Abstract

In the aftermath of the Supreme Court’s Dobbs vs. Jackson Women’s Health decision, acute care surgeons face an increased likelihood of seeing patients with complications from both self-managed abortions and forced pregnancy in underserved areas of reproductive and maternity care throughout the USA. Acute care surgeons have an ethical and legal duty to provide care to these patients, especially in obstetrics and gynecology deserts, which already exist in much of the country and are likely to be exacerbated by legislation banning abortion. Structural inequities lead to an over-representation of poor individuals and people of color among patients seeking abortion care, and it is imperative to make central the fact that people of color who can become pregnant will be disproportionately affected by this legislation in every respect. Acute care surgeons must take action to become aware of and trained to treat both the direct clinical complications and the extragestational consequences of reproductive injustice, while also using their collective voices to reaffirm the right to abortion as essential healthcare in the USA.

Keywords: health policy; Health Care Quality, Access, And Evaluation; Healthcare disparities; pregnancy

You are the acute care surgeon on call. The high-risk obstetrician has called you into their operating room to help with a life-threatening hemorrhage in a patient with placenta accreta presenting at 33 weeks. The patient is a 31-year-old woman with a history of two cesarean sections who presented to your hospital in class IV hemorrhagic shock. The patient was previously informed that placental implantation into her cesarean section scar could lead to life-threatening hemorrhage at the time of delivery. She has two children at home and did not wish to proceed with the pregnancy; however, abortion is illegal in her state. The patient had limited social support and financial resources to travel out of state for an abortion. Her contractions caused a catastrophic uterine rupture with massive hemorrhage requiring four massive transfusion protocols (MTPs) for resuscitation. A resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) was used while a hysterectomy was attempted. During the hysterectomy, the patient arrested. Despite heroic resuscitative efforts, the patient dies.

Introduction

Abortion is an essential healthcare.1 The Supreme Court’s overturning of Roe v. Wade by the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization decision in June 2022 has provoked rapid and diverse responses across the USA, with many implications. Twelve states have already enacted laws that essentially prohibit abortion, outside of very limited exceptions.2 Another 14 states have prepared legislation hostile to abortion, with laws written but not yet implemented including strict bans limiting abortions as early as 6 weeks after conception.3 Nearly 60% of people who can become pregnant—around 40 million—now find themselves in states hostile to abortion.4 Despite proclamations from politicians about the importance of protecting the legality of abortion, the right to seek a legal abortion has not been codified into federal law. Widespread hostility to abortion has shifted the landscape in ways that are increasingly pushing many pregnant people to turn to alternative means by which to obtain essential healthcare.

When conducted under safe conditions, abortion is an extremely effective and safe procedure. Unsafe abortions are defined by the WHO as “a procedure for terminating a pregnancy that is carried out either by persons lacking the necessary skills or in an environment that does not conform to minimum medical standards, or both.” Globally, unsafe abortions are a leading cause of maternal mortality and morbidity, stemming from hemorrhage, infection, sepsis, genital trauma, and necrotic bowel.5 Restricting a woman’s access to abortion does not prevent abortion but simply leads to more unsafe abortions.6 Abortions can be procedural or medical, with the latter referring to abortion by medication, which is the most common form of pregnancy termination in the USA in 2022. As the ability to obtain an abortion becomes more challenging in many states, self-managed abortions (SMAs) are likely to increase. SMAs are defined as activities undertaken to end a pregnancy that take place outside of a formal healthcare setting.7 In the USA, SMAs are most commonly performed using medications that have low overall complication rates.8

Acute care surgeons face an increased likelihood of seeing patients with complications from both SMAs and forced pregnancy, especially in underserved areas of reproductive and maternity care throughout the USA, such as the case of our 31-year-old patient. Given the overall safety of SMAs, acute care surgeons will more commonly be tasked to manage complications in patients forced to continue a pregnancy to delivery, against the patient’s will. Acute care surgeons have an ethical and legal duty to provide care to these patients, especially in “obstetrician and gynecology (OB/GYN) deserts,” which already exist in much of the country and are likely to be exacerbated by legislation banning abortion.

