Abstract

Assisted suicide and euthanasia are two forms of what is being called ‘assisted dying’, and they are touted by proponents as “progressive” and “compassionate”. In fact, they are, on the contrary, relics from the last century: today, in the 21st century, we have moved beyond such archaic solutions – we now have, instead, proper evidence-based palliative care. It is this that should be demanded for all.

This article will dispel the myths around dying that are often cited. It will also explore the oft-overlooked tragedies generated by assisted suicide, in the hope you, the reader, can be better informed about this retrogressive practice.

Introduction

I was a young junior doctor, doing my haematology placement, when the gentleman who had occupied side room three for over two weeks died naturally of his leukaemia, comfortably and very peacefully. It was one of the first times I had seen death - certainly the first time I had formed a close bond with a dying patient and their family. In one of those formative moments I will always remember, his adult son handed me a tin of chocolates for the ward and told me:

“Dr Matt, you know, my dad taught me how to use a spoon, ride a bike, wash and dress, to be fair and generous. He taught me how to be a good husband and father, he taught me how to graciously age… he taught me everything I know, and, you know what, he has now taught me how to die as well”

This is what a good death looks like: a life which is complete and a legacy handed on. This dying gentleman has both reassured and helped his son see death as a normal part of living and provided a model for him in the future. It was this moment that helped form my decision to go into palliative care - I found myself asking “how can I help achieve this in all my patients?” and “how can I help people achieve a good death?”

Of course, assisted suicide is incapable of achieving the same thing: because such suicide also creates an example and demands generational repetition. It feeds an unfounded fear of the process of dying, and a misunderstanding that the way to approach this fear is to pre-empt it. After much reflection and careful consideration, I do not think assisted suicide is at all compatible with palliative care. It would be a calamity and a great scandal if introduced here in the UK or Ireland.

There is a narrative that ‘of course’ palliative care would be heavily involved in assisted suicide. The reality is very different, ‘The Association of Palliative medicine’1, the largest representative body of palliative care doctors in the UK and Ireland, opposes any changes to the law. A survey of members outlined 82 % were opposed in 20152 and this was confirmed in the RCP survey in 20203 with 81% of palliative medicine physicians opposed. My esteemed palliative care colleagues, who have seen dying the most, are thus overall united in this thinking. These are also the physicians who are anecdotally one of (if not the most) accepting and progressive group of doctors and nurses in the health care profession. Their mantra is compassion. You have to ask yourself: Why are Palliative Care Physicians so overwhelmingly against assisted suicide?

If I were to pick one over-arching reason it would be that palliative care understands how vulnerable people can become. Certainly physically, but also psychologically, spiritually and socially. Indeed, I would argue, out of all the vulnerable groups, those approaching end of life are the most vulnerable, and need a higher degree of protection.

We shall now explore the ways in which this population becomes vulnerable, and why we must protect them.

Mental Health and Suicide prevention

In Canada, where assisted suicide and euthanasia are legal (and, euphemistically, titled “Medical Assistance in Dying – MAiD”), only 6.7% of 10,064 MAiD provisions (3.3% of all deaths in Canada) were referred to a psychiatrist for assessment in 20214. Likewise, in Oregon, in 2021 only 2 patients out of 383 were referred for psychiatric evaluation (0.5%)5, in 2020 this was only 1 patient out of 1886. Couple this with data showing three quarters of those requesting assisted suicide report being lonely and 60% are clinically depressed7, it is evident we are missing mental health as a causative factor in these patients.

In the Netherlands (where again, assisted suicide and euthanasia are legal) an analysis of individuals requesting euthanasia or assisted suicide for mental health issues showed that the commonest diagnosis was a depressive mood disorder and that, compared with the general population, they were more likely to be single, female, or a lower educational background and with a history of sexual abuse8.

