Abstract

School-wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (SWPBIS) is an inclusive multi-tiered system of behavioral supports that has been widely adopted by K-12 schools in the United States. SWPBIS focuses on creating safe, equitable, and inclusive school environments and has been linked to both positive behavioral and academic outcomes for students and improved perceptions of efficacy and job satisfaction for school personnel. However, there remain concerns about the involvement of students with extensive support needs (ESN) in SWPBIS despite calls to action in 2006 and 2016 for research in this area. Addressing these concerns, we conducted a scoping review to examine the current research literature on SWPBIS and students with ESN. We found that only 10 studies have been conducted since the 2006 call to action. Studies primarily focused on stakeholder perspectives regarding the importance or availability of SWPBIS for students with ESN. Although few studies examined SWPBIS effectiveness, findings from these studies lend support to the effectiveness of Tier 1 SWPBIS for students with ESN. We describe several key implications for supporting the inclusion of students with ESN in SWPBIS and future research initiatives.

Keywords: school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports, SWPBIS, multi-tiered systems of support, extensive support needs, severe disabilities

Under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA 2004), students with disabilities who receive special education services have the right to access general education settings with appropriate supplementary aids and services. Yet, despite research linking inclusive education to positive outcomes for students with disabilities (e.g. improved communication and social skills, greater academic achievement; Agran et al. 2020), the majority of students with extensive support needs (ESN) continue to be educated in separate settings (e.g. self-contained classrooms in public schools, private alternative schools; Wehmeyer et al. 2021). In the United States, students with ESN are the 1–2% of students who typically receive special education services under the categories of autism, intellectual disability, and multiple disabilities who are eligible for alternate assessment (Taub et al. 2017). In separate settings, students with ESN are more likely to be passively engaged and have limited access to high-quality instruction (Kurth et al. 2016; Pennington and Courtade 2015). Likewise, they are less likely to have access to the general education curriculum and same-age peer models of expected behavior (Gee 2020) and more likely to experience punitive discipline practices such as physical restraint and seclusion (Gage et al. 2022). Thus, in separate settings, students with ESN are much less likely to access opportunities to learn and practice behaviors required for success in inclusive, general education settings, thereby increasing the probability of continued exclusion (Hawken and O’Neill 2006).

School-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports

Although research has demonstrated the effectiveness of a variety of behavioral interventions in inclusive, general education settings (e.g. Lory et al. 2020; Walker et al. 2018a; Watkins et al. 2019), challenging behavior continues to be a commonly cited barrier to inclusive education for students with ESN (McCabe et al. 2020; Walker et al. 2018b). School-wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (SWPBIS) is a framework for implementing evidence-based practices that designs and organizes educational environments to support desired behavior and prevent challenging behavior for every student, including students with disabilities (Horner et al. 2017). The three-tiered preventive SWPBIS model is designed to ensure that each student receives the level of behavioral support needed to help ensure their success. A hallmark of Tier 1 support, which all students receive, is the explicit teaching and acknowledgement of school-wide expectations across all school environments. By teaching and providing opportunities to regularly review and practice behavioral expectations, Tier 1 supports increase predictability and consistency across school contexts to prevent and address minor behavioral issues. At advanced tiers of support, students receive additional targeted (Tier 2; 10–15% of students) and intensive individualized (Tier 3; 1–5% of students) behavior supports beyond Tier 1 that match their level of need. SWPBIS teams made up of school personnel meet regularly (e.g. monthly or every two weeks) to assess student outcomes, monitor implementation fidelity, and adjust and adapt school-wide and individual student interventions as needed.

SWPBIS and students with disabilities

SWPBIS grew out of Positive Behavior Support (PBS), an approach focused on improving quality of life and preventing challenging behavior for individuals with disabilities that emerged in the 1980s as an alternative to aversive behavior-change interventions (Carr et al. 2002). Early work in the area of PBS focused on designing inclusive environments to ensure individuals with ESN were viewed as valued members of the community and, as such, treated with respect and dignity (Horner et al. 1990). As a school-wide model of PBS implementation, a primary mission of SWPBIS is to create safe, equitable, and inclusive school cultures to support positive social, behavioral, and academic outcomes for all students, including students with disabilities (www.pbis.org). The framework is currently implemented in over 25,000 schools in the United States alone (www.pbis.org), and over the past 25 years, a large body of research has documented the positive effects of SWPBIS on student outcomes and feelings of safety (Baule and Superior 2020; James et al. 2018), educators’ perceptions of efficacy and job satisfaction (Ross et al. 2012), and overall school climate (Charlton et al. 2021). Yet, despite the inclusive mission of SWPBIS and multiple calls to action highlighting the need to examine the inclusion of students with ESN in SWPBIS (Bambara and Lohrmann 2006; Kurth and Enyart 2016), few studies to date have directly addressed this topic.

The lack of empirical guidance for school personnel focused on how to best support students with ESN within SWPBIS is surprising given the number of potential benefits of this approach for students with disabilities. First, SWPBIS provides a framework within which schools can intentionally build more equitable and inclusive school-wide cultures that support a human rights model of disability. Within a human rights model, disability is understood as a natural part of human diversity (Lawson and Beckett 2021). By meaningfully including students with ESN in all aspects of SWPBIS design and implementation, schools can help foster an inclusive culture in which students with ESN are treated with dignity and respect by all staff and peers. Second, the primary goal of Tier 1 is to create positive, safe, and predictable environments for all students across all school settings. This is accomplished in part by establishing clearly defined expectations, creating predictable school-wide and classroom routines, increasing prompts for positive behavior, and providing more positive feedback than corrective feedback (Simonsen et al. 2020). Thus, Tier 1 offers a systematic way to ensure that all students, regardless of their need for additional support, encounter consistent expectations, frequent reinforcement, and a common language across all school and classroom contexts. For students with ESN, providing consistency across environments can not only prevent challenging behavior but also help foster successful skill generalization across school contexts (Stokes and Baer 1977).

Third, a critical feature of SWPBIS is a focus on providing a school-wide discipline system that includes a continuum of responses to challenging behavior as an alternative to traditional punishment-based and exclusionary consequences. This feature of SWPBIS has particularly important implications for students with ESN. Although students with disabilities make up only about 13% of total school enrollment in the United States, they experience more than half of all suspensions, restraints, and seclusions (Office of Civil Rights 2020). SWPBIS has consistently been shown to reduce schools’ use of punitive and exclusionary discipline practices such as detention, suspension, seclusion, and restraint (Grasley-Boy et al. 2019; Lee and Gage 2020).

