Abstract

The COVID-19 global health crisis forced border closings, strained resources and tightened funding, forcing humanitarian organisations to innovate. This paper aims to identify gaps in the literature on innovation in humanitarian supply chains, and to develop an appropriate framework for future research through a systematic literature review. We use a systematic literature review approach and synthesis the discussion of innovation in humanitarian supply chains after reviewing 43 papers. The synthesis identifies the different contexts for and outcomes of innovation in humanitarian supply chains. Our findings indicate that research on innovation in humanitarian supply chains is an underdeveloped topic. Gaps we identified in regards to the humanitarian context are: (1) a limited discussion of the contribution by the beneficiary to the supply chain; (2) a limited discussion of reconstruction innovations; (3) a lack of study on field application for complex innovations; (4) the lack of discussion of the role of individual knowledge in humanitarian supply chain innovation and finally (5) a lack of study of position innovations where humanitarian organisations use supply chains as a way to market effectively towards donors.

Keywords: Humanitarian innovation, Humanitarian logistics, COVID-19

Introduction

The global health crisis, COVID-19 pandemic has affected the economy and society in every country. Concurrently, the continuing challenges of climate change, rising inflation, resource scarcities, and increased political instabilities around the world increase the complexity and ambiguity and uncertainty in humanitarian work. Access limitations due to lockdowns and border closings stranded migrants and refugees (Liem et al., 2020) and added another layer of complexity to ongoing humanitarian operations (Thompson & Anderson, 2021) straining already limited funding and resources. Limited funding and closed borders forced all sectors to be innovative in developing solutions (Heinonen & Strandvik, 2020) using local resources (OECD, 2021).

Humanitarian logistics and supply chain management play a crucial role in preparation for, and response to, both disasters and global health emergencies, and the alleviation of the suffering of vulnerable people. Importantly, the challenge facing the humanitarian supply chain managers is, arguably, more complex than that found in the ‘for profit' environment given its multiple stakeholders and the prominence of non-government organisations (NGOs), United Nations agencies and the Red Cross movement, and governmental actors (Kovács & Falagara Sigala, 2021). Humanitarian organisations face an unknown demand regarding location, quantity, and timing as well as physical and communications infrastructure challenges. Additionally, there is a need for agility and swift-trust as the failure of the supply chain can lead to death or unnecessary suffering rather than simply reduced profits (Dubey et al., 2020; Tatham & Pettit, 2010). These characteristics lead to volatile and unstable supply chains with multiple actors which, at least in theory, need to coordinate their response to gain agility (Dubey et al., 2021, 2022).

These particularities of the humanitarian supply chain would hint to a different approach to supply chain innovation than in the private sector. Indeed, Flint et al., (2005) highlight the importance of customer clue gathering activities and negotiating and clarifying activities that lead to inter-organisational learning and logistics and supply chain management innovation. This logistics innovation process contrasts to the humanitarian context where the customer is a beneficiary with little to no negotiating power over the services provided. Furthermore, Grawe (2009) in a review of logistics innovation highlight environmental factors such as regulation of logistics based inter-firm competition and a shortage of capital created a need for innovation. Like their commercial counter-parts humanitarian supply chains are also experimenting with emerging digital technologies and their potential implementation (Rodriguez-Espindola et al., 2020; Maric et al., 2022). Although humanitarian organisations compete over funding, they do not follow a similar model of competition through logistics and supply chain processes found in the private sector as humanitarian organisations actively try to coordinate supply chain activities. The potential for different approaches to supply chain innovation in the humanitarian context as well as increasing interest from practitioners and academics create a need to understand the current state of the literature and help orient further research. This paper tries to address that. This is an advanced and updated version of an earlier working paper published by Altay et al., (2018).

According to Sandvik, (2017) a few studies have mapped the humanitarian innovation ecosystem such as Bloom and Betts, (2013), Bessant et al., (2014), Betts et al., (2015), Ramalingham et al., (2015), and Obrecht, (2017). However, all these studies have been either done by practitioners or by third parties reporting to practitioners. In their review, Bessant et al., (2014) report that the humanitarian innovation field is immature and follows far behind the field of management innovation. This developing interest in innovation is found across the humanitarian sector as exemplified by the announcement in February 2012 of a new strategy from the UK Department for International Development (DFID). One of the aims of which is “to support innovation and promote more evidence-based responses to improve response and increase resilience” (DFID, 2014, p 10). Such policy changes are relevant for other countries (e.g. Finland, or the Netherlands) and as well as other donors (e.g. the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation). To improve the effectiveness of their supply chains and to maximise the efficient use of their funds, humanitarian organisations have begun developing a range of innovative solutions for humanitarian supply chains. Apart from governments, also international humanitarian organisations have set up their own innovation centres (e.g., UNICEF's Global Innovation Centre or UNHCR’s Innovation Service), and joined forces in developing innovation centres together, such as the Global Humanitarian Lab, or the Humanitarian Innovation Fund. The latter aims to "ensure that the outcomes of research, innovation, professionalisation processes and partnership building impact humanitarian action to improve humanitarian effectiveness" (ELHRA, 2014, p. 1). In addition to the interests of practitioners and stakeholders, there is also an increasing focus on research relating to innovation in the humanitarian sector from academics. However, such research is scant despite its relevance when it comes to humanitarian supply chain management (HSCM) (Munksgaard, et al., 2014; Pedrosa, et al., 2015; Su, et al., 2011).

Research on innovation in humanitarian supply chains does exist, but it is scattered and difficult to find (Bloom & Betts, 2013). It needs to be organized and categorized so that we can identify the direction it is going and what else is missing from the research. This paper conducts a systematic literature review (SLR) to identify relevant literature, to categorise it, and to identify the gaps in research to guide the next generation of humanitarian innovation research towards filling those gaps. The overall aim of the paper is to develop a conceptual framework for the classification of this literature. The main contribution of this paper is twofold: first, this is the first systematic review of academic literature on logistics and supply chain innovation in the humanitarian context. There have been many review articles published in the humanitarian context that focus on specific technological or management topics such as digital technologies (Maric, et al., 2022), big data (Gupta, et al., 2019) or quality management (Modgil, et al., 2022) however, none focused on innovation as a concept. Second, most systematic literature reviews identify gaps in the literature and based on that provide interesting research questions. But according to Post et al., (2020) identifying gaps in the literature and offering research questions are not sufficient make a theoretical contribution and need to be supported by a framework to stimulate further research. Our study does exactly that.

To meet the aim of identifying gaps and developing an appropriate framework for future research the literature review begins with the formulation of two questions: (1) Which factors affect humanitarian supply chain innovation? And (2) How does humanitarian supply chain innovation help improve the performance of such supply chains? These questions are not necessarily built on theory but rather we use them to guide our review of the literature. The questions provide a lens that we look through when we read the final set of papers identified for the study in order to develop our framework on innovation in humanitarian supply chains.

Definitions

Betts and Bloom, (2014) define innovation as “a means of adaptation and improvement through finding and scaling solutions to problems, in the forms of products, processes or wider business models” (p. 5). They also add that the concept can be applied to nearly any specialized area such as logistics and supply chain. Therefore, we can argue that humanitarian innovation is innovation in the humanitarian context.

Innovation is about exploiting change as an opportunity (Drucker, 1985). It is a concept that is connected to creativity, invention, and entrepreneurship (James & Taylor, 2018). Unlike invention (i.e. creating something new), innovation is about improving that exist and can be useful. It is “the process of change that leads to positive social impact” (James & Taylor, 2018, p. 5). Supply chains play a dual role about innovation in that (a) innovation transforms supply chains, and (b) supply chains can facilitate the spread of innovations between organisations. Thus, in one of the first papers to discuss innovation in logistics and supply chain management, Flint et al., (2005, p.114) offered the following definition for innovation: “[…] any service from the basic to the complex that is seen as new or helpful to a particular focal audience.” Indeed, this approach in which innovation is defined as "newness" as innovation is found more broadly in the literature, (e.g. Rogers, 1995). Therefore the above definition of innovation will be used in this paper, not least as it will avoid artificially constraining the subsequent review of the literature. HSCM on the other hand, can be defined as the flow of resources and relief to people in need (Narayanan & Altay, 2021). One of the initial definitions of logistics operations in the humanitarian context was put forward by Thomas and Kopczak in 2005 where: “Humanitarian logistics is the process of planning, implementing and controlling the efficient, cost-effective flow and storage of goods and materials, as well as related information, from the point of origin to the point of consumption for meeting the end beneficiaries’ requirements” (Thomas & Kopczak, 2005, p. 2).

