Abstract

Background

Black/African Americans are receiving COVID-19 vaccines at much lower rates than whites. However, research is still evolving that explains why these vaccination rates are lower. The aim of this study was to examine the effects of the pandemic among older Black/African Americans, with an emphasis on trust and vaccine intention prior to vaccine development.

Methods

Data were collected between July and September 2020 from 8 virtual focus groups in Detroit, MI and San Francisco Bay Area, CA with 33 older African Americans and 11 caregivers of older African Americans with cognitive impairment, supplemented by one virtual meeting with the project's Community Advisory Board. Inductive/deductive content analysis was used to identify themes.

Results

Five major themes influenced the intention to be vaccinated: uncertainty, systemic abandonment, decrease in trust, resistance to vaccines, and opportunities for vaccination. The last theme, opportunities for vaccination, emerged as a result of interaction with our CAB while collecting project data after the vaccines were available which provided additional insights about potential opportunities that would promote the uptake of COVID-19 vaccination among older Black/African Americans. The results also include application of the themes to a multi-layer framework for understanding precarity and the development of an Integrated Logic Model for a Public Health Crisis.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that trust and culturally relevant information need to be addressed immediately to accelerate vaccine uptake among older Black/African Americans. New initiatives are needed to foster trust and address systemic abandonment from all institutions. In addition, culturally relevant public health campaigns about vaccine uptake are needed. Thus, systemic issues need immediate attention to reduce health disparities associated with COVID-19.

1. Introduction

The novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2 [COVID-19]) was identified in early 2020 as the cause of a highly contagious, severe acute respiratory syndrome that resulted in a global pandemic. Black/African Americans comprise 13.4% of the US population, yet in the early stages of the pandemic they accounted for more than 24% of the COVID-19-related deaths (Yancy, 2020). Similarly, Black/African American individuals also had lower vaccination rates compared to other racial groups. As of October 2022, although the differences in deaths and cases of COVID-19 between Black/African Americans and Whites are less noticeable, only 46% of Black/African Americans have received their first booster shot as opposed to 60% of Whites (Percent, 2022). COVID-19's impact on communities of color, specifically among Black/African Americans, has amplified the need to immediately identify novel approaches to address these health disparities.

The development of an effective COVID-19 vaccine has been the primary public health strategy to reduce morbidity and mortality in order to end the pandemic. In May 2020, the US federal government accelerated the development of vaccines against COVID-19. After seven months, the Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine received emergency use authorization by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Prior to this emergency use authorization, little was known about COVID-19 vaccine receptivity among African Americans. The term receptivity refers to an individual's openness to receive one of the available COVID-19 vaccines (Lin et al., 2021). Kricorian and Turner's recent study showed that Black respondents, compared to Whites and Hispanics, expressed significantly higher mistrust of the vaccine and less willingness to be vaccinated (Kricorian & Turner, 2021). In a timely systematic review conducted prior to the development of the vaccines, Lin and colleagues (Lin et al., 2021) reviewed 126 surveys in academic and gray literature about COVID-19 vaccine receptivity. The authors found that Black/African Americans reported lower vaccine receptivity than White Americans. According to the authors, the lower receptivity among Black/African Americans was due to low trust in the safety and efficacy of the vaccines, medical mistrust, and issues related to vaccines access (Brandon et al., 2005; Lin et al., 2021). Their review concluded with recommendations for related qualitative studies to facilitate in-depth understandings of COVID-19 vaccine intention.

As expected, COVID-19 vaccine receptivity among Black/African Americans was found to be affected by systemic racism, marginalization, medical mistrust, and neglect from healthcare, pharmaceutical companies, and governmental institutions (Hornsey et al., 2020; Khubchandali et al., 2021; Quinn & Andrasik, 2021). These contexts continue to influence vaccine receptivity towards either completing a primary vaccination series or continued protection with booster vaccinations. Other recently published studies on COVID-19 vaccine receptivity have also provided additional insights into the various reasons for low vaccination uptake among Black/African American adults (Bateman et al., 2022; Bogart et al., 2022; Majee et al., 2022). Some of the predictors of vaccine receptivity identified among Black/African Americans were high levels of mistrust stemming from historical and contemporary experiences of systemic racism against the Black community, structural barriers such as inaccessible vaccination sites, fear of the unknown, and lack of accurate information from trusted community and public health officials. Additional barriers to vaccine receptivity included the belief that the speed at which the vaccines were developed was evidence of intentions to harm the Black/African American community (Dong et al., 2022; Huang, Dove-Medows, & Shealey, 2023).

To gain an in-depth understanding of the concept of vaccine receptivity among older Black/African Americans, we conducted a qualitative study in two cities in the United States. We applied the micro, meso, and macro framework to better understand the influence of individual (micro), institutional (meso), and ideological (macro) factors in the intention to be vaccinated against the COVID-19 virus (Portacolone, 2013). The framework offers the advantage of considering the interplay among multiple lenses, which broadens our purview/perspective. Thus, to assess factors contributing to vaccine intentions among Black/African American older adults, we leveraged qualitative methods to explore two research questions: 1) How did the pandemic shape the concept of trust among older Black/African Americans? and 2) Would older Black/African Americans consider taking any of the three COVID-19 vaccines when they become available? What barriers and facilitators affected the intention to take a COVID-19 vaccine?

2. Methods

2.1. Study design

A qualitative analysis approach was chosen for its ability to evaluate, in depth, the way in which individuals interpret the world through their lived experiences and the meanings they assign to events—in this case, the COVID-19 pandemic. We used qualitative methods, with focus groups as the primary mode of data collection (Krueger & Casey, 2015), to examine the notion of trust before and after the onset of the pandemic as well as attitudes toward vaccine uptake among Black/African American older adults (aged 50 and over) and their caregivers. We included their caregivers because of their unique experiences caring for older adults during the pandemic. To add depth to the analysis, we presented the findings from these focus groups to our Community Advisory Board (CAB) comprised of leaders from the Black/African American community to elicit their perspectives. Participants’ insights were elicited through focus group discussions, which fostered interactions among each other and assisted in capturing their collective narratives and facilitated empowerment (Krueger & Casey, 2015). In addition, focus groups can foster synergies of shared experiences that sometimes defy prevailing norms, adding depth to the analysis insights (Kitzinger, 1994).

2.2. Participants and recruitment

We recruited a subset of participants from a larger qualitative parent study that began in 2019 focused on factors influencing participation in healthcare research among older Black/African Americans and caregivers of Black/African Americans living with dementia (see Table 1 ; Portacolone et al., 2020). In the parent study, inclusion criteria for older adults included being older than 50 years of age and self-reporting as Black/African American. Caregivers were defined as being a family member or friend who had primary responsibility for providing care without financial compensation to at least one Black/African American individual with cognitive impairment during the preceding year. The parent study included 146 individuals (mean age = 65 years; 79% women; 88% high school or more education).

