Significance

Despite the robust healing potential of the liver, regenerative failure is the underlying condition of numerous liver diseases as is the case with Alagille syndrome (ALGS), a JAG1 haploinsufficient disorder characterized by neonatal liver bile duct loss that fails to regenerate in most cases. By titrating the allele dosage of jag using zebrafish, we were able to consistently model this ALGS bile duct regenerative failure and found that insufficient Jagged dampens the elevated Notch/Sox9 activity necessary for regenerating cholangiocytes to branch and segregate into a biliary network. Moreover, we found that the small-molecule Notch agonist NoRA1 can increase Sox9 expression and rescue biliary regeneration in jag mutants, thereby paving a potential therapeutic avenue for this disorder.

Keywords: ALGS, Cholangiocytes, Jag1, Sox9, zebrafish

Abstract

Despite the robust healing capacity of the liver, regenerative failure underlies numerous hepatic diseases, including the JAG1 haploinsufficient disorder, Alagille syndrome (ALGS). Cholestasis due to intrahepatic duct (IHD) paucity resolves in certain ALGS cases but fails in most with no clear mechanisms or therapeutic interventions. We find that modulating jag1b and jag2b allele dosage is sufficient to stratify these distinct outcomes, which can be either exacerbated or rescued with genetic manipulation of Notch signaling, demonstrating that perturbations of Jag/Notch signaling may be causal for the spectrum of ALGS liver severities. Although regenerating IHD cells proliferate, they remain clustered in mutants that fail to recover due to a blunted elevation of Notch signaling in the distal-most IHD cells. Increased Notch signaling is required for regenerating IHD cells to branch and segregate into the peripheral region of the growing liver, where biliary paucity is commonly observed in ALGS. Mosaic loss- and-gain-of-function analysis reveals Sox9b to be a key Notch transcriptional effector required cell autonomously to regulate these cellular dynamics during IHD regeneration. Treatment with a small-molecule putative Notch agonist stimulates Sox9 expression in ALGS patient fibroblasts and enhances hepatic sox9b expression, rescues IHD paucity and cholestasis, and increases survival in zebrafish mutants, thereby providing a proof-of-concept therapeutic avenue for this disorder.

Alagille syndrome (ALGS) is characterized by pleiotropic pathologies including congenital intrahepatic bile duct paucity, cardiac defects, distinctive facial features, delayed growth, and malformation of the eyes, bones, kidneys, and blood vessels. Cloning of this congenital disorder (1, 2) indicates compromised Notch signaling—an evolutionarily conserved pathway required for direct cell-to-cell signaling. Specifically, ALGS is associated with heterozygous loss-of-function mutations predominantly in the Notch ligand gene JAG1 (~94.3%) and less frequently in the Notch receptor gene NOTCH2 (~2.5%) (3). While multiple organ systems are affected by this disorder, cardiovascular and hepatic manifestations are the most life threatening (4). Although ALGS congenital heart defects may be repaired with multiple surgeries, there are currently no therapies that address intrahepatic biliary paucity.

Results

Defining Features of ALGS are Phenocopied by Jag1b/2b Mutant Zebrafish.