However, logistics is only one of the functions within a supply chain. Mentzer et al., (2001) define supply chain management in the commercial sector as “the systemic, strategic coordination of the traditional business functions and the tactics across these business functions within a particular company and across businesses within the supply chain, for the purposes of improving the long-term performance of the individual companies and the supply chain as a whole” (p.18). Adapting this definition to the humanitarian context we define HSCM as the systemic, strategic coordination of sourcing, procurement, storage and movement of physical relief goods and donations and the tactics across these functions within a particular humanitarian organization and across other actors within the humanitarian system, for the purposes of alleviating human suffering. Also, following the disaster relief cycle, we include preparedness and reconstruction activities across different geographic locations and through multiple stakeholders in our understanding of HSCM. The scope of this paper is limited to research in logistics and supply chain management innovation in the humanitarian context.

Methodology

Systematic literature reviews (SLRs) aim to synthesise findings and draw comparisons from a collection of studies especially in the case of heterogeneous data (Tranfield, et al., 2003), and this research method has been adopted in humanitarian operations and logistics/supply chain management research across a wide range of topics (Behl & Dutta, 2019; Banomyong et al., 2019; Gupta et al., 2019; Modgil et al., 2022; Queiroz et al., 2022; Maric et al. 2022). This paper follows the tradition of a scoping review because our main goal is to “examine the extent, range and nature of research activities and identify research gaps in the extant literature” (Paré et al., 2015, p.186).

All systematic literature reviews have the basic structure of Planning, Conducting, and Reporting. Denyer and Tranfield’s seminal works (Denyer & Tranfield, 2009; Tranfield, et al., 2003) on developing evidence-informed systematic reviews extends this three-step approach to five steps: (1) question formulation, (2) locating studies, (3) study selection and evaluation, (4) analysis and synthesis, and (5) reporting and using the results. These five steps are similar in their approach to what others have also proposed (Fink, 2005; Seuring & Gold, 2012). Furthermore, Breslin and Gatrell, (2020) argue that literature reviews play an increasingly important role in theory development and identify “eight strategies located on a continuum ranging from miners—who position their contributions within a bounded and established domain of study alongside other researchers—to prospectors, who are more likely to step outside disciplinary boundaries, introducing novel perspectives and venture beyond knowledge silos” (p. 1). Our approach in this paper falls under the “miners” category, where we identify research gaps, and organize and categorize literature. We develop a research agenda that draws on the critical analysis of previously published works. However, Post et al., (2020) argue that identifying gaps in the literature and offering stimulating research questions are not enough to make a theoretical contribution and need to be accompanied by another form of synthesis such as a framework or taxonomy. Consequently, we develop a framework for innovation in humanitarian supply chains as a result of our systematic literature review. Where Denyer and Tranfield’s work really comes in is the rigor of the methodology. Explicit and rigorous research processes are crucial for ensuring replicability, transparency, and thoroughness of the work (Tranfield, et al., 2003). As a result, our choice of using Denyer and Tranfield, (2009) and Tranfield et al., (2003) is not arbitrary. On the contrary, these two sources represent the “best practices” in conducting literature reviews.

This rest of this methodology section lays out the steps relevant to the Denver and Tranfield, (2009) ‘study selection and evaluation’ and the ‘analysis’ element of the ‘analysis and synthesis’ stages before moving to the next section of findings and discussion.

The relevant literature was selected based on a series of specific criteria, with searches undertaken for scholarly peer-reviewed articles on the Proquest, EBSCO, Emerald Insight, Science Direct and SCOPUS databases. The search period covered the dates of 1990/01/01 to 2021/31/05. Since the databases used in this study all have different starting points in terms of how many years their records go back, we needed a common starting point for our search. The date of 1990 was selected the starting point for our search for two reasons: first, Altay and Green, (2006) and Van Wassenhove, (2006) both argue that operations and logistics/supply chain management research in the humanitarian context is scant before 2000s; and second, Barnett, (2005) argues that the humanitarian sector has become more professional and institutional during the 1990s.

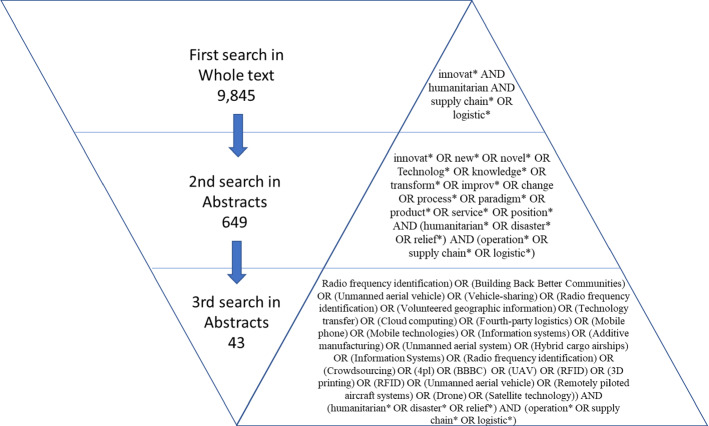

An initial search was undertaken to narrow down the articles and target those specifically focused on innovation using the following keywords in the whole text: (innovat* AND humanitarian AND (supply chain* OR logistic*)), thereby identifying articles where the word innovation was present. However, this search excluded papers where innovation is discussed but not mentioned as through the word "innovation". Thus, to extend the review to capture these potential articles an additional search was carried out. This new search was done on the papers’ abstract to include and focus on three new types of keywords. These additional keywords were selected based on the following criteria: The first type of keywords focused on the principle of innovation as "newness" and as a transformation of something which can sometimes include technology or knowledge. The second types of keywords follow the ‘4P' (product, process, position and paradigm) model of innovation developed by Francis and Bessant, (2005). Finally, the third type of keywords aimed to expand the HSCM context to include disasters, relief and operations. This additional search used the following Boolean operators: ((innovat* OR new* OR novel* OR Technolog* OR knowledge* OR transform* OR improv* OR change OR process* OR paradigm* OR product* OR service* OR position*) AND (humanitarian* OR disaster* OR relief*) AND (operation* OR supply chain* OR logistic*)). From the initial selection of articles a trend in innovation topic was identified, and a third search was done to cover the relevant topics according to the following keywords: ((Radio frequency identification) OR (Building Back Better Communities) OR (Unmanned aerial vehicle) OR (Vehicle-sharing) OR (Radio frequency identification) OR (Volunteered geographic information) OR (Technology transfer) OR (Cloud computing) OR (Fourth-party logistics) OR (Mobile phone) OR (Mobile technologies) OR (Information systems) OR (Additive manufacturing) OR (Unmanned aerial system) OR (Hybrid cargo airships) OR (Information Systems) OR (Radio frequency identification) OR (Crowdsourcing) OR (4pl) OR (BBBC) OR (UAV) OR (RFID) OR (3D printing) OR (RFID) OR (Unmanned aerial vehicle) OR (Remotely piloted aircraft systems) OR (Drone) OR (Satellite technology)) AND (humanitarian* OR disaster* OR relief*) AND (operation* OR supply chain* OR logistic*). The complete search process is summarised in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Diagram summarizing the search and filtering process

The initial search resulted in a total of 9,845 articles, which were evaluated based on their titles. The second search produced 649 articles. Evaluation of these articles based on their titles and abstracts brought this number to 26. These 26 articles pointed to specific innovations which led us to the third search, which produced 17 more articles, totalling 43 viable published papers based on the definitions set out previously in the paper, which represent a broad range of innovation in humanitarian supply chains. The articles were then reviewed and coded by the authors.

