Abstract

Context:

Children with cancer and their families have complex needs related to symptoms, decision-making, care planning, and psychosocial impact extending across the illness trajectory, which for some includes end of life. Whether specialty pediatric palliative care (SPPC) is associated with improved outcomes for children with cancer and their families is unknown.

Objective:

We conducted a systematic review following PRISMA guidelines to investigate outcomes associated with SPPC in pediatric oncology with a focus on intervention delivery, collaboration, and alignment with National Quality Forum domains.

Methods:

We searched PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, and CINAHL databases from inception until April 2020, and reviewed references manually. Eligible articles were published in English, involved pediatric patients aged 0–18 years with cancer, and contained original data regarding patient and family illness and end-of-life experiences, including symptom management, communication, decision-making, quality of life, satisfaction, and healthcare utilization.

Results:

We screened 6,682 article abstracts and 82 full-text articles; 32 studies met inclusion criteria, representing 15,635 unique children with cancer and 342 parents. Generally, children with cancer who received SPPC had improved symptom burden, pain control, and quality of life with decreased intensive procedures, increased completion of advance care planning and resuscitation status documentation, and fewer end-of-life intensive care stays with higher likelihood of dying at home. Family impact included satisfaction with SPPC and perception of improved communication.

Conclusion:

SPPC may improve illness experiences for children with cancer and their families. Multi-site studies utilizing comparative effectiveness approaches and validated metrics may support further advancement of the field.

Keywords: pediatric, cancer, palliative care, hospice, integration, review

Introduction

Despite ongoing advances in therapy, cancer remains the leading cause of death by disease among children in the United States, with one in five children dying from their illness.1 The global burden of childhood cancer likely remains underestimated,2 but recent projections appraise children in low-and middle-income countries to be four times more likely to die of cancer than children in high-income countries.3 Across an advancing disease trajectory, children with cancer and their families face significant physical, psychosocial, and spiritual challenges,4–8 engendering opportunities for integration of expert guidance to manage symptoms, optimize quality of life, delineate care aligned with goals and preferences, garner supportive services, strive for comfort and dignity at the end of life, and offer bereavement support to caregivers.9 Improving access to palliative care for children with cancer has been identified as a major challenge and priority on a global level.10

Over the past decade, integration of specialty pediatric palliative care (SPPC) within pediatric cancer care has developed in response to the unique needs of children with progressive cancer and their families.9,11 Specialty palliative care refers specifically to the holistic medical, psychosocial, and spiritual care provided by an interdisciplinary team of trained professionals, with the goals of promoting quality of life, mitigating suffering, supporting decision-making, assisting with care coordination, guiding end-of-life management, and tending to grief and bereavement needs.12 The perceived “value-added” of SPPC in oncology has gained traction

over the past several years,13–16 with recent growth of combined training programs in pediatric oncology and hospice and palliative medicine further emphasizing the benefits of early integrated care.17 In medical oncology, the feasibility and effectiveness of specialty palliative care has been rigorously investigated, with a developing body of literature demonstrating improved outcomes for adults who receive cancer-directed care alongside palliative care, bolstering rationale of integrated care models.18–24 In pediatric oncology, research on the benefits of integrated palliative care has lagged behind the adult sector; however, an increasing literature suggests that involvement of SPPC services within routine cancer care for children with high-risk disease may improve symptoms7,25 and quality of life for children and families.26–29

Based on data emerging from the pediatric non-oncology population, several systematic reviews have investigated the impact of SPPC on children with serious illness within the last five years. Although relatively limited in scope, these reviews suggest a spectrum of benefits associated with SPPC, including improvements in the child’s quality of life and symptom control, family perceptions of support, and time spent in non-hospital care settings.30–32 In recent years, two systematic literature reviews have been conducted related to SPPC in pediatric cancer. The first synthesized studies that assessed the timing of SPPC involvement for children with cancer, demonstrating that introduction of palliative care services typically occurs late in the illness course and nearly half of children who die never receive palliative care services.33 The second review examined the impact of SPPC on children and young adults with cancer, including factors affecting access to SPPC and potential barriers to care integration.34 These reviews contributed meaningfully to advance the field; at the same time, neither review focused exclusively on SPPC as an intervention, synthesizing studies that compared the experiences of children with cancer and their families who received SPPC to those without SPPC. To gain better understanding of the potential benefits of SPPC in pediatric oncology, investigation of studies that utilize a comparator arm, allowing some assessment of a SPPC intervention compared with usual care, may be helpful.

Towards this purpose, we conducted the following systematic reassessment of the present evidence base regarding the impact of SPPC in pediatric oncology. This review aims to synthesize and present current knowledge on the impact of SPPC integration in the care of children with cancer, with the goal of describing outcome findings alongside a concurrent assessment of intervention content, delivery, mechanisms for oncology-palliative care collaboration, outcome reporting sources, measurement tools, feasibility, acceptability, and alignment with National Quality Forum (NQF) domains (i.e., Physical aspects of care, Structure and processes of care, Psychiatric and psychological aspects of care, Cultural aspects of care, Spiritual aspects of care, Social aspects of care, Care of the imminently dying, Ethical and legal aspects of care).35 PICOTS question and inclusion/exclusion criteria are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Study Eligibility Criteria

| PICOTS question: Is involvement of SPPC, compared to usual care alone, associated with changes in outcome related to child/family experience (e.g. symptoms, quality of life, parent bereavement), health care utilization, markers of goal-concordant care or opportunity to plan, or patterns of end of life care? | |

| Population: Children with cancer and their families | |

| Intervention: SPPC involvement/integration | |

| Comparator: Absent or usual (i.e., late/delayed) involvement of SPPC | |

| Outcomes: Quantitative metrics related to child/family outcomes; downstream health care utilization; processes related to goal-concordant care or opportunity to plan such as communication, decision-making and advance care planning; details related to SPPC-oncology collaboration; patterns of end-of-life care; bereavement outcomes; and SPPC intervention timing, delivery, feasibility and acceptability | |

| Timing: From cancer diagnosis through end of life and into bereavement Setting: Home, hospice facility, outpatient setting, inpatient setting | |

|

| |

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

|

| |

| • Original research involving data on children or adolescents (aged </= 18 years) with cancer and/or their families anytime from diagnosis through EOL • Published before April 4, 2020 • Investigates SPPC involvement and associated outcomes • Has a comparator arm (see above) • Includes at least one outcome measure (described above) • Study design can include: prospective (e.g. experimental) studies or observational studies (e.g., cohort studies; retrospective and cross-sectional studies) |

• Studies about knowledge, attitudes or beliefs about PPC • Case reports, letters, commentaries, reviews, or gray literature including abstracts and non-peer reviewed publications • Studies that lack information regarding specific enrollment numbers for pediatric patients with cancer diagnoses • Articles not published in the English language |

Abbreviations: specialty pediatric palliative care, SPPC

Methods

Search Strategy

We collaboratively developed a search strategy with the guidance of a medical research librarian (C.W.), utilizing keywords and medical subject headings representing palliative care in pediatric oncology. Advanced search strategies for PubMed and other databases are detailed in Supplemental Table 1. We searched six databases (PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Scopus, and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, and Cochrane Library) from inception through April 4, 2020, limiting the search to publications in English, and excluding case reports, letters, commentaries, reviews or gray literature. To evaluate search result comprehensiveness, we confirmed inclusion of studies known to the research team as well as publications included in recent related systematic reviews. The study was registered in Prospero (ID CRD42020167796#).

Study Selection

Search results were uploaded into Covidence,36 a web-based platform for conducting systematic reviews, which identified and removed duplicates. We screened the remaining articles for eligibility based on the criteria in Table 1. Briefly, a study was eligible for inclusion if it reported original data on SPPC for children with cancer and associated outcomes and included a control/comparator. For the purposes of this study, we defined SPPC as services provided by trained, consulting clinicians offering resources and care consistent with the World Health Organization definition of palliative care.37 Outcomes of interest included child/family outcomes; downstream health care utilization; processes related to goal-concordant care or opportunity to plan such as communication, decision-making and advance care planning; patterns of EOL care; details related to PPC-oncology collaboration; bereavement outcomes; and PPC intervention timing, delivery, feasibility and acceptability. We excluded studies that exclusively described knowledge, attitudes or beliefs about PPC.

