Abstract

Bactofection offers a gene delivery option particularly useful in the context of immune modulation. The bacterial host naturally attracts recognition and cellular uptake by antigen presenting cells (APCs) as the initial step in triggering an immune response. Moreover, depending on the bacterial vector, molecular biology tools are available to influence and/or overcome additional steps and barriers to effective antigen presentation. In this work, molecular engineering was applied using Escherichia coli as a bactofection vector. In particular, the bacteriophage ΦX174 lysis E (LyE) gene was designed for variable expression across strains containing different levels of lysteriolysin O (LLO). The objective was to generate a bacterial vector with improved attenuation and delivery characteristics. The resulting strains exhibited enhanced gene and protein release and inducible cellular death. In addition, the new vectors demonstrated improved gene delivery and cytotoxicity profiles to RAW264.7 macrophage APCs.

Keywords: Escherichia coli, bactofection, gene delivery, gene therapy, attenuation

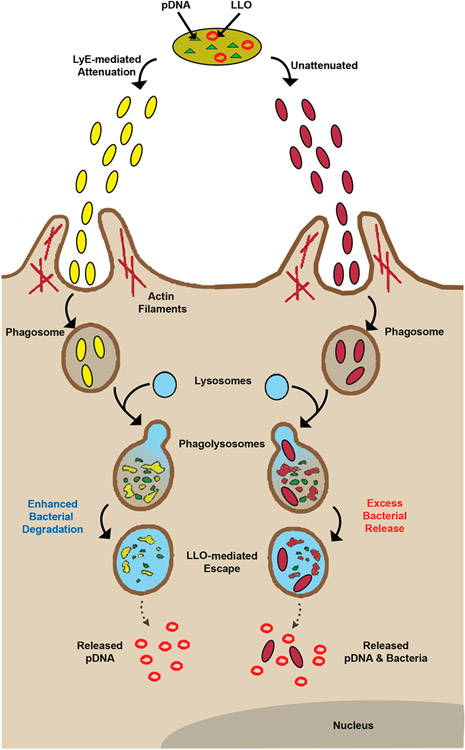

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The options available for genetic-based vaccination are diverse and substantial. In addition to the direct administration of naked DNA, a variety of vectors are available to assist the delivery process. The inclusion of such vectors is needed for a number of reasons, including the nonspecificity and limited delivery that generally accompany nonassisted DNA administration.1 Gene delivery carriers are broadly divided into viral and nonviral types. Of the nonviral options, the most commonly used vectors include biomaterials formulated into plasmid DNA (pDNA) carriers. Alternatively, bacterial vectors stand as nonviral delivery devices that maintain useful biological features needed for antigen presenting cell (APC) gene delivery.2

An APC will have a natural propensity to engulf large particles (1–10 μm). Furthermore, specific APC receptors will recognize several bacterial features that include cell wall components and prokaryotic DNA methylation patterns.3 Combined, these features accentuate the internalization process for bacterial vectors.2 The bacterial nature of the vector will also trigger activation features of the APC such as nitric oxide production.3 Once within the APC, endosomal escape must occur for effective gene delivery. Internalization mechanisms of pathogenic bacteria enable adept cytosolic colonization of APCs.4-6 One such mechanism is the lysteriolysin O (LLO) protein that provides a pH-sensitive means of perforating endosomal compartments during lysosomal transition, facilitating the natural cytosol-invasive capabilities of Listeria monocytogenes. Subsequent engineering of the parameters accompanying LLO expression provide an opportunity to tune and optimize gene delivery.4,7-12

The features of bacterial vectors, ranging from innate properties to recombinant DNA capabilities, allow distinct alternatives compared to other nonviral gene delivery options.2,3 However, a primary complication with using bacterial vectors is the potential for adverse side effects upon eventual administration. This is of greater concern for the direct application of pathogens that possess evolved delivery features but have clear toxicity concerns.4 Attenuation has been used in an attempt to alleviate such concerns, but the specter of reversion to pathogenicity remains.13-15 Alternatively, using the recombinant capabilities of workhorse biotech bacterial hosts allows transfer of gene delivery mechanisms from pathogenic to nonpathogenic strains (such as Escherichia coli), enabling greatly improved pDNA delivery during subsequent bactofection attempts.7-12 Additionally, although nonpathogenic strains of E. coli have proven to be safe in numerous applications and in vivo models,16 there are remaining concerns posed by exotoxins and other innate bacterial properties.12

Similar to the genetic engineering efforts utilized to improve the bactofection potency of E. coli vectors, additional efforts can be directed at designed attenuation to further eliminate issues of cytotoxicity. These same engineering options can also be used to simultaneously improve overall gene delivery for eventual utilization in genetic vaccination. Toward this goal, we report in this study the introduction of a bacteriophage lysis gene engineered into an E. coli vector for the initial purpose of improved attenuation. In so doing, the resulting strains demonstrated improved gene delivery, likely due to the same attenuation properties of the newly introduced lysis mechanism.