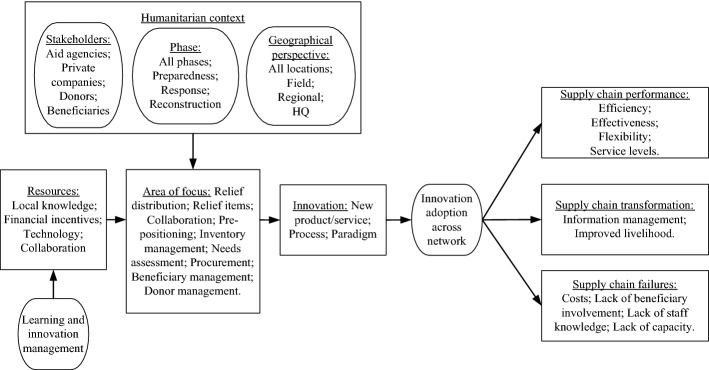

An initial framework was developed based on one of the first literature reviews on logistic innovation done by Grawe, (2009) in which the author highlights the importance of the antecedents and outcomes of logistics innovation. Grawe’s framework discusses the role of both environmental and organisational factors, and how they can lead to logistics innovation and subsequent competitive advantage. This paper adapts Grawe’s framework in three ways: First, we replace the organisational factors by factors relevant to the humanitarian context based on the literature review developed by Kovács and Spens, (2007) which highlight the importance of disaster phases, stakeholders and a geographical perspective. The framework of these authors emphasizes the linkage between stakeholders, the disaster phase(s) and a geographical perspective. Second, to obtain a further level of detail in the analysis of innovations, the type of innovation is identified based on the ‘4P’ model of product, process, position and paradigm from Francis and Bessant, (2005). Third, instead of focusing on competitive advantage, this paper considers performance outcomes—a necessary adjustment that reflects the reality that, unlike their ‘for profit’ counterparts, competitive advantage is not the goal of humanitarian organisations. Figure 2 illustrates the initial framework.

Fig. 2.

Initial framework to guide the literature review

Several different methods have been used to develop literature reviews, with the main approaches being: aggregation, integration, interpretation and explanation (Rousseau, et al., 2008). The “synthesis by integration” approach was selected for this research as it is most appropriate for literature reviews which include multiple data collection methods, and which employ pre-determined questions and selection criteria (Rousseau, et al., 2008). Synthesis by integration aims to collect and compare evidence across multiple data collection methods and employs predetermined questions and selection criteria. Both judgement and interpretation are crucial with this approach, and the outcome helps develop both declarative knowledge (what are the facts) as well as procedural knowledge (how to use the facts). This duality of knowledge creates an understanding of what factors constitutes humanitarian supply chain innovation, how these factors interact and what outcomes they create.

The coding process follows a two-step process. First, the themes put forward in the initial framework (Fig. 2) help develop a thematic coding approach. Second, an open coding approach help organize emerging themes to identify the areas of focus of the innovation and the different types of innovation outcomes an open coding approach. Certain themes were present in only a single article but are still put forward as relevant to the overall findings.

Descriptive analysis

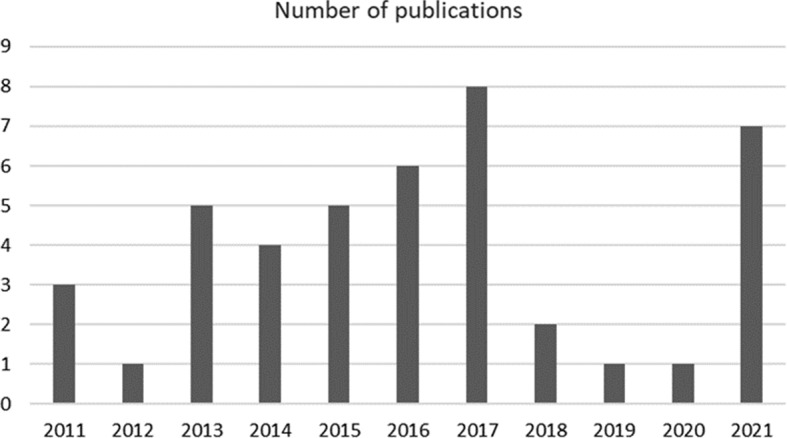

As indicated earlier, the search process led to the selection of 43 articles and, although this was undertaken across the period 1990/01/01 to 2021/31/05, there are no relevant papers before 2011. Figure 3 shows the distribution of papers for the period 2011–2021 where the topic of innovation in humanitarian supply chains, although remaining limited, has increased slightly over time.

Fig. 3.

distribution of publications per year

Table 1 identifies the journal for the selected papers; the range of these journals highlights the background and cross-disciplinary context of humanitarian supply chain innovation.

Table 1.

Journals and their respective number of selected papers:

| Journal | # of papers |

|---|---|

| Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management | 10 |

| Procedia Engineering | 3 |

| Production and Operations Management | 3 |

| Transportation Research Part C | 2 |

| Annals of Operations Research | |

| Frontiers in Public Health | |

| Annual Reviews in Control | 1 |

| Applied Soft Computing | |

| Automation in Construction | |

| Disasters | |

| Disaster Prevention and Management | |

| European Journal of Operational Research | |

| Info-The Journal of Policy, Regulation and Strategy for Telecommunications | |

| Information Technologies & International Development | |

| International Journal of Production Economics | |

| International Journal of Production Research | |

| International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment | |

| International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction | |

| International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | |

| Journal of Network and Computer Applications | |

| Journal of Global Operations and Strategic Sourcing | |

| Production Planning and Control | |

| Omega | |

| Supply Chain Management: An International Journal | |

| Thunderbird International Business Review | |

| Transportation Research Part E | |

| Vaccine |

Findings

To understand the factors that affect humanitarian supply chain innovation as well as how such innovations help to improve humanitarian supply chain performance, this review analyses the contribution of the 43 selected papers. It is not only the type of innovation but also the general context for innovation that does much to shape the resulting outcomes. Haavisto and Kovács, (2015) even noted that the impact of innovation is not necessarily positive as innovation in one sector could even hamper the resilience of another area with regards to HSCM. Thus, the categorisation of innovation in humanitarian supply chains needs to pay attention to the type of innovation itself, the context of the innovation, as well as its potential impact.

Table 2 identifies four characteristics- disaster phase, actor, location and focus area- as relevant aspects of the humanitarian context for each type of innovations. As for the innovation itself, the categorisation in Table 2 follows Francis and Bessant’s, (2005) 4P model. However, given that the HSCM literature includes a stronger logistics service focus, we further separated products and services in the table. Furthermore, one may, of course, debate whether an unmanned vehicle is a new product or a new technology; in any case, it supports relief distribution rather than being a relief item. Even so, it is possible to further subdivide the "new product" category into innovations with regards to relief items vs innovations that support the delivery of relief items. Given that our SLR has focused on HSCM, not surprisingly, our findings are geared towards innovations supporting logistical activities (i.e. new types of vehicles) rather than new relief items.

Table 2.

Four characteristics of humanitarian context by innovation type

| Innovation type (Francis & Bessant, 2005) | Disaster phase (1) | Actors (2) | Locations (3) | Focus area(4) | Examples from articles |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| New product | Immediate response | Humanitarian organisations | Field (last-mile) | Relief distribution; Relief items | UAVs/drones (Chowdhury et al., 2017; Haidari et al., 2016; Tatham et al., 2017a); autonomous vehicles (Mosterman et al., 2014); medical maggots (Tatham et al., 2017b); hybrid cargo airships (Tatham et al., 2017c); web-tools for supply–demand matching (Courcol et al., 2021); DSS using opensource imaging (Griffith et al., 2019) |

| New service | All phases; primarily preparedness and immediate response | Logistic service providers; humanitarian organisations; beneficiaries | All locations; regional; field | Collaboration; relief distribution; pre-positioning | 4PL services (Abidi et al., 2015); tracking & tracing (Baldini et al., 2012; Delmonteil & Rancourt, 2017; Ergun et al., 2014; Ozguven & Ozbay, 2013; Ozguven & Ozbay, 2015; Yang et al., 2011; Biswal et al., 2018); inventory pre-positioning (Dufour et al., 2018); web-based service for evacuation (Hadiguna et al., 2014) |

| New process | All phases; primarily preparedness and immediate response | Beneficiaries; humanitarian organisations; donors | All locations; HQ; field; regional | Relief distribution; inventory management; needs assessment; procurement | GIS for pre-positioning equipment (Chen et al., 2011); public procurement for innovation (Haavisto & Kovács, 2015); management of medical technology transfer (Santos et al., 2016); new funding mechanism for inventory allocation (Natarajan & Swaminatha, 2017); cloud computing for information sharing (Schniederjans et al., 2016); decision making through mobile phones (Serrato-Garcia et al., 2016); information systems and technology implementation management in the field (Tussime & Byrne, 2011; Patil et al., 2021); information gathering through voice-enabled technology (Waidyanatha et al., 2013); application of Industry 4.0 (Dubey et al., 2020; Kumar & Singh, 2022; Zahedi et al., 2021); order facilitation for stressful environments (Barnes et al., 2014); optimisation using social vulnerability (Alem et al., 2021) |

| New paradigm | All phases | Donors; beneficiaries | Field | Beneficiary; supplier management; donors | Paradigm shift through cash transfer programmes (Abushaikhaa & Schumann-Bölsche, 2016; Heaslip et al., 2018), or 3D printing (He et al., 2021; Tatham et al., 2015); best practice design (Bornstein et al., 2013); sharing economy for relief distribution (Hirschinger et al., 2016; L’Hermitte and Nair, 2021); use of local knowledg0e/capacity in humanitarian logistics (Sheppard et al., 2013; Sodhi & Tang, 2014); multi-sector partnerships to produce relief items (Vinson et al., 2021) |

