Abstract

Compared with conventional coagulation tests and factor-specific assays, viscoelastic hemostatic assays (VHAs) can provide a more thorough evaluation of clot formation and lysis but have several limitations including clot deformation. In this proof-of-concept study, we test a noncontact technique, termed resonant acoustic rheometry (RAR), for measuring the kinetics of human plasma coagulation. Specifically, RAR utilizes a dual-mode ultrasound technique to induce and detect surface oscillation of blood samples without direct physical contact and measures the resonant frequency of the surface oscillation over time, which is reflective of the viscoelasticity of the sample. Analysis of RAR results of normal plasma allowed defining a set of parameters for quantifying coagulation. RAR detected a flat-line tracing of resonant frequency in hemophilia A plasma that was corrected with the addition of tissue factor. Our RAR results captured the kinetics of plasma coagulation and the newly defined RAR parameters correlated with increasing tissue factor concentration in both healthy and hemophilia A plasma. These findings demonstrate the feasibility of RAR as a novel approach for VHA, providing the foundation for future studies to compare RAR parameters to conventional coagulation tests, factor-specific assays, and VHA parameters.

Keywords: hemophilia A, hemostatic, point of care, thromboelastography, ultrasonic

Patients with hemophilia A pose challenging perioperative management because of the increased risk of prolonged hemorrhage. Conventional coagulation tests (CCTs) and factor-specific assays have traditionally been used to assess hemostatic competence in patients with hemophilia A. However, the clinical manifestations of hemophilia A depend not only on the concentration of coagulation factors but also on how this coagulation cascade ultimately interacts with platelets to form the final thrombus. CCTs and factor-specific assays, including factor VIII (FVIII) to protein C ratio, yield results that may vary significantly in their association with clinical severity of hemophilia A.1-3 Moreover, many hospitals do not offer factor-specific assays, ultimately delaying accurate bedside diagnosis and therapy for hemophilia A.1 To enhance selection of personalized therapies for this patient population, an improved precision-based method to rapidly characterize the heterogeneous phenotypes is urgently needed.1-3

Whole blood viscoelastic hemostatic assays (VHAs)2,4-16 have been increasingly used to guide administration of therapies for this patient population. Compared with CCTs, VHA techniques (e.g., thromboelastography [TEG], rotational thromboelastometry [ROTEM], Sonoclot, Quantra, and Clot-Pro) have shown superior sensitivity and specificity in evaluating many coagulopathies, owing to their ability to assess the entire lifespan of clot formation and lysis.17-23 These techniques have demonstrated effective management of hemophilia A by establishing clinical phenotype, perioperative diagnosis and therapy, and personalized titration of anticoagulant agents.1,24

A criticism of clinically available VHA methodologies is that these techniques considerably deform the clot sample, which may yield inconsistent results. These techniques typically use either a rotating cup and pin system (e.g., TEG 5000, ROTEM delta, and ROTEM sigma), a vertical cup and pin system (e.g., Sonoclot), or vibration detection by light-emitting diode (e.g., TEG 6s).23 New and emerging technologies of point-of-care (POC) hemostatic assays have used iterations of ultrasonic techniques for noncontact testing.22 For example, sonic estimation of elasticity via resonance (SEER), or sonorheometry, utilizes ultrasound technology to deform samples without direct physical contact. Quantra (HemoSonics, LLC) is a fully automated ultrasound-based test that also uses dry reagents to simplify quality assurance and improve reproducibility.22,25 However, these VHAs, including Quantra, require expensive systems and reagents that may not be readily available at every institution that could benefit from these devices.

In this study, we tested the feasibility of a novel, noncontact VHA technique termed resonant acoustic rheometry (RAR) for characterization of human plasma coagulation. RAR is an ultrasound-based technique that we have recently developed.26 However, it is distinctively different from other ultrasound-based techniques such as SEER or Quantra in terms of instrumentation and underlying measurement principle. RAR uses synchronized ultrasound pulses to generate and detect the microscale, resonant surface oscillation of a sample housed in a well of a 96-well microplate (►Fig. 1). The frequency of the measured resonant modes of surface wave is utilized to determine the viscoelastic properties of the material.26

