Abstract

Our ancestors acquired morphological, cognitive and metabolic modifications that enabled humans to colonize diverse habitats, develop extraordinary technologies and reshape the biosphere. Understanding the genetic, developmental and molecular bases for these changes will provide insights into how we became human. Connecting human-specific genetic changes to species differences has been challenging owing to an abundance of low-effect size genetic changes, limited descriptions of phenotypic differences across development at the level of cell types and lack of experimental models. Emerging approaches for single-cell sequencing, genetic manipulation and stem cell culture now support descriptive and functional studies in defined cell types with a human or ape genetic background. In this Review, we describe how the sequencing of genomes from modern and archaic hominins, great apes and other primates is revealing human-specific genetic changes and how new molecular and cellular approaches — including cell atlases and organoids — are enabling exploration of the candidate causal factors that underlie human-specific traits.

Subject terms: Evolutionary genetics, Development, Neuroscience

In this Review, the authors discuss our latest understanding of evolutionary genetic changes that are specific to humans, which might endow uniquely human traits and capabilities. They describe how new cellular and molecular approaches are helping to decipher the functional implications of these human-specific changes.

Introduction

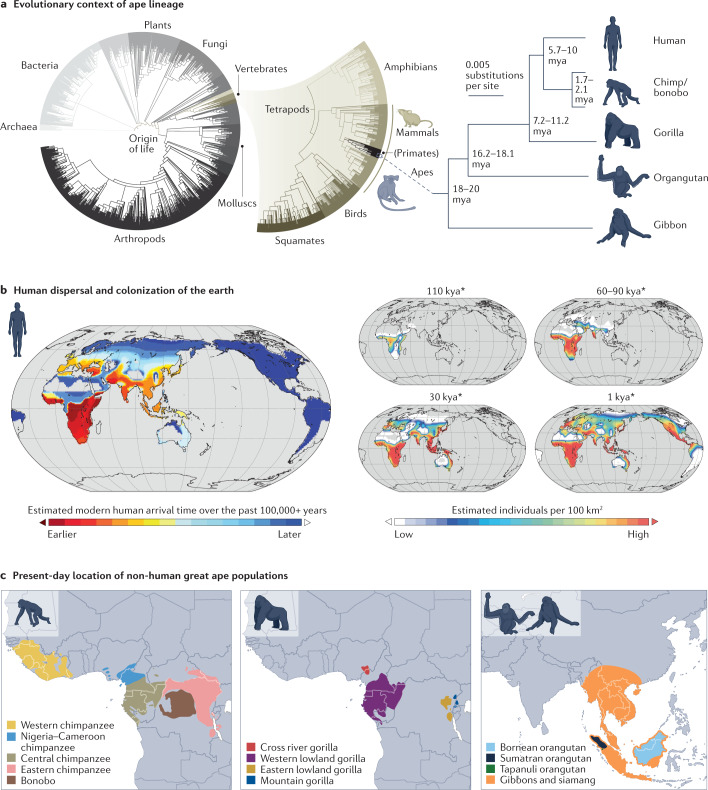

In the past 6–15 million years, as our species began to diverge from the lineages of our closest living relatives, chimpanzees and other great apes, our ancestors acquired the genetic changes that led to the modern human condition1 (Fig. 1a). Over the past 100,000 years, anatomically modern humans migrated across and out of the African landmass to colonize nearly every habitat around the world. Human populations have diversified, exploded in number and adapted to local conditions over this time period2,3 (Fig. 1b). By contrast, our closest great ape relatives are endangered or critically endangered, occupying small areas in central and west Africa and islands in Southeast Asia (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1. Humans have diverged from the other great apes, colonized diverse habitats and exploded in population.

a, Cellular organism superfamilies in the tree of life, as organized by the NCBI Taxonomy database (left), illustrate the recent emergence of apes. Over the past 20 million years, the ape lineage has split multiple times, giving rise to present-day gibbon, orangutan, gorilla, chimpanzee/bonobo and human populations. We depict the ape phylogeny with branches scaled by substitutions per site and we include divergence time estimates (right)322. b, Human populations have expanded across the world, colonizing diverse ecosystems over the past 100,000 years. Time scales are approximate and under continuous debate323, as indicated by the asterisk (*). c, Several populations of non-human great apes are confined to portions of central and west Africa (chimpanzee, bonobo and gorilla) and islands in Southeast Asia (orangutan and gibbon). kya, thousand years ago; mya, million years ago. Part b is reprinted from ref. 324, Springer Nature Limited. Part c is adapted from ref. 325, Springer Nature Limited.

Human population growth and the cultural accumulation of knowledge occurred during a period of dramatic change in brain structure, behaviour, life history, morphology and immune response (Fig. 2). Our ancestors’ brains tripled in size, disproportionately expanding higher-order association areas of the neocortex and prolonging periods of plasticity, contributing to behavioural flexibility4,5. Modifications to the tongue and vocal cord and their innervation, together with alterations to multiple brain circuits, contributed to the elaboration of human speech and language6,7. Human life history changed, with a reduced interbirth interval, alongside a prolonged childhood, adolescence and post-reproductive lifespan in humans compared with the other apes8,9.

Fig. 2. A selection of human-specific traits.

a–b, Pencil drawings of a juvenile orangutan (part a, left), chimpanzee and human facial (part a, right) and eye (part b) structures highlight similarities and differences between humans and closest living relatives. For example, human facial morphology changed to reduce the size of the jaw and to support rapid social communication, and changes in orbital areas around the eye together with loss of pigmentation of membranes covering the sclera in humans make the direction of eye gaze more prominent. c, Shown are an assortment of phenotypes that differ between human (grey) and chimpanzee (beige) and are associated with human specializations. Artwork in parts a and b, images courtesy of E. G. Triay. In part c, shoulder structure is reprinted from ref. 17, Springer Nature Limited; pelvis structure is adapted with permission from ref. 20, Elsevier and tongue/vocal cord structures are adapted from ref. 326, CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Human facial morphology changed to reduce the size of the jaw and to support rapid social communication10,11 (Fig. 2a). Morphological change to orbital areas around the eye together with loss of pigmentation of membranes covering the sclera in humans make the direction of eye gaze more prominent with debated implications for communication and sexual selection12,13 (Fig. 2b). Structurally, humans acquired skeletal, muscle and joint modifications that enable upright walking, movement across large distances, enhanced object grasping and projectile throwing14–18. Changes to the pelvis support upright walking and accommodate a larger cranium during childbirth19,20. Our gastrointestinal tract changed with our diet and the metabolic needs of our large brain and other organs21. The small intestine to colon volume ratio in humans has substantially increased relative to the other apes22,23. Cooking and agriculture affected the intestinal epithelium and other aspects of digestive physiology24,25. Our immune systems have been modified by pathogen encounters in ancient and modern history26–29. These numerous phenotypic changes that manifest across development suggest that each of our cells harbours modifications that sustain human physiology (Fig. 2c).

The fossil record has illuminated a diversity of hominids, revealing that many changes towards the modern human condition were gradual30–32. This gradual transition in the fossil record points to there not being a single mutation that made us human, but instead a large number of mutations, spread out over millions of years, that contributed to human specializations. DNA has been sequenced from ancient bones for some relatively recent archaic hominins (that is, Neanderthals and Denisovans), which can aid in temporally ordering the many mutations. These archaic genomes reveal a genetic exchange between hominin populations, and this exchange has left both a genetic and phenotypic legacy in many humans alive today33–35.

The overall goal of this Review is to bring the discussion of human-specific genetic and physiological changes to practical areas for functional research and highlight new tools that will enable a molecular, cellular and physiological exploration of human-specific genetics. This goal has human health relevance, as recent fixed and polymorphic genetic changes influence disease risk in several ways35. First, large changes over a short period of time may not land directly at a fitness optimum, and genetic changes that ‘fine-tune’ a trait may not have occurred or reached fixation in human populations36. Second, evolution involves trade-offs that can confer benefits but also create new vulnerabilities. Similarly, changes that were adaptive in particular environmental conditions may pose disease risks in today’s world2. These suboptimal changes and trade-offs are likely to manifest at cellular and anatomical levels and could explain why humans experience increased risk for many diseases and disorders associated with recently evolved traits, such as morphological changes to the knee and associated risks of osteoarthritis37. Third, recent genetic changes may involve loci with high mutation rates. For example, human-specific segmental duplications can create new functional coding genes but are also prone to recurrent non-allelic homologous recombination, contributing to human disease susceptibility38–41. Indeed, regions of our genome that have rapidly changed are also associated with disorders such as autism and schizophrenia42–44. Resolving the molecular changes that have led to physiological adaptations and variation among humans will help to us understand how our bodies are organized and where sources of susceptibility are located, both genetically and anatomically.

