Abstract

Background/Aims:

Phase 1 trials with healthy volunteers are an integral step in drug development. Commentators worry about the possible exploitation of healthy volunteers because they are assumed to be disadvantaged, marginalized, and inappropriately influenced by the offer of money for research for which they do not appreciate the inherent risks. Yet there are limited data to support or refute these concerns. This study aims to describe the socio - demographic characteristics, motivations and enrollment decision making of a large cohort of healthy volunteers.

Methods:

We used a cross - sectional anonymous survey of 1194 healthy volunteers considering enrollment in phase 1 studies at Pfizer Clinical Research Units in New Haven CT, Brussels Belgium, and Singapore. Descriptive statistics describe motivations and sociodemographic characteristics. Comparisons between groups were examined.

Results:

The majority rated consideration of risks as more important to their enrollment decision than the amount of money, despite reporting that their primary motivation was financial. Risk, time, money, the competence and friendliness of research staff, and contributing to medical research were important factors influencing enrollment decisions for most participants. The majority of healthy volunteers in this cohort were male, single, reported higher than high school education, and 70% had previous research experience. Many reported low annual incomes (50% below US$25,000) and high rates of unemployment (33% overall). Nonetheless, risk as an important consideration, money, and other reported considerations and motivations, except for time, did not vary by income, employment, education, or previous experience. There were regional differences in both sociodemographic characteristics and factors important to participation decisions.

Conclusions:

Healthy volunteers in phase 1 studies consider risks as more important to their enrollment decisions than the amount of money offered, although most are motivated to participate by the offer of money. Healthy volunteers are indeed low income, disproportionately unemployed, and have significant prior research experience. Yet these factors do not appear to affect either their motivations for participation or factors important to their research enrollment decisions.

Keywords: Healthy volunteers, financial incentives, motivations

Introduction

Phase 1 clinical trials, designed to assess the safety of new pharmaceutical agents or medical devices, are a critical step in drug development. Phase 1 trials, many of which are first - in - human tests of investigational agents, usually enroll healthy individuals, as drug safety, dosing, and pharmacokinetics can be most accurately evaluated in the absence of underlying medical conditions or pathologies.1,2 There are no expected therapeutic benefits for the healthy volunteers who participate in phase 1 trials and they face potential uncertain health risks as well as inconvenience associated with participation in these studies.3,4

The motivations of healthy volunteers in phase 1 trials differ from those of patients with illnesses who enroll in phase 1 clinical trials.5,6 Patient - subjects often seek access to treatment or medical care, or have an interest in further understanding their own disease or condition,5 while healthy volunteers are often motivated by monetary compensation.7,8 Previous studies have shown that although financial compensation is the primary reason healthy individuals enroll in phase 1 clinical trials, other factors such as an interest in science and medicine, altruism, curiosity, social contact, and access to free medical care can play a role.8

Critics also worry that healthy phase 1 volunteers are an exploited “research underclass,” and that the shift of drug trials from universities to private testing sites, increased pressure to recruit trial subjects, and the outsourcing of ethical oversight to commercial institutional review boards facilitate such exploitation.9 Existing literature presumes that phase 1 healthy volunteers are generally of low income, with low levels of education, unemployed, and easily influenced by the offer of money,10,11 and that “[p]oor people predominate as a subgroup of those who take part in healthy volunteer research.”12 A subset of healthy volunteers, sometimes referred to as “professional volunteers,” who participate in multiple studies over time and rely on the associated financial compensation as a major source of income, are thought to be especially socially or economically disadvantaged and vulnerable.13 Limited data exist to confirm or deny such claims.

This study seeks to address these concerns by examining: (a) socio demographic characteristics of healthy volunteers who participate in phase 1 drug development studies; (b) participant motivations; and (c) factors that influence their enrollment decisions.

Methods

Study design

This is a cross sectional, descriptive survey of healthy volunteers considering enrollment in phase 1 drug development studies at Pfizer Clinical Research Units on three continents. Data were obtained through a survey administered after the volunteers went through the consent process for a phase 1 study but before the study began.

Study sample

The study sample consisted of healthy male and female volunteers 18 years of age and older who came to one of three Pfizer Inc. Clinical Research Units (CRU) that are located in New Haven, Connecticut USA, Brussels, Belgium and Singapore. Those who completed an informed consent session for possible enrollment in a Phase 1 study, whether or not they ultimately enrolled or were eligible to enroll in the phase 1 study, were invited to complete the survey. Volunteers who participated in an informed consent session were invited to participate on consecutive days between September 2009 and March 2011 in Belgium (402), Singapore (301), and the US (573). Of 573 approached in the US, 79 (13.8%) explicitly declined to participate and left their surveys blank; several participants at the other sites also left surveys blank, resulting in 1194 total usable surveys [Belgium (400), Singapore (300), US (494)], an estimated 93% response rate. Participants at each site were assigned a unique numerical identifier and were advised to take the survey only once.

