Abstract

Background:

Cardiac arrest (CA) is a common reason for admission to the cardiac intensive care unit (CICU), though the relative burden of morbidity, mortality, and resource use between admissions with in-hospital (IH) and out-of-hospital (OH) CA is unknown. We compared characteristics, care patterns, and outcomes of admissions to contemporary CICUs after IHCA or OHCA.

Methods:

The Critical Care Cardiology Trials Network is a multicenter network of tertiary CICUs in the US and Canada. Participating centers contributed data from consecutive admissions during 2-month annual snapshots from 2017 to 2021. We analyzed characteristics and outcomes of admissions by IHCA vs OHCA.

Results:

We analyzed 2,075 admissions across 29 centers (50.3% IHCA, 49.7% OHCA). Admissions with IHCA were older (median 66 vs 62 years), more commonly had coronary disease (38.3% vs 29.7%), atrial fibrillation (26.7% vs 15.6%), and heart failure (36.3% vs 22.1%), and were less commonly comatose on CICU arrival (34.2% vs 71.7%), p<0.001 for all. IHCA admissions had lower lactate (median 4.3 vs 5.9) but greater utilization of invasive hemodynamics (34.3% vs 23.6%), mechanical circulatory support (28.4% vs 16.8%), and renal replacement therapy (15.5% vs 9.4%); p<0.001 for all. Comatose IHCA patients underwent targeted temperature management less frequently than OHCA patients (63.3% vs 84.9%, p<0.001). IHCA admissions had lower unadjusted CICU (30.8% vs 39.0%, p<0.001) and in-hospital mortality (36.1% vs 44.1%, p<0.001).

Conclusion:

Despite a greater burden of comorbidities, CICU admissions after IHCA have lower lactate, greater invasive therapy utilization, and lower crude mortality than admissions after OHCA.

INTRODUCTION

Cardiac arrest (CA) accounts for 6 to 9% of admissions to contemporary cardiac intensive care units (CICUs) [1, 2]. Despite advances in care that have improved outcomes in patients with CA, associated morbidity and mortality remain high [2–7]. While several U.S. and international registries have been commissioned to describe characteristics and outcomes of patients with out-of-hospital CA (OHCA) [3, 7, 8] and/or in-hospital CA (IHCA) [5, 8], these registries typically focus on describing the pre-hospitalization course or the totality of medical care received during hospitalization. Data published from the Swedish SWECRIT registry describe patients admitted to ICUs after cardiac arrest [9], however detailed information regarding ICU therapies were not available and similar analyses from North American registries focused on CICU care have not been published. Describing in detail this facet of care represents a substantial unmet need in keeping with the fifth and sixth links of the American Heart Association’s “chain of survival” for adults after cardiac arrest (“post cardiac arrest care” and “recovery,” respectively) [10].

The Critical Care Cardiology Trials Network (CCCTN) is a multi-center network of CICUs in North America that prospectively collects data on patients admitted to CICUs. We aimed to describe the characteristics, care patterns, and outcomes of CA survivors presenting to contemporary CICU’s in the CCCTN, comparing admissions after IHCA to those after OHCA.

METHODS

Critical Care Cardiology Trials Network Registry

The CCCTN is an investigator-initiated, voluntary, collaborative network of dedicated American Heart Association Level 1 CICUs in North America [2, 11]. The contemporary American Heart Association (AHA) Level 1 CICU in the United States is typically a closed-model ICU, staffed by cardiologists, focused on providing comprehensive critical care to patients either with acute cardiovascular conditions warranting critical care or patients with chronic significant cardiac problems who present with other non-cardiac critical illness [12]. Details of the inception, conduct and methods of the CCCTN registry have been reported [2]. Scientific oversight of CCCTN is conducted by its academic executive and steering committees and coordinated by the TIMI Study Group at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts. All participating investigators and study coordinators undergo central CCCTN training on data collection and the central coordinating center reviews all cases for data consistency. Participating centers contributed annual 2-month data “snapshots” of consecutive medical admissions to the CICU from 2017 through 2021. The 2 consecutive months selected each year to serve as the data “snapshot” were chosen by the site’s principal investigator. Patient triage to the CICU (as opposed to another ICU or a non-ICU service) was determined by criteria specific to each individual participating center. However, most AHA Level 1 CICUs are likely to care for the majority of shockable cardiac arrests and those with non-shockable cardiac arrest not clearly explained by a non-cardiovascular primary problem. The CCCTN registry protocol and waiver of informed consent were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the data coordinating center (Brigham and Women’s Hospital) and each participating center. No protected health information is collected in the CCCTN registry.

