Abstract

Organizing pneumonia (OP), characterized histopathologically by patchy filling of alveoli and bronchioles by loose plugs of connective tissue, may be seen in a variety of conditions. These include but are not limited to after an infection, drug reactions, radiation therapy, and collagen vascular diseases. When a specific cause is responsible for this entity, it is referred to as “secondary OP.” When an extensive search fails to reveal a cause, it is referred to as “cryptogenic OP” (previously called “bronchiolitis obliterans with OP”), which is a clinical, radiologic, and pathologic entity classified as an interstitial lung disease. The clinical presentation of OP often mimics that of other disorders, such as infection and cancer, which can result in a delay in diagnosis and inappropriate management of the underlying disease. The radiographic presentation of OP is polymorphous but often has subpleural consolidations with air bronchograms or solitary or multiple nodules, which can wax and wane. Diagnosis of OP sometimes requires histopathologic confirmation and exclusion of other possible causes. Treatment usually requires a prolonged steroid course, and disease relapse is common. The aim of this article is to summarize the clinical, radiographic, and histologic presentations of this disease and to provide a practical diagnostic algorithmic approach incorporating clinical history and characteristic imaging patterns.

Key Words: acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia, cryptogenic organizing pneumonia, focal organizing pneumonia, organizing pneumonia, secondary organizing pneumonia

Abbreviations: AFOP, acute fibrinous and OP; COP, cryptogenic OP; DAD, diffuse alveolar damage; FOP, focal OP; GGO, ground-glass opacification; HP, hypersensitivity pneumonitis; HRCT, high-resolution CT; ILD, interstitial lung disease; NSIP, nonspecific interstitial pneumonia; OP, organizing pneumonia; OPP, OP pattern; SOP, secondary OP; TBBX, transbronchial biopsy; UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia

In the context of interstitial pneumonia, the organizing pneumonia (OP) pattern (OPP) refers to the histologic finding of polypoid plugs of loose connective tissue in distal airspaces, mostly alveoli and alveolar ducts and less often bronchioles.1 Cryptogenic OP (COP) as a clinical entity was first described by Davison et al2 in 1983, followed by Epler et al3 in 1985 who coined the term “bronchiolitis obliterans OP” (or “BOOP”). The idiopathic nature and excellent clinical response to corticosteroids also was highlighted in both articles. In 2002, the American Thoracic Society and the European Respiratory Society proposed that the term “COP” should be used rather than BOOP4 and this nomenclature was maintained in the 2013 update.5 “COP” is a term that refers to the clinical entity of unknown cause within the spectrum of idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. In contrast, “secondary OP” (SOP) is the appropriate term when OP is associated with a known cause.2,6, 7, 8 OP is considered a rare disease. Results from retrospective studies looking at the incidence of OP point to a range between 1.97 and 7 per 100 000.9,10 The purpose of this article is to provide a comprehensive review of OP with a focus on radiologic and pathologic manifestations, as well as to provide an algorithmic guide for physicians to diagnose this clinical entity with its common subtypes.

Clinical Presentation

There are no clinical features unique to OP. Consequently, there is often a delay in diagnosis of approximately 6 to 10 weeks because of the nonspecific nature of the symptoms.8,11 Dry cough, flu-like symptoms, and exertional dyspnea are common symptoms seen at presentation.3,12,13 Fevers, fatigue, and weight loss are also reported symptoms in OP.12 Hemoptysis is exceedingly rare. Rapid progression of symptoms with worsening shortness of breath that necessitates mechanical ventilation occurs only rarely, and there are no clinical features that help differentiate COP and SOP (Table 1).14, 15, 16 Although results from one study suggested that the presence of fever favors SOP and longer duration of symptoms favors COP, results from other studies have not shown a similar association.17, 18, 19 Patients with radiographically focal OP (FOP) often have no symptoms. There is no sex predilection, and the median age of manifestation is in the fifth to sixth decades.3,11,12 OP is seen more commonly in nonsmokers.11

Table 1.

Different Manifestations of OP

| Type | Clinical Features | Management |

|---|---|---|

| COP | Flu-like illness, cough, shortness of breath, weight loss, sweats, chills, fevers, myalgia |

|

| SOP | No unique clinical features that differentiate it from COP |

|

| FOP | Frequently without symptoms but otherwise symptoms include cough, shortness of breath, chest pain |

|

COP = cryptogenic OP; CRP = C-reactive protein; ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate; FOP = focal OP; OP = organizing pneumonia; SOP = secondary OP.

Physical examination results usually include inspiratory crackles but may be normal in up to 25% of patients.12 Clubbing is almost always absent.8 Because of the common association of connective tissue diseases with SOP, a detailed examination to evaluate for signs and symptoms of connective tissue disorders is of prime importance. There are no laboratory markers specific for OP. Leukocytosis is seen in approximately 50% of cases, and markers of systemic inflammation such as the C-reactive protein level and/or erythrocyte sedimentation rate are usually elevated.21 Pulmonary function test results can show mild to moderate restriction with reduction in diffusion capacity; however, obstructive ventilatory defects may be seen in smokers.3,11 These test results may be normal, especially in patients with FOP.22

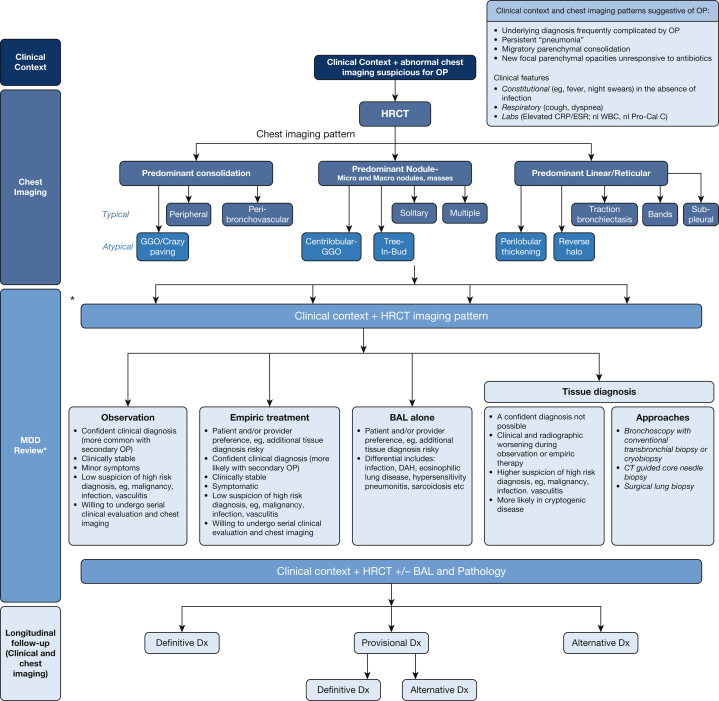

Diagnosis of OP in some instances requires histopathologic confirmation. In other instances, on the basis of the clinical and radiographic presentation, observation or empiric therapy may be considered, as shown in the algorithm (Fig 1). Although surgical lung biopsy is usually necessary for the diagnosis of most interstitial lung diseases (ILDs), bronchoscopy with BAL and transbronchial biopsies (TBBXs) are useful and may be considered as the initial diagnostic procedure in many cases. The radiologic differential diagnoses (see Differential Diagnosis of) include other alveolar processes such as hemorrhage, infection, and malignancy. Therefore, bronchoscopy with BAL and TBBX may be helpful to exclude these processes.23 In OP, BAL usually reveals a mixed cellularity pattern with an increase in lymphocytes, neutrophils, and eosinophils.11 Occasionally, samples obtained by means of TBBX may not be large enough to make a definitive diagnosis, thus necessitating surgical lung biopsy. Alternatively, in some cases, performing a biopsy may be deemed unnecessary if the clinical picture is highly suggestive of OP. A multidisciplinary discussion involving radiologists, pathologists, and pulmonologists, if available, would be of paramount importance. Such discussions may help decide on the best diagnostic approach for the patient. Once a diagnosis of OP is confirmed, an elaborate investigation for secondary causes of OP should be performed.

Figure 1.

Algorithmic approach to organizing pneumonia. ∗ A formal MDD may not be required in all cases, especially if the combination of clinical context and radiographic pattern is sufficiently convincing of the OP diagnosis. In such cases, a discussion between the physician and the radiologist is strongly encouraged. CRP = C-reactive protein; DAH = diffuse alveolar hemorrhage; Dx = diagnosis; ESR = erythrocyte sedimentation rate; GGO = ground-glass opacification; HRCT = high-resolution CT; MDD = multidisciplinary discussion; nl Pro-Cal C = normal procalcitonin; nl WBC = normal WBC; OP = organizing pneumonia.

