Abstract

Although it is widely accepted that exchange rates are connected, what drives these connections remains an unsettled question. We examine the interconnections and spillovers of G10 currencies over the period from January 1, 2018 to June 17, 2021. We find that the Euro and Australian dollar serve as risk transmitters whereas the Japanese yen operates as a risk recipient. During the COVID-19 pandemic period, countries with higher infection cases experience currency depreciation and transmit more currency risk to others. In response to this crisis, the Fed adopted the large-scale asset purchase program that weakened the USD and increased the demand for high-yield currencies through the portfolio rebalancing channel. The appreciation of high-yield currencies further attracts carry trades and enhances their risk transmission to low-yield currencies. Furthermore, we provide evidence to show that the COVID-19 infection cases, the Fed's policy, and carry trades are crucial determinants of exchange rate spillovers.

Keywords: Connectedness, COVID-19 pandemic, Unconventional monetary policy, G10 currencies

1. Introduction

COVID-19 has undoubtedly created an unprecedented shock on the global economy and worldwide financial markets. Many countries closed their borders and put a sudden halt on international trading activities. Central banks around the world have imposed conventional and unconventional monetary policies to rescue and stabilize their economies. As a result, it is not clear how the foreign exchange (FX) markets behave given simultaneous shocks to international trade, financial markets, and monetary policies. Given that major currencies are connected, can FX risk spill over from one currency to another and what is the driving force?

We analyze the connectedness among G10 currencies and investigate the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and U.S. monetary policy on the dynamic return connectedness. G10 currencies are crucial because they are among the most traded and used in cross-border transactions and international portfolio investments.1 Using returns and risk premiums of G10 currency pairs, we employ the connectedness measure of Diebold and Yilmaz (2012, 2014) based on forecast error variance decompositions from vector autoregression (VAR). We further adopt the rolling-window estimation to capture time variation in connectedness and explore determinants of the total and directional connectedness. In addition, we adopt a difference-in-differences analysis to check whether directional connectedness of high-yield and low-yield currency groups varies before and after changes in the federal funds rate.

Understanding the dynamic connectedness and currency risk spillover among G10 currencies is important for not only academic researchers, but also policymakers, corporations, and investors. Multinational corporations are directly affected by currency connectedness because of their currency conversions and FX hedging activities. International investors who manage currency portfolios to speculate on exchange rate movements, execute carry trade arbitrage, or diversify FX risk should pay close attention to currency co-movements and the transmission of currency risk. The COVID-19 pandemic and the unconventional U.S. monetary policy (i.e., large-scale asset purchases (LSAPs) and forward guidance) adopted in March 2020 jointly presented unprecedented shocks to the global economy.2 As a result, the global FX market has experienced unusual currency spillover patterns. Our findings can thus provide policy implications and be beneficial to policymakers.

The connectedness (or spillover) among currencies has attracted considerable attention in the FX literature.3 Greenwood-Nimmo et al. (2016) study the interaction between FX return and volatility for G10 currencies, while Atenga and Mougoué (2021) investigate similar issues for African currencies. Despite the growing number of studies in this area, key determinants of FX connectedness remain largely unclear. Recent studies indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic can be a potential determinant. Narayan (2021) shows that the COVID-19 pandemic affects exchange rate returns, while Feng et al. (2021) find that an increase in COVID-19 infection cases significantly raised exchange rate volatility. Fu and Yang (2021) further document that relatively high (low) numbers of new COVID-19 infection cases lead to depreciation (appreciation) of the home currency. In addition, the Fed's monetary policy can affect FX connectedness. Neely (2015), Greenwood et al. (2020), and Swanson (2021) show that the Fed's LSAPs cause a depreciation of the U.S. dollar vis-a-vis other major currencies because the Fed's bond purchases reduce U.S. bond yields relative to foreign bond yields.

This study contributes to the literature in several ways. First, this paper is the first to consider the joint effects of the Fed's monetary policy and the COVID-19 pandemic on G10 FX interconnectedness. Existing studies (Baruník et al., 2017; Greenwood-Nimmo et al., 2016; Kočenda and Moravcová, 2019; Wen and Wang, 2020) primarily focus on the connectedness among exchange rates, but we show that the unprecedented shocks from the pandemic and the Fed's unconventional policy exhibit significant impacts on FX interconnectedness and spillover transmission. Second, we show that the different spillover responses of high-yield and low-yield currencies to the Fed's conventional and unconventional monetary policies are closely related to currency carry trade activities and portfolio rebalancing adjustments. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to discover the linkage between currency connectedness and carry trades. Third, with the most updated G10 FX data, we provide a comprehensive analysis to address the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on FX connectedness. Our sample period covers the COVID-19 outbreak, re-infection from COVID -19 mutation, and the removal of government lockdowns. While Narayan (2021) provides a comparative analysis of FX connectedness during and before the coronavirus outbreak, with the extended sample period, we are able to specifically examine the impact of COVID-19 infection cases on FX connectedness.

The COVID-19 pandemic can affect exchange rate returns and volatility. The increasing number of infection cases in one country may contract its economic activities and adversely affect international trades. In addition, in response to the quick spread of cases, governments may adopt serious preventive policies, such as lockdowns, and more stringent regulations to further restrict economic activities. Since exchange rate movements are closely related to economic activities, COVID-19 infection cases are expected to have a significant impact on exchange rates. As the pandemic spreads across the globe, the impact of COVID-19 on one currency may spill over to other currencies, which could potentially lead to intensified global FX systemic risk.

Similarly, the U.S.‘s unconventional monetary policy can affect exchange rates and the connectedness of currencies. While the demand for foreign currencies related to international trades may decrease, FX trading from speculation and hedging activities as well as government interventions could rise given the uncertainty and unconventional monetary policies during the period. Panel A of Fig. 1 clearly shows the depreciation of the U.S. dollar when the Fed's LSAPs started on March 23, 2020.4

Fig. 1.

Time Series of U.S. Dollar Index and Bloomberg G10 FX Carry Trade Index

Notes: FXCTG10 index represents the carry trade returns computed from G10 currency baskets and states in values representing cumulative returns since their inception in 1999 (the index was normalized to 100 in 1999). The vertical red line indicates the occurrence of the first COVID-19 infection case in the U.S. and the shaded area covers the period from March 23, 2020, to May 22, 2020. The Fed announced its intention to use its full range of tools (LSAPs) to support households, businesses, and the U.S. economy overall against the coronavirus pandemic on March 23, 2020.

The connection between FX and COVID-induced monetary policies can be attributed to the portfolio rebalancing channel. Bauer and Neely (2014) point out that the Fed's LSAPs can affect prices of imperfectly substitutable assets through the portfolio rebalancing channel. They find that a purchase of U.S. bonds appears to have a relatively larger portfolio rebalancing effect on Australian bond yield (higher yield) than on Japanese bond yield (lower yield). Engel (2016) further argues that a country with relatively high interest rate has lower risk premium and hence a stronger currency. As a result, high interest rate countries may attract more international investors when market uncertainty is enhanced by the COVID-19 pandemic. Hence, we hypothesize that the Fed's LSAPs will increase the demand for high-yield bonds and, through the portfolio rebalancing channel, cause currencies of high interest-rate countries to appreciate. Consequently, we would expect to observe relatively high directional return spillovers from exchange rates in high-yield countries to those in low-yield countries.

Besides the portfolio rebalancing channel, we believe that the well-known currency carry trade can play an important role in the connectedness among currencies during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to Bekaert and Panayotov (2020) and Abankwa and Blenman (2021), currency carry trade is a trading strategy that consists of selling low interest-rate currencies (funding currencies) and investing in high interest-rate currencies (investment currencies). While the uncovered interest rate parity (UIP) hypothesizes that the carry trade profit due to the interest-rate differential can be offset by a commensurate depreciation of the investment currency, empirically, the reverse may hold (Brunnermeier et al., 2008; Du et al., 2018; Avdjiev et al., 2019). In particular, the Fed's LSAPs cause higher carry trade returns on portfolios that invest in high interest-rate G10 currencies by borrowing low interest-rate currencies. Panel B in Fig. 1 shows that the Bloomberg FX G10 Carry Trade Index rose from 195 on March 23, 2020, to about 210 on May 22, 2020, revealing rising G10 currency carry trade returns after the Fed's LSAPs.5 The increase in G10 currency carry trades creates strong demand for currencies of high interest-rate countries and in turn induces their appreciation, which enhances directional return spillovers from those currencies to low interest-rate currencies.

We evaluate the return and risk premium connectedness among G10 currencies over the full sample period from January 1, 2018, to June 17, 2021. The results reveal significant spillovers among the currencies. Specifically, USD-EUR and USD-AUD exchange rates provide strong directional connectedness to others. The relative disconnect of the USD-JPY exchange rate from other currencies along with strong self-contribution for the USD-JPY support the finding of Greenwood-Nimmo et al. (2016) and the notion that the JPY is a safe haven currency.

