Abstract

Objectives

Rapid antigen tests have been used to prevent the spread of the COVID-19; however, there have been concerns about their decreased sensitivity to the Omicron variant. In this study, we assessed the sensitivity and specificity of the rapid antigen test compared with the PCR test among the players and staff members of the Japan Professional Football League and clubs. Furthermore, we evaluated the relationship between the sensitivity and the duration from the onset of symptoms to testing or vaccine status.

Design

This was a retrospective observational study.

Methods

We used 656 results from both the rapid antigen and PCR tests for COVID-19 using samples collected on the same day from 12 January to 2 March 2022, during the Omicron variant outbreak in Japan.

Results

The sensitivity of the rapid antigen test compared with the PCR test was 0.63 (95% CI: 0.53 to 0.73) and the specificity was 0.998 (95% CI: 0.995 to 1.000). There were no significant associations between the sensitivity and the duration from the onset of symptoms to testing (including asymptomatic cases in the category) or vaccination status (p>0.05) with small effect sizes (Cramer’s V or φ: ≤0.22).

Conclusions

Even during the Omicron outbreak, the sensitivity of the rapid antigen tests did not depend on the duration from the onset of symptoms to testing.

Keywords: COVID-19, risk management, infectious diseases, infection control

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

Rapid antigen testing was conducted two times a week on a regular basis during the Omicron variant outbreak among the players and staff of the Japan Professional Football League and clubs, and moreover, additional antigen and PCR testing was conducted in the clubs where infected individuals were identified.

We obtained the results from both rapid antigen and PCR tests for COVID-19 using samples collected on the same day.

We had a sufficient number of participants to examine the association between the sensitivity of the rapid antigen test and the duration from the onset of symptoms to testing.

Not all rapid antigen tests could be paired with PCR tests with the same date.

No information on individual characteristics potentially related to sensitivity and specificity was available.

Introduction

To prevent the spread of the COVID-19, active testing has been used to identify and isolate infected individuals, especially in populations at high risk of infection.1 Among the various testing methods including the reverse transcription-PCR test, antigen quantitative test and rapid antigen test, the rapid antigen test is the least sensitive, but it has the advantage of being inexpensive and providing prompt test results.2 In particular, high-frequency routine testing using rapid antigen test kits is more promising in reducing the spread of infection than highly sensitive, but low-frequency testing, because it can identify infected individuals from the time of infection until the onset of symptoms (ie, presymtomatic cases), when a high viral load is present.3 It has been noted; however, that the sensitivity of the rapid antigen tests may be lower for Omicron than for previous variants.4 5 In addition, the sensitivity of the rapid antigen tests may be particularly low during the first few days after infection (preprint).6 This means that rapid antigen testing may be less effective in identifying infected individuals with high viral load prior to the onset of symptoms during the Omicron variant outbreak. Thus, there is concern that the lower sensitivity of the rapid antigen tests during the short period after infection may reduce the effectiveness of the testing system in the population. However, it is not clear whether the sensitivity of rapid antigen tests is lower for Omicron than for previous variants. A previous study reported no large differences in the analytical sensitivity of the rapid antigen test in a comparison between representative Delta and Omicron isolates, using 10 test kits.7 In another case study with human participants, there was also no difference in the rapid antigen test sensitivity between the Delta and Omicron variants.8 Since both rapid antigen and other tests (eg, PCR tests) must be performed using samples collected on the same day from the same individuals to evaluate the sensitivity of the rapid antigen tests, studies based on human participants have been limited9 and these findings were not sufficient.

The Japan Professional Football League, a professional league of the most popular sport in Japan, collected the results of rapid antigen and PCR tests for COVID-19 among players and staff members in order to maintain and promote its activities.10 If the rapid antigen test was positive, the person was required to remain at home until the results of the PCR test or the physician’s diagnosis were obtained. If the PCR test was positive, the patient had to visit a medical institution. Since January 2022, rapid antigen testing was conducted two times a week on a regular basis. Moreover, additional antigen and PCR testing was often conducted on players and staff members in the clubs where infected individuals were identified. Consequently, from 12 January to 2 March 2022, during the period when the Omicron variants emerged in Japan, the number of cases in which both rapid antigen and PCR tests were performed on the same day exceeded 650, which made it possible to evaluate the sensitivity of the rapid antigen test compared with the PCR test.