Survey instrument

The survey instruments were developed by the authors through a step wise iterative process that included (a) a comprehensive literature review; (b) draft survey development; (c) cognitive pre - testing; (d) revisions; (e) pretesting with 12 healthy volunteers participating in Vaccine Research Center studies at the US National Institutes of Health (NIH); and (f) final revisions. Surveys in the US and Singapore were administered in English. Belgian participants were offered the same survey translated into French and Flemish. Translation was done by the NIH Office of Research Services and reviewed for accuracy at the Brussels CRU. Certain demographic questions (e.g., income and education response categories) were adapted for each location. Survey questions covered 3 domains: (a) study participant motivations; (b) factors influencing enrollment decisions; and (c) socio demographic characteristics, including age, gender, household income, education, employment, location of residence, and previous research experience. Surveys were given to participants by CRU staff members, self administered in the respective CRUs, and then sent without identifying information to the NIH for entry and analysis.

Respondents were asked to indicate their main motivation for participation in the Pfizer study, and then asked to rate on a scale of very important, moderately important, slightly important, or not important, a list of factors that may have influenced their enrollment decision. Subsequently, they were given a series of paired - choice questions and asked to choose the one factor of the two that was more important to their enrollment decision. For example, “When deciding whether or not to join this study, which of these factors was more important to your decision? The amount of money offered OR the risks and side effects of the study intervention?” See Box 1. The list of factors and those included in the paired choice questions were based on the existing, albeit limited, literature on motivations and experiences of healthy volunteers.7, 8, 14, 15 Respondents were also asked to describe the main reason they chose research participation over earning money in a part time job or some other way, and the reason that they chose the particular Pfizer study over other Pfizer studies.

Box 1. Sample Paired - Choice Questions*.

“When you were deciding whether or not to join the study, which of these factors was more important to your decision…

The number and type of painful procedures OR The amount of time you would have to spend at Pfizer CRU?

The number and type of painful procedures OR The amount of money offered?

The amount of money offered OR How much the study helps future patients?

The amount of money offered OR The type of drug? (e.g. psychiatric, blood pressure, etc.)

The number and type of painful procedures OR Possible risks and side effects from study medications?

Possible risks and side effects from study medications OR The amount of money offered?

*Choices offered were based on literature about phase 1 study participation. (e.g. citations #7, 8, 14, 15)

Data analysis / statistical methods

Data were keyed into an Excel database, and checked for accuracy through a random 10% double entry. Frequency distributions and simple descriptive statistics describe the data. Categorical data (e.g., socio - demographic variables, motivations) were compared among groups (e.g., region, sex) by chi - square or Fisher’s exact test. Ordered categories were analyzed by the Kruskal - Wallis test. Continuous variables (e.g., age, number of previous studies) were compared between groups (e.g., sex) by the t - test or among groups (e.g., region) by analysis of variance (ANOVA). Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models were carried out to assess, and adjust for, the effect of each socio - demographic characteristic on the outcomes of motivations and factors influencing enrollment. A p - value <0.05 and an odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) excluding 1.0 were considered statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SAS v9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Human subjects protection

This study was approved by the Combined NeuroSciences Institutional Review Board at the National Institutes of Health, the Erasme EC (Comite d’Ethique Hospitalo - Facultaire Erasme - ULB) in Brussels, and the Parkway International Ethics Committee in Singapore. The front page of each survey included a written description of the nature and purpose of the study, and a statement that participation was voluntary. Participants were informed that data would be anonymous and that they could choose not to complete the survey or choose not to answer certain questions with no consequences for their participation in the Pfizer phase 1 study. Completion of the survey signified participant consent.

Results

Participants were predominantly male (83.4%), with an average age of 34.7 (± 9.7) years (Table 1). The majority was single (69.7%), and approximately two thirds had more than a high school education. Overall, 33% were unemployed; significantly more in the US than in Belgium or Singapore. Almost half reported an annual household income equivalent to or less than $25,000 USD, and 83% an annual income less than or equivalent to $50,000. In contrast to the US and Belgium, 11.2% of Singapore respondents reported annual incomes of >$100,000. Most respondents (98.7%) reported excellent or good health. The racial and ethnic profile of the study population varied by region (Table 1); 9.4% of total participants described themselves as Hispanic/Latino, all but 1 of whom were in the US. Among US participants, more than half reported to be African American and only 30% white or Caucasian.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of Pfizer Phase 1 healthy volunteers

| Belgium (N=400) |

Singapore (N=300) |

US (N=494) |

Total (N=1194) |

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 27.5% (107) | 8.4% (23) | 12.4% (59) | 16.6% (189) | <.0001 |

| Male | 72.5% (282) | 91.6% (250) | 87.6% (418) | 83.4% (950) | ||

| Age | Years, mean ± SD | 36.9 ± 9.7 | 30.1 ± 7.9 | 35.7 ± 9.8 | 34.7 ± 9.7 | <.0001 |

| Education a | High School or less | 42.0% (162) | 30.7% (89) | 32.9% (157) | 35.4% (408) | .0036 |

| Some College, University or Graduate School | 58.0% (224) | 69.3% (201) | 67.1% (320) | 64.6% (745) | ||

| Employment | ||||||

| Part-time | 20.9% (50) | 37.1% (56) | 68.4% (134) | 41.0% (240) | ||

| Not employed | 22.3% (89) | 25.3% (76) | 45.3% (224) | 32.6% (389) | ||

| Student | 12.0% (48) | 17.0% (51) | 12.4% (61) | 13.4 % (160) | ||

| Household Income b | <$ 25,000 | 38.5% (120) | 45.7% (123) | 54.6% (248) | 47.4% (491) | <.0001 |

