Abstract

Objectives:

Utilizing Iridescent Life Course, we examine life events among three generations of lesbian and gay adults: Invisible (born 1920–1934), Silenced (born 1935–1949), and Pride (born 1950–1964) Generations.

Methods:

We utilized a subsample (n = 2079) from the 2014 wave of Aging with Pride: National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study (NHAS). Demographic characteristics, life events, and gender and generational interactions were compared.

Results:

Compared to other generations, the Invisible Generation disclosed their identity at older ages, were more likely to be retired, served in the military, and survived a partner’s death. Compared to the other generations, the Pride Generation was more likely to have disclosed their identities earlier and experienced higher levels of victimization/discrimination.

Discussion:

This paper is the first to examine the lived experiences of the oldest lesbians and gay men and compare them to other generations. The findings illustrate the heteronormative nature of most life course research.

Keywords: sexual minorities, life course, sexuality, diversity, LGBT

Introduction

Within four decades, there will be more than five million sexual and gender minority adults aged 50 and older in the United States (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Kim, 2017). Shifts in the historical, political, and social environment have had a unique impact on the generational experiences and development of today’s lesbian and gay older adults; see also our similar work on generational and social forces with bisexual women and men and gender diverse older adults (Fredriksen Goldsen et al., 2022) and transgender older adults (Fredriksen Goldsen et al., in press). Given the complex social, cultural, and political influences for each generation, lesbians and gay men likely experienced historical and generational events differently than heterosexuals. For example, their intimate sexual behaviors and identities were, by definition, at times considered criminally perverse and mentally ill. Until 1973, the American Psychiatric Association considered “homosexuality” to be a sociopathic personality disturbance (Silverstein, 2009); it was not until 2015 that same-sex relationships were granted full legal recognition (Obergefell v Hodges, 2015) and not until 2020 that federal employment protections were established. Still today federal protections in housing, public accommodations, education, federally funded programs, credit, and jury service do not exist.

While the life courses of sexual and gender minorities may differ in profound ways from heterosexuals, a critical analysis of generational experiences is often hampered by the ways generations have been historically constructed. Generations have been typically cast within a heteronormative framework, characterized as objective, age-based, temporal cycles that similarly aged individuals move through, from dependent status in their families of origin to an independent “procreative” status of forming their own families (Rogler, 2002). From this perspective, a generation is conceived as individuals born during the same time period, sharing common yet unique life events, and a similar pattern of experiences from childhood to adult life (Rogler, 2002). Based on human reproductive cycles, these generational constructions tend to assume heteronormative homogeneity between and within generations.

In contrast to traditional, historically constructed generational patterns, historical generations theory postulates that cataclysmic historical events are the catalysts for new generations, and when historical events reach deeply into society’s institutions they have profound effects, especially on younger people (Rogler, 2002). When critical historical events are experienced as a “sense of rupture with the past” (Wohl, 1979, p. 279), robust generational identities are constituted and communicated via symbolic representations—cultural emblems—signs and symbols that convey meanings and messages between members of identity generations (Rogler, 2002). Examples of critical historical events include World War II, the AIDS pandemic, and most recently COVID-19. While every American who lived during these eras experienced these “cataclysmic events,” the social positionalities of each played a crucial role in how individuals experienced them. For example, gay men in the 1980s had a very different experience of the AIDS pandemic than heterosexual men or women.

The Health Equity Promotion Model is the first framework to incorporate a life-course development perspective to understand the risk and protective factors associated with health and well-being among sexual and gender minorities (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2014). This developmental perspective, the Iridescent Life Course (Fredriksen Goldsen et al., 2019) illuminates the intersections between identity and context that produces distinct experiences in the lives of marginalized people (Fredriksen Goldsen et al., 2019) as well as the generational differences among lesbian and gay older adults in the U.S. Central to this theory is the very meaning of the word iridescence, from the Latin word iris, meaning rainbow, which describes the blurring of colors as seen from different angles and perspectives. Nesting life events within historical times and intersectional identities is critical to understanding context as a variable in the differing experiences of unique generations of adults. “Such an approach incorporates both queering and trans-forming the life course, capturing intersectionality, fluidity over time, and the psychological, behavioral, and biological as well as social dimensions of LGBTQ aging” (Fredriksen Goldsen et al., 2019, p. 254). Intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1989) speaks to the idea that we all have multiple social identities (e.g., race/ethnicity, gender, class, and sexual orientation) that intersect in terms of relative privilege and oppression. Intersecting social identities are time and context dependent, and thus interact differentially. For example, in both Europe and the United States, from the late 19th and through most of the 20th centuries, men’s same-sex desires and relationships were vilified to a much greater extent than women’s. Such an approach centers the heterogeneity of the lived experiences of sexual and gender minority older adults who have historically been portrayed as homogenous groups.

Using the Iridescent Life Course as our map, we emphasize the intersections of non-heteronormative sexual identities, gender, and age within a historical context, informing our understanding of the life course across generations. The Iridescent Life Course framework goes beyond traditional static generational models to call attention to how generations reflect aging lives and interact with individual, interpersonal, institutional, and structural opportunities and barriers.

Invisible, Silenced, and Pride Generations: Historical and Cultural Contexts

When the intersectionality of sexualities, gender, and age is taken into consideration with historical contexts, older sexual and gender minority adults can be seen as members of several historical generations, including the Invisible, Silenced, and Pride Generations. The Invisible Generation (birth years circa 1920–1934) was born during a critical historical event—a rupture—as the United States transitioned from the Progressive Era following World War I. The impacts of the Great Depression (1929–1939) extended into the Invisible Generation’s coming of age years (early 1930s through early 1940s). The Invisible Generation came of age during a time when their sexual and gender identities were “invisible,” recognized neither socially nor politically in America. While gays and lesbians organizing in the U.S. was rare at the time, social gatherings did begin to emerge (Canaday, 2009). Seen through the lens of the Iridescent Life Course, the nascent emergence of lesbian and gay organizing reflects the resistance and negotiations of agency within these historical events and conditions.

The Invisible Generation not only experienced the Great Depression, but many fought in World War II. From 1942 to 1945, over 16 million Americans served in the war, including 350,000 women. This inclusion of women, initially driven by need, laid a new foundation for social fluidity. Women had a new space in which to resist confinements of existing gender norms and negotiate their agency and independence. Also, during this period, homosexuality as an “inclination” (e.g., identity) began to be differentiated from “behavior” by medical and legal institutions, separating the “worthy” (e.g., a youthful, drunken indiscretion) from the “unworthy”—those who were deemed inherently homosexual (Canaday, 2009). For example, those discharged from the armed services as a “confirmed” homosexual would be given a “blue discharge,” so called for the blue paper it was printed on. The document became a symbolic cultural emblem, conveying the consequences of disobeying the moral norms of the nation-state. During the post-war years, potential employers routinely requested military discharge papers and those with a blue discharge were also denied GI benefits.

The Silenced Generation (birth years circa 1935–1949) experienced the rupture of full-on public discourse regarding homosexuality during their coming of age years (late 1940s through late 1950s). The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw critical historical events through the emergence of the medical exploration of “sexual inversion” (i.e., homosexuality) in scientific circles, which helped to shape the psychosocial development of lesbian and gay adults born in the early to mid-20th century.

Kinsey et al. (1948) publication of the Sexual Behavior in the Human Male challenged conventional beliefs about sexuality while discussing previously taboo subjects. Among Kinsey and colleagues’ major findings was that about 10% of men could be classified as homosexual. Five years later, Kinsey and colleagues published Sexual Behavior in the Human Female (1953), which dissected the sex lives of American women, and provoked even more interest and outrage from the general public. This work purported that between 2% and 6% of women could be characterized as homosexual. Published in an era of suspicion and anti-communist hysteria, Kinsey’s reports were used in congressional investigations, accusing the authors of helping to weaken American morality, thereby aiding the cause of communism (Adkins, 2016).

During this time, which included the McCarthy Era, some lawmakers were convinced there were communist spies everywhere and identified “sexual perverts” as vulnerable to blackmail. McCarthy spearheaded a national witch-hunt known as the “Lavender Scare,” targeting lesbians and gay men. In 1953, President Eisenhower signed an executive order listing “sexual perversion” as a category that barred individuals from federal employment (Johnson, 2004). During the same period, in 1952, the American Psychiatric Association formally designated homosexuality as a “sociopathic personality disorder” (Silverstein, 2009). Lesbians and gay men could be arrested and involuntarily committed for their “sex perversion,” with treatments such as lobotomy, castration, and electroshock therapy to cure homosexuality. These events effectively silenced the communication of thousands of lesbians and gay men, becoming a major impetus for them to camouflage for self-preservation. Yet, these events also served as a catalyst for political action. The Mattachine Society (1950), One, Inc., (1952), and The Daughters of Bilitis (1955) were three early organizations established for outreach and education in support of lesbians and gay men.

