Abstract

The ellipsoid body (EB) is a major structure of the central complex of the Drosophila melanogaster brain. Twenty-two subtypes of EB ring neurons have been identified based on anatomic and morphologic characteristics by light-level microscopy and EM connectomics. A few studies have associated ring neurons with the regulation of sleep homeostasis and structure. However, cell type-specific and population interactions in the regulation of sleep remain unclear. Using an unbiased thermogenetic screen of EB drivers using female flies, we found the following: (1) multiple ring neurons are involved in the modulation of amount of sleep and structure in a synergistic manner; (2) analysis of data for ΔP(doze)/ΔP(wake) using a mixed Gaussian model detected 5 clusters of GAL4 drivers which had similar effects on sleep pressure and/or depth: lines driving arousal contained R4m neurons, whereas lines that increased sleep pressure had R3m cells; (3) a GLM analysis correlating ring cell subtype and activity-dependent changes in sleep parameters across all lines identified several cell types significantly associated with specific sleep effects: R3p was daytime sleep-promoting, and R4m was nighttime wake-promoting; and (4) R3d cells present in 5HT7-GAL4 and in GAL4 lines, which exclusively affect sleep structure, were found to contribute to fragmentation of sleep during both day and night. Thus, multiple subtypes of ring neurons distinctively control sleep amount and/or structure. The unique highly interconnected structure of the EB suggests a local-network model worth future investigation; understanding EB subtype interactions may provide insight how sleep circuits in general are structured.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT How multiple brain regions, with many cell types, can coherently regulate sleep remains unclear, but identification of cell type-specific roles can generate opportunities for understanding the principles of integration and cooperation. The ellipsoid body (EB) of the fly brain exhibits a high level of connectivity and functional heterogeneity yet is able to tune multiple behaviors in real-time, including sleep. Leveraging the powerful genetic tools available in Drosophila and recent progress in the characterization of the morphology and connectivity of EB ring neurons, we identify several EB subtypes specifically associated with distinct aspects of sleep. Our findings will aid in revealing the rules of coding and integration in the brain.

Keywords: central complex, Drosophila melanogaster, ellipsoid body, ring neurons, sleep, sleep structure

Introduction

Sleep plays critical roles in many physiological functions. Sleep regulation in the brain is a complex process modulated at the molecular, cellular, circuit, and network levels (John et al., 2016; Scammell et al., 2017; Bringmann, 2018; Herice and Sakata, 2019; D. Liu and Dan, 2019). Previous studies in Drosophila melanogaster have revealed multiple cell types and neural circuits that participate in the regulation of sleep amount, structure, and homeostasis.

The ellipsoid body (EB) contributes to regulation of multiple behaviors, including spatial orientation, navigation, arousal, and sleep (Bausenwein et al., 1994; Lebestky et al., 2009; Ofstad et al., 2011; Seelig and Jayaraman, 2015; Fisher et al., 2019; Kim et al., 2019; Kottler et al., 2019). As one of the central structures on the midline of the fly brain, the EB receives direct input from, and sends output to, many brain regions. This high level of connectivity positions the EB to be a center for integration of multiple information streams, including visual, motor, mechanosensory, and circadian input, allowing it to functionally tune complex behaviors (Franconville et al., 2018).

The organization within the EB also exhibits complexity. With recent progress on morphology and connectivity of the EB, 22 distinct subtypes of ring neurons have been identified (Hulse et al., 2021). Each subtype of ring neuron typically contains a dendritic arborization lateral to the EB, then projects a single axon into the concentric laminated structure within the EB neuropil. The projections from each subtype of ring neuron form distinct layers within the neuropil, terminating in different rings at specific depths along the anterior-posterior axis where they interconnect (Hanesch et al., 1989; Young and Armstrong, 2010; Lin et al., 2013). These connections, between neurons of the same type, provide each ring neuron's strongest inputs (Isaacman-Beck et al., 2020; Hulse et al., 2021) and suggest a structural basis for local communication and synergism for sleep regulation.

Despite the growing understanding of EB connectivity, specific roles for each subtype of ring neuron in sleep are limited. One subtype of R5 neuron (initially referred to as R2) has been shown to drive a persistent sleep on secession of thermoactivation, suggesting a role in sleep drive and homeostasis (Donlea et al., 2014; S. Liu et al., 2016; Pimentel et al., 2016). Another study showed that single R5 neurons get synchronized by circadian input and the power of slow-wave oscillations in R5 neurons has been associated with increased sleep drive (Raccuglia et al., 2019). 5HT7-GAL4+ EB neurons, which consist of several subtypes including R3d, R3p, and R4d and are modulated by serotonergic signaling, can regulate sleep architecture (C. Liu et al., 2019). Despite these important findings, the scope of ring neuron involvement in the regulation of sleep is not clear.

In the present study, we take an unbiased approach, screening 34 drivers that label different combinations of subtypes of ring neurons by thermoactivation using the warmth-sensitive cation channel dTrpA1 (Hamada et al., 2008). Most drivers label multiple ring neurons, and activation of many drivers resulted in significant changes in sleep amount and/or sleep structure. The complexity of the tools and phenotypes necessitated developing computational approaches for assessing the importance of each subtype. Using P(wake) and P(doze) analysis with a mixed Gaussian model, five clusters of drivers were found to regulate sleep depth and pressure during the day and/or at night, respectively. Furthermore, a GLM analysis based on the GAL4 expression pattern and the sleep behavior on 24 h activation suggests several types of ring neuron contribute to sleep regulation consistent with and extending the findings from the Gaussian model. Finally, using genetic suppression of intersected population strategy, we identified a subpopulation of neurons which is sufficient to fragment sleep during both day and night. Although how the ring neurons cooperate to coherently modulate sleep is not yet clear, the identification of roles for specific cell types provides an important piece of the puzzle.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Unless specified, flies were reared on standard cornmeal food (each 1 L H2O: 70 g cornmeal, 50 g sucrose, 10 g soybean powder, 20 g yeast powder, 6 g agar, and 3 g methyl 4-hydroxybenzoate) at 23°C with 60% relative humidity and under a regimen of 12 h light/12 h dark. Flies were allowed to freely mate after eclosion, and mated females aged 2-5 d were used for all experiments. GAL4 lines: R12B01 (RRID:BDSC_48487), R15B07 (RRID:BDSC_48678), R28D01 (RRID:BDSC_47342), R28E01 (RRID:BDSC_49457), R38B06 (RRID:BDSC_49986), R38G08 (RRID:BDSC_50020), R38H02 (RRID:BDSC_47352), R41A08 (RRID:BDSC_50108), R41F05-GAL4 (RRID:BDSC_50133), R47F07 (RRID:BDSC_50320), R48B10 (RRID:BDSC_50352), R49E12 (RRID:BDSC_38693), R53F11 (RRID:BDSC_50443), R53G11 (RRID:BDSC_69747), R54B05 (RRID:BDSC_69148), R56C09 (RRID:BDSC_39145), R64H04 (RRID:BDSC_39323), R70B04 (RRID:BDSC_39513), R70B05 (RRID:BDSC_47721), R73A06 (RRID:BDSC_39805), R73B05 (RRID:BDSC_48312), R81F01 (RRID:BDSC_40120), R84H09 (RRID:BDSC_47803), Aphc507 (RRID:BDSC_30840), C232 (RRID:BDSC_30828), and R44D11-LexA (RRID:BDSC_41264), UAS-dTrpA1 (RRID:BDSC_26263), UAS-mCD8::GFP (RRID:BDSC_5136), UAS-mCD8::RFP, LexAop2-mCD8::GFP (RRID:BDSC_32229), and LexAop-Gal80 (RRID:BDSC_32213) were ordered from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center. GAL4 lines: VT012446, VT026841, VT042577, VT042759, VT045108, VT057257, VT038828, VT040539, and VT059775 were ordered from Vienna Drosophila Resource Center originally, but unfortunately not available anymore. 5HT7-GAL4 was provided by Charles Nicols' laboratory. Feb170-GAL4 was generated by Günter Korge's laboratory (Siegmund and Korge, 2001). The WT line wCS was crossed with GAL4 and UAS parental lines as genetic controls. Experimental groups were from the F1 generation of crosses of GAL4 lines to UAS-dTrpA1.

Experimental design for sleep assays and calculation of sleep changes

F1 generation of flies were all maintained on standard food at 23°C. Two- to 5-day-old mated F1 female flies were individually placed into a 65 mm × 5 mm glass tube containing food (2% agar and 5% sucrose). After loading to the DAM2 system (Drosophila Activity Monitor) (Trikinetics; https://www.trikinetics.com/) at 21°C in 12 h:12 h light/dark cycles, flies were entrained for 2-3 d. Then 1 d baseline sleep, 1 d neural activation sleep, as well as 1 d recovery sleep were recorded at 21°C, 30°C, and 21°C, respectively. Total sleep, the number of sleep episodes, and maximum episode length were analyzed for light and dark periods (LP and DP) separately, using MATLAB (RRID:SCR_001622) program (SCAMP2019v2) scripts.

To overview the effects on activation of GAL4+ neurons, all genotypes were arranged in a descending order according to the changes of total sleep during the LP. Sleep changes were calculated by subtracting baseline day sleep of each genotype from its activation day. Since using TRPA1 to activate neurons requires an elevation of ambient temperature (above 25°C), and temperature has been shown to effect sleep (Parisky et al., 2016; Jin et al., 2021; Alpert et al., 2022), it is critical to compare with control groups that have undergone the same temperature shift. With genetic control groups and a subtraction to the baseline day, the temperature effect can be removed and sleep changes because of activation of the neurons can be quantified. For genotypes with significant changes in sleep and/or sleep structure, 3 days' sleep profiles of sleep time in 30 min were plotted. Sleep changes of the recovery day were also calculated. The significant difference was marked when the experimental group is different compared with both genetic controls.

Immunohistochemistry

Brains of adult flies were dissected in 10 mm ice-cold PBS and fixed for 20 min in PBS with 4% PFA at room temperature. Brains were then washed 3 times for 5 min each in PBT (PBS with 0.5% Triton X-100). For GFP and RFP immunostaining, brains were incubated with primary antibodies (1:200, chicken anti-GFP, Abcam, catalog #ab13970, RRID:AB_300798; 1:200, mouse anti-GFP, Roche, catalog #11814460001, RRID:AB_390913; 1:1000, rabbit anti-GFP, Invitrogen, catalog #A-11122, RRID:AB_221569; 1:200, rabbit anti-DsRed, Takara, catalog #632496, RRID:AB_10013483) in 10% NGS in PBT at 4°C for two nights. After 3 times washes for 5 min each with PBT at room temperature, brains were incubated with secondary antibody at 4°C overnight. Second antibodies (488 goat anti-mouse, Invitrogen, catalog #A-11001, RRID:AB_2534069; 488 goat anti-chicken, Invitrogen, catalog #A-11039, RRID:AB_142924; 488 goat anti-rabbit, Invitrogen, catalog #A-11008, RRID:AB_143165; 568 goat anti-rabbit, Fisher Scientific, catalog #A-11011, RRID:AB_143157) were all used in a ratio of 1:200. Samples were then washed 3 times for 5 min each in PBT at room temperature, and mounted on microscope slide in Vectashield mounting medium (Vector Laboratories catalog #H-1000, RRID:AB_2336789). Finally, samples were imaged with Leica TCS SP5/LSM900 confocal microscope (RRID:SCR_002140) and analyzed using the open source of FIJI (ImageJ) software (RRID:SCR_002285).

Probability analysis

The probability of transitioning from a sleep to an awake state (P(wake)), and from a wake state to a sleep state (P(doze)) was used power law distributions analysis as previously described (Wiggin et al., 2020). P(wake) and P(doze) were calculated identically, with calculation of 1 min bin of inactivity and activity reversed. The MATLAB scripts for analysis of P(wake)/P(doze) can be accessed in GitHub at https://github.com/Griffith-Lab/Fly_Sleep_Probability.

Mixed Gaussian model clustering

To figure out different effects of EB drivers on both sleep pressure and depth, we divided all significant subtypes of EB ring neurons into groups with similar distributions of δ P(Wake) and δ P(Doze), using mixed Gaussian model clustering. The clustering analysis was conducted using the scripts of fitgmdist and cluster in MATLAB. Given the small sample size of neuron subtypes (14 and 13 for daytime and nighttime, respectively), the number of cluster k was set to 3, 4, or 5 for both daytime and nighttime. We calculated the silhouette coefficients for each k value using the script of silhouette in MATLAB and chose the final k value whose silhouette coefficient was the closest to one (Lecompte et al., 1986). The size of ellipse for each cluster was decided by the corresponding σ values of its Gaussian mixture distribution.

GLM

To evaluate the effect of a specific anatomic subtype of ring neurons on sleep, the GLM (Generalized linear models) was used to estimate the weights and the corresponding statistical significance of all subtypes for each sleep parameter. The GLM analysis was conducted using the script of glmfit in MATLAB (The MathWorks) to predict each sleep parameter under the combination of all subtypes of neurons. The input variable was defined as 1 or 0 for each subtype of ring neurons (R1, R2, R3d, R3m, R3a, R3p, R3w, R4m, R4d, R5, and R6) when labeled or not labeled by each driver, respectively. And the corresponding output variable was the mean change rate of each sleep parameter of the same driver on the activation to its baseline level (output variable value = (activation – baseline)/baseline). We chose the default parameters for the script of glmfit. According to the weight calculation for each subtype (see Table 6), a positive value represents positive relationship, and a negative value represents negative relationship between the subtype and the sleep parameter, respectively, when the corresponding p value < 0.05.

Table 6.