While the 4P model was useful in understanding innovations in the humanitarian supply chain, as the analysis shows, some articles discussed innovations that included multiple categories of the 4P model at the same time. For example, 3D printing (Tatham et al., 2015), in itself a new manufacturing process, also leads to a paradigm shift in the thinking about humanitarian supply chains concerning their supply chain configuration, the choice of suppliers, and the delivery mechanism. When faced with an important change that, because of one or multiple innovations creates a new supply chain paradigm, the category put forward is that of a new paradigm instead of a split across multiple innovations. Other innovations such as tracking and tracing also include a duality where a new product (such as a RFID chip) enables new services to improve tracking and tracing, in such cases the application is considered a new service in Table 2.

The disaster phase column indicates the phase an innovation targets in disaster relief, based on Kovács and Spens', (2007) phase model of preparedness—immediate response—reconstruction. For example, the use of drones is primarily put forward for needs assessment and relief distribution in the immediate response phase of disaster relief. In contrast to the use of drones for distribution during response, innovations for tracking and tracing with RFIDs are present in all phases (Yang, et al., 2011; Baldini, et al., 2012; Ozguven & Ozbay, 2013; Ozguven & Ozbay, 2015; Biswal et al. 2018). Solutions pertinent to all phases are often complex and require a central management function to oversee the implementation of relevant standards across the supply chain; this in turns makes the innovation present at multiple locations across the supply chain.

Next, the table indicates which actors an innovation is targeted at, using Heaslip et al., (2012) differentiation across actors and stakeholders in disaster relief. There are some articles addressing actors other than humanitarian organisations. One article on new services discusses the role of logistics service providers for the humanitarian context (Abidi, et al., 2015). Another two articles discuss the role of donors, one through a new process of inventory financing (Natarajan & Swaminatha, 2017) and another through a new paradigm where the donors organise a contest as a request for proposal to find the best design for reconstruction (Bornstein, et al., 2013).

Interestingly, some of these innovations include the beneficiaries. For example, Hirschinger et al., (2016) discuss the use of sharing economy principles for relief distribution by beneficiaries themselves. The inclusion of beneficiaries as "actors" is somewhat surprising as this approach itself is disputed in HSCM literature (Heaslip et al., 2012). Usually, the literature identifies beneficiaries only as aid recipients, yet several examples from the innovation in HSCM literature grant them more in-depth roles. Innovations in this category can be new processes, which offer different approaches to obtaining needs information using mobile phone applications (Abushaikha & Schumann-Bölsche, 2016; Serrato-Garcia, et al., 2016; Waidyanatha, et al., 2013).

Another approach for beneficiary involvement considers potential paradigm changes involving the activities undertaken by the beneficiaries where the beneficiary could take on a role in the supply chain of humanitarian organisations. One such article discusses the use of micro-retailers and cash vouchers to organise the immediate response and to improve last-mile distribution to affected communities (Sodhi & Tang, 2014). Another article focuses on increasing the involvement of local populations with a systemic change to funding, training, and command and control (Sheppard, et al., 2013). The articles that advance the concept of co-opting the beneficiary argue that the beneficiary is best placed to know what is required in the context of a humanitarian crisis as well as provide resources about supply chain activities. This co-optation results in a paradigm shift as, in this model, the beneficiary is directly involved in making decisions about the resources that should be prepositioned or distributed and this, in turn, simplifies the decision-making by humanitarian organisations. Such an approach would lead humanitarian organisations to relinquish some of the control of their supply chain to let the beneficiary manage a particular aspect of the aid flow.

Additionally, Table 2 shows the geographical location for the innovations. Some are decidedly for the headquarters (HQ) levels of organisations, while those focusing on last mile relief distribution are dedicated to field logisticians. Kovács and Spens, (2007) highlight the importance of regional and extra-regional actors which undertake different roles during preparedness but interact during the response. However, in the literature review, the regional perspective was not highlighted. Rather, apart from the literature that focused on including the beneficiary, distinctions about the location of an innovation centred on an organisational perspective: the headquarters level, regional levels, and the field level, as well as across all levels. At the headquarters level, the literature considered preparedness activities with new processes for improving procurement activities (Haavisto & Kovács, 2015). At the regional level, there was a discussion of new processes relating to IT implementation activities (Tusiime & Byrne, 2011), as well as new services for regional warehouse activities (Dufour, et al., 2018).

Innovations in the field which do not cover all phases include new paradigms as well as new products. New products are often relevant in the context of transportation towards the last mile with the example of UAVs found in multiple articles (Chowdhury et al., 2017; Haidari et al., 2016; Tatham et al., 2017a). Another innovation which is field specific is paradigm changes which include activities with the beneficiaries such as beneficiary co-optation into the supply chain. Finally, an innovation that is field specific and falls into the new process category focuses on needs assessment where technology helps reaching out to the beneficiary for information.

Last but not least, the table shows the different logistical focal areas for the innovations; whether they are to assist and support needs assessment, relief distribution, pre-positioning, inventory management, or the collaboration between humanitarian organisations. For example, new processes include a new form of donor funding to improve inventory availability (Natarajan & Swaminatha, 2017) and information management through cloud computing (Schniederjans, et al., 2016).

Notably, two of the 43 articles focus on innovation diffusion (Haavisto & Kovács, 2015; Santos et al., 2016), while two others do not directly discuss a particular innovation. Anjomshoae et al., (2017) propose a dynamic balanced scorecard for supply chain for humanitarian organisations that includes innovation management as part of perspectives on learning and innovation. Özdamar and Ertem, (2015) review the use of mathematical models and geographic information systems for routing purposes and their relation to different disaster phases.

Beyond the environmental characteristics of the humanitarian context, there are also organisational factors that, based on the resources available, will influence supply chain innovation outcomes. Table 3 puts forward the organisational resources and supply chain outcomes identified for each innovation type. Grawe, (2009) in his review of logistics innovation identifies knowledge, technology, relationship networks, financial resources and management resources as different organisational factors that drive innovation. Similar factors are present within a humanitarian organisation’s management of supply chain innovation. These resources include networks, technology, financial resources and knowledge, which may/may not be combined.

Table 3.

Organisational resources and supply chain outcomes for innovation types

| Innovation type | Resources | Expected performance |

|---|---|---|

| New paradigm | Local knowledge; financial incentives; technology | Improved livelihood; service; resilience; effectiveness; efficiency |

| New process | Financial incentives; Collaboration; technology | Service; efficiency; innovation diffusion; effectiveness, flexibility, information Management |

| New product | Technology | Flexibility; effectiveness; efficiency; service |

| New service | Technology; collaboration | Efficiency; effectiveness; flexibility; security; information management; service |

For new paradigms where the beneficiary is involved in the innovation, the primary factor is the local knowledge from the beneficiaries who are perceived to have better knowledge of their capacity and need (Hirschinger, et al., 2016; Sheppard, et al., 2013; Sodhi & Tang, 2014). The new paradigm that concern 3D printing uses a particular technology (Tatham, et al., 2015) while the new paradigm which focuses on supplier management includes the use of financial incentives by donors to promote their innovative ideas (Bornstein, et al., 2013). Donor financing (and its limitations) can also create new processes through funding availability shortcomings prompting humanitarian organisations to search for new funding mechanisms (Natarajan & Swaminatha, 2017). Finally, financial incentives are also used to apply pressure on suppliers to obtain innovative solutions (Haavisto & Kovács, 2015).

