Abstract

SARS-CoV-2 Main protease (Mpro) is a well-known drug target against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Identification of Mpro inhibitors is vigorously pursued due to its crucial role in viral replication. The present study was aimed to identify Mpro inhibitors via repurposing of US-FDA approved drugs by STD-NMR spectroscopy. In this study, 156 drugs and natural compounds were evaluated against Mpro. Among them, 10 drugs were found to be interacting with Mpro, including diltiazem HCl (1), mefenamic acid (2), losartan potassium (3), mexiletine HCl (4), glaucine HBr (5), trimebutine maleate (6), flurbiprofen (7), amantadine HCl (8), dextromethorphan (9), and lobeline HCl (10) in STD-NMR spectroscopy. Their interactions were compared with three standards (Repurposed anti-viral drugs), dexamethasone, chloroquine phosphate, and remdesivir. Thermal stability of Mpro and dissociation constant (Kd) of six interacting drugs were also determined using DSF. RMSD plots in MD simulation studies showed the formation of stable protein-ligand complexes. They were further examined for their antiviral activity by plaque reduction assay against SARS-CoV-2, which showed 55–100% reduction in viral plaques. This study demonstrates the importance of drug repurposing against emerging and neglected diseases. This study also exhibits successful application of STD-NMR spectroscopy combined with plaque reduction assay in rapid identification of potential anti-viral agents.

Keywords: SARS-CoV-2 Main protease (Mpro), COVID-19, STD-NMR spectroscopy

1. Introduction

Coronavirus pandemic 2019 (COVID-19), first reported from Wuhan, China, in late December 2019, has spread globally in year 2020, effecting health and economy of every nation. A novel coronavirus severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) was found to be the causative agent of pneumonia like illness [1]. As of 4th January 2023, over 655 million people are infected, including 6.67 million deaths worldwide (https://covid19.who.int), and yet there is no effective targeted therapy that could treat the infection [2]. Despite the implementation of many programs, the number of infected patients and fatalities continue to increase due to emergence of new variants of SARS-CoV-2, and only a short-term protection provided by available vaccine [3]. Currently, there are very limited treatment options available for COVID-19 infection. Drug designing, development, and regulatory approval usually takes an average of 12 years. Therefore, repurposing of existing drugs against new targets is of vital importance. Repurposing of drugs save time, and permit their immediate clinical applications [4]. Currently, several medicines, such as chloroquine, hydroxychloroquine, favipiravir, ritonavir, remdesivir, lopinavir, methylprednisolone, and bevacizumab have been repurposed against COVID-19 infection [5].

SARS-CoV-2 has many validated targets for drug development. One of them is main protease (Mpro), also known as 3CLpro, which plays a crucial role in viral replication, and transcription [6], [7]. Along with papain-like protease, it processes the viral replicase polyprotein 1ab to cleave 12 nonstructural proteins, such as RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (Nsp12), and helicase (Nsp13) [8], [9]. Mpro recognizes at least 11 specific cleavage sites on viral polyprotein 1ab by amino acid sequence L-Q↓ (S, A, G) to initiate enzymatic reaction. As no human protease share the similar cleavage site specificity, developing inhibitors of Mpro will likely be safe for human host [10], [11]. Furthermore, Mpro of SARS-CoV-2 is highly conserved, and shares 96% sequence similarity with SARS-CoV of 2002 [12]. Despite some differences in amino acid sequence of Mpro from SARS-CoV-2, computational modeling reveals the similarity in receptor-binding domain to that of SARS-CoV [1]. For instance, substrate binding site of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro is formed between His41 of domain I, and Cys145 of domain II, similar to Mpro of other coronaviruses [6], [7], [13], [14]. So far, computational screening of readily available libraries of natural products and clinically used drugs is being widely carried out to predict the specific leads against Mpro [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]. Derivatives of α-ketoamides also reported as Mpro inhibitors using X-ray crystallography [9], [10], [20]. However, till to date, there is no effective drug available against SRAS-CoV-2 infection. It is, therefore, important to develop effective inhibitors of Mpro, not only against SARS-CoV-2, but also for the infections caused by other coronaviruses [7], [12].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy provides a robust tool for analyzing the protein-ligand interactions. Saturation transfer difference (STD) NMR technique is widely used to study ligand-protein interactions, as well as for epitope mapping between the ligand and biomolecular receptor [21]. In the current study, 156 clinical drugs and other compounds from our in-house molecular bank were evaluated against Mpro of SARS-CoV-2 using STD-NMR spectroscopy. Compounds showing STD effect were further evaluated for their possible antiviral activity through in-vitro plaque reduction assay against SARS-CoV-2. Finally, thermal shift assay was employed to study the changes in thermal stability of Mpro in the absence and presence of ligands (test compounds).

2. Material and method

2.1. Expression and purification of SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro)

Gene of SARS-CoV-2 Main protease (3CLpro or Mpro) was cloned into pET-25b vector containing NedI/HindIII cloning sites, and 6xHis tag on C-terminus (Genescript, USA). Plasmid was then transformed to E. coli BL21(DE3). Transformed cells were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth at 37 °C till O·D600 to ~0.6, which were then induced with 1 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Affymetrix Inc., USA), and incubated for 10 h at 16 °C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3800 RPM for 40 min at 4 °C. Cell pallet was resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate (Merck KGaA, Germany), 50 mM NaCl (VWR International BVBA, Belgium), 10 mM imidazole (Daejung Chemicals, Korea), pH 7.5). Lysis was achieved by ultra-sonication, and soluble portion was separated by centrifugation (14,600 xg for 40 min at 4 °C). Supernatant liquid was filtered through 0.45- and 0.22-μm syringe filters (Millipore, Germany). Filtrate containing soluble proteins was loaded to Ni-NTA affinity column (HisTrap, GE Healthcare, UK), and run with binding buffer till UV response became minimum. Bound protein was eluted with elution buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, 50 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole, pH 7.5), and collected fractions were analyzed through SDS-PAGE (SERVA Electrophoresis GmbH, Germany). Fractions containing the desired protein were combined, and loaded on the desalting column (Hiprep 26/10, Cytiva, USA) equilibrated with buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, 50 mM NaCl, pH 7.5) to remove imidazole. Eluent containing the protein was concentrated using 3 kDa Amicon ultra 15 membrance filter (Milipore, Germany). Buffer was exchanged with deuterated buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, 50 mM NaCl, pH 7.5, dissolved in D2O). Absorbance at 280 nm was measured using NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) to determine the protein concentration.

2.2. Library of compounds

A total of 156 drugs and compounds (106 US-FDA approved drugs, and 50 natural compounds) were grouped into 31 mixtures, each containing 5 compounds. Mixtures were prepared in deuterated phosphate buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate, 50 mM NaCl, pH 7.5). In the mixture, the final concentration of each compound was 400 μM, which were diluted from stock solution, prepared in 99.8% D2O. Remdesivir was purified by using HPLC from IVIREM lyophilized powder I.V. (Nabiqasim Pharma, Pakistan). Lyophilized powder was dissolved in 90:10 methanol: deionized water and injected on LC-908 preparative recycling HPLC system (Japan Analytical Industry Co. Ltd., Japan). Reversed phase C-18 (ODSL-80) column of 250 × 2 mm, was used for the purification using isocratic solvent system (90:10, methanol: water) with the flow rate 4 mL/min. Elution of compound was detected using UV detector λ = 254 nm.

