Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To describe the relationships between pro-inflammatory biomarkers and self-reported and performance-based physical function and to examine the effect of weight loss on these markers of inflammation.

DESIGN:

Randomized, longitudinal, clinical study comparing subjects eating an energy-restricted diet and participating in exercise training with a control group.

SETTING:

Community-base participants for the Physical Activity, Inflamation and Body Composition Trial.

PARTICIPANTS:

Eighty-seven obese (body mass index (BMI) >30.0 kg/m2) adults aged 60 and older with knee pain and self-report of osteoarthritis.

MEASUREMENTS:

Inflammatory biomarkers (interleukin 6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), C-reactive protein, and soluble receptors for TNFα (sTNFR1 and sTNFR2)) and self-reported (Western Ontario and McMaster University Osteoarthritis Index questionnaire) and performance-based (6-minute walk distance and stair climb time) measures of physical function at baseline and 6 months.

RESULTS:

Mean (standard error of the mean) weight loss was 8.7% (0.8%) in the intervention group, compared with 0.0% (0.7%) in the control group. sTNFR1 was significantly less in the intervention group than in the control group at 6 months. sTNFR1 and sTNFR2 predicted stair climb time at baseline. Change across the 6-month intervention for sTNFR2 was an independent predictor for change in 6-minute walk distance.

CONCLUSION:

These results indicate that an intensive weight-loss intervention in older obese adults with knee pain can help improve inflammatory biomarkers and that changes in these concentrations showed associations with physical function.

Keywords: physical function, weight loss, inflammatory biomarkers, older adults, osteoarthritis

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the leading cause of impairment in physical function in the United States, with the knee joint being a chief site for the disease.1 Joint pain is a primary clinical symptom associated with OA, with knee pain being prominent in daily living with knee OA.2 Obesity is a primary risk factor for OA of the knee; individuals with a body mass index (BMI) greater than 30.0 kg/m2 were four times as likely to have knee OA as those with a BMI of 25.0 kg/m2 or less.3,4 The link between obesity and OA may lie in part with inflammation, because obesity and OA are both associated with high levels of biomarkers of inflammation: interleukin 6 (IL-6), tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα), TNFα soluble receptors sTNFR1 and sTNFR2, and C-reactive protein (CRP).5,6 Obesity is regarded as a low-grade inflammatory condition, because adipose tissue produces and secretes several proinflammatory cytokines, including IL-6 and TNFα.7 Thus, it has been hypothesized that obesity’s role as a risk factor for OA and other chronic conditions originates from the elevated production of these biomarkers in obese people.8,9 Furthermore, CRP, an acute-phase reactant protein whose production IL-6 stimulates in the liver, has been shown to predict OA progression over several years.10 Proinflammatory cytokines alter the development, progression, or both of OA through up-regulation of metalloproteinase gene expression, stimulation of reactive oxygen species production, alteration of chondrocyte metabolism, and possibly increased osteoclastic bone resorption.6,11–13

Impairments in physical function and disability are also associated with obesity and high levels of proinflammatory biomarkers.14–16 It is reasonable to suggest that weight loss will lead to improvements in function, with a lowering of inflammatory markers. In previous research, it was found that mild weight loss (~ 5% from baseline) using diet changes alone or a combination of diet and exercise interventions resulted in improvements in function in older obese and overweight adults with knee OA over 18 months.17 In this same cohort, the dietary-induced weight-loss intervention produced significant reductions in CRP, IL-6, and sTNFR1.18 There were also significant associations between physical function measures and sTNFR1 and sTNFR2.19 It is reasonable to suggest that there is a dose response, because more-extreme weight loss resulted in greater reductions in inflammatory markers. Decreases in CRP of 32% were observed with a weight loss program producing a 15% decrease in body weight.20 After gastric bypass surgery, more than 50% changes in CRP and IL-6 were produced, although the massive weight loss did not alter plasma concentrations of TNFα.21,22 Over 6 weeks of weight loss, approximately 33% decreases in CRP and IL-6 were observed in morbidly obese individuals.23

For the present study, inflammatory biomarkers were measured in older obese adults with knee pain and self-reported OA, and relationships between inflammation and physical function were determined in a cross-sectional analysis. A randomized, clinical trial of intensive 6-month weight-loss therapy (weight loss goal of 10%) emphasizing dietary and physical activity behaviors was then performed to study changes in inflammatory markers. One aim of this study was to describe the relationships between plasma markers of inflammation and self-reported and performance-based physical function at baseline and after weight loss. The second aim was to examine differences in the proinflammatory biomarkers between groups of subjects who lost weight after an intensive weight-loss intervention and those whose weight was stable. Earlier results from this study demonstrated an improvement in physical function after the 6-month weight-loss intervention.24

METHODS

Participants

Participants were recruited from the community for the Physical Activity, Inflammation, and Body Composition Trial. Eligibility criteria were BMI or 30.0 kg/m2 or greater, aged 60 and older, knee pain and self-reported physician-diagnosed knee OA, self-reported difficulty performing at least one of the following activities because of knee pain: lifting and carrying groceries, walking one-quarter of a mile, getting in and out of a chair, and going up and down stairs.

