Objectives

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a serious impact on the psychological well-being of frontline health care workers. A variety of interventions have been offered to health care workers in their workplace that has them questioning which intervention would be most beneficial. The purpose of this review is to determine what evidence-based interventions would have an impact on alleviating COVID-19-related psychological distress.

Methods

A search was conducted from multiple databases, including Pubmed, CINAHL, Joanna Briggs, and Cochrane, using the PRISMA framework. The search included COVID-19 as well as previous pandemics. Critical appraisal and synthesis of the 16 relevant sources of evidence were completed.

Results

Based on the current evidence, one cannot conclude that any specific intervention is effective for pandemic-relate distress.

Conclusion

The development, implementation, and scientific evaluation of evidence-based interventions to address the immediate, as well as the long-term, psychological effects of COVID-19 on the mental well-being of health care workers, are needed.

Keywords: COVID-19, evidence-based intervention, psychological distress

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a physical, mental, and emotional challenge for frontline health care workers (HCWs) in the United States and around the world. These psychological effects have been studied and described in the scientific literature.1-3 Less narrative has been shared on effective evidenced-based interventions or treatment strategies for the initial or long-term mental distress of HCWs related to COVID-19. During the initial COVID-19 surges and continuing today, many health care organizations have begun to offer numerous and varied interventions to promote HCWs' psychological well-being. The HCWs are often indecisive and perplexed as to which, if any, type of intervention would benefit them most. The question arises as to what interventions have been studied and have proven to be most effective. The purpose of this review is to answer the following clinical question: For HCWs working frontline during the COVID-19 pandemic, what evidence-based interventions would have an impact on alleviating COVID-19-related psychological distress?

Our interest in this review stems from our challenges and experiences as frontline critical care nurses in one of New York's COVID-19 epicenters. The progression from the first confirmed case in March 2020 to treating more than 4000 cases and witnessing more than 900 deaths in less than 18 months was overwhelming. As cases increased, all surgeries and in-hospital procedures were canceled. Ambulatory sites were closed. All waiting and conference rooms were converted to inpatient care areas. Our hospital bed capacity increased by greater than 50% to accommodate the influx of COVID-19 patients. Recovery rooms, ambulatory recovery, and procedural units were converted to intensive care units, which more than tripled our 48 licensed critical care beds. Staff were besieged by overhead announcements for rapid responses and code blues that were heard at least every 15 minutes. Staffing was supplemented by traveling and flex HCWs to assist with the workload. Staff from closed areas were deployed to the inpatient and intensive care units to assist with patient care. Advanced practice nurses, retired nurses, and nurse educators returned to the bedside and were utilized in units with staffing gaps.

The COVID-19 surge in New York City from March 2020 to December 2021 brought challenges, fears, plus psychological, physical, and moral distress far beyond what anyone could have imagined. During those first few months, we were at the forefront of learning about the characteristics of this new virus and its effects on patients. Each day brought with it changes in policies, procedures, and treatment protocols as the latest information was uncovered and disseminated. The experience of caring for patients with a novel disease produced fear and heightened anxiety. Frontline staff were resigning to work for agencies that offered dramatically higher wages, which only worsened the staffing shortages. The physical and mental burden of working for months in this environment was evident in our staff.

Our institution began to offer a variety of psychological support services during the initial surge and has added a greater diversity of services for the staff since that time. With numerous options offered, staff question where to put their time and effort for maximal effect. Which psychological support would be effective? As members of the Nursing Research and Evidence-Based Practice Council, we wondered if there was any evidence to help answer this question. A literature search was conducted to find the evidence. To facilitate our literature search, we first developed our PICO question: For HCWs working frontline during COVID-19, what evidenced-based interventions and treatment strategies would alleviate their psychological distress?

Population/Problem (P): Frontline HCW who worked during COVID-19 and experienced psychological distress

Intervention (I): Evidence-based interventions/treatment strategies

Comparison (C): Nonspecified

Outcome (O): Impact on psychological distress

DEFINITION OF TERMS

The psychological distress of pandemics on frontline HCWs as documented in the literature manifests as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)/posttraumatic stress syndrome, depression, anxiety, somatization, sleep disorders, acute stress, burnout, fear, anger, grief, and guilt. This is the definition used throughout this article.