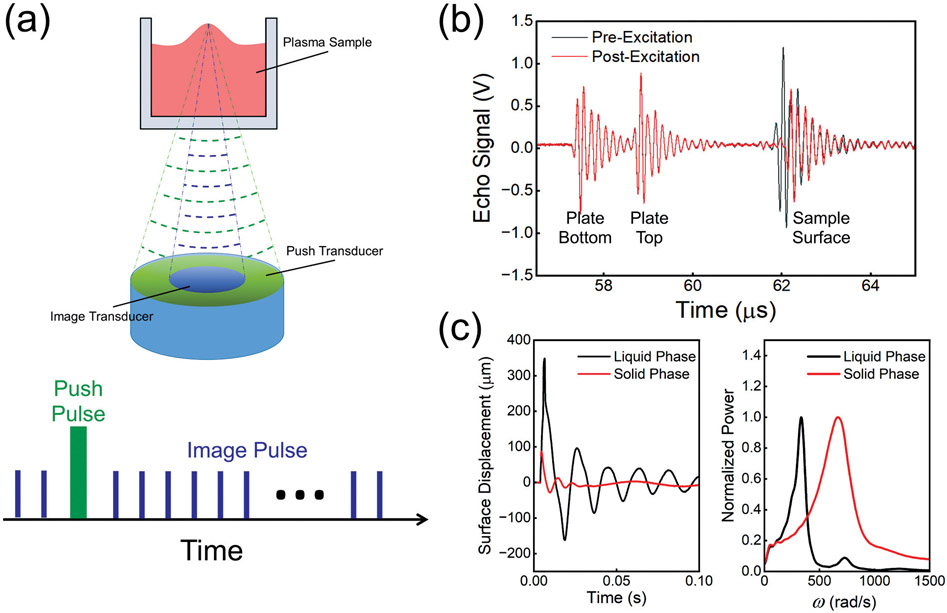

Fig. 1.

(a) Schematic diagram of the RAR system with two co-linear focused ultrasound transducers aligned beneath a 96-well tissue culture plate (top). Schematic of pulse signals for detection (imaging) and excitation of sample surface movements (bottom). (b) Echo signal of pre-excitation and post-excitation. (c) Surface displacement of plasma sample as a function of time in the liquid phase and solid phase (left), and normalized power spectra of surface displacement of plasma in the liquid phase and solid phase (right) showing the peak angular frequencies of the surface displacement. RAR, resonant acoustic rheometry; ω, angular frequency.

We have demonstrated the use of RAR for rapid quantification of the viscoelastic properties of soft biomaterials and validated our measurements by rotational shear rheometry,26 especially for characterizing the dynamic changes of temporally evolving biomaterials including various hydrogels during gelation noninvasively. In particular, we have used RAR for characterization of the dynamic process of thrombin-induced fibrin gelation at different fibrin concentrations by measuring the viscoelasticity of the samples.26 Due to its unique advantages, RAR may have the potential to provide a novel and advantageous clinical VHA that overcomes some of the limitations of current VHA approaches. Thus, in this proof-of-concept study, our goal is to test whether RAR can detect the differences in human plasma coagulation, particularly whether RAR can capture the different kinetics of the coagulation between normal and hemophilia A plasma.

RAR circumvents many of the aforementioned limitations of clinically available VHA devices for characterization of material viscoelastic property. Since RAR uses low-intensity ultrasound pulses for both excitation and interrogation of samples, the techniques allow for noncontact measurements, avoids contamination, and minimizes deformation of the test samples. In addition, RAR requires only small volumes and is not dependent on a scattering or absorbing medium within the blood sample, an advantage over other ultrasound techniques. It achieves rapid measurements using conventional labware in a cost-efficient fashion and can be readily implemented for high-throughput batch analysis. These efficiencies make the RAR methodology a promising approach for providing nondestructive, longitudinal tracking of small-volume biological samples in a short period of time with great reproducibility, sensitivity, and accuracy. Therefore, the goal of this proof-of-concept study is to obtain preliminary data and define clinically useful parameters using RAR for characterizing the kinetics of the coagulation process of normal and hemophilia A plasma samples.

Materials and Methods

Sample Surface Deformation and Detection Using Ultrasound Pulses

An ultrasound transducer assembly consisting of two co-linearly aligned focused ultrasound transducers was employed for excitation and detection of the dynamic surface displacement of the sample. As shown in ►Fig. 1, the aligned transducers were placed in a temperature-controlled water tank and directed upward at the center of the surface of a sample in a 96-well plate (►Fig. 1a). Only the bottom of the 96-well plate was submerged below the water surface for acoustic coupling while maintaining a sterile environment for the samples. The transducer assembly was controlled by a three-dimensional motion platform (Velmex) for initial alignment and multiple well testing. Driven by a power amplifier (75A250; Amplifier Research) and a waveform generator (33220A; Agilent), the outer annular transducer (center frequency 1.5 MHz) worked as the excitation transducer to generate displacement at the sample surface. The inner circular transducer (center frequency 7 MHz), driven by a pulser/receiver (5900PR; Olympus), was used to send an ultrasound pulse and detect the backscattered radio-frequency (RF) signals. The transducers were synchronized using a pulse generator (Model 565; BNC) for excitation and tracking of the surface movement.

The bottom panel of ►Fig. 1a shows the schematic of ultrasound pulses for excitation and detection during one RAR application, where the excitation transducer sends a 33 μs excitation pulse to induce an initial displacement of the sample surface, inducing the formation of resonant surface waves and resonant surface oscillation. The inner detection transducer, operated in pulse-echo mode, was used to detect the reflected signals which were digitized using an oscilloscope (54830B; Agilent) for offline analysis. To measure the sample surface displacement from the received postexcitation signals from the sample surface, a cross-correlation algorithm with a ten-wavelength window was developed to determine the temporal shift of the backscattered signal by comparing the postexcitation signals with the pre-excitation signal from the sample surface (the third peak; sample surface). The plate bottom and plate top were stationary during detection; therefore, the relative shift of sample surface location indicated the displacement of the surface from the equilibrium. A custom MATLAB script (MathWorks 2021b) was used to control all instruments in the measurements for efficient automated testing.