Statistical table of the weight of the effect of subclasses of ring neurons on the sleep using a GLMa

| Total sleep |

No. of episodes |

Maximum episode length |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LP |

DP |

LP |

DP |

LP |

DP |

|||||||

| Subtype | Weight | p | Weight | p | Weight | p | Weight | p | Weight | p | Weight | p |

| R1 | −66.963 | 0.806 | 3.71 | 0.789 | −78.081 | 0.218 | −289.982 | 0.025* | −40.711 | 0.918 | 39.093 | 0.058 |

| R2 | −4.43 | 0.986 | 20.206 | 0.117 | −53.171 | 0.351 | −287.956 | 0.015* | 10.987 | 0.976 | 37.288 | 0.047* |

| R3a | 243.881 | 0.394 | −19.084 | 0.192 | 0.156 | 0.998 | 100.72 | 0.43 | 239.529 | 0.562 | −35.538 | 0.095 |

| R3d | −290.368 | 0.202 | 3.727 | 0.742 | 72.222 | 0.166 | −99.637 | 0.323 | −335.803 | 0.306 | −4.78 | 0.769 |

| R3m | 207.085 | 0.45 | 11.389 | 0.413 | −110.33 | 0.086 | 97.25 | 0.428 | 490.865 | 0.222 | 27.874 | 0.168 |

| R3p | 424.718 | 0.038* | −4.8 | 0.628 | 12.879 | 0.772 | −24.945 | 0.775 | 747.409 | 0.014* | −7.29 | 0.608 |

| R3w | −235.362 | 0.422 | 10.664 | 0.472 | −77.07 | 0.253 | −118.224 | 0.367 | −244.843 | 0.563 | 33.605 | 0.122 |

| R4d | −60.809 | 0.768 | −5.332 | 0.61 | −23.994 | 0.611 | −104.199 | 0.264 | −192.1 | 0.522 | 7.413 | 0.621 |

| R4m | 63.512 | 0.793 | −39.476 | 0.003* | −3.416 | 0.951 | 97.465 | 0.371 | 100.607 | 0.774 | −45.005 | 0.016* |

| R5 | −67.36 | 0.751 | 11.467 | 0.292 | −49.769 | 0.31 | −168.218 | 0.086 | −140.881 | 0.648 | 31.922 | 0.048* |

| R6 | 999.282 | 0.069 | −7.214 | 0.788 | 81.007 | 0.505 | 103.387 | 0.663 | 196.977 | 0.798 | −8.583 | 0.823 |

aThe generalized linear model (GLM) analysis was conducted using the script of glmfit in MATLAB with the default parameters setting for total sleep, number of episodes, and maximum episode length. A positive value represents a positive relationship, and a negative value represents a negative relationship between the subtype of ring neurons and the sleep parameter, respectively.

*p < 0.05.

Statistical analysis

Power analysis was conducted using the script of sampsizepwr in MATLAB (The MathWorks) to calculate the power for the sample size in this study. The power analysis was based on the sleep parameters in drivers with significant differences from both control groups presented in the main figures. We selected the mean and SD of control groups under the null hypothesis, and the mean value of experimental groups under the alternative hypothesis during the calculation of power values. Based on current sample size, >80% of the powers of significances of sleep parameters were >0.9 (see Tables 2 and 7).

Table 2.

| Total sleep | Experiment vs GAL4 Control |

Experiment vs UAS Control |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30°C |

21°C |

30°C |

21°C |

|||||

| Drivers | LP | DP | LP | DP | LP | DP | LP | DP |

| c232 | 1 | 0.167 | 0.377 | 0.639 | 1 | 0.563 | 0.533 | 0.907 |

| Feb170 | 1 | 1 | 0.946 | 0.209 | 1 | 1 | 0.996 | 0.19 |

| R48B10 | 0.151 | 0.53 | 0.934 | 0.077 | 1 | 0.998 | 0.975 | 0.999 |

| R53F11 | 1 | 0.052 | 0.999 | 0.858 | 0.108 | 0.996 | 0.85 | 0.928 |

| No. of episodes | Experiment vs GAL4 Control |

Experiment vs UAS Control |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30°C |

21°C |

30°C |

21°C |

|||||

| Drivers | LP | DP | LP | DP | LP | DP | LP | DP |

| c232 | 0.057 | 0.09 | 0.497 | 0.268 | 0.102 | 0.347 | 0.561 | 0.186 |

| Feb170 | 0.929 | 0.99 | 0.234 | 0.083 | 0.819 | 0.06 | 0.989 | 0.86 |

| R48B10 | 1 | 0.977 | 0.985 | 0.286 | 1 | 0.948 | 0.521 | 0.287 |

| R53F11 | 0.816 | 1 | 0.948 | 0.149 | 0.705 | 0.992 | 0.323 | 0.078 |

| Maximum episode length | Experiment vs GAL4 Control |

Experiment vs UAS Control |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30°C |

21°C |

30°C |

21°C |

|||||

| Drivers | LP | DP | LP | DP | LP | DP | LP | DP |

| c232 | 0.999 | 0.182 | 0.075 | 0.05 | 0.975 | 0.46 | 0.159 | 0.057 |

| Feb170 | 1 | 0.795 | 0.053 | 0.05 | 0.993 | 0.859 | 0.673 | 0.121 |

| R48B10 | 0.814 | 0.051 | 0.244 | 0.061 | 1 | 0.21 | 0.502 | 0.086 |

| R53F11 | 0.815 | 0.188 | 0.275 | 0.219 | 0.413 | 0.091 | 0.19 | 0.054 |

aFour GAL4 drivers were included in the analysis: c232, Feb170, R48B10, and R53F11. The experimental group was compared with either GAL4 control group or UAS-dTrpA1 control group for both activation day and recovery day. Total sleep, number of episodes, and maximum episode length for LP and DP were analyzed separately. Power analysis was conducted using the script of sampsizepwr in MATLAB.

Table 7.

| Total sleep | Experiment vs GAL4 Control |

Experiment vs UAS Control |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30°C |

21°C |

30°C |

21°C |

|||||

| Drivers | LP | DP | LP | DP | LP | DP | LP | DP |

| R28E01 | 1 | 0.511 | 0.999 | 0.28 | 1 | 0.313 | 0.9 | 0.951 |

| R70B05 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0.667 | 1 | 1 | 0.994 | 0.985 |

| No. of episodes | Experiment vs GAL4 Control |

Experiment vs UAS Control |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30°C |

21°C |

30°C |

21°C |

|||||

| Drivers | LP | DP | LP | DP | LP | DP | LP | DP |

| R28E01 | 0.116 | 0.101 | 0.198 | 0.233 | 0.425 | 0.074 | 0.214 | 0.121 |

| R70B05 | 0.992 | 0.888 | 1 | 0.994 | 0.47 | 0.878 | 1 | 0.997 |

| Maximum episode length | Experiment vs GAL4 Control |

Experiment vs UAS Control |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 30°C |

21°C |

30°C |

21°C |

|||||

| Drivers | LP | DP | LP | DP | LP | DP | LP | DP |

| R28E01 | 1 | 0.07 | 0.425 | 0.222 | 0.995 | 0.354 | 0.659 | 0.161 |

| R70B05 | 0.947 | 0.652 | 0.981 | 0.873 | 1 | 0.983 | 1 | 1 |

aTwo GAL4 drivers were included in the analysis: R28E01 and R70B05. The experimental group was compared with either GAL4 control group or UAS-dTrpA1 control group for both activation day and recovery day. Total sleep, number of episodes, and maximum episode length for LP and DP were analyzed separately. Power analysis was conducted using the script of sampsizepwr in MATLAB.

Data were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 (RRID:SCR_002798). Group means were compared using one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni's multiple comparison test when data were normally distributed, or Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparison test was used when data failed passing normality test (see Tables 1, 3, 4, 8, and 9). All experiments were performed at least 2 replicates, and data presented in the figures were chosen from one representative replicate. To uniform the data presentation, all figures were prepared as mean ± SEM. To visualize all groups in the same figure clearer, error bars were not shown.

Table 1.

| △ Total sleep | LP (Fig. 1B) |

DP (Fig. 1G) |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonparametric/parametric test |

Post hoc comparisons |

Nonparametric/parametric test |

Post hoc comparisons |

|||||||||||||

| Driver | Test | DFn, DFd | F | p | n1 | n2 | Mean difference | p | Test | F | p | Mean difference | p | |||

| R47F07 | ANOVA | 2,92 | 118 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 24 | 39 | 350.6 | <0.0001 | **** | ANOVA | 46.59 | <0.0001 | −152.8 | <0.0001 | **** |

| 1 vs 3 | 24 | 32 | 257.9 | <0.0001 | **** | −249.2 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| R28E01 | K-W | 3,95 | 54.91 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 31 | 51.12 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 10.74 | 0.0046 | −15.22 | 0.0569 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 32 | 30.41 | <0.0001 | **** | 7.094 | 0.6067 | NS | ||||||||

| C232 | K-W | 3,91 | 31.94 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 30 | 31 | 36.11 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 10.32 | 0.0057 | −3.126 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 30 | 30 | 29.27 | <0.0001 | **** | 17.13 | 0.024 | * | ||||||||

| R70B04 | K-W | 3,94 | 43.46 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 30 | 32 | 43.7 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 8.177 | 0.0168 | 6.665 | 0.6727 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 30 | 32 | 11.9 | 0.2195 | NS | 19.43 | 0.0101 | * | ||||||||

| R53F11 | K-W | 3,95 | 51.75 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 32 | 40.65 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 23.45 | <0.0001 | 1.31 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 32 | −4.4 | >0.9999 | NS | 29.62 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| R56C09 | ANOVA | 2,51 | 5.698 | 0.0058 | 1 vs 2 | 22 | 11 | 125.5 | 0.0077 | ** | ANOVA | 0.579 | 0.5642 | −44.95 | 0.5146 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 22 | 21 | 89.39 | 0.0232 | * | −27.91 | 0.6812 | NS | ||||||||

| R54B05 | K-W | 3,89 | 22.79 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 26 | 31 | 19.65 | 0.0085 | ** | K-W | 12.29 | 0.0021 | −24.07 | 0.0009 | *** |

| 1 vs 3 | 26 | 32 | −11.12 | 0.2059 | NS | −12.41 | 0.1378 | NS | ||||||||

| R38B06 | K-W | 3,86 | 34.64 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 29 | 29 | 37.19 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 2.427 | 0.2972 | −8.966 | 0.3431 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 29 | 28 | 9.566 | 0.2964 | NS | −8.772 | 0.3697 | NS | ||||||||

| Aphc507 | K-W | 3,77 | 13.32 | 0.0013 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 28 | 21.04 | 0.0009 | *** | K-W | 21.59 | <0.0001 | −24.18 | 0.0001 | *** |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 21 | 4.952 | 0.8863 | NS | −25.18 | 0.0002 | *** | ||||||||

| R49E12 | ANOVA | 2,93 | 26.93 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 32 | 99.88 | 0.0003 | *** | ANOVA | 3.407 | 0.0373 | −47.66 | 0.0236 | * |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 32 | −86.66 | 0.0019 | ** | −33.16 | 0.1413 | NS | ||||||||

| R81F01 | K-W | 3,96 | 16.46 | 0.0003 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 32 | 10.72 | 0.2475 | NS | K-W | 18.51 | <0.0001 | −25.95 | 0.0004 | *** |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 32 | −17.28 | 0.0262 | * | −0.01563 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| R53G11 | K-W | 3,96 | 11.82 | 0.0027 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 32 | 23.38 | 0.0016 | ** | K-W | 19.26 | <0.0001 | −20.84 | 0.0055 | ** |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 32 | 7.188 | 0.604 | NS | 8.938 | 0.3987 | NS | ||||||||

| VT026841 | ANOVA | 2122 | 30.52 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 31 | 105.9 | <0.0001 | **** | ANOVA | 3.524 | 0.0325 | 37.39 | 0.1971 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 63 | −39.68 | 0.0634 | NS | 54.29 | 0.0167 | * | ||||||||

| VT059775 | ANOVA | 2114 | 20.89 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 26 | 103.2 | 0.0003 | *** | ANOVA | 16.31 | <0.0001 | 85.44 | 0.01 | * |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 63 | −43.83 | 0.0888 | NS | 142.6 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| R73B05 | ANOVA | 2,51 | 3.395 | 0.0413 | 1 vs 2 | 17 | 16 | 72.13 | 0.1285 | NS | ANOVA | 2.099 | 0.133 | −87.99 | 0.0842 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 17 | 21 | −23.49 | 0.7478 | NS | −35.22 | 0.5896 | NS | ||||||||

| R38H02 | K-W | 3,86 | 0.235 | 0.889 | 1 vs 2 | 27 | 31 | 0.6565 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 1.185 | 0.5529 | −5.4 | 0.8227 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 27 | 28 | −2.376 | >0.9999 | NS | −6.99 | 0.5986 | NS | ||||||||

| VT040539 | ANOVA | 2121 | 30.93 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 29 | 32 | 87.69 | 0.0001 | *** | ANOVA | 2.882 | 0.0599 | −15.65 | 0.7011 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 29 | 63 | −53.56 | 0.0093 | ** | 28.5 | 0.2546 | NS | ||||||||

| R64H04 | ANOVA | 2,55 | 3.678 | 0.0317 | 1 vs 2 | 15 | 22 | 48.58 | 0.2599 | NS | ANOVA | 4.723 | 0.0128 | −113.7 | 0.0111 | * |

| 1 vs 3 | 15 | 21 | −35.03 | 0.4794 | NS | −104.1 | 0.0222 | * | ||||||||

| R48B10 | K-W | 3,95 | 24.6 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 32 | −3.269 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 19.05 | <0.0001 | 15.12 | 0.0591 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 32 | −31.21 | <0.0001 | **** | 30.32 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| R28D01 | K-W | 3,90 | 32.67 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 30 | 31.6 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 4.767 | 0.0922 | 0.05104 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 28 | −3.527 | >0.9999 | NS | −12.96 | 0.1104 | NS | ||||||||

| R41A08 | K-W | 3,88 | 6.072 | 0.048 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 28 | 8.607 | 0.3858 | NS | K-W | 4.948 | 0.0842 | −13.51 | 0.0819 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 28 | −8.214 | 0.428 | NS | −1.172 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| VT042759 | ANOVA | 2118 | 21.26 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 27 | 31 | 80.45 | 0.0069 | ** | ANOVA | 0.487 | 0.6156 | 2.115 | 0.996 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 27 | 63 | −65.97 | 0.0117 | * | 21.63 | 0.6054 | NS | ||||||||

| VT045108 | ANOVA | 2120 | 38.59 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 32 | 107.2 | <0.0001 | **** | ANOVA | 0.528 | 0.591 | 12.84 | 0.805 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 63 | −67.04 | 0.0031 | ** | −8.04 | 0.8938 | NS | ||||||||

| R12B01 | K-W | 3,78 | 12.95 | 0.0015 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 25 | 15.31 | 0.0227 | * | K-W | 6.563 | 0.0376 | −14.36 | 0.0352 | * |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 21 | −8.075 | 0.4089 | NS | −0.7254 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| VT057257 | ANOVA | 2123 | 19.46 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 32 | 47.47 | 0.0708 | NS | ANOVA | 23.47 | <0.0001 | 98.3 | 0.0004 | *** |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 63 | −70.94 | 0.001 | ** | 161.2 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| VT038828 | K-W | 3,62 | 5.49 | 0.0643 | 1 vs 2 | 26 | 15 | 5.356 | 0.7197 | NS | K-W | 4.588 | 0.1008 | −9.454 | 0.2121 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 26 | 21 | −8.482 | 0.2182 | NS | 3.346 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| R38G08 | K-W | 3,83 | 10.76 | 0.0046 | 1 vs 2 | 26 | 29 | 8.57 | 0.376 | NS | K-W | 6.406 | 0.0406 | −15.45 | 0.0353 | * |

| 1 vs 3 | 26 | 28 | −12.3 | 0.1221 | NS | −13.08 | 0.0928 | NS | ||||||||

| R15B07 | K-W | 3,85 | 14.76 | 0.0006 | 1 vs 2 | 29 | 28 | 11.53 | 0.1559 | NS | K-W | 5.134 | 0.0768 | −3.488 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 29 | 28 | −13.78 | 0.0702 | NS | −14.26 | 0.0585 | NS | ||||||||

| VT042577 | K-W | 3120 | 58.2 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 27 | 31 | 9.205 | 0.6295 | NS | K-W | 12.25 | 0.0022 | −19.2 | 0.0719 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 27 | 62 | −43.13 | <0.0001 | **** | −28.07 | 0.0009 | *** | ||||||||

| R84H09 | K-W | 3,90 | 18.2 | 0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 30 | −12.04 | 0.1397 | NS | K-W | 17.35 | 0.0002 | −23.64 | 0.0007 | *** |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 28 | −28.79 | <0.0001 | **** | −24.29 | 0.0007 | *** | ||||||||

| VT012446 | ANOVA | 2117 | 75.08 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 29 | 30.76 | 0.341 | NS | ANOVA | 7.622 | 0.0008 | −48.21 | 0.1101 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 63 | −191 | <0.0001 | **** | −85.36 | 0.0004 | *** | ||||||||

| R73A06 | K-W | 3120 | 75.21 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 25 | 32 | 8.963 | 0.6687 | NS | K-W | 1.036 | 0.5958 | −3.546 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 25 | 63 | −49.77 | <0.0001 | **** | −7.989 | 0.6624 | NS | ||||||||

| Feb170 | K-W | 3,80 | 18.24 | 0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 24 | −22.63 | 0.0009 | *** | K-W | 51.75 | <0.0001 | −35.42 | <0.0001 | **** |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 28 | −23.77 | 0.0003 | *** | −41.73 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| R70B05 | K-W | 3,92 | 26.7 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 32 | −26.62 | 0.0002 | *** | K-W | 53.05 | <0.0001 | −47.15 | <0.0001 | **** |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 32 | −34.32 | <0.0001 | **** | −40.02 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| △ No. of episodes | LP (Fig. 1C) |