2.3. STD-NMR experiments

All STD-NMR experiments were performed on Avance NEO 600 MHz spectrometer (Bruker, Switzerland), equipped with triple channel (TCI) cryogenically cooled probe, at 298 K. Pulse program (stddiffesgp.3, Bruker library, Germany) was used for STD-NMR experiments, with excitation sculpting for water suppression. 32 and 1024 scans were recorded for mixtures, and individual compounds, respectively. Relaxation time was set to 10 s, while saturation time was 3 s. Spin lock pulse was set to 25 ms. Selective excitation of protein resonance was achieved by Gaussian pulse of 50 ms, having the width of 200 Hz. Saturation point was set to −2.5 ppm, corresponding to protein signals (on-resonance), and − 33.3 ppm (off-resonance). STD-NMR experiments were first recorded in the absence of protein (control) to subtract any false positive ligand signals. Difference spectrum was obtained by subtracting the on-resonance spectrum from off-resonance spectrum. Net STD spectrum was acquired by taking the difference of two STD spectra. Amplification factor of each ligand peak in net STD spectrum was calculated by I0-Isat/I0 × Ligand excess, and percentage STD transfer for each peak was determined).

2.4. Fluorescence-based thermal shift assay

Real-time PCR detection system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA) was used to perform differential scanning fluorimetry (DSF) experiments. Samples were prepared in buffer (20 mM sodium phosphate buffer, 50 mM NaCl, pH 7.5), containing 2 μM protein, 20 μM ligand, and 2 μL of Sypro®Orange (1:1000; Invitrogen Life Technology, USA). Temperature increment rate was set to 0.3 °C/min, from 20 to 95 °C. Hex channel was monitored to measure the fluorescence of dye as a function of temperature. CFX Manager™ software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, USA) was used to analyze the data. Difference in thermal stability of protein was established by comparing the melting temperature (Tm, corresponding to the temperature at which half of the protein population is unfolded) of protein in the absence (control), and presence of test compounds. Dissociation constant (K d) of six compounds were determined, as described by Bhayani, J. A., and Ballicora, M. A [22]. Briefly, the change in melting temperature of protein at different ligand concentrations were plotted against log of ligand concentration. The final concentrations of ligands, used to determine K d, were from 0.1 μM to 1000 μM (0.1, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 150, 250, 500, and 1000 μM) with 2 μM of protein. The data was fitted using a non-linear regressing using GparhPad Prisim 9.5 (Dotmatics, USA).

2.5. Molecular docking studies

Molecular docking technique was employed to examine the dock pose, and types of interaction of each drug with SARS-CoV-2 Mpro. Maestro Schrödinger 10.4, and glide 6.9 module were used to perform molecular docking [23], [24]. The crystal structure of Mpro having PDB ID; 7WO3 was selected for docking studies. Protein preparation wizard in Mestro Schrödinger was used for protein preparation, and minimization. Missing hydrogen and partial charges were assigned by OPLS4e force field. Missing loop, and zero order bonds were assigned using prime module. pKa of Mpro was predicted by PROPKA. Ligand preparation was carried out by using LigPrep tool in Maestro Schröinger suite. For each ligand, suitable protonation, ionization state, and tautomeric state were assigned using Epik Prime.

2.6. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation studies

MD simulation was performed by using Schrödinger Maestro Desmond molecular dynamics suite. Each protein-ligand complex was first set into simple point charge (SPC) cubic water box with counter ions (Na+ and Cl−), and minimized by system builder tool with salt concentration of 0.15 M, using OLPS4 force field. The minimized structure was then subjected to molecular dynamics simulation of 50 ns using NPT ensemble with 10,000 frames. Recording interval was set to 100 ps of for trajectory and 1.2 ps for energy. Simulated temperature and pressure were set to 300 K and 1.013 bar, respectively. Simulation interaction diagram tool was employed for plots and figures. Change in binding pocket volume of Mpro was calculated by incorporating the binding pocket volume script on trajectory output, obtained from simulation. The binding pocket volume was calculated with the interval of 1 ns i.e. for every 10th frame of the trajectory.

2.7. Plaque reduction assay

For the evaluation of antiviral activity of test compounds, including drugs, against SARS-CoV-2, a plaque reduction assay employed [25], [26], [27]. Briefly, 105 cells/mL of Vero cells (kidney cells of a normal adult African green monkey-ATCC-CCL81) were seeded in 24-well culture plates, and incubated overnight at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Optimized dilution which provided the countable plaques of SARS-CoV-2 was mixed with the selected drugs (83 μM). The virus-drug mixtures were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. The growth medium was then removed from the 24-well plates, without disturbing the monolayer. Subsequently, the incubated virus-drug mixtures were dispensed in triplicate in 24-well plates, while virus infected cells without any drug were also added in each plate as a control. Plates were kept in the incubator for 1 h with continuous agitation for uniform adsorption. Virus-drug mixture was incubated for 1 h with agitation after every 10 mins, followed by addition of 1 mL CDMEM, supplemented with 1.5% CMC to the monolayer, plates were then further incubated at 37 °C for 5–6 days. After the incubation, cells were fixed by 10% paraformaldehyde buffer for 1 h. 0.1% Crystal violet solution was used to stain the fixed cells. Finally, plaques were counted, and the percentage reduction in virus count was recorded as follows:

2.8. Protocol of identification of treatment points

Vero cells were pre-treated with test compounds for 1 h, and then infected with SARS-CoV-2 for 1 h to allow infection. Compound-virus mixture was then removed, and the cells were washed with PBS. Subsequently, the cells were incubated in the presence of fresh medium containing the 83.0 and 41.5 μM concentrations of the test compounds, and the cells and supernatant were collected at 48 hpi.

For the prophylactic conditions, Vero cells were pre-treated with the test compound in infection medium for 1 h, and the viral culture was dispensed for further 2 h in order to allow the infection. Subsequently, the cells were washed twice with PBS, and incubated for 48 h in the presence of the test compounds in fresh infection medium. For the entry condition, the Vero cells were treated with the test compounds for the infection period (2 h), followed by removal of the compounds-virus mixture, and washing of the cells. Subsequently, the cells were incubated in infection medium without the test compounds for 48 h. For the therapeutic condition (post-entry), viral infection without the test compounds for 2 h, after that the viral culture was taken out from the plates, and the cells were washed. After washing, test compounds in fresh infection medium were added to the infected monolayer of Vero cells for 48 h [28].

2.9. Statistical analysis

Three replicates were used in each experiment, unless otherwise stated. All results were presented as means standard deviations. A one-way ANOVA was used to analyze statistical differences at a P-value 0.05 (95 % confidence interval) in conjugation with Šidák test using GraphPad prism version 9.4.1 (Dotmatics, USA).