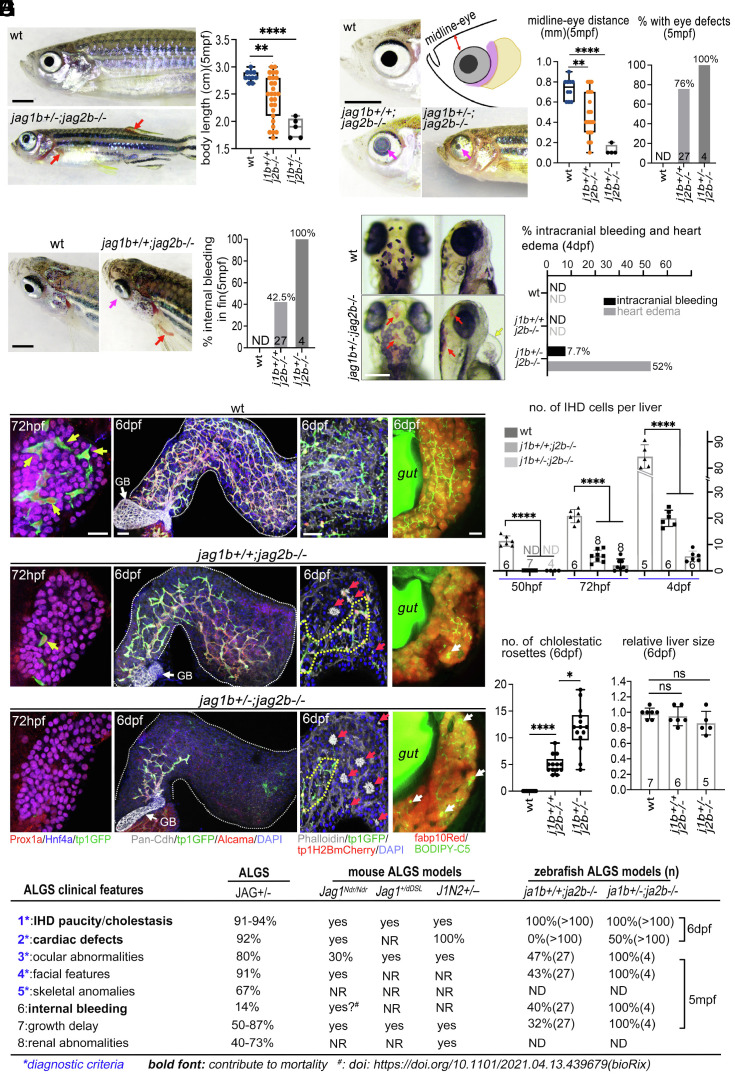

Intrahepatic cholestasis persists in most ALGS cases, contributing to a 76% mortality rate, in the absence of a liver transplant by late adolescence (5). However, spontaneous improvement of cholestasis occurs in about a quarter of children with ALGS, suggesting that postnatal regeneration of intrahepatic duct (IHD) cells is possible. With no obvious correlation between specific JAG1 mutations and clinical outcomes (6), it remains unknown how heterozygous JAG1 loss can lead to the wide range of pathological severities. To test whether varying Jagged function alone could reliably phenocopy and stratify the various ALGS pathologies, we took advantage of the multiple paralogs of jagged in zebrafish to modulate the dosage of jagged alleles that are required for IHD development. Knockdown of jag1b and jag2b previously revealed their functional redundancy in developmental specification of liver duct cells. Moreover, we demonstrated here, using double homozygous mutants, that jag1b and jag2b are required for all canonical Notch signaling and IHD cells in the zebrafish liver (7, 8), implicating these jagged paralogs for loss-of-function studies to phenocopy the distinct outcomes of IHD defects in ALGS. For this reason, an allelic series of jag1bsid24 and jag2bhu3425 (SI Appendix, Fig. S1) was analyzed (Figs. 1–3). To our surprise, loss of these jagged paralogs also resulted in additional extrahepatic ALGS-like pathologies not previously reported in zebrafish jag mutants, including eye and vascular defects. Juvenile zebrafish with homozygous jag1b mutations die before 10 dpf, exhibiting severe heart edema and craniofacial defects as previously described (9). In contrast, most homozygous jag2b zebrafish mutants are viable into adult stages but exhibit characteristic ALGS pathologies (Fig. 1 A–D). The growth of jag2b−/− mutants is markedly delayed, showing a broad range of shorter body length at 5 mpf (months postfertilization) (Fig. 1A), analogous to ALGS patients. In addition, more than 80% of jag2b−/− mutants have unilateral or bilateral ocular defects at 5 mpf, including either reduced pupils or a smaller cornea with defects in the anterior chamber (posterior embryotoxon) (Fig. 1B). Furthermore, cranial facial defects are observed in jag2b−/− mutants including a decrease in the distance from the eye to facial midline (Fig. 1B). Analogous eye and facial features are also common in ALGS (9). Moreover, spontaneous bleeding in various regions of the body, including intracranial and thoracic hemorrhaging, contributes significantly to ALGS morbidity and mortality (10, 11). In more than 40% of jag2b−/− adult mutants, internal bleeding can be visualized in the proximal region of the transparent dorsal and pectoral fins but not in wild-type (wt) controls (Fig. 1C). Spontaneous intracranial hemorrhaging is found in about 8% of the jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants at 4 dpf (when the brain is still visually accessible) but not observed in the jag2b−/− single mutants (Fig. 1D). At 4 dpf, heart edema was also obvious in approximately half of jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants, suggesting a cardiac defect (Fig. 1D). Together, this constellation of ALGS-like phenotypes suggests that zebrafish jag1b and jag2b are the functional paralogs of human JAG1.

Fig. 1.

Clinical features of Alagille syndrome are phenocopied by jag1b/2b mutant zebrafish. (A–D) Bright-field images and quantification of jag mutant zebrafish with phenotypes analogous to Alagille syndrome, including (A) reduced body length, (B) craniofacial and eye defects, and (C and D) cardiovascular defects. Magenta arrows point to abnormal eyes; red arrows indicate bleeding, and yellow arrow points to heart edema. mpf, months postfertilization; dpf, days postfertilization. Each point on graphs represents a single fish. Total sample size indicated in individual graph except D (n > 100 for each group). (E) 3D renderings of wild-type (wt) and jag1b/2b mutant zebrafish livers at specified stages. (Left) 72 hpf IHD markers: Prox1a+/tp1GFP+/Hnf4a–; hepatocyte markers: Prox1a+/Hnf4a+/fabp10Red+. Yellow arrows indicate IHD cells. (Middle, Left) 6 dpf with IHD markers: Pan-Cdh/tp1GFP/Alcama with DAPI+ nuclei show partial regeneration. (Middle, Right) 6 dpf with phalloidin+ canaliculi revealing cholestatic rosettes (red arrows) in jag1b/2b mutant livers. tp1H2BdsRed marks IHD cell nuclei. (Right) BODIPY-C5 staining reveals poor bile flow in mutants. White arrows point to bile droplets. n = 10 to 20 for each condition. GB: gallbladder. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) (F) Quantification of IHD cell number per liver from wild type and jag1b/2b mutants at indicated stages. Number of animals analyzed indicated on graph. NR: not reported, ND: not determined. (G and H) Quantification of cholestatic rosette number and relative liver size of wild type and jag1b/2b mutants at 6 dpf. (I) Table summarizing the most common phenotypes in ALGS patients and in mouse and zebrafish Jag mutant models. (Scale bars, (A–C) 2 mm and (D and E) 50 μm.) P values, *<0.05, **<0.01, ***<0.001, and ****<0.0001.

Fig. 2.

IHD regenerative outcomes stratified by jag1b+/+;2b−/− and jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants. (A) 3D renderings showing IHD cells (tp1GFP+/Alcama+) in livers of wt and jag1b/2b mutants at 8 and 11 dpf. Dotted white lines outline liver margin. (B) Number of IHD cells within a 200 × 200-μm2 area in the liver of wt and jag1b/2b mutants at 8 and 11 dpf (n = 5 to 11 for each condition). (C) Quantification of IHD branch points in the liver of wt and jag1b/2b mutants at 1 to 12 dpf (n = 5 to 11 for each condition). (D) (Left) Bright-field microscopy showing the liver (dotted yellow lines) is more opaque in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants at 12 dpf. (Middle) Confocal images of livers show IHD paucity and cholestasis in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants but not in wt at 12 dpf. Yellow circles indicate phalloidin+ cholestatic rosettes; yellow arrow indicates bile droplet; cyan arrows point to cytoplasmic cholestasis. (Right) Senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) staining shows liver damage in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants at 12 dpf. (E) Percentage of liver area with IHDs in wt and jag1b/2b mutants at 12 dpf (number of livers analyzed indicated in graph). (F) Number of SA-β-gal+ clusters per liver in wt and jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants at 12 dpf. (G) Quantification of phalloidin+ cholestatic rosettes in livers from wt and jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants at 12 dpf. (H) Survival curve of wt and jag1b/2b mutants (n = 9 to 27 for each condition in F–H). (I) (Top) EdU dosing regimen. (Bottom) 3D renderings of livers from wt and jag1b/2b mutants at 6 dpf with IHD cells labeled (tp1GFP+/Alcama+). Yellow arrows indicate EdU+ IHD cells. (J) Ratio of EdU+ IHD cells to total IHD cells per liver in wt and jag1b/2b mutants at 6 dpf (number of livers analyzed indicated in graph). (Scale bar, 50 μm.) P values, *<0.05, **<0.01, ***<0.001, and ****<0.0001.

Fig. 3.

