ABSTRACT.

Current control measures of canine visceral leishmaniasis (CVL), a chronic and fatal zoonosis with potential transmission to humans, are not efficient enough to reduce its spread. The search for improved control measures should include studies of risk factors for infection and illness. This study aimed to identify the risk factors for CVL in an endemic locality of the Federal District, Brazil, from June 2016 to December 2018. Biologic samples and data on dog characteristics, owner household characteristics, and dog care were collected. A combination of serological and molecular tests was used to identify infected animals. The 248 dogs screened for inclusion were predominantly asymptomatic/oligosymptomatic. The baseline prevalence of infection was 27.5%. One hundred six of 162 susceptible dogs were monitored for an average period of 10.7 months. The estimated CVL incidence was 1.91 cases/100 dog-months. The multivariate analysis using a proportional Cox model included the potential risk factors, with P ≤ 0.25 in the univariate analyses. Greater purchasing power (hazard ratio [HR], 1.04; 95% CI, 1.01–1.06; P = 0.03) and paved yard (HR, 0.19; 95% CI, 0.13–1.01; P = 0.05) remained in the final model as risk and protection factors, respectively. The use of repellent collars in dogs was associated moderately (P = 0.08) with protection against CVL. Our findings reflect the challenge of identifying strong interventions for reducing CVL incidence. Increased owner wealth had a counterintuitive effect on CVL, making the intervention scenario more complex for a zoonosis traditionally associated with poverty.

INTRODUCTION

Human visceral leishmaniasis (HVL) is a chronic, potentially fatal disease that is endemic in more than 78 countries, with approximately 50,000 to 90,000 new cases reported each year.1 In the Americas, visceral leishmaniasis (VL) is caused by infection with the protozoan Leishmania infantum, which is transmitted through the bite of female sandflies, mainly Lutzomyia longipalpis and, to a lesser extent, Lutzomyia cruzi.2,3 In Brazil, 19,053 HVL cases and 1,436 HVL-related deaths were reported from 2014 to 2018, resulting in a lethality rate of 7.5%.4

Dogs are also susceptible to L. infantum infection and are considered the main urban reservoirs of VL.5 Infection control in dogs in Brazil has been challenging.6,7 The Brazilian government uses the strategy of testing and euthanizing seroreactive dogs8—a widely questioned measure because of its ethical considerations, rejection by the population, and low effectiveness.5,9–11

Thus, further knowledge of risk factors is required to identify which canine populations are more vulnerable to canine VL (CVL). Some risk factors such as short hair, breed, and living near green areas have been identified as factors associated with CVL.12 However, few studies have explored guardian-related characteristics, such as dog care attitude and socioeconomic context, as risk factors. Poor housing conditions and lower income are closely associated with HVL13; therefore, these factors have been expected to affect the canine population similarly. But, contrary to expectations, our cross-sectional study conducted in the Federal District, Brazil, reported a greater income associated with CVL infections.14

A cohort study could contribute to a better understanding of previous findings, but observational cohort studies on dogs, such as those by Coura-Vital et al.15 and Lopes et al.,16 are scarce, mainly because of their laborious execution and high cost. Such studies offer a more appropriate methodological design to identify risk factors. To explore further the previously described result, we conducted a cohort study aimed to investigate risk factors for L. infantum infection in dogs from an endemic area for VL in the Federal District, Brazil, by analyzing the socioeconomic status of the animals’ guardians.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design.

This prospective, open cohort study, performed between June 2016 and December 2018, analyzed dogs living in two residential sectors of Sobradinho II, which is part of an endemic area for CVL in the Federal District, Brazil. These residential sectors are located near areas of Cerrado’s native forests, as can be seen in a satellite image in Supplemental Figure S1. Clinical and laboratory follow-up of the dogs was performed every 6 months, including collection of biologic material for diagnosis. Animals were recruited continually throughout the study, except for the last 5 months of 2018 because the minimum follow-up time was 6 months. During the first contact with the guardians, a questionnaire on socioeconomic status, dog care, environment in which the dog lived, and whether the owners had received visits from environmental surveillance was administered, as described by Teixeira et al.,14 with modifications (Supplemental File S1). The health status and biologic characteristics of the dogs were assessed using a form in which a clinical score was assigned to the dogs, according to Teixeira et al.14 A score ≤ 1 point indicated an asymptomatic dog; the greater the presence and intensity of clinical signs, the greater the score. The measured outcome was Leishmania infection, and positive cases were defined by parasite DNA detected in the peripheral blood sample using quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) or reactivity on both the Biomanguinhos Rapid Dual Patch Platform Test (TR-DPP) and Biomanguinhos Enzyme Immunoassay (EIE-LVC) serological tests (Biomanguinhos, FioCruz, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil).

Study location, population, and sampling.

