Abstract

Maternal mRNA translation is regulated in large part by cytoplasmic polyadenylation. This process, which occurs in both vertebrates and invertebrates, is essential for meiosis and body patterning. In spite of the evolutionary conservation of cytoplasmic polyadenylation, many of the cis elements and trans-acting factors appear to have some species specificity. With the recent isolation and cloning of factors involved in both poly(A) elongation and deadenylation, the underlying biochemistry of these reactions is beginning to be elucidated. In addition to early development, cytoplasmic polyadenylation is now known to occur in the adult brain, and there is circumstantial evidence that this process occurs at synapses, where it could mediate the long-lasting phase of long-term potentiation, which is probably the basis of learning and memory. Finally, there may be multiple mechanisms by which polyadenylation promotes translation. Important questions yet to be answered in the field of cytoplasmic polyadenylation are addressed.

Important advances in understanding the cytoplasmic control of gene expression occurred in the late 1980s. In those years, it was shown unambiguously that sequences within the 3′ untranslated regions (UTRs) of specific mRNAs direct polyadenylation and translational activation in maturing mouse and frog oocytes. Although before that time polyadenylation was correlated with translation (see, e.g., reference 66), no experiments showed a clear cause-and-effect relationship. In addition, 3′ UTRs were generally thought to be rather devoid of regulatory information—didn’t it make more sense to control translation at the 5′ end? Since then, major inroads have been made into the biochemistry not only of cytoplasmic poly(A) addition but also of poly(A) removal. Furthermore, we can now feel confident that in most cases, poly(A) elongation confers translational activation while deadenylation promotes translational silencing. Here, I will focus almost exclusively on the forces responsible for, and the results of, poly(A) tail changes during early development. However, a new study indicating that regulated polyadenylation may be important for adult brain functions is also discussed. For reviews of the cytoplasmic polyadenylation field prior to 1996, see references 59 and 64. For a discussion of 3′ UTRs in general, a number of sources are available (31, 72, 105). Similarly, there are several recent reviews on the continually evolving field of nuclear polyadenylation (11, 99). Finally, for further discussions of development of translational control and the biochemistry of protein synthesis, the reader is referred to references 34 and 52.

POLY(A) TAIL CHANGES OCCUR IN EARLY DEVELOPMENT

The oocytes of probably most animals contain an amount of mRNA that far exceeds the immediate protein synthesis requirements of the cell. Much of this mRNA, which is dormant or masked, will be inherited by the egg following fertilization. At that time, as well as in later embryonic stages, several mRNAs will be recruited onto polysomes in a sequence-specific and often location-specific manner. In a number of vertebrates, such as Xenopus and the mouse, some dormant mRNAs in oocytes will become translationally active prior to fertilization, during meiotic maturation. Generally, the dormant mRNAs in oocytes have relatively short poly(A) tails, usually fewer than about 20 nucleotides. During oocyte maturation, the tails on specific mRNAs grow to about 80 to 150 nucleotides, and translation ensues (major exceptions include histone mRNAs [55]). However, not all mRNAs that undergo polyadenylation during maturation do so at the same time, for there appear to be early and late adenylating mRNAs. Also during maturation, some translating mRNAs that have the usual long poly(A) tail (∼100 to 200 nucleotides) undergo a deadenylation reaction, which results in their translational repression.

Embryos from invertebrates also display dynamic changes in polyadenylation. In Drosophila, the regulated poly(A) tail changes of several mRNAs are essential for correct embryonic patterning. Superimposed on this regulation, of course, is the exquisite control of mRNA localization, which perhaps complicates the analysis of essential sequences and factors. In Caenorhabditis elegans, the regulation of mRNA polyadenylation may be important for sex determination. Finally, while the biological importance has not yet been elucidated, poly(A) length changes also occur during the very early development of several marine invertebrates, such as the surf clam and the sea urchin.

Polyadenylation in Xenopus Development

cis elements.

Due to their ease of microinjection and because large quantities may be easily obtained for biochemical fractionation, Xenopus oocytes have proven to be a useful source material for studying the biochemistry of cytoplasmic polyadenylation. Although earlier studies had shown that maturing oocytes contain mRNAs that undergo polyadenylation and commensurate translation (see, e.g., reference 19), it was not until 1989 that the cis elements necessary for these processes were described (20, 53). Two sequences in the 3′ UTRs of responding mRNAs are essential, the near-ubiquitous AAUAAA, which is also crucial for nuclear pre-mRNA cleavage and polyadenylation, and a U-rich sequence that often resides about 20 nucleotides 5′ of the hexanucleotide. This is the cytoplasmic polyadenylation element (CPE), which has the consensus structure of UUUUUAU. The CPE can support polyadenylation when it overlaps with the hexanucleotide, when it is immediately adjacent to it, or when it is up to 100 nucleotides distant (17, 54; see references 64, 78, and 80 for reviews). However, because the timing of polyadenylation of different mRNAs varies during maturation, there may be additional regulatory information in the CPE itself. For example, the sequence UUUUUAU may promote polyadenylation earlier during maturation than, say, UUUUAAU, or perhaps the distance of the CPE from the hexanucleotide influences the time when given mRNAs undergo this 3′ end modification (4, 17). Alternatively, there may be additional 3′ UTR sequences that influence polyadenylation (see, e.g., references 27 and 76).

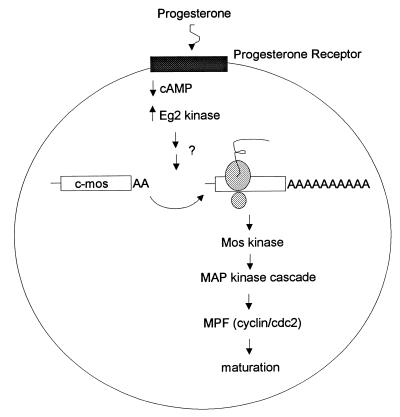

Before discussing cytoplasmic polyadenylation in detail, it is important to understand the salient features of oocyte maturation in Xenopus (Fig. 1) (68, 88). Following progesterone binding to a putative cell surface receptor, there is an essential but transient decrease in the level of cyclic AMP, which is thought to activate specific protein kinases (1). These events then lead to c-mos mRNA polyadenylation and translation. This is a critical step, because oocytes contain no Mos protein, and it must be made entirely de novo from mRNA that undergoes cytoplasmic polyadenylation (42, 68, 73, 74). Additional evidence indicates that other, as yet undefined mRNAs must also be polyadenylated and translationally activated at this time (6, 47). Following the synthesis of Mos, which is a mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase kinase kinase, MAP kinase kinase and MAP kinase are activated by, of course, phosphorylation. This leads to eventual maturation-promoting factor (MPF) activation. MPF, which is composed of cyclin B1 and cdc2 (cyclin-dependent kinase type 1 [CDK1]) kinase, is most directly responsible for the many manifestations of oocyte maturation, such as germinal vesicle breakdown (GVBD) and chromatin condensation. Importantly, cdc2 kinase is also involved in a feedback loop of kinase activation, and so it is sometimes difficult to know with absolute certainty which kinase phosphorylates a given substrate (33).

FIG. 1.

Critical events during Xenopus oocyte maturation. Progesterone binds a putative cell surface receptor, which leads to a transient decrease in cyclic AMP (cAMP) levels and the activation of Eg2 kinase. Subsequently, dormant c-mos mRNA undergoes polyadenylation-induced translational activation. Newly synthesized Mos, a serine/threonine kinase, activates MAP kinase kinase (MAP kinase cascade), which culminates in the activation of MPF (a heterodimer composed of cyclin B and cdc2). Active MPF, which phosphorylates a number of substrates, is most directly responsible for the manifestations of oocyte maturation.

A time course experiment during maturation reveals that c-mos mRNA is polyadenylated much earlier than other mRNAs such as those encoding histone B4 and cyclins A1 and B1 (4, 17, 72). To determine whether late-adenylating mRNAs require the early-adenylating mRNA product(s) (e.g., Mos), c-mos mRNA was ablated by an antisense oligonucleotide. While this prevented histone B4 and cyclin A1 and B1 mRNAs from undergoing polyadenylation, it did not inhibit the polyadenylation of injected c-mos RNA (4, 17). Thus, mRNAs such as cyclins A1 and B1 must contain a Mos response element (MRE), whose polyadenylation function is directly or indirectly influenced by Mos. A mutational analysis of the cyclin B1 3′ UTR revealed that one CPE that overlaps with the polyadenylation hexanucleotide corresponded to the MRE (17). Interestingly, the CPE and hexanucleotide of cyclin A1 mRNA have this same configuration, which corresponds to the MRE of this transcript. In a similar vein, Ballantyne et al. (4) have shown that the polyadenylation of certain sets of mRNAs but not others is sensitive to active cdc2 kinase. Therefore, while it appears that there are two pathways for polyadenylation during maturation, both probably require activation by phosphorylation. In addition, another lesson that should clearly be drawn from these studies is that we can no longer discuss cytoplasmic polyadenylation in generic terms—rather, we must refer to this process with specific mRNAs in mind. Of course, this has important implications when determining the activity of polyadenylation-inducing factors; the RNA substrate that is used would clearly be crucial.