This article will discuss how acute care surgeons can treat the complications of SMAs, both medical and procedural. We will also address the effects of and complications stemming from forced pregnancy that are a direct effect of changing laws, impacting all physicians and society broadly. We think that the Dobbs decision will be incredibly harmful to our patients, their families, communities, and even surgeons, and should be denounced by the profession.

Background

Abortion is very common in the USA. This article focuses on induced abortion, which is experienced by one in four people who can become pregnant during their reproductive years.9 For the purposes of this article, we will refer to induced abortions as “abortions.” Spontaneous abortion, often referred to as “miscarriage,” is also common, being experienced by up to 40% or more of people who have been pregnant.10 Medical and surgical management of both induced and spontaneous abortions is identical. Nearly 50% of people experiencing spontaneous abortions will receive a dilation and curettage (D&C), a procedure also used for induced abortion.11 Although state abortion bans target induced abortion, confusion around these laws and how they are to be interpreted and applied in clinical practice also impacts access to management of spontaneous abortion.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) latest reporting on national abortions in 2019 found that 53% of abortions in the USA before 9 weeks of gestation are early medical abortions, and this number has certainly increased and will continue to increase in the post-Roe era.12 13 Despite the very low rate of serious complications (0.4%) associated with medical abortions, this shift in primary methods of abortions is changing the landscape of healthcare in the USA and necessitates better training for all physicians to recognize the challenges and complications from these procedures.8 Passing of legislation which restricts access to abortions leads to an increase in abortions sought at later gestational ages, leading to concern for greater complications associated with abortions at later gestational ages.14 For those who would have sought abortion pre-Dobbs but will be forced to carry a pregnancy, there may be extensive health complications in addition to social and economic hardships.

The consequences of the Dobbs ruling are even more dire when considering the fact that the USA has the highest maternal mortality rate among high-income countries.15 Unplanned pregnancies carry even greater risks of morbidity and mortality than planned pregnancies, and many states that have banned abortion already have less access to obstetric care and higher rates of maternal mortality.16 17 The USA can also be a dangerous place to raise a child for our most vulnerable patients; it fails to provide universal healthcare, childcare, or paid family leave, and lacks equitable access to contraception.18 Pregnancies that are continued through delivery in the USA face complication and death rates that far exceed these risks for legal abortion.12

It is essential to note that due to structural barriers to equitable healthcare, black individuals are at the greatest risk of being impacted by the overturning of Roe. CDC data show that black and Indigenous people are two to four times as likely as white people to die during pregnancy or around the time of childbirth.19 Abortion, which is now criminalized in many US communities, is safer than pregnancy and delivery, especially for black and Indigenous people. For example, in Mississippi, a black person is 118 times more likely to die from carrying a pregnancy to term than from having a legal abortion, and black women are also at three times higher risk of experiencing negative health outcomes in pregnancy.19 20 Therefore, this is an issue of structural racism, leading to direct harm to pregnant people who are already marginalized. The Dobbs decision is just one of the many examples of laws in the USA whose effects contribute to the death of people of color who can become pregnant, making this also an issue of civil and human rights. The harms imposed by banning or severely restricting abortion access will disproportionately affect persons of color and perpetuate structural racism.21 The criminalization of abortion is part of a long history of maintaining reproductive control of black and socially marginalized lives.22 For other vulnerable populations, mass incarceration has become a driver of forms of reproductive oppression for people in prison and jails and in the community, undermining the core values of reproductive justice.23 Irony lies in the fact that these two realities coexisted pre-Roe and will continue to pre-empt reproductive justice for racial minorities in the post-Dobbs society.

Medically managed abortions are safe and are taking place across state lines

One major difference from the pre-Roe era, when the legality of a person’s right to obtain a legal abortion was left to the states, to today is that medication abortion is now widely available. In addition to being extremely safe, the wider availability of medication abortion without direct mediation by physicians enhances equitable access to this care to patients. For these patients, legal, geographic, family, or financial obstructions to medical mediation present obstacles to receipt of care. By supporting the institutional demedicalization of abortion, the medical profession can contribute to making medication abortion more easily accessible, such as via mail order, to individuals in states seeking to obstruct their access to care.24

The most common medications to induce abortion include mifepristone and/or misoprostol. Medical abortions, when prescribed by a qualified provider, are roughly 14 times safer than pregnancy itself.25 It is unlikely that acute care services will be needed for complications of these abortions; in most instances, patients presenting to physicians after medication abortion will present in search of pain management or confirmation that the abortion was completed.26 In the case that these patients present in states where abortion is illegal, it is imperative to protect the privacy of the patient and treat the medical issue at hand without allowing intrusive criminal legal systems to impose on patient care.

