Abstract

Background

Lung cancer screening programs provide an opportunity to support people who smoke to quit, but the most appropriate model for delivery remains to be determined. Immediate face-to-face smoking cessation support for people undergoing screening can increase quit rates, but it is not known whether remote delivery of immediate smoking cessation counselling and pharmacotherapy in this context also is effective.

Research Question

Does an immediate telephone smoking cessation intervention increase quit rates compared with usual care among a population enrolled in a targeted lung health check (TLHC)?

Study Design and Methods

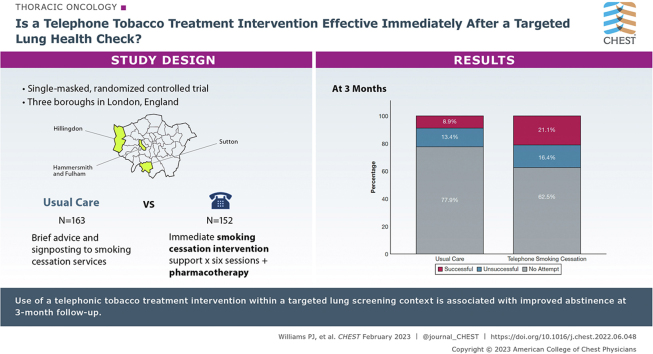

In a single-masked randomized controlled trial, people 55 to 75 years of age who smoke and attended a TLHC were allocated by day of attendance to receive either immediate telephone smoking cessation intervention (TSI) support (starting immediately and lasting for 6 weeks) with appropriate pharmacotherapy or usual care (UC; very brief advice to quit and signposting to smoking cessation services). The primary outcome was self-reported 7-day point prevalence smoking abstinence at 3 months. Differences between groups were assessed using logistic regression.

Results

Three hundred fifteen people taking part in the screening program who reported current smoking with a mean ± SD age of 63 ± 5.4 years, 48% of whom were women, were randomized to TSI (n = 152) or UC (n = 163). The two groups were well matched at baseline. Self-reported quit rates were higher in the intervention arm, 21.1% vs 8.9% (OR, 2.83; 95% CI, 1.44-5.61; P = .002). Controlling for participant demographics, neither baseline smoking characteristics nor the discovery of abnormalities on low-dose CT imaging modified the effect of the intervention.

Interpretation

Immediate provision of an intensive telephone-based smoking cessation intervention including pharmacotherapy, delivered within a targeted lung screening context, is associated with increased smoking abstinence at 3 months.

Trial Registry

ISRCTN registry; No.: ISRCTN12455871; URL: www.IRSCN.com

Key Words: behavior change, lung cancer, randomized controlled trial, screening, smoking cessation

Abbrevations: GCSE, General Certificate of Secondary Education; LDCT, low-dose CT; NHS, National Health Service; QuLIT, Quit Smoking Lung Health Intervention Trial; TLHC, targeted lung health check; TSI, telephone smoking cessation intervention; UC, usual care; VBA, very brief advice

Graphical Abstract

Take-home Points.

Study Question: Does an immediate telephone smoking cessation intervention (TSI) increase quit rates compared with usual care (UC) among a population enrolled in a targeted lung health check?

Results: Self-reported quit rates were higher in the intervention arm compared with the UC arm: TSI, 21.1% vs UC, 8.9%.

Interpretation: Immediate provision of an intensive TSI, delivered within a targeted lung screening context, is associated with increased smoking abstinence at 3 months.

Targeted screening programs using low-dose CT (LDCT) imaging have been proposed as a solution to reduce the impact of lung cancer by diagnosing it at an earlier, potentially curable, stage. Large randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that this approach can reduce mortality resulting from lung cancer by between 20% and 60%,1,2 and LDCT scan screening is now recommended by the United States Preventative Services Taskforce.3 In 2019, the National Health Service (NHS) England launched targeted lung health check (TLHC) pilot projects at various sites across the United Kingdom to investigate the feasibility and effectiveness of LDCT scan screening within the United Kingdom.4 More recently, the National Screening Committee began a public consultation regarding a national rollout of TLHC across the United Kingdom.5

Tobacco smoking is among the largest causes of morbidity and mortality, and thus, smoking cessation is a key aspect of the prevention and treatment both of respiratory disease and many conditions occurring beyond the lungs.6 Lung cancer screening eligibility criteria targets high-risk individuals who smoke, who differ in certain ways from the general smoking population, being older, often with multiple comorbidities and a longer smoking history, and having greater tobacco dependence.1,7 LDCT scan screening trials have demonstrated higher quit rates in intervention than control arms, and thus, the screening process can be considered to be a so-called teachable moment for smoking cessation.8,9 Making the best use of this is crucial, and the provision of evidence-based smoking cessation within screening programs has been advocated.10 The effectiveness of different approaches remains a key question for research to establish which specific approaches should be used to maximize the value and impact of the lung health check.11, 12, 13, 14