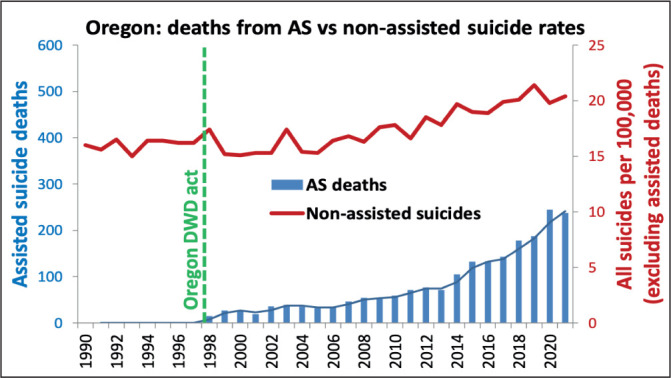

It had been hoped that legalising assisted suicide would reduce the background rate of “ordinary” suicide, positing that some ‘not assisted’ suicides happen because the victims are terminally ill and/or have unbearable symptoms.

It doesn’t - evidence suggests the opposite. In Oregon, the background suicide rate has risen by nearly one third (32%) since ‘assisted suicide’ was legalised9,10. In Europe this has been thoroughly investigated and controlled against neighbouring countries and trends by David Jones’s recent paper11. He confirms the data demonstrates a rising ‘not assisted’ suicide rate in countries permitting assisted suicide. Indeed, Belgium now has the highest non-assisted suicide rate in women in Europe11.

“In all of the four jurisdictions (Switzerland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, and Belgium) there have been very steep rises in suicide (incl. AS) or in ISID (Intentional self-initiated death) after the introduction of EAS (Euthanasia or Assisted Suicide). A striking example is the suicide rate (incl. AS) of women in Switzerland which has roughly doubled since 1998. Many more people have died prematurely after these changes.”11

Used with permission from https://kadoh.uk12 Non-assisted suicides in Oregon have risen by 32% despite legalising assisted suicide12.

In the name of ‘progress’ there has been a societal moral shift in these countries. Not only is suicide a reasonable course of action in the face of hardship, but those medical professionals who don’t provide assisted suicide have questionable ethics, whereby they are perceived more concerned with their own moral hang-ups than the welfare of the patient. This is outlined in the desperately sad case in which a Dad got his son to shoot him dead because he had been refused legal assisted suicide in Australia13. It is becoming a ‘right’ to demand and thus provide.

Assisted suicide bypasses the exploration of mental health, it damages the excellent work to normalise talking about mental health, and it conflates ‘autonomy’ above mental illness. All the while often proponents are cheering you on to fight for your right to have someone help you commit suicide. Topsy-Turvy doesn’t cover it.

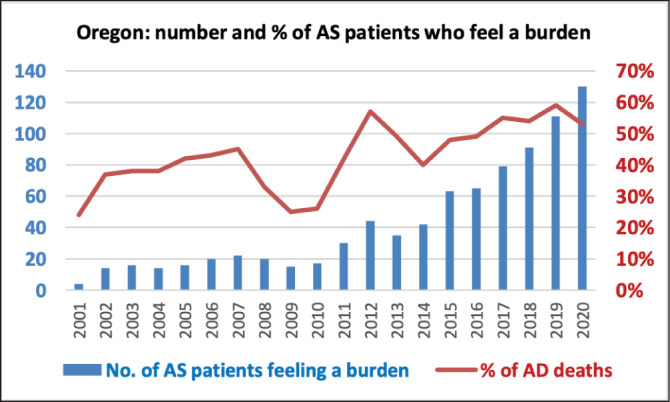

Burden

In Oregon’s 2021 report on reasons people had assisted suicide, 54% felt a burden and 8% had financial concerns. The percentage of assisted suicides in Oregon who felt a burden has doubled in the last 10 years (26% to 54%)5.

Used with permission from https://kadoh.uk12

“I don’t want to be a nuisance” as one of my patients put it, and although sometimes is perceived as noble, is where I believe society should step in.

Even out-with mental illness, society has a deep responsibility to protect the most vulnerable, and who is the most vulnerable if not those who are open to suggestion or worse, pressurised?

Simply having the option of assisted suicide expressed is in itself, an acknowledgment this is an acceptable course of action, and thus acts as a ‘pressure to consider such’. I imagine that disabled people understand what it is to feel like a burden on society, they are only too aware of the implicit suggestion this creates. This explains why all the major organisations representing the disabled are opposed to such legislation as they are aware of being perceived ‘as a nuisance’14.