Elevated Notch signaling drives the branching and segregation of leading IHD cells during regeneration. (A) 3D projections of jag1b/2b mutant livers at 6.5 dpf. IHD cells (pan-Cdh+/tp1GFP+/Alcama+), with area in dotted boxes magnified below, showing high tp1GFP expression in leading IHD cells (yellow arrows). Cyan dots indicate the IHD nucleus based on DAPI staining in tp1GFP+/Alcama+ cells. (B) Number of branches per leading IHD cell in jag1b/2b mutants (n = 20 to 30 leading IHD cells in 4 to 6 animals analyzed). (C) A color-coded image of confocal 3D projections showing the tp1GFP intensity in regenerating leading IHD cells (yellow arrows) and trailing IHD cells (magenta arrows) of jag1b/2b mutants. (D) Number of high tp1GFP+ leading IHD cells in jag1b/2b mutants (n = 6 to 9 livers for each genotype analyzed). (E) (Top) GSI (gamma-secretase inhibitor), LY411575 (LY; 10 μM) treatment regimen. (Bottom) 3D projections of the proximal liver in control Jag1b/2b morphants and morphants with LY treatment at 5.5 dpf. Dotted lines outline the extrahepatic duct (EHD). IHD cells (tp1GFP+/Alcama+) with white arrows indicate branching leading IHD cells in control morphant magnified to the right, with the IHD nucleus marked with light blue dots based on DAPI in tp1GFP+ cells. (F) Number of branches per leading IHD cell in Jag1b/2b morphants with and without LY treatment (n = 6 to 9 livers). (G) 3D projections of the liver in (Top) control Jag1b/2b morphants and morphants with LY treated at 4.5 dpf and analyzed at 6.5 dpf and (Bottom) with LY treated at 4.5 dpf and washed out at 6.5 dpf and analyzed at 8.5 dpf, as indicated in (H). White arrows point to leading IHD cells (tp1GFP+/Alcama+). Panels to the right show outline of tp1GFP+ IHD cells with blue dots indicating nuclei positions (DAPI). (I) Number of branching leading IHD cells per liver with and without LY treatment at 6.5 dpf and with continuous LY treatment or drug washout at 8.5 dpf. n = 7 to 12 for each condition. (J) N3ICD (Notch3 intracellular domain) heat shock (HS) induction regimen. (K) 3D projections of the livers in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants with and without N3ICD induction at 6.5 dpf and analyzed at 7.5 dpf. Panels to the right show outline of tp1GFP+ IHD cells with blue dots indicating nuclei positions (DAPI). White arrows indicate IHD cells with elevated tp1GFP expression (high Notch activity). (L) Percentage of liver area with IHDs, and (M) number of IHD branch points within 200 × 200 μm2 in the central liver region in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants with and without NICD induction at 7.5 dpf. Number of livers analyzed are indicated in graph. (N) Model depicting normal branching and segregation of leading IHD cells with high Notch activity and clustered IHD cells with low Notch activity, which can be rescued with increased Notch activity. (Scale bars, (A, E, G, and K) 50 μm and (C) 20 μm.) P values, *<0.05, **<0.01, ***<0.001, and ****<0.0001.

Intrahepatic biliary defects are also detected in all jag1b+/+;2b−/− and jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants (Fig. 1 E–G). At 50 hpf, we found that IHD cells initially fail to be specified within the liver buds (SI Appendix, Fig. S2). As organogenesis proceeds, when IHD cells are found throughout the wt liver (72 hpf), only a few (jag1b+/+;2b−/−) or no (jag1b+/−;2b−/−) IHD cells are observed in the jagged mutant liver (Fig. 1E), indicating impaired IHD cell lineage specification, as observed in prenatal and neonatal Jag1 mutant ALGS mouse models (12, 13). By juvenile stages (6 dpf), although liver growth in both jag1b+/+;2b−/− and jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants is comparable with that in wild type, biliary paucity and cholestatic rosettes are always observed in these mutants (Fig. 1 E–H). Similar to the histology of human ALGS liver biopsies (14), absence of IHDs is observed primarily in the peripheral and distal regions of the mutant liver, while the central and proximal areas of the liver contain IHDs, although with low density (Fig. 1E). Because IHD paucity is worse in mutants with fewer copies of wt jagged (Fig. 1 E and F and SI Appendix, Fig. S2), the severity of this pathology can be attributed to the lower dosage of Jagged/Notch signaling. With a compromised IHD network, bile (assessed with a vital metabolized fluorescent lipid analog BODIPY-FL C5:0) accumulates throughout the liver, in hepatocytes, and also concentrates in the form of large lipid droplets (Fig. 1E). The locations of these lipid droplets correlate with the foci of the rosette structures formed by hepatocytes, which surround a densely packed group of phalloidin+/Mdr1+ bile canaliculi (Fig. 1E and SI Appendix, Fig. S3A) (15–17). Consistent with poor bile transport and cholestasis, gallbladders in both jag1b+/+;2b−/− and jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants are smaller and less expanded (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 A and B), a pathology also commonly found in ALGS infants (18, 19). Taken together, these jagged mutant zebrafish exhibit the most defining features of ALGS, demonstrating the functional conservation of these genes and, therefore, the reliability of these mutants as a model for investigating the pathomechanism of this disorder (Fig. 1I) (4).

Regenerated IHD Cells Proliferate but Fail to Repopulate the Peripheral Liver to Resolve Cholestasis with Insufficient Jagged Signaling.

Notably, we find that by 11 dpf, IHD paucity in all jag1b+/+;2b−/− zebrafish mutants is almost completely resolved, consistent with the reduction of cholestatic rosettes (Fig. 2 A–C). However, with the loss of an additional wt jagged allele in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants, IHD paucity persists at 11 dpf (Fig. 2 A–C), with the peripheral areas of the liver remaining devoid of IHDs and containing cholestatic rosettes (Fig. 2D and SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Consistent with cholestasis, extensive BODIPY-FL (C5:0) accumulation in hepatocytes and in lipid droplets is prominent in the liver of jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants at 11 dpf (Fig. 2D). Furthermore, the jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutant livers appear to be more opaque with bright-field examination, suggesting liver damage (Fig. 2D). Accordingly, senescence-associated beta-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) staining reveals extensive senescence in the liver of jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants (Fig. 2 D–F) (20). Consistent with liver failure, nearly all jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants die between 14 and 20 dpf, whereas most jag1b+/+;2b−/− mutants survive beyond 30 dpf (Fig. 2H). On rare occasions, jag1b+/−;2b−/− escapers can survive beyond 1.5 mo. Although their body length is significantly smaller than that of wild type (Fig. 1A), their liver size is comparable, suggesting hepatomegaly, another clinical feature of ALGS (21). However, IHD paucity continues to persist in the distal liver of these escapers (SI Appendix, Fig. S3 G and H). Together, mutants with either one or two functional jagged alleles remaining can phenocopy and reliably stratify the distinct liver outcomes of ALGS, in which intrahepatic cholestasis can resolve in some but persists and worsens in most others (5). Thus, jag1b+/+;2b−/− and jag1b+/−;2b−/− zebrafish mutants are uniquely suited for investigation into the mechanism of how cholestasis is resolved and, more critically, how it also fails to resolve.

To explore the mechanism for the distinct outcomes of IHD recovery between these jagged mutants, we first analyzed whether compromised IHD regeneration is associated with decreased cellular proliferation. To evaluate IHD cell proliferation, EdU incorporation studies were performed from the initial to the late stage of IHD regeneration at 4, 6, and 9 dpf. Although biliary paucity is more severe in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants, the proportion of EdU+ IHD cells is markedly higher relative to jag1b+/+;2b−/− mutants and to wild type at all stages examined (Fig. 2 I and J and SI Appendix, Fig. S4). This finding is consistent with the ductular reaction observed in Jag1 mouse mutant livers (22) and in ALGS liver biopsies (4). Therefore, our findings demonstrate that in mutants with poor resolution of IHD paucity, more severe loss of jagged signaling does not compromise the proliferation of regenerating IHD cells but, instead, increase it.

Elevated Notch Activity in Leading IHD Cells is Required for their Branching and Segregation into the Peripheral Liver during Regeneration.