We also analyze time variation in the total connectedness using rolling samples of 100 trading days. We find that the total connectedness is positively (negatively) related to the Fed's total assets (federal funds target rate), indicating that FX connectedness strengthens with the U.S.‘s expansionary monetary policy. Many central banks have found themselves increasingly constrained by the zero lower bound in recent years and have turned to a variety of unconventional policies such as LSAPs to stimulate their economies (Swanson, 2021). When the federal funds rate approaches zero, we find the Fed's total assets, which proxies the scale of LSAPs, increases sharply and enhances FX total connectedness. Furthermore, we find that total connectedness increases after the COVID-19 outbreak and during high U.S. VIX periods when the market uncertainty is high.

More importantly, we analyze the dynamic directional connectedness and find that COVID-19 infection cases and the U.S. unconventional policy jointly affect the net directional connectedness among G10 exchange rates. The increase in new COVID-19 infection cases in one country relative to that in the U.S. leads to depreciation of its currency and further strengthens the net directional connectedness which stems from that country to others. This finding suggests that the COVID-19 cases in one country can transmit risk to other countries via exchange rate movements. In addition, the Fed's LSAPs enhance the net directional connectedness that stems from high-yield to low-yield currencies. Likely due to increases in G10 carry trades and FX portfolio rebalances, the demand for high-yield currencies such as AUD, CAD, and NOK jumps, which enhances the directional return spillover from those currencies to others.

To investigate whether the directional connectedness of high-yield and low-yield currency groups varies before and after changes in the U.S. federal funds rate (i.e., conventional monetary policy), we perform a difference-in-differences analysis. We find that the directional connectedness that stems from high-yield currencies is enhanced, relative to low-yield currencies, after rate cuts. However, the directional connectedness that stems from low-yield currencies strengthens relatively after rate hikes. Overall, our results show that the Fed's target rate policy affects the return spillover transmission between high-yield and low-yield currency groups.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides a description of the data. Section 3 introduces the Diebold and Yilmaz connectedness measurement. Section 4 presents empirical results on the connectedness of G10 currency returns and determinants of total and net directional connectedness. Section 5 provides the difference-in-differences analysis for the net directional connectedness of high-yield and low-yield currencies in response to the Fed's monetary policy decisions. Finally, Section 6 concludes.

2. Data

We focus on G10 currencies and thus include the USD-AUD, USD-CAD, USD-CHF, USD-EUR, USD-GBP, USD-JPY, USD-NOK, USD-NZD, and USD-SEK exchange rates in this study. Exchange rates are expressed in the same way, with USD-AUD indicating the number of Australian dollars per U.S. dollar. We collect the daily transaction price, bid quote, and ask quote of exchange rates during the period from January 1, 2018, to June 17, 2021, from the Bloomberg dataset. We consider this sample period to obtain a large number of observations (904 daily exchange rates for each currency) and reduce other global factor disturbances (i.e., the 2016 Brexit, the sterling flash crash, and the 2022 Russo-Ukrainian War). A longer sample period may increase the likelihood for the exchange rate connectedness to be affected by other factors. We compute the daily return for the i-th currency pair as the log difference of the exchange rates. In addition, daily option-implied volatility for each G10 currency pair (90 days), total assets in the Fed's balance sheet, federal funds target rate, and CBOE's VIX index are also obtained from the Bloomberg dataset.

For the COVID-19 pandemic data, we collect the daily confirmed cases at the country level from https://covid.ourworldindata.org/data/owid-covid-data.xlsx. In addition, we construct two daily relative COVID-19 infection measures by considering the number of new cases and infection rate (per one million people) of one country relative to the U.S. figures for our regression analysis.

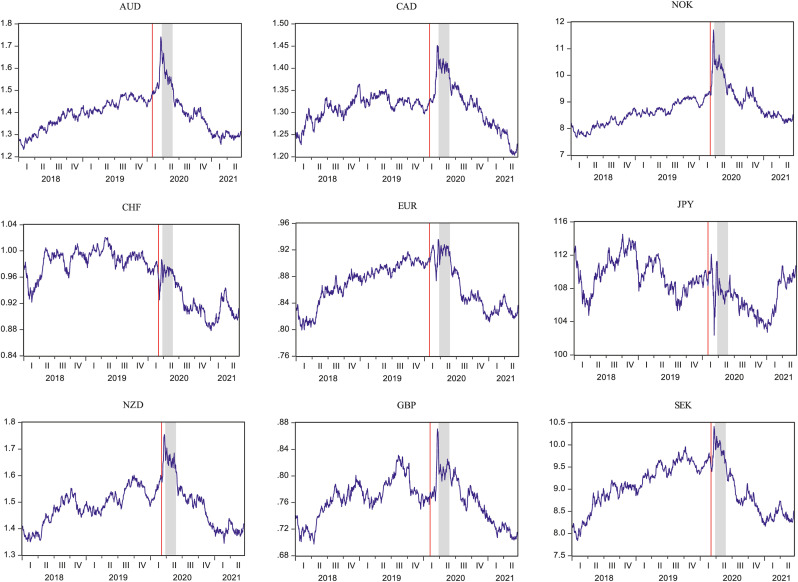

We plot the time series of G10 currency exchange rates in Fig. 2 . It is obvious that G10 currencies have become more volatile since the occurrence of the first COVID-19 infection case in the respective country, but exchange rate movements do not seem to follow a similar pattern during the pandemic. We observe that high-yield currencies—i.e., AUD, CAD, NOK, and NZD— started to depreciate against the USD at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in February 2020, reaching the lowest value just prior to March 23, 2020, and then began to appreciate during the following two months and beyond.6 This spike corresponds to the time when the Fed announced new programs to stimulate the economy during the COVID-19 outbreak. These programs included maintaining the target range for the federal funds rate at 0–0.25% and implementing LSAPs with no limit. However, the value of low-yield currencies—i.e., CHF, EUR, and JPY— increased during the pandemic outbreak and remained quite stable during the Fed's implementation of new programs. These figures suggest that, in addition to the COVID-19 pandemic, currency yields and the Fed's unconventional monetary policy may drive the exchange rate changes and the co-movements among them. Although high-yield and low-yield currencies moved quite differently during the pandemic, high-yield currencies, as a group, seem to share similar exchange rate movements and so do low-yield currencies.

Fig. 2.

Time Series of G10 Exchange Rates

Notes: The vertical red line indicates the occurrence of the first COVID-19 infection case in the country and the shaded area covers the period from March 23, 2020, to May 22, 2020. According to the BIS statistics for March 2020, we show the G10 central bank policy target interest rates: AUD (Australia), 0.25%; CAD (Canada), 0.25%; CHF (Switzerland), −0.75%; EUR (EU member countries), 0%; GBP (the United Kingdom), 0.1%; JPY (Japan), −0.1%; NOK (Norway), 0.25%; NZD (New Zealand), 0.25%; SEK (Sweden), 0%. In addition, the U.S. Fed policy target interest rate is 0.125%.

3. Diebold and Yilmaz connectedness measure

We use the Diebold and Yilmaz (2012) measure to estimate the return and risk premium interconnectedness among the nine exchange rates against the USD. The return of currency i is computed as:

| (1) |

where is the spot exchange rate of currency i at time t. Following Engel (2016), we define the risk premium as the excess return of holding a currency i relative to the USD, which is given by:

| (2) |

where RP i,t represents the risk premium of currency i expected at time t and and denote interest rates of currency i and USD at time t, respectively.

We employ the generalized VAR model proposed by Koop et al. (1996) and Pesaran and Shin (1998) because it is unaffected by the orders of variables. We consider a generalized variance decomposition with an H-step-ahead forecast horizon to generate a matrix in which the contribution of a one-standard deviation shock in currency j to currency i is given by:

| (3) |

where is the standard deviation of the error term for the jth equation; ∑ denotes the covariance matrix of the error vector e; stands for the selection vector with the ith element set to be unity and zero otherwise. After normalizing other currencies' contribution to currency i, we obtain:

| (4) |

The directional connectedness from other currencies to currency i is:

| (5) |

The directional connectedness from currency i to other currencies is:

| (6) |

Then total connectedness (TC) is:

| (7) |

Subtracting Equation (5) from Equation (6) yields the net directional connectedness (NC) from each currency to all other currencies as:

| (8) |

We obtain a net directional risk transmitter for currency i when and for a net directional risk recipient.

We then use the rolling-window estimation to yield TC and NC for the nine exchange rates in a dynamic manner. In the regression analysis, we identify some potential determinants of the dynamic connectedness. We also execute a difference-in-differences analysis to investigate the impact of changes in U.S. monetary policies on the dynamic connectedness.