Individuals were excluded if they were unable to complete the intervention or had an unstable medical condition or a condition in which rapid weight loss or exercise is contraindicated. Examples of these medical conditions include unstable angina pectoris, frailty (defined as lack of independence and inability to perform daily activities independently), certain types of lung disease, and advanced osteoporosis. Individuals with recent cancer or who were currently undergoing treatment for cancer were excluded from the study. Individuals were also excluded if they were unable to come to the laboratory for testing or to the facility for the intervention. All randomized participants gave written informed consent to participate in the study according to the guidelines of the Wake Forest University institutional review board. A total of 499 individuals were screened by telephone; of these, 132 (26%) met the eligibility requirements and were willing to schedule a screening visit. The remaining subjects were not interested (n = 123) or were not eligible (n = 244). Eighty-seven of 132 (66%) were randomized. The top three reasons for failing screening were low BMI (n = 60), already participating in another research study (n = 33), and already scheduled for a knee replacement (n = 27). Further details of eligibility, interventions, and measures have been described in an earlier publication.24

Design and Intervention

Participants were randomized into a control group or an intensive weight-loss group for the 6-month intervention.

Intensive Weight-Loss Intervention

The weight loss goal was 10% of initial body weight by the end of the 6-month trial. The intervention incorporated partial meal replacement, nutrition education, and lifestyle behavior modifications. The lowest level of dietary energy provided was 4,600 kJ/d for women and 5,022 kJ/d for men. The energy distribution goal for each individual was approximately 20% from protein, 25% from fat, and 55% from carbohydrates. A maximum of two meal replacements (shakes and bars) were provided. For the third meal, a weekly menu plan with recipes was given for participants to follow. Recommended snacks included fruits or vegetables providing approximately 400 to 500 kJ/d.

Weekly behavioral and educational sessions were held for those in the intervention group. These sessions were conducted in group (n = 6–12 per group) (3 times per month) and individual (1 time per month) formats for a total of 60 minutes at each session. A registered dietitian and an exercise physiologist with expertise in behavior therapy with older adults led the sessions. All participants were instructed in behavior modification, with advice on food selection, meal portion, dietary fat control, relapse prevention, and self-monitoring techniques.

Intervention participants also engaged in a structured, facility-based exercise training program 3 days per week for 60 minutes per session. The exercise program consisted of a warm-up phase (5 minutes), an aerobic phase (15 minutes), a strength phase (20 minutes), a second aerobic phase (15 minutes), and a cool-down phase (5 minutes). The primary mode of aerobic training was walking, with occasional use of cycle ergometers. The exercise intensity for the aerobic exercise portion of the training was 50% to 85% of the age-predicted heart rate reserve. Strength training included four stations: leg extension, leg curl, heel raise, and step-ups using ankle cuff weights, weighted vest, and resistance training equipment. Two sets of 12 repetitions were performed at each station, with resistance being progressively increased during the intervention as strength improved. Lower-body flexibility exercises were performed at each session.

Control Group

Participants randomized to the control group met bimonthly in a group format with presentations on general health, OA, and exercise. Individuals were weighed at these meetings and encouraged to maintain their weight throughout the 6-month study. Bimonthly newsletters were sent to participants in Months 1, 3, and 5 describing other health facts on topics such as nutrition, pertinent disease topics, aging, and other health issues in older adults. At the close of the study, individuals in the control group were provided with weight-loss information on diet and exercise, a 2month supply of meal replacements and snack food provisions, a personalized exercise consultation, and 1 month of the facility-based exercise program as an incentive and reward for participation in the study.

Measurements

Variables were measured at baseline and after the 6-month intervention.

Physical Function

Self-Report.

Self-reported physical function was measured using the Western Ontario and McMaster University (WOMAC) Osteoarthritis Index,25 which the Osteoarthritis Research Society International recommends as the measure of choice in this population. The 24-item WOMAC index was developed for use in individuals who have OA of the hip or knee and is a health-status instrument that assesses a participant’s perception of pain (5 questions), joint stiffness (2 questions), and physical function (17 questions).

Performance.

Physical performance tasks included 6-minute walk distance and stair climb time. Briefly, for the first test, participants were instructed to walk as far as possible in a 6-minute time period on an established course. They were not allowed to carry a watch and were not provided with feedback during the trial. Performance was measured as the total distance covered. The timed stair climb involved ascending and descending a flight of five stairs as quickly as possible. During the ascent, participants were instructed to grasp the handrail with their left hand and without hesitation turn around on the platform at the top and descend using the same hand to hold the rail. Performance was measured as the time required to complete the task.

Body Weight, Height, and Waist Circumference

These measures were obtained using standard techniques. Briefly, weight and height were determined with shoes and jackets or outer garments removed. Instruments were calibrated weekly. Waist circumference was obtained by placing a measuring tape in a horizontal plane around the abdomen at the level of the iliac crest, ensuring that the tape did not compress the skin but was snug and parallel to the floor. The measurement was made at the end of a normal expiration.