Cardiac Arrest Study Population

The CCCTN registry collects information regarding patient characteristics, initial diagnosis, indications for CICU admission, clinical CICU course, and hospital outcomes as well as the presence of CA or shock at presentation. Shock is defined as a systolic blood pressure <90mmHg for ≥30 minutes (or the need for vasopressors or inotropes) and laboratory or physical exam evidence of end-organ hypoperfusion. For this study, we analyzed admissions to the CICU presenting with CA. Data were collected for the initial CA, whether in the field, at an outside hospital, or at the study center, including data on initial rhythm, neurologic status (i.e. comatose state) after return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), and initiation of targeted temperature management (TTM). Comatose state is defined as a patient meeting local neurologic criteria for TTM at the time of initial assessment. Cases in which a first CA was after admission to the CICU were excluded from this analysis. Admissions were stratified by IHCA vs OHCA. OHCA was defined as the initial CA occurring prior to hospital arrival. IHCA was defined as the initial CA occurring after hospital arrival at either the participating center or a transferring hospital and before admission to the CICU. Data described included patient demographics, comorbidities, CA rhythm (shockable vs non-shockable), CICU resource utilization (i.e. therapies utilized at any point during CICU course), in-hospital mortality, and discharge disposition. Admission labs within the first 24 hours of admission to the CICU were captured.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were compared using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test and categorical variables were compared using either the chi-square or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. All tests were 2-sided and a p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. No adjustments were made for multiple comparisons.

Multivariable logistic regression was performed to assess resource utilization (mechanical ventilation, right heart catheterization, mechanical circulatory support (MCS), renal replacement therapy, coronary angiography/percutaneous coronary intervention) with IHCA vs. OHCA adjusting for age, sex, sequential organ failure assessment (SOFA) score and comatose state on presentation. Multivariable logistic regression was also performed to evaluate the association between IHCA vs. OHCA with CICU and in-hospital mortality adjusting for relevant factors of clinical interest including age, sex, SOFA score, shockable rhythm, and comatose state on presentation. All analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics and Admission Diagnoses

Among 29 CCCTN registry centers, 11.6% (2075/17852) of admissions had CA as part of the presenting syndrome to the CICU. Of these, 50.3% (1044/2075) were after IHCA and 49.7% (1031/2075) after OHCA. Baseline characteristics are described in Table 1. Compared to admissions with OHCA, those with IHCA were older (median age 66 [56–75] vs 62 [53–72] years; p<0.001), more commonly female (36.2% vs 30.6%; p=0.007) and more commonly had coronary artery disease (38.3% vs 29.7%), severe valvular disease (12.8% vs 4.7%), heart failure (HF) (36.3% vs 22.1%), atrial fibrillation (26.7% vs 15.6%), chronic kidney disease (24.6% vs 13.4%), and pulmonary hypertension (5.8% vs 1.4%) (p<0.001 for all). Among primary cardiac problems as potential precipitants, acute coronary syndromes (ACS) (477/2075) and HF (113/2075) were the most common, with primary ventricular arrhythmias identified as the principal diagnosis in 23.6% (490/2075) admissions.

Table 1:

Patient Characteristics and Admission Parameters.

| All CA (%) (N=2075) | IHCA (%) N=1044 | OHCA (%) N=1031 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, years (IQR) | 64.0 (55–73) | 66 (56–75) | 62 (53–72) | <0.001 |

| Female Sex | 694 (33.4%) | 378 (36.2%) | 316 (30.6%) | 0.007 |

| Race | 0.48 | |||

| Black | 361 (17.4%) | 170 (16.3%) | 191 (18.5%) | ----------- |

| White | 1258 (60.6%) | 639 (61.2%) | 619 (60.0%) | ----------- |

| Asian | 85 (4.1%) | 47 (4.5%) | 38 (3.7%) | ----------- |

| Other/Unknown | 371 (17.9%) | 188 (18.0%) | 183 (17.7%) | ----------- |

| Ethnicity | 0.20 | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 121 (5.8%) | 70 (6.7%) | 51 (5.0%) | ----------- |

| Not Hispanic or Latino | 1649 (79.6%) | 826 (79.3%) | 823 (79.9%) | ----------- |

| Unknown | 302 (14.6%) | 146 (14.0%) | 156 (15.1%) | ----------- |

| BMI, median (IQR), kg/m2 | 28.3 (24.4–32.9) | 28.4 (24.5–32.7) | 28.1 (24.4–33.2) | 0.92 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Ever Smoker | 981 (59.0%) | 506 (56.9%) | 475 (61.4%) | 0.057 |

| Diabetes | 709 (34.2%) | 392 (37.5%) | 317 (30.7%) | 0.001 |

| HTN | 1264 (60.9%) | 678 (64.9%) | 586 (56.8%) | <0.001 |

| CAD | 706 (34.0%) | 400 (38.3%) | 306 (29.7%) | <0.001 |

| Cerebrovascular Disease | 192 (9.3%) | 115 (11.0%) | 77 (7.5%) | 0.005 |

| PAD | 191 (9.2%) | 109 (10.4%) | 82 (8.0%) | 0.050 |

| Active Cancer | 130 (6.3%) | 89 (8.5%) | 41 (4.0%) | <0.001 |

| Atrial Fibrillation | 440 (21.2%) | 279 (26.7%) | 161 (15.6%) | <0.001 |

| Ventricular Arrhythmia | 118 (5.7%) | 66 (6.3%) | 52 (5.0%) | 0.21 |

| Severe Valvular Disease | 182 (8.8%) | 134 (12.8%) | 48 (4.7%) | <0.001 |

| Heart Failure | 607 (29.3%) | 379 (36.3%) | 228 (22.1%) | <0.001 |

| LVEF* | 0.72 | |||

| <40% | 356/575 (61.9%) | 230/368 (62.5%) | 126/207 (60.9%) | ----------- |

| 40–50% | 88/575 (15.3%) | 53/368 (14.4%) | 35/207 (16.9%) | ----------- |

| >50% | 131/575 22.8%) | 85/368 (23.1%) | 46/207 (22.2%) | ----------- |

| Pulmonary HTN (severe) | 75 (3.6%) | 61 (5.8%) | 14 (1.4%) | <0.001 |

| Pulmonary Disease | 298 (14.4%) | 164 (15.7%) | 134 (13.0%) | 0.078 |

| Congenital Heart Disease | 31 (1.5%) | 20 (1.9%) | 11 (1.1%) | 0.111 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 395 (19.0%) | 257 (24.6%) | 138 (13.4%) | <0.001 |

