Abstract

The role of cytoreductive nephrectomy has become unclear since the introduction of immunotherapy which is now the backbone of the treatment for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Different combinations are used based on the prognosis. Achieving a complete response would be ideal and includes radiographic disappearance of lesions. However, there have been a few reported cases of pathological complete response with persistent radiographic evidence of cancer. The authors report a case of pathological complete response despite persistent radiographic evidence of residual disease in a patient with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with pembrolizumab and axitinib. The patient subsequently underwent cytoreductive nephrectomy after the 13th dose of pembrolizumab. The resected mass consisted of scar tissue with no viable tumor cells seen on pathology but only scar tissue. This case reveals that persistent radiographic evidence of the tumor may be explained by scar tissue, challenging the role of cytoreductive nephrectomy in the era of immunotherapy.

Keywords: Metastatic renal cell carcinoma, Immunotherapy, Pathologic complete response, Cytoreductive nephrectomy

Introduction

Metastatic renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is treated with a combination of systemic immunotherapy drugs, including programmed cell death-1 protein (PD-1) checkpoint inhibitors, programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) checkpoint inhibitors, anti-cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) antibodies, vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitors, or mammalian (mechanistic) target of rapamycin inhibitors [1]. Different combinations are used based on the International Metastatic Renal Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium (IMDC) [2]. This prognostic model integrates six adverse factors dividing patients into three risk groups: favorable, intermediate, or poor risk. First line combination regimens typically include Nivolumab plus Ipilimumab, pembrolizumab plus axitinib, or avelumab plus axitinib. Second-line agents such as nivolumab or cabozantinib monotherapy can be used in refractory disease [3]. In comparison to Sunitinib monotherapy, which is an approved first- or second-line agent, combination regimens were not found to be more toxic [4] but did have more gastrointestinal side effects, namely diarrhea and low appetite [5].

Assessing treatment response is done using the response evaluation criteria in solid tumors (RECIST) (version 1.1) [6]. It separates response into complete response (CR) (disappearance of all lesions and pathological lymph nodes), partial response (PR) (≥30% decrease in the sum of the longest diameter of the target lesions compared with baseline), progressive disease (≥20% increase in the sum of the longest diameters and ≥5 mm absolute increase in the sum of the longest diameters, or new lesions), or stable disease (neither PR nor progressive disease). The role of cytoreduction nephrectomy (CN) has been unclear since the introduction of immunotherapy [7]. Singla et al. [8] demonstrated better overall survival with CN and immunotherapy than immunotherapy alone. In contrast, the CARMENA trial showed non-inferiority of mono-immunotherapy compared to nephrectomy done before immunotherapy [8, 9]. CR is identified with imaging; however, there have been a few reported cases in which there is residual radiographic evidence despite having a pathological CR [10–12]. The authors present a case of pathological CR using pembrolizumab (PD-1 checkpoint inhibitor) and axitinib (vascular endothelial growth factor inhibitor) in a patient who underwent deferred CN with no complete radiographic response, questioning the necessity for CN.