SEARCH STRATEGY

The PICO framework was used for the search strategy based on the population, intervention, comparison, and outcome. The search was conducted in June 2020, updated in June 2021, and again in May 2022. Databases included PubMed, CINAHL, MEDLINE, and Joanna Briggs. Relevant articles were extracted from the reference section of the identified papers found in the initial and subsequence searches. Only articles published in English were accepted. To ensure an exhaustive search, we included all levels of research design. Search terms included words from the PICO question as well as relevant synonyms, inclusive of MESH terms and subject headings. Boolean operators were used to facilitate the search.

Population: (healthcare worker OR nurse OR clinician OR medical professional OR healthcare provider) AND (pandemic OR disaster OR crisis OR COVID OR COVID-19 OR SARS COVID-19 OR SARS-CoV-2 OR MERS OR severe acute respiratory syndrome OR coronavirus OR coronavirus infections) AND (stress OR stressors OR distress OR traumatization OR anxiety OR depression OR mental disorders OR hopelessness OR helplessness OR mental health OR burnout OR moral injury)

Intervention: (psychological well-being OR resilience OR well-being OR wellness OR mental health OR coping OR psychological coping OR self-care)

Comparison: none

Outcome: impact on psychological distress or PTSD/PTSS or depression or anxiety or somatization or sleep disorders or acute stress or burnout or fear or anger or grief or guilt.