| On Dialysis | 131 (6.3%) | 87 (8.3%) | 44 (4.3%) | 0.69 |

| Liver Disease | 49 (2.4%) | 39 (3.7%) | 10 (1.0%) | <0.001 |

= in subjects with a history of HF and known LVEF prior the index hospitalization;

BMI = body mass index; CA = cardiac arrest; CAD = coronary artery disease; CM = cardiomyopathy; HTN = Hypertension; IHCA= in-hospital-arrest; IQR = interquartile range (25th-75th); LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; OHCA = out-hospital-arrest; PAD = peripheral artery disease

Labs within the first 24 hours of CICU admission are shown in Table 2. Compared with admissions with OHCA, admissions with IHCA had lower median lactate [4.3 (IQR 2.1–9.0) vs 5.9 (IQR 2.9–9.6), p<0.001], ALT or AST ≥150 (20.0% vs 24.0%, p=0.003) and less often had a SOFA score of ≥8 (53.5% vs 60.1%, p=0.002).

Table 2:

Admission laboratory data

| Median Lab Value (IQR)* | All CA (%) (N=2075) | IHCA (%) N=1044 | OHCA (%) N=1031 | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactate, mmol/L | 5.0 (2.4–9.4) | 4.3 (2.1–9.0) | 5.9 (2.9–9.6) | <0.001 |

| Lactate ≥ 4 mmol/L | 1059/1788 (59.2%) | 472/867 (54.4%) | 587/921 (63.7%) | <0.001 |

| Arterial pH | 7.3 (7.2–7.3) | 7.3 (7.2–7.4) | 7.3 (7.2–7.3) | 0.030 |

| Arterial pH < 7.20 | 310/969 (32.0%) | 151/485 (31.1%) | 159/484 (32.9%) | 0.567 |

| Total Bilirubin, mg/dL | 0.8 (0.5–1.4) | 0.9 (0.6–1.5) | 0.8 (0.5–1.2) | <0.001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.6 (1.1–2.9) | 1.7 (1.1–3.1) | 1.6 (1.1–2.7) | 0.032 |

| ALT, mg/dL | 93 (41–295) | 75 (32–276) | 120 (54–307) | <0.001 |

| AST, mg/dL | 140 (56–455) | 111 (44–478) | 166 (84–453) | <0.001 |

| ALT ≥ 150 and/or AST ≥ 150, n (%) | 456/911 (50.1%) | 209/462 (45.2%) | 247/449 (55.0%) | 0.003 |

| SOFA score | 8 (5–12) | 8 (4–12) | 9 (5–12) | 0.065 |

| SOFA score ≥ 8 | 1179/2075 (56.8%) | 559/1044 (53.5%) | 620/1031 (60.1%) | 0.002 |

Median lab value (IQR) is reported unless otherwise specified.

ALT = alanine aminotransferase; AST = aspartate aminotransferase; CA = cardiac arrest; IHCA= in-hospital-arrest; IQR = interquartile range (25th-75th); OHCA = out-hospital-arrest; SOFA = Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