In this study, we compared the results between the rapid antigen and PCR tests for COVID-19 among the players and staff of the Japan Professional Football League and clubs to determine the sensitivity and specificity of the rapid antigen test against the PCR test. We then assessed the relationships between the sensitivity and the duration from the onset of symptoms to testing, or vaccine status.

Methods

Participants

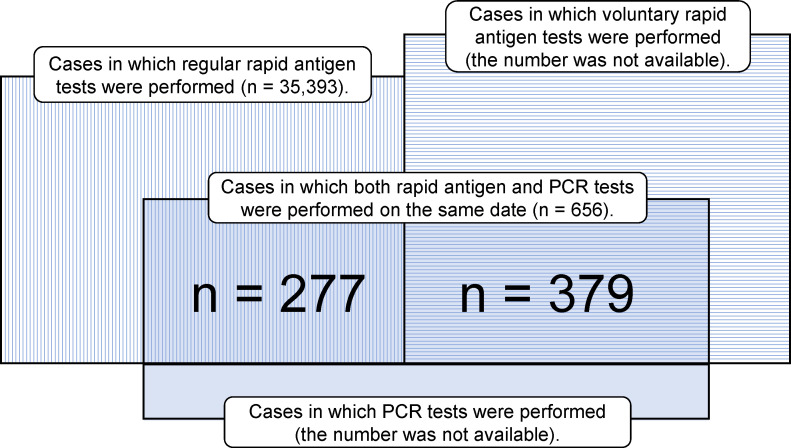

This study was a retrospective observational study. We obtained test results from 12 January to 2 March 2022. This was the period of the Omicron variant outbreaks in Japan (98.92% on 7 February 2022).11 In total, the Japan Professional Football League and clubs had 1759 players and 1864 staff members (as of February 2022). Each club has its own testing manager and physician. The Japan Professional Football League conducted a routine rapid antigen test (hereinafter, ‘regular test’) two times a week among players and staff members (a total of 35 393 tests during the study period). Each club also conducted additional rapid antigen testing (hereinafter, ‘voluntary test’) and PCR testing, but the number of such tests was not available. We obtained the data including a total of 656 cases in which both rapid antigen and PCR tests were performed using samples collected on the same date from players and staff members of the Japan Professional Football League and clubs (figure 1). If the rapid antigen and PCR tests were performed on different dates, they were not included in this study. Of the 656 cases, 277 were regular tests and 379 were voluntary tests. Among 58 clubs from J1 (the highest grade) to J3 (the lowest grade) in the Japan Professional Football League, 23 clubs (707 players and 754 staff members, as of February 2022) were included in this study as a result. Since personal information on the participants was not available, the breakdown of the number of players and staff members in 656 cases was unknown. In the process of collecting the test results from players and staff members, some of the cases in which both tests were negative may not have been available: that is, the number of cases reported in this study in which both tests were negative may be smaller than the actual number.

Figure 1.

The number of the rapid antigen and PCR tests during the Omicron variant outbreak among players and staff members of the Japan Professional Football League and clubs.

Table 1 shows the date and number of cases per club covered in this study. The same person was never subjected to rapid antigen or PCR tests more than once on the same day: the number of cases assessed in a given club on a given day represents the number of unique participants (no duplicates). Therefore, the maximum number of cases assessed on a given day in each club represents the minimum possible number of unique participants in the club. Furthermore, the same person did not belong to different clubs. Hence, the sum of the minimum possible number of unique participants in clubs (n=309) represents the minimum possible number of unique participants in this study.

Table 1.

The date and number of tests per club, and minimum possible number of unique participants during the Omicron variant outbreak among players and staff members of the Japan Professional Football League and clubs

| Club number | Date (n) | n (total) | Minimum possible number of unique participants |

| 1 | Jan 12 (2); Jan 19 (1); Jan 21 (1) | 4 | 2 |

| 2 | Jan 12 (1) | 1 | 1 |

| 3 | Jan 20 (1); Jan 27 (1); Jan 31 (1) | 3 | 1 |

| 4 | Jan 24 (47); Jan 28 (46); Jan 30 (2); Feb 4 (40); Feb 22 (1); Feb 28 (2) | 138 | 47 |