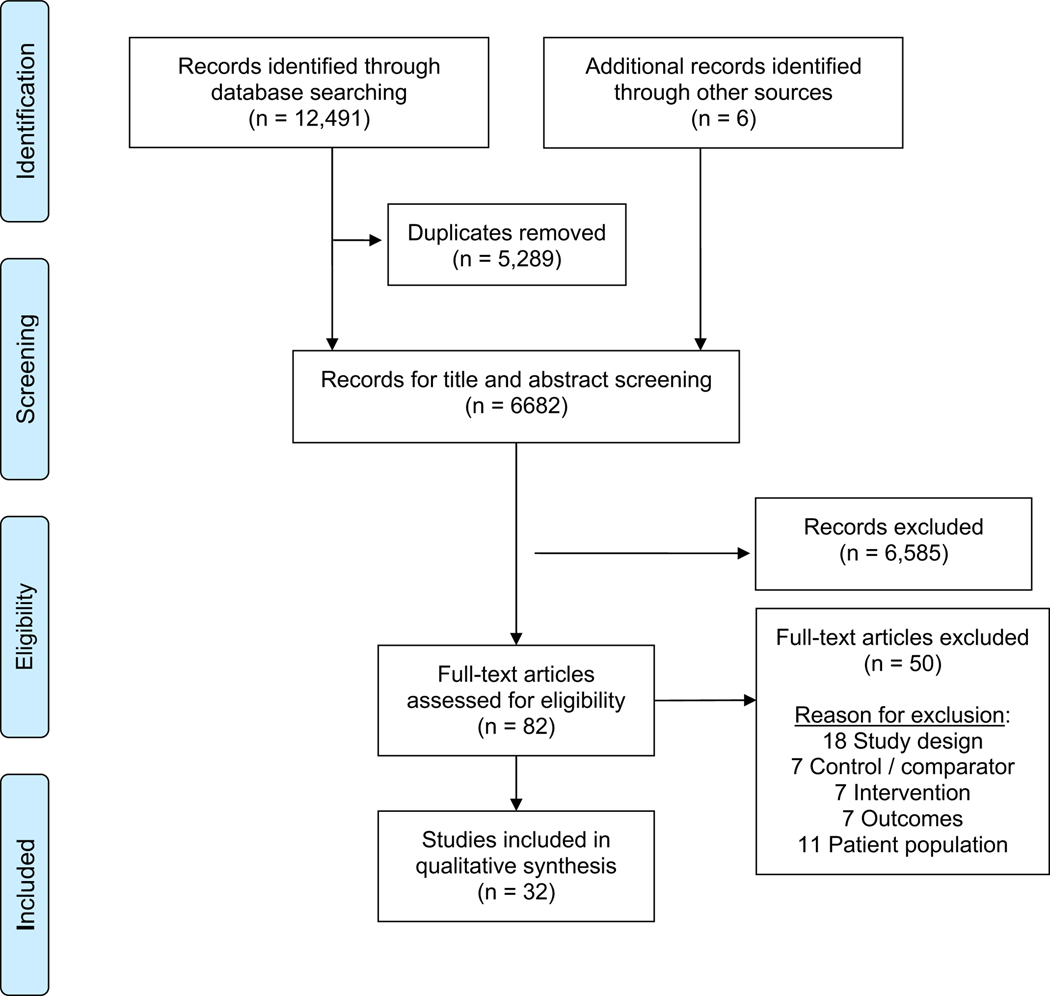

Results of the study selection process are reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis statement guidelines.38 (Figure 1) A team of reviewers (L.D., E.B., J.L., S.E.S., B.S., K.Z., J.A.) received training in screening titles/abstract, and two independent reviewers screened each title and abstract for eligibility, with discrepant determinations adjudicated by the senior author (C.K.U.). The same team of reviewers subsequently reviewed the pre-screened article texts in full, with two team members reviewing each article and the first author (E.C.K) adjudicating discrepancies.

Fig. 1.

Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analysis diagram.

Data Extraction, Quality Assessment, and Analysis

For each article, two authors abstracted data into a preformatted spreadsheet. Data fields included first author, publication year, country, study design, study aim(s), inclusion/exclusion criteria, participant characteristics, intervention type, intervention delivery, control/comparator details, outcome(s) of interest, PPC-oncology collaboration details, which, if any, relevant NQF indicator domains were addressed,35 source of outcome, measurement tool(s), main findings, intervention feasibility, intervention acceptability, and quality appraisal results. To appraise the quality of cohort studies (i.e., to evaluate risk of bias), we utilized the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, which assesses non-randomized case control and cohort studies based on selection of intervention and control groups, comparability of groups, and outcomes.39 Only case control and cohort studies studies meeting specific criteria were eligible for appraisal using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. To maintain consistency across reviews within the Special Series,40 no additional bias assessment tools were applied. Reviewer pairs discussed discrepancies to reach consensus; as needed, further adjudication was conducted by E.C.K., M.E.W, and C.K.U. Findings from the included studies were summarized in tabular form. While heterogeneity of studies and outcomes precluded formal meta-analysis, we assessed the results for patterns and key findings and qualitatively synthesized salient findings.

Results

Excluding duplicates, database searches produced 6,682 articles (Figure 1). Following title and abstract screening, 82 articles remained for full text screening, and ultimately 32 articles met final inclusion criteria. Nineteen studies (59.3%) were conducted in the United States, with the remaining 13 conducted in the United Kingdom, Canada, Germany, Israel, Uganda, India, or New Zealand. All studies were published between 1990 – 2020; however, 28 studies (87.5%) were published within the last decade. Study demographics and findings are summarized in Table 2 and Figures 2–3.

Table 2.

Summary of Study Design, Participants, Comparators, and Main Findings

| Participants | Study Arms | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author, Year Country Aims | Design | Identity | Main Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria | Intervention | Comparator | Main Findings |

|

Amery et al. 2009

Uganda Evaluate PPC service in sub-Saharan Africa |

Retrospective record review; interviews Single site |

Children:n=11 Parents: n=11 Staff: n=10 |

Inclusion: • Children who received PPC; parents, hospital staff |

Team: RN, MD back-up, volunteers Where: Inpatient, outpatient, home Intervention: Needs support, symptom control, chemotherapy, advocacy |

Pre-PPC cohort | PPC associated with increased morphine and chemotherapy prescriptions, basic needs support, treatment adherence |

|

Ananth et al. 2017

U.S. Explore hospital utilization among PPC recipients |

Retrospective record review Single site |

Total: n=109 (cancer. n=38) Female:44% White: 70% Hispanic: 12% Black: 7% |

Inclusion: • Age ≥2 yr • ≥1 admission or ED visit before PPC |

Team: MD, Np, SW Where: Inpatient, outpatient, home Intervention: Assist with goals of care, decision-making/ACP symptom management, psychosocial, spiritual support |

Child’s outcomes pre-PPC |

PPC associated with decrease in hospital admissions and ED visits Mean hospital costs unchanged Among children who died, ICU admission frequency increased |

|

Arland et al. 2013

U.S. Evaluate an EOL program in relation to specific outcomes |

Retrospective medical review Single site |

Children: n=114 |

Inclusion: • Age 1 mo-19 yr • Died of brain tumor |

Team: MD, APN, RN, SW Where: Home Intervention: EOL conversations, symptom treatment, family support |

Pre-PPC cohort |

Program associated with less hospitalization but no decrease in number dying in hospital |

|

Brock et al. 2016

United States Explore associations between demographics and diagnosis with EOL characteristics |

Retrospective record review Single site |

Children: n=445 Female: 42% White:n=373% Asian:17% Black:4% Hispanic: 28% Heme malig:34% Brain tumor:24% Solid tumor:34% Heme:7% Immunologic:2% |

Inclusion: • Age 0–35 yr • Care from hematology/onc ology/HSCT team |

Intervention specifics not described | PPC subgroup analysis: Children who did not receive PPC |

Children with brain/solid tumors enrolled in hospice and died at home more frequently than those with heme malig Frequency of resuscitation status orders and PPC consultation increased over time No increase in hospice enrollment, no shift in LOD |

|

Chang et al. 2013 New Zealand Determine demographic/diagnos tic characteristics associated with LOD |

Retrospective record review; multisite |

Total children: n=494 (cancer n=145) Female:49% Asian:7% Caucasian:52% Maori:28% Pacific peoples:12% |

Inclusion: • Age 28 d-18 yr • Died from terminal illness |

PPC team involvement in the home, hospital, or hospice | PPC subgroup analysis: Children with who did not receive PPC |