EXPERIMENTAL SECTION

Cell Lines and Strains.

A murine macrophage line (RAW264.7) was used for gene delivery assays and was kindly provided by Dr. Terry Connell (Department of Microbiology and Immunology, University at Buffalo, SUNY). Cells were maintained in medium prepared as follows: 50 mL of fetal bovine serum (heat inactivated), 5 mL of 100 mM MEM sodium pyruvate, 5 mL of 1 M HEPES buffer, 5 mL of penicillin/streptomycin solution, and 1.25 g of d-(+)-glucose added to 500 mL of phenol red-containing RPMI-1640 was mixed and filter sterilized. Cells were housed in T75 flasks and cultured at 37 °C/5% CO2.

The BL21(DE3) E. coli strain (Novagen) was used as the parent strain for generation of all gene delivery bacterial vectors. Base genetic manipulations were described previously.7,8 Resulting background strains are listed in Table 1 (with hly being the gene designation of LLO). The lethal lysis gene E (LyE) from bacteriophage ΦX174 was PCR-amplified from genomic DNA provided by Dr. Ryland Young (Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics, Texas A&M University) using forward primer 5′-AGGGAATTCGATGGTACGCTGGACTTTGTGG and reverse primer of 5′-AGGAAGCTTTCACTCCTTCCGCACGTAATT. The gel-purified ~280 bp band was digested with EcoRI and HindIII (sites underlined in the primer sequences) and ligated into pACYCDuet-1 (EMD Millipore) digested with the same enzymes to generate pCYC-LyE. The pCYC-LyE construct was screened and confirmed by colony PCR and restriction digest analysis. A luciferase reporter plasmid driven by a cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter (pCMV-Luc; Elim Biopharmaceuticals) was utilized during microplate reader-based transfection experiments using a Synergy 4 multi-mode microplate reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc.).

Table 1.

Bacterial Strains Summary

| strain | notes | LLO expression rankinga |

ref |

|---|---|---|---|

| BL21(DE3) | E. coli B F− dcm ompT hsdS(rB−mB−) gal λ(DE3) | N/A | 21 |

| BL21(DE3)/pCMV-Luc | BL21(DE3) carrying a high copy mammalian luciferase expression plasmid, driven by the CMV promoter | N/A | 8 |

| YWT7-hly/pCMV-Luc | Strain contains an inducible T7-hly cassette in the BL21(DE3) chromosome | 2 | 8 |

| YWTet-hly/pCMV-Luc | Strain contains a constitutively expressed Tet-hly cassette in the BL21(DE3) chromosome | 5 | 8 |

| BL21(DE3)/pCMV-Luc/pET29-hly | pET29-hly carries the hly gene under a lac-inducible T7 promoter | 1 | 7, 8 |

| BL21(DE3)/pCMV-Luc/pDP3615 | pDP3615 carries the hly gene under a constitutively expressed Tet promoter | 3 | 7, 8 |

| BL21(DE3)/pCMV-Luc/pQE-hly | pQE-hly carries the hly gene under a lac-inducible T5 promoter | 4 | this work |

| BL21(DE3)/pCYC-LyE | pCYC-LyE carries the endolysin gene E from bacteriophage ΦX174 under a lac-inducible T7 promoter | N/A | this work |

| YWT7-hly/pCMV-Luc/pCYC-LyE | 2 | 11 | |

| YWTet-hly/pCMV-Luc/pCYC-LyE | 5 | this work | |

| BL21(DE3)/pCMV-Luc/pET29-hly/pCYC-LyE | 1 | this work | |

| BL21(DE3)/pCMV-Luc/pDP3615/pCYC-LyE | 3 | this work | |

| BL21(DE3)/pCMV-Luc/pQE-hly/pCYC-LyE | 4 | this work |

Expression ranking is on a 1–5 scale, with 1 being the highest expression strain and 5 being the lowest.

Bacterial Growth Inhibition and Membrane Shear.

To determine the influence of LLO and LyE on cellular viability, respective glycerol stocks containing strains from Table 1 were used to initiate 3 mL overnight starter cultures prior to seeding (2.5% (v/v)) 50 mL cultures in lysogeny broth (LB) medium at 37 °C/250 rpm until an OD600 of 0.4 was obtained. At this time, strains were induced with various concentrations of isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and incubated at 22, 30, and 37 °C for various time points. Every 30 min, the optical density at 600 nm was measured using a GENEYS 20 visible spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific) to assemble growth curves.

To assess bacterial membrane weakening, at every half-hour time point, 200 μL of cultured bacteria was collected by centrifugation, resuspended in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), and sonicated at 20% capacity for 5 s using a Branson 450D sonifier (400 W, tapered microtip). Sonicated samples were then plated on LB agar plates and allowed to incubate for 24 h before growth was quantified by counting colony forming units (CFUs).