| 5 | Jan 19 (14); Jan 20 (2); Jan 22 (12); Jan 27 (1); Jan 28 (1) | 30 | 14 |

| 6 | Jan 30 (2); Jan 31 (3); Feb 2 (1) | 6 | 3 |

| 7 | Jan 30 (3); Feb 3 (1) | 4 | 3 |

| 8 | Feb 4 (2); Feb 7 (1) | 3 | 2 |

| 9 | Feb 8 (49); Feb 10 (1); Feb 12 (4) | 54 | 49 |

| 10 | Feb 12 (1); Feb 15 (1); Feb 17 (1); Feb 18 (1) | 4 | 1 |

| 11 | Feb 7 (1); Feb 16 (2); Feb 22 (37) | 40 | 37 |

| 12 | Feb 14 (1); Feb 16 (3); Feb 20 (13) | 17 | 13 |

| 13 | Feb 20 (1); Feb 22 (1); Feb 24 (1); Feb 28 (3) | 6 | 3 |

| 14 | Feb 21 (4); Feb 24 (2); Feb 25 (1); Feb 26 (1); Mar 1 (1); Mar 2 (4) | 13 | 4 |

| 15 | Feb 26 (5) | 5 | 5 |

| 16 | Mar 2 (1) | 1 | 1 |

| 17 | Feb 15 (4); Feb 16 (1); Feb 21 (3); Feb 22 (3) | 11 | 4 |

| 18 | Feb 21 (3) | 3 | 3 |

| 19 | Jan 29 (1) | 1 | 1 |

| 20 | Jan 23 (58); Jan 24 (58); Jan 25 (6); Jan 26 (3); Jan 27 (53); Jan 28 (4); Jan 30 (4); Jan 31 (6); Feb 3 (8) | 200 | 58 |

| 21 | Feb 5 (52); Feb 8 (50); Feb 11 (1) | 103 | 52 |

| 22 | Jan 12 (1); Jan 15 (3); Jan 17 (3) | 7 | 3 |

| 23 | Feb 18 (2) | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 656 | 309 |

n, number of cases in which both rapid antigen and PCR tests were performed on the same date.

Survey items

The information used in this study included the positivity or negativity of each test, presence or absence of symptoms, duration between the onset of symptoms and testing, vaccination status (ie, whether the participants were vaccinated: at least once, none, or unknown), manufacturer of the rapid antigen test kit, sample types used in the PCR test (ie, ‘saliva’, ‘nasal swab’ or ‘either or other’) and the type of test (‘regular test’, defined by the use of a routine rapid antigen test two times a week by the Japan Professional Football League or a ‘voluntary test’ other than a routine test). The onset of symptoms was based on the tally by the Japan Professional Football League, which comprised the individuals’ self-reported information that their health condition was different from usual (eg, fever, sore throat). The date of the onset of symptoms represented the date when the symptom developed. ‘−2 days’ and ‘−1 day’ represents 2 days or a day before symptom onset (ie, presymtomatic cases), respectively. Asymptomatic cases represented those who did not exhibit symptoms up to the time of testing and after.

The rapid antigen test was performed using nasal swab samples, and the kits used were the Abbott Panbio COVID-19 Antigen Rapid Test or the Roche SARS-CoV-2 Rapid Antigen Test. The sample types used in the PCR test were saliva or a nasal swab. Both samples were generally self-collected by the participants except for some rare cases of collection by the testing managers or physicians. The samples for the rapid antigen and PCR tests were collected and analysed separately. No samples were pooled. The players and staff members of the Japan Professional Football League and the clubs received lectures from their physicians on how to collect samples. Each club sent their samples to a medical or measuring laboratory for PCR testing. A Ct (threshold cycle) value of <40 was considered as positive. PCR test results were notified from 2 hours to the next day following sample collection. Other details of the analytical information of the PCR tests were not available. Since information on the manufacturer of the rapid antigen test kits and on the sample types used in PCR test was not available on an individual basis, we instead matched the individuals and their club using the information that was obtained from a survey of how each club conducted testing during the period. The clubs determined whether the manufacturer of the rapid antigen test kit was Abbott, Roche or either (ie, sometimes Abbott, sometimes Roche), and whether the sample types used in PCR test were saliva, nasal swab, either (ie, sometimes saliva, sometimes nasal swab) or other. The results (positivity or negativity) of the rapid antigen test among each of the 103 PCR-positive cases according to the duration from the onset of symptoms to testing (including asymptomatic cases in the category) were reported on the website of the Japan Professional Football League.12

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design, or conduct of the study. The information about this study was disclosed on the websites of the Institute of Medical Science of the University of Tokyo and the Japan Professional Football League.

