Abstract

Co-occurring maternal depression and antisocial personality disorder (ASPD) are associated with the development of psychopathology in children, yet little is known about risk mechanisms. In a sample of 122 racially-diverse and economically-disadvantaged families, we prospectively investigated 1) to what extent child socioemotional problems were related to maternal depression-only, ASPD-only, or the co-occurrence of both; and 2) specificity in parenting-related mechanisms linking single-type or comorbid maternal psychopathology to child outcomes at age three. Compared to mothers without either ASPD or depression, exposure to maternal depression-only and comorbid depression/ASPD predicted child problems as a function of greater parenting stress and lower maternal sensitivity. Mothers with comorbid depression/ASPD uniquely exhibited more negative parenting and had children with more socioemotional problems than mothers with depression-only. Compared to mothers with neither ASPD nor depression, mothers with depression-only uniquely impacted child difficulties via lower maternal efficacy. Study findings suggest areas of parenting intervention.

Maternal depression, which is among the most prevalent (10-20% of new mothers; Wisner et al., 2013) and burdensome of maternal mental health conditions, has consistently emerged as a nonspecific risk factor for the development of child emotional and behavioral problems (Cicchetti & Toth, 1998; Goodman, 2020). In a meta-analytic review comprised of 193 studies and over 80,000 families, maternal depression was found to be moderately associated with greater internalizing, externalizing, and general psychopathology symptoms in children (Goodman et al., 2011). During early childhood, depression in mothers is associated with offspring negative affectivity, insecure and disorganized attachment, social disengagement, emotion dysregulation, and neurobiological impairments linked to psychopathology symptoms (Goodman, 2020; Gotlib et al., 2014; Toth et al., 2009). Additionally, there is significant variability in the presentation of maternal depression (PACT Consortium, 2015), and little is known about how this heterogeneity differentially impacts children. As such, there have been growing calls for intergenerational investigations that consider variability among depressed mothers (e.g., comorbidities; Goodman, 2020).

Maternal depression can often co-occur with other disorders, which can amplify the effects of maternal depression on child outcomes (Carter et al., 2001; Sellers et al., 2013). Specifically, there is limited knowledge on the relative or cumulative effects of comorbid Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) and Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD) on child socioemotional functioning (Conroy et al., 2012; Kim-Cohen et al., 2006; Sellers et al., 2014). Failing to attend to this common pattern of comorbidity—affecting ~35% of all individuals who meet criteria for MDD (Cloninger et al., 1997) and ~14% of mothers in high-risk samples (Kim-Cohen et al., 2014; Sellers et al., 2013)—may obfuscate and potentially overestimate the effects of maternal depression on child outcomes.

Multiple theoretical explanations of comorbidity could account for the common co-occurrence of MDD/ASPD. The two disorders share many etiological risk factors (e.g., child maltreatment; Russotti et al., 2021) and have common genetic vulnerabilities (Fu et al., 2002), so comorbidity may be a result of shared etiology. Individuals with ASPD also have a significantly elevated risk of developing MDD (Fu et al., 2002). A reciprocal (or causal) model of comorbidity suggests that features of ASPD (e.g., difficulty with interpersonal relationships and social and occupational functioning) contribute to an ongoing vulnerability to depression as detailed by interpersonal theories of depression (Weissman & Markowits, 2002). Finally, in some instances, MDD/ASPD comorbidity may partially be a function of an array of symptom overlap (e.g., affective and interpersonal impairments; Hatchett, 2015).

There are many reasons to believe that MDD/ASPD comorbidity may be relevant to understanding how maternal depression transmits risk to children (Goodman, 2020). Similar to maternal depression, children exposed to maternal ASPD demonstrate greater emotional and behavioral difficulties (Jaffee et al., 2006; Davies et al., 2012) and risk appears to be mediated through the same environmental mechanisms as maternal MDD (e.g., parenting; Harold et al., 2012; Silberg et al., 2012). Results from the scant literature in this line of research suggest that depression that co-occurs with antisocial behavior conveys greater risk for emotional and behavioral problems in offspring than either condition alone (Conroy et al., 2012; Kim-Cohen et al., 2006). Thus, children of mothers managing depression and ASPD may be at extremely high risk for psychopathology. However, questions remain regarding how these co-occurring problems may uniquely or similarly transmit risk to offspring (Goodman, 2020).

Several transacting, multi-level mechanisms may explain how comorbid maternal psychopathology is associated with offspring outcomes (Cicchetti et al., 1998). Goodman and Gotlib (1999) developed a model that proposed four mechanistic pathways linking depression across generations: 1) genetic heritability; 2) innate neurobiological dysfunction; 3) exposure to parental cognitions/behaviors/affect and disturbed parent-child processes; 4) and exposure to stressful contexts (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999). Accordingly, any of these four mechanisms, occurring individually or in interaction with one another, may account for the transmission of risk for psychopathology (Goodman & Gotlib, 1999). Informed by this theory, the present study considers how one of these four mechanisms (parenting-related processes) may link maternal depression that co-occurs with antisociality to offspring outcomes.

It is well-established that the disturbances that characterize maternal MDD or ASPD may thwart a mother’s ability to provide salubrious parental care, which may in turn contribute to the development of psychopathology in children (Harold et al., 2012). As a result of their depression, mothers may feel less competent or effective in their parenting (Michl et al., 2015) and report greater parenting stress (Fredriksen et al., 2019), which can directly impact child behavior (e.g., Neece et al., 2012). Furthermore, studies indicate that maternal MDD is associated with less sensitive and responsive parenting, more negativity and less warmth in parent-child interactions, and the use of more coercive and hostile parenting strategies, all of which may contribute to adverse emotional/behavioral functioning in offspring (Goodman, 2020; Gotlib et al., 2020).

Although there is comparatively less research on the distinct parenting profiles of mothers with ASPD, mothers exhibiting antisocial behaviors tend to show significant impairments in many of the same aspects of parenting as mothers with depression, including negative parenting (e.g., Khlar et al., 2017), coercion and hostility (e.g., Bosquet & Egeland), rejection (e.g., Trentacosta & Shaw, 2008), lack of warmth (e.g., Jaffee et al., 2006), and insensitivity and unresponsiveness (e.g., Conroy et al., 2010). They also tend to experience more parenting stress (Kim-Cohen et al., 2006) and, less ubiquitously, exhibit lower parenting efficacy (Cloninger et al., 1997; Laulik et al., 2013) than parents without mental health problems. Such parenting qualities may transmit psychopathology risk to offspring, controlling for possible genetic and sociodemographic confounds (Harold et al., 2012).

A deeper understanding of how co-occurring maternal MDD/ASPD predict offspring psychopathology as a function of the parenting environment offers promise because parenting behaviors, cognitions, and stress represent modifiable targets for preventive interventions (Handley et al., 2017; Toth et al., 2006). However, the literatures on maternal MDD and ASPD have largely been developed independently and rarely have studies examined the independent and specific parenting-related constructs that may mediate the relations between child mental health and maternal MDD, relative to ASPD. For example, it remains unclear whether parenting difficulties frequently attributed to maternal depression (e.g., hostility) reflect unique features of depression, or represent the unmeasured presence of maternal ASPD (Sellers et al., 2014). Comorbidity of ASPD/MDD may reflect both a shared attribute of irritability/hostility (Shay & Knutson, 2008) and also distinct contributions of each disorder, resulting in unique or similar parenting practices. For instance, maternal depressive symptoms in the presence or absence of ASPD may create distinct parental environments (e.g., hostile-intrusive vs. withdrawn-unavailable parenting) that account for unique variance in child socioemotional outcomes and risk processes (Cicchetti & Toth, 1998). Teasing out these differences can inform preventive efforts by enabling parent-child interventions to be uniquely tailored to address the respective parenting processes of mothers with depression or co-occurring depression and ASPD.