Corticosteroid therapy is generally recommended for treatment of OP. Although the duration of treatment is not established, initiation at 0.5 to 1.5 mg/kg, followed by gradual weaning over a period of 6 to 12 months is often proposed.11,20 Macrolides may be helpful in some patients as the sole treatment in mild cases or as a bridging treatment from corticosteroids.24 An excellent response to treatment with corticosteroids is usually seen. However, a poor response or failure of treatment is seen in approximately 20% of patients and may require treatment modifications, including institution of other immunosuppressive therapies such as cyclophosphamide, azathioprine, mycophenolate, or rituximab.20 There is a high rate of relapse, ranging from 13% to 58% of cases, usually during steroid dose reduction or treatment suspension,. especially if steroids are tapered abruptly; however, relapses generally are not associated with poor outcomes.11,20 Given the inflammatory nature of OP, following inflammatory markers such as the C-reactive protein levels and erythrocyte sedimentation rates may help predict relapse and response to treatment.25

Radiologic Features

Investigators in numerous studies (nearly all retrospective and small) have described the imaging findings of OP.1,26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32 Although all document the markedly variable appearances of OP at CT scanning, there are no substantial differences in the imaging patterns of COP and SOP, and there has been only moderate consensus in standardizing the classification of the radiologic features. For our purposes, the following organizational approach is taken (Table 2).

Table 2.

An Organizational Approach to OP Imaging Findings With Main Chest Radiography and CT Scanning Differential Diagnoses33, 34, 35, 36

| Imaging Finding | Differential Diagnosis |

|---|---|

| Predominant consolidation | |

| Peripheral | Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, infection (eg, COVID-19), hemorrhage, infarction, vasculitis, aspiration, postradiation pneumonitis, drug toxicity, electronic cigarettes (EVALI), adenocarcinoma, primary pulmonary lymphoma |

| Peribronchovascular | Solitary vs multicentric adenocarcinoma, primary pulmonary lymphoma, sarcoidosis, vasculitis, CVD (especially polymyositis or dermatomyositis), Kaposi sarcoma, chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, granulomatosis with polyangiitis |

| Ground-glass attenuation, crazy paving | Acute: infection, hemorrhage, edema, drug toxicity |

| Chronic: Pulmonary alveolar proteinosis, infection, exogenous lipoid pneumonia, drug toxicity (eg, nitrofurantoin), mucinous adenocarcinoma | |

| Predominant nodular pattern | |

| Solitary | Bronchogenic carcinoma, infection (granuloma), metastatic disease |

| Multiple | Metastatic disease, multicentric adenocarcinoma, sarcoidosis, invasive fungal disease |

| Predominant linear or reticular pattern | |

| Subpleural, basilar reticulation with or without traction bronchiectasis | NSIP, UIP or IPF |

| Bands | Asbestosis, scars or sequelae of ARDS, infection (eg, paracoccidioidomycosis), atelectasis |

| Perilobular thickening | UIP or IPF, hemorrhage, atypical pneumonia, chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, lymphoproliferative disorders |

| Reverse halo | Granulomatosis with polyangiitis, sarcoidosis, lipoid pneumonia, adenocarcinoma in situ, infection (COVID-19, invasive fungal disease), infarction, radiation pneumonitis, drug toxicity |

CVD = collagen vascular disease; EVALI = e-cigarette or vaping product use-associated lung injury; IPF = idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; NSIP = nonspecific interstitial pneumonia; OP = organizing pneumonia; UIP = usual interstitial pneumonia.

Findings Characterized by a Spectrum of Parenchymal Consolidation

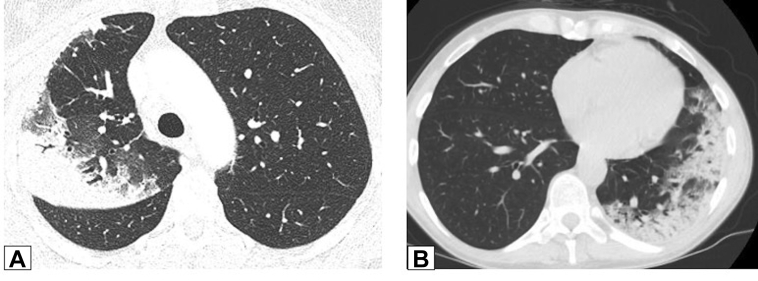

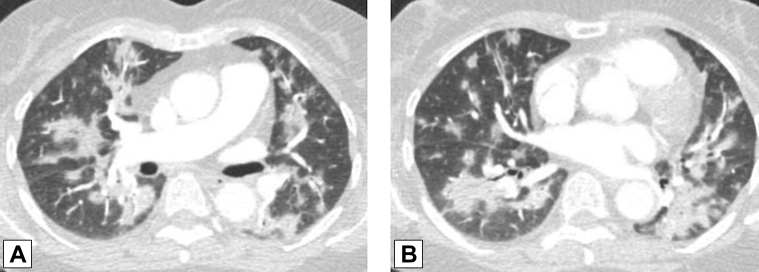

Typically described as most often bibasal, peribronchovascular, and/or peripheral, consolidation is the most common finding in cases of documented OP, occurring in nearly three-quarters of cases (Figs 2, 3).30 Characteristically migratory (Figs 4, 5), consolidation may occur anywhere throughout the lungs and appears well defined or poorly marginated; focal, multifocal, or diffuse; or nodular or mass like (Fig 6). Consolidation is often associated with air bronchograms and may be accompanied by scattered foci of ground-glass attenuation or small parenchymal nodules. Less commonly, the findings consist of predominant or exclusive ground-glass attenuation (Fig 7). These findings may be associated with extensive intralobular linear opacities, septal thickening, or reticulation, resulting in the so-called crazy-paving pattern (Fig 8).37

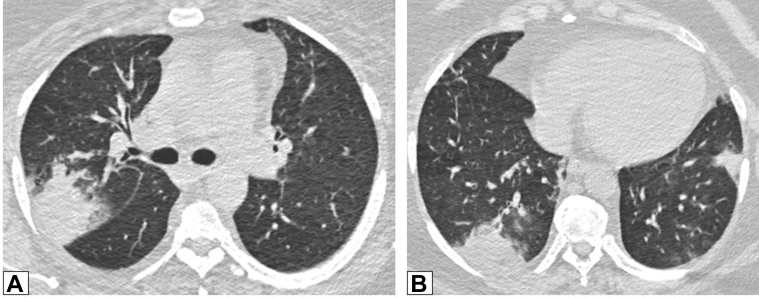

Figure 2.

A, B, Peripheral consolidation. Axial unenhanced CT scan images obtained in two patients. A, This image shows peripheral consolidation in the right upper lobe in a woman previously treated with radiation for breast cancer and biopsy-proved organizing pneumonia (OP). B, This image shows peripheral consolidation in the left lower lobe and lingula and biopsy-proved OP secondary to chemotherapy for treatment of lymphoma.

Figure 3.

A, B, Peribronchovascular consolidation. Axial contrast-enhanced CT scan images through the middle (A) and lower (B) lung zones show multifocal, bilateral foci of peribronchovascular consolidation in a patient with biopsy-proved organizing pneumonia.

Figure 4.

A-C, Migratory manifestation of organizing pneumonia (OP). A, Posteroanterior chest radiograph in a 71-year-old man presenting with dyspnea on exertion in July 2011 shows peripheral right upper lobe (RUL) consolidation. B, Repeat study from June 2012 shows that the RUL abnormality had resolved and that there is now extensive consolidation in the left lung. C, In June 2013, the left lung is now clear, but there is now new right lower lobe consolidation. These findings are typical of a migratory manifestation of OP.

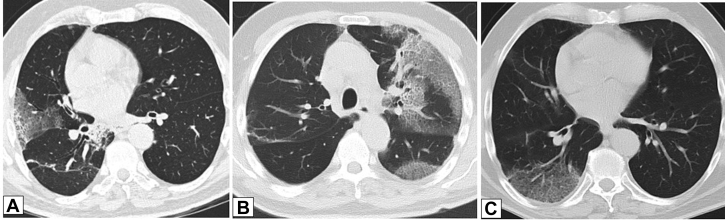

Figure 5.

A-C, Migratory manifestation of organizing pneumonia (OP). Axial unenhanced CT scans were obtained in a 71-year-old man with dyspnea on exertion, the same patient as in Figure 4. The CT scanning sections, which correspond with Figures 4A, 4B, and 4C, respectively, show that foci of consolidation on the chest radiographs in this case are due to migratory foci of ground-glass opacification with interlobular septal thickening and intralobular lines (crazy paving). Surgical lung biopsy results were consistent with OP.