Statistical analysis

In this study, the sensitivity and specificity of the rapid antigen test against the PCR test were first calculated by comparing the results (positivity or negativity) between both tests. We performed a Bootstrap method (10 000 samples) to estimate the 95% CI for sensitivity and specificity. We also used the Bootstrap method (10 000 samples) to estimate the 95% CI for sensitivity among only those whose PCR sample type was saliva (n=80). Next, among the cases with positive PCR results, the χ2 or Fisher’s exact test was performed to investigate the associations between the results of the rapid antigen test (positivity or negativity) and the duration from the onset of symptoms to testing (including asymptomatic cases in the category), vaccination status or test type. As an additional stratified analysis, only vaccinated individuals, those whose rapid antigen test kit manufacturer was Abbott, and those whose PCR sample type was saliva were used to examine the relationships between the rapid antigen test result (positivity or negativity) and the duration from the onset of symptoms to testing (in categories asymptomatic included) using the χ2 or Fisher’s exact test. In this stratified analysis, −2 and −1 days were grouped together as one category for the duration from the onset of symptoms to testing. Similarly, 1 and 2 days were combined into one category.

IBM SPSS V.28 and R V.4.2.013 were used for the statistical analysis.

Results

Of the 656 cases, 65 were positive for both the rapid antigen and PCR tests, 38 were negative for the antigen tests and positive for the PCR test, 1 was positive for the rapid antigen test and negative for the PCR test and 552 were negative for both (table 2). The sensitivity of the rapid antigen test compared with the PCR test was 0.63 (95% CI: 0.53 to 0.73) and the specificity was 0.998 (95% CI: 0.995 to 1.000).

Table 2.

Results of the rapid antigen and PCR tests during the Omicron variant outbreak among players and staff members of the Japan Professional Football League and clubs

| PCR | ||||

| + | − | Total | ||

| Rapid antigen | + | 65 (63%) | 1 (0.2%) | 66 |

| − | 38 (37%) | 552 (99.8%)* | 590 | |

| Total | 103 (100%) | 553 (100%) | 656 | |

*The values of the number of participants with both negative rapid antigen and PCR tests shown in the table may be smaller than the actual values. Some of the cases in which both tests were negative may not have been reported to the Japan Professional Football League.

Among the 103 cases that were positive for the PCR test, 74 cases (71.8%) were symptomatic (table 3). There were no significant associations between the sensitivity and the duration from the onset of symptoms to testing (Cramer’s V=0.146, p=0.837). Similarly, the sensitivity was not associated significantly with the vaccination status or test type (in the order: Cramer’s V=0.220, p=0.073; φ=0.012, p=0.904). Among those whose PCR sample type was saliva (n=80), the sensitivity was 0.58 (95% CI: 0.46 to 0.69).

Table 3.

Associations between the sensitivity of the rapid antigen test compared with the PCR test and the duration from the onset of symptoms to testing, vaccination status, kit manufacturer, sample type of PCR or test type during the Omicron variant outbreak among players and staff members of the Japan Professional Football League and clubs

| Items | Rapid antigen: + PCR: + |

Rapid antigen: − PCR: + |

Sensitivity | φ or Cramer’s V | P value | |

| Duration from the onset of symptoms to testing | −2 days* | 3 | 1 | 0.75 | 0.146 | 0.837† |

| −1 day* | 5 | 3 | 0.63 | |||

| 0 day | 20 | 16 | 0.56 | |||

| 1 day | 12 | 5 | 0.71 | |||

| 2 days | 5 | 4 | 0.56 | |||

| Asymptomatic | 20 | 9 | 0.69 | |||

| Vaccination | Yes | 43 | 27 | 0.61 | 0.220 | 0.073† |

| No | 9 | 9 | 0.50 | |||

| Unknown | 13 | 2 | 0.87 | |||

| Test type | Regular | 23 | 13 | 0.64 | 0.012 | 0.904‡ |

| Voluntary | 42 | 25 | 0.63 | |||

*‘−2 days’ and ‘−1 day’ represent cases that were asymptomatic at the time of tests but subsequently developed symptoms.

†Fisher’s exact test

‡χ2 test.

A stratified analysis of 70 vaccinated individuals showed no significant association between the sensitivity and the duration from the onset of symptoms to testing (Cramer’s V=0.084, p=0.955; table 4). Similarly, the stratified analysis of 45 individuals who used Abbott rapid antigen test and of 80 individuals whose PCR sample type was saliva showed no significant associations between the two (in the order: Cramer’s V=0.181, p=0.688; Cramer’s V=0.087, p=0.895).