During one RAR measurement, one excitation ultrasound pulse was applied to induce deformation of the sample surface, generating a resonant surface wave or oscillation, and a series of pulse-echo interrogations (pulse repetition frequency 5,000 Hz) was followed to detect the dynamic, resonant surface oscillation in real time. ►Fig. 1b shows the received backscattered RF signals from the plate bottom, plate top, and sample surface.

To track the change of a sample over time, such as blood plasma during coagulation, RAR was applied repeatedly at regular intervals (e.g., every 2 seconds) to track the changes in the resonant surface displacement. The left panel of ►Fig. 1c shows the time evolution of the resonant surface displacement of a normal plasma sample in the liquid phase and solid phase, and the right panel shows the spectrum of the angular frequency of the resonant surface displacement which depends on the surface tension and the bulk viscoelastic property of the sample.

Blood Plasma Sample Preparation for RAR

Informed consent was waived for this study since no patient identifiers were included. Before RAR experiments, citrated frozen, platelet-poor, pooled human plasma samples of healthy subjects and plasma from one hemophilia A subject (from George King Biomedical, Overland Park, KS) were brought to room temperature for 10 minutes to be thawed and then heated to 37°C before measurement. Kaolin stock (Haemonetics), 0.2 M CaCl2 (Fluka), tissue factor (TF) stock (10X Dade Innovin, Siemens), and 0.85% buffered saline were preheated to 37°C. To demonstrate the feasibility of RAR in monitoring the changes of the plasma samples over time, 90 μL of human plasma samples was combined with 5 μL of 0.2 M CaCl2 and 5 μL saline-diluted kaolin stock or TF for a final concentration of 0.01 M CaCl2 and 4% kaolin stock or TF at a final ratio of 0.01, 0.05, and 0.2%, respectively. After mixing, the total volume of 100 μL of the activated sample was immediately pipetted into one well in a 96-well microplate. A custom MATLAB script was used to control the RAR system for automatic testing of the plasma sample starting at 1 minute after mixing and for a total tracking period of 60 minutes. A human plasma sample with 4% kaolin, 0.01 M CaCl2, and saline was tested as a control group. Three independent experimental runs were performed for each condition.

Data Analysis

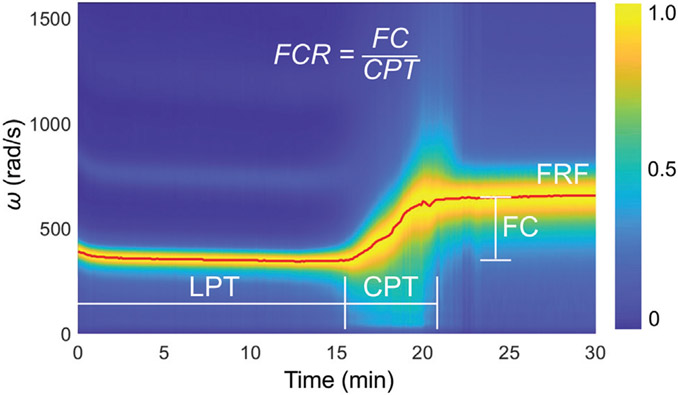

Heat maps of the resonant surface displacement were generated as two-dimensional (2D) color-coded images combining the temporal displacement profiles (vertical axis) measured at a series of time points (horizontal axis). Fast Fourier transform was performed on each measured temporal displacement to obtain the angular frequency spectrum of the resonant surface displacement. A normalized spectrogram, divided by the maximum signal amplitude, was generated for each sample, depicting a 2D color-coded image of the spectrum on the vertical axis versus coagulation time on the horizontal axis. ►Fig. 2 shows a normalized spectrogram (heat map of power spectrum vs. time) of the coagulation process of a normal human plasma sample triggered by addition of 4% kaolin measured using RAR. From the spectrograms, the liquid phase time (LPT) was defined as the time when the sample’s angular frequency reached 450 rad/s, which was the average angular frequency for the liquid phase measured in our RAR experiments using 96-well microplates. This value reflects the resonant frequency of liquid samples with a surface tension of 70 dyn/cm.26 The clotting phase time (CPT) was defined as the time interval of increasing angular frequency from the end of LPT to the new stable angular frequency of the solid phase. The frequency change (FC) was defined as the difference in frequency between the solid phase and the liquid phase. The frequency change rate (FCR) was defined as FC/CPT. The final resonant frequency (FRF) is the final angular frequency measured at the end of the 60-minute run (►Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Spectrogram of normal human plasma coagulation triggered by 4% kaolin measured using RAR and definition of clotting parameters. The resonant angular frequency of the surface oscillation stayed constant initially when the sample was in the liquid phase before a distinct increase was detected at t = 15 minutes, indicating a phase change occurring in the sample as it began to transition from the liquid to a state with higher elasticity. The resonant frequency continued to increase rapidly until t = 22 minutes before leveling off, indicating the coagulation process in the sample that changed from the liquid phase to a solid phase. Liquid phase time (LPT) refers to the amount of time duration of the liquid phase before the rapid rise in resonant frequency. Clotting phase time (CPT) refers to the period of time when the rapid rise of frequency occurred. Frequency change rate (FCR), or the slope of the frequency during the rapid clotting phase, is defined as the frequency change (FC) divided by CPT. Final resonant frequency (FRF) refers to the resonant angular frequency measured at the end of the run. CPT, clotting phase time; FC, frequency change; FCR, frequency change rate; FRF, final resonant frequency; LPT, liquid phase time; RAR, resonant acoustic rheometry.