Protein and DNA Release.

To quantify the amount of protein and DNA released from the supernatant of bacterial samples (from Table 1), 10 mL LB cultures were inoculated with 2.5% (v/v) of an overnight starter culture and incubated at 37 °C to an OD600 of 0.4. Next, strains were induced with 100 μM IPTG and allowed to incubate at 30 °C for an additional hour. Each strain was then standardized to 0.5 OD600 prior to centrifugation and supernatant collection. Supernatants were measured for absorbance of 260 nm for DNA quantification and 280 nm for protein quantification. Polymyxin B (PLB) was used as a positive control (added at 0.5 mg/mL during IPTG addition), as it has a known bacterial cell wall disruption mechanism,17-20 and processed as described above.

Hemolysis Assay.

To determine the amount of hemolysis resulting from selected strains of Table 1, cellular supernatants (collected from strains cultured as described for DNA and protein release assays) were incubated with sheep red blood cells (Hemostat Laboratories). Supernatant was taken either from fully lysed bacterial samples (sonication at 20% for 30 s) or pelleted bacteria. One hundred microliters of respective supernatant was mixed with 900 μL of 5% sheep red blood cells (HemoStat Laboratories) in assay buffer,7 and another 100 μL was mixed with 900 μL of PBS (pH 7.4), followed by incubating for 1 h at 36 °C. LLO activity was then measured by recording absorbance at 541 nm, with results depicted as percentage of total blood lysis (interpolated from a blood lysis standard plot). Accordingly, in Figure S1, hemolysis values from fully lysed strains containing LLO expression variants were standardized by the BL21(DE3)/pCMV-Luc/pET29-hly value to provide a normalized hemolysis metric.

Cell Seeding and Gene Delivery.

For gene delivery experiments, the RAW264.7 line was seeded into two different types of 96-well plates at 3 × 104 cells/well in 100 μL of antibiotic-free media and incubated for 24 h to allow attachment. A tissue culture-treated, flat-bottomed, sterile, white polystyrene 96-well plate was used for luciferase assays, whereas a tissue culture-treated, clear, sterile polystyrene 96-well plate was used for bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assessment as well as a 3-(4, 5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay.

Bacterial cultures were grown as described for DNA and protein release assays. After a 1 h induction with 100 μM IPTG at 30 °C, samples were collected, washed, and standardized to 0.5 OD600 in PBS. Each sample was diluted in antibiotic-free RPMI-1640 to create different bacteria-to-macrophage multiplicity of infection (MOI) ratios. Following attachment, macrophage medium was replaced with 50 μL of each respective bacterial sample and allowed to incubate for an hour. After incubation, 50 μL of gentamicin-containing RPMI-1640 was added to each well to eliminate external/non-phagocytized bacteria. After a second 24 h incubation (48 h after initial seeding), plates were analyzed for luciferase expression using the Bright Glo assay (Promega) and protein content was assessed using the micro BCA protein assay kit (Pierce) according to each manufacturer’s instructions. Gene delivery was calculated by normalizing luciferase expression by protein content for each well/plate. Results derive from 12 replicates and four independent experiments.

MTT Assay.

Cytotoxicity resulting from E. coli vectors was determined using a modified MTT assay.12 Briefly, after macrophage seeding and the 24 h incubation, media was removed and cells were combined with bacterial vectors prepared as described above except the delivery volume was 50 μL if gentamicin treatment was included or 100 μL if gentamicin treatment was excluded. Following another 24 h incubation, cells were assayed with MTT solution (5 mg/mL), added at 10% v/v, for 3 h at 37 °C/5% CO2. Medium plus MTT solution was then aspirated and replaced by DMSO to dissolve the formazan reaction products. Following agitated incubation for 1 h, the optical density of the formazan solution was analyzed using a Synergy 4 multi-mode microplate reader at 570 nm, with 630 nm serving as the reference wavelength. Results are presented as a percentage of untreated cells (100% viability).

Statistical Evaluation.

Unless otherwise indicated, data presented were generated from three independent experiments. Error bars represent standard deviation values. Statistical significance (95% confidence) was calculated using mean values from select experimental samples compared with respective control means.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Bacterial Vector Design.

The E. coli design included two heterologous lysis proteins. LLO was introduced to enhance endosomal escape after bacterial vector phagocytosis by an APC. This mechanism is well-understood and occurs naturally during pathogenic transition to the cytosol.4 As such, LLO expression within E. coli would assist content transport from the endosome to the cytoplasm for subsequent gene transfer to the nucleus.

To the strains that contain variable LLO expression (Table 1) was introduced a second lysis gene, LyE. LLO was used to target the mammalian endosome during the process of gene delivery, even though our previous studies suggested that LLO was also disrupting E. coli cellular membranes.12 LyE inclusion was introduced initially to disrupt E. coli membranes for the purpose of designed attenuation. When combined, we were also interested in the potential for both mechanisms to contribute to improved bactofection.