Case Report

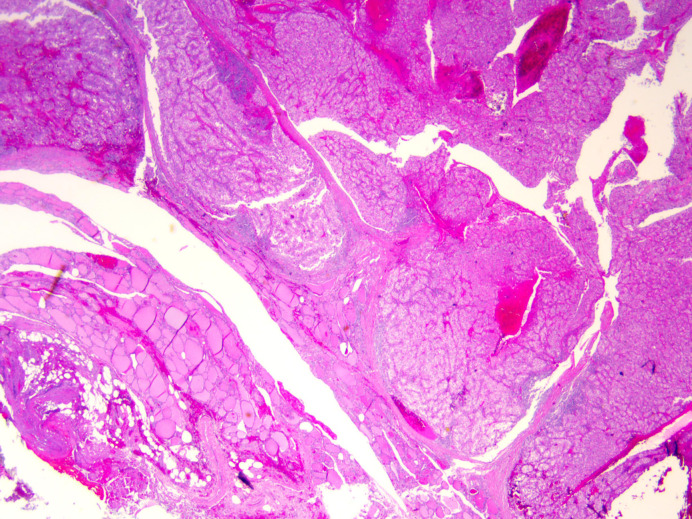

We present a case of a 48-year-old Caucasian female with no significant medical history who presented with anterior neck swelling and tenderness. She was otherwise asymptomatic. She did not have a family history of cancer and did not smoke. Further workup revealed a thyroid mass for which she had a right thyroid lobectomy and isthmusectomy. Pathology revealed clear-cell metastatic RCC (shown in Fig. 1). Furthermore, she had a computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis which demonstrated a 7 × 6.5 × 7.6 cm right superior renal pole lesion with mild extracapsular extension, a 1.2 × 0.9 cm metastatic lymph node anterior to the inferior vena cava, a 3.3 × 1.3 cm lytic left acetabular lesion with tiny soft tissue mass laterally. Nuclear medicine (NM) bone scan did not show skeletal metastasis. Baseline laboratory studies were acquired to calculate her IMDC score. Relevant laboratory workup included a hemoglobin of 13.4 GM/dL, absolute neutrophil count of 7.6 k/cumm, platelet count of 288 k/cumm, lactated dehydrogenase of 172 units/L, albumin of 4.2 GM/dL, and calcium of 9.6 mg/dL. IMDC risk category was intermediate with two prognostic factors (time and absolute neutrophil count). She was started on axitinib 5 mg orally twice daily, pembrolizumab 200 mg every 3 weeks, and denosumab 120 mg for her bone lesion. Response to treatment was evident on repeat CT scans after the first month, fourth month, and eighth month of treatment. The sizes decreased to 4.4 × 5.4 cm, 4.1 × 3.9 cm, and 3.7 × 3.5 cm, respectively. The acetabular lesion remained stable in all repeat CT scans.

Fig. 1.

Pathology slide from biopsied thyroid gland and isthmus demonstrating metastatic clear cell renal carcinoma. Tumor cells can be seen in nests and sheets surrounded by an intricate meshwork of branching capillaries. H&E stain and ×2 magnification.

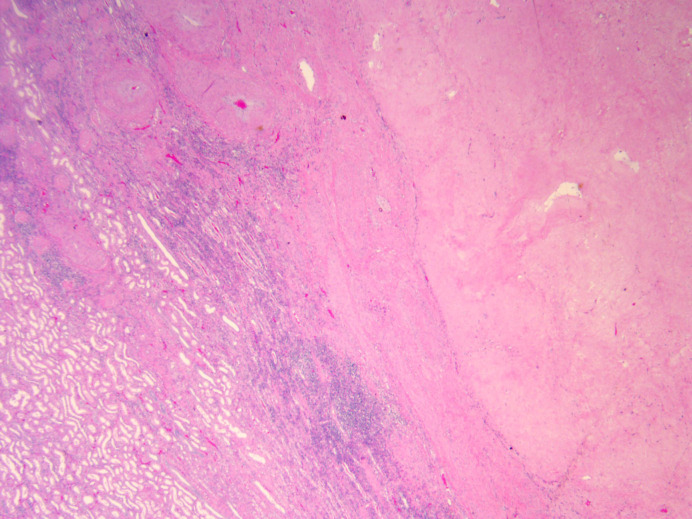

By the ninth month of treatment, she was experiencing side effects from axitinib, particularly fatigue, muscle aches, and elevated blood pressure at the time, so her dosage was decreased to 3 mg twice daily. Repeat CT scan 1 year after starting treatment showed a stable right renal mass and stable lytic lesion in the left acetabulum. Imaging with CT scan, magnetic resonance imaging, and NM bone scan did not show any evidence of metastasis. Given her PR and disease stability, she proceeded with cytoreductive right radical nephrectomy. Interestingly, the pathology report of the excised renal mass demonstrated a 4.5 × 4 cm scar with no viable tumor present (shown in Fig. 2) and one negative lymph node. Her pathologic staging was pT0 pN0 pM1. After surgery, she was taken off axitinib and was on her 14th dose of pembrolizumab. It is planned for her to continue monotherapy with pembrolizumab 200 mg every 3 weeks for a total of 35 cycles. Five months after surgery, repeat CT scan and NM bone scan showed no evidence of new lesions or metastasis, uncomplicated post-operative changes or no new lymphadenopathy. Of note, her labs remained stable throughout her course. To this date, she is doing well with no radiographic evidence of new lesions and no uptake on NM bone scan to suggest active disease. She is currently on her 26th cycle of pembrolizumab monotherapy.