| $25,000-$49,999 | 45.2% (141) | 34.2% (92) | 30.6% (139) | 35.9% (372) | ||

| $ 50,000-$100,000 | 15.7% (49) | 8.9% (24) | 13.4% (61) | 13.0% (134) | ||

| >$100,000 | 0.6% (2) | 11.2% (30) | 1.3% (6) | 3.7% (38) | ||

| Race | Asian | 0.8% (3) | 97.9% (277) | 4.5% (20) | 27.4% (300) | <.0001 |

| Black or African | 8.9% (33) | 0 | 52.5% (233) | 24.3% (266) | ||

| White or Caucasian | 81.3% (300) | 1.1 % (3) | 30.2% (134) | 39.9% (437) | ||

| Mixed | 6.5% (24) | 0.4 % (1) | 6.1% (27) | 4.7% (52) | ||

| Other | 2.4% (9) | 0.7 % (2) | 6.8% (30) | 3.7% (41) | ||

| Marital Status | Divorced/Sep arated | 18.4% (70) | 6.9% (20) | 9.3% (44) | 11.7% (134) | <.0001 |

| Single | 55.5% (211) | 73.3% (214) | 78.9% (373) | 69.7% (798) | ||

| Married | 26.1% (99) | 19.9% (58) | 11.8% (56) | 18.6% (213) | ||

| Type of Community | City | 46.1% (178) | 60.6% (172) | 67.0% (321) | 58.4% (671) | <.0001 |

| Rural/Small town | 45.9% (177) | 14.44% (41) | 9.0% (43) | 22.7% (261) | ||

| Suburban | 8.0% (31) | 25.0% (71) | 24.0% (115) | 18.9% (217) | ||

| Proximity to Study Site | Within 20 miles | 35.8% (137) | 73.9% (215) | 15.9% (75) | 37.2% (427) | <.0001 |

| >20 miles | 64.2% (246) | 26.1% (76) | 84.1% (398) | 62.8% (720) | ||

| Type of Healthcare Coverage c | Public/Government | NA | 60.3% (181) | 34.4% (170) | 41.3% (308) | <.0001 |

| Private | NA | 18.0% (54) | 20.7% (102) | 16.5% (123) | <.0001 | |

| None/Out of pocket | NA | 29.7% (89) | 38.1% (188) | 33.0% (246) | <.0001 | |

| Health Status d | Excellent | 71.7% (274) | 51.6 % (147) | 78.5% (372) | 69.5 % (793) | .03 |

| Good | 27.8% (106) | 44.2% (126) | 21.3% (101) | 29.2 % (333) | ||

| Previous Studies | Number, mean ± SD | 4.6 ± 5.5 | 2.7 ± 4.2 | 5.7 ± 17.2 | 4.6 ± 11.8 | .0047 |

For all data, percentages (%) are based on the total number of responses to each question as the denominator, which may vary, and may not add up to the total regional group denominators. Mean and standard deviation (SD) are reported for age and number of previous studies.

Levels of education were specific to each region (i.e., Belgium, Singapore, or the US); responses are reported according to US categories.

Income ranges were specific to each region’s respective currency (e.g., Euros in the Belgian questionnaire; Singapore $ in Singapore) and are reported in US categories.

Participants in Singapore and the U.S. (but not Belgium) were asked how they paid for their health care; Participants were asked to select all that apply, so multiple options are applicable.

Fair and poor were also health status response options; 14 people (1%) selected fair, and 1 individual selected poor.

Other socio - demographic characteristics varied by region, with more than half of the female participants in Belgium (56.6%), and Belgian participants reporting less education and more full - time employment than those in Singapore and the US (Table 1).

Approximately 70% of participants reported previous clinical research experience with a mean of 4.6 previous studies. Previous experience was more likely in males than females (84.9% vs. 15.1%, p=0.0072), those employed than those unemployed (64.3% vs. 35.7%, p<0.0001), those with an annual income greater than $25,000 more than those who reported less than $25,000 (56.7% vs. 43.3%, p<0.0001), and participants in the US (71.7%) and Belgium (74.1%) more than in Singapore (62.5%, p<0.0001). Those with previous research experience were also older on average (36.2 ± 9.3 vs. 31.1 ± 9.7 years, p<0.0001).

Motivating factors for participation

Main motivation.

Participants were asked to indicate one main reason for wanting to join a Pfizer study (Figure 1). The most commonly reported motivation was interest in the money (57.6%), followed by interest in helping to develop medicines (11.1%), a positive experience in past studies (8.3%), an interest in the science involved in the study (4.2%), and advice from family or friends (2.4%). There were no statistically significant associations between primary motivation and gender, education, income, employment, region, or age. Holding all characteristics constant in multivariable models, those who had never previously participated in a research study rated the influence of family/friends three times higher than those with prior research experience (OR=3.41, 95% CI: 1.62 – 7.19). (See online Appendix in Supplementary Table 3A.)

Figure 1. Main motivations for the enrollment among healthy volunteer phase 1 Pfizer drug development participants.