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of focus group participants.

| Characteristics | Total (n = 44) n (percentage) |

|---|---|

| Age (mean, SDa, range) | 67 (SD = 9.89) range = 39-88 |

| Sex, Female | 35 (80%) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 42 (95%) |

| Hispanic/Latino | 0 |

| More than one race | 1 (2%) |

| Not provided/Other | 1 (2%) |

| White | 0 |

| High school education or greater | 38 (86%) |

SD = standard deviation.

Starting in June 2020, we used three strategies to recruit participants for the current sub-study about the pandemic (approved by Blinded Committee on Human Research, number 17–23278). First, we sent emails to participants. Second, we made phone calls to participants who did not have an email address. Third, we asked the community-based organizations involved in our parent study to help us contact potential participants. Participants received a $50 gift card as honorarium to compensate them for their time and effort.

We also involved our existing CAB, which included two men and five women, all Black/African Americans. Of the seven participants, five were from the San Francisco Bay Area and the remaining two individuals were from the Detroit area. CAB members’ professional backgrounds included experiences as administrators of dementia services, county public health officer, publisher, educator, clergy, and leaders of non-profit organizations. CAB members also received an honorarium of $100 per hour for their time and effort.

2.3. Data collection

Eight focus groups were held after the onset of the pandemic but prior to the availability of COVID-19 vaccines becoming available between July and September 2020. Participants were drawn from Detroit, Michigan and the San Francisco Bay Area in California. The focus groups were heterogenous because they included older adults and caregivers. The focus groups were conducted via videoconferencing or telephone conference calls, facilitated by Black/African American female researchers; they were designed to last approximately 90 min and were audio recorded and professionally transcribed. To facilitate inclusion, participants were offered one-on-one Zoom training. A summary of the findings from the first round of focus groups in the parent study were mailed and emailed to subsequent participants two weeks prior to their focus groups. A discussion guide facilitated conversations. First, we presented a summary of what we learned during the first round of focus groups from the parent study. We then asked whether events that had occurred since the last focus group in 2019 had changed in any way participants’ ideas of trust in any way. Next, we asked about attitudes related to whether they would decide to be vaccinated against COVID-19 and the reasons for their answers.

After completion of the preliminary analysis of the focus groups, we hosted a CAB videoconference in March 2021. During the videoconference, the lead author presented the results of the study to seek agreements, disagreements and/or suggestions for expanding the preliminary findings. The CAB videoconference was also designed to last 90 min and was audio recorded and professionally transcribed.

2.4. Data analysis

Audio recordings of the focus groups and the CAB meeting were professionally transcribed verbatim and entered into ATLAS.ti, a qualitative computer software that was used to store and organize the data in order to facilitate the analysis. Transcripts were then analyzed using an inductive/deductive qualitative content analysis (Chreier, 2012). Three independent coders analyzed and coded the transcripts. First, the researchers conducted an inductive content analysis with a sequential coding process. This allowed for codes to emerge from the data (without a priori codes). Initially transcripts were analyzed line by line by the last author to identify specific factors related to the intention of being vaccinated. A new code was generated every time a particular factor related to vaccine intentions was identified. A codebook was created at the onset as codes were being generated. Codes were analyzed and compared with each other for similarities. A senior coder reviewed the last author's codes until interpretative convergence was achieved. To achieve interpretative convergence, the last author and the senior coder reviewed documents coded by one another and resolved any discrepancies in coding until they both coded the documents without discrepancies. The next step in the analysis process was clustering codes together to form categories—and all new categories were presented as themes.

Definitions of codes and related categories were documented by the senior coder in a codebook and then shared with the research team. Next, other independent coders coded the rest of the transcripts; each coded transcript was reviewed by the senior coder to achieve interpretative convergence. Additional codes were added with the approval of both the senior coder and the last author. Saturated themes and related sub-themes were then identified by the last author by making connections among codes, writing memos, and having iterative discussions with the research team. Only after the inductive content analysis was completed, the micro-meso-macro conceptual framework was applied to the themes and sub-themes. In this deductive portion of the analysis, directed content was used to understand how the micro-meso-macro framework applied to the themes to inform the discussion. In particular, the last author engaged in iterative discussions with the research team specifically to look for markers of micro, meso, and/or macro lenses in of each theme. The micro category was used when most quotes of a subtheme referred to subjective sphere, the meso category was used when most quotes pointed to institutional dynamics, and the macro category was used when most quotes pointed to large ideological and systemic processes.

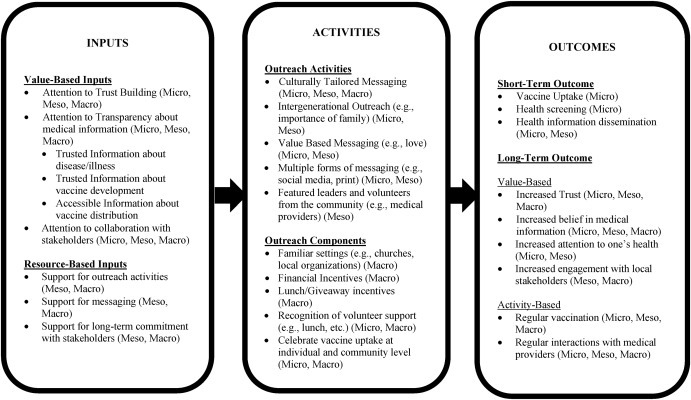

The data presented in this report highlight five central themes that emerged after completing the analysis of the data, as discussed below. After presenting these themes, we have also integrated the themes analytically in two ways. We demonstrate the applicability of these themes to the micro-meso-macro framework. In addition, we propose a logic model (Fig. 1 ) that can be applied to other related or future public health emergencies, regardless of context. Due to the richness of the data, a framework applicable to other health challenges was developed. Specifically, a logic model was developed by integrating the study themes with our theoretical framework, thereby amplifying the innovation of the findings.

Fig. 1.

Integrative logic model for a public health crisis.

3. Results

3.1. Demographic characteristics of focus group participants

Table 1 presents characteristics of the sample. One hundred thirty-five individuals were contacted for participation in this study. Of these, 44 (33%) agreed to participate in one of 8 focus groups (4 per site). The sample included 33 adults aged 50 and over and 11 caregivers. In the focus groups, the overall mean age of participants was 67 mean years (SD = 9.89; range 39–88), and 95% identified as Black or African American; 86% had a high school education or higher.

3.2. Central themes

As previously stated, the data presented in this report highlight five central themes that emerged after we completed the analysis of the data. In the first five sections of the results section, we outlined the five themes and provide narrative exemplar quotes to illustrate our findings. Table 2 provides more details about the themes and their relationship with the micro—meso—macro framework. In the final part of the results section, we provide an illustration of our integrated logic model.