Growth Inhibition and Cell Membrane Weakening.

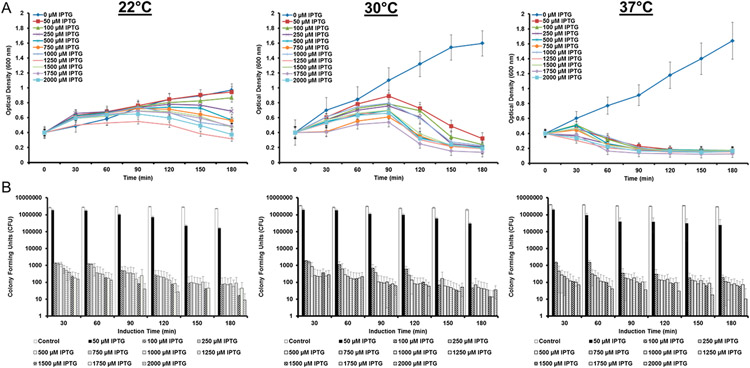

The first measure of LyE expression was the impact upon E. coli cellular health. Cell growth was monitored over the course of cultures in which LyE expression was induced (Figure 1A). LyE expression had a negative impact upon E. coli survival, as demonstrated by decreased viability as a function of IPTG concentration and temperature. Similarly, E. coli membrane integrity was tested by applying short-term exposure to sonication. The inclusion of LyE demonstrates heightened sensitivity to external shear stress (Figure 1B). Taken together, these results support the attenuation aspects of LyE expression within the E. coli vectors and demonstrate the ability to tune bacteria viability according to differential LyE levels and process conditions.

Figure 1.

Effect of LyE expression upon bacterial growth and membrane stability. (A) Growth and (B) shear studies of BL21(DE3)/pCYC-LyE at three temperatures and various IPTG induction concentrations.

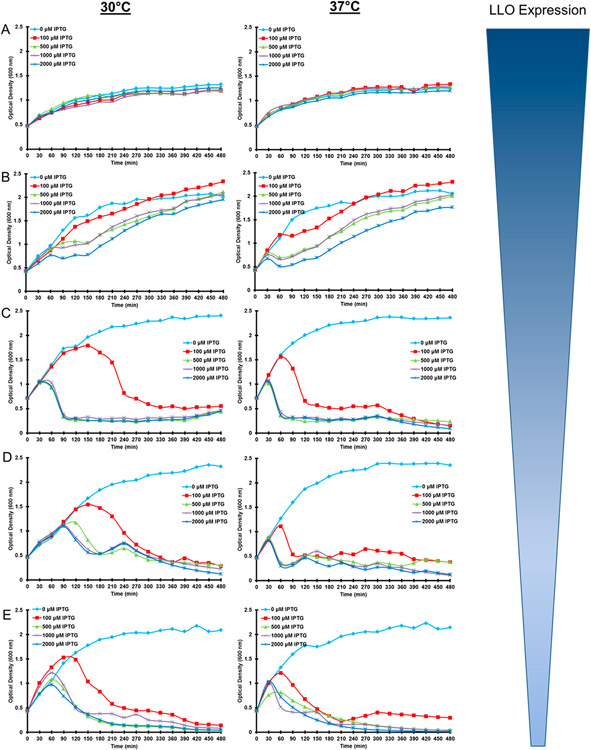

An integral driving force to bacterial-based gene delivery is the incorporation of a release mechanism from the degradative pathways associated with APC vector processing.2 Specifically, LLO was selected as the heterologous protein to be concurrently expressed in the proposed LyE system. Thus, LyE was incorporated into bacterial strains possessing variable LLO expression levels (as measured by innate hemolysis of expressed protein; Figure S1). Cell growth of these LyE/LLO expression vectors was monitored (Figure 2). As before, bacterial viability was negatively correlated with increases in either IPTG concentration or temperature. Interestingly, LLO expression diminished the observable effect of LyE expression due to metabolic burden, where heightened levels of LLO reduce the amount of LyE produced concomitantly (data not shown). Resultantly, an optimal expression condition emerged that maintains bacterial growth for a short period before cellular viability begins to decline, thus providing a window of gene delivery application prior to attenuation. In Figure 2, this is best represented after a 1 h induction using 100 μM IPTG at 30 °C (especially for lower LLO expression strains).

Figure 2.

Growth curves of LyE- and LLO-expressing E. coli strains at two temperatures and various IPTG induction concentrations. Graphs are arranged by strain-specific LLO expression: (A) pET29-hly/pCYC-LyE, (B) YWT7-hly/pCYC-LyE, (C) pDP3615/pCYC-LyE, (D) pQE-hly/pCYC-LyE, and (E) YWTet-hly/pCYC-LyE.