3. Results and discussion

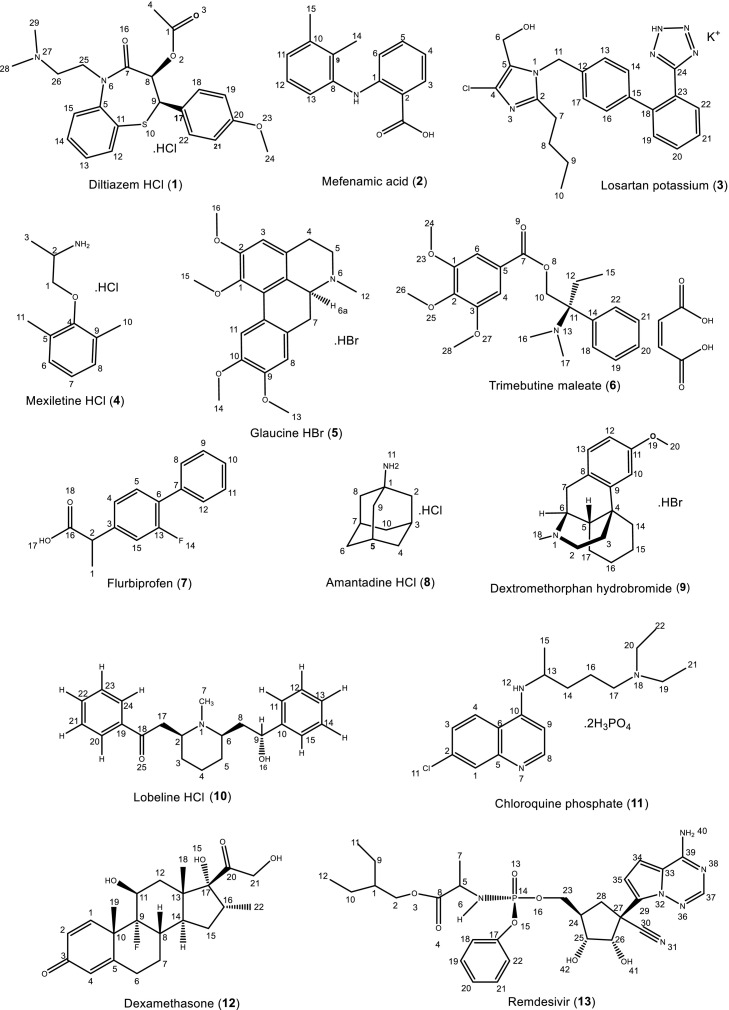

Drug repurposing is a time efficient, and cost-effective approach to develop targeted drug leads against emerging, and preventing diseases [29], [30]. Main protease (Mpro) of SARS-CoV-2 is a vital target, due to its role in viral replication. A sum of 156 compounds from in-house molecular bank, including 106 clinical drugs, and 50 natural compounds, were evaluated against SARS-CoV-2 main protease (Mpro) by using STD-NMR spectroscopy (Table S1). Out of them, 10 drugs have shown strong interactions with the Mpro in-silico, and in-vitro (Fig. 1 ). The selected compounds were then evaluated for their antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2, using plaque reduction assay. The active compounds were further analyzed for thermal stability in the presence, and absence of Mpro protein. Molecular docking studies of active compounds were also performed to set insight into the types of interactions between Mpro, and active compounds.

Fig. 1.

Clinical drugs that showed interactions with Mpro from SARS-CoV-2 using STD-NMR spectroscopy.

3.1. Studies on protein-ligand interaction using STD-NMR Spectroscopy

STD-NMR spectroscopy is a robust method to identify weak to moderate interactions between a protein receptor, and small molecule ligand, provided the large excess of ligand concentrations, and K d's < μM [21]. Rf saturation applied on protein resonance spreads over entire protein structure through spin-spin relaxation, and transfer to protons of ligand bound with the protein. The intensity in the STD-NMR experiment thus shows the proximity of ligand protons with the protein. Closer the ligand protons to the binding residues of protein, higher will be the intensity of those ligand protons. The percentage of saturation transfer of different protons of ligand was calculated relative to the protons with largest STD integral value which was set to an arbitrary value of 100 %.

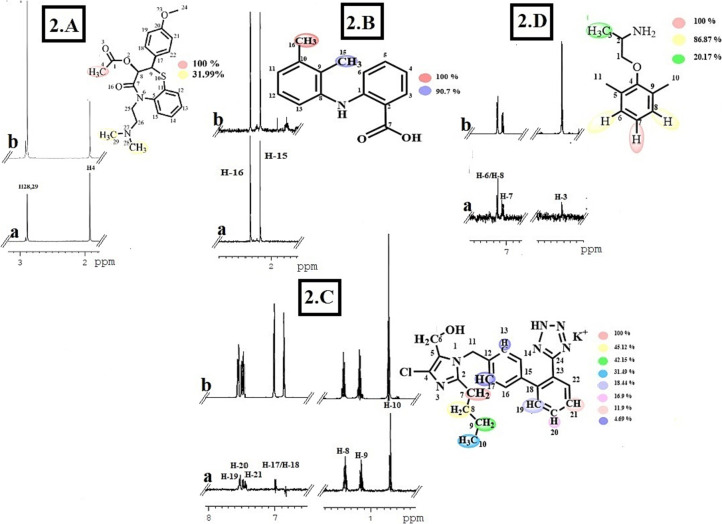

Diltiazem hydrochloride (C22H27ClN2O4S) (1) belongs to calcium-channel blocker class of drugs. It is widely used to treat high blood pressures, and angina pain [31]. In compound 1, C-4 methyl protons showed the closest proximity to protein with largest STD integral value, assign to receive 100% saturation. H3–28 and H3–29 are normalized against H3–4. Relative degree of saturation received by H3–28/H3–29 was calculated as 31.99%, relative to H3–4 (Fig. 2 .A).

Fig. 2.

STD-NMR analysis of FDA-approved drugs. 2.A) STD-NMR spectrum of compound 1. (a) STD-NMR difference spectrum recorded in the presence of 2 μM Mpro protein. (b) 1H NMR reference spectrum of compound 1. 2.B) STD-NMR spectrum of compound 2. (a) STD-NMR difference spectrum recorded in the presence of 2 μM Mpro protein. (b) 1H NMR reference spectrum of compound 2. 2.C) STD-NMR spectrum of compound 3. a) STD-NMR difference spectrum recorded in the presence of 2 μM Mpro protein. b) 1H NMR reference spectrum of compound 3. 2.D) STD-NMR spectrum of compound 4. a) STD difference spectrum recorded in the presence of 2 μM Mpro protein. b) 1H NMR reference spectrum of compound 4. All protons are indicated with a colour code.

Mefenamic acid (C15H15NO2) (2), a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), is a common analgesic for mild to moderate pain [32]. In compound 2, both the methyl protons (H3–16 and H3–15) showed strong interactions with Mpro. H3–16 showed the largest STD integral value, and thus set to the value of 100 %. H3–15 is normalized against H3–16. H3–15 received 90.7 % saturation, relevant to H3–16 (Fig. 2.B).

Losartan potassium (C22H23ClKN6O) (3) is an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), used for the treatment of high blood pressure [33]. In compound 3, H2–7 showed largest STD integral value (100 %) and all STD interactions were normalized against H2–7. H2–8, H2–9, and H3–10 received 45.22%, 42.15%, and 31.49% saturation, respectively. Aromatic protons, H-17, H-13, H-19, H-20, and H-21, received less saturation between 18.44 and 4.69% indicating them to be located farther from interacting residues of Mpro protein (Fig. 2.C).

Compound 4 (Mexiletine hydrochloride) (C11H18ClNO) is an anti-arrhythmic drug, used for the treatment of persistent ventricular tachycardia [34]. In compound 4, aromatic H-7 showed the largest STD integral value (100%). H-6/H-8, and H-3 were thus normalized against H-7. H-6/H-8 received 86.87%, while methyl H-3 received lowest saturation of 20% may be due to their longer distances from interacting residues of Mpro (Fig. 2.D).