The study was performed in two neighboring localities with an enzootic history and autochthonous HVL record. The localities of Serra Azul and Vila Rabelo comprise 9,688 inhabitants.17 The canine population in the region is estimated at one fourth of the human population, totaling 2,422 dogs.18

The sample size was calculated using Epi Info software (version 7.2.1), with definitions obtained from data from a cross-sectional study previously conducted in the region14: 95% CI, 80% power, unexposed/exposed ratio of 5.34, percentage of outcome in the unexposed group of 8.13%, and a risk ratio of 3. The classification of purchasing power was considered to calculate the sample size; classes A, B1, B2, and C1 (average household income > BRL 2,705.00) were included in the nonexposed group; classes C2, D, and E (average household income < BRL 2,705.00) were included in the exposed group. Considering an additional 10% loss, the final sample size was estimated at 235 dogs. Sampling was performed consecutively in all streets of the localities to include two houses per street. All eligible dogs by the inclusion criteria present in each house at the time of the initial approach were included in the study and tested.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The inclusion criteria were dogs who lived in the sample area and a signed informed consent from the guardian. If the guardian was unreachable after three visiting attempts on different days, their dogs were excluded from the cohort. To be eligible for the cohort study, the dog also had to be negative for Leishmania infection on all three diagnostic tests (TR-DPP, EIE-LVC, and qPCR) and older than 4 months. Aggressive dogs were excluded.

Diagnostic tests.

Two venous blood samples were collected in the field and transported in refrigerated transport boxes. One sample was used for the serological diagnosis of CVL using the TR-DPP and LVC-EIE according to manufacturer’s instructions. Serological diagnosis was performed at the Environmental Surveillance Directorate of the Federal District by a qualified technician who was unaware of the clinical and environmental information of the animals at the time of testing.

The second whole-blood sample was subjected to DNA extraction, and genetic material integrity was assessed by conventional β-actin gene PCR, as described by Teixeira et al.19 The qPCR protocol was based on SYBR Green using primers for the conserved kinetoplast minicircle DNA of Leishmania: 5′-GGC CCA CTA TAT TAC ACC AAC CCC-3′ and 5′-GGG GTA GGG GCG TTC TGC GAA-3′.20 The protocol was performed as described by Teixeira et al.14 DNA extracted from L. infantum (MCER/BR/79/M6445) was used as a positive control and H2O miliQ was used as a negative control. Samples that showed amplification before cycle 40 were considered positive. Samples were coded before the test so that the laboratory worker was not aware of the clinical status of the animal. The reaction was standardized with R2 = 0.997 (98.415% efficiency) and was classified as moderate to good reproducibility (κ = 0.6623; 95% CI, 0.53–0.79; and κmax = 0.95559). All qPCR tests were performed at the Laboratory of Leishmaniases of the Tropical Medicine Center of the University of Brasília.

Data analysis.

To build explanatory models for regional infections, univariate Cox regressions were performed to select variables with a hazard ratio (HR) with P ≤ 0.20. Subsequently, a Cox model was built with all variables that met the criterion through backward elimination selection. Models were built successively with the removal of the variable with the lowest statistical significance, until only variables with P ≤ 0.05 remained. Cox regressions were performed with robust SD (considering the presence of clusters in houses) and with the Efron method for handling ties. The assumption of proportional hazards was assessed using the Schoenfeld residual analysis in all generated models. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata® software (version 15.1; StataCorp, LLC, College Station, TX).

Ethical aspects.

Peripheral blood was collected with a 5-mL syringe from physically restrained dogs, and the collected blood was conditioned in a hematological tube with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid and a hematological tube with a clot activator. The procedures for biological sample collection were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Institute of Biology of the University of Brasília (no. UnBDoc 11253/2015). Legally competent animal guardians consented to the participation of their animals in the study and signed a consent form.

The guardians were also duly informed that if the test results were positive, the competent health authorities would be notified.8

RESULTS

Sample description at baseline.

From June 2016 to March 2018, 260 dogs from 166 households were included. Among them, 248 dogs residing in 159 households were included; 12 dogs were excluded because of inadequate quality of biologic material for laboratory analyses.

Description of guardian and household characteristics.

Of the 159 houses included in the study, 88 were from Serra Azul and 71 from Vila Rabelo. There was a mean of 1.56 dogs per household; 105 houses had 1 dog, 36 houses had 2 dogs, and 18 houses had ≥ 3 dogs.

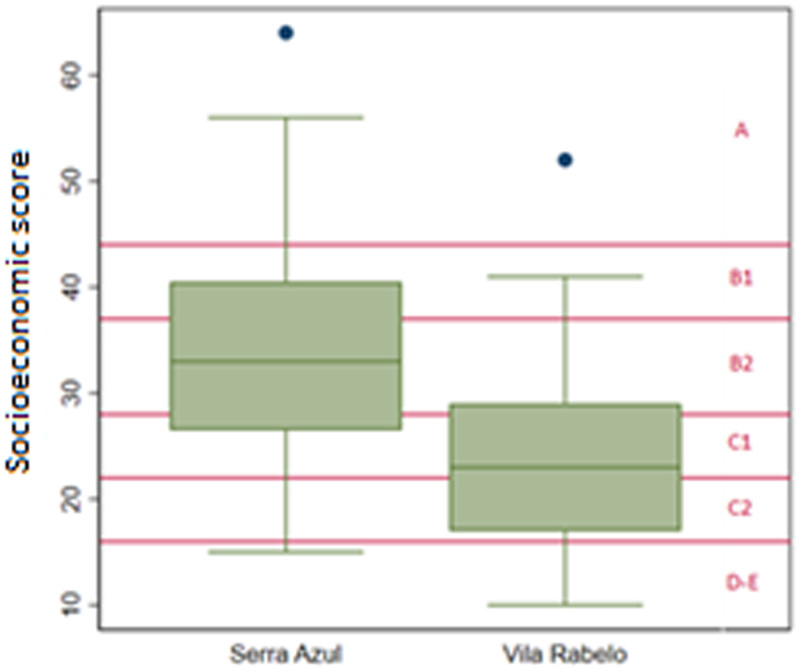

The mean socioeconomic score was 30.20 points (B2 strata), indicating an estimated mean monthly household income of BRL 4,852.00. Serra Azul residents had a mean socioeconomic score of 34.4 points (95% CI, 32.18–36.59), which was significantly greater than that of Vila Rabelo residents, with a mean of 23.6 points (95% CI, 21.53–25.63). Approximately three quarters of the families sampled in Serra Azul belonged to strata A and B, whereas only one quarter of the families in Vila Rabelo belonged to these higher socioeconomic strata (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of socioeconomic scores by locality.