Barriers to inclusion in SWPBIS

Although SWPBIS clearly has potential benefits for students with ESN, researchers and scholars have expressed concerns related to the extent to which this student population has access to the full range of SWPBIS supports. In a special issue of Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities (RPSD) released in 2006, contributing authors identified a number of barriers to the inclusion of students with ESN in SWPBIS, with the most significant barrier being the educational placement of students with ESN in separate settings. In addition to the physical separation from inclusive experiences, students in separate settings are often taught almost exclusively by special education teachers, many of whom do not participate in professional development training related to SWPBIS (Carr 2008; Freeman et al. 2006; Walker et al. 2018b). This can result in students with ESN failing to receive appropriate access to less intensive supports provided at Tiers 1 and 2. Further, failing to adapt SWPBIS lessons and visual supports (e.g. posters displaying school-wide expectations) and school-wide acknowledgement systems to ensure cognitive and physical accessibility for students with ESN may result in the insufficient inclusion of these students in SWPBIS (Hawken and O’Neill 2006; Snell 2006).

In 2016, Kurth and Enyart conducted a literature review to identify studies focused on the inclusion of students with ESN within SWPBIS that had been published since the 2006 RPSD special issue call to action. At that time, the authors reported there remained insufficient empirical evidence to determine the extent to which SWPBIS is appropriate for and available and accessible to students with ESN and concluded more data were needed to evaluate whether SWPBIS enhances or engenders inclusive education.

Study purpose

The purpose of the present study was to extend our prior work for the TIES Center (see Conradi et al. 2022) by mapping the state of the research literature related to the involvement of students with ESN in SWPBIS that has been published since the initial 2006 call to action in RPSD. Due to the complex nature of the topic areas of inclusive education for students with ESN and multi-tiered systems of support, we chose to use scoping review methods to develop and answer our research questions. Unlike systematic literature reviews, scoping review procedures are more flexible, allowing for the inclusion and comparison of various types of studies with differing methodologies to more fully capture the breadth of the work related to complex and multifaceted topics (Arksey and O’Malley 2005).

Method

We conducted a scoping review of research focused on SWPBIS and students with ESN following the methodological framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) and advanced recommendations set forth by Levac and colleagues (2010). The six stages of the review were as follows: (1) identify the purpose of the review; (2) identify relevant studies; (3) select studies; (4) chart the data; (5) collate, summarize, and report results; and (6) optional consultation. In this section, we describe in detail each stage of the scoping review process.

Stage 1: Identify the purpose of the review

Prior to engaging in the scoping review process, we determined that our overarching purpose was to examine research addressing the involvement of students with ESN in SWPBIS. To clarify the particular goals of the review, we met as a team to consider our rationale for conducting the review and our intended outcomes (Levac et al. 2010). Based on these discussions, we developed the following three research questions: (a) What themes are present in the current research literature on students with ESN and SWPBIS? (b) What is the breadth and range of the current research literature? and (c) What gaps exist in the research literature that can be addressed in future research? We based all subsequent decisions in Stages 2–6 on these research questions.

Stage 2: Identify relevant studies

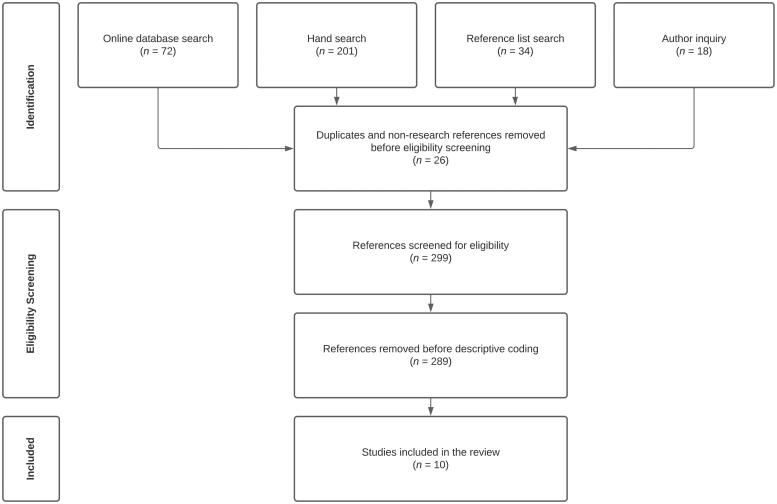

We conducted a comprehensive literature search to identify published and unpublished research that addressed both students with ESN and SWPBIS (see Figure 1). The first three authors who developed the search term lists and carried out the searches had content expertise in both of these areas (Levac et al. 2010). Initially, we searched the following electronic databases: ERIC, PsycINFO, and Proquest Education Database. To identify studies published after the first call to action in the RPSD special issue, we limited the search to studies available in 2006 or after. We searched each online database using two sets of search terms (complete list of terms available upon request) to identify research that aligned to our purpose: (a) students with ESN (e.g. ‘cognitive dis*’, ‘significant dis*’, ‘multiple dis*’) and (b) SWPBIS (e.g. ‘school-wide positive’, ‘positive behavior* support’, ‘multi-tier*’). In total, the electronic database search produced 72 references.

Figure 1.

Study identification and selection processes.

We also conducted hand searches of 11 journals with a history of publishing research on students with ESN and/or SWPBIS (complete list of journals available upon request). This search produced an additional 201 references. Our literature search involved two additional iterative processes that occurred throughout the larger scoping review process. In particular, once we selected studies for inclusion in the review during Stage 3, we reviewed each study’s reference list for additional potentially relevant studies. This process resulted in 34 references for consideration. We also contacted the first authors of these studies to request recommendations for studies that were not identified through our search process or that were currently in press. Gathering this information from outside experts addressed one of our two consultation purposes identified in Stage 6 (Levac et al. 2010). Expert consultation produced an additional 18 references. After removing duplicates and non-research references, we reviewed the remaining 299 references to determine eligibility for inclusion in the review during Stage 3.