There is some evidence that, compared to mothers with depression only, mothers with depression accompanied by ASPD symptoms engage in more hostile and less warm caregiving with young children (Carter et al., 2001; Kim-Cohen et al., 2006). Paired with the knowledge that suboptimal caregiving is robustly associated with psychopathology in offspring (Cicchetti & Toth, 1998), it is likely that aspects of parenting at least partially explain the elevated psychopathology risk observed in young children of mothers suffering from comorbid MDD/ASPD (Conroy et al., 2012). In a prospective investigation, Sellers et al (2014) found that, although low warmth and greater hostility mediated associations between maternal depression and adolescent offspring psychopathology, the effects were attenuated when accounting for co-occurring maternal antisocial behaviors, which were modestly correlated with maternal depressive symptoms. This study indicates that some intergenerational risk processes that are presumed to be the result of maternal depression may be more accurately attributed to the presence of co-occurring antisociality. As such, there is need for studies on maternal depression and antisociality that test multiple competing parenting mechanisms within a single statistical model to isolate the relative strengths of each mediating effect and reveal translatable findings that can be used to design more precise targets for parent-child interventions (Goodman, 2020).

There are several salient questions that can advance this line of research. Studies examining the association between comorbid maternal ASPD/MDD on offspring psychopathology have focused on school-aged children and adolescents (Kim-Cohen et al., 2006; Sellers et al., 2014), with only one study observing effects in early childhood (Conroy et al., 2012). Given the particularly potent effect that exposure to maternal psychopathology can have on the development of psychopathology in early childhood (ages 0-5; Goodman et al., 2011), as well as the compelling evidence that symptoms in early childhood often portend pathways to more severe and recurrent psychopathology (Luby et al., 2014), it is critical to examine these intergenerational processes among mothers with young children.

Further, knowledge is scarce on the intergenerational risk processes linking maternal MDD and ASPD to offspring outcomes in economically-disadvantaged contexts, where the prevalence of MDD and APSD are high (Ertel et al., 2011; Jaffee et al., 2006). Families with mothers suffering from depression and/or ASPD typically differ on sociodemographic variables, which may act to confound observed differences in parenting and child outcomes, thereby obfuscating our understanding of the true associations and developmental processes at work. For instance, economic disadvantage can deplete a family’s resources for coping with the effects of maternal psychopathology and generate a constellation of stressors that contribute to suboptimal parenting and offspring maladaptation (Goodman, 2020).

Finally, research examining the intergenerational effects of both ASPD and MDD is often limited by non-independence of informants (i.e., a reliance on mother for multiple constructs of interest) and there is equivocal evidence regarding the validity of using single sources of information for parental psychopathology, parenting behavior, and child functioning (e.g., Olino et al., 2021). Thus, additional studies are needed that use multiple informants of both risk (i.e., maternal MDD/ASPD) and outcomes (i.e., parenting and child psychopathology). Further, observational methods to assess parenting behaviors are needed, especially when jointly considering the effect of parents’ self-perceived competency in child rearing.

Present Study

To extend limited existing research, the present study tested a multiple-mediator model examining whether four aspects of the parenting environment (i.e., maternal sensitivity, negative parenting, maternal efficacy, and overall parenting stress) mediated relations between comorbid maternal MDD and ASPD (compared to MDD-only, ASPD-only, or neither diagnosis) and emotional and behavioral functioning in children at age three. We selected a set of parenting-related mechanisms that encompassed parenting behaviors, cognitions, and stressors that are theoretically- (e.g., Goodman & Gotlib, 1999) and empirically-implicated as plausible mechanisms linking both maternal ASPD and MDD to general psychopathology risk in offspring: namely, negative parenting, defined as hostility, rejection, and coercive control directed at the child (Harold et al., 2012; Khlar et al. 2017; Trentacosta & Shaw, 2008); maternal sensitivity, defined as the ability to respond promptly and appropriately to child’s cues (Goodman et al., 2017; Milgrom et al. 2010; Conroy et al., 2010); maternal efficacy beliefs, or the degree to which mothers perceive themselves as able to master the varied tasks associated with caregiving (Coleman & Karraker, 1998; Michl et al., 2015); and mother’s self-reported parenting stress (Fredriksen et al., 2019; Kim-Cohen et al., 2006). We also chose to focus on child psychopathology more generally, given the young age of our participants and the consistent findings that maternal psychopathology is broadly associated with general psychopathology symptoms, rather than specific disorders, in young children (Goodman, 2011; Silberg et al., 2012). Given the noted importance of reporter-independent associations, this study utilized both maternal reports and observer ratings of parenting constructs and child symptoms.

We were interested in investigating 1) to what extent the emergence of child emotional and behavioral problems was specifically related to maternal MDD-only, ASPD-only, or the co-occurrence of both disorders; and 2) possible specificity in parenting-related mechanisms linking single-type or comorbid maternal psychopathology to early childhood outcomes. We hypothesized that parenting stress, maternal efficacy, and maternal sensitivity would be universal mechanisms linking MDD and ASPD to child emotional/behavioral problems and that negative parenting would be a specific mechanism for maternal ASPD and comorbid ASPD/MDD.

Methods

Participants and Procedures

Data for this study were drawn from a larger randomized clinical trial (RCT) evaluating the effectiveness of interpersonal psychotherapy for depression among low-income mothers with a 12-month-old infant (see Toth et al., 2013). To avoid any confounding intervention effects, only mothers from the enhanced control condition (n = 66) and the nondepressed control arm (n = 56) were included in the current analyses (N =122 dyads). Women in the enhanced control condition were not required to be in treatment but were offered referral to typical community services, as it is unethical to withhold treatment for those identified as depressed. Nontreatment seeking, biological mothers and their infants were recruited from primary care clinics serving low-income women and Women, Infant, and Children (WIC) clinics in Western New York. During routine screenings at WIC clinics and primary care clinics, trained research assistants approached clients and inquired about the age of their children. Women with infants 12 months of age or younger were provided with an explanation of the study and, if interested and eligible, were enrolled. Eligible mothers needed to be within the age range of 18–44, have a 12-month-old infant, and reside at or below the federal poverty level. Seventy-eight percent of the sample was below the federal poverty level, and 96% met WIC criteria (185% of the poverty level).

Mothers ranged in age from 18 to 39 (M = 24.86) and identified as Black (n = 73, 59.8%), White (n = 46, 37.7%), Native American (n = 1, 0.8%), and biracial (n = 2, 1.6%); 19.3% identified as Hispanic (n = 24). Median annual income for families in this sample was approximately US $17,000, with nearly all (>99%) of families receiving some form of public assistance. Fifty percent (n = 61) of infants were female, and 39.8% (n = 51) of mothers reported having single-headed households. Participating mothers also reported on the education levels of the fathers of their children. Of those who knew the education level of their child’s father (25.8% were not aware), mothers reported that 26.3% (n = 25) of fathers completed high school/GED, 43.2% (n = 41) vocational school, and 30.5% (n = 29) received partial/full college education.