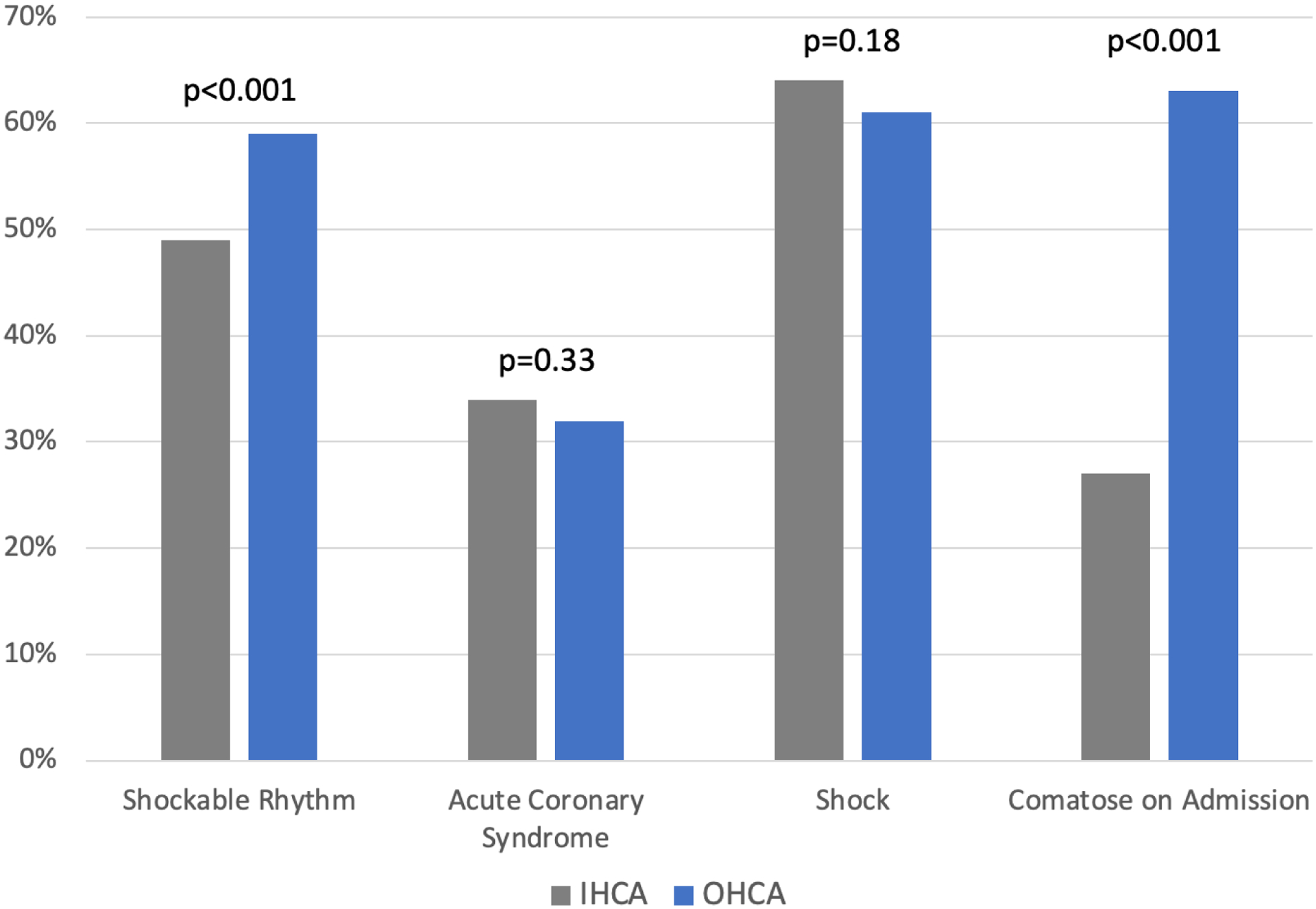

Key CICU admission characteristics are shown in Figure 1. A total of 54.2% (1125/2075) of admissions had a shockable rhythm, 49.3% (515/1044) after IHCA and 59.2% (610/1031) after OHCA (p<0.001). A total of 44.9% (932/2075) admissions were comatose on initial assessment, 26.9% (281/1044) after IHCA (p<0.001) and 63.1% (651/1031) after OHCA (p<0.001). Rates of ACS on presentation were similar between admissions with IHCA and OHCA (33.8% vs 31.8%; p=0.33) as were the proportion presenting with shock (63.7% vs 60.8%, p=0.18).

Figure 1: Key CICU admission characteristics for patients with cardiac arrest.

CICU = cardiac intensive care unit; IHCA = in-hospital cardiac arrest; OHCA = out-of-hospital cardiac arrest

CICU Resource Utilization

CICU resource utilization patterns are shown in Figure 2. Compared to admissions with OHCA, admissions with IHCA had a lower crude rate of utilization of mechanical ventilation (71.6% vs 82.3%, p<0.001) but higher rates of MCS (28.4% vs 16.8%, p<0.001), renal replacement therapy (15.5% vs 9.4%, p<0.001), and right heart catheterization (34.3% vs 23.6%, p<0.001). After adjustment for age, sex, SOFA score, and comatose state on presentation, the difference in utilization of mechanical ventilation was no longer statistically significant (p=0.92), however MCS, renal replacement therapy, and right heart catheterization remained more common among admissions with IHCA (p<0.001 for all); Supplemental Table S1. After adjustment, admissions with IHCA were more likely to be treated with IV vasoactive therapies (vasopressor, inotrope, or vasodilator) than admissions with OHCA (odds ratio 1.48, 95% confidence interval 1.17–1.87; p=0.001). In the overall CA population, 44.1% (916/2075) of admissions underwent coronary angiography and/or percutaneous coronary intervention during the CICU admission. After adjustment, admissions with IHCA less commonly underwent coronary angiography and/or percutaneous coronary intervention than those with OHCA (p=0.038).

Figure 2: CICU resource utilization among patients with cardiac arrest.

CICU = cardiac intensive care unit; IHCA = in-hospital cardiac arrest; OHCA = out-of-hospital cardiac arrest; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention

Of admissions to the CICU who were comatose on initial assessment, a significantly smaller number with IHCA than OHCA underwent targeted temperature management (TTM) (63.3% (178/281) vs 84.9% (553/651); p<0.001). Target temperatures for patients treated with TTM are described in Supplement Table S2.