No matter how caring your family is, this societal pressure would be exerted upon everyone who had a terminal illness, or in Canada and parts of Europe, self-described suffering. The pressure may be spoken or unspoken, but by creating an option, a door opens, in which consideration of an assisted suicide becomes real. The expectation to alleviate a burden on their family will be felt by the patient, or worse the patient perceives forcing a burden upon their family to care for them. As many suicide letters have sadly written, “You are better off if I wasn’t here.”15.

Within palliative care I have readily seen the gratification and melancholy pleasure of family caring for their loved one. Albeit it is often hard work and there comes a tipping point of which professionals are needed, however like caring for a new-born child there is pleasure in the hardship. This ‘burden’ perceived by the patient is often a gladly received role by the family.

In discussions with families, I have often asked them to put on each other’s shoes. The point reveals how much they care about each other and the ‘welcome role’ of caring for a loved one. It becomes obvious if roles were reversed they would care for the other.

However if, as sometimes happens there isn’t a caring family, our societies role is surely to provide an environment which substitutes that ‘family role’. I feel many nursing homes, social care, the hospitals, hospices and community palliative care services provide this role exceptionally well, although albeit work needs to be done to be equitable across the whole country. This is the opposite of what some Canadians are experiencing as assisted suicide becomes the only option with their housing and social crisis16.

Or maybe it’s even worse, how can it be uncovered that there is a coercive family? Exerting a pressure on the patient into assisted suicide. Maybe out of spite, money, feud or neglect or any number of reasons. Legislation has to be for the whole of society not just for the well-meaning families, and not be left for doctors to be pretend detectives or judges.

I have also witnessed the traumatic effects of suicide personally. The regret and questioning and torment this action brings to those remaining. It is important to highlight there is no requirement in any of the legislations to tell family and loved ones of what they are planning to do, as it’s touted as being based on individual autonomy. Inevitably, in the pursuit to not be a burden some people may create a greater one. “No man is an island” - John Dunne17.

Dignity

Death is an unknown. Death however has the misconception that it’s commonly associated with pain, suffering and indignity, this is really not true for the vast vast majority of cases. The prominent lobbying group is called ‘Dignity in Dying’ highlights the word ‘dignity’ in taking one’s life. Would assisted suicide help create dignity?

Dignity is not something you can claim for yourself, it is placed upon you. Dignity is given to you through a caring, respectful environment. The Queen, for example, is the most dignified lady I can think of, because we placed that respect and honour upon her. The palliative care ethos is something that restores that dignity in dying because of the caring people and environment the patient finds themselves in at home, hospice, community or hospital.

The lobbying group ‘Dignity in Dying’ is therefore misnamed, it predisposes the only ‘dignified’ way to die is to use assisted suicide, hence the name. This is clearly not true as many through history have died with dignity naturally. They also mistakenly define ‘dignity’ synonymously with personal choice, there is a big overlap to be sure, but compassion and dignity is a lot more than that. Dignity is passionately the pursuit of making ‘you’ more ‘you’, bestowing you with worth and value.

The lack of absolute certainty that palliative care can control all the symptoms is often used as a rational for assisted suicide, however a lot less well recognised is that assisted suicide is actually associated with multiple complications itself.

Oregon, despite having the best available recorded data out of all assisted suicide jurisdictions is incomplete, with no record of the complications (‘unknown’ in the table below) in 67% of all patients. Out of the recorded known data 9.3% had complications5.

In an interestingly never repeated study in the Netherlands, 7% vomited the medication up and 16% experienced significant problems such as failure to induce coma, or induction of coma followed by awakening of the patient or a prolonged time to die18.

In Canada there is anecdotal recognition of the many complications from MAiD, but worryingly there is no data recorded to quantify this, creating an evidence free zone19.