As described previously,26 the dynamic resonant surface displacement was modeled as a standard damped harmonic oscillator. The viscosity (η) of the sample was determined from the damping coefficient (Γ) of the resonant surface displacement measured at the end of the RAR 60-minute run. The viscosity was calculated using η = Γρ/(2k2) and η = Γρ/(0.45k2) for the liquid phase and clotting phase, respectively, where k is the wavenumber of the resonant mode of surface wave in the sample and ρ is the material density.26

GraphPad Prism 9 was used for statistical analysis. Unpaired Student’s t-test was performed to determine statistically significant differences between measurements of the normal and hemophilia A plasma samples.

Results

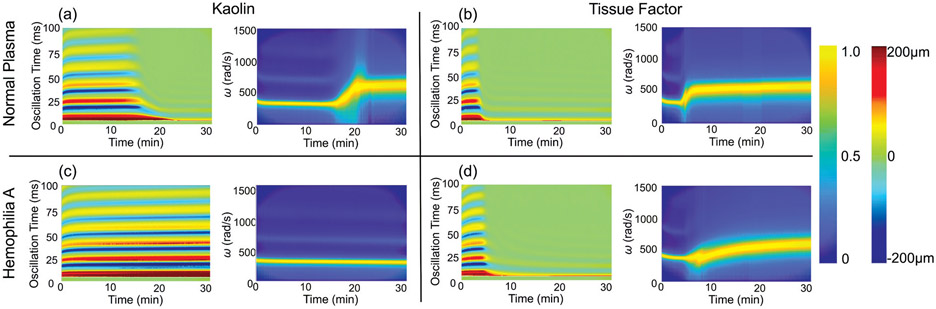

►Fig. 3 shows normalized spectrograms and heat maps of the surface displacement versus time measured from a normal plasma sample (►Fig. 3a, b) and a hemophilia A plasma sample (►Fig. 3c, d) with the addition of 0.01 M CaCl2 + 4% kaolin + saline or 0.01 M CaCl2 + TF, respectively. In general, for normal plasma, the heat map of surface oscillation (►Fig. 3a) shows a dramatic decrease in amplitude around LPT = 15 minutes and 5 minutes with the addition of kaolin and TF respectively, corresponding to the phase change of the samples from the liquid phase to the solid phase. Since the acoustic intensity of the excitation ultrasound pulse remained the same throughout all of the RAR measurements, the significant and rapid decreases in amplitude of surface oscillation indicate that the samples rapidly became stiffer around these time points. The spectrograms show that the resonant frequency of the surface oscillation, which corresponds to the mechanical properties of the sample as described previously,26 exhibited a dynamic progression with a rapid increase from a constant value before leveling off, demonstrating the transition of the sample through the liquid phase, clotting phase, and solid phase as described in ►Fig. 2. These results show that under the conditions used in our experiments the coagulation of normal plasma triggered by TF occurred faster than that triggered by kaolin. Taken together, our results show that RAR can detect the kinetics of blood plasma coagulation from both the temporal and spectral domain signals. While the temporal signals offer a direct detection of changes in the sample, the spectral characteristics were utilized to quantify the viscoelastic properties of the sample using hydrodynamic models.26 In comparison, minimal changes in the surface oscillation and angular frequency were detected in hemophilia A plasma samples with the addition of kaolin (►Fig. 3c), indicating no coagulation in the samples. However, when TF was added, characteristic increases in surface oscillation and angular frequency corresponding to coagulation were observed (►Fig. 3d), indicating clot formation in the samples. Interestingly, at the same concentration of TF, our RAR measurements show that coagulation of normal plasma samples occurred faster (shorter LPT) than that of the hemophilia A plasma samples, indicating important differences between the normal plasma and hemophilia A plasma.

Fig. 3.

(a) Example of the surface displacement heat map (left) and spectrogram (right) for normal plasma samples with the addition of kaolin (4%). The horizontal axis in these images represents the elapsed time of coagulation process during which RAR measurements were performed. The vertical axis in the displacement heat map indicates the oscillation time of the surface oscillation in one single RAR measurement. The vertical axis in the spectrogram is the angular frequency (ω) of the surface displacement. The color represents the normalized power of angular frequency and displacement amplitude, respectively. The peak angular frequency shows the resonant frequency of the surface oscillation, i.e., the frequency of the resonant mode of the surface waves in the sample. (b) Example of the surface displacement heat map (left) and spectrogram (right) for normal plasma samples with the addition of tissue factor. (c, d) Displacement heat map (left) and spectrogram (right) of hemophilia A plasma samples with addition of kaolin (c) and tissue factor (d). Tissue factor concentrations for these examples were at 0.05%. The peak angular frequency shows the resonant frequency of the surface oscillation, i.e., the frequency of the resonant mode of the surface waves in the sample. To the right of the figure, the legend bar ranging from blue (0) to yellow (1.0) indicates the measured ω of the sample during a given time point in the run for the spectrograms. The legend bar ranging from dark blue (−200 μm) to dark red (200 μm) represents the surface displacement in the heat maps. RAR, resonant acoustic rheometry; ω, angular frequency.