In the Quit Smoking Lung Intervention Trial (QuLIT) initial phase (QuLIT 1), we demonstrated a significant increase in 3-month quit rate (29.9% vs 11%) for TLHC participants randomized to receive immediate face-to-face cessation support and pharmacotherapy compared with usual care (UC). The latter consisted of very brief advice (VBA) to quit and signposting to smoking cessation support.15 Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, face-to-face support was suspended in March 2020 and the study was modified to investigate, in a discrete second phase (QuLIT 2), whether remote delivery of the smoking cessation intervention also was effective compared with UC.

Study Design and Methods

Study Design and Participants

QuLIT 2 was a single-masked, randomized controlled trial comparing the effectiveness of an immediate, intensive telephone smoking cessation intervention (TSI) compared with VBA to quit and signposting delivered in the context of a TLHC. People living in the London boroughs of Sutton, Hillingdon, and Hammersmith and Fulham who were 55 to 75 years of age with a recorded history of smoking were invited for a TLHC assessment, as described previously.15 All current smokers who took part in the TLHC were included in the study (current smokers were defined as any person self-reporting smoking tobacco, including cigarettes, pipes, and cigars, at the time of the TLHC). All participants who smoked were included in the study population, regardless of readiness or motivation to quit.

The TLHC Setting

The Healthy Lung Project is an investigational lung cancer screening pilot delivered by the Royal Brompton Hospital, supported by RM Partners, the West London Cancer Alliance, and the NHS funded through the National Cancer Transformation Fund. Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, in 2021, all initial prescan TLHC appointments were changed to a remote telephone delivery model. They included an in-depth discussion of participants’ current or historical smoking behavior, medical and occupational history, and familial cancer history. If participants were deemed at high risk of lung cancer according to the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Trial or Liverpool Lung Project screening risk models,16,17 they were invited for an LDCT scan.

Ethics

The study was approved by the South Central—Oxford C Research Ethics Committee and the Health Research Authority (Reference: 18/SC/0236). The requirement for individual consent was waived by the ethics committee because obtaining this would itself have been an intervention and would have influenced outcomes in the control group. The initial QuLIT 1 and the amended study reported here, QuLIT 2, were registered prospectively online (ISRCTN12455871).

Randomization

Participants in the trial attended the TLHC appointment between April 1 and June 31, 2021. Half of the days during that period were allocated by random number generation as TSI days and half as UC days. Appointments for the TLHC were allocated by an administrator who was unaware of to which study arm the days had been allocated.

Interventions

TSI

Participants in the TSI group received a telephone call from the smoking cessation practitioner after the initial TLHC appointment. To capitalize on this so-called teachable moment, the smoking cessation practitioners attempted to call the participants on the same day that they underwent the TLHC. If they were unable to reach participants, they would call the them the next day. Participants were offered six sessions of telephone behavioral counselling support in addition to pharmacotherapy (varenicline or nicotine replacement therapies).

Counselling sessions were based on the National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training and Kick-It programs18,19 and followed a structure of six sessions conducted once weekly. The timing of each phone visit was arranged between the participant and counselling staff. The initial session included a discussion of participants’ smoking history, involving an assessment of dependence, information about available pharmacotherapy, including medication history to ensure that no interactions or contraindications occurred, and information about the program. The session would finish with a summary of the pharmacotherapy chosen and a commitment from the participant to engage with the program. Before a varenicline prescription was made, the nurses discussed the patients’ medical and drug history with a medical doctor (K. E. J. P. or N. S. H.), who then prescribed the medication or suggested an alternative. All pharmacotherapies were prescribed by the trial team and were despatched via the hospital’s pharmacy. We sent the chosen pharmacotherapy to participants directly by mail immediately after the first session, typically arriving within 48 h.

The second session included preparing the participant to set a quit date, ensuring that they knew how to use or take their chosen pharmacotherapy, and a discussion around typical withdrawal symptoms. Sessions 3 through 6 were delivered after the set quit date and included support with withdrawal symptoms, pharmacotherapy reviews, commitment to the “not a puff” rule for participants who had quit and further behavioral support for participants who relapsed or were unable to commit to the quit date. All sessions were delivered over the phone by two specialist research nurses who had undergone the National Centre for Smoking Cessation Training and KickIT training programs.18,19 People in the intervention arm also were signposted to the London Stop Smoking portal (https://london.stopsmokingportal.com/), local smoking cessation services, or both if they did not wish to engage with, or withdrew from, the smoking cessation program.