In this Review, we provide an overview of the types of molecular change that have occurred during human evolution, as revealed by comparative genomics across the great apes and studies of ancient DNA from archaic hominins, highlighting molecular changes linked to human-specific traits. We next consider experimental systems that enable functional exploration of human-specific genetics. We suggest that cell atlases from non-human primates (NHPs) will resolve human-specific cellular features. We discuss the promise and limitations of stem cell and organoid model systems that can be used to functionally examine the effects of human-specific genetic changes in controlled culture environments. We conclude by emphasizing the value of characterizing diversity within species as well as divergence between species at both the genomic and phenotypic levels.

Comparative great ape genomics

Whole-genome sequences from modern humans, archaic hominins, chimpanzees and the other apes provide a foundation for identifying similarities and differences between hominids. In addition, hundreds of mammalian genomes place human and NHP evolution into a larger mammalian context. Altogether, these genomes have enabled scientists to catalogue many human-specific genetic changes and prioritize those mutations that are likely to have functional consequences.

Genome-scale divergence between humans and our closest living relatives

Genomes from chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes)45,46, bonobo (Pan paniscus)47,48, gorilla (Gorilla gorilla, Western; Gorilla beringei, Eastern)49,50 and orangutan (Pongo abelii, Sumatran; Pongo pygmaeus, Bornean; Pongo tapanuliensis, Tapanuli)46,51,52 provide accounts of genetic changes along the human lineage (Fig. 3a). Genetic changes can arise by various mutational mechanisms and affect a large number of nucleotides or result in a single nucleotide change (SNC)45,53–55. Most genetic changes that distinguish humans from the other great apes are located in non-protein-coding regions of the genome, with only a small fraction of changes altering amino acid sequences within proteins56–58.

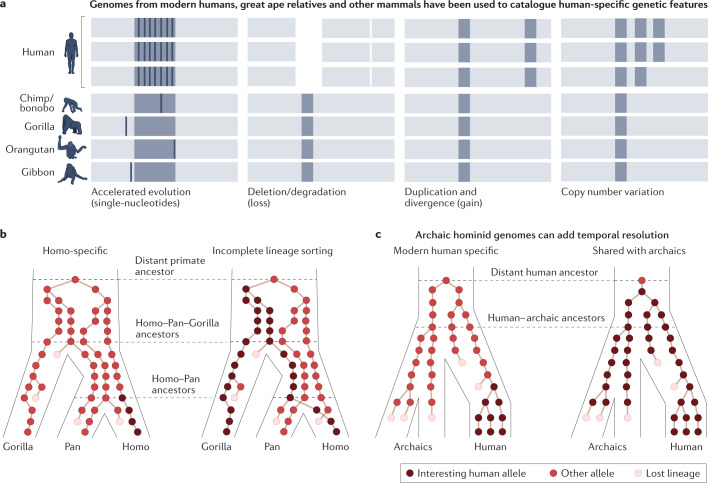

Fig. 3. Comparative great ape genomics can identify human alleles of interest.

a, Comparisons between humans, chimpanzees and other great apes, as well as other primate or mammalian outgroups have revealed distinct classes of human-specific genetic changes. Light grey block represents DNA, mid-grey represents genes or regulatory elements of interest and dark grey bars represent single nucleotide changes. b, Schematic illustrates that humans could have inherited interesting and impactful alleles that are human specific (left), or alleles shared with either chimpanzees or gorillas through incomplete lineage sorting. This implies that some of the diversity we observe in human populations has not arisen since the split with chimpanzees but rather could be far more ancient. c, Comparisons with ancient genomes from archaic hominins, such as Denisovans and Neanderthals, can help to understand the age and history of human-specific changes. Part b is adapted from ref. 327.

The most conspicuous changes in our genome that affect the largest number of base pairs involve structural changes, including a chromosome fusion event, inversions, insertions and deletions, that together influence approximately 3% of the genome45. Differences between the number of human and ape chromosomes and their banding patterns were already visible to early cytogeneticists59. The fusion of two ancestral chromosomes formed human chromosome 2, reducing the number of chromosomes in modern and likely archaic hominins, including Neanderthals and Denisovans, to 23 pairs of chromosomes60. This fusion event probably influenced gene regulation, chromosome folding or other cellular functions that affect human-specific physiology, but the functional consequences of the fusion event are still unclear. Similarly, a human-specific pericentric inversion on chromosome 1 is associated with human-specific NOTCH2NL and NBPF family genes61–63. Duplications and deletions of this locus can cause macrocephaly and microcephaly, respectively62,63.

Great ape genomes also demonstrate incomplete lineage sorting (ILS) and admixture among hominids (Fig. 3b). For example, although 64% of the genome supports a closer genetic relationship between humans and chimpanzees and more divergence with gorilla, 17% of the human genome is genetically closer to gorilla, and another 18% of the human genome is equally divergent from chimpanzee and gorilla46. ILS events between humans and the other hominids are not randomly distributed but are localized in clusters and may be explained by balancing selection, other selective forces or genetic drift. Genes within these clustered segments show a significant excess of amino acid substitutions and are associated with immunity — they contain EGF-like domains — and solute transport48. However, little is known about potential differences in protein function or gene regulation derived from DNA in these ILS locations. In addition to ILS, there have been many periods of ancient gene flow, including from bonobo to chimpanzee64, and from an extinct ‘ghost’ ape lineage to bonobo65, highlighting the potential of ape population genetics to reveal further historical exchanges. These results emphasize that future evolutionary analyses of the human genome should consider alternative topologies of the great ape phylogeny.

Comparative genomic analyses to identify human-specific changes with functional consequences

Isolating functional and adaptive genetic changes out of the millions of base pair changes that accumulated along the human lineage remains challenging. Well-assembled genomes from many primates, mammals and vertebrates46,66,67 have revealed functional genomic regions, based on cross-species sequence conservation. More than two-thirds of these conserved regions are non-coding68, and often function as cis-regulatory elements69. Conserved regions that are divergent specifically in the human genome represent strong candidate loci for influencing human-derived traits.

Recent studies have explored otherwise conserved regions that on the human lineage have been: mutated by an abundance of substitutions (human accelerated regions (HARs))70,71, deleted (human conserved deletions (hCONDELs))72, or duplicated (copy number variants (CNVs))39,46,73–75 (Fig. 3a). Many HARs and hCONDELs seem to modify cis-regulatory elements, and CNVs may also influence the transcript level of the duplicated gene. These results are consistent with the view that mutations that modulate the expression level of a gene, often at a particular stage and in a particular cell type, will be an important substrate for human evolution56–58,76. There are also examples of gene duplications followed by amino acid substitutions or splicing changes that are likely to be important for human evolution, which was also proposed as an important mechanism of evolutionary change77. These two mechanisms both reduce the pleiotropic effects of mutations. Conservation-based analyses have focused on the modification of existing functional elements; however, the origin of novel functional elements from neutrally evolving DNA could provide an even greater reduction in pleiotropic effects. Indeed, the most divergent regions of the human genome are enriched for bivalent chromatin marks indicative of gene regulatory potential across diverse cell types and anatomical locations, including a few regions where the human sequence functions as a neurodevelopmental enhancer but the sequence from the inferred human–chimpanzee ancestor does not78. Future analyses are required to reveal more examples of evolutionary changes that generate novel human-specific functional elements.

Structural changes are particularly likely to have phenotypic consequences in both coding and non-coding loci79. New technologies that enable long contiguous sequence reads (from Pacific Biosciences and Oxford Nanopore Technologies) and optical identification of long-range structural changes (from Bionano Genomics), combined with reference-free assemblies and higher quality annotations for great ape genomes46,48,80–83 can resolve complex human-specific genomic changes. These new approaches make it possible to systematically identify insertions46, deletions46, variable number tandem repeats (VNTRs)84,85 and inversions86 that arose along the human lineage. Centromeric and telomeric sequences remain particularly difficult to sequence and compare, but recent advances now enable telomere-to-telomere sequence comparisons between humans and apes40,81,87,88. These approaches will help to reveal the actual number of human–chimpanzee genetic differences and to prioritize those that influence fundamental cell biology differences between apes46,89.

Ancient DNA: archaic hominin genomes provide insight into modern human evolution

Over the past decades, innovations in extracting, purifying, sequencing and analysing ancient DNA from bones, teeth, soft tissues and archaeological sediments have enabled sequencing of short segments of mitochondrial and nuclear DNA from diverse archaic hominins and prehistoric humans90–93. High-coverage sequencing of select individuals and alignment to modern human genomes subsequently resolved genome-wide patterns of nucleotide divergence60,94,95 and revealed that early modern humans interbred with archaic hominins such as Neanderthals and Denisovans93,96,97. The prevalence of known archaic hominin DNA among humans today varies across populations, with current estimates suggesting that Denisovan ancestry ranges between 0% and 5%, highest in Melanesians and Aboriginal Australians, and Neanderthal ancestry ranges between 0% and 2.1%, with approximately 2% found in all non-Africans95,98–100. Cumulatively, it is estimated that at least 20–40% of Neanderthal DNA survives in human populations around the world101,102. These archaic genomes, along with prehistoric genomes, inform historical human migration and admixture events, highlight candidate functional mutations and help to link the timing of mutations to the fossil record (Fig. 3c).

