Abstract

Background

Pseudomonas aeruginosa intestinal carriage rates are significantly higher in immunosuppressed individuals and hospitalized patients who therefore have increased risk of infections and antibiotic-associated diarrhea. To combat intestinal dysbiosis and decolonize P. aeruginosa from gastrointestinal tract, we investigated the anti-adherence and gut microbiota modulation properties of marine prebiotic fucoidans.

Methods

Proteomic analysis of culture supernatant was performed by LC–MS/MS. Using lectin-based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, hemagglutinin domain interaction and inhibition with biomolecules were studied. We investigated the role of nutritional grade fucoidans in a mouse model and used 16S ribosomal RNA sequencing to examine fecal microbiota composition.

Results

Analysis of culture supernatant proteins indicated the secretion of two-partner secretion (TPS) family proteins, including TpsA1/CdiA2 and TpsA2/CdiA1. Lectin like activity at the N-terminal of TpsA due to a conserved hemagglutinin domain (Pfam identifier [ID] PF05860) mediates binding to mucins that carry multiple fucosylated glycans. Fucose-rich sulfated polysaccharides (fucoidans) and sulfated dextrans were found to be potent inhibitors of the recombinant N-terminal hemagglutinin domain of TpsA (TpsA-NT-HAD) binding to mucins. In a mouse model, antibiotic-induced dysbiosis was essential for P. aeruginosa gastrointestinal colonization. After prophylactic oral fucoidans supplementation, a higher proportion (60%) of the mice were decolonized over time and resisted re-colonization, this was associated with remarkable expansion of Bacteroides (post-infection day-3 abundance, 29–50%) and consequential reductions in bloom of Enterobacteriaceae and Enterococcaceae populations. In the non-supplemented group, Parabacteroides mediated recovery from dysbiosis but failed to decolonize P. aeruginosa.

Conclusions

Supplementing diet with marine prebiotic fucoidans can mediate earlier recovery from dysbiosis and decolonization of P. aeruginosa from gut by inhibiting secreted virulence factor (TpsA/CdiA) interaction with mucins and promoting the growth of beneficial Bacteroides population. We suggest the prophylactic use of nutritional grade fucoidans to decolonize P. aeruginosa from gastrointestinal tract of at-risk individuals to prevent infection and transmission of colonizing P. aeruginosa.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12929-023-00902-w.

Keywords: Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Two-partner secretion system, Hemagglutinin, Gastrointestinal colonization, Microbiota, Dysbiosis, Prebiotics, Fucoidans

Introduction

Pseudomonas aeruginosa can be isolated from < 10% of fecal samples collected from healthy children and adults and P. aeruginosa intestinal carriage rates are significantly higher in immunosuppressed individuals after antibiotic treatment [1–3]. Patients colonized with P. aeruginosa on admission tend to develop infection due to their colonizing strain during their hospital stay [4–6]. P. aeruginosa can cause antibiotic-associated diarrhea among immunosuppressed or hospitalized patients and children [7–9]. Shanghai fever caused by P. aeruginosa in children is one of the most severe enteric diseases with complications [10]. Although prophylactic antibiotic regimens for selective decontamination of the digestive tract (SDD) improved outcomes of critical patients in settings with low prevalence of antibiotic resistance [11], appropriate regimens have not yet been determined for P. aeruginosa. To combat intestinal dysbiosis and decolonize multidrug-resistant (MDR) P. aeruginosa from gastrointestinal (GI) tract, use of antibiotics-independent methods like, fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT), probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics have gained increased interest in recent years [12–15]. Polysaccharides from marine seaweeds, including those sulfated (fucoidan, agaran, carrageenan, and ulvan) and non-sulfated (laminaran and alginate) exhibit prebiotic properties by modulating the composition of gut microbiota (GM) and consequently, prevent certain gastrointestinal infections [16–18]. Alginates tend to increase Bacteroides, Bifidobacterium, and Lactobacillus species while laminarans mainly stimulate Bacteroides sp. [19]. Sulfated polysaccharides including fucoidans influence the gut microbiota composition in several ways, and the influence may vary depending on the type of fucoidan, animal models, and treatment duration [20]. In healthy C57BL/6 mice, Laminaria japonica treatment significantly increased the abundance of Ruminococcaceae, while Ascophyllum nodosum treatment significantly increased the abundance of Lactobacillus [21]. Shibata et al. reported that by supplementing Cladosiphon fucoidan to Mongolian gerbils, H. pylori-induced gastritis was strongly suppressed and 30% of gerbils were cured of H. pylori infection, which may reduce the risk of associated gastric cancer [22].

Although gut microbiota acts as a barrier against intestinal pathogens, P. aeruginosa overcomes the resistance to colonization mediated by gut microbiota and innate immune system, by producing an impressive array of virulence factors [23–26]. P. aeruginosa lectins LecA and LecB and extracellular appendages, such as flagella and pili, play a major role in the attachment of bacteria to their host and have been implicated in adhesion [27, 28]. Furthermore, P. aeruginosa carries large protein systems that belong to two-partner secretion (TPS) family (also known as Type Vb secretion systems, T5bSS), a TPS system mainly consists of the secreted TpsA effector protein and its TpsB partner transporter. TpsA1 (CdiA2, 573 kDa) and TpsA2 (CdiA1, 361 kDa) promote bacterial competition through contact-dependent growth inhibition systems (CDI) and adhesion and biofilm formation, therefore TPS system effectors are designated as major virulence determinants that are beneficial to Gram-negative pathogens [29, 30]. The protein domains of a TpsA/CdiA include, conserved two-partner secretion (TPS) transport domain at the N-terminus, the filamentous hemagglutinin domain 1 (FHA-1), the receptor-binding domain (RBD), the Tyr/Pro-enriched (YP) domain, the second FHA domain (FHA-2), the pre-toxin (PD) domain, and the C-terminus toxin domain (CdiA-CT) [30]. High sequence diversity was found in CdiI immunity proteins that specifically neutralize cognate CdiA-CT toxins, CdiA1 [31]. Although, the predicted functions of CdiA-CT sequences were highly diverse, most CTs tend to target nucleic acids; MafB19-like deaminase domain (Pfam ID PF14437) and EndoU RNase domain (PF14436) were predominant [31]. In P. aeruginosa strain PAO1, CT domain in the CdiA1 (PA0041) was found to be tRNase, while in CdiA2 (PA2464) it was predicted to be an EndoU RNase. Recent evidence suggested that CdiA-CT tRNAse activity contributes to virulence against mammalian host [30].

Majority of TpsA protein structures solved were limited to N-terminal TPS domain, or CdiA-CT domains associated with toxin activities of CDI systems [32]. Although the role of N-terminal TPS domain in secretion of the TpsA proteins is well defined, its ability to function as a carbohydrate recognition domain (CRD) that could mediate adhesion was never investigated in detail in Gram-negative bacteria. Since adhesion precedes colonization and infection, use of anti-adhesion and anti-biofilm agents that interfere with the ability of the bacteria to adhere to surfaces, cells and tissues of the host can limit the infections [28]. P. aeruginosa strains from Shanghai fever represent a good source to discover novel adhesins, haemagglutinins and other virulence factors that could enhance the fitness of the P. aeruginosa isolates to cause infection. We observed that N-terminal domain of TpsA1 and TpsA2 (TpsA-NT-HAD, CdiA-NT-HAD), which can be secreted, mediates binding to mucins rich in fucosylated glycans. Fucose-rich sulfated polysaccharides (fucoidans) and sulfated dextrans were found to be potent inhibitors of the TpsA-NT-HAD. In a mouse model of gastrointestinal colonization, antibiotic induced dysbiosis was essential for P. aeruginosa colonization, a higher proportion of the mice were decolonized over time due to prophylactic oral fucoidan supplementation, which was associated with remarkable expansion of Bacteroides and simultaneous reductions in Enterobacteriaceae and Enterococcaceae populations.

Methods

Bacterial strains

The P. aeruginosa laboratory strains PA14 and PAO1 and Shanghai fever clinical isolates were collected and used as described previously by Chuang et al. [9, 10]. P. aeruginosa and Escherichia coli were routinely cultured in Luria–Bertani (LB) medium at 37 °C with shaking at 250 rpm or on LB agar plates. Strains used in this study are listed in Additional file 2: Table S1.

Proteomics analysis

Initially in this study, we aimed to identify novel lectins and adhesins that could enhance the virulence of Shanghai fever isolates. For proteome analysis, supernatants were collected from three P. aeruginosa strains (two virulent Shanghai fever isolates and reference strain PA01). Briefly, overnight cultures of P. aeruginosa grown in 100 mL LB Medium were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm and culture pellets were suspended in 5 mL RPMI and transferred to flasks containing 95 mL RPMI and cultured further for 24 h at 37 °C. After centrifugation to sediment planktonic cells, clear culture supernatants were filtered with 0.45 µm filters. Next, Amicon 3000 kDa ultracentrifuge tubes (Millipore, USA) were used to concentrate proteins in 50 mL supernatants to 100 uL and protein samples were submitted to liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) analysis and processed as described previously by Feng et al. [33]. We searched the proteomics data set with six specific terms lectin, hemagglutinin, agglutinin, adhesin, carbohydrate binding and glycoprotein binding. In addition, hypothetical protein sequences were submitted to BLAST search (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) to verify the identity to known protein and conserved domains. Proteome analysis of culture supernatants revealed 378–462 proteins per strain, including cytoplasmic, surface associated and secreted proteins including three proteins with conserved haemagglutinin (HA) domain belonging to the two-partner secretion (TPS) family (Additional file 3: Table S2). Multiple sequence alignment of the N-terminal region (1–360 amino acids) of representative TpsA proteins was performed using CLUSTAL omega (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/). Percent identify matrix was produced by online tool available at https://www.uniprot.org/align. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using online tool phylogeny.fr (http://phylogeny.lirmm.fr).

Protein expression and purification

Recombinant N-terminal protein fragments of TpsA/CdiA and LecB monomer were expressed in E. coli BL21 (DE3) (RBC Bioscience, Taipei, Taiwan) and purified according to the manufacturer’s instructions for Ni2 + affinity chromatography using Nickel-Chelating Resin (Ni Sepharose 6 Fast Flow, GE Healthcare, Sweden). Protein preparations were evaluated by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS–PAGE) and Coomassie blue staining or by Western blotting (see detailed description in the Additional file 1: Supplementary Methods; Additional file 4: Table S3).