Complications that may be encountered with SMAs

Unfortunately, despite the availability of medication abortion and the preservation of abortion care in many states, there are now many people who will become pregnant and have limited access to comprehensive reproductive healthcare. Due to restricted access to safer options, some pregnant people will ultimately seek SMA by procedural abortions in unregulated, unsafe settings, by ingestion of toxic substances or by self-inflicted physical injury.27 Depending on their location and state laws regarding abortion access, trauma and acute care surgeons may find themselves providing care for people impacted by the Dobbs ruling who undergo SMA and suffer injury as a result. While we should strive to prevent such injury by advocating for the protection of access to safe abortion care, surgeons should also prepare to treat resulting complications. To this end, healthcare providers should become better informed about the various methods of SMA and their potential medical and surgical complications.

In circumstances of SMA by ingestion of substances or use of medication that is not standard of care for medication abortion, patients may present with infections due to retained fetal structures, incomplete abortions, and hemorrhage. This treatment can include D&C to remove retained products of conception, antibiotics, and replacement of blood products.26 Management of these patients requires rapid, non-judgmental, evidence-based care.

Surgical abortion is incredibly safe when abortion is legal.25 However, complications from procedural abortions can occur both when performed in medical settings and outside of the medical system. Complications from procedural abortions can overlap with those of medical abortions, primarily hemorrhage and infection related to retained products of conception. In addition to and even less common than these complications, procedural abortion can result in uterine perforation with concomitant injury to surrounding structures including the bowel, bladder, and vasculature requiring surgical management. Less commonly, providers may see individuals with self-induced abdominal trauma, which carries another set of complications similar to those of other blunt traumatic injuries to the abdomen and uterus specifically. In these situations, it is important to provide the standard of evidence-based, trauma care, with particular emphasis on non-judgmental treatment. The patient’s legal safety should also be of utmost concern and underscores the significance of knowing your state laws around this issue. Providers have the ethical duty to protect patient privacy and to not report these complications which implicate self-induced abortion to law enforcement in states where this is prohibited.

Complications of forced pregnancy

Pregnancy should not be considered a pathological state. However, because pregnancy itself carries far greater health risks than legal abortions, especially given the high maternal mortality and morbidity rates in the USA, acute care surgeons will more often face patients with health complications of forced pregnancy. These complications may be diverse. Most acutely, those that cause maternal mortality and must be addressed emergently include hemorrhage, eclampsia, obstructed labor, and sepsis.28 Physicians will also face morbidities that may progress to acute or emergent issues, including gestational diabetes, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, thromboses, and anemia.29 Again, in those states that restrict access to abortion care, maternal morbidity, and inevitably mortality, will increase and require physicians from all fields to expand their ability to care for these needs.

It is no coincidence that patient populations seeking both abortion services and trauma care often include a disproportionate share of marginalized individuals, including people of color and of low socioeconomic status. Accordingly, those involved in trauma and acute care will have even more frequent opportunities to influence the care of disadvantaged groups facing forced pregnancy in the aftermath of Roe reversal.30–32 Beyond the clinical realm, physicians must understand the widespread socioeconomic implications of denying people abortions and take opportunities to connect people facing forced pregnancy with resources when available. People denied abortions have significantly higher odds of living in poverty in the years after the pregnancy compared with people able to access this care.22 27 Not only are disadvantaged groups over-represented among people seeking abortion care due to structural racism and socioeconomic injustice, their marginalization will be directly exacerbated by the Dobbs ruling which imposes further burdens on their ability to thrive.