Length of Stay, Discharge Disposition, and Mortality

Among all-comers, the median length of CICU stay was 3.2 days (IQR 1.3–6.8 days) after IHCA and 3.8 days (IQR 1.8–7.2 days) after OHCA (p=0.003), whereas the median length of hospital stay was similar between those with IHCA and OHCA (6.9 days [IQR 2.8–15.6 days] vs 6.9 days [IQR 3.0–12.9 days], respectively; p=0.76). Among those who survived to hospital discharge, the median length of hospital stay was 9.9 days (5.1–18.4 days) after IHCA and 10.7 days (6.4–18.7 days) after OHCA (p=0.041).

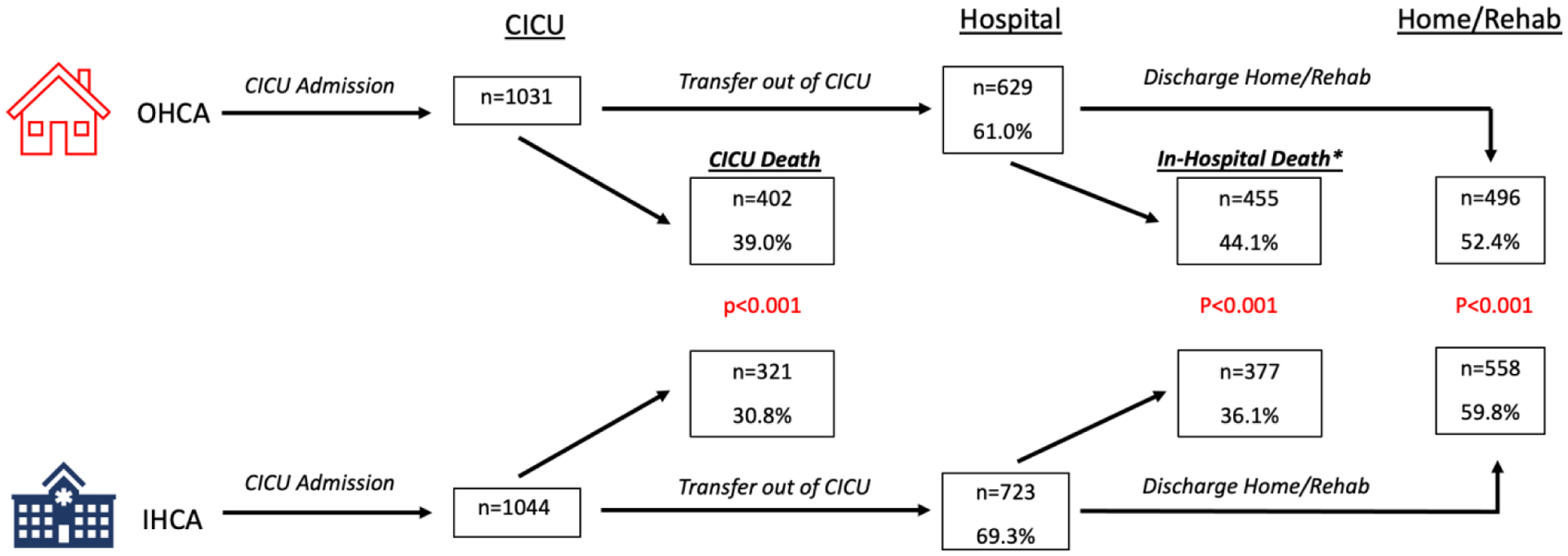

Discharge disposition and in-hospital mortality are described in Figures 3 and 4, respectively. Discharge disposition data were missing for n=11 admissions (n=7 with IHCA, n=4 with OHCA). CICU mortality for the overall study population was 34.8% (723/2075) and was lower in the IHCA group than in the OHCA group (30.8% vs 39.0%, p<0.001). In-hospital mortality (inclusive of CICU mortality) for the overall study population was 40.1% (832/2075) and was lower in the IHCA group than in the OHCA group (36.1% vs 44.1%, p<0.001). Discharge home or to rehab occurred in 51.1% (1054/2064) of the overall study population and was significantly higher in the IHCA group than in the OHCA group (53.7% vs 48.4%; p<0.001). After accounting for age, sex, SOFA score, shockable rhythm, and comatose state on presentation, there was no difference in CICU mortality or in-hospital mortality between admissions with IHCA and admissions with OHCA (p=0.52 and p=0.96, respectively); Supplemental Table S3.

Figure 3: Outcomes of patients presenting to the CICU after cardiac arrest.

Crude rates are presented. Discharge disposition data missing in n=11 patients. *In-hospital deaths are inclusive of CICU deaths; Possible outcomes include death, discharge home/rehab, inpatient facility (not shown), or hospice (not shown). For n=496 with OHCA who were discharge home or to rehab, n=379 were discharged home and n=117 were discharged to rehab. For n=558 with IHCA who were discharge home or to rehab, n=415 were discharged home and n=143 were discharged to rehab.

CICU = cardiac intensive care unit; IHCA = in-hospital-cardiac arrest; OHCA = out-hospital-cardiac arrest

Figure 4: In-Hospital Mortality by OHCA and IHCA.