Most of the interviewed guardians claimed to know the terms leishmaniasis and kala-azar, with only 17 of 159 dog guardians (10.69%) being unaware of the terms. The mode of leishmaniasis transmission was unknown to 91 interviewed guardians (57.2%), and the symptoms of VL in humans were unknown to 132 guardians (83.0%). The vaccine for canine leishmaniasis was unknown to 82 guardians (51.6%): 53 (60.2%) residing in Serra Azul and 29 (40.9%) in Vila Rabelo. Only 21 guardians (13.2%) recognized that CVL is a chronic disease with no proven cure, and 114 guardians (71.7%) reported using insecticides in the household environment. The use of fly screens on windows was reported in only 12 houses (7.55%), and 108 houses (67.9%) had backyards with soil or grass. Chickens were found in 38 houses (24.9%). In 30 houses in Vila Rabelo and 37 houses in Serra Azul, the guardians reported having previously received environmental investigation visits (67 of 159 houses, 42.14%). The characteristics of the dogs included in the sample are described in Tables 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics (categorical variables) of a cohort of dogs living in an endemic area of the Federal District, Brazil, 2016 to 2018

| Characteristic | Positive (n = 68), n (%) | Negative (n = 180), n (%) | Total (N = 248), n |

|---|---|---|---|

| Location | |||

| Serra Azul | 58 (85.3) | 90 (50) | 148 |

| Vila Rabelo | 10 (14.7) | 90 (50) | 100 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 41 (60.3) | 86 (47.7) | 127 |

| Female | 27 (39.7) | 94 (52.3) | 121 |

| Short hair | |||

| Yes | 47 (69.1) | 106 (58.9) | 153 |

| No | 21 (30.9) | 74 (41.1) | 95 |

| Light hair | |||

| Yes | 22 (32.3) | 47 (26.1) | 69 |

| No | 41 (60.3) | 120 (66.6) | 161 |

| CVL vaccine* | |||

| Yes | 4 (5.9) | 36 (20.0) | 40 |

| No | 64 (94.1) | 144 (80.0) | 208 |

| Multiple vaccines* | |||

| Yes | 43 (63.2) | 114 (63.3) | 157 |

| No | 25 (36.8) | 66 (36.7) | 91 |

| Nutrition | |||

| Adequate food | 29 (42.7) | 91 (50.5) | 120 |

| Leftovers | 39 (57.3) | 89 (48.5) | 128 |

| Veterinary appointments in the past year† | |||

| Yes | 14 (20.6) | 48 (26.6) | 62 |

| No | 54 (79.4) | 132 (73.4) | 186 |

| Ectoparasites | |||

| Yes | 29 (42.6) | 65 (36.7) | 95 |

| No | 35 (51.5) | 84 (46.7) | 119 |

| Dogs using repellent collars | |||

| Yes | 14 (20.6) | 30 (16.7) | 44 |

| No | 54 (79.4) | 150 (83.3) | 204 |

| Free access to the external environment in the household | |||

| Yes | 40 (58.8) | 107 (59.5) | 147 |

| No | 28 (41.2) | 73 (40.5) | 101 |

| Sleeps outside the household | |||

| Yes | 55 (80.9) | 138 (76.6) | 193 |

| No | 13 (19.1) | 42 (23.4) | 55 |

| Other dogs on lot | |||

| Yes | 31 (45.6) | 82 (45.5) | 113 |

| No | 37 (54.4) | 98 (54.5) | 135 |

| Chickens present | |||

| Yes | 12 (17.6) | 57 (31.7) | 69 |

| No | 56 (82.4) | 123 (68.3) | 179 |

| Paved backyard | |||

| Yes | 16 (23.5) | 56 (31.1) | 72 |

| No | 52 (76.5) | 124 (68.9) | 176 |

| Net in the house windows | |||

| Yes | 6 (8.8) | 12 (6.7) | 18 |

| No | 62 (91.2) | 168 (93.3) | 230 |

| Insecticide in the environment | |||

| Yes | 45 (66.2%) | 128 (71.1) | 173 |

| No | 23 (33.8) | 52 (28.9) | 75 |

CVL = canine visceral leishmaniasis.

At least one shot.

At least one.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics (continuous-scale variables) of a cohort of dogs living in an endemic area of the Federal District, Brazil, 2016 to 2018

| Characteristic | Mean | SD | Minimum–maximum | Missing, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 4.20 | 3.61 | 0–16 | 10 (4.03) |

| Clinical score | 2.16 | 2.64 | 0–17 | 0 (0) |

| Socioeconomic score | 30.20 | 11.75 | 10–64 | 0 (0) |

The dogs had a mean low clinical score, with 54.03% being considered asymptomatic (score ≤ 1 point). The mean age was 4.2 years (range, 4 months–16 years). The age of 10 dogs was not registered.