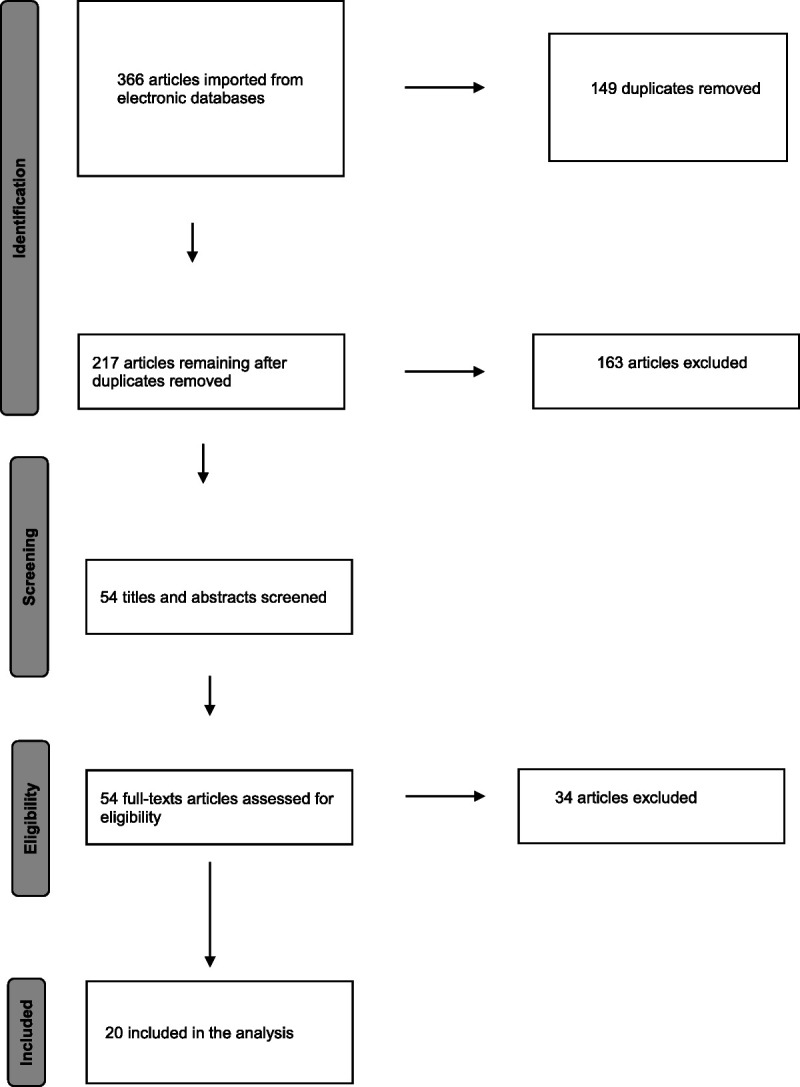

The search strategy for the relevant sources of evidence initially identified 366 articles, of which 149 duplicates were removed; therefore, 217 potentially eligible articles remained. Two reviewers evaluated the 217 articles for relevance to answer the clinical question. After title and abstract review, 163 articles were excluded. After a full-text review of 54 articles, 34 further articles were eliminated, and 20 articles were identified as relevant sources. The summary of the sources of evidence included in this review is outlined in the PRISMA flow chart (Figure).

Figure.

PRISMA Flow Chart.

CRITICAL APPRAISAL

The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme tools were used based on the specific study design to determine the quality of the individual sources of evidence. Data extraction was completed on the Table of Evidence (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Table of Evidence

| Source | Design/Level of Evidence | Participants | Intervention | Results | Quality or Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reviews | |||||

| Buselli et al (2021) | Narrative review, level V | 9 interventions reviewed, 7 published programs, 2 ongoing trials | Review of organizational interventions put in place to address HCW stress during COVID-19 | A beneficial program was unable to be identified owing to the heterogeneity of programs and lack of standardized protocols. | No ability to recommend best intervention |

| Cabarkapa et al (2020) | Systematic review of descriptive and qualitative studies, level V | 100 sources reviewed | Reviewed measurement of psychological impact of pandemics on HCWs and methods to address them | Pandemics result in similar psychological effects for HCWs; there are limited data to recommend interventions that are effective. | Highlights gaps in the research for further study |

| Chew et al (2020) | Systematic review of descriptive and qualitative studies, level V | 23 sources reviewed | Reviewed studies that reported on psychological responses as well as coping in previous pandemics | Several individual as well as institution measures for coping were identified. | Identifies gaps in the current literature for further research |

| David et al (2021) | Narrative review, level V | 31 studies reviewed | Summarized interventions developed during COVID-19 to support HCWs' emotional well-being | 3 groups of support were identified; longevity and sustainability are key issues. | Highlights gaps in the research for further study |

| Muller et al (2020) | Systematic review of descriptive and qualitative studies, level V | 59 sources reviewed | Summarized the research on the mental health impact of on HCWs | Intervention studies focused on the individual and not the organization; none reported on the effects of their interventions on HCWs. | Identifies gaps in the current literature for further research |

| Pollock et al (2020) | Mixed-methods systematic review, level V | 16 studies, 7 qualitative, 9 descriptive | Reviewed studies that reported implementation of intervention for HCWs during disease outbreaks | There was a lack of evidence to inform the selection of particular interventions beneficial to HCWs. | Identifies areas for further research |

| Published studies | |||||

| Blake et al (2020) | Qualitative study, level VI | 55 HCWs from various disciplines | Development and evaluation of e-learning package related to psychological well-being for HCWs | The frequency of access and attitude toward the method's practicality and usability were measured, rated high for usability and practicality. | Very low, single intervention, did not measure effectiveness for HCWs' pandemic distress |

| Dincer and Inangi (2020) | RCT, level II | 72 frontline COVID-19 nurses | Random assignment to intervention group (1 online group EFT session) or nontreatment control group | The intervention group demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in measures of stress, anxiety, and burnout. | Low, 1 intervention studied, preintervention and postintervention measurement once only, no longitudinal follow-up, no comparison interventions |

| Fiol-DeRoque et al (2021) | RCT, level II | 483 frontline COVID-19 HCWs randomly assigned to PsyCovidApp intervention group or a control app group | The PsyCovidApp targets emotional skills, healthy lifestyle behavior, burnout, and social support based on CBT and mindfulness | Data were collected at baseline and 2 weeks postimplementation—reduced mental health problems at 2 weeks were found only among HCWs receiving psychotherapy or psychotropic medications. | Low, relevant to our outcome criteria |