Families were assessed at baseline when infants were 12 months old and again at ages 14, 16, 24, and 36 months of age (present study utilized data from 12-, 24-, and 36-month assessments). Informed consent for participation was obtained from mothers prior to the initiation of data collection, and the research was conducted in compliance with the university Institutional Review Board. Participating mothers and their children completed research visits in their home and the laboratory at each time point included in the current study. Home visits conducted at 24 months of age included a 20-minute free play session. Participants were paid $20-$40 per visit depending on the length and burden of the assessment battery at each visit. Due to potential variability in literacy and reading ability, trained interviewers read all self-report measures aloud, while participants followed along and marked their answers. Retention strategies included the use of location tracking, letter mailing, phone calls, neighborhood canvassing, secondary contacts, seasonal newsletters, and birthday/holiday cards. To remove participation barriers, the study provided childcare for non-participating children, offered flexible visit scheduling, and provided transportation. Retention at Time 5 was 73.5%. The data, analytic code, and study materials are not publicly available. This study was not preregistered.

Measures

Maternal psychopathology.

Maternal MDD and adult ASPD diagnostic status at baseline was assessed using the DIS-IV (Robins et al., 1995). The DIS-IV is a structured interview designed to assess diagnostic criteria for psychiatric disorders, as outlined in DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), with strong psychometric properties (Robins, Helzer, Ratcliff, & Seyfried, 1982). All interviewers were trained to criterion reliability in the administration of the DIS-IV, and computer-generated diagnoses were utilized. In the current sample, 21.3% (n = 26) of mothers met criteria for MDD only, 13.1% (n = 16) for ASPD only, 34.4% (n = 42) for comorbid MDD/ASPD, and 31.1% (n = 38) did not meet criteria for either MDD or ASPD. Maternal ASPD was based on meeting adult diagnostic criteria and was not dependent on childhood conduct disorder per literature suggesting that this qualifier is less predictive of child outcomes than adult symptomatology (Jaffee et al., 2006; McGonigal et al., 2019).

Negative Parenting.

During the 24-month home visit, a trained research assistant videotaped mothers and their child during a 20-minute free play, in which they were provided pre-selected, developmentally appropriate toys. Mothers were requested to interact with their child as they “typically would.” Trained observers used the System for Coding Interactions in Parent-Child Dyads (SCIPD; Lindahl & Malik, 1996) to assess negative parenting during the free play. The SCIPD consists of a set of 5-point global rating scales designed to behaviorally assess parent-child interactions. Raters indicated the degree to which the behavior was characteristic of the parent (or child) during the given interaction. Three observational codes on the SCIPD were used to assess negative parenting in the present study: Rejection-Invalidation, Negative Affect, and Coercive Control. The Rejection-Invalidation code indexed the mother’s overall level of rejection and/or invalidation expressed through tone of voice, facial expressions, and body language when interacting with her child. The Negative Affect code captured the frustration, anxiety, tension, and conflict expressed by the mother during the interaction. Finally, the Coercive Control code assessed the degree to which the mother was domineering or asserted power in an effort to maintain the “upper hand” in the interaction. The primary coder, a doctoral student in clinical psychology, reviewed and coded 100% of the interactions and a trained member of the research staff (master’s degree in a relevant field) coded a randomly selected 20% of tapes for reliability. Raters were unaware of maternal diagnostic status. Raters were aware of the larger RCT study aims from which this data was drawn, but not present study aims. Prior to coding interactions, coders studied the SCIPD manual extensively and completed a small set of reliability training tapes before commencing official coding. Coders met regularly throughout the reliability coding process to consensus ratings and monitor rater drift. Interrater reliability for the three negative parenting codes was calculated based on a single-measurement, consistency, 2-way mixed effects model, which found good reliability for these codes (ICCs = .79-.84).

Maternal efficacy.

Mothers self-reported on their parental efficacy using the Maternal Efficacy Questionnaire (MEQ; Teti & Gelfand, 1991), a 10-item self-report measure that assesses a mother’s feelings of self-efficacy in relation to the specific demands of the parenting role. These 10 items gauge the mother’s sense of her ability to understand her child’s wants and needs, get her child’s attention, engage in positive interaction with her child, appreciate and respond to the child’s preferences, and take care of the child’s basic needs (e.g., “When your child is upset, fussy or crying, how good are you at soothing him or her?”). Teti & Gelfand (1991) previously demonstrated the internal consistency (α = 0.79–0.86) of the MEQ, as well its construct validity via the Sense of Competence subscale of the Parenting Stress Inventory (r = 0.75). The MEQ evidenced good reliability in the present study (α = 0.78).

Parenting Stress.

Participating mothers reported on their perceived parenting stress using the 102-item Parenting Stress Index (PSI; Abidin, 1997). The PSI was developed based upon the theory that stress experienced by a parent is a function of two broad domains: stress around salient characteristics of the child and stress related to situations associated with the caregiving role. The present study captured parenting stress across both domains by using the total score on the PSI in analyses (α = .93). Moreover, the PSI has been demonstrated to have excellent reliability and validity (e.g., Abidin, 1997). The PSI also yields a distinct life stress scale, which captures a range of environmental stressors related to family composition (e.g., divorce/separation), financial stressors, stressful transitions, relational stressors, and legal problems. This scale was used to account for life stress occurring at child ages 18-24-months.

Maternal sensitivity.

Experimenters who worked closely and consistently with the family completed the Maternal Behavior Q-Set (MBQ; Pederson & Moran, 1995). The MBQ consists of 90 items that assess features of maternal sensitivity in relating to the child. Sensitive maternal behaviors indexed by the MBQ include responsivity to child signals, attending to the child under competing demands, realistic expectations about child emotion regulation, synchronous interactions around child tempo and mood, scaffolding child attention and exploration, and the capacity to accept child behavior even if it is not consistent with parental desires (Pederson et al., 1999). Trained observers use a forced distribution to sort the 90 items into nine piles according to how characteristic or uncharacteristic the items are of the mother’s behavior. Distribution of items for each mother is correlated with an ideal criterion distribution of maternal sensitivity to derive a score ranging from −1 (least sensitive) to 1 (prototypically sensitive).

Child Emotional/Behavioral Problems.

The present study utilized both maternal report and trained observer ratings to assess children’s emotional and behavioral problems. The Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL 1.5-5; Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000), a widely used, norm-referenced measure was used as a maternal report of child behavior. The CBCL is comprised of 99 items which are rated 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat or sometimes true), or 2 (very true or often true). The CBCL yields two broad subscales that were used in the current study: internalizing and externalizing problems. The internalizing scale captures problems that are primarily within the self (e.g. “Unhappy, sad, or depressed”), whilst the externalizing scale captures problems involving conflicts with others and expectations for the child (e.g. “Temper tantrums or hot temper”). Previous work (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2000) has shown the CBCL to have strong psychometric properties, including test-retest reliability (r > 0.62 - 0.92) and cross-informant agreement (mean mother-father r = 0.61, mean parent-child care provider r = 0.65).

