Abstract

Objective:

Modest agreement between mothers’, fathers’, and teachers’ reports of child psychopathology can cause diagnostic ambiguity. Despite this, there is little research on informant perspectives of youth’s limited prosocial emotions [LPE]. We examined the relationship between mother-, father-, and teacher-reported LPE in a clinical sample of elementary school-aged children.

Method:

The sample included 207 primarily Caucasian (n = 175, 84.5%) children (136 boys; 65.7%) aged 6 to 13 years (M = 8.35, SD = 2.04) referred to an outpatient child diagnostic clinic focused on externalizing problems. We report the percentage of youth meeting LPE criteria as a function of informant perspective(s). Utilizing standard scores, we report distributions of informant dyads in agreement/disagreement regarding child LPE, followed up by polynomial regressions to further interrogate the relationship between mother-, father-, and teacher-reported LPE as it relates to conduct problems.

Results:

The prevalence of child LPE was approximately twice as large when compared to those reported in community samples; mothers and fathers generally agreed on their child’s LPE symptoms (55% agreement). Higher-order non-linear interactions between mothers and fathers, as well as parents and teachers, emerged; discrepancies between informants, characterized by low levels of LPE reported by the child’s mother, were predictive of youth at the highest risk for conduct problems.

Conclusions:

The findings emphasize the clinical utility of gathering multiple reports of LPE when serious conduct problems are suspected. It may be beneficial for clinicians to give significant consideration to teacher reported LPE when interpreting multiple informant reports of LPE.

Keywords: limited prosocial emotions, conduct problems, conduct disorder, reporter discrepancy

Introduction

In Robert Evans’ The Kid Stays in the Picture (2002) it is noted that “There are three sides to every story: Your side, my side, and the truth. And no one is lying.” This sentiment likely hits close to home to those in the field of child and adolescent psychology, where discrepancies among informant reports serve as a rule rather than an exception. Despite being well-known that a single reporter confounds the assessment of youths’ psychological traits with the reporter’s perspective (Achenbach et al., 2005; Boyle & Pickles, 1997; Renk, 2005), analytic methods to incorporate information from several informants (e.g., mother, father, teacher) in a systematic manner remains limited (Achenbach et al., 2005; Bauer et al., 2013; Curran et al., 2021; De Los Reyes et al., 2013). This is particularly problematic in developmental psychopathological diagnosis, as there is only modest agreement across informants.

Meta-analyses over the past thirty years have been fairly consistent: the highest agreement is found between similar informants (e.g., mothers and fathers), followed by different types of informants (e.g., parents and teachers), with the lowest agreement found between self-report and other. In terms of the type of psychological symptoms being reported, greater agreement among informants is typically found for externalizing, when compared to internalizing, problems (Achenbach et al., 2005; Achenbach et al., 1987; De Los Reyes et al., 2015; Duhig et al., 2000; van der Ende et al., 2020). Importantly, discrepancies in reporting of youths’ psychopathological symptoms among informants predict greater maladjustment, a poor response to psychological treatment, and other negative outcomes (De Los Reyes, 2011; Goolsby et al., 2018). They also provide evidence of variations in the child’s functioning across different environments (De Los Reyes, 2011). At the same time, however, these discrepancies can cause confusion and diagnostic ambiguity, affecting clinical judgment and potentially leading to misdiagnosis, overdiagnosis, or underdiagnosis, and therefore prevent children from receiving treatment (Creswell et al., 2021; De Los Reyes, Talbott, et al., 2022; Ford & McCoy, 2021; van Doorn, 2019).

While substantial attention has been paid to discrepant reporting of anxiety (e.g., Bowers et al., 2020), depression (e.g., Baumgartner et al., 2021), inattention/hyperactivity (e.g., Saffer et al., 2021), as well as aggression (e.g., Chana et al., 2020; Fite et al., 2016) and rule-breaking behavior (e.g., Laird & LaFleur, 2016), there is considerably less research on informant perspectives of youth’s limited pro-social emotions [LPE]. The LPE diagnostic specifier, introduced in the latest version (5th) of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association & Association, 2013) is provided if, in addition to meeting full criteria for conduct disorder, youth show two or more characteristics of callous-unemotional traits (CU traits; e.g., lack of remorse or guilt, callous-lack of empathy, unconcerned about performance, shallow or deficient affect) for at least 12 months in more than one relationship or setting. While past research has reliably found differences in informant agreement between externalizing and internalizing domains, it is unclear how LPE fits into this dichotomous distinction. On the one hand, LPE as a construct is largely focused on affect (lack of guilt or remorse, shallow or deficient affect, lack of empathy, lack of caring). As such, LPE is arguably similar to internalizing psychopathology that (as described earlier) is associated with relatively lower agreement across informants. On the other hand, LPEs are associated with increases in aggression, rule-breaking, and oppositional behavior, which fall squarely within the externalizing domain and are thus arguably more like externalizing psychopathology with regard to informant agreement. Previous research has demonstrated that youth rated in discrepant ways by parents versus teachers on measures of disruptive behavior showed patterns that were consistent with these discrepancies on independent observations (De Los Reyes et al, 2009; see De Los Reyes, Wang, et al., 2022). In particular, youth with high CP, according to parent but not teacher ratings, were observed to be disruptive with parents but not unfamiliar adults; youth rated as disruptive, according to teacher but not parent ratings, were observed to be disruptive by non-parental adults but not with parents. Further, the relationship between structurally different informants’ report of child mental health (i.e., informants differing in where they observe the child) and clinically relevant domains (e.g., conduct problems) has been found to consist of upwards of 95% of unique variance (De Los Reyes, Wang, et al., 2022). Taken together, we posit that LPE informant discrepancies will reflect meaningful phenomena with predictive clinical utility.

The DSM-5 requires LPEs to be present in multiple relationships and settings –emphasizing that “multiple information sources are necessary” for the specifier to be diagnosed (American Psychiatric Association & Association, 2013, pg. 470). Moreover, given the threshold to meet LPE criteria (i.e., at least two of four total symptoms), discrepancies among reports (i.e., mother-, father-, and teacher-report) can make it difficult for clinicians to accurately determine if a child meets the criteria for the LPE specifier. This is particularly problematic as youth with conduct problems and LPE (compared to those without LPE) may have a poorer response to treatment and differ in diagnostic etiology (Bansal et al., 2019; Frick et al., 2014; Haas et al., 2011; Waschbusch et al., 2020). Further, children with LPE, regardless of diagnostic status, have significantly more impairment across a wide range of domains (peers, parents, family, academic, classroom, self-esteem; Castagna & Waschbusch, 2021). The goal of the current study is to provide further information on the potential differences in mother-, father-, and teacher-reported LPE in youth.

The methodology used to quantify or integrate different-informant reports in both research and clinical settings has important implications for diagnostic reliability and validity (Martel et al., 2021). Fortunately, there have been recent developments in ways to understand the information conveyed by these differences in opinion by using novel analytic strategies (Horton & Fitzmaurice, 2004). Traditionally, researchers used a difference score approach to compare informant reports (i.e., subtracted one informant’s score from another informant’s score), with difference scores then regressed onto or correlated with other variables of interest. More recently, this method has fallen out of favor given the growing research detailing its limitations (Laird & De Los Reyes, 2013; Laird & LaFleur, 2016; Laird & Weems, 2011; Meyer, 2017; Meyer et al., 2013; Meyer et al., 2017). Specifically, mean differences between informants can obfuscate the picture by masking factors that could be related to agreement by restricting associations between reporters as being in complete agreement, orthogonal to one another, or of equal magnitude (Laird & De Los Reyes, 2013; Laird & LaFleur, 2016; Laird & Weems, 2011). Critically, examining informant discrepancies through difference scores brings with it an assumption of a new construct that is not a result of the individual reports used to assess it, a fatal flaw for testing incremental validity. The statistical remedy to address this methodological shortcoming is to place the emphasis on directly testing the incremental value of the discrepancies, relative to the unique and additive explanatory power, of the individual informant’s reports (Laird & De Los Reyes, 2013).

Polynomial regression analysis is recommended to examine the degree and direction of congruency or discrepancy between two individuals’ reports and the extent to which this congruency or discrepancy predicts the outcome (Edwards, 1994; Edwards & Parry, 1993). Indeed, this approach has proven useful in illuminating factors associated with informant differences in youth psychopathology (Castagna et al., 2019; Castagna, Laird, et al., 2020). Put simply, polynomial regressions allow for a direct examination of whether differences between informants contribute to predicting outcome variables beyond the main effects of individual reports. Further, they can be adapted to explore discrepant views as either predictors, outcomes, or both (De Los Reyes, Ohannessian, et al., 2016; Laird & De Los Reyes, 2013; Laird & LaFleur, 2016). In the current study, we leveraged polynomial regressions to assess the relationship between mother-, father-, and teacher-reported youth LPE as it relates to conduct problems [CP].

To our knowledge, no studies have used this approach to compare the report of different informants – namely, mother, father, and teacher – of LPE in youth. However, some studies have examined the reliability and validity of CU traits as reported by mothers, fathers, and teachers of elementary school children. In a comprehensive meta-analytic review, Frick et al. (2014) reported that the average correlation between different informants of LPE/CU, based on 13 studies that reported 24 correlations, was .24 (range: −.09 to .54), which is broadly consistent with other forms of child psychopathology. Research published since this review has provided additional detail about this pattern. For example, a meta-analysis of the ICU that included 146 studies found that multi-informant studies were less common than single-informant studies, and parent report was more common than teacher report (Deng et al., 2019). Almost no studies were included that separated mother and father reports. Importantly, the overall internal consistency reliability was acceptable (> .84) for all informants (mother, father, teacher). A study of 236 children in grades 3, 6, and 8 reported that parent and teacher ratings using the ICU were significantly but modestly correlated (r = .18) and that teachers rated LPE higher than parents in third and sixth grade children. Results also showed that both parent and teacher ratings of CU were significantly and similarly correlated with validity measures that included CP, social preference, and peer nominations of being mean/cold, but teacher ratings were more highly correlated with peer nominations of being not nice than were parent ratings. Finally, this study showed that in third and sixth grades teachers explained unique variance in validity measures beyond parent and self-report of CU, whereas parents did not (Matlasz et al., 2021). Another study of 805 elementary school-age children reported that an LPE latent factor was invariant across mothers and fathers, across different teachers, and between home and school, and that mother and father ratings of LPE were significantly correlated, as were primary and ancillary teacher ratings, but parent and teacher ratings of LPE were not correlated (Seijas et al., 2018). Results also showed that father ratings had a significantly lower latent mean than mother ratings, but the difference was small (Cohen’s d = .17), whereas other informants did not differ. In the same sample, Seijas et al. (2018) reported that parent and teacher ratings of LPE were not significantly correlated in first grade or one year later in second grade, with other results suggesting LPE was more trait-like when rated by mothers and fathers but more state-like when rated by teachers. In a smaller study (N = 95) of children, Barhight et al. (2017) found a moderate association between parent- and teacher-reported CU traits (r = .26). Again, both reports were significantly correlated with child aggression. Finally, a study of 977 elementary school children from China reported significant but low correlations between mother and teacher reports of callousness (r = 11) and uncaring (r = .15) as measured by a short form of the ICU, and that teachers rated children higher than parents on these scales (Wang et al., 2020). While research is limited, past research indicates a low to moderate relationship between parent- and teacher-reported CU traits. With the focus on parents, it is currently unknown how this relationship differs between mother- and father-reported youth CU/LPE.

The current study had several goals aimed at providing clinicians and researchers with information on the relationship between mother-, father-, and teacher-reported LPE in youth. First, we report the percentage of youth in our sample that meet LPE criteria as a function of perspective (i.e., mother, father, or teacher) and the number of informants (i.e., single informant, two informants, or all three informants). It is hypothesized that the largest proportion of youth meeting LPE specifier criteria will be obtained when informant replacement (e.g., mother-, father-, or teacher-report) is used when compared to without replacement (e.g., mother-, father- and teacher-report). Second, we also report distributions of informant congruency via the percentage of informant dyads in agreement and disagreement regarding mean LPE utilizing standardized scores (Shanock et al., 2010). Third, we explore correlations among mother-, father-, and teacher-reported LPE, as measured by the Limited Prosocial Emotions Questionnaire (LPEQ; Castagna, Babinski, et al., 2020), CP, and demographic variables (i.e., age, sex). With past research indicating low to moderate agreement between parent- and teacher-reported CU traits, a construct highly related to LPE (Barhight et al., 2017; Matlasz et al., 2021; Seijas et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2020), we posit that there will be a moderate association among mother-, father-, and teacher-reported LPE. Finally, in an exploratory nature, we utilize polynomial regressions to examine the relationship between mother-father, mother-teacher, and father-teacher reported youth LPE. Given the dearth of literature on informant discrepancy of LPE, we did not have specific hypotheses regarding these analyses.

Method

Participants

Participants were 207 children (136 boys; 65.7%) aged 6 to 13 years (M = 8.35, SD = 2.04) years, who were referred to an outpatient child diagnostic clinic focused primarily on ADHD, ODD, CD, and related conditions. Most of the sample was Caucasian (n = 175, 84.5%), and the median family income was between $40,000 and $50,000 (SD = $29,230). Exclusion criteria included a past or current diagnosis of autism, psychoses, or other similar forms of serious psychopathology and any physical or medical condition that would preclude completing the assessment. The majority of the sample was diagnosed with ADHD (84%) and/or ODD (57%).

Procedure

Data were collected as part of a comprehensive psychosocial evaluation conducted by a licensed Ph.D. psychologist. As part of the evaluation, ratings were collected from the child’s primary female and male caregivers (hereafter referred to as mother and father) and the homeroom teacher. The use of these assessment data for research was approved by the Institutional Review Board which waived informed consent/assent because analyses were conducted retrospectively on existing clinical records.

Measures

Disruptive Behavior Disorders Rating Scale (DBD).

The DBD consists of 45 items that correspond to the DSM-5 symptoms of childhood externalizing disorders (i.e., attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], oppositional defiant disorder [ODD], and conduct disorder [CD]) (Pelham, Gnagy, et al., 1992). Items such as, “has been physically cruel to people,” are assessed on a 4-point Likert-type scale that ranges from 0 (Not at All) to 3 (Very Much). CP symptom count consisted of the mean number of DSM-5 symptoms of ODD and CD for mother- (M = 2.96, SD = 2.59; M = 0.87, SD = 1.41, respectively), father- (M = 2.33, SD = 2.31; M = 0.59, SD = 1.14, respectively), and teacher-report (M = 1.79, SD = 2.35; M = 0.41, SD = 0.93, respectively). The DBD has strong psychometric properties which have been reported elsewhere (Pelham, Evans, et al., 1992; Wright et al., 2007).

Limited Prosocial Emotions Questionnaire

(LPEQ; Castagna, Babinski, et al., 2020; Castagna et al., 2021). The LPEQ is a six-item scale that was developed to measure the extent to which the youth has LPE as defined by the DSM-5 specifier of conduct disorder. The first three items were designed to assess lack of remorse or guilt, callous and lack of empathy, and lack of concern about performance components of the LPE specifier. The fourth and fifth items were designed to assess different aspects of the “Shallow or Deficient Affect” component of the LPE specifier. That is, the LPE specifier indicates that either a lack of emotion or only using emotion manipulatively is evidence of shallow or deficient affect. Therefore, these aspects (lack of emotion vs. only manipulative use of emotion) were examined in separate items. To be consistent with the DSM-5, items assessing the two aspects of shallow or deficient affect (items 4 and 5) were combined by taking the larger score, and this combined score is hereafter referred to as item 4/5. Items 1 through 4/5 were rated using a four-point Likert scale that asks how much the youth is like each item: 0 (Not at All Like This), 1 (Just a Little Like This), 2 (Pretty Much Like This), or 3 (Very Much Like This). The sixth item was designed to assess impairment from the LPE indicators and is rated using a four-point Likert scale but with different anchors: 0 (No Problems), 1 (Mild Problems), 2 (Moderate Problems), and 3 (Serious Problems). The LPEQ total score used here reflects the mean of items 1 through 4/5.

Analytic Plan

Preliminary Analyses

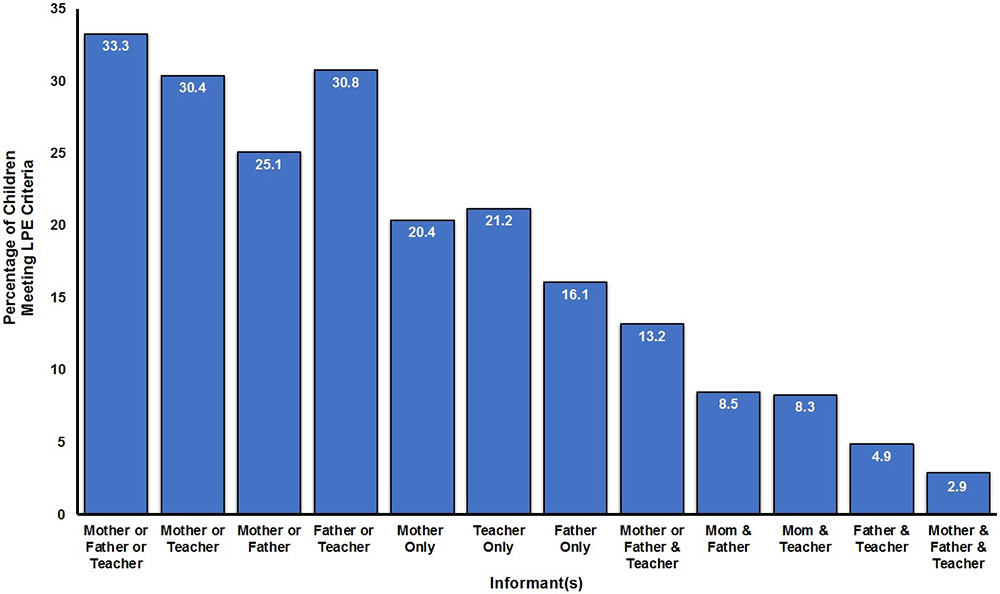

First, we report the percentage of youth within our sample meeting criteria for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual – 5th edition (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association & Association, 2013) Limited Prosocial Emotion specifier (i.e., two or more of the four indicators) as a function of the informant(s) report used (e.g., mother only, mother-father, mother-teacher, etc.). This descriptive account was examined as it links our main analyses regarding potential informant differences of youth LPE to their diagnostic clinical implications, namely whether they meet DSM-5 LPE specifier criteria. The LPE Group (present vs. absent) was created based on the LPEQ to be consistent with DSM-5; LPE criteria were met if two or more of the four LPE specifier indicators were present (defined as ratings of “Pretty Much Like This” or “Very Much Like This”) and if those indicators were associated with impairment (defined as ratings of causing “Moderate” or “Serious” problems). See Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Percentage of children meeting limited prosocial emotion criteria, as measured by the LPEQ, as a function of type and number of informants utilized.

Second, we provide a descriptive account of the number of mother-father, mother-teacher, and father-teacher dyads demonstrating discrepancies in their report of a child’s LPE symptoms (Edwards, 1994). We standardized and compared mothers’, fathers’, and teachers’ reports of youths' limited prosocial emotions as measured by the LPEQ. To this end, we followed the advice of Shanock et al. (2010) and examined the standardized scores (SS) highly discrepant (i.e., −0.50 > SS > 0.50) and those that are similar (i.e., −0.50 ≤ SS ≤ 0.50) to determine the frequency of congruence/discrepancy between the three aforementioned parent-teacher dyads. See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Congruence and incongruence of mother-father, mother-teacher, and father-teacher dyads report of youths limited prosocial emotions.

Bivariate Correlations & Mean Differences

To evaluate whether mother, father, and teacher ratings of LPE were associated with each other and with the ICU, Pearson simple and partial correlations were computed. Consistent with similar past work (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2004; Deros et al., 2018), we used the Williams t-test for comparing differences between dependent correlations (Steiger, 1980). To determine whether parents or teachers systematically over- or under-estimate child LPE relative to each other, paired-sample t-tests were computed between dyad pairs (i.e., mother-father, mother-teacher, and father-teacher) at the item level (i.e., lacks remorse/guilt, callous – lacks empathy, unconcerned performance, shallow/deficient affect, and emotional manipulation), as well for the overall mean total score of the LPEQ.

Polynomial Regressions

To examine how agreement/disagreement between parent-teacher dyads relates to a composite of CP, we conducted three polynomial regression models, for which all independent variables were standardized. The outcome variable only included the reports of the informant predictors (e.g., the mother-father polynomial regression outcome variable was a composite of the parent- and teacher-reported DBD CP, described in more detail below). For clarity, we describe the mother-teacher dyad polynomial model, though all three (i.e., mother-father, mother-teacher, and father-teacher) were run in the same manner. In the first step, the CP composite was regressed on model covariates, if any, found to be related to the outcome variable from our correlation analyses (e.g., child age and sex). In the second step, the main effects of mother- and teacher-reported child LPE were included. The third step included the quadratic term for either mother-reported child LPE (X2), the interaction term for mother- and teacher-reported child LPE (X × Z), as well as the quadratic term for teacher-reported child LPE (Z2). The fourth and final step was comprised of the higher-order quadratic mother by teacher interaction (X2 × Z) and quadratic teacher by mother interaction (and Z2 × X). Normality was examined through kurtosis and skewness values (i.e., > +/−1 and > +/− 3, respectively), as well as visual inspection of histograms.

The third step of the polynomial regression model steps, which included the two higher-order interactions (e.g., X2 × Z), was only examined when it explained a meaningful amount of variance, as evidenced by a significant ΔF-value. Consistent with past research (Laird & De Los Reyes, 2013), the quadratic term of the interaction was interpreted as the independent variable, where the linear variable served as the moderator to facilitate plotting. Simple slopes at high (+1 SD) and low (−1 SD) levels of the moderator (Cohen et al., 2003) were calculated for significant interaction terms.

Outcome Variable

Mean mother CP (M = 1.91, SD = 1.83, Range = 0 to 8), father CP (M = 1.46, SD = 1.39, Range = 0 to 7), and teacher CP (M = 1.10, SD = 1.06, Range = 0 to 7) were found to be comparable to past research using clinical samples. We used principal components analysis to create a composite child CP index across the informants. Crucially, three composites were created for the three polynomial regressions such that the outcome only included the reports of the informant predictors (e.g., the mother-father polynomial regression outcome variable was a composite of mother and father CP). The mother-father, mother-teacher, and father-teacher PCA analyses all yielded one component accounting for 76.26%, 66.08%, and 60.71% (respectively) of the variance in these measures (eigenvalues = 1.53, 1.32, 1.19, respectively). While our approach is similar to other procedures in the field, such as the Kraemer’s satellite model (Kraemer et al., 2003; see Makol et al., 2020) often used within the operations triad model framework (De Los Reyes et al., 2013), our procedure was selected given our interest in all three informants, where two share context (i.e., home vs. school) and perspective (parent vs. teacher).

Results

Figure 1 depicts a bar graph of the percentage of children meeting DSM-5 limited prosocial emotion [LPE] criteria as a function of the type of informant (i.e., mother, father, or teacher), the number of informants used (i.e., one, two, or three), and type of reporter combination (e.g., mother or teacher versus mother and teacher). Unsurprisingly, using an ‘either or’ approach led to the highest number of children meeting LPE criteria, followed by single informants only, and finally by requiring multiple informants (i.e., the ‘and’ approach). Approximately one-third of the sample met the criteria if mother, father, or teacher report was utilized, an over 10-fold difference from the 2.9% when mother, father, and teacher report was relied on. Out of the three possible dyads, relying on father-teacher or mother-teacher report led to more children meeting LPE criteria when compared to mother-father report. Consistent with the DSM-5, which states that evidence for LPE needs to be present in multiple environments (e.g., home and school), the prevalence of children meeting criteria as a function of mother- or father-reported LPE and teacher-reported LPE was found to be 13.2% (78.6% meeting criteria for conduct disorder and/or oppositional defiant disorder).

Table 1 contains descriptive statistics and the results of paired-samples t-tests of mother-, father-, and teacher-reported child LPE at the item-level and for the mean total score. Overall, mothers, fathers, and teachers did not report significant mean differences in child LPE. At an item level, teachers tended to report significantly more child callousness/lack of empathy (M = .67, SE = .07) when compared to mothers (M = .46, SE = .06), t(198) = −1.95, p < .05, Cohen’s d = .15. A similar pattern was found for teacher-reported shallow/deficient affect (M = .53, SE = .06) when compared to mothers (M = .37, SE = .05), t(198) = −2.37, p < .01, Cohen’s d = .18. Interestingly, teachers reported significantly less child emotional manipulation (M = .42, SE = .06) when compared to both mothers (M = .46, SE = .06), t(198) = 2.26, p < .01, Cohen’s d = .17, and fathers (M = .63, SE = .06), t(160) = 3.11, p < .01, Cohen’s d = .28. As shown in Figure 2, based on the standardized scores, mother-teacher and father-teacher dyads had similar distributions of congruence/incongruence; in approximately 30% of cases the parent reported higher levels of LPE, 40% of cases the parents and teachers reported similar levels of child LPE, and 30% of cases teachers reported higher levels of LPE compared to the parent. Furthermore, 19%, 55%, and 26% of mothers reported higher, similar, and lower child LPE when compared to fathers, respectively.

Table 1.

Means, SEs, and Paired-Samples t-Tests of Mother, Father, and Teacher Scores on the LPEQ.

| Mother |

Father |

Teacher |

Mother - Father (n=207) |

Mother - Teacher (n=199) |

Father - Teacher (n=161) |

Informant Differences |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPEQ Items | M | SE | M | SE | M | SE | t | d | t | d | t | d | |

| Lacks Remorse/Guilt | .79 | .07 | .78 | .07 | .85 | .07 | .08 | .01 | .00 | .00 | −.70 | .03 | ND |

| Callous – Lacks Empathy | .46 | .06 | .48 | .06 | .67 | .07 | −.42 | .05 | −1.95 | .15 | −1.86 | .12 | M < T |

| Unconcerned Performance | .98 | .07 | .88 | .06 | 1.10 | .08 | 1.45 | .09 | −1.73 | .12 | −1.89 | .12 | ND |

| Shallow/Deficient Affect | .37 | .05 | .44 | .06 | .53 | .06 | −1.25 | .08 | −2.37 | .18 | −1.00 | .05 | M < T |

| Emotional Manipulation | .52 | .06 | .63 | .06 | .42 | .06 | −1.57 | .13 | 2.26 | .17 | 3.11 | .28 | T < M, F |

| LPE Impairment | .97 | .07 | .97 | .07 | 1.08 | .07 | .00 | .00 | −1.35 | .09 | −1.09 | .14 | ND |

| Mean Total Score | .62 | .05 | .64 | .05 | .71 | .05 | −.49 | .05 | −1.01 | .08 | −.75 | .26 | ND |

Note. Values in bold font are significant at p < .05; M = mean; SE = standard error; t = t-score of paired samples t-tests; d = Cohen’s d; ND = no difference; M = mother; T = teacher; F = father.

Table 2 provides bivariate correlations for the study variables. As a preliminary analysis of the potential covariates to be included in the models, we were first interested in whether demographic characteristics (i.e., child age and sex) correlated with variables of interest. There was no relationship between CP composites and child age/sex. Therefore, a decision was made to not include demographic covariates in any of the three polynomial regression models1. Mother- and father-reported LPE had the most robust relationships (r = .55, p < .001), followed by mother-teacher (r = .31, p < .01), and father-teacher (r = .30, p < .05). The correlation between mother- and father-reported LPE was significantly different from both mother-teacher (Williams t = 2.92; p < .01) and father-teacher (Williams t = 3.06; p < .01) correlations. As expected, mother- (r = .61, p < .001), and father-reported LPE (r = .58, p < .001) was more robustly related to the mother-father CP composite when compared to teacher-report (r = .37, p < .001; Mother Williams t = 3.97; p < .001; Father Williams t = 3.51; p < .001 ). A slightly different pattern emerged between mother- (r = .56, p < .001), father- (r = .45, p < .001), and teacher-reported LPE (r = .63, p < .001) and the mother-teacher CP composite. Specifically, the correlation between mother-reported LPE and the mother-teacher composite did not significantly differ from the association between father-reported LPE (Williams t = 1.88; p = .06) nor teacher-reported LPE (Williams t = 1.10; p > .05) and the mother-teacher composite. The correlations between father- and teacher-reported LPE and the mother-teacher composite, however, did significantly differ (Williams t = 2.99; p < .01). The father-teacher CP composite was also robustly related to mother- (r = .37, p < .001), father- (r = .55, p < .001), and teacher-reported LPE (r = .59, p < .001). The correlation between mother-reported LPE and the father-teacher composite significantly differed from the association between father-reported LPE (Williams t = 2.87; p < .01) and teacher-reported LPE (Williams t = 3.45; p < .01) and the father-teacher composite. Yet, the correlations between father- and teacher-reported LPE and the father-teacher composite were not significantly different (Williams t = .57; p > .05).

Table 2.

Pearson Correlations of study variables.

| Variables | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | M (SE) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Child sex (Male = 1) | – | ––– | ||||

| 2. Child age | −.08 | – | 8.35 (.14) | |||

| 3. Mother-Reported LPE | .02 | .02 | – | .62 (.05) | ||

| 4. Father-Reported LPE | .06 | .08 | .55 | – | .64 (.05) | |

| 5. Teacher-Reported LPE | .21 | −.05 | .31 | 30 | – | .71 (.05) |

| 6. Mother-Father CP Composite | .01 | −.01 | .61 | .58 | .36 | .00 (.95) |

| 7. Mother-Teacher CP Composite | .16 | −.08 | .56 | .45 | .63 | .00 (.96) |

| 8. Father-Teacher CP Composite | .11 | −.05 | .37 | .55 | .59 | .00 (.93) |

Note. bold correlations = p < .001; LPE = limited prosocial emotions, as measured by the LPEQ; CP = conduct problems, as measured by the DBD; M = mean; SE = standard error; child sex was coded as 0 = girl, 1 = boy.

The first polynomial regression model2 examined mother- and father-reported child LPE (linear, quadratic, and linear interaction) as predictors of youth CP (Durbin-Watson = 2.16). The overall model explained 71.8% of the variance in child CP, F(7, 195) = 28.63, p < .0001, with an adjusted R2 value of .50. The third step explained a significant amount of variance, ΔF(2, 188) = 3.69, p < .05, where the change in R2 indicated that the higher-order items (i.e., step three) explained an additional 3% of the variance. In addition to the main effect of mother reported LPE (β = .47, SE = .38, p < .05), the interaction between the quadratic effect of mother-reported LPE and father-reported LPE (β = 1.37, SE = .26, p < .02) were significant predictors of youth CP. The interaction between the quadratic effect of mother report and father report was positive, where there was a weaker relationship at low levels of father-reported LPE, β = .98, SE = .26, p < .05, but a stronger relationship at high levels of father-reported LPE, β = 1.84, SE = .26, p < .05, see Figure 3A. The results indicate that patterns of agreement and discrepancy between mother- and father-reported LPE contributed incrementally to the prediction of child CP.

Figure 3.

Polynomial regressions of (A) mother– father, (B) mother–teacher, and (C) father–teacher perceived youth LPE predicting a composite of youths’ conduct problems; quadratic main effect of mothers’, fathers’, and teachers’ report of youth LPE predicting youths’ conduct problems; LPE = limited pro-social emotions.

The second polynomial regression model examined mother- and teacher-reported child LPE (linear, quadratic, and linear interaction) as predictors of youth CP (Durbin-Watson = 2.10). The overall model explained 75.0% of the variance in child CP, F(7, 195) = 33.39, p < .0001, with an adjusted R2 value of .55. The third step explained a significant amount of variance, ΔF(2, 182) = 7.05, p < .001, where the change in R2 indicated that the higher-order items (i.e., step three) explained an additional 4% of the variance. In addition to the main effect of mother reported LPE (β = .45, SE = .35, p < .05), the interaction between the quadratic effect of teacher-reported LPE and mother-reported LPE (β = −1.11, SE = .17, p < .001), as well as the quadratic teacher main effect (β = 75, SE = .18, p < .001) were significant predictors of youth CP. The interaction between the quadratic effect of teacher report and mother report was negative, where there was a weaker relationship at low levels of mother-reported LPE, β = −.80, SE = .16, p < .001, but a stronger relationship at high levels of mother-reported LPE, β = −1.53, SE = .16, p < .001, see Figure 3B. These results indicate that the discrepancy between mother- and teacher-reported LPE contributed incrementally to the prediction of child CP.

The final polynomial regression model examined father- and teacher-reported child LPE (linear, quadratic, and linear interaction) as predictors of youth CP (Durbin-Watson = 1.66). The overall model explained 74.5% of the variance in child CP, F(7, 148) = 25.06, p < .0001, with an adjusted R2 value of .53. The third step explained a significant amount of variance, ΔF(2, 141) = 3.33, p < .05, where the change in R2 indicated that the higher-order items (i.e., step three) explained an additional 2% of the variance. In addition to the main effect of father reported LPE (β = .55, SE = .49, p < .05), the interaction between the quadratic effect of teacher-reported LPE and father-reported LPE (β = −1.09, SE = .30, p < .01), as well as the interaction between the quadratic main effect (β = .80, SE = .27, p < .01) were significant predictors of youth CP. The interaction between the quadratic effect of teacher- and father-report was negative, where there was a weaker relationship at low levels of father-reported LPE, β = −.80, SE = .30, p < .05, but a stronger relationship at high levels of father-reported LPE, β = −1.48, SE = .30, p < .05, see Figure 3A. The results indicate that patterns of agreement and discrepancy between father- and teacher-reported LPE contributed incrementally to the prediction of child CP.

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to provide clinicians and researchers with information on the relationship between mother-, father-, and teacher-reported limited pro-social emotions [LPE] in youth. To this end, we first reported the percentage of children in our sample that meet LPE criteria as a function of perspective (i.e., mother, father, or teacher) and the number of informants (i.e., single informant, two informants, or all three informants). We also explored the congruency (or lack thereof) in mother-, father-, and teacher-reported child LPE using several methodological techniques. Informant agreement/disagreement was examined through 1) strength of correlational relationships, 2) standardized scores, 3) simple mean differences, and 4) polynomial regressions.

Per DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association & Association, 2013), to meet the criteria for the LPE specifier youth need to show two or more characteristics of callous-unemotional traits (CU traits, i.e., lack of remorse or guilt, callous-lack of empathy, unconcerned about performance, shallow or deficient affect) in more than one relationship or setting. Notably, the DSM-5 emphasizes that “multiple information sources are necessary” for the specifier to be diagnosed (American Psychiatric Association & Association, 2013, pg. 470). We found support for our first hypothesis; the largest proportion of youth meeting LPE specifier criteria was obtained when analyzed with informant replacement (e.g., mother-, father-, or teacher-report) when compared to without replacement (e.g., mother-, father- and teacher-report).

As anticipated, the prevalence of children with LPE in this clinical sample was found to be much higher when compared to research conducted in community samples. For example, at the single informant level, Seijas et al. (2018) found 9.4% of mothers, 13.5% of fathers, and 14.8% of teachers reported two or more LPE symptoms in a community sample compared to 20.4% (Δ = +11%), 16.1% (Δ = +2.6%), and 21.2% (Δ = +6.4%) found in our clinical sample (respectively). When examining prevalence rates mirroring DSM-5 criteria (i.e., two or more symptoms endorsed by two or more informants from multiple settings), it was unsurprising that we also found a higher LPE prevalence when relying on mother’s and father’s reports (8.5% versus 4.7%). Similarly, we found the percentage of children with two or more symptoms in the home (mother- or father-report) and school (teacher-report) to be 13.2%, approximately three times greater than that found in a community sample (i.e., 4.0%; Seijas et al., 2018). Taken together, there appears to be approximately a two-fold increase in the prevalence of LPE in clinical versus community samples; the magnitude of which varies as a function of how informant reports were combined (i.e., using ‘and’ versus ‘or’ criteria).

We found a large correlation between mother’s and father’s reports of child LPE, which appears to be at the higher end of the range of correlations found in a meta-analytic review by Frick et al. (2014) (Mcorr = .24, range: −.09 to .54); however, very few studies that were reviewed separated mother and father reports. The few studies that separately examined mother- and father-report found a weaker relationship than that reported here (Matlasz et al., 2021; Seijas et al., 2018). The strength of the relationship also appears to be greater in magnitude when compared to other forms of child psychopathology (Achenbach et al., 2005; Achenbach et al., 1987; De Los Reyes et al., 2015; Duhig et al., 2000; van der Ende et al., 2020). Since this is the first study to look at mother-father effects in a clinical setting, it could be important for future research to examine whether the strength of the relationship between informants’ reports of LPE is moderated by setting (i.e., clinical versus community). Mother-teacher’s and father-teacher’s reports of child LPE had nearly an identical strength of relationship (r = .31 and .30, respectively). While this is one of the few studies comparing father’s and teacher’s reports of child LPE, our results are consistent with the moderate association between parent- and teacher-reported CU traits by Barhight et al. (2017), though there is substantial variation in the literature. For instance, while Seijas et al. (2018) did not find a relationship between parent and teacher ratings of LPE, Wang et al. (2020) reported a small correlation (r = .13), whereas Matlasz et al. (2021) found a slightly larger correlation (r = .18). Although, it is worth noting that the three aforementioned studies were again conducted in community samples. As previously mentioned, LPEs are similar to internalizing and externalizing spectra in that they are comprised of both covert and overt behaviors (respectively). When interpreted from this viewpoint, it is notable that the pattern of both mother-father and parent-teacher correlations correspond to those found in the report of child externalizing behaviors (De Los Reyes et al., 2015).

We directly examined informant agreement between mother-, father-, and teacher-reported LPE from three vantage points. First, we examined the standardized scores (SS, i.e., highly discrepant: 0.50 > SS > 0.50; similar: −0.50 ≤ SS ≤ 0.50). Interestingly, there was a similar proportion of agreement/disagreement among the three parent-teacher dyads. Mother-teacher and father-teacher dyads agreed in 40% of cases. In the remaining 60% of cases that were discrepant, it was approximately equally split between which informant was reporting more LPE symptoms. These results could be partially explained by some children displaying LPE symptoms in only one environment (i.e., home or school). A little over half of the parents agreed (within ±.5 SS) in their report of their child’s LPE traits.

Second, we explored informant agreement through mean differences, where we did not find evidence of meaningful differences between mother-, father-, and teacher-reported total LPE scores. A few differences, however, did emerge for single LPE traits (i.e., at the item level), though the effect size of these differences was small; mothers tended to report less callousness/lack of empathy and shallow/deficient affect than teachers. These findings are consistent with previous studies, which often show a tendency for teachers to rate children higher on LPE than parents, but the differences are small (Matlasz et al., 2021; Seijas et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020). Interestingly, teachers were found to report significantly less emotional manipulation when compared to mothers and fathers, where the latter was approaching a medium effect size. While purely, this finding may reflect true differences in a child’s use of emotional manipulation between environments (i.e., at home versus school). It is also feasible that children may have more success emotionally manipulating his/her parents (when compared to their teacher), reinforcing this behavior at home where parents have access to potential reinforcers (e.g., buying a toy) and removal of potential punishers (e.g., completing chores). An alternative explanation is that emotional manipulation may present as a more subtle behavior, to which parents are attuned, or the behavior only becomes salient over longer periods. To our knowledge, this is the first study to specifically examine informant differences in ratings of child emotional manipulation and it appears to be a topic that warrants future study.

Third, the results of the three polynomial regressions examining mother-father, mother-teacher, and father-teacher informant agreement provide additional information beyond the correlations, standard score, and mean difference analyses. Across all models, a theme emerged suggesting that disagreement of child LPE between mother-father and mother-teacher report, where mothers reported low levels of LPE (and fathers and teachers are reporting high levels of LPE, respectively), was predictive of youth having a level of conduct problems similar to when mothers and fathers/teachers agreed on elevated child LPE. Perhaps mother-father or mother-teacher disagreement of LPE may reflect mothers under-reporting the degree of LPE their child is exhibiting. It is also conceivable that children with LPE are more successful in manipulating their mothers (compared to fathers and teachers) to perceive their behaviors in a more positive light.

Our findings concerning the two teacher models potentially highlight the utility of gathering teacher-reported child LPE in clinical settings. Overall, mother-teacher and father-teacher LPE agreement (as it relates to youths’ CP) demonstrated a very similar pattern of results. Agreement of elevated child LPE between parents and teachers was, on average, predictive of the highest levels of CP. Focusing on the mother-teacher disagreement, a mother’s report of high levels of LPE together with a teacher reporting low levels of LPE was associated with an average level of child CP. Contrariwise, low mother-reported LPE and high teacher-reported LPE was predictive of youth having a similar level of CP compared to when both mothers and teachers reported elevated LPE. Our study demonstrates the predictive utility in the low/high agreement among sources of LPE as predictive of low/high levels of CP, respectively. Specific cases of disagreement (e.g., mother report > father report) also appear to provide similar levels of predictive utility as informant agreement (e.g., mother report = father report). It is feasible that the latter reflects individual differences among families in a child’s propensity to engage in LPE behavior with different authority figures. Such phenomenon would point to the value in not discounting any single informant’s report (e.g., relying only on mother reported LPE) but rather probing the nature of the discrepancies as potential leads on treatment (e.g., De Los Reyes et al., 2010). This interpretation is consistent with the recent needs-to-goals gap framework (De Los Reyes, Talbott, et al., 2022) which recommends professionals decide whether to ground their clinical decisions on a single or multiple informants based on whether service needs and/or goals manifest identically or differently (respectively) across domain-relevant contexts (e.g., home and school).

While speculative, our results may provide some support for the value of collecting father reported LPE. In terms of fathers’ and teachers’ reports of LPE, when fathers reported elevated child LPE – regardless of teacher’s report – youth tended to have the highest levels of conduct problems. Focusing on fathers reporting low LPE, however, at times of father-teacher disagreement where teachers report high LPE, youth tended to have meaningfully more CPs (when compared to agreement of low child LPE). The latter finding again potentially highlights the utility of collecting teacher reported LPE and interpreting it within the context of parent’s report.

As expected, when mothers and fathers agreed on low levels of LPE symptoms, youth tended to also be reported as having the lowest levels of CP. Similarly, when mothers and fathers agreed on high levels of LPE symptoms, children were reported as having the highest levels of CP. When parents had a discrepancy in their report of LPE, some interesting associations emerged. When mothers reported low LPE (and fathers reported high levels of LPE), as well as when mothers reported high LPE (and fathers reported low LPE), youth were reported to have a low level of CP symptoms – comparable to when both parents agreed on low-levels of LPE. Together, these findings may suggest that parent agreement on their child’s LPE severity is more likely to ‘translate’ to their level of CP. Put differently, parental agreement on high (or low) levels of LPE was predictive of the child also being more likely to have a high (or low) level of conduct problems, which is consistent with past research (De Los Reyes, Alfano, et al., 2016). Specifically, parental agreement of high adolescent mental health concerns (relative to dyads with low agreement) has been found to be associated with greater levels of hostility within caregiver–adolescent interactions (De Los Reyes, Alfano, et al., 2016). It is also important to note that the CP composite for these analyses was informed by both parents’ reports. While not mutually exclusive with the latter hypothesis, these findings could also, at least partially, reflect a common agreement between parents’ reports of both LPE and CP symptoms.

Related to our outcome composite, other similar approaches exist that warrant discussion. For instance, Kraemer and colleagues (2003) suggest a “mix-and-match” criterion where informants are selected based on whether they systematically vary in sources of variability; Similar to how the trait-score approach is only as useful when low correspondence among informants reflects systematic processes (Makol et al., 2020). The operations triad model (De Los Reyes et al., 2013; De Los Reyes, Wang, et al., 2022) can be applied to facilitate detecting when low convergence reflects meaningful information. We were not able to adopt the satellite approach (Kraemer et al., 2003) from an operations triad model framework (De Los Reyes et al., 2013) because there are, arguably, four combinations of perspective and context (parent-home, parent-school, teacher-home, teacher-school) in our study, and to use the satellite approach informants must conceptually cover at least three of these four combinations. This allows for a triangulation across informants to index trait, context, and perspective components of a multi-informant assessment. However, in our data mothers and fathers shared both context (i.e., home) and perspective (parent), resulting in coverage of just two of the four combinations (parent-home, teacher-school). Multiple informants who observe child LPE within different contexts and from different perspectives would benefit from future research that selects informants in a manner that meets the conditions laid out by Kraemer’s satellite approach (see De Los Reyes, Cook, et al., 2022).

These findings should be taken within the context of our study’s limitations. We utilized an outcome variable that was a composite of the two informants included in the model as predictors. This decision was made out of necessity; an outcome variable that was independent of parent and teacher reports (e.g., clinician ratings) would have been ideal but was not available. We decided against using a three-informant composite of CP traits (i.e., mother-, father-, and teacher-reported CP) in all of the models because this would have introduced a biased towards one environment (i.e., mother and father versus teacher). Further, this approach does introduce criterion contamination effects. As such, it is possible that the effects were driven, at least partially, by the same informants serving as the predictor and criterion (see De Los Reyes, Wang, et al., 2022). Recent work, however, does indicate that the Kraemer model framework (Kraemer et al., 2003) could potentially address this issue by integrating data across sources that vary by context (i.e. home and school; De Los Reyes, Cook, et al., 2022). In addition, our study relied on a single time-point, and given the cross-sectional nature, temporal sequencing cannot be inferred. The transversal design impedes any cause-effect relationships to be inferred as well. While differences in sample size among the models were inevitable (e.g., not receiving father/teacher-report), the father-teacher analyses sample was relatively small. Moreover, our sample was largely Caucasian; therefore, further replication is needed in a larger, more diverse sample of children in terms of both race and ethnicity.

We examined the relationship between mother-, father-, and teacher-reported LPE in a clinical sample of children. We found that the prevalence of child LPE was approximately twice as large when compared to those reported in community samples. Overall, mothers and fathers generally agreed on their child’s LPE symptoms (55% agreement) and as it relates to conduct problems. However, there were higher-order, non-linear interactions between mothers and fathers, as well as parents and teachers (i.e., mother-teacher and father-teacher). A similar pattern emerged across all three quadratic interactions; discrepancies between informants, characterized by low levels of LPE reported by the child’s mother (and high levels of LPE reported by the father or teacher), tended to predict youth to be at the highest risk for conduct problems. The findings of the current study may further emphasize the clinical utility of gathering multiple reports of LPE when serious conduct problems are suspected. It may be beneficial for clinicians to give significant consideration to teacher reported LPE when interpreting multiple informant reports of LPE, especially when disagreements about child LPE are observed between informants.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by T32 MH18268 and F32 MH124319 (PJC).

Footnotes

Ethical approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed consent: informed consent was waived due to the use of clinical records.

Conflict of Interest: On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Models were re-run with covariates, which did not affect the strength nor direction of the results.

Prior to our polynomial regression models, we first tested multicollinearity through the variance inflation factor; all variance inflation factors were < 2.0, indicating the assumption of limited multicollinearity was not violated.

References

- Achenbach TM, Krukowski RA, Dumenci L, & Ivanova MY (2005). Assessment of adult psychopathology: meta-analyses and implications of cross-informant correlations. Psychological Bulletin, 131(3), 361–382. 10.1037/0033-2909.131.3.361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, McConaughy SH, & Howell CT (1987). Child/adolescent behavioral and emotional problems: implications of cross-informant correlations for situational specificity. Psychological Bulletin, 101(2), 213–232. 10.1037/0033-2909.101.2.213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association, A., & Association, A. P. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (Vol. 10). Washington, DC: American psychiatric association. [Google Scholar]

- Bansal PS, Waschbusch DA, Haas SM, Babinski DE, King S, Andrade BF, & Willoughby MT (2019). Effects of intensive behavioral treatment for children with varying levels of conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits. Behavior Therapy, 50(1), 1–14. 10.1016/j.beth.2018.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barhight LR, Hubbard JA, Swift LE, & Konold TR (2017). A multitrait–multimethod approach to assessing childhood aggression and related constructs. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 63(3), 367–395. 10.13110/merrpalmquar1982.63.3.0367 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer DJ, Howard AL, Baldasaro RE, Curran PJ, Hussong AM, Chassin L, & Zucker RA (2013). A trifactor model for integrating ratings across multiple informants. Psychological Methods, 18(4), 475–493. 10.1037/a0032475 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner N, Foster S, Emery S, Berger G, Walitza S, & Häberling I (2021). How Are Discrepant Parent–Child Reports Integrated? A Case of Depressed Adolescents. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 31(4), 279–287. 10.1089/cap.2020.0116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers ME, Reider LB, Morales S, Buzzell GA, Miller N, Troller-Renfree SV, Pine DS, Henderson HA, & Fox NA (2020). Differences in parent and child report on the screen for child anxiety-related emotional disorders (SCARED): implications for investigations of social anxiety in adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 48(4), 561–571. 10.1007/s10802-019-00609-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle MH, & Pickles AR (1997). Influence of maternal depressive symptoms on ratings of childhood behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 25(5), 399–412. 10.1023/A:1025737124888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castagna, Babinski DE, Pearl AM, Waxmonsky JG, & Waschbusch DA (2020, Jun 4). Initial Investigation of the Psychometric Properties of the Limited Prosocial Emotions Questionnaire (LPEQ). Assessment, 1073191120927782. 10.1177/1073191120927782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castagna, Babinski DE, Waxmonsky JG, & Waschbusch DA (2021). The significance of limited prosocial emotions among externalizing disorders in children. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 1–12. 10.1007/s00787-020-01696-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castagna, Calamia M, & Davis TE (2019). The Discrepancy between Mother and Youth Reported Internalizing Symptoms Predicts Youth’s Negative Self-Esteem. Current Psychology, 1–10. 10.1007/s12144-019-00501-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castagna, Laird RD, Calamia M, & Davis TE (2020). A Basis for Comparison: The Congruence of Mother-Teacher Ratings of Externalizing Behavior as a Function of Family Size. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(12), 3335–3341. 10.1007/s10826-020-01843-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Castagna, & Waschbusch DA (2021). The importance of assessing impairment associated with limited prosocial emotions. Behavior Therapy, 52(5), 1237–1250. 10.1016/j.beth.2021.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chana SM, Tampke EC, & Fite PJ (2020). Discrepancies Between Teacher-and Child-Reports of Proactive and Reactive Aggression: Does Prosocial Behavior Matter? Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment(1), 70–83. 10.1007/s10862-020-09823-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell C, Nauta MH, Hudson JL, March S, Reardon T, Arendt K, Bodden D, Cobham VE, Donovan C, & Halldorsson B (2021). Research Review: Recommendations for reporting on treatment trials for child and adolescent anxiety disorders–an international consensus statement. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 62(3), 255–269. 10.1111/jcpp.13283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Georgeson A, Bauer DJ, & Hussong AM (2021). Psychometric models for scoring multiple reporter assessments: Applications to integrative data analysis in prevention science and beyond. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 45(1), 40–50. 10.1177/0165025419896620 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A (2011). Introduction to the special section: More than measurement error: Discovering meaning behind informant discrepancies in clinical assessments of children and adolescents. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 40(1), 1–9. 10.1080/15374416.2011.533405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Alfano CA, & Beidel DC (2010). The relations among measurements of informant discrepancies within a multisite trial of treatments for childhood social phobia. Journal Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(3), 395–404. 10.1007/s10802-009-9373-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Alfano CA, Lau S, Augenstein TM, & Borelli JL (2016, 2016/January/01). Can We Use Convergence Between Caregiver Reports of Adolescent Mental Health to Index Severity of Adolescent Mental Health Concerns? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(1), 109–123. 10.1007/s10826-015-0216-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Augenstein TM, Wang M, Thomas SA, Drabick DA, Burgers DE, & Rabinowitz J (2015). The validity of the multi-informant approach to assessing child and adolescent mental health. Psychological Bulletin, 141(4), 858–900. 10.1037/a0038498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Cook CR, Sullivan M, Morrell N, Wang M, Gresham FM, Hamlin C, Makol BA, Keeley LM, & Qasmieh N (2022). The Work and Social Adjustment Scale for Youth: Psychometric properties of the teacher version and evidence of contextual variability in psychosocial impairments. Psychological Assessment, 34(8), 777–790. 10.1037/pas0001139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Henry DB, Tolan PH, & Wakschlag LS (2009). Linking informant discrepancies to observed variations in young children's disruptive behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37(5), 637–652. 10.1007/s10802-009-9307-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, & Kazdin AE (2004). Measuring informant discrepancies in clinical child research. Psychological Assessment, 16(3), 330–334. 10.1037/1040-3590.16.3.330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Ohannessian CM, & Laird RD (2016). Developmental Changes in Discrepancies Between Adolescents' and Their Mothers' Views of Family Communication. Journal of Child Family Studies, 25(3), 790–797. 10.1007/s10826-015-0275-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Talbott E, Power TJ, Michel JJ, Cook CR, Racz SJ, & Fitzpatrick O (2022). The Needs-to-Goals Gap: How informant discrepancies in youth mental health assessments impact service delivery. Clinical Psychology Review, 92, 102114. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Thomas SA, Goodman KL, & Kundey SM (2013). Principles underlying the use of multiple informants' reports. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 123–149. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Los Reyes A, Wang M, Lerner MD, Makol BA, Fitzpatrick OM, & Weisz JR (2022). The Operations Triad Model and Youth Mental Health Assessments: Catalyzing a Paradigm Shift in Measurement Validation. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 1–36. 10.1080/15374416.2022.2111684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng J, Wang M-C, Zhang X, Shou Y, Gao Y, & Luo J (2019). The Inventory of Callous Unemotional Traits: A reliability generalization meta-analysis. Psychological Assessment, 31(6), 765–780. 10.1037/pas0000698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deros DE, Racz SJ, Lipton MF, Augenstein TM, Karp JN, Keeley LM, Qasmieh N, Grewe BI, Aldao A, & De Los Reyes A (2018). Multi-informant assessments of adolescent social anxiety: Adding clarity by leveraging reports from unfamiliar peer confederates. Behavior Therapy, 49(1), 84–98. 10.1016/j.beth.2017.05.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duhig AM, Renk K, Epstein MK, & Phares V (2000). Interparental agreement on internalizing, externalizing, and total behavior problems: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 7(4), 435–453. 10.1093/clipsy.7.4.435 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JR (1994). The study of congruence in organizational behavior research: Critique and a proposed alternative. Organizational behavior and Human Decision Processes, 58(1), 51–100. 10.1006/obhd.1994.1029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards JR, & Parry ME (1993). On the use of polynomial regression equations as an alternative to difference scores in organizational research. Academy of Management Journal, 36(6), 1577–1613. 10.5465/256822 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fite PJ, Poquiz J, Cooley JL, Stoppelbein L, Becker SP, Luebbe AM, & Greening L (2016). Risk factors associated with proactive and reactive aggression in a child psychiatric inpatient sample. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 38(1), 56–65. 10.1007/s10862-015-9503-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ford SH, & McCoy TP (2021). Minding the Gap: Adolescent and Parent/Caregiver Reporter Discrepancies on Symptom Presence, Impact of Covariates, and Clinical Implications. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 36(3), 225–230. 10.1016/j.pedhc.2021.09.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Ray JV, Thornton LC, & Kahn RE (2014). Can callous-unemotional traits enhance the understanding, diagnosis, and treatment of serious conduct problems in children and adolescents? A comprehensive review. Psychological Bulletin, 140(1), 1–57. 10.1037/a0033076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goolsby J, Rich BA, Hinnant B, Habayeb S, Berghorst L, De Los Reyes A, & Alvord MK (2018). Parent–child informant discrepancy is associated with poorer treatment outcome. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(4), 1228–1241. 10.1007/s10826-017-0946-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haas SM, Waschbusch DA, Pelham WE, King S, Andrade BF, & Carrey NJ (2011). Treatment response in CP/ADHD children with callous/unemotional traits. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 39(4), 541–552. 10.1007/s10802-010-9480-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton NJ, & Fitzmaurice GM (2004). Regression analysis of multiple source and multiple informant data from complex survey samples. Statistics in Medicine, 23(18), 2911–2933. 10.1002/sim.1879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Measelle JR, Ablow JC, Essex MJ, Boyce WT, & Kupfer DJ (2003). A new approach to integrating data from multiple informants in psychiatric assessment and research: mixing and matching contexts and perspectives. American Journal of Psychiatry, 160(9), 1566–1577. 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.9.1566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird RD, & De Los Reyes A (2013). Testing informant discrepancies as predictors of early adolescent psychopathology: Why difference scores cannot tell you what you want to know and how polynomial regression may. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(1), 1–14. 10.1007/s10802-012-9659-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird RD, & LaFleur LK (2016). Disclosure and monitoring as predictors of mother–adolescent agreement in reports of early adolescent rule-breaking behavior. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 45(2), 188–200. 10.1080/15374416.2014.963856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laird RD, & Weems CF (2011). The equivalence of regression models using difference scores and models using separate scores for each informant: implications for the study of informant discrepancies. Psychological assessment, 23(2), 388–397. 10.1037/a0021926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makol BA, Youngstrom EA, Racz SJ, Qasmieh N, Glenn LE, & De Los Reyes A (2020). Integrating multiple informants’ reports: How conceptual and measurement models may address long-standing problems in clinical decision-making. Clinical Psychological Science, 8(6), 953–970. 10.1177/2167702620924439 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Martel MM, Eng AG, Bansal PS, Smith TE, Elkins AR, & Goh PK (2021). Multiple informant average integration of ADHD symptom ratings predictive of concurrent and longitudinal impairment. Psychological Assessment, 33(5), 443–451. 10.1037/pas0000994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matlasz TM, Frick PJ, & Clark JE (2021). A Comparison of Parent, Teacher, and Youth Ratings on the Inventory of Callous–Unemotional Traits. Assessment, 10731911211047893. 10.1177/10731911211047893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A (2017). A biomarker of anxiety in children and adolescents: A review focusing on the error-related negativity (ERN) and anxiety across development. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 27, 58–68. 10.1016/j.dcn.2017.08.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A, Hajcak G, Torpey DC, Kujawa A, Kim J, Bufferd S, Carlson G, & Klein DN (2013). Increased error-related brain activity in six-year-old children with clinical anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(8), 1257–1266. 10.1007/s10802-013-9762-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A, Lerner MD, De Los Reyes A, Laird RD, & Hajcak G (2017). Considering ERP difference scores as individual difference measures: Issues with subtraction and alternative approaches. Psychophysiology, 54(1), 114–122. 10.1111/psyp.12664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Evans SW, Gnagy EM, & Greenslade KE (1992, 1992/June/01). Teacher Ratings of DSM-III-R Symptoms for the Disruptive Behavior Disorders: Prevalence, Factor Analyses, and Conditional Probabilities in a Special Education Sample. School Psychology Review, 21(2), 285–299. 10.1080/02796015.1992.12085615 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Gnagy EM, Greenslade KE, & Milich R (1992). Teacher ratings of DSM-III—R symptoms for the disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 31(2), 210–218. 10.1097/00004583-199203000-00006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renk K (2005). Cross-informant ratings of the behavior of children and adolescents: The “gold standard”. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 14(4), 457–468. 10.1007/s10826-005-7182-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saffer BY, Mikami AY, Qi H, Owens JS, & Normand S (2021). Factors Related to Agreement between Parent and Teacher Ratings of Children’s ADHD Symptoms: an Exploratory Study Using Polynomial Regression Analyses. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 43(4), 793–807. 10.1007/S10862-021-09892-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seijas R, Servera M, García-Banda G, Barry CT, & Burns GL (2018). Evaluation of a four-item DSM–5 Limited Prosocial Emotions specifier scale within and across settings with Spanish children. Psychological Assessment, 30(4), 474–485. 10.1037/pas0000496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seijas R, Servera M, García-Banda G, Leonard Burns G, Preszler J, Barry CT, Litson K, & Geiser C (2019). Consistency of limited prosocial emotions across occasions, sources, and settings: Trait-or state-like construct in a young community sample? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47(1), 47–58. 10.1007/s10802-018-0415-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shanock LR, Baran BE, Gentry WA, Pattison SC, & Heggestad ED (2010). Polynomial regression with response surface analysis: A powerful approach for examining moderation and overcoming limitations of difference scores. Journal of Business and Psychology, 25(4), 543–554. 10.1007/s10869-010-9183-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steiger JH (1980). Tests for comparing elements of a correlation matrix. Psychological Bulletin, 87(2), 245–251. 10.1037/0033-2909.87.2.245 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van der Ende J, Verhulst FC, & Tiemeier H (2020). Multitrait-multimethod analyses of change of internalizing and externalizing problems in adolescence: Predicting internalizing and externalizing DSM disorders in adulthood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 129(4), 343–354. 10.1037/abn0000510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Doorn M (2019). Conducting research in clinical practice: Challenges in the assessment and treatment of childhood internalizing disorders. [Google Scholar]

- Wang M-C, Shou Y, Liang J, Lai H, Zeng H, Chen L, & Gao Y (2020). Further validation of the inventory of callous–unemotional traits in Chinese children: Cross-informants invariance and longitudinal invariance. Assessment, 27(7), 1668–1680. 10.1177/1073191119845052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waschbusch DA, Willoughby MT, Haas SM, Ridenour T, Helseth S, Crum KI, Altszuler AR, Ross JM, Coles EK, & Pelham WE (2020). Effects of behavioral treatment modified to fit children with conduct problems and callous-unemotional (CU) traits. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 49(5), 639–650. 10.1080/15374416.2019.1614000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright KD, Waschbusch DA, & Frankland BW (2007). Combining data from parent ratings and parent interview when assessing ADHD. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 29(3), 141–148. 10.1007/s10862-006-9039-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]