DP (Fig. 1H) |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonparametric/parametric test |

Post hoc comparisons |

Nonparametric/parametric test |

Post hoc comparisons |

|||||||||||||

| Driver | Test | DFn, DFd | F | p | n1 | n2 | Mean difference | p | Test | F | p | Mean difference | p | |||

| R47F07 | K-W | 3,95 | 7.568 | 0.0227 | 1 vs 2 | 24 | 39 | 19.64 | 0.0119 | * | K-W | 18.4 | 0.0001 | 29.67 | <0.0001 | **** |

| 1 vs 3 | 24 | 32 | 12.74 | 0.1729 | NS | 24.76 | 0.0017 | ** | ||||||||

| R28E01 | K-W | 3,95 | 2.654 | 0.2653 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 31 | −4.62 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 0.739 | 0.6911 | 1.878 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 32 | −11.16 | 0.2099 | NS | −3.953 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| C232 | K-W | 3,91 | 0.678 | 0.7125 | 1 vs 2 | 30 | 31 | 3.171 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 2.079 | 0.3536 | 2.794 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 30 | 30 | −2.367 | >0.9999 | NS | 9.55 | 0.3222 | NS | ||||||||

| R70B04 | K-W | 3,94 | 35.74 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 30 | 32 | −32.64 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 0.779 | 0.6776 | 3.006 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 30 | 32 | −38.64 | <0.0001 | **** | 6.1 | 0.7555 | NS | ||||||||

| R53F11 | K-W | 3,95 | 9.895 | 0.0071 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 32 | 20.93 | 0.0051 | ** | K-W | 9.558 | 0.0084 | 18.14 | 0.0178 | * |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 32 | 15.93 | 0.0432 | * | 19.06 | 0.012 | * | ||||||||

| R56C09 | K-W | 3,54 | 2.258 | 0.3233 | 1 vs 2 | 22 | 11 | 5.568 | 0.6736 | NS | K-W | 6.358 | 0.0416 | −4.023 | 0.9765 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 22 | 21 | −3.209 | >0.9999 | NS | 9.295 | 0.1051 | NS | ||||||||

| R54B05 | K-W | 3,89 | 26.26 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 26 | 31 | 18.94 | 0.0114 | * | K-W | 4.334 | 0.1145 | 10.62 | 0.2432 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 26 | 32 | 34.87 | <0.0001 | **** | −2.155 | >0.9999 | ns | ||||||||

| R38B06 | ANOVA | 2,83 | 2.258 | 0.1109 | 1 vs 2 | 29 | 29 | 4.103 | 0.0839 | NS | ANOVA | 3.078 | 0.0514 | 0.7586 | 0.9196 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 29 | 28 | 0.899 | 0.87 | NS | 5.187 | 0.0442 | * | ||||||||

| Aphc507 | K-W | 3,77 | 24.3 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 28 | 27.54 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 7.434 | 0.0243 | 7.679 | 0.3972 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 21 | 23.79 | 0.0005 | *** | 17.59 | 0.0128 | * | ||||||||

| R49E12 | K-W | 3,96 | 1.664 | 0.4351 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 32 | 8.453 | 0.4482 | NS | K-W | 6.715 | 0.0348 | 13.72 | 0.0972 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 32 | 6.828 | 0.6522 | NS | 16.98 | 0.0292 | * | ||||||||

| R81F01 | K-W | 3,96 | 3.284 | 0.1936 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 32 | 12.59 | 0.14 | NS | K-W | 9.191 | 0.0101 | 16.44 | 0.0362 | * |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 32 | 6.484 | 0.7018 | NS | −3.219 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| R53G11 | K-W | 3,96 | 22.95 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 32 | 32.3 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 44.77 | <0.0001 | 44.39 | <0.0001 | **** |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 32 | 23.25 | 0.0017 | ** | 34.36 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| VT026841 | K-W | 3125 | 8.142 | 0.0171 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 31 | 16.61 | 0.1409 | NS | K-W | 22.53 | <0.0001 | −36.65 | 0.0001 | *** |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 63 | −5.966 | 0.9039 | NS | −1.65 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| VT059775 | K-W | 3117 | 12.24 | 0.0022 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 26 | 31.59 | 0.0012 | ** | K-W | 0.976 | 0.614 | −8.577 | 0.7052 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 63 | 19.7 | 0.0209 | * | −2.032 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| R73B05 | K-W | 3,54 | 2.625 | 0.2692 | 1 vs 2 | 17 | 16 | 0.5919 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 5.997 | 0.0499 | −6.77 | 0.4324 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 17 | 21 | −6.804 | 0.369 | NS | 5.99 | 0.4854 | NS | ||||||||

| R38H02 | K-W | 3,86 | 9.21 | 0.01 | 1 vs 2 | 27 | 31 | 19.9 | 0.0048 | ** | K-W | 5.21 | 0.0739 | −8.433 | 0.398 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 27 | 28 | 10.16 | 0.2613 | NS | 6.322 | 0.6947 | NS | ||||||||

| VT040539 | K-W | 3124 | 24.96 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 29 | 32 | 19.98 | 0.0599 | NS | K-W | 3.677 | 0.159 | −3.832 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 29 | 63 | −18.53 | 0.0428 | * | 10.06 | 0.4235 | NS | ||||||||

| R64H04 | ANOVA | 2,55 | 1.367 | 0.2633 | 1 vs 2 | 15 | 22 | 2.088 | 0.6098 | NS | ANOVA | 4.35 | 0.0176 | −8.248 | 0.0391 | * |

| 1 vs 3 | 15 | 21 | −1.724 | 0.713 | NS | 0.1238 | 0.999 | NS | ||||||||

| R48B10 | K-W | 3,95 | 46.85 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 32 | 40.93 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 7.392 | 0.0248 | 17.16 | 0.0267 | * |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 32 | 41.57 | <0.0001 | **** | 15.45 | 0.0517 | NS | ||||||||

| R28D01 | K-W | 3,90 | 3.352 | 0.1871 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 30 | −3.553 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 9.549 | 0.0084 | −5.297 | 0.8486 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 28 | −12.11 | 0.1453 | NS | 15.17 | 0.0493 | * | ||||||||

| R41A08 | ANOVA | 2,85 | 5.785 | 0.0044 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 28 | −0.1295 | 0.9951 | NS | ANOVA | 1.715 | 0.1861 | 2.393 | 0.3985 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 28 | −4.772 | 0.006 | ** | 3.679 | 0.1318 | NS | ||||||||

| VT042759 | K-W | 3121 | 21.94 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 27 | 31 | 20.81 | 0.0481 | * | K-W | 8.514 | 0.0142 | −25.67 | 0.0108 | * |

| 1 vs 3 | 27 | 63 | −15.04 | 0.1239 | NS | −8.14 | 0.6248 | NS | ||||||||

| VT045108 | K-W | 3123 | 8.938 | 0.0115 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 32 | 9.393 | 0.6156 | NS | K-W | 3.369 | 0.1856 | −15.18 | 0.1992 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 63 | −13.03 | 0.2138 | NS | −2.889 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| R12B01 | K-W | 3,78 | 3.412 | 0.1816 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 25 | 9.155 | 0.2589 | NS | K-W | 12.76 | 0.0017 | 6.425 | 0.5756 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 21 | −2.077 | >0.9999 | NS | 22.53 | 0.0008 | *** | ||||||||

| VT057257 | K-W | 3126 | 22.64 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 32 | 41.51 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 15.57 | 0.0004 | −12.24 | 0.3661 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 63 | 11.37 | 0.3106 | NS | 17.93 | 0.0502 | NS | ||||||||

| VT038828 | ANOVA | 2,59 | 1.74 | 0.1845 | 1 vs 2 | 26 | 15 | 4.382 | 0.2177 | NS | ANOVA | 5.011 | 0.0098 | 9.069 | 0.0096 | ** |

| 1 vs 3 | 26 | 21 | −0.7418 | 0.9423 | NS | 6.46 | 0.0475 | * | ||||||||

| R38G08 | ANOVA | 2,80 | 1.988 | 0.1436 | 1 vs 2 | 26 | 29 | −2.434 | 0.3897 | NS | ANOVA | 2.548 | 0.0846 | 0.3448 | 0.9817 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 26 | 28 | −4.121 | 0.0904 | NS | 4.429 | 0.0875 | NS | ||||||||

| R15B07 | K-W | 3,85 | 10.93 | 0.0042 | 1 vs 2 | 29 | 28 | 17.1 | 0.0176 | * | K-W | 14.44 | 0.0007 | 6.181 | 0.6876 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 29 | 28 | −3.076 | >0.9999 | NS | 23.97 | 0.0005 | *** | ||||||||

| VT042577 | K-W | 3120 | 19.98 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 27 | 31 | 16.35 | 0.1474 | NS | K-W | 14.08 | 0.0009 | −31.35 | 0.0012 | ** |

| 1 vs 3 | 27 | 62 | −17.24 | 0.0625 | NS | −7.047 | 0.7584 | NS | ||||||||

| R84H09 | K-W | 3,90 | 20.78 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 30 | 29.04 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 11.58 | 0.0031 | −1.535 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 28 | 6.507 | 0.6706 | NS | 19.42 | 0.008 | ** | ||||||||

| VT012446 | K-W | 3120 | 18.28 | 0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 29 | 38.62 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 21.18 | <0.0001 | −29.3 | 0.0029 | ** |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 63 | 14.5 | 0.1319 | NS | 6.21 | 0.8629 | NS | ||||||||

| R73A06 | K-W | 3120 | 9.067 | 0.0107 | 1 vs 2 | 25 | 32 | 3.286 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 4.374 | 0.1123 | −8.631 | 0.7041 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 25 | 63 | −17.14 | 0.0736 | NS | 7.051 | 0.7813 | NS | ||||||||

| Feb170 | ANOVA | 2,77 | 3.437 | 0.0372 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 24 | 6.054 | 0.0387 | * | ANOVA | 11.1 | <0.0001 | −10.18 | 0.0001 | *** |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 28 | 5.25 | 0.0666 | NS | −0.75 | 0.9254 | NS | ||||||||

| R70B05 | K-W | 3,92 | 8.747 | 0.0126 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 32 | 18.15 | 0.0171 | * | K-W | 2.965 | 0.2271 | 9.442 | 0.3428 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 32 | 1.772 | >0.9999 | NS | 11.15 | 0.2129 | NS | ||||||||

| △ Maximum episode length | LP (Fig. 1D) |

DP (Fig. 1I) |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonparametric/parametric test |

Post hoc comparisons |

Nonparametric/parametric test |

Post hoc comparisons |

|||||||||||||

| Driver | Test | DFn, DFd | F | p | n1 | n2 | Mean difference | p | Test | F | p | Mean difference | p | |||

| R47F07 | K-W | 3,95 | 22.94 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 24 | 39 | 33.99 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 8.847 | 0.012 | −19.7 | 0.0117 | * |

| 1 vs 3 | 24 | 32 | 17.46 | 0.038 | * | −18.91 | 0.0221 | * | ||||||||

| R28E01 | K-W | 3,95 | 37.95 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 31 | 42.57 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 4.146 | 0.1258 | −1.289 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 32 | 17.2 | 0.0251 | * | 11.5 | 0.1904 | NS | ||||||||

| C232 | K-W | 3,91 | 13.18 | 0.0014 | 1 vs 2 | 30 | 31 | 21.43 | 0.0031 | ** | K-W | 2.027 | 0.3629 | 5.958 | 0.7569 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 30 | 30 | 21.33 | 0.0035 | ** | 9.617 | 0.317 | NS | ||||||||

| R70B04 | K-W | 3,94 | 21.76 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 30 | 32 | 32.33 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 3.214 | 0.2005 | 12.38 | 0.1483 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 30 | 32 | 16.28 | 0.0376 | * | 5.442 | 0.865 | NS | ||||||||

| R53F11 | K-W | 3,95 | 18.06 | 0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 32 | 11.71 | 0.184 | NS | K-W | 0.858 | 0.6513 | −6.345 | 0.7222 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 32 | −17.4 | 0.0245 | * | −4.142 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| R56C09 | K-W | 3,54 | 3.97 | 0.1374 | 1 vs 2 | 22 | 11 | 6.636 | 0.5066 | NS | K-W | 1.94 | 0.379 | 0.04545 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 22 | 21 | 9.381 | 0.1013 | NS | −6.102 | 0.4072 | NS | ||||||||

| R54B05 | K-W | 3,89 | 25.17 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 26 | 31 | −12.84 | 0.1231 | NS | K-W | 6.834 | 0.0328 | −8.372 | 0.446 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 26 | 32 | −33.55 | <0.0001 | **** | 8.645 | 0.41 | NS | ||||||||

| R38B06 | K-W | 3,86 | 5.417 | 0.0667 | 1 vs 2 | 29 | 29 | 15.22 | 0.0405 | * | K-W | 2.062 | 0.3566 | −1.224 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 29 | 28 | 6.685 | 0.6245 | NS | −8.794 | 0.3675 | NS | ||||||||