Regarding observational measures of children’s emotional and behavioral problems, the present study utilized the Withdrawal and Oppositionality/Defiance child codes of the System for Coding Interactions in Parent-Child Dyads (SCIPD). The Withdrawal and Oppositionality -Defiance codes were rated by observing the child’s tone of voice, facial expressions, and body language during the same home-based, free play interaction as described above. Interrater reliability for the withdrawn and oppositionality codes was good (ICC =.75 and .78 respectively).

A baseline (age 12-months) assessment of child behavioral symptoms was obtained using the Infant-Toddler Social Emotional Assessment (ITSEA; Carter & Briggs-Gowan, 2000), a 195-item parental report measure designed to assess a variety of behavioral problems and competencies in children 12-36 months. The ITSEA has acceptable internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and validity relative to the CBCL (Briggs-Gowan et al., 2004). Internalizing and externalizing scales were used to control for baseline symptoms.

Depression Severity.

The Beck Depression Inventory II (BDI-II; Beck et al., 1996) was also used for descriptive purposes to assess maternal depressive symptom severity across each of the four diagnostic groups (see Table 1). The present study relied on a sum score of all 21 items (α = 0.94). The BDI-II demonstrates good internal consistency and validity (Dozois et al., 1998).

Data analytic plan

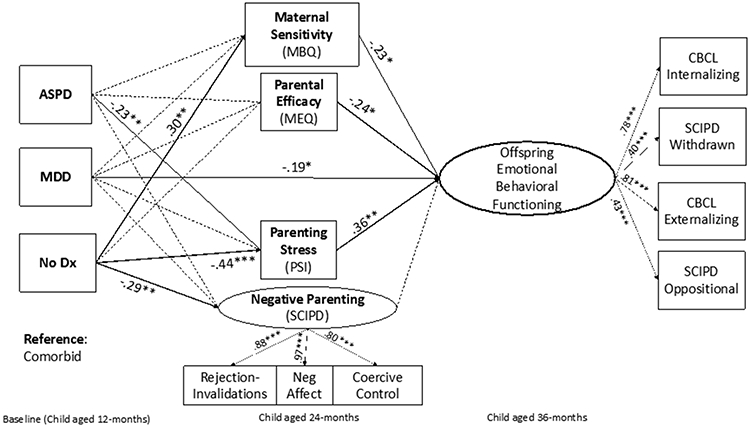

Descriptive data analyses were conducted using SPSS 25 and the proposed models were tested within a Structural Equation Model (SEM) framework using Mplus Version 8.3 (Muthén & Muthén, 2019). The SEM was specified as illustrated in Figure 1a. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to test the latent factor structure for negative parenting (indicated by observed maternal rejection-invalidation, negative affect, and coercive control) and child emotional/behavioral functioning (indicated by observed and maternal report of child internalizing and externalizing symptoms). Results of the measurement model informed specification within the SEM. Dummy-coded maternal psychopathology variables (ASPD only, MDD only, comparison mothers without either diagnosis) were used as exogenous predictors with comorbid MDD/ASPD as the reference group. Maternal efficacy, parenting stress, sensitivity, and negative parenting were specified as mediators of the relation between maternal psychopathology group and the latent outcome of child emotional/behavioral functioning. Residual correlations were modeled among all mediators and between the two observer-rated and parent-reported indicators of child emotional/behavioral functioning. Maternal education, the PSI-Life Stress scale, and baseline child internalizing and externalizing symptoms were modeled as covariates predicting all mediators and outcomes. Given that negative parenting was hypothesized as the only unique mechanism, we also elected to test the influence of negative parenting in a single-mediator model as part of our analysis. Missing data for endogenous variables were estimated as a function of exogenous variables based on the missing at random assumption (Schafer & Graham, 2002). Variables were missing on less than 5% for maternal efficacy and parenting stress, less than 10% for maternal sensitivity, negative parenting indicators, and parent-reported child symptoms, and on 17% of the observed child symptoms.

Figure 1a. Results of structural equation model with comorbid MDD/ASPD group as the reference group.

Notes. Standardized path coefficients are reported. Dashed lines indicate non-significant paths. Dummy variables are included as set, with scores of 1 representing the indicated psychopathology group for each respective code. The following are modeled but not depicted for visual clarity: direct paths from psychopathology groups to child outcomes; paths from covariates to all endogenous variables; residual correlations among all mediating variables. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Model fit for the CFA and the structural model was evaluated using χ2, RMSEA, CFI, and SRMR. Non-significant values of χ2, CFI values greater than .95, RMSEA values less than .06, and SRMR values less than .08 were considered indications of good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Mediation was tested using the distribution of the product method with 95% asymmetric confidence intervals (CIs) via RMediation (Tofighi & MacKinnon, 2011). Confidence intervals that did not include the value of zero determined significant mediation.

Results

Supplemental Table 1 includes descriptive statistics for study variables. As determined by a one-way ANOVA F (3, 121) = 136.70, p < .001, BDI-II scores did not significantly differ between mothers in the MDD-only (M = 29.31) and comorbid (M = 33.12) groups, but both groups had significantly higher scores than the ASPD-only (M = 6.63; Bonferonni, p < .001) and comparison mothers (M = 4.61; Bonferonni, p < .001). Maternal groups did not significantly differ on single parenthood, number of children, race/ethnicity, child sex, or income. Participants in the comorbid group had less educational attainment than those in the ASPD-only group (Bonferonni, p < .04) and more life stress than those with MDD-only (Bonferonni, p =.02).

CFA results confirmed a two-factor model χ2(11) = 8.77, p = .64, RMSEA=.00 (90% CI: .00-.08), CFI=1.00, SRMR=.02, with statistically significant factor loadings for negative parenting (λ = .80—.97, p < .001) and child emotional/behavioral functioning (λ = .46—.77, p <.001). Fit indices for the SEM indicated good fit χ2(61) = 70.851, p = .18, RMSEA=.04 (90% CI: .00-.07), CFI=.98, SRMR=.04 (see Figure 1a for graphical representation of model and results; see Table 2 for bivariate correlation matrix). The children of mothers with MDD-only exhibited less problematic emotional and behavioral functioning when compared to the children of mothers with comorbid MDD/ASPD (β = −.19, p = .04; b = −3.9 [SE =1.9]). However, there were no significant differences on child functioning when comparing mothers with ASPD-only or comparison mothers. Mothers with comorbid MDD/ASPD and MDD-only did not demonstrate significantly different levels of maternal efficacy, parenting stress, maternal sensitivity, or negative parenting—although this effect was approaching significance (β = −.19, p = .07; b = −.51 [SE =.29]). Mothers with ASPD-only reported significantly less parenting stress (β = −.23, p = .005; b = −31.0 [SE =11.0]) than mothers with comorbid MDD/ASPD but were not significantly different in terms of negative parenting, maternal sensitivity, or maternal efficacy. Comparison mothers demonstrated less parenting stress (β = −.44, p < .001; b = −43.6 [SE = 9.0]), greater maternal sensitivity (β = .30, p = .006; b = .25 [SE =.10]), and less negative parenting (β = −.29, p = .01; b = −.70 [SE =.28]) compared to mothers with comorbid MDD/ASPD, with no significant difference between the two groups on maternal efficacy. Among covariates, maternal education predicted negative parenting (β = −.21, p = .04; b = −.13 [SE =.06]), and baseline childhood externalizing symptoms predicted greater parenting stress (β = .22, p = .01; b = 31.7 [SE =12.9]).

Table 2.

Correlations.