Lectin based enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISA)

ELISAs were adapted and performed as previously described by Torode et al. and Wu et al. [34, 35]. Using ELISA, we examined TpsA-NT-HA domain interaction with and inhibition by different biomolecules coated on 96-well plates including, mucins, glycoproteins, neoglycoproteins, polysaccharides, dendrimers synthetic glycosides (monovalent and multivalent) and HBGAs. Fucoidans from different species (Ascophyllum nodosum, Fucus vesiculosus, Macrocystis pyrifera, Laminaria japonica, Undaria pinnatifida were from commercial sources (Carbosynth (UK), Sigma (USA), Marinova (Australia)) (Additional file 5: Table S4). Tris buffers were prepared as described earlier by Heimburg-Molinaro et al. [36]. Substrates in 100 μL tris saline buffer (TSB) including, porcine gastric mucin type III (PGM, 1–2 μg), fucoidans (100 μg), alginates (1–100 μg based on solubility) and histo-blood group antigens (HBGAs) (1–100 μg) were coated in a 96-well microtiter plate (Costar, USA) for 18 h at 4 °C. After blocking with TSB + 0.05% Tween-20 + 1% BSA for 1 h at room temperature (22 °C), wells were filled with serially diluted TpsA-NT-HA with or without inhibitors and incubated for 1 h. After washing, wells were incubated with a 1:5000 dilution of rabbit anti-his tag monoclonal antibody (Bioman, Taiwan) for 1 h and subsequently with 1:5000 dilution of horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Millipore, USA) for 1 h. The color was developed using 3, 3′, 5, 5′-Tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) substrate (NeA-Blue, Clinical Science Products, USA), the change in absorbance was determined at 650 nm or at 450 nm after stopping the reaction by sulfuric acid. Based on half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) concentrations, high affinity and low affinity ligands were identified and analyzed further. The IC50 values were estimated by using a free online program from AAT Bioquest (https://www.aatbio.com/tools/ic50-calculator). Fucosylated glycans on porcine gastric mucin and fucoidans were identified with monoclonal antibodies and plant lectins using ELISA (see detailed description in the Additional file 1; Additional file 6: Table S5 and Additional file 7: Table S6). In vitro cell adhesion and inhibition assays were performed using human cell lines (A549 and Caco-2 cells) [10].

Animal studies

A mouse model was used to confirm the potential prophylactic activity of fucoidans against virulent Shanghai fever strain P. aeruginosa S8 gut colonization [9, 10]. Five-week-old mice (five mice per group) weighing 20–25 g were used in the experiments. Mice were pretreated with clindamycin 0.6 mg intramuscularly daily for 5 days before bacterial challenge to clear the native microbiota and establish colonization. A total of 0.1 mL of 0.45% sterile saline with or without a bacterial inoculum of 1 × 108 colony forming units (CFUs)/mL was delivered to the mice through an orogastric tube daily for 3 days. Nutritional grade fucoidans 0.5% (w/v), from Fucus vesiculosus (FV) and Ascophyllum nodusum (AN) (Marinova, Australia), were supplemented in the drinking water of mice for 19 days, including 2 days before, 3 days during and 14 days after orally challenging P. aeruginosa S8. In the positive control group (Water), mice were given drinking water before and after orally challenging with P. aeruginosa S8. While, mice without fucoidans supplementation and no challenge with P. aeruginosa S8 served as negative control (NC). To monitor bacterial shedding, stool samples were collected daily from individual mice by anal stimulation and plated on Pseudomonas isolation agar (Becton, Dickinson and Company, USA). Following fucoidan supplementation and oral challenge with P. aeruginosa, mice were considered completely decolonized of P. aeruginosa from GI tract when no fecal counts were observed on Pseudomonas isolation agar plates. A mouse was considered partially decolonized of P. aeruginosa when the fecal counts over time were found to be lower than those that had been ingested. The mice were observed daily for 30 days after bacterial inoculation. The animal study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (CGU 108–172), Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan.

16S rRNA sequencing and analysis

To investigate the role of fucoidans in bacterial dysbiosis, changes in microbiota profile due to virulent P. aeruginosa S8 colonization of the gut in mice were identified after analyzing the 16S rRNA sequencing data. Stool samples were collected from mice at several time points during the experiment for 16S rRNA sequencing (see detailed description in the Additional file 1: Methods) [37].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by using SPSS software version 20.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Significant differences in adhesion due to incubation with fucoidan was assessed using Chi Square test. A Kaplan–Meier survival analysis (log-rank test) was used to compare decolonization over time between the fucoidan supplemented groups and control group. Significant reductions in fecal P. aeruginosa load (median values of CFUs) among the groups during the study period was determined using Wilcoxon signed-rank test. The paired t-test analysis was performed to compare microbiota composition between groups at different levels (phyla and genus). A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant [38–40].

Results

Two-partner secretion (TPS) family proteins

By proteome analysis, a conserved hemagglutinin domain (HA, Pfamidentifier [ID] PF05860) was found at the N-terminal between 31 and 168 amino acid residues in one protein assigned as putative hemagglutinin (PA0041) and two proteins annotated as hypothetical proteins (PA2462 and PA4625) in all P. aeruginosa strains (Additional file 3: Table S2). Further analysis revealed that the three proteins with conserved HA domain belong to the TPS family, which are widespread in Gram-negative bacteria and consist of a large secreted exoprotein (TpsA) and a transporter protein (TpsB) located in the bacterial outer membrane. P. aeruginosa strains that belong to “PAO1” and “PA14” groups harbor at least five ubiquitous TPS systems, designated in PAO1 as Tps1: PA2462–PA2463 (CdiA2); Tps2: PA0040–PA0041 (CdiA1); Tps3: PA4624–PA4625 (CdrA); Tps4: PA4540–PA4541 (LepA) and Tps5: PA0690–PA0692 (PdtA) [25]. Additionally, we observed a remarkable sequence similarity (> 99%) between TpsA1 and TpsA2 in the N-terminal region (1–360 amino acids); which includes conserved hemagglutinin domain and TPS domain (Table 1; Additional file 8: Fig. S1).

Table 1.

Protein sequence identity of N-terminal residues (1–360aa) of TpsA proteins in Pseudomonas aeruginosa

| % Identity | Tps1: PA2462 | Tps2: PA0041 | Tps3: PA4625 | Tps4: PA4541 | Tps5: PA0690 | Tps6: PA4082 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Tps1: PA2462 CdiA2 |

100.00 | 99.17 | 24.11 | 23.20 | 23.31 | 19.61 |

|

Tps2: PA0041 CdiA1 |

99.17 | 100.00 | 23.72 | 23.60 | 23.31 | 20.00 |

|

Tps3: PA4625 CdrA |

24.11 | 23.72 | 100.00 | 36.87 | 27.02 | 32.01 |

|

Tps4: PA4541 LepA |

23.20 | 23.60 | 36.87 | 100.00 | 29.73 | 56.23 |

|

Tps5: PA0690 PdtA |

23.31 | 23.31 | 27.02 | 29.73 | 100.00 | 27.48 |

| Tps6: PA4082CupB5 | 19.61 | 20.00 | 32.01 | 56.23 | 27.48 | 100.00 |

Percent identify matrix was produced by online tool available at https://www.uniprot.org/align. Amino acid sequence alignment of the TpsA1 and TpsA2 NT domains (1–360 aa) harbored in strains PAO1 (PA2462, PA0041) and PA14 (PA14_32790, PA14_00510) revealed that the sequence identity was > 99%

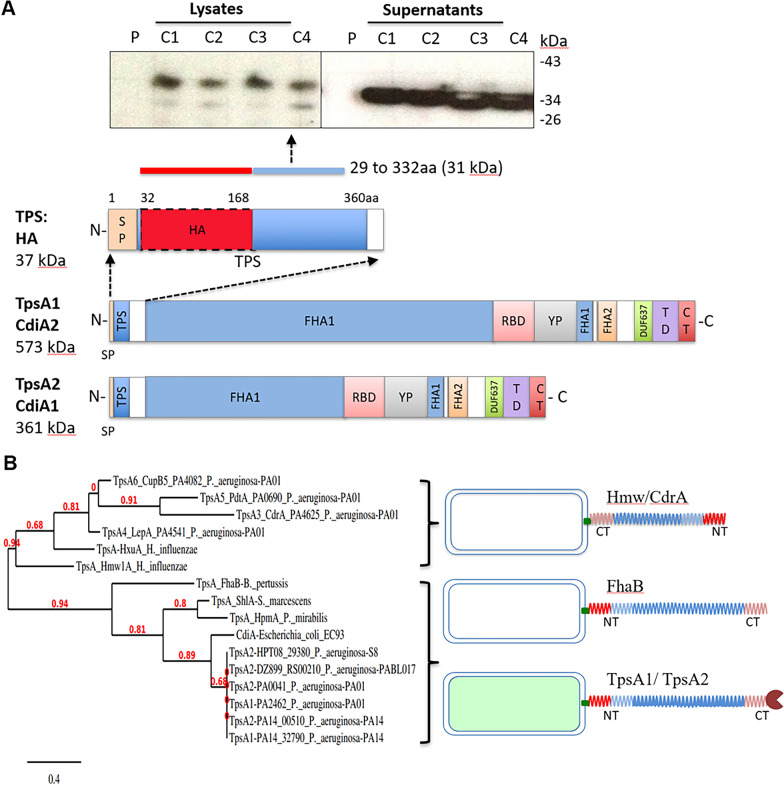

Secretion and expression of N-terminal domain (1–360aa) of TpsA1 protein

Although extremely large proteins TpsA1 and TpsA2 are recognized as surface associated, our analysis of P. aeruginosa culture supernatant proteins showed that both TpsA1 and TpsA2 are efficiently secreted into the culture medium (Additional file 2: Table S2). Therefore, we investigated whether 1–334 amino acid residues of P. aeruginosa TpsA (TpsA-NT31, calculated mol.wt. is 31 kDa without signal peptide) were sufficient for secretion. Since TpsB is essential for TpsA secretion, both P. aeruginosa proteins TpsB (full length) and TpsA-NT (31 kDa) were co-expressed in E. coli by inducing with IPTG. Western blot analysis with anti-histidine-tag antibodies to detect secreted and intracellular TpsA-NT31 indicated that TpsA-NT31 was secreted abundantly into the surrounding medium within 4 h after induction and only a minor quantity of TpsA-NT31 remained intracellular (with signal peptide, 34.8 kDa) or bound (mature, 32 kDa) to the cells (Fig. 1A). N-terminal signal peptide present in secreted proteins is usually sufficient to target proteins to the inner membrane and translocation across the inner membrane [41]. Both proteins TpsB and TpsA co-expressed in this study from plasmid in E. coli BL21 contain signal peptide sequences necessary to target the inner membrane and export. During translocation, the signal peptidase cleaves off the signal peptide, consequently TpsA-NT protein detected in the culture supernatants could be without the signal peptide.

Fig. 1.