During their coming of age years (early 1960s through early 1970s), many from the Pride Generation (birth years circa 1950–1964) made their identities public through the emergent public resistance discourse of “pride and liberation.” It was also during this period that the umbrella term “homosexual” began to be differentiated by gender: lesbians (i.e., women), and gays (i.e., men). This generation experienced their childhood in the context of the Civil Rights Era (1954–1968), another historical event and a period of visible, and often violent civil unrest, alongside with the Women’s movement and sexual revolution with the advent of the birth control pill in 1960. This generation, perhaps more than any before, engaged in the mechanism of collective (i.e., community) agency which ties directly to activism and generativity as a way of moving forward.

A key historical event for the Pride Generation was Stonewall. Led by transgender women of color Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, and Black lesbian Stormé DeLarverie, lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) patrons of the Stonewall Inn fought back against routine police harassment and arrests, sparking 3 days of rioting (June 28–30, 1969). “Pride and liberation” became the rallying cry of the then modern LGBTrights movement, as older members of the Pride Generation were entering young adulthood. The 1970s saw a burgeoning of LGBT political action organizations, such as the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force (NGLTF), Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (PFLAG), and the Human Rights Campaign (HRC). This era also saw the counter-resistance deployment of powerful cultural emblems that signified the power of communal human agency. For example, in 1978, Gilbert Baker created the movement’s famous rainbow flag as a symbol to be used every year in the San Francisco’s Gay and Lesbian Pride Parade. Each color in the flag representing a different facet of gay and lesbian life and served the function of iridescent fluidity via shifting angles and perceptions. This period also saw the emergence of a new identity politics, as women and people of color became increasingly disenchanted with gay white male domination of the Pride movement, forming among others the National Organization of Women (NOW), the San Francisco’s Bisexual Center (first bisexual center in U.S.) in 1976, and the Salsa Soul Sisters - Third World Wimmin Inc., which until 1974 was the Black Lesbian Caucus.

Aims and Research Questions

Although there is increasingly more research on the health and well-being of sexual and gender minorities, there has generally been a lack of attention to similarities and differences between distinct generations and the historical influences that might account for such differences. In this paper, we utilize the Iridescent Life Course to assess the key life events of lesbians and gay men within a historical context and to understand the life events across three differing generations, including the Invisible, Silenced, and Pride Generation, while also taking into consideration gender differences. In this paper, we will investigate the following research questions:

How do demographic characteristics, key life events and experiences (related to identity, kin relations, work, bias experiences, and social engagement), and health and well-being differ between generations?

Are there interaction effects of gender by generation on key study variables?

Methods

Data and Sample

Aging with Pride: National Health, Aging, and Sexuality/Gender Study (NHAS) is the first ever national longitudinal study of LGBT adults aged 50 and older. In 2014, 2450 participants were recruited who were born in 1964 or earlier and either self-identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender or reported having engaged in same-sex sexual behavior or had a romantic relationship with, or an attraction to, someone of the same sex or gender. To reflect the heterogeneity of the population and minimize non-coverage bias, purposive stratified sampling by age cohort, gender, race/ethnicity, and geographic location was conducted based on power analysis and projected attrition rates. Participants were recruited from across all U.S. census divisions via contact lists from 17 community agencies providing LGBT aging services. Social network clustering chain referral was also used to recruit hard-to-reach and underrepresented populations. Participants completed their self-administered paper or online survey in English or Spanish, per their preference. Participants received $20 for their time. Study protocols were approved by the Human Subjects Division of the University of Washington. For a full description of study methods, see Fredriksen-Goldsen and Kim (2017).

This study sample is comprised of 838 lesbians (3.9% transgender/non-binary) and 1241 gay men (2.0% transgender/non-binary). The unweighted sample sizes of the respective historical generations are: Pride (born 1950–1964, n = 894), Silenced (1935–1949, n = 1011), and Invisible (1920–1934, n = 174). About 80% were non-Hispanic Whites (unweighted n = 1643), one third (33.2%, unweighted n = 686) lived at or under 200% of the federal poverty level, and slightly over a quarter (26.3%, unweighted n = 173) had an educational level of high school graduation or less. Over 40% (unweighted n = 1055) lived alone. Study measures are presented in Tables 1 and 2. To reduce sampling bias and enhance the generalizability, a post-survey adjustment was applied to the NHAS nonprobability sample. This adjustment procedure involves projecting the NHAS sample to the population using credible external population data, then generating and applying survey weights in analyses. Two-step post-survey adjustments were conducted (see Lee, 2006; Lee & Valliant, 2009).

Table 1.

Historic Events by Three Generational Cohorts of LGBTQ Older Adults.

| Ages in years when experienced |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Historic event | Year of event | Invisible (born 1920–1934) | Silenced (born 1935–1949) | Pride (born 1950–1964) |

|

| ||||

| Emergence of medical discourse of “sexual inversion” as illness | ~1860s | |||

| First known use of term “homosexual” in English language | 1892 | |||

| US immigration law modified to ban “persons with abnormal sexual instincts” from entering the United States | 1917 | |||

| First of Invisible Generation born (1920–1934) | 1920 | 0 | ||

| Society for Human Rights founded, first gay rights organization in US founded (disbanded in 1925) | 1924 | 0–4 | ||

| Harlem Renaissance emerges, revolutionizing sexual identity, desire, and behavior in urban spaces of color and creating art and literature inclusive of an expansive sexuality | 1925 | 0–5 | ||

| New York Assembly amends the state’s obscenity code to ban the appearance or discussion of homosexuality on the public stage | 1927 | 0–7 | ||

| Great Depression begins | 1929 | 0–9 | ||

| First of Silenced Generation born (1935–1949) | 1935 | 1–15 | 0 | |

| World War II begins | 1939 | 1–19 | 0–4 | |

| World War II ends | 1945 | 11–25 | 0–10 | |

| Alfred Kinsey states that sexual orientation lies on a continuum from exclusively homosexual to exclusively heterosexual | 1948 | 14–28 | 0–13 | |

| First of Pride Generation born (1950–1964) | 1950 | 16–30 | 1–15 | 0 |

| Lavender Scare, a witch-hunt against homosexuals begins | 1950 | 16–30 | 1–15 | 0 |

| Homosexuality designated mental illness in DSM-I | 1952 | 18–32 | 3–17 | 0–2 |

| Christine Jorgensen is the first known American to receive gender reassignment surgery | 1952 | 18–32 | 3–17 | 0–2 |

| Mandated firing of federal and civilian homosexual employees | 1953 | 19–33 | 4–18 | 0–3 |

| McCarthy hearings broadcast on television | 1954 | 20–34 | 5–19 | 0–4 |

| Illinois becomes first state to decriminalize sodomy | 1962 | 28–42 | 13–27 | 0–12 |

| Civil Rights Act | 1964 | 30–44 | 15–29 | 0–14 |

| Stonewall Riots | 1969 | 35–49 | 20–34 | 5–19 |

| Homosexuality as pathology removed from DSM-II-R | 1973 | 39–53 | 24–38 | 9–23 |

| Gender identity differentiated from homosexuality in DSM-III | 1980 | 46–60 | 31–45 | 16–30 |

| 159 cases reported of what would come to be known as HIV/AIDS | 1981 | 47–61 | 32–46 | 17–31 |

| Total US AIDS cases reported1: 733,374; dead: 429,825 | 1989 | 55–69 | 40–54 | 25–39 |

| “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” military policy enacted | 1994 | 60–74 | 45–59 | 30–44 |

| First protease inhibitors approved; HIV/AIDS soon becomes chronic | 1995 | 61–75 | 46–60 | 31–45 |

| Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) enacted | 1996 | 62–76 | 47–61 | 32–46 |

| US Supreme Court rules sodomy laws unconstitutional | 2003 | 69–83 | 54–68 | 39–53 |

| Massachusetts first state to legalize same-sex marriage | 2004 | 70–84 | 55–69 | 40–54 |

| Federal Employment Non-Discrimination Act adds sexual orientation as protected class in hiring practices; does not include gender ID | 2007 | 73–87 | 59–64 | 43–57 |

| Matthew Shepard and James Boyd Jr. Hate Crime Protections Act expands hate crime protections to include sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, and disability | 2009 | 75–89 | 60–74 | 45–59 |

| Hospital visitation rights are revised to allow patients to designate their own visitors, including same-sex partners and non-traditional family | 2010 | 76–90 | 61–75 | 46–60 |