Structural inequities and barriers to care also lead to twofold to threefold higher rates of unintended pregnancy among individuals with a history of or who are currently experiencing gender-based violence.33 This implies that the infliction of forced pregnancy by the Dobbs ruling will be disproportionately experienced by those with a history of intimate partner violence and likely lead to an increase in physical trauma. Pregnant people experiencing intimate partner violence are also more likely to have insufficient or inconsistent prenatal care, in addition to substance use in pregnancy.34 Forced pregnancy compounds the violations of safety for these people who can become pregnant and the children they carry. Intimate partner violence is a risk factor for intimate partner homicide, with pregnant pediatric patients at higher risk in one single-center study.35 36

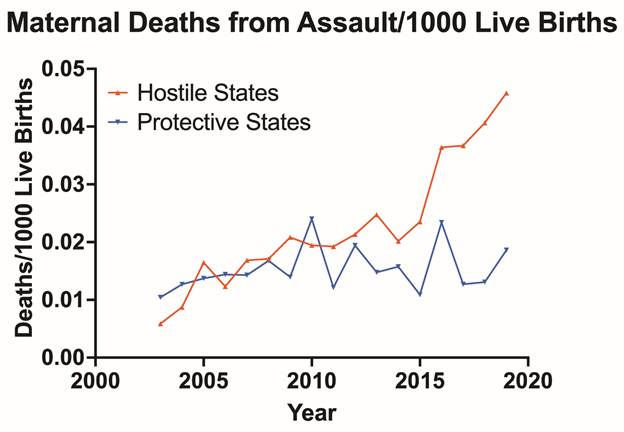

When maternal mortality data are compared between states with legislation restricting abortion and those that protect access to abortion care, there has been a dramatic increase in maternal mortality in states where abortion is restricted during the last two decades that has affected people of all races/ethnicities who can become pregnant, but has disproportionately affected black and Indigenous patients.37 Although the data do not prove abortion restriction itself is causative, they demonstrate a major divergence between these states that was not present before the legislative changes that followed the Planned Parenthood v. Casey decision, which allowed for the passage of myriad abortion restrictions in the 2000s. This turning point also aligns with the erosion of safety net services and decrease in the total number of clinics and prenatal services available to patients. It may also reflect legislative priorities at odds with the needs of pregnant persons. When mortality data are further interrogated to examine what causes of maternal death are increasing in these states, all causes/codes of maternal mortality have increased, suggesting pregnancy for all individuals has become less safe. Of note to physicians treating trauma patients, a dramatic and worsening mortality is seen in pregnant patients from violence by assault that is not seen in states with protective legislation (figure 1). Consequently, legislative decisions in these states will lead to increased death of pregnant patients from external violence as well as from physical complications of forced pregnancy. Although abortion laws are not the only reason that death by physical harm is much higher in states with these restrictions, hostility to the right to choose is an important metric to measure general health and safety for people who can become pregnant in this country.

Figure 1.

States were determined to be restrictive or protective of abortion based on the Alan Guttmacher Institute criteria as previously described.37 The CDC Wide-ranging ONline Data for Epidemiologic Research (WONDER) was queried for the years 1999–2019 for multiple causes of death with assault (X85–Y09) and/or intentional self-harm (X60–X84) as the underlying cause of death in women ages 10–54 and obstetric codes (O00–O99) as contributing for each subset of states. For the years when the CDC suppressed the value due to low numbers (< 10 /year), the highest possible suppressed value of “9” was entered as the high end of possible deaths. The rate was calculated against the listed population in that age group at that time and then also normalized against the number of live births in the included states (CDC) for that year. The pregnancy “check box” was notably added to all state death certificates during the years 2003–2017 (most states completed addition by 2010) allowing for greater sensitivity for detection of maternal death since ~2003; however, in previous reverse binomial regression analyses, state addition of the check box did not significantly correlate in time with increases seen in maternal mortality between the states.37 CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The Turnaway Study is a longitudinal prospective cohort study that followed individuals who were or were not able to obtain a desired termination due to being above the gestational age limit of the clinic where they had sought care. The study demonstrated that those unable to obtain their desired abortion were more likely to stay with an abusive partners.38 The same study demonstrated negative outcomes in mental health and aspirational life plans in those who were denied abortions. Studies also suggest long-term negative effects on children born from forced pregnancy, who have lower mean development scores than children born of intended pregnancies.39