TpsA/CdiA protein domains in P. aeruginosa. A The domains of a CdiA from the N-terminus are the conserved two-partner secretion (TPS) transport domain, filamentous hemagglutinin domain 1 (FHA-1), receptor-binding domain (RBD), Tyr/Pro-enriched (YP) domain, second FHA domain (FHA-2), the pre-toxin (TD) domain, and the C-terminus toxin domain (CdiA-CT). Figure was modified from a diagram by Allen et al. [31]. A conserved region found at TpsA N-terminal termed “TPS domain” is necessary for interaction to and secretion by TpsB. Secretion of P. aeruginosa N-terminal domain (1–360 aa) of proteins TpsA1 and TpsA2 (TpsA-NT) expressed in E. coli was confirmed by immunoblot analysis of culture supernatants collected from different clones with anti-Histidine tag antibody. C1, C2, C3, C4 are clones expressing and secreting recombinant protein TpsA-NT (31 kDa) in E. coli BL21 (DE3). P, represents plasmid pET29b + backbone in E. coli BL21 (DE3). B Phylogenetic tree of TPS domains of TpsA NT proteins. The tree shows the subdivision of TpsA proteins into two different families Fha30-like proteins and HMW1-like proteins. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using online tool phylogeny.fr (http://phylogeny.lirmm.fr/). N terminal amino acid residues of TpsA proteins (TpsA1 to 6) of P. aeruginosa were compared with H. influenzae HMW1 and HxuA proteins; B. pertussis FHA protein; S. marcescens ShlA protein; P. mirabilis HpmA protein and E. coli CdiA protein. N-terminal domain is anchored to the bacterial surface and C-terminal proteins are exposed in TpsA1/CdiA1 and TpsA2/CdiA2 proteins

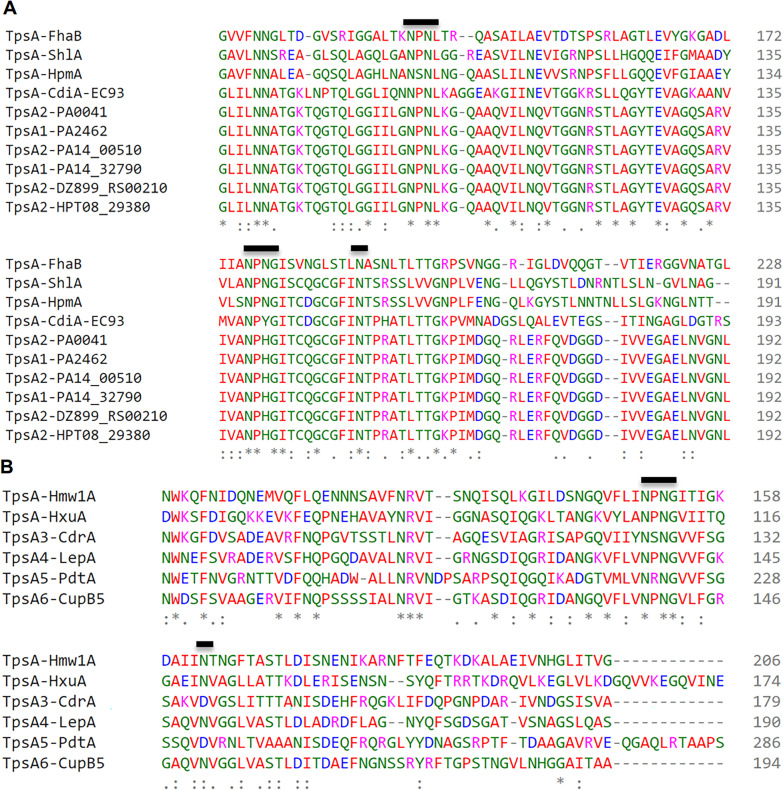

All TpsA proteins share a conserved 250-residue-long N-terminal TPS domain, which is the minimal region essential for secretion of TpsA proteins. TpsB partners belong to outer-membrane proteins of the Omp85 family and the polypeptide transport-associated (POTRA) domains of several TpsB proteins have been shown to specifically recognize the TPS domains of their respective TpsA partners [32, 42]. For the amino acid sequence alignment of TPS domains compared, FHA/FhaC of Bordetella pertussis, ShlA/ShlB of Serratia marcescens, HMW1/HMW1B and HxuA/HxuB of Haemophilus influenza, and CdiA/CdiB of E. coli, which are among the few functionally well-characterized TpsA/TpsB pairs in the TPS family. Fha30-like proteins (TpsA1 & TpsA2) and HMW1-like proteins (TpsA3/4/5/6) are the two subfamilies of TPS domains that have been classified on the basis of protein sequence alignments and appear as distinct groups in the phylogenetic tree of TPS domains (Fig. 1B and Fig. 2). Three motifs have been identified in N-terminal TPS domains that are important for the secretion of TpsA proteins including NPNL box, NPNG box and a single conserved asparagine position [43]. Although all TpsA proteins contain the NPNG motif, only FHA like proteins contain the NPNL motif, but not HMW1. Both P. aeruginosa and E. coli TpsA proteins that are involved in CDI system contain all three conserved motifs necessary for secretion.

Fig. 2.

Multiple sequence alignment of the N-terminal region (1–360 aa) of representative TpsA proteins using CLUSTAL omega (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/msa/clustalo/). The numbering on the left corresponds to the amino acid number for each protein. N terminal amino acid residues of TpsA proteins (TpsA1 to 6) of P. aeruginosa were compared with, B. pertussis FHA protein (A) and H. influenzae HMW1 protein (B). Bold line indicates the position of motifs that have been identified in N-terminal TPS domains that are important for the secretion of TpsA proteins

TpsA-NT-HA domain interaction with mucins and inhibition by sulfated glycans

Since the functional significance of T5SS-NT-domain in P. aeruginosa and the role of HA domain in TpsA in general and CdiA in particular remain unknown, we hypothesized that P. aeruginosa TpsA-NT-HAD may mediate or initiate adhesion to host cell glycans and mucins. Since TpsA-NT-HA domain in TpsA1 and TpsA2 proteins are 100% identical, only TpsA1-NT- (49–332aa, 29 kDa) was expressed in E. coli and purified.

After preliminary screening of recombinant TpsA-NT-HA domain with diverse glycoproteins and polysaccharides using lectin-based ELISA assay, TpsA-NT-HAD was found to interact only with PGM and human ovarian cyst mucins that contain human blood group related glycans (ABH/Lewis type) (Additional file 9: Fig. S2). Characterization of PGM with fucosylated blood group glycans specific antibodies (anti-HBGA MAbs) revealed the presence of multiple HBGAs including blood group A and Lewis-Y, which were predominant glycans present in PGM (Additional file 11: Fig. S3, PGM). On the basis of the lectin reactivity to the PGM in ELISA assays, we observed that glycans specific to lectins AAL (Aleuria aurantia), UEA (Ulex europaeus), DBA (Dolichos biflorus), ConA (Canavalia ensiformis) and LTL (Lotus tetragonolobus) are predominantly present on PGM (Additional file 12: Fig. S4, PGM). However, only LTL that specifically binds to α1,3-fucosylated glycans such as Lewis-X, Lewis-Y and 6′sulfo sialyl Lewis-X could inhibit the interaction of T5SS-NT to PGM in a dose dependent manner (IC50, 17.564 μg/mL, Table 2) [44].

Table 2.

Comparison of average IC50 values and potency of polysaccharides to inhibit TpsA-NT-HAD binding to porcine gastric mucin type III obtained by ELISA

| Inhibitors | IC50 average µg/mL |

Range (µg/mL) | SD | Potency vs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Porcine Gastric Mucin = 1 | Chondroitin sulfate = 1 | ||||

| Dextrans | |||||

| Dextran sulfate-500 kDa | 0.018 | 0.001–0.066 | 0.021 | 1892.000 | 25,909.536 |

| Dextran sulfate 6–11 kDa | 0.194 | 0.046–0.962 | 0.242 | 171.926 | 2354.401 |

| Dextran 450 kDa | NSI | NSI | NSI | NSI | NSI |

| Dextran 9–10 kDa | NSI | NSI | NSI | NSI | NSI |

| Fucoidans and mucin | |||||

| Macrosystis pyrifera | 0.277 | 0.113–0.423 | 0.096 | 120.529 | 1650.556 |

| Undaria pinnatifada | 0.430 | 0.183–9.77 | 0.252 | 77.600 | 1062.674 |

| Fucus vesiculosus crude | 0.491 | 0.111–1.54 | 0.318 | 67.947 | 930.479 |

| Ascophyllum nodusum nutri. 0.5% | 0.736 | 0.405–1.29 | 0.335 | 45.352 | 621.067 |

| A. nodusum + L. digitata (PS-II) | 0.764 | 0.113–0.423 | 0.096 | 43.649 | 597.734 |

| Fucus vesiculosus 95% | 1.008 | 0.21–2.797 | 0.760 | 33.107 | 453.375 |

| κ-carrageenan | 1.101 | 0.667–1.883 | 0.390 | 30.301 | 414.948 |

| Fucus serratus | 1.520 | 0.203–3.099 | 0.796 | 21.954 | 300.648 |

| F. vesiculosus HCl 10′ 30 kDa | 1.690 | 0.1–2.828 | 0.685 | 19.749 | 270.443 |

| F. vesiculosus Aus. 30 kDa | 2.547 | 0.656–7.066 | 0.501 | 13.100 | 179.396 |

| F. vesiculosus—nutri. 0.5% | 2.924 | 0.331–9.67 | 3.908 | 11.411 | 156.262 |

| F. vesiculosus HCl 10' mix | 5.468 | 3.215–5.215 | 1.520 | 6.102 | 83.568 |

| Laminaria digitata | 5.593 | 0.227–21.0 | 5.983 | 5.966 | 81.698 |

| L. japonica | 21.103 | 9.67–44.447 | 9.806 | 1.581 | 21.654 |

| Porcine Gastric Mucin Type III | 33.368 | 10.156–75.117 | 15.115 | 1.000 | 13.694 |

| A. nodusum | 39.886 | 7.51–71.197 | 18.179 | 0.837 | 11.456 |

| F. vesiculosus HCl 60′ 30 kDa | 59.022 | 13.92–113.723 | 34.505 | 0.565 | 7.742 |

| F. vesiculosus HCl 60' mix | 68.958 | 48.184–86.822 | 23.351 | 0.484 | 6.627 |

| l-Fucose, d-Fucose, Fuc-BSA, methyl-b-Fuc, methyl-a-Fuc | NSI | NSI | NSI | NSI | NSI |

| Glycosaminoglycans | |||||

| Chondroitin sulfate-Sigma | 456.950 | 369.911–674.852 | 87.803 | 0.073 | 1.000 |

| Heparin, heparan sulfate, keratan sulfate | NSI | NSI | NSI | NSI | NSI |

| Alginates | |||||

| A. nodusum alginate | 3.587 | 1.243–7.81 | 2.210 | 9.301 | 127.375 |

| Alginic acid | 4.931 | 0.975–13.49 | 5.053 | 6.767 | 92.665 |

| L. japonica alginate | 34.228 | 15.439–55.329 | 11.284 | 0.975 | 13.350 |

| Azotobacter spp. alginate | NSI | NSI | NSI | NSI | NSI |

| Others | |||||

| Lotus lectin (LTL) | 17.564 | 13.943–27.717 | 8.408 | 3.968 | 26.015 |

| Sambucus Nigra lectin (SNA) | 52.924 | 42.695–631.54 | 14,466 | 2.306 | 8.633 |

| Concanavalin A lectin (ConA) | 140.943 | 79.19–237.597 | 84.774 | 0.393 | 3.242 |

| Blood Group Lewis-B | 471.548 | 7.919–23.760 | 60.393 | 0.552 | 0.969 |

NSI: no significant inhibition (IC50 > 1000 µg/mL); Fuc: fucose, nutri.: nutritional grade fucoidan. The IC50 values were estimated by using a free online program from AAT Bioquest (https://www.aatbio.com/tools/ic50-calculator)