| “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” military policy ended | 2011 | 77–91 | 62–76 | 47–61 |

| Supreme Court strikes down Section III of DOMA | 2013 | 79–93 | 64–78 | 49–63 |

| Gender Identity Disorder becomes Gender Dysphoria in DSM-5 | 2013 | 79–93 | 64–78 | 49–63 |

| Same-sex marriage legalized in US | 2015 | 81–95 | 66–80 | 51–65 |

| Stonewall Inn designated national monument | 2016 | 82–96 | 67–81 | 52–66 |

| Transgender military ban repealed | 2016 | 82–96 | 67–81 | 52–66 |

| Transgender military ban reinstated | 2017 | 83–97 | 68–82 | 53–67 |

| Danica Roem becomes first openly transgender person to be elected and serve in any U.S. state legislature | 2017 | 83–97 | 62–82 | 53–67 |

| Pete Buttigieg becomes first out gay man to run for U.S. president | 2019 | 85–99 | 64–84 | 55–69 |

| Stonewall Riots 50th anniversary | 2019 | 85–99 | 64–84 | 55–69 |

| “They” becomes Merriam Webster’s word of the year | 2019 | 85–99 | 64–84 | 55–69 |

| Supreme Court rules civil right law protects LGBT employee from being fired | 2020 | 86–100 | 66–86 | 57–71 |

Table 2.

Description of Measures.

| Variables | Items/description |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Identity | |

| Age at awareness | A question asking for age in years when participants first became aware of their sexual/gender identity. Range = 0–72 |

| Age at disclosure | A question asking for age in years when participants first disclosed their sexual/gender identity. Range = 2–77 |

| Time in closet | Difference in years between age at first disclosure and age at first awareness. Range = 0–68 |

| Outness | A single item of participants’ self-rating on their level of visibility with respect to being LGBT. Ranges from 1 (= never told anyone) to 10 (= told everyone) |

| Identity stigma | Mean scores of 4 items assessing negative attitudes and feelings toward their sexual/gender identity (Herek et al., 2009), including “I feel ashamed of myself for being LGBT.” Ranges from 1 (= strongly disagree) to 6 (= strongly agree), and α = 0.82 |

| Kin relations | |

| Never married/partnered | Whether participants have never been married or partnered (n = 186) |

| Different-gender marriage | Whether participants have ever been in a different-gender marriage (n = 581) |

| Married or partnered | Whether or not participants are currently married/partnered (unweighted n = 960) |

| Death of a partner/spouse | Whether or not participants have ever experienced death of a partner or spouse (unweighted n = 590) |

| Ex-spouse/partner | Whether or not participants have an ex-spouse/partner in close relationship (n = 936) |

| # Living children | Number of living children in close relationship, rounded to 10 for 11 or higher. Range = 0–10 |

| Close family | Number of family other than child in close relationship, rounded to 10 for 11 or higher. Range = 0–10 |

| Work | |

| Retired, current | Whether or not participants are currently retired (n = 911) |

| Military service | Whether or not participants have ever served in the military (n = 360) |

| Not promoted | Whether or not participants have ever experienced workplace discrimination of not being promoted for being or being thought of as LGBT (n = 517) |

| Fired from job | Whether or not participants have ever experienced workplace discrimination of not being fired from job for being or being thought of as LGBT (n = 318) |

| Bias experiences | |

| Lifetime victimization | Summed scores of the frequencies of experiencing nine types of victimization (e.g. verbal and physical threat, verbal, physical, and sexual assault) during the lifetime as a result of their sexual orientation or gender identity or expression (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Kim, 2017). 0 = never to 3 = three or more times; Ranges = 0– 27. α = 0.84 |

| Property damaged | Whether or not participants have ever experienced their property being damaged or destroyed for being or being thought of as LGBT (n = 480) |

| Threatened to out | Whether or not participants have ever experienced someone threatening to out them for their LGBT identity (n = 479) |

| Hassled by police | Whether or not participants have ever been hassled by police for being or being thought of as LGBT (n = 502) |

| Denied/inferior care | Whether or not participants have ever been denied or provided inferior health care for being or being thought of as LGBT (n = 270) |

| Social engagement | |

| Attend meeting/group activities | Whether or not participants have on some or more days in the past month attended club meetings or group activities (n = 1193) |

| Socialization | Whether or not participants have on some or more days in the past month socialized with friends/family (n = 1867) |

| Community activism | Whether or not participants agree with the statement, “I actively participate to challenge discrimination” (n = 1519) |

| LGBT Community engagement | Mean scores of 4 items of the LGBT Community engagement scale (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Kim, 2017). Items include “I am active or socialize in the community”: 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree. Range = 1 – 6. α = 0.85 |

| Spirituality | Mean scores of 4 items of the Spirituality scale (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Kim, 2017), measuring spiritual beliefs, meaning, and support (Fetzer Institute, 1990). Items include “I believe in a higher power or God who watches over me” (1 = strongly disagree; 6 = strongly agree). Range = 1–6. α = 0.92 |

| Health/well-being | |

| Physical impairment | Mean scores of 8 items assessing physical functioning defined as difficulty with lower and upper extremity performance (Fredriksen-Goldsen & Kim, 2017). Items include walking a quarter of a mile or standing on your feet for about 2 hours or sitting for about 2 hours: 0 = no difficulty to 4 = extremely difficulty or cannot do; α = 0.90 |

| HIV/AIDS | Whether or not participants have ever been diagnosed with either HIV or AIDS, or both (n = 345) |

| Depressive symptomatology | Dichotomized variable of clinical significance based on summed scores of 10 items of the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D 10; Andresen et al., 1994): 0 = less than one day to 3 = five to seven days. Dichotomized the summed score greater than 10 versus 10 or smaller |

| Quality of life | WHO Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF; Bonomi et al., 2000), a single-item overall quality of life assessed by, “How would you rate your quality of life” (1 = very poor to 5 = very good). Scores calculated according to the WHO guidelines, range 1–5 |

| Background characteristics | Age in years, gender (lesbians vs. gay men), income (living at or below 200% of federal poverty level (FPL) versus > 200% FPL), education (high school or less vs. some college or more), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic Whites vs. people of color), gender identity (transgender or gender diverse/non-binary vs. cisgender), living arrangement (living alone or not) |

Note. n provided in the table is an unweighted n)

Analyses

We used Stata/MP 16.0 and applied survey weights throughout the analysis. First, we ran descriptive statistics (means with standard errors or weighted percentages, as appropriate) for sociodemographic variables and compared them among the three generations and between lesbians and gay men via chi-square tests. Second, we compared life events and experiences (e.g., identity development, kin relations, work, bias experiences, social engagement, and health and well-being) among the three generations and between lesbians and gay men using linear or logistic regressions as appropriate, controlling for race/ethnicity, income, and education. The Pride Generation (vs. Silenced and Invisible) and lesbians (vs. gay men) were coded as the reference groups. Additional analyses were conducted to compare the Silenced and Invisible generations. Third, we added an interaction term of gender and generations to each regression model to examine patterns of gender differences in life events and experiences by generation.

Findings

Sociodemographic Differences by Generation.

As shown in Table 3, the mean ages were 57, 70, and 84 in the Pride, Silenced, and Invisible generations, respectively. While lesbians make up over 40% of the Pride and Silenced generations, less than 20% of the Invisible Generation were lesbians. Income (assessed as ≤ 200% FPL) and education level (measured as high school/GED or less) were not statistically different by generation. However, the proportion of people of color did differ. While slightly over a quarter of the Pride Generation were people of color, only 10% of the Silenced Generation and 5% in the Invisible Generation were people of color. The rate of living alone was the highest in the Invisible Generation (57.7%) followed by the Silenced Generation (50.6%), and the Pride Generation (39.6%). Table 4

Table 3.