Stage 3: Select studies

To select studies eligible for inclusion in the review, two team members (the first and second authors) each independently applied three inclusion criteria to approximately 50% of the references identified in Stage 2. These team members reviewed abstracts and full texts, if necessary, to determine whether studies: (a) addressed SWPBIS, (b) addressed students with ESN, and (c) were relevant to K-12 school settings. The team established these inclusion criteria at the beginning of the selection process and met on a regular basis throughout the process to clarify inclusion criteria definitions and discuss other challenges in selecting studies (Levac et al. 2010). Likewise, the team met to clarify that studies involving (a) individualized behavioral supports that were not delivered within the SWPBIS framework, (b) only students with unrelated disability labels (e.g. specific learning disability), or (c) settings outside of the K-12 schools (e.g. preschool, home, community) were not eligible.

To evaluate inter-rater agreement, three different team members each applied the inclusion criteria to approximately 30% of the references. We used the percent agreement approach to calculate agreement by dividing the number of agreements by the total number of possible agreements and multiplying by 100. Inter-rater agreement was 93%. When there were disagreements on whether the study met the inclusion criteria, the entire team met to discuss the disagreement and reach consensus. As a result of this process, we selected 10 studies for inclusion in the review, all of which were conducted in the United States (see Figure 1).

Stage 4: Chart the data

In this stage, the team collectively developed a data-charting form (available upon request) to extract descriptive data pertinent to the purpose of the review. This was an iterative process in which team members met on a regular basis to identify content categories of interest and refine the data-charting form accordingly (Levac et al. 2010). Initially, we identified several a priori content categories based on the existing SWPBIS literature, including the most recent call to action for research on SWPBIS and students with ESN (Kurth and Enyart 2016), to determine whether the included studies addressed: (a) the appropriateness of SWPBIS for students with ESN, (b) the availability of SWPBIS for students with ESN, (c) inclusive settings and SWPBIS for students with ESN, (d) the effectiveness of SWPBIS for students with ESN, and (e) Tiers 1–3. After this step, we met as a team to discuss whether these content categories adequately captured content presented across studies; this discussion resulted in the decision to retain the first three content categories, combine the last two categories to examine the effectiveness of SWPBIS across Tiers 1–3, and add a new content category related to SWPBIS data collection and assessment.

Next, we identified additional content categories to include in the data-charting form. These content categories served different purposes; some categories offered important contextual information for content analysis purposes, whereas others offered information to answer the research questions. These categories included the study’s purpose and research questions, research design, geographic region, population density (i.e. urban, suburban, rural), school and district demographics, classroom demographics, participant characteristics, results, and implications as identified by the authors. Additional design-specific content categories for intervention studies included independent variable description, role of interventionist, study phases, dependent variable description, and social validity, and for survey studies included survey instrument content.

Each team member used the finalized data-charting form to independently extract descriptive data from two articles (20%) as the primary rater and two additional articles (20%) as the secondary rater. This process involved a combination of in vivo extraction and descriptive summarizing. We met as a team to review the extracted data and reach consensus on the final descriptive information to include. This approach to consensus was advantageous as it permitted in-depth conversations to identify areas of disagreement, which resulted in the entire team carefully reexamining the studies to identify confirming and disconfirming evidence.

Stage 5: Collate, summarize, and report results

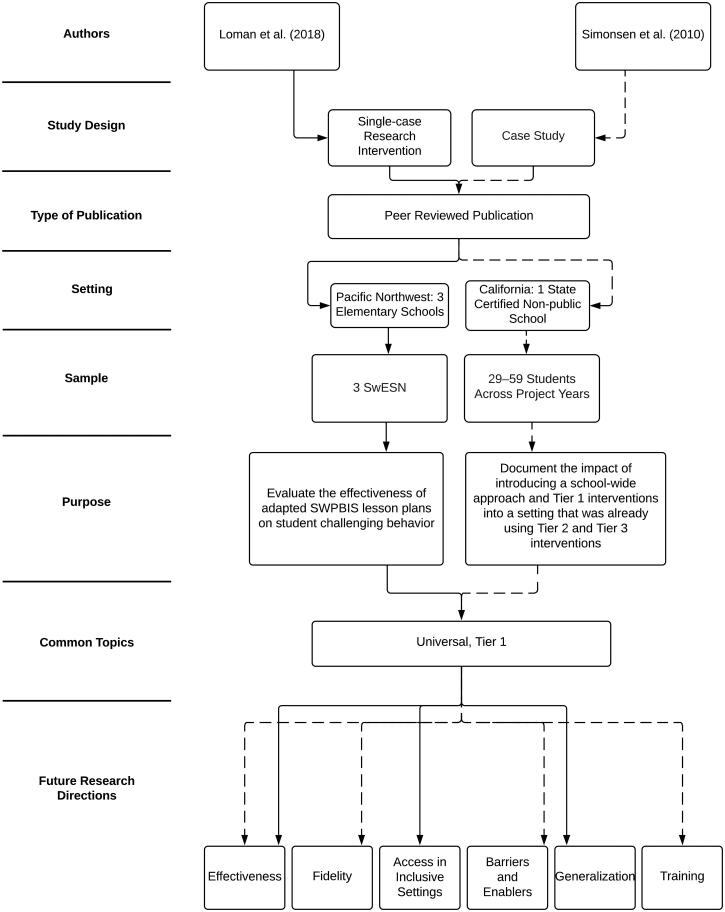

Once we reached consensus on how to most accurately summarize the extracted data, the team reviewed all extracted data to identify patterns across studies to develop a framework for reporting and presenting our results. In this analysis of content, we identified five overarching themes that reflected our original content categories (i.e. appropriateness of SWPBIS, availability of SWPBIS, inclusion and SWPBIS, effectiveness of SWPBIS, SWPBIS data collection and assessment) and developed concept maps for each theme using Lucidchart™ (see Figures 2–6). Through this process, we also identified several subthemes (i.e. common topics) under each overarching theme. Following the concept mapping process described by Harrison et al. (2019), we developed each thematic concept map to include information about the authors, study design, type of publication, setting, sample, purpose, subthemes (i.e. common topics), and future research directions described by authors, which allowed for a clear depiction of the breadth and range of studies focused on SWPBIS and students with ESN. Within each concept map, individual studies were assigned their own unique connecting line with rectangles representing specific content characteristics that were common across or different from other studies within the same theme.