Oocytes cultured in both progesterone and cycloheximide fail to undergo meiotic maturation. However, oocytes cultured in cycloheximide that are injected with Mos protein do undergo maturation, indicating that Mos synthesis is all that is required for maturation (68, 69). On the other hand, a subsequent study that examined c-mos mRNA polyadenylation and translation suggests that the situation may be more complex. In this case, Sheets et al. (74) injected a “prosthetic” RNA into oocytes that would anneal with the 3′ UTR of c-mos mRNA. Because the prosthetic RNA also contained a poly(A) tail, it induced the translation of c-mos mRNA. However, such injected oocytes would mature only if they were also incubated in progesterone. Taken at face value, these data suggest that in addition to Mos, the synthesis of another protein(s) must occur for oocyte maturation to proceed. Recent data from Barkoff et al. (6) also indicate that this is the case, but they go further and suggest that, like Mos, the synthesis of this other essential but undefined protein is the result of mRNA cytoplasmic polyadenylation-induced translation. This general conclusion was also reached by Kuge et al. (47).

As noted earlier, some Xenopus mRNAs undergo poly(A) elongation only during embryogenesis. For many mRNAs, polyadenylation at this time requires the hexanucleotide AAUAAA and a CPE. Here, however, this CPE is of the “embryonic” type, which is oligo(U)12–27 (75–77). While the mRNAs that are polyadenylated during maturation often encode cell cycle-regulatory proteins (Mos, cyclins, cdk2, etc.), those that are polyadenylated in the embryo may be important for germ layer formation or patterning. For example, activin receptor mRNA, which is involved in mesoderm induction, undergoes polyadenylation and translation in the embryo, and interference with this process results in embryos with a number of morphological defects (77).

To date, the embryonic-type CPE is the only clearly defined sequence that promotes polyadenylation in embryos. However, Verrotti et al. (97) have shown that Drosophila bicoid mRNA, which contains no element that obviously resembles a CPE, also undergoes polyadenylation in injected Xenopus embryos. These data indicate that there is at least one more sequence that promotes embryonic polyadenylation.

trans factors.

In its simplest form, polyadenylation during maturation must involve at least three factors: one that binds the CPE, one that binds the hexanucleotide, and, of course, poly(A) polymerase (PAP). The CPE is bound by CPEB, an RNA recognition motif (RRM)- and zinc finger-containing protein that has putative homologues in other vertebrates and in invertebrates (5, 25, 36, 100). While initial studies suggested that the phosphorylation of CPEB was important for the activation of polyadenylation (62), recent evidence indicates that it is more likely to be involved in the eventual destruction of the protein (17). In addition, phosphorylation does not appear to influence RNA binding (35).

To examine the importance of CPEB in vivo, antibody to this protein was injected into oocytes. Not only did this treatment inhibit the polyadenylation of c-mos mRNA, but also it abrogated the synthesis of Mos. Thus, it is not surprising that CPEB antibody injection also prevented oocyte maturation (78). These data therefore confirm the original in vitro experiments demonstrating that the immunodepletion of CPEB from egg extracts rendered them incompetent for polyadenylation (36).

It has been suggested that one possible function of CPEB is to recruit or stabilize factors that interact with the hexanucleotide, which in turn might serve as an anchor for poly(A) polymerase (PAP) (7, 36). Initial biochemical fractionation experiments by Fox et al. (22) indicated that the hexanucleotide could be bound by cleavage and polyadenylation specificity factor (CPSF), which is well known for its role in nuclear pre-mRNA polyadenylation (99). Subsequently, Bilger et al. (7) noted that heterologous CPSF and PAP stimulated polyadenylation in a CPE-dependent manner. However, U-rich sequences upstream and downstream of the AAUAAA are known to facilitate nuclear CPSF activity (29), and so it is unclear if the results of Bilger et al. (7) are a recapitulation of the nuclear activity. At present, there are no data demonstrating, say, an inhibition of egg extract polyadenylation following CPSF immunodepletion. In the absence of results of this kind, it is difficult state with certainty that CPSF is involved in cytoplasmic polyadenylation.

The third factor that is essential for polyadenylation is PAP. Xenopus oocytes, like many somatic cells, have multiple forms of this enzyme (3, 24, 110, 111), one of which lacks a nuclear localization signal and hence would be expected to be entirely cytoplasmic (24). While this protein has PAP activity when expressed in bacteria, it has not been detected in oocytes. Therefore, whether cytoplasmic polyadenylation utilizes a special (i.e., nonnuclear) form of the enzyme is unclear. However, it should be borne in mind that the “nuclear” form of the enzyme is also cytoplasmic in oocytes (3), and so it is certainly possible that this enzyme catalyzes polyadenylation in both compartments (but see below).

During oocyte maturation, cdc2 kinase phosphorylates PAP at a number of sites (3, 13). Interestingly, as the enzyme becomes hyperphosphorylated, it becomes progressively less active (12, 13), such that by late maturation it has virtually no activity at all (13). This would seem paradoxical because there is robust cytoplasmic polyadenylation activity at this time. Perhaps this indicates that there is at least one form of PAP that is not inactivated by phosphorylation.

Recent evidence suggests that the CPE and CPEB have a second function, that of mRNA masking (18). In oocytes, cyclin B1 mRNA has a short poly(A) tail and is translationally dormant. During maturation, the poly(A) tail is elongated and translation ensues. While this scenario seems straightforward vis-à-vis mRNA activation, it does not delineate the mechanisms responsible for the initial translational repression of the mRNA. To address this, deMoor and Richter (18) began with the assumption that cyclin B1 mRNA might be bound by a repressor protein (perhaps analogous to FRGY2 [9]), which could be competed off by multiple exogenous copies of the binding site. Therefore, they injected various portions of cyclin B1 RNA into oocytes and determined whether endogenous cyclin B1 protein was synthesized. Interestingly, injection of the B1 RNA 3′ UTR induced cyclin B1 synthesis. A mutational analysis subsequently revealed that it was the CPE itself that was responsible for the translational unmasking and that the strength of the unmasking was correlated with the number of CPEs injected. Furthermore, while a reporter mRNA could be masked if it was appended with a CPE-containing 3′ UTR, it had to undergo cytoplasmic polyadenylation before it could be translated during maturation. Therefore, the CPE acts both negatively (as a repressor of translation) and positively (as an activator of polyadenylation-induced translation).

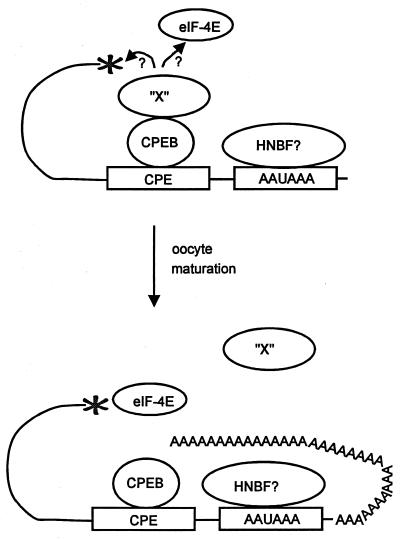

How could the CPE perform both tasks? Clearly, that depends on the nature of the interacting proteins. deMoor and Richter (18) identified CPEB as the only CPE binding protein. Thus, could CPEB both repress and enhance translation? A model to explain how this could be so is presented in Fig. 2, a key feature of which is a putative CPEB binding protein. Here, they suggest that in immature oocytes, CPEB binds not only the CPE but also a factor “X” protein. Factor X, in turn, might interact with the cap or with a translation initiation factor such as eIF-4E to prevent translation. When the cyclin B1 3′ UTR is injected into oocytes, CPEB and factor X might compete off endogenous cyclin B1 mRNA, thereby releasing it for translation. During the normal course of oocyte maturation, however, it may be that polyadenylation, which is necessary for unmasking, disrupts the CPEB-factor X interaction to allow translation to begin. While further experimentation could certainly cause revisions to this model, it is noteworthy that Stutz et al. (85, 86), have obtained somewhat similar data with maturing mouse oocytes (but with a notable exception—in these mammalian cells, mRNA unmasking does not require polyadenylation [see below]).