Chart from Oregon ‘Death with Dignity Act’ 2021 report 5

| Characteristics | 2021 | 2020 | 1998–2019 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (N=238) | (N=259) | (N=1,662) | (N=2,159) | |

| Complications 8 | (N=238) | (N=259) | (N=1,662) | (N=2,159) |

| Difficulty ingesting/regurgitated | 5 | 3 | 30 | 38 |

| Seizures | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Other | 1 | 1 | 15 | 17 |

| None | 69 | 69 | 708 | 846 |

| Unknown | 163 | 185 | 907 | 1,255 |

| Other outcomes | ||||

| Regained consciousness after ingesting DWDA medications | 1 | 0 | 8 | 9 |

This is regrettably understandable given there is no lethal drug combination that has ever been formally researched or agreed for such a purpose20. As a consequence Oregon have tried four different drug mixtures in the last seven years5. Only one study 30 years ago has examined the complication rate for assisted suicide (outlined above)18. This has never been repeated. Why?

Assisted suicide is by its nature a pre-emptive intervention and thus will never wholly correspond to the tiny minority in which death is difficult. Inevitably we will be ending the life of many early, with complications, who would have had a comfortable death. We do this for no good discernible reason other than ‘fear of loss of dignity’ i.e. an unlikely future of ‘suffering’. Is this ethos dignified? How many lives cut short justify avoidance of the rare complex deaths managed by Palliative Care?

Putting this together with our well recognised poor prognostication,21,22,23 a changing mind (a wish to die is often transient24) and we will be ending the life of patients who could also live on and would have nothing to fear. Is fear a good enough reason for ending a life early? What proportion of those who would have had a good natural death justify the right for a minority to avail of assisted suicide?

This poor prognostication is reflected in Oregon’s own data. In the 2021 report it outlines:

Of the 383 patients for whom prescriptions were written during 2021, 219 (57%) ingested the medication; 218 died from ingesting the medication, and one patient ingested the medication but regained consciousness before dying from the underlying illness (and therefore is not counted as a DWDA death). An additional 58 (15%) did not take the medications and later died of other causes. 5

This leaves 106 patients in which the status is unknown. The report goes on to outline out of this 106, 37 have died (unknown if related or not to lethal medications) and the remaining 69 we don’t know death or ingestion status. This pattern is repeated in each previous years with a regular cohort in which lethal medication were prescribed in “previous years”. This is surprising given legal confirmation in Oregon’s touted safeguard has to establish the patient has “six months or less to live” with a ‘terminal illness’, in which they have clearly objectively outlived!5 There is also no legal requirement to revisit the prescription of lethal medications after they have been issued. Is it safe to anyone to have lethal medications sitting in a person’s house for indefinite time periods?

Conclusion

So far, in every piece of proposed legislation for assisted suicide, there is not a single one which explores the question, “Why are you requesting this?” There is no legal requirement, other than eligibility criteria, to explain and address the question ‘Why?’

With the exception of mental health causing a distorted reality, the underlying reason for requesting assisted suicide is the simplest and most human of emotions, that of distress and fear. Fear for myself, fear for others and fear of loss of control. Fear of uncertainty, fear of suffering, fear of not being able to cope. Even fear of loss of their self-identity with dementia or simply despair about loss of what was. This is a normal response to awful news, but it is a tragedy if the response becomes a funnel into killing the patient, rather than addressing the distress and fear, the symptoms and psychological turmoil.

If assisted suicide is legalised in the UK or Ireland, every patient at some point will have to confront a new, terrible question. The simple act of placing this option on the table and asking the question, “Have you considered assisted suicide?” cruelly demands decisions from the patient. Whether to actively discount the option, in itself a recurrent challenge, often self-perceived as creating work and burden for others in continued living, or to avail of assisted suicide and get it done with.

It is coy to think healthcare professionals are not also caught up in the distress of a situation and in their alarm, take up the so called ‘therapeutic option’ in recommending assisted suicide. Those healthcare professionals who resist and object are deemed to weigh their own morality above the welfare of the patient by this new culture shift.