Fig. 2.

Pathology slide from excised renal mass demonstrating fibroxanthomatous inflammation consistent with therapeutic effect on renal neoplasm and no viable cancer cells. ×2 magnification.

Conclusion

The most salient feature of this case includes the false residual radiographic evidence of primary tumor despite evidence of pathological CR. Tucker et al. [10] presented 2 cases and reviewed 5 other similar cases, all of which did not have a CR as per RECIST 1.1 despite having pathological CR. The role of CN has been unclear in the era of immunotherapy and targeted therapy. Our case challenges the benefit of undergoing CN as pathology was mainly composed of scar tissue which falsely portrayed persistent radiographic evidence of tumor.

Singla et al. [8] analyzed data from the national cancer database and found superior overall survival in CN combined with immunotherapy compared to immunotherapy alone. Most cases in the CN group had immediate CN, compared to a median of 4 months of immunotherapy before CN; only 2 cases in the latter group achieved pathological CR. As per the SURTIME trial [13], which compared immediate versus deferred CN, deferred CN did not improve the progression-free rate compared to immediate CN. However, deferred CN was at 3.6 months with no mention of pathology.

Interestingly, in our case and the cases presented by Tucker et al. [10], deferred CN was performed at an average of 11 months after starting treatment, highlighting the possibility of PR to treatment being an indicator to bear in mind when considering CN. In support of this, in the KEYNOTE-426 follow-up study [14], comparing pembrolizumab and axitinib versus sunitinib, a greater tumor size reduction was associated with an increased survivability probability. Also, in the pembrolizumab and axitinib arm, there was a similar overall survival rate in patients with confirmed CR based on the RECIST 1.1 and those with 80–100% tumor reduction. Moreover, the CARMENA trial [9] showed no additional benefits with immediate CN and that it may even be detrimental in patients with primary clear cell metastatic RCC who require Sunitinib. The trial also demonstrated a greater overall survival in intermediate- and poor-risk patients who only received Sunitinib.

Additionally, Keiichiro et al. [15] performed a systemic review and meta-analysis, deducing that CN provided limited benefit in patients who received combination immune checkpoint inhibitors based on similar hazard ratios in overall survival and progression-free survival. Although it is evident how unclear the role of CN is, the latest ASCO guidelines [16] recommend performing CN in select patients with a favorable or intermediate risk per IMDC who can have most of their tumor burden removed with surgery or for palliative reasons. Our patient had intermediate risk and underwent CN 1 year after starting combination immunotherapy with pathology showing no viable tumor and only scar tissue. Also, our patient is scheduled to receive 35 cycles of pembrolizumab, as was done in the initial KEYNOTE-426 study [17] and supported by the most recent KEYNOTE-564 update, which demonstrated better disease-free survival compared to placebo when receiving adjuvant therapy with pembrolizumab [18].

In conclusion, we present a patient with metastatic clear cell RCC who achieved pathologic CR with pembrolizumab and axitinib despite having incomplete radiographic response. Our case highlights the concept that in the current era of immunotherapy and tyrosine kinase inhibitors, the role of CN should be questioned. CN has its implications such as perioperative risks related to surgery itself and the degree of loss in renal function, which can lead to chronic kidney disease. It also reveals the need for more research with the endpoint being a pathologic CR, as CN may be unnecessary given that persistent radiographic evidence of a tumor can be due to scar tissue. The CARE checklist has been completed by the authors for this case report, attached as online supplementary material (for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000529124).

Statement of Ethics

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for the publication of this case report including any accompanying images. Ethical approval was not required to write this case report as the patient was not identified. This decision was made by the Ethical Review Committee at Ball Memorial Hospital.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

The authors have no funding sources to declare.

Author Contributions

Salahuddin Siddiqui saw the case and reviewed the manuscript. Amir F. Beirat wrote the manuscript. Sasmith Menakuru and Ibrahim Khan helped write the paper.