Participants were asked to select the main reason for their participation. If a main reason could not be chosen, they were asked to rank the reasons. Those who chose only one or ranked a reason as first are included among the data presented as “first reason.” The data are also shown by indication of any importance (either as primary choice or a lower rank).

Factors important to enrollment decision.

Most respondents said that the amount of money (93.7%) was moderately or very important to their decision (Table 2). More than 80% of respondents also rated several other factors as moderately or very important factors in their decision to participate, including study risks, the competence and friendliness of the CRU staff, contributing to medical research, and helping future patients. The majority (88.5%) reported feeling no pressure to join the study, but for those who felt any pressure, the source of reported pressure was most often their financial situation and rarely other people.

Table 2.

Healthy volunteer rating of factors important to their decision to enroll in Phase 1 drug development research

| Not important or slightly important | Moderately or very important | |

|---|---|---|

| Amount of money (n=1167) | 6.3 | 93.7 |

| Competence of CRU staff (n=1158) | 16.4 | 83.6 |

| Friendliness of CRU staff (n=1146) | 17.2 | 82.8 |

| Risks involved (n=1134) | 19.1 | 80.9 |

| Contributing to medical research (n=1156) | 20.0 | 80.0 |

| Helping future patients (n=1168) | 20.3 | 79.7 |

| Study purpose (n=1151) | 25.4 | 74.6 |

| Quality of CRU facility (n=1158) | 25.6 | 74.4 |

| Amount of time (n=1151) | 26.7 | 73.3 |

| Return visits (# and schedule) (n=1156) | 27.9 | 72.1 |

| Type of drug (n=1151) | 33.6 | 66.4 |

| Number and type of painful procedures (n=1135) | 37.6 | 62.4 |

| Location of CRU (n=1157) | 41.5 | 58.5 |

| Form of drug (n=1155) | 42.7 | 57.3 |

| Frequency of taking drug (n=1143) | 43.9 | 56.1 |

| Other participants (n=1152) | 72.7 | 27.3 |

The data above represent percentages (%) of responses.

There were no socio - demographic differences among those who indicated that the amount of money, study risks, or helping future patients was an important consideration in their enrollment decision. Women chose study purpose as an important factor more often than men (OR=2.15, 95% CI: 1.29 – 3.57). Employed respondents rated the number and schedule of visits as more important than the unemployed (OR=1.73, 95% CI: 1.22 – 2.46). Those without previous research experience rated time (OR=0.63, 95% CI: 0.44 – 0.92), the number and schedule of visits (OR=0.61, 95% CI: 0.42 – 0.87), and the quality of the facility (OR=0.67, 95% CI: 0.46, 0.97) as less important to their decisions than those with experience. Belgian participants were more likely than US participants to say contributing to medical research (OR=2.11, 95% CI:1.34 – 3.37) and time was important (OR=1.94, 95% CI: 1.27 – 2.98); and less likely to select study purpose (OR=0.49, 95% CI:0.33 – 0.72), the number and type of painful procedures (OR=0.51, 95% CI: 0.35 – 0.73), drug form (OR=0.37, 95% CI: 0.26 – 0.53) or type (OR=0.36, 95% CI: 0.25 – 0.53), facility location (OR=0.40, 95% CI: 0.27 – 0.57), or other participants (OR=0.43, 95% CI: 0.27 – 0.67) as important to their decision. (See online Appendix for Supplementary Table 3B).

Paired choices between motivations.

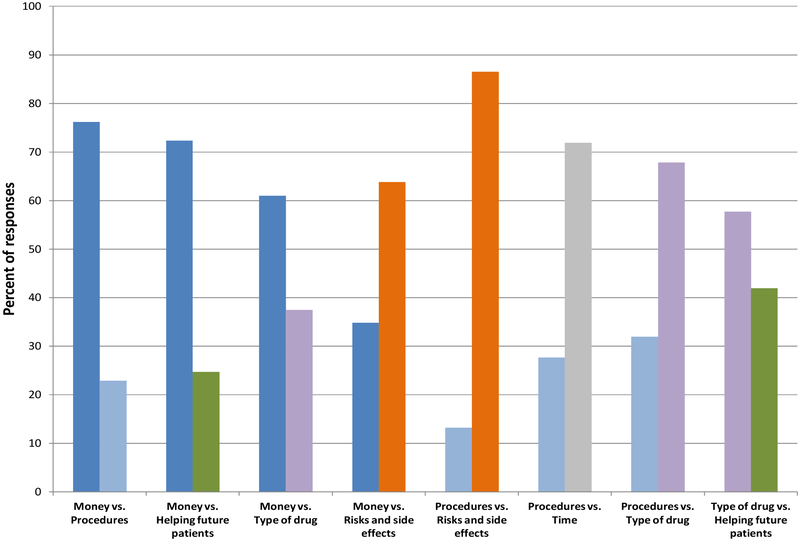

Risks and side effects were ranked as more important than the amount of money in the paired choices that included risk as one option, (63.8% risks versus 34.8% money). In other paired questions, participants rated the amount of money as more important than helping future patients (72.3% money versus 24.7% helping future patients), the number and type of painful procedures (76.2% money versus 22.9% procedures), and the type of drug being studied (61.0% money versus 37.5% type of drug). Participants rated risks and side effects as more important than the number and type of painful procedures (86.5% risks versus 13.2% procedures) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Responses to trade-off questions as reported by healthy volunteers participating in phase 1 Pfizer drug development studies.