UC

Those attending on UC days received VBA to quit (“Stopping smoking is the most important thing that you can do to improve your health now and reduce the risk of health problems in the future.”) as outlined by the National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training.20 They were directed to the London Stop Smoking online portal, which provides information to smokers about how to engage with local stop smoking services, as well as a a quit smoking telephone support line. Participants living in the London borough of Sutton were advised to contact their general practitioner for stop smoking support because no specialist smoking cessation support was available in this borough. VBA to quit and signposting were delivered by the specialist respiratory nurses who administered the TLHC clinics and occurred at the end of the appointment.

Follow-up

Three months after the TLHC appointment, participants were called by a researcher (K. E. J. P. or P. J. W.) who was masked to study allocation. The content of the call was structured on a set of short, predefined questions. This included the primary outcome measure, which was self-reported 7-day point prevalence smoking abstinence, with a successful quit defined as no smoking or other tobacco product use within the last 7 days. Data relating to secondary outcome measures also were collected, including quit attempts made and pharmacotherapy used. Quit attempts were defined as an attempt to stop smoking that lasted for 1 day and are presented as the number of individuals who made at least one quit attempt during the previous 3-month period. If participants did not pick up on the first call, two more calls were made at different times of the day. If the participant did not pick up on the third call, a voicemail was left requesting a call back. In the event that the participant did not call back within the week (or had no voicemail facility) they were classed as lost to follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

The primary outcome was self-reported 7-day point prevalence abstinence from smoking 3 months after randomization compared between groups. The sample size was calculated using the findings of two studies: the Evaluating Adverse Events in a Global Smoking Cessation Study (EAGLES) trial,21 which found a 38% quit rate in the pharmacology arm, and the United Kingdom Lung Cancer Screening Study,8 which found a 14% quit rate in the arm undergoing CT scan screening. Based on these rates, a superiority study (1:1 randomization) with 90% power at a 5% significance level required 136 participants (calculator at Sealed Envelope: https://www.sealedenvelope.com/power/binary-superiority/). To improve the power of exploratory analyses comparing different subgroups (eg, those with or without positive CT scan results), we intended to recruit as many participants from the clinical screening program as possible. Simple logistic regression analysis (unadjusted) was used to assess primary and secondary end points. We ran two models in the adjusted logistic regression analysis: model 1 adjusted for sex, age, and CT scan result, and model 2 adjusted for sex, age, and baseline demographics (age, sex, and smoking characteristics); intervention, age, and sex were retained in both models. As a sensitivity analysis, we assumed that all individuals lost to follow-up were still smoking. Analysis was based on intention to treat, and a P value of < .05 was taken as statistically significant. All data were analyzed using SPSS version 27 software (SPSS Institute).

Results

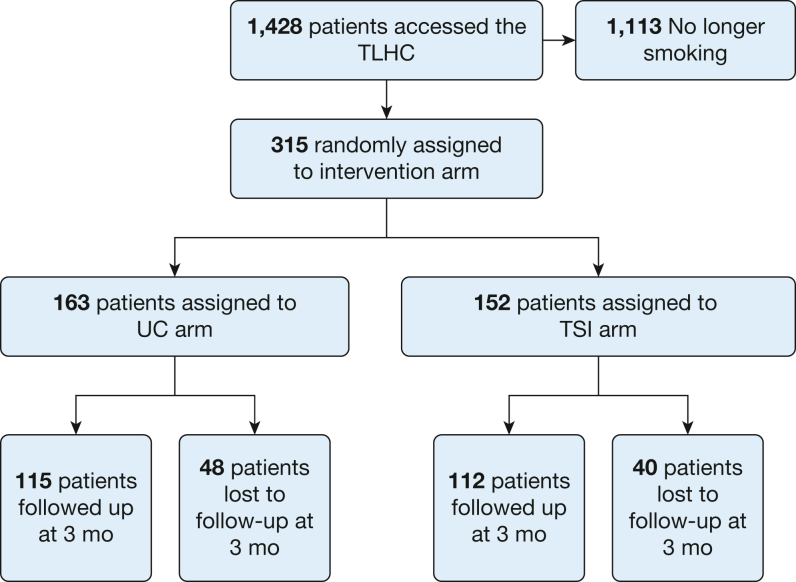

Baseline participant characteristics at the time of enrolment were well matched (Table 1).22 A total of 315 individuals who smoke underwent a TLHC during the study period and were enrolled into the study: 163 attended on days allocated to UC and 152 attended on days allocated to TSI. Figure 1 represents the flow of patients through the trial.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic Characteristics

| Characteristic | UC (n =163) | Intervention (n = 152) |

|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 63.0 ± 5.4 | 61.3 ± 4.8 |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 84 (51.5) | 68 (44.7) |