Admixture of archaic hominin DNA into human lineages left a lasting legacy on present-day human phenotypes93,96,97. At least one-quarter of introgressed haplotypes significantly affect the expression level of at least one gene, together influencing the expression of hundreds of genes103. Neanderthal alleles98,101 are associated with skin and hair colour33,34, immune response26,104,105 (including vulnerability to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2))106, lipid metabolism107, skull shape108, bone morphology, blood coagulation, pain sensitivity109, sleep patterns and mood disorders33,34. A large proportion of alleles introgressed from Neanderthals have been selected against in modern human populations, especially those with changes in highly conserved regions and those that influence the expression of genes in the brain110,111. However, there is evidence, such as alleles with the greatest influence on gene expression also being at the highest allele frequencies in modern humans, that there may also be a collection of introgressed alleles that are advantageous in modern humans112, and this adaptive introgression may have preferentially influenced certain regions of the human body, such as adipose tissue113. In one example influencing physiology, an introgressed Denisovan allele at the EPAS1 locus that confers high-altitude adaptation persisted at low frequency as standing archaic variation and was rapidly selected in the Tibetan highlands over the past 9,000 years114.

Genomes from archaic hominins have also revealed high-frequency and fixed modern-human-specific SNCs that may influence recently evolved traits, providing enhanced temporal resolution to the origin of interesting human alleles (Fig. 3c). Most phenotypic differences between Neanderthals and modern humans are likely to be due to changes in gene regulation111. Nonetheless, recent analyses have identified candidate changes that could have functional consequences in coding genes as well as in transcription factor binding sites95. Analyses of candidate causal mutations have mainly focused on SNCs because structural genetic changes are difficult to identify in ancient DNA owing to the persistence of only short fragments. However, recent identification of multiple CNVs that were adaptively introgressed from Denisovans and Neanderthals115 underscores the need for further algorithmic improvements to detect fixed or high-frequency modern human structural changes directly using short reads from ancient DNA116,117. An intriguing subset of fixed human-specific changes are located within so-called ‘desert’ regions resistant to introgressed haplotypes from Neanderthals and Denisovans100,118,119. A proportion of these regions that also contain no evidence for ILS with archaic hominins are enriched for genes that influence brain development119, highlighting candidate loci that may harbour modern human-specific adaptations, incompatibilities with archaic humans or deleterious archaic alleles excluded from modern human genomes.

Functional genomic comparisons

Comparative genomic analyses between species can identify specific sequence changes that may influence evolved human traits. However, it is challenging to develop testable hypotheses about the molecular, cellular and organismal consequences of candidate mutations. Genetic changes can affect gene regulation by altering transcription factor binding, chromatin state, splicing, transcript degradation and translation efficiency. Similarly, genetic changes can directly influence gene function by altering the nucleotide composition of catalytic RNAs, or the amino acid composition of proteins (Fig. 4a). Functional genomic comparisons of chromatin accessibility, transcript abundance or protein levels between great ape species can provide a link between genome sequence and human-specific molecular and cellular phenotypes120,121.

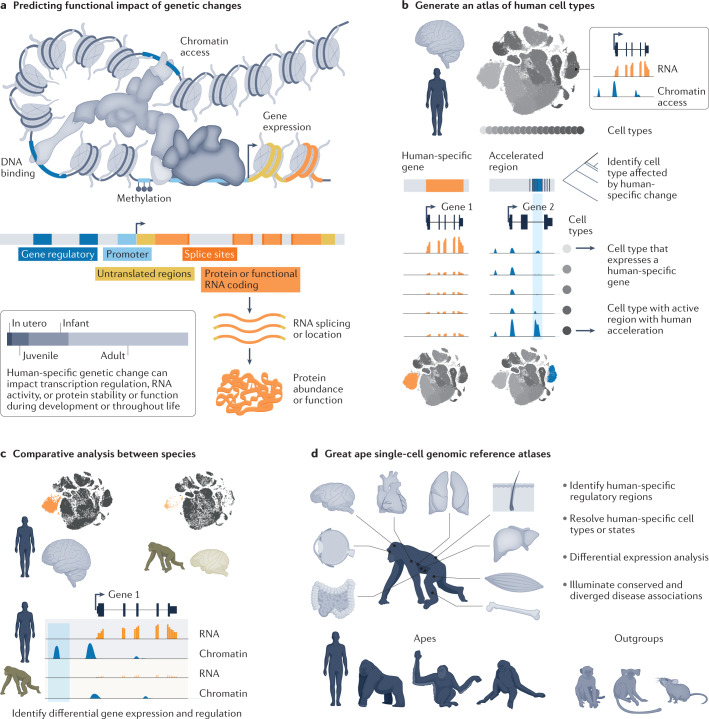

Fig. 4. Single-cell genomic atlases to map and identify human-specific features.

a, Illustration of genome organization, highlighting features that could influence gene regulation and function throughout the life cycle. b, Entire human tissues, such as the brain, can be mapped using transcriptome and chromatin accessibility measurements at the resolution of individual cells. These atlases can then be used to identify which cell types might be affected by a human-specific genetic change. c, Cell atlases can be generated from chimpanzees and other great apes, and cell types and states can be directly compared between species to identify gene and regulatory features enriched in humans. d, Cell atlas efforts across great apes, as well as primate and mammalian outgroups, promise to identify human-specific cell types and states and differential activity of genes and other genetic features.

Functional genomic comparisons reveal patterns of gene expression evolution

Comparisons of gene regulation between apes have revealed cell types and biological processes with increased transcriptional divergence, changes in the timing of developmental processes and specific genes with novel expression patterns in humans. Gene expression divergence generally correlates with phylogenetic distance, but some tissues, such as testis, show increased divergence and lineage-specific acceleration between the great apes122. Certain cell types show accelerated transcriptional divergence, such as oligodendrocytes compared with neurons in the prefrontal cortex and other parts of the brain123,124. Comparisons of gene expression in specific brain regions have also revealed accelerated divergence in developmental trajectories in humans125, including altered timing of synaptogenesis and a protracted period of myelination in humans126–128. These studies also highlight individual candidate microRNAs (miRNAs)125 and coding genes with divergent expression129 that may influence evolved human traits, and find greater overlap than expected by chance between evolutionary changes in gene regulation and genes implicated in neuropsychiatric disorders123,130.

A major challenge of comparative transcriptomic studies is to link the transcriptional differences to changes in the underlying gene regulatory elements and to causal mutations. One method to identify differences in gene regulatory elements is through comparative studies of chromatin accessibility. A recent study identified regions of differential accessibility in white adipose tissue between humans, chimpanzees and rhesus macaques131. The regions of reduced accessibility in humans are enriched for binding motifs for the NFIA transcription factor and are likely to be associated with the reduced ability to convert white into beige fat and the increased body fat percentage observed in humans. Similarly, epigenomic analysis of purified human neuron subtypes revealed concordant human-specific changes in epigenetic marks and gene expression for several hundred genes, overlap with disease-associated genes and evidence of increased constraint in enhancers with widespread activity patterns130. In the future, multi-omic studies that jointly interrogate chromatin modifications, transcript abundance, splicing and protein abundance will help to uncover the mechanisms that underlie differential expression and the resulting phenotypic differences. Coupled with advances in artificial intelligence, functional genomics datasets will enable refinement and testing of predictions of the influence of individual mutations, or many combinations from a set of mutations, across levels of gene regulation132–134.

An additional challenge of interpreting comparative transcriptomic studies is that gene expression divergence may involve various models of evolutionary change including directional or diversifying selection, or relaxation of constraint. However, owing to limited access to tissue samples, few studies have explored population-scale gene expression variation in humans and chimpanzees to distinguish these possibilities135. A recent large-scale study of human and chimpanzee post-mortem heart tissue (39 samples each) identified orthologous genes with expression levels under weak negative selection in both species and examples of genes with interspecies differences in selection pressure on their expression136. In addition, cell-type heterogeneity in tissue samples also drove the gene expression variation observed in dissected tissue within and between species, making it difficult to isolate cell-type-specific changes from composition differences. These findings underscore the value of population-scale studies, when possible, and the value of methods that enable analyses of specific cell types. Ultimately, functional genomics approaches will need to be applied at the single-cell level or in purified cell types from many individuals to disentangle species differences from cell-type variation and neutral variation from adaptive changes.

Cell atlases to map and interpret human-specific genetic features

Single-cell sequencing approaches can now identify molecularly defined cell types in tissue samples137,138. The ability to measure the transcriptome, accessible chromatin, histone modifications and other genetic and epigenetic properties enables connection of genetic features to cellular phenotypes139,140. The human cell atlas (HCA) project aims to establish a comprehensive map of all human cell types and their molecular features141,142. Resources that can help link recent genetic changes to specific cell types are already available for many human tissues143,144 (Fig. 4b). Direct comparisons between cells of the same type from human and other great ape tissues can further identify human-specific gene regulatory changes145 and potentially human-specific cell types or states129 (Fig. 4c). These comparative analyses require incorporation of analytical strategies for unbiased identification of homologous cell types and gene networks and careful consideration of gene models and alignment strategies between species146. Outside of the adult brain, few studies have compared single-cell transcriptome and epigenetic features between humans and other great apes, highlighting a future area of research. A great ape cell atlas (GACA) could be combined with other cell atlases for human, non-ape primates and diverse mammals to systematically resolve shared and divergent molecular features of defined cell types and states (Fig. 4d).