Sociodemographic Characteristics by Generational Age Cohort and Gender (Lesbians and Gay Men).

| Generational age cohort |

Lesbians/Gay men |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total (n = 2079) |

Pride (Ref; n = 894) |

Silenced (n = 1011) |

Invisible (n = 174) |

Lesbians (n = 838) |

Gay men (n = 1241)< |

|||

| % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | % (SE) | F | % (SE) | % (SE) | F | |

|

| ||||||||

| Age, M

Lesbians |

61.56 (0.28) 43.05 (0.02) |

57.00 (0.20) 45.04 (0.02) |

70.24 (0.23) 40.95 (0.03) |

84.02 (0.32) 19.23 (0.03) |

2748.81***

7.03** |

60.85 (0.40) | 62.10 (0.38) | 5.19* |

| Income, ≤200% FPL | 33.15 (0.02) | 34.27 (0.02) | 30.17 (0.03) | 34.73 (0.05) | 1.06 | 30.03 (0.03) | 35.49 (0.02) | 2.28 |

| Education ≤ High school | 26.29 (0.02) | 25.77 (0.02) | 28.45 (0.03) | 19.36 (0.05) | 0.66 | 28.00 (0.03) | 24.04 (0.03) | 0.98 |

| People of color Transgender/gender diverse or non-binary | 20.47 (0.02) 2.81 (0.06) | 25.29 (0.02) 3.41 (0.01) | 10.24 (0.02) 1.13 (0.00) | 4.81 (0.01) 4.32 (0.03) | 27.63*** 4.42* | 23.37 (0.03) 3.93 (0.01) | 18.28 (0.02) 1.97 (0.01) | 2.44 2.93 |

| Live alone | 43.20 (0.02) | 39.55 (0.02) | 50.60 (0.03) | 57.67 (0.05) | 9.23*** | 37.19 (0.03) | 47.75 (0.02) | 8.31** |

Notes. Survey weights were applied. FPL = Federal Poverty Level.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Table 4.

Life Events, Experiences, and Health and Well-being of Lesbian and Gay Older Adults by Generational Age Cohort.

| Total |

Pride |

Silenced |

Invisible |

Pride (Ref) versus Silenced b or AOR (SE) | Pride (Ref) versus Invisible b or AOR (SE) | Silenced (Ref) versus Invisible b or AOR (SE) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Identity | Age at awareness, M (SE) | 19.09 (0.39) | 18.57 (0.51) | 20.62 (0.60) | 17.01 (0.88) | 1.89 (0.75)* | −0.68 (0.97) | −2.57 (0.99)** |

| Age at disclosure, M (SE) | 25.61 (0.44) | 24.54 (0.57) | 28.21 (0.66) | 27.13 (1.38) | 3.20 (0.87)*** | 2.87 (1.50) | −0.33 (1.53) | |

| Time in closet, M (SE) | 6.31 (0.35) | 5.86 (0.46) | 7.19 (0.49) | 9.00 (1.19) | 1.17 (0.71) | 2.82 (1.32)* | 1.65 (1.32) | |

| Outness, M (SE) | 8.50 (0.08) | 8.64 (0.10) | 8.26 (0.12) | 7.53 (0.28) | −0.40 (0.15)* | −1.02 (0.29)*** | −0.63 (0.29)* | |

| Identity stigma, M (SE) | 1.49 (0.03) | 1.49 (0.04) | 1.46 (0.04) | 1.67 (0.08) | −0.02 (0.05) | 0.17 (0.09) | 0.18 (0.09)* | |

| Kin relations | Never married/never partnered, % (SE) | 8.04 (0.01) | 8.73 (0.01) | 6.30 (0.01) | 8.28 (0.02) | 0.80 (0.21) | 0.72 (0.26) | 0.91 (0.32) |

| Different-gender marriage, % (SE) | 27.40 (1.65) | 23.97 (0.02) | 36.48 (0.03) | 23.29 (0.04) | 1.87 (0.32)*** | 1.21 (0.31) | 0.65 (0.16) | |

| Married/partnered, % (SE) | 52.34 (0.02) | 53.64 (0.02) | 49.76 (0.03) | 46.75 (0.05) | 0.80 (0.13) | 0.81 (0.17) | 1.02 (0.22) | |

| Death of a partner/spouse, % (SE) | 26.18 (0.02) | 23.82 (0.02) | 28.90 (0.02) | 52.64 (0.05) | 1.44 (0.25)* | 3.25 (0.76)*** | 2.27 (0.51)*** | |

| Ex-spouse/partner, close, % (SE) | 38.89 (0.02) | 37.98 (0.02) | 41.86 (0.03) | 33.05 (0.05) | 1.24 (0.19) | 1.09 (0.28) | 0.88 (0.23) | |

| Living children, close, M (SE) | 0.42 (0.04) | 0.45 (0.05) | 0.39 (0.05) | 0.20 (0.05) | −0.02 (0.07) | −0.12 (0.06) | −0.10 (0.07) | |

| Other immediate family, close, M (SE) | 2.33 (0.10) | 2.47 (0.13) | 1.96 (0.16) | 2.30 (0.33) | −0.46 (0.21)* | −0.10 (0.37) | 0.36 (00.37) | |

| Work | Retired, current, % (SE) | 28.80 (0.01) | 10.63 (0.01) | 66.69 (0.03) | 86.61 (0.03) | 16.33 (2.87)*** | 49.37 (14.00)*** | 3.02 (0.80)*** |

| Military service, % (SE) | 13.38 (0.01) | 6.30 (0.01) | 25.37 (0.03) | 60.47 (0.05) | 4.58 (1.22)*** | 19.67 (5.88)*** | 4.29 (0.98)*** | |

| Not promoted, % (SE) | 25.52 (0.02) | 27.82 (0.02) | 21.01 (0.02) | 14.98 (0.04) | 0.69 (0.12)* | 0.39 (0.14)** | 0.57 (0.21) | |

| Fired from job, % (SE) | 16.78 (0.01) | 19.13 (0.02) | 1 1.92 (0.02) | 8.44 (0.02) | 0.58 (0.12)** | 0.35 (0.1 1)** | 0.61 (0.20) | |

| Bias experiences | Lifetime victimization, M (SE) | 4.65 (0.20) | 5.17 (0.27) | 3.54 (0.20) | 3.15 (0.32) | −1.70 (0.34)*** | −2.56 (0.46)*** | −0.86 (0.40)* |

| Property damage, % (SE) | 25.64 (0.02) | 28.41 (0.02) | 20.01 (0.02) | 14.93 (0.03) | 0.63 (0.1 1)** | 0.39 (0.12)** | 0.62 (0.19) | |

| Threatened to out, % (SE) | 25.16 (0.02) | 26.40 (0.02) | 22.96 (0.02) | 17.87 (0.03) | 0.82 (0.14) | 0.59 (0.16)* | 0.72 (0.19) | |

| Hassled by police, % (SE) | 24.64 (0.02) | 25.73 (0.02) | 21.74 (0.02) | 25.95 (0.04) | 0.78 (0.14) | 0.88 (0.23) | 1.13 (0.30) | |

| Denied care/inferior care, % (SE) | 13.90 (0.01) | 16.46 (0.02) | 8.40 (0.01) | 6.44 (0.02) | 0.49 (0.10)** | 0.29 (0.1 1)** | 0.60 (0.24) | |

| Social | Attend meeting/group activities, % (SE) | 53.49 (0.02) | 50.76 (0.02) | 59.55 (0.03) | 59.76 (0.05) | 1.53 (0.23)** | 1.53 (0.37) | 1.00 (0.24) |

| engagement | Socialize with friend and family, % (SE) | 89.33 (0.01) | 87.92 (0.02) | 92.17 (0.02) | 94.74 (0.02) | 1.53 (0.47) | 2.35 (0.94)* | 1.54 (0.68) |

| Community activism, % (SE) | 74.69 (0.02) | 73.21 (0.02) | 78.42 (0.02) | 75.22 (0.04) | 1.32 (0.24) | 0.95 (0.24) | 0.72 (0.19) | |

| LGBT community engagement, M (SE) | 3.86 (0.05) | 3.83 (0.06) | 3.92 (0.07) | 3.95 (0.10) | 0.13 (0.09) | 0.14 (0.13) | 0.02 (0.13) | |

| Spirituality, M (SE) | 3.77 (0.06) | 3.81 (0.08) | 3.71 (0.08) | 3.30 (0.16) | 0.04 (0.12) | −0.27 (0.18) | −0.30 (0.18) | |

| Health and well-being | Physical impairment, M (SE) | 0.79 (0.03) | 0.76 (0.05) | 0.81 (0.05) | 1.14 (0.08) | 0.09 (0.06) | 0.48 (0.10)*** | 0.39 (0.10)*** |

| HIV/AIDS, % (SE) | 20.05 (0.02) | 23.60 (0.02) | 13.34 (0.02) | 2.19 (0.01) | 0.47 (0.12)** | 0.04 (0.02)*** | 0.09 (0.05)*** | |

| Depressive symptomatology, % (SE) | 30.30 (0.02) | 35.1 1 (0.02) | 19.26 (0.02) | 22.25 (0.04) | 0.43 (0.08)*** | 0.52 (0.14)* | 1.21 (0.35) | |

| Quality of life, M (SE) | 4.05 (0.04) | 3.95 (0.05) | 4.27 (0.04) | 4.18 (0.05) | 0.32 (0.07)*** | 0.25 (0.08)** | −0.07 (0.07) | |

