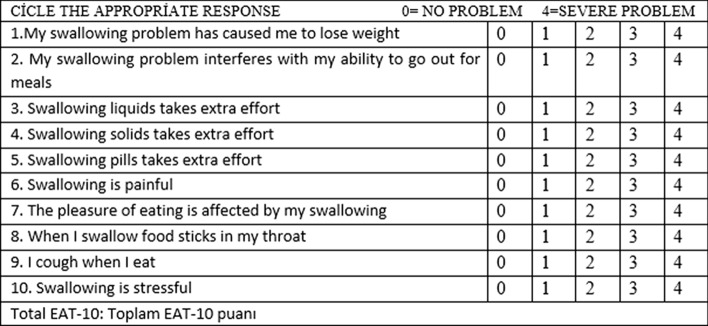

In the postoperative period, oropharyngeal dysphagia was evaluated using the Eating Assessment Tool (EAT)-10, which contains 10 items [7] (Fig. 2). Each item is scored between 0 and 4, with 0 representing no problem and 4 representing severe problems. The total score varies between 0 and 40. A score of 3 or more on the scale is considered abnormal. The EAT-10 scores of all the patients included in the study were evaluated at postoperative week 2 and postoperative month 6.

Fig. 2.

Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10) scores of the study groups

Statistical Analysis

SPSS software v. 20 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Data were expressed as mean, standard deviation, and percentage (%). The Shapiro–Wilk test was used assess the normality of the data. The chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests were used to compare categorical data between the groups. The Mann–Whitney U and Wilcoxon tests were used for non-parametric variables. Student’s t-test and paired-samples t-test were used for parametric variables. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Eighty adult patients who underwent tonsillectomy were included in the study. The mean age of the 80 operated patients was 34.56 (18–69) years. Of the 80 patients, 38 were male and 42 were female. Of these patients, 53 had chronic tonsillitis, 11 were suspected to have a tumor, 13 had obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, and three had halitosis.

There were 36 patients in Group 1 and 44 in Group 2. There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of age and gender (p = 0.537 and 0,658, respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Distribution of the patients in both groups according to gender and age (p = 0.658)

| Surgical technique | General average | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | |||

| Average age | 33.56 | 35.51 | 34.56 | 0.537 |

| Surgical technique | Total | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 | Group 2 | |||

| Gender | ||||

|

Man Woman |

16 20 |

22 22 |

38 42 |

0.658 |

| Total patient | 36 | 44 | 80 | |

Tonsillectomy was performed in five patients in group 1 and in six patients in group 2 due to tumor suspicion. There was no statistical difference between the two groups who underwent tonsillectomy due to suspected tumor (p = 0.464).

Primary postoperative hemorrhage was not observed in any of the 80 adults who underwent tonsillectomy. However, secondary postoperative hemorrhage developed in seven patients, two from Group 1 and five from Group 2. There was no significant difference between the two groups in relation to postoperative hemorrhage (p = 0.449) (Table 2). There was also no statistically significant differences in the NRS scores of two groups on postoperative day 1 and at postoperative week 2 (p = 0.130 and 0.142, respectively) (Table 3). The mean NRS score of all the patients was 6.0750 on postoperative day 1 and 2.0375 at postoperative week 2.

Table 2.

Distribution of the groups with and without anterior–posterior pillar suturing according to postoperative hemorrhage (p = 0.449)

| Postoperatıve bleedıng | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | ||

| Surgıcal technıque | |||

| Group 1 | 2 | 34 | 36 |

| 5.6% | 94.4% | 100% | |

| Group 2 | 5 | 39 | 44 |

| 11.4% | 86.6% | %100 | |

| Total | 7 | 73 | 80 |

| 8.8% | 91.3% | 100% | |

Table 3.

Postoperative NRS score of both groups

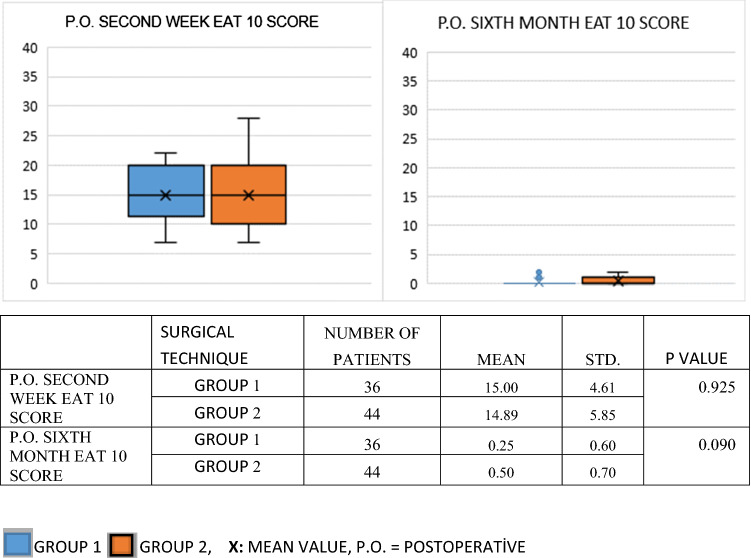

There was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of the EAT-10 scores of the patients at postoperative week 2 and postoperative month 6 (p = 0.925 and 0.090, respectively) (Table 4). The mean EAT-10 score of all the patients was 14.94 at postoperative week 2 and less than 3 (mean, 0.3875) at postoperative month 6.