4. Empirical results

In this section, we provide the relation between COVID-19 infection cases and exchange rate returns, present results of the static and dynamic exchange rate connectedness, and then conduct a regression analysis on determinants of the interconnectedness.

4.1. COVID-19 pandemic and exchange rate return

The UIP states that the currency with a higher interest rate will depreciate against the other currency by approximately the difference in their interest rates. Interest rate differential between two countries is indeed a well-known factor to explain exchange rate movements. However, the UIP can hardly hold in empirical studies. The failure of the UIP in practice can be attributed to random walk (Meese and Rogoff, 1983), time-varying risk premia (Fama, 1984; Dahlquist and Penasse, 2022), market frictions such as bid-ask spreads (Burnside et al., 2006), and carry trades (Brunnermeier et al., 2008).

Recently, Fu and Yang (2021) provide a potential factor to explain the movement of exchange rates. According to their argument, when a country has relatively more new COVID-19 infection cases than other countries, its government tends to implement preventive policies such as border closures, lockdowns, and travel/visa bans, which in turn weaken this country's economy and lead to currency depreciation. Hence, a country's currency is expected to depreciate (appreciate) against foreign currencies as its number of new COVID-19 infection cases rises (decreases) relative to other countries.

The Fed's unconventional monetary policy and investors' portfolio rebalancing adjustments may affect exchange rate movements. Neely (2015) shows that the Fed's unconventional monetary policy causes the USD to depreciate relative to other currencies. Bauer and Neely (2014) extend the portfolio rebalancing channel of Tobin (1969) to show that investors view bonds of various maturities and classes as imperfect substitutes. When the LSAPs push up the prices of U.S. long-term bonds, investors may turn to relatively underpriced debt of similar quality—i.e., other G10 countries—and drive up the price of that debt. The outflow of funds will lead the USD to depreciate, other things being equal.

In sum, we examine the effect of country j's COVID-19 pandemic severity relative to the U.S. on its exchange rate returns, along with the effects of interest rate differential, the Fed's unconventional monetary policy, and stock market volatility. We measure the relative effect of the COVID-19 pandemic by using two proxies: the difference in the number of new COVID-19 infection cases of country j relative to that of the U.S. and the difference in the new COVID-19 infection cases per one million population of country j relative to that of the U.S. The relation between COVID-19 infection cases and exchange rate returns is given by:

| (9) |

where , , and VIX t represent the interest rate differential between country j and the U.S., the difference in total assets of the central bank's balance sheets between country j and the U.S. (divided by 106), and U.S. stock market volatility at time t, respectively7 ; denotes the difference in the number of new COVID-19 infection cases of country j relative to that of the U.S. (divided by 106); is the difference in the new COVID-19 infection cases per one million population of country j relative to that of the U.S (divided by 104). The 3-month Treasury bill yields of the U.S. and other countries represent the interest rates. proxies the relative monetary policy impact and is used to measure the magnitude of one country relative to the U.S. unconventional monetary policy. We use the CBOE VIX index to measure the stock market volatility.

We report the regression results in Table 1 . In general, effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and the U.S. unconventional monetary policy on exchange rate returns are as expected. We find that interest rate differential has insignificant impact on exchange rate returns. In accordance with Neely (2015), Greenwood et al. (2020), and Swanson (2021), we find that the USD depreciates relative to country j's currency (i.e., exchange rate falls) as the Fed's LSAPs program expands (i.e., decreases). Stock volatility in the U.S. seems to increase the value of the USD against other currency as the coefficient on VIX is significantly positive. This result is understandable because the USD is considered a safe haven currency and thus the demand for the USD is abnormally high during volatile periods. Lastly, we find that as country j experiences more severe COVID-19 outbreaks, its currency tends to depreciate against the USD, in line with our expectation and consistent with Fu and Yang (2021).

Table 1.

| (1) | (2) | |

|---|---|---|

| Constant | 0.23*** (0.06) |

0.18*** (0.05) |

| −0.15 (0.10) |

−0.15 (0.10) |

|

| 0.70*** (0.17) |

0.69*** (0.18) |

|

| VIX | 0.01*** (0.00) |

0.01*** (0.00) |

| Diff_case | 0.52** (0.24) |

|

| Diff_case_per_million | 0.33* (0.17) |

|

| Fixed currency effects | Yes | Yes |

| Adj. R2 | 0.05 | 0.05 |

Note: This table reports the estimation of the linear models for return of exchange rate j (Rj, multiplied by 102).

where and denotes spot exchange rate j. represents the interest rate difference between country j and the U.S. represents the difference in total assets scales in balance sheets between country j and the U.S. (divided by 106). VIXt denotes the CBOE volatility index. denotes the difference in the number of new COVID-19 infection cases of country j relative to that of the U.S. (divided by 106). denotes the difference in the new COVID-19 infection cases per one million population of country j relative to that of the U.S (divided by 104). Robust standard errors (Newey and West, 1987) are in parentheses. ***, **, and * indicate significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.where represents the total assets in the U.S. Fed's balance sheet (divided by 106). represents the federal funds target rate (upper bound). denotes the CBOE volatility index. is a dummy equal to one during the period from January 23, 2020, to June 17, 2021, and zero otherwise. Robust standard errors (Newey and West, 1987) are in parentheses. ***, **, and * indicate significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

Overall, results in Table 1 highlight that the COVID-19 pandemic, interest rate differential, the Fed's unconventional monetary policy, and stock market volatility can serve as determinants of exchange rate returns. A follow-up question is whether these factors also influence the linkages and spillover transmission among exchange rates. In the following sub-sections, we conduct static and rolling-window analyses in return and risk premium connectedness among exchange rates and run regression analyses to find determinants of total and net connectedness.

4.2. Static analysis in connectedness measure

We calculate G10 exchange rate connectedness and report the full-sample static return and risk premium connectedness in Table 2, Table 3 , respectively. The optimal lag structure in the VAR model is 2, selected by using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC). In the ‘‘TO’’ row of Table 2, we show that the gross directional return connectedness from each currency to other currencies is relatively high for the AUD (89%) and EUR (87.2%) and relatively low for the JPY (21.1%). In the ‘‘FROM’’ column, the gross directional return connectedness from other currencies to each currency is high for the AUD (75.2%) and EUR (75.2%) and relatively low for the JPY (45%). The “net directional to others (NET)” row shows that (1) both the AUD and EUR serve as major transmitters of risk to other currencies with the largest NCs of 13.8% (≡89%–75.2%) and 12% (≡87.2%–75.2%), respectively; (2) the JPY is the major recipient of risk with the smallest NC of −23.9% (≡21.1%–45%). It is noteworthy that the JPY contributes the most to itself (55%) but the least to other currencies. Moreover, the results indicate that the AUD and EUR play the major role of transmitting risks to other currencies, whereas the JPY primarily serves as a recipient of risks from other currencies. A possible reason is that the JPY may operate as a safe haven (Greenwood-Nimmo et al., 2016) and thus generate little impact on other currencies.

Table 2.

Exchange rate return connectedness.

| AUD | CAD | CHF | EUR | GBP | JPY | NOK | NZD | SEK | FROM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUD | 24.8 | 11.3 | 4.2 | 8.7 | 8.2 | 0.9 | 12.4 | 17.9 | 11.5 | 75.2 |

| CAD | 15.1 | 33.3 | 2.5 | 6.4 | 7 | 0 | 14.1 | 12.1 | 9.5 | 66.7 |

| CHF | 5.9 | 3.4 | 31.5 | 19.3 | 6.9 | 10.1 | 5.9 | 6.7 | 10.4 | 68.5 |

| EUR | 9.3 | 5.4 | 15.2 | 24.8 | 8.3 | 4.5 | 9.3 | 9.2 | 14.1 | 75.2 |

| GBP | 11.4 | 7.4 | 6.8 | 10.6 | 31.6 | 2.6 | 10 | 9.9 | 9.7 | 68.4 |

| JPY | 2.8 | 1.1 | 17.5 | 9.9 | 4.7 | 55 | 2.4 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 45 |

| NOK | 13.9 | 11.5 | 4.2 | 9.1 | 7.6 | 0.3 | 26.5 | 12.3 | 14.6 | 73.5 |

| NZD | 18.8 | 9.4 | 5.2 | 9.1 | 7.7 | 1.4 | 11.8 | 25.4 | 11.3 | 74.6 |

| SEK | 11.9 | 7.2 | 8.2 | 14.1 | 7.6 | 1.3 | 13.7 | 11 | 24.9 | 75.1 |

| TO | 89 | 56.7 | 63.7 | 87.2 | 58 | 21.1 | 79.7 | 82.2 | 84.5 | 69.1 |

| NET | 13.8 | −10 | −4.8 | 12 | −10.4 | −23.9 | 6.2 | 7.6 | 9.4 |

Note: The ij-th entry of the upper-left 9 × 9 exchange rate sub-matrix gives the ij-th pairwise directional connectedness (i.e., the percentage of 10-day-ahead forecast error variance of exchange rate i due to shocks from exchange rate j). The rightmost (FROM) column gives total directional connectedness (from) (i.e., row sums [from all others to i]). The bottom (TO) row gives total directional connectedness (i.e., column sums [to all others from j]). The bottommost (NET) row gives the difference in total directional connectedness (TO minus FROM). The bottom-right element (in boldface) is the total connectedness index.