Extragestational implications of the Dobbs ruling

The decrease in abortion access across the USA will have repercussions on an educational level. As nearly half of the nation’s medical residents in OB/GYN are certain or likely to lack access to instate abortion training, they will also lose the technical skill set of assisting women after miscarriages. This threatens programs as accreditation rules, according to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), require OB/GYN medical residencies to provide training or access to training on the provision of abortions.40 Furthermore, many complex family planning fellowships in OB/GYN will experience limitations in what can be taught in clinical practice. This can lead to the dissolution of the entire highly specialized fellowship programs in states with complete abortion bans. This will lead to the loss of a surgical knowledge base and matching surgical technical skills that will be difficult to recuperate. The loss of such fellowship programs will impact OB/GYN residency programs as highly trained faculty will migrate to states supportive of their surgical skill set. These training implications have the potential to create an ‘OB/GYN brain drain’ as recruitment of talent ends and programs dissolve in states hostile to reproductive rights, further compounding reproductive care for women.

The potential threat to OB/GYN residency accreditation and the subsequent loss of entire OB/GYN programs in academic centers has significant implications for trauma centers across the country. For level I trauma center verification with the American College of Surgeons’ Committee on Trauma (Clarification Document 11–70), “Level I facilities are prepared to manage the most complex trauma patients and must have available a full spectrum of surgical specialists, including specialists in…obstetrics and gynecology.” In fact, both level I and II trauma centers are required to develop guidelines with a plan of care for the mother and the unborn child, including impending delivery with the incorporation of obstetricians and the neonatal intensive care unit as part of the trauma team. As obstetrical, gynecological and neonatal supports disappear from hospitals, so will their accompanying level I and II trauma centers, directly impacting the care we provide to our communities affected by trauma.41

The majority of acute care surgeons and residents in surgical specialty tend to delay pregnancy and thus experience difficulty with reproductive choices later in life. Female surgeons have three times higher rate of infertility compared with the general population (30%–32% vs. 11%), and a close to five to eight times higher rates of assisted reproductive technology (8%–13% vs. 1.7%). Even with reproductive technology and advances available, their fertility is not certain, placing significant financial and psychosocial issues to overcome. Strict abortion restrictions have implications in the handling, transferring, preservation processes, and genetic testing of embryos, a foundation for reproductive medical centers. Similarly, access to professionals trained in reproductive endocrinology will be increasingly difficult in such states, in addition to the hesitancy faced by the physician. Pregnant surgical residents experience a high rate of obstetrical complications, especially when working more than six overnight call shifts per month or 60 hours per week.42 Taking this into consideration, it should be noted that most surgical programs have an expectation of ~80 hours per week, only increasing the risk of obstetrical complications, potentially in states where residents may not have access to abortion to terminate complicated pregnancies.

Women of reproductive ages experience a variety of medical conditions, including endometriosis polycystic ovarian syndrome, which require access to multiple essential medications with abortifacient properties. Effective symptom control of autoimmune diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus relies on access to methotrexate for debilitating symptoms and pain control. Pharmacists in states such as Texas are legally emboldened to refuse prescription refills for fear of committing felony, should the medication instead be used for an SMA. This is affecting pediatric populations with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis as methotrexate is considered critical to disease remission and significantly improved quality of life with adequate pain control.43 Methotrexate is also used for treatment of inflammatory bowel disease and a variety of cancers, including breast cancer, lymphoma, leukemia, and lung cancer.

The broader access to civil rights and protection of bodily autonomy is also under threat after Dobbs, ranging from access to voting rights, digital protection rights, interracial marriage, and LGBTQ+ rights, which cannot be ignored. These extrareproductive civil rights issues compound the legislative interference in the practice of medicine and bodily autonomy for both the patient and the provider, generating an erosion of overall human rights in the USA. As one in five men are involved in an abortion in the USA, the profoundly detrimental social and financial effects of forced pregnancy already described here about pregnant people will also be experienced by men involved in pregnancy, and cannot be overlooked.44 45

How acute care surgeons and other non-OB/GYN providers can support

It is now imperative that all healthcare providers become educated in and prepared to care for individuals who can become pregnant as they may experience health complications as a direct result of their inability to access safe abortion care. At baseline, it is essential for physicians to understand the current laws in their respective state. Beyond just knowing whether abortion is legal, it is important to recognize whether traveling out of the state for abortion care is lawful and what exceptions, if any, exist for individuals who are pregnant and seeking an abortion. Even in states where abortion is still permissible, there may be different parameters for patients before and after viability of the fetus. It is also critical that all providers discuss the legal limitations of caring for patients affected by Dobbs with inhouse legal counsel.