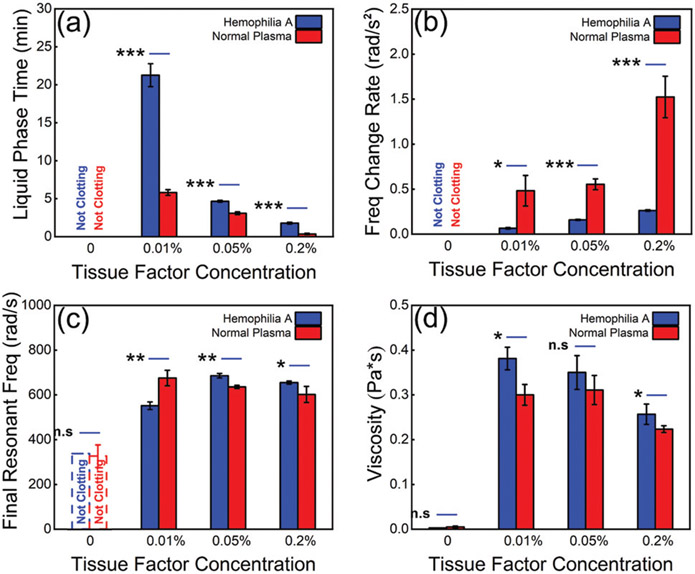

To obtain quantitative comparisons, we extracted the coagulation parameters from RAR measurements of plasma samples with TF, specifically from the angular frequency spectrograms of normal plasma and hemophilia A plasma samples respectively as described in ►Fig. 2. As demonstrated by the results in ►Fig. 4, the LPT decreased significantly with increasing concentration of TF for both normal plasma and hemophilia A plasma (►Fig. 4a). Interestingly, RAR results show that the hemophilia plasma did not clot without TF (►Fig. 4a); with the addition of TF, hemophilia A plasma did undergo clotting, albeit at a much slower rate than normal plasma with the addition of TF at concentration (►Fig. 4a). The FCRs for both normal and hemophilia A plasma samples increased with increasing concentrations of TF (►Fig. 4b), indicating that addition of TF induced a faster coagulation. It is noted that the normal plasma samples exhibited statistically significantly faster rates of FC compared with hemophilia A plasma samples (►Fig. 4b), suggesting a more sensitive coagulation process of normal plasma compared with hemophilia A plasma.

Fig. 4.

(a) Liquid phase time for normal plasma and hemophilia A plasma without and with the addition of tissue factor at 0.01, 0.05, and 0.2%. (b) Frequency change rate of normal plasma and hemophilia A plasma without and with tissue factor at 0.01, 0.05, and 0.2%. (c) Final resonant frequency measured in normal and hemophilia A plasma without and with 0.01, 0.05, and 0.2% tissue factor. (d) Viscosity measured in normal and hemophilia A plasma without and with 0.01, 0.05, and 0.2% tissue factor. Unpaired t-test p-values: * < 0.05, ** < 0.01, *** < 0.001, and n.s, not significant.

The FRFs measured in the samples with the addition of TF show a notable increase compared with those measured in samples in the liquid phase (►Fig. 4c), indicating the increase in elasticity or stiffness of the solid phase compared with the liquid phase. In addition, by detecting the dynamic surface oscillation of the sample, RAR enabled the determination of viscosity, directly reflecting the viscoelastic properties in the dynamic coagulation process (►Fig. 4d). Our RAR results show that viscosity increased as the plasma samples transitioned from liquid to solid gel due to coagulation.27

Comparison of the normal and hemophilia A plasma coagulation triggered by kaolin is shown in ►Table 1. Without kaolin, no coagulation was observed in both normal and hemophilia A plasma, as expected in the citrated samples. The FRFs and viscosities measured in the samples were those from the liquid-state plasma samples in these cases. With the addition of kaolin, normal plasma exhibited coagulation, but hemophilia A plasma was not observed to clot during the 60-minute run.

Table 1.

RAR measurements of normal and hemophilia A plasma with 4% kaolin and 0.01 M CaCl2

| LPT (min) | FCR (rad/s2) | FRF (rad/s) | η (pa • s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kaolin | Normal plasma | 12.63 ± 2.15 | 0.83 ± 0.24 | 704.54 ± 15.29 | 0.27 ± 0.02 |

| Hemophilia A plasmaa | N/A | N/A | 340.28 ± 0.08 | 0.0029 ± 0.00002 | |

| No kaolin | Normal plasmaa | N/A | N/A | 328.59 ± 50.48 | 0.0059 ± 0.002 |

| Hemophilia A plasmaa | N/A | N/A | 338.29 ± 0.07 | 0.0029 ± 0.00003 | |

Abbreviations: FCR, frequency change rate; FRF, final resonant frequency; LPT, liquid phase time; RAR, resonant acoustic rheometry; η, viscosity.