Figure 2.

Appropriateness of SWPBIS concept map.

Note. SwESN = students with extensive support needs.

Figure 3.

Availability of SWPBIS concept map.

Note. SwESN = students with extensive support needs.

Figure 4.

Inclusion and SWPBIS concept map.

Note. SwESN = students with extensive support needs.

Figure 5.

Effectiveness of SWPBIS concept map.

Note. SwESN = students with extensive support needs.

Figure 6.

SWPBIS data collection and assessment concept map.

Note. SwESN = students with extensive support needs.

Stage 6: Optional consultation

In this optional stage, we sought out external consultation that served two purposes. First, as described earlier in Stage 2, we contacted first authors of studies that were included in the review to solicit recommendations for additional research related to the involvement of students with ESN in SWPBIS. Second, we conducted independent interviews with four consultants and communicated via email with a fifth consultant with the specific purpose of sharing a summary of our preliminary findings, including Table 1 and the concept maps (Figures 2–6), and requesting feedback on future research directions (Levac et al. 2010). Consultants were scholars who had published on the topic of this review. During the interviews and through our email communication with the fifth consultant, we asked the following questions: (a) Which of the identified future research directions are high priority? and (b) What recommendations do you have for additional future research that was not already identified? We report their feedback in the Results section.

Table 1.

Study details.

| Themes | Authors | Research purpose | Study design | Sample/setting | Future research directions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appropriateness Availability Assessment |

Kurth and Zagona (2018) | To explore SWPBIS coaches’ perceptions of the involvement of students with ESN in SWPBIS. | Survey | SWPBIS coaches from 559 school districts in the Midwest | Measure the effectiveness of SWPBIS instruction and activities for students with ESN across all SWPBIS tiers. Identify the effects of SWPBIS on social, emotional, academic, and behavioral outcomes for students with ESN. Explore the involvement and accessibility of tiered instruction for students with ESN in SWPBIS across states. |

| Assessment | Kurth et al. (2017) | To explore SWPBIS evaluation tools and their direct and implicit inclusion of students with ESN. | Content analysis | NA | Investigate the involvement of students with ESN across all SWPBIS tiers. Investigate the accessibility of instruction and activities in SWPBIS for students with ESN. Demonstrate how students with ESN are included in the instruction and evaluation across all SWPBIS tiers. Describe the tools used by schools and determine how they include the needs of students with ESN in SWPBIS evaluation. |

| Appropriateness | Landers et al. (2012) | To determine how the needs of students with ESN are addressed in state-level professional development. | Survey | State PBIS coordinators across multiple regions | Future research directions were not clearly described. |

| Appropriateness Inclusion Effectiveness |

Loman et al. (2018) | To evaluate the social validity and effects of an adapted SWPBIS Tier 1 lesson plan on challenging behavior of students with ESN. | Single-case research intervention | Students with ESN in three SWPBIS schools in the Pacific Northwest | Measure the effectiveness of adapted SWPBIS Tier 1 lesson plans when implemented at the same instructional time as peers without disabilities. |

| Availability Inclusion |

Morningstar et al. (2015) | To identify inclusive classroom practices to support the participation and learning of all students, including students with ESN. | Analysis of observation data | Classroom observations in six SWPBIS schools across three states | Compare academic, behavioral, and social outcomes of students across various co-teaching models. |

| Availability Assessment |

Schelling and Harris (2016) | To explore how alternate schools serving students with ESN implement SWPBIS. | Survey | Special education administrators from 26 center-based schools in Michigan | Determine how SWPBIS evaluation tools can be modified to meet the needs of various settings and student populations. Observe school-wide teaching behaviors used to improve student outcomes and measure fidelity of SWPBIS implementation. |

| Appropriateness Availability Assessment |

Shuster et al. (2017) | To examine the involvement of special education teachers in SWPBIS and understand their perceptions about the extent of participation of students with disabilities. | Survey | Special educators from 113 districts in Tennessee | Identify critical components of PBIS training that may effectively change staff and student behavior. |

| Availability Effectiveness |

Simonsen et al. (2010) | To explore the effects of introducing a school-wide approach and a Tier 1 intervention in an alternate school that was already using Tier 2 and Tier 3 interventions. | Case study | One state certified non-public alternate school in northern California | Investigate the effectiveness of implementing SWPBIS in alternative schools. Measure the effects of SWPBIS on students' behavioral and academic outcomes. Conduct a component analysis of SWPBIS training curriculum and identify necessary support structures that may increase positive changes in staff behavior. Identity strategies used to increase the fidelity and implementation of SWPBIS procedures. Explore the SWPBIS supports and practices that are necessary to support students across varying abilities. |

| Appropriateness Availability Assessment |

Walker et al. (2018b) | To explore the perceptions of school personnel on the inclusion of students with ESN in SWPBIS. | Survey | School personnel from 179 SWPBIS schools across multiple regions | Explore effective training procedures for school staff to increase the accessibility of SWPBIS for students with ESN.Determine the extent to which students with ESN are included in SWPBIS across all geographic regions. Evaluate the perspectives of school personnel on the inclusion of students with ESN in SWPBIS. Explore the relation between including students with ESN in general education settings and SWPBIS. |

| Appropriateness | Zagona et al. (2021) | To examine expert perspectives on the extent to which students with ESN should be included in SWPBIS. | Survey | Editorial board members of the Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions | Explore training strategies for school staff to implement SWPBIS for all students, including students with ESN. Investigate effective adaptations that provide access to school-wide expectations for students with ESN. Evaluate if and how students with ESN are being taught school-wide expectations. Identify barriers that influence the implementation of SWPBIS with students with ESN. |

Note. ESN = extensive support needs; SWPBIS = School-wide Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports.

Results

Themes

We identified five themes across the 10 included studies that pertain to students with ESN: (a) appropriateness of SWPBIS (n = 6; see Figure 2), (b) availability of SWPBIS (n = 6; see Figure 3), (c) inclusion and SWPBIS (n = 2; see Figure 4), (d) effectiveness of SWPBIS (n = 2; see Figure 5), and (e) SWPBIS data collection and assessment (n = 5; see Figure 6).