Inflammatory Biomarkers

Before the blood sampling, participants were queried about their medication use and health status. Any participant who reported currently taking any antibiotic medication or having an overt infection (e.g., urinary tract, respiratory) or fever (˃99.0°F) was rescheduled. Whole blood samples were collected in blood collection tubes treated with ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid from venipuncture in the early morning (between 7 and 9 a.m.) after a 12-hour fast. Samples were put immediately on ice and separated using centrifugation for 20 minutes at 4°C within 30 minutes of collection. After separation, specimens were stored in 1-mL aliquots at −80°C until analyses in the Cytokine Core laboratory at Wake Forest University Health Sciences.

Fasting plasma concentrations of IL-6, TNFα, sTNFR1, and sTNFR2 were determined according to enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays using Quantikine immunoassay kits (high sensitivity for IL-6 and TNFα; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). CRP was measured using an automated immunoanalyzer (Immulite, Diagnostics Products Corp., Los Angeles, CA). All samples were measured in duplicate, and the average of the two values was used for data analyses. Duplicate samples thatdid not provide a coefficient of variation of less than 15% were reanalyzed, and all values were averaged for data analyses. The intraassay and interassay coefficients of variation (CVs) were 7% and 16%, respectively, for IL-6; 8% and 23%, respectively, for TNFα; and less than 15% for the soluble receptor assays. The interassay and intraassay CVs for the CRP assay (ALPCO, Windham, NH) were 8% and 7%, respectively. Samples that were above the maximum detection limit were diluted (1:2) and reanalyzed.

Data Analyses

The baseline and follow-up measures of biomarker concentrations were not normally distributed. The log values were obtained for each, and the change between measures was determined. Univariate analysis of covariance was used to compare differences between control and weight loss groups for the log change in inflammatory biomarkers between the baseline and 6-month values. Covariates included baseline values for the specific marker, BMI, sex, and age. Differences between groups were deemed significant at P≤.05. Forward linear regression was used to determine the relationship between log-transformed inflammatory marker levels and physical function at baseline and for the change across the intervention in the physical function measures and the log of the inflammatory markers. Data were pooled, and results for both linear regression analyses are presented for the two groups (intervention and control) combined. These analyses were adjusted for age, sex, race, BMI, comorbid conditions, and nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug (NSAID) use. Analyses were controlled for chronic diseases as reported in the medical history. These included history of myocardial infarction, lung disease, diabetes mellitus, or cancer. NSAID use was obtained from records of medicine and supplement use. Participants brought in their medications at baseline, and study staff recorded the name and dosage. Linear regression was also used to examine whether weight change predicted the change in log levels of the inflammatory markers. Baseline weight and marker levels were used as covariates. Spearman correlations were performed between the five inflammatory biomarkers and BMI, waist, body weight, age, and intervention adherence. Values for dependent variables are presented as means (standard error of the means). All analyses were performed on SPSS version 15.0 (SAS Institute, Inc., Chicago, IL).

RESULTS

Demographics

Baseline characteristics for the two groups are shown in Table 1. There were no statistical differences between the two groups at baseline in variables assessed. Across the entire cohort, mean age was 69.7 (0.6) (range 60–84). Mean BMI was 34.6 (0.5) kg/m2. Most of the participants were female, and nearly 70% were taking NSAIDs for relief of pain from their arthritis. More than 80% of all participants were taking at least one form of analgesic or supplement for their OA, including NSAIDS, acetaminophen, and glucosamine. This was similar between the groups (84% intervention, 81% control). Approximately one in five had cancer, diabetes mellitus, or lung disease. The most common types of cancer were skin, breast, and prostate.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics According to Group

| Variable | Control | Intervention |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age, mean (SEM) | 69.5 (1.0) | 69.8 (1.0) |

| Body weight, kg, mean (SEM) | 99.6 (2.7) | 97.8 (3.0) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2, mean (SEM) | 34.4 (0.7) | 34.9 (0.8) |

| Waist circumference, cm, mean (SEM) | 110.8 (2.5) | 111.6 (2.9) |

| Female, % | 56.7 | 64.9 |

| Caucasian, % | 93.5 | 88.6 |

| Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drug usage, % of participants | 61.3 | 75.7 |

| Comorbidities (% of participants) | ||

| Myocardial infarction | 3.3 | 8.3 |

| Cancer | 20.0 | 22.9 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 16.7 | 20.0 |

| Lung diseases | 20.0 | 15.2 |

There were no statistical differences between groups for any of the measures at baseline.

SEM = standard error of the mean.

Intervention Adherence

Participants in the intervention group attended 77.5% of the exercise sessions and 75% of the nutrition sessions over the 6-month intervention. The highest attendance rate for the exercise sessions occurred during Month 1 (83%), and attendance was lowest in Month 6 (72%).

Weight Loss

Initial body weights were 99.6kg for the intervention group and 98.6kg for the control group. These changed to 98.9 (2.9) and 89.8 (2.7), respectively, at 6 months. There was a loss of 8.7% (0.8%) of initial body weight after 6 months of the intervention for the intervention group, whereas the control group had no change in weight over this time (0.0% (0.7%)).