Did not clot during run.

Discussion

The frequency of resonant surface oscillation measured using RAR allowed defining a set of parameters to characterize clotting, including LPT, CPT, FC, FCR, and FRF. Our results show that the addition of TF to normal plasma significantly shortens the LPT, increases the FCR, and decreases the FRF. It may be extrapolated that hypercoagulable patients will demonstrate similar trends. In patients with hemophilia A, RAR demonstrates a constant angular frequency with no transition from the liquid phase to the clotting and solid phases. Addition of TF to hemophilia A plasma produces an RAR curve with similar characteristics to those seen in normal plasma with intact transition to the clotting and solid phases.

These RAR parameters describe the dynamics of clot formation similarly to clinically available VHAs, suggesting that RAR may provide parameters for evaluating blood coagulation. To illustrate the comparison of the RAR parameter with the parameters typically obtained using TEG, ►Table 2 shows that the RAR technique outputs a similar profile of coagulation. While the table does not indicate a direct comparison of specific results between these two techniques, the illustrative comparison reveals that the LPT from RAR, which reflects time to thrombin initiation of clot formation, is analogous to the reaction time (R) on TEG. Similarly, CPT in RAR reflects clot formation and kinetics, and the time to solid-phase transition measured by CPT is analogous to the clot formation/kinetics (K) on TEG. FCR from RAR also reflects clot kinetics and is analogous to the α-angle on TEG. FC and FRF indicate the maximum clot strength and are analogous to the maximum amplitude (MA) on TEG; however, it is important to note that TEG MA on whole blood measures the maximal platelet–fibrin interaction, whereas the RAR for this study was only performed on plasma, and thus, the FC and FRF correlate to the maximal strength of only the fibrin meshwork.

Table 2.

Comparison of TEG and RAR parameters; arrows reflect the expected change in hemophilia A plasma relative to a healthy plasma baseline in samples activated by kaolin and CaCl224

| Coagulation event | TEG | RAR |

|---|---|---|

| Clot initiation | ↑ R | ↑ LPT |

| Clot formation and clot kinetics | ↑ k | ↑ CPT |

| Clot formation and clot kinetics | ↓ α | ↓ FCR |

| Maximal clot strength (plasma) | N/A | ↓ FRF, ↓ FC |

| Maximal clot strength (whole blood) | ↓ MA | N/A |

| Viscosity (plasma) | N/A | ↓ η |

Abbreviations: CPT, clotting phase time; FC, frequency change; FCR, frequency change rate; FRF, final resonant frequency; k, clot formation/kinetics; LPT, liquid phase time; MA, maximum amplitude; R, reaction time; RAR, resonant acoustic rheometry; TEG, thromboelas-tography; η, viscosity.

In general, the temporal evolution of the resonant surface oscillation not only de marks the LPT when a drastic decrease in the amplitude of the resonant oscillation occurs, but also reveals that dampening of the surface oscillation increases rapidly as coagulation occurs. Additionally, the maximum displacement, measured at the beginning of the surface oscillation induced by the excitation ultrasound pulse, which represents the amplitude of surface oscillation, also decreased significantly as the result of phase change of the sample from the liquid to the solid phase. The aforementioned suggests that the maximum displacement may be a potential parameter to define plasma-based coagulation factor activity because the amplitude for the ultrasound excitation pulse was the same throughout the RAR measurement of the coagulation process. This study also analyzed the correlation between TF levels and LPT, FCR, FRF, and viscosity. These data may also be applied for quantification of TF concentrations in plasma. This methodology may be expanded to evaluate other coagulation factors such as FVIII and the effect of therapeutic adjuncts on RAR parameters.

Besides the addition of coagulation agents, the RAR technique is completely noncontact with minimal handling procedures to avoid contamination, requires a small amount of sample (~200 μL), and is versatile in terms of the observation temporal resolution (a few seconds). For now, RAR uses standard labware (microplates), but it can be readily adopted to use custom-designed sample containers for the purpose of saving costs.

Limitations

There are several limitations in this study. With the goal to test the feasibility of RAR to detect the coagulation kinetics and differences in human plasma, this study only tested whether RAR can detect the different kinetics of coagulation when comparing the plasma samples from a confirmed hemophilia A patient and pooled normal plasma. Our results demonstrate that RAR was indeed capable of detecting the differences between these two types of plasmas, as well as the differences among the samples under different conditions including with addition of different concentrations of TF and kaolin. However, detailed information regarding the FVIII level and other clinical information correlating RAR with the severity of hemophilia A could not be inferred from our results due to the limited scope. In essence, the limitation of the current study is that it is primarily focused on technology/engineering testing, and the human plasma samples were selected to simply represent different experimental groups with different coagulation profiles without providing detailed clinical information on why these samples exhibited different coagulation dynamics. To conduct a such study with high clinical information, a large-scale study involving many patients is needed.