| Shechter et al (2020) | Qualitative study, level VI | 657 nurses, physicians, advanced practice providers, residents, and fellows | Physical activity, access to online therapy, cross-sectional survey, standardized email with link to Qualtrics survey | Implementation is in progress, no outcomes as yet. | Low-moderate, single intervention, no comparison to demonstrate best intervention |

| Teall and Melnyk (2021) | Descriptive study, level VI | 104 nurses participated in the program for 6 weeks, nurses paired with 1 of 49 APN student coaches | Wellness Partner Program—a program to provide support to nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic | >90% of participants reported that the program helped them engage in self-care and wellness and improved their physical and mental health. | Program evaluation outcomes not intended to provide valid generalizable data, identifies area for future research |

| Trottier et al (2022) | Descriptive study, level VI | 21 participants, HCWs who experienced stress or trauma related to COVID-19 | RESTORE (Recovery from Extreme Stressors Through Online Resources and E-health), online, cognitive behavioral interventions | There was a statistically significant improvement for measurements of anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms. | Low, no control group, small n, potential for future research |

| Zerbini et al (2020) | Qualitative study, level VI | 75 nurses: 45 COVID units, 30 regular units; 35 physicians: 17 COVID unit, 18 regular unit | Focus on assessment of psychological effects using standardized survey tools but 1 open-ended question related to psychological support | Family, friends, and leisure time were reported as resilience factors by most participants; psychosocial support is another important resource. | Low, no comparison of best intervention |

| Expert opinion | |||||

| Clancy et al (2020) | Expert opinion, level VII | N/A | N/A | Self-care strategies, including personal awareness, team support, increasing emotional reserves, and night shift interventions, were reviewed. | Very low, no comparison to demonstrate best intervention |

| Duncan (2020) | Expert opinion, level VII | N/A | N/A | Brief review of resilience in previous pandemics/disasters; review of personal resilience in nursing. In general, resilient individuals cope better; no research exists on resilience and COVID-19. | Very low, no comparison to demonstrate best intervention |

| Morley et al (2020) | Expert opinion, level VII | N/A | N/A | A brief overview of the ethical issues causing moral distress for caregivers with evidence-based recommendations for leaders was presented. | Very low no comparison to demonstrate best intervention |

| Rosa et al (2020) | Expert opinion, level VII | N/A | N/A | The authors provided recommendations for leaders based on evidence-based general strategies. | Very low no comparison to demonstrate best intervention |

| Viswanathan et al (2020) | Expert opinion, level VII | 130 frontline HCWs in group sessions; 57 in individual sessions | Weekly: 40 minutes videoconferencing group mental health sessions with 2 facilitators per group; individual one-on-one mental health sessions | There was no collection of data either before or after intervention. | Very low, no comparison to demonstrate best intervention |

| Walton et al (2020) | Expert opinion, level VII | N/A | N/A | The authors provided recommendations for organization, leadership, and individual support. | Very low no comparison to demonstrate best intervention |

| Yang et al (2020) | Expert opinion, level VII | N/A | N/A | The authors recommend the WHO Self-help Plus (SH+). | Very low, no comparison to demonstrate best intervention |

Abbreviations: HCW, health care worker; RCT, randomized controlled trial; EFT, Emotional Freedom Tapping; CBT, cognitive behavior therapy; APN, advanced practice nursing; PTSD, posttraumatic stress disorder.

SYNTHESIS OF THE LITERATURE

General Information

The systematic and narrative reviews we found provided a thorough review and analysis of the state of the current evidence. Three of them sought to determine and describe the psychological impact on HCWs working during a pandemic and to shed light on interventions to mitigate this impact.1-3 The studies included in these systematic reviews primarily evaluated the impact of pandemics on HCWs with far fewer exploring interventions to alleviate their effects. It is also of interest to note that they were conducted among different cultural backgrounds, which may influence the results found. The first1 reviewed previous pandemics as well as COVID-19. The second2 looked at previous pandemics only, and the third3 researched only COVID-19.