Physical Function

Results for the self-report and performance scores for physical function were combined for the two groups and are shown in Table 2. Significant differences were found between the baseline and 6-month measurements for each variable, except for WOMAC stiffness, which had a strong trend toward significance, at P=.08.

Table 2.

Physical Function Measures at Baseline and 6 Months for Both Groups Combined

| Baseline (n = 67) | 6 Months (n = 67) | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

||

| Variable | Mean (Standard Error of the Mean) | |

|

| ||

| Western Ontario and McMaster University Osteoarthritis Index | ||

| Sum | 33.9 (1.9) | 25.9 (1.7)* |

| Pain | 6.1 (0.4) | 4.8 (0.3)* |

| Stiffness | 3.4 (0.2) | 2.9 (0.2)† |

| Function | 24.4 (1.4) | 18.2 (1.3)* |

| 6-minute walk distance, m | 445.3 (11.2) | 493.4 (12.4)* |

| Stair climb time, seconds | 9.5 (0.5) | 9.2 (0.7)* |

Significant difference between baseline and 6-month measurements (P<.05).

P = .08.

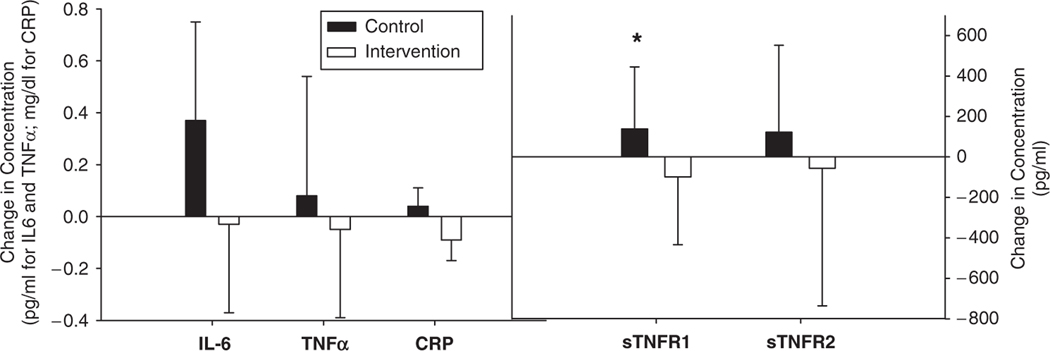

Treatment Effect on Inflammatory Biomarkers

Because the change in plasma inflammatory biomarkers between baseline and 6 months was not normally distributed, the logs of baseline and 6-month concentrations for the inflammatory markers were calculated. The ratio for these values was used as the log change measurement. This value was used in the model. Covariates were BMI and baseline values of the cytokine concentration. For ease of comparison and further description of the distribution of the variables, the nontransformed means for baseline and 6-month measurements, as well as the median score and interquartile range, are shown in Table 3 for each marker for the two groups. The nontransformed change values in the inflammatory biomarkers are shown in Figure 1. Analysis showed a statistical difference between the groups at 6 months for sTNFR1 (P=.003). No other markers were significantly different between the groups.

Table 3.

Plasma Concentrations of Inflammatory Biomarkers at Baseline and 6 Months for Both Groups

| Intervention (n = 31) |

Control (n = 36) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Baseline | 6 Months | Baseline | 6 Months |

|

| ||||

| Interleukin-6 (pg/mL) | ||||

| Mean | 4.26 | 4.63 | 3.89 | 3.74 |

| SEM | 0.58 | 0.77 | 0.41 | 0.42 |

| Median | 2.93 | 3.30 | 3.14 | 3.07 |

| Interquartile range | 3.68 | 3.82 | 2.73 | 3.08 |

| TNFα, pg/mL | ||||

| Mean | 1.18 | 1.26 | 1.18 | 1.13 |

| SEM | 0.14 | 0.15 | 0.13 | 0.15 |

| Median | 0.97 | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.82 |

| Interquartile range | 0.69 | 0.92 | 0.71 | 0.69 |

| sTNFR1, pg/mL | ||||

| Mean | 1,522 | 1,662 | 1,428 | 1,330 |

| SEM | 82 | 99 | 72 | 66 |

| Median | 1,484 | 1,537 | 1,306 | 1,295 |

| Interquartile range | 391 | 313 | 388 | 431 |

| sTNFR2, pg/mL | ||||

| Mean | 2,567 | 2,689 | 2,572 | 2,516 |

| SEM | 118 | 139 | 119 | 111 |

| Median | 2,552 | 2,692 | 2,481 | 2,402 |

| Interquartile range | 860 | 961 | 647 | 743 |

| C-reactive protein, mg/dL | ||||

| Mean | 0.58 | 0.62 | 0.72 | 0.62 |

| SEM | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.15 |

| Median | 0.37 | 0.44 | 0.47 | 0.42 |

| Interquartile range | 0.63 | 0.60 | 0.66 | 0.47 |

SEM = standard error of the mean; TNFα = tumor necrosis factor alpha; sTNFR = soluble TNF receptor.

Figure 1.

Change in concentrations of inflammatory biomarkers from baseline to 6 months. *Indicates P≤.05 for change in concentrations of inflammatory biomarkers between weight stable and weight loss groups.