In addition, a relatively low concentration, i.e., 0.01 M CaCl2, was added to the plasma samples to lower the free ionized calcium concentration to avoid citrate saturation and subsequent fast coagulation of plasma during measurement. However, the CaCl2 concentration used may not achieve physiological conditions. Future studies are needed to test samples from a larger number of patients and refine some of the relevant parameters to obtain quantitative parameters to allow a more rigorous comparison to CCTs and standard VHA results in patient populations with inherited and acquired coagulopathies. While the frequency of the resonant modes of surface wave is dependent on the geometry of the microplate containing the sample, the relationship of the resonant frequency to the sample radius has been established for a given mode of resonant surface oscillation. Nevertheless, it may be necessary for institutions to define their own reference ranges based on available equipment. Additionally, the current tests were performed using a prototype RAR system, and implementation of a more user-friendly RAR system will be needed for larger scale tests.

A future study is underway to correlate RAR parameters to CCTs and TEG parameters against patient populations with acquired coagulopathies. Specifically, the next study will compare the ability of RAR to quantify fibrinogen levels versus Clauss fibrinogen pathologic plasma samples. In contrast to the untimely Clauss fibrinogen measurement, RAR has significant POC potential to rapidly diagnose hypofibrinogenemia and guide repletion in hemorrhagic patients. Early fibrinogen depletion has been correlated to trauma-induced coagulopathy, and in tandem, early empiric fibrinogen repletion in trauma has been demonstrated to improve mortality.28-35 Thus, RAR has the potential to reduce blood product waste by personalized selection of those patients who require early fibrinogen repletion with cryoprecipitate or fibrinogen concentrates. Furthermore, this study tested RAR only using human plasma, although RAR should be readily applicable for testing whole blood coagulation in principle. While RAR is expected to be able to measure the changes of any temporally evolving materials as it quantifies the viscoelasticity of the material, future studies will be needed to identify any technical issues and to scrutinize RAR’s accuracy on whole blood samples and for detection of clinically significant fibrinolysis.

Conclusions

This proof-of-concept article describes the ability of RAR to quantify the differences between the coagulation kinetics of normal and hemophilia A plasma initiated by kaolin and TF. RAR curves of resonant frequency of surface oscillation not only show clear changes of the onset and rate of change during coagulation, but also demonstrate the influences by the coagulation agents and their concentration. Increasing concentration of TF corresponds to a decrease in LPT and increase in FCR. RAR measurements detected significant differences between normal plasma and hemophilia A plasma, and revealed a flat line representing the extreme hypocoagulable state of severe hemophilia A. These results demonstrate that RAR may have the potential to detect levels of TF in hemophilia A patients and other abnormalities in blood coagulation.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (R01-DE026630, to C.X.D. and J.P.S.).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

M.M.W. has received honoraria from Alexion Pharmaceuticals.