Table 2.

Thematic categories with themes, subthemes, representative quotes, and relevant micro-meso-macro framework construct.

| Theme | Subtheme | Quotes | Micro-meso-macro framework |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty | Unknowns about the virus | I got sick, if I caught the COVID virus, I might even drink, take a drop of Clorox. I don't know what I'm going to do. | Micro |

| Conflicting institutional strategies | “We have so much discord going on from the top.” | Meso | |

| Leadership discounting racism | “He [former President Trump] doesn't feel that racism is a problem … People just wholeheartedly have followed this man and his behaviors.” | Macro | |

| Resorting to agency | “When I first went out, I was panicking. I was scared to death. But now I wear two masks, I wear a shield, I have gloves on, I go to the store and get my groceries.” | Micro | |

| Resorting to Black/African American legacy | “The African American history is rich, …, and listening to others that have done research has really given me a greater sense of pride.” | Micro, macro | |

| Systemic abandonment | Limited support from healthcare providers | “There was no communication [from providers] backwards or forwards … if you are a healthcare organization, you don't have the opportunity to shut down. You should reorganize, re-strategize and continue to do your work. | Meso |

| Limited support from local social services | “I too was impacted this year with COVID. My father passed away at the beginning of [month]. … the response that I got when it came down to resources from our community organizations was very lacking, even with my level of connections. They didn't trust me, it was bad.” | Meso | |

| Limited support from the government | “The government could have sent any among of people in here to help on every aspect, every level, if they wanted to. However, that wasn't done, and people was dying by the second. Not hours, by the second, because it was so many.” | Meso | |

| Feeling last to be served | “Like the gentleman said, we're always … last, we're getting the crumbs.” | Micro | |

| Decrease in trust | Feeling let down | “I do not trust some of the organizations, some of the people that I did trust in the past. … Us as a people, we have been let down.” | Micro |

| Experiencing discrimination | “What I noticed in the metropolitan Detroit area, as it pertains to the Black community, when it comes to a true emergency, true crisis, they were lacking, and that makes me lack trust in you.” | Micro macro | |

| Feeling conspired against | “Some of the women in my group are feeling what people may think of as conspiracy theory, but they're like, ‘are they trying to get rid of us?” | Micro macro | |

| Being open to restoration efforts | “Some of the organizations I have lowered my trust as of now, and hopefully that can be regained in the future.” | Micro macro | |

| Resistance to COVID-19 vaccine | Generalized uncertainties |

Researcher: Would you take the vaccination when it was offered? Participant: “It's too much confusion right now. It's just like you're walking into a kitchen, somebody invites you to dinner, and there is confusion and fighting among the people in the household.” |

Micro Meso Macro |

| Too rapid deployment |

Researcher: If a vaccine was available, would you take the vaccine? Why or why not? Participant: My answer is no, no, no. Only because of how the trials are being, I mean, pushed through too fast.” |

Macro | |

| Legacy of discrimination | “It makes me even more suspicious when they say the first doses of it [vaccine] will be given to the Black and Brown community. Again, using us as the guinea pigs.” | Macro | |

| Decrease in trust towards institutions | “This whole vaccine development, and I mean they've even given it a name, some kind of fast-track name, it has now become a part of the political campaign. It's totally politically motivated.” | Meso | |

| Need for clear and accurate information | “There'd have to be a lot more information.” | Macro meso micro | |

| Opportunities for vaccination | Gaining/regaining trust | “The trust factor came in because people saw Brown people helping [in vaccination sites] … We had a long line of walk ups, and brothers just stopping and coming and getting … the vaccine and taking a chance on it.” | Micro Meso Macro |

| Importance of race-concordant providers | “I will say that it also helped that when I saw some of those presentations [about COVID-19 vaccine] I saw, I saw some people that looked like me speaking to me. And that's very, very important.” | Meso | |

| Empowering and connecting Black/African American communities | “We have like a poster up and we have people take a picture and post it on social media. And we got about 65% of people said they got the vaccination because they knew somebody who did it.” | Micro macro | |

| Support from institutions | “Detroit's Mayor did something really phenomenal. He partnered with the business community that assisted the health department in arranging appointments so you could quickly call, get an appointment, and then they took one of our convention centers downtown, a parking structure, and it's a drive through vaccination.” | Meso | |

| Importance to connecting with families | “Family is absolutely everything. Most of my family … have been vaccinated, and those that aren't plan to do so as soon as its possible to be able to go to our family reunions.” | Micro |

3.3. Uncertainty

A pervasive narrative of uncertainty emerged from participants' narratives. As one participant asked, “what is going to happen?” On a personal level, a few participants were unsure whether they or their loved ones might have contracted the virus. Stepping outside was perceived as being risky because of people taking limited precautions; some participants did not know what to do about supporting family members. For example, one participant was told not to bring her ailing father to the hospital because he might die there. Participants noted a generalized “chaos” in the healthcare system. Within the household, uncertainty manifested in not knowing what to do with regard to solicitations received over the phone and the internet. Uncertainty was also experienced when participants received phone calls from health professionals or when they were asked to go online to do their own research around COVID-19 vaccines. As one participant explained, “they want people to go onto the internet and check this out, and check that out, and compare—things like that. So, if you're not adept at that, you're just lost by the wayside.”

At a broader level, uncertainty stemmed from a limited national strategy. Another respondent noted that “the Bible says without a vision the people perish, and so there's really no real vision anywhere.” Disagreements among institutional representatives were also concerning. For example, a participant explained that “the medical field say one thing, and the political field say another, so we as the constituents don't have any faith in either of them.” Participants' uncertainty was exacerbated by the perceived questionable motivations of national leaders. As one participant concluded “[people] are just not truthful. And you figure at this point it's all about the money, it's all about the fame […]. And so, when the head is wrong, then the body is wrong.” On a related note, a sense of uncertainty tinged with fear stemmed from the presence of doctors and nurses, as well as government officials, following “almost to a fault, like a cult” a president who—according to participants—discounted the impact of racism on pandemic. One participant said, “there's just no truth and no honesty going on nowadays, as far as people and decision-making concerning people's well-being or protection.”

Mixed and conflicting messages from the media further contributed to the uncertainty, as one participant explained: “One day it's one thing, and the next day it's something else.” Another interviewee noted that “things change pretty much every day about what's going on and how to resolve issues […]. People are saying different things. There's no consistency with communication from the media or government.” Finally, uncertainty was exacerbated by distrust in governmental institutions due to historical discrimination and abuse. For example, one participant pondered, “everything starts at the top.” She then asked: “if the top [pointing to former president Trump] is a crook, who can I trust?” Next, she asked, “Is there a crook in some of this confusion that's going on?” To finally warn: “And understand, there's always a Judas in the bunch” pointing to the “corruption” that she observed.