FIG. 2.

Model for CPE-mediated translational repression and activation. In immature oocytes, CPEB binds both the CPE and a hypothetical factor, factor X. Factor X, in turn, prevents translation either by interacting with the cap or by preventing eukaryotic initiation factors (i.e., eIF-4E) from recognizing the cap. A possible hexanucleotide binding factor (HNBF), which could be CPSF, is also indicated. Following oocyte maturation, CPEB induces cytoplasmic polyadenylation, which disrupts CPEB-factor X interaction and allows initiation factor binding to the cap and translation initiation.

A single factor has been described in Xenopus that is thought to be involved in embryonic cytoplasmic polyadenylation. A 36-kDa protein, which was subsequently identified as ElrA (108), was shown to UV cross-link to the oligo(U)12–27 embryonic CPE (75, 77). ElrA is a member of the ELAV family of RNA binding proteins (30, 65). While ElrA binds quite specifically to the oligo(U)12–27 CPE, both in vitro and in vivo, its role in polyadenylation has not been conclusively demonstrated. Interestingly, however, a dominant negative form of the protein inhibits normal gastrulation in injected embryos, quite possibly because the polyadenylation-induced expression of an essential mRNA(s) is disrupted.

Deadenylation in Xenopus Development

cis element.

Ribosomal-protein mRNAs exemplify those transcripts that are deadenylated and translationally silenced during oocyte maturation (93, 94). These mRNAs have no specific sequence that directs deadenylation; rather, they undergo this reaction by default because they contain no CPE to promote poly(A) addition at this time (21, 94). In contrast to the situation during oocyte maturation, deadenylation in the embryo requires mRNA-specific cis elements. Cdk2 mRNA, for example, undergoes CPE-directed polyadenylation at maturation but is deadenylated soon after fertilization. Two sequences within the 3′ UTR of this mRNA direct embryo-specific deadenylation; one, composed of 58 nucleotides, is immediately upstream of the CPE, while the other, composed of 14 nucleotides, is 3′ of the hexanucleotide. While each element promotes partial deadenylation individually, together they appear to act synergistically to promote complete deadenylation (79). While seemingly discrete in nature, these cdk2 cis-deadenylation elements are not obviously present in other mRNAs that undergo this reaction at this time.

Other RNAs contain a different embryonic deadenylation element, sometimes referred to as the EDEN sequence (2, 8, 48, 49). This is a 17-nucleotide, somewhat internally repetitious sequence in the 3′ UTRs of Eg2, Eg5, and c-mos mRNAs (8, 60). Like the 3′ cdk2 embryonic deadenylation element, the EDEN sequence can confer specific deadenylation to a reporter RNA (60).

Finally, it has recently been shown that an AU-rich element normally thought to promote mRNA degradation in a variety of systems (10), AUUUA, mediates deadenylation in Xenopus embryos (98). Although this might appear surprising on the surface, it has been shown that in mammalian tissue culture cells, deadenylation precedes mRNA decay (10). For Xenopus embryos, it appears that the first-step deadenylation reaction is temporally uncoupled from mRNA destruction, which normally occurs at the 4,000-cell mid-blastula stage, several hours after deadenylation.

trans factors.

During oocyte maturation, dissolution of the nuclear envelope, i.e., GVBD, precedes and is essential for default deadenylation. This suggests that at least one factor involved in this process must be sequestered in the nucleus prior to GVBD (92). While the nature of this factor has not yet been firmly established, significant progress has been made in addressing the underlying mechanisms of deadenylation with the isolation and cloning of two proteins, the first of which is a deadenylating nuclease [DNA, subsequently referred to as a poly(A)-specific RNase (PARN) (45)]. This protein, a member of the RNase D family initially isolated from mammalian somatic tissue (44), is mostly cytoplasmic in HeLa cells, but its localization in oocytes is less clear. In these cells, two proteins, of 62 and 74 kDa, are detected on a Western blot. The 62-kDa species is cytoplasmic, while the 74-kDa species is nuclear. While the relationship, if any, between these two proteins is unknown, the 74-kDa protein may correspond to the functional deadenylase. This conclusion is based on the observations that (i) proper default deadenylation requires a nuclear component that must be released after GVBD and (ii) cytoplasmic extracts have little deadenylation activity. Irrespective of which of these two proteins is the true PARN, perhaps the most important result is that antibody raised against the mammalian protein, when injected into oocytes, prevents default deadenylation (45). With the PARN cDNA clone now in hand, the molecular regulation of deadenylation, in maturing oocytes as well as in embryos, may soon be elucidated.

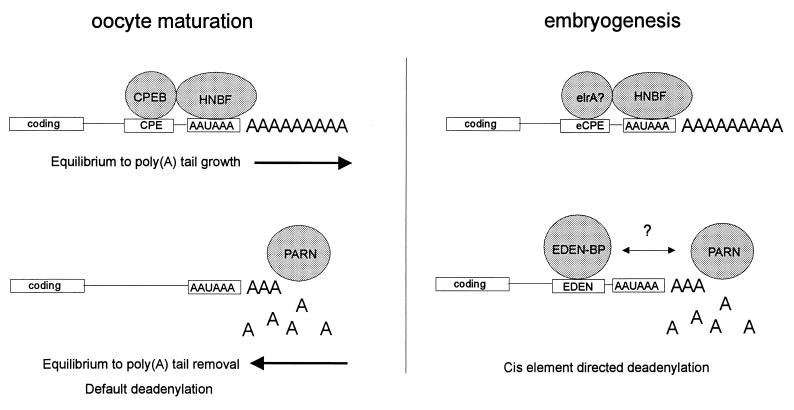

A second, recently cloned factor that is important for deadenylation specifies which mRNAs lose their poly(A) tails after fertilization. Following the earlier work of Bouvet et al. (8), who identified a 53- and 55-kDa protein doublet that bound the EDEN sequence, Paillard et al. (60) isolated and cloned a cDNA for this factor, referred to as EDEN-BP. The necessity of EDEN-BP for the deadenylation of specific RNAs was demonstrated by using egg extracts. While these extracts support EDEN-dependent Eg2 deadenylation, they fail to do so following EDEN-BP immunodepletion. Interestingly, EDEN-BP shows high homology to two other proteins, which suggests that it may be a multifunctional protein. The first protein is human Nab50/CUG-BP (60, 92), which is 88% identical to the Xenopus protein. Nab50/CUG-BP, whose only known function is that it binds CUG repeats, may be involved in myotonic dystrophy, because one characteristic of this disease is a CUG repeat expansion in the 3′ UTR of myotonin protein kinase mRNA. The second protein with homology to EDEN-BP is Drosophila Bruno (101). Bruno protein is a translational repressor of oskar mRNA, whose localized expression is critical for posterior body patterning (43). While it is possible that Nab50/CUG-BP and Bruno regulate mRNA expression by deadenylation, there is currently no evidence indicating that this is the case. Thus, it may be that this family of RNA binding proteins controls translation in multiple ways. A summary of the essential features of poly(A) additional and removal during Xenopus development is presented in Fig. 3.

FIG. 3.

Essential features of poly(A) addition and removal during Xenopus development. In oocytes, CPEB binds the CPE and shifts an equilibrium between poly(A) tail growth or removal in the direction of growth. For mRNAs that do not contain a CPE, the equilibrium is shifted toward poly(A) tail removal, which is often referred to as default deadenylation. The enzyme responsible for deadenylation is PARN. HNBF refers to hexanucleotide binding factor. During embryogenesis, poly(A) tail elongation is directed by an embryonic-type CPE (eCPE), which is oligo(U)12–27. The eCPE is bond by the protein elrA, a member of the ELAV family of RNA binding proteins. In contrast to oocyte maturation, deadenylation in embryos is directed by the EDEN cis element. The EDEN sequence is bound by the protein EDEN-BP, which may interact, directly or indirectly, with PARN.

Polyadenylation in Early Mouse Development

cis elements.

Many features of oocyte maturation in Xenopus also take place in the mouse, including cytoplasmic polyadenylation (26). At least for tissue-type plasminogen activator (tPA) (37), c-mos (27), spindlin (57), and cyclin B1 (87) mRNAs, the same cis elements used in Xenopus are used in the mouse. That is, a structure closely resembling the UUUUUAU-type CPE, also called the adenylation control element (ACE), and the AAUAAA hexanucleotide are required. Other RNAs that are polyadenylated during maturation have these sequences, although mutagenesis experiments have not been performed to establish that they are necessary (38, 58, 63, 96, 103).