Another resource is a network of actors, which collaborate to implement a new process. Such networks can revolve around the sharing of technology such as medical equipment (Santos, et al., 2016) or sharing of information through IT systems (Serrato-Garcia, et al., 2016). New processes, which focus on information management, might also be developed using only IT systems with services available such as the use of cloud computing (Schniederjans, et al., 2016). New processes for information also include the development of simple applications to simplify the process of accessing beneficiary information (Waidyanatha, et al., 2013), or to improve internal processes of tracking and tracing (Tusiime & Byrne, 2011).

Except for those new processes, which include financial incentives as well as complex information systems such as Cloud Computing, all new processes are developed internally by new organisations to reorganise their activities. Turning to new products, these can reflect multiple technology systems integrated together, for example automated and/or remotely controlled vehicles (Chowdhury, et al., 2017; Haidari, et al., 2016; Mosterman, et al., 2014; Tatham, et al., 2017a, 2017b). New products can also come as complete solutions such as hybrid cargo ships (Tatham, et al., 2017c). New services include IT systems with the development of decision-making tools for disaster response (Hadiguna, et al., 2014) and managing the UNHRD network depot (Dufour, et al., 2018). Another approach is to develop relevant services offers through external 4PL services (Abidi, et al., 2015). Finally new services will also focus on tracking and tracing and extensive and resilient technology networks for multiple solutions with RFID systems (Yang, et al., 2011; Baldini, et al., 2012; Őzgüven & Őzbay, 2013, 2015; Biswal et al. 2018) and satellite technologies (Delmonteil & Rancourt, 2017).

The outcomes of innovations vary across the literature, and not all articles highlight a supply chain transformation as their innovation. For instance, in the case of new processes to manage innovation in procurement, the outcome is innovation diffusion (Haavisto & Kovács, 2015). One result of some new processes or services is an improvement in information management with an increase in the scope of coverage or the quality of the information provided (Tusiime & Byrne, 2011; Yang, et al., 2011; Waidyanatha, et al., 2013; Serrato-Garcia, et al., 2016; Delmonteil & Rancourt, 2017). The assumption is that improving information management will help a humanitarian organisation make better decisions and enhance its performance. Innovations can also have multiple performance outcomes combined with efficiency, effectiveness, flexibility, service level, livelihood improvements and resilience. Effectiveness focuses on the proper use of resources, efficiency focuses on managing costs, while flexibility focuses on being responsive to unexpected events. Furthermore, an innovation that focuses on service levels can cover different issues such as beneficiary access, the speed of response or specific health outcomes. Innovations which include resilience and improved livelihoods are linked to new paradigms where the local population is involved (Hirschinger, et al., 2016; Sodhi & Tang, 2014). Outside of this association, there is no clear link between the area of focus or type of innovation, which relates to a particular performance outcome.

While limited, there are a few articles, which discuss potential barriers to innovation implementation. Ergun et al., (2014) put forward the role of costs of technology, which influences the adoption. Delmonteil and Rancourt, (2017) also suggest costs as well as lack of skill and training needs, resource investments and cooperation with technology providers. Dufour et al., (2018) highlight the lack of capital, storage capacity or need for buying large quantities in the context of a regional warehouse service. Santos et al., (2016) specifically study the role of barriers to technology transfer between organizations and highlight the following issues: difficulties with compliance to standards, lack of supply and servicing, lack of appropriate testing, uncertainty on the local setting and changes of priorities, challenges for transportation and implementation, lack of expertise and training, lack of equipment use, partial media coverage, non-adherence to humanitarian principles, creation of aid dependency and unclear processes for transition. There is only one article showing an example of a failed innovation which concerns the use of a request for proposal for Building Back Better Communities (BBBC) reconstruction program where proposed solutions did not match relevant beneficiary requirements as the beneficiaries were not involved (Bornstein, et al., 2013). This negative outcome highlights the importance of beneficiary involvement in reconstruction activities.

Finally, two articles discuss innovation management approaches. The first article by (Tusiime & Byrne, 2011) goes in depth on the issue of innovation adoption and discusses the multitude of adoption perspectives, which usually follow step-by-step phases of evaluation, awareness, initiation and pre-adoption. However, Tusiime and Byrne, (2011) note that the unique characteristics of the humanitarian context require to go beyond traditional innovation adoption phase models and adopt a translation model. In this type of model, innovations encompassing different network actors shape the outcome. This approach is relevant to the humanitarian context where field implementation can have different challenges from location to location.

The second article by Anjomshoae et al., (2017) proposes a dynamic balanced scorecard for supply chain for humanitarian relief organisations' performance management. This dynamic balanced scoreboard includes innovation management as part of perspectives on learning and innovation. The authors put forward two ways that innovation management can help humanitarian organisations: (1) information capital and knowledge management for continuous improvement and adoption of best practices and (2) human resource management for staff training and management and organisational capital to nurture leadership and improve coordination. These perspectives aim to improve the service quality and depend on proper budget, cost and fund management. (Anjomshoae, et al., 2017).

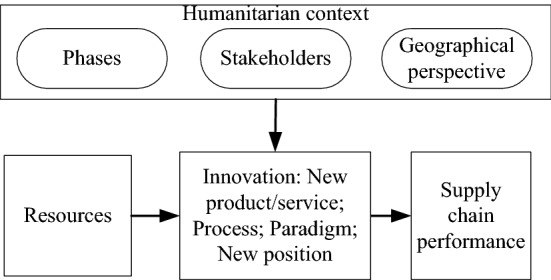

The rudimentary initial mental model we developed in Fig. 2 is now fed our findings (summarized in Tables 2 and 3) to develop Fig. 4, which offers a comprehensive framework based on our analysis. Its use makes it possible to understand both the context and resources that shape innovations in humanitarian supply chains and also to identify the output of the innovation process and the barriers which hinder innovation. In doing so, the framework highlights the different area of focus for innovation in humanitarian supply chains as well as the multiple potential outcomes of such innovations.

Fig. 4.

Comprehensive framework for innovation in humanitarian supply chains

Discussion

The systematic review presented in this paper analyses the content of literature which details innovation in humanitarian logistics and supply chain management. This section summarises our findings. The first observation is the general paucity of literature on this topic, with only 43 articles uncovered. Thus, there are significant gaps in some topic areas, while in other cases, only a small number of articles cover a 31-year period.

One clear gap when it comes to innovation types is a lack of innovation concerning ‘position’. This is not surprising given its link to marketing but in light of the inevitable need for humanitarian supply chains to continue to develop, further consideration of position innovation would seem to be warranted. Indeed, as a general statement, current donor practice is to punish mismanagement of funds (the big stick approach) but, in future, donors might express a preference for supporting organisations which can demonstrate a high level of efficiency (the carrot approach) (Beamon & Balcik, 2008). In this respect, the management of the supply chain could play a vital role in positioning an organisation in ways that meet the donor's aspirations and creating an improved internal organisation model that delivers the desired operational improvements. Another gap found about innovation types is related to new paradigms, more precisely the lack of "inner-directed paradigms" which focuses on how the organisation perceives itself (Francis & Bessant, 2005). All new paradigms are "outer-directed" paradigms, which focus on how the supply chain interacts with its environment. Further research on how organisational identity impacts supply chain and vice versa could help understand new paradigms created internally.

A new development in the humanitarian context is the appearance of new stakeholders with the co-optation of beneficiaries as supply chain actors. Usually, beneficiaries are considered simple aid recipients. However, these new stakeholders play a role in offering the relevant capacity to complement humanitarian organisation supply chains. This, in turn, redefines the boundaries of the supply chain. Interestingly, in some senses, this brings humanitarian supply chains closer to their ‘for profit' counterparts in that it reinforces the role of the beneficiary as a pseudo-customer (with aims, aspirations, desires, etc.). Since the beneficiary is not usually the one accountable to donors, this new paradigm can potentially create a difficult trade-off for humanitarian organisations between beneficiary co-optation and ensure appropriate last mile distribution. This trade-off is exacerbated further by the fact that co-optation implies that humanitarian organisations surrender some control of the supply chain to let the beneficiary manage a specific aspect of aid flow.

An additional gap in regard to the beneficiary is the lack of articles, which highlight ways to include the beneficiary to shape innovations, which do coopt them. Indeed, Flint et al., (2005) highlight the importance of gathering customer clues to help generate relevant logistics innovations. Developing a better understanding of the role of the beneficiary in the success of supply chain innovations is thus relevant especially when considering that one article highlights the failure of innovation through procurement because of the lack of beneficiary involvement (Bornstein, et al., 2013).