The other 3 reviews focused only on uncovering interventions put in place to support the mental health of HCWs. One looked for interventions implemented to address the mental health distress experienced by frontline HCWs during any disease outbreak, epidemic, or pandemic.4 It is interesting to note that this review, conducted in May 2020, which sought interventions during the current as well as previous disease outbreaks (Ebola, severe acute respiratory syndrome [SARS], Middle East respiratory syndrome, and COVID-19), uncovered only 16 studies that showed the implementation of an intervention specifically directed at supporting the mental health of frontline workers.4 The other 2 reviews looked only for, and reviewed, interventions related to the current COVID-19 pandemic5,6 and uncovered 9 and 31 studies, respectively.

Social Support

Social support was cited as the most utilized, helpful, and predominant coping mechanism in the studies.1-3,7 The support was described as that from family and friends, colleagues and coworkers, religious groups, and organizations such as one's workplace. The support from family and friends was reported to help HCWs cope with their work1,2 and was a main motivational factor for them to continue working.3 Seeking support from friends and family was rated as a “very important” coping mechanism.3 Several studies highlighted the need for increased social support and regular contact with family members.2 Nurses who chose to isolate themselves from their families during the SARS epidemic reported a negative impact.2 Social support, often cited as a source of help during distress, is not unexpected as humans are relational in nature. We find meaning and happiness in a relationship with others. Upon careful review of the literature, the question arises as to whether social support, particularly that from family and friends, is rated high because it is deemed helpful as compared with other interventions or because it is the easiest and most readily available means of support for most of the participants. Most studies in this review obtained these results with surveys and questions seeking participants' perceptions of experiences they found helpful.1-3,7 They did not evaluate or measure social support against other interventions.

The support from coworkers and colleagues is reported similarly in the literature to that of family and friends. Studies found that those who perceived receiving support from colleagues reported less incidence of acute stress and PTSD.1 Several studies reported that colleagues caring for and encouraging each other were a common coping mechanism and that a greater sense of camaraderie prevailed amid the COVID-19 crisis.2 From the author's personal experience, HCWs reported that talking their feelings through with colleagues was the most helpful coping mechanism, as they were the only ones who truly understood the experience of working during the pandemic. There were no studies uncovered in our search to demonstrate the prevalence of this experience.

Social support provided through organizations has been implemented in different forms. Psychosocial workshops provided throughout the workplace, a buddy system for coworkers to take care of one another, and mentoring of junior nurses by senior nurses were reported to reduce the measurement of stress.2 Frontline nursing staff were paired with advanced practice nursing student coaches in a structured Wellness Partner Program during COVID-19.8 One-on-one coaching focused on personalized support and improvement of health and well-being. This program was not evaluated for its effectiveness in relieving particular aspects of distress but instead the program itself was evaluated—its feasibility and reception by staff. The intent was to roll out a program aimed at supporting staff in a timely manner that could then be copied by others. One publication described a plan for the implementation of a formalized buddy system adapted from the military. It is a psychological resilience intervention model for support during a crisis.9 It described in detail their plan for implementation and the background supporting its development, but the study is in progress, so no data are available yet. We await the results of this study and are hopeful others are in the works that will be reported soon. Several studies demonstrated social support came from religion for many HCWs, with some praying before work.2,10