Table 4.

Postoperative EAT-10 questionnaire score of both groups

Discussion

Post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage is a severe complication that can be life-threatening [8]. It may sometimes require intervention under general anesthesia in operating room conditions [9]. This complication is divided into two groups: primary post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage, which occurs within the first 24 h postoperatively and secondary post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage that occurs later, often between seven and 10 days postoperatively [10, 11]. Although the risk of primary hemorrhage is high, secondary hemorrhage can also be life-threatening, albeit rare.

In a study by Blakley based on the literature data for post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage, the maximum acceptable post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage rate was reported as 13.9% [12]. Primary post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage was reported to occur at a rate of 0.2–5.2% in various studies; however, the incidence of secondary hemorrhage was ranged from 1 to 10% [13]. Various studies have suggested that age is an important risk factor of post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage, with older patients having a higher risk of this complication [14–16]. Some studies have determined the post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage rate to be 8.6–10% in adults [17, 18]. Similarly, in our study, the post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage rate was 8.8%, and all hemorrhages was secondary post-tonsillectomy bleeding.

In the literature, risk factors, such as gender, surgical technique, skill level of the surgeon, and indication for tonsillectomy have been analyzed for post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage [15]. It is considered that suspicion of a tumor may have a greater effect on post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage. In our study, postoperative bleeding was not observed in any of the 11 patients who underwent surgery with tumor suspicion.

Gonçalves et al. reported that the advanced age of the patient increased the risk of post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage and the coagulation profile of the patient and adenoidectomy accompanying the surgery were predictive factors of post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage [19]. However, the authors stated that the post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage rate was not affected by the hemostasis method used (bipolar electrocoagulation or hemostasis with suture). In our study, although there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of postoperative hemorrhage, we observed that pillar suturing slightly reduced the rate of postoperative hemorrhages.

Postoperative pain is very common and may increase the risk of secondary infection, hemorrhage, and dehydration by impairing swallowing. Therefore, pain after tonsillectomy should be reduced. Various surgical and pharmacological strategies have been used to reduce this problem [20, 21]. Cokkeser et al. reported that suturing of the tonsillar pillars decreased postoperative pain and closure of the tonsillar fossa might facilitate early recovery; as a result, normal nutrition and scar healing could be achieved much earlier [22]. In our study, there was no significant difference between the postoperative week 2 and month 6 NRS scores of the two groups.

Dysphagia typically occurs secondary to postoperative pain and can continue for up to postoperative day 10. Long-lasting dysphagia may develop to glossopharyngeal nerve damage [23, 24]. This may be caused by intraoperative damage to the glossopharyngeal nerve due to its proximity to the tonsillar fossa and the anatomic variations in this region. The literature contains several questionnaires to evaluate dysphagia, with the most common being EAT-10, which contains 10 questions. The validity and reliability analyses of the Turkish version of EAT-10 were previously undertaken [25, 26]. EAT-10 was developed by a multidisciplinary team and has very high internal consistency and reliability [7]. In our study, there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of the EAT-10 scores at postoperative week 2 and postoperative month 6 (p = 0.925 and p = 0.090, respectively).

Pillar suturing is a method that has been adopted by surgeons for a long time to control troublesome bleeding, but it is not recommended as a routine procedure. As a novel finding, our study showed whether anterior posterior plica suturing had an effect on postoperative pain and dysphagia.

Our study has certain limitations that need to be addressed. First concerns the small number of participants. Second, environment factors (such as climate condition, temperature and humidity status) and individual differences in pain sensitivity may have affected our findings. Further prospective studies with a larger number of patients are required for the validation of our results.

Conclusion

Pillar suturing performed for post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage control is not superior to the conventional bipolar method in terms of postoperative dysphagia, hemorrhage, and pain.

Funding

None.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. There is no financial interest to disclose.

Ethics Approval

This study was performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval was granted by the Ethics Committee of Bülent Ecevit University (Date: 08.05.2020/Number: 16).

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all the individual participants included in the study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mehmet Ali Say, Email: malisay@msn.com.

Ergin Bilgin, Email: erginbilgin67@hotmail.com.

Deniz Baklacı, Email: doktorent@gmail.com.