Appropriateness of SWPBIS

Studies addressing the appropriateness of SWPBIS reported stakeholder perceptions of whether and the degree to which SWPBIS is appropriate for students with ESN. For example, Zagona et al. (2021) surveyed PBIS experts about whether students with ESN should participate in SWPBIS. In another example, Walker et al. (2018b) surveyed school personnel from SWPBIS schools to examine the importance of involving students with ESN in various SWPBIS systems, practices, and data collection activities. Two common topics were: (a) the participation of students with ESN in SWPBIS and (b) the importance and benefits of participating in SWPBIS for students with ESN. For example, Shuster et al. (2017) examined the extent of participation among students with ESN in SWPBIS from the perspectives of special education teachers. Landers et al. (2012) explored whether state-level PBIS coordinators perceived that students with ESN could participate in SWPBIS. Additionally, Kurth and Zagona (2018) examined whether SWPBIS coaches (i.e. general education teachers, special education teachers, administrators, related service providers) felt it was possible to include students with ESN across all SWPBIS tiers. In four studies, researchers discussed the importance and benefits of participation in SWPBIS. For example, in their social validity assessment, Loman et al. (2018) asked special education teachers about the benefits of using adapted lesson plans to teach Tier 1 school-wide behavioral expectations to students with ESN.

Availability of SWPBIS

Studies addressing the availability of SWPBIS for students with ESN across tiers focused on whether and how supports at Tiers 1–3 were available and accessible and stakeholder perceptions of such availability. Researchers explored the availability of SWPBIS across various school settings. For example, Simonsen et al. (2010) and Schelling and Harris (2016) examined the availability of SWPBIS in alternative schools for individuals with disabilities. In comparison, Morningstar et al. (2015) observed the availability of SWPBIS in inclusive classrooms for students with and without ESN. Three common topics were: (a) universal Tier 1, (b) advanced tiers (i.e. Tiers 2–3), and (c) barriers and enablers. Researchers from all six studies explored the availability and accessibility of Tier 1 support for students with ESN. For example, Kurth and Zagona (2018) investigated the accessibility of Tier 1 supports and activities (e.g. school-wide expectations and reward systems) for students with ESN from the perspectives of SWPBIS coaches. Walker et al. (2018b) examined whether school-wide expectations were accessible for students with ESN as perceived by school personnel. Researchers from three of the studies examined the availability of advanced tiers for students with ESN. In their survey, Walker et al. (2018b) investigated whether school personnel from SWPBIS schools would consider Tier 2 support for students with ESN. Two of the studies explored barriers and enablers to the involvement of students with ESN in SWPBIS. For example, Shuster et al. (2017) asked special education teachers to identify potential barriers to including students with ESN in SWPBIS and Walker et al. (2018b) asked respondents to identify specific strategies to support the inclusion of students with ESN in SWPBIS.

Inclusion and SWPBIS

Studies that addressed inclusion and SWPBIS for students with ESN examined SWPBIS applied in inclusive settings, SWPBIS outcomes focused on inclusion, and stakeholder perceptions concerning the relationship between inclusion and SWPBIS. Two common topics were: (a) adaptations to SWPBIS lesson plans and (b) supports for learning. Loman et al. (2018) supported special education teachers in adapting Tier 1 SWPBIS lesson plans using Universal Design for Learning (UDL) guidelines to address needs of students with ESN in three inclusive school-wide settings (i.e. cafeteria, hallway, departure). Additionally, Morningstar et al. (2015) conducted observations in six SWPBIS schools to identify effective inclusive practices that supported the participation and learning of all students, including those with ESN.

Effectiveness of SWPBIS

Studies that addressed SWPBIS effectiveness evaluated intervention outcomes for students with ESN across tiers as a result of their participation in SWPBIS. For example, Simonsen et al. (2010) measured the effects of implementing a school-wide approach and Tier 1 intervention in a certified non-public school where Tiers 2–3 were already in place. In another example, Loman et al. (2018) measured the effects of implementing a Tier 1 intervention in three public schools. The common topic across both studies was the effectiveness of universal, Tier 1 support. Simonsen et al. (2010) observed educators posting and explicitly teaching Tier 1 school-wide behavioral expectations to students with and without ESN and measured the effects on student physical aggression and elopement. Similarly, Loman et al. (2018) measured the impact of systematically teaching students with ESN the school-wide expectations using adapted Tier 1 SWPBIS lesson plans on challenging behavior among students with ESN in inclusive school-wide settings.

SWPBIS data collection and assessment

Studies that addressed data collection and assessment investigated students’ inclusion in the collection of behavioral data, screening tools, and/or other behavior assessments. For example, Shuster et al. (2017) asked respondents to rate the involvement of students with disabilities in universal screening tools used to identify behavior interventions and supports. In another example, Schelling and Harris (2016) used an adapted version of the PBIS Self-Assessment Survey (SAS) to determine which components of SWPBIS were implemented with fidelity in schools serving students with ESN. Two common topics were: (a) SWPBIS fidelity assessments and (b) data-based decision making. Researchers from two studies explored SWPBIS fidelity assessments. For example, Kurth et al. (2017) conducted a content analysis of three common SWPBIS evaluation tools to determine their direct and implicit inclusion of students with ESN. Researchers from four of the studies investigated data-based decision-making. For example, Walker et al. (2018b) asked participants questions concerning school-wide data collection practices and whether their schools’ procedures included students with ESN. Kurth and Zagona (2018) asked educators to indicate whether data collection procedures included students with ESN and to what extent they were involved in examining discipline data for students with ESN.

Breadth and range

We identified 10 research studies that varied in design (see Table 1 and Figures 2–6). Researchers most commonly used survey methodology (n = 6). Less common approaches included content analysis (n = 1), single-case intervention (n = 1), case study (n = 1), and analysis of observation data (n = 1). Researchers included a variety of educational stakeholders across studies as follows: special education teachers (n = 849), school-based SWPBIS coaches in various roles (e.g. general education teachers, administrators; n = 305), school personnel from SWPBIS schools (administrators, special education teachers; n = 179), state SWPBIS coaches (n = 51), students in 65 inclusive classrooms including those with ESN, students with a history of aggressive behavior including those with ESN (n = 29–59 across project years), special education administrators (n = 26), editorial board members of the Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions (n = 24), and elementary students with ESN (n = 3). The studies in the review took place across all regions of the United States and all were published in peer-reviewed journals.