In contrast to Xenopus, most maternal mRNAs in the mouse are destroyed by the two-cell stage, when the zygotic genome becomes active. Thus, one might surmise that maternally inherited mRNAs would play a lesser role in this species. While this might be the case, recent studies indicate that cytoplasmic polyadenylation and presumably translational activation occur soon after fertilization in the mouse, suggesting at least some important roles for maternal mRNAs. Putative CPEs (either the maturation type or the embryonic type) are present in two transcripts that are polyadenylated after fertilization, catenin mRNA (58) and another mRNA of unknown function (90). Interestingly, Oh et al. (57) have recently shown that not only does spindlin mRNA undergo polyadenylation during oocyte maturation and after fertilization but also its 3′ UTR contains a maturation-type and an embryonic-type CPE.

trans factors.

Because the UUUUUAU-type CPE controls polyadenylation during mouse oocyte maturation, it is perhaps not surprising that this sequence is bound by CPEB (25). The frog and murine proteins are highly homologous, especially in the carboxy-terminal, RNA binding portion of the protein. Like the frog protein, mouse CPEB is phosphorylated during maturation (89), although the function of this modification is unknown.

Stutz et al. (86) have taken a novel approach to the study of factors involved in cytoplasmic polyadenylation. These investigators injected oocytes with antisense oligodeoxynucleotides complementary to various regions of tPA mRNA; they then examined the expression of this mRNA by the sensitive zymography assay. The rationale behind such an experiment is that sequences that are, say, bound by regulatory proteins would be inaccessible to oligonucleotide binding, and hence, RNase H-mediated RNA digestion would not occur. The result would then be robust tPA activity, which could be quantified by zymography. Perhaps not surprisingly, Stutz et al. (86) showed that the CPE/ACE and the AAAAA were protected from RNase H-mediated cleavage. However, a somewhat unexpected finding was that early during maturation, a portion of the CPE/ACE and the hexanucleotide became accessible to oligonucleotide annealing and resulting mRNA cleavage. From this, Stutz et al. (86) concluded that the mRNA becomes unmasked prior to polyadenylation.

In a follow-up study, Stutz et al. (85) showed that endogenous tPA mRNA is translationally activated when oocytes are injected with fragments of RNA that contain the CPE/ACE. In this sense, then, this is similar to what deMoor and Richter (18) observed with cyclin B1 mRNA in injected Xenopus oocytes (see above). However, one major difference in these studies is that while polyadenylation is required to unmask cyclin B1 mRNA in Xenopus oocytes, it is not required to unmask tPA mRNA in mouse oocytes. Rather, Stutz et al. (85) suggest that an 80-kDa protein, which binds the CPE/ACE, must be removed from that sequence to allow translation to occur. While this would suggest that polyadenylation plays no role in translational activation, these investigators found that the unmasking event requires a short (∼30-nucleotide) poly(A) tail. Thus, they surmised that the maturation-specific polyadenylation of tPA mRNA is necessary to prevent default deadenylation, which, if it occurred, would maintain translational arrest. Indeed, Huarte et al. (37) found that the deadenylation of tPA mRNA that occurs during oocyte growth is important for the initial translational repression. As for the 80-kDa protein, its identity is unknown, but on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels, its relative mobility is similar to that of mouse CPEB (25).

Polyadenylation in Drosophila Development

cis elements.

Axis formation in the Drosophila embryo requires the precise temporal and spatial expression of a number of mRNAs (14, 16, 83). While the translation of maternal mRNA in this species is probably controlled at multiple levels, one important mechanism is the modulation of poly(A) tail length. For example, bicoid, Toll, and torso mRNAs, all of which play important roles in body patterning, undergo poly(A) elongation and translational activation (70). The mRNA selectivity for this reaction is demonstrated by the fact that nanos mRNA, which is translationally activated at nearly the same time as the three aforementioned mRNAs, displays no obvious poly(A) tail length change (23, 70).

Schisa and Strickland (71) have investigated the cis elements responsible for cytoplasmic polyadenylation of Toll mRNA. They found that in contrast to vertebrates, there are no small, discrete, polyadenylation-inducing signals. Rather, these investigators noted that a 192-nucleotide element, when deleted from the Toll mRNA 3′ UTR, abrogates polyadenylation but by itself cannot induce polyadenylation. Schisa and Strickland (71) further suggested that there may be several nonhomologous regions of Toll RNA that can direct polyadenylation.

trans factors.

Given that very little is known about the cis elements that direct polyadenylation in Drosophila, one might surmise that nothing would be known about the proteins that direct this process. However, using a genetic approach, the Strickland laboratory has identified two genes that may be involved. Lieberfarb et al. (50) examined a number of female-sterile mutations for the possible down-regulation of bicoid gene expression. Two mutations, cortex and grauzone, were indeed found to be correlated with reduced bicoid levels. Most importantly, neither bicoid nor Toll mRNA undergoes cytoplasmic polyadenylation in either of these mutant embryos. Moreover, nanos mRNA, whose expression does not involve changes in poly(A) tail length, is translated in cortex embryos. Thus, the proteins encoded by cortex and grauzone may be a part of the polyadenylation complex. Two other proteins that could be important in Drosophila polyadenylation have been identified by UV cross-linking to the Toll mRNA 192-nucleotide polyadenylation element (71). Other than RNA binding, however, only the sizes of these proteins (101 and 89 kDa) are known.

Deadenylation in Drosophila Development

trans factors.

In Drosophila embryos, the localized translational repression of specific mRNAs is essential for correct axis formation. At least one mRNA, hunchback, appears to be repressed via cytoplasmic deadenylation. While nothing is known of the cis elements that control the deadenylation of this mRNA, some gene products have been identified that may be involved in this process. It has been known for several years that nanos mRNA, which resides exclusively in the posterior pole of the Drosophila embryo, is essential for structures that later arise from that location. Nanos protein appears to function as a translational repressor. That is, it is important that the expression of hunchback mRNA, which is distributed uniformly in the embryo, be limited to the anterior pole. Thus, it is Nanos protein that suppresses the translation of hunchback mRNA in the posterior pole (39, 84). The region of hunchback mRNA that is important for the translational repression imposed by Nanos is the 3′ UTR, and discrete nanos-responsive elements (NREs) within this region have been defined (104). What would appear to be a somewhat straightforward situation of translational repression is made more complicated by the fact that Nanos does not bind the NRE (or at least not with a high degree of specificity). Instead, the pumillio gene product binds hunchback NRE (56). However, both Nanos and Pumilio appear to repress hunchback mRNA translation by inducing mRNA deadenylation (107). How these factors promote deadenylation is unknown, but this process is likely to be an essential step in the generation of abdominal structures.

Deadenylation in Caenorhabditis elegans Development

cis elements and trans factors.

In C. elegans, the regulated translation of a few mRNAs is necessary for sex determination (31, 105). The sex of these hermaphroditic animals is controlled by the X-to-autosome ratio; XX animals are hermaphrodites (basically females that make oocytes and sperm), whereas XO animals are males. One gene that determines the sex of the animal is tra-2; when it is deleted, XX animals become males. The tra-2 gene is regulated at the translational level by two cis elements in its 3′ UTR, referred to as DREs (direct-repeat elements) or, more recently, as TREs (tra-2 and GLI elements) (40). The TGE, AAUUUAUU, is required for the inhibition of tra-2 mRNA expression, which is correlated with the maintenance of a short poly(A) tail (40).

Immediately upstream of tra-2 is the laf-1 gene, which is a negative regulator of tra-2 expression (31). One possible function of the laf-1 protein is that of a deadenylation-inducing translational repressor of tra-2 mRNA. The inhibition of tra-2 mRNA translation would prevent female development (40). A factor, tentatively identified as DRF (direct-repeat factor), which could be the laf-1 gene product, binds the TREs (32, 40). In transgenic animals, TRE-dependent translational repression and the maintenance of a short poly(A) tail requires laf-1. In vitro, the TGEs serve as binding sites for DRF. Thus, while laf-1 has not yet been cloned and DRF has not yet been isolated, circumstantial evidence suggests that they could be the same factor.