This ground swell of a retrogressive moral change in ‘valuing life is not a doctors primary aim’ anymore is causing a consistent slippage of the legislation. Such as in Canada, where the original restriction on MAiD to people with ‘grievous and irremediable suffering’ and ‘6 months or less’ has been promptly dropped from the legislation. Now in 2021 the ‘reasonably foreseeable death’ requirement has also been removed with further legislation predicted pushing for certain mental health reasons to be included as eligible.

If the basis for providing this legislation is the prevention of suffering, it is brutally “logical”, and fair that the scope is widened, to those suffering mentally, to those with chronic disease who have a longer period of time, to children with a lower age of consent, or to those with dementia who can’t. After all it is only fair and equal to not restrict access to a personal ‘right’. Indeed, this is all happening right now.

I suggest we have a new suicide epidemic. The scandal of our century, which will be looked back on with the same horror of the eugenics programmes.

But it is not too late, I believe we should address the underlying, understandable, distress and fear of dying with true compassion and tenderness affirming their valuable personhood. The progressive stance is to move forward away from fear. To address it properly, confront it head on, to drive all care, including palliative care forward for all of us. Maturely addressing the dying person, not prescribing an inaccurate, deadly, pre-emptive strike. Not to go backwards.

“How a society treats its most vulnerable is always the measure of its humanity.”

Ambassador Matthew Rycroft25

Footnotes

UMJ is an open access publication of the Ulster Medical Society (http://www.ums.ac.uk).

REFERENCES

- 1.Association for Palliative Medicine . Fareham, UK: APM of Great Britain and Ireland; 2020. [(cited 2021 Dec 14)]. AMA Physician associated dying web materials. [Internet] Available from: https://apmonline.org/news-events/apm-physician-assisted-dying-web-materials/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Association of Palliative Medicine . Fareham, UK: APM of Great Britain and Ireland; 2020. [(cited 2021 Dec 14)]. Survey Results regarding assisted dying. [Internet] Available from: https://apmonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/press-release-apm-survey-confirms-opposition-tophysician-assisted-suicide-3.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Royal College of Physicians . London: Royal College of Physicians; 2020. [(cited 2021 Dec 14)]. No majority view on assisted dying moves RCP position to neutral. [Internet] Available from: https://www.rcplondon.ac.uk/news/no-majority-view-assisted-dying-moves-rcp-position-neutral. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ottawa, Canada: Health Canada; 2021. [(cited 10/11/22)]. Medical assistance in Dying in Canada 3rd annual report [Internet] Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/medical-assistance-dying/annual-report-2021.html. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oregon Health Public Health Division; 2021. [(Cited 10/11/22)]. Oregon Death with Dignity Act 2021 Data Summary [Internet] Available from: https://www.oregon.gov/oha/PH/PROVIDERPARTNERRESOURCES/EVALUATIONRESEARCH/DEATHWITHDIGNITYACT/Documents/year24.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oregon Health Public Health Division; 2020. [(Cited 10/11/22)]. Oregon Death with Dignity Act 2020 Data Summary [Internet] Available from: https://www.oregon.gov/oha/PH/PROVIDERPARTNERRESOURCES/EVALUATIONRESEARCH/DEATHWITHDIGNITYACT/Documents/year23.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hartog ID, Zomers ML, van Thiel GJ, Leget C, Sachs AP, Uiterwaal CS, et al. Prevalence and characteristics of older adults with a persistent death wish without severe illness: a large cross sectional survey. BMC Geriatrics. 2020;20(1):342–56. doi: 10.1186/s12877-020-01735-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kammeraat M, Koillng P. Den Haag, Netherlands: 2019. [(cited 2021Dec 21)]. Psychiatrische patiënten bij Expertisecentrum:Euthanasie. [Internet] Available from: https://www.eumonitor.eu/9353000/1/j9vvik7m1c3gyxp/vl69rglw8cyv. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oregon Health Public Health, Oregon Violent Death Division; 2021. [(Cited 10/11/22)]. Oregon Health Authority Public Health Division. [Internet] Available from: https://www.oregon.gov/oha/PH/DiseasesConditions/InjuryFatalityData/Pages/nvdrs.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Suicide Mortality by State [Internet] National Centre for Health Statistics, Suicide Mortality by State. [(Cited 10/11/22)]; Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/suicide-mortality/suicide.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones DA. Euthanasia, assisted suicide and suicide rates in Europe [Internet] [(cited 2022 Feb 12)];J Euthan Ment Health. 2022 11:1–35. Available from: https://jemh.ca/issues/open/documents/JEMH%20article%20EAS%20and%20suicide%20rates%20in%20Europe%20-%20copy-edited%20final.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keep Assisted Dying Out of Healthcare [KADOH] [Internet] Used with permission from https://kadoh.uk. London: KADOH; 2021. [(cited 2021 Dec 14)]. Assisted dying and the role of mainstream healthcare. Available from: https://kadoh.uk/ [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prentice A. How terminally ill father desperate to be euthanised asked his devoted son to do him a ‘favour’ and shoot him dead - and why his shattered family are hailing the man who pulled the trigger a ‘hero’[Internet] [(cited 2021 Dec 14)];Daily Mail Australia. 2021 Dec 3; Available from: https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-10270603/Assisted-dying-laws-Cancer-sufferer-asks-son-kill-doctors-refusedeuthanise-him.html. [Google Scholar]