Figure 6.

Multifocal, peribronchovascular, mass-like consolidation. Axial unenhanced CT scan image shows multifocal, peribronchovascular, mass-like consolidation in a 70-year-old woman with persistent shortness of breath 9 months after the diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia. Organizing pneumonia was presumed to be the diagnosis after dramatic improvement in symptoms and resolution of consolidation after treatment with steroids.

Figure 7.

A-C, Ground-glass opacification (GGO). A, Axial unenhanced CT scan image in a 47-year-old man with a history of papillary thyroid cancer, 4 months after treatment with iodine-131, shows right upper lobe peribronchovascular GGO. The GGO is hypermetabolic on a fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose-PET/CT scan (B), with less intense activity also noted in a new smaller area of GGO in the left upper lobe in an axial unenhanced CT scan image (C). Transbronchial biopsy results were consistent with organizing pneumonia.

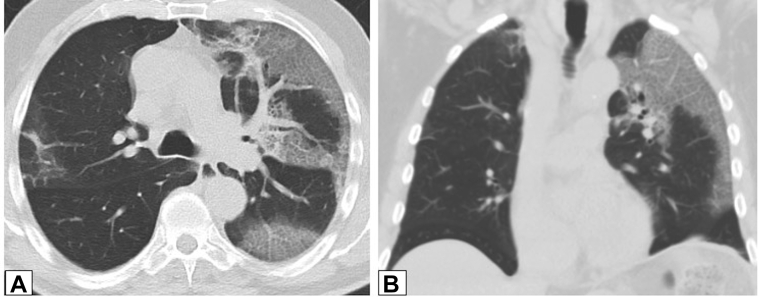

Figure 8.

A, B, Crazy-paving pattern. Axial (A) and coronal (B) unenhanced CT scan images in a 71-year-old man who had secondary organizing pneumonia due to amiodarone use. There is extensive ground-glass opacification in the left lung with superimposed interlobular septal thickening and intralobular lines (crazy paving).

Findings Characterized by a Spectrum of Parenchymal Nodules

These range from small (Fig 9) micronodules (< 4 mm) to larger discrete nodules (typically up to 1 cm), as well as larger nodules or masses (Fig 10). These latter have been described as frequently having irregular or spiculated margins and often containing air bronchograms (Fig 11).38,39 Nodules may be solitary (so-called FOP) (Fig 12) or multiple and are usually solid, although partly solid lesions sometimes occur.22,40, 41, 42 Although evaluation of these lesions with fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose-PET scanning can show mild elevation in standardized uptake value, results are nonspecific and of limited clinical value (Figs 13, 14). Less commonly seen patterns of OP are micronodular including diffuse, centrilobular, poorly defined nodules (as seen in cases of nonfibrotic hypersensitivity pneumonitis [HP], for example) and tree-in-bud opacities suggestive of bronchiolar infection and/or inflammation.38

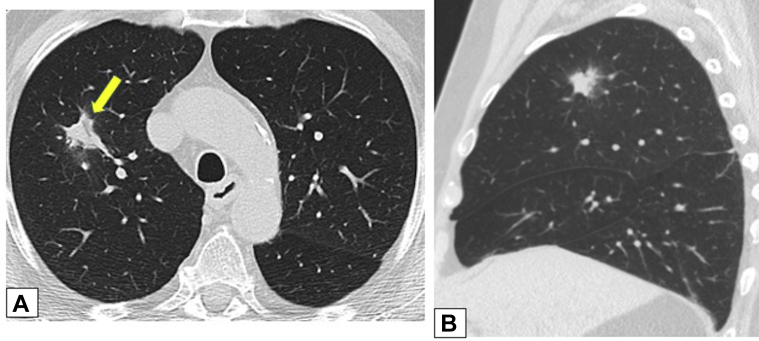

Figure 9.

A, B, Small micronodules. Axial high-resolution CT scanning section (A) and maximum intensity projection image (B) in the same patient. CT scan images demonstrate multiple small, solid lung nodules bilaterally that are suggestive of possible malignancy or infection. CT scanning-guided core biopsy results were consistent with a diagnosis of organizing pneumonia.

Figure 10.

A, B, Masses. Axial unenhanced CT scan images through the right upper lobe (A) and right lower lobe (B) in a 42-year-old patient who was morbidly obese and had dyspnea show bilateral, subpleural or peripheral mass-like areas of consolidation. The findings are nonspecific; subsequent biopsy results documented organizing pneumonia, and findings resolved after treatment with steroids.

Figure 11.

A-C, Air bronchograms. A 38-year-old man with ulcerative colitis treated with mesalamine developed shortness of breath. A, A posterolateral chest radiograph demonstrates multiple bilateral lung nodules. Axial (B) and coronal (C) contrast-enhanced chest CT scans show the nodules to be both peripheral and peribronchovascular, some associated with dilated airways (arrows in B and C). Core biopsy results were consistent with organizing pneumonia.

Figure 12.

A, B, Solitary nodules. Axial (A) and sagittal (B) unenhanced images from low-dose CT scanning lung cancer screening in a 73-year-old male smoker show a solitary, irregular right upper lobe nodular opacity associated with subtle dilated airways (arrow in A). Endobronchial ultrasound-guided fine-needle biopsy results were consistent with focal organizing pneumonia. The opacity resolved without treatment on a follow-up scan (not shown).

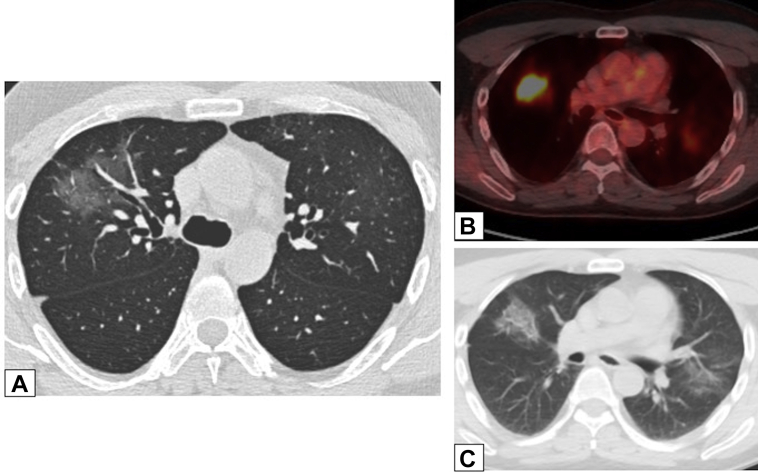

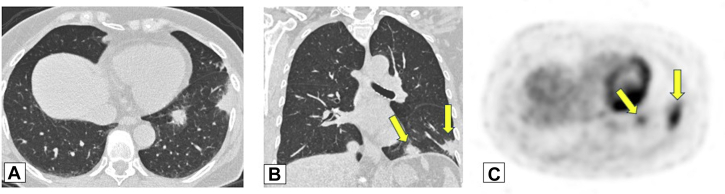

Figure 13.

A-C, Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET scanning. Axial (A) and coronal (B) unenhanced CT scan images from a routine surveillance scan in a 70-year-old woman without symptoms with a history of breast cancer and long-term nitrofurantoin use show irregular, solid lung nodules in both lower lobes. C, FDG-PET scanning was performed because of concern for metastatic disease, and an axial FDG-PET image shows the left lower lobe (LLL) nodules (arrows in B and C) to be FDG avid. Core transthoracic needle biopsy results for the LLL nodule were consistent with organizing pneumonia.

Figure 14.

A, B, Fluorine-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-PET scanning. A 34-year-old woman with systemic lupus erythematosus presented with shortness of breath. A, An axial unenhanced chest CT scan through the lower lobes shows multiple variable-sized solid nodules in both lungs, including micronodular changes in the left base. B, A coronal image from FDG-PET scanning shows the nodules are hypermetabolic. Wedge biopsy results from two nodules were consistent with organizing pneumonia.

Findings Characterized by a Spectrum of Linear Opacities or Reticulation

This type includes parenchymal bands appearing as curvilinear opacities, usually extending to pleural surfaces, often preceded by foci of ground-glass attenuation or consolidation (Fig 15).1,27,30,32 Other findings include perilobular thickening and lesions characterized as having a reverse halo appearance (Fig 16). This sign, also referred to as the “atoll sign,” is characterized by central ground-glass opacification (GGO) and peripheral consolidation.33, 43, 44,33,43,44 These imaging patterns share strikingly similar characteristics and often can be identified in the same case, even on the same image. Although these findings are associated with a variety of clinical entities, there is considerable overlap between OP and chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, especially when findings are predominantly upper lobe in distribution.