POLYADENYLATION IN THE CENTRAL NERVOUS SYSTEM

Although cytoplasmic polyadenylation is a hallmark of early metazoan development, there is virtually no evidence that it occurs in adult tissues. From a teleological point of view, this would seem very inefficient. That is, a significant genetic load is used to regulate translation by cytoplasmic polyadenylation, so why not use the process in adult tissues just as it is used in early development? Perhaps it is used in adult tissues, but we just don’t know where to look, or even how to look. What adult tissues contain dormant mRNAs that must be activated in an instant? How can we examine polyadenylation in somatic tissues where mRNA injection is extremely difficult?

Clearly, knowing where to look is paramount. In the last few years, mounting evidence has suggested that the brain might contain dormant mRNAs. In particular, specific mRNAs are present in dendrites (15, 81), and synaptic spines (regions at the bases of synapses) have ribosomes and translation initiation factors (82, 91). Most importantly, recent studies indicate that translational control in dendrites may be important for long-term changes in synaptic efficacy (41, 51). Even if this brain activity is regulated at the translational level, how could one assess whether cytoplasmic polyadenylation is involved? One approach, taken by Wu et al. (109), was to determine if a factor that regulates cytoplasmic polyadenylation, CPEB, is present in the brain. Although CPEB expression is quite restricted in the mouse (25), brain tissue contains readily detectable amounts. Furthermore, CPEB is present in the dendritic layers of the hippocampus, at synapses in cultured hippocampal neurons, and in postsynaptic densities (i.e., large networks of structural and regulatory proteins immediately beneath the postsynaptic membrane) of adult brain (109). Thus, the localization of CPEB strongly suggests that it could be involved in synaptic efficacy.

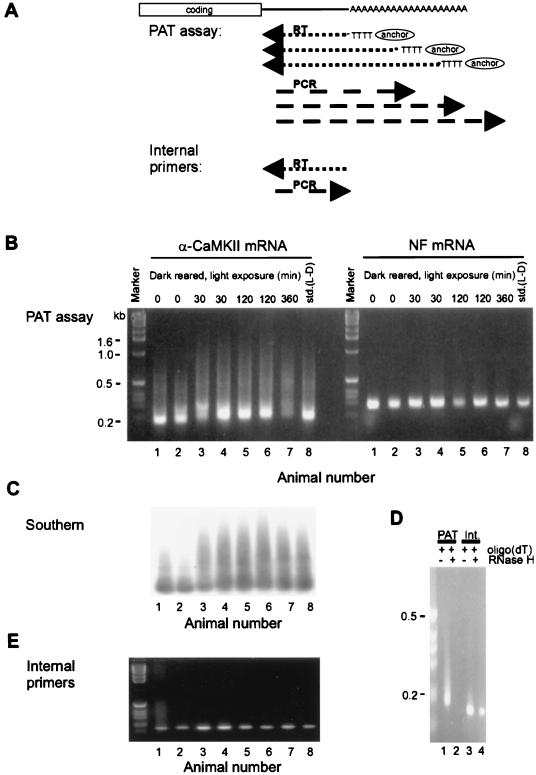

Of course, the function of CPEB in the brain depends upon the mRNA(s) to which it is bound. One mRNA, which is present in dendrites and known to be essential for the long-lasting phase of long-term potentiation (L-LTP) encodes Ca2+-calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II (α-CaMKII). The 3′ UTR of α-CaMKII mRNA contains UUUUUAU-type CPEs, which bind CPEB in vitro and which drive polyadenylation-induced translation in injected Xenopus oocytes. While suggestive, these data do demonstrate that this process also occurs in the brain. To examine this, Wu et al. (109) investigated the visual cortex, which also contains CPEB. In dark-reared rats, there is a massive activity-driven reorganization in the visual cortex following exposure to light. In this region of the brain, light exposure induces polyadenylation and translation of α-CaMKII mRNA but does not affect the poly(A) tail length of neurofilament mRNA, which does not contain a CPE (Fig. 4). Thus, cytoplasmic polyadenylation may be essential for L-LTP, which probably forms the basis for learning and memory.

FIG. 4.

Poly(A) tail elongation in the central nervous system. (A) The method used to detect poly(A) tail length is the RT-PCR-based PAT [poly(A) test]. Here, oligo(dT) fused to a GC-rich anchor will anneal to multiple regions along the length of a poly(A) tail. When it is reverse transcribed, the resulting cDNAs will be heterogeneous in size. Following PCR with an mRNA-specific primer and the oligo(dT) anchor, the size heterogeneity will be maintained. Thus, mRNAs with long poly(A) tails will yield cDNAs of diverse sizes, the largest of which will approximate the longest poly(A) tail. On the other hand, mRNAs with short poly(A) tails will yield smaller cDNAs with discrete sizes. In addition, PCR with two mRNA-specific primers will result in products with discrete sizes (internal control). RT, reverse transcription. (B) Visual cortices were removed from rats born and raised in the dark (dark rearing) and then either not exposed to light or exposed to light for 30 to 360 min. The visual cortices were also removed from rats maintained on a standard 12-h light-dark cycle (std.). Following RNA extraction, PATs were performed for α-CaMKII mRNA, which contains a CPE, and neurofilament (NF) mRNA, which does not contain a CPE. The PATs used the same reverse transcription reaction. The products were resolved on an agarose gel and visualized by ethidium bromide staining. Note that the poly(A) tail of α-CaMKII mRNA was elongated in response to light, while the poly(A) tail of NF mRNA was unaffected. (C) The α-CaMKII PCR products from panel B were Southern blotted and probed with radiolabeled α-CaMKII 3′ UTR. This blot confirms that the ethidium bromide staining material in panel B corresponds to α-CaMKII sequences and also shows light-dependent polyadenylation of this mRNA. (D) An aliquot of visual cortex RNA annealed to excess oligo(dT) was incubated with RNase H, which removes the poly(A) tail. This was followed by a PAT for α-CaMKII mRNA, or reverse transcription-PCR with internal, mRNA-specific primers. This control confirms that the heterogeneously sized α-CaMKII sequences in panel B resulted from oligo(dT) priming of the poly(A) tail. (E) Reverse transcription-PCR with two α-CaMKII 3′ UTR-specific primers was performed on the same visual cortex RNA used in panel B. This control confirms that the 3′ UTR of α-CaMKII mRNA was intact, since the PCR product is discrete and has the predicted size. Reprinted from reference 109 with permission of the publisher.

POLYADENYLATION AND THE MECHANISMS OF TRANSLATIONAL ACTIVATION

In yeast, the poly(A) tail stimulates translation through several protein intermediates, one of which is poly(A) binding protein. This factor, in turn, interacts with the translation initiation factor eIF-4G. eIF-4G binds to another translation initiation factor, eIF-4E, which also binds to the cap. It is this circular complex, then, that aids in recruiting the 40S ribosomal subunit to the mRNA (reviewed in reference 67; see also reference 102). Is this model applicable to say, mRNAs undergoing poly(A) elongation during oocyte maturation? While it has not yet been tested in these cells, a number of facets will almost certainly prove to be correct. For example, a long poly(A) tail appended to a number of mRNAs is sufficient to induce their translation following oocyte injection (61, 74, 95). It would follow, then that these poly(A) tails bind poly(A) binding protein, which binds eIF-4G, etc., which would result in translation. On the other hand, it should be borne in mind that poly(A) binding protein is not abundant in oocytes (110) and, when it is expressed in moderate amounts by mRNA injection, it disrupts the normal default deadenylation that occurs at maturation (106). Of course, oocytes could contain proteins that perform the same task as poly(A) binding protein but are structurally distinct and therefore are not detected with poly(A) binding protein antibody. Indeed, oocyte-specific poly(A) binding proteins have been observed by UV cross-linking (87).

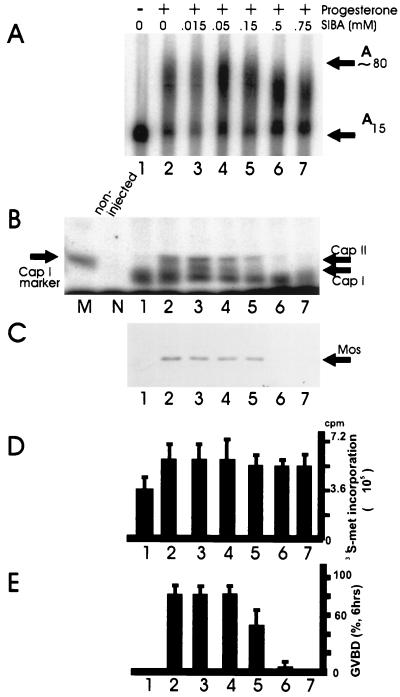

Alternatively, oocytes may use a unique translational strategy. In this regard, Kuge and Richter (46) have demonstrated that during Xenopus oocyte maturation, active poly(A) elongation induces cap-specific 2′-O methylation (i.e., cap I and cap II, which have methyl groups at the 2′ position of the first and second ribose moieties following the triphosphate bridge, respectively). Two experiments argue that cap ribose methylation is important for translation: (i) prevention of 2′-O methylation abrogates translational activation with little effect on polyadenylation (Fig. 5), and (ii) mRNAs that contain cap I prior to injection are translated more efficiently that those with cap 0 (i.e., lacking 2′-O methylation) (47). However, because this modification occurs on only a subset of mRNAs that are polyadenylated at maturation (28), it may be that polyadenylation induces translation in multiple ways.