Table 3.

Exchange rate risk premium connectedness.

| AUD | CAD | CHF | EUR | GBP | JPY | NOK | NZD | SEK | FROM | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUD | 24.8 | 11.3 | 4.2 | 8.7 | 8.2 | 0.9 | 12.4 | 17.9 | 11.5 | 75.2 |

| CAD | 15.1 | 33.3 | 2.5 | 6.4 | 7.0 | 0.0 | 14.1 | 12.1 | 9.5 | 66.7 |

| CHF | 5.9 | 3.5 | 31.5 | 19.3 | 6.9 | 10.1 | 5.9 | 6.7 | 10.4 | 68.5 |

| EUR | 9.3 | 5.5 | 15.2 | 24.8 | 8.3 | 4.5 | 9.2 | 9.2 | 14.1 | 75.2 |

| GBP | 11.4 | 7.4 | 6.8 | 10.5 | 31.5 | 2.6 | 10.0 | 9.9 | 9.8 | 68.5 |

| JPY | 2.8 | 1.1 | 17.4 | 9.9 | 4.7 | 54.9 | 2.5 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 45.1 |

| NOK | 14.0 | 11.5 | 4.1 | 9.1 | 7.7 | 0.3 | 26.5 | 12.3 | 14.6 | 73.5 |

| NZD | 18.8 | 9.4 | 5.2 | 9.1 | 7.7 | 1.4 | 11.9 | 25.4 | 11.3 | 74.6 |

| SEK | 11.9 | 7.2 | 8.2 | 14.1 | 7.6 | 1.3 | 13.7 | 11.0 | 24.9 | 75.1 |

| TO | 89.1 | 56.8 | 63.6 | 87.1 | 58.1 | 21.1 | 79.8 | 82.3 | 84.6 | 69.3 |

| NET | 13.9 | −9.9 | −4.9 | 11.9 | −10.4 | −24 | 6.3 | 7.7 | 9.5 |

Note: The ij-th entry of the upper-left 9 × 9 exchange rate sub-matrix gives the ij-th pairwise directional connectedness (i.e., the percentage of 10-day-ahead forecast error variance of exchange rate i due to shocks from exchange rate j). The rightmost (FROM) column gives total directional connectedness (from) (i.e., row sums [from all others to i]). The bottom (TO) row gives total directional connectedness (i.e., column sums [to all others from j]). The bottommost (NET) row gives the difference in total directional connectedness (TO minus FROM). The bottom-right element (in boldface) is the total connectedness index.

Table 3 reports the static risk premium connectedness among G10 exchange rates. Similar to return connectedness, the “NET” row for risk premium connectedness points to the role of major risk transmitters for both the AUD (89.1%–75.2% = 13.9%) and EUR (87.1%–75.2% = 11.9%) and the role of major recipient of risk for the JPY (21.1%–45.1% = −24%). The JPY also exhibits the most contribution to itself (54.9%). Overall, our results indicate that the AUD and EUR tend to carry more risk premium and transfer it to other currencies while the JPY serves as a receiver of risk premium. As a whole, as shown in Table 2, Table 3, the average values of return and risk premium total connectedness are 69.1% and 69.3%, respectively.

4.3. Rolling-window analysis in connectedness measure

To further explore the evolution of the return connectedness for G10 exchange rates over time, we provide a dynamic analysis for the nine exchange rate returns by using rolling-window estimations where the width of the rolling window is 100 days and the predictive horizon for the variance decomposition is 10 days. The optimal lag structure in the rolling VAR is also 2. In addition, we conduct dynamic connectedness analysis for exchange rate risk premium.8

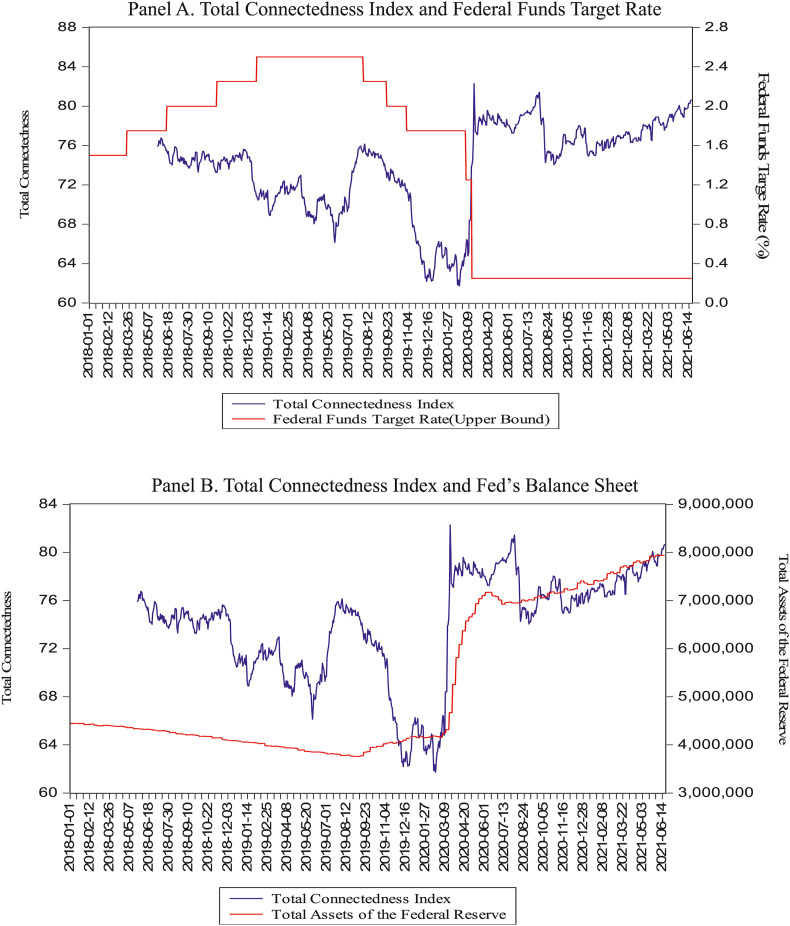

In Fig. 3 , we plot the dynamic total connectedness of exchange rate returns. The rolling total connectedness jumps from about 65% to 83% in March 2020 when the Fed announced its plan to cut the federal funds target rate and conduct the LSAPs program to stimulate the economy during the COVID-19 outbreak. In Panel A, we observe that when the federal funds rate suddenly falls from 1.25% to 0.25%, the rolling total connectedness exhibits a substantial jump to its highest level and remains at a relatively high level until August 2020. In contrast, when we plot the total assets of the Fed and the total connectedness in Panel B, we find that they seem to move in the same direction from March 2020 to June 2021. This evidence suggests that the Fed's unconventional monetary policy during the pandemic seems to trigger large impacts on FX interconnectedness.

Fig. 3.

Rolling total connectedness index and U.S. Fed policy indicators.

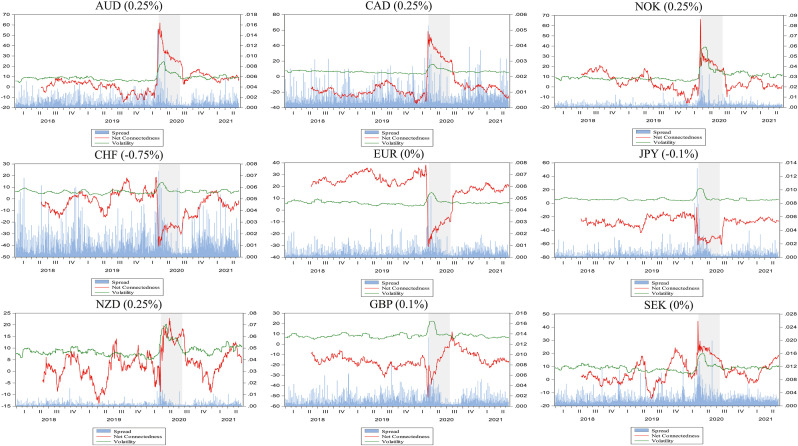

We present the movements of directional net return connectedness from each currency to other currencies and exchange rate liquidity and volatility in Fig. 4 . We use the bid-ask spread of each exchange rate to measure its corresponding liquidity. With regard to the exchange rate volatility, we use the implied volatility from one-month options of each exchange rate. Fig. 4 shows that high-yield currencies, such as the AUD, CAD, and NOK, generate a stronger directional connectedness to others at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic: (1) the NC jumps to almost 60% for AUD and CAD and above 60% for NOK before gradually decreasing to 20% from March 23, 2020, to July 22, 2020, (gray area) as compared to levels generally below 10% during other periods; (2) the peak of NC occurs when the corresponding bid-ask spread reaches the highest level and exchange rate volatility begins to rise. However, low-yield currencies such as CHF, EUR, and JPY provide a weaker directional connectedness to others during the COVID-19 outbreak: (1) the NC falls to the lowest level (−40% for CHF, −30% for EUR, and −60% for JPY) and remains at relatively low levels from March 23, 2020, to July 22, 2020; (2) each NC exhibits an inverse pattern with its corresponding bid-ask spread and exchange rate volatility. Other mid-yield currencies do not seem to present any consistent pattern.