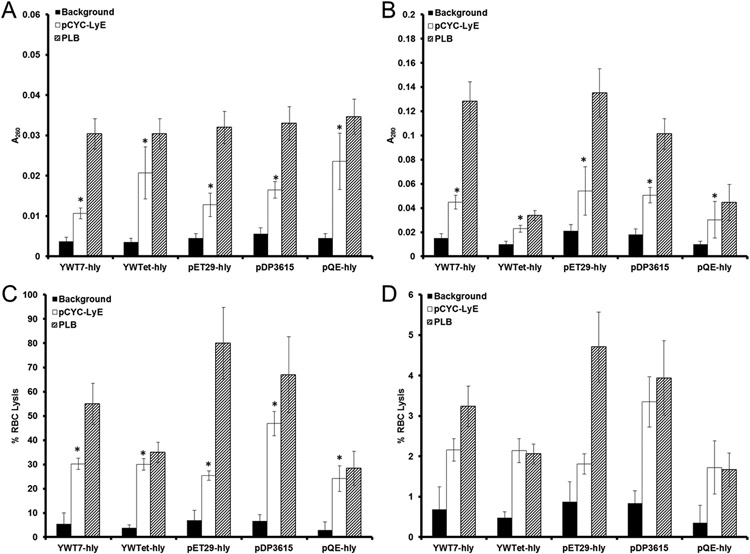

DNA and Protein Release.

The second measure of LyE impact was the release of DNA and protein from the E. coli cells during expression. Cellular disruption caused by LyE also influenced macromolecule release, as presented in Figure 3. The results of this analysis indicate that LyE expression is providing a potential dual action in the overall process of cargo delivery. Namely, attenuation is observed in addition to heightened macromolecule release. Moreover, bacterial DNA and protein were released in a tunable fashion (Figure 3A,B). Interestingly, the greatest relative macromolecule release was obtained by strains (YWTet-hly and containing pQE-hly) that possessed the greatest decreases in viability (Figure 2). In contrast, the highest LLO expression systems (YWT7-hly and pET29-hly), which did not demonstrate sustained decreases in cell viability upon coexpression of LyE (Figure 2), provided moderate release (relative to the total amount of DNA and protein released by complete cell lysis [PLB-treated samples]). Given the lack of observable decreases in cell viability coupled to moderate macromolecule release, the highest LLO expression systems represent another tier of bacterial stability that provides viable but attenuated vectors. In the context of gene delivery, increased release of cellular cargo may enhance the overall process of delivery, especially when coupled with additional lysis mechanisms such as LLO expression.12

Figure 3.

Bacterial release of macromolecules caused by LyE expression. (A) DNA and (B) protein release of bacterial strains (carrying pCMV-Luc) induced with 100 μM IPTG for 1 h at 30 °C. By incubating released protein with red blood cells (RBCs), hemolysis was recorded in buffer at either pH 5.15 (C) or 7.4 (D). Asterisk (*) indicates statistical improvements (95% confidence) compared to the associated strain without LyE (background).

Hemolytic Activity.

The measurement of hemolysis is a critical factor for predicting both cytotoxicity (in vitro and in vivo) and endosomal escape. The bacterial strains used in the current study provide an increasing LLO lysis profile in line with associated strain expression capability (Figure S1), which, in turn, enables direct analysis of LLO expression levels in LyE-expressing bacteria.8

With the confirmed release of protein, the next step is to assess the pH-dependent activity of released LLO. Thus, by incubating released protein with RBCs under either acidic (pH 5.15) or neutral (pH 7.4) conditions, LLO was assessed for its naturally acidic pH activity (Figure 3C,D). The diminished activity in neutral pH suggests that if bacterial degradation was to occur extracellularly, instead of in the desired phagolysomal compartment, insignificant off-target effects would follow.

Macrophage Cellular Toxicity.