FIG. 5.

Inhibition of cap ribose methylation abolishes progesterone-induced Mos synthesis and oocyte maturation in Xenopus. (A and B) Oocytes were incubated in the indicated concentrations of S-isobutylthioadenosine (SIBA), an analogue of S-adenosylmethionine, from which methyl groups are donated in methyltransferase reactions. SIBA is a stable competitive inhibitor of methyltransferase reactions. These oocytes were also incubated in the absence (lane 1) or presence (lanes 2 to 6) of progesterone and analyzed for the polyadenylation (A) and methylation (B) of injected c-mos mRNA. M refers to a marker for cap I formation, and N refers to noninjected mRNA processed in an identical manner. Note that while SIBA had little effect on polyadenylation, cap I and cap II formation was completely eliminated at 0.5 and 0.75 mM SIBA. (C) Western blot for Mos protein. Note that while immature oocytes contain no Mos (lane 1), this protein accumulates during oocyte maturation (lane 2). While SIBA has no effect on Mos synthesis at the lower concentrations, it completely prevents Mos accumulation at 0.5 and 0.75 mM. (D) General protein synthesis (i.e., [35S]methionine incorporation) in oocytes was unaffected by SIBA irrespective of concentration. (E) Oocyte maturation (as scored by GVBD) paralleled that of Mos synthesis. That is, the prevention of Mos synthesis by SIBA inhibited oocyte maturation. The bars in panels D and E represent the mean and standard deviation of three experiments. Reprinted from reference 47 with permission of the publisher.

CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

The modulation of poly(A) tail length is clearly an evolutionarily conserved mechanism for regulating mRNA translation. While much biochemistry remains to be performed before the details of the process can be understood, a number of facets deserve particular attention, and these may be placed in broad categories. The first is that of initial activation. At least in Xenopus and mouse oocytes, phosphorylation and dephosphorylation events seem likely to be the trigger for poly(A) elongation. However, this conjecture is based on older studies of oocyte maturation, and we do not know the kinases, or even the substrates, which are important for polyadenylation. Second, does cytoplasmic polyadenylation regulate brain activity and/or other functions in the adult? In this regard, tissue-specific CPEB knockout mice, particularly targeted to the hippocampus, would be extraordinarily useful source materials. In addition, a re-examination of the tissue distribution of CPEB would certainly be warranted. Third, how does deadenylation lead to translational silencing in frogs, flies, and worms? Going further, is there an interaction between the EDEN-BP and PARN to induce deadenylation in frog oocytes and embryos? Finally, are there multiple mechanisms of polyadenylation-induced translation, and, if so, how and why are they apparently mRNA specific? Now that several of the factors involved in these processes have been cloned, rapid progress in answering these questions will surely be made.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank Barbara Knowles, Paul MacDonald, and Joan Steitz for communicating unpublished information.