Fig. 4.

Net Directional Connectedness, Bid-Ask Spread, and Volatility of Exchange Rates

Notes: According to the BIS statistics for March 2020, we show the G10 central bank policy target interest rates in parentheses. In addition, U.S. Fed policy target interest rate is 0.125%. The shaded area covers the period from March 23, 2020 to July 22, 2020.

We display plots of each directional net exchange rate return connectedness and the U.S. VIX index in Fig. 5 . The figure shows that for the AUD, CAD, and NOK, the NC jumps to the top level along with the VIX index and declines when the VIX index falls. In contrast, the CHF, EUR, and JPY exhibit weakened NC and present an opposite pattern with the VIX index. Fig. 5 points out that high-yield currencies transmit more currency risk during the peak of market volatility, whereas low-yield currencies receive more risks from other currencies. We find similar results when we use the JP FX volatility index as an alternative measure of volatility, as shown in Fig. 6 . Higher FX volatility may induce higher market risk, so market participants may pile up their funds into high-yield currencies and insomuch strengthen NC for those currencies.

Fig. 5.

Net Directional Connectedness and U.S. VIX Index

Notes: According to the BIS statistics for March 2020, we show the G10 central bank policy target interest rates in parentheses. In addition, the U.S. Fed policy target interest rate is 0.125%. The shaded area covers the period from March 23, 2020, to July 22, 2020.

Fig. 6.

Net Directional Connectedness and JP FX Volatility Index

Notes: According to the BIS statistics for March 2020, we show the G10 central bank policy target interest rates in parentheses. In addition, the U.S. Fed policy target interest rate is 0.125%. The shaded area covers the period from March 23, 2020, to July 22, 2020.

In addition, we provide the descriptive statistics of TC and NC based on the previous rolling-window estimations of connectedness in Table 4 for the full sample period (Panel A) and two sub-sample periods (before and after January 23, 2020, in Panels B and C).9 Panel A shows that, consistent with results in Table 2, the AUD and EUR have positive mean NC and thus serve as risk transmitters to other currencies in the system, whereas the JPY has negative mean NC and hence operates as a net risk recipient. In addition, we find that not every NC is stationary based on the ADF unit root test, but each detrended NC is stationary.

Table 4.

Summary statistics of total connectedness and net directional connectedness.

| Variables | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Panel A. Full Sample Period | ||||||||||

| Mean | 69.93 | 10.29 | −7.94 | −4.59 | 14.40 | −12.18 | −25.01 | 9.51 | 7.40 | 8.10 |

| Std. Dev. | 5.43 | 10.97 | 16.06 | 13.06 | 15.26 | 7.55 | 12.12 | 8.81 | 5.88 | 8.03 |

| ADF test | −1.77 | −2.62* | −2.36 | −2.41 | −2.62* | −3.00** | −2.79** | −2.66* | −3.16** | −2.38 |

| Detrended ADF test | −2.80** | −2.79** | −2.57* | −2.77* | −2.76* | −3.08** | −2.92** | −2.98** | −3.18** | −3.08** |

| Panel B. Sub-period 1: Before January 23, 2020 | ||||||||||

| Mean | 67.19 | 4.23 | −14.41 | 1.49 | 22.83 | −13.92 | −20.95 | 8.74 | 5.76 | 6.20 |

| Std. Dev. | 4.00 | 5.39 | 5.60 | 6.81 | 4.13 | 4.29 | 6.11 | 7.28 | 5.19 | 8.24 |

| Panel C. Sub-period 2: After January 23, 2020 | ||||||||||

| Mean | 73.20 | 17.55 | −0.19 | −11.89 | 4.31 | −10.10 | −29.86 | 10.43 | 9.36 | 10.37 |

| Std. Dev. | 5.10 | 11.54 | 20.48 | 14.89 | 17.46 | 9.77 | 15.33 | 10.28 | 6.07 | 7.14 |

This table reports the summary statistics on the levels of the total connectedness and net directional connectedness of G10 currencies for the full sample period (January 1, 2018–June 17, 2021) in Panel A and for the two sub-samples (before and after January 23, 2020) in Panel B and Panel C. The Augmented Dickey-Fuller (ADF) test is used to test the null hypothesis that the series has a unit root, with an optimal of 6 lag lengths, according to Schwarz information criterion (SIC). The ADF test is also executed for the detrended series (i.e. removing a deterministic trend). ***, **, and * indicate significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

Results in Panels B and C indicate that the COVID-19 pandemic and the Fed's corresponding policy changes have varying effect on G10 currencies. Specifically, we find that: (1) the TC rises from sub-period 1 to sub-period 2 (i.e., from 67.19% to 73.20%); (2) the NC of the AUD, CAD, and NOK rise substantially from sub-period 1 to sub-period 2 (i.e., from 4.23% to 17.55% for AUD, −14.41% to −0.19% for CAD, and 8.74%–10.43% for NOK), but it falls for the CHF, EUR, and JPY. These results confirm the findings in Fig. 4, Fig. 5 that high-yield currencies transmit more currency risk to other currencies during the COVID-19 pandemic period, whereas low-yield currencies receive more currency shocks from other currencies. Since interest rates play a crucial role in the connectedness of exchange rates, we further investigate whether investors' carry trade activities and portfolio rebalancing adjustments dominate the FX interconnectedness during the COVID-19 pandemic in the following sections.

In this study, we also use the TVP-VAR connectedness model proposed by Antonakakis and Gabauer (2017) and Dogah (2021) to investigate the exchange rate connectedness of G10 currencies.10 Antonakakis and Gabauer (2017) point out that the advantages of the TVP-VAR connectedness model include: (1) no need to arbitrarily set the rolling-window size, (2) no loss of observations, and (3) no outlier sensitivity. In the TVP-VAR connectedness analysis, we find that the results remain consistent with those obtained from the VAR-based model. This additional analysis confirms the robustness of our findings.

4.4. Determinants of TC and NC

Exchange rate connectedness is likely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic and government policies. Due to the zero lower-bound constraint, central banks tend to pursue unconventional monetary policies such as LSAPs to help the economy during a recession (Swanson, 2021). Wei et al. (2020) find that the COVID-19 outbreak generates shocks to the Renminbi and its linkages with “The Belt and Road” FX markets. Studying the Euro, Japanese Yen, Canadian Dollar, and British Pound, Narayan (2021) shows that the exchange rate spillover is higher over the COVID-19 period than the pre-COVID-19 period. Hence, we investigate the transmission channel of TC (after detrending) by estimating the following model:

| (10) |

where TA US denotes the total assets in the Fed's balance sheet (divided by 106), a proxy of LSAPs. TR is the federal funds target rate (upper bound), VIX represents the CBOE's volatility index, and COVID_19 is a dummy variable set to one during the COVID-19 outbreak (after January 23, 2020).

Table 5 reports the determinant analysis of the total exchange rate connectedness with various model specifications. When we include the TA US, TR, and VIX in the regression, the results show that the total exchange rate return spillover rises when the Fed increases the size of LSAPs or cuts the federal funds target rate. A higher VIX index is associated with a higher level of TC. Including TA US, VIX, and COVID_19 in the regression, we find that TC becomes more intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lastly, we account for all the underlying variables in the regression and find similar results. Our empirical evidence indicates that currency connectedness tends to be high during volatile periods (i.e., health crisis and market uncertainty) and economic downturns, which are usually accompanied by easing monetary policies.

Table 5.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | −25.96*** (3.09) |

−16.33*** (2.35) |

−28.27*** (3.31) |

| 3.12*** (0.36) |

2.87** (0.49) |

3.81*** (0.50) |

|

| TR | −4.08*** (0.65) |

−3.56*** (0.70) |

|

| VIX | 0.17*** (0.02) |

0.19*** (0.03) |

0.22*** (0.03) |

| COVID_19 | 7.27*** (1.78) |

3.67* (1.89) |

|

| A. R2 | 0.21 | 0.19 | 0.22 |

Note: This table represents estimation of the linear model for total connectedness ().