| Male | 79 (48.5) | 84 (55.3) |

| Ethnicitya | ||

| White | 138 (84.6) | 131 (86) |

| Black | 9 (5.6) | 6 (4.0) |

| Asian | 12 (7.3) | 9 (6.0) |

| Other | 3 (1.9) | 5 (3.3) |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.7) |

| Education | ||

| < GCSE | 64 (39.3) | 59 (38.9) |

| GCSE | 63 (38.7) | 49 (32.2) |

| A level | 23 (14.2) | 17 (11.1) |

| Some university | 2 (1.3) | 7 (4.6) |

| Degree plus postgraduate work | 11 (6.5) | 20 (17.2) |

| IMD quintileb | ||

| 1 (most deprived) | 9 (5.5) | 15 (9.9) |

| 2 | 19 (11.7) | 19 (12.5) |

| 3 | 40 (24.5) | 26 (17.1) |

| 4 | 65 (39.9) | 52 (34.2) |

| 5 (least deprived) | 30 (18.4) | 40 (26.3) |

| Baseline smoking characteristics | ||

| Age started smoking, y | 18.1 ± 6.3 | 18.0 ± 5.9 |

| Average No. of cigarettes per day | 12.6 ± 7.9 | 12.5 ± 7.7 |

| Duration of smoking, y | 42.5 ± 9.5 | 40.9 ± 9.0 |

| CT scan results | ||

| No scan neededc | 59 (36.2) | 52 (34.2) |

| Negatived | 55 (33.7) | 60 (39.4) |

| Positivee | 49 (30.1) | 40 (26.4) |

Data are presented as No. (%) or mean ± SD. GCSE = General Certificate of Secondary Education; IMD = index of multiple deprivation; UC = usual care.

Groupings as recommended by the Prostate, Lung Colorectal and Ovarian Screening Trial.

Index: quantile 1 = most deprived areas in England; quantile 5 = least deprived areas in England.22

Participant did not meet CT scan criteria according to the Prostate, Lung Colorectal and Ovarian Screening Trial and Liverpool Lung Project risk models.16,17

Results were clear, no evidence of nodules or incidental findings.

Nodules requiring 3-, 6-, or 12-month follow-up scan, suspicious lesions, nodular consolidation, or incidental findings.

Figure 1.

Diagram demonstrating the flow of patients through the trial. TLHC = targeted lung health check; TSI = telephone smoking cessation intervention; UC = usual care.

Engagement With Smoking Cessation

Of the 152 participants attending on days randomized to TSI, 80 participants (52%) declined to engage with the smoking cessation support, explicitly asking not to be contacted by our cessation nurses. Of the remaining 72 participants in the TSI arm, 57 of 72 participants (79%) were enrolled into the full cessation program and 16 of 72 participants (21%) dropped out after the initial session. Reasons given for dropping out were being unable to commit to the “not a puff” rule or not being ready to commit to the program (committing to the “not a puff” rule and the program are essential components of the smoking cessation set out by KickIT and the National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training,18,19,23 which our intervention was based on). The average number of sessions completed by the participants was 5.1, with 61% of participants completing the full six sessions. The average length of time for the telephone sessions was 27 min.