To address this uncertainty, participants resorted to their sense of agency through their own initiatives. One participant explained that “it is about us taking charge, rolling up our sleeves, getting things done.” Other examples of these initiatives included wearing personal protective equipment, becoming more technology savvy, and relying on information coming from reliable sources (e.g., Black American media, Dr. Fauci and the governor of Michigan). Some participants underscored the importance of drawing lessons from “Dr. King” and Black/African American legacy. One said,

Our strength is in our voice. Our strength is in the numbers. Our strength is to take power. I think we've forgotten a few little words that the Constitution is ‘for the people, by the people.’ And I think we can get the change done if we remember that we're not powerless, but powerful.

3.4. Systemic abandonment

Unprompted narratives of abandonment emerged as participants shared recent experiences that were either personal or observed in Black/African American communities. The abandonment was systemic because it stemmed from behaviors of healthcare and government officials who did not properly address the crisis in the Black/African American communities, despite knowing that these communities were particularly affected. One participant noted that “there was too few resources available to not only give us direction, but that they were really there for the African American community.” After acknowledging that people of color are more affected by COVID-19, one participant asked, “where is the follow-through?”

Participants also expressed experiencing abandonment by healthcare providers, local social services, and the government. One participant shared that her primary care physician deterred her from coming to his office because she exhibited COVID-19-like symptoms. She said, “that made me feel as if it was more important for them to protect themselves than to take care of me.” After she called the toll-free number provided by her physician, she was told by the operator to just wait. When asked to describe her reaction to the call, she recalled, “I was upset, I was afraid. Like I'm I going to pass away and nobody's going to do anything to help me?” Another participant who cared for her parents shared her distress because her father, who exhibited COVID-19-like symptoms and had “great insurance.” Not knowing whether he had COVID-19, she first tried to “get directions” from her physicians, but she “could not get through.” Then she drove her father to one healthcare system where he was diagnosed with a flu. One week later, after his condition deteriorated, she drove him to a second healthcare system in the suburbs where she was asked whether she was “from that area.” She added, “then they try to discourage me from even coming to their ER with my father.” Because of her “persistence,” he was admitted, but only offered palliative care, without offering her any other options, and she felt that he died prematurely. While in the process of supporting her father before he died, she also had to care for her mother, who had cognitive impairment and COVID-19-like symptoms. She recalled, “when I reached out to one of the key organizations that normally could provide ample resources and really steer me in the right direction, they were shut down with no communication, no answers to emails, no picking up the phone, nothing, no reroute.”

A generalized sense of being put on the “back burner” emerged, especially among participants who were based in Detroit. Participants’ narratives fed into one another as they explained that Black/African American communities were not served before more affluent White communities. “We got the crumbs of everything,” one participant said. Another said, “we were always last.” Black American communities had to wait longer to get treatments, host testing sites, and receive services as well as “masks and gloves.” One participant asked, “How could you forget us?” Deep sorrow was expressed for Black/African American victims of COVID-19, with another participant suggesting that “all those people that died that could have been saved [ …], if things could have been handled in a different manner.”

3.5. Decrease in trust

When asked whether their ideas of trust changed in any way following the emergence of the pandemic, most participants replied that they felt less trusting. Remarks on overall low trust levels were often heard, such as “my trust level has always been low, pre-pandemic and post-pandemic. As a Black man, even when life is good it can be rough.” This generalized increase in distrust mostly stemmed from the perception that Black American communities were not properly supported during the pandemic. “We have been let down, and it led to distrust.” The management of the pandemic was perceived as a “test” of how responsive institutions, “be it academia, local government, state government, public health [institutions], were towards Black American communities.” Participants detailed the instances that led them to be less trusting. Often their expectations were not met by institutions, as one participant explained: “I have a very different perspective on this [trust] because of the broad, egregious manner in which African American families were denied care by the suburban community health systems.” The above participant whose father died after being denied hospital care linked her decrease in trust to her perception that healthcare providers did not care for him in order to “save their resources.” Relatedly, participants explained that they felt less trusting when they realized that their fears of having contracted COVID-19 were not properly addressed by health care providers. Delays in disseminating culturally appropriate public service announcements, such as Black physicians urging people to wear masks, were also indicated as a reason to be less trusting than before the pandemic. Some participants explained that they felt less trusting of organizations with which they previously felt a sense of belonging, such as local churches and community organizations, because these organizations did not properly protect them during “a true emergency.” Specifically, participants recalled community organizations being unavailable when most needed. One participant also was concerned about the “divided political allegiance” of community organizations, as well “the evangelical or Christian church.”

A few participants questioned the motives behind the overall management of the pandemic. For example, one participant was convinced that “it was just a deliberate thing to not put together a master plan for this country around COVID” because the disease affected mostly “people of color.” Another one explained that “some of the women in my group are feeling what people may think of as conspiracy theory, but they're like, ‘Are they trying to get rid of us?’”

On a positive note, a number of participants shared that they felt an increased level of trust in some healthcare providers, administrators of senior living facilities, public safety institutions, and their faith communities. For example, one participant explained that the pandemic strengthened her relationships with her deputy police chief: “I have his cell phone number, I can text him, I can call him regarding issues, and he's very quick to respond.” Furthermore, the trust that was lost because of the neglect was perceived as something that could be re-earned over time as long as institutional leaders are willing to do the work. For example, one participant mentioned that her trust “can be regained in the future.” Another one explained that “a lot of restoration and work is going to have to be done for me to really help me know that folks know how to cover the African American community and that the commitment is really there.”

3.6. Resistance to COVID-19 vaccine

When asked whether they would consider taking the COVID-19 vaccine once available, most participants intended to decline for reasons mostly related to the previous discussed themes. The three main reasons for the resistance emerged: uncertainty, systemic abandonment, and decrease in trust. The first reason related to uncertainty. “There's so much that we don't know,” said one participant. Specifically, most participants were alarmed that “the [clinical] trials were pushed through so fast,” which raised concerns about safety and unknown potential side effects, especially in the presence of co-morbidities. The ability of the government to decide when a vaccine is safe to be released was questioned, as evidenced in this quote: “The reason for me not taking the vaccination is, number one, that the government [is] rushing through things without getting adequate and sufficient information and data from the scientists.” The lack of coordination between the government and medical associations was concerning. Furthermore, because of the haste of the clinical trials, some participants associated the vaccine with an “experiment” in which people were “guinea pigs.” The few participants who were open to the idea of taking the vaccine preferred to wait “some years” before doing so, even with a new federal administration. As one participant explained, “it has to be seasoned and slightly proven before I will do it.”