Cancer diagnosis and PPC referral: decreased risk of dying in-hospital |

|

Cheng et al. 2019 U.S. Evaluate prevalence of PPC; Determine factors associated with PPC; Assess outcomes, hospital costs associated with PPC |

Retrospective record review Multisite |

Total children n=10,960 Female: 42% Caucasian: 56% |

Inclusion: • Age <18 yr • Diagnosis solid organ or heme malign Exclusion: • Neonates |

Where: Inpatient | Cohort that did not receive PPC | 4% of hospitalizations had PPC PPC associated with solid tumor, older age, shorter LOS PPC associated with lower overall and daily hospital costs |

|

Conte et al. 2016 Canada Examine healthcare utilization of children with PPC compared with those without PPC |

Retrospective record review with matched pairs analysis Single site |

Total: n=22 (cancer n=12) Female: 50% |

Inclusion: • Died from life- threatening condition |

Specifics of PPC intervention not described | Pre-PPC baseline (within cohort comparison; Usual care (between cohort comparison) |

PPC / hospice recipients had more advance directives in place No significant difference in hospital LOS between groups, but PPC/hospice recipients had longer admissions compared to usual care |

|

Duffy et al. 1990 Canada Describe children in PPC program; Compare them to those from pre- PPC; Assess parental satisfaction with PPC |

Retrospective record review; Survey Both single site |

Total children: n=59 (cancer n=44) Parents: n=8 Female:47% |

Inclusion: • Part 1: Admitted to neurosurgical unit • Part 2: Parent of child admitted to PPC who died from CNS tumor |

Team: PPC RN Where: Home When: when illness deemed terminal Intervention: PPC RN visits; Medication advice from pharamcologist |

Part 1: pre-PPC cohort | Children with PPC had fewer hospital days and more time at home at eOl, more likely to die at home High parental satisfaction with PPC |

|

Fraser et al. 2013 U.K. Assess association of PPC with number of hospital admissions |

Retrospective record review Multisite |

Total children:n= 2508 Registry: Heme malig:43% CNS tumor:20% Solid tumor:37% PPC: Heme malig:22% CNS tumor:40% Solid tumor:38% |

Inclusion: • Age 0–19 yr • Died before extraction date • Catchment area resident Linkage of hospital episode statistics and PPC data |

Team:PPC MD Where: hospice house |

Cohort that did not receive PPC | Children referred to PPC had fewer planned and overall admissions and ED visits |

|

Friedrichsdorf et al. 2015 U.S. Compare EOL pain and symptom management in children with advanced cancer who did and did not receive PPC; Identify differences in outcomes |

Retrospective record review and survey Both single site |

Total children: n=60 Caregivers: n=60 Heme malig:38% Brain tumor:38% Solid tumor:23% Female: Child:45% Caregiver:81 % Caucasian:100% |

Inclusion: - Bereaved parent of child who: - Diagnosed with cancer age 0–17 yr - Received care at site for 2:30 days |

Team: PPC MD, RN, SW, CLS, chaplain Where: Home Intervention: Symptom assessment, psychosocial/spiritual care, assistance with community resources |

Cohort that did not receive PPC | No difference in prevalence in symptoms except constipation (higher in PPC group) Similar perceived level of suffering between groups PPC group more likely to report fun in last month of life or having event that added meaning |

| Golan et al. 2008 Israel Evaluate association of Palliative care unit (PCU) with outcomes in children with cancer |

Retrospective Single site |

Total children: n=568 (cancer n=482) Female: 44% Heme malig::43% Brain tumor:15% Solid tumor:27% Heme:9% Other: 6% |

Inclusion: • Admitted to oncology • Died from malignancy |

Team: RN Where: Inpatient, outpatient, home When: Admission prioritized for those with poor prognosis Intervention: Specifics other than bereavement support not described |

Cohort that did not receive PPC | Decline in deaths in general pediatric ward, oncology ward and at home after PCU |

|

Groh et al. 2013 Germany Evaluate whether involvement of PPC home team addresses needs of children and families and acceptance and effectiveness of PPC |

Prospective cohort Single site |

Total children: n=40 (cancer n=10) caregivers: n=40 (cancer n=10) Female: 43% |

Inclusion: • Caregivers of children with cancer |

Team: MD RN, SW, and chaplain Where: Home Intervention: Specialized medical and nursing care, 24/7 on call, psychosocial support, care coordination |

Cohort at time of PPC initiation | After PPC: caregiver care satisfaction improved; less caregiver anxiety/depression |

| Groh et al. 2014 Germany Compare home PC by adult and pediatric teams; Explore differences and similarities in home PC for children and adults |

Prospective cohort Sngle site |

Children: Total n=40 (cancer n=10) Caregivers: n=40 (cancer n=10) Adults: Total n=60 Caregivers: n=53 Children Female 43% |

Inclusion: • Care from home PC team team (child or adult) |

Team: MD RN, SW, and chaplain Where: Home Intervention: specialized medical and nursing care, 24/7 on call, psychosocial support, care coordination |

Cohort at time of PPC initiation and adults receiving PC | Children: Loger PC; greater survival at 6 and 12 mos; PC termination for reason other than death more likely; seizures, dyspnea, impaired speech most burdensome symptoms Adults: more worsening of function; frequently cited weakness, fatigue, and pain; QOL lower Both groups: symptoms, QOL improved after PC |

|

Hays et al. 2006 U.S. Demonstrate feasibility, effectiveness of PPC program |

Prospective cohort Multisite |

Total parents: n=41 (cancer=14) Solid tumor: 20% Brain tumor: 10% Heme malig: 5% Non-malig:66% Female: 54% Non-white: 20% |

Inclusion: • Age 0–21 yr • Potentially life-limiting illness • Washington state resident Insurance from participating health plan |

Team: MD, APN, SW, community providers, case managers; Home health/hospice RN Where: Home When: if death within 24 mos not a surprise Intervention: Communication and decision-making assisted with insurance and integration of curative and comfort care |

Pre-PPC cohort |

Child QOL improved over baseline in most domains Significant positive changes in 14/30 family satisfaction items |

|

Jacob et al. 2018 India Describe demographics and EOL treatments |

Retrospective record review Single site |

Total children: n=44 Female: 39% Hemae malig: 66% Solid tumor:34% |

Inclusion: • Age <18 yr • Died during curative treatment |

Specifics of PPC intervention not described | PC subgroup analysis: Children who did not receive PPC | About half (referred to PC Main reason for referral was pain 45% of children with heme malig referred to PPC compared to 80% with solid tumor |

|

Kassam et al. 2015 Canada Determine whether PPC associated with improved EOL communication |

Retrospective record review; cross-sectional survey Both single site |

Parents of children with cancer: n=75 Child diagnosis: Heme malig:25% CNS tumor: 35% Solid tumor: 40% |

Inclusion: • Parents of children who died of cancer Exclusion: • Died <4 weeks of diagnosis |

Specifics of PPC intervention not described | Cohort that did not receive PPC | Parents with PPC involved more likely to receive all communication elements Children with heme malig less likely to receive PPC |

|

Kaye et al. 2017 U.S. Investigate characteristics and EOL experiences of children with cancer whjo received PPC |

Retrospective record review; Single site |

Children with cancer: n=321 Female: 42% Heme malig 24% Brain tumor: 43% Solid tumor:33% Caucasian: 68% Black/African American: 19% Hispanic/Latino: 18% |

Inclusion: • Cancer diagnosis • Received PPC at death |

Specifics of PPC intervention not described | Children who received late PPC (<30 days before death) | Median (range) time from PC consult to death was 79 (17319] days 74% of children had (early) PPC >30 days before death Those with early PPC less likely to die in ICU |

|

Lafond et al. 2015 U.S. Evaluate feasibility, acceptability of early PPC for children receiving HSCT; Assess child- reported comfort and determine concordance with parent report |

Prospective cohort Single site |

Total: n=12 (cancer n=7) Total caregivers: n=12 (cancer n=7) Female:50% Heme malig:25% Solid tumor:33% Non-malig:42% |

Inclusion: English-speaking patients admitted for HSCT and their parents |

Team: MD.APN Where: Inpatient When: at HSCT Intervention: included supportive care counseling and integrative therapies. |