There is also a gap in the absence of discussion on the role of volunteers that support and organise data entry for geographic information systems and technologies. With the advent of Web 2.0 Technologies, volunteers are now being involved in generating and analysing information during a crisis (Roche et al., 2013). This type of activity is useful for stakeholders to obtain data to support decision-making and update maps, which are relevant for logistics activities when elaborating emergency plans and scenarios, or when immediate access to geographic information is required.

When it comes to the issue of phases, the literature review reinforces the notion that supply chains act as a bridge between preparedness, response and reconstruction. Indeed, certain innovations are relevant across all phases as they contribute to integrating activities in the whole supply chain. Although the geographic reach of the supply chain is under consideration with innovation spanning multiple locations, there is a limited discussion of the role of local NGOs or local implementing partners. Furthermore, the articles reviewed take an organisation centric perspective, and this leaves a gap concerning research on innovation, which explores the interplay between regional and extra-regional actors. These regional actors and their links to extra-regional humanitarian organisations can influence the overall humanitarian supply chains and, thus, might well impact innovations and their implementation.

An additional finding in regards to both phases and geographic context is that innovations, which span a wider range of phases and locations are, unsurprisingly, more complex than innovations that focus on a single location or phase. However, such innovations offered by academia often involve the use of complex technologies, and this raises clear questions over the viability of the proposed solutions in a field setting. As a result, further research should focus on understanding the field-based implementation of complex solutions in humanitarian supply chains. Field-based research would bring additional insights and help translate proposed academic innovations into applied outcomes.

The review has also identified a range of relevant resources, which help with the development of innovations. Even though the role of the beneficiaries’ local knowledge is perceived to be important, there is a limited discussion of the role of individual staff knowledge. That said, there is some research into competencies and skills in humanitarian supply chains (Allen, et al., 2013; Kovács, et al., 2012), but this area would appear to merit further investigation. In addition to the study of staff knowledge, further research is required to understand how humanitarian organisations manage innovation cycles in order to implement and develop multiple supply chain innovations, as well as to identify the distinctions between, and the impact of, incremental or radical innovations.

Concerning the types of innovation, there is some discussion around the role of products and services in shaping the supply chain either through adding new requirements, improving its performance, or modifying information sharing activities. Process innovation also features, and the findings confirm their importance, of collaboration and coordination in the field with a good proportion of articles focusing on the processes to achieve this. Finally, paradigm innovation is also present, with most of these articles highlighting innovations that change the dynamics of supply chains either through reconfiguring it (e.g., 3D printing) or by transforming the decision-making model with the attendant implications for the beneficiary.

Concerning the external drivers of innovation, the research findings reinforce the notion that there is a lack of innovations developed specifically for humanitarian organisations by the private sector. Further research on incentives to underpin the development of solutions emanating from the private sector would appear to be warranted. However, there is also an important difference regarding the origin of the innovation, with innovations through a new process often depicted as coming from inside the organisation whereas innovations through new products as coming from external solutions. This simple dichotomy by type of innovation is limited and needs to evolve as the adoption of new products often comes with new processes through changes in policies and procedures by the organisation (Tusiime & Byrne, 2011). Future research should thus focus on the mechanisms of adoption by humanitarian organisations as well as the integration of the innovation and its impact on the organisation.

There is also a gap regarding performance measurement, and this not only applies to articles, which fail to offer a clear expected performance outcomes for the supply chain. Performance objectives, which relate to maintaining the quality of the material in the supply chain through proper sourcing and avoiding adulterated goods, are not present. Another performance issue for humanitarian supply chains, which is relevant for future innovation, is the role of sustainability and environmental responsibility.

Conclusion

This paper aims to identify gaps in the literature on innovation in humanitarian logistics and supply chain management and to develop an appropriate framework for future research through a systematic literature review. This research provides a solid baseline for future studies with the initial framework and the findings highlighting the breadth and depth of the existing gaps.

This paper also highlights both the breadth as well as the paucity of the discussion of innovations in this field. When it comes to the role of context and available resources, this paper argues for a greater emphasis on the role of the beneficiary's supply chain capacity and relevant knowledge. In addition to this new stakeholder, certain innovations emphasise the need for integration across multiple phases. Both these perspectives demonstrate how innovation can help widen and integrate the scope of humanitarian supply chain beyond their current bounds of stakeholders, location, and phase. In addition to the findings related to context and resources that shape innovation, the paper also identifies different types of innovation outcomes, which focus on performance, transformation, and failures. However, we acknowledge that further research would improve the presented framework through the study of internal knowledge management and innovation cycles in humanitarian organisations as well as through the study of complex innovation adoption in a field setting. Furthermore, a mapping of organizational theories on the framework developed in this paper could strengthen future research on humanitarian supply chain management.

Funding

No funds, grants, or other financial support was received in conducting this study.

Data availability

The data generated and analyzed in the current study are not publicly available due the fact that they constitute an excerpt of research in progress but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethical approvals

Not applicable.

Informed consent

No human subjects were used in this study.

Footnotes

An earlier and rudimentary version of this paper is available as a working paper from https://cirano.qc.ca/files/publications/2018s-03.pdf. This paper is the more advanced and current version of our working paper Altay et al., (2018).

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Nezih Altay, Email: naltay@depaul.edu.

Graham Heaslip, Email: Graham.Heaslip@gmit.ie.

Gyöngyi Kovács, Email: Gyongyi.Kovacs@hanken.fi.

Karen Spens, Email: karen.spens@bi.no.

Peter Tatham, Email: p.tatham@griffith.edu.au.

Alain Vaillancourt, Email: alainlvaillancourt@gmail.com.

References

- Abidi H, de Leeuw S, Klumpp M. The value of fourth-party logistics services in the humanitarian supply chain. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management. 2015;5(1):35–60. doi: 10.1108/JHLSCM-02-2014-0010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Abushaikha I, Schumann-Bölsche D. Mobile phones: Established technologies for innovative humanitarian logitstics concepts. Procedia Engineering. 2016;159:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2016.08.157. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alem D, Bonilla-Londono HF, Barbosa-Povoa AP, Relvas S, Ferreira D, Moreno A. Building disaster preparedness and response capacity in humanitarian supply chains using the social vulnerability Index. European Journal of Operational Research. 2021;292(1):250–275. doi: 10.1016/j.ejor.2020.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Allen MA, Kovács G, Masini A, Vaillancourt A, Van Wassenhove L. Exploring the link between the humanitarian logistician and training needs. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management. 2013;3(2):129–148. doi: 10.1108/JHLSCM-10-2012-0033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Altay, N., Heaslip, G., Kovács, G., Spens, K., Tatham, P. & Vaillancourt, A. (2018). Innovation in Humanitarian Supply Chains: A systematic review. CIRANO Working paper 2018s-03. Available from https://cirano.qc.ca/files/publications/2018s-03.pdf (Retrieved 5 June 2021).

- Altay N, Green WG., III OR/MS research in disaster operations management. European Journal of Operational Research. 2006;175(1):475–493. doi: 10.1016/j.ejor.2005.05.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anjomshoae A, Hassan A, Kunz N, Wong KY, de Leeuw S. Toward a dynamic balanced scorecard model for humanitarian relief organizations’ performance management. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management. 2017;7(2):194–218. doi: 10.1108/JHLSCM-01-2017-0001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baldini G, Oliveri F, Braun M, Seuschek H, Hess E. Securing disaster supply chains with cryptography enhanced RFID. Disaster Prevention and Management. 2012;21(1):51–70. doi: 10.1108/09653561211202700. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banomyong R, Varadejsatitwong P, Oloruntoba R. A systematic review of humanitarian operations, humanitarian logistics and humanitarian supply chain performance literature 2005 to 2016. Annals of Operations Research. 2019;283(1):71–86. doi: 10.1007/s10479-017-2549-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes J, Bradley B, Singh G, Das A. HELP: Handheld emergency logistics program for generating structured requests in stressful conditions. Procedia Engineering. 2014;78:40–48. doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2014.07.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett M. Humanitarianism transformed. Perspectives on Politics. 2005;3(4):723–740. doi: 10.1017/S1537592705050401. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beamon BM, Balcik B. Performance measurement in humanitarian relief chains. International Journal of Public Sector Management. 2008;21(1):4–25. doi: 10.1108/09513550810846087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Behl A, Dutta P. Humanitarian supply chain management: A thematic literature review and future directions of research. Annals of Operations Research. 2019;283(1):1001–1044. doi: 10.1007/s10479-018-2806-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bessant, J., Ramalingam, B., Rush, H., Marshall, N., Hoffman, K., & Gray, B. (2014). Innovation management, innovation ecosystems and humanitarian innovation: Literature review for the humanitarian innovation ecosystem research Project. UK Department for international development (DIFD). Available from https://www.alnap.org/system/files/content/resource/ files/main/humanitarian-innovation-ecosystem-research-litrev.pdf (Retrieved on 5 June 2021).