Participants were asked to indicate which of the trade-off factors was more important to their decision on whether or not to join the study. The percent of responses are shown for each pair of factors included in the survey.

Money = “The amount of money offered”

Procedures = “The number and type of painful procedures”

Helping future patients = “How much the study helps future patients”

Type of drug = “The type of drug (e.g. psychiatric, blood pressure, etc.)”

Risks and side effects = “Possible risks and side effects from study medications”

Time = “The amount of time I would have to spend at the Pfizer CRU”

Differences by gender, region, and previous research experience were seen on univariable and multivariable analyses in paired factor choices important to the enrollment decision (See online Appendix for Supplementary Table 3C). Women were less likely than men to choose the amount of money over helping future patients (OR=0.42, 95% CI: 0.27 – 0.67), the number and type of painful procedures (OR=0.53, 95% CI: 0.34 – 0.82), the risks and side effects (OR=0.35, 95% CI: 0.21 – 0.57), and the type of drug (OR=0.45, 95% CI: 0.30 – 0.68). Respondents with no previous research experience were less likely to choose the amount of money over helping future patients (OR=0.56, 95% CI: 0.38 – 0.81), and over the number and type of painful procedures (OR=0.60, 95% CI: 0.41 – 0.87). Respondents with more education were more likely to choose the amount of money over helping future patients (OR=1.58, 95% CI: 1.10 – 2.28).

Reasons research was chosen over other options.

More than a third (39.9% as first reason, 52.9% as any reason) explained the main reason they chose to enroll in research rather than earn money in a part - time job or some other way was because it would leave them more time to do other things, others said they wanted to receive the money right away (17.5% first reason, 35.9% any reason), that research gave them a “sense of purpose” (13.9% first reason, 31.7 % any), that the study location was convenient (5.7% first, 25.6% any) or that joining a study was easier than getting a job (4.3% first, 17.5% any). Holding socio - demographic characteristics constant in multivariable logistic regression analyses, those with previous research experience were less likely to say that they chose research participation because it left them more time to do other things (OR=0.63, 95% CI: 0.45 – 0.87), and the employed were less likely to indicate that joining a study was easier than getting a job (OR=0.46, 95% CI: 0.31 – 0.68) (See online Appendix for Supplementary Table 3D). Further, Singapore respondents were more likely than those in Belgium or the US to indicate that they chose research because of a convenient location (OR=1.86, 95% CI: 1.24 – 2.81) or because research gave them a sense of purpose (OR=1.94, 95% CI: 1.30 – 2.90).

Reasons for choosing the particular study.

Reasons given for choosing the particular phase 1 study were that the study was shorter in duration (32.0%), offered more payment than other studies (20.6%), was the only study available (13.9%), had few or more reasonable procedures (11.7%), or was the most interesting study (6.5%). Belgian participants, women, and the employed were more likely than others to say they chose the study because it was shorter and less likely to say because it pays more (p<0.0001 for each; Table 4).

Table 4.

Distribution of the main reason for choosing the particular phase 1 study over others by socio-demographic characteristics

| Main reason chosen | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shorter study |

Study pays more |

More appealing drug |

Fewer / better procedures | Most interesting study |

No other study available | |

| Overall (n=1128) | 32.0 | 20.6 | 5.0 | 11.7 | 6.5 | 13.9 |

| Region: * | ||||||

| Belgium (n=315) | 44.8 | 11.4 | 7.3 | 14.6 | 7.9 | 14.0 |

| Singapore (n=269) | 33.5 | 26.0 | 3.7 | 11.5 | 5.6 | 19.7 |

| US (n=427) | 30.4 | 29.5 | 5.4 | 12.9 | 7.7 | 14.1 |

| Sex: * | ||||||

| Female (n=155) | 40.7 | 9.0 | 12.9 | 15.5 | 3.2 | 18.7 |

| Male (n=828) | 34.5 | 25.4 | 4.1 | 12.8 | 7.9 | 15.3 |

| Education: | ||||||

| College or higher (n=643) | 37.2 | 22.6 | 5.6 | 12.6 | 6.4 | 15.7 |

|

High School or less (n=352) |

33.0 | 23.3 | 5.4 | 14.2 | 8.5 | 15.6 |

| Income: | ||||||

| <$25,000/yr (n=433) | 31.9 | 26.1 | 5.1 | 12.5 | 7.4 | 17.1 |

|

$25,000 or more/yr (n=466) |

38.6 | 21.0 | 4.9 | 14.6 | 6.2 | 14.6 |

| Employment: * | ||||||

| Employed (n=502) | 43.2 | 18.5 | 4.8 | 12.4 | 6.6 | 14.5 |

| Not employed (n=344) | 25.6 | 27.9 | 5.8 | 13.4 | 9.0 | 18.3 |

|

Age, in years (n=957) (mean ± SD) |

34.6 ± 9.5 | 34.3 ± 9.4 | 33.6 ± 10.3 | 34.7 ± 9.5 | 36.7 ± 10.5 | 35.0 ± 10.2 |

| Previous experience: | ||||||

| Never (n=266) | 34.2 | 21.1 | 7.5 | 13.9 | 7.9 | 15.4 |

| At least 1 (n=665) | 37.0 | 23.9 | 4.7 | 12.9 | 6.0 | 15.5 |

Data are percentages (%) of the distribution of main reasons within each level of socio demographic characteristic. Age is presented as a continuous variable.

p<0.0001

Discussion

With nearly 1200 volunteers from three countries, this is the largest study to date investigating sociodemographic characteristics, motivations, and enrollment decision considerations of healthy adult volunteers in phase 1 drug development studies. Four findings merit emphasis.