Gaps in the research

Researchers from nine of the included studies identified gaps in the research literature related to: (a) effectiveness, (b) extent of involvement and accessibility, (c) access in inclusive settings, (d) perceptions, (e) generalization, (f) training, (g) barriers and enablers, (h) evaluations tools, and (i) fidelity (see Table 1 for details about future research directions across studies). In correspondence with these areas, consultants identified priorities in research as follows: (a) effectiveness, (b) extent of involvement and accessibility, (c) training, (d) evaluations tools, and (e) fidelity. For example, consultants agreed that future research should focus on outcomes for students with ESN by measuring the effectiveness of supports across all SWPBIS tiers. They noted that future research is needed on how to efficiently and effectively adapt tiered supports to meet the needs of students with ESN. Consultants also agreed that future research is needed to examine evaluation tools used by schools to determine how students with ESN are included in SWPBIS evaluation and data systems. Finally, consultants emphasized the importance of identifying effective practices for training school personnel on how to support students with ESN.

Consultants also identified several additional areas for future research. First, they identified a critical need to develop and evaluate the effectiveness of a systematic process in which SWPBIS teams proactively engage to plan supports for meaningful involvement of students with ESN across tiers. They noted that this process should focus on equitable practices and problem solving that relies on data reflecting the experiences of students with ESN. Second, consultants noted the value of exploring the role of educational placement, particularly in terms of whether and how (a) implementation fidelity differs across placements and (b) educational placement mediates the accessibility of SWPBIS and student outcomes. Third, consultants indicated that more research on the perspectives of those who are regularly involved in SWPBIS implementation (e.g. teachers, paraprofessionals) is needed, including an examination of pre-service teacher perspectives concerning their preparedness to fully include students with ESN in SWPBIS. Finally, consultants recommended that student outcomes should be measured relative to their involvement across tiers (e.g. outcomes for students who receive Tiers 1–3 vs. Tier 3 only).

Discussion

The purpose of this scoping review was to map the state of the research literature related to the involvement of students with ESN in SWPBIS. Although over 25,000 schools in the United States have adopted SWPBIS and research evidence suggests positive student and school personnel outcomes (e.g. Baule and Superior 2020; James et al. 2018; Ross et al. 2012), there remain concerns about the inclusion of students with ESN (Kurth and Enyart 2016). It is critically important to understand the breadth, range, and themes of the literature addressing this topic to not only inform future research directions but also provide practitioner and teacher preparation implications. We identified 10 published studies on this topic that were representative of a range of stakeholders (e.g. teachers, students with ESN, SWPBIS coaches) across all geographical regions of the United States. Researchers primarily used survey methodology to gather perceptual data from stakeholders.

We also identified five themes in the research literature. The most commonly addressed themes were appropriateness, availability, and data collection and assessment. Specifically, researchers gathered perceptual data on the availability of Tier 1 and advanced tiers of SWPBIS, the importance and benefits of SWPBIS, barriers and enablers to student involvement in SWPBIS, and how data-based decision making and SWPBIS fidelity assessment reflected students with ESN. This finding is not surprising, as Kurth and Enyart (2016) specifically called for research addressing the appropriateness, availability, and accessibility of SWPBIS for students with ESN. However, it was unexpected that few studies focused on the effectiveness of SWPBIS, particularly in relation to Tier 1, and inclusive educational settings. This particular finding is concerning given that SWPBIS is designed to promote safe, equitable, and inclusive environments for students with and without disabilities (Horner et al. 2017) and, thus, is likely to be effective in supporting the behavioral needs of students with ESN, many of whom experience exclusion from inclusive settings due to challenging behavior (McCabe et al. 2020; Walker et al. 2018b).

We also identified a number of gaps in the research literature that inform future research directions. Researchers reported a wide range of research needs, many of which were consistent with previously identified priorities (e.g. Kurth and Enyart 2016; Snell 2006) and those identified by our consultants. These findings coupled with the small number of studies included in our review suggest there has been a significantly limited response to previous calls to action and a critical need for continued research addressing these gaps, particularly in relation to investigating student outcomes across all tiers of SWPBIS, strategies to ensure accessibility across tiers, and practices for supporting school personnel to improve SWPBIS availability and accessibility for students with ESN.

Limitations

The primary limitation of this review relates to the nature of the scoping review process. Scoping review procedures are particularly advantageous over traditional systematic literature reviews when reviewing complex and multifaceted topics that have not been reviewed comprehensively (Arksey and O’Malley 2005). Because our purpose was to explore and map the scope of research focused on SWPBIS and students with ESN, we did not report detailed characteristics and findings of each study. Once more research has been conducted, for example, to explore effectiveness of SWPBIS across tiers, traditional systematic literature reviews can be conducted that address the shortcomings of a scoping review (e.g. report effectiveness and moderating variables). Despite this limitation, our findings have several important implications.

Implications

Our review suggests that research largely has focused on the availability and appropriateness of SWPBIS for students with ESN. Overall, the extent to which students with ESN participated in SWPBIS varied across studies. This is problematic given that SWPBIS was designed to support all students in all settings (Horner et al. 2017), a notion that was confirmed by experts in one of the included studies (Zagona et al. 2021). As such, it will be important for SWPBIS teams to identify strategies that promote meaningful and equitable involvement in SWPBIS across all educational settings for students with ESN. For example, Walker and Loman (2022) suggested that SWPBIS teams should work closely with teachers of students with ESN to consider adapting existing supports using UDL principles and evidence-based practices for this student population (e.g. Loman et al. 2018) and establishing meaningful data collection procedures that reflect students with ESN. However, as noted earlier, more research is needed to develop a systematic process for adapting supports and examine the effectiveness of supports across tiers.

Studies included in the review indicated that stakeholder perceptions varied, with some holding negative beliefs about the value and importance of SWBIS for students with ESN. This suggests that attitudinal barriers and misconceptions may interfere with student access to SWPBIS (Feueronborn and Tyre 2016; Feuerborn et al. 2018). To address these concerns, it may be important for school personnel responsible for implementation (e.g. general education teachers, special education teachers, paraprofessionals) in a range of settings to collaborate to plan appropriate and effective supports, and likewise, for special education teachers and paraprofessionals of students with ESN to participate in SWPBIS professional development and training (Feuerborn et al. 2018). As noted by researchers and our consultants, school personnel training practices focused on the inclusion of students with ESN are needed to guide SWPBIS teams in these efforts. This also suggests a need for teacher preparation in this area.