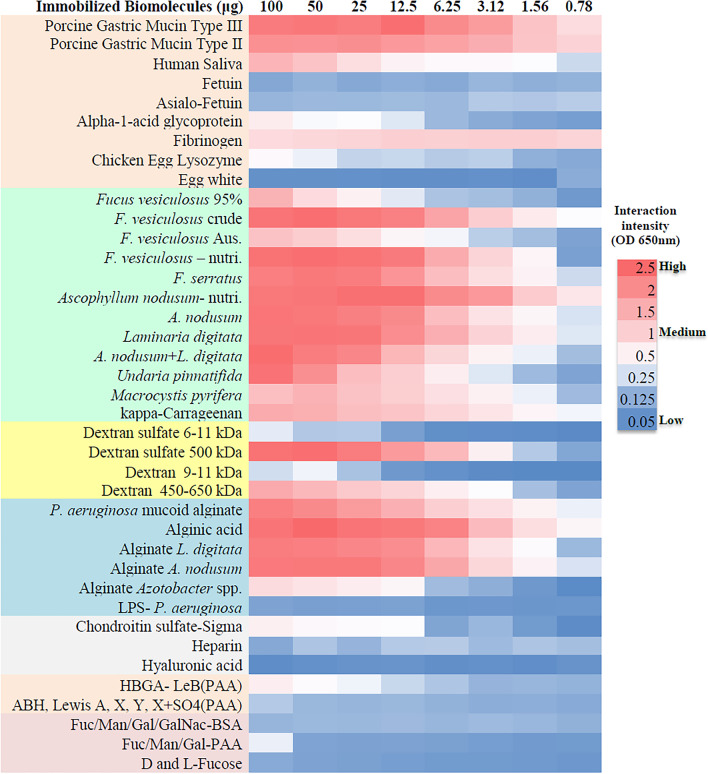

As shown in Fig. 3, TpsA-NT-HAD mostly bound to mucins, sulfate and fucose-rich polysaccharides (fucoidans), sulfated dextrans and marine alginates. Among the blood group glycans tested, it only bound moderately to Lewis-B. Since immobilization efficiency of the polysaccharides may not be the same, inhibition assays were also performed with the polysaccharides, which might represent the interactions between protein and polysaccharide more accurately. Preincubation of TpsA-NT-HAD with various concentrations of biomolecules inhibited the binding to PGM in a dose-dependent manner, fucoidans and sulfated dextrans were the best ligands for TpsA-NT-HAD, followed by marine alginates (Table 2), which indicates specific interaction between TpsA-NT-HAD and PGM. Depending on species, source and season structure of fucoidans vary significantly in branching, linkages (1 → 3) & (1 → 4), sulfation and acetylation, we examined the inhibitory effects of different fucoidans on T5SS-NT-HAD by binding and inhibition studies [45]. Among the fucoidans tested, M. pyrifera, U. pinnatifada, F. vesiculosus crude, A. nodusum nutritional grade and PS-II were the best inhibitors (IC50, < 1 μg/mL) of interaction between TpsA-NT-HAD and PGM. F. vesiculosus 95%, F. serratus, and kappa-Carragenan also showed good inhibitory effect (IC50, 1–1.52 μg/mL). Fucose specific lectin LecB interaction with PGM was not inhibited by fucoidans (Additional file 10: Table S7). In an intestinal cell-based model, adhesion of P. aeruginosa S8 to Caco 2 cells was reduced in the presence of fucoidans in a dose-dependent manner (Additional file 13: Fig. S5 and Additional file 14: Fig. S6). Characterization of fucoidans with lectins revealed that AAL specific glycans were predominant followed by MAL2 and CONA (Additional file 12: Fig. S4, FV & FS). Fucoidans could mimic sialyl Lewis-X, 6’sulfo sialyl Lewis-X, sialyl Lewis-A, Lewis-B and Lewis-Y glycans on the basis of their reactivities to the anti-HBGA MAbs (Additional file 11: Figs. S3, FV & FS).

Fig. 3.

Representative results for interaction between TpsA-NT-HA domain and immobilized biomolecules. A color gradient heat map, with high reactivity (Red) to no reactivity (Blue) based on lectin ELISA OD650 values, has been applied to the well values. Different groups of biomolecules also colored

We predicted that high molecular weight and sulfation level are two important factors for sulfated polysaccharides to be effective inhibitors. We did observe de-sulfation and depolymerization of F. vesiculosus due to mild acid hydrolysis resulted in reduced inhibition or no inhibition of TpsA-NT-HAD, fractions collected after fucoidan was treated with acid for 10 min showed reduced inhibition while the fractions collected after 60 min showed poor inhibitory effect, consequently sequential decrease in potency of F. vesiculosus was observed due to treatment and purification processes (Table 2; Additional file 15: Fig. S7 and Additional file 16: Fig. S8).

Notably, importance of sulfation on polysaccharides was further confirmed when both low and high molecular weight dextran sulfates (DS), which are also considered as analogues of the glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), could inhibit the biding activity of TpsA-NT at nanogram concentrations. Average IC50 values for DS-500 kDa and DS 6–11 kDa were 18 ng/ and 194 ng/mL, respectively. Marine alginates like A. nodusum alginate (9.301) and alginic acid (6.767) were more potent than PGM, while L. japonica alginate potency (0.975) was similar to PGM. Among the blood group glycans tested TpsA-NT could consistently interact only with Lewis-B antigen conjugated to PAA, but inhibition was observed only at high concentrations (IC50, 471.548 μg/mL).

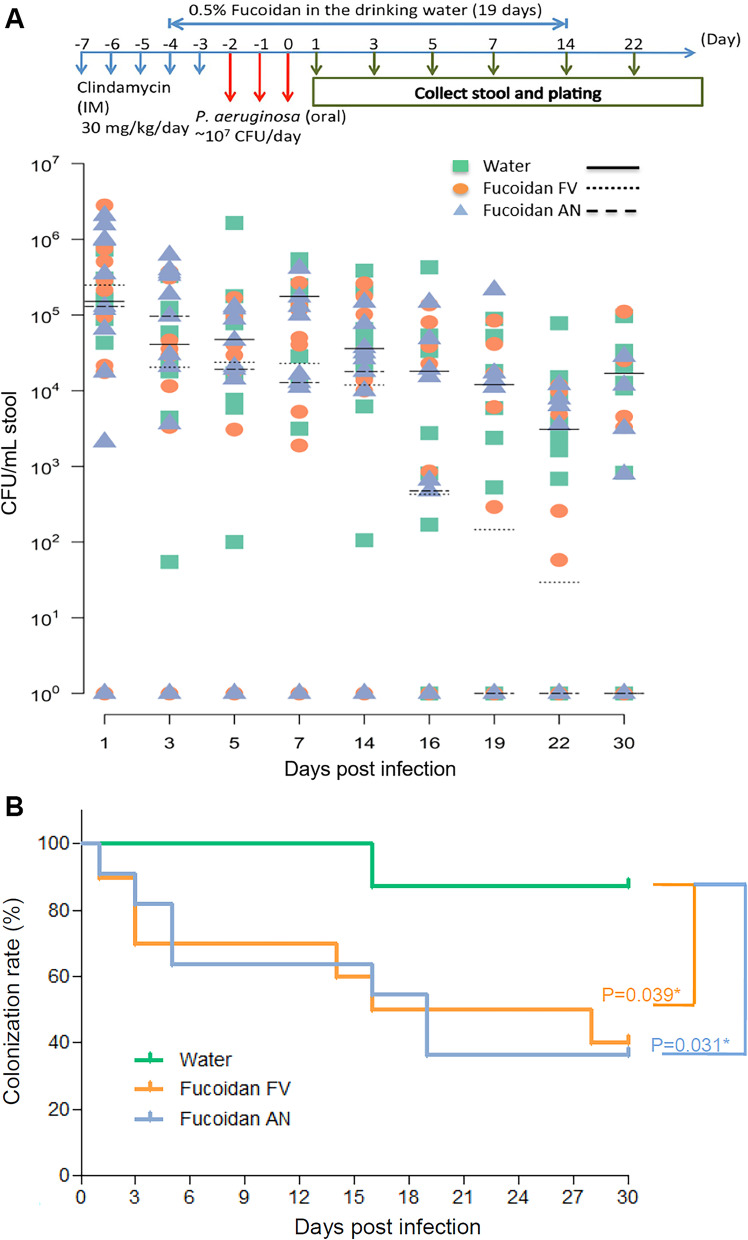

Prophylactic prebiotic fucoidans to reverse bacterial colonization in a mouse model

Among the mice that were fed with fucoidans for 14 days p.i., two patterns of decolonization were observed: (1) P. aeruginosa was eliminated from a higher proportion of the mice with time, (2) but in the remaining mice P. aeruginosa persisted throughout the study period but with declining bacterial loads over time (Fig. 4A). Decolonization of P. aeruginosa from GI tract was evident within first week of p.i., in 45% of A. nodusum fed mice and 30% of F. vesiculosus fed mice (Fig. 4B; Additional file 17: Table S8). On day 14 p.i., which was the last day of fucoidan feeding, around 45% of mice were decolonized. Of note, between p.i. day 15 and day 30 among the fucoidan fed groups proportion of the mice that were decolonized further increased to 60% (P < 0.05). Whereas in the untreated mice even at p.i. day 14, decolonization was not observed, however between day 15 and day 30 decolonization was found in only < 15%.

Fig. 4.

Duration of fecal shedding of P. aeruginosa after prophylactic fucoidans-supplementation. A Timelines of fecal shedding tests were scheduled for 30 days, including 2 days before and 14 days treatment of fucoidans FV (Fucus vesiculosus) and AN (Ascophyllum nodusum) after challenge of Shanghai-fever strain of P. aeruginosa. Negative control (NC) was the mouse challenged with water alone. Oral challenge of P. aeruginosa (1.0 × 107 CFU) was applied for three days from Day-2 to Day 0. Fucoidans FV, and AN (0.5% in water, w/v) were used to feed mice (10 mice per each group) from Day-4 to Day + 14. The horizontal bars indicate median values of CFUs in stool of individual animals at different points in time (days post-infection). (B) Kaplan–Meier curves displaying P. aeruginosa decolonization rates after treatment of fucoidans FV (Fucus vesiculosus) and AN (Ascophyllum nodusum). P. aeruginosa detection in stool was considered positive carrier. P. aeruginosa colonization rates in the gastrointestinal tract at the end of the study in mice were significantly different between the groups with and without fucoidan treatment

Among the mice that persisted with P. aeruginosa in the GI tract, bacterial counts gradually declined significantly from p.i. day 3 through day 30 in both the fucoidan fed groups (Day 1 vs. day 3 to 30) (Fig. 4B). Remarkably, in the fucoidan fed groups mice that were once decolonized were found to be resistant to further re-colonization despite housing one group in one cage, indicating re-colonization resistance by altered gut microbiota (Additional file 18: Fig. S9).