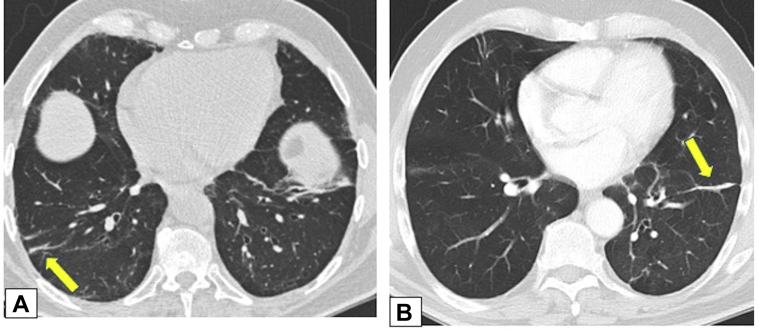

Figure 15.

A, B, Parenchymal bands. Axial unenhanced (A) and contrast-enhanced (B) CT scans obtained 1 year apart in same patient with biopsy-proved organizing pneumonia show only partially resolving parenchymal bands (arrows in A and B) in both lower lobes.

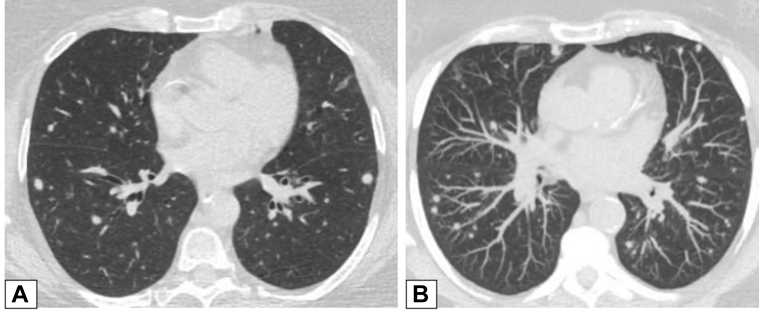

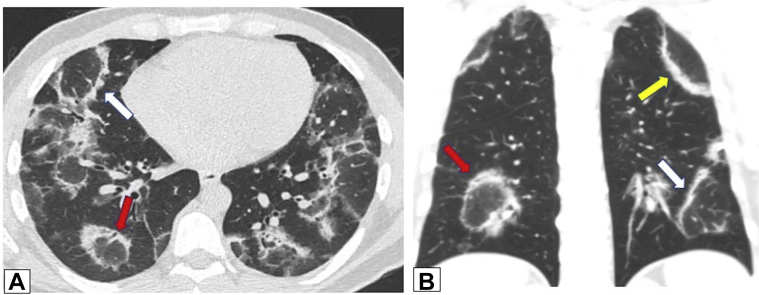

Figure 16.

A, B, Reverse halo or atoll sign. CT scan images obtained in a 32-year-old man with chronic persistent cough and dyspnea on exertion for 1 year and 20-pound weight loss. Axial (A) and coronal (B) images show bilateral foci of central ground-glass opacification completely surrounded by dense peripheral consolidation—the reverse halo or atoll sign (red arrows in A and B). Also present are foci of incomplete halo signs (white arrows in A and B) and perilobular thickening (yellow arrow in B). Overlap of these findings is clearly present. Lung biopsy results documented organizing pneumonia.

Further along on the spectrum of linear opacities are the cases that reveal the development of basal, subpleural reticulation after peripheral consolidation or GGO, suggestive of developing interstitial fibrosis (Fig 17).1,30, 31, 32,45,46 Although the development of honeycombing and architectural distortion may indicate progression to fibrosis, evidence of OP also may be seen in cases of documented usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) or idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, complicating definitive diagnosis.32 In addition, OP may result in extensive bibasal traction bronchiectasis associated with relative sparing of the dorsal subpleural lung regions, findings that both mimic and frequently overlap those of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) (Figs 18, 19).47

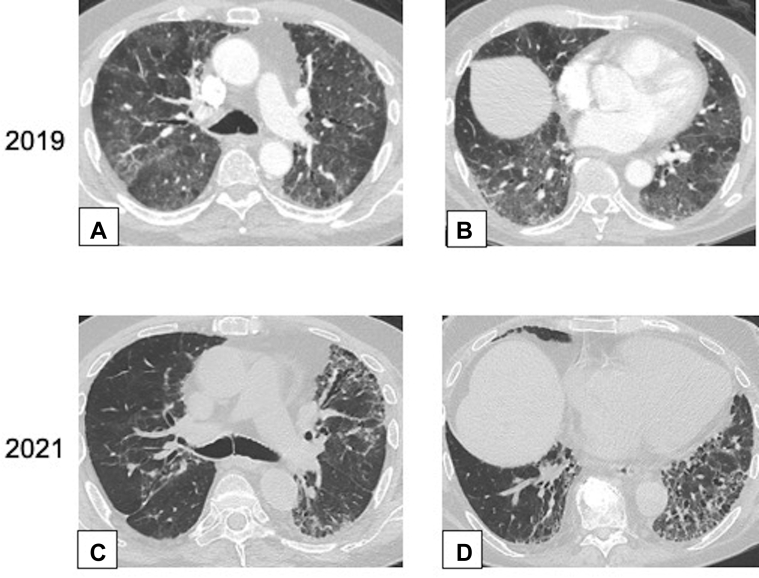

Figure 17.

A-D, Interstitial fibrosis. Axial CT scan images obtained in a 73-year-old man after a 4-day onset of dyspnea. The CT scan images of the chest were obtained with lung windows at the level of the carina (A) and (C) and at the lung bases (B) and (D), respectively. Contrast-enhanced images in the upper row from 2019 (A and B) show extensive ground-glass opacification (GGO) bilaterally. Unenhanced images in the lower row from 2021 (C and D) show improvement in the extent of GGO but development of increased reticulation and traction bronchiectasis or bronchiolectasis, a pattern consistent with fibrosis. Wedge biopsy results from the right upper, middle, and lower lobes showed organizing pneumonia.

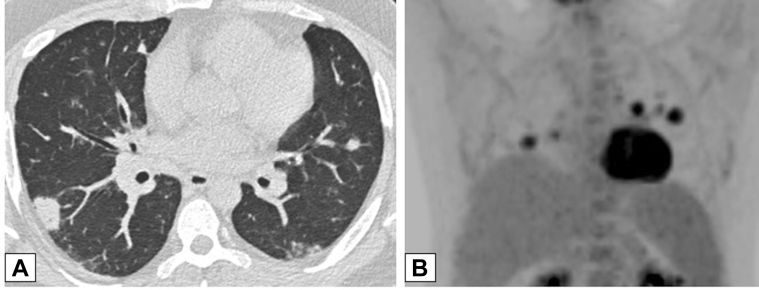

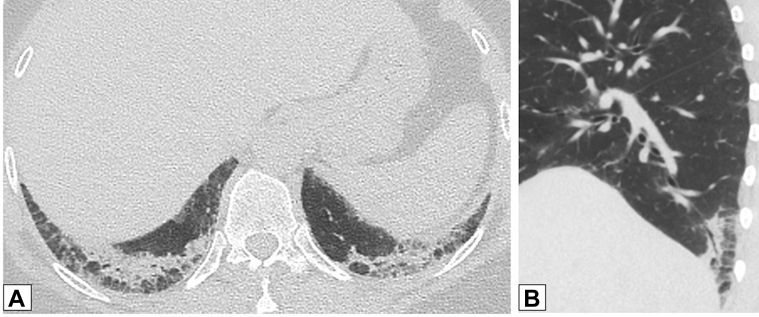

Figure 18.

A, B, Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP). Unenhanced CT scans were obtained in a 51-year-old woman with dermatomyositis. Axial (A) and sagittal (B) images through the posterior lung bases show consolidation in both lower lobes with subpleural sparing and perilobular opacities bilaterally. Dilated bronchi were evident on the sagittal image (B). The findings were consistent with overlap of organizing pneumonia and NSIP.