Consistent with Ruppar et al.’s (2022) recommendations for teacher education in the area of ESN, preparation programs will need to equip teachers with the knowledge and skills necessary to develop and implement behavioral supports that are inclusive, student centered, dignifying, and evidence-based. Content focused on SWPBIS broadly and strategies for including students with ESN can be embedded in both coursework, ranging from dedicated courses focused on students with ESN to foundational behavior management courses, and field-based experiences. For example, instructors can incorporate content and application activities focused on strategies to adapt existing supports across Tiers 1 and 2 to meet the unique needs of students with ESN, evidence-based practices for students with ESN to teach school-wide expectations and deliver feedback, UDL to plan inclusive and accessible behavioral supports across tiers (see Walker and Loman 2022 for sample UDL planning worksheet), and meaningful SWPBIS data collection practices that reflect students with ESN and lead to effective problem solving.

It also will be important that programs consider field-based placements where pre-service teachers have opportunities to plan and deliver a range of behavioral supports (e.g. preventative supports at Tier 1, individualized behavior intervention plans at Tier 3) for students with ESN under the guidance of a supervising teacher and/or other school personnel who assume roles in SWPBIS implementation (e.g. behavior specialist, school psychologist). Furthermore, field experiences in which pre-service teachers support students with ESN in inclusive school environments may foster a more inclusive and equity-focused teaching philosophy (Kurth et al. 2021). Collectively, course content and field-based experiences related to students with ESN and SWPBIS may influence the extent to which teachers plan and implement an inclusive continuum of behavioral supports offered through SWPBIS that meets the needs of all students within a school.

Conclusion

A primary goal of SWPBIS is to create equitable and inclusive school environments for all students, including those with ESN. However, although SWPBIS has the potential to help schools foster inclusion, the research we reviewed demonstrates that students with ESN are not consistently included in all aspects of SWPBIS. More focused work in this area is needed to provide educators and school leaders with empirically guided practices for more meaningfully including students with ESN within all three tiers of SWPBIS. By building on and extending the existing research on including students with ESN in SWPBIS, we can help schools realize their potential for creating cultures in which all students are included and treated with dignity and respect.

Funding Statement

This document was supported from funds provided by the TIES Center grant supported by the Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) of the U.S Department of Education (#H326Y170004) and the Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports cooperative grant supported by OSEP and the Office of Elementary and Secondary Education (OESE) of the U.S. Department of Education (#H326S180001). The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the positions or policies of the U.S. Department of Education. No official endorsement by the U.S. Department of Education of any product, commodity, or enterprise mentioned in this document is intended or should be inferred.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

References

- * indicates research studies included in the analysis. [Google Scholar]

- Agran, M., Jackson, L., Kurth, J. A., Ryndak, R., Burnette, K., Jameson, M., Zagona, A., Fitzpatrick, H. and Wehmeyer, M.. 2020. Why aren’t students with severe disabilities being placed in general education classrooms: Examining the relations among classroom placement, learner outcomes, and other factors. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 45, 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H. and O’Malley, L.. 2005. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar]

- Bambara, L. M. and Lohrmann, S.. 2006. Introduction to special issue on severe disabilities and school-wide positive behavior support. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 31, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Baule, S. M. and Superior, W. I.. 2020. The impact of PBIS on suspensions by race and ethnicity in urban school districts. AASA Journal of Scholarship and Practice, 16, 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, E. G. 2008. SWPBS: The greatest good for the greatest number, or the needs of the majority trump the needs of the minority? Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 34, 267–269. [Google Scholar]

- Carr, E. G., Dunlap, G., Horner, R. H., Koegel, R. L., Turnbull, A. P., Sailor, W., Anderson, J. L., Albin, R. W., Koegel, L. K. and Fox, L.. 2002. Positive behavior support: Evolution of an applied science. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 4, 4–16. [Google Scholar]

- Charlton, C. T., Moulton, S., Sabey, C. V. and West, R.. 2021. A systematic review of the effects of schoolwide intervention programs on student and teacher perceptions of school climate. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 23, 185–200. [Google Scholar]

- Conradi, L. A., Walker, V. L., McDaid, P., Johnson, H. N. and Strickland-Cohen, M. K. 2022. A literature review of school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports for students with extensive support needs (T IES Center Report 106). T IES Center and the Center on P BIS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuerborn, L. L. and Tyre, A. D.. 2016. How do staff perceive schoolwide positive behavior supports? Implications for teams in planning and implementing schools. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 60, 53–59. [Google Scholar]

- Feuerborn, L. L., Tyre, A. D. and Beaudoin, K.. 2018. Classified staff perceptions of behavior and discipline: Implications for schoolwide positive behavior supports. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 20, 101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R., Eber, L., Anderson, C., Irvin, L., Horner, R., Bounds, M. and Dunlap, G.. 2006. Building inclusive school cultures using school-wide positive behavior support: Designing effective individual support systems for students with significant disabilities. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 31, 4–17. [Google Scholar]

- Gage, N. A., Pico, D. L. and Evanovich, L.. 2022. National trends and school-level predictors of restraint and seclusion for students with disabilities. Exceptionality, 30, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Gee, K. 2020. Why indeed. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 45, 18–22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasley-Boy, N. M., Gage, N. A. and Lombardo, M.. 2019. Effect of SWPBIS on disciplinary exclusions for students with and without disabilities. Exceptional Children, 86, 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison, J. R., Soares, D. A. and Joyce, J.. 2019. Inclusion of students with emotional and behavioural disorders in general education settings: A scoping review of research in the US. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 23, 1209–1231. [Google Scholar]

- Hawken, L. S. and O’Neill, R. E.. 2006. Including students with severe disabilities in all levels of school-wide positive behavior support. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 31, 46–53. [Google Scholar]

- Horner, R. H., Dunlap, G., Koegel, R. L., Carr, E. G., Sailor, W., Anderson, J., Albin, R. W. and O’Neill, R. E. 1990. Toward a technology of “nonaversive” behavioral support. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 15, 125–132. [Google Scholar]

- Horner, R. H., Sugai, G. and Fixsen, D. L.. 2017. Implementing effective educational practices at scales of social importance. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 20, 25–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act, 20 U.S.C. § 1400. 2004.