Compound 5 (Glaucine hydrobromide) (C21H26BrNO4) is a PDE4 inhibitor and calcium channel blocker. It is used as an anti-tussive in many countries [35]. In compound 5, H-8 showed the highest STD integral value (100%). H-13 received 61.50% saturation. Aromatic H-9 and H-11 received 50.43 and 47.16% saturation, while H-16, and H-15 received 47.16 and 44.39%, respectively. H3–14 received the lowest saturation of 38.02 % (Fig. S1).

Compound 6 (Trimebutine maleate) (C26H33NO9) is a spasmolytic drug, used for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome [36]. In compound 6, H-30 showed the highest STD integral value (100%), while H-29 received 55% saturation relative to H-30. Methyl H3–15 and H3–16 received 36 % relative saturation. Methoxy protons H3–24, H3–26, and H3–28 received 7–11% relative saturation (Fig. S2).

Compound 7 (Flurbiprofen) (C15H13FO2) is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), used for the treatment of swelling, pain, and joint stiffness from arthritis [37]. In compound 7, methyl H-1 set to received 100% saturation as it showed the highest integral value. H-2 received 44.10% saturation, suggesting that it is located away from interacting residues of Mpro (Fig. S3).

Compound 8 (Amantadine hydrochloride) (C10H18ClN) is used in suppressing the symptoms of Parkinson's disease [38]. In compound 8, H2–2, H2–8, and H2–9 showed the highest STD integral value (100%). H-3, H-5, and H-7 received 78% saturation, while axial and equatorial protons H2–4 H2–6, and H2–10 received 59–64% saturation (Fig. S4).

Compound 9 (Dextromethorphan) (C18H28BrNO2) is an antitussive, commonly used as cold and cough suppressant [39]. In compound 9, 2H-16 have received the highest saturation. H-6 received 95%, while 2H-17 received 58%–83% saturation, respectively. Methyl 3H-18 and 3H-20 received 30.8, and 12.8% saturation, and aromatic H-10 received 70.6% saturation (Fig. S5).

Compound 10 (Lobeline HCl) (C22H28ClNO2) is a nicotine acetylcholine receptor agonist, used as anti-depressant, and for pharmacotherapy of smoke and drug addiction [40]. In compound 10, H-9 showed the highest STD integral value (100%). Methyl H3–7 received 30.81% saturation, while H-11and H-15 received 11.0% saturation (Fig. S6).

Compound 11 (Chloroquine phosphate) (C18H32ClN3O8P2) is an anti-malarial and amebicide agent widely used in the prevention, and treatment of malaria [41]. In compound 11, H-14/H-16 showed the highest STD integral value (100%). H-19/H-20 received 50.14% saturation suggesting the longer distance to interacting protein residues, while H-15 and H-21/H-22 received the lowest saturation of 28.47 and 16.68%, respectively (Fig. S7).

Compound 12 (Dexamethasone) (C22H29FO5) is a corticosteroid, used to suppress the immune response to reduce allergic symptoms [42]. In compound 12, Ha-6 showed the highest STD integral value (100%). All other interactions were normalized according to Ha-6. Hb-6 received 54.8% saturation. Ha-7 and Hb-7 received 58.8 and 18.77% saturation, respectively. Methyl H3–19 received 4.13% saturation (Fig. S8).

Compound 13 (Remdesivir) (C27H35N6O8P) is a broad-spectrum anti-viral drug, used against hepatitis C and Ebola viral infections [43]. In compound 13, the most downfield H-37 showed the highest STD integral value (100%). Pentacyclic aromatic H-35 received 80.79%, while H-34 received 78.86% saturation. H-19/H-21, H-18/H-22, and H-20 received 69.88, 64.95, and 55.82% saturation, respectively (Fig. S9).

3.2. Fluorescence-based thermal shift assay

Melting temperature (Tm) of protein is the temperature at which half of the protein is unfolded. It is used to measure the thermal profile of a protein. Change in melting temperature (Tm) of protein corresponds to the interactions of protein with ligand molecule [44]. Melting temperature (Tm) of Mpro of SARS-CoV-2, determined by DSF, was 53.5 ± 1 °C. The addition of selected compounds altered the melting temperature (Tm) of Mpro. Majority of the test compounds showed a positive modulation of Tm. Compounds 2, 4, 8, and 12 positively modulated the Tm by +2.9 °C, indicating strong interactions between Mpro and test compounds, while only compounds 5, and 10 modulated the Tm by −1 °C, showing that these compounds are apparently destabilizing the Mpro, hence the thermal stability of Mpro was reduced (Fig. 3a). The reduction in melting temperature of Mpro (Tm), caused by Glaucine hydrobromide (5) and lobeline hydrochloride (10), may be the result of conformational changes in protein structure or due to the interactions of these molecules with some unfolded protein present [45], [46].

Fig. 3.

Graphical representation of variations in Tm values of Mprovia DSF: a) Tm value for Mpro at 2 μM in red. Blue bars represents the change in Tm of Mpro upon addition of individual compound. b) The solid black line represents the variation in Tm with increasing concentration of compound 2. The dashed red line represents the linear extrapolation of the curve at higher concentrations and the blue dashed line represent Tm0,i.e. the Tm of protein in the absence of ligand. These two lines intercept at the log of the Kd value.

Dissociation constant (K d) of compounds 1, 2, 3, 4, 7, and 11 (Table 1 ) were determined by plotting Tm at increasing ligand concentrations versus log of ligand concentration. Addition of ligand stabilized the protein resulting in an increase of melting temperature which is significant at higher concentrations of ligand (Fig. 3b).

Table 1.

Dissociation constant (Kd) determined via fluorescence-based thermal shift assay.

| Compound | Dissociation constant (Kd) |

|---|---|

| Diltiazem hydrochloride (1) | ≈ 44 ± 8 μM |

| Mefenamic acid (2) | ≈ 15 ± 3 μM |

| Losartan potassium (3) | ≈ 64 ± 4 μM |

| Mexiletine hydrochloride (4) | ≈ 21 ± 5 μM |

| Flurbiprofen (7) | ≈ 66 ± 3 μM |

| Chloroquine phosphate (11) | ≈ 49 ± 9 μM |

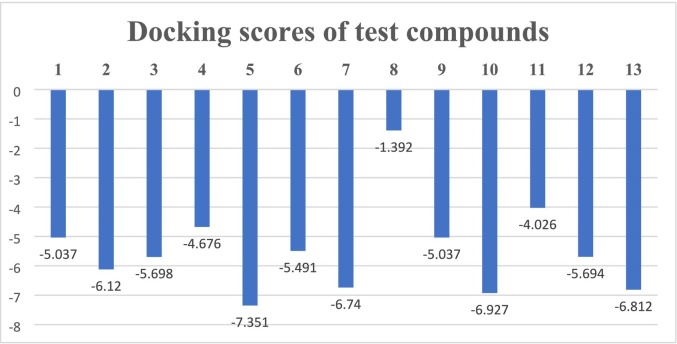

3.3. Molecular docking studies

To predict the interactions of test compounds with Mpro, molecular docking studies were carried out. Substrate binding pocket of Mpro of SARS-CoV-2 is similar to other coronaviruses. It is comprised of His41 of domain I, and Cys145 of domain II. A predocked His41 specific model of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro (PDB ID; 7WO3) was selected for docking of drugs.

Diltiazem hydrochloride (C22H27ClN2O4S) (1) showed π-cationic interaction with His41, and hydrogen bonding with His163 (Fig. 4 ).

Fig. 4.

Diltiazem hydrochloride (1) docked pose with Mpro of SARS-CoV-2: a) 2D Representation of ligand-protein profile. b) 3D Representation of ligand-protein interactions in dotted lines, indicating hydrogen bond (black), and π-cationic interactions (purple). c) Solid surface representation of protein ligand complex.

