The Problem:

The high costs of US healthcare system have historically been driven by a fee-for-service model that prioritizes quantity and complexity of services. In this framework, better patient outcomes are neither the central focus of treatment decisions, nor are they specifically incentivized1,2. In contrast, value-based healthcare is a model of medicine that uses the benefit-to-cost ratio to drive decision-making. Essentially, value-based care explores this question: How can patients achieve the best health and personal outcomes per dollar spent to attain them? In cancer treatment, where the concept of “financial toxicity” first emerged, this question is crucial as the rising costs of care have negative effects on a patients’ physical, mental, and social functioning3 and can decrease access to screening4 and treatment5.

Medical school is one of the earliest opportunities to teach physicians the basics of value-based healthcare, with earlier education creating an opportunity for quicker knowledge consolidation and application. Many have suggested that a foundation in the principles of value-based care should be provided for all medical students6,7. A national effort to create high-quality curriculum that spans students’ undergraduate medical education could create physicians exposed to and comfortable with applying value-based care sooner; the goal is to provide all future physicians the ability to be better equipped to attain effective outcomes for their patients. This early exposure could help lead to systemic change by helping to change the dynamics of the low-value, low-quality US medical system8.

This project evaluates the quantity and quality of medical school education on value-based care and affordability received by radiation oncologists. Due to the rising financial burden of cancer care, these topics are crucial for their roles providing cancer treatment and, overall, this topic is valuable to all physician specialties due to the high-cost, low-value nature of the current healthcare system.

What we did:

Current radiation oncology trainees and recent graduates were surveyed using an anonymous 17-question RedCap online questionnaire created by the investigation team. The survey assessed education on costs, affordability, and value during medical school, including didactic lectures and discussions during rotations in the hospital. It also assessed familiarity with value-based care concepts and pricing/charges for medical services. Examples of topics that fall under value, cost, and affordability were used when assessing participant knowledge. Full survey is available in the Appendix.

Trainees were identified from a list of recent radiation oncology residency applicants to Memorial Sloan Kettering which is a 24 resident program and receives approximately 150 applications per year. Eligible trainees graduated from a US medical school between 2016–2021, and had publicly available emails and/or public Twitter accounts; they were contacted once between June 2021-April 2022. The study was given an exemption by the Institutional Review Board given anonymous survey design. Participants acknowledged consent by clicking through a screening question; they were not compensated for participation.

Between June 2021-June 2022, the top 50 US medical schools (via the 2021 US News and World Report list) were contacted and asked to provide curriculum documentation and responses to queries regarding education in value-based care and social determinants of health (SDoH). Those contacted held roles in curriculum development/management, the American Medical Association Health Systems Scholar Program, or medical education. Curriculum information was also collected from school websites as well as via targeted searches (combining the school name with “high-value care” and “value-based care”). A curriculum was noted to have inclusion of evaluated topics (value, healthcare economics, SDoH) based on the presence of the specific keywords within curriculum descriptions (see Supplemental Table 1). Timing (pre-clerkship, clerkship, post-clerkship) and didactic methods were also assessed when available.

Descriptive statistics characterized survey responses and curriculum topics. Non-parametric univariate tests (chi-square, Mann-Whitney U, Spearman correlation) evaluated the relationship between education received and time since graduation, geographic location of medical school, and self-rated knowledge. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05, without adjustment for the number of comparisons.

Outcomes and Limitations:

Of 276 contacted recent graduates, 86 completed the initial screening question with 4 ineligible, leaving a final sample n=82 (30% response rate). Demographic information is shown in Supplemental Table 2. Among respondents, 96.3% (n=79/82) reported having met patients who were unable to afford their health care. The majority (87.8%, n=72/82) reported receiving “marginal” to “insufficient” education on value, affordability, and cost during medical school.

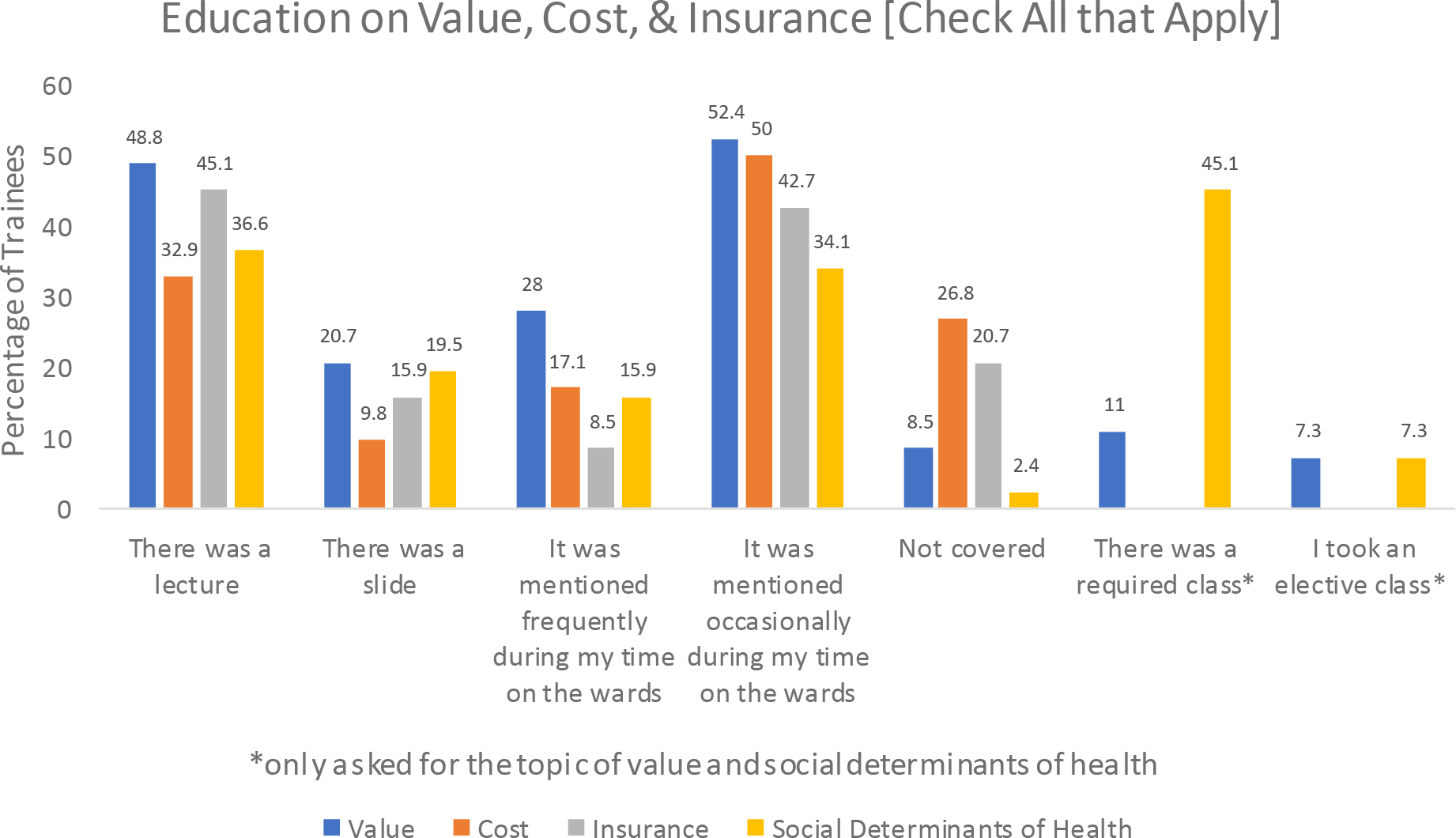

The Figure shows survey responses to specific education topics (i.e., value, cost, insurance, SDoH) and methods used to teach students. There was no education on improving patient affordability for 35.8% (n=28/81) of respondents; 20.7% (n=17/82) had no education on health insurance; and 26.8% (n=22/82) had no education about costs. Comparatively, nearly all respondents (97.6%, n=80/82) reported receiving education on the social determinates of health. During clinical rotations, respondents reported that value and/or cost were rarely (38.3%, n=31/81) or never (30.9%, n=25/81) discussed at the point of care (i.e., when the test was being suggested or ordered); only one recent medical graduate stated that it was discussed in most cases, with 29.6% (n=24/81) said it was discussed in some cases (i.e., when a test was deemed to be expensive or a patient was uninsured).

Figure.

Education methods* for value, cost, insurance, and social determinants of health.

*Check all the apply questions: Did you have any education about... value in health care (including decreasing the use of low value care/unnecessary tests), costs (including charged/billed price or costs to the patient), health insurance (including types of health insurance, premiums, deductibles, co-payments, co-insurance), the social determinates of health.... in medical school?

The Table shows respondents’ knowledge of key prices/costs and value concepts and guidelines. One-half had no idea about the billed/charged prices, and just over one-half (55.6%) did not know the out-of-pockets costs of any common tests, procedures, or medications.

Table.

Trainee knowledge of costs and financial stewardship guidelines and concepts

| “Do you know the [charged/billed prices] or [out of pocket costs] for any common tests, procedures, or medications?” | Charged/Billed prices | Out of pocket costs |

| Percentage (n=82) | Percentage (n=81) | |

| I have a good idea | 8.5% (7) | 6.2% (5) |

| I have a vague idea | 41.5% (34) | 38.3% (31) |

| I have no idea | 50% (41) | 55.6% (45) |

| “Are you aware of [the ‘Choosing Wisely’ Campaign] or [the concept of “financial toxicity]?” [Check all that apply] | “Choosing Wisely” Campaign | Financial Toxicity |

| Percentage (n=82) | Percentage (n=82) | |

| Yes - I know the guidelines/concept very well | 8.5% (7) | 31.7% (26) |

| Yes - I know of it (but not in detail) | 48.8% (40) | 51.2% (42) |

| Yes - but I learned about it during residency/fellowship, not during medical school | 17.1% (14) | 20.7% (17) |

| None | 31.7% (26) | 2.4% (2) |

In chi-square testing, medical school location was not associated with any aspect of classroom education (lectures or slides) or clinical education related to value, cost, insurance, or SDoH (all p>.05). Years since graduation, however, was associated with classroom education, such that respondents who reported receiving lectures on value (mean years “yes” = 3.35, mean years “no”=4.17; U=585.5, p=.014), cost (mean years “yes”=3.15, mean years “no”=4.07; U=479.5, p=.008), and insurance (mean years “yes”= 3.19, mean years “no”= 4.24; U=516.5, p=.003) had graduated more recently than those who did not. There was no difference in report of lectures on SDoH (mean years “yes”=3.50, mean years “no”=3.92; U=642, p=.18) or affordability (mean years “yes”=3.72, mean years “no”=3.79; U=755.5, p=.90) nor clinical education for any topic by time since graduation (all p>.05).

Self-reported knowledge of charged/billed prices for common tests, procedures, and medications had a strong and significant positive correlation with self-reported knowledge of patient out-of-pocket expenses (ρ=.67, p<.001) and a significant moderate positive correlation with the amount of discussion related to value/cost (ρ=.42, p<.001) and satisfaction with value, cost, and affordability education (ρ=.35, p=.001). Self-reported knowledge of patient out-of-pocket costs was positively correlated with the amount of cost discussion (ρ=.39, p<.001) but not with satisfaction with value education during medical school (ρ=.21, p=.06).

When respondents were asked how they believe value education could be improved, they suggested embracing a “holistic” approach for value education, including teaching value and cost alongside information on “the origins of the US healthcare system, patterns of care and utilization, insurance coverage, socioeconomic determinants of health”. One respondent highlighted that better value education “starts from the educators - the clinicians who are prescribing and thus teaching us”; another respondent noted that they would benefit from education that would help them “be able to advocate for my patients” and connect them to resources. Additional comments included the need to reform the healthcare system and to have point of care costs of services care embedded in the electronic medical record system when ordered.

Of the top 50 medical schools, 24% (n=12) responded to direct inquiries about their curriculum; the remaining schools were assessed based on curriculum available online. Forty-eight percent of top schools (n=24) had identifiable value or healthcare economics education in their curriculum; comparatively, 92% had SDoH education as part of their curriculum. Schools with identifiable value/health economics education reported it occurred during pre-clerkship (29.2%, n=7), clerkship (25%, n=6), post-clerkship (16.7%, n=4), multiple time points (20.8, n=5), and unknown (8.3%, n=2) periods. Value education was taught through lecture/didactics (58.3%, n=14) and group discussion (54.2%, n=13).

Limitations and Contextualization

Limitations include lack of detailed curriculum descriptions and limited inquiry responsiveness from schools. Additionally, generalizability of trainee data is limited by small sample size, single specialty focus, and the low response rate which is characteristic of physician surveys. The survey itself was developed for this study and thus not validated; to authors’ knowledge, there are no validated surveys of education on this topic.

Our study highlights a lack of consistent value-based education among current and recent radiation oncology residents and inconsistent integration of value-based concepts into the curricula of top US medical schools. The majority of trainees report limited knowledge of cost and charges their patients face despite virtually all recent graduates knowing someone who was unable to afford their care. Thankfully, there appears to be positive improvement over time in value education for trainees and some promise that the next generation will have a better foundation to provide more value-focused care.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

LB is funded by the Memorial Sloan Kettering Summer Fellowship NIH 5R25CA020449–43 Grant; FC and BT are funded in part through the NIH/NCI Support Grant P30 CA008748

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Leadership Roles: FC has leadership roles at ASTRO as a member of the Health Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Counsel and is on the steering committee of ASCO Quality; she is also a director the Costs of Care group.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Data Statement:

The authors declare that they had full access to all of the data in this study and the authors take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

References:

- 1.Emanuel EJ, Fuchs VR. The perfect storm of overutilization. JAMA. Jun 18 2008;299(23):2789–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.23.2789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Erickson SM, Outland B, Joy S, et al. Envisioning a Better U.S. Health Care System for All: Health Care Delivery and Payment System Reforms. Ann Intern Med. Jan 21 2020;172(2 Suppl):S33–S49. doi: 10.7326/M19-2407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith GL, Banegas MP, Acquati C, et al. Navigating financial toxicity in patients with cancer: A multidisciplinary management approach. CA Cancer J Clin. Sep 2022;72(5):437–453. doi: 10.3322/caac.21730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miles RC, Flores EJ, Carlos RC, et al. Impact of Health Care-Associated Cost Concerns on Mammography Utilization: Cross-Sectional Survey Results From the National Health Interview Survey. J Am Coll Radiol. Jul 14 2022;doi: 10.1016/j.jacr.2022.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Thom B, Benedict C, Friedman DN, Watson SE, Zeitler MS, Chino F. Economic distress, financial toxicity, and medical cost-coping in young adult cancer survivors during the COVID-19 pandemic: Findings from an online sample. Cancer. Dec 1 2021;127(23):4481–4491. doi: 10.1002/cncr.33823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cooke M Cost consciousness in patient care--what is medical education’s responsibility? N Engl J Med. Apr 8 2010;362(14):1253–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp0911502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teisberg E, Wallace S, O’Hara S. Defining and Implementing Value-Based Health Care: A Strategic Framework. Acad Med. May 2020;95(5):682–685. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holtzman JN, Deshpande BR, Stuart JC, et al. Value-Based Health Care in Undergraduate Medical Education. Acad Med. May 2020;95(5):740–743. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that they had full access to all of the data in this study and the authors take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.