With regard to NC, we believe there are additional potential determinants. From the previous sections, we find that the Fed's unconventional monetary policy, market volatility, and the COVID-19 pandemic may affect the net directional connectedness from one exchange rate to others. Moreover, other key factors may include exchange rate illiquidity, implied volatility, COVID-19 infection cases, and COVID-19 rate of infection. It is worth noting that the high-yield and low-yield currencies generate inverse effects on the NC. According to Bauer and Neely (2014), low-yield and high-yield international bonds respond to the Fed's LSAPs with different degrees. In addition to high and low yields, we also account for their interaction terms with COVID-19 rates. Thus, the regression model of our determinant analysis for each NC i (after detrending) is given as follows:

| (11) |

where is the percentage bid-ask spread, which is computed by dividing the bid-ask spread by the midpoint (multiplied by 102), for currency pair i, denotes the implied volatility from one-month options, is a dummy which is equal to one in the period from January 23, 2020, to June 17, 2021, and zero otherwise, denotes the new COVID-19 infection cases of country i relative to that of the U.S., denotes the new COVID-19 infection cases per one million population in country i relative to that in the U.S, represents the dummy variable that equals one if currency i belongs to the high-yield group and zero otherwise, represents the dummy variable that equals one if currency i belongs to the low-yield group and zero otherwise, High (Low)-yield group means the yield of currency i belongs to the top one-third (the bottom one-third) ranked by yields,11 and and are interaction terms.

Table 6 provides the regression results of Equation (11). Model (1) shows that VIX index, volatility, and illiquidity are positively associated with the NC. We add an additional factor of COVID-19 pandemic in models (2) to (4) and find that when COVID-19 is more severe in country i, i.e., more new COVID-19 cases or a higher infection rate, its NC strengthens. In model (5), we take into account currency yields and find that currencies with higher yields are associated with higher NC, whereas those with lower yields have lower NC. This finding is in line with Bauer and Neely (2014) that international bonds with higher yields are more sensitive to the Fed's LSAPs than those with lower yields because the portfolio rebalancing effect dominates in countries with higher bond yields. Particularly, investors tend to adjust their portfolio by substituting more toward high-yield international bonds than low-yield international bonds in times of the Fed's LSAPs. Accounting for the interaction terms in model (6), we find that the NC significantly strengthens when the interaction term of high-yield and COVID-19 infection rate rises. These results imply that the Fed's unconventional monetary policies and COVID-19 infection cases may enhance investors' exchange rate portfolio rebalancing and carry trade activities between the high-yield and low-yield currencies, thereby generating higher NC for high-yield currencies.

Table 6.

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant | −1.29 (4.85) |

−1.50 (2.92) |

−9.58* (5.16) |

−8.15 (6.19) |

−30.88*** (10.20) |

−35.12*** (10.55) |

| TAi,t-TAUSt | 0.11*** (0.01) |

0.11*** (0.02) |

0.11*** (0.02) |

0.11*** (0.02) |

0.11*** (0.02) |

0.11*** (0.02) |

| TRi,t | −0.15 (0.44) |

−1.33 (1.12) |

−1.47 (1.90) |

−1.48 (2.23) |

−4.90*** (1.33) |

−5.81*** (1.30) |

| VIXi,t | 0.06 (0.05) |

0.09*** (0.03) |

0.07* (0.04) |

0.08** (0.04) |

0.10** (0.05) |

0.10** (0.05) |

| Illiquidityi,t | 2.29*** (0.90) |

2.32*** (0.84) |

2.16** (1.07) |

2.03** (2.00) |

2.53** (1.02) |

2.79** (1.30) |

| Volatilityi,t | 1.70*** (0.10) |

1.81*** (0.23) |

1.58*** (0.10) |

1.60*** (0.10) |

1.38*** (0.09) |

1.29*** (0.11) |

| COVID_19i,t | 2.24* (1.20) |

|||||

| New_casei,t | 0.86*** (0.05) |

|||||

| New_case_per_milloni,t | 0.12*** (0.03) |

0.18*** (0.03) |

0.04*** (0.01) |

|||

| 7.16*** (0.62) |

6.99*** (0.56) |

|||||

| −1.79** (0.88) |

−1.86** (0.91) |

|||||

| 0.51*** (0.12) |

||||||

| −0.07 (0.19) |

||||||

| Fixed year effects | Yes | NO | NO | NO | NO | NO |

| Fixed currency effects | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | NO | NO |

| A. R2 | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.61 | 0.25 | 0.25 |

Note: This table reports the estimation of the linear models for net directional connectedness from i exchange rate ().

where represents the difference in total assets scales in balance sheets between country i and the U.S. (divided by 107). represents the federal funds target rate (upper bound). VIXt denotes the CBOE volatility index. Illiquidityi,t is the percentage bid-ask spread for exchange rate i (multiplied by 102), which is calculated by dividing the bid-ask spread by the midpoint. Volatilityi,t denotes one-month option's implied volatility for exchange rate i. COVID_19 is a dummy equal to one during the period from January 23, 2020, to June 17, 2021, and zero otherwise. To analyze the impact of COVID-19 infection cases on net directional connectedness, we adopt the shorter sample period from January 23, 2020, to June 17, 2021, in models (3)–(6). New_casei,t denotes the number of new COVID-19 infection cases of country i relative to that of the U.S. (divided by 104). New_case_per_millioni,t denotes the new COVID-19 infection cases per one million population of country i relative to that of the U.S. represents the dummy variable that equals one if the currency i belongs to the high-yield group and zero otherwise, and represents the dummy variable that equals one if the currency i belongs to the low-yield group and zero otherwise. Robust standard errors (Newey and West, 1987) are in parentheses. ***, **, and * indicate significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.where represents the total assets in the Fed's balance sheet (divided by 106). VIXt denotes the CBOE volatility index. FXCTG10t represents the difference in Bloomberg Carry Trade Index and denotes the carry trade returns computed from G10 currency baskets. ∗∗∗, ∗∗, and ∗ indicate significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively

Given the above findings, we further explore whether carry trade activities influence the NC of high- and low-yield currencies. We use the Bloomberg Carry Trade Index to represent the carry trade returns computed from G10 currency baskets. The Bloomberg carry trade strategies take long positions in the 1/3rd of the highest yielding currencies and short positions in the 1/3rd with the lowest yields. The regression model for high- and low-yield currency groups is specified as:

| (12) |

where j is either the high-yield or low-yield currency group and FXCTG10 represents the Bloomberg Carry Trade Index.

The estimations of Equation (12) are reported in Table 7 . The results show that higher carry trade returns from the Bloomberg index are associated with greater NC for high-yield currencies (model 1) and lower NC for low-yield currencies (model 2). Although the timing of carry trades is not observable, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the Fed's LSAPs and federal funds rate cuts seem to drive up carry trade activities insomuch as to motivate investors to borrow low-yield currencies and invest in high-yield currencies among the G10. As traders convert low-yield currencies to high-yield currencies, the demand for high-yield currencies increases, leading to their appreciation and thereby inducing the net directional connectedness for high-yield currencies.

Table 7.

| (1) |

(2) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Constant | −14.88*** (1.00) |

21.09*** (1.19) |

| 0.65*** (0.19) |

−2.01*** (0.22) |

|

| VIX | 0.73*** (0.03) |

−0.73*** (0.04) |

| FXCTG10 | 1.02*** (0.34) |

−1.20*** (0.40) |

| A. R2 | 0.49 | 0.49 |

Note: This table reports the estimation of two linear models for average value of the net directional connectedness for high- and low-yielding currency groups ().

4.5. Discussion and policy implications

This study explores the exchange rate spillovers among G10 currencies and documents some interesting findings that may generate important policy implications. Firstly, we find that the AUD and EUR play a major transmitter role, whereas the JPY primarily serves as a recipient of risk from other currencies, which is consistent with Greenwood-Nimmo et al. (2016). Understanding to what extent currency markets are connected is important for not only researchers, but also corporations and investors. Multinational corporations are directly affected by currency connectedness because of their currency conversions and FX hedging activities. International investors who manage currency portfolios to speculate on exchange rate movements or diversify FX risk should also pay close attention to currency co-movements and the transmission of currency risk.

Secondly, we show that the COVID-19 outbreak affects the connectedness and transmission spillovers among exchange rates. Countries with more new COVID-19 cases relative to the U.S. experience currency depreciation, and their currencies tend to transmit risk to other currencies. Since no prior studies have explored the impact of COVID-19 infection cases on exchange rate spillovers, our findings provide timely policy implications for global policymakers. Specifically, central banks should monitor and evaluate the responses from worldwide foreign exchange markets during and after the COVID-19 shock in order to determine appropriate policy changes. In addition, central banks’ international coordination of policy actions can be essential to stabilize the global FX market given that exchange rates are interconnected.