Work in my laboratory is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Andresson T, Ruderman J V. The kinase Eg2 is a component of the xenopus oocyte progesterone-activated signaling pathway. EMBO J. 1998;17:5627–5637. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Audic Y, Omilli F, Osborne H B. Postfertilization deadenylation of mRNAs in Xenopus laevis embryos is sufficient to cause their degradation at the blastula stage. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:209–218. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.1.209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ballantyne S, Bilger A, Astrom J, Virtanen A, Wickens M. Poly(A) polymerases in the nucleus and cytoplasm of frog oocytes: dynamic changes during oocyte maturation and early development. RNA. 1995;1:64–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ballantyne S, Daniel D L, Jr, Wickens M. A dependent pathway of cytoplasmic polyadenylation reactions linked to cell cycle control by c-mos and CDK1 activation. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1633–1648. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.8.1633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bally-Cuif L, Schatz W J, Ho R K. Characterization of the zebrafish Orb/CPEB-related RNA-binding protein and localization of maternal components in the zebrafish oocyte. Mech Dev. 1998;77:31–47. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(98)00109-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barkoff A, Ballantyne S, Wickens M. Meiotic maturation in Xenopus requires polyadenylation of multiple mRNAs. EMBO J. 1998;17:3168–3175. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.11.3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bilger A, Fox C A, Wahle E, Wickens M. Nuclear polyadenylation factors recognize cytoplasmic polyadenylation elements. Genes Dev. 1994;8:1106–1116. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.9.1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bouvet P, Omilli F, Arlot-Bonnemains Y, Legagneux V, Roghi C, Bassez T, Osborne H B. The deadenylation conferred by the 3′ untranslated region of a developmentally controlled mRNA in Xenopus embryos is switched to polyadenylation by deletion of a short sequence element. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1893–1900. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.3.1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouvet P, Wolffe A P. A role for transcription and FRGY2 in masking maternal mRNA within Xenopus oocytes. Cell. 1994;77:931–941. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen C Y, Shyu A B. AU-rich elements: characterization and importance in mRNA degradation. Trends Biochem Sci. 1995;20:465–470. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0004(00)89102-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colgan D F, Manley J L. Mechanism and regulation of mRNA polyadenylation. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2755–2766. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.21.2755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colgan D F, Murthy K G, Prives C, Manley J L. Cell-cycle related regulation of poly(A) polymerase by phosphorylation. Nature. 1996;384:282–285. doi: 10.1038/384282a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colgan D F, Murthy K G, Zhao W, Prives C, Manley J L. Inhibition of poly(A) polymerase requires p34cdc2/cyclin B phosphorylation of multiple consensus and non-consensus sites. EMBO J. 1998;17:1053–1062. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.4.1053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cooperstock R L, Lipshitz H D. Control of mRNA stability and translation during Drosophila development. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1997;8:541–549. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1997.0179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crino P B, Eberwine J. Molecular characterization of the dendritic growth cone: regulated mRNA transport and local protein synthesis. Neuron. 1996;17:1173–1187. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80248-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Curtis D, Lehmann R, Zamore P D. Translational regulation in development. Cell. 1995;21:171–178. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90325-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.deMoor C H, Richter J D. The Mos pathway regulates cytoplasmic polyadenylation in Xenopus oocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6419–6426. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.deMoor C H, Richter J D. The CPE mediates masking and unmasking of cyclinB1 mRNA. EMBO J. 1999;18:2294–2303. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.8.2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dworkin M B, Shrutkowski A, Dworkin-Rastl E. Mobilization of specific maternal RNA species into polysomes after fertilization in Xenopus laevis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1985;82:7636–7640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.22.7636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fox C A, Sheets M D, Wickens M P. Poly(A) addition during maturation of frog oocytes: distinct nuclear and cytoplasmic activities and regulation by the sequence UUUUUAU. Genes Dev. 1989;3:2151–2162. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.12b.2151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fox C A, Wickens M. Poly(A) removal during oocyte maturation: a default reaction selectively prevented by specific sequences in the 3′ UTR of certain maternal mRNAs. Genes Dev. 1990;4:2287–2298. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12b.2287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fox C A, Sheets M D, Wahle E, Wickens M. Polyadenylation of maternal mRNA during oocyte maturation: poly(A) addition in vitro requires a regulated RNA binding activity and a poly(A) polymerase. EMBO J. 1992;11:5021–5032. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05609.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gavis E R, Lehmann R. Translational regulation of nanos by RNA localization. Nature. 1994;369:315–318. doi: 10.1038/369315a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gebauer F, Richter J D. Cloning and characterization of a Xenopus poly(A) polymerase. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:1422–1430. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.3.1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gebauer F, Richter J D. Mouse cytoplasmic polyadenylation element binding protein: an evolutionarily conserved protein that interacts with the cytoplasmic polyadenylylation elements of c-mos mRNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14602–14607. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gebauer F, Richter J D. Synthesis and function of Mos: the control switch of vertebrate oocyte meiosis. Bioessays. 1997;19:23–28. doi: 10.1002/bies.950190106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gebauer F, Xu W, Cooper G M, Richter J D. Translational control by cytoplasmic polyadenylation of c-mos mRNA is necessary for oocyte maturation in the mouse. EMBO J. 1994;13:5712–5720. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06909.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gillian-Daniel D, Gray N K, Åström J, Barkoff A, Wickens M. Modifications of the 5′ cap of mRNAs during Xenopus oocyte maturation: independence from changes in poly(A) length and impact on translation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6152–6163. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.10.6152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilmartin G M, Fleming E S, Oetjen J, Graveley B R. CPSF recognition of an HIV-1 mRNA 3′-processing enhancer: multiple sequence contacts involved in poly(A) site definition. Genes Dev. 1995;9:72–83. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Good P J. A conserved family of elav-like genes in vertebrates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4557–4561. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goodwin E B, Evans T C. Translational control of development in C. elegans. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1997;8:551–559. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1997.0180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Goodwin E B, Okkema P G, Evans T C, Kimble J. Translational regulation of tra-2 by its 3′ untranslated region controls sexual identity in C. elegans. Cell. 1993;22:329–339. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)80074-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gotoh Y, Masuyama N, Dell K, Shirakabe K, Nishida N. Initiation of Xenopus oocyte maturation by activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:25898–25904. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.43.25898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gray N K, Wickens M. Control of translation initiation in animals. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1998;14:399–458. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.14.1.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hake L E, Mendez R, Richter J D. Specificity of RNA binding by CPEB: requirement for RNA recognition motifs and a novel zinc finger. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:685–693. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hake L E, Richter J D. CPEB is a specificity factor that mediates cytoplasmic polyadenylation during Xenopus oocyte maturation. Cell. 1994;79:617–627. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90547-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huarte J, Stutz A, O’Connell M L, Gubler P, Belin D, Darrow A L, Strickland S, Vassalli J D. Transient translational silencing by reversible mRNA deadenylation. Cell. 1992;69:1021–1030. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90620-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hwang S Y, Oh B, Fuchtbauer A, Fuchtbauer E M, Johnson K R, Solter D, Knowles B B. Maid: a maternally transcribed novel gene encoding a potential negative regulator of bHLH proteins in the mouse egg and zygote. Dev Dyn. 1997;209:217–226. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199706)209:2<217::AID-AJA7>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Irish V, Lehmann R, Akam M. The Drosophila posterior-group gene nanos functions by repressing hunchback activity. Nature. 1989;338:646–648. doi: 10.1038/338646a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jan E, Yoon J W, Walterhouse D, Iannaccone P, Goodwin E B. Conservation of the C. elegans tra-2 3′UTR translational control. EMBO J. 1997;16:6301–6313. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.20.6301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kang H, Schuman E M. A requirement for local protein synthesis in neurotropin-induced hippocampal plasticity. Science. 1996;273:1402–1406. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5280.1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kanki J P, Donoghue D J. Progression from meiosis I to meiosis II in Xenopus oocytes requires de novo translation of the mosxe protooncogene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:5794–5798. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.13.5794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kim-Ha J, Kerr K, Macdonald P M. Translational regulation of oskar mRNA by bruno, an ovarian RNA-binding protein, is essential. Cell. 1995;81:403–412. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90393-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Korner C G, Wahle E. Poly(A) tail shortening by a mammalian poly(A)-specific 3′-exoribonuclease. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:10448–10456. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.16.10448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Korner C G, Wormington M, Muckenthaler M, Schneider S, Dehlin E, Wahle E. The deadenylating nuclease (DAN) is involved in poly(A) tail removal during the meiotic maturation of Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J. 1998;17:5427–5437. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.18.5427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuge H, Richter J D. Cytoplasmic 3′ poly(A) addition induces 5′ cap ribose methylation: implications for translational control of maternal mRNA. EMBO J. 1995;14:6301–6310. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00320.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kuge H, Brownlee G G, Gershon P D, Richter J D. Cap ribose methylation of c-mos mRNA stimulates translation and oocyte maturation in Xenopus laevis. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:3208–3214. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.13.3208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Legagneux V, Bouvet P, Omilli F, Chevalier S, Osborne H B. Identification of RNA-binding proteins specific to Xenopus Eg maternal mRNAs: association with the portion of Eg2 mRNA that promotes deadenylation in embryos. Development. 1992;116:1193–1202. doi: 10.1242/dev.116.4.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Legagneux V, Omilli F, Osborne H B. Substrate-specific regulation of RNA deadenylation in Xenopus embryo and activated egg extracts. RNA. 1995;1:1001–1008. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lieberfarb M E, Chu T, Wreden C, Theurkauf W, Gergen J P, Strickland S. Mutations that perturb poly(A)-dependent maternal mRNA activation block the initiation of development. Development. 1996;122:579–588. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.2.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martin K C, Casadio A, Zhu H E Y, Rose J C, Chen M, Bailey C H, Kandel E R. Synapse specific, long-term facilitation of Aplysia sensory to motor synapses: a function for local protein synthesis in memory storage. Cell. 1997;91:927–938. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80484-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.McCarthy J E G. Posttranscriptional control of gene expression in yeast. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1492–1553. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1492-1553.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.McGrew L L, Dworkin-Rastl E, Dworkin M B, Richter J D. Poly(A) elongation during Xenopus oocyte maturation is required for translational recruitment and is mediated by a short sequence element. Genes Dev. 1989;3:803–815. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.6.803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.McGrew L L, Richter J D. Translational control by cytoplasmic polyadenylation during Xenopus oocyte maturation: characterization of cis and trans elements and regulation by cyclin/MPF. EMBO J. 1990;9:3743–3751. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07587.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Muller B, Schumperli D. The U7 snRNP and the hairpin binding protein: Key players in histone mRNA metabolism. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1997;8:567–576. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1997.0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Murata Y, Wharton R P. Binding of pumilio to maternal hunchback mRNA is required for posterior patterning in Drosophila embryos. Cell. 1995;80:747–756. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90353-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Oh, B., S. Y. Hwang, J. McLaughlin, D. Solter, and B. B. Knowles. Submitted for publication.