Reversal of gut dysbiosis by fucoidans

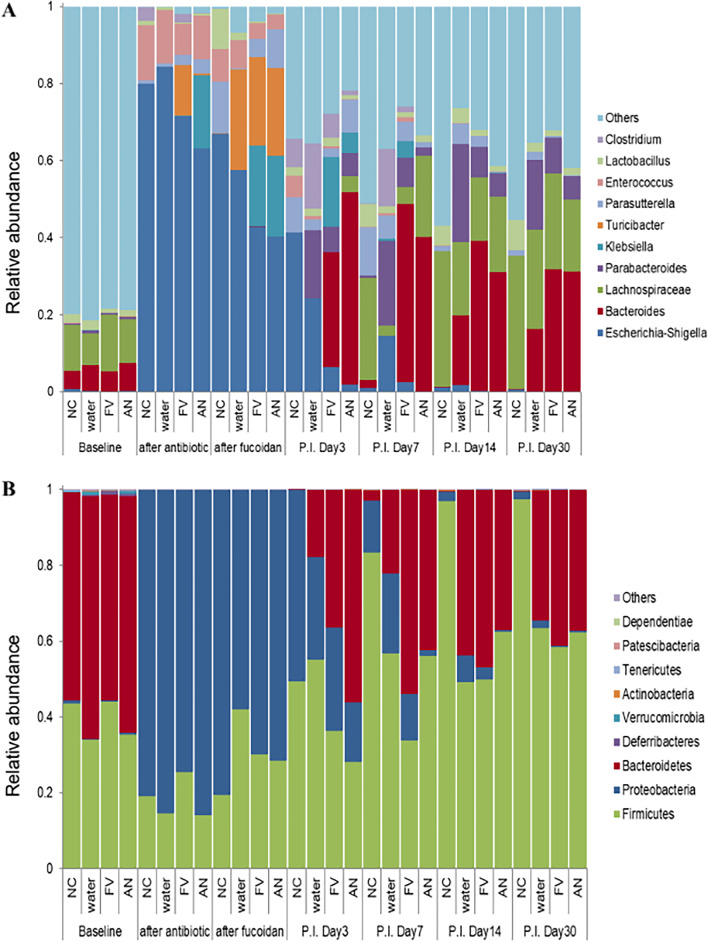

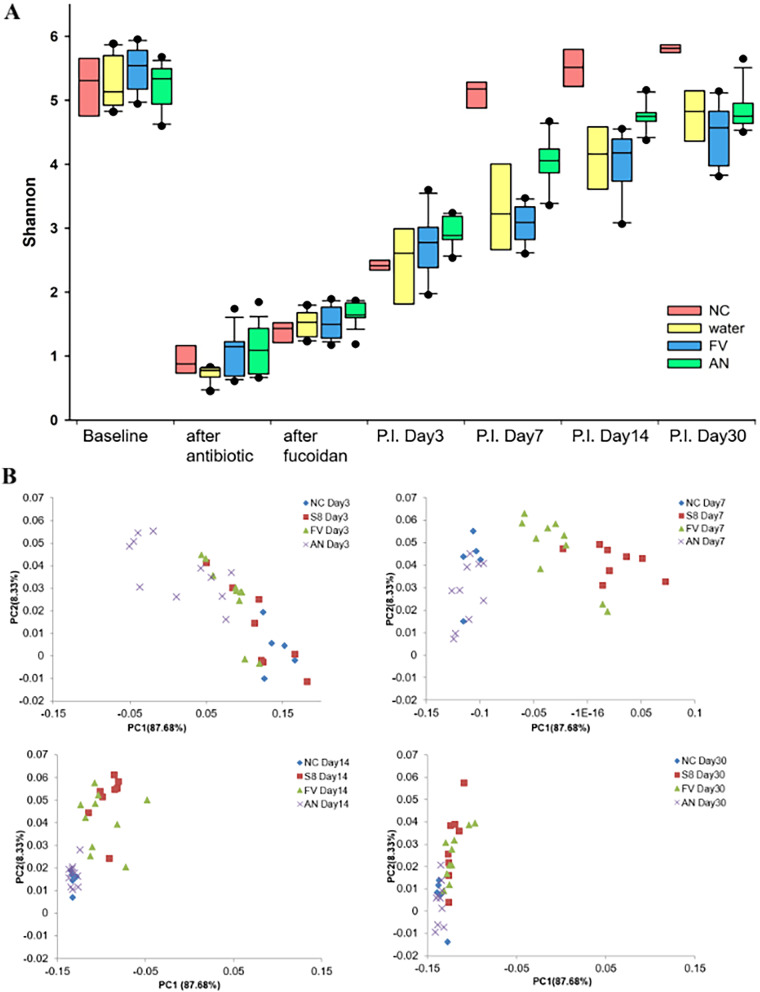

We observed that GI tract colonization by P. aeruginosa in healthy mice was possible only after antibiotic treatment, therefore commensal bacteria residing in GI tract could mediate colonization resistance against P. aeruginosa S8 including, Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group, Bacteroides and Ruminococcaceae_UCG-014 which were predominant bacterial genera (relative abundance ≥ 10% each) found in the fecal microbiota (Fig. 5A). After a 5-day course of intramuscular administration of clindamycin (0.6 mg/day) to naive mice, across all groups there was severe gut microbiota dysbiosis and substantially reduced the bacterial diversity (P < 0.00001) (Fig. 6). Of note, Lachnospiraceae and Bacteroides populations were nearly eliminated and Akkermansia remained undetectable throughout the study. But, simultaneously extraordinary increase in abundance of Enterobacteriaceae (> 68.5%, P < 0.001) and Enterococcaceae (> 8.06%) populations were also recorded. These post-antibiotic events in the GI tract were found to be favorable for colonization by P. aeruginosa in healthy mice. However, after oral fucoidan supplementation in mice, by p.i. day 3, remarkable expansion in abundance of Bacteroides (29–50% RA, P < 0.001) from previously undetectable levels eventually replaced Enterobacteriaceae members as the most abundant genus (< 25% RA). In contrast, Parabacteroides was the predominant genus that mediated recovery from dysbiosis from p.i. day 3 to day 14 in the untreated group (Additional file 19: Fig. S10).

Fig. 5.

Relative abundance at the genus level (A) and phylum level (B) between fucoidan treatment groups and untreated groups. Fucoidans treatment groups FV (Fucus vesiculosus) and AN (Ascophyllum nodusum). Controls were untreated water only (W) and uninfected negative controls (NC). The paired t-test analysis was performed to compare microbiota composition between groups at different levels (phyla and genus)

Fig. 6.

Bacterial diversity in the fecal microbiota of the study groups. A Shannon index of alpha diversity in the gut microbiota were compared among the study groups. B Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) 2D plots for beta diversity in the fecal microbiota of the study groups. The beta-diversity of microbiota was compared using the PCoA plot based on Bray–Curtis distance distances. Fucoidans treatment groups FV (Fucus vesiculosus) and AN (Ascophyllum nodusum). Controls were untreated water only (W) and uninfected negative controls (NC)

Notably, at p.i. day 7, Bacteroides and Parabacteroides were the two most prevalent genera (54% RA, P < 0.001) in the FV supplemented group, while in the AN supplemented group Bacteroides and Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group (61% RA, P < 0.001) were most prevalent. Consequently, Enterobacteriaceae was nearly eliminated in AN supplemented group (< 1% RA, P < 0.001) and strongly reduced in FV group (< 7% RA, P < 0.001) when compared to untreated group (< 15% RA). In the fecal samples from p.i. day 14 and day 30, no significant changes at genus level in % relative abundance were noted in both AN and FV treatment groups, indicating stable maintenance of established conventional community members for at least 2 weeks after discontinuation of fucoidan supplementation (Additional file 19: Fig. S10).

At the phylum level in the healthy control mice, Firmicutes (39.21%) and Bacteroidetes (58.87%) were predominant phyla in the fecal microbiota, with a combined relative abundance of 98.08% ± 0.21 and the F:B ratio ranged between 0.5 and 0.82 (Fig. 5B). After clindamycin treatment, % RA of Firmicutes decreased by 50% to 18.31% and Bacteroidetes were nearly eliminated (RA was 0.042%, P < 0.001). But, at the same time %RA of Proteobacteria remarkably increased to 81.62% from 0.46% (P < 0.001). Relative abundance of Firmicutes in the non-supplemented groups increased to ≥ 40% earlier (p.i. day 3) than in fucoidans supplemented groups (p.i. day 7–14) (Additional file 20: Fig. S11). Notably, Bacteroidetes abundances increased substantially and peaked earlier in fucoidans supplemented infected groups (day 3 for FA; day 7 for FV, P < 0.001) than in non-supplemented infected group (day 14). On p.i. day 30 in all the infected groups relative abundance of Firmicutes (61.35%) was higher than Bacteroidetes (37.45%), thereby increasing the F:B ratio to 1.67 ± 0.25, this ratio is higher than in healthy control mice (0.5–0.82) (Fig. 5B).

PCoA revealed that the healthy baseline microbial composition formed a cluster significantly (that is distinctly) separated from clindamycin treated and fucoidan supplemented mice (Fig. 6B). Among the P. aeruginosa infected groups at p.i. day 7 samples from fucoidans supplemented groups and non-supplemented control group clustered separately.

Discussion

In P. aeruginosa and other gram-negative bacterial pathogens primary function of surface anchored proteins similar to TpsA1/CdiA2 and TpsA2/CdiA1 were found to promote bacterial competition through contact-dependent growth inhibition systems (CDI) [32]. However, in this study proteomic analysis revealed the presence of TpsA1 and TpsA2 in the culture supernatants. Additionally, when P. aeruginosa N-terminal TPS domain (1–360 aa) of TpsA1/TpsA2 (TpsA-NT) and its cognate transporter TpsB were expressed in E. coli, TpsA-NT (31 kDa) protein fragment was secreted into the culture media abundantly, suggesting that in addition to contact-dependent growth inhibition and/or contact-dependent growth signaling, secreted CdiA proteins might play a role in adhesion and colonization. Due to high homology (> 99% identity) at the N-terminal amino acid sequences (1–360 aa) between TpsA1 and TpsA2 proteins, secretion could be mediated either by TpsB1 or TpsB2. Homology between TpsA4 (LepA) and TpsA6 (CupB5) is around 56% at the N-terminus, but Garnett et al., showed that both the proteins could be translocated by TpsB4 (LepB), a cognate partner TpsA4 (LepA) [43]. Amino acid sequence alignment also revealed that, both P. aeruginosa and E. coli TpsA proteins contain all three conserved motifs necessary for secretion, therefore, E. coli protein expression system is suitable for expression of P. aeruginosa TpsA1 and TpsA2 proteins. Studies on structural and functional analysis of recombinant TpsA domains expressed in P. aeruginosa and E. coli might demonstrate similar results. Previously, to determine the structure of a H. influenzae TpsA protein secretion domain, HxuA301 (TpsA) and HxuB (TpsB) proteins were expressed successfully in E. coli strain BL21(DE3) [46].