- Betts, A., & Bloom, L. (2014). Humanitarian innovation: The state of the art. New York: United Nations office for the coordination of humanitarian affairs (OCHA). Available from https://www.alnap.org/system/files/content/resource/files/main/xudfne2j.pdf (Retrieved on 5 June 2021).

- Betts, A., Bloom, L., & N. Weaver. (2015). Refugee innovation: Humanitarian innovation that starts with communities. Available from http://www.rsc.ox.ac.uk/refugeeinnovation-humanitarian-innovation-that-starts-with-communities (Retrieved on 5 June 2021).

- Biswal, A. K., Jenamani, M., & Kumar, S. K. (2018). Warehouse efficiency improvement using RFID in a humanitarian supply chain: Implications for Indian food security system. Transportation Research Part E: Logistics and Transportation Review,109, 205–224.

- Bloom, L. & A. Betts. (2013). The two worlds of humanitarian Innovation. Refugee studies centre working paper series no. 94. Oxford Humanitarian innovation project, Oxford. Available from https://www.alnap.org/help-library/the-two-worlds-of-humanitarian-innovation (Retrieved on 5 June 2021).

- Bornstein L, Lizarralde G, Gould KA, Davidson C. Framing responses to post-earthquake Haiti How representations of disasters, reconstruction and human settlements shape resilience. International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment. 2013;4(1):43–57. doi: 10.1108/17595901311298991. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breslin D, Gatrell C. Theorizing through literature reviews: The miner-prospector continuum. Organizational Research Methods. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1094428120943288. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen AY, Peña-Mora F, Ouyang Y. A collaborative GIS framework to support equipment distribution for civil engineering disaster response operations. Automation in Construction. 2011;20(1):637–648. doi: 10.1016/j.autcon.2010.12.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury S, Emelogu A, Marufuzzaman M, Nurre SG, Bian L. Drones for disaster response and relief operations: A continuous approximation model. International Journal of Production Economics. 2017;188(1):167–184. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2017.03.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Courcol JD, Invernizzi CF, Landry ZC, Minisini M, Baumgartner DA, Bonhoeffer S, Schürmann F. ARC: An open web-platform for request/supply matching for a prioritized and controlled COVID-19 response. Frontiers in Public Health. 2021;9:1–12. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.607677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delmonteil F-X, Rancourt M-È. The role of satellite technologies in relief logistics. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management. 2017;7(1):55–78. doi: 10.1108/JHLSCM-07-2016-0031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Denyer D, Tranfield D. Producing a systematic review. In: Buchanan D, Bryman A, editors. The sage handbook of organizational research methods. London: Sage Publications Ltd; 2009. pp. 671–689. [Google Scholar]

- Department for International Development. (2014). Promoting innovation and evidence-based approaches to building resilience and responding to humanitarian crises: An Overview of DFID’s approach, London: DFID. Availbale from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/378324/Humanitarian_Innovation_and_Evidence_Programme_stategy_refresh.pdf (Retrieved on 5 June 2021).

- Drucker PF. Innovation and entrepreneurship practices and principles. Harper and Row; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Dubey R, Bryde DJ, Foropon C, Graham G, Giannakis M, Mishra DB. Agility in humanitarian supply chain: An organizational information processing perspective and relational view. Annals of Operations Research. 2022;319:559–579. doi: 10.1007/s10479-020-03824-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey R, Bryde DJ, Foropon C, Tiwari M, Dwivedi Y, Schiffling S. An investigation of information alignment and collaboration as complements to supply chain agility in humanitarian supply chain. International Journal of Production Research. 2021;59(5):1586–1605. doi: 10.1080/00207543.2020.1865583. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey R, Gunasekaran A, Bryde DJ, Dwivedi YK, Papadopoulos T. Blockchain technology for enhancing swift-trust, collaboration and resilience within a humanitarian supply chain setting. International Journal of Production Research. 2020;58(11):3381–3398. doi: 10.1080/00207543.2020.1722860. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dufour É, Laporte G, Paquette J, Rancourt M-È. Logistics service network design for humanitarian response in East Africa. Omega. 2018;74:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.omega.2017.01.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- ELHRA. (2014). EHLRA Impact Strategy 2014–2016, s.l.: ELHRA. Available from https://www.elrha.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Elrha-Impact-Strategy-new-branding-1.pdf (Retrieved on 5 June 2021).

- Ergun Ö, Gui L, Heier Stamm JL, Keskinocak P, Swann J. Improving humanitarian operations through technology-enabled collaboration. Production and Operations Management. 2014;23(6):1002–1014. doi: 10.1111/poms.12107. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fink A. Conducting research literature reviews: From paper to the internet. Sage Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Flint DJ, Larsson E, Gammelgaard B. Exploring processes for customer value insights, supply chain learning and innovation: An international study. Journal of Business Logistics. 2005;29(1):257–281. doi: 10.1002/j.2158-1592.2008.tb00078.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Francis D, Bessant J. Targeting innovation and implications for capability development. Technovation. 2005;25(3):171–183. doi: 10.1016/j.technovation.2004.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Grawe SJ. Logistics innovation: A literature-based conceptual framework. The International Journal of Logistics Management. 2009;20(3):360–377. doi: 10.1108/09574090911002823. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffith DA, Boehmke B, Bradley RV, Hazen BT, Johnson AW. Embedded analytics: Improving decision support for humanitarian logistics operations. Annals of Operations Research. 2019;283(1):247–265. doi: 10.1007/s10479-017-2607-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta S, Altay N, Luo Z. Big data in humanitarian supply chain management: A review and further research directions. Annals of Operations Research. 2019;283(1):1153–1173. doi: 10.1007/s10479-017-2671-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haavisto I, Kovács G. A framework for cascading innovation upstream the humanitarian supply chain through procurement processes. Procedia Engineering. 2015;107(1):140–145. doi: 10.1016/j.proeng.2015.06.067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hadiguna RA, Kamil I, Delati A, Reed R. Implementing a web-based decision support system for disaster logistics: A case study of an evacuation location assessment for Indonesia. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction. 2014;9(1):3–47. [Google Scholar]