Given that the primary difference between these two mutants is their genetic dosage of wt jagged alleles, the downstream Notch activity in regenerating IHD cells was further examined using the canonical Notch signaling reporter line tp1:GFPum14 (23). Intriguingly, in jag1b+/+;2b−/− mutants, where robust IHD regeneration is reliably observed, we found that the intensity of tp1:GFP expression is not equivalent among regenerating IHD cells. Elevated tp1:GFP intensity was detected in the peripheral-most regenerating IHD cells (leading IHD cells hereafter) (Fig. 3 A–C and SI Appendix, Fig. S5). These leading IHD cells with higher Notch activity exhibit multiple branches extending peripherally toward the regions of the liver devoid of IHDs (Fig. 3A). In contrast, tp1:GFP intensity in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutant livers is generally lower than that in jag1b+/+;2b−/− mutants, with infrequent heightened Notch activity in leading IHD cells (Fig. 3C and SI Appendix, Fig. S6), consistent with more diminished Notch activation due to the added loss of a jag1b allele. Coincident with lower Notch activity, the leading IHD cells in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants are generally less branched. Furthermore, regenerated biliary ducts in these mutants appear thicker, with more clustered nuclei, suggesting poor segregation of the cell body into the peripheral regions of the liver (Fig. 3 A–C). These regenerative defects fail to resolve even at later stages in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants, with biliary ducts remaining thick and mostly limited in the central/proximal liver (SI Appendix, Fig. S7). These findings lead us to hypothesize that insufficient jagged signaling in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants dampens the elevation of Notch activity in leading IHD cells, compromising ductal branching and nuclear segregation into the peripheral and distal liver.

To determine whether Notch signaling regulates IHD cell branching and segregation during regeneration, we employed a transient Jag1b and Jag2b knockdown model in zebrafish. Microinjection of antisense morpholinos (MOs) targeting jag1b and jag2b mRNA leads to the initial IHD cell agenesis, as observed in jagged mutants. However, as knockdown effectiveness decreases with the expansion of the liver, endogenous jagged expression resumes, leading to a robust regeneration of the IHD cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S8 A and B) (24). Similar to the process of biliary regeneration observed in jag1b+/+;2b−/− mutants, live imaging of Jag1b/2b morphants via light-sheet microscopy show that subsequent to IHD cell division, a cellular branch elongates toward the peripheral region of the liver (SI Appendix, Fig. S8C). Subsequently, the body of the cell moves down the length of the branch, demonstrating a branching and segregation process for regenerating IHD cells to expand into the peripheral liver.

Together with the use of a gamma-secretase inhibitor (GSI), LY411575, which blocks the activation of the Notch receptor, this transient jagged loss-of-function model allows for temporal control of Notch inactivation in a model of robust IHD cell regeneration. In Jag1b/2b morphants (MO-treated animals) by 5.5 dpf, when the IHD network has partially regenerated in the proximal liver, we find that the leading IHD cells also exhibit elevated Notch activity and branching, as observed in jag1b+/+;2b−/− mutants (Fig. 3D). However, with Notch inhibition starting at 3.5 dpf, when regeneration has initiated, IHD cells are found clustered together and restricted to the proximal liver, showing lower Notch activity and a lack of ductal branches (Fig. 3 D and E). This finding using GSI in Jag1b/2b morphants suggests that Notch activation is required for the branching and segregation during IHD cell regeneration. This role of Notch is likely the same as its role in IHD cell morphogenesis, previously uncovered using GSI in the background with normal Jagged function (25).

To test whether Notch signaling continues to be required as IHD regeneration proceeds, GSI was dosed later from 4.5 to 6.5 dpf. By 6.5 dpf, biliary network regeneration is mostly complete in control morphants, with leading IHD cells showing heightened Notch activity and branches that reach into the peripheral liver. With GSI treatment, Notch activity is broadly reduced in the regenerating IHD cells, which are more clustered and restricted to the central/proximal liver and exhibit fewer ductal branches (Fig. 3F). However, following GSI washout from 6.5 to 8.5 dpf, elevated Notch activity is once again observed in IHD cells that are branched and have segregated to the leading edge of regenerated biliary network (Fig. 3 F–H). These results suggest that elevated Notch activity is required for leading IHD cells to branch and segregate into the peripheral liver during regeneration.

Our finding that clustered IHD cells branch and segregate to reestablish the biliary network with resumption of endogenously elevated Notch signaling led us to test whether the IHD cell clustering defect in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants could be rescued with exogenously activated Notch signaling. Via heat shock–induced expression of NICD (Notch intracellular domain; hsp70:N3ICD) (26) in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants, Notch activity can be increased with temporal control in animals that fail to resolve their ductal paucity. Overexpression of NICD with this transgenic line was previously reported to impair hepatocyte differentiation following hepatocyte ablation (27). With induction starting at 6.5 dpf, Notch activity (tp1:GFP intensity) was broadly increased in the jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutant liver by 7.5 dpf. Compared with heat-shocked control mutants, IHD cells in mutants with ectopic NICD expression became more segregated and branched (Fig. 3 I–L). Together with the GSI inhibition and washout results, we demonstrate that elevated Notch signaling is necessary and sufficient to enhance the branching and segregation of clustered IHD cells due to Jagged/Notch loss of function (Fig. 3M). Because GSI inhibition and NICD overexpression were not restricted to IHD cells in the liver, it remains unclear whether Notch modulation in hepatocytes indirectly affected this regenerative process. To address this issue, we next examined the function of a Notch effector gene specifically in the regenerating IHD cells.

Sox9b is a Key Notch Effector Required Cell Autonomously for Regenerating IHD Cells to Branch and Segregate into the Peripheral Liver.

To investigate the mechanism of how increased Notch signaling drives ductal branching in a Jagged loss-of-function liver, we examined the function of sox9b, the zebrafish liver ortholog of Sox9, a direct transcriptional target of Notch signaling (27, 28). Sox9 conditional knockout studies implicated its developmental role in branching of lung epithelial cells and in timing of intrahepatic biliary cell morphogenesis in mice (29–31). However, analysis of sox9b homozygous mutant zebrafish revealed a more profound role in the development of IHD cells, particularly their segregation (30). Importantly, heterozygous loss of Sox9 impairs biliary recovery in Jag1 heterozygous mice, implicating a role in IHD cell regeneration (32). Here, to determine a possible role for Sox9b during zebrafish IHD regeneration and further investigate its regenerative mechanism, we first examined its expression in jagged mutants. In both jag1b+/+;2b−/− and jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants, Sox9b is found in the nucleus of all regenerating IHD cells, consistent with its role as a transcription factor and as a marker for biliary lineage (Fig. 4A). Intriguingly, Sox9b expression is also observed in the cytoplasm of leading IHD cells in jag1b+/+;2b−/− mutants, which have robust biliary regeneration, but only nuclear in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants, which have poor biliary regeneration (Fig. 4A). No cytoplasmic expression of Sox9b was found in trailing cells in either mutant. Given that nucleocytoplasmic expression of Sox9 is associated with a greater invasive and metastatic phenotype in several epithelial cancer cells, including malignant pancreatic duct cells (33–35), these observations together suggest a role for Sox9b in regulating the cellular dynamics of leading IHD cells during regeneration.

Fig. 4.