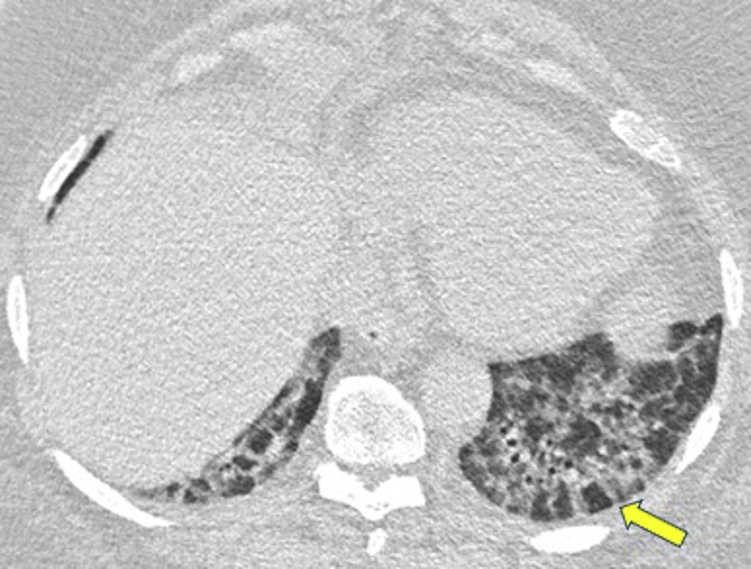

Figure 19.

Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP). An axial CT scan was obtained in a 67-year-old man who was morbidly obese and had progressive dyspnea. The CT scan through the lung bases shows a combination of thick-walled peripheral bronchi associated with poorly defined ground-glass attenuation and perilobular thickening, especially in the left base (arrow), which are findings suggestive of NSIP. Surgical lung biopsy findings were consistent with organizing pneumonia.

Pathologic Features

In this article, the term “OP” is used as a clinical term that includes COP and SOP. To clarify, when discussing pathologic findings, the term “OPP” is used for the histologic features of OP.

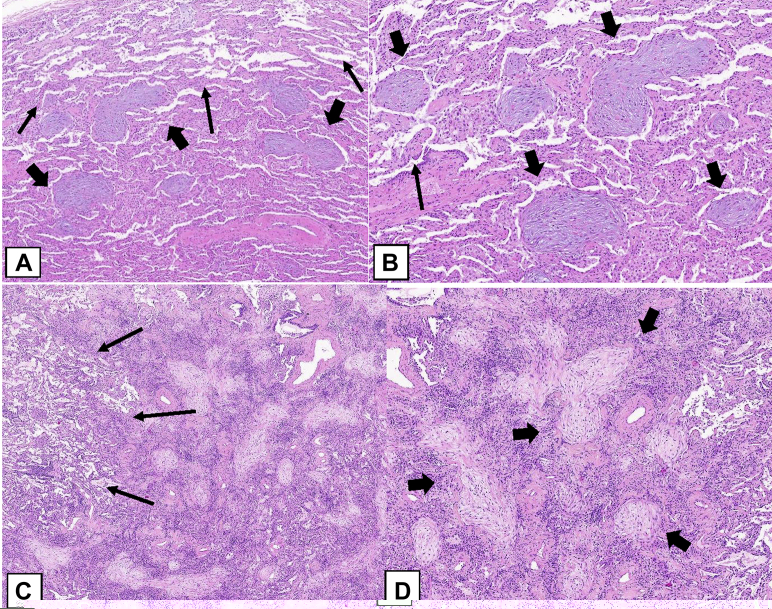

At low power, OPP is patchy, with relatively normal lung adjacent to nodular zones of organization (Fig 20).5,48 The organizing fibrosis consists of intraluminal polypoid plugs of loose connective tissue that protrude into distal airways. Alveolar spaces and alveolar ducts are usually most affected, with lesser involvement of bronchioles (Figs 20A, 20B), and in some cases, biopsy specimens do not show bronchiolar involvement. OPP lesions can be situated in a peribronchiolar location. Less commonly, they may be present at the periphery of the lobule, corresponding to the perilobular pattern seen at CT scanning (Fig 21). All of the connective tissue appears to be approximately the same age, and the architecture of the lung is preserved. Surgical biopsy specimens from patients with COP or SOP typically show multicentric foci of OPP. In FOP, the histologic appearance is similar to that of COP or SOP, but it consists of a solitary circumscribed nodule showing the OPP (Figs 20C, 20D).41,49 Interstitial fibrosis is inconspicuous or absent. Honeycomb change is not seen. Because of the distal airway occlusion, endogenous lipoid pneumonia may be present, consisting of airspace accumulation of foamy, lipid-laden macrophages. Alveolar fibrinous exudates may be present, but these are usually focal. Interstitial chronic inflammation is usually mild to moderate. Type 2 pneumocyte hyperplasia is usually inconspicuous.

Figure 20.

A-D, Histologic findings of an organizing pneumonia (OP) pattern (OPP). In this case of cryptogenic OP with multifocal lung involvement, a low-power histologic image (A) shows patchy areas of polypoid intraluminal plugs (thick arrows) of loose connective tissue that protrude into distal airways. The adjacent lung parenchyma is relatively normal (thin arrows). B, In this field, the polypoid plugs are seen within alveolar spaces and alveolar ducts (thick arrows), but bronchiolar involvement is minimal (thin arrows). The connective tissue is the same age, and the alveolar architecture is preserved. C, In this case of focal OP, there is a nodular lesion consisting of the OPP as seen in (A) and (B) surrounded by relatively normal lung (thin arrows). D, The lesion consists of polypoid plugs of loose connective tissue within distal airspaces (thick arrows).

Figure 21.

A-D, Perilobular organizing pneumonia (OP) pattern (OPP). A, Axial CT scan image obtained at the level of the upper lobes shows perilobular opacities in the periphery of the right lung (arrows). B, In this surgical lung biopsy specimen, the lesions of the OPP (thick arrows) are also seen histologically to be situated at the periphery of the lobule away from the bronchiole (thin arrows) at the center of the lobule. C, Medium power highlights the OPP lesions at the periphery of the lobule (thick arrows) away from the bronchiole (thin arrows) at the center of the lobule. D, Higher power shows polypoid plugs of loose connective tissue protruding into distal airspaces (thick arrows).

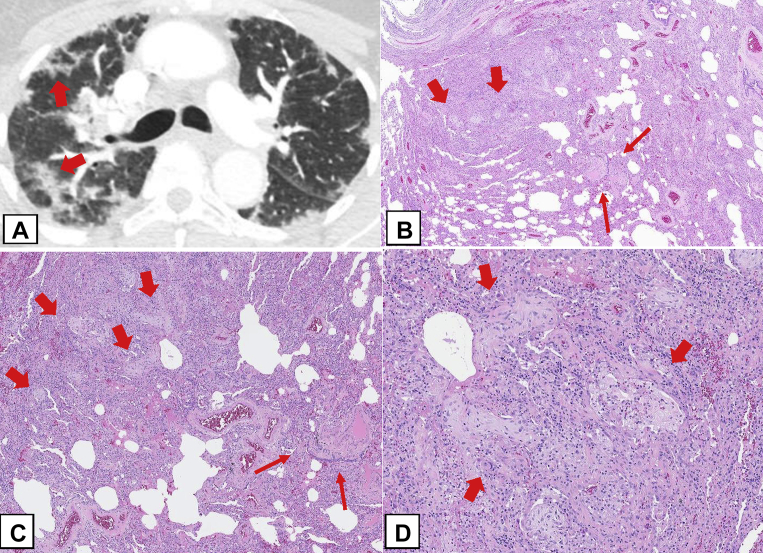

OPP histologic features can be encountered in a variety of settings. Although underlying disorders sometimes exhibit suggestive features on biopsy specimens, it may be impossible to distinguish COP from SOP by means of histologic examination alone. In some cases, histologic sampling of lung tissue, even in generous surgical lung biopsy specimens, can be misleading. Specimens may show only minimal amounts of OPP and mostly other findings, such as NSIP (Fig 22). In such cases, unless the CT scan is reviewed for radiologic-pathologic correlation, the predominant lung involvement by consolidation, indicating a primary diagnosis of the OPP, could be overlooked.

Figure 22.

A-C, Secondary organizing pneumonia (OP): radiologic-pathologic correlation. A, On a surgical lung biopsy specimen, this patient with Sjögren syndrome had the cellular nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) pattern as the predominant lesion. There is a diffuse, moderate cellular interstitial infiltrate of lymphocytes and plasma cells causing mild thickening of the alveolar walls. There are many lymphoid aggregates (arrows). B, Focal areas show OP with polypoid plugs of loose connective tissue in the distal airways (arrows). C, An axial CT scan obtained with the patient prone demonstrates peribronchial areas of consolidation with air bronchograms characteristic of OP. Also noted are bilateral ground-glass opacification and mild reticulation suggestive of NSIP. Surgical biopsy results showed predominant NSIP and mild focal OP. The extent of OP was underestimated on the biopsy specimen, presumably because it is peribronchial and away from the pleura, whereas the NSIP pattern also involves the subpleural regions. The radiologic-pathologic correlation in this case indicated the CT scanning findings trumped the surgical lung biopsy findings, and in this clinical setting secondary OP associated with Sjögren syndrome was diagnosed.