Professional Psychological Support

In terms of professional psychological support and counseling services, there is limited evidence available. The rates of interest and utilization of professional support varied greatly in the literature. There was a wide range of HCWs who reported that they were interested in receiving psychological support, from 5% to 40%,2,10 and an even wider disparity was reported among HCWs who utilized professional support. In 1 study of the SARS epidemic, 89% of participants reported that psychiatric services were a great form of support and helped them to reduce stress.2 Several COVID-19 studies showed utilization of professional counseling from 18% to 36%3 and another indicated that HCWs showed an interest in professional counseling but did not actually receive it.10 Engagement with professional support services is also dependent on enabling HCWs to have the time to participate in the offered programs.6 It may also rely on the promotion of “workplace mental health literacy” and integrating programs into the employee experience.6 One study reported satisfaction by employees with a psychological hotline phone number that was implemented and could be called for immediate support from a professional counselor.3 A cross-sectional survey during COVID-19 found that “talk therapy” was rated as very helpful for HCWs; however, it did not specify what this term meant. It is unclear if it means talking to friends and colleagues or professional psychological counseling.10

One institution used psychiatrists from their hospital to provide group therapy for frontline COVID-19 HCWs and, when indicated, one-on-one counseling for those who identified a need.11 They did not collect any data on the effectiveness of their program but rather reported on their plan as a model for support that could be implemented quickly during a crisis. In nearly every publication on interventions for pandemic-related distress, recommendations are made for increased availability and ease of access to professional psychological support, but there is little indication of how many sought this support and the extent to which it was helpful to alleviate their distress as compared with other interventions.

Practical Support/Active Coping/Problem Solving

Many studies and expert opinions point to activities identified as practical support helpful to HCWs during pandemics. These activities include basic physical self-care actions such as eating right, maintaining good sleep hygiene habits, staying hydrated, and exercising.3,7,10,12-14 Other measures identified were active coping or problem solving. These included separate clothing for work and procedures for cleaning them, as well as measures to avoid contamination of personal items and their homes upon arrival from work. Obtaining information and education to guide actions and obtaining adequate personal protective equipment (PPE) were reported to decrease stress.2,3

We uncovered 3 specific intervention studies designed to evaluate the impact of distinct therapies to alleviate distress for HCWs during COVID-19. The use of Emotional Freedom Tapping was shown to decrease anxiety, stress, and burnout in COVID-19 nurses.15 This randomized controlled trial was a 1-time intervention with an assessment of preintervention and postintervention levels of only 3 measures of pandemic-related distress. Longitudinal studies of this intervention in the future, with broader distress measurements, would assist in determining its effectiveness. A self-help psychological support app for smartphones was developed for use in frontline COVID-19 HCWs.16 This randomized controlled trial used a psychoeducational mindfulness-based intervention, the PsychApp, to reduce mental health problems, and measured effectiveness based on depression, anxiety, stress, insomnia, burnout, PTSD, and self-efficacy scores. Analysis of the data showed that the only participants whose mental health problems were reduced during the study period were those who were receiving psychotherapy or psychotropic medication, regardless of the use of the app. Another online intervention, Recovering from Extreme Stressors through Online Resources and E-health, found statistically significant improvements in anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms in its participants.17 The small number of participants and the uncontrolled design of the study are significant limitations, but the results hold promise for future research of this type. The authors note that this is the first published outcome data from an intervention of this nature in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.17

The impact of practical support cannot be overstated. As Maslow's hierarchy of needs has informed us for years, until you meet one's basic physiologic and safety needs, you cannot address those higher up in the pyramid. Several studies that surveyed HCWs' psychological needs during a pandemic reported that more than 50% of those surveyed indicated that they had a greater need for PPE than for psychological help.3

Organization Interventions

Much of the practical support in the literature is related to that provided by the organization and its leadership. There was an absence of evidence evaluating organizational interventions. We reviewed and included high-level expert opinion articles to shed light on this area. Several broad categories are addressed: communication, compensation, education, staffing, and provision of readily available resources. Communication is cited the most as a key component. Clear communication has been reported to decrease stress and psychological symptoms.1,2 Transparent communication by leaders and communication that goes in both directions were recommended by expert opinions.14,18 Effective communication also includes the practice of debriefing to address both specific events and the psychological distress of staff.19

Accessibility of leadership18 and compensation have been shown to decrease stress for pandemic HCWs.1,2 Staff training and education regarding infection control, proper use of PPE, and the enforcement of infection control measures had been shown to reduce staff stress.2,3 Staffing and scheduling of staff, which include arranging for appropriate time off, respite weeks, shift management, and thoughtful redeployment of staff, have been shown to decrease the stress of workers.2,3,18 Fostering the well-being of staff by the availability of psychological support services and on-site drop-in psychological services are recommended in the expert literature.18,20

The use of the World Health Organization's Self-help Plus program has been recommended for organizations to implement easily and inexpensively.21 Self-Help Plus is a group-based self-help intervention developed by the World Health Organization to meet the challenges of delivering evidence-based mental health support to large numbers of people in disaster-affected areas.