Note. Survey weights were applied. With the Pride Generation as the reference category, comparisons were made for the Silenced and Invisible generations. Additional linear (for continuous variables) or logistic (for binary variables) regression analyses were run to make comparisons between the Silenced and Invisible generations. Findings were adjusted for income (<200% FPL vs. 200% FPL or more), education (high school or less vs. some college or more), and race/ethnicity (Non-Hispanic white vs. people of color). LGBT: Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Life Events and Experiences by Generation

The Silenced Generation became aware of their sexual identities at an average age of 20.6 years old, significantly older than the Pride Generation (b = 1.89, p < .05); and the Invisible Generation did so at a younger age than the Silenced Generation (b = −2.57, p < .01). The average age of identity disclosure of the Silenced Generation was 28.2 years old and also significantly older than the Pride Generation (b = 3.20, p < .001). Time in closet, the difference in years between the age at which participants became cognizant of their sexual identities and their age when they first disclosed that identity to someone else, was longer for the Invisible Generation than the Pride Generation (b = 2.82, p < .05). Outness level—openness about their sexual identities—for the Pride Generation was significantly higher than the Silenced (b = −0.40, p < .05) and Invisible (b = −1.02, p < .001) generations. The Silenced Generation also had a significantly higher outness level than the Invisible Generation (b = −0.63, p < .05). Identity stigma was higher in the Invisible Generation than the Silenced Generation (b = 0.18, p < .05).

The Silenced Generation was significantly more likely to have ever been in a different-gender marriage (AOR = 1.9, p < .001), and to have experienced the death of a partner or spouse (AOR = 1.4, p < .05), as compared with the Pride Generation. The Invisible Generation was more likely to have experienced the death of a partner or spouse than the Silenced Generation (AOR = 2.3, p < .001) and the Pride Generation (AOR = 3.3, p < .001). The Silenced Generation had fewer close immediate family members other than children compared to the Pride Generation (b = −0.46, p < .05).

The Silenced Generation was more likely than the Pride Generation to be retired (AOR = 16.3, p < .001) and to have served in the military (AOR = 4.6, p < .001). The Invisible Generation was more likely to be retired and to have served in the military than the Pride Generation (AOR = 49.4 and 19.7, respectively, p < .001) and the Silenced Generation (AOR = 3.0 and 4.3, respectively, p < .001). The Silenced and Invisible generations were less likely than the Pride Generation to report having not been promoted (AOR = 0.7, p < .05; AOR = 0.4, p < .01, respectively) and having been fired from a job (AOR = 0.6, p < .01; AOR = 0.4, p < .01, respectively) due to their sexual identity.

The Silenced and Invisible generations had higher rates of lifetime victimization related to their sexual/gender identity than the Pride Generation (b = −1.7, p < .001; b = 2.56, p < .001, respectively). The Invisible Generation was victimized less than the Silenced Generation (b = −0.86, p < .05). The Silenced and Invisible generations were less likely to have had their property damaged or destroyed than the Pride Generation (AOR = 0.6, p < .01; AOR = 0.4, p < .01, respectively). The Invisible Generation was also less likely to have experienced someone threatening to out them (i.e., disclose their sexual identity) than the Pride Generation (AOR = 0.6, p < .05). The Silenced and Invisible generations were less likely to have been denied or provided with inferior health care than the Pride Generation (AOR = 0.5, p < .01; AOR = 0.3, p < .01, respectively).

The Silenced Generation was more likely to have attended club meetings or group activities in the past month than the Pride Generation (AOR = 1.5, p < .01), and the Invisible Generation was more likely to have socialized with friends and family than the Pride Generation in the past month (AOR = 2.4, p < .05). LGBT community engagement, spirituality, and community activism did not differ by generation.

Health and Well-Being by Generation

The Invisible Generation had higher degrees of physical impairment than the Pride (b = 0.5, p < .001) and Silenced (b = 0.4, p < .001) generations. The Silenced and Invisible generations were less likely to have HIV/AIDS than the Pride Generation (AOR = 0.5, p < .01; AOR = 0.04, p < .01), and the Invisible Generation was less so than the Silenced Generation (AOR = 0.1, p < .001). The Silenced and Invisible generations were less likely to have depressive symptomatology than the Pride Generation (AOR = 0.4, p < .001; AOR = 0.5, p < .05). The overall quality of life was lower in the Pride Generation than the Silenced (b = 0.3, p < .001) and Invisible generations (b = 0.3, p < .01).

Interaction with Gender

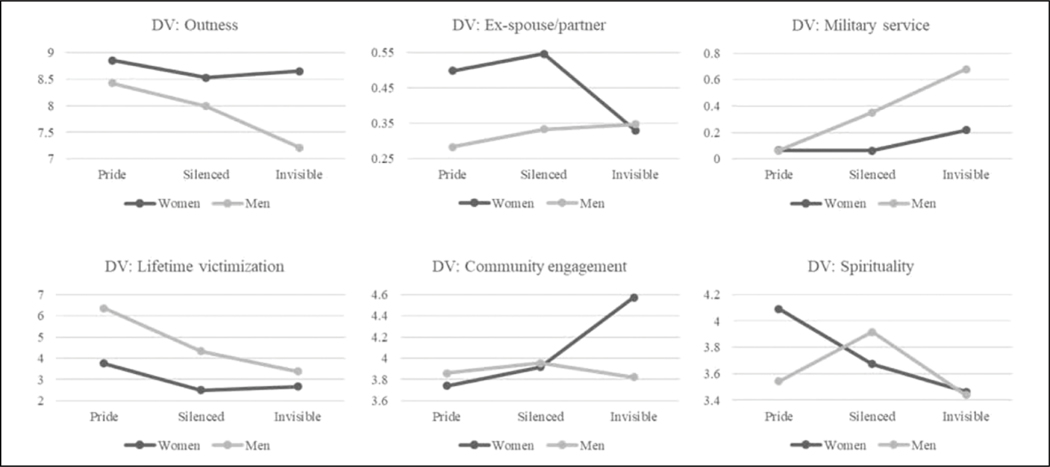

As the interaction model in Figure 1 shows, a lower level of outness (lower among gay men than lesbians), was stronger in the Invisible Generation than the Pride and Silenced generations. A lower likelihood of gay men compared to lesbians having a close relationship with an ex-partner or ex-spouse was only found in the Pride (AOR = 0.4, p < .001) and the Silenced (AOR = 0.4, p < .001) generations, and there was no gender difference in this likelihood in the Invisible Generation. A higher likelihood of military services among gay men than lesbians was found in the Silenced (AOR = 9.0, p < .001) and Invisible generations (AOR = 8.4, p < .001), but not in the Pride Generation. Gay men had higher rates of victimization than lesbians in the Pride (b = 2.6, p < .001) and Silenced (b = 1.9, p < .001) generations, but there was no gender difference in the Invisible Generation.

Figure 1.

Interaction effects of generational age cohort and gender.

Gay men were less engaged in the LGBTcommunity than lesbians in the Invisible Generation (b = −0.8, p < .01), but there were no gender differences in the Pride and Silenced generations. Spirituality was lower among gay men than lesbians in the Pride Generation (b = −0.6, p < .001), but no gender differences in spirituality level were found in the Silenced Generation as well as the Invisible Generation.

Discussion

Our goal in this paper was to explore the historical and social forces at play in the lives of lesbian and gay older adults by three historical generations. By employing the Iridescence Life Course framework, we examined how key life events unfold differently by generation, gender, and sexual orientation, exemplifying fluidity, and at the same time employing intersectionality in order to more fully appreciate the rich variability and heterogeneity of these populations. Addressing the intersectionality of these social locations is critical to moving this field forward (Fredriksen Goldsen et al., 2019; Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2014). The Iridescent Life Course extends existing work by incorporating the intersectionality of sexuality and gender, and considers how these positions interact to shape opportunities and constraints—the downward delimiting of sociocultural pressures juxtaposed with bottom-up individual and group resistance through human agency.