Single-cell genomic methods can illuminate developmental differences between apes

Genetic differences can affect adult tissues and cell types by acting in their precursor cells. Combining developmental and adult cell atlases will aid our understanding of both the direct effects in developmental cell populations and the ultimate consequences in the adult organism147. Multi-omic developmental atlases for primates will enable an approach reminiscent of reverse genetics whereby researchers begin their study with a human-specific mutation and use data in the multi-omic atlases to infer an associated function and tissue of action. For example, HARs overlap many predicted enhancers that are active in neural progenitor cells and immature neurons, suggesting that these recently modified elements might directly influence gene regulation during brain development and may indirectly influence compositional differences observed in the adult brain148,149.

The combination of great ape developmental and adult atlases will also enable a forward-genetics-like approach in which divergent phenotypes of cells and tissues can be identified first and then localized to the causative genetic changes. Comparisons between humans and developing NHPs, such as macaque and marmoset, and other mammals, have identified features that are relevant for human specializations including novel cell types and quantitative changes in conserved cell types. Indeed, recent comparative studies of primates and rodents have revealed several examples of primate-specific neuronal populations in the striatum150,151. Analyses of developmental gene expression trajectories and neuronal migration indicate that primate-specific cell populations can emerge either as qualitatively new initial classes of neurons early in development or through the redistribution of conserved initial classes to new locations150,151. However, neurons and their initial classes are largely conserved, even between primates and rodents150–152, suggesting that new neuron types may be rare in recent human evolution and when present may be specified later in development by altering the process of post-mitotic fate refinement150,151. Instead, recent human-specific changes may mainly involve altered gene expression in conserved cell types, a process that could be described as ‘teaching old cells new tricks’, similar to the phrase coined for the reuse of conserved genes in evolution153. Studying these recently evolved developmental gene expression changes among apes will require new experimental strategies, because human and other great ape developmental tissue samples are largely inaccessible for ethical reasons.

Models for functional studies

Thousands of genomes and many cell atlases exist to identify and map human-specific genetic features; however, it remains a major challenge to understand how these genetic changes affect human physiology. Mouse and NHP models have been the predominant systems for studying human-specific genetic change. These models enable analyses of the impacts of genetic changes on development, physiology or behaviour in a whole-organism context. In this section, we provide an overview of human-specific genetic changes that have been studied in non-human model systems and in vitro in human and ape cells (Table 1), and we highlight particular examples that link molecular and phenotypic changes.

Table 1.

Representative list of human-specific genetic changes linked to phenotypes

| Genetic feature | Type of change | Evolutionary relevance | Proposed mechanism | Phenotypic impact | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMY1 | Copy number change | Polymorphic in human populations | Higher copy number of AMY1 leads to enhanced starch degradation through amylase enzyme activity in salivary glands | Increased starch digestion capacity correlated with gene copy number and salivary amylase levels | 25 |

| AQP7 | Copy number change | Human specific | Increased water and glycerol transport | Might augment endurance running in humans | 75 |

| ARHGAP11B | Segmental duplication | Human specific | Loss of Rho GAP activity owing to a change in splice site | Basal progenitor amplification and neocortex expansion in mouse and marmoset models | 165,166,168 |

| BOLA2 | Segmental duplication | Human specific | Correlation of gene copy number with RNA expression and protein levels | Iron homeostasis and susceptibility to anaemia | 297,298 |

| CCL3L1 | Segmental duplication | Polymorphic in humans | HIV-1-suppressing chemokine | Lower copy numbers associated with AIDS susceptibility | 299 |

| CMAH | Pseudogene | Human specific | 92-bp deletion in sialic acid hydroxylase domain leads to inactivation of enzyme activity that converts CMP-Neu5Ac into CMP-Neu5Gc | Atherosclerosis predisposition; xenosialitis through circulating anti-Neu5Gc; immunological changes; changes in muscle fatigue | 182,183,300–302 |

| FOXP2 | Two single nucleotide substitutions positively selected (debated) | Human specific | Regulation of cortico-striatal circuit development | Involved in speech and language capability | 163,178,303 |

| GHRD3 | Deletion of an exon | Human specific | Growth hormone receptor gene is affected | Associated with the response to nutritional defects along the evolutionary time course | 304 |

| HACNS1 (HAR2) | Single nucleotide substitutions | Human specific | Regulates GBX2 expression (positively selected) | Associated with digit, limb and pharyngeal arch patterning | 155,159 |

| HAR1 | Single nucleotide substitutions | Human specific | Modification of the primary sequence and secondary structure of a non-coding RNA gene | Expressed in Cajal–Retzius cells and other brain regions during development | 70 |

| HYDIN2 | Segmental duplication | Human specific | Promoter modification altered tissue specificity of HYDIN2 isoforms in cerebellum and cerebral cortex | Potentially involved in neurodevelopmental disorders | 305 |

| NBPF | Oludvai/DUF1220 protein domain copy number change | Human specific | DUF1220 domain dosage-associated increase in neural stem cell proliferation | Brain size and 1q21.1 syndrome | 62,306,307 |

| NOTCH2NL | Segmental duplication | Human specific | Expressed in radial glia stem cells and tunes neuronal differentiation via NOTCH signalling | Associated with expanded neocortex, observed at breakpoints in 1q21.1 deletion/duplication syndrome | 170,171 |

| NOVA1 | Single nucleotide substitution | Modern human specific | Affecting alternative splicing during nervous system development | Altering excitatory synaptic interactions and involvement in neurological disorders | 264,308 |

| Regulatory element of AR (hCONDEL569) | Deletion of a highly conserved regulatory element | Human specific | Mouse and chimpanzee enhancer sequences drive lacZ expression in mouse model at facial vibrissae and genital tubercle | Potential regulation of AR expression by the loss of this regulatory element leading to loss of sensory vibrissae and penile spines | 72 |

| Regulatory element of CACNA1C | Large tandem repeats | Human specific | Intronic tandem repeat array of neurodevelopmental enhancer resulting in stronger gene expression in humans | Increased expression of human CACNA1C during human neurodevelopment potentially linked to bipolar disorder and schizophrenia | 44 |

| Regulatory element of CUX1 (HAR426) | Single nucleotide polymorphism | Human specific | G>A mutation within HAR426. CUX1 promoter and HAR426 interaction is likely to affect gene expression levels | Rare disease might affect dendritic spine density and synaptogenesis | 43,309 |

| Regulatory element of FZD8 (HARE5) | Human accelerated enhancer | Human specific | Developmental enhancer physically interacting with FZD8 promoter | Accelerated neural progenitor cell cycle and increased neocortex size in a mouse model | 156 |

| Regulatory element of GADD45G (hCONDEL332) | Deletion of a highly conserved regulatory element | Human specific | Mouse and chimpanzee enhancer sequences drive lacZ expression in the mouse ventral forebrain | Potential expansion of particular inhibitory neuron populations | 72 |

| Regulatory element of GDF5–UQCC locus | Single nucleotide polymorphism | Polymorphic in human populations | Chromatin accessibility profiles of joint chondrocytes reveal positively selected regulatory variants | Affecting knee shape in humans and associated with osteoarthritis risk | 37 |

| Regulatory element of LCT | Single nucleotide polymorphism | Polymorphic in human populations | Selective sweeps in the enhancer region enhance lactase expression in certain humans | Milk product digestion into adulthood (lactase persistence) and potentially other phenotypes | 24 |

| Regulatory element of PPP1R17 (HAR2635 and HAR2636) | HAR | Human specific | Chromatin contact of PPP1R17 promoter and HAR2635 and HAR2636 | Acting as neurodevelopmental enhancer that may extend cell-cycle length in humans | 148 |

| SIGLEC13 | Gene loss | Human specific | Alu-mediated recombination | Resistance to sialylated bacterial infections | 310,311 |

| SLC22A4 | Single nucleotide polymorphism | Polymorphic in human populations | Ergothioneine transporter | Crohn’s disease, rheumatoid arthritis | 312–314 |

| SLC24A5 | Single nucleotide polymorphism | Polymorphic in human populations | UV radiation-induced transporter activity | Variable skin pigmentation | 315,316 |

| SLC6A11 | Single nucleotide polymorphism | Polymorphic in human populations | Single nucleotide change in a coding region | Expressed in liver and modulating triacylglycerol metabolism, potential type 2 diabetes risk factor | 317 |

| SRGAP2 | Segmental duplication | Human specific | Rho GAP family member SRGAP2 paralogues expressed in the developing human cortex. SRGAP2B and SRGAP2C are truncated duplications that antagonize by dimerizing with the ancestral form of SRGAP2 | Affect dendritic spine density and morphology | 173,174,318 |

| TBC1D3 | Segmental duplication | Great ape specific | Affecting neural progenitor proliferation by inhibiting histone methyltransferase G9A | Cortical expansion and folding | 319,320 |

| TBXT | Intronic Alu insertion | Ape specific | Alternative splicing of TBXT | Associated with tail reduction or loss in mouse model of splicing change | 321 |

HAR, human accelerated region; hCONDEL, human conserved deletion.