Table 4.

Associations between the sensitivity of the rapid antigen test compared with the PCR test and the duration from the onset of symptoms to testing during the Omicron variant outbreak among players and staff members of the Japan Professional Football League and clubs: a stratified analysis

| Participants | Duration from the onset of symptoms to testing | Rapid antigen: + PCR: + |

Rapid antigen: − PCR: + |

Sensitivity | Cramer’s V | P value |

| Vaccine: yes (n=70) | −2 days or −1 day* | 7 | 3 | 0.70 | 0.084 | 0.955† |

| 0 day | 15 | 11 | 0.58 | |||

| 1 day or 2 days | 7 | 4 | 0.64 | |||

| Asymptomatic | 14 | 9 | 0.61 | |||

| Kit manufacturer: Abbott (n=45) | −2 days or −1 day* | 4 | 3 | 0.57 | 0.181 | 0.688† |

| 0 day | 13 | 3 | 0.81 | |||

| 1 day or 2 days | 3 | 1 | 0.75 | |||

| Asymptomatic | 13 | 5 | 0.72 | |||

| Sample type of PCR: saliva (n=80) | −2 days or −1 day* | 6 | 4 | 0.60 | 0.087 | 0.895‡ |

| 0 day | 16 | 14 | 0.53 | |||

| 1 day or 2 days | 10 | 8 | 0.56 | |||

| Asymptomatic | 14 | 8 | 0.64 |

*‘−2 days or −1 day’ represents cases that were asymptomatic at the time of the tests but subsequently developed symptoms.

†Fisher’s exact test.

‡χ2 test.

Discussion

Using 656 cases, we compared the rapid antigen and PCR test results for COVID-19 that were conducted on the same day among players and staff members of the Japan Professional Football League and clubs from January to March 2022, when the Omicron variant emerged, to determine the sensitivity and specificity of the rapid antigen test compared with the PCR test. We also investigated the relationship between the sensitivity and the duration from the onset of symptoms to testing, vaccination status or test type.

The sensitivity was 0.63 (95% CI: 0.53 to 0.73) and specificity was 0.998 (95% CI: 0.995 to 1.000). The specificity was possibly an underestimate because there may have been fewer reports on the number of cases that were negative for both tests than the actual number. The sensitivity was not significantly associated with the duration from the onset of symptoms to testing. Consistent results were found in the stratified analysis of only those who were vaccinated, those whose kit manufacturer was Abbott and those whose PCR sample type was saliva. Overall, the effect sizes were small (Cramer’s V <0.2). Furthermore, the sensitivity was not associated with vaccination status or test type (Cramer’s V or φ ≤0.22).

The results indicated that the sensitivity of the rapid antigen test compared with the results of the PCR test was independent of the duration from infection to testing or the presence or absence of symptom onset. This result was in contrast to that of a previous report (preprint)6: sensitivity of the rapid antigen test (Abbott or Quidel) compared with that of the PCR test (sample type: saliva) was 0.25 within 2 days from the first positive PCR test to the target testing and 0.9 since 3 days. The sensitivity in our study was higher than the sensitivity of the previous study (ie, 0.25 within 2 days from the first positive PCR test to the target testing). One possible explanation is that the players and staff members who participated in our study received lectures from their physicians on how to collect samples and that the tests were performed routinely, so that the samples were collected appropriately. The sensitivity of the rapid antigen tests may decrease when the tests are not performed according to the manufacturers’ instructions for use.14 Proper sample collection can lead to a high sensitivity.

The results of our study, which showed that the sensitivity of the rapid antigen test compared with the PCR test was 0.63 (95% CI: 0.53 to 0.73), may be used in combination with a model analysis to provide the fundamental knowledge required to establish a highly effective and efficient testing system. For example, a model analysis has estimated that the use of frequent rapid antigen testing is more effective than infrequent PCR testing in reducing the infection risk among populations such as professional sports players and staff members.15 Under the assumption of an incubation period of 5 days, an R0 of 4, and isolation with a test positive result, the infection risk (defined as ‘number of infected individuals remaining at the end of the 2 week isolation’) among populations, in which a daily rapid antigen test with a sensitivity compared with a PCR test of 0.6 that was conducted for 2 weeks, was estimated to be as effective as when PCR testing was performed every 3 days.15 Similarly, the sensitivity of 0.5 and 0.7 was equivalent to a PCR test being performed once every 4 days and every 2 days, respectively. Since the cost of the rapid antigen test is approximately one tenth that of the PCR test, the rapid antigen test can be performed more frequently than the PCR test assuming the same financial resources, and is therefore expected to be highly effective in controlling infection. However, since the Omicron variant is more infectious than previous variants16 and has a shorter incubation period,17 future testing strategies are expected to be combined with further model evaluations to match the characteristics of the Omicron variant.