First, decision making about participation in phase 1 drug development trials is indeed multi - factorial. Money is the primary motivation for most phase 1 healthy volunteers, as previously shown.8 Despite this motivation, the majority of participants rated consideration of risks as more important to their enrollment decisions than the amount of money and risks were described as very important to the enrollment decisions of most participants. Other important factors described as important to enrollment decisions were helping others, and the competence of the CRU staff. The amount of money was more important than factors such as helping others; although less often for females and those new to research, and more often for those with more education. Time, in addition to risk and money, is another important consideration for healthy volunteers’ enrollment decisions. Time was the most frequent reason respondents chose research over other income options, and why they chose the particular phase 1 study over other studies. Those who are employed and those with previous research experience were particularly likely to rate time and visit frequency as important to their enrollment decisions. These data lend support to Nancy Ondrusek’s thesis that healthy volunteer enrollment choices are similar to job seeking, in which individuals seek and identify opportunities to earn money through research, and then “shop” through the identified opportunities applying a burden - pay calculus to select the best option.14 In our study, the burdens and pay respondents considered most important to their enrollment decisions were the risks, the time required, and the amount of money offered. Volunteers do evaluate risks before enrollment, and might be further reassured by knowing that adverse events are usually mild for healthy volunteers,3, 16 and that IRBs review risks before approving phase 1 studies.17 Nonetheless, as certain high profile cases demonstrate, serious risk is possible.18, 19

Second, many healthy volunteers in our cohort are indeed low income and unemployed. Half reported annual household incomes equivalent to less than $25,000 USD, a level that falls below the national average in these three high income countries.20–22 In the US, for example, the lowest fifth of households earns approximately $20,000 annually.20 Our cohort also reported unemployment at 3 or more times the national average in each of their countries.23 These healthy volunteers are certainly people who need money and are often unemployed, they may in fact be those who “have time to spare … and are living on the margins.”10 Despite this, income appeared to make no difference in stated motivations or the ranking of factors important to enrollment decision making. Employment also did not influence motivations or factors important to decision making, with the exception of time which was rated as a more important consideration by those who are employed. Phase 1 studies require committed time in the CRU facility, which may be difficult for those who are otherwise employed. The most common explanation offered by respondents for why they chose research over a part - time job, that it gives them time to do other things, illustrates that choosing research participation could allow individuals to make money through research while preserving the opportunity to pursue other interests when they are not participating in a study. Of note, more than half of the US cohort were African American, a significant overrepresentation relative to the proportion of African Americans in the US population.24 As noted by Fisher and Kalbaugh, this overrepresentation may be characteristic of phase 1 research, especially conducted in the northeast US, and is in striking contrast to existing data on African American representation in later phase trials and clinical research overall.25 Tracking race and ethnicity data of participants by trial phase or type would help us to better understand participation rates, and to address the ethical implications of disproportionate participation.

Third, the majority of healthy volunteers had extensive previous research experience, with an average of 4.6 previous studies. Individuals with previous research experience tended to be male, older, employed, and have a higher average income, groups that are not the most likely to be vulnerable to exploitation. We found no association in our cohort between previous research experience and education in contrast to Kass et al., who reported that those without college degrees were almost nineteen times as likely as those with college degrees to have participated in more than 10 studies.26 Previous research experience did make a difference, however, in the factors that individuals reported important to their enrollment decisions. Experienced participants reported more interest in the amount of money, the amount of required time, the number of visits, and the quality of the facility compared to other respondents. These data suggest that experienced participants in particular may “shop” for certain kinds of research studies to join, and their choices may reflect an attempt to replicate positive experiences from previous research and not repeat negative ones. With experience, individuals may be more likely to know that there are significant choices among studies, and thus choose studies that are shortest in time, with the least risk, and the best offer of payment. Although commentators express concerns about the ethical and methodological consequences of repeat research participation,13 to the extent that “professional” volunteers with more experience are more selective in their enrollment decisions, they may be more able to protect their own interests than research - naïve subjects.

Finally, there are interesting differences by region in the sociodemographic characteristics of volunteers and the factors they select as important to research decisions. Participants in Belgium, for example, were more likely to be female, employed, Caucasian, married, older, with less education but more income than those in either the US or Singapore. These differences were associated with differences in factors important to their enrollment decisions, as Belgian participants were more often motivated by contributing to medical research and less concerned about procedures, type and frequency of drug, and other factors. Understanding regional differences in motivations and decision making processes can help inform recruitment and informed consent processes in various locations.