Infection prevalence at baseline.

As above earlier, the quality of the sample was adequate in 248 of 260 dogs for outcome evaluation; however, it was unsuitable in 12 excluded dogs for molecular analysis, revealed by the lack of amplification of the β-actin gene in conventional PCR. After excluding these 12 dogs, 248 dogs were evaluated at baseline.

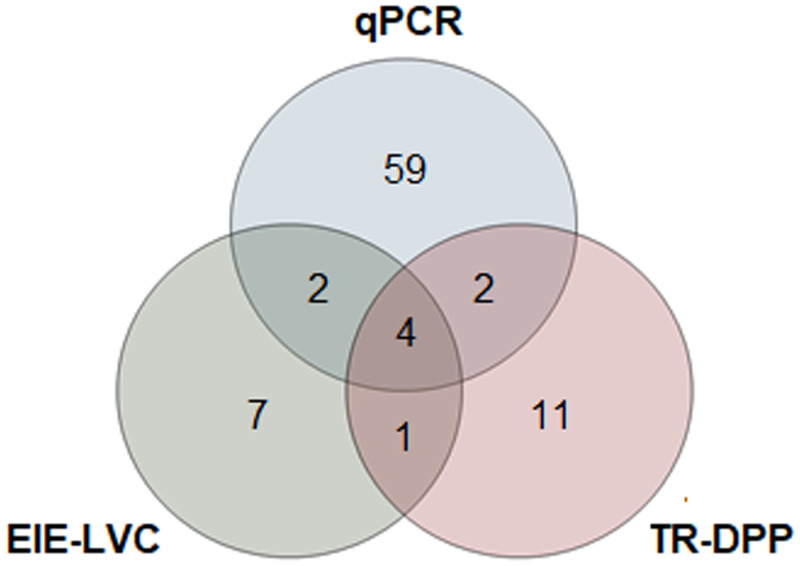

The molecular diagnosis of the 248 dogs by qPCR revealed that 67 dogs were infected with Leishmania spp. The TR-DPP identified 18 dogs as positive and the EIE-LVC identified 14 dogs as positive. Serological test series identified 27 dogs that were seropositive and, of this group, 19 were negative on qPCR (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Venn diagram of all samples classified as positive on the different diagnostic tests used. Among the 248 samples, 86 were classified as positive on at least one diagnostic test. EIE-LVC = Biomanguinhos Enzyme Immunoassay; qPCR = quantitative polymerase chain reaction; TR-DPP = Biomanguinhos Rapid Dual Patch Platform Test.

Incidence estimation.

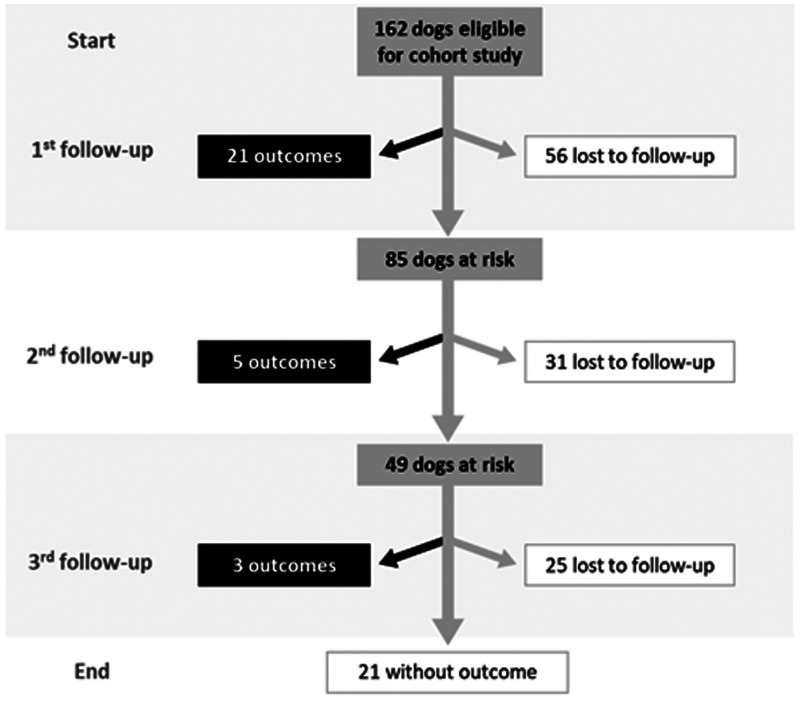

Of the 248 dogs, 162 were negative on all three diagnostic tests (qPCR, TR-DPP, and EIE-LVC) and thus eligible for the cohort study. Dogs were monitored for at least 6 months. The study flow is depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Flow diagram of the cohort study.

The mean follow-up of the dogs in the cohort was 8.35 months, and the observed time at risk was 1.353 dog-months. The time-at-risk contribution of 162 dogs in the cohort is described in Supplemental Figure S2.

Of the 162 dogs, 56 were censored before the first follow-up. The characteristics of the dogs censored before the first follow-up and with one or more follow-ups are described in Supplemental Table S1. Losses between baseline and the first follow-up were not selective regarding the observed variables, except for the variable “other dogs in the lot” (P < 0.05). The main reasons for loss to follow-up were completion of the study period (30.3%), failure to locate the dog guardian (27.3%), withdrawal from the study (19.7%), death of the dog (12.1%), change of address (6.1%), dog aggressiveness (3.8%), and dog escape (0.8%).