Thirdly, we document the effects of the Fed's LSAPs (i.e., unconventional monetary policy) and G10 carry trade returns on FX transmission spillovers. The implementation of LSAPs and high carry trade returns enhance the spillover transmission from the high-yield currency group (AUD, CAD, and NOK) to the low-yield currency group (EUR, CHF, and JPY). We contribute to the carry trade literature by showing that carry trades can be an important determinant of FX spillover. Our findings are relevant to global investors who manage currency portfolios and conduct carry trades.

5. Difference-in-differences analysis for U.S. Monetary policy

In the previous analyses, we attempt to assess the effect of unconventional monetary policies by considering the Fed's total assets in its balance sheet, which proxies the scale of LSAPs. When the federal funds rate approached zero during the COVID-19 pandemic, the Fed's total assets increased sharply, which significantly affects the total connectedness and directional connectedness of high-yield and low-yield exchange rate groups. To investigate whether the Fed's conventional monetary policy affects directional connectedness of high-yield and low-yield exchange rate groups as well, we compare their directional connectedness before and after changes in the federal funds target rate by adopting a difference-in-differences analysis.12 We test the difference between two means of net directional connectedness for high-yield and low-yield currency groups both before and after each of the eight federal funds rate adjustments.

Table 8 reports the estimation results for means of net directional connectedness for high-yield and low-yield currency groups from 20 days before each federal funds rate adjustment to 20 days after.13 There are five (three) downward (upward) adjustments in the sample data. Panel A of Table 8 includes five downward adjustments: (A.1) from 1.25% to 0.25% on March 13, 2020; (A.2) from 1.75% to 1.25% on March 2, 2020; (A.3) from 2% to 1.75% on October 29, 2019; (A.4) from 2.25% to 2% on September 17, 2019; (A.5) from 2.5% to 2.25% on July 30, 2019. We find that, for the relatively large downward adjustments of the federal funds rate in March 2020 listed in (A.1) and (A.2), high (low)-yield currencies generate significantly higher (lower) NC after the adjustment than before. In terms of the magnitude, the decrease in NC for low-yield currencies is higher than the increase in NC for high-yield currencies. For small downward adjustments, we find similar results but not as significant. (A.5) shows that the 25 basis points downward adjustment on the federal funds rate significantly enhances the transmitter role of net directional connectedness for high-yield currencies, while (A.4) shows that the same downward adjustment significantly reduces the transmitter role of net directional connectedness for low-yield currencies. The difference-in-differences are all significantly positive, except for (A.3).

Table 8.

Difference-in-differences analysis for net directional connectedness of high- and low-yielding currency groups around federal fund target rate adjustment day.

| Panel A: Net directional connectedness of high- and low-yielding currency groups before and after adjusted to low-level day [(-20, +20) trading days] | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (A.1) Adjustment from 1.25 to 0.25 [2020. 03. 13] |

(A.2) Adjustment from 1.75 to 1.25 [2020. 03. 02] |

|||||

| High Yield |

Low Yield |

Diff = High- Low | High Yield |

Low Yield |

Diff = High- Low | |

| Before Adj. | −3.00 | 3.08 | −6.08*** (-5.33) |

−5.33 | 4.62 | −9.95*** (-21.96) |

| After Adj. | 30.24 | −38.06 | 68.30*** (22.18) |

14.33 | −18.71 | 33.04*** (5.45) |

| Diff = After -Before |

33.24*** (15.58) |

−41.14*** (-16.47) |

74.38*** (16.48) |

19.66*** (5.48) |

−23.33*** (-4.76) |

42.99*** (5.08) |

| (A.3) Adjustment from 2 to 1.75 [2019. 10. 29] |

(A.4) Adjustment from 2.25 to 2 [2019. 09. 17] |

|||||

| High Yield |

Low Yield |

Diff = High- Low |

High Yield |

Low Yield |

Diff = High- Low |

|

| Before Adj. | −2.64 | 1.86 | −4.50*** (-8.73) |

−2.43 | 7.28 | −9.71*** (-21.08) |

| After Adj. | −3.99 | 1.49 | −5.48*** (-15.16) |

−3.75 | 4.87 | −8.62*** (-12.08) |

| Diff = After -Before |

−1.35*** (-3.09) |

−0.37 (-0.81) |

−0.98 (-1.14) |

−1.32*** (-3.91) |

−2.41*** (-3.83) |

1.09*** (2.80) |

| (A.5) Adjustment from 2.5 to 2.25 [2019. 07. 30] |

||||||

| High Yield |

Low Yield |

Diff = High- Low |

||||

| Before Adj. | −3.75 | 4.71 | −8.46*** (12.96) |

|||

| After Adj. | −1.00 | 3.12 | −4.12*** (-7.72) |

|||

| Diff = After -Before |

2.75*** (7.32) |

−1.59 (-1.51) |

4.34*** (3.98) |

|||

| Panel B: Net directional connectedness of high- and low-yielding currency groups before and after adjusted to high-level day [(-20, +20) trading days] | ||||||

| (B.1) Adjustment from 2.25 to 2.5 [2018. 12. 18] |

(B.2) Adjustment from 2 to 2.25 [2018. 09. 25] |

|||||

| High Yield |

Low Yield |

Diff = High- Low | High Yield |

Low Yield |

Diff = High- Low | |

| Before Adj. | −1.01 | 0.78 | −1.79** (-3.75) |

−3.89 | 0.75 | −4.64*** (-21.71) |

| After Adj. | −2.08 | 4.36 | −6.44*** (-29.85) |

−4.03 | 1.72 | −5.75*** (-33.17) |

| Diff = After -Before |

−1.07*** (-5.26) |

3.58*** (7.39) |

−4.65*** (-7.02) |

−0.14 (-0.56) |

0.97*** (5.82) |

−1.11*** (-3.26) |

| (B.3) Adjustment from 1.75 to 2 [2018. 06. 12] |

||||||

| High Yield |

Low Yield |

Diff = High- Low |

||||

| Before Adj. | −3.59 | 0.62 | −4.21*** (-15.81) |

|||

| After Adj. | −2.72 | 2.29 | −5.01*** (-13.60) |

|||

| Diff = After -Before | 0.87** (2.67) |

1.67*** (2.89) |

−0.80 (0.40) |

|||

Notes: This table reports the average values of daily net directional connectedness for high- and low-yielding currency groups from 20 days before the U.S. federal fund target interest rate adjustment implementation to 20 days after. The dates of target interest rate adjustment are in brackets. The t-statistics in parentheses for the Diff category test the null hypotheses that the differences in before-after interest rate adjustment and high-low yielding groups are equal to 0. ∗∗∗, ∗∗, and ∗ indicate significance at the 1%, 5%, and 10% levels, respectively.

Panel B of Table 8 accounts for three upward adjustments: (B.1) from 2.25% to 2.5% on December 18, 2018; (B.2) from 2% to 2.25% on September 25, 2018; (B.3) from 1.75% to 2% on June 12, 2018. (B.1) and (B.2) show that high (low)-yield currencies generate lower (higher) NC after the adjustment than before. After the adjustment, the transmitter role of net directional connectedness of low-yield currencies is enhanced significantly. (B.3) presents similar results for low-yield currencies, but the difference-in-differences is not significant.

In sum, similar to the Fed's LSAPs, the Fed's conventional monetary policy also affects directional connectedness of high-yield and low-yield exchange rate groups. If the Fed lowers the federal funds rate, the transmitter role of net directional connectedness of high-yield currencies is enhanced. In contrast, if the Fed raises the federal funds rate, the transmitter role of net directional connectedness of low-yield currencies is enhanced. These findings are likely related to carry trades as analyzed earlier.

6. Conclusion

We use the connectedness measure of Diebold and Yilmaz (2012, 2014) to investigate the connectedness among G10 currencies. We find that the USD-AUD and USD-EUR exchange rates are net risk transmitters, whereas the USD-JPY is a net risk receiver. Moreover, this study explores the determinants of the FX interconnectedness to fill the gap in the literature. Our results show that the Fed's unconventional monetary policy, COVID-19 outbreak, and VIX index strengthen the total connectedness. A country with relatively high new COVID-19 cases can trigger exchange rate return spillover from this country to others. This finding is robust to an alternative measure of the COVID-19 infection rate.

What makes our study unique is that we further explore the impact of high- and low-yield currencies and the interaction terms of high- and low-yield currencies and COVID-19 infection rates on the FX net directional connectedness from one currency to other currencies. We provide evidence to show that the Fed's unconventional monetary policies augment the exchange rate carry trade profits for investors. Such trading activities enhance the appreciation of the high-yield currencies, causing a larger net directional connectedness from the high-yield currencies to the low-yield currencies. The unconventional monetary policies due to the health crisis and market uncertainty motivate investors' carry trade activities through the portfolio rebalancing channel.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the editor Prof. Sushanta Mallick and two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions, which have greatly improved our paper. Yu-Lun Chen acknowledges financial support from the Ministry of Science and Technology, Taiwan (R.O.C.) (MOST 109-2410-H-033 -002 -MY2).