Elevated Notch signaling functions through Sox9b to cell autonomously drive branching of IHD cells. (A) 3D projections of the livers in jag1b/2b mutants at 6 dpf with regenerating IHD cells (tp1GFP+Alcama+Sox9b+). White arrows indicate leading IHD cells, and yellow arrows indicate clustered IHD cell nuclei. Leading IHD cells are magnified to the right, with split color channels to reveal cytoplasmic Sox9b expression in regenerating but in nonregenerating mutants. (B) 3D projections of the regenerating IHD cells (Left; tp1GFP+Alcama+ and Right; tp1GFP+/tp1H2BmCherry+) in Jag1b/2b morphants in wt and sox9b−/− background at 6.5 dpf showing poor branching and nuclei segregation without Sox9b. White arrows indicate branched leading IHD cells; yellow arrows indicate clustered IHD cells. (C) Graph showing the number of branched leading IHD cells and the number of IHD cells along a 400 μm length of IHD. Number of livers analyzed are indicated in the graph. (D) 3D projections of the livers in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants with and without ectopic wtSox9b expression within regenerating IHD cells (white arrows indicate mCherry+ branching IHD cells) as noted in (E). (F) Number of ductal branches along a 200 μm length of IHD, and average IHD thickness in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants with and without ectopic wtSox9b expression. (G) Model depicting the ductal branching and segregation from clustered regenerating IHD cells in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants with induced increase in Sox9b expression. (Scale bar, 50 μm.) P values, *<0.05, **<0.01, ***<0.001, and ****<0.0001.

To evaluate a potential role for Sox9b in zebrafish IHD regeneration, we used MOs to transiently knock down Jag1b/2b in the sox9bfh313(loss-of-function) mutant background. At 6.5 dpf, equivalent numbers of regenerated IHD cells are detected in the liver of Jag1b/2b morphants with or without sox9bfh31 mutations, suggesting that specification and proliferation of regenerated IHD cells are not significantly compromised by sox9b loss of function (Fig. 4 B and C). However, with Sox9b loss, regenerated IHD cells remain tightly clustered and are primarily confined to the central liver, exhibiting almost no ductal branches, similar to those observed in Jag1b/2b morphants following GSI inhibition or in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants (Fig. 4 B and C and SI Appendix, Fig. S7). By 13 dpf, although complete IHD regeneration is consistently found in Jag1b/2b morphants, regenerating IHD cells in the sox9b−/− mutant background remain clustered together in the central liver, mostly lacking ductal branches (SI Appendix, Fig. S9). Importantly, high tp1:GFP intensity is observed in these clustered IHD cells, indicating that without Sox9b function, elevated Notch signaling cannot induce regenerating IHD cells to branch and segregate (Fig. 4 B and C and SI Appendix, Fig. S9B). These biliary defects are more severe than in sox9b−/− mutants, which can still form a relatively normal biliary network (SI Appendix, Fig. S10), suggesting a more critical role for sox9b in biliary regeneration than in biliary development. Together, these results implicate sox9b as a key notch transcriptional effector required for biliary cell branching and segregation during regeneration. Given that Sox9 was shown to genetically interact Jag1 in mouse (36), we propose a regenerative mechanism for Sox9 as a modifier of Jag1 haploinsufficiency.

To functionally test whether elevated Sox9b expression is cell autonomously required to stimulate effective ductal branching and segregation, we specifically manipulated Sox9b activity in a subset of regenerating IHD cells and monitored their behavior. The tp1:CreERT2 was used to conditionally induce mosaic expression of either dominant-negative Sox9b (dnSox9b) or wt Sox9b (wtSox9b) in IHD cells (ubb:loxP-CFP-loxP-dnsox9b-2A-mCherry (Switch2dnSox9b hereafter)and ubb:loxP-CFP-loxP-wtSox9b-2A-mCherry (Switch2wtSox9b hereafter), respectively (37)). We found that during IHD regeneration in Jag1b/2b morphants, regenerating IHD cells (tp1:GFP+) that also express dnSox9b-2A-mCherry (GFP+/mCherry+) were positionally biased and tended to cluster and localize to the proximal and medial regions of the biliary network and infrequently found in the distal (peripheral) region of the liver. Conversely, the distal region had proportionally less dnSox9b-2A-mCherry+ regenerating IHD cells (SI Appendix, Fig. S11). This finding suggests that reduced Sox9b function can compromise regenerating IHD cell behavior by preventing branching and segregation in a cell autonomous manner. Consistent with these results, during IHD regeneration in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants, mosaic overexpression of wtSox9b-2A-mCherry in regenerating IHD cells (GFP+/mCherry+) results in more branching and segregation compared with that in neighboring IHD cells with no ectopic wtSox9b-2A-mCherry (GFP+ only). In addition, the wtSox9b-2A-mCherry+ cells also appear more integrated into a complex biliary network, with thinner connections (Fig. 4 D–G). These results demonstrate that increased Sox9b expression is sufficient to rescue, in a cell autonomous manner, IHD cell branching and segregation in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants.

Small-Molecule Notch Agonist Rescues Cholestasis and Survival in Jagged Mutant Zebrafish and Increases SOX9 Expression in ALGS Patient Fibroblasts.

Our Jagged/Notch/Sox9 gain-of-function rescue studies led us to explore the possibility of using a drug to stimulate Notch/Sox9b signaling to augment biliary regeneration in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants. NoRA1 is a small-molecule putative Notch agonist, which we have validated to robustly increase Notch target expression in multiple cell lines including human and mouse liver HepG2 and Hepa1c1c7 and in primary mouse liver cells and human fibroblasts (to be reported in a separate article). Most relevant to this study, we find that NoRA1 treatment also increases sox9 expression in these cells, as well as sox9b in the zebrafish liver (Fig. 5A), consistent with sox9b as a target of Notch signaling (30). To test the efficacy of NoRA1 to enhance biliary regeneration, jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants were treated with this compound starting at 4 dpf. At 6 dpf, relative to DMSO-treated jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants, NoRA1-treated mutants exhibited higher hepatic tp1:GFP intensity in the regenerating IHD cells (Fig. 5B and SI Appendix, Fig. S12), suggesting elevated Notch activity with NoRA1. Importantly, this increased tp1:GFP intensity with NoRA1 treatment corresponded with a marked increase in small cellular sprouting along the biliary ducts (Fig. 5 B and C), suggesting an initiation of IHD branching. By 12 dpf, following three doses of NoRA1 treatment, a striking increase in IHD cell segregation and peripheral coverage was observed in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutant livers, indicating a rescue of biliary paucity (Fig. 5 D and E). Furthermore, the number and size of cholestatic rosettes in the livers of NoRA1-treated mutants were significantly decreased (Fig. 5 D–F), suggesting a rescue of cholestasis. Moreover, we find that a single dose of NoRA1 treatment at 4 dpf can yield a threefold increase in the survival of jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants to 3 mpf (Fig. 5G). Together, these studies provide proof-of-concept data demonstrating that biliary regeneration failure in a jagged mutant ALGS model (with only one wt jagged allele remaining) can be augmented with a Notch agonist molecule, resolving biliary paucity and cholestasis.

Fig. 5.