Our study had some limitations. First, not all rapid antigen tests could be paired with a PCR test on the same date. Second, some of the cases in which both tests were negative may not have been reported to the Japan Professional Football League, which may have resulted in the underestimation of specificity, as described above. Third, the manufacturer of the test kits, and the samples used in the PCR tests, were based on the data provided by the clubs, and it was not possible to identify the manufacturer or sample types used by some participants. Therefore, we did not analyse the association between the sensitivity and the manufacturer or sample types. However, we confirmed that there was no association between the sensitivity and the duration from the onset of symptoms to testing by performing a stratified analysis of only those for whom the manufacturer was Abbott or the PCR sample type was saliva. Fourth, this study did not provide clinical diagnostic information on COVID-19. Therefore, it was not possible to assess the sensitivity of the rapid antigen test against the clinical diagnosis. In this regard, however, the PCR test is used worldwide as the gold standard to diagnose COVID-19, although the sensitivity of PCR against the clinical diagnosis was not 100%.18 We therefore assessed the sensitivity of the rapid antigen test compared with the PCR test. Fifth, we could not obtain information on the participants’ age, gender, presence or absence of underlying diseases or history of COVID-19 infection. The Ct values for the PCR tests were also only available from some of the participants. Therefore, it was not possible to evaluate the association between the sensitivity of these items. Since the sensitivity of the rapid antigen test varies depending on the Ct value in a wild-type strain,19 it may be useful to calculate the sensitivity of the rapid antigen test for the Omicron variant by stratified analysis using Ct values in a further study. Sixth, SARS-CoV-2 were not sequenced to confirm them as the Omicron variant. However, since the Omicron variant was predominant in the period under study (98.92%11) as described above, the possibility of other variants was very low. Seventh, the participants of this study were professional sports players and staff members who had been lectured by their physicians about the testing procedures and who were tested on a regular basis frequency. Caution is therefore required in applying the findings of our study to populations that may not be accustomed to testing procedures and such sample collection.

Despite such limitations, we analysed the sensitivity and specificity of the rapid antigen test against the PCR test during the Omicron variant outbreak, and found that the sensitivity was independent of the duration from the onset of symptoms to testing.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

Footnotes

Contributors: MM, HS, TI, MK, WN, TY and SI contributed to the conception of the study. HS and TI contributed to data curation. MM contributed to formal analysis, methodology and visualisation. SI contributed to supervision and project administration. MM drafted the manuscript. HS, TI, MK, WN, TY and SI reviewed and edited the manuscript. MM is responsible for the overall content as guarantor.

Funding: This work was conducted as part of ‘The Nippon Foundation - Osaka University Project for Infectious Disease Prevention (award/grant number: N/A).’

Competing interests: HS and TI received salaries from the Japan Professional Football League. WN and TY have received financial support from the Japan Professional Football League, the Yomiuri Giants, Tokyo Yakult Swallows, the Japan Professional Basketball League and the Kao Corporation in the context of measures at mass-gathering events. MM, MK, WN, TY and SI have attended the New Coronavirus Countermeasures Liaison Council jointly established by the Nippon Professional Baseball Organization and the Japan Professional Football League as experts without any reward. WN and TY were/are advisors to the Japan National Stadium and Japan Professional Football League. The data used in this study were provided from the Japan Professional Football League. Otherwise, these institutions had no role in study design. The findings and conclusions of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of any institution.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. We have included all the data produced in the present work in the manuscript. Note that the raw data used in the study were provided by the Japan Professional Football League, as described in this paper. We are unable to attach all the raw data for each participant in this paper due to the ethical restrictions.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved. This study was conducted with the approval of the Ethics Review Committee of the Institute of Medical Science, University of Tokyo (approval number 2022-1-0421). Testing was not conducted originally for research purposes and the Japan Professional Football League does not have personal information on all the results. Therefore, information about this study was disclosed on the websites of the Institute of Medical Science of the University of Tokyo and the Japan Professional Football League to provide participants with the opportunity to opt out of the study. The person in charge of each club also provided information about the study to potential participants (players and staff members).