Funding Statement

The authors have no funding sources to declare.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1. Hofmann F, Hwang EC, Lam TB, Bex A, Yuan Y, Marconi LS, et al. Targeted therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;10(10):CD012796. 10.1002/14651858.CD012796.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Heng DYC, Xie W, Regan MM, Harshman LC, Bjarnason GA, Vaishampayan UN, et al. External validation and comparison with other models of the International Metastatic Renal-Cell Carcinoma Database Consortium prognostic model: a population-based study. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14(2):141–8. 10.1016/S1470-2045(12)70559-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Santoni M, Massari F, Bracarda S, Grande E, Matrana MR, Rizzo M, et al. Cabozantinib in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma primary refractory to first-line immunocombinations or tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Eur Urol Focus. 2022;86:1696–702. 10.1016/j.euf.2022.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Massari F, Mollica V, Rizzo A, Cosmai L, Rizzo M, Porta C. Safety evaluation of immune-based combinations in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2020;19(10):1329–38. 10.1080/14740338.2020.1811226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rizzo A, Mollica V, Santoni M, Massari F. Risk of selected gastrointestinal toxicities in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients treated with immuno-TKI combinations: a meta-analysis. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;15(10):1225–32. 10.1080/17474124.2021.1948328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, Schwartz LH, Sargent D, Ford R, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45(2):228–47. 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lichtbroun BJ, Srivastava A, Doppalapudi SK, Chua K, Singer EA. New paradigms for cytoreductive nephrectomy. Cancers. 2022;14(11):2660. 10.3390/cancers14112660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Singla N, Hutchinson RC, Ghandour RA, Freifeld Y, Fang D, Sagalowsky AI, et al. Improved survival after cytoreductive nephrectomy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma in the contemporary immunotherapy era: an analysis of the National Cancer Database. Urol Oncol. 2020;38(6):604.e9–17. 10.1016/j.urolonc.2020.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Méjean A, Ravaud A, Thezenas S, Colas S, Beauval J-B, Bensalah K, et al. Sunitinib alone or after nephrectomy in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379(5):417–27. 10.1056/NEJMoa1803675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Tucker MD, Beckermann KE, Gordetsky JB, Giannico GA, Davis NB, Rini BI. Complete pathologic responses with immunotherapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: case reports. Front Oncol. 2020;10:609235. 10.3389/fonc.2020.609235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shimizu K, Tamada S, Matsuoka Y, Go I, Okumura S, Ogawa M, et al. Pathologic complete response with pembrolizumab plus axitinib in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Int Cancer Conf J. 2022;11(3):205–9. 10.1007/s13691-022-00549-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Peak TC, Fenu EM, Rothberg MB, Thomas CY, Davis RL, Levine EA. Pathologic complete response to neoadjuvant nivolumab/ipilimumab in a patient with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Case Rep Urol. 2020;2020:8846135. 10.1155/2020/8846135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bex A, Mulders P, Jewett M, Wagstaff J, van Thienen JV, Blank CU, et al. Comparison of immediate vs deferred cytoreductive nephrectomy in patients with synchronous metastatic renal cell carcinoma receiving sunitinib: the SURTIME randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5(2):164–70. 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.5543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Powles T, Plimack ER, Soulières D, Waddell T, Stus V, Gafanov R, et al. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib monotherapy as first-line treatment of advanced renal cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-426): extended follow-up from a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21(12):1563–73. 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30436-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mori K, Quhal F, Yanagisawa T, Katayama S, Pradere B, Laukhtina E, et al. The effect of immune checkpoint inhibitor combination therapies in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients with and without previous cytoreductive nephrectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022;108:108720. 10.1016/j.intimp.2022.108720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Rathmell WK, Rumble RB, Van Veldhuizen PJ, Al-Ahmadie H, Emamekhoo H, Hauke RJ, et al. Management of metastatic clear cell renal cell carcinoma: ASCO guideline. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(25):2957–95. 10.1200/JCO.22.00868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rini BI, Plimack ER, Stus V, Gafanov R, Hawkins R, Nosov D, et al. Pembrolizumab plus axitinib versus sunitinib for advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(12):1116–27. 10.1056/NEJMoa1816714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Powles T, Tomczak P, Park SH, Venugopal B, Ferguson T, Symeonides SN, et al. Pembrolizumab versus placebo as post-nephrectomy adjuvant therapy for clear cell renal cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-564): 30-month follow-up analysis of a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23(9):1133–44. 10.1016/S1470-2045(22)00487-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article and its online supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.