Of the 162 dogs participating in the cohort study, 29 contracted Leishmania infection, and most of them were diagnosed by qPCR (26 of 29, 89.6%). The characteristics of these 29 dogs were as follows: 55.2% (16 of 29) were male, 51.8% (15 of 29) had short hair, and the median age was 3 years old (IQR 0–6 years). The estimated incidence density for Leishmania infection in the canine population studied during the 2-year follow-up was 2.14 cases per 100 dog-months (95% CI, 1.49–3.08).

The estimated Leishmania infection-free survival at the 1-year and 2-year follow-up was 72.8% (95% CI, 62.2–80.8) and 63.7% (95% CI, 49.7–74.7), respectively (Supplemental Figure S3). Outcomes occurred primarily at the first visit. Of the 106 dogs at risk, 21 were diagnosed with Leishmania infection at the 6-month follow-up. Or the 54 dogs at risk at the second visit, five had the same outcome. Of the 24 dogs at risk at the third visit, three were positive for Leishmania. Overall, 29 dogs developed Leishmania infection—26 identified by qPCR and three by the TR-DPP and EIE-LVC.

Risk factor analysis.

The variables “CVL vaccine,” “dogs using repellent collars,” “other dogs on lot,” “presence of chickens,” and “paved yard” showed at least moderate association with protective effect against the outcome (P < 0.25), whereas the variable “socioeconomic score” was identified as a significant risk factor (P = 0.04). These six variables were then included in the multivariate regression model (Table 3).

Table 3.

Univariate analysis of factors associated with visceral leishmaniasis in a cohort of resident dogs from an enzootic region in the Federal District, Brazil

| Variable | Exposure | n | Hazard ratio | SD | P value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Location | Vila Rabelo/Serra Azul | 162 | 0.71 | 0.28 | 0.406 | 0.32–1.58 |

| Socioeconomic score | Punctuation + 1/punctuation | 162 | 1.03 | 0.02 | 0.043 | 1.00–1.07 |

| Age | Age + 1/age | 155 | 1.07 | 0.06 | 0.220 | 0.96–1.20 |

| Gender | Male or female | 162 | 1.42 | 0.51 | 0.323 | 0.71–2.88 |

| Short hair | Yes or no | 162 | 0.79 | 0.29 | 0.514 | 0.38–1.61 |

| Light hair | Yes or no | 150 | 0.95 | 0.41 | 0.904 | 0.41–2.19 |

| CVL vaccine | Yes or no | 162 | 0.54 | 0.25 | 0.184 | 0.22–1.34 |

| Multiple vaccines | Yes or no | 162 | 1.57 | 0.59 | 0.234 | 0.75–3.29 |

| Adequate feeding | Yes or no | 162 | 1.31 | 0.5 | 0.47 | 0.63–2.75 |

| Veterinary appointments in the past year | Yes or no | 162 | 1.26 | 0.56 | 0.602 | 0.53–3.01 |

| Ectoparasites | Yes or no | 132 | 0.65 | 0.27 | 0.308 | 0.29–1.48 |

| Dogs using repellent collars | Yes or no | 162 | 0.36 | 0.24 | 0.124 | 0.96–1.33 |

| Free access to the external environment in the household | Yes or no | 162 | 1.23 | 0.48 | 0.588 | 0.57–2.66 |

| Sleeps outside the household | Yes or no | 162 | 0.9 | 0.41 | 0.823 | 0.37–2.21 |

| Other dogs on lot | Yes or no | 162 | 0.51 | 0.2 | 0.09 | 0.23–1.11 |

| Chickens present | Yes or no | 162 | 0.56 | 0.24 | 0.167 | 0.24–1.27 |

| Paved backyard | Yes or no | 162 | 0.36 | 0.19 | 0.054 | 0.13–1.02 |

| Net in the house windows | Yes or no | 162 | 1.22 | 0.89 | 0.783 | 0.29–5.08 |

| Insecticide in the environment | Yes or no | 162 | 0.81 | 0.33 | 0.598 | 0.36–1.80 |

CVL = canine visceral leishmaniasis.

Backward selection sequentially eliminated the variables “multiple vaccine,” “location,” “CVL vaccine,” “paved yard,” “presence of chickens,” and “age” (Table 4). The variables “socioeconomic score,” with an HR of 1.04 (95% CI, 1.01–1.06, P = 0.03), and “paved yard,” with an HR of 0.19 (95% CI, 0.13–1.01, P = 0.05), remained in the final model. None of the models generated by backward selection violated the assumption of proportional hazards.

Table 4.