Outcomes

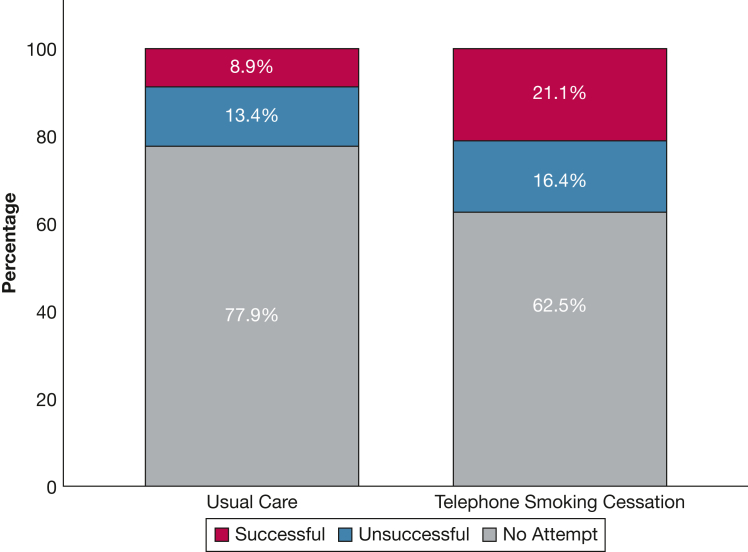

Three-month follow-up data were available for 227 of 315 participants (72%; UC group, 115/163 participants [70%]; TSI group, 112/152 participants [73%]). Quit rates were higher in the intervention arm: 21.1% vs 8.9% (OR, 2.83; 95% CI, 1.44-5.60; P = .002) (Table 2). The numbers reporting quit attempts, including successful and unsuccessful attempts, also was higher in the TSI group (57/152 participants [37.5%] vs 36/163 participants [22.0%]; OR, 2.11; 95% CI, 1.29-3.47; P = .003) (Table 2, Fig 2). We explored whether undergoing the CT scan itself influenced quit rates among the study arms. Within the UC arm, undergoing a CT scan did not influence quit rates: UC without CT scan, 4/59 participants [6.7%] vs UC with CT scan, 10/104 participants [9.5%]; OR, 0.68; 95% CI, 0.20-2.28; P = .53). This was similar within the TSI study arm: among TSI participants who did not undergo a CT scan, 14 of 52 participants (26.9%) quit compared with 18 of 100 participants (18%) among TSI participants who underwent a CT scan (OR, 1.67; 95% CI, 0.75-3.72; P = .23).

Table 2.

Smoking Cessation and Quit Attempts at 3 Mo

| Variable | TSI (n = 152) | UC (n = 163) | OR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seven-d smoking abstinence | . . . | |||

| Yes | 32 (21) | 14 (8.9) | 2.83 (1.44-5.61) | 002 |

| No | 120 (79) | 149 (91.1) | . . . | . . . |

| Individuals reporting a quit attempta | . . . | |||

| Yes | 57 (37.5) | 36 (22.0) | 2.11 (1.29-3.47) | 003 |

| No | 95 (62.5) | 127 (78.0) | . . . | . . . |

| Pharmacotherapy aids used to support quit attempts | . . . | |||

| Varenicline | 16 (28.0) | 1 (2.7) | 13.65 (1.72-108.24) | 01 |

| Single-item NRT | 12 (21.0) | 2 (5.5) | 4.53 (0.95- 21.61) | 05 |

| Dual-item NRT | 21 (37.0) | 3 (3.8) | 6.41 (1.75-23.51) | 005 |

| E-cigarette | 8 (14.0) | 11 (30.5) | 0.37 (0.13-1.04) | 05 |

| None | 0 (0) | 19 (57.5) | 0.06 (0.0-0.27) | 004 |

Data are presented as No. (%), unless otherwise indicated. NRT = nicotine replacement therapy; TSI = telephone smoking cessation intervention; UC = usual care.

Includes both successful and unsuccessful quit attempts.

Figure 2.

Bar graph showing smoking cessation in the intervention and control arms

The use of all types of pharmacotherapies (varenicline, single-item nicotine replacement therapy, and dual-item nicotine replacement therapy) during quit attempts was more common in the TSI group (OR, 20.90; 95% CI, 6.98-62.55; P ≤ .001) (Table 2). By contrast, participants in the UC group were more likely to report use of e-cigarettes to aid quit attempts (TSI, 14.0% vs UC, 30.5%). Of note, in the UC arm only three of 36 participants attempting to quit accessed behavioral support via their local service (two quit successfully) and one of 36 participants used the NHS stop smoking smartphone app.

Results from the two logistic regression models are displayed in Table 3; data from participants who did not undergo a CT scan were excluded from model 2. Personal demographic features (sex, age), CT scan results (positive or negative), and smoking characteristics (average number of cigarettes per day, age started smoking, and number of years smoking) had no effect on quit rates at 3 months within the cohort.

Table 3.

Logistic Regression Models of Covariates Associated With Smoking Abstinence at 3 Mo

| Variable | Model 1: Sex, Age, and CT Scan Results (n = 315) | Model 2: Sex, Age, and Baseline Smoking Characteristics (n = 315) |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention | 2.80 (1.42-5.53) | 2.62 (1.32-5.24) |

| Sex (men vs women) | 1.00 (0.581-1.44) | 1.00 (0.57-1.43) |

| Age (continuous) | 1.00 (0.90-0.98) | 1.01 (0.90-1.01) |

| CT scan results | ||

| Negative | 1.46 (0.77-2.72) | ... |

| Positivea | 0.990 (0.50-1.61) | ... |

| Average No. of cigarettes/d | ... | 0.995 (0.97-1.04) |

| Age started smoking | ... | 1.02 (0.95-1.07) |

| No. of years smoking | ... | 0.977 (0.94-1.03) |

Data presented as OR (95% CI). Boldface values indicate P < .05.

Nodules requiring 3-, 6-, or 12-month follow-up scan, suspicious lesions, nodular consolidation, or incidental findings.