Mefenamic acid (C15H15NO2) (2) showed strong aromatic hydrogen bonding with Leu141, π- π stacking with His163, and hydrogen bonding with Gly143 (Fig. S10). Losartan potassium (C22H23ClKN6O) (3) showed π- π stacking with His41, aromatic hydrogen bonding with Asp187, and hydrogen bonding with Arg188 of Mpro (Fig. S11). Mexiletine hydrochloride (C11H18ClNO) (4) showed π-π stacking with His41, and hydrogen bonding with Glu166 of Mpro (Fig. S12). Glaucine hydrobromide (C21H26BrNO4) (5) showed π- cation interaction with His41, and hydrogen bonding with Gly143 (Fig. S13). Trimebutine maleate (C26H33NO9) (6) was interacting with Mpro via aromatic hydrogen bondings with Leu141, Cys145, GLy143, and Glu166 (Fig. S14). Flurbiprofen (C15H13FO2) (7) showed π- π stacking with His41, aromatic hydrogen bonding with Asp187, and hydrogen bondings with Cys145 and Gly43 (Fig. S15). Amantadine hydrochloride (C10H18ClN) (8) interacting via hydrogen bonding with Gln189 (Fig. S16). Dextromethorphan hydrobromide (C18H28BrNO2) (9) showed π-cationic interaction with His41 (Fig. S17). Lobeline hydrochloride (C22H28ClNO2) (10) showed π-cationic interactions with His41, aromatic hydrogen bonding with Thr26 and Thr190, and hydrogen bonding with Glu166 (Fig. S18). Chloroquine phosphate (C18H32ClN3O8P2) (11) showed π-cationic interaction with His41 (Fig. S19). Dexamethasone (C22H29FO5) (12) showed aromatic hydrogen bonding with Glu 166, and Thr 26 (Fig. S20), whereas remdesivir (C27H35N6O8P) (13) showed hydrogen bondings with Cys145 and Gly143. It is also interacting via aromatic hydrogen bonding with Glu166 (Fig. S21). Docking scores of clinical drugs against SARS-CoV-2 Mpro are presented in Fig. 5 .

Fig. 5.

Docking scores of test compounds against SARS-Cov-2 Mpro.

3.4. Molecular dynamics simulation studies

MD simulation were performed to assess the stability of protein-ligand complexes. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations typically compute the atom movements with time by integrating the Newton's classical equation of motion [47]. The average change in displacement of a particular set of atoms for a given frame, relative to a reference frame, was calculated using the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD).

The Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) plot of Losartan potassium (3)-Mpro complex showed the formation of stable complex (Fig. 6a). Protein RMSD along left Y-axis and ligand RMSD along right Y-axis had insignificant fluctuations (< 3 Å) of approximately 1.1 Å and 0.2 Å respectively, indicating no conformational changes in protein and ligand structures occurred during the formation of protein-ligand complex. Remdesivir (13) and dextromethorphan (9) showed an insignificant increase in RMSD till 45 ns which became consistent and remained align with the protein backbone till the end of simulation i-e 100 ns, inferring the formation of stable protein-ligand complexes (Fig. 6b, c). Amantadine hydrochloride (8) showed an increase of 2 Å in RMSD from initial frame till 20 ns which remain consistent and overlapped with protein backbone till the end, indicating the formation of stable amantadine hydrochloride (8)-Mpro complex (Fig. 6d). The minimum and maximum binding site volume, calculated for compounds 3, 13, 9, and 8, were 91–317 Å3, 41–325 Å3, 63–440 Å3, and 45–274 Å3, respectively (Fig. 7 ).

Fig. 6.

RMSD plot of test compounds-Mpro complexes, obtained from 100 ns molecular dynamics simulation: a) Losartan potassium (3)-SARS-CoV-2-Mpro complex. b) Remdesivir (13)-SARS-CoV-2-Mpro complex. c) Dextromethorphan (9)-SARS-CoV-2-Mpro complex. d) Amantadine hydrochloride (8)-SARS-CoV-2-Mpro complex.

Fig. 7.

3D Representation of variation in protein binding site volume during 100 ns MD simulation of amantadine hydrochloride (8)-SARS-CoV-2-Mpro complex. Blue spheres represent the minimum (45 Å3), while dark grey represent the maximum (274 Å3) volume calculated.

The RMSD plot of glaucine hydrobromide (5)-Mpro complex showed a significant change of 3.6 Å in protein RMSD along left Y-axis inferring a conformational change in protein structure in order to form a stable complex. The RMSD plot of lobeline hydrochloride (10)-Mpro complex showed that the complex formed is not stable as the ligand RMSD remained detached from protein backbone. The simulation results of compounds 5, and 10 also explicate the reduction in melting temperature of Mpro, observed in thermal shift assay (Fig. S22).

3.5. Coherence analysis between STD-NMR and molecular docking

STD-NMR analysis and molecular docking studies of test compounds showed remarkable coherence in the results. H3–28 and H3–29 of diltiazem hydrochloride (1) are directly bonded to N-27, which showed interaction with His41 in molecular docking. H-19, H-20, and H-21 of losartan potassium (3) are interacting via π-π stacking with His41 in molecular docking. In mexiletine hydrochloride (4), H-6/H-8, and H-7 showed π- π stacking with His41, while H3–3 is adjacent to the amide which showed H-boning interaction with Glu166. H3–14 of glaucine hydrobromide (5) showed hydrogen bonding with Gly143. H3–26 of trimebutine meleate (6) showed H-bonding interaction with Glu166. H3–18 of dextromethorphan (9) is adjacent to N-1, which is interacting with His41. H-9, H-11, and H-15 of lobeline hydrochloride (10) is near to OH interacting with Glu166, while H3–7 is interacting with Gln1889, and bonded to N-1 interacting with Cys145. In chloroquine phosphate (11), H2–19 and H2–20 ae directly bonded to N-18, which is interacting with His41. H-18 to H-22 of remdesivir (13) are close to the carbonyl which is interacting with Gly143 and Cys145.

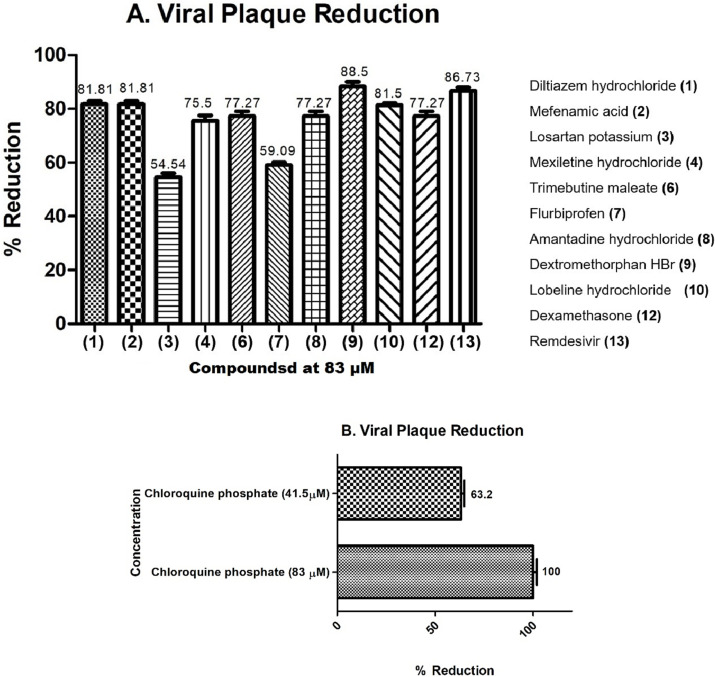

3.6. Evaluation of antiviral activity of selected compounds through plaque reduction assay

To determine anti-SARS-CoV-2 activity, STD-active test compounds were subjected to plaque reduction assay which is a gold standard assay for measuring the viral infectivity. Plaque assay measures the infectivity of complete virions, released from the host cells. Most promising compounds (C1– C13) were subsequently evaluated in a BSL3 facility for their viral inhibitory potential. Pre-incubation significantly inhibited the plaque formation (death zones) of SARS-CoV-2 at the concentration of 83 μM, indicating suppression of viral infection in Vero cells.