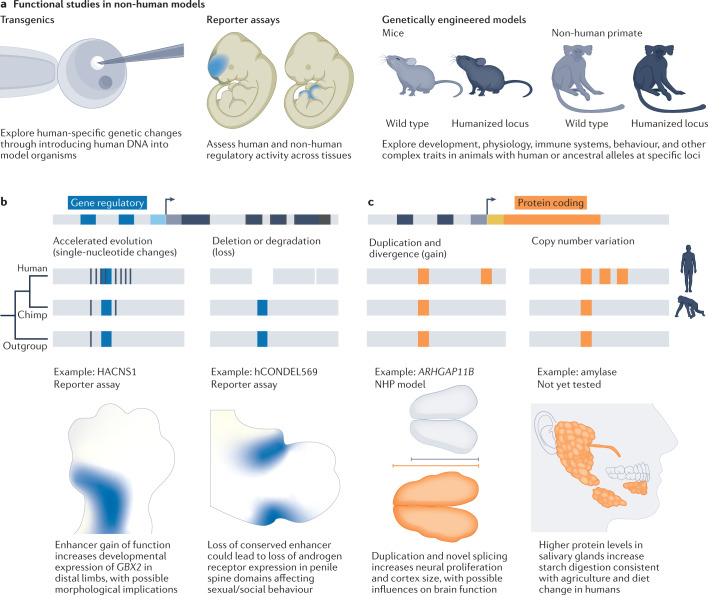

Functional studies of human-specific changes that impact gene regulation

Embryonic mouse reporter assays have been powerful systems to explore the regulatory potential of human-specific mutations in the context of an entire developing mammal69,154 (Fig. 5a). For example, mouse reporter assays showed a human-specific increase in regulatory activity in the developing distal limbs and pharyngeal arch for a region with accelerated change in humans (HACNS1)155, an increase of activity in the neocortex for another accelerated region (HARE5)156 and a loss of regulatory activity in penile spines of a region deleted in humans (hCONDEL569)72, three anatomical structures that have undergone morphological changes in the human lineage (Fig. 5b). In addition, mouse reporter assays have revealed that a common variant segregating among humans alters the activity of regulatory elements in the knee, which may be tolerated during development, but predisposes to human-specific adult pathology37. New transgenic approaches that enable site-specific integration of enhancers can support a more precise comparison of enhancer alleles by reducing variation associated with random integration156,157. Conceivably, protocols that allow early mouse embryonic development to occur ex utero could enable longitudinal monitoring of regulatory dynamics and support increased throughput of reporter assays in whole organisms158.

Fig. 5. Functional studies of human-specific genetic changes.

a, The molecular effects of human-specific genetic change can be assayed through transgenesis of model organisms. In this way, small segments of human DNA can be introduced into models and the effects can be studied in controlled experiments. For example, human and non-human regulatory regions can be assayed using reporter assays in developing mouse embryos. Human-specific changes can also be stably introduced into mice or non-human primates (NHPs) through genetic engineering approaches. b,c, Examples of genetic changes between great apes that have been linked to human phenotypes through experimental exploration in mice and NHP models. Blue represents regulatory regions (part b), and orange represents protein-coding variants (part c). These and further examples can be found in Table 1.

In addition to reporter assays, recent studies have performed mechanistic analyses of human regulatory variants in mouse models. Sometimes termed ‘humanization’, this process narrowly refers to engineering human variants in a single locus and should not be construed as general humanization of an animal model. Using this approach, human HACNS1 variants were shown to increase Gbx2 expression in distal limbs as predicted by reporter assays, but morphological changes could not be detected using current techniques159. Similarly, introduction of mutations that evolved in the common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees into a regulatory region of the mouse Cbln2 gene increased the expression of Cbln2 in cortical excitatory neurons. This expression change, in turn, increased prefrontal cortex synapse number, mirroring changes that occurred in the human lineage160. In addition, human-specific mutations in a skin enhancer that regulates EN1 were sufficient to increase sweat gland number in mice, reflecting recent thermoregulatory changes in human evolution161. Finally, the independent introduction of two GDF5 enhancer variants into mouse models influenced distinct aspects of joint anatomy through highly specific regulatory changes162. Thus, different time scales of evolutionary changes in gene regulation can be addressed in mouse models. Notably, regulatory variants often only subtly affect morphology, making analyses of phenotypic changes challenging. In addition, some cell types and structures that are common in humans may be rare, absent or divergent in mice, further limiting analyses.

Functional studies of human-specific changes that impact protein function

Human-specific genetic changes can also affect protein function. There are multiple mechanisms for physiological novelty through protein change, including amino acid substitutions163, duplication and divergence, copy number variation or the creation of entirely new genes, such as recently identified essential genes encoding short peptides164 (Fig. 5c). Human-specific gene duplications, in particular, have recently been linked to human traits through overexpression of these genes and detailed reconstruction in animal models. For example, ARHGAP11B emerged from a partial gene duplication dated to 5 million years ago and subsequently acquired splicing changes165. Expression of ARHGAP11B in embryonic mouse, ferret and marmoset brains promotes basal progenitor generation and self-renewal and increases cortical area, in some cases inducing gyrification166–168. Further analyses suggest that the human gene acts in mitochondria to support metabolic changes that are important for normal basal progenitor divisions169. Similarly, human-specific copies of NOTCH2NL genes promote proliferative divisions of neural progenitor cells, acting through the NOTCH pathway170,171, as supported by in utero electroporation in mouse models. Finally, SRGAP2C, a truncated gene that emerged 2.4 million years ago through multiple duplications of SRGAP2A inhibits the ancestral gene, resulting in delayed synaptic maturation and increased connectivity within the cortex172–174.

In contrast to gene duplication and divergence, fewer studies have directly examined the consequences of human-specific amino acid substitutions, despite signatures of adaptive selection175–177. One notable example is reconstitution in mice of two human-specific changes to conserved residues in FOXP2, a protein necessary for normal human speech178. This model provided evidence that the human changes influence exploratory and learning behaviours linked to modifications to medium spiny neurons coordinating cortico-striatal networks163,179. Similarly, recent studies have begun to explore the physiological consequences of modern human-specific mutations in mouse models and cell lines109,180,181. Finally, mouse models have been used to link the human-specific inactivation of the CMAH gene that is necessary for synthesis of N-glycolylneuraminic acid to changes in immune response182 and muscle fatigue183, which have implications for human traits. The study of human-specific changes in animal models can reveal effects within the context of organismal physiology; however, these studies are limited by non-human genetic backgrounds, animal rearing techniques and low throughput of the model systems.

Stem cell models for functional experiments in ape genetic and cellular contexts

Stem cells offer the potential to model great ape development entirely in vitro. At the frontier of this field is the use of stem cells to engineer physiologically relevant systems to study the evolution of human development146,184 (Fig. 6a). The strength of this approach comes from the fact that stem cells can be derived from a large number of human and ape individuals to understand variability within and between species, can be cultured in controlled environments, allow for time course measurements, are amenable to genetic and other manipulations, and are conducive to high-throughput screening (Fig. 6b). These qualities overcome limitations of rodent models, which are evolutionarily distantly related to humans, and ethical debates about experiments in NHPs. In addition, stem cells enable phenotypic comparisons at the cellular and molecular levels at developmental stages and in environmental conditions that are not directly addressable in animal models.