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Maternal Efficacy (MEQ) | - | ||||||||||||

| 2. Maternal Sensitivity (MBQ) | .22* | - | |||||||||||

| 3. Parenting Stress (PSI) | −.58** | −.38*** | - | ||||||||||

| 4. Rejection-Invalidations (SCIPD) | −.15 | −.31*** | .29** | - | |||||||||

| 5. Coercive Control (SCIPD) | −.11 | −.24* | .26** | .70*** | - | ||||||||

| 6. Negative Affect (SCIPD) | −.13 | −.40*** | .26** | .85*** | .78*** | - | |||||||

| 7. Child Withdrawn (SCIPD) | −.07 | −.31** | .25** | .06 | .16 | .17 | - | ||||||

| 8. Child Oppositionality (SCIPD) | −.18 | −.31** | .31** | .18 | .22* | .20* | .60*** | - | |||||

| 9. Child Externalizing (CBCL) | −.42*** | −.38*** | .56*** | .27** | .25** | .29** | .36*** | .38*** | - | ||||

| 10. Child Internalizing (CBCL) | −.40*** | −.27** | .58** | .20* | .14 | .16 | .28** | .30** | .71*** | - | |||

| 11. Baseline Child Intx (ITSEA) | −.25** | −.05 | .33*** | .14 | .08 | .07 | .22* | .21* | .23* | .45*** | - | ||

| 12. Baseline Child Ext (ITSEA) | −.25** | −.18 | .40*** | .13 | .12 | .08 | .12 | .17 | .38*** | .32*** | .53*** | - | |

| 13. Life Stress | −.06 | −.06 | .18 | .23* | .22* | .18 | .17 | .14 | .35*** | .27** | .08 | .10 | |

| 14. Maternal Education (yrs) | .18* | .24* | −.28** | .24* | −.27** | −.25** | −.14 | −.18 | −.10 | −.20* | −.32*** | −.22* | −.04 |

p <.05

p < .01

p < .001.

Child emotional/behavioral problems at 36-months were significantly related to lower maternal sensitivity (β = −.23, p = .02; b = −4.9 [SE =2.0]), lower maternal efficacy (β = −.24, p = .01; b = −.61 [SE =.25]), greater parenting stress (β = .36, p = .002; b = .07 [SE =.02]), and greater environmental stress (β = .24, p = .002; b = .21 [SE =.07]), but they were not significantly predicted by negative parenting. Greater parenting stress significantly mediated the effect of exposure to comorbid maternal MDD/ASPD (vs. ASPD) on poorer child emotional/behavioral functioning (95% CI [LCL = −.173, UCL = −.016]). The effect of maternal comorbid MDD/ASPD on child emotional/behavioral problems (vs. comparison mothers) was mediated by less sensitivity (95% CI [LCL = −.158, UCL = −.005]) and greater parenting stress (95% CI [LCL = −.287, UCL = −.051]). The following residual correlations were significant: maternal efficacy with parenting stress (β = −.22, p = .01; b = −54.8 [SE =11.4]); negative parenting with maternal sensitivity (β = −.32, p = .001; b = −.12 [SE =.04]); maternal sensitivity with parenting stress (β = −.22, p = .01; b = −2.9 [SE =.11]).

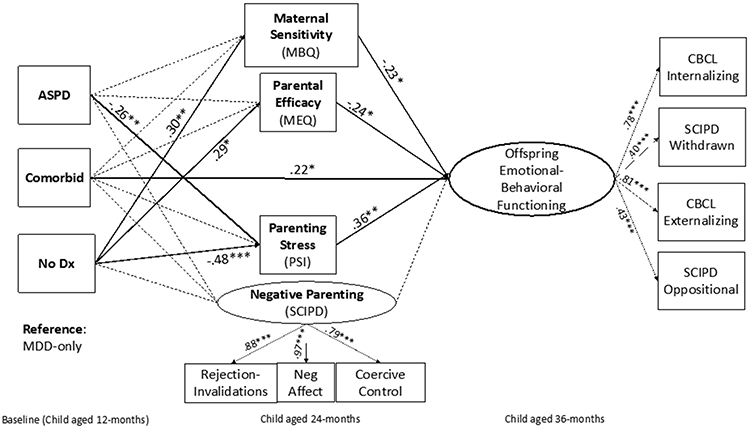

Maternal MDD

The SEM was re-specified with an alternative set of maternal psychopathology dummy codes, positioning mothers with MDD-only as the reference group to compare MDD-only to ASPD-only and comparisons (see Figure 1b). Contrasted with comparison mothers, mothers with MDD-only were less sensitive in parenting interactions (β = .30, p = .008; b = .25 [SE =.10]), and reported more parenting stress (β = −.48, p < .001; b = −47.8 [SE =9.2]), and lower maternal efficacy (β = .29, p = .01; b = 2.1 [SE =.83]), but they did not significantly differ on negative parenting. These differences resulted in significant indirect effects from maternal MDD (vs. comparison) exposure to poorer child emotional/behavioral functioning via greater parenting stress (95% CI [LCL = −.311, UCL = −.057]), lower maternal efficacy (95% CI [LCL = .026, UCL = .221]), and lower maternal sensitivity (95% CI [LCL = −.159, UCL = .004]). Mothers with MDD-only reported greater parenting stress compared to mothers with ASPD-only (β = −.26, p = .003; b = −35.2 [SE =12.0]), which accounted for a significant indirect effect on poorer child emotional/behavioral functioning (95% CI [LCL = −.193, UCL = −.02]).

Figure 1b. Results of structural equation model with MDD-only group as the reference group.

Notes. Standardized path coefficients are reported. Dashed lines indicate non-significant paths. Dummy variables are included as set, with scores of 1 representing the indicated psychopathology group for each respective code. The following are modeled but not depicted for visual clarity: direct paths from psychopathology groups to child outcomes; paths from covariates to all endogenous variables; residual correlations among all mediating variables. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Negative parenting

Negative parenting did not uniquely influence child outcomes in the multiple-mediator model. Given the robust literature on the effect of negative parenting on child emotional/behavioral problems (e.g., Joussemet et al., 2008), as well as the significant zero-order correlations between the individual indicators of negative parenting and child emotional/behavioral problems, we tested a model that trimmed maternal efficacy, parenting stress, and maternal sensitivity, while retaining negative parenting as the sole mediator. This model fit the data well χ2 (41) = 48.50, p = .20, RMSEA=.04 (90% CI: .00-.08), CFI=.98, SRMR=.05. Comorbid MDD/ASPD (vs. comparison mothers) was indirectly related to greater child emotional/behavioral problems via more negative parenting (95% CI [LCL = −.174, UCL = −.007]). There were no other significant indirect effects when comparing maternal groups.

Post-hoc analyses

Due to the lower factor loadings of the two observed child behaviors, which may bias estimates of indirect effects (Rhemtulla et al., 2020), we conducted post-hoc analyses to observe effects for each child outcome. Specifically, we specified models with each of the four child outcomes (SCIPD-Withdrawn, SCIPD-Oppositional, CBCL-Internalizing, CBCL-Externalizing) as manifest variables and the general pattern of findings remains the same (see supplemental material). Notably, this analytic approach yields informant-dependent effects. Maternal-reported parenting mediators (i.e., maternal efficacy and parenting stress) significantly predicted maternal-reported child symptoms (i.e., internalizing and externalizing). Conversely, observer-rated parenting behavior (i.e., maternal sensitivity) significantly predicted observer-rated child symptoms (i.e., withdrawn and oppositional behavior). This is not surprising, given the well-documented evidence that relying on single sources of information for parenting behavior and child outcomes can bias and inflate estimates, especially in clinical samples (e.g., Olino et al., 2021). Thus, we elected to present a primary model containing a multi-informant latent variable of child behavior that identifies what is shared across informants and minimizes reporter bias.