References

- 1.Ramiz S, Hartmann J, Young G, Escobar MA, Chitlur M. Clinical utility of viscoelastic testing (TEG and ROTEM analyzers) in the management of old and new therapies for hemophilia. Am J Hematol 2019;94(02):249–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sørensen B, Ingerslev J. Whole blood clot formation phenotypes in hemophilia A and rare coagulation disorders. Patterns of response to recombinant factor VIIa.J Thromb Haemost 2004;2(01):102–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bolton-Maggs PH. The rare inherited coagulation disorders. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2013;60(Suppl 1):S37–S40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aghighi S, Riddell A, Lee CA, Brown SA, Tuddenham E, Chowdary P. Global coagulation assays in hemophilia A: a comparison to conventional assays. Res Pract Thromb Haemost 2019;4(02):298–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nogami K. The utility of thromboelastography in inherited and acquired bleeding disorders. Br J Haematol 2016;174(04):503–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yada K, Nogami K, Wakabayashi H, Fay PJ, Shima M. The mild phenotype in severe hemophilia A with Arg1781His mutation is associated with enhanced binding affinity of factor VIII for factor X. Thromb Haemost 2013;109(06):1007–1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunkley SM, Yang K. The use of combination FEIBA and rFVIIa bypassing therapy, with TEG profiling, in uncontrollable bleeding associated with acquired haemophilia A. Haemophilia 2009;15(03):828–830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Young G, Blain R, Nakagawa P, Nugent DJ. Individualization of bypassing agent treatment for haemophilic patients with inhibitors utilizing thromboelastography. Haemophilia 2006;12(06):598–604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shima M, Matsumoto T, Ogiwara K. New assays for monitoring haemophilia treatment. Haemophilia 2008;14(Suppl 3):83–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fisher C, Mo A, Warrillow S, Smith C, Jones D. Utility of thromboelastography in managing acquired Factor VIII inhibitor associated massive haemorrhage. Anaesth Intensive Care 2013;41(06):799–803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qi X, Zhao Y, Li K, Fan L, Hua B. Evaluating and monitoring the efficacy of recombinant activated factor VIIa in patients with haemophilia and inhibitors. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 2014;25(07):754–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schneiderman J, Rubin E, Nugent DJ, Young G. Sequential therapy with activated prothrombin complex concentrates and recombinant FVIIa in patients with severe haemophilia and inhibitors: update of our previous experience. Haemophilia 2007;13(03):244–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Furukawa S, Nogami K, Ogiwara K, Yada K, Minami H, Shima M. Systematic monitoring of hemostatic management in hemophilia A patients with inhibitor in the perioperative period using rotational thromboelastometry. J Thromb Haemost 2015;13(07):1279–1284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pivalizza EG, Escobar MA. Thrombelastography-guided factor VIIa therapy in a surgical patient with severe hemophilia and factor VIII inhibitor. Anesth Analg 2008;107(02):398–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Misgav M, Mandelbaum T, Kassif Y, Berkenstadt H, Tamarin I, Kenet G. Thromboelastography during coronary artery bypass grafting surgery of severe hemophilia A patient - the effect of heparin and protamine on factor VIII activity. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 2017;28(04):329–333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fogarty PF, Mancuso ME, Kasthuri R, et al. ; Global Emerging Hemophilia Panel (GEHEP) Presentation and management of acute coronary syndromes among adult persons with haemophilia: results of an international, retrospective, 10-year survey. Haemophilia 2015;21(05):589–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Moore EE, Moore HB, Kornblith LZ, et al. Trauma-induced coagulopathy. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2021;7(01):30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Görlinger K, Pérez-Ferrer A, Dirkmann D, et al. The role of evidence-based algorithms for rotational thromboelastometry-guided bleeding management. Korean J Anesthesiol 2019;72(04):297–322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hartmann J, Walsh M, Grisoli A, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of trauma-induced coagulopathy by viscoelastography. Semin Thromb Hemost 2020;46(02):134–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Görlinger K, Dirkmann D, Hanke AA. Rotational thromboelastometry (ROTEM®). In: Moore HB, Moore EE, Neal MD, eds. Trauma Induced Coagulopathy. 2nd ed. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021:279–312 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walsh M, Thomas S, Kwaan H, et al. Modern methods for monitoring hemorrhagic resuscitation in the United States: why the delay? J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2020;89(06):1018–1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hartmann J, Murphy M, Dias JD. Viscoelastic hemostatic assays: moving from the laboratory to the site of care-a review of established and emerging technologies. Diagnostics (Basel) 2020;10(02):E118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volod O, Bunch CM, Zackariya N, et al. Viscoelastic hemostatic assays: a primer on legacy and new generation devices. J Clin Med 2022;11(03):860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Speybroeck J, Marsee M, Shariff F, et al. Viscoelastic testing in benign hematologic disorders: clinical perspectives and future implications of point-of-care testing to assess hemostatic competence. Transfusion 2020;60(Suppl 6):S101–S121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allen TW, Winegar D, Viola F. The Quantra® system and SEER sonorheometry. In: Moore HB, Neal MD, Moore EE, eds. Trauma Induced Coagulopathy. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021:693–704 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hobson EC, Li W, Juliar BA, Putnam AJ, Stegemann JP, Deng CX. Resonant acoustic rheometry for non-contact characterization of viscoelastic biomaterials. Biomaterials 2021;269:120676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ranucci M, Laddomada T, Ranucci M, Baryshnikova E. Blood viscosity during coagulation at different shear rates. Physiol Rep 2014;2(07):e12065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walsh M, Moore EE, Moore HB, et al. Whole Blood, fixed ratio, or goal-directed blood component therapy for the initial resuscitation of severely hemorrhaging trauma patients: a narrative review. J Clin Med 2021;10(02):320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mengoli C, Franchini M, Marano G, et al. The use of fibrinogen concentrate for the management of trauma-related bleeding: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Blood Transfus 2017;15 (04):318–324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ziegler B, Bachler M, Haberfellner H, et al. ; FIinTIC study group. Efficacy of prehospital administration of fibrinogen concentrate in trauma patients bleeding or presumed to bleed (FIinTIC): a multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomised pilot study. Eur J Anaesthesiol 2021;38(04):348–357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Curry N, Foley C, Wong H, et al. Early fibrinogen concentrate therapy for major haemorrhage in trauma (E-FIT 1): results from a UK multi-centre, randomised, double blind, placebo-controlled pilot trial. Crit Care 2018;22(01):164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nascimento B, Callum J, Tien H, et al. Fibrinogen in the initial resuscitation of severe trauma (FiiRST): a randomized feasibility trial. Br J Anaesth 2016;117(06):775–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamamoto K, Yamaguchi A, Sawano M, et al. Pre-emptive administration of fibrinogen concentrate contributes to improved prognosis in patients with severe trauma. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open 2016;1(01):e000037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Innerhofer P, Fries D, Mittermayr M, et al. Reversal of trauma-induced coagulopathy using first-line coagulation factor concentrates or fresh frozen plasma (RETIC): a single-centre, parallel-group, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet Haematol 2017;4 (06):e258–e271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Winearls J, Wullschleger M, Wake E, et al. Fibrinogen Early In Severe Trauma studY (FEISTY): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2017;18(01):241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]