Over the years, the N-terminal TPS domains of varying lengths (around 300 aa) were found to be both necessary and sufficient for secretion of FHA, HMW1 and ShlA by their cognate TpsB transporters [42, 47, 48]. In FHA like proteins TpsA1 & TpsA2 play a role in CDI with conserved N-terminal domain anchored to the bacterial surface and variable C-terminal CdiA effector proteins that are exposed [42]. In contrast, evidence from HMW1-like proteins TpsA3 (CdrA) suggested N-terminal end could be translocated across the outer membrane [48, 49].

Although bioinformatics tools for protein structure and function analysis tend to predict the presence of conserved HA domain at the start of N terminus (between 30 and 200 aa) of TpsA proteins in gram-negative pathogens [50, 51], there is no experimental evidence to support the role of hemagglutinin or lectin function, at least in proteins similar to FHA-NT. In this study we found that purified recombinant TpsA-NT-HA domain can bind to PGM that contains multiple HBGAs (ABH/Lewis type). When fucosylated glycans present on PGM were blocked with fucose specific lectins, TpsA-NT-HA domain interactions to PGM was inhibited only by LTL suggesting that both TpsA-NT and LTL can specifically bind to fucosylated glycans such as Lewis-X, Lewis-Y and 6’sulfo sialyl Lewis-X or share some glycan epitopes present on HBGAs [44]. Among the HBGAs tested, we found that TpsA-NT-HAD could consistently bind to and was inhibited by Lewis-B only with low affinity (471 μg/mL). It is possible that valency, spacing and orientation of the commercial HBGAs used for screening are different from the HBGAs present on PGM or natural interactions between TpsA-NT-HAD and PGM is multivalent i.e. TpsA-NT-HAD can bind to multiple HBGAs present on PGM simultaneously [52, 53].

Several human enteric pathogens bind to fucosylated human histo-blood group antigens (HBGAs) expressed on the gut mucosa, including Campylobacter jejuni, Norwalk virus and Helicobacter pylori [54, 55]. Mucins like, PGM, which contains multiple fucosylated, HBGAs (type A, H1, and Lewis b antigens) was found to bind multiple norovirus strains due to lectin-like recognition by the VP1 capsid protein [54]. The H. pylori adhesins BabA and SabA bind to mucin HBGAs, Lewis B and sialyl-Lewis A and sialyl-Lewis X, respectively [55]. By targeting lectin LecB, which can bind to fucosylated oligosaccharides, A, B, H, Lewis-A and Lewis-X blood, with multivalent fucosyl dendrimers which have 100-fold higher affinity toward LecB than fucose, complete inhibition of biofilm formation and dispersion was observed in P. aeruginosa isolates [56].

Like LecB, interactions of a secreted TpsA-NT-HA activity with HBGAs on host cell surface glycoproteins or mucins could play a crucial role in which might benefit P. aeruginosa to colonize the ultimate host tissue niche (lung, intestine and skin). By inhibition assays fucoidans (α-1,3-Fuc and α-1,4-Fuc sulfated polysaccharides) were found to be potent inhibitors of TpsA-NT interaction with mucin, this could be due to the presence of some structural motifs that could mimic predominantly sialyl Lewis-X, 6’sulfo sialyl Lewis-X and sialyl Lewis-A, suggesting that interaction between TpsA-NT and fucoidans is due to the molecular mimicry of HBGA glycans like sialyl Lewis-X. Several studies have shown that sulfated polysaccharides such as fucoidans, dextran sulfate, heparin and heparan sulfate, or some of their derivatives were able to prevent P-selectin binding to sialyl Lewis-X [57, 58].

Since dextran sulfates were the most potent inhibitors of T5SS-NT-HAD interaction to PGM it is tempting to speculate the use of DSS oral formulations against P. aeruginosa GI tract infections. However oral administration of DSS (36–50 kDa, 2–10%) induces colitis in laboratory animal models and mimics human ulcerative colitis pathology [59]. Currently we can only speculate that oral administration of high molecular weight DSS in non-colitogenic doses (0.01–0.1%) might be sufficient to neutralize T5SS-NT-HAD and other the virulence factors. Furthermore, desulfation and depolymerization of fucoidans and dextrans reduced the inhibitory potency, this indicates that high potency of fucoidans when compared to gastric mucins might be due to two mechanisms (1) molecular mimicry of blood group glycotopes by fucoidans and (2) interaction between positively charged residues present in TpsA-NT-HA with sulfate groups present in sulfated polysaccharides.

Preliminary studies on B. pertussis FHA indicated that the sulfated polysaccharides (heparin, dextran sulfate, and fucoidan) were able to inhibit B. pertussis FHA binding to immobilized heparin and attachment of CHO cells to FHA and predicted that specific glycosaminoglycan binding domain was located near the N-terminus of the FHA protein [60]. In our adhesion assay conditions, pre-incubation of P. aeruginosa with fucoidans reduced adhesion to Caco 2 cells. However, due to cytotoxic nature of clinical isolates and short interaction time between P. aeruginosa and epithelial cells, expression and/or secretion of TpsA may not be sufficient to see dramatic differences with fucoidan treatment. It is possible that along with TpsA1 and TpsA2, interactions of other unknown fucose-specific adhesins with glycoproteins are inhibited by fucoidans in the mammalian gastrointestinal tract. Although LecB can bind to host fucosylated blood groups glycans, we found that fucoidans used in this study did not inhibit the LecB binding to porcine gastric mucin, therefore we rule out the possibility of fucoidans inhibiting LecB binding to intestinal cells. Since the negative charge of the fucoidans results from the presence of sulfate residues in the C-2 and C-4 positions, occasionally in C-3, it might also function non-specifically by forming complexes with other positively charged amino acid residues present on adhesins of P. aeruginosa [61]. Further experiments are needed to examine potential interactions between fucoidans and flagella and type 4 pili, which are the other major adhesins of P. aeruginosa, capable of binding to host epithelial gangliosides, asialoGM1 and asialoGM2 [62].

Although alginates did not show high potency like dextran sulfates or fucoidans, among the subset of P. aeruginosa strains, alginate is a major component of extracellular polysaccharide matrix [63], even low affinity T5SS-NT-HAD interactions with alginate may play a role in neighboring cell–cell interactions and biofilm development. Our findings indicated dual functionality of TpsA-NT: (1) TPS domain on TpsA is targeted to TpsB and truly secreted onto the bacterial surface or into the surrounding culture medium; and (2) Subsequently, hitherto unknown TpsA-NT lectin like activity may mediate binding to multiple HBGAs present on mucins, glycosaminoglycans and sulfated polysaccharides like fucoidans. Currently, we can only speculate that multidomain TpsA1/TpsA2 proteins could confer intercellular binding by a two‐way handshake interactions through different domains, TpsA1/TpsA2 proteins that are released bind to mucins with N-terminus but the other C-terminal domains could still interact with TpsA1/TpsA2 proteins domains that remain anchored to the bacterial cell surface. In P. aeruginosa, TPS system, which encodes secreted adhesin CdrA was shown to promote auto-aggregation in liquid culture and biofilm formation using CdrA-Psl and CdrA-CdrA interactions [49]. Ag43 (Antigen 43), a type Va auto-transporter from E. coli utilizes self-recognizing handshake interaction mechanism to flocculate, which is beneficial in colonization, immune evasion and persistence in the host [64].

Since fucoidans are widely used in normal diets in East Asian countries and increasingly utilized as an ingredient in some dietary supplement products, we hypothesized that by using nutritional grade fucoidans, we may reduce P. aeruginosa colonization in GI tract. We observed that over time proportion of the mice that were decolonized further increased to 60%, while in the mice with persistent colonization, bacterial loads decreased significantly; on the other hand, decolonization at the end of the study period was found in only < 15% of the untreated mice.

P. aeruginosa overcomes the resistance to colonization mediated by gut microbiota and innate immune system [5, 65]. We also observed dramatic changes in gut microbiota. Intestinal microbiota was lower in richness and diversity after clindamycin treatment, compared to healthy controls. This post-antibiotic event, which was essential to facilitate P. aeruginosa colonization of the gut, suggests that members of Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes phyla promote resistance to colonization by P. aeruginosa, while the abundance of Proteobacteria enables pathogenic species colonization.

Among the fucoidan-supplemented mice, in the first week of decolonization Bacteroides was the most abundant genus, followed by Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group and Parabacteroides. In contrast in the control group, Parabacteroides was the predominant genus. After the withdrawal of fucoidan supplementation on day 14, between day 15 and day 30, stability at genus level was established in all groups mainly by Bacteroides, Lachnospiraceae_NK4A136_group and Parabacteroides; however, no significant decolonization was observed in the control group, suggesting a prophylactic role for prebiotic fucoidans in the treated groups. Overall, these important findings indicated at least two mechanisms by which prebiotic fucoidans could combat the colonization of P. aeruginosa in the mouse model, one involving inhibition of secreted virulence factors (TpsA/CdiA) interactions with mucins and the other by enriching the growth of Bacteroides.

Our study observations are consistent with earlier studies which reported that among the clindamycin-pretreated mice, Bacteroides were nearly eliminated or remained undetectable, Enterobacteriaceae proportions increased significantly while the reduction in Lactobacillus proportion was modest [66, 67]. Although at lower proportions, the continued presence of members of Firmicutes in clindamycin-pretreated mice may partially explain that for recovery from dysbiosis, members of Firmicutes play a major role among the fucoidan non-supplemented mice. Studies on impact of clindamycin treatment on humans also demonstrated that members of the Bacteroides species in the fecal microbiota remained reduced for 2 years following clindamycin therapy [68].

Studies on effectiveness of fucoidans to restore gut microbiota composition after antibiotic treatment are limited. In a mouse model of antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD), a recent study reported that dietary sulfated polysaccharide isolated from Gelidium pacificum Okamura (GPOP-1) restored the gut microbiota composition by significantly increasing the abundance of Bacteroides, Oscillospira, Bifidobacterium and decreasing the abundance of Parabacteroides, Sutterella, AF12. Furthermore, GPOP-1 improved mucosal barrier function, downregulated inflammatory cytokines and increased the production of SCFAs [69]. In another study, in mice treated with ciprofloxacin-metronidazole, dietary Ascophyllum nodosum improved colonic health and partially restored the dysbiosis of gut microbiota by increasing the abundance of beneficial bacteria (Ruminococcaceae_UCG_014 and Akkermansia) and decreasing the abundance of harmful bacteria (Proteus and Enterocococus) [70]. Of note, Akkermansia spp. (associated with human health) had no role in decreasing the P. aeruginosa colonization and fucoidans cannot restore Akkermansia spp. once eliminated from the GI tract by clindamycin [71].