| Aphc507 | K-W | 3,77 | 8.111 | 0.0173 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 28 | −4 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 15.37 | 0.0005 | −17.68 | 0.0062 | ** |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 21 | −17.85 | 0.0114 | * | −23.57 | 0.0005 | *** | ||||||||

| R49E12 | K-W | 3,96 | 21.38 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 32 | 13.92 | 0.0912 | NS | K-W | 0.052 | 0.9745 | −1.578 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 32 | −18.19 | 0.018 | * | −0.6719 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| R81F01 | K-W | 3,96 | 15.93 | 0.0003 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 32 | 0.1719 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 8.752 | 0.0126 | −10.81 | 0.241 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 32 | −23.98 | 0.0011 | ** | 9.781 | 0.3203 | NS | ||||||||

| R53G11 | K-W | 3,96 | 14.58 | 0.0007 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 32 | −26.19 | 0.0003 | *** | K-W | 16.56 | 0.0003 | −27.7 | 0.0001 | *** |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 32 | −17.08 | 0.0284 | * | −19.03 | 0.0126 | * | ||||||||

| VT026841 | K-W | 3125 | 11.13 | 0.0038 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 31 | 13.68 | 0.2743 | NS | K-W | 12.01 | 0.0025 | 31.89 | 0.0011 | ** |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 63 | −12.52 | 0.2302 | NS | 16.09 | 0.0859 | NS | ||||||||

| VT059775 | K-W | 3117 | 18.86 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 26 | −9.118 | 0.6472 | NS | K-W | 12.9 | 0.0016 | 18.48 | 0.0909 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 63 | −30.99 | 0.0001 | *** | 27.66 | 0.0007 | *** | ||||||||

| R73B05 | K-W | 3,54 | 2.125 | 0.3456 | 1 vs 2 | 17 | 16 | 7.397 | 0.3541 | NS | K-W | 3.092 | 0.2131 | −6.57 | 0.4611 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 17 | 21 | 1.171 | >0.9999 | NS | −8.835 | 0.1704 | NS | ||||||||

| R38H02 | K-W | 3,86 | 4.33 | 0.1147 | 1 vs 2 | 27 | 31 | −13.12 | 0.092 | NS | K-W | 8.219 | 0.0164 | 6.246 | 0.684 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 27 | 28 | −3.622 | >0.9999 | NS | −12.2 | 0.1399 | NS | ||||||||

| VT040539 | K-W | 3124 | 1.149 | 0.5629 | 1 vs 2 | 29 | 32 | −3.626 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 3.704 | 0.1569 | 11.61 | 0.4152 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 29 | 63 | −8.339 | 0.6022 | NS | 15.48 | 0.1098 | NS | ||||||||

| R64H04 | K-W | 3,58 | 2.046 | 0.3595 | 1 vs 2 | 15 | 22 | −7.117 | 0.4163 | NS | K-W | 5.632 | 0.0598 | 9.37 | 0.195 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 15 | 21 | −7.367 | 0.3938 | NS | −2.267 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| R48B10 | K-W | 3,95 | 43.17 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 32 | −21.71 | 0.0036 | ** | K-W | 2.044 | 0.3598 | 1.821 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 32 | −45.61 | <0.0001 | **** | 9.336 | 0.358 | NS | ||||||||

| R28D01 | K-W | 3,90 | 8.714 | 0.0128 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 30 | 19.28 | 0.0074 | ** | K-W | 7.384 | 0.0249 | 7.048 | 0.5768 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 28 | 6.165 | 0.7236 | NS | −11.47 | 0.1796 | NS | ||||||||

| R41A08 | K-W | 3,88 | 7.201 | 0.0273 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 28 | 10.37 | 0.2333 | NS | K-W | 1.163 | 0.5592 | −3.431 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 28 | 17.57 | 0.0157 | * | −7.127 | 0.562 | NS | ||||||||

| VT042759 | K-W | 3121 | 1.694 | 0.4288 | 1 vs 2 | 27 | 31 | 3.568 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 2.454 | 0.2932 | 14.21 | 0.2475 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 27 | 63 | −6.024 | 0.9105 | NS | 5.741 | 0.9534 | NS | ||||||||

| VT045108 | K-W | 3123 | 11.3 | 0.0035 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 32 | 8.79 | 0.6813 | NS | K-W | 0.231 | 0.8908 | −0.9107 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 63 | −16.04 | 0.0952 | NS | −3.512 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| R12B01 | K-W | 3,78 | 2.066 | 0.3559 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 25 | −4.789 | 0.857 | NS | K-W | 6.516 | 0.0385 | −8.618 | 0.3084 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 21 | −9.04 | 0.3109 | NS | −16.03 | 0.0235 | * | ||||||||

| VT057257 | K-W | 3126 | 10.88 | 0.0043 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 32 | −21.74 | 0.0364 | * | K-W | 3.119 | 0.2102 | 12.92 | 0.3204 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 63 | −26.02 | 0.0023 | ** | 13.53 | 0.1824 | NS | ||||||||

| VT038828 | K-W | 3,62 | 1.464 | 0.4808 | 1 vs 2 | 26 | 15 | −3.295 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 4.462 | 0.1074 | −12.33 | 0.0701 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 26 | 21 | −6.39 | 0.4546 | NS | −5.159 | 0.6594 | NS | ||||||||

| R38G08 | K-W | 3,83 | 1.082 | 0.5821 | 1 vs 2 | 26 | 29 | 6.631 | 0.6168 | NS | K-W | 2.933 | 0.2307 | −6.452 | 0.6432 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 26 | 28 | 2.31 | >0.9999 | NS | −11.22 | 0.175 | NS | ||||||||

| R15B07 | K-W | 3,85 | 8.564 | 0.0138 | 1 vs 2 | 29 | 28 | −18.1 | 0.0113 | * | K-W | 7.204 | 0.0273 | −9.044 | 0.3332 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 29 | 28 | −14.3 | 0.0576 | NS | −17.54 | 0.0146 | * | ||||||||

| VT042577 | K-W | 3120 | 13.2 | 0.0014 | 1 vs 2 | 27 | 31 | −3.256 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 7.474 | 0.0238 | 21.56 | 0.0371 | * |

| 1 vs 3 | 27 | 62 | −24.72 | 0.0041 | ** | 2.697 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| R84H09 | K-W | 3,90 | 8.832 | 0.0121 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 30 | −17.27 | 0.0186 | * | K-W | 5.947 | 0.0511 | −0.7583 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 28 | −16.91 | 0.0248 | * | −14.86 | 0.0559 | NS | ||||||||

| VT012446 | K-W | 3120 | 45.35 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 29 | −7.68 | 0.8093 | NS | K-W | 4.805 | 0.0905 | 12.13 | 0.3761 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 63 | −46.4 | <0.0001 | **** | −4.972 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| R73A06 | K-W | 3120 | 45.9 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 25 | 32 | −4.716 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 1.651 | 0.438 | 11.93 | 0.3978 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 25 | 63 | −45.6 | <0.0001 | **** | 6.513 | 0.8566 | NS | ||||||||

| Feb170 | K-W | 3,80 | 26.9 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 24 | −29.38 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 18.19 | 0.0001 | −16.12 | 0.0253 | * |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 28 | −27.16 | <0.0001 | **** | −26.29 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| R70B05 | K-W | 3,92 | 26.38 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 32 | −31.9 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 12.54 | 0.0019 | −15.88 | 0.043 | * |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 32 | −30.17 | <0.0001 | **** | −24.21 | 0.0009 | *** | ||||||||

| △ P(doze) | LP (Fig. 1E) |

DP (Fig. 1J) |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonparametric/parametric test |

Post hoc comparisons |

Nonparametric/parametric test |

Post hoc comparisons |

|||||||||||||

| Driver | Test | DFn, DFd | F | p | n1 | n2 | Mean difference | p | Test | F | p | Mean difference | p | |||

| R47F07 | K-W | 3,95 | 45.66 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 31 | 46.4 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 23.39 | <0.0001 | 25.36 | 0.0005 | *** |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 32 | 16.66 | 0.0313 | * | 31.47 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| R28E01 | K-W | 3,96 | 15.34 | 0.0005 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 32 | 26.91 | 0.0002 | *** | K-W | 5.817 | 0.0545 | 10.84 | 0.2389 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 32 | 9.563 | 0.3394 | NS | 16.53 | 0.0352 | * | ||||||||

| C232 | K-W | 3,92 | 12.34 | 0.0021 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 31 | 17.03 | 0.0241 | * | K-W | 8.184 | 0.0167 | −2.323 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 30 | 23.11 | 0.0015 | ** | 15.71 | 0.0433 | * | ||||||||

| R70B04 | K-W | 3,90 | 21.41 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 27 | 31 | 30.78 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 13.43 | 0.0012 | 22.41 | 0.0022 | ** |

| 1 vs 3 | 27 | 32 | 9.712 | 0.3097 | NS | 21.63 | 0.0031 | ** | ||||||||

| R53F11 | K-W | 3,94 | 62.65 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 30 | 32 | 54.01 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 38.71 | <0.0001 | 34.1 | <0.0001 | **** |

| 1 vs 3 | 30 | 32 | 36.17 | <0.0001 | **** | 40.22 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| R56C09 | K-W | 3,55 | 7.995 | 0.0184 | 1 vs 2 | 23 | 11 | 15.14 | 0.0199 | * | K-W | 1.245 | 0.5367 | −4.585 | 0.87 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 23 | 21 | 10.06 | 0.075 | NS | 2.06 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| R54B05 | K-W | 3,87 | 16.31 | 0.0003 | 1 vs 2 | 24 | 31 | 27.73 | 0.0001 | *** | K-W | 1.889 | 0.3889 | 2.621 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 24 | 32 | 15.73 | 0.0422 | * | −5.938 | 0.768 | NS | ||||||||

| R38B06 | K-W | 3,85 | 20.07 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 29 | 29 | 26.55 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 4.584 | 0.1011 | 9.897 | 0.2536 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 29 | 27 | 2.854 | >0.9999 | NS | 13.58 | 0.0793 | NS | ||||||||

| Aphc507 | K-W | 3,78 | 48.18 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 29 | 35.39 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 40.34 | <0.0001 | 31.56 | <0.0001 | **** |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 21 | 39.21 | <0.0001 | **** | 36.68 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| R49E12 | K-W | 3,94 | 23.26 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 31 | 24.03 | 0.001 | ** | K-W | 0.85 | 0.6536 | −6.226 | 0.7378 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 32 | −7.883 | 0.503 | NS | −4.345 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| R81F01 | ANOVA | 2,93 | 12.57 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 32 | 0.08838 | <0.0001 | **** | ANOVA | 0.488 | 0.6154 | 0.03071 | 0.6904 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 32 | 0.02067 | 0.5304 | NS | 0.02308 | 0.9553 | NS | ||||||||

| R53G11 | ANOVA | 2,91 | 140.8 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 31 | 0.4689 | <0.0001 | **** | ANOVA | 83.57 | <0.0001 | 0.4356 | <0.0001 | **** |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 32 | 0.4239 | <0.0001 | **** | 0.4201 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| VT026841 | K-W | 3125 | 35.75 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 31 | 13.48 | 0.2857 | NS | K-W | 6.354 | 0.0417 | −14.97 | 0.2077 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 63 | −30.83 | 0.0002 | *** | 4.997 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| VT059775 | ANOVA | 2110 | 37.94 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 25 | 25 | 0.2231 | <0.0001 | **** | ANOVA | 7.847 | 0.0007 | −0.00487 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 25 | 63 | 0.22 | <0.0001 | **** | 0.08162 | 0.0052 | ** | ||||||||

| R73B05 | K-W | 3,54 | 0.229 | 0.8917 | 1 vs 2 | 17 | 16 | −1.706 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 4.328 | 0.1148 | −3.813 | 0.9732 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 17 | 21 | 0.7703 | >0.9999 | NS | 6.762 | 0.3754 | NS | ||||||||

| R38H02 | K-W | 3,85 | 26.52 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 27 | 31 | 32.8 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 8.025 | 0.0181 | −15.33 | 0.0365 | * |

| 1 vs 3 | 27 | 27 | 11.67 | 0.1649 | NS | 0.8148 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| VT040539 | K-W | 3124 | 6.565 | 0.0375 | 1 vs 2 | 29 | 32 | 14.85 | 0.214 | NS | K-W | 4.511 | 0.1048 | 12.19 | 0.3718 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 29 | 63 | −5.067 | >0.9999 | NS | 17.12 | 0.0675 | NS | ||||||||

| R64H04 | K-W | 3,59 | 4.236 | 0.1203 | 1 vs 2 | 15 | 23 | 11.35 | 0.093 | NS | K-W | 8.076 | 0.0176 | −15.03 | 0.0168 | * |

| 1 vs 3 | 15 | 21 | 4.429 | 0.8913 | NS | −4.143 | 0.9511 | NS | ||||||||

| R48B10 | K-W | 3,93 | 33.55 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 30 | 31 | 38.6 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 36.21 | <0.0001 | 35.53 | <0.0001 | **** |

| 1 vs 3 | 30 | 32 | 28.67 | <0.0001 | **** | 36.49 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| R28D01 | K-W | 3,88 | 11.65 | 0.0029 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 30 | 10.33 | 0.2287 | NS | K-W | 3.733 | 0.1546 | −0.2624 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 27 | −12.79 | 0.1143 | NS | 11.28 | 0.1871 | NS | ||||||||

| R41A08 | K-W | 3,86 | 15.5 | 0.0004 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 28 | 15.05 | 0.0415 | * | K-W | 3.114 | 0.2108 | −4.499 | 0.9791 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 27 | −11.35 | 0.1686 | NS | 7.286 | 0.5354 | NS | ||||||||

| VT042759 | K-W | 3119 | 25.96 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 26 | 30 | 29.2 | 0.0032 | ** | K-W | 2.782 | 0.2489 | −10.97 | 0.4702 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 26 | 63 | −9.69 | 0.4564 | NS | −13.3 | 0.1963 | NS | ||||||||

| VT045108 | K-W | 3123 | 9.84 | 0.0073 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 32 | 16.79 | 0.1377 | NS | K-W | 6.609 | 0.0367 | −20.93 | 0.0466 | * |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 63 | −7.48 | 0.7112 | NS | −3.385 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| R12B01 | K-W | 3,77 | 12.13 | 0.0023 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 25 | 18.97 | 0.0032 | ** | K-W | 2.735 | 0.2547 | −5 | 0.8115 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 21 | 16.92 | 0.0149 | * | 5.952 | 0.693 | NS | ||||||||

| VT057257 | K-W | 3126 | 17.41 | 0.0002 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 32 | 35.45 | 0.0002 | *** | K-W | 25.56 | <0.0001 | −8.33 | 0.7308 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 63 | 7.576 | 0.6886 | NS | 28.13 | 0.0009 | *** | ||||||||