Child outcomes pre-PPC |

90% Parents very comfortable with receiving PPC; 100% rated PPC as helpful/very helpful in managing symptoms and stresses Clinicians: PPC helpful in managing symptoms, other stressors (score ≥4/5 for all disciplines except RN); very likely to recommend PPC to patients and families (score ≥4/5 for all disciplines) Trend towards improvement in child-reported comfort |

|

Levine et al. 2016 U.S. Describe growth trajectory of a PPC program in a cancer center |

Retrospective record review Single site |

Children with cancer: n=615 Female: 43% Heme malig: n CNS tumor: 38% Solid tumor:32% Caucasian: 65% Black: 24) |

Inclusion: • Seen by PPC team at least once Mar, 2007- Dec, 2014 |

Team: MD’s. NP’s. bereavement coordinator Where: Inpatient. outpatient. home Intervention: ACP. symptom control. care coordination. emotional. spiritual. bereavement support |

Outcomes over time compared | PPC referrals increased over time Goals of care at initial visit shifted from comfort to cure Trends: earlier consultation, near-universal involvement of PPC at EOL |

|

Osenga et al. 2016 U.S. Compare EOL circumstances in an inpatient hospital setting, with or without PPC involvement |

Retrospective record review Single site |

Total children: n=114 (cancwe n=9) Female: 46% Caucasian: 59% Black/African American: 14% Asian: 7% American Indian: 3% |

Inclusion: • Age 0–18 yr • Died as inpatient at site • Treated 24 hours prior to death Exclusion: • Died in ED |

Team: MD, APN, RN, SW, CLS, chaplain, music therapist Where: Inpatient, outpatient, community When: PPC c at any point during final admission |

Cohort that did not receive PPC | Those with PPC higher rate of pain assessments, fewer diagnostic/monitoring procedures in the last 48 hours of life, greater odds of having a resuscitation status order in place at death |

|

Plymire et al. 2018 U.S. Analyze characteristics associated with EOL care, comparing pre- PPC with post-PPC |

Retrospective record review Single site |

Total children: n=167 (cancer n=41) Female: 46% Caucasian: 55% Black/African-American: 18% Asian: 4% |

Inclusion: • Age 0–21 yr • Previously inpatient at hospital |

Team: MD, APN, RN, SW, child life specialist, chaplain Where: Inpatient Intervention: Assistance with establishing goals of care, symptom management, EOL care |

Pre-PPC cohort |

After PPC, resuscitation status order rate increased; No change in the interval between order placement and death or change in the rate of ICU deaths |

|

Postier et al. 2014 U.S. Explore health care service utilization prior to home-based PPC/hospice enrollment compared to post-enrollment |

Retrospective record review Single site |

Total children: n=425 (cancer: n=200) Female: 45% Caucasian: 55% Black: 8% Asian: 7% Native American: 2% Hispanic: 6% |

Inclusion: • Age 1–21 yr • Cared for by PPC/hospice for ≥ 1 day Exclusion: • Infants <1 yr |

Team: MD, RN, SW, CLS, chaplains, music/massage therapists, volunteers Where: Home Intervention: Palliative/hospice home service with 24/7 access and care coordination |

Outcomes pre-PPC eprogram |

Enrollment in home-based PPC/hospice associated with increase in hospital/ER admissions for children with cancer and with longer exposure to PPC/hospice. |

|

Rossfeld et al. 2019 U.S. Estimate impact of PPC by analyzing ICU course across hospitalization |

Retrospective record review Single site |

Total children: n=777 (cancer: n=153) Female: 45% Caucasian:75% Black:9% Hispanic:15% |

Inclusion: • Age 0–21 yr • ICU >1 night • Dagnosis indicating PPC referral per expert criteria |

Team: MD, NP, SW, chaplain Where: Inpatient Intervention: Specifics of intervention not described |

Cohort hat did not receive PPC | For children with cancer, odds of being in the ICU on a given day reduced by 79% after PPC consultation PPC associated with decreased odds of being in the ICU |

|

Snaman et al. 2017 U.S. Characterize experience of AYA with cancer; Investigate differences between those with PPC and those without |

Retrospective record review; Single site | Total children: n=329 Female: 36% Heme malig: 29% Brain tumor:29% Solid tumor:37% |

Inclusion: • Age ≥15 yr • Cancer diagnosis |

Specifics of intervention not described | Cohort that did not receive PPC | AYA with PPC less likely to die in ICU, be on a ventilator, undergo invasive medical procedures/treatments Time between order and death was longer with PPC |

|

Stutz et al. 2018 U.S. Describe patterns of PPC cand associations with EOL |

Retrospective record review; single site | Total children: n=233 (cancer. n=31 ) Female:41% Caucasian:37% Hispanic: 33% |

Inclusion: • Died at age <18 yr |

Team: MD,APN, SW, chaplains, psychologists Where: Inpatient |

Cohort that did not receive PPC | PPC for children in the ward and ICU more likely than for children with cancer PPC associated with increased completion of POLST |

|

Thrane et al. 2017 United States Examine outcomes after PPC referral and associations between child characteristics and survival; whether pain decreases after PPC |

Retrospective record review Ssingle site |

Total children: n=256 (cancer: n=107) Female: 47% Caucasian:88% Black10% Hispanic: 1% |

Inclusion: • Age 2–16 yr at PPC referral |

No specifics of intervention described | Pre-PPC (subgroup |

Time from PPC referral to death differed by diagnosis Pain scores lower post-referral |

|

Ullrich et al. 2016 U.S. Evaluate whether PPC associated with differences in EOL patterns for children who underwent HSC |

Retrospective record review Sngle site |

Total: n=147 (cancer. n=118) Female: 48% Heme malig:65% Solid/brain tumor:15% Non-malig: 20% Caucasian: 74% Non-Hispanic: 87% |

Inclusion: • All children who underwent HSCT and did not survive |

Intervention: Assisted with goals of care, decision-making/ACP symptom management, psychosocial and spiritual support | Cohort that did not receive PPC | PPC not associated with duration of survival PPC group: prognosis and resuscitation status discussions occurred more commonly and earlier; less likely to die in ICU, or be intubated in the 24 hours prior to death PPC not associated with death at home or hospice |

|

Vern-Gross et al. 2015 U.S. Evaluate outcomes in children with solid tumors; Compare patterns of EOL after PPC |

Retrospective record review Single site |

Total: n=191 Female: 44% Caucasian:62% Black:29% |

Inclusion: • Age <21 yr • Solid tumor d • Enrolled in PPC through death |

Included symptoms/ ACP, and EOL discussions | Cohort that did not receive PPC | PCC associated with increased number of EOL discussions, which also occurred earlier, and hospice Time from first EOL discussion to hospice; resuscitation status order to death longer in PPC |

|

Widger et al. 2018 Canada Determin ewhich children access specialized PPC and the impact of PPC EOL care intensity |

Retrospective review Multisite |

Total: n=572 Female: 43% Heme malig:32% CNS tumor:32% Solid tumor:36% |

Inclusion: • Age <15 yr • Died age <18 yr Exclusion: • Died of external cause; or ≤30 days after diagnosis |

Specifics of PPC intervention not described | Cohort that did not receive specialized PPC | Children with lower household incomes or in rural areas less likely to receive PPC PPC >30 days before death associated with decrease in ICU admission, mechanical ventilation, in-hospital death PPC associated with lower intensity EOL care |

|

Wolff et al. 2010 Germany Measure satisfaction and preference for LOD after a PPC program |

Retrospective record review Single site |

Total: n=51 (cancer n=29) Total caregivers n=35 Leukemia:12% Brain tumor: 31% Solid tumor:14% Immunologic and/or heme: 4% Other: 39% |

Inclusion: • Caregiver of a child who: - Died of any condition - Received treatment at site |

Team: MD,RN Where: Home, hospital Intervention: educating caregivers about dying, how to talk with child about dying; addressing parents’ emotional needs. |

Cohort that did not receive PPC | After PPC program, more children died at home Satisfaction with medical services was high, independent of LOD |

|

Vollenbroich et al. 2012 Germany Evaluate effectiveness of PPC home care team (PPHCT) |

Retrospective survey Single site |

Total: n=45 (cancer n=16) Parent dyads: n=38 (cancer n=16) |

Inclusion: • Families with a child ≥3 mos prior to study • Received care through PPCHT |

Team: MD, RN, SW chaplain Where: Home Intervention: Coordination of care, provision of palliative treatment, 24/7 medical on-call service |