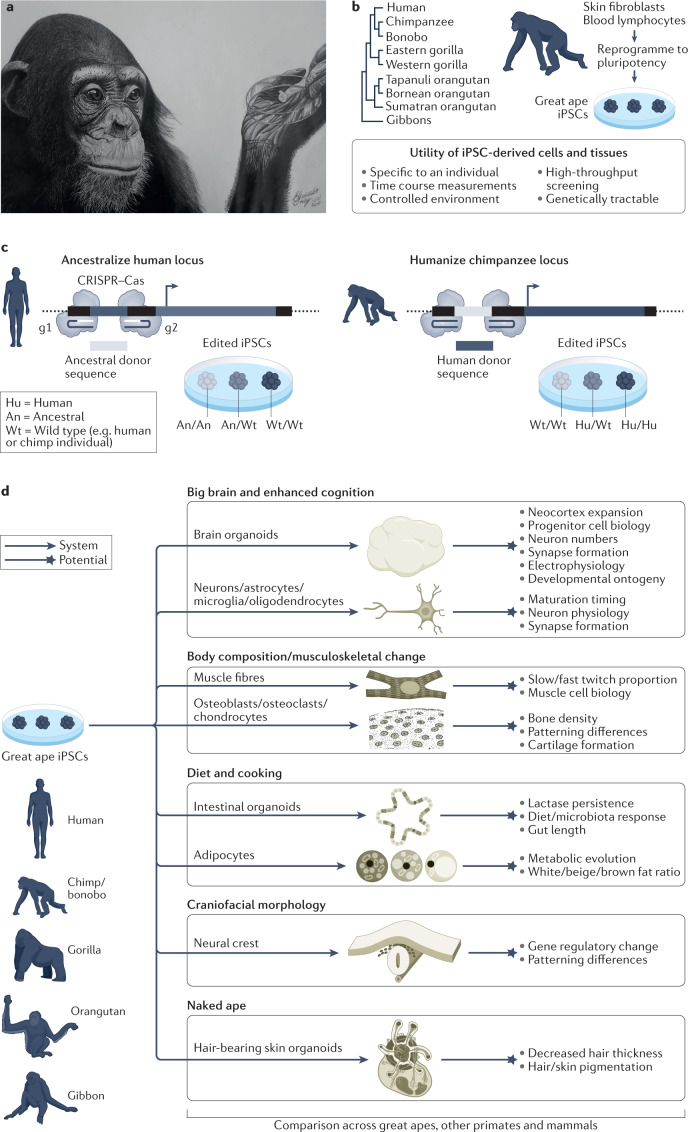

Fig. 6. Great ape organoids to explore the evolution and development of human traits.

a, Pencil drawing that conceptualizes organoids generated from chimpanzee stem cells. b, Induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) can be generated from great apes, which can be used to differentiate diverse cell types or 3D organoid tissues in controlled culture environments that can recapitulate aspects of great ape development and physiology146. c, Functionalized iPSC lines can be used for ancestralization of human or humanization of ape iPSCs at targeted loci. Shown is a schematic strategy using CRISPR–Cas genome editing to target an endogenous locus using pairs of guide RNAs (g1 and g2), whereby the region between the target sites is replaced by an exogenously supplied donor sequence. d, Great ape iPSCs could be used to explore modern human phenotypes. Shown are examples of currently available human in vitro model systems (arrow, system) and the potential for exploring and understanding human-specific traits (star, potential). Such stem cell and organoid systems can be applied across great apes, and other primates and mammals, to explore human molecular, cellular and tissue physiology in controlled environments. Artwork in part a, image courtesy of E. G. Triay. Skin organoid image in part d adapted from ref. 222, Springer Nature Limited.

Great ape stem cell lines could also serve as a repository for a large quantity of naturally occurring ape genetic variation. For example, a survey of 79 ape genomes found more single nucleotide polymorphisms than a comparable survey of 2,504 human genomes from many human populations66,185. At the genome sequence level, increased genetic variation among apes and other NHPs has already been valuable for determining tolerated and pathogenic roles for coding variants of uncertain significance in human genomes186. A similar exploration of the impact of this variation on developmental cell phenotypes could further help to reveal tolerated and pathogenic variation in gene regulation and developmental processes. In addition, ape stem cells can serve as a renewable resource that may contribute to conservation goals, by supporting improved genome assembly and annotation, by enabling analysis of species-specific disease vulnerabilities, including viral tropism187, and by permitting unforeseen future uses as material in frozen zoos188.

Two general categories of stem cell can be used for differentiating human cell types. First, many tissues such as the intestine, liver and muscle harbour resident stem or progenitor cell populations, which can be isolated from the tissue and cultured in vitro under conditions that enable the cells to proliferate while maintaining tissue-specific differentiation capacity189,190. These stem cells (often called adult stem cells) can generate a limited number of cell types present in a given organ and cannot form complex multilineage tissues. For example, adult stem cells from the intestine have been used to generate intestinal epithelial organoids (so-called ‘enteroids’); however, these tissues are composed only of epithelial cell types and lack other important cell features of the intestine191–194. The second strategy is to obtain differentiated cell types (such as skin fibroblasts or blood lymphocytes) from an individual of interest and convert these cells into induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) through cell reprogramming195–198. iPSCs can then be used to differentiate, in principle, into any cell type of the body.

Enormous progress has been made in engineering human cell types and tissues from iPSCs in culture189,199,200. Importantly, iPSCs can recapitulate variation in gene expression and open chromatin attributed to genetic differences201–205, but they also display additional sources of variation related to reprogramming and cell-culture-derived mutations206,207, epigenetic changes208–210, differences in pluripotency state211 and intrinsic patterning biases212, necessitating large sample sizes for comparative studies146. We note that cell culture protocols have predominantly been established and optimized using mouse or human cells, which could affect comparisons between species. Future studies aimed at systematically optimizing protocols among primates could reduce variation within and between species, and also may illuminate peculiarities between species and cell types.

Organoid models to study the evolution of human development (human evo-devo)

Human tissues are composed of many different cell types that signal to each other and coordinate functions over time. Complex self-organizing tissues, called organoids, can be generated in vitro from adult stem cells or iPSCs. Organoids recapitulate some morphological and functional aspects of tissues, and are being used to model human regeneration and development in many tissues, for example, skin, retina, brain, liver, stomach, intestine, kidney and others189,199,213.

Organoids can also be used to study human-specific traits in a human developing tissue context (Fig. 6d). For example, brain organoids can model cortex expansion and other features linked to enhanced cognition145,214–218; muscle fibres and bone differentiation techniques could be used to explore musculoskeletal changes219; small intestine and colon organoids220 and adipose tissue could model metabolic effects of diet and cooking innovations; neural crest can be used to explore craniofacial changes221; and hair-bearing skin organoids222 offer the potential to study changes in hair morphology, eccrine glands and pigmentation.

Studying the evolution of some human traits may require modelling of intercellular interactions not present in organoids patterned to specific germ layers or regions. For example, in the gut, cell types from multiple germ layers are required for normal function, and intestinal organoids combined with neural crest cell co-cultures can now mimic contractile gut movements223. Similarly, combining enteric neuroglial, mesenchymal and epithelial progenitors supported the development of gastric tissue with epithelial glands surrounded by innervated smooth muscle layers224. In the brain, an early study recapitulated interactions between developing hypothalamus and non-neural ectoderm to generate functional pituitary tissue that could influence mouse physiology and behaviour225. Addition of microglia and vascular cells may be important to simulate neuro-immune interactions and promote neuronal maturation226,227. Finally, recent assembly of cortical organoids, with cultured hindbrain or spinal cord and skeletal muscle formed neural circuits capable of eliciting muscle contraction in vitro228,229, providing a model for corticospinal connectivity, a trait that changed recently in human evolution. Even more complex assemblies of organoids may be needed to model hypothesized links between our larger brains5, distinct diet230, shortened gastrointestinal tract21,231 and propensity to store energy in white adipose tissue131.

Organoid systems also have limitations: they often exhibit elevated metabolic stress, limited maturation and higher levels of variation than normal development215,232,233. Still, they are increasingly being applied to biomedical research, translational medicine and evolutionary biology102,184,234. Comparison with reference atlases is crucial to ascertain the fidelity of organoid systems for modelling human and NHP physiology235.

Overview of comparative iPSC studies

The generation of iPSCs from chimpanzees and other great apes provides a tractable experimental system to explore the evolution of human development (‘human evo-devo’)236–239. These and other iPSC lines have been used to study differences at various stages of development in various tissues spanning from pluripotency to directed differentiation of definitive endoderm, cardiomyocytes, neurons, neural crest and brain organoids. This section summarizes some of the key advances and proposes how these complex organoid models and current single-cell approaches could be combined to dissect human developmental specializations (Fig. 7).

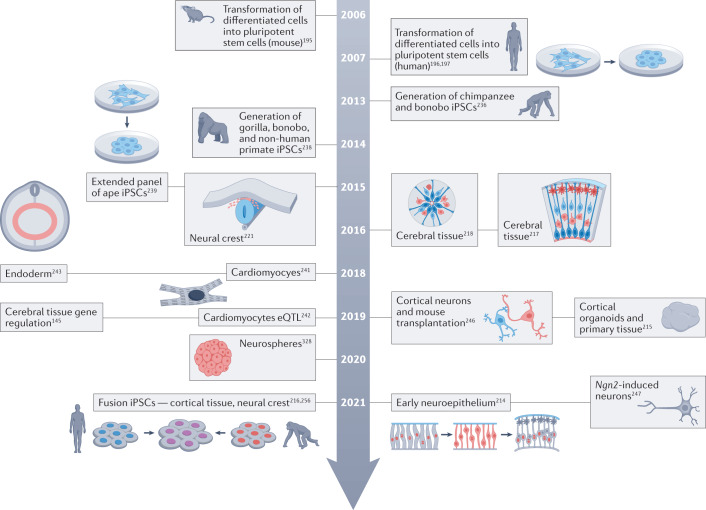

Fig. 7. Milestones in using great ape stem cells to explore uniquely human physiology.

The figure shows a timeline of milestones using stem cells from great apes to explore human-specific development. Additional ref. 328. eQTL, expression quantitative trait loci; iPSC, induced pluripotent stem cell.