Sociodemographic Differences by Generation

Beginning our analysis of relevant sample characteristics, we noted that income and education levels were not significantly different by generation, which departs from differing generations in the general population (Corak, 2013). Perhaps lesbians and gay men across the generations were in lower-paying jobs as a result of camouflaging sexual identities, as promotions and higher-paying positions typically engage higher levels of scrutiny (Canaday, 2009). Additionally, long-standing discriminatory public policies may further worsen income or educational inequities. Older lesbians and gay men were at risk for being arrested on “morals charges” well into the 1960s. A felony record has serious negative impacts on obtaining employment and federal student aid. Another example is a report from the General Accounting Office (General Accounting Office, 2004) that identified 1138 rights, benefits, and privileges that were conferred with heterosexual marriage prior to the Supreme Court of the United States ruling of full marriage equality in the Obergefell v Hodges (2015) case. Prior to the full recognition of marriage equality in 2015, lesbians and gay men across generations were excluded from several benefits, including Social Security spousal retirement, survivors, and disability benefits (Burda, 2016). Such benefits often accrue over time and can be dependent on wage earnings and marital status. Thus, lesbians and gay men have historically been and continue to be at a distinct disadvantage across generations in terms of income, which may extend into retirement. The findings revealed that the likelihood of living alone increases for older generations with gay men being at higher risk of living alone compared to lesbians, which we have found in some of our population-based research (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2013). Living alone further impacts income and restricts opportunities for upward social class mobility, highlighting limitations of fluidity from an iridescent perspective. Additionally living alone increased the likelihood of loneliness which can have deleterious effects on well-being (Yang et al., 2018).

We also found that older generations in this study were less diverse. There appears to be less heterogeneity in terms of sexual identities and race/ethnicity within the Invisible and Silenced generations compared to the Pride Generation. In some ways, this is reflective of larger cultural and historical contexts of the first part of the 20th century when language around diverse sexual and gender identities was limited. As previously discussed, it was not until 1980 that the American Psychiatric Association disentangled sexual orientation from gender identity. There are fewer lesbians in the Invisible Generation, compared to the Silenced and Pride generations. Historical events may provide some context for this generational difference. For example, “Boston marriages” was a cultural script available to some women from the late 19th into the early 20th century. It afforded some women respectability and accessibility not available to many men (Fredriksen-Goldsen et al., 2009), and was far less rigid and delimited. The relationship might have been intimate in nature—romantic, erotic, or philia; the arrangement may also have been for business purposes, combining resources for economic benefit. There is also some possibility that the “language of lesbianism” may not have been available to women in the same way homosexuality was for men, considering one of the dominant tropes was gay men as pedophiles (Canaday, 2009). This historical phenomenon is consistent with the concept of courtship and sexual selection emanating from the Iridescent Life Course.

There were fewer people of color in the Invisible Generation than the Silenced and Pride generations. This provides preliminary evidence of main effects by historical generational identity, similar to other diverse populations, dictating a potential interaction effect of generational identity by race and ethnicity. This finding may reflect selection bias (Mayeda et al., 2016); it may also signify within group differences by race and ethnicity in that, for example, African American and Latinx populations may be less likely to identify as gay or lesbian, although their primary sexual behaviors may be predominantly same-gender by nature (Chae et al., 2010). Related to this, differential language and its fluidity from an Iridescent perspective may also be at play as “same-gender loving” may be construed as different from lesbian and gay in African American communities (Truong et al., 2016).

We also noted significant differences between generations with regard to the proportion of people of color. There are a number of potential reasons for this. First, African Americans in general, and African American men in particular, may be less likely to participate in research as a result of the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment (Green et al., 1997). Second, due to well-established research on the social determinants of health disparities, survival bias may also be an issue (Mayeda et al., 2016). For example, it was not until 1948 that President Truman signed Executive Order 9981, ostensibly eliminating discrimination in the U.S. military. Prior to this executive order, the military was as explicitly Jim Crow as the rest of American society, with African American soldiers disproportionately represented in combat units, increasing their risk of becoming casualties of war (Dwyer, 2006). Yet this disproportionality remains even today, which reflects structural oppression despite institutional policies.

Life Events and Experiences by Generation

The Silenced Generation was older when they first became aware of and disclosed their identity compared to the Pride Generation, while the Invisible Generation stayed longer in the closet than the Pride Generation. The Invisible Generation is the least visible (hence “invisible”), and the level of identity stigma among the Invisible Generation was higher than the Silenced Generation. From an Iridescent perspective intersecting with Foucault’s (1978) The History of Sexuality and its focus on language as the conveyance of power, there was no widespread public discourse (although there certainly was parlor room gossip), which further exemplifies the social fluidity function of Iridescence. After all, parlor rooms as a semi-private cultural space in the first three decades of the 20th century indicate exclusion of those who did not have upper- or middle-class status. These findings also highlight the Iridescent constructs of identity, timing, and context. How individuals from the Invisible Generation were identified was contextualized by timing (the era in which they lived). The Pride Generation was the most visible. The Silenced Generation was older than the Pride and Invisible generations when they first became aware of their sexual identities, and the Silenced Generation were older than the Pride Generation when they first disclosed their sexual identities. While the Invisible Generation had little, if any, context for coming out, the Silenced Generation began coming of age in the post-WWII years had a definitive negative context. Whereas the locus of discourse regarding sexualities in the early part of the 20th century was primarily the aforementioned “parlor rooms,” the 1950s “Lavender Scare” of the McCarthy era beamed discourses of “homosexual perversion, disgust, and threats to national security” directly into millions of living rooms across the nation (Canaday, 2009). Literally fearing for life and limb, it would make sense that nascent awareness of lesbian and gay identities would be repressed, denied, and hidden for as long as possible to avoid being targeted as a “disgusting, perverted threat to national security.”

The two oldest generations are the most likely to be retired, especially the Invisible Generation, which is congruent with traditional conceptions of life course theory. During their working lives, the Invisible and Silenced generations were less likely to experience job discrimination than the Pride Generation, perhaps due to utilizing the protection of camouflage. Non-disclosure, as described here, is consistent with the concept of camouflage identified as a component of the Iridescent Life Course. While the Pride Generation may have come out in a more open environment (time and context), there were costs. Among the Pride Generation, over 19% reported being fired for reasons related to sexual identity, while 27.8% were denied promotion, and 28.6% experienced hiring discrimination. When one engages in the idea of collective agency as the Iridescent Life Course illustrates, there are costs and potentially negative consequences of intentional actions to move social justice forward. This phenomenon may be at play here when we examine the impact on the Pride Generation versus previous generations.

Gender difference in outness was most salient among the Invisible Generation. While there were increases in camouflaging by age group, these increases were more pronounced among gay men. This can be understood as an intersectional manifestation of the emic of gender socialization and the cultural scripts available to women and men in respective generational cohorts. For example, gay men were simultaneously stereotyped as child molesters and as eschewing the cultural ideals of masculinity—aggressive, independent, and powerful. During the 1960s with the rise of the women’s movement, women began to flex “power,” exemplifying the ideals of individual versus collective agency.

The Silenced Generation had more likely been in a different-gender marriage than the Pride Generation, and also had fewer close family members. Considering the vitriol and very real possibility of being publicly exposed as lesbian or gay, mixed-gender marriage may have been a crucial tool in camouflaging one’s lesbian or gay identity. The older generations were also more likely to have experienced the death of a partner or spouse, which is not surprising in light of the reality that the older one becomes, the more likely they are to experience the loss of important social relationships (Antonucci et al., 2013). While the likelihood of having a close ex-partner/spouse did not differ by generation overall, lesbians were more likely than gay men in the Pride and Silenced generations to have a close relationship with an expartner/spouse, a pattern absent from the Invisible Generation. This may be due to mortality attrition (e.g., greater likelihood that the ex-partner/spouse is deceased) but may also be a result of time and location. The greater the arc of time, the greater the possibility of people changing their geographical location. The greater the distance in both geographic and temporal locations, the more tenuous the linkages of lives become.

As one would expect, the Invisible Generation was less likely to be partnered/married (46.8%) and more likely to have experienced the death of a partner or spouse (52.6%) compared to the others.

Although the number of living children and the number of close children was not different by generation, there was a lower number of close children compared to the number of children overall. For example, despite that the Invisible Generation averaged 2.3 living children, the average reported number of close children was 0.2. There are psychological, social, and legal reasons why estrangement from children and close family was the norm for lesbians and gay men during this era (Hanson, 2006). Casting out the stigmatized has often been defined historically to protect families, communities, and even society itself (Goffman, 1963; Matsumoto & Hull, 1994).

As occurs in the general population and would be expected, the older two cohorts compared to the youngest, and men compared to women were more likely to have served in the military, with 60.5% of the Invisible Generation and 25.4% of the Silenced Generation reporting having served, as opposed to 6.3% of the Pride Generation. Prior to the Vietnam War (e.g., WWII, Korean Conflict), military service was expected of all classes and was considered a patriotic duty (Hoy-Ellis et al., 2017). In addition, an estimated 10 million men were inducted into the military during World War II. Additionally, we must remember the Selective Service draft was in place until 1973 and applied to men only. Military service experience by generation was more salient among gay men cross-generationally, with the difference in the military service experience rate between lesbians and gay men the most pronounced among the Invisible Generation and decreasing over generations.