In general, bacteria colonizing the intestinal epithelium are exposed to highly sulfated glycans present on mucins, glycosaminoglycans and sulfated polysaccharides (fucoidans) used in diets, which are potential carbon and nitrogen sources for cell proliferation and metabolite biosynthesis, but their high sulfate content could prevent their degradation [72–74]. Specialized organisms like Bacteroides spp. containing both glycoside hydrolases and sulfatases could effectively depolymerize and utilize complex carbohydrates for metabolism and to release monosaccharides into the gut lumen for other organisms to scavenge [72, 73]. Previously, Benjdia et al. demonstrated that deletion of Bacteroides thetaiotaomicron genes encoding for anaerobic sulfatase-maturating enzyme (anSME) (BT0238) resulted in loss of sulfatase activity and impaired ability to use sulfated glycosaminoglycans (chondroitin and heparin) as carbon source [72]. Recently Sato et al. showed that most Bacteroides species could degrade and assimilate sulfated GAGs and mucin that are available to the gut microbiota and secreted essential amino acids, γ-amino butyrate (GABA) and short-chain fatty acids which are needed for human health [75]. Based on the results of this study, we can hypothesize that, among the fucoidans supplemented mice, Bacteroides spp. may effectively depolymerize fucoidans to fucose as carbon and nitrogen source. Consequently, selectively promote the growth of members of genus Bacteroides to occupy the niche space that overlaps with P. aeruginosa.

Finally, despite being housed in a single cage fucoidans treated mice that were once decolonized could not be recolonized by P. aeruginosa, suggesting fucoidans may also limit the transmission of pathogens through fecal to oral route. In a mouse infection model Bachta et al. showed that P. aeruginosa can spread from the bloodstream to the gallbladder where it could multiply to high numbers, and subsequently to the intestines and feces, thereby allowing transmission of P. aeruginosa to uninfected animals [24]. We therefore assume that prophylactic supplementation of fucoidans might be beneficial to some patients in the clinical settings, as a recent study in the US observed that in the ICU setting the piperacillin-tazobactam treatment contributed to microbiota disruption characterized by loss of diversity and protective taxa, and subsequent carbapenem-resistant P. aeruginosa colonization [5]. Burke et al. further reported that cystic fibrosis patients who have been treated with ≥ 5 courses of intravenous antibiotics per year had the lowest Bacteroidetes and highest Firmicutes proportions in the gut [76].

There are limitations of this study. Fucose utilization by intestinal commensal like Bacteroides was not analyzed and the level of fecal short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as acetate, propionate and butyrate were not evaluated in the fucoidan-supplemented mice [19, 77]. Although we did not evaluate the role of metabolites produced by fucoidans enriched microbiota in improving the gut homeostasis, emerging evidence tends to support the hypothesis that Bacteroides and Bacteroides-derived propionate is beneficial to individuals with cystic fibrosis [78]. By using an in vitro fermentation model Liu et al. demonstrated that among the individuals with strong utilization of sulfated polysaccharides, gut microbiota possessed either more Parabacteroides or more Bacteroides, consequently more beneficial metabolites [79].

Conclusions

Fucose-rich glycans-targeting adhesins may play a major role in mediating P. aeruginosa attachment to mucins in gastrointestinal tract, which is evident by the robust decolonization effect of marine prebiotic fucoidans. We demonstrated two mechanisms by which fucoidans mediate their protective effects: first, inhibition of virulence factors (TpsA/CdiA) interactions with mucins and second, selectively promoting the growth of beneficial Bacteroides species. Further studies are needed to examine the clinical application of fucoidans to prevent P. aeruginosa colonization and infection.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 2: Table S1. Strains used in this study are listed below.

Additional file 3: Table S2. Two-partner secretion (TPS) family TpsA proteins in culture supernatants identified by LC–MS/MS proteomic analysis.

Additional file 4: Table S3. Primers used in this study are listed below.

Additional file 5: Table S4. Polysaccharides used in this study.

Additional file 6: Table S5. Antibodies used in this study.

Additional file 7: Table S6. Lectins used in this study.

Additional file 8: Fig. S1. Haemagglutinin domains (HAD) present at N-terminus of TpsA, Type V secretion system proteins in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Six different TpsA proteins can be found in P. aeruginosa PA14 strain. Haemagglutinin domains (HAD) are very well conserved in all the T5SS proteins. Both Tps1 and Tps2 protein sequences can be found in genomes of > 80 strains in Pseudomonas Genome Database (PGDB). Images were generated by BLAST program http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi.

Additional file 9: Figure S2. Preliminary screening for interaction of TpsA-NT-HAD with different substrates coated on the microliter plate. Porcine gastric mucin type III (Sigma) showed high reactivity in the ELISA assay. Alfa glycoprotein (AGP), human ovarian cyst mucin (HOC), bovine submaxillary mucin (BSM), pig submaxillary mucin (PSM). Numbers indicate fractions. Porcine gastric mucin #4, a blood group A + H substance, that was derived from crude Porcine stomach mucin. Treatment of mucin #4 with HCl (pH 2.0, 90 min, 100 °C) yields Porcine gastric mucin #9, while acid hydrolysis (pH 1.5, 100 °C, 2 and 5 h) gives Porcine gastric mucins #14 and #21, respectively [12].

Additional file 10: Table S7. IC50 values of polysaccharides to inhibit LecB-PA01 monomer from binding to Porcine Gastric Mucin Type III obtained by ELISA.

Additional file 11: Figure S3. Binding of blood group antigen-specific antibodies to porcine gastric mucin type III (PGM), Fucus vesiculosus fucoidan (FV) and Fucus serratus fucoidan (FS). TpsA-NT-HAD indicates N-terminal hemagglutinin domain in TpsA1 and TpsA2 proteins. Representative results for interaction between antibodies and immobilized PGM, FV and FS. A color gradient heat map, with high reactivity (Red) to no reactivity (Blue) based on lectin ELISA OD values, has been applied to the well values. Antibodies used in this study are shown in Additional file 6: Table S5.

Additional file 12: Figure S4. Binding of specific plant lectins fucoidans, Fucus vesiculosus crude (FVC), Fucus vesiculosus 95% (FVP), Fucus serratus fucoidan (FS) and Ascophyllum nodusum (AN). Previously well-characterized porcine gastric mucin type III (PGM) was used as s positive control. Representative results for interaction between plant lectins and immobilized PGM, FVC, FVP, FS and AN. A color gradient heat map, with high reactivity (Red) to no reactivity (Blue) based on lectin ELISA OD values, has been applied to the well values. Note: Dilutions of lectins AAL and ConA in buffer were fourfold. Reactivity was low with other lectins including, SNA, PNA, GNA, DFL, WGA, SBA, DBA. Carbohydrate specificities of major plant lectins used in this study are shown in Additional file 7: Table S6.

Additional file 13: Figure S5. Inhibition of P. aeruginosa S8 adhesion to Caco-2 intestinal cells by Fucus vesiculosus fucoidan (FV) (A) and Fucus serratus fucoidan (FS) (B). P. aeruginosa S8 were pre-incubated with fucoidans in 250-μl DMEM medium for 1 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2 and added to monolayers of Caco-2 cells with an MOI of 10 (2 X 105 cells) and incubated for additional 1 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Significant differences using Chi Square test in adhesion in comparison to the adhesion of bacteria incubated without fucoidan are indicated by asterisk (**, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001). MOI: Multiplicity of infection (Bacterium: host cell).

Additional file 14: Figure S6. Inhibition of bacterial adhesion to Caco-2 intestinal cells in the comparison of fucoidans with monosaccharides. P. aeruginosa S8 (A) and ESBL-producing ST131 E. coli as well as Non-ESBL-producing ST131 E. coli (B) were tested. Each test was pre-incubated with for 1 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2 and added to monolayers of Caco-2 cells (2 X 105 cells) and incubated for additional 1 h at 37 °C in 5% CO2. Fucoidans (FV, Fucus vesiculosus; FS, Fucus serratus; LJ, Laminaria Japonicia) were used (each 12.5 mg/mL). Monosaccharides (10 mM), including dextran (Dex), mannose (Man), glucose (Glc), D-fucose (D-F), were tested. Significant difference in inhibition of bacterial adhesion with fucoidan treatment compared to the adhesion without fucoidan treatment is indicated by asterisk (**, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001). ESBL: extended-spectrum β-lactamase; ns: no significance.

Additional file 15: Figure S7. Sulfate content of fucoidan samples after thermal treatment (T) at 80 °C. A, 10 and B, 60 min; and after C, overnight acid hydrolysis at 80 °C to liberate sulfate ions in thermally treated samples. HMW-untreated high molecular weight fucoidan Fv (Fucus vesiculosus 95%) as control. T-purified – thermally treated fucoidan Fv, its filtrate and mixture of both (mix). T10 and T60- purified Fv (Fucus vesiculosus 95%) obtained after 10 or 60 min at 80 °C, purified and hydrolyzed in HCl overnight at 80 °C to release sulfate ions.

Additional file 16: Figure S8. Fucose content of fucoidan Fv (Fucus vesiculosus 95%) samples after thermal (T) and thermal treatment and acid (T + A) treatment at 80 °C. A,D 10 and B,E 60 min; and after C,F overnight acid hydrolysis at 80 °C to liberate sulfate ions and sugar monomers. HMW-untreated high molecular weight fucoidan Fv (Fucus vesiculosus 95%) as control.

Additional file 17: Table S8. Significant reductions in fecal P. aeruginosa load among the study groups during the study period.

Additional file 18: Figure S9. Decolonization and recolonization in individual mice after fucoidan-treatment. Time lines of fecal shedding tests were scheduled for 30 days, including 14 days treatment of fucoidans Fv (Fucus vesiculosus) and FA (Ascophyllum nodusum) after challenge of Shanghai-fever strain P. aeruginosa S8. Negative control (NC) was the mouse challenged with water alone. Oral challenge of P. aeruginosa (1.0 × 107 CFU) was applied for three days from Day-2 to Day 0. Fucoidans FVF, and ANF (0.5% in water, w/v) were used to feed mice (10 mice per each group) from Day-4 to Day + 14.

Additional file 19: Figure S10. Changes in relative abundance at genus level were compared between groups on post infection (P.I.) day 3, 7, 14 and 30. Differences between groups were calculated using a t-test, numbers above columns indicate P values (significant difference, P < 0.05).

Additional file 20: Figure S11. Changes in relative abundance at phylum level were compared between groups on post infection (P.I.) day 3, 7, 14 and 30. Differences between groups were calculated using a t-test, numbers above columns indicate P values (significant difference, P < 0.05).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the members of Proteomics Core Facility, Chang Gung University and Chang Gung Microbiota Therapy Center, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital for technical support. The authors also acknowledge the generous gift of ovarian cyst mucins from Dr. Albert M. Wu, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan.