Discussion

Current findings contribute to a growing understanding of whether and why comorbid maternal MDD/ASPD is linked to elevated risk for child emotional/behavioral problems in early childhood. We constructed a mediational model to prospectively test whether comorbid maternal MDD/ASPD occurring during the postnatal period differentially affected children’s emotional and behavioral problems at age three (relative to maternal MDD-only, ASPD-only, and no MDD/ASPD), and whether four aspects of parenting (i.e., maternal sensitivity, negative parenting, maternal efficacy, and overall parenting stress) uniquely mediated any associations.

Direct effects

Consistent with previous literature, our findings demonstrate that children exposed to comorbid maternal MDD/ASPD exhibited greater emotional/behavioral problems than children exposed to MDD-only, indicating a particularly high-risk group of children (Conroy et al., 2012; Kim-Cohen et al., 2006; Sellers et al., 2013). These findings are consistent with the notion of cumulative risk (Rutter, 1979; Sameroff et al., 2003), in which the number of present risk factors is more predictive of child psychopathology than the particular type of risk factor. When maternal depression is the sole risk factor, children may be able to withstand adverse conditions; however, when another psychopathological condition is added, the family context may be overwhelmed and unable to fully shield children from the deleterious impact of complex maternal symptoms (Carter et al., 2001; McLaughlin et al., 2013; Sameroff et al., 2003).

Parenting Mechanisms

Although comorbid maternal MDD/ASPD was associated with distinctly greater risk for child emotional/behavioral problems relative to MDD-only, the modeled set of parenting mediators did not account for this direct effect. However, common and disorder-specific parenting mechanisms were revealed that help explain how maternal MDD/ASPD and MDD-only may be linked to negative child outcomes, when compared to children of mothers with ASPD-only or neither diagnosis. Contrasted with comparison families, maternal MDD-only and comorbid MDD/ASPD both appear to increase risk for child problems as a function of greater parenting stress and lower maternal sensitivity, respectively. This is consistent with independent lines of research demonstrating that the effects of both maternal MDD and ASPD are related to maladaptive child outcomes via a lack of sensitivity (Goodman et al., 2017; Milgrom et al., 2010) and greater parenting stress (Fredriksen et al., 2019; Thornberry et al., 2009). Young children are highly dependent on caregivers to support their emotional development (e.g., emotion regulation) through dyadic co-regulation of emotional states and consistent modeling of regulatory skills, which requires sensitive, attuned parenting (Kok et al., 2013). Thus, the children of parents who are highly stressed and less sensitive in their caregiving are at greater risk of developing psychopathology.

Unique differences also emerged. Lower maternal efficacy was a unique mechanism explaining the greater emotional/behavioral symptoms observed in children of mothers with MDD-only (vs. comparison mothers). Given the strong association between maternal depression and low maternal efficacy (Goodman, 2020), we expected this to be a common feature of mothers with isolated and comorbid MDD. It is possible that hallmark features of ASPD, such as callousness and remorselessness, counteract the prominent aspects of depression that may contribute to diminished maternal efficacy (e.g., negative processing biases and self-schemas).

We also found that mothers with comorbid MDD/ASPD uniquely exhibited more negative parenting behavior than comparison mothers. This is consistent with previous literature demonstrating that the presumed “depression effect” linking maternal depression to negative or hostile parenting may be better accounted for by comorbid maternal disorder, rather than depression per se (Carter et al., 2001; Kim-Cohen et al., 2006; Sellers et al., 2014). Additional work is needed to understand distinct subtypes of depressed mothers (i.e., those with comorbid ASPD) who may present with unique profiles of parenting behaviors. Contrary to previous findings (e.g., Kim-Cohen et al., 2006), mothers with MDD-only and comorbid MDD/ASPD did not significantly differ in negative parenting behavior, although the effect was approaching significance. Consistent with other studies (Kim-Cohen et al., 2006; Jaffee et al., 2006), we found that mothers with comorbid MDD/ASPD had significantly lower levels of educational attainment than mothers with MDD-only, and lower educational attainment significantly predicted negative parenting in our model. This finding highlights the importance of considering educational differences when comparing mothers with MDD and comorbid MDD/ASPD.

We find support for negative parenting as a unique mechanism that may link maternal comorbid MDD/ASPD to greater child emotional/behavioral problems, consistent with previous findings (Sellers et al., 2014). The effect of negative parenting was attenuated in the multiple-mediator model that simultaneously accounted for distinct, but interrelated parenting factors. This pattern of findings implies that the mechanistic effect of negative parenting may reflect variance in child outcomes that is overlapping or shared with parenting stress, self-efficacy, and sensitivity (MacKinnon & Fairchild, 2009).

Alternative Pathways

There are several plausible mechanisms, not included in this study, that may explain why children exposed to comorbid MDD/ASPD exhibit poorer emotional/behavioral outcomes than children exposed to maternal depression (i.e., the direct effect in our model), including genetic transmission or partner effects (e.g., assortative mating, paternal psychopathology, and interparental conflict; Cummings & Davies, 1994). Genetics can play a prominent role in transmitting psychopathology risk from mother to child (Harold et al., 2011), and the children of mothers with comorbid MDD/ASPD may carry a higher genetic loading for general emotional/behavioral problems. Although this is a parsimonious explanation, environmental mechanisms also account for the transmission of psychopathology risk, over and above heritability (Harold et al., 2011; Silberg et al., 2012). Also, genetic risks may operate via environmental mechanisms through various forms of gene-environment correlations (rGE; Gotlib et al., 2020). Our findings should be replicated with genetic designs (Harold et al., 2012).

Assortative mating has also been proffered as a mechanism accounting for the link between child psychopathology and maternal MDD/ASPD (Goodman et al., 2014; Krueger et al., 1998). Mothers with MDD or ASPD are more likely to partner or cohabitate with individuals who have their own MDD and/or ASPD symptoms, which may contribute to or exacerbate the development of psychopathology for children by increasing genetic risk, and/or contributing to adverse caregiving environments (e.g., suboptimal parenting or family violence; Cummings & Davies, 1994). In our study, mothers with comorbid MDD/ASPD may have been most likely to engage in assortative mating with partners exhibiting depression, antisocial behaviors, or both, conferring cumulative risk to children. Future studies examining the intergenerational risk mechanisms related to maternal depression that co-occurs with antisociality should also test the mediating or moderating roles of paternal psychopathology/parenting and family violence.

Strengths and limitations

This investigation includes several strengths, including a prospective, longitudinal design; a sophisticated analytic approach to assessing multiple mediators; and a multi-informant, multi-method approach and rigorous assessment (e.g., diagnostic interviews). Multi-informant data on mothers’ and children’s functioning reduces the risk of reporting bias (e.g., negativity, recency, and social desirability biases) while balancing the benefits of maternal report. Drawing on a range of informants, we were able to emphasize rater-independent associations in the path modeling of intergenerational processes, limiting the chance of inflated effects from overreliance on the same reporter for maternal and child variables (Goodman et al., 2011). This study also focused on families living in economically-disadvantaged contexts to account for the confounding role of unequitable sociodemographic differences.