Exacerbating the uncertainty was the medical establishment's limited specific knowledge of individual’ health histories. As one participant explained,

No, I'm not going to let anybody put anything inside my body, and I don't know what they're putting inside […]. You don't know my body and I don't know how my system is going to react to what you're going to put in it. No.

On a related note, a generalized resistance toward taking vaccinations and flu shots added to the hesitations. Several accounts about negative personal or learned experiences of people whose health was compromised because of the intake of flu shots and vaccines were often shared. To address these uncertainties, a need for accurate, clear, and transparent information about the vaccine was unanimously voiced. As one participant explained, “I would take the vaccine but not at this time, not until they have well established, evidence-based data and statistics.”

The second reason cited was related to the abandonment of Black American communities. As a result, a few participants preferred to wait a few years because they were concerned that would be treated as “the testing community and we'll just see what happens because we don't care if they die. We'll just make sure it's better for the next group that comes along.” One participant even hypothesized that the vaccine could be used “to get rid of people.” The limited support provided to Black American communities during the pandemic also translated into a hesitancy to consider taking the vaccine or participating in COVID-19 related research. One participant asked, “Why would I trust you with my DNA if I can't trust you to pick up the phone?” With regard to participating in COVID-19 related research, most participants were reluctant to engage in invasive procedures yet open to filling out surveys or providing their opinion. To explain her resistance to participating in invasive COVID-19 research, a participant stated, “my trust system has been depleted.”

The final theme contributing to the resistance to the COVID-19 vaccine is related to the decrease in trust toward institutions, which translated into limited trust in the vaccine development and implementation. One participant believed that trusting God was enough to be protected. Another participant asked, “Do I trust in the makers of these vaccinations? No.” Another participant reflected that “it's easy to have distrust of what's going on, because you don't really know what they are specifically doing to you or putting in you.” Some participants were concerned about the “political motivations” behind the vaccine rollout, as the following quote illustrates: “I would echo the same feelings that the prior three respondents have expressed. This whole vaccine development […] has now become a part of the political campaign.” Others questioned how the vaccine will be released. One asked, “We're back to the mistrust in terms of who are you going to vaccinate? Are you going to vaccinate all? Are you going to vaccinate specific people?”

3.7. Opportunities for vaccination

As previously described in the methods section, we took the above findings to our CAB and engaged them in a conversation around the results. They agreed that the findings portrayed the experience of most Black communities in Detroit and the San Francisco Bay Area prior to the development of vaccines. CAB members centered their discussion on the COVID-19 vaccination efforts 12 months after vaccine development. A key message was that the vaccination rollout was an opportunity to protect the health of Black communities as well as to proactively gain or regain, at least partially, their trust in local and governmental institutions.

“We're off to a good start,” a CAB member from Detroit noted about the efforts of the mayor to ensure that “Detroit [has] the best.” Specifically, she praised the mayor for doing “something really phenomenal: He partnered with the business community that assisted the health department in arranging appointments so you could quickly call, get an appointment, […] drive in, get your vaccine, never get out of your car, and you are gone.” Other CAB members underscored the multiple opportunities to raise the morale among Black American communities in order to increase vaccination uptake such as offering vaccination sites organized by Black organizations in local establishments (e.g., Black churches and local businesses owned or operated by the community). Having vaccination sites managed by people of color was essential because, “when people see folks that look like them, they seem to respond a little better.” On a related note, echoing the climate of the social justice protest in the summer of 2020 due to the murder of George Floyd, an African American man, at the hands of a police officer as well as the current climate around race and policing in America, the presence of police officers at mass vaccination sites was perceived to be a deterrent to accessing a COVID-19 vaccine.

Indeed, the importance of proactively having community members feel “welcomed” emerged. This was accomplished by giving “goodie bags,” “resources that included finances,” and lunch to volunteers. Other strategies for promoting vaccination programs within communities of color included establishing social media campaigns that targeting the community. One CAB member stressed the importance of fostering a sense of celebration when disseminating the news of being vaccinated: “We have like a poster up and we have people take a picture and post it on social media.” He added that “[at the vaccination site] about 65% of people said they got the vaccination because they knew somebody [else] who did it.” CAB members also talked about the importance of using Black women as a source for promoting the COVID-19 vaccine. Black women's leadership can be used to encourage their partners, children, and other member of the community to be vaccinated: “Wives are pulling their husbands [to get vaccinated].” Another strategy to encourage vaccination uptake among younger Black/African Americans involves the use of social media. For example, one CAB member underscored the key role that social media plays in influencing the opinions of Black communities, especially of younger generations. CAB members also pointed out that reasonable skepticism could be addressed by increasing knowledge about vaccines via presentations over traditional and social media as well as asking pointed questions, such as, “Do you know somebody who had COVID-19 after they got vaccinated?” Finally, CAB members acknowledged that a major enabler for increasing vaccination uptake was love for one's family. “Family's everything,” a CAB member declared, and a major benefit of being vaccinated was the ability to be safely reunited with family.

3.8. Synthetic approaches to themes

3.8.1. Application of a multi-level framework of precarity

The findings presented thus far reflected multiple layers as outlined in the micro—meso—macro framework and elucidated in Table 2. At the micro-subjective level of analysis, the findings underscored a profound distress among older African Americans that affected receptivity towards any approved COVID-19 vaccine. At the meso-institutional level of analysis, the findings illuminated the limited institutional supports available to Black Americans shortly after the start of an international public health emergency requiring sheltering-in-place (Webb Hooper et al., 2021). At the macro-ideological level, our findings shed light on specific factors that contributed to the resistance toward being vaccinated against COVID-19, which included a legacy of discrimination and a generalized mistrust.

3.8.2. Integrated logic model for a public health crisis

Another way to integrate the themes of the data is to offer an integrated logic model for a public health crisis (see Fig. 1). In the logic model, we also integrated the multi-level framework of precarity featured above in the components of the model. The model directly stems from the voices of older adults and caregivers who participated in this study. We offer the model as a guide applicable to future health contexts, where successful rollouts of vaccines or other treatment may be necessary. In terms of inputs or antecedents needed for this approach, we conceptualize inputs in terms of value-based inputs and resource-based inputs. Key values resonating from our data include trust-building, transparency of trusted information, and attention to the importance of collaboration. Resources needed include support to conduct activities as well as support for communication campaigns (e.g., messaging). These resources must be harnessed for the long-haul to sustain collaborations. Once the inputs are available, the second column identifies activities that may contribute to better health (e.g., culturally tailored messaging, intergenerational outreach). In addition, this column provides components of outreach that may be useful in planning the activities. The final column of the logic model depicts short-term outcomes at the micro level (e.g., vaccine uptake, health screening). The short-term outcome may offer the opportunity to provide health-related information to the individual (micro) as well as their family networks (meso) if information is transmitted via word-of-mouth or pamphlets. Ultimately, the model also suggests that a change in an individual's, family's or community's values may occur in the areas of greater trust, transparency, and engagement with local stakeholders. We also envision that it may be modified for other health campaigns as well.