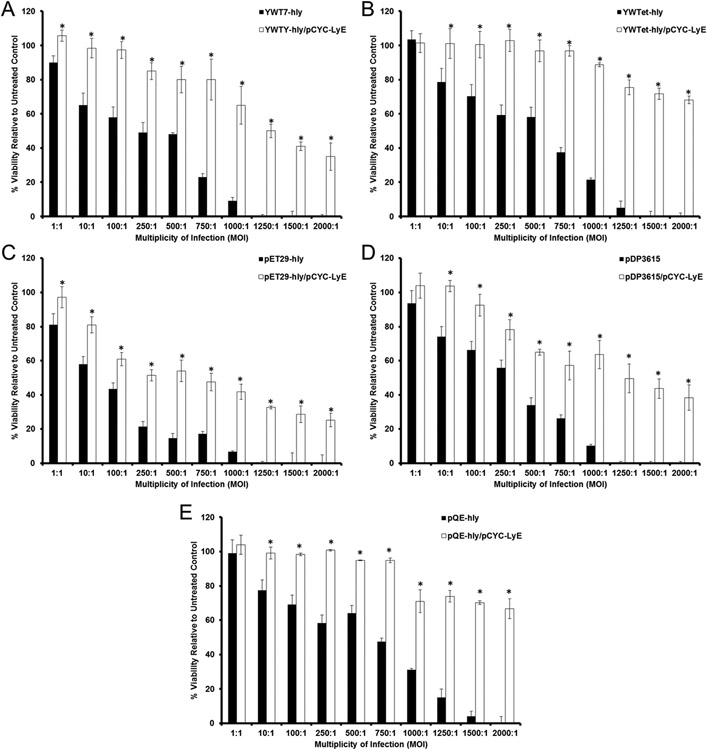

After completing the analysis of LyE expression and E. coli cellular function, the next set of experiments was dedicated to assessing the impact that the new E. coli vectors had upon macrophage coincubation. The first such analysis was RAW264.7 cellular viability. As shown in Figures S2 and S3, LyE expression markedly improved survival of the RAW264.7 cell line at excessive macrophage-to-bacteria delivery ratios (MOIs) with respect to increases in temperature and IPTG concentration. Strikingly, even when gentamicin addition (designed to kill excess extracellular bacteria) was withheld, APC viability significantly improved, reaching levels of low to no toxicity. Such a result further confirms the attenuation properties of LyE when expressed within E. coli and suggests enhanced overall capabilities of the host when used in both in vitro and in vivo gene and protein delivery formats due to significantly improved safety profiles.

With the initial positive cytotoxicity evaluation of LyE-expressing bacteria, the next step was to assess the effect of concomitant LyE–LLO expression upon APC viability. Previous studies have suggested that the presence of high levels of LLO results in APC toxicity.8,22 Thus, in preparation for future gene delivery experiments, strains with LLO alone and the LyE–LLO combination were prepared using a 1 h induction with 100 μM IPTG at 30 °C (Figure 4 and Figure S4). Unexpectedly, at all MOIs, APC viability was statistically improved and distinct LLO expression trends emerged. Namely, the highest LLO expression system (containing pET29-hly), regardless of the statistical improvement mediated by LyE expression, possessed high levels (<60% viability) of cytotoxicity at higher MOIs (100:1 or above). Conversely, the lowest LLO expression systems (containing pQE-hly or YWTet-hly) possessed ~80% viability at all MOIs (in most cases, ~100% viability). These results permit the use of an additional magnitude of MOIs for gene delivery studies, which have been historically limited to lower values.7-12,23-29 Improvements upon bacterial-related cytotoxicity can be attributed to a combination of membrane weakening and a reduction in continuous bacterial load (i.e., the number of viable bacteria not being processed; Scheme 1).

Figure 4.

Cytotoxicity of RAW264.7 cells incubated with E. coli strains carrying a pCMV-Luc reporter plasmid and expressing both LyE and LLO. Bacterial strains were induced with 100 μM IPTG for 1 h at 30 °C. Asterisk (*) indicates statistical improvements (95% confidence) compared to paired control.

Scheme 1.

Proposed Phagocytosis and Process Mechanisms of LLO–LyE Expressing Bacterial Vectors (Yellow) Compared to Those for LLO Alone (Unattenuated; Red) Vectors

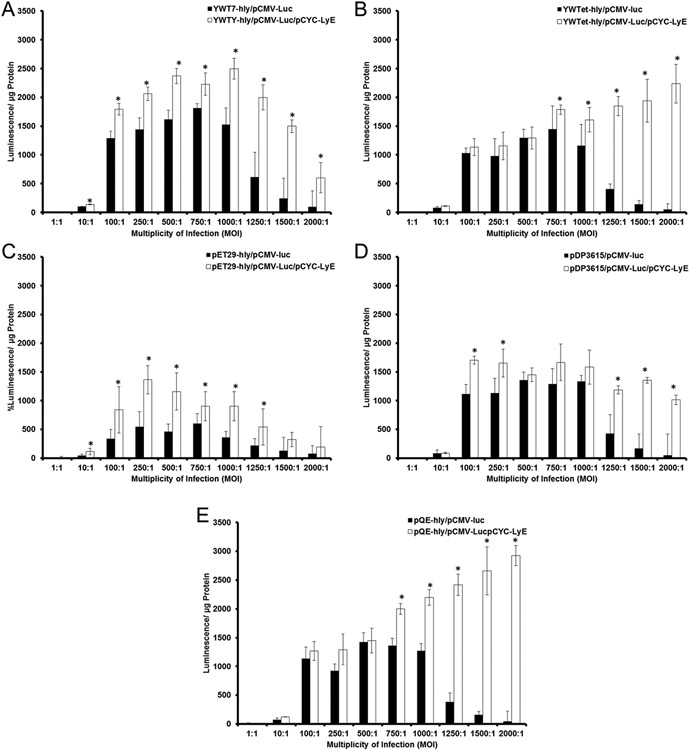

Gene Delivery Studies.