Two protease inhibitors, lopinavir and ritonavir, reported for their anti-HIV/ AIDS activity, also demonstrated in vitro anti-SARS coronavirus activity [48], [49]. Moreover, ivermectin, an anti-parasitic drug, was also observed to have anti-viral properties [50], [51]. In vitro study showed the effects of ivermectin against SARS-CoV-2, including the inhibition of the viral replication [52].

Compounds 3, and 7 moderately inhibited the growth of SARS-CoV-2 with 54.54% and 59.09% reduction, respectively. In contrast, compound 11 strongly protected Vero cells from the viral infection (Fig. 8A) in a dose dependent manner from 100% viral plaque reduction to 63.2% at the concentrations of 83 and 41.5 μM, respectively (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Plaque reduction assay for the test compounds. (A): Infected cells were treated with individual compounds for 1 h to evaluate the antiviral activity. Lesser number of death zones were observed in case of compounds, dilitazem hydrochloride (1), mefenamic acid (2), dextromethorphan (9), and lobeline HCl (10), chloroquine phosphate (11), dexamethasone (12), remdesivir (13). (B): chloroquine phosphate (11) was found to be highly active with 100 % plaque reduction at the concentrations of 83 μM, and 63.2 % at 45.1 μM.

Compounds 1, 2, 9, 10, and 13 have also significantly minimized the plaque formation by SARS-CoV-2 in Vero cells within the range of 81–88%. Furthermore, compounds 6, 8, and 12 showed 77.27% reduction, Moreover, compounds 4 demonstrated a low plaque counts i.e. 75.5%, which indicate their potential to reduce the PFU of SARS-CoV-2. Plaque reduction assay revealed that most of the Mpro inhibitors have potently inhibited the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in-vitro. Furthermore, some STD-inactive compounds were also checked for their potential against SARS-CoV-2, and observed as less effective with percent reduction lower than 40% (Fig. S23). Although, STD-active compounds showed higher reduction in viral plaques, it is possible that these compounds may also have interaction with multiple proteins of SARS-CoV-2, and not just with Mpro.

3.7. Results of treatment points

The host receptor for the binding of SARS-CoV-2 is ACE2 (Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2) receptor [53]. During the pandemic, drug repurposing was extensively deployed for the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Many small molecule inhibitors were reported which target host proteases and thus inhibit the entry of SARS-CoV-2, including TMPRSS2 inhibitors, camostat mesylate, nafamostat mesylate, and bromhexine hydrochloride, cathepsin L Inhibitors E-64d16, K11777, and SID26681509, and furin inhibitor naphthofluorescein [54], [55], [56], [57], [58], [59].

To determine which steps of the virus life-cycle is inhibited by the test compounds, they were evaluated at the different time points of treatment: prophylactic (1 h prior to infection and maintenance for 48 h), entry (0 h of infection and maintenance for 2 h), and therapeutic (2 h following infection and maintenance for 48 h).

Log 10 of fold change in viral reduction was evaluated. At the concentration of 83 and 42.5 μM, most of the tested dugs reduced the SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA by 100–54%.

Moderate effect of compounds 1, and 9–11 was observed at prophylactic and entry points, while significant effect was observed in therapeutic treatment point (log 10-fold change = 2.02, 2.11, 2.26 and 2.12 respectively) at 83 μM. Among them, compounds 1 and 10 were found to be significant at the lower concentration of 42.5 μM (log 10-fold change = 2.00 and 1.75, respectively). Compound 2 exerted its moderate effect at entry point (log 10-fold change 1.56 at 83 μM), similar effects were observed in prophylactic point.

Most of the promising effects of compounds were observed in therapeutic point. Chloroquine phosphate (11), remdesivir (13), and DMSO were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Results suggested that both of these drugs exert their effect at therapeutic point (Fig. 9 ), while no effect was observed with DMSO in viral reduction. Treatment with lobeline HCl (10), chloroquine phosphate (11), and dexamethasone (12) evidently reduced the viral plaque formation and viral RNA levels, confirmed the effective inhibition of infection. All the tested drugs were capable of causing a significant reduction of SARS-CoV-2 in Vero cells in certain points, in terms of both RNA production and infectious virus production. These data show that these US-FDA approved drugs are able to inhibit in vitro propagation of SARS-CoV-2.

Fig. 9.

Effect of compounds on different treatment points. Prophylactic, entry and therapeutic treatment points were evaluated. Log fold change for drug-treated cells relative to infection and vehicle controls were calculated. Log fold change was calculated in each independent experiment, and the mean fold change is plotted, with error bars displaying standard deviations. Asterisk indicates the significance between different groups.

The effects of some compounds in plaque reduction can probably be due to the interactions of test compounds with proteins present on the surface of SARS-CoV-2. As a result, they prevent the virus attachment to Vero cells.

4. Conclusion

In this study, potential interactions of US-FDA approved drugs, and other bioactive compounds with SARS-CoV-2 Main protease (Mpro) were studied by employing STD-NMR. 156 Compounds were evaluated against SARS-CoV 2 Main protease (Mpro), and 10 drugs were found to be interacting with the purified protein. These compounds were further evaluated via plaque reduction assay, which confirmed the significant reduction in viral plaque. Some compounds exhibited their effects on the entry and post entry treatment points. DSF analysis also showed the modulation in thermal stability of protein in the presence of these compounds. Molecular docking, and molecular dynamics showed a significant coherence with STD-NMR results, and stability of protein-ligand complex, respectively. These investigations collectively indicate that these repurposed drugs can inhibit SARS-CoV-2 efficiently, thereby making them potential leads for further research towards the treatment of coronavirus disease.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

ATW and MIC were involved in conceptualization, investigation, supervision, analysis, reviewing, and editing of manuscript. AMK and AU carried out the expression, purification of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro, and molecular docking studies. AMK performed the STD-NMR, and DSF experiments. SF carried out viral plaque reduction, and treatment point assays. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