Discussion

The main finding of this randomized controlled trial is that the provision of smoking cessation support including counselling support and pharmacotherapy, delivered by telephone immediately after attendance at a TLHC, significantly increased 7-day point prevalence smoking abstinence at 3 months compared with UC of VBA to quit and signposting to smoking cessation services.

Significance of Findings

Our results support the hypothesis that the immediate provision of remote, intensive smoking cessation support for high-risk people who smoke undergoing TLHC is more effective (21.1% vs 8.9%) for increasing quit rates within this cohort than UC. These findings extend those from QuLIT 1, which found that immediate face-to-face support can increase quit rates compared with UC (29.2% vs 11%) in the context of TLHC.15 Comparing the two trials, the quit rates in the UC groups in both studies numerically were similar, whereas quit rates in the face-to-face intervention group were higher. The number of quit attempts also was higher in the intervention group (TSI, 37.5% vs UC, 22.0%) and similar between both the QuLIT 1 and 2 interventions (QuLIT 1, 35.3%). However, the two approaches were not compared directly, so future studies will be required to confirm which approach generally is more effective.

Several trials, including the initial QuLIT 1 study, have investigated the impact of smoking cessation support within lung cancer screening pathways with mixed results, limited by factors including statistical power and the nature, intensity, duration, and immediacy of intervention.11,12,14,15,24 The 3-month quit rate of 21.1% observed in the QuLIT 2 intervention arm is comparable with that of other studies in which quit rates ranged from 10% to 25%. Interestingly, the two studies that reported lower interventional quit rates than our current study conducted cessation remotely (telephone and online) and did not offer any pharmacotherapy.11,24

Other studies also have investigated which factors may be associated with successful smoking cessation within TLHC settings. Tremblay et al13 found that those who reported a history of cancer, smoked at work, and consumed alcohol once per week or more were more likely still to be smoking at 12 months.13 In the NELSON screening trial, individuals who smoke with higher educational attainment and higher motivation to quit were more likely to have quit at the 2-year follow-up.25 By contrast, we found no associations between participant characteristics and successful smoking abstinence, although this may be the result of a lack of statistical power. The effect of undergoing a CT scan vs not undergoing a CT scan as part of a TLHC did not alter quit rates significantly within this population (with CT, 13.7% vs without CT, 16.2%). These data do support the offer of smoking cessation support to everyone taking part in TLHC, not only those whose risk score means that they qualify for low-dose CT imaging.

Pharmacologic cessation aids were accessed by people trying to quit in both study arms; however, participants in the TSI group were around 20 times more likely to use pharmacologic aids including nicotine replacement therapy and varenicline. This is unsurprising because the combination of pharmacologic aids and behavioral support were the main components of the intervention. Yet, the pharmacotherapy use within the UC arm was remarkably low: only 6 of 36 participants (16%) who attempted to quit used pharmacotherapy and only three participants in the UC arm accessed cessation support from their local services, despite advice and signposting to do so. E-cigarette use to support quit attempts was significantly higher in the UC arm of the study (TSI, 14.0% vs UC, 30.5%), indicating that in the absence of organized support and pharmacotherapy, individuals who smoke are more likely to adopt this approach. Data exist to support the effectiveness of e-cigarettes in the context of lung cancer screening, with significantly higher 3-month abstinence with both nicotine e-cigarettes (25.4%) and nicotine-free e-cigarettes (23.4%) compared with a control (10.34%).26 These findings, coupled with the recent announcement from the UK’s Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency that it will support the medicinal licensing of e-cigarettes for smoking cessation,27 suggest that providers of cessation interventions within a screening context in the United Kingdom should be prepared to support people using this form of nicotine replacement.

Our results have the potential to inform future service delivery of TLHC programs through optimization of smoking cessation support delivery in this population. Both QuLIT 1 and 2 suggest improved quit rates with early intervention delivery, either face to face or remotely, compared with UC. Although face-to-face approaches may be more effective for those able to attend in person, remotely delivered interventions could expand access in general, particularly for people living in remote and low-income areas, and are of particular interest during the COVID-19 pandemic, when limitations have been placed on face-to-face activities. Our results also suggest that providing pharmacotherapy within the smoking cessation support is an important component of the intervention, contributing to successful abstinence. It is likely that a combination of delivery options and pharmacotherapy will be most appropriate for a population with varying needs and preferences.