Proportional hazard model of factors associated with Leishmania infection in a cohort of resident dogs from an enzootic region in the Federal District, Brazil

| Covariates and iterations | HR | Robust SD | P value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iteration 1 | ||||

| Socioeconomic score | 1.03 | 0.01 | 0.08 | 1.00–1.06 |

| CVL vaccine | 0.57 | 0.25 | 0.20 | 0.24–1.36 |

| Dogs using repellent collars | 0.39 | 0.25 | 0.14 | 0.11–1.37 |

| Other dogs on lot | 0.66 | 0.30 | 0.37 | 0.27–1.62 |

| Chickens present | 0.64 | 0.29 | 0.33 | 0.26–1.57 |

| Paved backyard | 0.34 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.12–0.97 |

| Iteration 2 | ||||

| Socioeconomic score | 1.03 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 1.00–1.06 |

| CVL vaccine | 0.59 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.24–1.44 |

| Dogs using repellent collars | 0.32 | 0.20 | 0.07 | 0.09–1.10 |

| Chickens present | 0.58 | 0.26 | 0.22 | 0.24–1.38 |

| Paved backyard | 0.32 | 0.17 | 0.04 | 0.11–0.93 |

| Iteration 3 | ||||

| Socioeconomic score | 1.03 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 1.00–1.06 |

| Dogs using repellent collars | 0.33 | 0.21 | 0.08 | 0.09–1.13 |

| Chickens present | 0.57 | 0.26 | 0.21 | 0.24–1.37 |

| Paved backyard | 0.34 | 0.18 | 0.04 | 0.12–0.97 |

| Iteration 4 | ||||

| Socioeconomic score | 1.04 | 0.01 | 0.01 | 1.01–1.07 |

| Dogs using repellent collars | 0.30 | 0.20 | 0.08 | 0.08–1.13 |

| Paved backyard | 0.37 | 0.19 | 0.06 | 0.13–1.03 |

| Iteration 5, final model | ||||

| Socioeconomic score | 1.03 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 1.00–1.06 |

| Paved backyard | 0.36 | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.13–1.01 |

CVL = canine visceral leishmaniasis; HR = hazard ratio.

DISCUSSION

The main finding in the analysis of risk factors was the higher purchasing power of the guardians with a greater incidence of Leishmania infection, corroborating the results of a cross-sectional study conducted in Fercal, Federal District.14 The HR obtained in the final model indicates that the risk of canine infection increases by 3% for each additional point in the economic status score. Reports on the association between socioeconomic status and CVL are scarce in the literature. Other researchers found the opposite effect, indicating that dogs from low-income families have a greater risk of infection (odds ratio [OR], 2.3; 95% CI, 1.4–3.8)21; and in another study, an OR of 2.0 (95% CI, 1.2–3.2) was reported.22 Such discrepant findings may be the result of different study designs that addressed the problem in a cross-sectional manner, similar to the study by Teixeira et al.,14 and different eligibility criteria and infection case definitions. Another relevant difference between the studies was the prevalence of infection at baseline, which may reflect indirectly the variable degrees of infection between different geographic regions.

Thus, the specific criteria for the definition of infection used in each study do not allow an adequate and consistent evaluation among them. The same diagnostic test performed in different laboratories can also affect the risk estimates obtained in the studies, as demonstrated in a previous cohort study by Coura-Vital et al.15

Furthermore, the fact that socioeconomic status constitutes a distal factor to the outcome of infection suggests that it may be associated with several proximal variables that would peculiarly compose the causal chains in each region. A possible explanation for the obtained results could be a greater government intervention to control CVL in areas with families with lower purchasing power. Specifically in the studied region, the owners of vaccinated dogs had a lower mean socioeconomic score (20.96; 95% CI, 17.83–24.12) than the owners of nonvaccinated dogs (31.97; 95% CI, 30.43–33.51), which could have influenced the results because vaccination protects against infection to some degree. However, even after controlling for the other five covariates, including CVL vaccination, the effect of socioeconomic score still resulted in a 2.6% increased risk for each point on the questionnaire, with a statistical significance of P = 0.08, thus indicating that none of these proximal covariates could fully explain the effect of socioeconomic score.

Depending on when the dog population was observed, there may also have been a cohort effect that selectively affected dogs from guardians with lower or higher socioeconomic status. Higher socioeconomic status could also contribute to an increased life span in animals, which would allow more time for them to become ill with VL, a chronic disease, than with other diseases that lead to death more quickly.14 The lower educational level of the guardian, another variable distal to the phenomenon of VL disease in dogs, has also been explored as a risk factor for the disease in previous studies.22–26

In the final model, in addition to the socioeconomic score, the variable “paved backyard” was included because its statistical significance was very close to the stipulated limit, and it had high biologic plausibility. The variable had a protective effect, indicating that the presence of soil or grass in the backyard would increase the risk of Leishmania infection. This is in line with the results of several previous studies14,22,25,26 and the life cycle of the vector, which needs organic matter to reproduce.

The use of spot-on products or repellent collars had a notable but marginally significant protective effect on dogs, possibly because of the lack of data collection differentiation between active ingredients that would or would not act against sandflies. The use of repellents on dogs, especially through the use of collars impregnated with 4% deltamethrin, is considered one of the best alternatives for CVL.27,28 Although the covariate “dog repellent” was not included in the final model, it provides a better fit for the economic score variable when included in the model, as seen in iteration 4 inTable 4.

There is heterogeneity around the covariate “short hair.” Although in our study we excluded this variable from the model, short hair was a strong predictive factor in the study by Moreira et al.,10 with a relative risk of 9.4 (95% CI, 4.3–20.7); a moderate predictive factor in the study by Monteiro et al.29 (OR, 2.43; 95% CI, 1.18–5.03]; and in other studies, such as the meta-analysis by Belo et al.12 (combined OR, 1.39; 95% CI, 1.05–1.85) and Coura-Vital et al.15 (HR, 1.21; 95% CI, 0.93–1.57). Such variation may be the result of other biologic issues in dogs (e.g., breed), which may influence vector attractiveness or predisposition/resistance to L. infantum infection.