Author contributions

RPJ and AD contributed to the experimental plan, performed research, analysed the data and drafted the initial draft manuscript and the revised manuscript. C-LC contributed to the TPS/CdiA experimental plan, analysed the data, commented on the manuscript. K-YC contributed to the proteomics experimental plan, performed research and analysed the data. YF and Y-MY contributed to the microbiota experimental plan, performed research and analysed the data. C-HC, Y-HW, and H-JC contributed to the mouse model experimental plan, performed research and analysed the data. Y-CL contributed to the fucoidans and ELISA experimental plan, analysed the data, commented on the manuscript. C-HC conceived the overall research plan, analysed the data and edited the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by Grants 106-2314-B-182A-133-MY3 (to C-HC) and 109-2314-B-182A-151 (to RPJ) from Ministry of Science and Technology and CORPG3J0103 (to C-HC) and CMRPG3J0641‒3 (to RPJ) from Chang Gung Memorial Hospital.

Availability of data and materials

Data are available upon request. The majority of results from this study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary figures and tables.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not required.

Consent for publication

Not required.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rajendra Prasad Janapatla and Anna Dudek contributed equally

References

- 1.Ruiz-Roldán L, Bellés A, Bueno J, Azcona-Gutiérrez JM, Rojo-Bezares B, Torres C, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates from Spanish children: Occurrence in faecal samples, antimicrobial resistance, virulence, and molecular typing. Biomed Res Int. 2018;2018:8060178. doi: 10.1155/2018/8060178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Estepa V, Rojo-Bezares B, Torres C, Sáenz Y. Faecal carriage of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in healthy humans: antimicrobial susceptibility and global genetic lineages. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2014;89(1):15–19. doi: 10.1111/1574-6941.12301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Venier AG, Leroyer C, Slekovec C, Talon D, Bertrand X, Parer S, et al. Risk factors for Pseudomonas aeruginosa acquisition in intensive care units: a prospective multicentre study. J Hosp Infect. 2014;88(2):103–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2014.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson JK, Smith G, Lee MS, Venezia RA, Stine OC, Nataro JP, et al. The role of patient-to-patient transmission in the acquisition of imipenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonization in the intensive care unit. J Infect Dis. 2009;200(6):900–905. doi: 10.1086/605408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pettigrew MM, Gent JF, Kong Y, Halpin AL, Pineles L, Harris AD, et al. Gastrointestinal microbiota disruption and risk of colonization with carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in intensive care unit patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;69(4):604–613. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciy936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris AD, Jackson SS, Robinson G, Pineles L, Leekha S, Thom KA, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonization in the intensive care unit: Prevalence, risk factors, and clinical outcomes. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(5):544–548. doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kim SW, Peck KR, Jung SI, Kim YS, Kim S, Lee NY, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa as a potential cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. J Korean Med Sci. 2001;16(6):742–744. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2001.16.6.742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoff RT, Patel A, Shapiro A. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: An uncommon cause of antibiotic-associated diarrhea in an immunocompetent ambulatory adult. Case Rep Gastrointest Med. 2020;2020:6261748. doi: 10.1155/2020/6261748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chuang CH, Janapatla RP, Wang YH, Chang HJ, Huang YC, Lin TY, et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa-associated Diarrheal Diseases in Children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2017;36(12):1119–1123. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chuang CH, Wang YH, Chang HJ, Chen HL, Huang YC, Lin TY, et al. Shanghai fever: a distinct Pseudomonas aeruginosa enteric disease. Gut. 2014;63(5):736–743. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-304786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wittekamp BHJ, Oostdijk EAN, Cuthbertson BH, Brun-Buisson C, Bonten MJM. Selective decontamination of the digestive tract (SDD) in critically ill patients: a narrative review. Intensive Care Med. 2020;46(2):343–349. doi: 10.1007/s00134-019-05883-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mrazek K, Bereswill S, Heimesaat MM. Fecal microbiota transplantation decreases intestinal loads of multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa in murine carriers. Eur J Microbiol Immunol. 2019;9(1):14–22. doi: 10.1556/1886.2019.00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Forestier C, Guelon D, Cluytens V, Gillart T, Sirot J, De Champs C. Oral probiotic and prevention of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infections: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study in intensive care unit patients. Crit Care. 2008;12(3):R69. doi: 10.1186/cc6907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ortega-González M, Sánchez de Medina F, Molina-Santiago C, López-Posadas R, Pacheco D, Krell T, et al. Fructooligosacharides reduce Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 pathogenicity through distinct mechanisms. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85772. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsai YL, Lin TL, Chang CJ, Wu TR, Lai WF, Lu CC, et al. Probiotics, prebiotics and amelioration of diseases. J Biomed Sci. 2019;26(1):3. doi: 10.1186/s12929-018-0493-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Jesus Raposo MF, de Morais AM, de Morais RM. Emergent sources of prebiotics: seaweeds and microalgae. Mar Drugs. 2016;14(2):27. doi: 10.3390/md14020027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fitton HJ, Stringer DS, Park AY, Karpiniec SN. Therapies from fucoidan: new developments. Mar Drugs. 2019;17(10):571. doi: 10.3390/md17100571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Li Y, Zheng Y, Zhang Y, Yang Y, Wang P, Imre B, et al. Brown Algae Carbohydrates: structures, pharmaceutical properties, and research challenges. Mar Drugs. 2021;19(11):620. doi: 10.3390/md19110620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gotteland M, Riveros K, Gasaly N, Carcamo C, Magne F, Liabeuf G, et al. The pros and cons of using algal polysaccharides as prebiotics. Front Nutr. 2020;7:163. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2020.00163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu B, Ni F, Xiong Q, Yao Z. Marine oligosaccharides originated from seaweeds: source, preparation, structure, physiological activity and applications. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2021;61(1):60–74. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2020.1716207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shang Q, Shan X, Cai C, Hao J, Li G, Yu G. Dietary fucoidan modulates the gut microbiota in mice by increasing the abundance of: Lactobacillus and Ruminococcaceae. Food Funct. 2016;7:3224–3232. doi: 10.1039/c6fo00309e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shibata H, Iimuro M, Uchiya N, Kawamori T, Nagaoka M, Ueyama S, Hashimoto S, Yokokura T, Sugimura T, Wakabayashi K. Preventive effects of Cladosiphon fucoidan against Helicobacter pylori infection in Mongolian gerbils. Helicobacter. 2003;8(1):59–65. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5378.2003.00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.von Klitzing E, Ekmekciu I, Bereswill S, Heimesaat MM. Intestinal and systemic immune responses upon multi-drug resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa colonization of mice harboring a human gut microbiota. Front Microbiol. 2017;8:2590. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bachta KER, Allen JP, Cheung BH, Chiu CH, Hauser AR. Systemic infection facilitates transmission of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in mice. Nat Commun. 2020;11(1):543. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14363-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Filloux A. Protein secretion systems in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: An essay on diversity, evolution, and function. Front Microbiol. 2011;2:155. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jurado-Martín I, Sainz-Mejías M, McClean S. Pseudomonas aeruginosa: An audacious pathogen with an adaptable arsenal of virulence factors. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(6):3128. doi: 10.3390/ijms22063128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Juge N. Microbial adhesins to gastrointestinal mucus. Trends Microbiol. 2012;20(1):30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2011.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sommer R, Wagner S, Rox K, Varrot A, Hauck D, Wamhoff EC, et al. Glycomimetic, orally bioavailable LecB inhibitors block biofilm formation of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Am Chem Soc. 2018;140(7):2537–2545. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b11133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mercy C, Ize B, Salcedo SP, de Bentzmann S, Bigot S. Functional characterization of Pseudomonas contact dependent growth inhibition (CDI) systems. PLoS ONE. 2016;11(1):e0147435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allen JP, Ozer EA, Minasov G, Shuvalova L, Kiryukhina O, Satchell KJF, et al. A comparative genomics approach identifies contact-dependent growth inhibition as a virulence determinant. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(12):6811–6821. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1919198117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Allen JP, Hauser AR. Diversity of contact-dependent growth inhibition systems of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 2019;201(14):e00776–e818. doi: 10.1128/JB.00776-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guérin J, Bigot S, Schneider R, Buchanan SK, Jacob-Dubuisson F. Two-Partner Secretion: Combining efficiency and simplicity in the secretion of large proteins for bacteria-host and bacteria-bacteria interactions. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2017;7:148. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2017.00148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feng Y, Chien KY, Chen HL, Chiu CH. Pseudogene recoding revealed from proteomic analysis of salmonella serovars. J Proteome Res. 2012;11:1715–1719. doi: 10.1021/pr200904c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Torode TA, Marcus SE, Jam M, Tonon T, Blackburn RS, Hervé C, et al. Monoclonal antibodies directed to fucoidan preparations from brown algae. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(2):e0118366. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu AM, Gong YP, Li CC, Gilboa-Garber N. Duality of the carbohydrate-recognition system of Pseudomonas aeruginosa-II lectin (PA-IIL) FEBS Lett. 2010;584(11):2371–2375. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2010.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Heimburg-Molinaro J, Song X, Smith DF, Cummings RD. Preparation and analysis of glycan microarrays. Curr Protoc Protein Sci. 2011;64:12. doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps1210s64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yeh YM, Cheng HT, Le PH, Chen CC, Kuo CJ, Chen CL, et al. Implementation of fecal microbiota transplantation in a medical center for recurrent or refractory Clostridioides difficile infection and report of preliminary outcome. Biomed J. 2022;45(3):504–511. doi: 10.1016/j.bj.2021.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Slingerland BC, Tavakol M, McCarthy AJ, Lindsay JA, Snijders SV, Wagenaar JA, van Belkum A, Vos MC, Verbrugh HA, van Wamel WJ. Survival of Staphylococcus aureus ST398 in the human nose after artificial inoculation. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(11):e48896. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gogos A, Federle MJ. Colonization of the Murine oropharynx by Streptococcus pyogenes is governed by the Rgg2/3 Quorum Sensing System. Infect Immun. 2020;88(10):e00464–e520. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00464-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu R, Tang J, Xing C, Nan Q, Liang G, Luo J, et al. The distinguishing bacterial features from active and remission stages of ulcerative colitis revealed by paired fecal metagenomes. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:883495. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2022.883495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Owji H, Nezafat N, Negahdaripour M, Hajiebrahimi A, Ghasemi Y. A comprehensive review of signal peptides: Structure, roles, and applications. Eur J Cell Biol. 2018;97(6):422–441. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2018.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Clantin B, Hodak H, Willery E, Locht C, Jacob-Dubuisson F, Villeret V. The crystal structure of filamentous hemagglutinin secretion domain and its implications for the two-partner secretion pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(16):6194–6199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400291101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Garnett JA, Muhl D, Douse CH, Hui K, Busch A, Omisore A, et al. Structure-function analysis reveals that the Pseudomonas aeruginosa Tps4 two-partner secretion system is involved in CupB5 translocation. Protein Sci. 2015;24(5):670–687. doi: 10.1002/pro.2640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]