Authors are thankful to the Searle Company Ltd. Pakistan, for providing financial assistance through a research project.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.123540.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Lu R., Zhao X., Li J., Niu P., Yang B., Wu H., Wang W., Song H., Huang B., Zhu N., Bi Y. Genomic characterization and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395(10224):565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jang W.D., Jeon S., Kim S., Lee S.Y. Drugs repurposed for COVID-19 by virtual screening of 6,218 drugs and cell-based assay. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2021;118(30) doi: 10.1073/pnas.2024302118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luo L., Qiu Q., Huang F., Liu K., Lan Y., Li X., Huang Y., Cui L., Luo H. Drug repurposing against coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a review. J. Pharm. Anal. 2021;11(6):683–690. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2021.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pande M., Kundu D., Srivastava R. Drugs repurposing against SARS-CoV2 and the new variant B. 1.1. 7 (alpha strain) targeting the spike protein: molecular docking and simulation studies. Heliyon. 2021;7(8) doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rosa S.G.V., Santos W.C. Clinical trials on drug repositioning for COVID-19 treatment. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica. 2020;44 doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2020.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Anand K., Palm G.J., Mesters J.R., Siddell S.G., Ziebuhr J., Hilgenfeld R. Structure of coronavirus main proteinase reveals combination of a chymotrypsin fold with an extra α-helical domain. EMBO J. 2002;21:3213–3224. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang H., Yang M., Ding Y., Liu Y., Lou Z., Zhou Z., Sun L., Mo L., Ye S., Pang H., Gao G.F. The crystal structures of severe acute respiratory syndrome virus main protease and its complex with an inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2003;100(23):13190–13195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1835675100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qiao J., Li Y.S., Zeng R., Liu F.L., Luo R.H., Huang C., Wang Y.F., Zhang J., Quan B., Shen C., Mao X. SARS-CoV-2 mpro inhibitors with antiviral activity in a transgenic mouse model. Science. 2021;371(6536):1374–1378. doi: 10.1126/science.abf1611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rut W., Groborz K., Zhang L., Sun X., Zmudzinski M., Pawlik B., Wang X., Jochmans D., Neyts J., Młynarski W., Hilgenfeld R. SARS-CoV-2 M pro inhibitors and activity-based probes for patient-sample imaging. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2021;17(2):222–228. doi: 10.1038/s41589-020-00689-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang L., Lin D., Sun X., Curth U., Drosten C., Sauerhering L., Becker S., Rox K., Hilgenfeld R. Crystal structure of SARS-CoV-2 main protease provides a basis for design of improved α-ketoamide inhibitors. Science. 2020;368(6489):409–412. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Abian O., Ortega-Alarcon D., Jimenez-Alesanco A., Ceballos-Laita L., Vega S., Reyburn H.T., Rizzuti B., Velazquez-Campoy A. Structural stability of SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro and identification of quercetin as an inhibitor by experimental screening. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020;164:1693–1703. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.07.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Helmy Y.A., Fawzy M., Elaswad A., Sobieh A., Kenney S.P., Shehata A.A. The COVID-19 pandemic: a comprehensive review of taxonomy, genetics, epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and control. J. Clin. Med. 2020;9(4):1225. doi: 10.3390/jcm9041225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Xue X., Yu H., Yang H., Xue F., Wu Z., Shen W., Li J., Zhou Z., Ding Y., Zhao Q., Zhang X.C. Structures of two coronavirus main proteases: implications for substrate binding and antiviral drug design. J. Virol. 2008;82(5):2515–2527. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02114-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ren Z., Yan L., Zhang N., Guo Y., Yang C., Lou Z., Rao Z. The newly emerged SARS-like coronavirus HCoV-EMC also has an"Achilles' heel": current effective inhibitor targeting a 3C-like protease. Protein Cell. 2013;4(4):248. doi: 10.1007/s13238-013-2841-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jin Z., Du X., Xu Y., Deng Y., Liu M., Zhao Y., Zhang B., Li X., Zhang L., Peng C., Duan Y. Structure of M pro from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature. 2020;582(7811):289–293. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bharadwaj S., Azhar E.I., Kamal M.A., Bajrai L.H., Dubey A., Jha K., Yadava U., Kang S.G., Dwivedi V.D. SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors: identification of anti-SARS-CoV-2 Mpro compounds from FDA approved drugs. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020:1–16. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1842807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gurung A.B., Ali M.A., Lee J., Farah M.A., Al-Anazi K.M. Unravelling lead antiviral phytochemicals for the inhibition of SARS-CoV-2 Mpro enzyme through in-silico approach. Life Sci. 2020;255 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ibrahim M.A., Abdeljawaad K.A., Abdelrahman A.H., Hegazy M.E.F. Natural-like products as potential SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitors: in-silico drug discovery. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020:1–13. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1790037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan S.A., Zia K., Ashraf S., Uddin R., Ul-Haq Z. Identification of chymotrypsin-like protease inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2 via integrated computational approach. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021;39(7):2607–2616. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1751298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang L., Lin D., Kusov Y., Nian Y., Ma Q., Wang J., Von Brunn A., Leyssen P., Lanko K., Neyts J., De Wilde A. α-ketoamides as broad-spectrum inhibitors of coronavirus and enterovirus replication: structure-based design, synthesis, and activity assessment. J. Med. Chem. 2020;63(9):4562–4578. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.9b01828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mayer M., Meyer B. Characterization of ligand binding by saturation transfer difference NMR spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999;38(12):1784–1788. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990614)38:12<1784::AID-ANIE1784>3.0.CO;2-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhayani J.A., Ballicora M.A. Determination of dissociation constants of protein ligands by thermal shift assay. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022;590:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Friesner R.A., Murphy R.B., Repasky M.P., Frye L.L., Greenwood J.R., Halgren T.A., Sanschagrin P.C., Mainz D.T. Extra precision glide: docking and scoring incorporating a model of hydrophobic enclosure for protein−ligand complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49(21):6177–6196. doi: 10.1021/jm051256o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Halgren T.A., Murphy R.B., Friesner R.A., Beard H.S., Frye L.L., Pollard W.T., Banks J.L. Glide: a new approach for rapid, accurate docking and scoring. 2.Enrichment factors in database screening. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47(7):1750–1759. doi: 10.1021/jm030644s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Roshdy W.H., Rashed H.A., Kandeil A., Mostafa A., Moatasim Y., Kutkat O., Abo Shama N.M., Gomaa M.R., El-Sayed I.H., El Guindy N.M., Naguib A. EGYVIR: an immunomodulatory herbal extract with potent antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2. PLoS One. 2020;15(11) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayden F.G., Cote K.M., Douglas R.G., Jr. Plaque inhibition assay for drug susceptibility testing of influenza viruses. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1980;17(5):865–870. doi: 10.1128/aac.17.5.865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jin Z., Du X., Xu Y., Deng Y., Liu M., Zhao Y., Zhang B., Li X., Zhang L., Peng C., Duan Y., Yu J., Wang L., Yang K., Liu F., Jiang R., Yang X., You T., Liu X., Yang X., Bai F., Liu H., Liu X., Guddat L.W., Xu W., XiaoG Qin C., Shi Zhengli, Jiang H., Rao Z., Yang H. Structure of Mpro from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature. 2020;582(7811):289–293. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cho J., Lee Y.J., Kim J.H., Kim S.S., Choi B.S., Choi J.H. Antiviral activity of digoxin and ouabain against SARS-CoV-2 infection and its implication for COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 2020;10(1):1–8. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-72879-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pushpakom S., Iorio F., Eyers P.A., Escott K.J., Hopper S., Wells A., Doig A., Guilliams T., Latimer J., McNamee C., Norris A. Drug repurposing: progress, challenges and recommendations. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2019;18(1):41–58. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2018.168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kingsmore K.M., Grammer A.C., Lipsky P.E. Drug repurposing to improve treatment of rheumatic autoimmune inflammatory diseases. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2020;16:32–52. doi: 10.1038/s41584-019-0337-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heel R.C., Brogden R.N., Speight T.M., Avery G.S. Buprenorphine: a review of its pharmacological properties and therapeutic efficacy. Drugs. 1979;17(2):81–110. doi: 10.2165/00003495-197917020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cimolai N. The potential and promise of mefenamic acid. Expert. Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013;6(3):289–305. doi: 10.1586/ecp.13.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abdel-Fattah L., Abdel-Aziz L., Gaied M. Enhanced spectrophotometric determination of losartan potassium based on its physicochemical interaction with cationic surfactant. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015;136:178–184. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Andrews J.L., Nilsson Lill S.O., Freitag-Pohl S., Apperley D.C., Yufit D.S., Batsanov A.S., Mulvee M.T., Edkins K., McCabe J.F., Berry D.J., Probert M.R. Derisking the polymorph landscape: the complex polymorphism of mexiletine hydrochloride. Cryst.Growth Des. 2021;21(12):7150–7167. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ivorra M.D., Lugnier C., Schott C., Catret M., Noguera M.A., Anselmi E., D' Ocon P. Multiple actions of glaucine on cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases, α1-adrenoceptor and benzothiazepine binding site at the calcium channel. Br. J. Pharmacol. 1992;106(2):387–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1992.tb14345.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Salvioli B. Trimebutine: a state-of-the-art review. Minerva Gastroenterol. Dietol. 2019;65(3):229–238. doi: 10.23736/S1121-421X.19.02567-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oktay A.N., Karakucuk A., Ilbasmis-Tamer S., Celebi N. Dermal flurbiprofen nanosuspensions: optimization with design of experiment approach and in vitro evaluation. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2018;122:254–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2018.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oertel W., Eggert K., Pahwa R., Tanner C.M., Hauser R.A., Trenkwalder C., Ehret R., Azulay J.P., Isaacson S., Felt L., Stempien M.J. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of ADS-5102 (amantadine) extended-release capsules for levodopa-induced dyskinesia in Parkinson's disease (EASE LID 3) Mov. Disord. 2017;32(12):1701–1709. doi: 10.1002/mds.27131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Matthys H., Bleicher B., Bleicher U. Dextromethorphan and codeine: objective assessment of antitussive activity in patients with chronic cough. J. Int. Med. Res. 1983;11(2):92–100. doi: 10.1177/030006058301100206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Arias H.R., Feuerbach D., Ortells M. Functional and structural interaction of (−)-lobeline with human α4β2 and α4β4 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2015;64:15–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2015.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gao J., Tian Z., Yang X. Breakthrough: chloroquine phosphate has shown apparent efficacy in treatment of COVID-19 associated pneumonia in clinical studies. Biosci.Trends. 2020;14:72–73. doi: 10.5582/bst.2020.01047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Giles A.J., Hutchinson M.K.N., Sonnemann H.M., Jung J., Fecci P.E., Ratnam N.M., Zhang W., Song H., Bailey R., Davis D., Reid C.M. Dexamethasone-induced immunosuppression: mechanisms and implications for immunotherapy. J. Immunother. Cancer. 2018;6(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0371-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gordon C.J., Tchesnokov E.P., Woolner E., Perry J.K., Feng J.Y., Porter D.P., Götte M. Remdesivir is a direct-acting antiviral that inhibits RNA-dependent RNA polymerase from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 with high potency. J. Biol. Chem. 2020;295(20):6785–6797. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA120.013679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huynh K., Partch C.L. Analysis of protein stability and ligand interactions by thermal shift assay. Curr.Protoc.Protein Sci. 2015;79(1):28–29. doi: 10.1002/0471140864.ps2809s79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kabir A., Honda R.P., Kamatari Y.O., Endo S., Fukuoka M., Kuwata K. Effects of ligand binding on the stability of aldo–keto reductases: implications for stabilizer or destabilizer chaperones. Protein Sci. 2016;25(12):2132–2141. doi: 10.1002/pro.3036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cimmperman P., Baranauskienė L., Jachimovičiūtė S., Jachno J., Torresan J., Michailovienė V., Matulienė J., Sereikaitė J., Bumelis V., Matulis D. A quantitative model of thermal stabilization and destabilization of proteins by ligands. Biophys. J. 2008;95(7):3222–3231. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.134973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adcock S.A., McCammon J.A. Molecular dynamics: survey of methods for simulating the activity of proteins. Chem. Rev. 2006;106(5):1589–1615. doi: 10.1021/cr040426m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cvetkovic R.S., Goa K.L. Lopinavir/Ritonavir. Drugs. 2003;63:769–802. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200363080-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chen F., Chan K.H., Jiang Y., Kao R.Y.T., Lu H.T., Fan K.W., Cheng V.C.C., Tsui W.H.W., Hung I.F.N., Lee T.S.W., Guan Y. In-vitro susceptibility of 10 clinical isolates of SARS coronavirus to selected antiviral compounds. J. Clin. Virol. 2004;31(1):69–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2004.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heidary F., Gharebaghi R. Ivermectin: a systematic review from antiviral effects to covid-19 complementary regimen. J. Antibiot. 2020;73(9):593–602. doi: 10.1038/s41429-020-0336-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kory P., Meduri G.U., Varon J., Iglesias J., Marik P.E. Review of the emerging evidence demonstrating the efficacy of ivermectin in the prophylaxis and treatment of COVID-19. Am. J. Ther. 2021;28(3) doi: 10.1097/MJT.0000000000001377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Caly L., Druce J.D., Catton M.G., Jans D.A., Wagstaff K.M. The FDA-approved drug ivermectin inhibits the replication of SARS-CoV-2 in-vitro. Antivir. Res. 2020;178 doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2020.104787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Li W., Moore M.J., Vasilieva N., Sui J., Wong S.K., Berne M.A., Somasundaran M., Sullivan J.L., Luzuriaga K., Greenough T.C., Choe H. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426(6965):450–454. doi: 10.1038/nature02145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hoffmann M., Schroeder S., Kleine-Weber H., Müller M.A., Drosten C., Pöhlmann S. Nafamostat mesylate blocks activation of SARS-CoV-2: new treatment option for COVID-19. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020;64(6) doi: 10.1128/AAC.00754-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hoffmann M., Kleine-Weber H., Schroeder S., Krüger N., Herrler T., Erichsen S., Schiergens T.S., Herrler G., Wu N.H., Nitsche A., Müller M.A. SARS-CoV-2 cell entry depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and is blocked by a clinically proven protease inhibitor. Cell. 2020;181(2):271–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.02.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Y., Zhang Y., Chen X., Xue K., Zhang T., Ren X. Evaluating the efficacy and safety of bromhexine hydrochloride tablets in treating pediatric COVID-19: a protocol for meta-analysis and systematic review. Medicine. 2020;99(37) doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000022114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hu J., Gao Q., He C., Huang A., Tang N., Wang K. Development of cell-based pseudovirus entry assay to identify potential viral entry inhibitors and neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2. Genes Dis. 2020;7(4):551–557. doi: 10.1016/j.gendis.2020.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhao M.M., Yang W.L., Yang F.Y., Zhang L., Huang W.J., Hou W., Fan C.F., Jin R.H., Feng Y.M., Wang Y.C., Yang J.K. Cathepsin L plays a key role in SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans and humanized mice and is a promising target for new drug development. Signal Transduct.Target.Ther. 2021;6(1):1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00558-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Cheng Y.W., Chao T.L., Li C.L., Chiu M.F., Kao H.C., Wang S.H., Pang Y.H., Lin C.H., Tsai Y.M., Lee W.H., Tao M.H. Furin inhibitors block SARS-CoV-2 spike protein cleavage to suppress virus production and cytopathic effects. Cell Rep. 2020;33(2) doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.108254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary data