Abstract

This study was designed to evaluate the oxidative damage, genotoxicity, and DNA damage in the liver of rats treated with titanium nanoparticles (TiO2-NPs) with an average size of 28.0 nm and ξ-potential of − 33.97 mV, and to estimate the protective role of holy basil essential oil nanoemulsion (HBEON). Six groups of Male Sprague–Dawley rats were treated orally for 3 weeks as follows: the control group, HBEO or HBEON-treated groups (5 mg/kg b.w), TiO2-NPs-treated group (50 mg/kg b.w), and the groups treated with TiO2-NPs plus HBEO or HBEON. Samples of blood and tissues were collected for different analyses. The results revealed that 55 compounds were identified in HBEO, and linalool and methyl chavicol were the major compounds (53.9%, 12.63%, respectively). HBEON were semi-round with the average size and ζ-potential of 120 ± 4.5 nm and − 28 ± 1.3 mV, respectively. TiO2-NP administration increased the serum biochemical indices, oxidative stress markers, serum cytokines, DNA fragmentation, and DNA breakages; decreased the antioxidant enzymes; and induced histological alterations in the liver. Co-administration of TiO2-NPs plus HBEO or HBEON improved all the tested parameters and the liver histology, and HBEON was more effective than HBEO. Therefore, HEBON is a promising candidate able to protect against oxidative damage, disturbances in biochemical markers, gene expression, DNA damage, and histological changes resulting from exposure to TiO2-NPs and may be applicable in the food and pharmaceutical sectors.

Keywords: Titanium dioxide nanoparticles, Oxidative damage, Genotoxicity, Basil essential oil, Nanoemulsions, Antioxidant

Introduction

Nanotechnology is the most important technology in the twenty-first century which has made tremendous breakthroughs in nanomaterials development for the advancement of biotechnology and medical research fields [1]. Titanium dioxide NPs (TiO2-NPs) are widely utilized in different applications owing to their high stability, anticorrosion, and photocatalytic characteristics [2, 3] such as nutraceuticals, pharmaceuticals, toothpaste, cosmetics, paper industries, paints production, and food products.

Several reports postulated that TiO2-NPs induce oxidative stress, cell apoptosis, DNA damage, and inflammatory reactions [4, 5]. The toxicity of TiO2-NPs is depending on the exposure conditions, the particle sizes, and the zeta potential [6]. Exposure to TiO2-NPs occurs by inhalation, ingestion, injections, or skin contact then accumulates in several organs and tissues by circulating blood [7, 8]. The International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) classified TiO2-NPs as group 2B (probably carcinogenic to humans) [5]. Recent studies indicated that TiO2-NPs induce severe toxicities to different organs such as the liver and the kidney after the absorption by the GIT [3, 9]. Several in vivo and in vitro researches indicated that TiO2-NPs have genotoxic properties, including inflammatory cytokines, chromosomal aberrations, gene mutations, gene mutations damage, and deletions in DNA in vitro [10, 11] and in vivo [12]. The toxicity of TiO2-NPs was mainly correlated with oxidative stress; therefore, adding nutrients that have antioxidants may be effective for the protection.

Essential oils (EOs) are secondary metabolites found in various aromatic and medicinal plants to protect the host plant from microorganisms [13, 14]. Holy basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) is an aromatic herb widely utilized in traditional medicine, and food flavoring. The main constitutes of the holy basil essential oil are terpenoid and phenolic compounds that are ascribed to the therapeutic properties [15, 16]. The basil oil inhibits cholesterol synthesis, enhances digestion, and acts as a chemo-preventive agent besides its pharmacological activities such as the antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and antimicrobial properties [16–23].

Due to their instability during exposure to light, temperature, oxygen, and pH [20, 24, 25], it was necessary to use encapsulation technology as a modern approach to solve the problems facing the use of EOs in various applications and protect them against chemical and thermal decomposition, increase their bioavailability and water solubility, construction of delivery, and controlling their release [6, 26, 27]. Therefore, this work was designed to determine the bioactive constituents in holy basil essential oil (HBEO), synthesize HBEO nanoemulsion (HBEON), and compare the pharmaceutical effect of HBEO and HBEON against the oxidative stress, genotoxicity, and DNA damage of TiO2-NPs in rats.

Materials and Methods

Materials

Whey protein isolate (WPI) and titanium tetra isopropoxide were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). TiO2-NPs (average size of 28.0 nm and ξ-potential of − 33.97 mV) were biosynthesized as described in our previous work [12] using Titanium tetra isopropoxide and orange peel extract (OPE). The resulting TiO2-NPs were dried overnight at 80 °C then were calcined at 600 °C for 4 h [28]. HBEO was provided by the Oil Extraction Unit, National Research Centre (NRC), Dokki, Cairo, Egypt, and was extracted using Clevenger-type apparatus.

Chemicals and Kits

Kits for Transaminases (ALT and AST), creatinine, urea, cholesterol (Chol), triglycerides (TriG), low- and high-density lipoprotein (LDL, HDL), total protein (TP), and albumin (Alb) were supplied by Randox Co, (Antrim, UK). Kits for nitric oxide (NO), malondialdehyde (MDA), glutathione peroxidase (GPx), catalase (CAT), and superoxide dismutase (SOD) were purchased from Eagle diagnostics (Dallas, TX, USA). Kits for carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) were provided by BiochemImmuno Systems Co. (Montreal, Canada). Kit for first-strand cDNA synthesis was obtained from iNtRON Biotechnology (Seoul, Korea). SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM kit was supplied by TaKaRa Biotech. Co. Ltd. (Shiga, Japan). TRIzol® reagent and RNAse-free DNAse kit were purchased from Invitrogen (Germany).

GC–MS Analysis of HBEO

The analysis of HEBO was conducted using a GC–MS (Hewlett-Packard model 5890) with a flame ionization detector (FID) and DB-5 fused silica capillary column (60 m × 0.32 mm) according to El-Nekeety et al. [29]. The retention indices (Kovats index) of the volatile compounds were calculated as described by Adams [30] using the hydrocarbons as reference (C7-C20, Aldrich Co.).

Synthesis of HBEON

WPI was used as the wall for the preparation of HBEON according to our previous report [6]. In brief, the WPI solution (10%) was prepared using distilled water, stirred for 1 h, and kept for 12 h at room temperature before emulsification. Tween 80 (80 mg) was used as an emulsifier, and the HBEO was added gradually at a ratio of 2:1 (w/w) with homogenization for 10 min at 20,000 rpm [31]; then, the emulsion was encapsulated by spray drying.

Characterization of HBEON

Scanning and transmission electron micrographs (TEM and SEM) were done using JEOL JAX-840A and JEOL JEM- 1230 electron micro-analyzers for HBEON. The acquisition of the image was done by Orius 1000 CCD camera (GATAN, Warrendale, PA, USA). HBEON sample was sonicated (30–60 min) immediately to prevent the coalescence of the nanoparticles before the assessment of zeta potential. The average diameter of the synthesized nanoparticles was calculated by zpw 388 version 2.14 nicomp software. However, the zeta potential and size distribution were done by a particle size analyzer (Nano-ZS, Malvern Instruments Ltd., UK).

Animals and Experimental Setup

Male Sprague–Dawley rats (3 months old, 155 ± 15 g) were provided by the Experimental Animal Facility, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Cairo University, Cairo, Egypt. The animals were housed individually in ventilated filter top polycarbonate cages in an artificially illuminated and thermally controlled room (12 h dark/light cycle, 25 ± 1 °C and 25–30% humidity) at the Animal House Lab, Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University, and were given ad libitum access to water and rodent chow diet. All animals were left for 1 week as an acclimatization period before starting the experiment, and all the procedures used in this experiment have complied with the guidelines of the National Institute of Health (NIH publication 86–23 revised 1985), and the protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University (REC-FOFCU), Egypt. Animals were distributed into 6 groups (10 rats/group) and treated daily by the oral gavage for 21 days as follows: (1) the untreated control group, (2) the HBEO-treated group (5 mg/kg bw), (3) HBEON-treated group (5 mg/kg b.w), (4) the animals that received TiO2-NPs (50 mg/kg b.w), and (5, 6) the animals that received TiO2-NPs plus HBEO or HBEON. After the last dose, animals have fasted for 12 h; then, samples of blood were withdrawn under isoflurane anesthesia through the retro-orbital venous plexus. The sera were harvested by cooling centrifuging (4 °C) at 3000 rpm for 10 min then kept at − 20 °C until the analysis. These sera were used for the assay of liver and kidney indices, lipid profile, and cytokines (TNF-α, CEA, and AFP) according to the kit’s instructions. Thereafter, all rats were euthanized; liver and kidney samples were weighed homogenized in a phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), and centrifuged (1700 rpm and 4 °C for 10 min). The supernatant was used for NO, MDA, SOD, CAT, and GPx assays [32]. Other liver samples were kept in liquid nitrogen − 80 °C for genetic analysis. However, other liver samples from each animal were fixed in formal saline (10%), dehydrated by a graded series of alcohol, cleaned in xylene, embedded in paraffin wax, and sliced at 5 μm thickness. The sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin stains for histopathological investigation using a light microscope [33].

Gene Expression Analysis

Total RNA IIsolation

The total genomic RNA in liver samples was isolated using TRIzol® reagent, and the RNA pellets were stored in DEPC-treated water. These pellets were treated with an RNAse-free DNAse kit to digest the potential DNA residues, and the RNA aliquots were stored at − 20 °C until use for the reverse transcription [34].

Reverse Transcription Reaction

A copy of cDNA from the liver tissues was synthesized using First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit via the reverse transcription reaction (RT). The program of RT reaction was 25 °C for 10 min, 1 h at 42 °C then 5 min at 95 °C, and was applied to obtain the cDNA copy of the hepatic genome. The tubes of a reaction containing the cDNA copy were then collected on ice for cDNA amplification [34].

Quantitative RT-PCR

SYBR® Premix Ex TaqTM kit was utilized to assay the qRT-PCR analyses for the synthesized cDNA copies of hepatic tissue, and the melting curve profile was performed for each reaction. The specific primers were selected according to the published sequences of Gen Bank. Sequences of caspase-3, Bax, Bcl-2, TNF-α, P53, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) primers, and the annealing temperature used for RT-PCR are shown in Table 1. The housekeeping gene expression was utilized to normalize the quantitative values of the target genes. The 2 − ΔΔCT method was applied for the determination of the quantitative values of the specific genes to GAPDH, and the relative quantification of the target gene to the reference was calculated using the following equations:

Table 1.

Primer sequences used for real-time PCR

| Gene | Nucleotide sequence 5′–3′ | Accession no | Product size (bp) | Annealing (°C) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bax |

AGGATGATTGCTGATGTGGATAC CACAAAGATGGTCACTGTCTGC |

NM_017059.2 | 300 | 60 | [110] |

| Caspase-3 |

AAATTCAAGGGACGGGTCAT ATTGACACAATACACGGGATCTGT |

NM_012922.2 | 652 | 55 | [111] |

| Bcl-2 |

GCTACGAGTGGGATACTGGAGA AGTCATCCACAGAGCGATGTT |

NM_016993.2 | 446 | 60 | [112] |

| P53 |

GCACAAACACGCACCTCAAAGC CTTGCATTCTGGGACAGCCAAG |

NM_030989.3 | 489 bp | 58 | [113] |

| GAPDH |

CAAGGTCATCCATGACAACTTTG GTCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTAG |

NM_017008.4 | 496 bp | 58 | [50] |

DNA Fragmentation Assay

DNA fragmentation was determined to evaluate apoptosis following the procedure of Perandones et al. [35]. In brief, 10–20 mg of hepatic tissue were ground in 400-μl hypotonic lysis buffer (1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris base, and 0.2% Triton X-100), then centrifuged at 10,000 rpm and 4 °C for 15 min. The supernatant of each sample was divided into two halves, the first was used for gel electrophoresis, and the second was used together with the pellets for the quantification of fragmented DNA by the diphenylamine. The blue color was developed and quantified at 578 nm, and the DNA fragmentation percentage in the sample was calculated using the formula (1):

| 1 |

Single-Cell Gel Electrophoresis (comet) Assay

The comet assay was done as described in detail by Fahmy et al. [36]. A total of 50 cells were analyzed per animal using automatic comet score™ software (TriTek Corp, version 2.0.0.0, Sumerduck, VA 22,742, USA). Tail DNA percentage (% Tail DNA) and Olive tail moment (OTM) were used as indicators for DNA damage and were expressed in arbitrary units (A.U).

Statistical Analysis

All data were statistically analyzed using computerized software SPSS (Statistical Package of Social Science, version 20, Armonk, New York: IBM Corp). The one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Duncan’s multiple comparisons test was applied to measure the degree of significance at p < 0.05.

Results

The GC–MS analysis showed the identification of 55 compounds in HBEO represented 98.8% of the oil and the majority belongs to terpene, phenylpropanoids, sesquiterpenoids, and terpene alcohol (Table 2). Five major compounds represented 76.9% including linalool, methyl chavicol, γ-muurolene, β-elemene, and aciphyllene, and were found in concentrations of 53.9, 12.63, 3.7, 3.47, and 3.2%, respectively. However, the other fifty compounds were found in concentrations of less than 2%. The SEM and TEM image of HBEON showed a semi-rounded shape particles (Fig. 1A and B) with an average size of 120 ± 4.5 nm (Fig. 1C) and − 28 ± 1.3 mV zeta potential (Fig. 1D).

Table 2.

GC/MS analysis of the composition of basil essential oila

| No | Compound nameb | RT | Composition, % |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Santolina triene | 10.44 | 1.4 |

| 2 | α-pinene | 10.56 | 0.2 |

| 3 | Camphene | 10.62 | 0.2 |

| 4 | Sabinene | 10.85 | 0.1 |

| 5 | β-Pinene | 11.32 | 0.2 |

| 6 | Myrcene | 11.86 | 0.4 |

| 7 | o-Cymene | 12.86 | 0.1 |

| 8 | Limonene | 13.29 | 0.2 |

| 9 | 1,8-Cineole | 13.52 | 0.8 |

| 10 | (Z)-β-Ocimene | 13.77 | 0.1 |

| 11 | (E)-β-Ocimene | 14.04 | 1.7 |

| 12 | cis-Sabinene hydrate | 14.67 | 0.2 |

| 13 | cis-Linalool oxide | 15.02 | 0.1 |

| 14 | Terpinolene | 15.23 | 0.1 |

| 15 | Linalool | 16.03 | 53.9 |

| 16 | Camphor | 16.84 | 0.4 |

| 17 | Menthone | 17.63 | 0.4 |

| 18 | iso-Menthone | 18.32 | 0.2 |

| 19 | Menthol | 18.67 | 1.3 |

| 20 | Terpinen-4-ol | 18.88 | 0.1 |

| 21 | α-Terpineol | 19.29 | 0.1 |

| 22 | Methyl chavicol | 19.74 | 12.63 |

| 23 | Geraniol | 20.21 | 1.1 |

| 24 | Geranial | 21.84 | 0.1 |

| 25 | Bornyl acetate | 22.39 | 0.2 |

| 26 | Menthyl acetate | 22.69 | 0.1 |

| 27 | δ-Elemene | 23.95 | 0.2 |

| 28 | α-Cubebene | 24.52 | 0.1 |

| 29 | Eugenol | 25.34 | 0.1 |

| 30 | α-Copaene | 25.56 | 0.4 |

| 31 | Geranyl acetate | 25.84 | 0.1 |

| 32 | β-Elemene | 26.14 | 3.47 |

| 33 | α-Cedrene | 26.56 | 0.1 |

| 34 | (E)-Caryophyllene | 26.97 | 0.7 |

| 35 | β-Gurjunene | 27.09 | 0.1 |

| 36 | α-trans-Bergamotene | 27.22 | 0.7 |

| 37 | α-Guaiene | 27.39 | 1.8 |

| 38 | cis-Muurola-3,5-diene | 27.74 | 0.1 |

| 39 | α-Humulene | 27.96 | 0.6 |

| 40 | cis-Cadina-1(6),4-diene | 28.12 | 0.5 |

| 41 | β-Acoradiene | 28.33 | 0.1 |

| 42 | γ-Muurolene | 28.81 | 3.7 |

| 43 | β-Selinene | 28.94 | 0.4 |

| 44 | Aciphyllene | 29.31 | 1.2 |

| 45 | Aciphyllene | 29.61 | 3.2 |

| 46 | γ-Cadinene | 29.83 | 1.7 |

| 47 | δ-Cadinene | 29.91 | 0.4 |

| 48 | trans-Cadina-1,4-diene | 30.19 | 0.1 |

| 49 | α-Cadinene | 30.48 | 0.1 |

| 50 | (E)-Nerolidol | 30.96 | 0.1 |

| 51 | Spathulenol | 31.58 | 0.1 |

| 52 | 1,10-di-epi-Cubenol | 32.58 | 0.4 |

| 53 | epi-α-Cadinol | 33.51 | 1.9 |

| 54 | β-Eudesmol | 33.71 | 0.1 |

| 55 | Total identified (%) | 98.8 |

aCompound identified by GC/MS and/or by comparison of MS and LRI of standard compounds (ST) under the same conditions

bThe compounds are listed according to their concentration order. Linear retention index relative to n-alkanes (C7-C20) on DB-5 column

Fig. 1.

A TEM image of HBEON, B SEM image of HBEON, C DLS analysis showing the size distribution of HBEON, and D ZetaSizer chromatogram showing the zeta potential of HBEON

The biochemical assays indicated that TiO2-NPs disturb the hepatic and renal functions (Table 3) as evidenced by the remarkable elevation (p < 0.05) of the transaminase (AST, ALT), D.BIL, T.BIL, urea, uric acid, and creatinine, and the remarkable decrease (p < 0.05) in Alb and TP. Animals that received HBEO were comparable to the untreated control in all the biochemical markers of the liver and kidney except uric acid which was below the control value. However, rats treated with HBEON showed a notable decrease (p < 0.05) in transaminases (ALT, AST) and creatinine and a remarkable increase (p < 0.05) in Alb and TP with no effects on the other parameters. The combined treatment with TiO2-NPs and HBEO or HBEON induced a worthy improvement in the liver and kidney indices, and HBEON was more effective than HBEO to restore most of these markers to the control levels.

Table 3.

Effect of HBEO and HBEON on serum biochemical parameters in rats treated with TiO2-NPs

| Groups parameter | Control | HBEO | HBEON | TiO2-NPs | TiO2-NPs + HBEO | TiO2-NPs + HBEON |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALT (U/L) | 44.23 ± 1.06a | 44.58 ± 0.56a | 42.93 ± 1.03b | 86.41 ± 2.27c | 62.19 ± 1.81d | 52.37 ± 0.43e |

| AST (U/L) | 145.11 ± 1.38a | 145.38 ± 0.71a | 139.17 ± 2.86b | 204.51 ± 2.38c | 159.96 ± 1.51d | 159.71 ± 1.06d |

| Alb (g/dl) | 2.84 ± 0.03a | 2.55 ± 0.10b | 2.88 ± 0.04a | 1.14 ± 0.03c | 2.21 ± 0.07d | 2.03 ± 0.05e |

| TP (g/dl) | 6.26 ± 0.18a | 6.26 ± 0.10a | 6.82 ± 0.05b | 5.22 ± 0.24c | 5.46 ± 0.09d | 6.09 ± 0.08a |

| T.BIL (g/dl) | 0.89 ± 0.02a | 0.83 ± 0.02a | 0.80 ± 0.02a | 1.54 ± 0.21a | 1.13 ± 0.02a | 0.95 ± 0.04a |

| D.BIL (g/dl) | 0.19 ± 0.02a | 0.21 ± 0.01a | 0.22 ± 0.01a | 0.38 ± 0.02c | 0.30 ± 0.01d | 0.28 ± 0.02d |

| Creatinine (g/dl) | 1.14 ± 0.03a | 0.85 ± 0.04ab | 0.86 ± 0.03b | 2.52 ± 0.11c | 1.94 ± 0.02d | 1.81 ± 0.04e |

| Uric acid (mg/dl) | 2.26 ± 0.21a | 1.46 ± 0.07b | 1.46 ± 0.06b | 4.17 ± 0.24c | 2.59 ± 0.09d | 2.47 ± 0.10e |

| Urea (mg/dl) | 56.21 ± 1.38a | 53.44 ± 0.41a | 52.31 ± 0.43a | 81.32 ± 1.51b | 70.32 ± 0.78c | 59.85 ± 0.57d |

Within each column, means superscript with different letters are significantly different (p < 005)

TiO2-NPs also disturbed the lipid profile (Table 4) as a manifestation of the remarkable increase (P < 0.05) in TriG, Chol, and LDL and the decrease in HDL. Administration of HBEO alone decreased Chol, TriG, and LDL but did not affect HDL. However, administration of HBEON decreased Chol and TriG but did not affect LDL or HDL. Co-administration of TiO2-NPs plus HBEO normalized Chol and improved significantly (P < 0.05) TriG, LDL, and HDL compared to TiO2-NPs. More improvement in these indices towards the control values was observed in the group that received HBEON plus TiO2-NPs (Table 4).

Table 4.

Effect of HBEO and HEBEON on serum lipid profile in rats treated with TiO2-NPs

| Parameter Groups | Chol (mg/dl) | TriG (mg/dl) | LDL (mg/dl) | HDL (mg/dl) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 68.44 ± 1.24a | 87.41 ± 2.66a | 35.24 ± 1.38a | 33.46 ± 2.51a |

| HBEO | 64.61 ± 0.93b | 81.32 ± 1.12b | 32.69 ± 0.70b | 34.63 ± 0.41a |

| HEBEON | 63.22 ± 1.02b | 79.58 ± 0.45c | 34.25 ± 0.61a | 35.49 ± 0.52a |

| TiO2-NPs | 87.68 ± 2.52c | 124.42 ± 2.58d | 66.57 ± 2.47c | 22.52 ± 1.27b |

| TiO2-NPs + HBEO | 69.94 ± 0.52a | 102.10 ± 1.02e | 52.15 ± 0.75d | 26.17 ± 0.86c |

| TiO2-NPs + HEBEON | 60.82 ± 0.86d | 101.81 ± 1.01e | 49.30 ± 0.75e | 26.67 ± 0.48c |

Within each column, means superscript with different letters are significantly different (p <0.05)

The effect of TiO2-NPs alone or plus HBEO or HBEON on serum cytokines (Fig. 2) indicated that TiO2-NPs induced a marked elevation (p < 0.05) in AFP, CEA, and TNF-α. Administration of HBEO or HBEON induced a marked reduction (p < 0.05) in TNF-α but did not affect AFP or CEA. Both HBEO and HBEON induced a considerable improvement (p < 0.05) in the tested cytokines in the animal that received the combined treatment with TiO2-NPs towards the normal control level although their values were still higher compared with the untreated control rats.

Fig. 2.

Effect of HBEO and HEBEON on serum AFP (A), CEA (B), and TNF-α (C) in rats treated with TiO2-NPs. Superscripts with different letters in each column are significantly different at p < 0.05

The current results also indicated that TiO2-NPs increased hepatic and renal NO levels compared with those in the untreated control group (Fig. 3A). HBEO and HBEON decreased the renal NO but did not induce a marked effect on its hepatic level. Co-administration of TiO2-NPs plus HBEO or HBEON significantly improved (P < 0.05) NO in both organs, and HBEON was more effective compared to HBEO. Additionally, TiO2-NPs also increased the hepatic and renal MDA compared with those in the negative control group (Fig. 3B). HBEO and HBEON decreased significantly (p < 0.05) the hepatic MDA but did not cause any marked changes in renal MDA level. The combined treatment with TiO2-NPs plus HBEO or HBEON improved significantly (p < 0.05) MDA in both liver and kidney, although it was still higher than the level of control in both organs.

Fig. 3.

Effect of HBEO and HBEON on hepatic and renal NO (A) and MDA (B). Superscripts with different letters in each column (small letters for liver and capital letters for kidney) are significantly different at p < 0.05

The data listed in Table 5 showed that TiO2-NPs significantly (p < 0.05) reduced the hepatic and renal antioxidant enzymes activity. HBEO alone increased the activity of hepatic and renal GPx and renal CAT but no significant (P < 0.05) effect was noticed in hepatic CAT or SOD in these organs. Co-treatment with TiO2-NPs plus HBEO or HBEON improved these antioxidant enzymes in both organs, and HBEON was more effective than HBEO.

Table 5.

Effect of HBEO and HBEON on hepatic and renal antioxidant enzymes in rats treated with TiO2-NPs

| Parameter groups | GPx (U/g) | CAT (mU/g) | SOD (U/g) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liver | Kidney | Liver | Kidney | Liver | Kidney | |

| Control | 36.45 ± 1.07a | 31.30 ± 0.98a | 6.56 ± 0.08a | 7.88 ± 0.15a | 28.14 ± 0.65aa | 28.19 ± 0.50a |

| HBEO | 39.49 ± 2.24b | 33.49 ± 1.13b | 7.02 ± 0.10a | 8.05 ± 0.08b | 29.89 ± 0.77a | 29.93 ± 0.42a |

| HEBEON | 41.25 ± 2.51b | 35.63 ± 0.45c | 7.16 ± 0.05a | 9.22 ± 0.26c | 29.87 ± 0.49a | 28.43 ± 1.04a |

| TiO2-NPs | 21.43 ± 0.55c | 12.02 ± 0.57d | 2.87 ± 0.15b | 3.46 ± 0.15d | 14.24 ± 0.15b | 15.02 ± 0.25b |

| TiO2-NPs + HBEO | 27.41 ± 0.78d | 17.38 ± 0.24e | 4.33 ± 0.09c | 5.31 ± 0.05e | 17.73 ± 0.34c | 18.86 ± 0.34c |

| TiO2-NPs + HBEON | 30.82 ± 0.46f | 23.68 ± 0.54f | 5.01 ± 0.07d | 5.54 ± 0.08e | 21.45 ± 0.54d | 20.73 ± 0.27d |

Within each column, means superscript with different letters are significantly different (p<0.05)

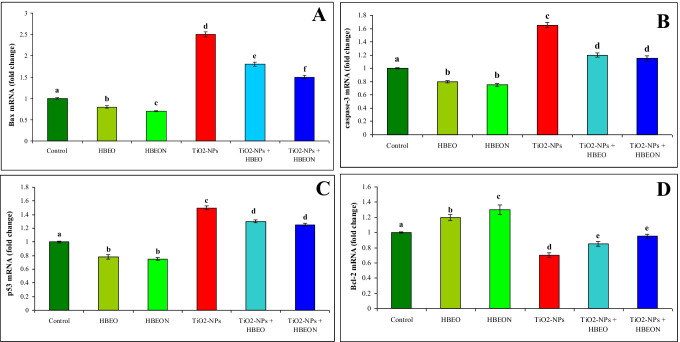

The mechanisms of prevention of HBEO and HBEON against hepatic apoptosis induced by TiO2-NPs were further evaluated in this study. Pro-apoptotic gene Bax and anti-apoptotic gene Bcl-2 were examined using qRT-PCR. Administration of HBEO or HBEON alone decreased the mRNA expression of Bax (Fig. 4A), caspase-3 (Fig. 4B), and P53 (Fig. 4C); however, these treatments increased the expression of Bcl-2 mRNA (Fig. 4D). TiO2-NPs upregulated the mRNA expression Bax (2.5-fold increase), caspase-3 (1.65-fold increase), and p53 (1.5-fold increase) and downregulated the expression of Bcl-2 mRNA (0.7-fold decrease) compared with the untreated control group. Co-treatment with TiO2-NPs plus HBEO or HBEON improved mRNA expression of these genes, and this improvement was more noticeable in the group that received HBEON. The relative values were a 1.4- and 1.6-fold decrease for Bax, a 1.4- and 1.43-fold decrease for caspase-3, and a 1.1- and 1.2-fold decrease for p53; however, the relative value for Bcl-2 was 1.2- and 1.4-fold increase in the groups received TiO2-NPs plus HBEO or HBEON, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Effect of HBEO and HBEON on relative expression of Bax (A), caspase-3 (B), and p53 (C) and Bcl-2 gene in liver of rats treated with TiO2-NPs. Analyses were performed in triplicate. Data are the mean ± SE of three different liver samples in same group. Superscripts with different letters in each column are significantly different at p < 0.05

The current results showed that the percentage of DNA fragmentation in the hepatic tissue of TiO2-NP-treated rats was significantly increased (p< 0.05) in comparison with the negative control group. Administration of HBEO or HBEON decreased significantly DNA fragmentation percent, and this decrease was apparent in the group that received HBEON. On the other hand, co-administration with TiO2-NPs plus HBEO or HBEON showed a remarkable decrease in DNA fragmentation percent and HBEON was more effective than HBEO (Fig. 5A, B).

Fig. 5.

Effect of HBEO or HBEON alone or in combination with TiO2-NPs on hepatic A DNA fragmentation percentage and B DNA fragmentation analysis: 1.5% of agarose gel electrophoresis of DNA samples extracted from liver tissues of different groups. Lane M: 100 bp size marker, Lane 1: control group, Lane 2: HBEO, Lane 3: HBEON, Lane 4: TiO2-NPs, Lane 5: TiO2-NPs plus HBEO, and Lane 6: TiO2-NPs plus HBEON

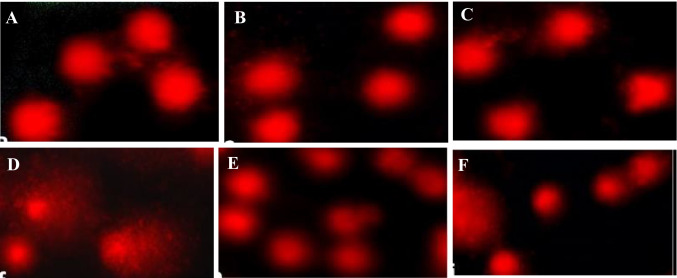

The data in Table 6 and Fig. 6 showed the effect of different treatments on the level of DNA breakages in the liver using the comet assay. Treatment with HBEO or HBEON alone did not increase the percentage of tail DNA in rat liver (9.83% and 9.75% for HBEO and HBEON, respectively, versus 9.77% for control). Further, the OTM values did not change significantly (p > 0.05) in the groups treated with HBEO or HBEON (1.13 and 1.12 A. U, respectively) compared to the normal control value (1.12 A.U). Treatment with TiO2-NPs increased tail DNA percentage (18.74%) and OTM (3.57 A. U) compared with the normal control values (1.12 A. U). Additionally, co-administration of HEBO or HBEON plus TiO2-NPs induce a significant decrease in tail DNA percentage and OTM compared to TiO2-NPs alone-treated group and this reduction was more noticeable in the group treated with TiO2-NPs plus HBEON than that in TiO2NPs plus HEBO-treated group.

Table 6.

Inhibitory activity of HBEO and HBEON on DNA damage induced by TiO2-NPs in rat liver using comet assay (mean ± S.E)

| Treatment groups | % Tail DNA | OTM (A.U) |

|---|---|---|

| Control | 9.77 ± 1.24a | 1.12 ± 0.02a |

| HBEO | 9.83 ± 0.08a | 1.13 ± 0.02a |

| HEBEON | 9.75 ± 0.53a | 1.12 ± 0.06a |

| TiO2-NPs | 18.74 ± 1.77b | 3.57 ± 0.14b |

| TiO2-NPs + HBEO | 12.40 ± 0.27c | 1.55 ± 0.03c |

| TiO2-NPs + HBEON | 11.23 ± 0.37d | 1.12 ± 0.11a |

The values superscript with different letters in each column are significantly different from one another as calculated by ANOVA (P < 0.05)

Fig. 6.

Alkaline comet assay for DNA damage in liver of A control rats, B HBEO-treated rats, C HBEON-treated rats, D TiO2-NP-treated rats, E TiO2-NPs + HBEO-treated rats, and F TiO2-NPs + HBEON-treated rats (original magnification 400 ×)

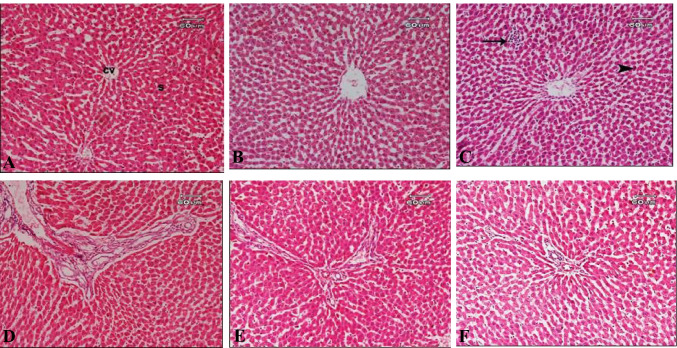

The histological examination of the control liver sections showed the normal structure of the hepatic lobule, central vein, and blood sinusoid (Fig. 7A). The sections of the liver from animals that received HBEO revealed normal hepatic structure, although some nuclei appear small in size and some of them showed signs of degeneration such as necrosis, karyolysis, and pyknosis (Fig. 7B). The liver sections of the rats that were treated with HBEON showed normal structure, while nodules of aggregation of inflammatory cells and signs of nuclear degeneration in the form of necrosis, pyknosis, and karyolysis were noted (Fig. 7C). The liver sections of rats that were treated with TiO2-NPs showed marked dilatation of the portal tract, the proliferation of bile ducts, necrosis in their epithelial cells, and fibrosis (formation of fibrous septa) could be also observed (Fig. 7D). Liver sections of rats that received TiO2-NPs plus HBEO showed some improvement represented in reduction of fibrous tissue, mild cellular infiltration around the dilated portal area, and mildly dilated bile duct; however, signs of degeneration in the form of pyknosis, karyolysis, and necrosis, as well as vacuolar degeneration, were still present (Fig. 7E). On the other hand, animals that were treated with TiO2-NPs plus HBEON showed improvement in the pathological alterations in the form of diminution in fibrosis, weak dilation in the portal tract, minute cytoplasmic vacuoles, mild cellular infiltration, and hypertrophied of Kupffer cells (Fig. 7F).

Fig. 7.

Photomicrograph of the liver sections of A control rats showing normal structure of hepatic lobule, central vain (cv), and blood sinusoid (s); B rats treated with HBEO showing normal hepatic structure; C rats treated with HBEON showing the normal structure of hepatic tissue while, nodule of aggregation of inflammatory cells (arrow) were noted, sings of nuclear degeneration in the form of necrosis, pyknosis (arrow head), and karyolysis were noted; D rats treated with TiO2-NPs showing marked dilatation of the portal tract, proliferation of the bile ducts and necrosis in their epithelial cells, and fibrosis (formation of fibrous septa) could be observed; E rats treated with TiO2-NPs plus HBEO showing some improvement represented in minimal fibrous tissue and little diffusion of inflammatory cell infiltration; and F rats treated with TiO2-NPs plus HBEON showing improvement in pathological changes in the form of diminution in fibrosis, and weak dilation in portal tract, mild cellular infiltration and hypertrophied of kupffer cell

Discussion

In this study, the GC–MS identified 55 compounds in HBEO that constituted 98.8% of the oil and belong to terpene, phenylpropanoids, sesquiterpenoids, and terpene alcohol. The major identified compounds were linalool and methyl chavicol followed by γ-muurolene, β-elemene, and aciphyllene. Previous studies reported that linalool was the major compound identified in HBEO [37, 38]; however, other studies reported that methyl eugenol was the major compound followed by methyl chavicol [39], and others showed that methyl chavicol followed by linalool [40]. In this concern, Ahmed et al. [41] and Diniz do Nascimento et al. [42] suggested that the chemical compounds of the oils differ according to several factors including the plant variety, agriculture practices, and geographical origin. The HOBEN was synthesized successfully by incorporating WPI, and the resulted emulsion showed a smooth and semi-round shape with an average size and a ζ-potential of 120 nm and − 28 mV, respectively. These results suggested that WPI increased the coalescence of the droplets [43], and also, the smooth shape and the uniform size distribution confirmed that WPI acted as a wall material for the oil droplets [44, 45]. Roger et al. [46] indicated that the particles’ size and the properties of their surface have a vital role in the uptake of the nanoparticles by the cells and the favorable size is 50–300 nm compared with the other sizes, although the size < than 100 nm showed unique and novel functional properties. Moreover, these authors reported that size has a vital role in the distribution, pharmacokinetics, and clearance of nanoparticles. Additionally, ζ-potential also has a critical effect on the distribution and stability of the droplets [47]. In our study, the negative ζ-potential of HBEON is ascribed to the negative charge of the carboxylate group as it is the functional charge of the WPI globule [44].

The in vivo study was performed to estimate the protective role of HBEON compared to HBEO against TiO2-NP-induced oxidative damage and genotoxicity in rats. The doses of TiO2-NPs and the oils were selected based on our previous reports [6,29, respectively]. Administration of TiO2-NPs displayed severe disturbances in the biochemical indices, the oxidant/antioxidant parameters, serum cytokines, gene expression, DNA damage, and the histological construction of the hepatic tissues. The increase of AST and ALT in the TiO2-NPs-treated group indicated that these nanoparticles induced injury and damage to the hepatocytes resulting in the release of these enzymes into the circulation [48, 49], and the decrease in Alb and TP in this group also confirmed the hepatic damage and/or the kidney dysfunction [50]. Additionally, the increase in creatinine, uric acid, and urea indicated nephrotoxicity and glomerular injury [51, 52]. The increase in Chol, TriG, and LDL and the decrease in HDL after TiO2-NP administration indicated that these nanoparticles disturbed the lipid metabolism possibly through the alteration of lipoprotein lipase or the capability of removing or transferring the fractions of lipids [6, 53]. It is known that the elevation in TriG and Chol levels are correlated with some metabolic syndromes and cardiovascular diseases; hence, these results suggest that TiO2 could aggravate cardiovascular diseases [54–56].

It was documented that TiO2-NPs induce oxidative damage and disturb the balance between oxidant/antioxidant (redox balance) in the body [12, 55, 57]. This fact confirms the present results as the animals in the TiO2-NPs group exhibited a significant elevation in MDA, NO, and the inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, AFP, and CEA) besides a decrease in the activity of the antioxidant enzymes (GPx, SOD, and CAT). Therefore, TiO2-NPs enhance ROS generation [57] which injures the macromolecules mainly DNA, carbohydrates, proteins, and lipids [6, 50]. In addition, ROS increases the peroxidation of lipids and disturbs the cell membrane structure and the pivotal function of the cells [58]. The generation of hydroxyl radicals (•OH) is the main factor in the oxidative damage induced by TiO2-NPs [59], and the accumulation of MDA besides the decrease in antioxidant enzymes may lead to the apoptosis of cells [6, 12]. Furthermore, Nrf2 as the principal regulator for different antioxidant gene expressions is increased during the overproduction of ROS which resulted in further damage to DNA and enhances the risk of cancer [60]. Moreover, when SOD decrease, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) accumulates in the liver and kidney leading to the inhibition of CAT [61], the enzyme responsible for the converting of H2O2 to H2O and O2, and hence, it prevents oxidative damage to these organs [62].

TiO2-NP administration disturbs the gene expression of Bax, caspase-3, p53, and Bcl-2. Animals in this group exhibited a significant upregulation of Bax, caspase-3, and p53 mRNA expression and a significant downregulation of Bcl-2. These results along with the disturbances in cytokines and immune function indicated that the generation of ROS after TiO2-NP exposure activates several receptors resulting in the activation of signaling pathways to decrease the antioxidant via ROS formation [3]. The exposure to excess ROS reduced the mitochondrial membrane potential leading to apoptotic cell death and immunotoxicity through the imbalance of immune redox [3, 5, 63]. Moreover, Bcl-2 is a protein located on the mitochondrial surface to prevent cytochrome c release, but Bax induces punching of the mitochondrial membrane holes to prevent the leaking out of cytochrome c [64, 65], hence, the imbalance between Bcl-2 and Bax activate caspase-dependent apoptotic pathway [66]. Additionally, the increase in Bax mRNA expression may counteract the action of p53 on apoptosis [67]. Animals that received TiO2-NPs also showed an increase in the DNA fragmentation percentage in the hepatic tissue which confirms the generation of hydroxyl radical, the major destructive species that enhance DNA damage [59].

The comet assay showed that TiO2-NPs increased comet tail formation in the hepatic cells and suggesting that these particles induced single- or double-strand breaks, dysregulation of the cell cycle checkpoints, and DNA-adduct formation [68, 69]. Two main mechanisms were suggested for these consequences as the primary and secondary genotoxicities in the absence and presence of inflammation [70]. According to Jin et al. [71], genotoxicity takes place when TiO2-NPs react directly with the DNA molecules or indirectly react with the nuclear proteins. The primary genotoxicity occurred owing to ROS generation and the releasing of the toxic metal ions from the soluble TiO2-NPs. On the other hand, secondary genotoxicity occurs through the immune cells which can generate excess ROS and stimulate the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, thus attacking DNA molecules [72, 73]. Additionally, TiO2-NPs stimulate sister chromatid exchange, micronuclei formation, and comet tail in the lymphocytes of peripheral blood in humans [10, 74]. In this concern, Sycheva et al. [75] reported that TiO2-NP administration induced the comet tail formation in the liver and bone marrow of mice; meanwhile, the intra-peritoneal injection produces DNA break and DNA adducts [76] as well as increases the cell micronuclei in bone marrow [77].

The histological study revealed that TiO2-NP administration induced a marked dilatation of the portal tract, a proliferation of bile ducts and necrosis in their epithelial cells, and fibrosis. These pathological changes were similar to those reported in previous research [6, 78, 79] which showed that treatment with TiO2-NPs affects the histological structure of the liver via oxidative damage which was more localized around the central vein. Pialoux et al. [80] suggested a strong linkage between tissue anoxia and oxidative damage in several organs. Additionally, Kupffer cells in the liver are the most impacted cells by oxidative damage due to their location nearby the portal area in the liver tissue [81].

It is clear now that the toxicity of TiO2-NPs is particularly due to the excess ROS generation leading to oxidative damage. Hence, antioxidant supplementation probably is valuable in the protection against this oxidative damage. HBEO is known as an affluent source of many bioactive compounds which possess a potent antioxidant. The high level of linalool and methyl chavicol gives this essential oil the advantage to protect against oxidative DNA damage [82, 83]. Moreover, the emulsifying technology manages the controlled release of the bioactive constituents and enhances their bioavailability and stability [50]. In the current study, we evaluated the potential protective role of HBEON compared with HBEO in animals treated with TiO2-NPs. Administration of HBEO or HBEON induced positive effects on most of the tested parameters and did not induce any toxic effects. Moreover, both agents induced remarkable improvement in the liver and kidney indices, lipid profile, serum cytokines, and oxidant/antioxidant indices in rats that received TiO2-NPs which is due to the potent antioxidant activity of linalool [41, 84], and the pro-oxidant activity which prevents DNA damage and suppression of ROS generation [85]. The previous studies reported that linalool diminishes TNF-α and IL-6 and prevents IkBa protein phosphorylation, p38, c-Jun terminal kinase, and the extracellular signal-regulated kinase [86]. In addition, linalool showed beneficial effects in the attenuation of the expression of NF-kB and TGF-b1 in the kidney of diabetic subjects [87] and prevents the releasing of pro-inflammatory factors, and inhibits the caspase-3, and caspase-8 expression, and the inflammatory response through the suppression of NF-kB [88, 89].

The second protective property of HBEO is due to the methyl chavicol as the second main compound in the oil belonging to the phenylpropanoids class [90] and can block the voltage-activated sodium channels [91]. This compound also has anti-inflammatory activity by inhibiting leukocyte migration and the stimulation of macrophages’ phagocytosis [92]. Moreover, γ-γ-Muurolene as the third principle compound in HBEO is known to possess antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects [93, 94]. β-elemente is also considered the fourth major compound in HBEO and can regulate oxidative stress and different inflammatory cytokines such as IFN, TNF-α, IL-6/10, and TGF-β in the in vivo and in vitro studies [95]. This compound also induces the apoptosis of tumor cells, and inhibits the P21-activated kinase1 (PAK1) signaling pathway [96, 97] and is used for the treatment of cancer in different organs including the liver [98], stomach [97], lung [99], brain [100], ovary [101], and breast [102].

Additionally, the minor phenolic compounds in the oil have high antioxidant properties and reduce the level of LDL, TriG, and Chol in plasma besides their free radical scavenger activity [103]. Additionally, both HBEO and HBEON increased SOD and CAT, the major hepato-protective endogenous enzymes [104]. Taken together, the mechanisms of antioxidant properties of HBEO and HBEON could be due to the ROS scavenging activity, the iron chelation which initiates the radical reactions, and the inhibition of different enzymes accountable for ROS generation [105], the interference of antioxidants with xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes which block the activated mutagens/carcinogens, and modulates DNA repair along with the regulation of the mRNA gene expressions [106]. Therefore, these mechanisms are very important for the antioxidant, anticarcinogenic, and antimutagenic properties of the oils [107]. These results also showed that HBEON was more effective than HBEO which may be due to the antioxidant effect of WPI used in the preparation of emulsion. WPI is rich in certain amino acids which are known as potent antioxidants such as cysteine, bovine serum albumin, β-lactoglobulin, and α-lactoglobulin [108], and showed potent hepatoprotective against CCl4-induced liver damage [26, 109].

Conclusion

A total of 55 compounds were identified in HBEO representing 98.8% of the oil. The major compound was linalool followed by Methyl chavicol, γ-Muurolene, β-elemene, and Aciphyllene. TiO2-NP administration to rats induced severe oxidative damage in the liver and kidney, increased serum cytokines and DNA fragmentation, disturbed apoptotic gene expression, and histological alteration in the liver. Both HBEO and HBEON with average particles size and ζ-potential were 120 ± 4.5 nm and − 28 ± 1.3 mV were safe and succeeded to induce potent protection against TiO2-NPs; however, HBEON was more effective than HBEO. This effect suggested that the encapsulation of HBEO using WPI enhances the protective role of the bioactive compounds, controls their release, and increased the antioxidant activity. Therefore, HBEON is a good tool for the protection against oxidative damage; disturbances in biochemical parameters, gene expression, DNA damage, and the histological changes result from the exposure to TiO2-NPs and may be suitable for the application in medical, food, and pharmaceutical sectors.

Author Contribution

This work was carried out in collaboration between all authors. Authors MF Sallam, AA El-Nekeety, KA Diab, SH Abdel-Aziem, and HA Sharaf carried out the experimental work, managed the literature searches, and shared in writing the first draft of the manuscript. Authors HMS Ahmed and MA Abdel-Wahhab wrote the protocol, managed the project, managed the analyses of the study, performed the statistical analysis, and wrote the final draft of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB). This work was supported by the Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University, and The National Research Centre, Dokki, Cairo, Egypt, project no. 12050305.

Data Availability

NA.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

This study was carried out in compliance with the guidelines of the National Institute of Health (NIH publication 86–23 revised 1985), and the protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Pharmacy, Cairo University (REC-FOFCU), Cairo, Egypt.

Consent to Participate

NA

Consent for Publication

NA

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Helmy M. S. Ahmed, Email: helmy-moawad@yahoo.com

Mosaad A. Abdel-Wahhab, Email: mosaad_abdelwahhab@yahoo.com, Email: ma.abdelwahab@nrc.Sc.eg

References

- 1.Bayda S, Adeel M, Tuccinardi T, Cordani M, Rizzolio F. The history of nanoscience and nanotechnology: from chemical-physical applications to nanomedicine. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland) 2019;25(1):112. doi: 10.3390/molecules25010112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hong F, Yu X, Wu N, Yu-Qing Zhang YQ (2017) Progress of in vivo studies on the systemic toxicities induced by titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Toxicol Res 6:115–133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Baranowska-Wójcik E, Szwajgier D, Oleszczuk P, Winiarska-Mieczan A. Effects of titanium dioxide nanoparticles exposure on human health-a review. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2020;3(1):118–129. doi: 10.1007/s12011-019-01706-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kandeil MA, Mohammed ET, Hashem KS, Aleya L, Abdel-Daim MM. Moringa seed extract alleviates titanium oxide nanoparticles (TiO2-NPs) induced cerebral oxidative damage and increases cerebral mitochondrial viability. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2019;16:19169–19184. doi: 10.1007/s11356-019-05514-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rashid MM, Forte Tavčer P, Tomšič B. Influence of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on human health and the environment. Nanomaterials (Basel) 2021;11(9):2354. doi: 10.3390/nano11092354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abdel-Wahhab MA, El-Nekeety AA, Mohammed HE, Elshafey OI, Abdel-Aziem SH, Hassan NS. Elimination of oxidative stress and genotoxicity of biosynthesized titanium dioxide nanoparticles in rats via supplementation with whey protein-coated thyme essential oil. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021;28:57640–57656. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-14723-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh SP, Rahman MF, Murty US, Mahboob M, Grover P. Comparative study of genotoxicity and tissue distribution of nano and micron sized iron oxide in rats after acute oral treatment. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013;266(1):56–66. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Praphawatvet T, Peters JI, Williams RO. Inhaled nanoparticles—an updated review. Int J Pharm. 2020;587:119671. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bu Q, Yan G, Deng P, Peng F, Lin H, Xu Y, Cao Z, Zhou T, Xue A, Wang Y, Cen X, Zhao YL. NMR-based metabonomic study of the sub-acute toxicity of titanium dioxide nanoparticles in rats after oral administration. Nanotechnol. 2010;21(12):125105. doi: 10.1088/0957-4484/21/12/125105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Charles S, Jomini S, Fessard V, Bigorgne-Vizade E, Rousselle C, Michel C. Assessment of the in vitro genotoxicity of TiO2 nanoparticles in a regulatory context. Nanotoxicol. 2018;12(4):357–374. doi: 10.1080/17435390.2018.1451567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shukla RK, Sharma V, Pandey AK, Singh S, Sultana S, Dhawan A. ROS-mediated genotoxicity induced by titanium dioxide nanoparticles in human epidermal cells. Toxicol In Vitro. 2011;25(1):231–241. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2010.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Salman AS, Al-Shaikh TM, Hamza ZK, El-Nekeety AA, Bawazir SS, Hassan NS, Abdel-Wahhab MA. Matlodextrin-cinnamon essential oil nanoformulation as a potent protective against titanium nanoparticles-induced oxidative stress, genotoxicity, and reproductive disturbances in male mice. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021;29:39035–39051. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-13518-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maes C, Bouquillon S, Fauconnier ML. Encapsulation of essential oils for the development of biosourced pesticides with controlled release: a review. Molecules. 2019;24(14):2539. doi: 10.3390/molecules24142539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mittal RP, Rana A, Jaitak V. Essential oils: an impending substitute of synthetic antimicrobial agents to overcome antimicrobial resistance. Curr Drug Targets. 2019;20(6):605–624. doi: 10.2174/1389450119666181031122917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chitprasert P, Sutaphanit P. Holy basil (Ocimum sanctum Linn.) essential oil delivery to swine gastrointestinal tract using gelatin microcapsules coated with aluminum carboxymethyl cellulose and beeswax. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62:12641–12648. doi: 10.1021/jf5019438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rezzoug M, Bakchiche B, Gherib A, Roberta A, Guido F, Kilinçarslan Ö, Mammadov R, Bardaweel SK (2019) Chemical composition and bioactivity of essential oils and ethanolic extracts of Ocimum basilicum L. and Thymus algeriensis Boiss and Reut from the Algerian Saharan Atlas. BMC Complement Altern Med 19(1): 146. 10.1186/s12906-019-2556-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Dawood M, El Basuini MF, Zaineldin AI, Yilmaz S, Hasan MT, Ahmadifar E, El Asely AM, Abdel-Latif H, Alagawany M, Abu-Elala NM, Van Doan H, Sewilam H. Antiparasitic and antibacterial functionality of essential oils: an alternative approach for sustainable aquaculture. Pathogens (Basel, Switzerland) 2021;10(2):185. doi: 10.3390/pathogens10020185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ebani VV, Nardoni S, Bertelloni F, Pistelli L, Mancianti F. Antimicrobial activity of five essential oils against bacteria and fungi responsible for urinary tract infections. Molecules. 2018;23(7):1668. doi: 10.3390/molecules23071668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eftekhar N, Moghimi A, Mohammadian Roshan N, Saadat S, Boskabady MH. Immuno-modulatory and anti-inflammatory effects of hydro-ethanolic extract of Ocimum basilicum leaves and its effect on lung pathological changes in an ovalbumin-induced rat model of asthma. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019;19(1):349. doi: 10.1186/s12906-019-2765-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fitsiou E, Pappa A. Anticancer activity of essential oils and other extracts from aromatic plants grown in Greece. Antioxidants. 2019;8:290. doi: 10.3390/antiox8080290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghosh V, Mukherjee A, Chandrasekaran N. Formulation and characterization of plant essential oil based nanoemulsion: evaluation of its larvicidal activity against Aedes aegypti. Asian J Chem. 2013;25:321–323. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Majdi C, Pereira C, Dias MI, Calhelha RC, Alves MJ, Rhourri-Frih B, Charrouf Z, Barros L, Amaral JS, Ferreira ICFR (2020) Phytochemical characterization and bioactive properties of cinnamon basil (Ocimum basilicum cv. 'Cinnamon') and lemon basil (Ocimum citriodorum). Antioxidants (Basel) 9(5): 369. 10.3390/antiox9050369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Shah B, Davidson PM, Zhong Q. Nano dispersed eugenol has improved antimicrobial activity against Escherichia coli O157:H7 and Listeria monocytogenes in bovine milk. Int J Food Microbiol. 2013;161(1):53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2012.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aguilar-Veloz LM, Calderón-Santoyo M, González YV, Ragazzo-Sánchez JA. Application of essential oils and polyphenols as natural antimicrobial agents in postharvest treatments: Advances and challenges. Food Sci Nutr. 2020;8:2555–2568. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.1437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sandra F, Saidi S, Richard H, Ellen A. Essential oils and their applications—a mini review. Adv Nutr Food Sci. 2019;4:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Abdel-Wahhab MA, El-Nekeety AA, Hassan NS, Gibriel AA, Abdel-Wahhab KG. Encapsulation of cinnamon essential oil in whey protein enhances the protective effect against single or combined sub-chronic toxicity of fumonisin B1 and/or aflatoxin B1 in rats. Environ Sci Pollu Res. 2018;25(2):29144–29161. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-2921-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lammari N, Louaer O, Meniai AH, Elaissari A. Encapsulation of essential oils via nanoprecipitation process: overview, progress, challenges and prospects. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(5):431. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12050431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rao GK, Ashok CH, Venkateswara Rao K, Shilpa Chakra CH, Rajendar V (2015) synthesis of Tio2 nanoparticles from orange fruit waste. Int J Multidiscip Adv Res Trends II(I): 82–90.

- 29.El-Nekeety AA, Hassan ME, Hassan RR, Elshafey OI, Hamza ZK, Abdel-Aziem SH, Hassan NS, Abdel-Wahhab MA. Nanoencapsulation of basil essential oil alleviates the oxidative stress, genotoxicity and DNA damage in rats exposed to biosynthesized iron nanoparticles. Heliyon. 2021;7(7):e07537. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Adams RB. Identification of essential oil components by gas chromatography/quadruple mass spectroscopy. Carol Stream, IL, USA: Allured publishing Co; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jinapong N, Suphantharika M, Jammong P. Production of instant soymilk powders by ultrafiltration, spray drying and fluidized bed agglomeration. J Food Eng. 2008;84:194–205. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin CC, Hsu YF, Lin TC, Hsu FL, Hsu HY. Antioxidant and hepatoprotective activity of Punicalagin and Punicalin on carbon tetrachloride induced liver damage in rats. J Pharm Pharmacol. 1989;50(7):789–794. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.1998.tb07141.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bancroft D, Stevens A, Turmer R (1996) Theory and practice of histological technique, 4th ed. Churchill Living Stone, Edinburgh 36–42.

- 34.El-makawy A, Ibrahim FM, Mabrouk DM, Abdel-Aziem SH, Sharaf HA, Ramadan MF. Efficiency of turnip bioactive lipids in treating osteoporosis through activation of Osterix and suppression of Cathepsin K and TNF-α signaling in rats. Environ Sci Pollu Res. 2020;27:20950–20961. doi: 10.1007/s11356-020-08540-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perandones CE, Illera VA, Peckham D, Stunz LL, Ashman RF (1993) Regulation of apoptosis in vitro in mature murine spleen T cells. J Immunol 151:3521–3529 [PubMed]

- 36.Fahmy MA, Diab KA, Abdel-Samie NS, Omara EA, Hassan ZM. Carbon tetrachloride induced hepato/renal toxicity in experimental mice: antioxidant potential of Egyptian Salvia officinalis L essential oil. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2018;25:27858–27876. doi: 10.1007/s11356-018-2820-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Amor G, Sabbah M, Caputo L, Idbella M, De Feo V, Porta R, Fechtali T, Mauriello G. Basil essential oil: composition, antimicrobial properties and microencapsulation to produce active chitosan films for food packaging. Foods (Basel, Switzerland) 2021;10(1):121. doi: 10.3390/foods10010121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Benedec D, Oniga I, Toiu A, Tiperciuc B, Tămaş M, Vârban, ID, Crişan G (2013) GC-MS analysis of the essential oil obtained from ocimum basilicum L.“holland” cultivar FARMACIA 61(3): 448–453.

- 39.Olugbade TA, Kolipha-Kamara MI, Elusiyan CA, Onawunmi GO, Ogundaini AO. Essential oil chemotypes of three ocimum species found in Sierra Leone and Nigeria. Med Aromat Plants. 2017;6:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghasemi Pirbalouti A, Malekpoor F, Salimi A. Chemical composition and yield of essential oil from two Iranian species of basil (Ocimum ciliatum and Ocimum basilicum) Trends Phytochem Res. 2017;1:3–8. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ahmed AF, Attia FAK, Liu Z, Li C, Wei J, Wenyi Kang W (2019) Antioxidant activity and total phenolic content of essential oils and extracts of sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) plants. Food Sci Hum Well 8(3): 299–230.

- 42.Diniz do Nascimento L, Moraes AAB, Costa KSD, Pereira Galúcio JM, Taube PS, Costa CML, Neves Cruz J, de Aguiar Andrade EH, Faria LJG, Bioactive natural compounds and antioxidant activity of essential oils from spice plants: new findings and potential applications. Biomolecules. 2020;10(7):988. doi: 10.3390/biom10070988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goula AM, Adamopoulos KG. A method for pomegranate seed application in food industries: Seed oil encapsulation. Food Bioprod Process. 2012;90(4):639–652. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eratte D, Wang B, Dowling K, Barrow CJ, Adhikari BP. Complex coacervation with whey protein isolate and gum arabic for the microencapsulation of omega-3 rich tuna oil. Food Funct. 2014;5:2743–2750. doi: 10.1039/c4fo00296b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Noello C, Carvalho AGS, Silva VM, Hubinger MD. Spray dried microparticles of chia oil using emulsion stabilized by whey protein concentrate and pectin by electrostatic deposition. Food Res Int. 2016;89(1):549–557. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2016.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roger B, Lagarce F, Garcion E, Benoit JP. Biopharmaceutical parameters to consider in order altering the fate of nanocarriers after oral delivery. Nanomed. 2010;5(2):287–306. doi: 10.2217/nnm.09.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.McClements DJ, Rao J. Food-grade nanoemulsions: formulation, fabrication, properties, performance, biological fate, and potential toxicity. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2011;51(4):285–330. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2011.559558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mohammed ET, Safwat GM. Grape seed proanthocyanidin extract mitigates titanium dioxide nanoparticle (TiO2-NPs)-induced hepatotoxicity through TLR-4/NF-κB signaling pathway. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2020;196:579–589. doi: 10.1007/s12011-019-01955-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thapa BR, Walia A. Liver function tests and their interpretation. Ind J Pediatr. 2007;74(7):663–671. doi: 10.1007/s12098-007-0118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Abdel-Wahhab MA, El-Nekeety AA, Hathout AS, Salman AS, Abdel-Aziem SH, Sabry BA, Hassan NS, Abdel-Aziz MS, Aly SE, Jaswir I. Bioactive compounds from Aspergillus niger extract enhance the antioxidant activity and prevent the genotoxicity in aflatoxin B1-treated rats. Toxicon. 2020;181:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2020.04.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ahamed M, AlSalhi MS, Siddigui MKJ. Silver nanoparticle applications on human health. Clin Chim Acta. 2010;411:1841–1848. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fartkhooni FM, Noori A, Mohammadi A. Effects of titanium dioxide nanoparticles toxicity on the kidney of male rats. Int J Life Sci. 2016;10(1):65–69. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Duan Y, Liu J, Ma L, Li N, Liu H, Wang J, Zheng L, Liu C, Wang X, Zhao X, Yan J, Wang S, Wang H, Zhang X, Hong F. Toxicological characteristics of nanoparticulate anatase titanium dioxide in mice. Biomater. 2010;31(5):894–899. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Antoni R, Johnston KL, Collins AL, Robertson MD. Intermittent v continuous energy restriction differential effects on postprandial glucose and lipid metabolism following matched weight loss in overweight/obese participants. Br J Nutr. 2018;119(5):507–516. doi: 10.1017/S0007114517003890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen Z, Han S, Zheng P, Zhou D, Zhou S, Jia G. Effect of oral exposure to titanium dioxide nanoparticles on lipid metabolism in Sprague-Dawley rats. Nanoscale. 2020;12(10):5973–5986. doi: 10.1039/c9nr10947a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Reiner Ž. Hyper-triglyceridaemia and risk of coronary artery disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14(7):401–411. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2017.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Foroozandeh P, Aziz AA. Merging worlds of nanomaterials and biological environment factors governing protein corona formation on nanoparticles and its biological consequences. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2015;10:221 . doi: 10.1186/s11671-015-0922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rikans LE, Hornbrook KR. Lipid peroxidation, antioxidant protection and aging. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 1997;1362:116–127. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(97)00067-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reeves JF, Davies SJ, Dodd NJ, Jha AN. Hydroxyl radicals (OH) are associated with titanium dioxide (TiO2) nanoparticle-induced cytotoxicity and oxidative DNA damage in fish cells. Mutat Res. 2008;640(1–2):113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shi H, Magaye R, Castranova V, Zhao J. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles : a review of current toxicological data. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2013;10:15. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-10-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Latchoumycandane C, Mathur P. Induction of oxidative stress in the rat testis after short-term exposure to the organochlorine pesticide methoxychlor. Arch Toxicol. 2002;76(12):692–698. doi: 10.1007/s00204-002-0388-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sharma P, Singh R, Jan M. Dose-dependent effect of deltamethrin in testis, liver, and kidney of Wistar rats. Toxicol Int. 2014;21(2):131–139. doi: 10.4103/0971-6580.139789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Huerta-García E, Pérez-Arizti JA, Márquez-Ramírez SG, Delgado-Buenrostro NL, Chirino YI, Iglesias GG, López-Marure R. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles induce strong oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage in glial cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2014;73:84–94. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2014.04.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kroemer G, Galluzzi L, Brenner C. Mitochondrial membrane permeabilization in cell death. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:99–163. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jebali R, Ben Salah-Abbès J, Abbès S, Hassan AM, Abdel-Aziem SH, El-Nekeety AA, Oueslati R, Abdel-Wahhab MA. Lactobacillus plantarum alleviate aflatoxins (B1 and M1) induced disturbances in the intestinal genes expression and DNA fragmentation in mice. Toxicon. 2018;146:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.toxicon.2018.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Peng X, Chen K, Chen J, Fang J, Cui H, Zuo Z, Deng J, Chen Z, Geng Y, Lai W. Aflatoxin B1 affects apoptosis and expression of Bax, Bcl-2, and caspase-3 in thymus and bursa of fabricius in broiler chickens. Environ Toxicol. 2016;31(9):1113–1120. doi: 10.1002/tox.22120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Duan XX, Ou JS, Li Y, Su JJ, Ou C, Yang C, Yue HF, Ban KC. Dynamic expression of apoptosis-related genes during development of laboratory hepatocellular carcinoma and its relation to apoptosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11(30):4740–4744. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i30.4740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bhattacharya K, Davoren M, Boertz J, Schins RP, Hoffmann E, Dopp E. Titanium dioxide nanoparticles induce oxidative stress and DNA-adduct formation but not DNA-breakage in human lung cells. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2009;6:17. doi: 10.1186/1743-8977-6-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kansara K, Patel P, Shah D, Shukla RK, Singh S, Kumar A, Dhawan A. TiO2 nanoparticles induce DNA double strand breaks and cell cycle arrest in human alveolar cells. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2015;56:204–217. doi: 10.1002/em.21925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wani MR, Shadab G (2020) Titanium dioxide nanoparticle genotoxicity: a review of recent in vivo and in vitro studies. Toxicol Ind Health 36:514–530 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71.Jin C, Tang Y, Fan XY, Ye XT, Li XL, Tang K, Zhang YF, Li AG, Yang YJ (2013) In vivo evaluation of the interaction between titanium dioxide nanoparticle and rat liver DNA. Toxicol Ind Health 29:235–244 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 72.Brandão F, Fernández-Bertólez N, Rosário F, Bessa MJ, Fraga S, Pásaro E, Teixeira JP, Laffon B, Valdiglesias V, Costa C. Genotoxicity of TiO2 nanoparticles in four different human cell lines (A549, HEPG2, A172 and SH-SY5Y) Nanomater (Basel) 2020;10(3):412. doi: 10.3390/nano10030412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kazimirova A, Baranokova M, Staruchova M, Drlickova M, Volkovova K, Dusinska M (2019) Titanium dioxide nanoparticles tested for genotoxicity with the comet and micronucleus assays in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo. Mutat Res 843:57–65 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 74.Tavares AM, Louro H, Antunes S, Quarré S, Simar S, De Temmerman PJ, Verleysen E, Mast J, Jensen KA, Norppa H, Nesslany F, Silva MJ. Genotoxicity evaluation of nanosized titanium dioxide, synthetic amorphous silica and multi-walled carbon nanotubes in human lymphocytes. Toxicol in Vitro. 2014;28:60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.tiv.2013.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sycheva LP, Zhurkov VS, Iurchenko VV, Daugel-Dauge NO, Kovalenko MA, Krivtsova EK, Durnev AD (2011) Investigation of genotoxic and cytotoxic effects of micro and nanosized titanium dioxide in six organs of mice in vivo. Mutat Res Genet Toxicol Environ Mutagen 726(1):8–14 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Li H, Ding F, Xiao L, Shi R, Wang H, Han W, Huang Z. Food-derived antioxidant polysaccharides and their pharmacological potential in neurodegenerative diseases. Nutrients. 2017;9:778. doi: 10.3390/md17120674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Fadoju O, Ogunsuyi O, Akanni O, Alabi O, Alimba C, Adaramoye O, Cambier S, Eswara S, Gutleb AC, Bakare A. Evaluation of cytogenotoxicity and oxidative stress parameters in male Swiss mice co-exposed to titanium dioxide and zinc oxide nanoparticles. Environ Toxicol Pharmacol. 2019;70:103204. doi: 10.1016/j.etap.2019.103204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Attia AM, Nasr HM. Dimethoate-induced changes in biochemical parameters of experimental rat serum and its neutralization by black seed Nigella sativa L oil Slovak. J Anim Sci. 2009;42(2):87–94. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Valentini X, Rugira P, Frau A, Tagliatti V, Conotte R, Laurent S, Colet JM, Nonclercq DD (2019) Hepatic and renal toxicity induced by TiO2 nanoparticles in rats: a morphological and metabonomic study. J Toxicol Mar 3: 2019:5767012. 10.1155/2019/5767012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Pialoux V, Mounier R, Brown AD, Steinback CD, Rawling JM, Poulin MJ. Relationship between oxidative stress and HIF-1α mRNA during sustained hypoxia in humans. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009;46(2):321–326. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Olmedo DG, Tasat DR, Evelson P, Guglielmotti MB, Cabrini RL. Biological response of tissues with macrophagic activity to titanium dioxide. J Biomed Mater Res Part A. 2008;84(4):1087–1093. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Avetisyan A, Markosian A, Petrosyan M, Sahakyan N, Babayan A, Aloyan S, Trchounian A. Chemical composition and some biological activities of the essential oils from basil Ocimum different cultivars. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17:60. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1587-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nikolić B, Mitić-Ćulafić D, Vuković-Gačić B, Knežević-Vukčević J (2019) Plant mono-terpenes camphor, eucalyptol, thujone, and DNA repair. In: Patel V, Preedy V (eds). Handbook of Nutrition, Diet, and Epigenetics. Springer, Cham. 10.1007/978-3-319-55530-0_106.