Cohort pre- PPC | PPHCT associated with: Improvements in child symptoms, QOL; communication barrier reduction |

|

Trowbridge et al. 2018

U.S. Characterize the modes of pediatric inpatient death |

Retrospective record review; Sngle site: |

Total: n=579 (cancer:n=91) Female: 50% Caucasian: 39% Black/African-American:24% Other:34% Hispanic: 10% |

Inclusion: • All inpatient children who died July, 2011 - June, 2014 | Specifics of PPC intervention not described | Cohort that did not receive PPC | The majority who died in non-ICU ward settings had PPC, in contrast to those who died in ICU Children who had PPC were more likely to have a non-escalation death, less likely to experience resuscitative efforts at death |

Abbreviations: PC, palliative care; PPC, pediatric palliative care, HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplant; EOL, end of life, LOD, location of death, LOS, length of stay; QOL,quality of life; ADLs, activities of daily living; AYA, adolescent and young adult; heme malig, hematologic malignancy; heme, hematologic (non- malignany) condition

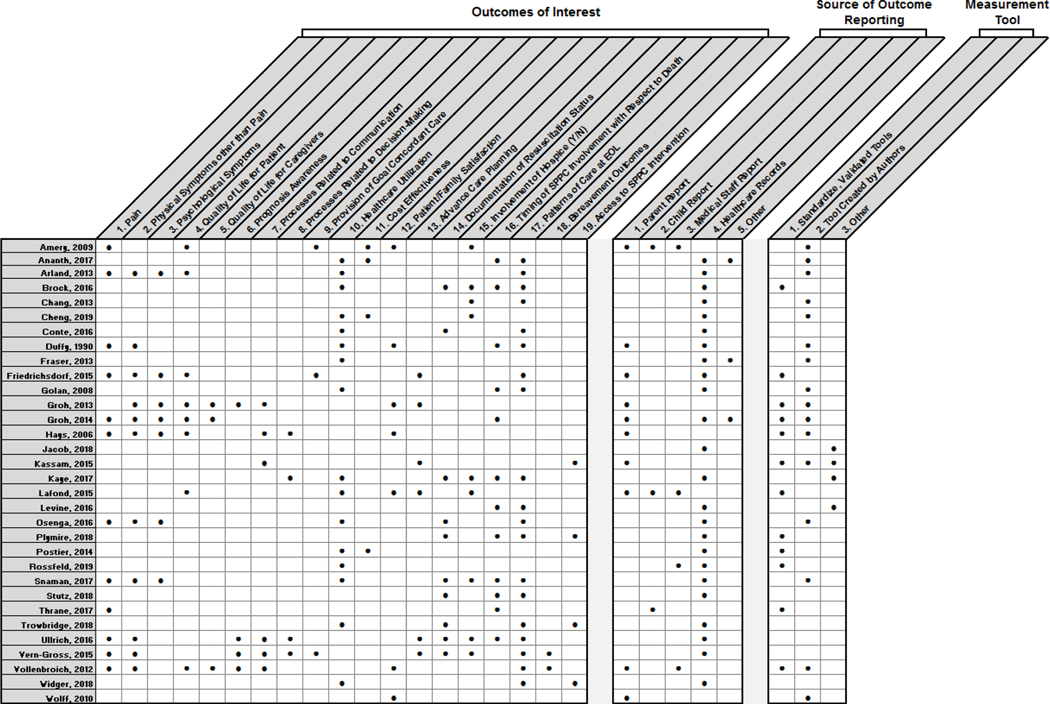

Fig. 2.

National Quality Forum indicator domains identified within included articles.

Fig. 3.

Outcomes, reporting sources, and measurement tools identified within included articles.

Of the 32 final articles, 27 (84.3%) were retrospective, 4 (12.5%) prospective longitudinal, and 3 (9.4%) included cross-sectional methods; several articles applied combined methods, resulting in aggregated percentages exceeding 100%. No articles described randomized control trial methods. Twenty-six studies (81.3%) were conducted at a single site and 6 (18.8%) across multiple sites. Within the 32 studies, 15,635 unique children with cancer and 342 parents were represented. Nineteen articles (59.4%) described race and ethnicity of participants, with a range of Black and Hispanic enrollment comprising 0–29% and 1–33%, respectively.

With respect to a comparator arm, 20 studies (62.5%) compared children who received SPPC to a similar cohort that either received no or delayed SPPC; 10 studies (31.3%) used a pre/post design to compare outcomes prior to and after SPPC intervention within the same population; 1 study (3.1%) compared the experiences of patients at in the early phases of a SPPC program with patients in more mature phases of program development and expansion; and 1 study (3.1%) used both a pre-/post- SPPC program maturation and non-SPPC to SPPC comparison.

Intervention content and delivery

No studies described a model of SPPC based on an individual expert. Nineteen (59.4%) studies described team-based SPPC consultation, although the disciplines and roles of team members were defined less frequently: 15 papers mentioned involvement of a physician, 9 mentioned an advance practice provider, 10 mentioned a nurse, 12 mentioned a social worker, 10 mentioned a chaplain, 5 mentioned a child life specialist, 1 mentioned a psychologist, and 0 mentioned a grief or bereavement counselor. SPPC involvement occurred at the usual/standard timing in most studies; in 6 papers, SPPC integration occurred following specific “triggers” (i.e., pre-defined criteria that automatically result in SPPC consultation), such as disease progression or poor prognosis. The majority of studies did not describe formal mechanisms of collaboration between oncology and SPPC clinicians.

Targeted outcomes, measurement tools, and reporting sources

A wide range of outcomes were measured across included studies. Most papers focused on metrics related to illness progression and end-of-life experiences. Figures 2 and 3 present the spectrum of outcomes and NQF indictor domains captures within the 32 included papers. Fifteen papers (46.9%) used measurement tools created by the authors, and 6 papers (18.8%) incorporated validated measurement tools. Twenty-four papers (75.0%) relied on extraction of data from medical records; 10 (31.3%) relied on family caregiver report, 3 (9.4%) on child report, 4 (12.5%) on medical staff report, and 3 (9.4%) pulled information from regional or hospital databases.

Intervention efficacy, feasibility, and acceptability

All studies evaluated outcomes associated with exposure to some model of SPPC as compared to no or delayed SPPC. Three papers (9.4%) described feasibility of a SPPC intervention, and four papers (12.5%) described acceptability grounded in patient or caregiver satisfaction metrics.

Quality appraisal

The majority of studies did not meet criteria for appraisal due to retrospective study design. Only 4 articles with prospective cohort design were eligible for appraisal (Table 3). Overall, their quality was high.

Table 3.

Quality Appraisal via the Newcastle Ottawa Scale

| Cohort Studies | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author Date | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | |||||

| Representativeness of exposed cohort | Selection of non-exposed cohort | Ascertainment of exposure | Outcome of interest not present at start of study | Comparability of cohorts on basis of design or analysis | Assessment of outcome | Adequacy of length of follow-up | Adequacy of follow-up of cohorts | |

| Groh 2013 | (a)*representative of the community | (a)*drawn from same community (i.e., pre/post) | (a)*secure record | (b) no | Information not provided | *record linkage & self report | (a)*yes | (a)*complete follow-up |

| Groh 2014 | (a)*representative of the community | (a)*drawn from same community (i.e., pre/post) | (a)*secure record | (b) no | Information not provided | *record linkage & self report | (a)*yes | (a)*complete follow-up |

| Hays 2006 | (a)*representative of the community | (a)*drawn from same community (i.e., pre/post) | (a)*secure record | (b) no | Information not provided | *record linkage & self report | (a)*yes | (a)*complete follow-up |

| Lafond 2015 | (a)*representative of the community | Information not provided | (a)*secure record | (a)*yes | Information not provided | *record linkage & self report | (a)*yes | (a)*complete follow-up |

Findings

Programmatic maturation: Longitudinal studies showed an increase in the integration of SPPC over time described as increased referral patterns and consultation frequency with a trend toward earlier consultation and regular long-term follow up.41–43 One study reported a shift over a sevenyear span from less than half of patients receiving palliative care referrals to near-universal involvement of SPPC at end of life.43

Diagnosis association:

Children diagnosed with solid tumors were more likely to receive SPPC than those with hematologic malignancies.44,45 Those with brain tumors and solid tumors enrolled in hospice and died at home more frequently than those with leukemia/lymphoma.42 Forty-five percent of children with hematologic malignancies received SPPC referral, compared to 80% of children with solid tumors (p=0.052).46

Symptom burden and management:

Symptom burden for children receiving SPPC included pain,14,41,46–48 fatigue and energy loss,14 nausea and vomiting,47 constipation,14 and anxiety.47 Caregivers also described symptom burden to include seizures, dyspnea, and impaired speech. Overall, integration of SPPC was associated with significant improvements in children’s symptoms.26,49 Pain management was a primary rationale for referral to SPPC,46 with post-referral pain scores significantly lower when compared to pre-referral.48 Increased use of pain medications for physical pain symptoms were also noted in children receiving SPPC.41 For children at end of life, those receiving SPPC had higher rates of pain assessment, better documentation around specific actions to manage pain, and greater odds of receiving integrative medicine services.50

Child quality of life and well-being:

SPPC integration was associated with improvement in the child’s quality of life.26,49 Parent evaluations of the child’s quality of life improved over baseline in three primary domains: physical functioning, school-related domains, and emotional functioning.51 Children with cancer receiving SPPC were noted to have similar levels of fear versus peace/calm at the end of life, but those who received SPPC were more likely to report experiencing fun or a meaningful event in last month of life.14 Additionally, SPPC was associated with increased documentation of psychological diagnoses or mental health needs (p=0.02).52

Hospitalization patterns:

Findings appeared to vary between cohorts. In one article, referral to SPPCS was associated with a significant reduction in the rate of planned hospital admissions.53 Children with brain tumors who received SPPC also were hospitalized less often than those who did not receive SPPC.54 However, some SPPC recipients had an increase in admissions post-referral compared to pre-referral,55 and the mean number of total hospital days and ED visits per year did not appear to change significantly with SPPC involvement.56

Length of stay:

At baseline, SPPC consultations were associated with patients predisposed to having longer lengths of stay.55,57 One study showed no significant difference in length of stay before and after SPPC involvement, but observed longer admissions among those who received SPPC/hospice compared to usual care.55 Establishing care with SPPC was associated with shorter length of stay overall in another study (23.9 versus 32.6 days).44 While SPPC was initially associated with lower hospital and emergency room lengths of stay, significant increases in hospital length of stay and emergency room admissions were seen in children with cancer diagnoses who had longer exposures to SPPC/hospice services.58

Cancer-directed therapy:

Among 38 patients who received cancer treatment in last 30 days of life, 23 (61%) were referred to SPPC.46 A study conducted in a high-income setting reported that the majority of SPPC patients received experimental therapy (79.4%) with 35.5% receiving cancer-directed therapy in last month of life.59 Similar findings were seen in a low-income setting, with SPPC involvement associated with higher rates of chemotherapy administration and completion.41

Location of death:

In several studies, SPPC was not associated with a significant decrease in the number of patients dying in the hospital as compared to home.42,54,60 However, in other studies, children referred to SPPC had a decreased risk of dying in-hospital,43,56,61–63 with one study reporting a shift from 18% to 69% of children dying at home rather than the hospital setting after initiation of a SPPC program.63 Children who received SPPC also had fewer days in the hospital at the end of life55,62 and spent a greater proportion of the terminal phase at home.62 Further, the SPPC cohort was more likely to have a documented preference of a home death,14 and most parents of children who died at home with SPPC services described location of death as “a good place” and the death as “peaceful.”26

Pediatric patients with late SPPC involvement (occurring < 30 days before end of life) had higher odds of dying in the intensive care unit setting over the home/hospice setting compared to those with earlier SPPC involvement.59 Accessing SPPC > 30 days before death was associated with five-fold decreased odds of admission to the intensive care unit with similar decreased odds of mechanical ventilation and in-hospital death.64 Adolescents and young adults with SPPC were less likely than those without SPPC involvement to die in the intensive care unit or be on a ventilator.7 Odds of being in the intensive care unit on a given day were reduced by 79% after SPPC consultation for children with cancer.65 For children who underwent stem cell transplant and did not survive, those receiving SPPC were less to die in the intensive care unit and less likely to be intubated 24 hours prior to death, although they were not more likely to die in the hospital compared with home.60

Intensive medical procedures:

SPPC was associated with lower intensity care at the end of life when compared to those who did not receive SPPC.64 Specifically, children receiving SPPC underwent fewer intensive treatments,7,55 fewer diagnostic/monitoring procedures,50 and were less likely to receive mechanical ventilation within 48 hours of death52 compared to those not receiving SPPC.

Cost:

Cost efficacy for SPPC care was noted in limited-resource setting with less than $100 required for SPPC packaged services offered.41 Palliative care utilization predicted a decreased cost of $46,632 over the course of the hospital stay (P < .0001) and $1163 per day (P < .0001) in a higher resourced setting.44 One study reported children receiving SPPC notably had lower total hospital charges,58 whereas mean hospital costs remained unchanged following SPPC involvement in another study.56

Advance care planning/resuscitation status:

SPPC significantly increased the number of end-of-life discussions, and these took place earlier when compared to a historical cohort.47 For example, prognosis and resuscitation status discussions occurred more commonly and earlier for children who received SPPC,60 and SPPC care was associated with an increased number of do-not-resuscitate orders in charts42,50,66 andcompletion of advance directive (i.e., POLST) forms.52,55,59 Children who received SPPC consultation were significantly less likely to experience a resuscitative event than those without a SPPC consultation (7% vs. 30.2%).57 Notably, SPPC involvement was not associated with a decreased duration of survival.60

Family satisfaction:

Positive changes in all 30 analyzed items measuring family satisfaction were seen for families receiving SPPC services, 14 of which were statistically significant within the domains of patient-provider communication, symptom management, and responsiveness of health plans.51 Satisfaction with the overall quality of SPPC was rated as excellent across several studies,26,63 and parents reported high satisfaction with palliative care programmatic involvement and home-based services and support.62 Ninety percent of parents indicated they were very families.67

Caregiver experience:

Caregiver satisfaction with their child’s care improved after involvement of SPPC across domains related to symptom management, psychosocial support, and communication.28 In another study, family caregivers endorsed significant improvement in quality of life after SPPC involvement, and caregiver burden, anxiety, and depression also decreased following palliative care involvement 49

Communication:

Parents with SPPC team involvement were more likely to receive communication related to anticipatory guidance and preparation for death and dying for the patient and family.45 In another study, most parents (91%) who received SPPC reported that they had the opportunity to talk about death with the palliative care team, and more than half (58%) had the opportunity to talk about imminent death with their own child.26 Importantly, family members reported that health care providers’ willingness to listen to parental questions and/or problems increased significantly with inclusion of SPPC.26 Communication among health care providers also improved with inclusion of SPPC.26

Discussion

This systematic review revealed that children with cancer who received SPPC largly demonstrated improved symptom burden and quality of life, increased opportunities to plan for care, decreased intensity of medical interventions, and greater likelihood of dying in the home. SPPC also did not appear to be associated with decreased duration of survival, importantly challenging historical clinician assumptions of and/or barriers to SPPC referral.68 Families generally reported satisfaction and improved communication in the context of SPPC involvement. Study outcomes may differ based on specialist palliative care composition and delivery, longitudinal nature of palliative care relationship, and intensity of palliative care intervention exposure; however, limited presentation of data in these categories precludes the ability to explore associations across studies.

This review highlights the opportunity for prospective intervention research to establish causal relationships between SPPC interventions and outcomes. Existing literature that describes and examines outcomes associated with SPPC remains predominantly retrospective, although several prospective cohort studies have been presented within recent years. Randomized control trials, commonly considered the gold standard in demonstrating conclusive value added, are conspicuously absent in this analysis. Although numerous challenges exist in designing and implementing randomized control trial methodology to study SPPC impact, this remains a critical frontier to explore to advance the field. However, nuanced aspects of SPPC services, including ethos, values, relationships, and meaning-making, may not be measurable in the context of a randomized control trials, and complementary research approaches are needed to explore and describe the complex benefits offered by SPPC. For example, SPPC intervention impact may be measured through randomized control trial (i.e., does this work?), while integration fidelity may be better explored and understood through research with an explanatory focus (e.g., how does this work? why? in what circumstances? for whom?).