IL-6 = interleukin-6; TNFα = tumor necrosis factor alpha; CRP = c-reactive protein; sTNFR1 = soluble TNF receptor 1.

Associations Between Baseline Values of Log Inflammatory Biomarkers and Physical Function

Initial associations were observed between inflammatory biomarkers and physical function using an unadjusted model. These results indicated significant associations between log sTNFR1 and stair climb time (standardized β coefficient=0.255, P=.04) and between log CRP and distance walked (standardized β coefficient= −0.324, P=.008). Subsequent adjustments were made in the model for age, sex, race, baseline BMI, comorbid conditions, and NSAID use. Log sTNFR1 remained an independent predictor of stair climb time (standardized β coefficient=0.389, P=.003), with sTNFR1 contributing 15.1% of the variance in stair climb time. Log of sTNFR2 was also an independent predictor of stair climb time (standardized β coefficient=0.317, P=.02), with sTNFR2 contributing 10.1% of the variance. Higher levels of log sTNFR1 and log sTNFR2 at baseline were associated with longer stair climb time (i.e., worse function). Using the adjusted model, CRP was no longer associated with distance walked.

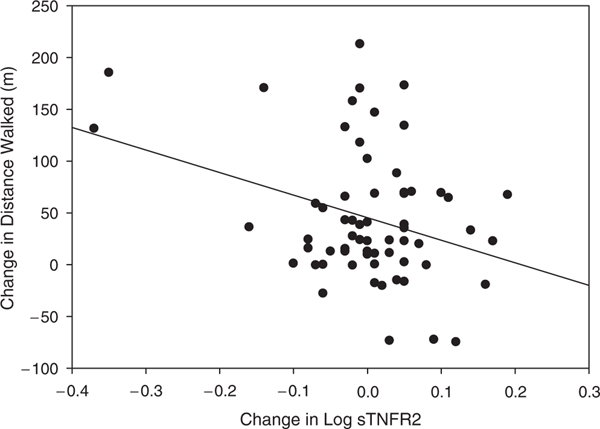

Associations Between Changes in Log Inflammatory Biomarkers and Physical Function

Initial associations were observed using an unadjusted model. These analyses indicated significant associations between the changes in log sTNFR1 and log sTNFR2 and 6-minute distance walked (standardized β coefficient = −0.282, P = .03 and β = −0.327 and P = .009, respectively). After appropriate adjustments, linear regression analysis indicated that the change in log sTNFR2 was an independent predictor for the change in 6-minute distance walked (standardized β coefficient = −0.289, P = .04), contributing 6.5% of the variance (Figure 2). A reduction in sTNFR2 was related to a greater distance walked. sTNFR1 was no longer associated with distance walked after adjustments.

Figure 2.

Scatterplot of changes in log sTNFR2 and 6-minute walk distance. Groups are combined and data are presented together. sTNFR2 = soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor 2.

Associations Between Weight, BMI, Waist Circumference, Age, Intervention Adherence, and Inflammatory Markers

Baseline values of the inflammatory biomarkers were not correlated with weight, waist circumference, age, or intervention adherence (intervention group only). There was a weak inverse correlation between baseline values of BMI and TNFα (r = −0.250, P = .04). Correlations between the inflammatory markers showed that sTNFR1 was related to IL-6 (r = 0.475, P < .001), TNFα (r = 0.339, P = .005), and sTNFR2 (r = 0.550, P < .001) at baseline. No other biomarkers were significantly related to each other. The change in body weight demonstrated an independent association with changes in log values for sTNFR1 (standardized b coefficient = 0.308, P = .01), adjusting for baseline body weight and inflammatory biomarker concentrations. No other biomarkers showed significant relationships with changes in body weight.

DISCUSSION

The effect an intensive weight loss program has on measures of inflammation and physical function in an older obese adult population has not been well studied. Limitations in earlier studies include a lack of significant numbers of older adults, limited weight loss (<5%), short duration of the intervention, and insufficient measures of physical function. The current study expanded on earlier trials by inducing a greater weight loss (goal of 10%), recruiting exclusively older adults (aged ≥60) with a BMI of 30.0 kg/m2 or greater, having a 6-month follow-up period, and assessing physical function using self-reported questionnaires and performance-based measures. In addition, the intervention group in the present analysis had better physical function and less knee pain than the control group at the end of the 6-month intervention.24 The finding in the present study that sTNFR1 was lower in the intervention than in the control group at follow-up supports the hypothesis that a reduction in inflammatory load may contribute to an improvement in physical function.