References

- 1.Ostvoll E, Sunnergren O, Ericsson E, Hemlin C, Hultcrantz E, Odhagen E, et al. Mortality after tonsil surgery, a population study, covering eight years and 82,527 operations in Sweden. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;272(3):737–743. doi: 10.1007/s00405-014-3312-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitchell RB, Archer SM, Ishman SL, Rosenfeld RM, Coles S, Finestone SA, et al. Clinical practice guideline: tonsillectomy in children (update) Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2019;160(1):S1–42. doi: 10.1177/0194599818801757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Robinson SR, Purdie GL. Reducing post-tonsillectomy pain with cryoanalgesia: A randomized controlled trial. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:1128–1131. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200007000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pynnonen M, Brinkmeier JV, Thorne MC, Chong LY, Burton MJ (2017) Coblation versus other surgical techniques for tonsillectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 8:CD004619. 10.1002/14651858.CD004619.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Garnett JD, Ramadan HH (1996) Swallowing dysfunction after tonsillectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 114:813–817. 10.1016/S0194-59989670108-0 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Karcioglu O, Topacoglu H, Dikme O, Dikme O. A systematic review of the pain scales in adults: Which to use? Am J Emerg Med. 2018;36(4):707–714. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2018.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belafsky PC, Mouadeb DA. Rees CJ, Pryor JC, Postma N, Allen J et al (2008) Validity and reliability of the Eating Assessment Tool (EAT10). Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 117(12): 919–924. 10.1177/000348940811701210 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Goldman JL, Baugh RF, Davies L, Skinner ML, Stachler RJ, Brereton J et al (2013) Mortality and major morbidity after tonsillectomy. Laryngoscope 123:2544–2553. 10.1002/lary.23926 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Wei J, Beatty C, Gustafon R (2000) Evaluation of posttonsillectomy hemorrhage and risk factors. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 229–235. 10.1067/mhn.2000.107454 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Windfuhr JP. Lethal post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2003;30(4):391–396. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Randall DA, Hoffer ME. Complications of tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1998;118(1):61–68. doi: 10.1016/s0194-5998(98)70376-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blakley BW. Post-tonsillectomy bleeding: how much is too much? Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140(3):228–290. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ikoma R, Sakane S, Niwa K, Kanetaka S, Kawano T, Oridate N (2014) Risk factors for post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage. Auris Nasus Larynx 41:376–379. 10.1016/j.anl.2014.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Aljabr IK, Hassan FM, Alyahya KA (2016) Post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage after bipolar diathermy versus cold dissection surgical techniques in Alahsa region. Alexandria J Med 52:169–172. 10.1016/j.ajme.2015.06.004

- 15.Windfuhr JP, Chen YS, Remmert S (2005) Hemorrhage following tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy in 15,218 patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 132:281–286. 10.1016/j.otohns.2004.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Tomkinson A, Harrison W, Owens D, Harris S, McClure V, Temple M (2011) Risk factors for postoperative hemorrhage following tonsillectomy. Laryngoscope 121:279–288. 10.1002/lary.21242 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.J Mueller, D Boeger, J Buentzel, D Esser, K Hoffmann, P Jecker et al (2015) Population-based analysis of tonsil surgery and postoperative hemorrhage. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 272:3769–3777 10.1007/s00405-014-3431-6 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Schrock A, Send T, Heukamp L, Gerstner AO, Bootz F, Jakob M (2009) The role of histology and other risk factors for post-tonsillectomy haemorrhage. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 266:1983–1987. 10.1007/s00405-009-0958-z [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Gonçalves AI, Rato C, de Vilhena D, Duarte D, Lopes G, Trigueiros N (2020) Evaluation of post-tonsillectomy hemorrhage and assessment of risk factors. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 277:3095–3102. 10.1007/s00405-020-06060-1 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Boğrul MF, Ünal A, Yılmaz F, Sancaktar ME, Bakırtaş M. Comparison of two modern and conventional tonsillectomy techniques in terms of postoperative pain and collateral tissue damage. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;276:2061–2067. doi: 10.1007/s00405-019-05464-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tas E, Hanci V, Ugur MB, Turan IO, Yigit VB, Çınar F. Does preincisional injection of levobupivacaine with epinephrine have any benefits for children undergoing tonsillectomy? An intraindividual evaluation. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2010;74(10):1171–1175. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cokkeser Y, Akbay E, Cevik C, Mutlu O, Karaoglu E. A prospective self controlled trial to evaluate post operative pain after tonsillectomy by suturing Plica Tonsillaris. Int J Basic Clin Study. 2013;2(2):81–87. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hong SA, LaGorio L, Husain I. Post-tonsillectomy dysphagia secondary to glossopharyngeal nerve injury. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13(1):e232657. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2019-232657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ford LC, Cruz RM. Bilateral glossopharyngeal nerve paralysis after tonsillectomy: case report and anatomic study. Laryngoscope. 2004;114:2196–2199. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000149457.13877.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demir N, Serel Arslan S, İnal Ö, Karaduman AA. Reliability and validity of the Turkish Eating Assessment Tool (T-EAT-10) Dysphagia. 2016;31(5):644–649. doi: 10.1007/s00455-016-9723-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ersöz Unlü EC, Akın Oçal FC (2020) Can Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10) anticipate objective findings of dysphagia patients? Kbb ve Bbc Dergisi 28(2):146–151. 10.24179/kbbbbc.2020-75224