Several limitations also must be noted. Due to the small number of cases with ASPD-only, we may have been underpowered to identify small effects involving this group. We intentionally focused on co-occurring ASPD, but other common MDD comorbidities, such as maternal anxiety or substance use (Goodman, 2020), are worthy of study. Although our diverse set of parenting constructs was a novel contribution, our list of mechanisms was not exhaustive, and future studies should explore other environmental mechanisms (e.g., family violence) specifically linking comorbid maternal MDD/ASPD to offspring outcomes. Future studies of high-risk samples should also consider the common occurrence of traumatic exposures for both mother and child, including how trauma may influence parenting behaviors/cognitions and the development of child socioemotional difficulties. We were unable to control for baseline parenting, possibly confounding mediation effects (Cole & Maxwell, 2003). Although observer-rater behavior is a strength, we cannot rule out observer implicit biases. Finally, we hypothesized a unidirectional model to explain parent effects on children, yet it is also possible that parent- and child-directed effects unfold in a bidirectional, transactional manner (Belsky, 1984).

Implications

Our results contribute to decades of research on maternal depression and provide additional insight into the possible nuanced presentation of this disorder and co-occurring ASPD. Further, our findings align with recent recommendations from the American Academy of Pediatrics to address maternal depression during postnatal pediatric well-check visits as an inexpensive way to address intergenerational risk (Rafferty et al., 2019). Although screening for parental mental health in the pediatric setting is not without its challenges, it also represents a real opportunity to dismantle siloed treatment approaches to parent and child mental health and apply a true intergenerational approach to preventing the development of psychopathology. Programs that attend to psychopathology in early childhood should include linked clinical care options that can improve child outcomes by minimizing maternal psychopathology and improving parenting behavior (Handley et al., 2017; Zalewski et al., 2017). Moreover, such parenting interventions should consider the heterogeneity of maternal depression and be multi-faceted in nature, addressing several aspects of the parenting environment (e.g., reducing parental stress, improving parental efficacy, and supporting parents to become more sensitive and less negative in interactions with their children; Toth et al., 2006).

Lastly, fathers make important and unique contributions to the development of socioemotional functioning in early childhood, yet the literature has lagged in the study of paternal depression and its impact on parenting and children. Our study is no different, as fathers were not included in the study design. However, exploration of paternal MDD/ASPD comorbidity is likely worthy of further research because men also experience this comorbidity (Hatchett, 2015) and such conditions may influence their child’s outcomes both directly and indirectly through parenting. Further, a small, but informative body of research suggests both comparable and unique effects of maternal and paternal depression on parenting behaviors (Wilson & Durbin, 2010) and future studies could explore whether the processes discussed herein differ across mothers and fathers.

Conclusion

Interrupting intergenerational risk processes early in development is paramount to reducing the personal and societal burden of mental health. Maternal depression and associated parenting behavior are well-established as critical targets for early intervention, yet greater attention should be given to the role of depression comorbidities, such as maternal ASPD.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This research was supported by grants received from the National Institute of Mental Health (R01MH067792) and National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (P50-HD096698).

References

- Abidin RR (1997). Parenting Stress Index: A measure of the parent-child system. In Zalaquett CP & Wood R (Eds.), Evaluating stress: A book of resources (pp. 277–291). Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. 10.1017/S0033291798257163 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, & Rescorla LA (2000). Manual for the ASEBA Preschool Forms and Profiles: An integrated system of multi-informant assessment. Burlington: Department of Psychiatry, University of Vermont. [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Steer RA, & Brown GK (1996). Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corporation. 10.1037/t00742-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Belsky J (1984). The determinants of parenting: A process model. Child Development, 55(1), 83–96. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1984.tb00275.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosquet M, & Egeland B (2000). Predicting parenting behaviors from antisocial practices content scale scores of the MMPI-2 administered during pregnancy. Journal of Personality Assessment, 74(1), 146–162. 10.1207/S15327752JPA740110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter AS, Garrity-Rokous FE, Chazan-Cohen R, Little C, & Briggs-Gowan MJ (2001). Maternal depression and comorbidity: predicting early parenting, attachment security, and toddler social-emotional problems and competencies. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(1), 18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L, Schwartz D, Dodge KA, & McBride-Chang C (2003). Harsh parenting in relation to child emotion regulation and aggression. Journal of Family Psychology, 17(4), 598. 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings EM, & Davies PT (1994). Maternal depression and child development. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 35(1), 73–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, & Toth SL (1998). The development of depression in children and adolescents. American Psychologist, 53(2), 221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Rogosch FA, & Toth SL (1998). Maternal depressive disorder and contextual risk: Contributions to the development of attachment insecurity and behavior problems in toddlerhood. Development and Psychopathology, 10(2), 283–300. 10.1017/s0954579498001618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR, Bayon CARMEN, & Przybeck TR (1997). Epidemiology and Axis I comorbidity of antisocial personality. Handbook of antisocial behavior. In Stoff D, Breiling J (eds.), Handbook of antisocial behavior (pp. 12–21) Wiley & Sons: New York. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman PK, & Karraker KH (1998). Self-efficacy and parenting quality: Findings and future applications. Developmental Review, 18(1), 47–85. 10.1006/drev.1997.0448 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy S, Pariante CM, Marks MN, Davies HA, Farrelly S, Schacht R, & Moran P (2012). Maternal psychopathology and infant development at 18 months: the impact of maternal personality disorder and depression. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(1), 51–61. 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies PT, Sturge-Apple ML, Cicchetti D, Manning LG, & Vonhold SE (2012). Pathways and processes of risk in associations among maternal antisocial personality symptoms, interparental aggression, and preschooler's psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 24(3), 807–832. 10.1017/S0954579412000387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dozois DJA, Dobson KS, & Ahnberg JL (1998). A psychometric evaluation of the Beck Depression Inventory-II. Psychological Assessment, 10, 83–89. 10.1037/1040-3590.10.2.83 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ertel KA, Rich-Edwards JW, & Koenen KC (2011). Maternal depression in the United States: Nationally representative rates and risks. Journal of Women's Health, 20(11), 1609–1617. 10.1089/jwh.2010.2657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredriksen E, von Soest T, Smith L, & Moe V (2019). Parenting stress plays a mediating role in the prediction of early child development from both parents’ perinatal depressive symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 47(1), 149–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Q, Heath AC, Bucholz KK, Nelson E, Goldberg J, Lyons MJ, … & Eisen SA (2002). Shared genetic risk of major depression, alcohol dependence, and marijuana dependence: contribution of antisocial personality disorder in men. Archives of General Psychiatry, 59(12), 1125–1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH (2020). Intergenerational transmission of depression. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 16, 213–238. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-071519-113915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth MR, Hall CM, & Heyward D (2011). Maternal depression and child psychopathology: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14(1), 1–27. 10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman SH, Bakeman R, McCallum M, Rouse MH, & Thompson SF (2017). Extending models of sensitive parenting of infants to women at risk for perinatal depression. Parenting, 17(1), 30–50. 10.1080/15295192.2017.1262181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Joormann J, & Foland-Ross LC (2014). Understanding familial risk for depression: A 25-year perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9(1), 94–108. 10.1177/1745691613513469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Handley ED, Michl-Petzing LC, Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D, & Toth SL (2017). Developmental cascade effects of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed mothers: Longitudinal associations with toddler attachment, temperament, and maternal parenting efficacy. Development and Psychopathology, 29(2), 601–615. 10.1017/S0954579417000219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harold GT, Elam KK, Lewis G, Rice F, & Thapar A (2012). Interparental conflict, parent psychopathology, hostile parenting, and child antisocial behavior: Examining the role of maternal versus paternal influences using a novel genetically sensitive research design. Development and Psychopathology, 24(4), 1283–1295. 10.1017/S0954579412000703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatchett G (2015). Treatment guidelines for clients with antisocial personality disorder. Journal Mental Health Counseling, 37(1), 15–27. DOI: 10.17744/mehc.37.1.52g325w385556315 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, & Bentler PM (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Belsky J, Harrington H, Caspi A, & Moffitt TE (2006). When parents have a history of conduct disorder: How is the caregiving environment affected? Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 115(2), 309–319. 10.1037/0021-843X.115.2.309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joussemet M, Vitaro F, Barker ED, Côté S, Nagin DS, Zoccolillo M, & Tremblay RE (2008). Controlling parenting and physical aggression during elementary school. Child Development, 79(2), 411–425. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01133.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Rutter M, Tomás MP, & Moffitt TE (2006). The caregiving environments provided to children by depressed mothers with or without an antisocial history. American Journal of Psychiatry, 163(6), 1009–1018. 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger RF, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Bleske A, & Silva PA (1998). Assortative mating for antisocial behavior: Developmental and methodological implications. Behavior Genetics, 28(3), 173–186. 10.1023/A:1021419013124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl KM, & Malik NM (1996). System for Coding Interactions in Parent-Child Dyads (SCIPD): A coding system for structured and unstructured parent-child tasks. Unpublished manuscript, University of Miami. [Google Scholar]