Establishing human and ape iPSCs

The innovation of somatic cell reprogramming led to the generation of the first sets of great ape and NHP iPSC resources. A pioneering study that compared human, chimpanzee and bonobo iPSC lines highlighted greater retrotransposon mobility owing to lower expression of A3B and PIWIL2 in the NHP pluripotent stem cell lines236. The generation of a large panel of human and chimpanzee iPSCs by integration-free reprogramming methods further enabled side-by-side comparison of human and chimpanzee iPSC lines, gene expression and DNA methylation profiles across species239. Currently, there are few great ape and other NHP individuals with iPSC lines (Supplementary Table S1), and the genetic complexity of all present-day hominids is not adequately captured in current iPSC repositories. In addition, it is extraordinarily challenging to transport non-human great ape iPSC lines across national borders owing to laws against great ape trafficking240. Therefore, there is a major need for more iPSC lines as well as a strategy to make the lines available internationally. Nonetheless, existing iPSC lines have been used to explore gene expression divergence in various differentiating cell types241–243.

Recapitulation of species differences in gene expression

A major assumption of comparative iPSC studies is that in vitro differentiated cell types will recapitulate evolved species differences in tissue-specific molecular and cellular phenotypes. However, technical variation or non-physiological in vitro conditions could obscure genotype–phenotype linkage. Genetic mapping studies in cell types differentiated from iPSCs from large panels of human individuals support the use of in vitro systems to study genetic control of gene regulation, despite technical sources of variation244,245. However, further validation of interspecies comparative iPSC studies required the establishment of iPSC differentiation protocols with consistent patterning between species and access to comparable primary tissue samples from multiple species.

Optimization of cardiomyocyte differentiation and maturation across iPSC lines from nine human and ten chimpanzee individuals enabled comparison of gene expression divergence within adult organs. Remarkably, iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes recapitulated half of the gene expression changes observed between human and chimpanzee hearts, with a higher specificity for evolved changes in the heart than in other tissues241. Similarly, a study of brain organoids from ten human and eight chimpanzee individuals showed a significant overlap of divergent gene expression from that observed in comparable developing human and macaque cortical cells215, with 85% of these changes specific to iPSC-derived cortical cells compared with fibroblasts or iPSCs. A further study revealed an overlap of divergent neuronal genes detected in organoid models with those observed in adult human and chimpanzee tissue145. Together, these findings support the application of iPSC-derived cell types to descriptive and functional human evo-devo studies.

Comparison of neuronal development and maturation

Neuronal differentiation in 2D adherent culture and 3D brain organoid protocols enables the study of species differences in neural development and maturation. A combination of 2D and 3D cortical cultures and interspecies mixing assays suggested that primate cerebral cortex size is likely to be at least partially regulated cell-autonomously at the level of clonal output from individual cortical progenitor cells218. Combining live imaging and single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) revealed extended prometaphase–metaphase duration in human neural progenitors compared with chimpanzees and the first glimpse of gene expression divergence in progenitors217. scRNA-seq analysis of human and chimpanzee organoids from 18 iPSC lines and primary macaque cortex identified differentially expressed genes in radial glial and neuronal cells, highlighting increased activation of the PI3K–AKT–mTOR signalling pathway in human outer radial glial cells compared with chimpanzees and validating observed differences in primary human and macaque tissue215. A subsequent study further revealed that gene regulatory features that underlie species-specific gene expression are linked to differential chromatin accessibility between human and chimpanzee cell types. This study also exemplifies how intersecting evolutionary signatures such as human-specific alleles, HARs, selective sweep loci and fixed SNCs with cell-type-resolved gene regulatory and expression features provide candidates for follow-up experiments in these controlled systems145. Another comparative study that focused on early time points in brain organoid development suggested changes in the timing of the transition of neuroepithelial cells to radial glia and suggested a role for ZEB2 dynamics in this process214. In addition, human-specific NOTCH2NLA overexpression and deletion in cortical organoids were consistent with mouse studies suggesting that this duplicate gene delays neuronal differentiation, which could contribute to expansion of neural progenitors in humans171.

Stem cell models can further reveal differences in neuronal maturation and function. A comparison between human, chimpanzee and bonobo suggested differences in neuronal migration and delayed maturation of human cortical pyramidal neurons246. In particular, transplantation of a mixture of human and chimpanzee iPSC-derived neural cells directly to the mouse cortex provided a physiologically relevant environment to compare species differences in maturation, revealing that human cells had increased dendritic arborization and spine number relative to chimpanzee cells 8–19 weeks after transplantation. Another study using neurogenin 2 (NGN2) overexpression to rapidly convert iPSCs into a mixture of excitatory neurons aimed to decouple cell-cycle differences from differences in post-mitotic neuronal maturation. This study reported that genes involved in dendrite and synapse development were expressed earlier in chimpanzee and bonobo than in humans, independent of cell cycle differences, and human neurons displayed longer axons in later stages of in vitro differentiation247. These in vitro studies suggested that the mechanisms that underlie heterochronic changes can be studied in human and other great ape neurons in controlled environments.

Comparison of neural crest and mesoderm-derived cells

Neural crest cells contribute to iconic human traits, including modifications of facial morphology and the larynx. Epigenomic studies of cranial neural crest cells derived from human and chimpanzee iPSCs revealed that more than 10% of candidate enhancers exhibited a species bias in predicted activity221. Despite containing few sequence differences on average, these candidate enhancers were enriched for overlap with HARs, with endogenous retrovirus insertions and with disruption to a subset of transcription factor motifs that are active in neural crest cells221. Transient transgenic analysis further revealed developing craniofacial domains in which species-biased enhancers were active, but it remains challenging to demonstrate that individual enhancers influence human-specific craniofacial features. As a complement to iPSC and animal models of individual mutations, studies of the genetic architecture of human facial structure provide an opportunity to explore whether the same genes and enhancers influence variation among humans248. In addition, studies of patient-derived iPSC lines can help inform mechanisms of normal human craniofacial development. As an example, a recent study explored gene regulatory changes and cellular functions in a large panel of iPSC-derived neural crest cells from patients with deletions and duplication of the Williams–Beuren region of chromosome 7 who exhibit distinct facial dysmorphisms249. This study identified the chromatin remodeller BAZ1B as important for neural crest cell migration and induction and found that genes influenced by BAZ1B dosage were enriched for regulatory changes that evolved in recent human evolution249, supporting a hypothesis that neural crest hypofunction may have influenced human craniofacial evolution250.

Human-specific vulnerabilities can also be explored with iPSCs. For example, humans are more likely to suffer from atherosclerosis, which can cause myocardial ischaemia, whereas chimpanzees and other great apes are more likely to experience myocardial fibrosis251–253. By exposing maturing iPSC-derived cardiomyocytes from both species to normal and low oxygen conditions across a time course, the comparative in vitro system enabled measurement of conserved and species-specific responses in gene expression242. Most gene expression responses (~75%) were conserved, but the authors identified human-specific responses, including the induction of RASD1, a gene also upregulated in human myocardial ischaemia, highlighting distinct molecular consequences that may influence human disease vulnerability. In addition, the conserved response genes showed strong overlap with human cardiovascular disease genes. Together, these findings indicate that the dynamic nature of comparative iPSC models may enable future dissection of context-dependent human-specific disease mechanisms.

Fused iPSCs to study cis-regulatory divergence

Comparative studies of gene regulation in iPSC-derived cell types enable determination of gene regulatory changes in previously inaccessible cell types, but determining which of these changes are caused by cis-regulatory mutations, such as alterations of enhancer elements, versus trans-regulatory changes, such as alterations of transcription factor dosage, remains challenging. Fusions of human and chimpanzee iPSCs can help to dissect cis versus trans mechanisms of regulatory divergence by forming allotetraploid cell lines in which genomes from the two species share a common trans environment. By analogy with classic studies of organismal F1 hybrids254, the difference in the expression of transcripts from human and chimpanzee alleles can be linked to cis-regulatory changes and separated from confounders related to developmental timing or technical artefacts.

Recent studies have used allotetraploid cells to identify candidate cis-regulatory changes in iPSCs, neural crest cells and neural lineage cells, revealing candidate cell types, such as astrocytes with an enrichment of cis-regulatory changes, and candidate genes, such as EVC2, that may influence craniofacial development216,255,256. Importantly, isolating trans-regulatory changes will still require consistent patterning and differentiation of human and chimpanzee contributor lines, including human–human and chimpanzee–chimpanzee autotetraploid cells, to fates similar to those of fused autotetraploid cells. This is because off-target patterning and batch differences can confound changes in trans regulation. However, efficient culture and differentiation of these cell lines remains challenging, and comparative analysis of cell behaviour is limited in this model because tetraploid cells exhibit both genotypic and phenotypic differences from diploid cells, including common aneuploidies, increased cell size and altered growth rates. Nonetheless, combined with signatures of genome sequence divergence and adaptation, these cell lines provide a bridge to identify causal sequence changes that influence gene regulation.