CVL vaccination had a protective, but not statistically significant, effect. CVL-vaccinated dogs in the region participated in a pilot campaign organized by the environmental surveillance service that covered only a portion of the animals in the region. Because of logistic difficulties in administering the three doses to the animals, only a small portion of the population was immunized correctly. Thus, the protective effect was possibly too small to be detected in the sample size studied.

The method chosen to define the infection rate proved to be correct, including the observation that, during the study period, there was a vaccine intervention in the region where the research was conducted, possibly affecting the measurement of the outcome if it was based only on the detection of antibodies by serological methods.

Our cohort study has limitations that may affect the power to test the hypotheses in the multivariate analysis model, thus compromising the power of the study. The most relevant limitation was the magnitude of losses during follow-up. The most common type of censoring during follow-up was the inability to locate the animal guardian, or guardian refusal to allow the evaluation. Many guardians received the first diagnosis and considered it unnecessary to subject the dog to a second evaluation, and some preferred not to perform more tests for fear of a positive result that could result in a possible euthanasia of the animal. The second factor that affected the study negatively was the low incidence of the disease during the observation period. These limitations, which affected the sample size, also did not allow for greater stratification of socioeconomic aspects. It is important to highlight this aspect because more studies need to be executed in this sense.

The serological exams recommended by Brazilian health authorities used in this study, the TR-DPP and EIE-LVC,30 are targets of some criticism regarding their performance.19,31 Recently, we reported19 the low accuracy and agreement of serological tests when compared with a composite reference standard composed of parasitological and molecular assays. The low accuracy and the heterogeneity between tests would be, at least in part, attributable to the fact that validation studies are constantly challenged by the absence of a consensus reference test, and most of the available serology assays were not validated properly for the detection of asymptomatic infection in dogs.

In our current cohort, most of the infections were detected by qPCR (26 of 29, 89.6%) in contrast to the serological tests (3 of 29, 10.4%). Furthermore, serological tests could be affected by cross-reactions with other diseases such as ehrlichiosis, babesiosis, or even Chagas disease.32–34 It was not possible to carry out differential diagnosis assessments for these diseases, but all samples were stored for future research in a biorepository. Last, we adjusted the main effects for confounding; however, other relevant factors, related to the environment around the household and the influence of the distance between domiciles and native cerrado vegetation, were not evaluated.

In conclusion, higher purchasing power of the guardians and presence of a paved yard were the factors with the greatest effect on the risk of Leishmania infection, with the former being a risk and the latter being a protective condition. The results reiterate the challenge of implementing CVL control measures because the characteristics associated with the risk of infection with the highest significance do not favor easy-to-implement interventions. Future studies should explore variables related to canine biology, microclimate, and their relationship to guardian socioeconomic status.

Supplemental files

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Ana Paula Sampaio Cardoso and Ana Claudia Negret Scalia for technical assistance in the laboratory, and Barbosa for his assistance during the follow-up. The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene (ASTMH) assisted with publication expenses.

Note: Supplemental information appears at www.ajtmh.org.

REFERENCES

- 1. World Health Organization , 2021. Leishmaniasis Key Facts. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/leishmaniasis. Accessed September 28, 2021.

- 2. Souza NA Brazil RP Arai AS , 2017. The current status of the Lutzomyia longipalpis (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) species complex. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 112: 161–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Michalsky EM Guedes KS Lara-Silva FO França-Silva JC Dias CL Barata RA Dias ES , 2011. Natural infection with Leishmania infantum chagasi in Lutzomyia (Lutzomyia) longipalpis (Diptera: Psychodidae) sandflies captured in the municipality of Janaúba, State of Minas Gerais, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 44: 58–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Brasil, MS/SVS/DVE–Ministério da Saúde Sistema de Informação de Agravos de Notificação—SINAN: Notificações Registradas: Banco de Dados. Available at: http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br. Accessed April 27, 2018.

- 5. Dantas-Torres F et al. 2019. Canine leishmaniasis control in the context of one health. Emerg Infect Dis 25: E1–E4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Harhay MO Olliaro PL Costa DL Henrique C Costa N , 2011. Urban parasitology: visceral leishmaniasis in Brazil. Trends Parasitol 27: 403–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. da Rocha ICM Dos Santos LHM Coura-Vital W da Cunha GMR Magalhães FC da Silva TAM Morais MHF Oliveira E Reis IA Carneiro M 2018. Effectiveness of the Brazilian visceral leishmaniasis surveillance and control programme in reducing the prevalence and incidence of Leishmania infantum infection. Parasit Vectors 11: 586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ministério da Saúde/Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde/Departamento de Vigilância Epidemiológica , 2014. Manual de Vigilância e Controle da Leishmaniose Visceral. Mato Grosso, Brazil: Ministério da Saúde. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Costa CHN Vieira JBF , 2001. Mudanças no controle da leishmaniose visceral no Brasil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 34: 223–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Moreira ED Mendes De Souza VM Sreenivasan M Nascimento EG Pontes De Carvalho L , 2004. Assessment of an optimized dog-culling program in the dynamics of canine Leishmania transmission. Vet Parasitol 122: 245–252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. de Sousa-Paula LC da Silva LG Sales KG da S Dantas-Torres F , 2019. Failure of the dog culling strategy in controlling human visceral leishmaniasis in Brazil: a screening coverage issue? PLoS Negl Trop Dis 13: e0007553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Belo VS et al. 2013. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the factors associated with Leishmania infantum infection in dogs in Brazil. Vet Parasitol 195: 1–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Belo VS et al. 2013. Factors associated with visceral leishmaniasis in the Americas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 7: e2182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Teixeira AIP Silva DM de Freitas LRS Romero GAS , 2020. A cross-sectional approach including dog owner characteristics as predictors of visceral leishmaniasis infection in dogs. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 115: e190349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Coura-Vital W et al. 2013. Canine visceral leishmaniasis: incidence and risk factors for infection in a cohort study in Brazil. Vet Parasitol 197: 411–417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lopes EG et al. 2018. Vaccine effectiveness and use of collar impregnated with insecticide for reducing incidence of Leishmania infection in dogs in an endemic region for visceral leishmaniasis, in Brazil. Epidemiol Infect 146: 401–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Instituto Brasileiro de Beografia e Estatística , 2010. Censo 2010, Sinopse por Setores. Available at: https://censo2010.ibge.gov.br/sinopseporsetores. Accessed September 18, 2019.