We recognize the multiple organizational, personnel, and financial barriers that lung screening clinics face when considering imbedding smoking cessation into their clinics. A 2016 qualitative study of health-care professionals providing lung cancer screening in the United States reported that health-care providers did not have enough time to devote to smoking cessation discussions.28 Given these constraints, particularly time and personnel, recommendations to use specific smoking cessation advisors to work exclusively within these screening clinics may be appropriate. These specialist advisors could provide tailored in-person and telephone support, including both behavioral counselling and pharmacotherapy provision, all of which will eliminate workload constraints from clinical teams, in addition to increasing the cost-effectiveness of the interventions.29

Strengths and Limitations

We conducted the study in the context of a clinical lung cancer service, without deviation from the standard pathway or change in patient experience, apart from the provision of the smoking cessation support on TSI days, which increases the generalizability of the findings. The inclusion of all current smokers enrolled in the Healthy Lung Project, regardless of their current readiness or motivation to quit, allows us to assess the impact of the approach within the entire screened population, not just those immediately motivated to stop smoking.

Certain limitations and considerations should be discussed. First, we used self-reported 7-day point smoking prevalence as the primary end point, rather than biochemically confirmed quit rates, to keep study costs and participant burden low. Although point prevalence self-reported data are a known valid abstinence measure within clinical trials,30 they often are used in other cessation screening trials as an outcome measure.8,12,13 The use of exhaled carbon monoxide monitoring would increase the rigor of the study outcome. Second, the ethnicity of the sample population is predominantly White (85%), which is higher than the proportion of people identifying as White in our catchment areas, Hammersmith and Fulham (58%),31 Hillingdon (41.7%),32 and Sutton (61.1%),33 so some caution is needed when extrapolating our results. Third, the loss to follow-up observed within the population (28%) was slightly higher than anticipated, although it was similar to that in other studies.11,26 Importantly, sensitivity analysis, taking the cautious assumption that all those lost to follow-up continued to smoke, did not alter the study findings.

Interpretation

Immediate, intensive telephone-based smoking cessation support with pharmacotherapy, delivered within a TLHC setting increased the 3-month quit rate. This suggests that this approach is appropriate and effective for this population and that access to specialist smoking cessation support should be embedded within the delivery of lung cancer screening.

Funding/Support

This work was supported by RM Partners, West London Cancer Alliance, hosted by The Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust.

Financial/Nonfinancial Disclosures

The authors have reported to CHEST the following: N. S. H. is chair of Action on Smoking and Health and medical director of Asthma+Lung UK; A. A. L. is a trustee of Action on Smoking and Health. None declared (P. J. W., K. E. J. P., N. K. G., D. F., S. B., E. C. B., A. D., S. V. K., J. A., J. D., M. C., K. M.).

Acknowledgments

Author contributions: N. S. H., E. C. B., S. V. K., J. A., J. D., M. C., and K. M. designed the study. N. K. G. and D. F. delivered the smoking cessation intervention, supported by P. J. W. P. J. W. and K. E. J. P. conducted follow-up calls. P. J. W., K. E. J. P., and A. A. L. conducted data analysis. P. J. W. produced the first draft, to which all authors contributed. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript. N. S. H. is the guarantor of the study and affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Role of sponsors: The sponsor had no role in the design of the study, the collection and analysis of the data, or the preparation of the manuscript.

Data sharing: Anonymized research data will be shared with third parties via request to the senior author (N. S. H.).

References

- 1.National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Aberle D.R., Adams A.M., et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Koning H.J., van der Aalst C.M., de Jong P.A., et al. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with volume CT screening in a randomized trial. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(6):503–513. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.United States Preventative Services Taskforce Lung cancer: screening 2021. United States Preventative Services Taskforce website. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/lung-cancer-screening

- 4.NHS England News NHS to rollout lung cancer scanning trucks across the country 2019. National Health Service website. https://www.england.nhs.uk/2019/02/lung-trucks/

- 5.United Kingdom National Screening Committee Adult screening programme. Lung cancer 2022. United Kingdom National Screening Committee website. https://view-health-screening-recommendations.service.gov.uk/lung-cancer/

- 6.World Health Organization Tobacco 2021. World Health Organization website. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco

- 7.Kathuria H., Detterbeck F.C., Fathi J.T., et al. Stakeholder research priorities for smoking cessation interventions within lung cancer screening programs. An official American Thoracic Society research statement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196(9):1202–1212. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201709-1858ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brain K., Carter B., Lifford K.J., et al. Impact of low-dose CT screening on smoking cessation among high-risk participants in the UK Lung Cancer Screening Trial. Thorax. 2017;72(10):912–918. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-209690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ashraf H., Tønnesen P., Pedersen J.H., Dirksen A., Thorsen H., Døssing M. Effect of CT screening on smoking habits at 1-year follow-up in the Danish Lung Cancer Screening Trial (DLCST) Thorax. 2009;64(5):388–392. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.102475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joseph A.M., Rothman A.J., Almirall D., et al. Lung cancer screening and smoking cessation clinical trials. SCALE (Smoking Cessation Within the Context of Lung Cancer Screening) collaboration. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018;197(2):172–182. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201705-0909CI. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark M.M., Cox L.S., Jett J.R., et al. Effectiveness of smoking cessation self-help materials in a lung cancer screening population. Lung Cancer. 2004;44(1):13–21. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Taylor K.L., Hagerman C.J., Luta G., et al. Preliminary evaluation of a telephone-based smoking cessation intervention in the lung cancer screening setting: a randomized clinical trial. Lung Cancer. 2017;108:242–246. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2017.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tremblay A., Taghizadeh N., Huang J., et al. A randomized controlled study of integrated smoking cessation in a lung cancer screening program. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(9):1528–1537. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2019.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marshall H.M., Courtney D.A., Passmore L.H., et al. Brief tailored smoking cessation counseling in a lung cancer screening population is feasible: a pilot randomized controlled trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016;18(7):1665–1669. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntw010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buttery S.C., Williams P., Mweseli R., et al. Immediate smoking cessation support versus usual care in smokers attending a targeted lung health check: the QuLIT trial. BMJ Open Respir Res. 2022;9(1):e001030. doi: 10.1136/bmjresp-2021-001030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cassidy A., Myles J.P., van Tongeren M., et al. The LLP risk model: an individual risk prediction model for lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(2):270–276. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ten Haaf K., Jeon J., Tammemägi M.C., et al. Risk prediction models for selection of lung cancer screening candidates: a retrospective validation study. PLoS Med. 2017;14(4) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kick-It Healthcare professionals 2018. Kick-It website. https://kick-it.org.uk/healthcare-professionals/

- 19.National Center for Smoking Cessation and Training Online training 2021. National Center for Smoking Cessation and Training website. https://elearning.ncsct.co.uk/

- 20.National Center for Smoking Cessation and Training. Very brief advice 2021. Accessed June 17, 2022. https://www.ncsct.co.uk/publication_very-brief-advice.php

- 21.Anthenelli R.M., Benowitz N.L., West R., et al. Neuropsychiatric safety and efficacy of varenicline, bupropion, and nicotine patch in smokers with and without psychiatric disorders (EAGLES): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Lancet. 2016;387(10037):2507–2520. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)30272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government. The English indices of deprivation 2019 (IoD 2019). Government Document 2019 20/09/2021

- 23.Kick-It Healthcare professionals 2018. Kick-It website. https://kick-it.org.uk/healthcare-professionals/

- 24.Zeliadt S.B., Greene P.A., Krebs P., et al. A proactive telephone-delivered risk communication intervention for smokers participating in lung cancer screening: a pilot feasibility trial. J Smok Cessat. 2018;13(3):137–144. [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Aalst C.M., de Koning H.J., van den Bergh K.A., Willemsen M.C., van Klaveren R.J. The effectiveness of a computer-tailored smoking cessation intervention for participants in lung cancer screening: a randomised controlled trial. Lung Cancer. 2012;76(2):204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2011.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masiero M., Lucchiari C., Mazzocco K., et al. E-cigarettes may support smokers with high smoking-related risk awareness to stop smoking in the short run: preliminary results by randomized controlled trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21(1):119–126. doi: 10.1093/ntr/nty047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency Guidance for licensing electronic cigarettes and other inhaled nicotine-containing products as medicines 2021. United Kingdom government website. https://www.gov.uk/guidance/licensing-procedure-for-electronic-cigarettes-as-medicines

- 28.Kanodra N.M., Pope C., Halbert C.H., Silvestri G.A., Rice L.J., Tanner N.T. Primary care provider and patient perspectives on lung cancer screening. A qualitative study. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2016;13(11):1977–1982. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201604-286OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Solberg L.I., Maciosek M.V., Edwards N.M., Khanchandani H.S., Goodman M.J. Repeated tobacco-use screening and intervention in clinical practice: health impact and cost effectiveness. Am J Prev Med. 2006;31(1):62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.03.013. e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piper M.E., Bullen C., Krishnan-Sarin S., et al. Defining and measuring abstinence in clinical trials of smoking cessation interventions: an updated review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22(7):1098–1106. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.London Borough of Hammersmith and Fulham . 2018. Hammersmith & FulhamHammersmith & Fulham Borough Profile.https://www.lbhf.gov.uk/sites/default/files/section_attachments/borough-profile-2018.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 32.London Borough of Hillingdon Who lives in the borough? 2018. London Borough of Hillingdon website. https://www.hillingdon.gov.uk/article/6618/Who-lives-in-the-borough

- 33.London Borough of Sutton London Borough of Sutton website. 2020. https://data.sutton.gov.uk/population/#/view-report/4bd9887cd5de48f48b5813349ec4eeaf/___iaFirstFeature