References

- 1.Mina MJ, Andersen KG. COVID-19 testing: one size does not fit all. Science 2021;371:126–7. 10.1126/science.abe9187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loeffelholz MJ, Tang Y-W. Laboratory diagnosis of emerging human coronavirus infections - the state of the art. Emerg Microbes Infect 2020;9:747–56. 10.1080/22221751.2020.1745095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mina MJ, Parker R, Larremore DB. Rethinking Covid-19 test sensitivity — a strategy for containment. N Engl J Med Overseas Ed 2020;383:e120. 10.1056/NEJMp2025631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Osterman A, Badell I, Basara E, et al. Impaired detection of omicron by SARS-CoV-2 rapid antigen tests. Med Microbiol Immunol 2022;211:105–17. 10.1007/s00430-022-00730-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayart J-L, Degosserie J, Favresse J, et al. Analytical sensitivity of six SARS-CoV-2 rapid antigen tests for omicron versus delta variant. Viruses 2022;14:654. 10.3390/v14040654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Adamson B, Sikka R, Wyllie AL. Discordant SARS-CoV-2 PCR and rapid antigen test results when infectious: a December 2021 occupational case series. medRxiv 2022. 10.1101/2022.01.04.22268770 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deerain J, Druce J, Tran T, et al. Assessment of the analytical sensitivity of 10 lateral flow devices against the SARS-CoV-2 omicron variant. J Clin Microbiol 2022;60:e02479–21. 10.1128/jcm.02479-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Soni A, Herbert C, Filippaios A, et al. Comparison of rapid antigen tests' performance between Delta and Omicron variants of SARS-CoV-2 : A secondary analysis from a serial home self-testing study. Ann Intern Med 2022;175:M22–760. 10.7326/M22-0760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jüni P, Baert S, Corbeil A. Use of rapid antigen tests during the omicron wave. Science Briefs of the Ontario COVID-19 Science Advisory Table 2022;3. 10.47326/ocsat.2022.03.56.1.0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Japan Professional Football League . J.League Pub report. Secondary J.League Pub report 2021. Available: https://jlib.j-league.or.jp/-site_media/media/content/70/1/html5.html [Accessed 31 May 2022].

- 11.Our World in Data . SARS-CoV-2 variants in analyzed sequences, Japan. Secondary SARS-CoV-2 variants in analyzed sequences, Japan. Available: https://ourworldindata.org/grapher/covid-variants-area?country=~JPN [Accessed 31 May 2022].

- 12.Japan Professional Football League . News. Secondary news. Available: https://www.jleague.jp/news/article/21967/ [Accessed 4 Apr 2022].

- 13.R Development Core Team . R 4.2.0. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brümmer LE, Katzenschlager S, Gaeddert M, et al. Accuracy of novel antigen rapid diagnostics for SARS-CoV-2: a living systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2021;18:e1003735. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kamo M, Murakami M, Naito W, et al. COVID-19 testing systems and their effectiveness in small, semi-isolated groups for sports events. PLoS One 2022;17:e0266197. 10.1371/journal.pone.0266197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meo SA, Meo AS, Al-Jassir FF, et al. Omicron SARS-CoV-2 new variant: global prevalence and biological and clinical characteristics. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 2021;25:8012–8. 10.26355/eurrev_202112_27652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanaka H, Ogata T, Shibata T, et al. Shorter incubation period among COVID-19 cases with the BA.1 omicron variant. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2022;19:6330. 10.3390/ijerph19106330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kucirka LM, Lauer SA, Laeyendecker O, et al. Variation in false-negative rate of reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction-based SARS-CoV-2 tests by time since exposure. Ann Intern Med 2020;173:262–7. 10.7326/M20-1495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brümmer LE, Katzenschlager S, Gaeddert M, et al. Accuracy of novel antigen rapid diagnostics for SARS-CoV-2: a living systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med 2021;18:e1003735. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data are available upon reasonable request. We have included all the data produced in the present work in the manuscript. Note that the raw data used in the study were provided by the Japan Professional Football League, as described in this paper. We are unable to attach all the raw data for each participant in this paper due to the ethical restrictions.