OHCA = out-hospital-cardiac arrest; IHCA = in-hospital-cardiac arrest

DISCUSSION

We used data from the CCCTN registry to describe admissions to contemporary CICUs after CA. The proportions of admissions for IHCA and OHCA were similar in our study population. Important differences in demographics and comorbidities between the IHCA and OHCA populations were identified, including a greater burden of cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular comorbidities in the IHCA population. Admissions after IHCA had lower lactate, transaminases, SOFA scores, and lower unadjusted utilization of mechanical ventilation but higher utilization of other ICU therapies such as MCS and renal replacement therapy. Among admissions who were comatose after CA, those with IHCA underwent TTM less frequently than their OHCA counterparts. Admissions with IHCA had lower unadjusted rates of CICU and in-hospital mortality than patients with OHCA, which appears to be explained by a lesser severity of organ injury after ROSC, and the initial neurologic status on presentation.

This analysis is the first to describe the CA population from the perspective of survivors admitted to the CICU, thus is the first to describe in detail the critical care needs of this population. A recent analysis from the Swedish “SWECRIT” registry described characteristics and outcomes of 799 patients with either IHCA (n=245) or OHCA (n=554) admitted to 1 of 4 general ICUs [9]. Other existing registries have devoted greater focus to OHCA [6, 7, 13, 14], though there is an increasing number describing patients with IHCA [4, 5, 14]. Most of these focus on epidemiology and outcomes of CA without collecting details of diagnostics and ICU therapies provided during the post-resuscitation CICU phase of care. Our analysis offers novel insight into the CICU care provided to this population.

A novel finding of our analysis is that half of admissions in our study population were patients with IHCA. This finding may partly be explained by the design of our registry, as only patients who survive to CICU admission are included in the registry. Other large CA registries either exclude IHCA entirely [3], exclude OHCA entirely [14, 15], or describe a much smaller proportion of patients with IHCA (28%) presumably due to inclusion of OHCA patients who die prior to ICU admission [16]. Although IHCA admissions in this analysis had more comorbidities than OHCA admissions, IHCA admissions may presumably have a shorter time to initiation of resuscitation efforts and possibly more effective cardiopulmonary resuscitation than their OHCA counterparts, as a contributor to the less profound end-organ injury evident in the IHCA group. Because our cohort is restricted to survivors to CICU admission, comparison to studies of all patients with IHCA reveals understandable differences. A prior study of all inpatients with IHCA revealed a rate of ROSC as low as 35% [17]. As the majority of studies of CA have focused on OHCA, our findings highlight the fact that IHCA is a clinically important group that warrants dedicated study, particularly regarding ICU therapies such as TTM.

Several notable findings from our analysis pertain to the IHCA population presenting to CICUs. The higher prevalence of both cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular comorbidities among IHCA vs. OHCA admissions is in keeping with prior reports, such as a large prospective Danish registry showing a significantly higher prevalence of HF, ischemic heart disease, atrial arrhythmias, and renal disease in patients with IHCA compared to those with OHCA [16]. Data from the SWECRIT registry yielded similar findings [9]. Admissions with IHCA in our study population had a higher prevalence of pre-existing HF (36.3%) than IHCA patients from the Danish registry (18%) and patients from the US-based Get with the Guidelines-Resuscitation registry (22.7%) [15]. This finding may be attributable to the fact that most CCCTN participating centers are large referral institutions [2]. Another key finding is that 49.3% of admissions with IHCA in our study population had a shockable rhythm, whereas shockable rhythm was present in only 19% and 20.7% of patients from the Danish [16] and US [15] registries, respectively. While it is likely that this finding is attributable to our study population including only survivors to CICU admission, these data are relevant to understanding the population of patients treated in contemporary CICUs.

Shock was common on CICU presentation, present in >60% of the overall study population with similar prevalence in the OHCA and IHCA populations. Despite this, IHCA patients were more often treated with ICU therapies focused on treating shock, such as IV vasoactive therapies and MCS, even after adjustment. The etiology of shock in a post-arrest population is highly variable and includes predisposing factors that provoked CA (such as acute HF and ACS) as well as sequelae from CA and resuscitation efforts (such as ischemia-reperfusion injury, myocardial injury, and vasoplegia). Differences in utilization of ICU therapies for treatment of shock (i.e., MCS) is a provocative finding, but may be attributable to unmeasured confounding between groups, including patient characteristics not captured in the registry, such as frailty, decision-making regarding life-sustaining therapies, and behavioral and socioeconomic factors that may have influenced whether a given patient was a candidate for advanced therapies. Our findings however highlight the marked overlap between CA and shock, further underscoring the importance of questions surrounding shock treatment strategies in the CA population.

Among comatose patients in our study population, TTM utilization was more common after OHCA compared to IHCA. Of the major randomized clinical trials to date evaluating TTM after CA, all but two trials [18, 19] have excluded IHCA patients. Current guidelines however recommend the use of TTM in appropriately selected patients with either OHCA or IHCA regardless of initial rhythm [20–22], albeit based on low-quality evidence [23]. The higher percentage of comatose OHCA patients in our study population likely reflects a longer time prior to ROSC in OHCA patients, thus a higher likelihood of suffering a neurological insult [24, 25]. The discrepancy in TTM utilization between comatose OHCA and IHCA survivors however remains notable. This observation may reflect a greater tendency to defer TTM after IHCA given the generally higher burden of comorbidities and lack of high-quality evidence. Further study is warranted to investigate clinician decision-making regarding TTM.