The final measure of LyE impact was assessing gene delivery of the E. coli strains. As summarized in Figure 5, gene delivery results for LyE–LLO vectors were statistically improved compared to those for LLO-alone vectors for most MOIs across strains. With exception to the lowest LLO expression strains (YWTet-hly and containing pQE-hly), gene delivery for all other LyE–LLO vectors continued to increase with MOI increases before reaching a plateau. Moreover, the lowest LLO expression strains continued to possess a linear improvement in gene delivery without any signs of saturation. As a consequence, the best performing strain was pQE-hly/pCMV-Luc/pCYC-LyE. This observation may be the result of a low cytotoxicity profile (>~80% at all MOIs; Figure 4) and suggests a delicate balance of LLO and cytotoxicity. For example, the higher LLO expression strains possess significant APC cytotoxic profiles at higher MOIs regardless of LyE incorporation, leading to subsequent drops in associated gene delivery. Conversely, the lower LLO expression strains are unable to mediate statistical improvements in gene delivery prior to MOIs at or above 750:1, indicating that the associated increase in APC viability is not enough to offset the lack of LLO for lower MOIs. These results demonstrate the positive combined effect of LyE and LLO upon macrophage gene delivery. Beyond improved attenuation, the combined mechanisms utilized here result in improved gene delivery, emphasizing the potential benefits of multiple lysis mechanisms in the context of eventual genetic vaccination.

Figure 5.

Gene delivery effects upon expression of LyE. Bacterial strains were induced with 100 μM IPTG for 1 h at 30 °C. Asterisk (*) indicates statistical improvements (95% confidence) compared to paired control.

The results obtained also mirror a separate study completed by our group in which the E. coli vector was attenuated using a chemical mechanism.12 Specifically, the antibiotic polymyxin B (PLB) was used to attenuate E. coli prior to bactofection, which led to improved target cell viability. Interestingly, PLB has a similar attenuation mechanism as that of LyE.17-20 Namely, the antibiotic forms pores in the membranes of the E. coli cell. The improved attenuation outcome using either mechanism illustrates both the chemical and biological options available to alter the E. coli vector. The current study highlights the cellular engineering capabilities associated with E. coli in terms of designed expression of LyE or other biological routes to attenuation. Furthermore, once introduced to the cell, mechanisms implemented via cellular engineering offer a permanent modification to the vector without the need to continually treat cells using an external attenuation agent such as PLB.

CONCLUSIONS

In this study, E. coli bactofection was improved through the introduction of a LyE gene designed primarily for attenuation purposes. The LyE mechanism resulted in E. coli cellular damage that, in turn, provided improved cellular viability to RAW264.7 cells targeted in the context of bactofection. Importantly, the inclusion of LyE further improved overall gene delivery (in conjunction with LLO expression), most likely because of the synergistic attenuation and macromolecular release properties demonstrated by the engineered E. coli cells. The combined features of the new E. coli host thus led to improved overall gene delivery, which is viewed positively for future efforts using this vector in genetic vaccination formats.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors recognize support from NIH award AI088485 (B.A.P.) and a SUNY–Buffalo Schomburg fellowship (C.H.J.).