There are several ways that physicians can show allyship toward their OB/GYN colleagues. From a logistical standpoint, an influx of abortion services may be required at some institutions residing in states where abortions are legal. In this way, operating room leadership can proactively work with the OB/GYN service to provide contingency plans for emergency operating room time and assistance in tracking and understanding the trends in that community. In addition, there may be local, state, or national organizations that you can support that will provide the much-needed resources to your colleagues’ patients. We are at the early stages of this new era in abortion care. The simple gesture of reaching out and offering your support can go a long way and at the very least will start to provide open lines of communications should the needs of this patient population increase over time. Physicians must also uphold their responsibilities as a citizen to vote as individuals to impact political representation, and to use their voices to destigmatize the abortion experience and normalize reproductive justice in broader society.

Call to action

The impact of the Dobbs decision on acute care surgeons goes beyond the clinical complications faced in the hospital setting. Of OB/GYN residencies, 44% are in states that have or plan to restrict abortions in the aftermath of Dobbs.46 Training for dealing with obstetric emergencies will be incredibly limited in these states. This lack of procedural knowledge will be compounded by the creation of “obstetric deserts” in these states, as these bans will almost certainly lead to a decrease in academic talent in training programs. The loss of OB/GYN residents may lead to a manpower shortage in hospitals, which will directly affect the accreditation of trauma centers across the USA, where having an OB/GYN on call is required for level I trauma center status.

The fact that the USA has not ratified the United Nations language on reproductive rights renders the right to an abortion an issue of individual parties to take a stand. All physicians, including trauma and acute care surgeons, play a role in the care of people who can become pregnant and all physicians will be impacted by the consequences of this ruling. One way for the field to take a stand is for professional trauma and surgical organizations to call for the USA to ratify the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, the International Human Rights Treaty which requires all nation-states to provide reproductive healthcare services in adequate numbers, and that these services should be of good quality and accessible without discrimination.

Surgeons and all medical providers will increasingly face the important question of protecting patient privacy in the treatment of people who are pregnant. Professional medical organizations should also provide formal guidance on these situations so that providers may feel comfortable in protecting the health of their patients within the bounds of legal restrictions to avoid repercussions.

Structural inequities lead to an over-representation of poor individuals and people of color among both trauma survivors and patients seeking abortion care. Therefore, it is imperative to make central the fact that people of color who can become pregnant will be disproportionately affected by this legislation in every respect, and statements and actions that address the Dobbs legislation must acknowledge and work to combat these disparities. As medical providers and responsible citizens of a society that fails to equitably care for its most vulnerable, we must act to prevent harm both in our medical practice and with our voices.

Footnotes

Contributors: All persons who meet the authorship criteria are listed as authors and certify that they have participated sufficiently in the work. The authors have taken responsibility for the content and have participated in the concept, design, analysis, writing, or revision of the manuscript. GK, along with MF, JC, and TZ, contributed to the concept, design, and writing of the manuscript. KC, LH, MN, MHo, and RE also participated in the writing and figure development. NB, HM, CD, VK, MLC, and EK contributed to the revisions of the manuscript. MHe, MZ, and GK all contributed to the concept and revisions.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.Abortion Is Essential Health Care . https://www.acog.org/en/advocacy/abortion-is-essential (26 Oct 2022).

- 2.State legislation tracker . Guttmacher Institute. 2021. https://www.guttmacher.org/state-policy (11 Oct 2022).

- 3.Abortion Laws by State . Center for Reproductive Rights. https://reproductiverights.org/maps/abortion-laws-by-state/ (11 Oct 2022).

- 4.58% of U.S. women of reproductive age—40 million women—live in states hostile to abortion rights . Guttmacher Institute. 2021. https://www.guttmacher.org/infographic/2021/58-us-women-reproductive-age-40-million-women-live-states-hostile-abortion-rights-0 (11 Oct 2022).

- 5.Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2008 . https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241501118 (11 Oct 2022).