| VT038828 | K-W | 3,62 | 5.289 | 0.071 | 1 vs 2 | 19 | 22 | 12.44 | 0.0553 | NS | K-W | 0.959 | 0.619 | 5.335 | 0.6902 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 19 | 21 | 9.882 | 0.1673 | NS | 4.123 | 0.9409 | NS | ||||||||

| R38G08 | K-W | 3,81 | 4.512 | 0.1047 | 1 vs 2 | 25 | 29 | 3.23 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 1.653 | 0.4377 | −7.363 | 0.503 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 25 | 27 | −9.71 | 0.2741 | NS | −0.7319 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| R15B07 | K-W | 3,84 | 12.6 | 0.0018 | 1 vs 2 | 29 | 28 | −0.351 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 1.506 | 0.4709 | −7.621 | 0.4767 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 29 | 27 | −20.39 | 0.0035 | ** | −1.806 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| VT042577 | K-W | 3123 | 25.99 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 32 | 21.61 | 0.0384 | * | K-W | 4.099 | 0.1288 | −9.924 | 0.5641 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 63 | −17.6 | 0.0595 | NS | 5.738 | 0.9571 | NS | ||||||||

| R84H09 | K-W | 3,88 | 39.79 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 30 | 38.04 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 1.079 | 0.5831 | 6.716 | 0.6093 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 27 | 4.256 | >0.9999 | NS | 2.368 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| VT012446 | K-W | 3120 | 21.99 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 29 | 43.22 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 18.98 | <0.0001 | −17.35 | 0.1195 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 63 | 21.6 | 0.0125 | * | 16.15 | 0.0819 | NS | ||||||||

| R73A06 | K-W | 3120 | 1.409 | 0.4943 | 1 vs 2 | 25 | 32 | −6.146 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 1.733 | 0.4204 | −10.97 | 0.4748 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 25 | 63 | −9.716 | 0.4747 | NS | −2.466 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| Feb170 | K-W | 3,81 | 21.58 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 29 | 25 | 28.27 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 11.39 | 0.0034 | −10.35 | 0.2139 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 29 | 27 | 21.31 | 0.0014 | ** | 11.65 | 0.128 | NS | ||||||||

| R70B05 | ANOVA | 2,86 | 23.94 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 27 | 30 | 0.2709 | <0.0001 | **** | ANOVA | 69.04 | <0.0001 | 0.4665 | <0.0001 | **** |

| 1 vs 3 | 27 | 32 | 0.1498 | 0.0004 | *** | 0.4365 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| △ P(wake) | LP (Fig. 1F) |

DP (Fig. 1K) |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonparametric/parametric test |

Post hoc comparisons |

Nonparametric/parametric test |

Post hoc comparisons |

|||||||||||||

| Driver | Test | DFn, DFd | F | p | n1 | n2 | Mean difference | p | Test | F | p | Mean difference | p | |||

| R47F07 | K-W | 3,95 | 20.67 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 31 | −22.98 | 0.0019 | ** | K-W | 33.22 | <0.0001 | 21.38 | 0.0042 | ** |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 32 | −29.97 | <0.0001 | **** | 39.69 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| R28E01 | K-W | 3,96 | 21.46 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 32 | −31.44 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 9.154 | 0.0103 | 20.5 | 0.0065 | ** |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 32 | −9.438 | 0.3507 | NS | 6.031 | 0.7729 | NS | ||||||||

| C232 | K-W | 3,92 | 5.439 | 0.0659 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 31 | −10.77 | 0.2243 | NS | K-W | 0.371 | 0.8309 | −0.1935 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 30 | −15.53 | 0.0464 | * | −3.708 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| R70B04 | K-W | 3,90 | 24.58 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 27 | 31 | −32.25 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 1.492 | 0.4741 | 7.388 | 0.5653 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 27 | 32 | −7.976 | 0.4854 | NS | 0.603 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| R53F11 | K-W | 3,94 | 31.47 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 30 | 32 | −18.44 | 0.0156 | * | K-W | 5.14 | 0.0765 | 15.13 | 0.0582 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 30 | 32 | 19.81 | 0.0085 | ** | 4.16 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| R56C09 | K-W | 3,55 | 0.134 | 0.9352 | 1 vs 2 | 23 | 11 | 1.277 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 1.029 | 0.5978 | 5.387 | 0.718 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 23 | 21 | −0.8965 | >0.9999 | NS | 3.669 | 0.896 | NS | ||||||||

| R54B05 | K-W | 3,87 | 3.497 | 0.174 | 1 vs 2 | 24 | 31 | −11.23 | 0.2039 | NS | K-W | 16.74 | 0.0002 | 27.92 | <0.0001 | **** |

| 1 vs 3 | 24 | 32 | −1.24 | >0.9999 | NS | 13.17 | 0.1071 | NS | ||||||||

| R38B06 | K-W | 3,85 | 22.1 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 29 | 29 | −29.45 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 3.352 | 0.1871 | 5.931 | 0.7203 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 29 | 27 | −7.777 | 0.4775 | NS | 12.08 | 0.1343 | NS | ||||||||

| Aphc507 | K-W | 3,78 | 7.019 | 0.0299 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 29 | −7.612 | 0.4097 | NS | K-W | 35.78 | <0.0001 | 32.48 | <0.0001 | **** |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 21 | 9.583 | 0.2858 | NS | 31.29 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| R49E12 | K-W | 3,94 | 13.47 | 0.0012 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 31 | −12.16 | 0.1585 | NS | K-W | 10.84 | 0.0044 | 18.94 | 0.0126 | * |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 32 | 13.06 | 0.1149 | NS | 20.36 | 0.0061 | ** | ||||||||

| R81F01 | K-W | 3,96 | 11.28 | 0.0036 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 32 | 0.5 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 13.12 | 0.0014 | 22.13 | 0.003 | ** |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 32 | 20.5 | 0.0065 | ** | 0.5625 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| R53G11 | K-W | 3,94 | 10.85 | 0.0044 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 31 | 4.968 | 0.9468 | NS | K-W | 25.01 | <0.0001 | 34.29 | <0.0001 | **** |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 32 | 21.58 | 0.0034 | ** | 12.88 | 0.1219 | NS | ||||||||

| VT026841 | K-W | 3125 | 12.64 | 0.0018 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 31 | −27.65 | 0.0053 | ** | K-W | 1.709 | 0.4254 | −10.32 | 0.5239 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 63 | −1.502 | >0.9999 | NS | −0.809 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| VT059775 | K-W | 3113 | 29.41 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 25 | 25 | 7 | 0.9001 | NS | K-W | 2.853 | 0.2402 | −9.72 | 0.5885 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 25 | 63 | 36.83 | <0.0001 | **** | −13.07 | 0.1827 | NS | ||||||||

| R73B05 | K-W | 3,54 | 4.271 | 0.1182 | 1 vs 2 | 17 | 16 | −5.555 | 0.6214 | NS | K-W | 5.594 | 0.061 | 12.86 | 0.0379 | * |

| 1 vs 3 | 17 | 21 | 5.216 | 0.6191 | NS | 7.521 | 0.2857 | NS | ||||||||

| R38H02 | K-W | 3,85 | 2.746 | 0.2533 | 1 vs 2 | 27 | 31 | 9.661 | 0.274 | NS | K-W | 2.862 | 0.2391 | 0.5317 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 27 | 27 | 9.37 | 0.3261 | NS | 10 | 0.2731 | NS | ||||||||

| VT040539 | K-W | 3124 | 33.57 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 29 | 32 | −13.52 | 0.2846 | NS | K-W | 4.112 | 0.128 | 18.66 | 0.0858 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 29 | 63 | 29.09 | 0.0006 | *** | 10.51 | 0.3848 | NS | ||||||||

| R64H04 | K-W | 3,59 | 5.863 | 0.0533 | 1 vs 2 | 15 | 23 | −4.896 | 0.7808 | NS | K-W | 4.294 | 0.1169 | 10.76 | 0.1182 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 15 | 21 | 7.61 | 0.38 | NS | 10.5 | 0.1408 | NS | ||||||||

| R48B10 | K-W | 3,93 | 19.43 | 19.43 | 1 vs 2 | 30 | 31 | 16.61 | 0.0325 | * | K-W | 1.99 | 0.3698 | 2.994 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 30 | 32 | 30.21 | <0.0001 | **** | −6.388 | 0.7035 | NS | ||||||||

| R28D01 | K-W | 3,88 | 16.8 | 0.0002 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 30 | −20.47 | 0.0035 | ** | K-W | 5.059 | 0.0797 | 5.797 | 0.7513 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 27 | 5.559 | 0.8169 | NS | 15.06 | 0.0503 | NS | ||||||||

| R41A08 | K-W | 3,86 | 3.179 | 0.204 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 28 | 6.783 | 0.5948 | NS | K-W | 5.348 | 0.069 | 14.63 | 0.0492 | * |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 27 | 11.61 | 0.1545 | NS | 10.1 | 0.2486 | NS | ||||||||

| VT042759 | K-W | 3119 | 8.507 | 0.0142 | 1 vs 2 | 26 | 30 | −1.505 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 0.097 | 0.9526 | −1.413 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 26 | 63 | 17.64 | 0.0564 | NS | 0.9634 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| VT045108 | K-W | 3123 | 20.09 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 32 | −6.754 | 0.9282 | NS | K-W | 8.545 | 0.014 | 11.15 | 0.4535 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 63 | 24.84 | 0.0043 | ** | 23.06 | 0.0088 | ** | ||||||||

| R12B01 | K-W | 3,77 | 12.28 | 0.0022 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 25 | −3.947 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 2.253 | 0.3241 | 7.408 | 0.436 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 21 | 17.95 | 0.0091 | ** | −1.604 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| VT057257 | K-W | 3126 | 15.43 | 0.0004 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 32 | −2.342 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 12.62 | 0.0018 | −27.62 | 0.0054 | ** |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 63 | 24.32 | 0.0048 | ** | −26.39 | 0.002 | ** | ||||||||

| VT038828 | K-W | 3,62 | 3.449 | 0.1783 | 1 vs 2 | 19 | 22 | −1.543 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 3.602 | 0.1651 | 9.1 | 0.2145 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 19 | 21 | 8.065 | 0.316 | NS | 0.02256 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| R38G08 | K-W | 3,81 | 5.615 | 0.0604 | 1 vs 2 | 25 | 29 | −7.476 | 0.4886 | NS | K-W | 5.318 | 0.07 | 10.32 | 0.2157 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 25 | 27 | 7.43 | 0.5104 | NS | 14.71 | 0.0485 | * | ||||||||

| R15B07 | K-W | 3,84 | 5.756 | 0.0562 | 1 vs 2 | 29 | 28 | −5.112 | 0.8579 | NS | K-W | 9.158 | 0.0103 | 1.052 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 29 | 27 | 10.4 | 0.2219 | NS | 17.74 | 0.0131 | * | ||||||||

| VT042577 | K-W | 3123 | 23.35 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 32 | −7.221 | 0.8676 | NS | K-W | 31.86 | <0.0001 | 28.4 | 0.0042 | ** |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 63 | 26.82 | 0.0019 | ** | 45.57 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| R84H09 | K-W | 3,88 | 19.71 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 30 | 21.25 | 0.0023 | ** | K-W | 27.23 | <0.0001 | 28.34 | <0.0001 | **** |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 27 | 28.32 | <0.0001 | **** | 31.12 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| VT012446 | K-W | 3120 | 47.36 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 29 | 2.543 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 39.32 | <0.0001 | 27.13 | 0.0065 | ** |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 63 | 45.02 | <0.0001 | **** | 49.01 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| R73A06 | K-W | 3120 | 77.72 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 25 | 32 | −4.016 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 15.11 | 0.0005 | 10.21 | 0.5429 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 25 | 63 | 53.74 | <0.0001 | **** | 29.44 | 0.0007 | *** | ||||||||

| Feb170 | K-W | 3,81 | 21.73 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 29 | 25 | 26.48 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 52.79 | <0.0001 | 33.97 | <0.0001 | **** |

| 1 vs 3 | 29 | 27 | 24.31 | 0.0002 | *** | 43.34 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| R70B05 | K-W | 3,89 | 29.88 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 27 | 30 | 30.76 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 53.64 | <0.0001 | 45.1 | <0.0001 | **** |

| 1 vs 3 | 27 | 32 | 34 | <0.0001 | **** | 42.08 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

aChange in sleep parameters for total sleep, number of episodes, maximum episode length, P(doze), and P(wake) on the activation day (30°C) were analyzed for day (LP) and night (DP) separately. Datasets that had a normal distribution, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test was applied. For datasets that did not pass the normality test, Kruskal–Wallis (K-W) followed by Dunn's test was applied. Post hoc tests were applied between the experimental group (F1 generation of the cross of GAL4 lines to UAS-dTrpA1)(1) and the genetic control groups (F1 generation of the crosses of either GAL4 lines to wCS or UAS-dTrpA1 to wCS)(2 or 3).

*p < 0.05.