Limitations

Our data are limited because they represent self - reported responses to surveys from healthy volunteers considering enrollment in phase 1 studies at in house CRU sites associated with Pfizer, a single pharmaceutical company. These volunteers may differ from those who participate at contract research organizations, universities, and possibly other pharmaceutical companies. On the other hand, responses to anonymous self - administered surveys may be more honest than interviews. Further, participants were assigned unique identification numbers and advised not to take the survey more than once; repeat identification numbers were not found. However, if individuals misrepresented themselves in order to sign up for more than one Pfizer study during the survey period, though highly unlikely, it is possible that they also could have taken the survey more than once.

Conclusion

Healthy volunteers in this cohort on three continents rated risk as the most important consideration to their enrollment decisions in phase 1 trials, while still primarily motivated to participate because of financial compensation. Risk, time, and payment are all important considerations in healthy volunteer decisions about research participation. This large cohort of healthy volunteers are characterized by low incomes and high rates of unemployment relative to their country’s population, yet the factors they consider when deciding to enroll in research do not vary by income or employment. The significant number of experienced research participants are not more disadvantaged than the less experienced and report selecting studies based on multiple factors, including time, risk, money, and the quality of the facility and staff. Data such as these can help inform recruitment practices for phase 1 studies and alleviate some concerns about distorted judgment among healthy volunteers.

Supplementary Material

Table 3.

Results from multivariable logistic regression analyses of socio-demographic characteristics and paired choices of factors important to enrollment decisions of healthy volunteer participants in Pfizer phase 1 drug development studies.

| Socio-Demographic Characteristic | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motivating Factors for Enrollment in Pfizer Study: (outcome modeled) |

Region (US vs. Belgium; US vs. Singapore) |

Gender (Female vs. Male) |

Education (College+ vs. ≤ High School) |

Income (<$25,000/yr vs. $25,000/yr+) |

Employment (Employed vs. Non-employed) |

Age (in years) |

Previous Research Experience (Never vs. at least 1) |

| Number/type of painful procedures vs. Time at CRU (procedures) |

Belgium: 0.35 (0.23–0.53)** Singapore: 0.61 (0.40–0.93) |

1.57 (1.00–2.46) |

0.81 (0.57–1.15) |

0.70 (0.49–0.99)* |

0.99 (0.97–1.00) |

1.51

(1.05–2.17)** |

|

| Number/type of painful procedures vs. Money (money) | Belgium: 1.42 (0.93–2.19) Singapore: 1.07 (0.68–1.68) |

0.53

(0.34–0.82)** |

1.10 (0.76–1.59) |

1.04 (0.72–1.50) |

0.92 (0.63–1.34) |

1.00 (0.98–1.02) |

0.60

(0.41–0.87)** |

| Number/type of painful procedures vs. Type of drug (procedures) | Belgium: (1.06–2.22) Singapore: (1.04–2.32) |

0.66 (0.43–1.02) |

1.11 (0.80–1.54) |

0.91 (0.66–1.25) |

1.31 (0.93–1.82) |

0.97 (0.97–1.00) |

1.14 (0.80–1.61) |

| Type of drug vs. Helping future patients (drug) | Belgium: 0.82 (0.57–1.17) Singapore: 1.06 (0.71–1.57) |

1.54 (1.01–2.36)* |

0.98 (0.71–1.34) |

0.78 (0.57–1.07) |

1.10 (0.80–1.52) |

0.99 (0.97–1.01) |

0.51

(0.37–0.71)** |

| Number/type of painful procedures vs. Possible risks/side effects (procedures) | Belgium: 1.19 (0.71–1.98) Singapore: 0.99 (0.56–1.74) |

0.55 (0.28–1.09) |

0.77 (0.49–1.20) |

0.71 (0.45–1.12) |

1.20 (0.75–1.92) |

1.00 (0.97–1.02) |

1.18 (0.73–1.90) |

| Money vs. Helping future patients (money) | Belgium: 1.78 (1.14–2.77); p=0.0168* Singapore: 1.12 (0.71–1.77) |

0.42

(0.27–0.67)** |

1.58

(1.10–2.28)** |

0.74 (0.51–1.07) |

1.32 (0.91–1.91) |

0.98 (0.96–1.00) |

0.56

(0.38–0.81)** |

| Money vs. Type of drug (money) | Belgium: 1.55 (1.06–2.25) Singapore: 1.20 (0.81–1.80) |

0.45

(0.30–0.68)** |

1.07

(0.77–1.48) |

1.05 (0.76–1.44) |

1.34 (0.97–1.86) |

1.00 (0.98–1.02) |

0.74

(0.53–1.04) |

| Risks/side effects vs. Money (money) | Belgium: 1.06 (0.73–1.53) Singapore: 0.93 (0.62–1.39) |

0.35

(0.21–0.57)** |

0.81

(0.58–1.11) |

1.05 (0.76–1.45) |

1.30 (0.93–1.81) |

1.00 (0.98–1.02) |

0.74

(0.52–1.05) |

All results are from multivariable logistic regression models, and are reported as Odds Ratio (95% Confidence Intervals). Results in bold and italics indicate those that were consistently statistically significant by various analytic methods [statistically significant (p<0.05) * in multivariable logistic regression models, and statistically significant (p≤0.01) ** in both univariable logistic regression models and Fisher’s exact tests]. As confidence intervals are more informative, p values are not reported.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the participants for their responses to the survey; the research staff in New Haven, Brussels, and Singapore for their invaluable support in collecting the data; and fellows and students at the NIH Department of Bioethics who helped with survey development and data entry.