In-hospital mortality in our study population was high (37.4%), although lower than previously described in patients who experience IHCA from the US National Inpatient Sample [3], OHCA including those who die in the field [6, 26], and IHCA from a large US registry [14]. The higher overall survival after CA in our cohort is in part due to the design of our study which focused on survivors to CICU admission. Patients with IHCA from the study population had a lower unadjusted CICU and in-hospital mortality than those with OHCA, as well as a shorter median CICU length of stay. After adjustment for clinically relevant variables, there was no statistically significant difference in CICU or in-hospital mortality between groups. These findings suggest that the lower unadjusted rate of death among admissions with IHCA is attributable to the lesser severity of organ injury after ROSC, and the initial neurologic status on presentation.

Limitations

The CCCTN registry collects observational data on only medical CICU admissions and thus does not evaluate CA patients admitted to other ICUs. Our study population is limited to those who survived to CICU admission and is not intended to capture the entire spectrum of patients with OHCA or IHCA. Although our report does not reflect the entire CA population, it does reflect the population that is cared for by CICU clinicians and is therefore clinically relevant. Data are collected by chart review by site investigators and are subject to the possibility of misclassification. Only in-hospital mortality outcomes are collected for the CCCTN registry. Data describing time from CA to resuscitation, duration of resuscitation, medications used during resuscitation, presumed CA etiology, neurologic outcomes and post-discharge outcomes are not collected. Additional details regarding the arrest and resuscitation, indeed, might have helped to provide mechanistic insight into observed differences. Data describing treatment limitation decisions that may have impacted mortality [27] were not collected. Finally, comparative data presented are subject to potential confounding and should be interpreted with caution.

CONCLUSION

Approximately half of CICU admissions with CA have experienced IHCA. There are important differences in patient characteristics and ICU therapies provided to those with OHCA and IHCA. Despite a greater burden of cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular comorbidities, CICU admissions after IHCA have lower crude mortality than admissions after OHCA, possibly due to lesser severity of end-organ injury.

Supplementary Material

Funding

No outside funding was obtained for the purposes of this analysis. Individual author disclosures are listed separately.

Conflict of Interest Statement

Dr. Solomon receives research support from the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center intramural research funds.

Dr. Teuteberg receives consulting feeds from Abbott, Abiomed, CareDx, Cytokinetics, Medtronic, Paragonix, and Takeda.

All other authors report no conflicts of interest relevant to the submitted material.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Credit Author Statement

AP Carnicelli: Conceptualization, Methodology, data curation, Writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

R Keane: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

KM Brown: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

DB Loriaux: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

P Kendsersky: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

CL Alviar: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

K Arps: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

DD Berg: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

EA Bohula: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

JA Burke: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

JA Dixson: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

DA Gerber: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

M Goldfarb: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

CB Granger: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, supervision, writing – reviewing/editing

J Guo: methodology, data curation, investigation, software, visualization, writing – reviewing/editing

RW Harrison: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

M Kontos: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

PR Lawler: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

PE Miller: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

J Nativi-Nicolau: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

LK Newby: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, supervision, writing – reviewing/editing

L Racharla: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

RO Roswell: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

KS Shah: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

SS Sinha: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

MA Solomon: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

J Teuteberg: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

G Wong: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, writing – reviewing/editing

S van Diepen: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, supervision, writing – reviewing/editing

JN Katz: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, supervision, writing – reviewing/editing

DA Morrow: conceptualization, methodology, data curation, writing – original draft, visualization, investigation, supervision, writing – reviewing/editing

Data Sharing Statement

Parties interested in collaboration are encouraged to contact the corresponding author.