**p < 0.01.

***p < 0.001.

****p < 0.0001.

Table 3.

| LP |

DP |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Driver | Nonparametric/parametric test |

Post hoc comparisons |

Nonparametric/parametric test |

Post hoc comparisons |

||||||||||||

| D3-D1 21°C | Test | DFn, DFd | F | p | n1 | n2 | Mean difference | p | Test | F | p | Mean difference | p | |||

| C232 | ||||||||||||||||

| △ Total sleep | K-W | 3,91 | 4.103 | 0.1285 | 1 vs 2 | 30 | 31 | 8.725 | 0.3943 | NS | K-W | 16.77 | 0.0002 | −21.16 | 0.0035 | ** |

| 1 vs 3 | 30 | 30 | 13.63 | 0.0912 | NS | −26.32 | 0.0002 | *** | ||||||||

| △ No. of episodes | K-W | 3,91 | 4.451 | 0.108 | 1 vs 2 | 30 | 31 | 8.845 | 0.3803 | NS | K-W | 2.186 | 0.3352 | 9.984 | 0.2786 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 30 | 30 | 14.22 | 0.0735 | NS | 4.9 | 0.9435 | NS | ||||||||

| △ Maximum episode length | K-W | 3,91 | 1.39 | 0.4991 | 1 vs 2 | 30 | 31 | −2.339 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 0.326 | 0.8494 | −1.673 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 30 | 30 | 5.45 | 0.8483 | NS | 2.183 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| △ P(doze) | K-W | 3,92 | 28.85 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 31 | −30.23 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 4.809 | 0.0903 | −13.87 | 0.0817 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 30 | 2.694 | >0.9999 | NS | −2.237 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| △ P(wake) | K-W | 3,92 | 5.069 | 0.0793 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 31 | −13.42 | 0.0957 | NS | K-W | 10.1 | 0.0064 | 17.19 | 0.0225 | * |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 30 | −13.09 | 0.1112 | NS | 19.97 | 0.007 | ** | ||||||||

| Feb170 | ||||||||||||||||

| △ Total sleep | K-W | 3,80 | 27.64 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 24 | 15.15 | 0.0382 | * | K-W | 3.219 | 0.2 | −10.73 | 0.1939 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 28 | 32.63 | <0.0001 | **** | −8.661 | 0.3263 | NS | ||||||||

| △ No. of episodes | ANOVA | 2,77 | 9.999 | 0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 24 | 2.488 | 0.1756 | NS | ANOVA | 4.401 | 0.0155 | 1.405 | 0.7464 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 28 | 7.679 | <0.0001 | **** | 5.964 | 0.0108 | * | ||||||||

| △ Maximum episode length | K-W | 3,80 | 8.277 | 0.0159 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 24 | 0.6994 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 0.452 | 0.7979 | −0.7917 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 28 | 15.98 | 0.0201 | * | −3.964 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| △ P(doze) | K-W | 3,81 | 44.43 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 29 | 25 | 18.76 | 0.007 | ** | K-W | 18.67 | <0.0001 | 11.07 | 0.1695 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 29 | 27 | 41.91 | <0.0001 | **** | 27.1 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| △ P(wake) | K-W | 3,81 | 11.13 | 0.0038 | 1 vs 2 | 29 | 25 | 0.06207 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 10.96 | 0.0042 | 19.4 | 0.005 | ** |

| 1 vs 3 | 29 | 27 | −18.47 | 0.0067 | ** | 16.48 | 0.0176 | * | ||||||||

| R48B10 | ||||||||||||||||

| △ Total sleep | K-W | 3,95 | 17.59 | 0.0002 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 32 | 23.65 | 0.0013 | ** | K-W | 0.76 | 0.684 | −5.828 | 0.803 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 32 | 26.67 | 0.0002 | *** | −1.546 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| △ No. of episodes | K-W | 3,95 | 11.89 | 0.0026 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 32 | 23.91 | 0.0011 | ** | K-W | 4.2 | 0.1224 | 11.79 | 0.1781 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 32 | 12 | 0.167 | NS | 12.82 | 0.1289 | NS | ||||||||

| △ Maximum episode length | K-W | 3,95 | 2.567 | 0.2771 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 32 | 8.717 | 0.4192 | NS | K-W | 1.002 | 0.606 | −3.074 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 32 | 10.39 | 0.2696 | NS | −6.933 | 0.6365 | NS | ||||||||

| △ P(doze) | ANOVA | 2,90 | 3.153 | 0.0475 | 1 vs 2 | 30 | 31 | 0.02628 | 0.4415 | NS | ANOVA | 13.58 | <0.0001 | 0.1613 | 0.0003 | *** |

| 1 vs 3 | 30 | 32 | 0.05309 | 0.0277 | * | 0.2017 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| △ P(wake) | K-W | 3,93 | 8.553 | 0.0139 | 1 vs 2 | 30 | 31 | −16.77 | 0.0305 | * | K-W | 2.183 | 0.3357 | 10.15 | 0.2844 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 30 | 32 | −18.15 | 0.0163 | * | 6.156 | 0.7389 | NS | ||||||||

| R53F11 | ||||||||||||||||

| △ Total sleep | K-W | 3,95 | 15.56 | 0.0004 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 32 | 23.22 | 0.0017 | ** | K-W | 9.302 | 0.0096 | 20.46 | 0.0064 | ** |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 32 | 24.33 | 0.0009 | *** | 5.681 | 0.8266 | NS | ||||||||

| △ No. of episodes | K-W | 3,95 | 7.201 | 0.0273 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 32 | 18.6 | 0.0147 | * | K-W | 1.607 | 0.4479 | −7.84 | 0.5069 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 32 | 10.08 | 0.2921 | NS | −0.7308 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| △ Maximum episode length | K-W | 3,95 | 1.743 | 0.4183 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 32 | −8.788 | 0.4117 | NS | K-W | 2.279 | 0.3201 | 8.549 | 0.4369 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 32 | −6.726 | 0.6659 | NS | −0.8881 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| △ P(doze) | ANOVA | 2,95 | 1.461 | 0.2371 | 1 vs 2 | 30 | 34 | 0.01617 | 0.8543 | NS | K-W | 9.719 | 0.0078 | 9.725 | 0.3443 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 30 | 34 | 0.03458 | 0.183 | NS | 22.08 | 0.0039 | ** | ||||||||

| △ P(wake) | K-W | 3,98 | 9.365 | 0.0093 | 1 vs 2 | 30 | 34 | −19.12 | 0.0146 | * | K-W | 5.342 | 0.0692 | −15.8 | 0.0531 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 30 | 34 | −19.03 | 0.0151 | * | −4.475 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

aChange in sleep parameters, total sleep, number of episodes, maximum episode length, P(doze), and P(wake) on the recovery day (21°C) were analyzed for day (LP) and night (DP) separately. One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test or Kruskal–Wallis (K-W) followed by Dunn's test was applied based on distribution of the datasets.

*p < 0.05.

**p < 0.01.

***p < 0.001.

****p < 0.0001.

Table 4.

| LP |

DP |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Driver | Nonparametric/parametric test |

Post hoc comparisons |

Nonparametric/parametric test |

Post hoc comparisons |

||||||||||||

| D3-D1 21°C | Test | DFn, DFd | F | p | n1 | n2 | Mean difference | p | Test | F | p | Mean difference | p | |||

| R64H04 | ||||||||||||||||

| △ Total sleep | ANOVA | 2,55 | 5.451 | 0.0069 | 1 vs 2 | 15 | 22 | −121.1 | 0.0035 | ** | ANOVA | 2.027 | 0.1415 | −29.82 | 0.6373 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 15 | 21 | −85.58 | 0.0464 | * | −75.3 | 0.0959 | NS | ||||||||

| △ No. of episodes | ANOVA | 2,55 | 0.0772 | 0.9258 | 1 vs 2 | 15 | 22 | −0.5091 | 0.9676 | NS | ANOVA | 0.098 | 0.9072 | −1.006 | 0.9253 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 15 | 21 | −0.981 | 0.8884 | NS | −1.4 | 0.8643 | NS | ||||||||

| △ Maximum episode length | K-W | 3,58 | 8.367 | 0.0152 | 1 vs 2 | 15 | 22 | −16.35 | 0.0077 | ** | K-W | 2.913 | 0.2331 | −9.277 | 0.2017 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 15 | 21 | −9.386 | 0.2003 | NS | −7.681 | 0.3569 | NS | ||||||||

| △ P(doze) | ANOVA | 2,56 | 3.591 | 0.0341 | 1 vs 2 | 15 | 23 | −0.02696 | 0.7393 | NS | K-W | 1.256 | 0.2927 | −0.07932 | 0.2415 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 15 | 21 | 0.04529 | 0.2829 | NS | −0.05507 | 0.5749 | NS | ||||||||

| △ P(wake) | ANOVA | 2,56 | 5.536 | 0.0064 | 1 vs 2 | 15 | 23 | 0.1066 | 0.016 | * | K-W | 3.68 | 0.1588 | 0.5768 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 15 | 21 | 0.124 | 0.0054 | ** | 9.295 | 0.2188 | NS | ||||||||

| R47F07 | ||||||||||||||||

| △ Total sleep | ANOVA | 2,92 | 7.799 | 0.0007 | 1 vs 2 | 24 | 39 | −107.8 | 0.001 | ** | ANOVA | 12.99 | <0.0001 | −54.83 | 0.0075 | ** |

| 1 vs 3 | 24 | 32 | −25.5 | 0.6125 | NS | 30.61 | 0.1952 | NS | ||||||||

| △ No. of episodes | K-W | 3,95 | 9.574 | 0.0083 | 1 vs 2 | 24 | 39 | 12.56 | 0.1576 | NS | K-W | 2.283 | 0.3194 | −10.53 | 0.2796 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 24 | 32 | −7.448 | 0.633 | NS | −4.609 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| △ Maximum episode length | K-W | 3,95 | 13.04 | 0.0015 | 1 vs 2 | 24 | 39 | −20.25 | 0.0093 | ** | K-W | 0.042 | 0.9793 | −0.00641 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 24 | 32 | 0.8698 | >0.9999 | NS | −1.229 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| △ P(doze) | K-W | 3,95 | 3.265 | 0.1954 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 31 | 12.13 | 0.1615 | NS | K-W | 5.942 | 0.0513 | −5.134 | 0.9198 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 32 | 8.75 | 0.4085 | NS | 11.38 | 0.1977 | NS | ||||||||

| △ P(wake) | ANOVA | 2,92 | 2.319 | 0.1041 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 31 | 0.07036 | 0.1217 | NS | K-W | 9.721 | 0.0077 | 6.953 | 0.6339 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 32 | −0.00178 | 0.9983 | NS | −14.25 | 0.0774 | NS | ||||||||

| R84H09 | ||||||||||||||||

| △ Total sleep | K-W | 3,90 | 0.3417 | 0.8429 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 30 | −2.221 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 6.194 | 0.0452 | 10.71 | 0.2137 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 28 | 1.777 | >0.9999 | NS | −6.096 | 0.7344 | NS | ||||||||

| △ No. of episodes | K-W | 3,90 | 0.934 | 0.6269 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 30 | −0.725 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 1.779 | 0.4108 | 1.976 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 28 | −6.054 | 0.7396 | NS | 8.681 | 0.3972 | NS | ||||||||

| △ Maximum episode length | K-W | 3,90 | 1.147 | 0.5634 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 30 | −2.349 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 1.838 | 0.399 | 1.258 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 28 | 4.877 | 0.9412 | NS | −7.375 | 0.5506 | NS | ||||||||

| △ P(doze) | K-W | 3,88 | 8.562 | 0.0138 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 30 | 12.25 | 0.1223 | NS | K-W | 2.214 | 0.3305 | −1.055 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 27 | −7.252 | 0.5617 | NS | 8.217 | 0.4435 | NS | ||||||||

| △ P(wake) | K-W | 3,88 | 0.9652 | 0.6172 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 30 | 6.324 | 0.6676 | NS | K-W | 3.736 | 0.1545 | −9.147 | 0.3242 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 27 | 2.068 | >0.9999 | NS | 3.382 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

aChange in sleep parameters, total sleep, number of episodes, maximum episode length, P(doze), and P(wake) on the recovery day (21°C) were analyzed for day (LP) and night (DP) separately. One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test or Kruskal–Wallis (K-W) followed by Dunn's test was applied based on distribution of the datasets.

*p < 0.05.

**p < 0.01.

Table 8.

| LP |

DP |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Driver | Nonparametric/parametric test |

Post hoc comparisons |

Nonparametric/parametric test |

Post hoc comparisons |

||||||||||||

| D3-D1 21°C | Test | DFn, DFd | F | p | n1 | n2 | Mean difference | p | Test | F | p | Mean difference | p | |||

| R28E01 | ||||||||||||||||

| △ Total sleep | K-W | 3,95 | 22 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 31 | −31.06 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 4.966 | 0.0835 | 5.503 | 0.8565 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 32 | −23.77 | 0.0011 | ** | 15.17 | 0.0554 | NS | ||||||||

| △ Maximum episode length | K-W | 3,95 | 7.5 | 0.0235 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 31 | −15.71 | 0.0474 | * | K-W | 1.406 | 0.4951 | −7.219 | 0.5974 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 32 | −16.97 | 0.0276 | * | −6.969 | 0.6239 | NS | ||||||||

| △ P(doze) | K-W | 3,96 | 4.376 | 0.1121 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 32 | −7.656 | 0.5432 | NS | K-W | 8 | 0.0183 | 9.281 | 0.3653 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 32 | −14.56 | 0.073 | NS | 19.69 | 0.0094 | ** | ||||||||

| △ P(wake) | K-W | 3,96 | 12.76 | 0.0017 | 1 vs 2 | 32 | 32 | 22.16 | 0.0029 | ** | K-W | 2.335 | 0.3111 | −2.031 | >0.9999 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 32 | 32 | 20.88 | 0.0054 | ** | −10.06 | 0.297 | NS | ||||||||

| R70B05 | ||||||||||||||||

| △ Total sleep | K-W | 3,92 | 16.31 | 0.0003 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 32 | −26.52 | 0.0002 | *** | K-W | 13.3 | 0.0013 | −7.692 | 0.5311 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 32 | −21.48 | 0.0038 | ** | −24.4 | 0.0008 | *** | ||||||||

| △ Maximum episode length | K-W | 3,92 | 27.48 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 28 | 32 | −35.09 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 20.64 | <0.0001 | −23.01 | 0.0017 | ** |

| 1 vs 3 | 28 | 32 | −26.31 | 0.0003 | *** | −30.33 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| △ P(doze) | ANOVA | 2,86 | 14.35 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 27 | 30 | 0.1319 | <0.0001 | **** | ANOVA | 10.82 | <0.0001 | 0.2261 | <0.0001 | **** |

| 1 vs 3 | 27 | 32 | 0.1144 | <0.0001 | **** | 0.1582 | 0.0035 | ** | ||||||||

| △ P(wake) | K-W | 3,89 | 18.94 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 27 | 30 | 28.97 | <0.0001 | **** | K-W | 14.74 | 0.0006 | 15.24 | 0.0523 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 27 | 32 | 21.15 | 0.0035 | ** | 25.88 | 0.0003 | *** | ||||||||

aChange in sleep parameters, total sleep, number of episodes, maximum episode length, P(doze), and P(wake) on the recovery day (21°C) were analyzed for day (LP) and night (DP) separately. One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test or Kruskal–Wallis (K-W) followed by Dunn's test was applied based on distribution of the datasets.

*p < 0.05.