Funding

This research was funded by NIH Intramural Research Funds through the Department of Bioethics in the NIH Clinical Center.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimer: The opinions expressed are those of the authors. They do not reflect any positions or policies of Pfizer Inc. or of the National Institutes of Health, U.S. Public Health Service, or Department of Health and Human Services.

Declaration of conflicting interests

Dr. Emanuel is a frequent paid event speaker at conventions, committee meetings and professional healthcare gatherings represented by the Leigh Bureau. He is also venture partner with Oak HC/FT and a Nuna stockholder. The other authors declared that they have no conflicting interests to report.

References

- 1.ClinicalTrials.gov. Glossary of common site terms, https://www.clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/info/glossary#P (Accessed 10 August 2015)

- 2.CenterWatch. Overview of clinical trials, http://www.centerwatch.com/clinicaltrials/overview.aspx (Accessed 15, November 2016).

- 3.Emanuel EJ, Bedarida G, Macci K, et al. Quantifying the risks of non - oncology phase I research in healthy volunteers: meta - analysis of phase I studies. BMJ 2015; 350:h3271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pasqualetti G, Gori G, Blandizzi C, et al. Healthy volunteers and early phases of clinical experimentation. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2010; 66: 647–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Agrawal M, Grady C, Fairclough DL, et al. Patients’ decision - making process regarding participation in phase I oncology research. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 4479–4484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stryker JE, Wray RJ, Emmons KM, et al. Understanding the decisions of cancer clinical trial participants to enter research studies: Factors associated with informed consent, patient satisfaction, and decisional regret. Patient Educ Couns 2006; 63: 104–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Almeida L, Azevedo B, Nunes T, et al. Why healthy subjects volunteer for phase I studies and how they perceive their participation. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2007; 63: 1085–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stunkel L and Grady C. More than the money: A review of the literature examining healthy volunteer motivations. Contemp Clin Trials 2011; 32: 342–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elliott C and Abadie R. Exploiting a research underclass in phase 1 clinical trials. N Engl J Med 2008; 358: 2316–2317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elliott C. Guinea - pigging: Healthy human subjects for drug safety trials are in demand. But is it a living? New Yorker 2008: 36–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iltis AS. Payments to normal healthy volunteers in phase 1 trials: Avoiding undue influence while distributing fairly the burdens of research participation. J Med Philos 2009; 34: 68–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stones M and McMillan J. Payment for participation in research: a pursuit for the poor? J Med Ethics 2010; 36: 34–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tishler CL and Bartholomae S. Repeat participation among normal healthy research volunteers: professional guinea pigs in clinical trials? Perspect Biol Med 2003; 46: 508–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ondrusek N Making participation work (Ondrusek N).2010. Unpublished doctoral dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Helms R Guinea Pig Zero, http://www.guineapigzero.com/ (Accessed 15 November 2016)

- 16.Halpern S Financial incentives for research participation: empirical questions, available answers, and the burden of further proof. Am J Med Sci 2011; 342: 290–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emanuel EJ. Undue inducement: Nonsense on stilts. Am J Bioeth 2005; 5: 9–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wadman M London’s disastrous drug trial has serious side effects for research. Nature 2006; 440: 388–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Enserink M French company bungled clinical trial that lead to death and illness. Science magazine, http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2016/02/french-company-bungled-clinical-trial-led-death-and-illness-report-says (2016, accessed 15 November 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 20.United States Census Bureau. Table H 1. Income limits for each fifth and top 5 percent of all households: 1967 to 2014,https://www.census.gov/hhes/www/income/data/historical/household (Accessed date)

- 21.Credit Suisse Global Wealth Data Book 2013. Table 3.1 Wealth patterns within countries, https://publications.credit-suisse.com/tasks/render/file/index.cfm?fileid=17711FFC-0524-76AB-CEB0FE206E46C125 (Accessed 15 November 2016).

- 22.The World Bank GDP Per Capita in USD, http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD?order=wbapi_data_value_2012+wbapi_data_value+wbapi_data_value-last&sort=descow (Accessed 15 November 2016).

- 23.The World Bank DataBank. Unemployment, total (% of total labor force), http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.TOTL.ZS (2016, Accessed 15 November 2016).

- 24.US Census Bureau. Annual estimates of the resident population by sex, race, and Hispanic origin for the United States, states, and counties: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015, 2015 population estimates, https://factfinder.census.gov/faces/tableservices/jsf/pages/productview.xhtml?src=bkmk (Accessed 15 November 2016).

- 25.Fisher JA and Kalbaugh CA. Challenging assumptions about minority participation in US clinical research. Am J Public Health 2011; 101: 2217–2222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kass NE, Myers R, Fuchs EJ, et al. Balancing justice and autonomy in clinical research with healthy volunteers. Clin Pharmacol Ther 2007; 82: 219–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.