A significant lowering of lean body mass was also found in the intervention group after the intensive weight loss intervention; despite this loss of lean tissue, knee muscle strength was maintained, and muscle quality improved for the intervention group.26 Taken together with the current findings, these data suggest that the improvement in function from the intervention may be mediated through these observed changes in strength and inflammation. Further support for a link between inflammation, strength, and body composition comes from observational data showing that higher IL-6 and TNFα levels are associated with lower muscle mass and lower muscle strength in elderly persons27 and from experimental data in animals showing that administration of IL-6 and TNFα to laboratory animals decreases protein synthesis and increases muscle protein breakdown.28,29

In addition to alterations in inflammatory markers and strength, changes in function may be mediated through the reduction in fat mass from the intervention, because in older adults, higher fat mass is associated with lower physical performance and self-reported disability.24 Furthermore, fat infiltration of skeletal muscle is a predictor of mobility limitation in older adults,30 and intensive weight loss reduces fat content of skeletal muscle.31 Additional evidence is needed from randomized, controlled, clinical trials investigating weight loss, fat infiltration, inflammation, and physical function in obese older adults with knee pain.

The current results are consistent with the reduction in sTNFR1 previously observed with more-modest dietary-induced weight loss in persons of similar age, sex distribution, race, BMI, and comorbidities,18 although in contrast to the current study, the earlier investigation reported reductions in CRP and IL-6 along with sTNFR1 in participants randomized to the dietary weight-loss interventions; no such reduction in CRP or IL-6 was observed in the current study. There have been no other weight-loss studies that have measured inflammatory markers in obese participants with impaired physical function from knee pain, although comparisons with other weight-loss studies using different populations showed some similarities in findings. One study also found selected mild declines in plasma sTNFR1 of approximately 7.5%, but not sTNFR2, after a 3-week low-energy diet (<4,200 kJ/d).32 Contrastingly, in a cohort of morbidly obese individuals with glucose intolerance undergoing massive weight loss from gastric bypass surgery, significant reductions in IL-6 and CRP of 23% and 70%, respectively, were observed over 14 months of follow-up.21 Other weight-loss studies have also demonstrated significant decreases in CRP and IL-6 with greater weight loss, although these were not in individuals with impaired function or older in age.22,23 The discrepancy and apparent lack of effect on inflammatory markers with the current study may lie in other factors besides the level of weight loss and duration of follow-up, such as age of participants and stage of obesity; degree and number of comorbidities and inflammatory conditions, including OA, insulin resistance, and atherosclerosis; length of observation period; inclusion of physical activity in the weight-loss program; and study design. The level of weight loss achieved and time of follow-up differed for these studies, although all showed significant changes in these inflammatory biomarkers.

Physical activity and exercise training have been shown to have an antiinflammatory effect in some populations through reductions in resting levels of a variety of inflammatory biomarkers, most prominently IL-6, CRP, and TNFα; this response is not entirely clear, because discrepant findings are apparent in the literature. One study found no change from exercise training for skeletal muscle TNFα,33 although observational and a few prospective intervention trials have shown lower proinflammatory cytokines for those that engage in exercise training than in sedentary counterparts.34,35 Acute changes are also apparent after a single exercise bout, with a proinflammatory response observed, as demonstrated by an increase in circulating proinflammatory biomarker concentrations, primarily after an intense or extended exercise session.36 Participants for the current investigation had blood drawn in the morning after an overnight fast before exercising, thereby negating the potential for a rise in markers from a recent exercise bout.

Additionally, the type of weight-loss intervention (rate of weight loss, nutrient composition) employed may be a factor affecting inflammation changes. For example, certain types of fatty acids are known to modulate inflammation, with omega 3 fatty acids (including eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids) reducing CRP and IL-6 and trans fatty acids raising CRP,37,38 although these findings have mostly been shown in weight-stable individuals. Moreover, one study showed that changes in CRP were related to the amount of weight loss and were independent of macronutrient content of the diet.39 Furthermore, their diet composition at initiation of the study may have affected the response of participants in the weight-loss intervention. Data from several cross-sectional studies, including the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey and the Nurses Health Study, revealed that a diet higher in saturated and trans fatty acids is associated with higher levels of inflammatory markers, including CRP, IL-6, and TNFα.38 Total amount of dietary fat can also play a role, with higher-fat diets in intervention studies resulting in greater inflammation. For example, in individuals habitually consuming a diet high in saturated fat, substituting alpha linolenic acid for saturated fatty acids resulted in a greater reduction in CRP than those eating a diet higher in monounsaturated fatty acids. This occurred even though the amount of alpha linolenic acid was similar during the intervention for the groups.40 The current study did not attempt to manipulate or control for specific fatty acid intake or for other nutrients, such as antioxidants, that vary between participants. This may provide rationale for the inconsistencies in results and account for the observed differences in outcomes from the various studies.

Previous work indicates that greater levels of inflammation are related to impaired physical function and disability.15,16,41 Chronic inflammation may contribute to reductions in skeletal muscle mass with aging,42 which underlies reductions in mobility and function in this population. For example, high levels of IL-6 have been shownto be a strong predictor of subsequent disability over a 4-year follow-up,41 although in contrast to these observations, the current analysis did not show consistent associations between the inflammatory markers and physical function measures taken at baseline or in change in markers and function from the intervention. The exceptions were that higher sTNFR1 and sTNFR2 were associated with slower stair climb time. Both markers independently predicted approximately 10% to 15% of the variance in the stair climb time. An earlier trial of mild weight loss in older obese adults with knee OA found that IL-6 was related to walking speed assessed during a 6-minute walk.19 In a larger previous study, a relationship was seen between self-reported pain and function and TNFα soluble receptors at baseline; but no such relationships were observed in the current study.