References

- [1].Miller PE, Chouairi F, Thomas A, Kunitomo Y, Aslam F, Canavan ME, et al. Transition From an Open to Closed Staffing Model in the Cardiac Intensive Care Unit Improves Clinical Outcomes. J Am Heart Assoc. 2021;10:e018182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Bohula EA, Katz JN, van Diepen S, Alviar CL, Baird-Zars VM, Park JG, et al. Demographics, Care Patterns, and Outcomes of Patients Admitted to Cardiac Intensive Care Units: The Critical Care Cardiology Trials Network Prospective North American Multicenter Registry of Cardiac Critical Illness. JAMA Cardiol. 2019;4:928–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Fugate JE, Brinjikji W, Mandrekar JN, Cloft HJ, White RD, Wijdicks EF, et al. Post-cardiac arrest mortality is declining: a study of the US National Inpatient Sample 2001 to 2009. Circulation. 2012;126:546–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Radeschi G, Mina A, Berta G, Fassiola A, Roasio A, Urso F, et al. Incidence and outcome of in-hospital cardiac arrest in Italy: a multicentre observational study in the Piedmont Region. Resuscitation. 2017;119:48–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Nolan JP, Soar J, Smith GB, Gwinnutt C, Parrott F, Power S, et al. Incidence and outcome of in-hospital cardiac arrest in the United Kingdom National Cardiac Arrest Audit. Resuscitation. 2014;85:987–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Beck B, Bray J, Cameron P, Smith K, Walker T, Grantham H, et al. Regional variation in the characteristics, incidence and outcomes of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in Australia and New Zealand: Results from the Aus-ROC Epistry. Resuscitation. 2018;126:49–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Grasner JT, Lefering R, Koster RW, Masterson S, Bottiger BW, Herlitz J, et al. EuReCa ONE-27 Nations, ONE Europe, ONE Registry: A prospective one month analysis of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest outcomes in 27 countries in Europe. Resuscitation. 2016;105:188–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Allan K, Dorian P, Lin S, Investigators CS. Developing a Pan-Canadian Registry of Sudden Cardiac Arrest: Challenges and Opportunities. CJC Open. 2019;1:53–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Andersson A, Arctaedius I, Cronberg T, Levin H, Nielsen N, Friberg H, et al. In-hospital versus out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: Characteristics and outcomes in patients admitted to intensive care after return of spontaneous circulation. Resuscitation. 2022;176:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Merchant RM, Topjian AA, Panchal AR, Cheng A, Aziz K, Berg KM, et al. Part 1: Executive Summary: 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2020;142:S337–S57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Metkus TS, Baird-Zars VM, Alfonso CE, Alviar CL, Barnett CF, Barsness GW, et al. Critical Care Cardiology Trials Network (CCCTN): a cohort profile. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2022;8:703–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Morrow DA, Fang JC, Fintel DJ, Granger CB, Katz JN, Kushner FG, et al. Evolution of critical care cardiology: transformation of the cardiovascular intensive care unit and the emerging need for new medical staffing and training models: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2012;126:1408–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Ong ME, Shin SD, Tanaka H, Ma MH, Khruekarnchana P, Hisamuddin N, et al. Pan-Asian Resuscitation Outcomes Study (PAROS): rationale, methodology, and implementation. Acad Emerg Med. 2011;18:890–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Peberdy MA, Kaye W, Ornato JP, Larkin GL, Nadkarni V, Mancini ME, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation of adults in the hospital: a report of 14720 cardiac arrests from the National Registry of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2003;58:297–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Girotra S, Nallamothu BK, Spertus JA, Li Y, Krumholz HM, Chan PS, et al. Trends in survival after in-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1912–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Hoybye M, Stankovic N, Holmberg M, Christensen HC, Granfeldt A, Andersen LW. In-Hospital vs. Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest: Patient Characteristics and Survival. Resuscitation. 2021;158:157–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Schwartz BC, Jayaraman D, Warshawsky PJ. Survival from in-hospital cardiac arrest on the Internal Medicine clinical teaching unit. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:117–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Lascarrou JB, Merdji H, Le Gouge A, Colin G, Grillet G, Girardie P, et al. Targeted Temperature Management for Cardiac Arrest with Nonshockable Rhythm. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2327–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Pittl U, Schratter A, Desch S, Diosteanu R, Lehmann D, Demmin K, et al. Invasive versus non-invasive cooling after in- and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a randomized trial. Clin Res Cardiol. 2013;102:607–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Panchal AR, Bartos JA, Cabanas JG, Donnino MW, Drennan IR, Hirsch KG, et al. Part 3: Adult Basic and Advanced Life Support: 2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2020;142:S366–S468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Sinha SS, Sukul D, Lazarus JJ, Polavarapu V, Chan PS, Neumar RW, et al. Identifying Important Gaps in Randomized Controlled Trials of Adult Cardiac Arrest Treatments: A Systematic Review of the Published Literature. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9:749–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Nolan JP, Soar J, Cariou A, Cronberg T, Moulaert VR, Deakin CD, et al. European Resuscitation Council and European Society of Intensive Care Medicine Guidelines for Post-resuscitation Care 2015: Section 5 of the European Resuscitation Council Guidelines for Resuscitation 2015. Resuscitation. 2015;95:202–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Donnino MW, Andersen LW, Berg KM, Reynolds JC, Nolan JP, Morley PT, et al. Temperature Management After Cardiac Arrest: An Advisory Statement by the Advanced Life Support Task Force of the International Liaison Committee on Resuscitation and the American Heart Association Emergency Cardiovascular Care Committee and the Council on Cardiopulmonary, Critical Care, Perioperative and Resuscitation. Resuscitation. 2016;98:97–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Kim WY, Ahn S, Hong JS, Cho GC, Seo DW, Jeung KW, et al. The impact of downtime on neurologic intact survival in patients with targeted temperature management after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: National multicenter cohort study. Resuscitation. 2016;105:203–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Donnino MW, Salciccioli JD, Dejam A, Giberson T, Giberson B, Cristia C, et al. APACHE II scoring to predict outcome in post-cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2013;84:651–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zive D, Koprowicz K, Schmidt T, Stiell I, Sears G, Van Ottingham L, et al. Variation in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest resuscitation and transport practices in the Resuscitation Outcomes Consortium: ROC Epistry-Cardiac Arrest. Resuscitation. 2011;82:277–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Elmer J, Torres C, Aufderheide TP, Austin MA, Callaway CW, Golan E, et al. Association of early withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy for perceived neurological prognosis with mortality after cardiac arrest. Resuscitation. 2016;102:127–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Parties interested in collaboration are encouraged to contact the corresponding author.