- James, A. G., Smallwood, L., Noltemeyer, A. and Green, J.. 2018. Assessing school climate within a PBIS framework: Using multi-informant assessment to identify strengths and needs. Educational Studies, 44, 115–118. 10.1080/03055698.2017.1347495 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kurth, A. J., Allcock, H., Walker, V., Olson, A. and Taub, D.. 2021. Faculty perceptions of expertise for inclusive education for students with significant disabilities. Teacher Education and Special Education: The Journal of the Teacher Education Division of the Council for Exceptional Children, 44, 117–133. [Google Scholar]

- Kurth, J. A., Born, K. and Love, H.. 2016. Ecobehavioral characteristics of self-contained high school classrooms for students with severe cognitive disability. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 41, 227–243. [Google Scholar]

- Kurth, J. A. and Enyart, M.. 2016. Schoolwide positive behavior supports and students with significant disabilities: Where are we? Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 41, 216–222. [Google Scholar]

- *Kurth, J. A. and Zagona, A. L.. 2018. Involvement and participation of students with severe disabilities in SWPBIS. The Journal of Special Education, 52, 131–141. [Google Scholar]

- *Kurth, J. A., Zagona, A., Hagiwara, M. and Enyart, M.. 2017. Inclusion of students with significant disabilities in SWPBS evaluation tools. Education and Training in Autism and Developmental Disabilities, 52, 383–392. [Google Scholar]

- *Landers, E., Courtade, G. and Ryndak, D.. 2012. Including students with severe disabilities in school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports: Perceptions of state coordinators. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 37, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, A. and Beckett, A. E.. 2021. The social and human rights models of disability: Towards a complementarity thesis. The International Journal of Human Rights, 25, 348–379. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, A. and Gage, N. A.. 2020. Updating and expanding systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the effects of school-wide positive behavior interventions and supports. Psychology in the Schools, 57, 783–804. [Google Scholar]

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H. and O'Brien, K. K.. 2010. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science : IS, 5, 69–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Loman, S. L., Strickland-Cohen, M. K. and Walker, V. L.. 2018. Promoting the accessibility of SWPBIS for students with severe disabilities. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 20, 113–123. [Google Scholar]

- Lory, C., Mason, R., Davis, J., Wang, D., Kim, S., Gregori, E. and David, M.. 2020. A meta‑analysis of challenging behavior interventions for students with developmental disabilities in inclusive school settings. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 50, 1221–1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe, K. M., Ruppar, A., Kurth, J. A., McQueston, J. A., Johnston, R. and Toews, S. G.. 2020. Cracks in the continuum: A critical analysis of least restrictive environment for students with significant support needs. Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education, 122, 1–209. [Google Scholar]

- *Morningstar, M. E., Shogren, K. A., Lee, H. and Born, K.. 2015. Preliminary lessons about supporting participation and learning in inclusive classrooms. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 40, 192–210. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Civil Rights. 2020. 2017–2018 civil rights data collection: The use of restraint and seclusion on children with disabilities in K-12 schools. U.S. Department of Education, Office of Civil Rights, Washington, D.C. https://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/ocr/docs/restraint-and-seclusion.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Pennington, R. C. and Courtade, G. R.. 2015. An examination of teacher and student behaviors in classrooms for students with moderate and severe intellectual disability. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 59, 40–47. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, S. W., Romer, N. and Horner, R. H.. 2012. Teacher well-being and the implementation of school-wide positive behavior interventions and supports. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 14, 118–128. [Google Scholar]

- *Schelling, A. L. and Harris, M. L.. 2016. School-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports: A snapshot of implementation in schools serving students with significant disabilities. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 18, 241–250. [Google Scholar]

- *Shuster, B.C., Gustafso, J. R., Jenkins, A. B., Lloyd, B. P., Carter, E. W. and Bernstein, C. F.. 2017. Including students with disabilities in positive behavioral interventions and supports: Experiences and perspectives of special educators. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 19, 143–157. [Google Scholar]

- *Simonsen, B., Britton, L. and Young, D.. 2010. School-wide positive behavior support in an alternative school setting: A case study. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 12, 180–191. [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen, B., Freeman, J., Myers, D., Dooley, K., Maddock, E., Kern, L. and Byun, S.. 2020. The effects of targeted professional development on teachers’ use of empirically supported classroom management practices. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 22, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Snell, M. E. 2006. What's the verdict: Are students with severe disabilities included in school-wide positive behavior support? Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 31, 62–65. [Google Scholar]

- Stokes, T. F. and Baer, D. M.. 1977. An implicit technology of generalization. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 10, 349–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taub, D. A., McCord, J. A. and Ryndak, D. L.. 2017. Opportunities to learn for students with extensive support needs: A context of research-supported practices for all in general education classes. The Journal of Special Education, 51, 127–137. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, V. L., Chung, Y. and Bonnet, L.. 2018a. Function-based intervention in inclusive school settings: A meta-analysis. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 20, 203–216. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, V. L. and Loman, S.. 2022. Strategies for including students with extensive support needs in SWPBIS. Inclusive Practices, 1, 23–32. [Google Scholar]

- *Walker, V. L., Loman, S. L., Hara, M., Park, K. L. and Strickland-Cohen, M. K.. 2018b. Examining the inclusion of students with severe disabilities in school-wide positive behavioral interventions and supports. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 43, 223–238. [Google Scholar]

- Watkins, L., Ledbetter-Cho, K., O'Reilly, M., Barnard-Brak, L. and Garcia-Grau, P.. 2019. Interventions for students with autism in inclusive settings: A best-evidence synthesis and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 145, 490–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehmeyer, M., Shogren, K. and Kurth, J.. 2021. The state of inclusion with students with intellectual and developmental disabilities in the United States. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 18, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- *Zagona, A. L., Walker, V. L., Lansey, K. R. and Kurth, J.. 2021. Expert perspectives on the inclusion of students with significant disabilities in schoolwide positive behavioral interventions and supports. Inclusion, 9, 276–289. 10.1352/2326-6988-9.4.276 [DOI] [Google Scholar]