Small-molecule elevation of Notch/Sox9 signaling can rescue regenerative failure in jag1b/2b mutants. (A) Whole-mount in situ hybridization of sox9b in wild-type zebrafish at 4.5 dpf with and without NoRA1 (100 μM) treatment for 6 h. sox9b expression is increased in livers (L; outlined in red) of NoRA1-treated animals. (B) 3D projections of IHDs in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants with and without NoRA1 treatments at 6 dpf, magnified to the right. Yellow arrows indicate sprouting ductal branches. (C) Number of branches along 400 μm length of IHDs (n = 5 to 7 animals analyzed). (D) 3D projections of the livers in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutants with or without NoRA1 treatments at 12 dpf showing increased IHDs and decreased cholestatic rosettes (yellow arrows). Dotted white line outlines liver margin. (E and F) Number of ductal branch points within 200 × 200-μm2 liver areas, and number of cholestatic rosettes in each liver in jag1b+/−;2b−/− mutant livers at 12 dpf with and without NoRA1 treatment. 3 doses of 8 h with NoRA1 at 100 μM at 4, 6, and 8 dpf were applied for (B–F). (G) 3-mo survival rate of wt and jag1b+/–;2b–/– mutants with or without a single 8-h dose of NoRA1 at 100 μM, applied at 4 dpf (n = 20 in each group and tested 3 times). (H and I) Primary IHD cells isolated from patient liver with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and cultured as organoids (Top, bright field; Bottom, IF), showing SOX9 and CK19 expression. qPCR analysis shows increased SOX9 expression with NoRA1 treatment. (J–L) IF staining of the Hccc9810 intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma cells showing higher intensity of SOX9 protein detection with NoRA1 treatment and (L) qPCR showing increased SOX9 expression with NoRA1 treatment. Cells were treated with DMSO (5 μM) or NoRA1 (5 μM) for 3 h. (M) Sox9 expression increased in fibroblasts from three individual ALGS patients (Coriell Institute, also see SI Appendix, Table S1) with a 3-h treatment of NoRA1 (5 μM). (Scale bars, (B and D) 50 μm and (H and J) 20 μm). P values, *<0.05, **<0.01, ***<0.001, and ****<0.0001.

To test whether NoRA1 can stimulate the Notch–Sox9 axis in human cholangiocytes, we isolated cholangiocytes from hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) livers and cultured them into organoids for drug treatment. These organoids express cholangiocyte markers, including SOX9 and CK19, and show increased SOX9 transcription with NoRA1 treatment (Fig. 5 H and I). Furthermore, NoRA1 treatment of Hccc9810 intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma cells (ICCs) led to increased SOX9 protein and transcripts (Fig. 5 J–L). Given that the genetic background of ALGS individuals may modify the penetrance of this haploinsufficient disorder and potentiate the efficacy of this Notch agonist, we next assessed whether NoRA1 could enhance the Notch/Sox9 pathway in cells derived from different ALGS patients. NoRA1 treatment of fibroblasts isolated from 3 ALGS patients with cholestasis significantly increased SOX9 expression in all 3 ALGS samples (SI Appendix, Table S1 and Fig. 5M). This promising finding suggests the potential of NoRA1 as a therapeutic for rescuing the Notch–Sox9 axis and augmenting intrahepatic biliary cell regeneration in ALGS.

Discussion

The variable penetrance of ALGS pathologies among patients with the same JAG1 mutation suggests that other factors may contribute to disease severity, particularly intrahepatic biliary regenerative outcomes. Consistently, the presence and severity of ALGS-like defects in Jag1 mouse mutant models are highly dependent on genetic background (13, 38). However, it is unclear whether other genetic factors contributing to ALGS outcomes are related to Notch signaling. In the RBPJ/Hnf6 double knockout model of biliary agenesis, a compensatory activation of TGFβ signaling was implicated in driving IHD cell regeneration via transdifferentiation of hepatocytes to IHD cells (39). In contrast, histological studies of ALGS livers led to the suggestion that Notch signaling plays a role in postnatal biliary repair (40). Determining the genetic mechanisms influencing the regenerative outcomes of biliary paucity, particularly due to Jag loss of function, would inform potential therapeutic strategies for cholestasis in ALGS. Our results demonstrating that varying the genetic dosage of jagged alleles alone can phenocopy and stratify the range of ALGS severities, particularly biliary paucity that fails to resolve, suggests that perturbations of other pathways are not necessary to compromise biliary regeneration. Furthermore, finding that increasing or decreasing Notch activity is sufficient to rescue or halt IHD cell regeneration, respectively, implicates insufficient Notch signaling as the primary mechanism for regenerative failure and points to Notch signaling augmentation as a therapeutic strategy to improve ALGS outcomes. Consistently, all predicted genetic modifiers of ALGS reported to date, including Rumi (13), Fringe (41), THBS2 (42), Notch2 (43), and Sox9 (36), are directly associated with the Jagged/Notch signaling pathway.

Numerous studies have uncovered diverse mechanisms employed by the liver to confer its extensive regenerative potential. The particular mechanism used for regeneration is dependent on the cause, severity, and persistence of the specific cells lost, whether it is due to normal turnover or to chemical, mechanical, or mutational damage (44–46). Therefore, liver damage/repair models that more closely mimic specific human disease conditions will be most pertinent (47, 48). Moreover, because failure to regenerate is often the basis for liver diseases, models that also mimic compromised regeneration are critical for investigating the mechanism of the regenerative defect. By varying the dosage of the jagged alleles required for IHD cell development, we found that zebrafish with just one remaining wt allele of jag1b, analogous to ALGS, have biliary paucity that fails to resolve. This model provided the opportunity to determine how regeneration is ineffective in a Jagged insufficiency condition. We discovered that as the liver continues to grow in jagged mutants, IHD cells can be specified and are able to robustly proliferate. However, due to an attenuated increase in Jagged/Notch activity during regeneration, the leading biliary cells fail to sufficiently up-regulate sox9b expression, which is required for these cells to branch and segregate into the peripheral liver. Indeed, histological examination of ALGS livers led to the suggestion that biliary paucity in the peripheral liver is a result of a lack of branching and elongation in the growing postnatal liver (14).

With different biliary paucity models due to Jagged loss, we demonstrated here that increased Notch/Sox9b signaling, resulting from both induced genetic overexpression and endogenously regulated expression, is sufficient to enhance IHD cell branching and segregation into the peripheral liver. Moreover, treatment with the putative Notch agonist, NoRA1, which can increase hepatic sox9b expression, rescues biliary paucity and cholestasis and increases the survival of jagged mutants that normally fail to regenerate. Promisingly, this small molecule can also enhance SOX9 expression in three unrelated ALGS patient fibroblasts, suggesting that Notch/Sox9 can be enhanced in distinct genetic backgrounds.

To understand and potentially influence the outcome of ALGS, it is important to consider that a wt JAG1 allele is still available and continues to contribute to Notch signaling in this haploinsufficient disorder. This remaining, but compromised, Jagged/Notch activity is likely why postnatal fluctuations in cholestasis severity are common in ALGS patients (49). Also common for ALGS is the partial and variable penetrance of pathologies among family members with the same JAG1 mutation and even between identical twins (50–52), suggesting that outcomes in ALGS are highly sensitive to perturbations. Together with our functional studies demonstrating that tweaking Notch signaling, or its transcriptional effector Sox9b, can sway the regenerative outcome of biliary paucity, we suggest that Notch signaling in ALGS is stochastically (53) teetering between insufficiency and sufficiency. For these reasons, we propose that a mild augmentation of postnatal Notch signaling, potentially with a Notch agonist, will be enough to nudge this pathway to sufficiency and rescue biliary paucity and cholestasis in ALGS.