Negative Coping Mechanisms

There is some research indicating that HCWs utilize negative coping activities during pandemics. Avoidance, denial, and substance abuse have been measured.2 The extent to which these were used should be evaluated moving forward. In the author's experience, many of our coworkers reported drinking more alcohol during their time working during COVID-19, but there are no hard data to indicate its prevalence. It would be enlightening to assess to what extent coping activities considered to be negative were used and how damaging or helpful they were.

Resilience

In several studies, subjects who scored higher in resilience scored lower in negative distress measures.2 Having a positive attitude and positive reframing of a situation have been shown to decrease stress in HCWs during pandemics.2,7 Many of the expert opinion articles recommend the incorporation of measures to develop resilience in HCWs.12-14 There is little evidence as to what factors contribute to resilience in HCWs, particularly during an epidemic. This would be an area for future research as resilience is inversely related to one's experience of negative effects.

CONCLUSIONS

The psychological effects of COVID-19 on frontline HCWs are well documented in the literature, but interventions to alleviate them have been less studied. Despite the urgent call from the international community to study and publish specific psychological support intervention programs for HCWs, few countries have done so.5 Based on the evidence, one cannot conclude that any specific intervention will be effective for a particular form of pandemic-related distress. A preponderance of studies only evaluated distress for which there are readily available measurement tools (such as anxiety, stress, and burnout) and omitting other experiences (such as PTSD, insomnia, grief, and fear). Addressing the full spectrum of distress needs to be included in research moving forward. The evidence also indicates that most interventions focused on the individual, and there was a lack of organizational approaches studied.

In many organizations, numerous support interventions are being offered to staff in the wake of COVID-19. An interesting paradox that has been noted in the literature is the discrepancy between the support being offered and the perception of this support. Ninety-five percent of HCWs report having access to some sort of psychological support through their place of employment, but as many as 75% report not feeling supported by their employer.22 This emphasizes the sense of urgency for research in this area. Spending money but not achieving the desired objectives helps neither the institution nor the individual.

Many factors contribute to limitations in the current body of evidence: primarily online survey methodology, self-reporting measures, lack of randomized control trials, lack of prepandemic psychological risk factors, and lack of follow-up and longitudinal studies. A frequent recommendation in the literature is that “longitudinal research on the specific psychological needs of HCWs will help to generate evidence-based interventions to mitigate the adverse mental health outcomes they experience.”22 High-quality research is needed to determine the efficacy of interventions for individuals and organizations, both proactive and reactive, to develop a more resilient health care workforce that is better prepared for the current as well as future pandemics.

The negative impacts of COVID-19 on HCWs' mental health stress the need for the development and evaluation of effective sustainable evidence-based interventions that can address both acute and long-term effects during and outside the pandemic. Scientific evidence is fundamental to determining treatment guidelines and best practices moving forward for the needs of HCWs.

We are currently in a very different place than we were 3 years ago with the global COVID-19 public health crisis. The lessons we have learned and currently emerging knowledge will be fundamental to facing the next public health challenge.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jane Ellen Barr, DNP, RN, CWON, and Janice Lester, MLS, for their support.

Footnotes

Nancy Delassalle and Mary Cavaciuti are cochairs of the Research and Evidence-Based council.

Nancy Delassalle and Mary Cavaciuti are co–primary authors.

The authors have disclosed that they have no significant relationships with, or financial interest in, any commercial companies pertaining to this article.