- 18. Alves MCGP de Matos MR Reichmann MDL Harrison Dominguez M , 2005. Estimation of the dog and cat population in the State of São Paulo. Rev Saude Publica 39: 891–897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Teixeira AIP et al. 2019. Improving the reference standard for the diagnosis of canine visceral leishmaniasis: a challenge for current and future tests. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 114: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pita-Pereira D et al. 2012. SYBR Green-based real-time PCR targeting kinetoplast DNA can be used to discriminate between the main etiologic agents of Brazilian cutaneous and visceral leishmaniases. Parasit Vectors 5: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Coura-Vital W et al. 2011. Prevalence and factors associated with Leishmania infantum infection of dogs from an urban area of Brazil as identified by molecular methods. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 5: e1291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Carvalho AG Luza JGG Rodrigues LD Dias JVL Fontes CJF , 2019. Factors associated with Leishmania spp. infection in domestic dogs from an emerging area of high endemicity for visceral leishmaniasis in central-western Brazil. Res Vet Sci 125: 205–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bernardino MDGDS Angelo DFDS Silva RBS Silva EGD Silva LFFE Vaz AFM Melo MA Santos CSAB Alves CJ Azevedo SS , 2020. High seroprevalence and associated factors for visceral leishmaniasis in dogs in a transmission area of Paraíba State, northeastern Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 29: e016919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Veloso ECM Negreiros ADS da Silva JP Moura LD Nascimento LFM Silva TS Werneck GL Cruz MDSPE , 2021. Socio-economic and environmental factors associated with the occurrence of canine infection by Leishmania infantum in Teresina, Brazil. Vet Parasitol Reg Stud Rep 24: 100561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Abrantes TR Werneck GL Almeida AS Figueiredo FB , 2018. Brazil environmental factors associated with canine visceral leishmaniasis in an area with recent introduction. Cad Saude Publica 34: 1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Figueiredo ABF Werneck GL Cruz M do SPE Silva JP da Almeida AS de , 2017. Land use, land cover, and prevalence of canine visceral leishmaniasis in Teresina, Piauí State, Brazil: an approach using orbital remote sensing. Cad Saude Publica 33: e00093516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kazimoto TA et al. 2018. Impact of 4% deltamethrin-impregnated dog collars on the prevalence and incidence of canine visceral leishmaniasis. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis 18: 356–363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Silva RA et al. 2018. Effectiveness of dog collars impregnated with 4% deltamethrin in controlling visceral leishmaniasis in Lutzomyia longipalpis (Diptera: Psychodidade: Phlebotominae) populations. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 113: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Monteiro FM et al. 2019. Canine visceral leishmaniasis: detection of Leishmania spp. genome in peripheral blood of seropositive dogs by real-time polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Microb Pathog 126: 263–268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Ministério da Saúde/Secretaria de Vigilância em Saúde/Departamento de Vigilância de Doenças Transmissíveis , 2011. Nota Técnica Conjunta 01/2011. Mato Grosso, Brazil: Ministério da Saúde. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Figueiredo FB et al. 2018. Validation of dual-path plantaform chromatographic immunoassay (DPP® CVL Rapid Test) for serodiagnosis of canine visceral leishmaniasis. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz 113: e180260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zanette MF Lima VM Laurenti MD Rossi CN Vides JP Vieira RF Biondo AW Marcondes M , 2014. Serological cross-reactivity of Trypanosoma cruzi, Ehrlichia canis, Toxoplasma gondii, Neospora caninum and Babesia canis to Leishmania infantum chagasi tests in dogs. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop 47: 105–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pessoa-E-Silva R Vaitkevicius-Antão V de Andrade TAS de Oliveira Silva AC de Oliveira GA Trajano-Silva LAM Nakasone EKN de Paiva-Cavalcanti M , 2019. The diagnosis of canine visceral leishmaniasis in Brazil: confronting old problems. Exp Parasitol 199: 9–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Guedes PEB de Oliveira TN Carvalho FS Carlos RSA Albuquerque GR Munhoz AD Wenceslau AA Silva FL , 2015. Canine ehrlichiosis: prevalence and epidemiology in northeast Brazil. Rev Bras Parasitol Vet 24: 115–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.