Materials and Methods

Animal Care and Zebrafish Lines.

Adult zebrafish and embryos were cared for and maintained under standard conditions. All research activities involving zebrafish were reviewed and approved by the SBP Medical Discovery Institute Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Zebrafish mutants analyzed sox9bfh313 (30), jag2bhu3425 (54), and jag1bsid24 (generated here via CRISPR/Cas9, gRNA targeting sequence: taaagccatcaccggcgtacggg) (SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Transgenic zebrafish analyzed Tg(Tp1bglob:eGFP)um14 (23), abbreviated as tp1:GFP; Tg(T2KTp1bglob:hmgb1-mCherry)jh11(23), abbreviated as tp1:H2BmCherry; Tg(UBB:loxP-EGFP-STOP-loxP-mCherry)cz1701 (55); Tg(fabp10:DsRed)gz15 (56); Tg(hsp70l:canotch3-EGFP)co17 (26), abbreviated as HS:NICD-GFP; Tg(tp1:CreERT2)s959 (57); Tg(ubb:loxP-CFP-stop-loxP-Sox9b-2A-mCherry)jh47 (37), abbreviated as SWITCH-wtSox9b-mCherry; and Tg(ubb:loxP-CFP-loxP-trSox9b-stop-2A-mCherry)jh48 (37), abbreviated as SWITCH-dnSox9b-mCherry.

Cre/loxP-Mediated Induction of wtSox9b and dnSox9b.

Tg(tp1:CreERT2) larvae containing the ubb:loxP-CFP-loxP-wtSox9b-2A-mCherry or ubb:loxP-CFP-loxP-dnSox9b-2A-mCherry either in Jag1b/2b morphants or in jag1b/2b mutants were treated with 20 µM 4-OHT from 4 to 5 dpf for 24 h. The larvae were fixed at 6 dpf and processed for immunostaining and analysis.

Immunofluorescence (IF) Staining and In Situ Hybridization.

Whole-mount in situ hybridization was performed as previously described using the sox9b probe (30). IF on whole-mount animals or cryosections was performed as previously described (58) (59). Antibodies used include rabbit anti-Prox1a (1:100, GTX128354; GeneTex), goat anti-Hnf4a (1:50, sc6556; Santa Cruz), mouse anti-Alcama (1:20, zn-8; DSHB), rabbit anti-pan-Cadherin (1:5,000; Sigma), mouse anti-Mdr1 (1:300, sc-71557; Santa Cruz), mouse anti-Anxa4 (1:100, ab71286, aka 2F11; Abcam) (8), chicken anti-GFP (1:300, GFP1010; Aves Labs), goat anti-mCherry (1:500, LS-C204207; LSBio), rabbit anti-Sox9b (1:100; gift from Mizuki Azuma at the University of Kansas), rabbit anti-Cytokeratin 19 (CK19) (1:100; ET1601-6; HUABIO), and rabbit anti-SOX9 (1:100; ET1611-56; HUABIO).

Supplementary Material

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Acknowledgments

We thank the zebrafish research community for the numerous reagents shared and members of our laboratory for critical discussions. This work was supported by funds from the W. M. Keck Foundation (2017-01) and the National Institutes of Health (DP2DK098092, U01DK105541, R01DK134099, and R01DK124583) to P.D.S.D., The Larry L. Hillblom Foundation Fellowship (#2019-D-013-FEL) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82270542) to C.Z., the Diabetes Research Connection (project #08) to J.J.L., and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81872068) to C.C.

Author contributions

C.Z., A.G., C.C., B.D., and P.D.S.D. designed research; C.Z., J.M., J.J.L., L.L., C.X., S.K., K.P.G., J. He, J. Huisken, and Z.L. performed research; M.A. contributed new reagents/analytic tools; C.Z., J.M., J.J.L., and P.D.S.D. analyzed data; and C.Z., J.M., J.J.L., and P.D.S.D. wrote the paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interest.

Footnotes

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. H.J.-N. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