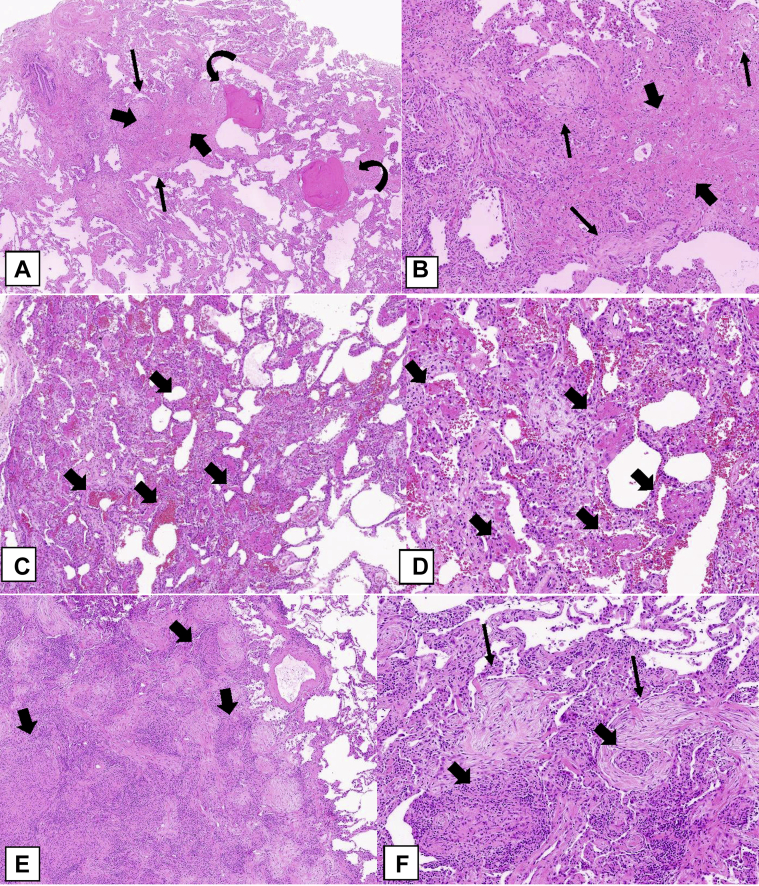

Three rare histologic patterns associated with OP can occur (Table 3): (1) cicatricial OP (Figs 23A, 23B), (2) acute fibrinous and OP (AFOP) (Figs 23C, 23D), and (3) granulomatous OP (Figs 23E, 23F).46 These rare histologic patterns have clinical characteristics that can differ from those of COP, SOP, and FOP.

Table 3.

Rare Histologic Patterns of OP

| Type | Manifestation | Treatments and Outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Cicatricial OP | This type can occur in the setting of COP or SOP, and the manifestation is similar to that of noncicatricial cases. | Outcomes are indolent and favorable. |

| AFOP | This type has a CAP-like picture, with significant elevation of inflammatory markers, andnonspecific presenting symptoms. | Therapeutic strategies vary considerably according to the underlying disease and clinical presentation, and these include antibiotics, corticosteroids, and other immunosuppressants, including cyclophosphamide. Outcomes are variable. |

| GOP | Clinical presentation may be associated with cough, dyspnea, and wheezing. | This type clinically causes fewer symptoms than do other variants. Usually, no specific treatment is required. |

AFOP = acute fibrous and OP; CAP = community-acquired pneumonia; COP = cryptogenic OP; GOP = granulomatous OP; OP = organizing pneumonia; SOP = secondary OP.

Figure 23.

A-F, Rare histologic patterns: cicatricial organizing pneumonia (OP) pattern (OPP), acute fibrinous and OP (AFOP), and granulomatous OP (GOP). A, B, Cicatricial OPP. This biopsy specimen shows polypoid plugs of connective tissue within distal airspaces, but most of it consists of fibrosis composed of eosinophilic dense collagen (thick arrows). This dense fibrosis contrasts with the adjacent loose fibrosis (thin arrows) typically seen in OPP. In addition, there are spicules of bone associated with the intraluminal polypoid plugs in the pattern of dendriform ossification (curved arrows). C, AFOP. This biopsy specimen shows extensive fibrin with a bright eosinophilic appearance within many airspaces (arrows) in addition to polypoid plugs of loose connective tissue within the airspaces. D, Most of the alveolar spaces in this biopsy specimen show eosinophilic fibrin (thick arrows) accumulation within distal airspaces in addition to OPP lesions. E, GOP. This biopsy specimen shows a nodular infiltrate that indicates OPP in addition to multiple noncaseating granulomas (thick arrows). F, Higher power shows intraluminal polypoid plugs of loose connective tissue in the distal airways (thin arrows) adjacent to rounded collections of epithelioid histiocytes forming noncaseating granulomas (thick arrows).

The cicatricial OP cases show intraluminal polypoid plugs of connective tissue the same as those of COP, SOP, and FOP but also containing dense fibrotic collagen rather than consisting purely of loose connective tissue characteristic of the usual OPP (Figs 23A, 23B), which may be associated with dendriform ossification (Fig 23A).45,50 The AFOP histologic pattern can occur in a spectrum of clinical settings, ranging from a relatively indolent clinical picture that may resemble COP or SOP to a more severe illness with patients in respiratory failure and a clinical picture that suggests the disease is more in keeping with diffuse alveolar damage (DAD).51,52 In the latter cases, there may be a sampling problem in which more definite histologic features of DAD were not obtained in the lung biopsy specimen.51 Granulomatous OP is another uncommon finding in which biopsy specimens show a mixture of the OPP and noncaseating granulomatous inflammation.52 Extra care should be taken to exclude infection, sarcoidosis, collagen vascular disease, or drug toxicity in such cases. The presence of necrotizing granulomas strongly favors infection.