References

- 1.Cabarkapa S, Nadjidai S, Murgier J, Ng C. The psychological impact of COVID-19 and other viral epidemics on frontline healthcare workers and ways to address it: a rapid systematic review. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2020;8:100144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chew Q, Wei K, Vasoo S, Sim K. Psychological and coping responses of health care workers toward emerging infectious disease outbreaks. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(6):20r13450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Muller A Hafstad E Himmels J, et al. The mental health impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers, and interventions to help them: a rapid systematic review. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pollock A Campbell P Cheyne J, et al. Interventions to support the resilience and mental health of frontline health and social care professionals during and after a disease outbreak, epidemic or pandemic: a mixed methods systematic review. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;11(11):CD013779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Buselli R Corsi M Veltri A, et al. Mental health of health care workers (HCWs): a review of organizational interventions put in place by local institutions to cope with new psychosocial challenges resulting from COVID-19. Psychiatry Res. 2021;299:113847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.David E, DePierro JM, Marin DB, Sharma V, Charney DS, Katz CL. COVID-19 pandemic support programs for healthcare workers and implications for occupational mental health: a narrative review. Psychiatr Q. 2022;93(1):227–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zerbini G, Ebigbo A, Reicherts P, Kunz M, Messman H. Psychosocial burden of healthcare professionals in times of COVID-19—a survey conducted at the University Hospital Augsburg. Ger Med Sci. 2020;18:Doc05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teall AM, Melnyk BM. An innovative wellness partner program to support the health and well-being of nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic: implementation and outcomes. Nurs Adm Q. 2021;45(2):169–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Albott CS, Wozniak JR, McGlinch BP, Wall MH, Gold BS, Vinogradov S. Battle buddies: rapid deployment of a psychological resilience intervention for health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Anesth Analg. 2020;131(1):43–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shechter A Diaz F Moise N, et al. Psychological distress, coping behaviors, and preferences for support among New York healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;66:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Viswanathan R, Myers M, Fanous A. Support groups and individual mental health care via video conferencing for frontline clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychosomatics. 2020;61(5):538–543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clancy G, Gaisser D, Wlasowicz G. COVID-19 and mental health. Nursing. 2020;50(9):60–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duncan D. What the COVID-19 pandemic tells us about the need to develop resilience in the nursing workforce. Nurs Manage. 2020;27(3):22–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Walton M, Murray E, Christian M. Mental health care for medical staff and affiliated healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2020;9(3):241–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dincer B, Inangi D. The effect of emotional freedom techniques on nurses' stress, anxiety, and burnout levels during the COVID-19 pandemic: a randomized controlled trial. Explore (NY). 2021;17(2):109–114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiol-DeRoque MA Settano-Ripoll MJ Jimenez R, et al. A mobile phone–based intervention to reduce mental health problems in health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic (PsyCovidApp): randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2021;9(5):e27039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Trottier K, Monson C, Kaysen D, Wagner A, Liebman R, Abbey S. Initial findings on RESTORE for healthcare workers: an internet-delivered intervention for COVID-19-related mental health symptoms. Transl Psychiatry. 2022;12:222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosa W, Schlak A, Rushton C. A blueprint for leadership during COVID-19. Nurs Manage. 2020;51(8):28–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morley G, Sese D, Rajendram P, Horsburgh C. Addressing caregiver moral distress during the COVID-19 pandemic [published online ahead of print June 9, 2020]. Cleve Clin J Med. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blake H, Bermingham F, Johnson G, Tabner A. Mitigating the psychological impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: a digital learning package. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(9):2997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang L, Yin J, Wang D, Rahman A, Li X. Urgent need to develop evidence-based self-help interventions for mental health of healthcare workers in COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Med. 2020;51(10):1775–1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dawood B, Tomita A, Ramlall S. ‘Unheard,’ ‘uncared for’ and ‘unsupported’: the mental health impact of COVID-19 on healthcare workers in KwaZulu-Natal Province, South Africa. Plos One. 2022;17(5):e0266008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]