- 14.UK disability activists opposed to assisted suicide [Internet] Not Dead Yet [Website] [(cited 2022 Feb 12)]; Available from: http://notdeadyetuk.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katwiga A. Proof the world wouldn’t be better off without you. [Internet] [(cited 2021 Dec 14)];The Mighty. 2019 Jul 20; Available from: https://themighty.com/2019/07/think-world-would-be-better-off-without-me/ [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yuan Yi Zhu. Why is Canada euthanising the poor? [Internet] The Spectator 30/4/22 Why is Canada euthanising the poor? [(cited 11/11/22)]; Available from: https://www.spectator.co.uk/article/why-is-canadaeuthanising-the-poor-/ [Google Scholar]

- 17.Donne J. Meditation 17. The Works of John Donne. (1839);3:574–575. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Groenewoud JH, van der Heide A, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Willems DL, van der Maas PJ, van der Wal G. Clinical problems with the performance of euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide in The Netherlands. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(8):551–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002243420805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zworth M, Saleh C, Ball I, Kalles C, Chkaroubo A, Kekewich M, et al. Provision of medical assistance in dying: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2020;10(7):e036054. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-036054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sinmyee S, Pandit VJ, Pascaul JM, Dahan A, Heidegger T, Kreienbuhl G, et al. Legal and ethical implications of defining an optimum means of achieving assisted dying. Anaesthesia. 2019;74(5):630–7. doi: 10.1111/anae.14532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tavares T, Oliveira M, Gonçalves J, Trocado V, Perpe´tuo J, Azevedo A, et al. Predicting prognosis in patients with advanced cancer: A prospective study. Palliat Med. 2018;32(2):413–6. doi: 10.1177/0269216317705788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hui D, Ross J, Park M, Dev R, Vidal M, Liu D, et al. Predicting survival in patients with advanced cancer in the last weeks of life: How accurate are prognostic models compared to clinicians’ estimates? Palliat Med. 2020;34(1):126–33. doi: 10.1177/0269216319873261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stone P, Vickerstaff V, Kalpakidou A, Todd C, Griffiths J, Keeley V, et al. Prognostic tools or clinical predictions: Which are better in palliative care? PloS one. 2021;16(4):e0249763. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0249763. Available from: [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.House of Lords . London: UK Parliament; 2005. [(cited 2021 Dec 14)]. Assisted Dying for the Terminally Committee. Session 2004 – 05. [Internet] HL86-II Bill: Evidence. Memorandum by the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. Available from: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/ld/ldasdy.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 25.“How a society treats its most vulnerable is always the measure of its humanity. “Statement by Ambassador Matthew Rycroft of the UK Mission to the UN at the Security Council Open Debate on Children and Armed Conflict. Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Matthew Rycroft CBE 18/6/15. Available from: https://www.gov.uk/government/speeches/how-a-society-treats-its-most-vulnerable-is-always-themeasure-of-its-humanity. [Google Scholar]