Additionally, this review highlights the importance of promoting research related to the benefits and challenges inherent to SPPC integration on an international scale. By some estimates, ninety-eight percent of children who need SPPC live outside of the United States, largely in low- and middle-income countries where access to SPPC clinicians and resources are sparse.69 Greater attention towards identifying feasible and culturally-sensitive methods for palliative care implementation globally is warranted, building upon existing precedent for successful implementation models in resource-poor settings.70,71

This review also underscores the need for more intentional and comprehensive treatment of race, ethinicity, and cultural aspects of care within the research construct. Notably, only one-third of children included in the studies were Black or Hispanic, raising concerns about inclusivity and diversity in the pediatric populations receiving palliative care and/or participating in palliative care research. Most studies did not report race or ethnicity in any capacity, and this deficit warrants consideration in conjunction with advocacy for demographic reporting as a standard in academic publications to better understand health equity outcomes across studies. Presently, little is known about how race, ethnicity, and culture influence referral to and/or acceptance of SPPC consultation within pediatric cancer care. Cultural aspects of care also comprised the least reported NQF domain, offering opportunities for investigators to broaden knowledge in this area within future participatory palliative care research.

Additionally, opportunities exist for the design and implementation of research involving validated patient- and family-centered outcome measures. Few studies included validated instruments in the assessment of outcomes, including impact; rather, most studies relied on measurement tools created by the research team, highlighting the need for improved availability of validated instruments for patient and proxy (e.g., caregiver or clinician) reported outcomes to strengthen the science within the field. While pediatric palliative care emphasizes the child’s voice in evaluating subjective outcomes, reporting was highly dependent on provider perspectives or medical record data with few studies utilizing parent-reported outcomes and even fewer including the child’s perspective. We advocate for incorporation of validated patient- and family-centered tools whenever possible into the framework of future SPPC-related studies.

Outcomes of interest were notably diverse, ranging from cost effectivness to location of death to communication satisfaction. The location of end-of-life care was a highly reported outcome which seemed to equate end-of-life care occurring at home with a sense of “palliative success,” although few studies paired a summary of end-of-life care location with actual child or family preference for end of life care location. We advocate for consideration of indicators that capture provision of goal-concordant care, as well as indicators that describe opportunities to plan and prepare for end of life, as meaningful outcomes to query in relation to SPPC impact in future studies.72

Feasibility of SPPC integration was reported as high across studies, with the important caveat that holistic evaluation of intervention implementation was limited by the lack of details regarding specific SPPC programs offered within most articles. As such, implementation fidelity was difficult to decipher when no study reported the extent to which the level of SPPC integration was or was not delivered as intended. The lack of specificity with respect to intervention fidelity challenged our ability to draw conclusions about outcomes across studies. Clearer depictions of SPPC intervention content and implementation, as well as use of standardized metrics of quality, would add depth to the interpretation of the outcomes and promote generalizability in future research.

This review was conducted with attention to rigor; strengths include advanced search strategies utilizing multiple databases designed and implemented by an expert medical librarian, concurrent two-party review with subsequent adjudication, and alignment of SPPC impact with NQF domains. However, certain limitations warrant discussion. Exclusion of non-English language papers in the search strategy creates a selection bias that may influence findings. While comprehensive, advanced search strategies are not perfect mechanisms for gathering every publication; for example, requirement of the terms “oncology” or “cancer” within the title and/or abstract allowed for appropriate upfront culling of articles, however it is possible that some relevant papers may have been missed. Likewise, rigorous dual review with third-party adjudication and auditing minimizes but does not wholly eliminate chance of human error within the process. More than half of studies were conducted in the U.S., and the authors acknowledge that the preponderance of U.S.-centric articles may limit the generalizability of findings globally. Study design limitations within included papers, such as single site approach, retrospective methodology, and lack of consistent diversity within studied cohorts, may influence the generalizability and reliability of findings. Finally, data heterogeneity and type precluded meta-analyses, which is a limitation of this paper.

Conclusion

Evidence indicates that SPPC may be associated with improved illness and end-of-life experiences for children with cancer and their families. Future research to improve care for children with advancing cancer and their families may benefit from a comparative effectiveness approach with clear description of palliative intervention content and delivery, use of validated metrics, and report of feasibility and acceptability from the perspectives of patients, families, and clinicians. Multi-site studies with the ability to execute randomize control trial design and recruit diverse participants may also strengthen the science by enhancing generalizability, establishing causal effect, and promoting inclusivity, cultural awareness, and sensitivity, respectively. Additionally, nuanced aspects of SPPC may be better identified and understood through complementary, exploratory research approaches. As the field of pediatric palliative care continues to expand and mature, meaningful opportunities exist to advance research agendas and shape how SPPC interventions for children with cancer are conceptualized and investigated.

Supplementary Material

Key Message:

Comprehensive review of existing literature suggests that integration of specialty palliative care in pediatric oncology benefits patients and families. As the field advances, development of multi-site and/or randomized control studies using comparative effectiveness methods and validated patient- and family-centered metrics may further strengthen the science.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Statement

No authors have relevant conflicts of interest to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, et al. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin 2014; 64: 83–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ward ZJ, Yeh JM, Bhakta N, et al. Estimating the total incidence of global childhood cancer: a simulation-based analysis. Lancet Oncol 2019; 20: 483–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health. Fighting childhood cancer with data. The Lancet Child and Adolescent Health 2019; 3: 585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wolfe J, Orellana L, Ullrich C, et al. Symptoms and Distress in Children With Advanced Cancer: Prospective Patient-Reported Outcomes From the PediQUEST Study. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 1928–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ullrich CK, Dussel V, Hilden JM, et al. End-of-life experience of children undergoing stem cell transplantation for malignancy: parent and provider perspectives and patterns of care. Blood 2010; 115: 3879–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bona K, Dussel V, Orellana L, et al. Economic impact of advanced pediatric cancer on families. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014; 47: 594–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snaman JM, Kaye EC, Lu JJ, et al. Palliative Care Involvement Is Associated with Less Intensive End-of-Life Care in Adolescent and Young Adult Oncology Patients. J Palliat Med 2017; jpm.2016.0451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kamper R, Van Cleve L, Savedra M. Children with advanced cancer: responses to a spiritual quality of life interview. J Spec Pediatr Nurs 2010; 15: 301–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaye EC, Snaman JM, Baker JN. Pediatric Palliative Oncology: Bridging Silos of Care Through an Embedded Model. J Clin Oncol 2017; JCO.2017.73.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Al Lamki Z.Improving Cancer Care for Children in the Developing World: Challenges and Strategies. Curr Pediatr Rev 2017; 13: 13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaye EC, Friebert S, Baker JN. Early Integration of Palliative Care for Children with High-Risk Cancer and Their Families. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2016; 63: 593–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feudtner C, Friebert S, Jewell J. Pediatric palliative care and hospice care commitments, guidelines, and recommendations. AAP Section on Hospice and Palliative Medicine and Committee on Hospital Care. Pediatrics 2013; 132: 966–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolfe J, Friebert S, Hilden J. Caring for children with advanced cancer integrating palliative care. Pediatr Clin North Am 2002; 49: 1043–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedrichsdorf SJ, Postier A, Dreyfus J, et al. Improved Quality of Life at End of Life Related to Home-Based Palliative Care in Children with Cancer. J Palliat Med 2015; 18: 143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaye EC, Rubenstein J, Levine D, et al. Pediatric palliative care in the community. CA Cancer J Clin 2015; 65: 315–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Waldman E, Wolfe J. Palliative care for children with cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2013; 10: 100–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Snaman JM, Kaye EC, Levine DR, et al. Pediatric Palliative Oncology: A New Training Model for an Emerging Field. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 288–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ferris FD, Bruera E, Cherny N, et al. Palliative cancer care a decade later: accomplishments, the need, next steps -- from the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27: 3052–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dhillon N, Kopetz S, Pei BL, et al. Clinical findings of a palliative care consultation team at a comprehensive cancer center. J Palliat Med 2008; 11: 191–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parikh RB, Kirch RA, Smith TJ, et al. Early specialty palliative care--translating data in oncology into practice. N Engl J Med 2013; 369: 2347–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Berendt J, Stiel S, Simon ST, et al. Integrating Palliative Care Into Comprehensive Cancer Centers: Consensus-Based Development of Best Practice Recommendations. Oncologist 2016; 21: 1241–1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith TJ, Temin S, Alesi ER, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology provisional clinical opinion: the integration of palliative care into standard oncology care. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30: 880–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrell BR, Temel JS, Temin S, et al. Integration of Palliative Care Into Standard Oncology Care: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 2016; 34: 1–17.26578609 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hui D, Bruera E. Models of integration of oncology and palliative care. Ann Palliat Med 2015; 4: 89–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidt P, Otto M, Hechler T, et al. Did increased availability of pediatric palliative care lead to improved palliative care outcomes in children with cancer? J Palliat Med 2013; 16: 1034–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vollenbroich R, Duroux A, Grasser M, et al. Effectiveness of a pediatric palliative home care team as experienced by parents and health care professionals. J Palliat Med 2012; 15: 294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Groh G, Vyhnalek B, Feddersen B, et al. Effectiveness of a specialized outpatient palliative care service as experienced by patients and caregivers. J Palliat Med 2013; 16: 848–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Groh G, Borasio GD, Nickolay C, et al. Specialized pediatric palliative home care: a prospective evaluation. J Palliat Med 2013; 16: 1588–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gans D, Kominski GF, Roby DH, et al. Better outcomes, lower costs: palliative care program reduces stress, costs of care for children with life-threatening conditions. Policy Brief UCLA Cent Health Policy Res 2012; 1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marcus KL, Santos G, Ciapponi A, et al. Impact of Specialized Pediatric Palliative Care: A Systematic Review. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 2020; 59: 339–364.e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Conte T, Mitton C, Trenaman LM, et al. Effect of pediatric palliative care programs on health care resource utilization and costs among children with life-threatening conditions: a systematic review of comparative studies. C Open 2015; 3: E68–E75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitchell S, Morris A, Bennett K, et al. Specialist paediatric palliative care services: What are the benefits? Arch Dis Child 2017; 102: 923–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng BT, Rost M, De Clercq E, et al. Palliative care initiation in pediatric oncology patients: A systematic review. Cancer Medicine 2019; 8: 3–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor J, Booth A, Beresford B, et al. Specialist paediatric palliative care for children and young people with cancer: A mixed-methods systematic review. Palliative Medicine 2020; 34: 731–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferrell B, Connor SR, Cordes A, et al. The National Agenda for Quality Palliative Care: The National Consensus Project and the National Quality Forum. J Pain Symptom Manage 2007; 33: 737–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Covidence systematic review software, www.covidence.org (accessed 10 August 2020).