**p < 0.01.

***p < 0.001.

****p < 0.0001.

Table 9.

| LP |

DP |

|||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonparametric/parametric test |

Post hoc comparisons |

Nonparametric/parametric test |

Post hoc comparisons |

|||||||||||||

| D3-D1 21 °C | Test | DFn, DFd | F | p | n1 | n2 | Mean difference | p | Test | F | p | Mean difference | p | |||

| Figure 7C | ||||||||||||||||

| △ Total sleep | K-W | 3,93 | 2.44 | 0.2952 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 32 | 0.2535 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 4.394 | 0.1111 | −10.63 | 0.2363 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 30 | −9.22 | 0.3644 | NS | −13.76 | 0.0929 | NS | ||||||||

| △ No. of episodes | K-W | 3,93 | 0.7446 | 0.6892 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 32 | −1.765 | >0.9999 | NS | K-W | 7.075 | 0.0291 | 17.92 | 0.0167 | * |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 30 | −5.817 | 0.799 | NS | 7.035 | 0.6165 | NS | ||||||||

| △ Maximum episode length | K-W | 3,93 | 0.1451 | 0.93 | 1 vs 2 | 31 | 32 | −2.587 | >0.9999 | NS | ANOVA | 1.287 | 0.281 | −72.87 | 0.202 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 31 | 30 | −1.191 | >0.9999 | NS | −26.9 | 0.7888 | NS | ||||||||

| Figure 7E | ||||||||||||||||

| △ Total sleep | ANOVA | 2,93 | 0.5201 | 0.5962 | 1 vs 2 | 40 | 30 | 25.21 | 0.5593 | NS | K-W | 1.289 | 0.525 | 7.621 | 0.5146 | NS |

| 1 vs 3 | 40 | 26 | 0.2596 | >0.9999 | NS | 2.791 | >0.9999 | NS | ||||||||

| △ No. of episodes | K-W | 3,96 | 27.92 | <0.0001 | 1 vs 2 | 40 | 30 | 24.85 | 0.0004 | *** | ANOVA | 21.09 | <0.0001 | 11.26 | <0.0001 | **** |

| 1 vs 3 | 40 | 26 | 34.78 | <0.0001 | **** | 12.6 | <0.0001 | **** | ||||||||

| △ Maximum episode length | K-W | 3,96 | 1.574 | 0.4551 | 1 vs 2 | 40 | 30 | −5.592 | 0.8118 | NS | K-W | 20.92 | <0.0001 | −25.46 | 0.0003 | *** |

| 1 vs 3 | 40 | 26 | −8.41 | 0.4615 | NS | −27.34 | 0.0002 | *** | ||||||||

aChange in sleep parameters, total sleep, number of episodes, and maximum episode length on the activation day (30°C) were analyzed for LP and DP separately. One-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni test or Kruskal–Wallis (K-W) followed by Dunn's test was applied based on distribution of the datasets.

*p < 0.05.