Handling Editor: Sushanta Mallick

Footnotes

G10 currencies include the USD (the United States), AUD (Australia), CAD (Canada), CHF (Switzerland), EUR (Euro zone countries), GBP (the United Kingdom), JPY (Japan), NOK (Norway), NZD (New Zealand), and SEK (Sweden). Since we use USD as the reference currency, we only consider the nine USD-based exchange rates in our analyses.

Swanson (2021) points out that the zero lower bound period in the U.S. began on December 16, 2008, when the Federal Reserve's Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) lowered the federal funds rate—its conventional monetary policy instrument—to essentially zero. The FOMC began to pursue unconventional monetary policies to stimulate the economy. The two most extensively used such policies are “forward guidance”—communication by the FOMC about the likely future path of the federal funds rate over the next several quarters—and LSAPs—purchases by the Federal Reserve of hundreds of billions of dollars of longer-term U.S. Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities.

Diebold and Yilmaz (2012), Wei et al. (2020), and Narayan (2021) use the term “spillover.” Diebold and Yilmaz (2014), Greenwood-Nimmo et al. (2016), Baruník et al. (2017), Kočenda and Moravcová (2019), Wen and Wang (2020), and Atenga and Mougoué (2021) use both spillover and connectedness. Following the aforementioned studies, we also use both terms interchangeably.

The Fed announced use of its full range of tools (LSAPs) to support households, businesses, and the overall U.S. economy against the coronavirus pandemic on March 23, 2020. For example, to support critical market functioning, the FOMC would purchase Treasury securities and agency mortgage-backed securities in the amount needed to support smooth market functioning and effective transmission of monetary policy to broader financial conditions and the economy.

The Bloomberg Carry Trade Index represents the carry trade returns computed from G10 currency baskets and states in values representing cumulative returns since their inception in 1999. The index was normalized to 100 in 1999. Currencies in the FX G10 carry strategies are ranked according to the 1-month yields implied by their spot and forward currency exchange rates and U.S. dollar's LIBOR. The carry trade strategies take long positions in the 1/3rd with the highest yielding currencies and short positions in the 1/3rd with the lowest yields.

Since the exchange rate is quoted as the amount of the currency per USD, a higher value indicates depreciation of the currency against USD.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting the consideration of the relative monetary policy variable in the regression analysis.

The results of the dynamic connectedness analysis for the nine exchange rate risk premiums are consistent with those from the exchange rate return analysis and are available upon request.

On January 23, 2020, China imposed a lockdown in Wuhan and other cities in Hubei in an effort to quarantine the center of an outbreak of COVID-19; this action was commonly referred to as the Wuhan lockdown.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting use of the TVP-VAR connectedness model to address the problem of the omission of some data. The TVP-VAR connectedness results are not reported in this study due to space constraints but are available on request.

The high-yield currency group includes the AUD, CAD, and NOK; the low-yield currency group includes the EUR, CHF, and JPY.

The tools of the Fed's conventional monetary policy include open market operations, discount policy, and reserve requirements that determine the federal funds rate. The federal funds target rate represents the upper limit of the Fed target range established by the FOMC. The Fed sets the target rate and then conducts open market operations so that the overnight interest rate on funds deposited by banks at the Fed reaches that target.

We follow the work of Chen and Xu (2021) to execute the difference-in-differences analysis for the event and consider 20 days before and after the rate adjustment day to avoid any confounding effect.

Data availability

The authors do not have permission to share data.

References

- Abankwa S., Blenman L.P. Measuring liquidity risk effects on carry trades across currencies and regimes. J. Multinatl. Financ. Manag. 2021 [Google Scholar]

- Antonakakis N., Gabauer D. 2017. Refined Measures of Dynamic Connectedness Based on TVP-VAR. Munich Personal RePEc Archive (MPRA) Paper No. 78282. [Google Scholar]

- Atenga E.M.E., Mougoué M. Return and volatility spillovers to African currencies markets. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money. 2021;73 [Google Scholar]

- Avdjiev S., Du W., Koch C., Shin H.S. The dollar, bank leverage, and deviations from covered interest parity. Am. Econ. Rev.: Insights. 2019;1(2):193–208. [Google Scholar]

- Baruník J., Kočenda E., Vácha L. Asymmetric volatility connectedness on the forex market. J. Int. Money Finance. 2017;77:39–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer M.D., Neely C.J. International channels of the Fed's unconventional monetary policy. J. Int. Money Finance. 2014;44:24–46. [Google Scholar]

- Bekaert G., Panayotov G. Good carry, bad carry. J. Financ. Quant. Anal. 2020;55(4):1063–1094. [Google Scholar]

- Brunnermeier M.K., Nagel S., Pedersen L.H. Carry trades and currency crashes. NBER Macroecon. Annu. 2008;23(1):313–348. [Google Scholar]

- Burnside C., Eichenbaum M.S., Kleshchelski I., Rebelo S. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2006. The Returns to Currency Speculation. Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y.L., Xu K. The impact of RMB's SDR inclusion on price discovery in onshore-offshore markets. J. Bank. Finance. 2021;127 [Google Scholar]

- Dahlquist M., Penasse J. The missing risk premium in exchange rates. J. Financ. Econ. 2022;143(2):697–715. [Google Scholar]

- Diebold F.X., Yilmaz K. Better to give than to receive: predictive directional measurement of volatility spillovers. Int. J. Forecast. 2012;28(1):57–66. [Google Scholar]

- Diebold F.X., Yilmaz K. On the network topology of variance decompositions: measuring the connectedness of financial firms. J. Econom. 2014;182(1):119–134. [Google Scholar]

- Dogah K.E. Effect of trade and economic policy uncertainties on regional systemic risk: evidence from ASEAN. Econ. Modell. 2021;104 [Google Scholar]

- Du W., Tepper A., Verdelhan A. Deviations from covered interest rate parity. J. Finance. 2018;73(3):915–957. [Google Scholar]

- Engel C. Exchange rates, interest rates, and the risk premium. Am. Econ. Rev. 2016;106(2):436–474. [Google Scholar]

- Fama E.F. Forward and spot exchange rates. J. Monetary Econ. 1984;14(3):319–338. [Google Scholar]

- Feng G.F., Yang H.C., Gong Q., Chang C.P. What is the exchange rate volatility response to COVID-19 and government interventions? Econ. Anal. Pol. 2021;69:705–719. [Google Scholar]

- Fu H., Yang J.C. 2021. Currency Risk Premium and COVID-19 Pandemic. (Working paper) [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood R., Hanson S.G., Stein J.C., Sunderam A. National Bureau of Economic Research; 2020. A Quantity-Driven Theory of Term Premia and Exchange Rates. Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwood-Nimmo M., Nguyen V.H., Rafferty B. Risk and return spillovers among the G10 currencies. J. Financ. Mark. 2016;31:43–62. [Google Scholar]

- Kočenda E., Moravcová M. Exchange rate comovements, hedging and volatility spillovers on new EU forex markets. J. Int. Financ. Mark. Inst. Money. 2019;58:42–64. [Google Scholar]

- Koop G., Pesaran M.H., Potter S.M. Impulse response analysis in nonlinear multivariate models. J. Econom. 1996;74(1):119–147. [Google Scholar]

- Meese R.A., Rogoff K. Empirical exchange rate models of the seventies: do they fit out of sample? J. Int. Econ. 1983;14(1–2):3–24. [Google Scholar]

- Narayan P.K. Understanding exchange rate shocks during COVID-19. Finance Res. Lett. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2021.102181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neely C.J. Unconventional monetary policy had large international effects. J. Bank. Finance. 2015;52:101–111. [Google Scholar]

- Newey W.K., West K.D. Hypothesis testing with efficient method of moments estimation. Int. Econ. Rev. 1987;28(3):777–787. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaran H.H., Shin Y. Generalized impulse response analysis in linear multivariate models. Econ. Lett. 1998;58(1):17–29. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson E.T. Measuring the effects of Federal Reserve forward guidance and asset purchases on financial markets. J. Monetary Econ. 2021;118:32–53. [Google Scholar]

- Tobin J. A general equilibrium approach to monetary theory. J. Money Credit Bank. 1969;1(1):15–29. [Google Scholar]

- Wei Z., Luo Y., Huang Z., Guo K. Spillover effects of RMB exchange rate among B&R countries: before and during COVID-19 event. Finance Res. Lett. 2020;37 doi: 10.1016/j.frl.2020.101782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen T., Wang G.J. Volatility connectedness in global foreign exchange markets. J. Multinatl. Financ. Manag. 2020;54 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors do not have permission to share data.