- 6.Cameron S. Recent advances in improving the effectiveness and reducing the complications of abortion. F1000Res 2018;7:1881. [Epub ahead of print: 02 12 2018]. 10.12688/f1000research.15441.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Safety and effectiveness of self-managed medication abortion provided using online telemedicine in the United States: A population based study . The Lancet Regional Health – Americas. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lanam/article/PIIS2667-193X(22)00017-5/fulltext (11 Oct 2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Raymond EG, Shannon C, Weaver MA, Winikoff B. First-Trimester medical abortion with mifepristone 200 Mg and misoprostol: a systematic review. Contraception 2013;87:26–37. 10.1016/j.contraception.2012.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Population Group Abortion Rates and Lifetime Incidence of Abortion: United States, 2008–2014 . Guttmacher Institute. 2017. https://www.guttmacher.org/article/2017/10/population-group-abortion-rates-and-lifetime-incidence-abortion-united-states-2008 (11 Oct 2022).

- 10.Spontaneous first trimester miscarriage rates per woman among parous women with 1 or more pregnancies of 24 weeks or more . PMC. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5741961/ (11 Oct 2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Procedure After a Miscarriage . American Pregnancy Association. 2017. https://americanpregnancy.org/healthy-pregnancy/pregnancy-complications/d-and-c-procedure-after-miscarriage/ (24 Nov 2022).

- 12.Abortion Surveillance — United States, 2019 . MMWR. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/ss/ss7009a1.htm (11 Oct 2022).

- 13.How the repeal of Roe v. Wade will affect training in abortion and reproductive health . AAMC. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/how-repeal-roe-v-wade-will-affect-training-abortion-and-reproductive-health (11 Oct 2022).

- 14.Bhardwaj NR, Murray-Krezan C, Carr S, Krashin JW, Singh RH, Gonzales AL, Espey E. Traveling for rights: abortion trends in New Mexico after passage of restrictive Texas legislation. Contraception 2020;102:115–8. 10.1016/j.contraception.2020.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maternal Mortality Maternity Care US Compared 10 Other Countries . Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/nov/maternal-mortality-maternity-care-us-compared-10-countries (11 Oct 2022).

- 16.Moaddab A, Dildy GA, Brown HL, Bateni ZH, Belfort MA, Sangi-Haghpeykar H, Clark SL. Health care disparity and pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2005-2014. Obstet Gynecol 2018;131:707–12. 10.1097/AOG.0000000000002534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Findings State Rankings | 2018 Annual Report . America’s Health Rankings. https://www.americashealthrankings.org/learn/reports/2018-annual-report/findings-state-rankings (11 Oct 2022).

- 18.Kreitzer RJ, Smith CW, Kane KA, Saunders TM. Affordable but inaccessible? contraception Deserts in the US states. J Health Polit Policy Law 2021;46:277–304 https://read.dukeupress.edu/jhppl/article/46/2/277/166722/Affordable-but-Inaccessible-Contraception-Deserts. 10.1215/03616878-8802186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maternal Mortality Rates in the United States, 2020 . 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/hestat/maternal-mortality/2020/maternal-mortality-rates-2020.htm (11 Oct 2022).

- 20.What are the Implications of the Overturning of Roe v. Wade for Racial Disparities? KFF. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/what-are-the-implications-of-the-overturning-of-roe-v-wade-for-racial-disparities/ (11 Oct 2022).

- 21.Paltrow LM, Harris LH, Marshall MF. Beyond Abortion: The Consequences of Overturning Roe. Am J Bioeth 2022;22:3–15. 10.1080/15265161.2022.2075965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riley T, Zia Y, Samari G, Sharif MZ. Abortion Criminalization: a public health crisis rooted in white Supremacy. Am J Public Health 2022;112:1662–7. 10.2105/AJPH.2022.307014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hayes CM, Sufrin C, Perritt JB. Reproductive justice disrupted: mass incarceration as a driver of reproductive Oppression. Am J Public Health 2020;110:S21–4. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.For abortion care, physicians may need to step aside to support patients . STAT. 2021. https://www.statnews.com/2021/10/01/medication-abortion-clinicians-relinquish-gatekeeper-role/ (11 Oct 2022).