Data, Materials, and Software Availability

All essential data, analytical methods, and study materials will be made available to other researchers. All study data are included in the main text and SI Appendix.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Li L., et al. , Alagille syndrome is caused by mutations in human Jagged1, which encodes a ligand for Notch1. Nat. Genet. 16, 243–251 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oda T., et al. , Mutations in the human Jagged1 gene are responsible for Alagille syndrome. Nat. Genet. 16, 235–242 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gilbert M. A., Loomes K. M., Alagille syndrome and non-syndromic paucity of the intrahepatic bile ducts. Transl. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 6, 22 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Emerick K. M., et al. , Features of Alagille syndrome in 92 patients: Frequency and relation to prognosis. Hepatology 29, 822–829 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamath B. M., et al. , Outcomes of childhood cholestasis in alagille syndrome: Results of a multicenter observational study. Hepatol. Commun. 4, 387–398 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spinner N. B., et al. , Jagged1 mutations in alagille syndrome. Hum. Mutat. 17, 18–33 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lorent K., et al. , Inhibition of Jagged-mediated Notch signaling disrupts zebrafish biliary development and generates multi-organ defects compatible with an Alagille syndrome phenocopy. Development 131, 5753–5766 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang D., et al. , Endoderm Jagged induces liver and pancreas duct lineage in zebrafish. Nat. Commun. 8, 769 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zuniga E., Stellabotte F., Crump J. G., Jagged-Notch signaling ensures dorsal skeletal identity in the vertebrate face. Development 137, 1843–1852 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kamath B. M., et al. , Vascular anomalies in Alagille syndrome: A significant cause of morbidity and mortality. Circulation 109, 1354–1358 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lykavieris P., Crosnier C., Trichet C., Meunier-Rotival M., Hadchouel M., Bleeding tendency in children with Alagille syndrome. Pediatrics 111, 167–170 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Andersson E. R., et al. , Mouse model of Alagille syndrome and mechanisms of Jagged1 missense mutations. Gastroenterology 154, 1080–1095 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thakurdas S. M., et al. , Jagged1 heterozygosity in mice results in a congenital cholangiopathy which is reversed by concomitant deletion of one copy of Poglut1 (Rumi). Hepatology 63, 550–565 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Libbrecht L., et al. , Peripheral bile duct paucity and cholestasis in the liver of a patient with Alagille syndrome: Further evidence supporting a lack of postnatal bile duct branching and elongation. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 29, 820–826 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellis J. L., et al. , Zebrafish abcb11b mutant reveals strategies to restore bile excretion impaired by bile salt export pump deficiency. Hepatology 67, 1531–1545 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagore N., Howe S., Boxer L., Scheuer P. J., Liver cell rosettes: Structural differences in cholestasis and hepatitis. Liver 9, 43–51 (1989). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Song J. Y., Van Noorden C. J., Frederiks W. M., Rearrangement of hepatocellular F-actin precedes the formation of rosette-like structures in parenchyma of cholestatic rat liver. Hepatology 27, 765–771 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Han S., et al. , Imaging findings of Alagille syndrome in young infants: Differentiation from biliary atresia. Br. J. Radiol. 90, 20170406 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho H. H., et al. , Ultrasonography evaluation of infants with Alagille syndrome: In comparison with biliary atresia and neonatal hepatitis. Eur. J. Radiol. 85, 1045–1052 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.So J., et al. , Attenuating the epidermal growth factor receptor-extracellular signal-regulated kinase-sex-determining region Y-Box 9 axis promotes liver progenitor cell-mediated liver regeneration in zebrafish. Hepatology 73, 1494–1508 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Subramaniam P., et al. , Diagnosis of Alagille syndrome-25 years of experience at King’s college hospital. J. Pediatr. Gastroenterol. Nutr. 52, 84–89 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Loomes K. M., et al. , Bile duct proliferation in liver-specific Jag1 conditional knockout mice: Effects of gene dosage. Hepatology 45, 323–330 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Parsons M. J., et al. , Notch-responsive cells initiate the secondary transition in larval zebrafish pancreas. Mech. Dev. 126, 898–912 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao C., et al. , Intrahepatic cholangiocyte regeneration from an Fgf-dependent extrahepatic progenitor niche in a zebrafish model of Alagille syndrome. Hepatology 75, 567–583 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lorent K., Moore J. C., Siekmann A. F., Lawson N., Pack M., Reiterative use of the Notch signal during zebrafish intrahepatic biliary development. Dev. Dyn. 239, 855–864 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang Y., Pan L., Moens C. B., Appel B., Notch3 establishes brain vascular integrity by regulating pericyte number. Development 141, 307–317 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Russell J. O., Ko S., Monga S. P., Shin D., Notch inhibition promotes differentiation of liver progenitor cells into hepatocytes via sox9b repression in zebrafish. Stem Cells Int. 2019, 8451282 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zong Y., et al. , Notch signaling controls liver development by regulating biliary differentiation. Development 136, 1727–1739 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rockich B. E., et al. , Sox9 plays multiple roles in the lung epithelium during branching morphogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, E4456–E4464 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Delous M., et al. , Sox9b is a key regulator of pancreaticobiliary ductal system development. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002754 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Antoniou A., et al. , Intrahepatic bile ducts develop according to a new mode of tubulogenesis regulated by the transcription factor SOX9. Gastroenterology 136, 2325–2333 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Adams J. M., et al. , Sox9 is a modifier of the liver disease severity in a mouse model of Alagille syndrome. Hepatology 71, 1331–1349 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sumita Y., et al. , Cytoplasmic expression of SOX9 as a poor prognostic factor for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oncol. Rep. 40, 2487–2496 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chakravarty G., et al. , Prognostic significance of cytoplasmic SOX9 in invasive ductal carcinoma and metastatic breast cancer. Exp. Biol. Med. (Maywood). 236, 145–155 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang L., et al. , Ductal pancreatic cancer modeling and drug screening using human pluripotent stem cell- and patient-derived tumor organoids. Nat. Med. 21, 1364–1371 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Adams J. M., et al. , Sox9 is a modifier of the liver disease severity in a mouse model of Alagille syndrome. Hepatology 71, 1331–1349 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Huang W., et al. , Sox9b is a mediator of retinoic acid signaling restricting endocrine progenitor differentiation. Dev. Biol. 418, 28–39 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xue Y., et al. , Embryonic lethality and vascular defects in mice lacking the Notch ligand Jagged1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 8, 723–730 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schaub J. R., et al. , De novo formation of the biliary system by TGFbeta-mediated hepatocyte transdifferentiation. Nature 557, 247–251 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fabris L., et al. , Analysis of liver repair mechanisms in Alagille syndrome and biliary atresia reveals a role for Notch signaling. Am. J. Pathol. 171, 641–653 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ryan M. J., et al. , Bile duct proliferation in Jag1/fringe heterozygous mice identifies candidate modifiers of the Alagille syndrome hepatic phenotype. Hepatology 48, 1989–1997 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tsai E. A., et al. , THBS2 is a candidate modifier of liver disease severity in Alagille syndrome. Cell Mol. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2, 663–675.e662 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.McCright B., Lozier J., Gridley T., A mouse model of Alagille syndrome: Notch2 as a genetic modifier of Jag1 haploinsufficiency. Development 129, 1075–1082 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alison M. R., The many ways to mend your liver: A critical appraisal. Int. J. Exp. Pathol. 99, 106–112 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bankaitis E. D., Ha A., Kuo C. J., Magness S. T., Reserve stem cells in intestinal homeostasis and injury. Gastroenterology 155, 1348–1361 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ko S., Russell J. O., Molina L. M., Monga S. P., Liver progenitors and adult cell plasticity in hepatic injury and repair: Knowns and unknowns. Annu. Rev. Pathol. 15, 23–50 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Forbes S. J., Newsome P. N., Liver regeneration - mechanisms and models to clinical application. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 13, 473–485 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Raven A., et al. , Cholangiocytes act as facultative liver stem cells during impaired hepatocyte regeneration. Nature 547, 350–354 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mouzaki M., et al. , Early life predictive markers of liver disease outcome in an International, multicentre cohort of children with Alagille syndrome. Liver Int. 36, 755–760 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Izumi K., et al. , Discordant clinical phenotype in monozygotic twins with Alagille syndrome: Possible influence of non-genetic factors. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 170A, 471–475 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kamath B. M., Krantz I. D., Spinner N. B., Heubi J. E., Piccoli D. A., Monozygotic twins with a severe form of Alagille syndrome and phenotypic discordance. Am. J. Med. Genet. 112, 194–197 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ziesenitz V. C., Loukanov T., Glaser C., Gorenflo M., Variable expression of Alagille syndrome in a family with a new JAG1 gene mutation. Cardiol. Young 26, 164–167 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaern M., Elston T. C., Blake W. J., Collins J. J., Stochasticity in gene expression: From theories to phenotypes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 6, 451–464 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kettleborough R. N., et al. , A systematic genome-wide analysis of zebrafish protein-coding gene function. Nature 496, 494–497 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mosimann C., et al. , Ubiquitous transgene expression and Cre-based recombination driven by the ubiquitin promoter in zebrafish. Development 138, 169–177 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wan H., et al. , Analyses of pancreas development by generation of gfp transgenic zebrafish using an exocrine pancreas-specific elastaseA gene promoter. Exp. Cell Res. 312, 1526–1539 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ninov N., et al. , Metabolic regulation of cellular plasticity in the pancreas. Curr. Biol. 23, 1242–1250 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dong P. D., et al. , Fgf10 regulates hepatopancreatic ductal system patterning and differentiation. Nat. Genet. 39, 397–402 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lancman J. J., et al. , Specification of hepatopancreas progenitors in zebrafish by hnf1ba and wnt2bb. Development 140, 2669–2679 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix 01 (PDF)

Data Availability Statement

All essential data, analytical methods, and study materials will be made available to other researchers. All study data are included in the main text and SI Appendix.