- 58.Ohsugi M, Hwang S Y, Butz S, Knowles B B, Solter D, Kemler R. Expression and cell membrane localization of catenins during mouse preimplantation development. Dev Dyn. 1996;206:391–402. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199608)206:4<391::AID-AJA5>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Osborne H B, Richter J D. Translational control by polyadenylation during early development. Prog Mol Subcell Biol. 1997;18:173–198. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-60471-3_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Paillard L, Omilli F, Legagneux V, Bassez T, Maniey D, Osborne H B. EDEN and EDEN-BP, a cis element and an associated factor that mediate sequence-specific mRNA deadenylation in Xenopus embryos. EMBO J. 1998;17:278–287. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Paris J, Richter J D. Maturation-specific polyadenylation and translational control: diversity of cytoplasmic polyadenylation elements, influence of poly(A) tail size, and formation of stable polyadenylation complexes. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:5634–5645. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.11.5634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Paris J, Swenson K, Piwnica-Worms H, Richter J D. Maturation-specific polyadenylation: in vitro activation by p34cdc2 and phosphorylation of a 58-kD CPE-binding protein. Genes Dev. 1989;5:1697–1708. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.9.1697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Paynton B V, Bachvarova R. Polyadenylation and deadenylation of maternal mRNAs during oocyte growth and maturation in the mouse. Mol Reprod Dev. 1994;37:172–180. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1080370208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Richter J D. Dynamics of poly(A) addition and removal during development. In: Hershey J W B, Sonenberg N, Mathews M, editors. Translational control. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 481–503. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Robinow S, Campos A R, Yao K M, White K. The elav gene product of Drosophila, required in neurons, has three RNP consensus motifs. Science. 1988;242:1570–1572. doi: 10.1126/science.3144044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rosenthal E, Tansey T R, Ruderman J V. Sequence-specific adenylations and deadenylations accompany changes in the translation of maternal messenger RNA after fertilization of Spisula oocytes. J Mol Biol. 1983;25:309–327. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(83)80087-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sachs A B, Sarnow P, Hentze M W. Starting at the beginning, middle, and end: translation initiation in eukaryotes. Cell. 1997;89:831–838. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80268-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sagata N. What does Mos do in oocytes and somatic cells? Bioessays. 1997;19:13–21. doi: 10.1002/bies.950190105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sagata N, Daar I, Oskarsson M, Showalter S D, Vande Woude G F. The product of the mos proto-oncogene as a candidate “initiator” for oocyte maturation. Science. 1989;245:643–646. doi: 10.1126/science.2474853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Salles F J, Lieberfarb M E, Wreden C, Gergen J P, Strickland S. Coordinate initiation of Drosophila development by regulated polyadenylation of maternal messenger RNAs. Science. 1994;266:1996–1999. doi: 10.1126/science.7801127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schisa J A, Strickland S. Cytoplasmic polyadenylation of Toll mRNA is required for dorsal-ventral patterning in Drosophila embryogenesis. Development. 1998;125:2995–3003. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.15.2995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Seydoux G. Mechanisms of translational control in early development. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1996;6:555–561. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(96)80083-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sheets M D, Fox C A, Hunt T, Vande Woude G, Wickens M. The 3′-untranslated regions of c-mos and cyclin mRNAs stimulate translation by regulating cytoplasmic polyadenylation. Genes Dev. 1994;8:926–938. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.8.926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sheets M D, Wu M, Wickens M. Polyadenylation of c-mos mRNA as a control point in Xenopus meiotic maturation. Nature. 1995;374:511–516. doi: 10.1038/374511a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Simon R, Richter J D. Further analysis of cytoplasmic polyadenylation in Xenopus embryos and identification of embryonic cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-binding proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:7867–7875. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.12.7867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Simon R, Tassan J P, Richter J D. Translational control by poly(A) elongation during Xenopus development: differential repression and enhancement by a novel cytoplasmic polyadenylation element. Genes Dev. 1992;6:2580–2591. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.12b.2580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Simon R, Wu L, Richter J D. Cytoplasmic polyadenylation of activin receptor mRNA and the control of pattern formation in Xenopus development. Dev Biol. 1996;179:239–250. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Stebbins-Boaz B, Hake L E, Richter J D. CPEB controls the cytoplasmic polyadenylation of cyclin, Cdk2 and c-mos mRNAs and is necessary for oocyte maturation in Xenopus. EMBO J. 1996;15:2582–2592. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Stebbins-Boaz B, Richter J D. Multiple sequence elements and a maternal mRNA product control cdk2 RNA polyadenylation and translation during early Xenopus development. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5870–5880. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.9.5870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Stebbins-Boaz B, Richter J D. Translational control during early development. Crit Rev Eukaryotic Gene Expression. 1997;7:73–94. doi: 10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v7.i1-2.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Steward O. mRNA localization in neurons: a multipurpose mechanism? Neuron. 1997;18:9–12. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)80041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Steward O, Levy W B. Preferential localization of polyribosomes under the base of dendritic spines in granule cells of the dentate gyrus. J Neurosci. 1982;2:284–291. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.02-03-00284.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.St. Johnston D, Nusslein-Volhard C. The origin of pattern and polarity in the Drosophila embryo. Cell. 1992;24:201–219. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90466-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Struhl G. Differing strategies for organizing anterior and posterior body pattern in Drosophila embryos. Nature. 1989;338:741–744. doi: 10.1038/338741a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Stutz A, Conne B, Huarte J, Gubler P, Volkel V, Flandin P, Vassalli J D. Masking, unmasking, and regulated polyadenylation cooperate in the translational control of a dormant mRNA in mouse oocytes. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2535–2548. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.16.2535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Stutz A, Huarte J, Gubler P, Conne B, Belin D, Vassalli J D. In vivo antisense oligodeoxynucleotide mapping reveals masked regulatory elements in an mRNA dormant in mouse oocytes. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1759–1767. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.4.1759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Swiderski R E, Richter J D. Photocrosslinking of proteins to maternal mRNA in Xenopus oocytes. Dev Biol. 1988;128:349–358. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90297-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Taieb R, Thibier C, Jessus C. On cyclins, oocytes, and eggs. Mol Reprod Dev. 1997;48:397–411. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199711)48:3<397::AID-MRD14>3.0.CO;2-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tay, J., and J. D. Richter. 1998. Unpublished observations.

- 90.Temeles G L, Schultz R M. Transient polyadenylation of a maternal mRNA following fertilization of mouse eggs. J Reprod Fertil. 1997;109:223–228. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1090223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Tiedge H, Brosius J. Translational machinery in dendrites of hippocampal neurons in culture. J Neurosci. 1994;16:7171–7181. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-22-07171.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Timchenko L T, Miller J W, Timchenko N A, DeVore D R, Datar K V, Lin L, Roberts R, Caskey C T, Swanson M S. Identification of a (CUG)n triplet repeat RNA-binding protein and its expression in myotonic dystrophy. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:4407–4414. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.22.4407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Varnum S M, Hurney C A, Wormington W M. Maturation-specific deadenylation in Xenopus oocytes requires nuclear and cytoplasmic factors. Dev Biol. 1992;153:283–290. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90113-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Varnum S M, Wormington W M. Deadenylation of maternal mRNAs during Xenopus oocyte maturation does not require specific cis-sequences: a default mechanism for translational control. Genes Dev. 1990;4:2278–2286. doi: 10.1101/gad.4.12b.2278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Vassalli J D, Huarte J, Belin D, Gubler P, Vassalli A, O’Connell M L, Parton L A, Rickles R J, Strickland S. Regulated polyadenylation controls mRNA translation during meiotic maturation of mouse oocytes. Genes Dev. 1989;3:2163–2171. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.12b.2163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Verrotti A C, Strickland S. Oocyte selection of mutations affecting cytoplasmic polyadenylation of maternal mRNAs. Mol Reprod Dev. 1997;46:482–488. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2795(199704)46:4<482::AID-MRD6>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Verrotti A C, Thompson S R, Wreden C, Strickland S, Wickens M. Evolutionary conservation of sequence elements controlling cytoplasmic polyadenylylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9027–9032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.17.9027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Voeltz G K, Steitz J A. AUUUA sequences direct mRNA deadenylation uncoupled from decay during Xenopus early development. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7537–7545. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Wahle E, Keller W. The biochemistry of 3′-end cleavage and polyadenylation of messenger RNA precursors. Annu Rev Biochem. 1992;61:419–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.61.070192.002223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Walker J, Carnall N, Hake L, Richter J, Standart N. The clam 3′ UTR masking element-binding protein p82 is a member of the CPEB family. RNA. 1999;5:14–26. doi: 10.1017/s1355838299981219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Webster P J, Liang L, Berg C A, Lasko P, Macdonald P M. Translational repressor bruno plays multiple roles in development and is widely conserved. Genes Dev. 1997;11:2510–2521. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.19.2510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wells S E, Hillner P E, Vale R D, Sachs A B. Circularization of mRNA by eukaryotic translation initiation factors. Mol Cell. 1998;2:135–140. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80122-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.West M F, Verrotti A C, Salles F J, Tsirka S E, Strickland S. Isolation and characterization of two novel, cytoplasmically polyadenylated, oocyte-specific, mouse maternal RNAs. Dev Biol. 1996;175:132–141. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1996.0101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wharton R P, Struhl G. RNA regulatory elements mediate control of Drosophila body pattern by the posterior morphogen nanos. Cell. 1991;67:955–967. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90368-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wickens M, Kimble J, Strickland S. Translational control of developmental decisions. In: Hershey J W B, Sonenberg N, Mathews M, editors. Translational control. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1996. pp. 441–450. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Wormington W M, Searfoss A M, Hurney C A. Overexpression of poly(A) binding protein prevents maturation-specific deadenylation and translational inactivation in Xenopus oocytes. EMBO J. 1996;15:900–909. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Wreden C, Verrotti A C, Schisa J A, Lieberfarb M E, Strickland S. Nanos and pumilio establish embryonic polarity in Drosophila by promoting posterior deadenylation of hunchback mRNA. Development. 1997;124:3015–3023. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.15.3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Wu L, Good P J, Richter J D. The 36-kilodalton embryonic-type cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-binding protein in Xenopus laevis is ElrA, a member of the ELAV family of RNA-binding proteins. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6402–6409. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Wu L, Wells D, Tay J, Mendis D, Abbot M A, Barnitt A, Quinlan E, Heynen A, Fallon J R, Richter J D. CPEB-mediated cytoplasmic polyadenylation and the regulation of experience-dependent translation of α-CaMKII mRNA at synapses. Neuron. 1998;21:1129–1139. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80630-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Zelus B D, Giebelhaus D H, Eib D W, Kenner K A, Moon R T. Expression of the poly(A)-binding protein during development of Xenopus laevis. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:2756–2760. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.6.2756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Zhao W, Manley J L. Complex alternative RNA processing generates an unexpected diversity of poly(A) polymerase isoforms. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2378–2386. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.2378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]