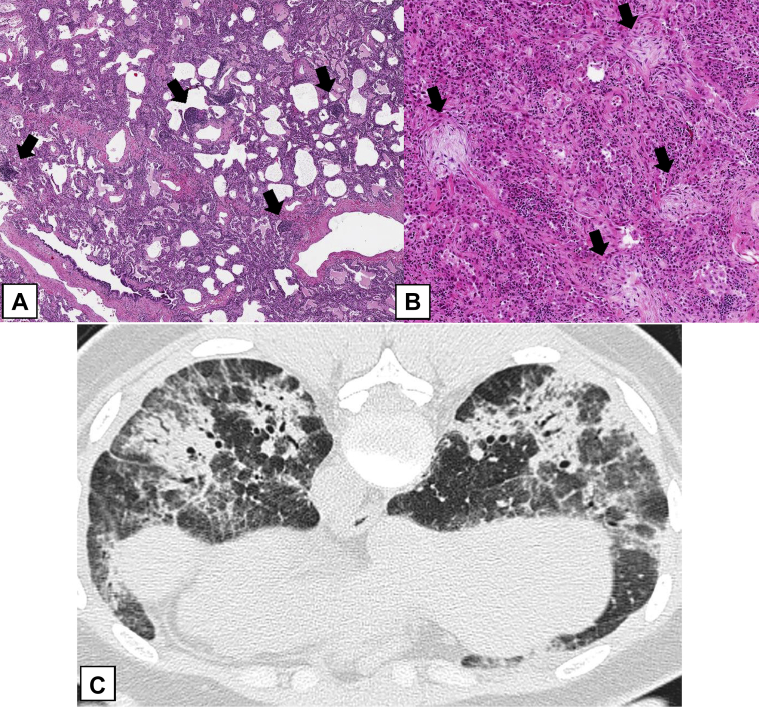

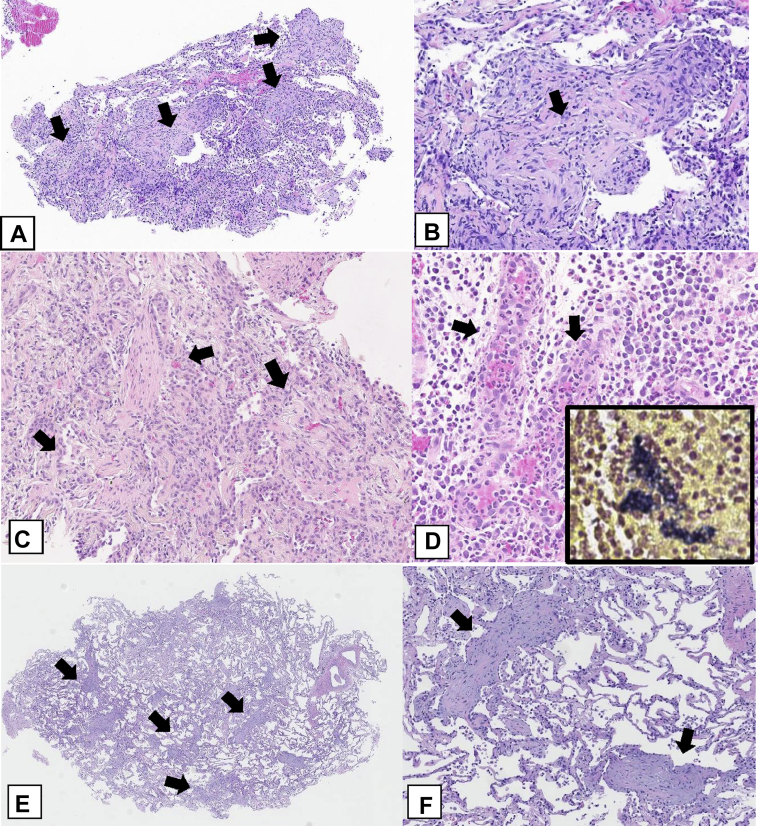

Biopsy Specimen Size

The larger the biopsy specimen, the greater the chance of making a confident pathologic diagnosis of the OPP, but as pointed out in Figure 22, even in a substantial amount of tissue obtained during a surgical lung biopsy, the OP lesions may be missed and identified only by means of CT scanning. In small biopsy specimens, such as TBBX specimens (Figs 24A, 24B), core biopsy specimens (Figs 24C, 24D), or transbronchial cryobiopsy specimens (Figs 24E, 24F), OPP may be identified, but because of the paucity of lung tissue, it can be difficult to search for histologic clues to an associated pathologic process. These associated processes include DAD (Figs 25A, 25B) or an underlying cause such as a neoplasm (Figs 25C, 25D), abscess (Figs 24C, 24D), or infarct (Fig 25E). For this reason, if the basis of recognizing the OPP is a small piece of lung tissue, one must be especially careful to correlate the biopsy findings with the clinical and radiographic picture, which should be classical before establishing a diagnosis of COP or SOP. Appropriate follow-up with response to therapy should be considered part of the diagnostic process.

Figure 24.

A-F, Transbronchial biopsy, core biopsy, and transbronchial cryobiopsy specimens. A, Transbronchial biopsy specimen. This generous-sized transbronchial biopsy specimen shows multiple polypoid plugs of loose connective tissue (arrows) within distal airspaces. B, Higher power shows a polypoid plug of loose connective tissue (arrow) protruding into an alveolar space. A mild interstitial chronic inflammatory infiltrate is also present. C, Core biopsy specimens. In one of multiple core biopsy specimens obtained in this patient, the only finding was organizing pneumonia with multiple intraluminal polypoid plugs of loose connective tissue (arrows) in the distal airways. D, A separate core biopsy specimen shows an acute abscess with granulation tissue (arrows) and many neutrophils. Gram stain results show numerous gram-positive bacteria, staining dark blue (insert). E, F, Transbronchial cryobiopsy specimen. This cryobiopsy specimen shows OPP with evenly distributed intraluminal polypoid plugs of loose connective tissue (arrows) in the distal airspaces. Interstitial inflammation is minimal, and the alveolar architecture is preserved.

Figure 25.

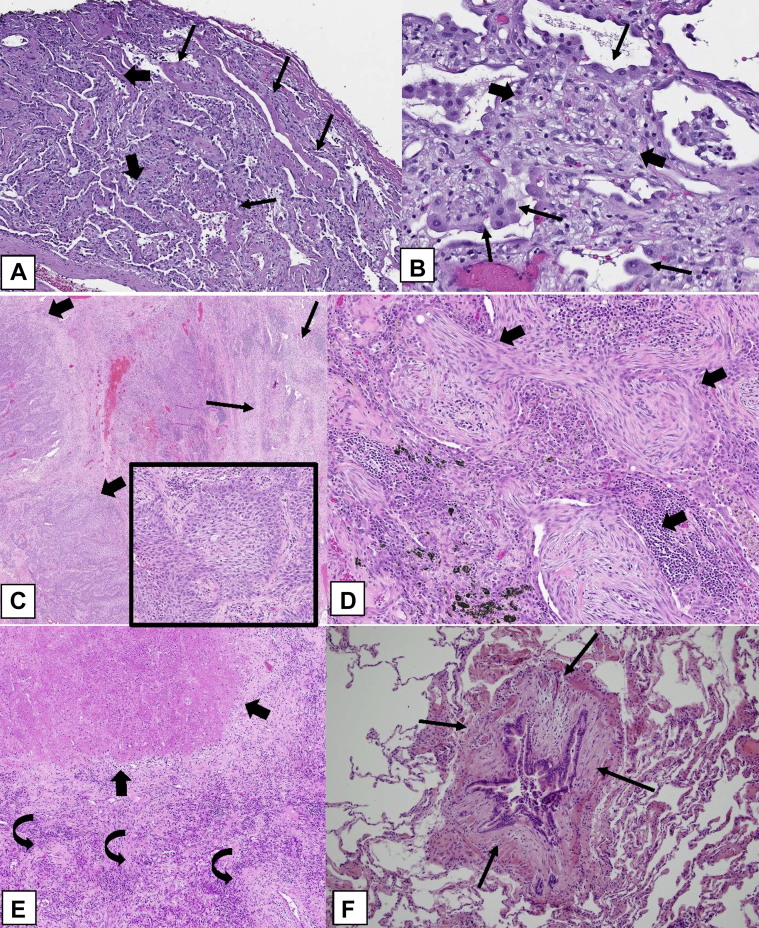

A-F, Differential diagnosis of the organizing pneumonia (OP) pattern (OPP). A, Diffuse alveolar damage OPP. This biopsy specimen shows diffuse involvement with organizing connective tissue causing thickening of the alveolar walls (thick arrows) and associated hyaline membranes (thin arrows) consisting of dense, pink hyaline exudates lined up along the alveolar wall surfaces. B, In addition to the loose connective tissue causing thickening of the alveolar walls (thick arrows), there is prominent pneumocyte hyperplasia with some atypical features (thin arrows). C, OP adjacent to squamous cell carcinoma. The lung parenchyma surrounding this squamous cell carcinoma (thick arrows) contains areas showing OPP (thin arrows). The squamous cell carcinoma consists of nests of tumor cells showing features of keratinization (insert). D, The OP consists of intraluminal polypoid plugs of loose connective tissue within distal airspaces (arrows), similar to that seen in the OPP associated with cryptogenic OP or secondary OP. E, OP surrounding an infarct. This infarct consists of a rounded area of eosinophilic dead lung tissue (thick arrows). It is surrounded by a fibroinflammatory reaction that has a prominent OP component (curved arrows). F, Constrictive bronchiolitis. This bronchiole shows a concentric layer of fibrosis (arrows) between the overlying respiratory mucosa and the underlying normal smooth muscle that surrounds the bronchiole. This fibrosis is causing marked narrowing of the bronchiolar lumen.

Differential Diagnosis (Pathologic Aspects)

Clinical OP (COP or SOP) must be distinguished with a multidisciplinary approach from the histologic or radiologic OPP seen in biopsy specimens or by using CT scanning as a component of other ILDs or as a nonspecific reactive lesion (Table 4). In ILDs, the OPP can be seen as (1) a minor lesion in the setting of ILDs, such as UIP, NSIP, or HP; (2) as a component of organizing acute lung injury, such as DAD; (3) as a manifestation of acute exacerbation of UIP or idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis or various other ILDs, including NSIP or HP, in which the underlying disease of one of these chronic ILDs is also present in a biopsy specimen and/or at CT scanning; and (4) in the setting of mixed patterns of lung injury, particularly NSIP and OP or eosinophilic pneumonia and OP. Distinguishing between OPP and eosinophilic pneumonia can be very difficult by means of CT scanning and/or biopsy, particularly if the patient has received corticosteroids before the biopsy, resulting in a significant reduction in the number of eosinophils in tissues.14, 15, 16,53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58

Table 4.