Footnotes

Supporting Information

Figure S1: Normalized hemolysis data of E. coli expressing different levels of LLO at pH 5.15. Figure S2: Cytotoxicity of RAW265.7 cells incubated with LyE-expressing E. coli. Figure S3: Cytotoxicity of RAW265.7 cells incubated with LyE-expressing E. coli. Figure S4: Cytotoxicity of RAW265.7 cells incubated with LLO-expressing E. coli. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Jones CH; Chen CK; Ravikrishnan A; Rane S; Pfeifer BA Overcoming nonviral gene delivery barriers: perspective and future. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2013, 10, 4082–4098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Parsa S; Pfeifer B Engineering bacterial vectors for delivery of genes and proteins to antigen-presenting cells. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2007, 4, 4–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Jones CH; Hakansson AP; Pfeifer BA Biomaterials at the interface of nano- and micro-scale vector–cellular interactions in genetic vaccine design. J. Mater. Chem. B 2014, 2, 8053–8068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Birmingham CL; Canadien V; Kaniuk NA; Steinberg BE; Higgins DE; Brumell JH Listeriolysin O allows Listeria monocytogenes replication in macrophage vacuoles. Nature 2008, 451, 350–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Price JV; Vance RE The macrophage paradox. Immunity 2014, 41, 685–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Harb OS; Gao LY; Abu Kwaik Y From protozoa to mammalian cells: a new paradigm in the life cycle of intracellular bacterial pathogens. Environ. Microbiol 2000, 2, 251–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Higgins DE; Shastri N; Portnoy DA Delivery of protein to the cytosol of macrophages using Escherichia coli K-12. Mol. Microbiol 1999, 31, 1631–1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Parsa S; Wang Y; Rines K; Pfeifer BA A high-throughput comparison of recombinant gene expression parameters for E. coli-mediated gene transfer to P388D1 macrophage cells. J. Biotechnol 2008, 137, 59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Parsa S; Wang Y; Fuller J; Langer R; Pfeifer BA A comparison between polymeric microsphere and bacterial vectors for macrophage P388D1 gene delivery. Pharm. Res 2008, 25, 1202–1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Jones CH; Chen CK; Chen M; Ravikrishnan A; Zhang H; Gollakota A; Chung T; Cheng C; Pfeifer BA PEGylated cationic polylactides for hybrid biosynthetic gene delivery. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2015, 12, 846–856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Jones CH; Ravikrishnan A; Chen M; Reddinger R; Kamal Ahmadi M; Rane S; Hakansson AP; Pfeifer BA Hybrid biosynthetic gene therapy vector development and dual engineering capacity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2014, 111, 12360–12365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Jones CH; Rane S; Patt E; Ravikrishnan A; Chen CK; Cheng C; Pfeifer BA Polymyxin B treatment improves bactofection efficacy and reduces cytotoxicity. Mol. Pharmaceutics 2013, 10, 4301–4308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Medina E; Guzman CA Use of live bacterial vaccine vectors for antigen delivery: potential and limitations. Vaccine 2001, 19, 1573–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Dietrich G; Spreng S; Favre D; Viret JF; Guzman CA Live attenuated bacteria as vectors to deliver plasmid DNA vaccines. Curr. Opin. Mol. Ther 2003, 5, 10–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Daudel D; Weidinger G; Spreng S Use of attenuated bacteria as delivery vectors for DNA vaccines. Expert Rev. Vaccines 2007, 6, 97–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Chart H; Smith HR; La Ragione RM; Woodward MJ An investigation into the pathogenic properties of Escherichia coli strains BLR, BL21, DH5alpha and EQ1. J. Appl. Microbiol 2000, 89, 1048–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Katrukha GS; Baratova LA; Silaev AB A study of the mechanism of polymyxin M inactivation. Experientia 1968, 24, 540–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Hsu Chen CC; Feingold DS The mechanism of polymyxin B action and selectivity toward biologic membranes. Biochemistry 1973, 12, 2105–2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Edberg SC; Bottenbley CJ; Singer JM The mechanism of inhibition of aminoglycoside and polymyxin class antibiotics by polyanionic detergents. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med 1976, 153, 49–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Gilleland HE Jr.; Farley LB Adaptive resistance to polymyxin in Pseudomonas aeruginosa due to an outer membrane impermeability mechanism. Can. J. Microbiol 1982, 28, 830–840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Studier FW; Moffatt BA Use of bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase to direct selective high-level expression of cloned genes. J. Mol. Biol 1986, 189, 113–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Geoffroy C; Gaillard JL; Alouf JE; Berche P Purification, characterization, and toxicity of the sulfhydryl-activated hemolysin listeriolysin O from Listeria monocytogenes. Infect. Immun 1987, 55, 1641–1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Radford KJ; Higgins DE; Pasquini S; Cheadle EJ; Carta L; Jackson AM; Lemoine NR; Vassaux G A recombinant E. coli vaccine to promote MHC class I-dependent antigen presentation: application to cancer immunotherapy. Gene Ther. 2002, 9, 1455–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Seow Y; Wood MJ Biological gene delivery vehicles: beyond viral vectors. Mol. Ther 2009, 17, 767–777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Critchley RJ; Jezzard S; Radford KJ; Goussard S; Lemoine NR; Grillot-Courvalin C; Vassaux G Potential therapeutic applications of recombinant, invasive E. coli. Gene Ther. 2004, 11, 1224–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Cheung W; Kotzamanis G; Abdulrazzak H; Goussard S; Kaname T; Kotsinas A; Gorgoulis VG; Grillot-Courvalin C; Huxley C Bacterial delivery of large intact genomic-DNA-containing BACs into mammalian cells. Bioeng. Bugs 2012, 3, 86–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Larsen MD; Griesenbach U; Goussard S; Gruenert DC; Geddes DM; Scheule RK; Cheng SH; Courvalin P; Grillot-Courvalin C; Alton EW Bactofection of lung epithelial cells in vitro and in vivo using a genetically modified Escherichia coli. Gene Ther. 2008, 15, 434–442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Grillot-Courvalin C; Goussard S; Courvalin P Wild-type intracellular bacteria deliver DNA into mammalian cells. Cell. Microbiol.y 2002, 4, 177–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Grillot-Courvalin C; Goussard S; Courvalin P Bacteria as gene delivery vectors for mammalian cells. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol 1999, 10, 477–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.