The Pride Generation experienced more discrimination in the workplace and health care settings and were victimized more frequently than the Invisible and Silenced generations, including property damage, physical and verbal threats, and being hassled by the police. As gay men and lesbians’ lives became more visible (less camouflaged), so too did they become more visible targets for discrimination. The chronic heterosexism that continues to permeate society fosters the victimization of lesbians and gay men which we see play out in the Pride Generation. Specifically, the Pride Generation experienced greater victimization than the Silenced and Invisible generations, and the Silenced Generation more so than the Invisible Generation. The Pride Generation was more likely to have their property damaged or destroyed than the Silenced and Invisible generations and more likely to have had someone threaten to “out them” than the Invisible Generation. Gay men had more victimization experiences due to their sexual/gender identity than lesbians in the Pride and Silenced generations, but there was no gender difference in the Invisible Generation. Research has continued to accumulate evidence that while all LGBT people are at risk for victimization, those perceived to be gay men often experience higher rates than those perceived to be lesbian (Gordon & Meyer, 2007; Herek, 2009). This makes sense from both historical constructions of gay men as preying on youth, intersecting with violations of masculine gender norms. It is also emblematic of the Iridescent Life Course in that the impacts of life course events and experiences differ not only by generation—but also gender. The Pride Generation was also more likely to have been denied or provided with inferior health care than the Silenced and Invisible generations, which also makes sense in that greater visibility also makes one a more visible target for differing types of discrimination and social exclusion.

While there was not a difference in spirituality by generation, spirituality levels were higher in the Silenced than the Pride Generation among gay men, which was reversed among lesbians whose spirituality was higher in the Pride than the Silenced Generation. Whereas lesbians in the Pride Generation showed higher spirituality than gay men, this was not significantly different among the Silenced and Invisible generations. Perhaps for the younger women, the church affirming movement may have created greater access for them to supportive spiritual and/or religious communities. Our findings also mirror those from the Pew Research Center who found that in recent years, the percentage of the population who are not atheist or agnostic but identify their religious affiliation as “nothing in particular” is consistently on the rise (Pew Research Center, 2019).

Interestingly, there were no generational differences in community activism or LGBT community engagement. However, the Silenced and Invisible generations were more likely to attend club meetings or group activities when compared with the Pride Generation. In the oldest generations, it may have been necessary to join clubs and social groups to build their communities. In fact, the Invisible Generation showed higher rates of going out to socialize with friends than the Pride Generation. This is also likely influenced by what Putnam (2000) considers in the decline of social capital in America, especially with the advent of television which makes it easier to “view” the world, and not “actively engage” with the world. In future research, it will be important to further assess the role of social media among the Pride Generation and other generations, as a tool for developing connections.

The rates of LGBT community engagement did not differ between lesbians and gay men in the Pride and Silenced generations. Lesbians in the Invisible Generation were more likely to be engaged in the LGBT community than gay men, as well as lesbians in the younger generations. It may be due to the oppressive times when those of the Invisible Generation had to develop their own communities of support. Conversely, through the cycle of socialization (Harro, 2013), women are socialized to be more relational than men. In addition, gay men are also socialized in structures of sexism that privilege men (regardless of sexual orientation) over women. This is another example of intersectionality as perceived through an Iridescent lens. This finding also may also reflect the reality that gay men disproportionally experienced the loss of friends, partners/spouses, and former partners/spouses during the height of the AIDS pandemic, which may also influence their spirituality. While many experienced post-traumatic growth, many also experienced insidious and on-going trauma (Szymanski & Balsam, 2011).

Health and Well-Being by Generation

The Invisible Generation had higher physical impairment than the Pride Generation. Yet on other health indicators, it was the Pride Generation that had higher rates of HIV/AIDS, depressive symptomatology, and lower quality of life. The increased physical impairment in the Invisible Generation may be due to the fact that as one ages, the incidence of chronic illness increases, and thus so does physical and functional impairment (Jaul & Barron, 2017). The Pride Generation, however, was more likely to have HIV/AIDS than the Silenced and Invisible generations; and the Silenced Generation was more so than the Invisible Generation. In 1981, when the Pride Generation was in late adolescence/early adulthood (ages 17–31); the Silenced Generation was transitioning from early to middle adulthood; while the Invisible Generation was arcing from midlife to older adulthood, many of whom were in their 50s and beyond (AVERT, 2015). Another potential factor that may be at play regarding lower quality of life could be an interaction effect of age and cohort. The U-shape of well-being—a globally validated and reliable construct across both developed and developing nations—indicates that beginning in late adolescence/early adulthood (roughly 18–24-year old) high levels of well-being among individuals begins to decrease (Blanchflower, 2021; Blanchflower & Oswald, 2008). The decline in well-being reaches its nadir at approximately 50 years of age, and then begins trending upward—a trend that becomes even steeper upward around the age of 64–65 and continues as such until approximately the age of 80, at which point well-being equals or exceeds what it was in late adolescence/early adulthood (Blanchflower, 2021; Blanchflower & Oswald, 2008).

The Pride Generation was more likely to report depressive symptomatology than the Silenced and Invisible generations. This is congruent with research in depression among adults in the general population; a 20-year review of the literature finds that the prevalence of major depression is greater among midlife adults than it is older and younger adults (Haigh et al., 2018). There may also be a generational effect, as the prevalence of depression appears to be increasing with each successive generation since those born during the Great Depression (Brault et al., 2012; Yang, 2007). We find a similar trend in overall quality of life, and three out of four subdomains of health-related quality of life (i.e., psychological, social, environmental), which was lower in the Pride Generation than the Silenced and Invisible generations.

Our findings, guided by the Iridescent principle of intersectionality, noted important interactions between gender and generational identities. This also speaks to the cycle of socialization (Harro, 2013), and the heterogeneity. Much of the extant research has focused on the lives and experiences of gay men, at the expense of lesbians. At the same time, recent extensions of the seemingly homogenous nature of sociological life course and developmental psychological lifespan theories have significantly improved our understandings of the spectrum of human experience (Dannefer & Daub, 2009).

Conclusion

These data are among the first to analyze health, kin, social and intrapersonal data across generations of lesbians and gay men and to do so using the Iridescent Life Course. Despite the unique nature of our findings, various limitations need to be acknowledged. First, the associations between generation and life events, such as physical impairment and quality of life, might be confounded with aging and mortality. Additionally, in this study respondents utilized a retrospective account of experiences across the life course so there may be bias or inaccuracies in the recall of various live events. To address these limitations, there are several important next steps to move the research forward including following the participants over time to better differentiate age, cohort, and period effect.

As we move forward, more attention to the intersectionality of demographic characteristics and the life course is needed. It will also be important to keep a focus on gender and racial/ethnic differences and how historical times may unfold differently for these groups. Also important is recognizing the reach LGBT people, communities, and cultures have had in reshaping and advancing society—for example, how models of care that LGBT people and allies, along with health professionals developed in the 1980s and 1990s for HIV/AIDS that have informed global responses to healthcare. LGBT voices have all too often been unrecognized and unsung forces in other efforts to shift dominant political and cultural structures, such as Black liberation (Babu, 2022), disability justice (Crosby & Jakobsen, 2020), and de-carceration (Hereth & Bouris, 2019).

We found that the Pride Generation has benefited by many of the positive societal changes, yet this generation continues to experience significant disparities in health, well-being, work related discrimination, and experiences of victimization compared to the older generations. It is notable given the current social landscape that LGBT rights are increasingly under fire. Moving forward it will be important that shifts in social attitudes and public policies are coupled with interventions to prevent the ongoing expression and enactment of bias. Changes have left many of those in the Pride Generation, and likely the younger generations as well, vulnerable to adverse experiences that continue to impact their lives.

Informed by the Iridescent Life Course, our study identified various components of this framework at play in this analysis. The importance of intersectionality was clearly identified through the interaction effects seen when examining gender and generational membership and the concept of fluidity and how elements of life change over the life course. Camouflage was identified as occurring as a protective mechanism among many of these older adults in order to protect themselves from discrimination. Over time, particularly prior to the Pride Generation, signaling was important to create safe communication between people. Moving forward we have the opportunity to apply this framework to younger generations of LGBT people. An emerging question is how the Iridescent Life Course will unfold as realities of intersectionality and queer identities take their place in the current context and among future generations.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging (R01AG026526).