- 37.World Health Organization Definition of Palliative Care, http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/ (2012, accessed 4 August 2016).

- 38.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ; 339. Epub ahead of print 2009. DOI: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wells G, Shea B, O’Connell D et al. The Newcastle- Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrando- mised studies in meta-analysis 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aslakson RA, Ast K, AAHPM Research Committee. Introduction to a New Special Series for the Journal of Pain and Symptom Management-Science in Action: Evidence and Opportunities for Palliative Care Across Diverse Populations and Care Settings. J Pain Symptom Manag 2019; 58: 134–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Amery JM, Rose CJ, Holmes J, et al. The beginnings of children’s palliative care in Africa: Evaluation of a children’s palliative care service in Africa. J Palliat Med 2009; 12: 1015–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brock KE, Steineck A, Twist CJ. Trends in End-of-Life Care in Pediatric Hematology, Oncology, and Stem Cell Transplant Patients. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2016; 63: 516–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Levine DR, Johnson L-M, Snyder A, et al. Integrating Palliative Care in Pediatric Oncology: Evidence for an Evolving Paradigm for Comprehensive Cancer Care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2016; 14: 741–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng BT, Wangmo T. Palliative care utilization in hospitalized children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer; 67. Epub ahead of print 1 January 2020. DOI: 10.1002/pbc.28013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kassam A, Skiadaresis J, Alexander S, et al. Differences in end-of-life communication for children with advanced cancer who were referred to a palliative care team. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2015; 62: 1409–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jacob J, Matharu JK, Palat G, et al. End-of-life treatments in pediatric patients at a government tertiary cancer center in India. J Palliat Med 2018; 21: 907–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vern-Gross TZ, Lam CG, Graff Z, et al. Patterns of End-of-Life Care in Children with Advanced Solid Tumor Malignancies Enrolled on a Palliative Care Service. J Pain Symptom Manage. Epub ahead of print 16 April 2015. DOI: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thrane SE, Maurer SH, Cohen SM, et al. Pediatric Palliative Care: A Five-Year Retrospective Chart Review Study. J Palliat Med 2017; 20: 1104–1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Groh G, Feddersen B, Führer M, et al. Specialized home palliative care for adults and children: Differences and similarities. J Palliat Med 2014; 17: 803–810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Osenga K, Postier A, Dreyfus J, et al. A Comparison of Circumstances at the End of Life in a Hospital Setting for Children With Palliative Care Involvement Versus Those Without. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016; 52: 673–680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hays RM, Valentine J, Haynes G, et al. The Seattle Pediatric Palliative Care Project: effects on family satisfaction and health-related quality of life. J Palliat Med 2006; 9: 716–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stutz M, Kao RL, Huard L, et al. Associations Between Pediatric Palliative Care Consultation and End-of-Life Preparation at an Academic Medical Center: A Retrospective EHR Analysis. Hosp Pediatr 2018; 8: 162–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fraser LK, Van Laar M, Miller M, et al. Does referral to specialist paediatric palliative care services reduce hospital admissions in oncology patients at the end of life. Br J Cancer 2013; 108: 1273–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arland LC, Hendricks-Ferguson VL, Pearson J, et al. Development of an in-home standardized end-of-life treatment program for pediatric patients dying of brain tumors. J Spec Pediatr Nurs 2013; 18: 144–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Conte T, Mitton C, Erdelyi S, et al. Pediatric palliative care program versus usual care and healthcare resource utilization in British Columbia: A matched-pairs cohort study. J Palliat Med 2016; 19: 1218–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ananth P, Melvin P, Berry JG, et al. Trends in Hospital Utilization and Costs among Pediatric Palliative Care Recipients. J Palliat Med 2017; 20: 946–953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Trowbridge A, Walter JK, McConathey E, et al. Modes of Death Within a Children’s Hospital. Pediatrics 2018; 142: e20174182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Postier A, Chrastek J, Nugent S, et al. Exposure to home-based pediatric palliative and hospice care and its impact on hospital and emergency care charges at a single institution. J Palliat Med 2014; 17: 183–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaye EC, Gushue CA, DeMarsh S. Illness and end-of-life experiences of children with cancer who receive palliative care. Pediatr Blood Cancer. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ullrich CK, Lehmann L, London WB, et al. End-of-Life Care Patterns Associated with Pediatric Palliative Care among Children Who Underwent Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2016; 22: 1049–1055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Chang E, MacLeod R, Drake R. Characteristics influencing location of death for children with life-limiting illness. Arch Dis Child 2013; 98: 419–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Duffy CM, Pollock P, Levy M, et al. Home-based palliative care for children--Part 2: The benefits of an established program. J Palliat Care 1990; 6: 8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wolff J, Robert R, Sommerer A, et al. Impact of a pediatric palliative care program. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2010; 54: 279–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Widger K, Sutradhar R, Rapoport A, et al. Predictors of specialized pediatric palliative care involvement and impact on patterns of end-of-life care in children with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2018; 36: 801–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rossfeld ZM, Miller R, Tumin D, et al. Implications of Pediatric Palliative Consultation for Intensive Care Unit Stay. J Palliat Med 2019; 22: 790–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Plymire CJ, Miller EG, Frizzola M. Retrospective Review of Limitations of Care for Inpatients at a Free-Standing, Tertiary Care Children’s Hospital. Children 2018; 5: 164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lafond DA, Kelly KP, Hinds PS, et al. Establishing Feasibility of Early Palliative Care Consultation in Pediatric Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs 2015; 32: 265–277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dalberg T, Jacob-Files E, Carney PA, et al. Pediatric oncology providers’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators to early integration of pediatric palliative care. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013; 60: 1875–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.H S MC B JM, et al. A scoping review of palliative care for children in low- and middle-income countries. BMC Palliat Care; 16. Epub ahead of print 2017. DOI: 10.1186/S12904-017-0242-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Garcia-Quintero X, Parra-Lara LG, Claros-Hulbert A, et al. Advancing pediatric palliative care in a low-middle income country: an implementation study, a challenging but not impossible task. BMC Palliat Care; 19. Epub ahead of print 1 December 2020. DOI: 10.1186/s12904-020-00674-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Doherty M, Thabet C. Development and implementation of a pediatric palliative care program in a developing country. Front Public Heal; 6. Epub ahead of print 16 April 2018. DOI: 10.3389/fpubh.2018.00106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Dussel V, Kreicbergs U, Hilden JM, et al. Looking beyond where children die: determinants and effects of planning a child’s location of death. J Pain Symptom Manage 2009; 37: 33–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.