- Lindahl KM, & Malik NM (2000). The system for coding interactions and family functioning. In Family observational coding systems (pp. 91–106). Psychology Press. 10.4324/9781410605610 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luby JL, Gaffrey MS, Tillman R, April LM, & Belden AC (2014). Trajectories of preschool disorders to full DSM depression at school age and early adolescence: Continuity of preschool depression. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(7), 768–776. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13091198 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, & Fairchild AJ (2009). Current directions in mediation analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 18(1), 16–20. 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2009.01598.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik NM, & Lindahl KM (2004). System for coding interactions in dyads (SCID). In Couple Observational Coding Systems (pp. 173–189). Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. 10.4324/9781410610843 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McGonigal P, Kerr S, Morgan T, Dalrymple K, Chelminski I, & Zimmerman Z (2019). Should childhood conduct disorder be necessary to diagnose antisocial personality disorder in adults? Annals of Clinical Psychiatry, 31(1), 36–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michl LC, Handley ED, Rogosch F, Cicchetti D, & Toth SL (2015). Self-criticism as a mechanism linking childhood maltreatment and maternal efficacy beliefs in low-income mothers with and without depression. Child Maltreatment, 20(4), 291–300. 10.1177/1077559515602095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milgrom J, Newnham C, Anderson PJ, Doyle LW, Gemmill AW, Lee K, … & Inder T (2010). Early sensitivity training for parents of preterm infants: Impact on the developing brain. Pediatric Research, 67(3), 330–335. 10.1203/PDR.0b013e3181cb8e2f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén BO, Muthén LK, & Asparouhov T (2017). Regression and mediation analysis using Mplus. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén [Google Scholar]

- Neece CL, Green SA, & Baker BL (2012). Parenting stress and child behavior problems: A transactional relationship across time. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 117(1), 48–66. 10.1352/1944-7558-117.1.48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olino TM, Michelini G, Mennies RJ, Kotov R, & Klein DN (2021). Does maternal psychopathology bias reports of offspring symptoms? A study using moderated non linear factor analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 62(10), 1195–1201. 10.1111/jcpp.13394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postpartum Depression: Action Towards Causes and Treatment (PACT) Consortium (2015). Heterogeneity of postpartum depression: A latent class analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(1), 59–67. 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00055-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pederson DR, & Moran G (1995). A categorical description of infant–mother relationships in the home and its relation to Q-sort measures of infant–mother interaction. Monographs of the SRCD, 60, 111–132. 10.2307/1166174 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pederson DR, Moran G, & Bento S (1999). Maternal behaviour Q-sort. Psychology Publications, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Robins LN, Cottler L, Bucholz K, & Compton W (1995). Diagnostic Interview Schedule for DSM–IV. St. Louis, MO: Washington University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M (1979). Protective factors in children’s responses to stress and disadvantage. In Kent MW & Rolf JE (Eds.), Primary prevention in psychopathology. Vol. 8: Social competence in children (pp. 49–74). Hanover, NH: University Press of New England. 10.1176/ps.31.4.279-a [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer KM, Zunszain PA, Dazzan P, & Pariante CM (2019). Intergenerational transmission of depression: Clinical observations and molecular mechanisms. Molecular Psychiatry, 24(8), 1157–1177. 10.1038/s41380-018-0265-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, & Graham JW (2002). Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods, 7(2), 147. 10.1037/1082-989X.7.2.147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers R, Collishaw S, Rice F, Thapar AK, Potter R, Mars B, … & Thapar A (2013). Risk of psychopathology in adolescent offspring of mothers with psychopathology and recurrent depression. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 202(2), 108–114. 10.1192/bjp.bp.111.104984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sellers R, Harold GT, Elam K, Rhoades KA, Potter R, Mars B, … & Collishaw S (2014). Maternal depression and co-occurring antisocial behaviour: Testing maternal hostility and warmth as mediators of risk for offspring psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(2), 112–120. 10.1111/jcpp.12111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shay NL, & Knutson JF (2008). Maternal depression and trait anger as risk factors for escalated physical discipline. Child Maltreatment, 13(1), 39–49. 10.1177/1077559507310611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silberg JL, Maes H, & Eaves LJ (2012). Unraveling the effect of genes and environment in the transmission of parental antisocial behavior to children’s conduct disturbance, depression and hyperactivity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(6), 668. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02494.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teti DM, & Gelfand DM (1991). Behavioral competence among mothers of infants in the first year: The mediational role of maternal self-efficacy. Child Development, 62, 918. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1991.tb01580.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Freeman-Gallant A, & Lovegrove PJ (2009). Intergenerational linkages in antisocial behaviour. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 19(2), 80–93. 10.1002/cbm.709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tofighi D, & MacKinnon DP (2011). RMediation: An R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behavior Research Methods, 43(3), 692–700. 10.3758/s13428-011-0076-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth SL, Rogosch FA, Manly JT, & Cicchetti D (2006). The efficacy of toddler-parent psychotherapy to reorganize attachment in offspring of mothers with major depressive disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(6), 1006. 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toth ST, Rogosch FA, Oshri A, Gravener-Davis J, Sturm R, & Morgan-López AA (2013). The efficacy of interpersonal psychotherapy for depression among economically disadvantaged mothers. Development and Psychopathology, 25, 1065–1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trentacosta CJ, & Shaw DS (2008). Maternal predictors of rejecting parenting and early adolescent antisocial behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 36(2), 247–259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.