4. Discussion

A major contribution of this paper is the illumination of insights about vaccine intentions prior to development of the COVID-19 vaccines. The findings from this study provide in-depth information about the historical and contemporary factors that contributed to the receptivity of the COVID-19 vaccines among older Black/African Americans adults prior to their availability. Our findings revealed five major themes that influenced the intention to be vaccinated: uncertainty, systemic abandonment, decrease in trust, resistance to vaccines, and opportunities for vaccination. Further interaction with our CAB in a period after the vaccines were available provided additional insights about potential opportunities that would promote the uptake of COVID-19 vaccination among older Black/African Americans, thereby adding depth to our findings.

Our findings underscored a profound distress among older Black/African Americans that affected receptivity toward any of the approved COVID-19 vaccines. This distress stemmed from a sense of uncertainty, feelings of being let down and discounted, as well as discrimination during a pandemic characterized by multiple unknowns (e.g., not knowing the pandemic's length, who has the virus, which public health callers were legitimate). The distress experienced by those in our study population was so acute that it occasionally triggered questions about conspiracies against people of color. Our study expands the findings of other studies related to the perceptions of Black/African American communities in the US with HIV (Bogart et al., 2021) that identified conspiracies theories rooted in the lack of trust in public health and government programs (Latkin et al., 2021; Vergara et al., 2021). The mistrust report by the participants in our study was further exacerbated by conflicting strategies from governmental, public health, and medical officials regarding the overrepresentation of African Americans in COVID-19-related cases and deaths. Our findings also suggest that limited institutional support also likely contributed to the resistance towards the vaccines because their development and deployment were regulated by institutions that were thought to be fully be invested in protecting the health of Black/African Americans (Webb Hooper et al., 2021).

In the present study, participants' narrative demonstrated that COVID-19 vaccine resistance was also rooted in both historical and contemporary experiences of systemic racism, marginalization, mistrust in science, neglect from the medical community, poor public health infrastructure, and governmental institutions (Hornsey et al., 2020; Khubchandali et al., 2021; Quinn & Andrasik, 2021). A key factor that drove the resistance was the political leadership at the time, which discounted systemic racism, blamed Black/African Americans for their inability to mitigate the effects of the pandemic despite many of them lacking the flexibility to work from home or shelter in place the same way as their White counterparts, and lack of cohesion among public health institutions (Momplaisir et al., 2021). These findings were consistent with other research related to the blaming of racial and ethnic minorities post disaster (e.g., failure to evacuate New Orleans following Hurricane Katrina) or the discounting of the negative experience that Black/African Americans encounter when accessing healthcare in the US. Black/African American's mistrust of healthcare systems by Black/African Americans is also a reflection of racial bias among medical providers and healthcare systems (Bogart et al., 2021; LaVeist et al., 2000). To resolve these deeply rooted systemic and institutional failures, efforts must also be redirected from placing the burden on Black/African Americans to resolving systemic issues related to medical mistrust and institutional racism (Hornsey et al., 2020). Our findings underscore the power of acknowledging the root cause of mistrust and institutional racism in order to build trust with communities. Building trust among Black/African American communities requires establishing partnerships among healthcare professionals, public health leadership, and the community. Another strategy for building trust is to identify community expectations along with a plan to fulfill those expectations (Quinn & Andrasik, 2021). For example, a strategic emphasis on repairing the harm done by both historical and contemporary experiences of mistrust, racism, and/or systemic abandonment is essential before reengaging and encouraging Black/African Americans to be vaccinated against COVID-19 (Quinn & Andrasik, 2021). Additional strategies for building trust within the Black/African American communities including creating partnerships with trusted stakeholders within the community.

Researchers and public health practitioners seeking to build trust among Black/African Americans have historically partnered with community-based organizations led by members of the community, religious leaders, or the establishment of CABs that consist of community members. Although these types of partnerships have largely been successful in recruiting Black/African Americans in medical research, they do not last long or are not reciprocated (Quinn & Andrasik, 2021). The relationships structures (e.g., community members and researchers) currently in existence are generally short-lived and often last only as long as the funding associated with the research objectives last, which further adds to the sense of systemic abandonment, unequal treatment, and opens the door for conspiracy theories (Quinn & Andrasik, 2021; Webb Hooper et al., 2021). Opportunities for continued partnership with communities include building relationships that go beyond the existence of research funding or participation in clinical research (Warren et al., 2020). Relationship building with communities of color must also be reciprocal and benefit the communities as well as medical and public health institutions. As outlined by Quinn and Andrasik, to build trust within communities, healthcare and public health institutions must build partnerships that are rooted in bidirectional communication, capacity building, and reciprocity (Quinn & Andrasik, 2021). Partnerships rooted in these principles allow for mutual learning, create understanding, and improve the relationship of all partners as they navigate institutions, organizations, and communities as equal collaborators. These types of partnerships also create opportunities for transparency about the process for the development and implementation of the COVID-19 vaccines as well as create additional opportunities for vaccine literacy, which improves Black/African American communities understanding, trust, and faith in the scientific process (Quinn & Andrasik, 2021). These strategies for building trust are also consistent with the World Health Organization's six determinants of trust: competence, objectivity, fairness, consistency, sincerity, and faith that must be translated to public education (Vergara et al., 2021).

Similar to recent studies on COVID-19 vaccine resistance, our study illuminates the relevance of understanding the root factors influencing COVID-19 vaccine uptake among Black/African American communities (Quinn & Andrasik, 2021). Our findings indicate that, in order to increase vaccination uptake among communities of color, public health, medical practitioners, and government must first repair the harm done as a result of historical and contemporary neglect and discrimination. In addition to repairing those harms, public health and government officials must also address the crises of poverty, under employment, housing instability, and other socioeconomic influences on health. To achieve this, it is essential for medical practitioners, public health officials, and the government to consider that resistance does not necessarily mean refusal to taking COVID-19 vaccines (Jones et al., 2021; Quinn & Andrasik, 2021). Instead, public health awareness campaigns that are culturally tailored should include accurate information about the process involved for the development and approval of the various vaccine candidates (see Table 3 ). Furthermore, to alleviate concerns about community members being seen as guinea pigs, public health messaging should also include the demographic characteristics of the various trials as well as exemplify the value of representation through the diversity of the scientific teams.

Table 3.