In examining the relationships between the relative change in variables over the course of the intervention, the change in log of sTNFR2 was an independent predictor of 6-minute distance walked, explaining nearly 10% of the variance. A reduction in inflammatory response was associated with improvement in the physical performance task. Although only limited associations between inflammation and physical function were shown, it is important to recognize that there were no associations demonstrating untoward outcomes.

Inclusion criteria for the study included knee pain and self-reported physician diagnosis of knee OA. A potential limitation of the study is that the severity of the OA was not confirmed or graded. This might have provided further insight into the responses observed with the inflammatory biomarkers, because severity of knee OA is a factor in the level of circulating inflammatory biomarkers. One study found a higher concentration of TNFα in individuals with more severe chondral damage to the knee.43 CRP levels are also predictive of disease progressions, with women whose disease progressed at least 1 Kellgren-Lawrence grade over a 4-year period having higher baseline values than women whose disease did not progress.10 It is uncertain how disease severity may be a modifier of inflammation responses to a behavioral weight-loss therapy, because disease severity at entry into this study was not determined.

Results from earlier studies suggest that the soluble receptors for TNFα are more sensitive to change from interventions and thus may more accurately reflect the metabolism of TNFα than the actual levels of the cytokine.18,19,44 This is consistent with findings from the current study, because the intervention lowered sTNFR1 but not TNFα, and significant correlations were apparent for physical performance and sTNFR1. Others have also shown the soluble receptor for IL-6 to be sensitive to change and related to various disease states, but this protein was not measured in the current study, because changes in the receptor after weight-loss treatment in older adults was not seen in previous studies.18

The current study was limited in that it did not determine levels of antiinflammatory cytokines, nor were all proinflammatory markers measured. In addition, concentrations of the markers were assessed in blood instead of synovial fluid of the knee, which would be the purported site of action for these signals. Therefore, lack of change in inflammation and their association with physical function may be due to choice of markers measured.

In conclusion, these findings illustrate that weight loss approaching 10% over 6 months produced minor effects on plasma inflammatory markers in obese older adults with knee OA. There were weak relationships between measures of physical function and inflammatory markers. Different types of nutrients consumed during weight loss and normal dietary intake before initiation of the weight-loss treatment may have confounded the results. In addition, the focus on older adults with knee pain and self-reported physician diagnosis of knee OA and obesity, both known to be low-grade inflammatory conditions, may have led to lower response of inflammatory biomarkers to the weight-loss intervention.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was performed at Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

This project was partially funded by SlimFast Nutrition Institute, the Wake Forest University Claude D. Pepper Older American Independence Center (National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant P30 AG21332), and the Wake Forest University General Clinical Research Center (NIH M01-RR07122).

Sponsor’s Role:

The sponsor had a role in the intervention design.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The editor in chief has reviewed the conflict of interest checklist and has determined the authors have no conflict of interest with this article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Prevalence of disabilities and associated health conditions among adults—United States, 1999. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2001;50:120–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Maly MR, Krupa T. Personal experience of living with knee osteoarthritis among older adults. Disabil Rehabil 2007;29:1423–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Felson DT, Zhang Y, Anthony JM et al. Weight loss reduces the risk for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in women. The Framingham Study [see comments]. Ann Intern Med 1992;116:535–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oliveria SA, Felson DT, Cirillo PA et al. Body weight, body mass index, and incident symptomatic osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Epidemiology 1999;10:161–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Das UN. Is obesity an inflammatory condition? Nutrition 2001;17:953–966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pelletier JP, Martel-Pelletier J, Abramson SB. Osteoarthritis, an inflammatory disease: Potential implication for the selection of new therapeutic targets. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:1237–1247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohamed-Ali V, Goodrick S, Rawesh A et al. Subcutaneous adipose tissue releases interleukin-6, but not tumor necrosis factor-alpha, in vivo. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1997;82:4196–4200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bullo M, Garcia-Lorda P, Megias I et al. Systemic inflammation, adipose tissue tumor necrosis factor, and leptin expression. Obes Res 2003;11:525–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yudkin JS, Kumari M, Humphries SE et al. Inflammation, obesity, stress and coronary heart disease: Is interleukin-6 the link? Atherosclerosis 2000; 148:209–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spector TD, Hart DJ, Nandra D et al. Low-level increases in serum C-reactive protein are present in early osteoarthritis of the knee and predict progressive disease. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:723–727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fernandes JC, Martel-Pelletier J, Pelletier JP. The role of cytokines in osteoarthritis pathophysiology. Biorheology 2002;39:237–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van de Loo FA, Joosten LA, van Lent PL et al. Role of interleukin-1, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and interleukin-6 in cartilage proteoglycan metabolism and destruction. Effect of in situ blocking in murine antigen- and zymosan-induced arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1995;38:164–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Saxne T, Lindell M, Mansson B et al. Inflammation is a feature of the disease process in early knee joint osteoarthritis. Rheumatol (Oxford) 2003;42: 903–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferraro KF, Booth TL. Age, body mass index, and functional illness. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 1999;54B:S339–S348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ferrucci L, Penninx BW, Volpato S et al. Change in muscle strength explains accelerated decline of physical function in older women with high interleukin-6 serum levels. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:1947–1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Penninx BW, Kritchevsky SB, Newman AB et al. Inflammatory markers and incident mobility limitation in the elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;52: 1105–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Messier SP, Loeser RF, Miller GD et al. Exercise and dietary weight loss in over weight and obese older adults with knee osteoarthritis: The arthritis, diet, and activity promotion trial. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:1501–1510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nicklas BJ, Ambrosius W, Messier SP et al. Diet-induced weight loss, exercise, and chronic inflammation in older, obese adults: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;79:544–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Penninx BW, Abbas H, Ambrosius Wet al. Inflammatory markers and physical function among older adults with knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol 2004; 31:2027–2031. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tchernof A, Nolan A, Sites CK et al. Weight loss reduces C-reactive protein levels in obese postmenopausal women. Circulation 2002;105:564–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kopp HP, Kopp CW, Festa A et al. Impact of weight loss on inflammatory proteins and their association with the insulin resistance syndrome in morbidly obese patients. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2003;23:1042–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manco M, Fernandez-Real JM, Equitani F et al. Effect of massive weight loss on inflammatory adipocytokines and the innate immune system in morbidly obese women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2006;92:483–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Salas-Salvado J, Bullo M, Garcia-Lorda P et al. Subcutaneous adipose tissue cytokine production is not responsible for the restoration of systemic inflammation markers during weight loss. Int J Obes (London) 2006;30:1714–1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miller GD, Nicklas BJ, Davis C et al. Intensive weight loss program improves physical function in older obese adults with knee osteoarthritis. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:1219–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH et al. Validation study of WOMAC: A health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol 1988;15:1833–1840. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang X, Miller GD, Messier SP et al. Knee strength maintained despite loss of muscle mass during intensive weight loss in older obese adults with knee osteoarthritis. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2007;62A:866–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Visser M, Pahor M, Taaffe DR et al. Relationship of interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha with muscle mass and muscle strength in elderly men and women: The Health ABC Study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2002; 57A:M326–M332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charters Y, Grimble RF. Effect of recombinant human tumour necrosis factor alpha on protein synthesis in liver, skeletal muscle and skin of rats. Biochem J 1989;258:493–497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goodman MN. Interleukin-6 induces skeletal muscle protein breakdown inrats. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med 1994;205:182–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Visser M, Goodpaster BH, Kritchevsky SB et al. Muscle mass, muscle strength, and muscle fat infiltration as predictors of incident mobility limitations in well-functioning older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2005;60A : 324–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mazzali G, Di Francesco V, Zoico E et al. Interrelations between fat distribution, muscle lipid content, adipocytokines, and insulin resistance: Effect of moderate weight loss in older women. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;84: 1193–1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bastard JP, Jardel C, Bruckert E et al. Elevated levels of interleukin 6 are reduced in serum and subcutaneous adipose tissue of obese women after weight loss. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:3338–3342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ferrier KE, Nestel P, Taylor A et al. Diet but not aerobic exercise training reduces skeletal muscle TNF-alpha in overweight humans. Diabetologia 2004;47:630–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith JK, Dykes R, Douglas JE et al. Long-term exercise and atherogenic activity of blood mononuclear cells in persons at risk of developing ischemic heart disease. JAMA 1999;281:1722–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldhammer E, Tanchilevitch A, Maor I et al. Exercise training modulates cytokines activity in coronary heart disease patients. Int J Cardiol 2005; 100:93–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siegel AJ, Stec JJ, Lipinska I et al. Effect of marathon running on inflammatory and hemostatic markers. Am J Cardiol 2001;88:918–920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Das UN, Ramos EJ, Meguid MM. Metabolic alterations during inflammation and its modulation by central actions of omega-3 fatty acids. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2003;6:413–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lopez-Garcia E, Schulze MB, Meigs JB et al. Consumption of trans fatty acids Is related to plasma biomarkers of inflammation and endothelial dysfunction. J Nutr 2005;135:562–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Brien KD, Brehm BJ, Seeley RJ et al. Diet-induced weight loss is associated with decreases in plasma serum amyloid a and C-reactive protein independent of dietary macronutrient composition in obese subjects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:2244–2249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paschos GK, Rallidis LS, Liakos GK et al. Background diet influences the anti-inflammatory effect of alpha-linolenic acid in dyslipidaemic subjects. Br J Nutr 2004;92:649–655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ferrucci L, Harris TB, Guralnik JM et al. Serum IL-6 level and the development of disability in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1999;47:639–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roubenoff R.Inflammatory and hormonal mediators of cachexia. J Nutr 1997;127(5 Suppl):1014S–1016S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marks PH, Donaldson ML. Inflammatory cytokine profiles associated with chondral damage in the anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee. Arthroscopy 2005;21:1342–1347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dayer JM, Fenner H. The role of cytokines and their inhibitors in arthritis. Baillieres Clin Rheumatol 1992;6:485–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]