Importantly, studies that mix human and animal material require careful communication to establish and maintain public trust in science. Terms such as ‘hybrid’ and ‘parental’ used in classical organismal studies, and in somatic cell hybrid models, risk evoking reproductive relationships that do not exist. These terms can be especially misleading because of the close genetic relationship between humans and chimpanzees, as well as the developmental potential of pluripotent stem cells. The reproductive hybrid nomenclature also does not account for additional possibilities of in vitro culture, such as a fused cell line containing the complete genome of three ape species257. Therefore, a team with expertise in iPSCs, development, genetics, law and bioethics has recently proposed guidelines for a structured scientific nomenclature to describe fused pluripotent cell lines and derivatives based on the contributor species, ploidy, sex chromosome content and cell type, as well as reproductively neutral public-facing terminology257. In this proposal, cell fusions would be described as composite cell lines that can be allotetraploid or autotetraploid and that are derived from contributor cells. This nomenclature can more precisely convey what is undertaken in cell fusion experiments and limit possible public or legal backlash arising from miscommunication, as has happened in the past258.

New genetic approaches

Culture systems that can recapitulate primate development and physiology in vitro have enabled researchers to compare molecular characteristics of development between species. One key challenge is to supplement these descriptive comparisons with functional experiments that can conclusively link particular human-specific genetic changes to the developmental and physiological effects they confer. In addition, unlike modern human and other great ape sequences, which can be studied in their cellular context for an increasing range of cell types, the functional effect of sequences unique to ancestral or extinct populations can only be experimentally investigated by artificially introducing these sequences into cells. New tools for genetic modification are now enabling researchers to study human-specific changes that separate us from archaic humans or the human–chimpanzee ancestor.

CRISPR–Cas systems for exploring human-specific variants

RNA-guided Cas nucleases are powerful tools to interrogate these culture systems and link genotype to phenotype. CRISPR–Cas nucleases come in various natural as well as synthetically engineered types, enabling diverse genome and epigenome modifications259. CRISPR tools currently comprise nucleases, nickases, base editors, activators, repressors, methylators, acetylators and recorders137. These tools can be used to explore loss or gain of function, cis-regulatory effects or CNVs through constitutive or inducible modifications. Many of these effectors have already been introduced into diverse human cell types and organoids. When combined with great ape iPSCs that also express CRISPR–Cas machinery, the resulting lines could be used to explore the function of human, ape and ancestral alleles (Fig. 6c). Techniques such as ‘prime editing’ could further allow single-base manipulations to be more scalable260. In addition, strategies for precise deletions using two guide RNAs (gRNAs) enable targeted deletion of cis-regulatory regions261,262.

CRISPR-based repressors and nucleases have already been used to study human evolutionary changes. For example, a recent study used a catalytically inactive form of Cas9 fused to the KRAB repressive domain (dCas9–KRAB) to establish that human-specific and polymorphic non-coding VNTR expansion regulates the gene ZNF558 in cis in iPSCs, to show that ZNF558 regulates the downstream gene SPATA18 in trans in iPSCs and neural lineage cells, and to suggest a role in mitochondrial homeostasis and developmental timing263. In another example, gene editing with nuclease-active Cas9 was used to explore the impact of a modern-human-specific amino acid substitution in NOVA1 on a haplotype with evidence of recent selection. Human cortical organoids homozygous for the archaic variant exhibited differences in gene expression and splicing, and organoids homozygous for the archaic variant as well as organoids heterozygous for the archaic variant and a null allele exhibited dramatic developmental changes at the level of cell behaviour and organoid structure264. Future experiments can evaluate cellular mechanisms and controversy that surround the details of the methodology265,266.

As a general caution for the field, gene editing can have off-target effects, and establishing clonal lines can cause additional technical variation in cell behaviour between clones265,266. Another caveat for gene editing studies of evolutionary changes is that the ancestral trans environment cannot be precisely modelled in extant cells. However, introduction of a modern human variant in chimpanzee iPSCs that naturally contain the ancestral genotype at the target site could enable reciprocal experiments to ancestralization of human cells. This would be analogous to rescuing mutant phenotypes in disease models to further support that the mutation is causative. Finally, large repositories of human iPSC lines harbour extensive catalogues of Neanderthal, Denisovan and other archaic alleles, and these resources provide diverse genetic backgrounds and additional trans environments for testing the consequence of genetic mutations in engineered cells and tissues102. Thus, genome editing in human and ape stem cell models provides a tractable approach to understanding genetic changes that distinguish humans from present-day apes and from other archaic hominins.

CRISPR–Cas screens with single-cell resolution

Single-cell analysis methods enable bypass of clonal line generation for measuring some phenotypes137. For example, gRNAs can be introduced into Cas-expressing cells mosaically, and transcriptomes or other cellular features can be sequenced per cell along with the expressed gRNA or associated barcode. This experimental design allows for both the control and mutant genotypes to be assessed within the same organoid or cell population. This approach can be scaled by introducing gRNA pools and a Cas protein into cells such that each cell expresses different gRNAs. The transcriptome and gRNAs can be measured per cell such that many targeted changes can be assayed in the same experiment with single-cell resolution, providing a controlled setting to compare across perturbations267–269. CRISPR–Cas screening with single-cell sequencing in iPSC-derived organoids has already been applied to study cell fate decisions in human organoids270 and represents a promising path to explore human-specific cellular genotype–phenotype relationships. Nonetheless, caveats remain, including the heterogeneity of cells in the organoid, the challenge of studying cell-extrinsic phenotypes in a pooled culture, the challenge to match the presence of gRNAs to on- and off-target edits by Cas9 nuclease and the limitations of phenotypes thus far to transcription. Strategies to increase cell sequencing throughput271 or use image-based in situ sequencing to provide spatial context272,273, are promising technologies to study human-specific changes.

Systematic analysis of human-specific genetic changes

Massively parallel reporter assays (MPRAs) and self-transcribing active regulatory region sequencing (STARR-seq) can be used to study the influence of recently evolved genetic variants on cis-regulatory activity. These approaches involve large-scale cloning of candidate cis-acting sequences into gene expression vectors274–276. Most commonly, this approach has been applied to study candidate enhancer elements by cloning PCR-amplified or synthesized sequences adjacent to minimal promoters and using barcodes, including the sequence itself, to measure the influence of sequences, and their genetic variants, on reporter expression. However, similar approaches can also be used to study other levels of cis regulation such as splicing and translation277–279. Recently, studies have compared human and ancestral primate liver enhancers in immortalized hepatocytes280, human-specific substitutions in neural stem cells281, introgressed variants in immune cells282, modern human-specific variants in iPSCs, neural progenitors and bone osteoblasts283, and HARs in human and chimpanzee neural progenitors149. These studies have highlighted candidate human-specific mutations with significant regulatory effects, pathways enriched for cis-regulatory changes and the limited influence of species-specific trans environment on cis-regulatory activity. Importantly, these approaches, whether using episomal plasmids or random integration, do not allow mutations to be studied at their endogenous locus and chromatin context.

Another approach for population-scale experiments is to differentiate pools of iPSCs from many individuals or species together and to disentangle the individual of origin using scRNA-seq methodologies284,285. This approach has recently been applied across human cell lines to study endoderm285 and dopaminergic neuron differentiation286, enabling efficient linkage of genetic variants to gene expression profiles in defined cell types. This pooled approach could be extended to great apes in phylogeny-in-a-dish studies to isolate cell-intrinsic changes in a common environment. Ultimately, these new approaches may enable systematic analysis of the molecular consequences of a substantial portion of human-specific SNCs across diverse cell types1.

Conclusions and future perspectives

Understanding how we became human is a fundamental question that has been approached from a range of scientific and philosophical perspectives. Here, we describe advances in comparative genomics, single-cell atlases, stem cell models and genome modification that now enable researchers to connect human-specific genetic and phenotypic changes.

One theme that emerges in this Review is the importance of understanding the breadth of diversity within, and between, species to uncover the genetic basis of uniquely human traits. The initial sequencing and assembly of the first human reference genomes was a monumental task287,288; however, these efforts produced single instances of what a human genome might look like based on the sequence of genomic segments from a small group of donors. Even with a single reference genome for a small number of species, researchers identified regions of extreme genomic divergence, characterized by many independent mutations between reference genomes. Future studies will be able to identify regions with fewer mutations that are also likely to influence human-specific traits, such as locations where the interspecies divergence is still dramatic relative to limited variation within species. Mutations that define uniquely human traits are also likely to fall outside the variation observed in populations of chimpanzees as well as other great apes, further highlighting how knowledge of ape genomic diversity can prioritize candidate mutations that underlie novel human traits. Diverse modern and ancient genomes will also support temporal ordering of mutations and linkage of genomic events to the fossil record. Ultimately, this large collection of modern and archaic great ape genomes, along with improved statistical methods, will allow us to understand the history of an allele not as present or absent in ancestral populations, but as an allele frequency that is changing over time along branches in the great ape phylogeny.