Identified challenges and recommendations for vaccine uptake across the five themes.

| Theme | Challenges | Exemplar Quotes | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Uncertainty | Mixed and conflicting messages from the media. | “One day it's one thing, and the next day it's something else.” | Provide information from trusted sources and communicate the evolving nature of the science. |

| Rapid change in COVID related information. | “Things change pretty much every day about what's going on and how to resolve issues […]. People are saying different things. | Taking charge by becoming “technology savvy.” | |

| Systemic abandonment | Lack of communication and support from doctors and public health officials. | “When I reached out to one of the key organizations that normally could provide ample resources and really steer me in the right direction, they were shut down with no communication, no answers to emails, no picking-up the phone, nothing, no reroute.” | Keeping the lines of communication open between institutions and communities were identified as key factors to buffer systemic abandonment. |

| Decrease in trust | Distrust mostly stemmed from the perception that Black/African American communities were not properly supported during the pandemic. | “I have a very different perspective on this [trust] because of the broad, egregious manner in which African American families were denied care by the suburban community health systems.” | Restorative work is needed to rebuild trust. However, institutions “must be willing to do the work.” Trust can be regained through dialogue with faith communities, trusted providers, and public safety institutions. |

| Resistance to COVID-19 vaccine | Fear of the unknown. | “There's so much that we don't know.” | Clearly explain the science behind the vaccine development and provide as much information as possible to the community. |

| Speed of vaccine development. | “The reason for me not taking the vaccination is number one, is that the government [is] rushing through things without getting adequate and sufficient information and data from the scientists.” | Provide resources and information that explain the vaccine development process. | |

| Opportunities for vaccination | Not being seen. | “When people see folks that look like them, they seem to respond a little better.” | Having vaccination sites managed by people of color increases visibility and acceptance. |

| Not knowing who has been vaccinated. | “We have like a poster up and we have people take a picture and post it on social media.” | Utilize social and new media (e.g., Instagram and TikTok) to promote vaccine uptake. |

Although the development of the COVID-19 vaccines in late 2020 was a significant step in curbing the spread of COVID-19, the concerns highlighted in this report as well as emerging data in the literature suggest many reasons for vaccine refusal, resistance, and intentions (Dror et al., 2020; Jones et al., 2021; Malik et al., 2020). For some participants in our study, the rapid development of the vaccines led to increased skepticism about the vaccines safety and effectiveness (Coustasse et al., 2020; Malik et al., 2020). Among other study participants, resistance to accepting the vaccines was due in part to disparities in access to the vaccines, dependence on internet-based appointment systems that disadvantage communities with limited access, placement of vaccination sites outside of Black/African American communities making them impossible to reach without adequate transportation, inequitable distribution of the vaccines to local communities, and persistent biases in the healthcare system. These inequalities added to the perception that the U.S. health care system is fundamentally fraught with systemic and institutional racism (Bunch, 2021; Quinn & Andrasik, 2021). In addition, resistance was driven by the lack of representation of Black/African American providers in the dissemination of vital COVID-19 prevention and vaccination messages tailored towards the community (Momplaisir et al., 2021). Drawing on lessons learned from influenza vaccination programs, Quinn and colleagues illustrated that perceived racial fairness in the healthcare system increased trust in influenza vaccines and uptake whereas experiences of discrimination within the system decreased trust, increased risk of side effects, and reduced uptake of the flu vaccine (Quinn & Andrasik, 2021).

A unique contribution of our study is that our participants' offered recommendations (see Table 3) for increasing vaccinations in Black/African American communities. For example, participants suggested that culturally relevant vaccine rollout involving Black healthcare professionals and community members was an opportunity to empower the Black/African American community as well as strengthen and expand community connections. This recommendation is consistent with other studies that identified the successful dissemination of health promotion messages, such as public health awareness campaigns involving social media influencers and celebrities of color (Portacolone et al., 2020). Such collaborations effectively countered negative social media messages with positive messages that mirrored communities' discussions around vaccine uptake (Bateman et al., 2022; Huang, Dove-Medows, & Shealey, 2023). In addition, our findings also underscored the value of resorting to one's own agency while finding inspiration and comfort in the words of Black/African American leaders, such as Martin Luther King, which provides insights into how public health and government officials can leverage Black/African American legacy and history to foster empowerment and rebuild trust (Bunch, 2021; LaVeist et al., 2000). Moreover, our findings indicate that vaccine resistance does not necessarily equates to vaccine refusal. In follow-up conversations with our CAB and other study participants, many of those who had indicated no intentions of receiving the vaccine later received one of the three approved COVID-19 vaccines available in the United States, illustrating opportunities for vaccination. These findings suggest opportunities that can be leveraged and used to increase vaccination uptake among those who are significantly at risk for COVID-19 morbidity and mortality.

5. Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, our participants were predominantly from two urban areas in the US; thus, the experiences of those residents who live in rural or southern parts of the US were unrepresented in the study. Second, the findings in this report are limited to the small sample of individuals who participated in the study. Third, the experiences of older men and others with diverse gender identities were less represented. Fourth, of the 135 potential participants to whom we contacted for participation, only 44 people participated in the study. The two main factors that explained this discrepancy: our efforts to contact people in the midst of a public health crisis and participants’ limited ability to use videoconferencing even though we offered one-on-one training. Finally, our study took place before any of the three vaccines were developed. Therefore, with these limitations, we assert that our interpretations of our findings are limited to this sample of older Black/African American adults.

6. Conclusion

As of October 2022, only 44% of Black/African Americans age 12 and over in the US are fully vaccinated and have received a booster shot (versus 62% of Whites) (Percent, 2022). To increase vaccination uptake among Black/African Americans, further studies are needed that attempts to understand the deeply rooted experiences of historical and contemporary experiences that fuel mistrust of institutions and COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy. In addition, making these institutions more trustworthy will require researchers to listen to community voices, as well as make concerted efforts to repair historical and contemporary trauma brought by maltreatment and racism within healthcare and public health institutions. To adequately address vaccine resistance, raise vaccine confidence, and create opportunities for vaccination in Black/African American communities, healthcare and public health institutions must employ culturally-tailored health communication strategies (with trusted elders, social media influencers, and Black doctors and researchers) that speak directly to the needs of the community. (Chou & Budenz, 2020),33 One significant aspect of communication must include an acknowledgment of historical and contemporary traumas as well as systemic racism as the root cause of medical mistrust with a focus towards equity. Public health and healthcare organizations should respectfully engage with Black/African American communities, becoming more client-centered, including understanding of and acknowledgment that hesitancy and barriers to vaccine uptake must be viewed through the eyes of members of the Black/African American community (Quinn & Andrasik, 2021).

Ethical statement

We presented an accurate account of the work performed as well as an objective discussion of its significance. Underlying data was represented accurately in the paper. Our paper contain sufficient detail and references to permit others to replicate the work. We acknowledge that fraudulent or knowingly inaccurate statements constitute unethical behaviour and are unacceptable.

We are available to provide the research data supporting our paper for editorial review and/or to comply with the open data requirements of the journal. We are prepared to provide public access to such data, if practicable, and should be prepared to retain such data for a reasonable number of years after publication.