- 25.Raymond EG, Grimes DA. The comparative safety of legal induced abortion and childbirth in the United States. Obstet Gynecol 2012;119:215–9. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823fe923 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Complications of Unsafe and Self-Managed Abortion . NEJM. https://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMra1908412 (11 Oct 2022). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Ralph L, Foster DG, Raifman S, Biggs MA, Samari G, Upadhyay U, Gerdts C, Grossman D. Prevalence of Self-Managed abortion among women of reproductive age in the United States. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2029245. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.29245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nour NM. An introduction to maternal mortality. Rev Obstet Gynecol 2008;1:77–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.What are examples and causes of maternal morbidity and mortality? | NICHD . Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/health/topics/maternal-morbidity-mortality/conditioninfo/causes (11 Oct 2022).

- 30.Sonfield A, Kost K. Public Costs from Unintended Pregnancies and the Role of Public Insurance Programs in Paying for Pregnancy-Related Care: National and State Estimates for 2010. 2015. https://www.guttmacher.org/report/public-costs-unintended-pregnancies-and-role-public-insurance-programs-paying-pregnancy (11 Oct 2022).

- 31.Jones K, Bernstein A. The Economic Effects of Abortion Access: A Review of the Evidence (Fact Sheet). IWPR. 2019. https://iwpr.org/iwpr-issues/reproductive-health/the-economic-effects-of-abortion-access-a-review-of-the-evidence-fact-sheet/ (11 Oct 2022).

- 32.Costs of Reproductive Health Restrictions . IWPR. https://iwpr.org/costs-of-reproductive-health-restrictions/ (11 Oct 2022).

- 33.Miller E, Silverman JG. Reproductive coercion and partner violence: implications for clinical assessment of unintended pregnancy. Expert Rev Obstet Gynecol 2010;5:511–5. 10.1586/eog.10.44 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alhusen JL, Ray E, Sharps P, Bullock L. Intimate partner violence during pregnancy: maternal and neonatal outcomes. J Womens Health 2015;24:100–6. 10.1089/jwh.2014.4872 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Velopulos CG, Carmichael H, Zakrison TL, Crandall M. Comparison of male and female victims of intimate partner homicide and bidirectionality-an analysis of the National violent death reporting system. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2019;87:331–6. 10.1097/TA.0000000000002276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zakrison TL, Ruiz X, Namias N, Crandall M. A 20-year review of pediatric pregnant trauma from a level I trauma center. Am J Surg 2017;214:596–8. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Addante AN, Eisenberg DL, Valentine MC, Leonard J, Maddox KEJ, Hoofnagle MH. The association between state-level abortion restrictions and maternal mortality in the United States, 1995-2017. Contraception 2021;104:496–501. 10.1016/j.contraception.2021.03.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.The Turnaway Study . ANSIRH. https://www.ansirh.org/research/ongoing/turnaway-study (11 Oct 2022).

- 39.Foster DG, Raifman SE, Gipson JD, Rocca CH, Biggs MA. Effects of carrying an unwanted pregnancy to term on women's existing children. J Pediatr 2019;205:183–9. 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.09.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education . ACGME. https://www.acgme.org/what-we-do/accreditation/review-and-comment/ (26 Oct 2022).

- 41.VRC SFAQsACS. https://www.facs.org/quality-programs/trauma/quality/verification-review-and-consultation-program/trauma-verification-faqs/vrc-standards-faqs/ (11 Oct 2022).

- 42.Todd AR, Cawthorn TR, Temple-Oberle C. Pregnancy and parenthood remain challenging during surgical residency: a systematic review. Acad Med 2020;95:1607–15. 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mahase E. Us anti-abortion laws may restrict access to vital drug for autoimmune diseases, patient groups warn. BMJ 2022;378:o1677. 10.1136/bmj.o1677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li VM, Heyrana KJ, Nguyen BT. Discrepant abortion reporting by interview methodology among men from the United States national survey of family growth (2015-2017). Contraception 2022;112:111–5. 10.1016/j.contraception.2022.01.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Everett BG, Myers K, Sanders JN, Turok DK. Male abortion beneficiaries: exploring the long-term educational and economic associations of abortion among men who report teen pregnancy. J Adolesc Health 2019;65:520–6. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.05.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Projected Implications of Overturning Roe v Wade on Abortion . Obstetrics & Gynecology. https://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Fulltext/2022/08000/Projected_Implications_of_Overturning_Roe_v_Wade.3.aspx (11 Oct 2022). [DOI] [PubMed]