- Haidari LA, Brown ST, Ferguson M, Bancroft E, Spiker M, Wilcox, A.,… & Lee, B.Y. The economic and operational value of using drones to transport vaccines. Vaccine. 2016;34(1):4062–4067. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Liu G, Mai THT, Li TT. Research on the allocation of 3D printing emergency supplies in public health emergencies. Frontiers in Public Health. 2021;9:263. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2021.657276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heaslip G, Kovács G, Haavisto I. Innovations in humanitarian supply chains: The case of cash transfer programmes. Production Planning & Control. 2018;29(14):1175–1190. doi: 10.1080/09537287.2018.1542172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heaslip G, Sharif AM, Althonayan A. Employing a systems-based perspective to the identification of inter-relationships within humanitarian logistics. International Journal of Production Economics. 2012;139(2):377–392. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpe.2012.05.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen K, Strandvik T. Reframing service innovation: COVID-19 as a catalyst for imposed service innovation. Journal of Service Management. 2020;32(1):101–112. doi: 10.1108/JOSM-05-2020-0161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hirschinger M, Moser R, Schaefers T, Hartmann E. No vehicle means No Aid—A paradigm change for the humanitarian logistics business model. Thunderbird International Business Review. 2016;58(5):373–384. doi: 10.1002/tie.21745. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- James E, Taylor A. Managing humanitarian innovation: The cutting edge of aid. Practical Action Publishing; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kovács G, Falagara Sigala I. Lessons learned from humanitarian logistics to manage supply chain disruptions. Journal of Supply Chain Management. 2021;57(1):41–49. doi: 10.1111/jscm.12253. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kovács G, Spens KM. Humanitarian logistics in disaster relief operations. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management. 2007;37(2):99–114. doi: 10.1108/09600030710734820. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kovács G, Tatham P, Larson PD. What skills are needed to be a humanitarian logistician? Journal of Business Logistics. 2012;33(3):245–258. doi: 10.1111/j.2158-1592.2012.01054.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P, Singh RK. Application of Industry 4.0 technologies for effective coordination in humanitarian supply chains: A strategic approach. Annals of Operations Research. 2022;319:379–411. doi: 10.1007/s10479-020-03898-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- L'Hermitte C, Nair NKC. A blockchain-enabled framework for sharing logistics resources during emergency operations. Disasters. 2021;45(3):527–554. doi: 10.1111/disa.12436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liem A, Wang C, Wariyanti Y, Latkin CA, Hall BJ. The neglected health of international migrant workers in the COVID-19 epidemic. The Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(4):e20. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30076-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marić J, Galera-Zarco C, Opazo-Basáez M. The emergent role of digital technologies in the context of humanitarian supply chains: A systematic literature review. Annals of Operations Research. 2022;319:1003–1044. doi: 10.1007/s10479-021-04079-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mentzer JT, DeWitt W, Keebler JS, Min S, Nix NW, Smith CD, Zacharia ZG. Defining supply chain management. Journal of Business Logistics. 2001;22(2):1–25. doi: 10.1002/j.2158-1592.2001.tb00001.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Modgil S, Singh RK, Foropon C. Quality management in humanitarian operations and disaster relief management: A review and future research directions. Annals of Operations Research. 2022;319:1045–1098. doi: 10.1007/s10479-020-03695-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosterman PJ, Sanabria DE, Bilgin E, Zhang K, Zander J. Automating humanitarian missions with a heterogeneous fleet of vehicles. Annual Reviews in Control. 2014;38(1):259–270. doi: 10.1016/j.arcontrol.2014.09.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Munksgaard KB, Stentoft J, Paulraj A. Value-based supply chain innovation. Operations Management Research. 2014;7(1):50–62. doi: 10.1007/s12063-014-0092-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Narayanan A, Altay N. Ambidextrous humanitarian organizations. Annals of Operations Research. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10479-021-04370-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Natarajan KV, Swaminathan JM. Multi-treatment inventory allocation in humanitarian health settings under funding constraints. Production and Operations Management. 2017;26(6):1015–1034. doi: 10.1111/poms.12634. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Obrecht, A. (2017). Evaluating humanitarian innovation. HIF-ALNAP working paper. Available from http://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/alnap-hif-evaluatinghumanitarian-innovation-2017.pdf (Retrieved on 5 June 2021).

- OECD. (2021). COVID-19 Innovation in low and middle income countries: Lessons for development cooperation. OECD Development Policy Papers No. 39. Available from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/development/covid-19-innovation-in-low-and-middle-income-countries_19e81026-en (Retrieved on 5 June 2021).

- Özdamar L, Ertem MA. Models, solutions and enabling technologies in humanitarian logistics. European Journal of Operational Research. 2015;244(1):55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ejor.2014.11.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Őzgüven EE, Őzbay K. A secure and efficient inventory management system for disasters. Transportation Research Part C. 2013;29(1):171–196. doi: 10.1016/j.trc.2011.08.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Őzgüven EE, Őzbay K. An RFID-based inventory management framework for emergency relief operations. Transportation Research Part C. 2015;57(1):166–187. doi: 10.1016/j.trc.2015.06.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paré G, Trudel MC, Jaana M, Kitsiou S. Synthesizing information systems knowledge: A typology of literature reviews. Information & Management. 2015;52(2):183–199. doi: 10.1016/j.im.2014.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Patil A, Shardeo V, Dwivedi A, Madaan J. An integrated approach to model the blockchain implementation barriers in humanitarian supply chain. Journal of Global Operations and Strategic Sourcing. 2021;14(1):81–103. doi: 10.1108/JGOSS-07-2020-0042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pedrosa ADM, Blazevic V, Jasmand C. Logistics innovation development: A micro-level perspective. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management. 2015;45(4):313–332. doi: 10.1108/IJPDLM-12-2014-0289. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Post C, Sarala R, Gatrell C, Prescott JE. Advancing theory with review articles. Journal of Management Studies. 2020;57(2):351–376. doi: 10.1111/joms.12549. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Queiroz MM, Ivanov D, Dolgui A, Fosso Wamba S. Impacts of epidemic outbreaks on supply chains: Mapping a research agenda amid the COVID-19 pandemic through a structured literature review. Annals of Operations Research. 2022;319:1159–1196. doi: 10.1007/s10479-020-03685-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramalingam, B., Rush, H., Bessant, J., Marshall, N., Gray, B., Hoffman, K., Bayley, S., Gray, I. & K. Warren. (2015). Strengthening the humanitarian innovation ecosystem: Final report. Centre for research in innovation management at the university of brighton. Available from https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08977e5274a31e00000c6/ Humanitarian_ Innovation_Ecosystem_Research_Project_FINAL_report_with_recommendations.pdf (Retrieved on 5 June 2021).

- Roche S, Propeck-Zimmermann E, Boris M. GeoWeb and crisis management: Issues and perspectives of volunteered geographic information. GeoJournal. 2013;78(1):21–40. doi: 10.1007/s10708-011-9423-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez-Espíndola O, Chowdhury S, Beltagui A, Albores P. The potential of emergent disruptive technologies for humanitarian supply chains: The integration of blockchain, Artificial Intelligence and 3D printing. International Journal of Production Research. 2020;58(15):4610–4630. doi: 10.1080/00207543.2020.1761565. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, E. M. (1995). Diffusion of innovations: Modifications of a model for telecommunications. In: Stoetzer, M. W., Mahler, A. (eds) Die diffusion von innovationen in der telekommunikation. Schriftenreihe des Wissenschaftlichen Instituts für Kommunikationsdienste, vol 17. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. 10.1007/978-3-642-79868-9_2

- Rousseau DM, Manning J, Denyer D. Evidence in management and organizational science: Assembling the field’s full weight of scientific knowledge through syntheses. Academy of Management Annals. 2008;2(1):475–515. doi: 10.5465/19416520802211651. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sandvik KB. Now is the time to deliver: Looking for humanitarian innovation’s theory of change. Journal of International Humanitarian Action. 2017;2(1):1–11. doi: 10.1186/s41018-017-0023-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Santos ALR, Linda WS, Goosens R, Brezet H. Systemic barriers and enablers in humanitarian technology transfer. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management. 2016;6(1):47–71. doi: 10.1108/JHLSCM-12-2014-0038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schniederjans DG, Őzpolat K, Chen Y. Humanitarian supply chain use of cloud computing. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal. 2016;21(5):569–588. doi: 10.1108/SCM-01-2016-0024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Serrato-Garcia MA, Mora-Vargas J, Murillo RT. Multi objective optimization for humanitarian logistics operations through the use of mobile technologies. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management. 2016;6(3):399–418. doi: 10.1108/JHLSCM-01-2015-0002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seuring S, Gold S. Conducting content-analysis based literature reviews in supply chain management. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal. 2012;17(5):544–555. doi: 10.1108/13598541211258609. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard A, Tatham P, Fisher R, Gapp R. Humanitarian logistics: Enhancing the engagement of local populations. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management. 2013;3(1):22–36. doi: 10.1108/20426741311328493. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sodhi MS, Tang CS. Buttressing supply chains against floods in Asia for humanitarian relief and economic recovery. Production and Operations Management. 2014;23(6):938–950. doi: 10.1111/poms.12111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Su S-II, Gammelgaard B, Yang S-L. Logistics innovation process revisited: Insights from a hospital case study. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management. 2011;41(6):577–600. doi: 10.1108/09600031111147826. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tatham P, Ball C, Wu Y, Diplas P. Long-endurance remotely piloted aircraft systems (LE-RPAS) support for humanitarian logistic operations: The current position and the proposed way ahead. Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management. 2017;7(1):2–15. doi: 10.1108/JHLSCM-05-2016-0018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tatham P, Loy J, Peretti U. Three dimensional printing—A key tool for the humanitarian logistician? Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management. 2015;5(2):188–208. doi: 10.1108/JHLSCM-01-2014-0006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]