We ensured that we have written entirely original works, and if we have used the work and/or words of others, that this has been appropriately cited or quoted.

Proper acknowledgment of the work of others was given.

We did publish manuscripts describing essentially the same research in more than one journal of primary publication.

Authorship was limited to those who have made a significant contribution to the conception, design, execution, or interpretation of the reported study. All those who have made substantial contributions are listed as co-authors.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Orlando O. Harris: Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Tam E. Perry: Conceptualization, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Julene K. Johnson: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Peter Lichtenberg: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Tangy Washington: Validation, Writing – review & editing. Bonita Kitt: Validation, Writing – review & editing. Michael Shaw: Validation, Writing – review & editing. Sahru Keiser: Investigation, Data curation, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. Thi Tran: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Writing – review & editing. Leah Vest: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Marsha Maloof: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Elena Portacolone: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We are deeply grateful to the participants of the focus groups. We also acknowledge funding from the Alzheimer's Association (2018-AARG-589788 PI Portacolone). We would also like to acknowledge funding support from the National Institute of Mental Health (1 K23 MH130250-01 PI Harris).

References

- Bateman L.B., Hall A.G., Anderson W.A., et al. Exploring COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among stakeholders in african American and latinx communities in the Deep south through the lens of the health belief model. American Journal of Health Promotion. 2022;36:288–295. doi: 10.1177/08901171211045038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart L.M., Dong L., Gandhi P., et al. COVID-19 vaccine intentions and mistrust in a national sample of Black Americans. Journal of the National Medical Association. 2022;113:599–611. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2021.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogart L.M., Ojikutu B.O., Tyagi K., et al. COVID-19-Related medical mistrust, health impacts, and potential vaccine hesitancy among Black Americans living with HIV. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 2021;86:200–207. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000002570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandon D.T., Issac L.A., LaVeist T.A. The legacy of tuskegee and trust in medical care: Is tuskegee responsible for race differences in mistrust of medical care? Journal of the National Medical Association. 2005;97:951–956. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunch L. A tale of two crises: Addressing covid-19 vaccine hesitancy as promoting racial justice. HEC Forum. 2021;33(1–2):143–154. doi: 10.1007/s10730-021-09440-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou W.S., Budenz A. Considering emotion in COVID-19 vaccine communication: Addressing vaccine hesitancy and fostering vaccine confidence. Health Communication. 2020;35(14):1718–1722. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2020.1838096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chreier M. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2012. Qualitative content analysis in practice. [Google Scholar]

- Coustasse A., Kimble G., Maxik K. COVID-19 and vaccine hesitancy A challange the United States must overcome. The Journal of Ambulatory Care Management. 2020;44:71–75. doi: 10.1097/JAC.0000000000000360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong L., Bogart L.M., Gandhi P., et al. A qualitative study of COVID-19 vaccine intentions and mistrust in Black Americans: Recommendations for vaccine dissemination and uptake. PLoS One. 2022;17 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0268020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dror A.A., Elsenbach N., Talber S., et al. Vaccine hesitancy: The next challange in the fight againts COVID-19. European Journal of Epidemiology. 2020;35:775–779. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00671-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornsey M.J., Lobera J., Diaz-Catalan C. Vaccine hesitancy is strongly associated with distrust of conventional medicine, and only weakly associated with trust in alternative medicine. Social Science & Medicine. 2020:255. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W., Dove-Medows E., Shealey J., et al. COVID-19 vaccine attitudes among a majority Black sample in the southern US: Public health implications from a qualitative study. BMC Public Health, 23 (88), 2023 doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-14905-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones D.L., Salazar A.S., Rodriguez V.J., et al. Open Forum Infect Dis; 2021. SARS-CoV-2: Vaccine hesitancy among underrepresented racial and ethnic groups with HIV in Miami, Florida. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khubchandali J., Sharma S., Price J., Wiblishauser M.J., Sharma M., Webb F.J. COVID-19 vaccination hesitancy in the United States. A Rapid National Assessment. 2021:270–277. doi: 10.1007/s10900-020-00958-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitzinger J. The methodology of focus groups—the importance of interaction between research participants. Sociology of Health & Illness. 1994;16:103–121. [Google Scholar]

- Kricorian K., Turner K. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and beliefs among Black and hispanic Americans. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0256122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger R.A., Casey M.A. Sage; Singapore: 2015. Focus groups: A practical guide for applied research. [Google Scholar]

- Latkin C.A., Dayton L., Yi G., Konstantopoulos A., Boodram B. Trust in a COVID-19 vaccine in the U.S.: A social-ecological perspective. Social Science & Medicine. 2021:270. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaVeist T.A., Nickerson K.J., Bowei J.V. Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust, and satisfaction with care among african Americans and white cardiac patients. Medical Care Research and Review. 2000;57:146–161. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin C., Tu P., Beitsch L.M. Confidence and receptivity for COVID-19 vaccines: A rapid systematic review. Vaccines. 2021;9(1) doi: 10.3390/vaccines9010016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majee W., Anakwe A., Onyeaka K., Harvey I.S. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities; 2022. The past is so present: Understanding COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among african American adults using qualitative data. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik A.A., McFadden S.M., Elharake J., Omer S.B. Determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the US. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;26 doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momplaisir F., Haynes N., Nkwihoreze H., Nelson M., Weber R.M., Jemmott J. Understanding drivers of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among blacks. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2021;73(10):1784–1789. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciab102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Percent C.D.C. Of people receiving COVID-19 vaccine by race/ethnicity. 2022. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#vaccination-demographics-trends at.

- Portacolone E. The notion of precariousness among older adults living alone in the United States. Journal of Aging Studies. 2013:166–174. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2013.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portacolone E., Palmer N.R., Lichtenberg P., et al. Earning the trust of African American communities to increase representation in dementia research. Ethnicity & Disease. 2020;30:719–734. doi: 10.18865/ed.30.S2.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn S.C., Andrasik M.P. Addressing vaccine hesitancy in BIPOC communities— toward trustworthiness, partnership, and reciprocity. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021;385(2):97–100. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2103104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergara J.D., Sarmiento P.J.D., Lagman J.D.N. Building public trust: A response to COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy predicament. Journal of Public Health. 2021;43:e291–e292. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren R.C., Forrow L., Hodge D.A., Min D., Troug R.D. Trustworthiness before trust— covid-19 vaccine trials and the Black community. New England Journal of Medicine. 2020:383. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2030033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webb Hooper M., Napoles A.M., Perez-Stable E.J. No population left behind: Vaccine hesitancy and equitable diffusion of effective COVID-19 vaccines. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2021;36:2130–2133. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06698-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancy C.W. COVID-19 and african Americans. JAMA. 2020:323. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.6548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]