- 84.Rafael TM, Yolanda GR, Patricia RC, Alfredo SM, Joel LM, Alejandra OZ, Rafael SG. Antioxidant activity of the essential oil and its major terpenes of Satureja macrostema (Moc. and Sessé ex Benth.) Briq Pharmacogn Mag. 2018;13:S875–S880. doi: 10.4103/pm.pm_316_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ghosh T, Srivastava SK, Gaurav A, Kumar A, Kumar P, Yadav AS, Pathania R, Navani NK (2019) A combination of linalool, vitamin c, and copper synergistically triggers reactive oxygen species and DNA damage and inhibits Salmonella enterica subsp. enterica serovar typhi and Vibrio fluvialis. Appl Environ Microbiol 85(4): e02487–18. 10.1128/AEM.02487-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 86.Huo M, Cui X, Xue J, Chi G, Gao R, Deng X, Guan S, Wei J, Soromou LW, Feng H, Wang D. Anti-inflammatory effects of linalool in RAW 264.7 macrophages and lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury model. J Surg Res. 2013;180:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2012.10.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Deepa B, Venkatraman Anuradha C. Effects of linalool on inflammation, matrix accumulation and podocyte loss in kidney of streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Toxicol Mech Methods. 2013;23:223–234. doi: 10.3109/15376516.2012.743638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.De Andrade CJ, Andrade LR, Silvana SM, Pastore G, Jauregi P. A novel approach for the production and purification of mannosylerythritol lipids (MEL) by Pseudozyma tsukubaensis using cassava wastewater as substrate. Sep Purif Technol. 2017;180:157–167. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Li J, Zhang X, Huang H. Protective effect of linalool against lipopoly-saccharide/d-galactosamine-induced liver injury in mice. Int Immunopharmacol. 2014;23:523–529. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2014.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Paula JF, Farago PV, Ribas JLC, Spinardi GMS, Döll MP, Artoni RF, Zawadzki SF. In vivo evaluation of the mutagenic potential of estragole and eugenol chemotypes of Ocimum selloi Benth essential oil Lat. Am J Pharm. 2007;26(6):846–51. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Silva-Alves KS, Ferreira-da-Silva FW, Peixoto-Neves D, Viana-Cardoso KV, Moreira-Júnior L, Oquendo MB, Oliveira-Abreu K, Albuquerque AA, Coelho-de-Souza AN, Leal-Cardoso JH. Estragole blocks neuronal excitability by direct inhibition of Na+ channels. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2013;46(12):1056–1063. doi: 10.1590/1414-431X20133191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Silva-Comar FM, Wiirzler LA, Silva-Filho SE, Kummer R, Pedroso RB, Spironello RA, Silva EL, Bersani-Amado CA, Cuman RK. Effect of estragole on leukocyte behavior and phagocytic activity of macrophages. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2014;2014:784689. doi: 10.1155/2014/784689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Martins FT, Doriguetto AC, de Souza TC, de Souza KR, Dos Santos MH, Moreira ME, Barbosa LC. Composition and anti-inflammatory and antioxidant activities of the volatile oil from the fruit peel of Garcinia brasiliensis. Chem Biodivers. 2008;2:251–258. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200890022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Queiroz JC, Antoniolli AR, Quintans-Júnior LJ, Brito RG, Barreto RS, Costa EV, da Silva TB, Prata AP, de Lucca WJr, Almeida JR , Lima JT, Quintans JS. Evaluation of the anti-inflammatory and antinociceptive effects of the essential oil from leaves of Xylopia laevigata in experimental models. Sci World J. 2014;201:816450. doi: 10.1155/2014/816450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Xie Q, Li F, Fang L, Liu W, Gu C (2020) The antitumor efficacy of β-Elemene by changing tumor inflammatory environment and tumor microenvironment. Biomed Res Int. 10.1155/2020/6892961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 96.Bai Z, Yao C, Zhu J, Xie Y, Ye XY, Bai R, Xie T. Anti-tumor drug discovery based on natural product β-elemene anti-tumor mechanisms and structural modification. Molecules. 2021;26(6):1499. doi: 10.3390/molecules26061499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Liu JS, Che XM, Chang S, Qiu GL, He SC, Fan L, Zhao W, Zhang ZL, Wang SF. β-elemene enhances the radiosensitivity of gastric cancer cells by inhibiting Pak1 activation. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21(34):9945–9956. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v21.i34.9945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Mao Y, Zhang J, Hou L, Cui X. The effect of beta-elemene on alpha-tubulin polymerization in human hepatoma HepG2 cells. Chin J Cancer Res. 2013;25:6770–776. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.1000-9604.2013.12.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.K Zhou L Wang R Cheng X Liu S Mao 2017 Yan Y (2017) Elemene increases autophagic apoptosis and drug sensitivity in human cisplatin (DDP)-resistant lung cancer cell line SPC-A-1/DDP by inducing beclin-1 expression Oncol Res10.3727/096504017X14954936991990 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 100.Zhu T, Li X, Luo L, Wang X, Li Z, Xie P, Gao X, Song Z, Su J, Liang G (2015) Reversion of malignant phenotypes of human glioblastoma cells by β-elemene through β-catenin-mediated regulation of stemness-, differentiation- and epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition-related molecules. J Transl Med 13:356. 10.1186/s12967-015-0727-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 101.Li QQ, Lee RX, Liang H, Wang G, Li JM, Zhong Y, Reed E. β-Elemene enhances susceptibility to cisplatin in resistant ovarian carcinoma cells via downregulation of ERCC-1 and XIAP and inactivation of JNK. Int J Oncol. 2013;43(3):721–728. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2013.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Zhang J, Zhang HD, Chen L, Sun DW, Mao C, Chen W, Wu JZ, Zhong SL, Zhao JH, Tang JH. β-elemene reverses chemoresistance of breast cancer via regulating MDR-related microRNA expression. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2014;34(6):2027–2037. doi: 10.1159/000366398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ebenyi LN, Ibiam UA, Aja PM. Effects of Allium sativum extract on paracetamol induced hepatotoxicity in albino rats. IRJBB. 2012;2:93–97. [Google Scholar]

- 104.El-Banna H, Soliman M, Al-Wabel N. Hepatoprotective effects of thymus and salvia essential oils on paracetamol induced toxicity in rats. J Phys Pharm Adv. 2013;3:41–47. [Google Scholar]

- 105.Edenharder R, Grȕnhage D. Free radical scavenging abilities of flavonoids as mechanism of protection against mutagenicity induced by tert-butyl hydroperoxide or cumene hydroperoxide in Salmonella typhimurium TA102. Mutat Res. 2003;540:1–18. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(03)00114-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Paramasivan P, Kankia IH, Langdon SP, Deeni YY (2019) Emerging role of nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 in the mechanism of action and resistance to anticancer therapies. Cancer Drug Resist 2:490–515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 107.De Flora S, Ferguson RL (2005) Overview of mechanisms of cancer chemo preventive agents. Mutat Res 591:8–15 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 108.Minj S, Anand S (2020) Whey proteins and its derivatives: bioactivity, functionality, and current applications. Dairy 1(3):233–258

- 109.Gad AS, Khadrawy YA, El-Nekeety AA, Mohamed SR, Hassan NS,, Abdel-Wahhab MA (2011) Antioxidant activity and hepatoprotective effects of whey protein and spirulina in rats. Nutr 27(5):582–589 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 110.Aboshanab MH, El-Nabarawi MA, Teaima MH, El-Nekeety AA, Abdel-Aziem SH, Hassan NS, Abdel-Wahhab MA (2020) Fabrication, characterization and biological evaluation of silymarin nanoparticles against carbon tetrachloride-induced oxidative stress and genotoxicity in rats. Int J Pharm 587:119639. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2020.119639 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 111.Liu W, Wang G, Yakovlev AG (2002) Identification and functional analysis of the rat caspase-3 gene promoter. J Biol Chem 277(10):8273–8278 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 112.Hassan MA, El-Nekeety AA, Abdel-Aziem SH, Hassan NS, Abdel-Wahhab MA (2019) Zinc citrate incorporation with whey protein nanoparticles alleviate the oxidative stress complication and modulate gene expression in the liver of rats. Food Chem Toxicol 125:439–45 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 113.Yonguc GN, Dodurga Y, Kurtulus A, Boz B, Acar K (2012) Caspase 1, Caspase 3, TNF-alpha, p53, and Hif1-alpha gene expression status of the brain tissues and hippocampal neuron loss in short-term dichlorvos exposed rats. Mol Biol Rep 39(12):10355–10360 [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

NA.