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Adkins J.(2016). “These people are frightened to death”: Congressional investigations and the lavender scare. Prologue-Quarterly of the National Archives and Records Administration, 48(2), 6–20. https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2016/summer/lavender.html [Google Scholar]

- Andresen EM, Malmgren JA, Carter WB, & Patrick DL (1994). Screening for depression in well older adults: Evaluation of a short form of the CES-D (Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale). American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 10(2), 77–84. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8037935 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC, Ajrouch KJ, & Birditt KS (2013). The convoy model: Explaining social relations from a multidisciplinary perspective. The Gerontologist, Advanced Online Access, 54(1), 1–11. 10.1093/geront/gnt118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AVERT (2015). History of HIV&AIDS overview. Retrieved October 30 from http://www.avert.org/professionals/history-hiv-aids/overview

- Babu D.(2022). Perceptions of LGBTQ elders of color on the Black Lives Matter movement and policing. Journal of Black Sexuality and Relationships, 8(3), 69–91. 10.1353/bsr.2022.0003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchflower DG (2021). Is happiness u-shaped everywhere? Age and subjective well-being in 145 countries. Journal of Population Economics, 34(2), 575–624. 10.1007/s00148-020-00797-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchflower DG, & Oswald AJ (2008). Is well-being u-shaped over the life cycle? Social Science & Medicine, 66(8),1733–1749. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.01.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonomi AE, Patrick DL, Bushnell DM, & Martin M.(2000). Validation of the United States’ version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL) instrument. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 53(1), 1–12. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/10693897 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brault MC, Meuleman B, & Bracke P.(2012). Depressive symptoms in the belgian population: Disentangling age and cohort effects. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 47(6), 903–915. 10.1007/s00127-011-0398-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burda JM (2016). Public and private benefits (federal and state). Estate planning for same-sex couples (3rd ed., p. xxiv595). American Bar Association. [Google Scholar]

- Canaday M.(2009). The straight state: Sexuality and citizenship in twentieth-century America. Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Chae DH, Krieger N, Bennett GG, Lindsey JC, Stoddard AM, & Barbeau EM (2010). Implications of discrimination based on sexuality, gender, and race/ethnicity for psychological distress among working-class sexual minorities: The united for health study, 2003–2004. International Journal of Health Services, 40(4), 589–608. 10.2190/hs.40.4.b.http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21058533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corak M.(2013). Inequality from generation to generation: The United States in comparison. In Rycroft RS (Ed.), The economics of inequality, poverty, and discrimination in the 21st century (2: Solutions, pp. 107–126). ABC-CLO, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw KW (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. In Kelly Weisbert D.(Ed.), Feminist legal theory: Foundations (pp. 383–395). [Google Scholar]

- Crosby C, & Jakobsen JR (2020). Disability, debility, and caring queerly. Social Text, 38(4), 77–103. 10.1215/0164272-860454 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dannefer D, & Daub A.(2009). Extending the interrogation: Life span, life course, and the constitution of human aging. [Article]. Advances in Life Course Research, 14(1–2), 15–27. 10.1016/j.alcr.2009.05.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer E.(2006). Psychiatry and race during world war ii. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 61(2), 117–143. 10.1093/jhmas/jrj035, https://muse.jhu.edu/article/194885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foucault M.(1978). The history of sexuality (1st American ed., Vol. 1). Pantheon Books. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen Goldsen K, Jen S, Clark T, Kim H-J, Jung H, & Goldsen J.(2022). Historical and generational forces in the iridescent life course of bisexual women, men, and gender diverse older adults. Sexualities, 25(1–2), 132–156. 10.1177/1363460720947313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen Goldsen KI, Emlet CA, Fabbre VD, Kim H-J, Lerner JE, Jung H, Harner V, & Goldsen J.(In press). Historical and social forces in the Iridescent Life Course: Key life events and experiences of transgender older adults. Ageing & Society. In press. [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen Goldsen KI, Jen S, & Muraco A.(2019). Iridescent life course: Lgbtq aging research and blueprint for the future – a systematic review. Gerontology, 65(3), 253–274. 10.1159/000493559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, & Kim H-J (2017). The science of conducting research with lgbt older adults- an introduction to aging with pride: National health, aging, and sexuality/gender study (NHAS). The Gerontologist, 57(suppl_1), S1–S14. 10.1093/geront/gnw212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Kim H-J, Barkan SE, Muraco A, & Hoy-Ellis CP (2013). Health disparities among lesbian, gay male and bisexual older adults: Results from a population-based study. American Journal of Public Health, 103(10), 1802–1809. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Lindhorst T, Kemp SP, & Walters KL (2009). My ever dear”: Social work’s “lesbian” foremothers-a call for scholarship [Article]. Affilia-Journal of Women and Social Work, 24(3), 325–336. 10.1177/0886109909337707 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen-Goldsen KI, Simoni JM, Kim H-J, Lehavot K, Walters KL, Yang J, Hoy-Ellis CP, & Muraco A.(2014). The health equity promotion model: Reconceptualization of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health disparities. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 84(6), 653–683. 10.1037/ort0000030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- General Accounting Office, U. S (2004). Defense of marriage act: Update to prior report. https://www.gao.gov/new.items/d04353r.pdf

- Goffman E.(1963). Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Prentice-Hall, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon AR, & Meyer IH (2007). Gender nonconformity as a target of prejudice, discrimination, and violence against lgb individuals. J LGBT Health Res, 3(3), 55–71. 10.1080/15574090802093562. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19042905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BL, Maisiak R, Wang MQ, Britt MF, & Ebeling N.(1997). Participation in health education, health promotion, and health research by african americans: Effects of the tuskegee syphilis experiment. Journal of Health Education, 28(4), 196–201. 10.1080/10556699.1997.10603270 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haigh EAP, Bogucki OE, Sigmon ST, & Blazer DG (2018). Depression among older adults: A 20-year update on five common myths and misconceptions. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 26(1), 107–122. 10.1016/j.jagp.2017.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson MJ (2006). Moving forward together: The lgbt community and the family mediation field. Pepperdine Dispute Resolution Law Journal, 6(2), 295–312. [Google Scholar]

- Harro B.(2013). The cycle of socialization. In Adams M, Blumenfeld W, Castaneda C, Hackman HW, Peters ML, & Zuniga X.(Eds.), Readings for diversity and social justice (pp. 45–52). Routledge Press. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM (2009). Hate crimes and stigma-related experiences among sexual minority adults in the United States: Prevalence estimates from a national probability sample. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(1), 54–74. 10.1177/0886260508316477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Gillis JR, & Cogan JC (2009). Internalized stigma among sexual minority adults: Insights from a social psychological perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(1), 32–43. 10.1037/a0014672 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hereth J, & Bouris A.(2019). Queering smart decarceration: Centering the experiences of LGBTQ+ young people to imagine a world without prisons. Affilia, 35(3), 358–375. 10.1177/0886109919871268 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hoy-Ellis CP, Shiu C, Sullivan KM, Kim H-J, Sturges AM, & Fredriksen-Goldsen KI (2017). Prior military service, identity stigma, and mental health among transgender older adults. The Gerontologist, 57(suppl 1), S63–S71. 10.1093/geront/gnw173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaul E, & Barron J.(2017). Age-related diseases and clinical and public health implications for the 85 years old and over population. Frontiers in Public Health, 5, 1–7. 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson DK (2004). The lavender scare: The cold war persecution of gays and lesbians in the federal government. University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey AC, Pomeroy WB, & Martin CE (1948). Sexual behavior in the human male. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsey AC, Pomeroy WB, Martin CE, & Gebhard PH (1953). Sexual behavior in the human female. B. Saunders Co. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S.(2006). Propensity score adjustment as a weighting scheme for volunteer panel web surveys. Journal of Official Statistics, 22(2), 329–349. [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, & Valliant R.(2009). Estimation for volunteer panel web surveys using propensity score adjustment and calibration adjustment. Sociological Methods & Research, 37(3), 319–343. 10.1177/0049124108329643 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto D, & Hull P.(1994). Language and language acquisition. In Matsumoto D.(Ed.), People: Psychology from a cultural perspective (pp. 83–100). Brooks/Cole Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Mayeda ER, Tchetgen Tchetgen EJ, Power MC, Weuve J, Jacqmin-Gadda H, Marden JR, Vittinghoff E, Keiding N, & Glymour MM (2016). A simulation platform for quantifying survival bias: An application to research on determinants of cognitive decline. American Journal of Epidemiology, 184(5), 378–387. 10.1093/aje/kwv451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges Obergefell v., 576 U.S. (2015). https://www.supremecourt.gov/opinions/14pdf/14-556_3204.pdf

- Pew Research Center (2019). 10 Facts About Atheists. Pew Research Center, Retrieved September 1, 2022 from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/12/06/10-facts-about-atheists/ [Google Scholar]