***p < 0.001.

****p < 0.0001.

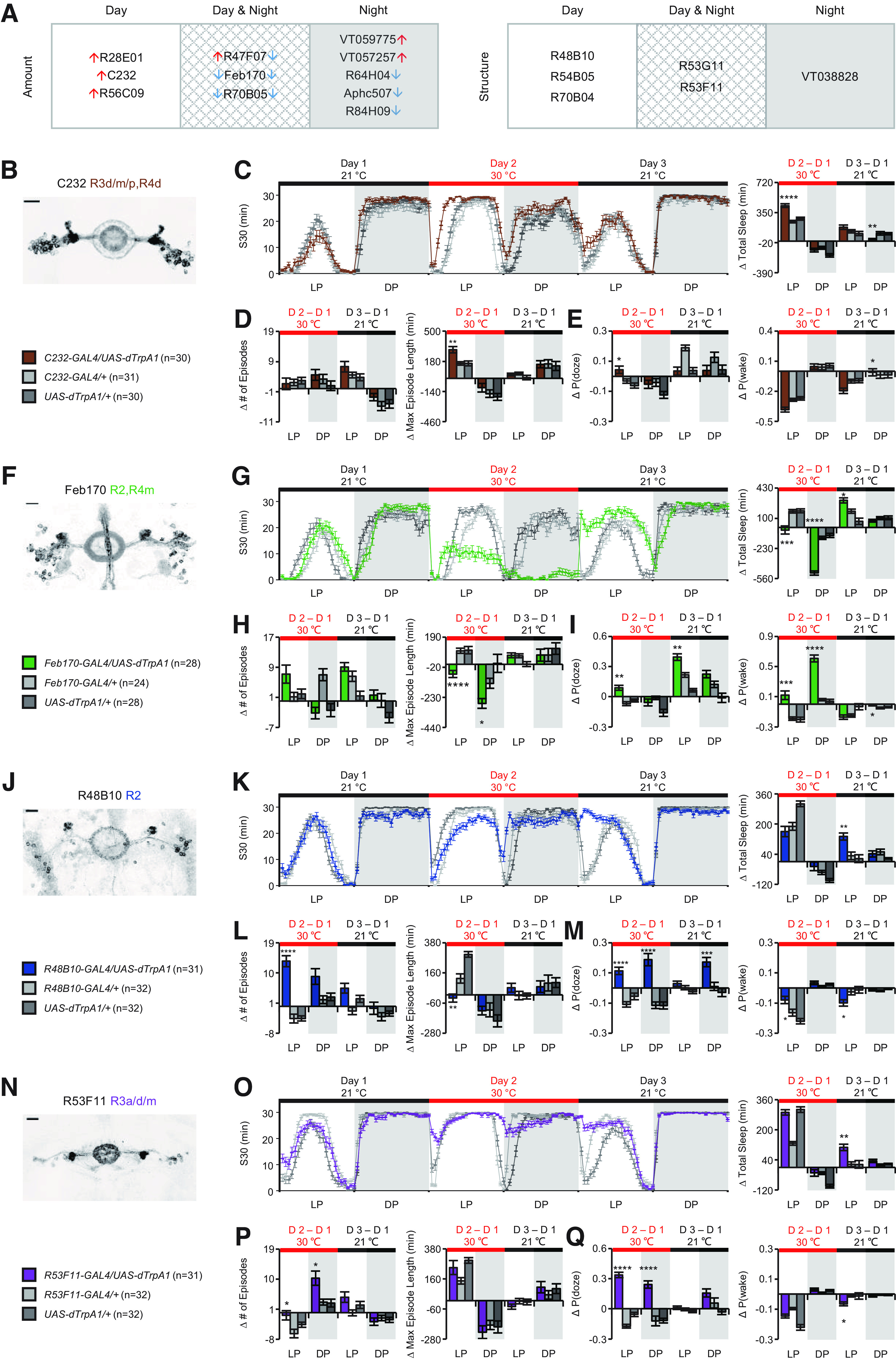

Results

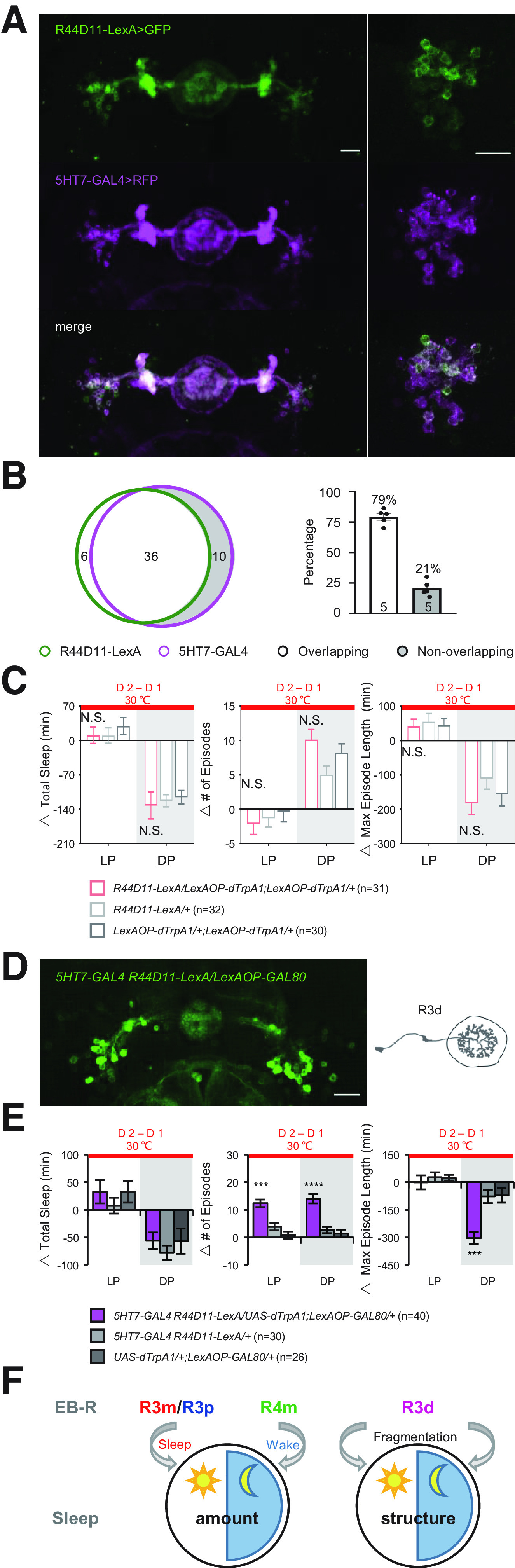

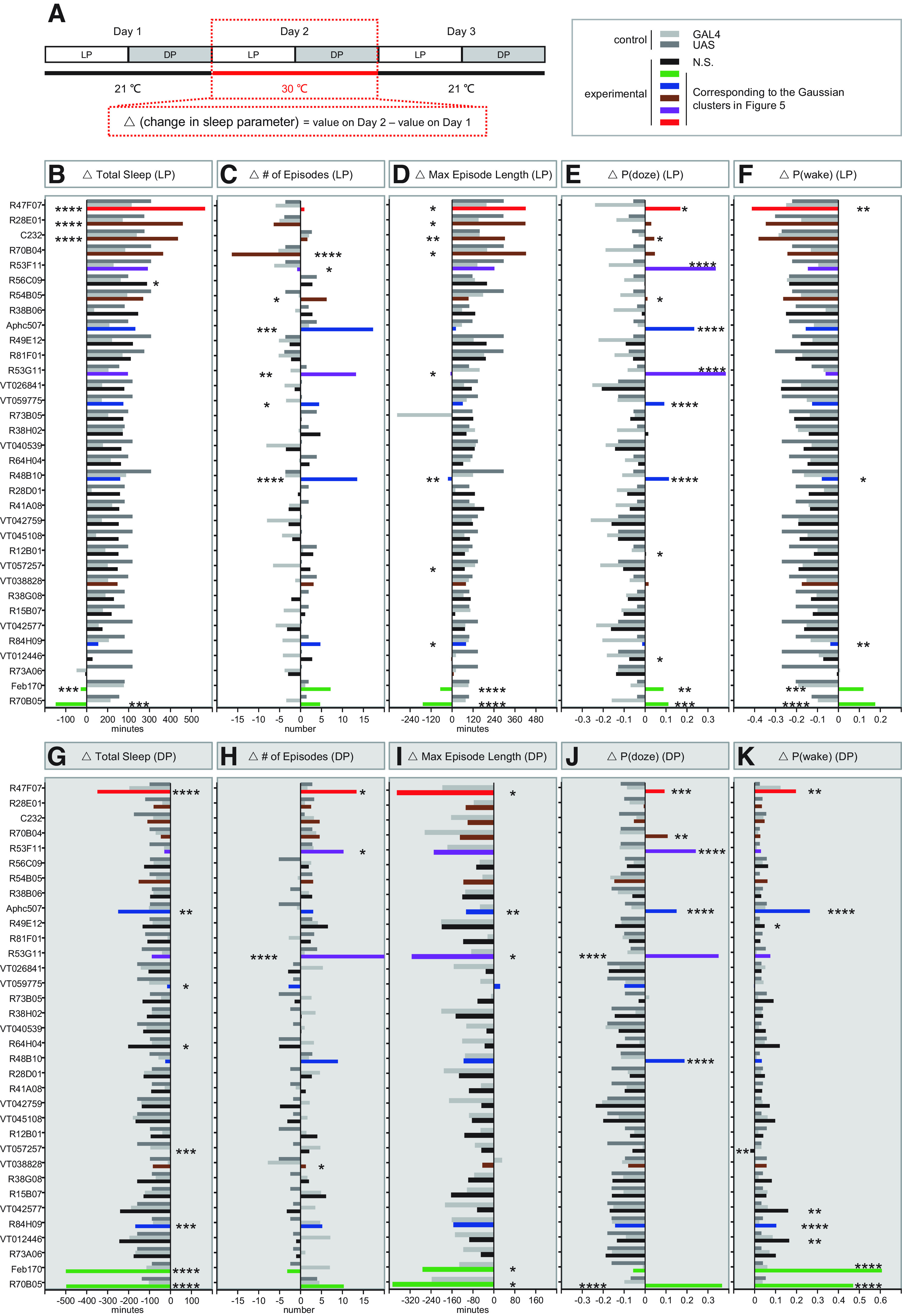

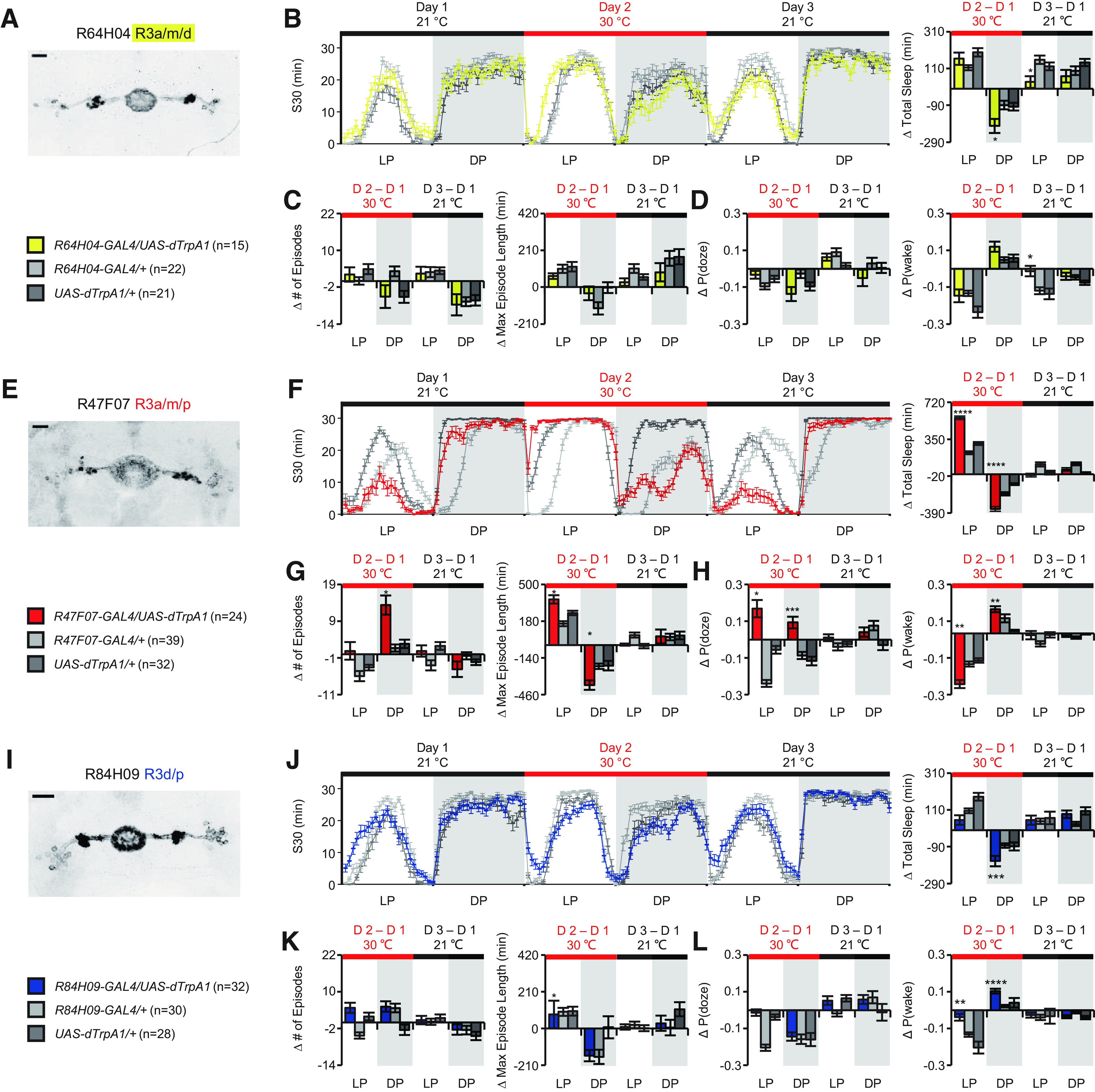

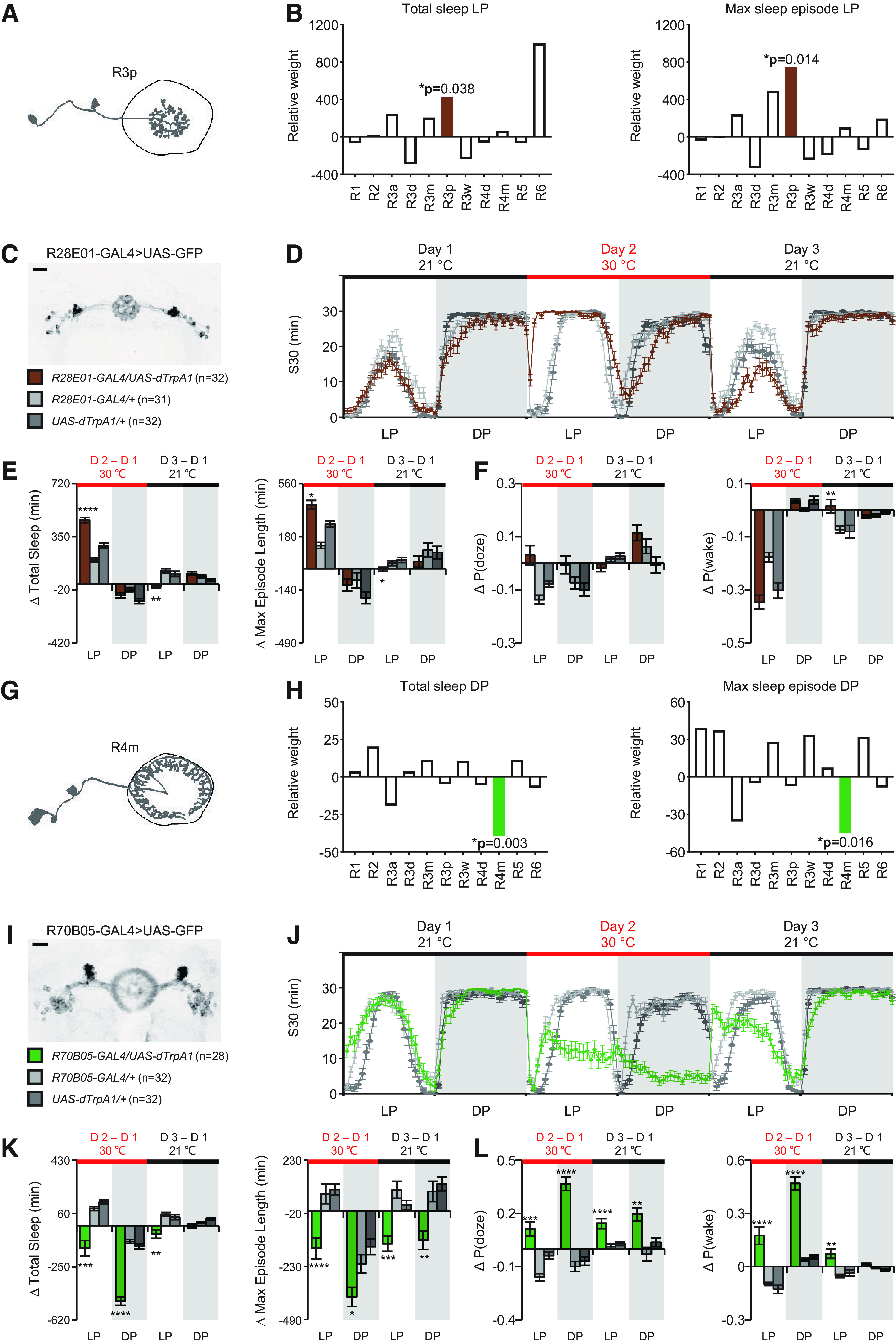

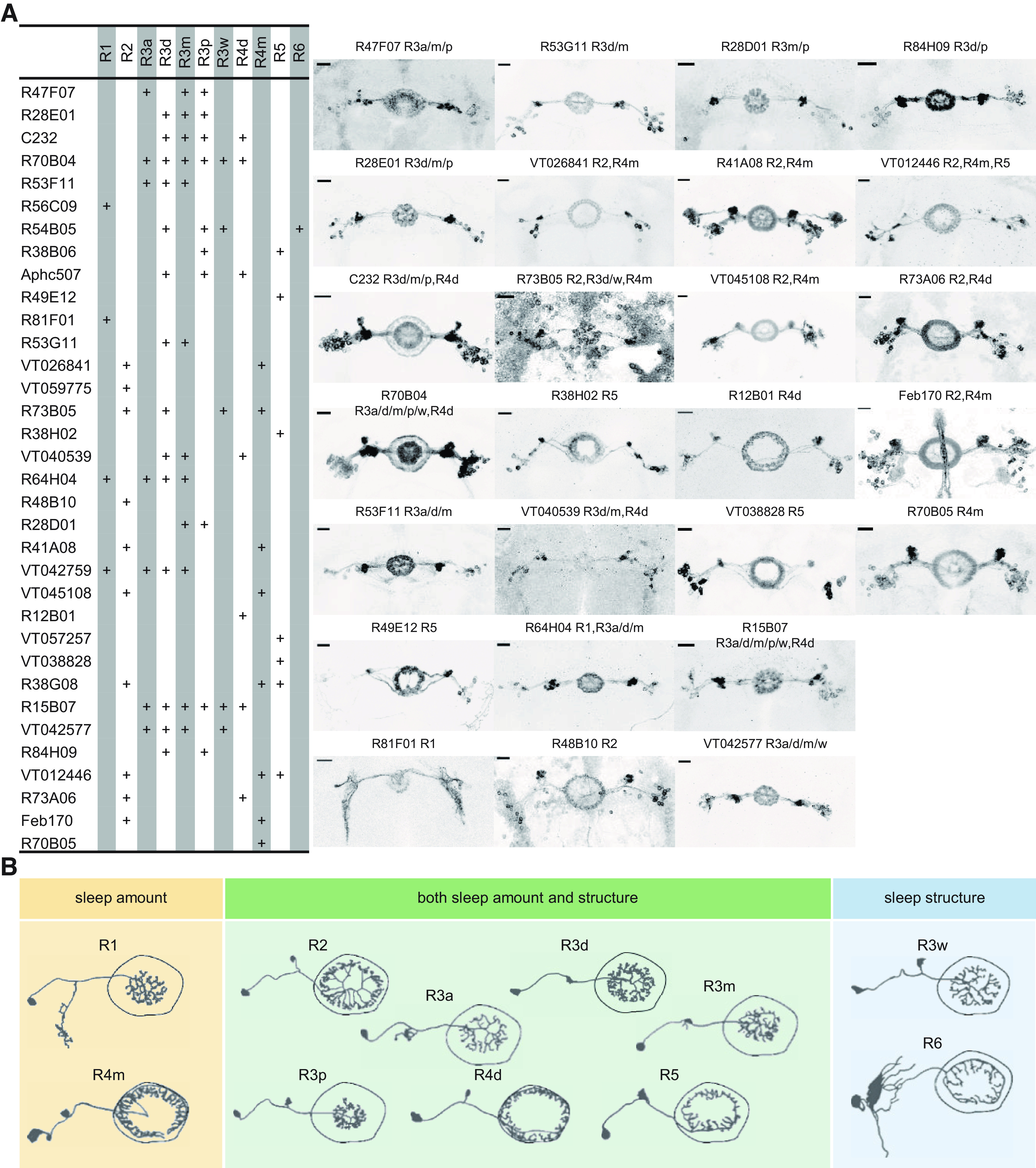

Thermoactivation of ring neurons changes sleep amount

To investigate the roles of ring neuron types, we collected 34 GAL4 drivers that label different populations of ring neurons and used them to drive the thermogenetic tool dTrpA1, allowing the use of elevated temperature to drive neuronal firing (Hamada et al., 2008). Animals were placed in DAM2 system tubes and entrained at 21°C in a 12 h:12 h light/dark cycle. Sleep was then recorded for 3 d: 1 d of baseline sleep at 21°C, 1 d of neural activation sleep at 30°C, then 1 d of recovery sleep at 21°C (Fig. 1A). Changes in sleep parameters for each genotype on the activation and recovery days were calculated by subtracting the baseline day value (Fig. 1A). Changes were only considered significant when the experimental group was different from both genetic controls. Changes in total daytime sleep of the 34 drivers on the activation day are arranged in descending order (Fig. 1B), and changes of total nighttime sleep (Fig. 1G) as well as changes in the number of episodes (Fig. 1C,H), maximum episode duration (Fig. 1D,I), P(doze) (Fig. 1E,J), and P(wake) (Fig. 1F,K) are displayed in the same order as the daytime sleep data to allow assessment of all parameter changes for each genotype. The color-coding of the histogram bars corresponds to the Gaussian clusters shown in Figure 5 and is also used to identify lines in Figures 2, 3, 6, and 7 as part of particular clusters.

Figure 1.

Sleep changes with activation of subtypes of ring neurons. A, Design of the experiments and calculation of sleep parameters on the activation day (red dashed box). B, G, Changes in sleep amount during day (LP) and night (DP). C, H, Changes in number of sleep episodes during daytime and night. D, I, Changes in maximum sleep episodes during daytime and night. E, J, Changes in P(doze) during daytime and night. F, K, Changes in P(wake) during daytime and night. Colored and black bars represent the experimental groups. Color codes are consistent through all of the figures and are based on the daytime cluster analysis in Figure 5. Gray and dark gray bars represent GAL4 control and UAS control, respectively. One-way ANOVA analysis and Dunn's multiple comparisons test were used. Significance, only when the experimental group is significantly different from both GAL4 and UAS controls: *p < 0.05. **p < 0.01. ***p < 0.001. ****p < 0.0001. Data are mean.

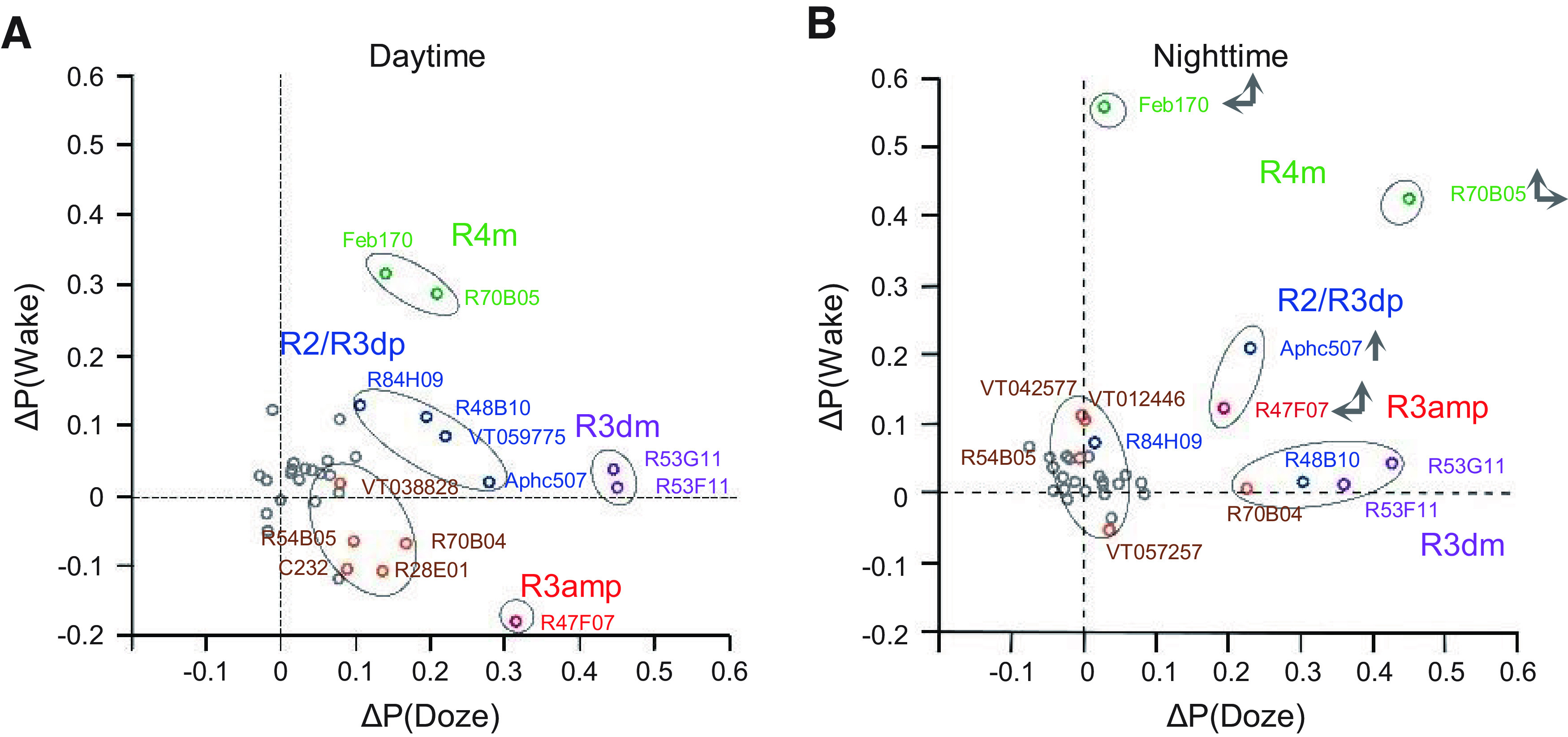

Figure 5.

Association of changes in arousal and sleep drive with GAL4+ groups of ring neurons. Mixed Gaussian model cluster analysis for drivers have similar patterns during the daytime (A) and at night (B). Gray dots represent activation did not show significance in P(wake)/P(doze) analysis. Green dots represent increase in both P(wake) and P(doze). Blue dots represent mild increase in both P(wake) and P(doze). Brown dots represent weak increase in both P(wake) and P(doze). Purple dots represent increase only in P(doze). Red dots represent increase in P(doze) and decrease in P(wake). Vertical and horizontal arrows in nighttime panel represent shifts in location of P(doze) and P(wake) compared with the daytime.

Figure 2.