Classification of OP

| Type | Description | |

|---|---|---|

| COP | An exhaustive search for different causes for OP has been unrevealing, and the primary pathologic process within the lung is an OP pattern. | |

| SOPa | OP here is secondary to a known pulmonary insult, and the primary pathologic process within the lung is OP. | |

| Causes | Examples | |

| After infectionb | Bacteria, viruses, parasites, fungi, mycobacteria | |

| Drug toxicityc | Antibiotics, antiepileptics, antiarrhythmics, immunosuppressants | |

| Inhalation of toxic chemicals or substances | Cocaine inhalation, hydrogen sulfide, industrial gases, electronic nicotine delivery systems with adulterated products (EVALI) | |

| Aspiration of gastric contents | … | |

| Organ transplant | Bone marrow transplant, lung transplant, liver transplant | |

| Radiotherapy | Especially in breast cancer | |

| Rheumatologic disorders | Rheumatoid arthritis, SLE, Sjögren syndrome, dermatomyositis, polymyositis | |

| Miscellaneous | Inflammatory bowel disease, polymyalgia rheumatica, CABG | |

| Entities with an OP pattern separate from COP and SOP | ||

| OP pattern according to pathologic examination or CT scanning as a component of other ILDs | ||

| Causes | Examples | |

| A minor lesion in the setting of ILD14,15 | UIP, NSIP, or HP14 | |

| A component of organizing acute lung injury such as DAD | … | |

| A manifestation of acute exacerbation of UIP or IPF or various other ILDs, including NSIP and HP16 | UIP or IPF or various other ILDs, including NSIP and HP | |

| In the setting of mixed patterns of lung injury | NSIP and OP or eosinophilic pneumonia and OP16 | |

| Nonspecific reaction to another process often at the periphery of underlying primary lung disease | ||

| Causes | Examples | |

| Primary lung cancers | Any tumor such as lung cancer or lymphomas | |

| Pulmonary infarct | … | |

| Aspiration | … | |

| Lung abscess | … | |

| Pulmonary vasculitis or hemorrhage | GPA, EGPA, hemorrhage with microscopic polyangiitis, capillaritis | |

CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; COP = cryptogenic OP; DAD = diffuse alveolar damage; EGPA = eosinophilic GPA; EVALI = e-cigarette or vaping product use-associated lung injury; GPA = granulomatosis with polyangiitis; HP = hypersensitivity pneumonitis; ILD = interstitial lung disease; IPF = idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis; NSIP = nonspecific interstitial pneumonia; OP = organizing pneumonia; SLE = systemic lupus erythematosus; SOP = secondary OP; UIP = usual interstitial pneumonia.

This is not an exhaustive list of all causes of SOP but is instead a partial list of the most commonly associated diseases leading to SOP.

This usually manifests as a nonresolving infectious process.

The full list is in pneumotox.com.11

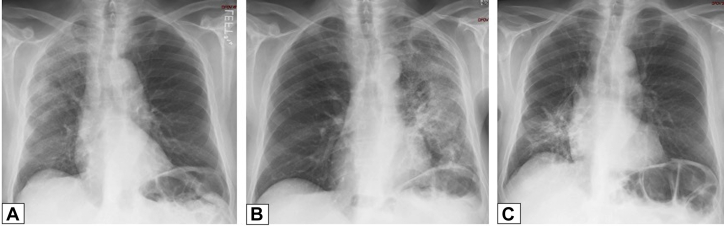

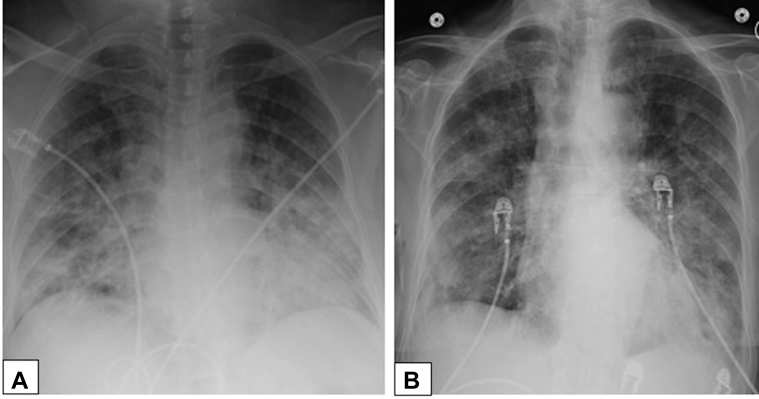

In cases in which the lesion appears to be predominantly that of the OPP, biopsy specimens should be evaluated for features suggestive of an underlying cause of SOP, such as prominent interstitial chronic inflammation (drug toxicity, collagen vascular disease [Fig 22]) or radiation pneumonitis (pneumocyte atypia). Finally, OPP must be distinguished from other ILDs, particularly the organizing phase of DAD, which can show prominent intraluminal budding fibrosis and resemble OPP. DAD can be distinguished from OPP by the diffuse rather than patchy lung involvement (Figs 25A, 25B), often with reactive cytologic atypia (Fig 25B), organizing fibrosis causing interstitial thickening (Figs 25A, 25B), hyaline membranes (Fig 25A), and/or foci of acute inflammation and hemorrhage. In contrast to patients with DAD, patients with COP are usually ambulatory, and chest imaging shows patchy nodular infiltrates as described earlier (Fig 26).

Figure 26.

A, B, Diffuse alveolar damage and organizing pneumonia. Anteroposterior chest radiographs in a 66-year-old woman with biopsy-proved diffuse alveolar damage (A) shows diffuse consolidation bilaterally and in a 37-year-old man with biopsy-proved organizing pneumonia (B) showing patchy, nodular opacities bilaterally.

The cellular pattern of NSIP shows more prominent interstitial chronic inflammation than does the OPP associated with COP. OP foci are often present in NSIP, but they are focal and not the dominant histologic finding.14 Radiologic-pathologic correlation is important when biopsy specimens show an NSIP pattern, given that the CT scanning results may suggest other diagnoses such as COP or SOP (Fig 22). In other words, the CT scanning findings may reflect more accurately what the predominant lesion (OP or NSIP) is, even if the predominant lesion type may not be represented accurately in the biopsy specimens, including surgical lung biopsy specimens.

The diagnosis of COP or SOP should be excluded if a biopsy specimen with an OPP also shows accumulation of neutrophils or necrotizing granulomas. The main difference between the OPP and constrictive (or obliterative) bronchiolitis is the presence of polypoid intraluminal plugs of loose fibrosis in distal airspaces in the former in contrast to concentric dense fibrosis causing bronchiolar luminal narrowing in the latter (Fig 25F). If alveolar fibrinous exudates are conspicuous, the AFOP pattern should be considered.51,52 The OPP must be distinguished from a nonspecific reaction to an underlying lesion, such as an abscess (Figs 24C, 24D), neoplasm (Figs 25C, 25D), necrotizing granuloma, or acute pneumonia.

Algorithmic Approach

OP often presents a diagnostic challenge. Clinical features are nonspecific, with a respiratory manifestation generally characterized by cough and/or dyspnea, often within a setting of clinically significant constitutional symptoms. Complicating matters, OP’s signs and symptoms fully overlap with those of infection, malignancy, and complex connective tissue disease (eg, vasculitis). The diagnosis and management of OP are demanding and require a high degree of clinical suspicion, thoughtfulness regarding diagnostic testing, and persistence in follow-up. Nevertheless, the astute physician can make the diagnosis and manage the disease by considering the algorithm shown in Figure 1.

Placing OP in the differential diagnosis generally results from a clinical suspicion triggered by the combination of the patient’s persistent (often nonspecific) clinical features and abnormal chest imaging results. High-resolution CT (HRCT) scanning is strongly encouraged as the next step, given its sensitivity and frequent ability to help identify specific imaging patterns that can predict the underlying histopathologic pattern. By combining the clinical context with the HRCT imaging pattern, one can significantly narrow the differential diagnosis of entities that manifest with nonspecific symptoms and abnormal chest radiographs.

Although the clinical context is often nonspecific, defining it is critical because OP can manifest as a primary (or idiopathic) or secondary disorder. Clinical history, such as a recent respiratory infection, underlying systemic disorder, or treatment known to be associated with the development of OP, when combined with specific chest imaging patterns, can significantly increase the likelihood of making an accurate diagnosis.

At HRCT scanning, OP generally manifests in three predominant patterns: consolidation, nodular, and linear or reticular (see Radiologic Features). In each of these patterns, there are more typical and atypical findings associated with the presence of OP. Reviewing the clinical context and the HRCT scans in a formal multidisciplinary discussion may add a significant degree of diagnostic confidence, given the diagnostic complexity.

After this initial multidisciplinary discussion review, depending on one’s degree of diagnostic confidence, observation alone, empiric treatment, bronchoscopy with BAL, or tissue diagnosis (via a variety of techniques) may be appropriate strategies. Regardless of the plan, ongoing longitudinal follow-up of both clinical and chest imaging features is an absolute requirement.

Differential Diagnosis of OP

Although several imaging findings are typical of OP, no single finding or constellation of findings on CT scans is considered to be diagnostic of this condition.29 Therefore, one must keep in mind the differential diagnosis of the various radiologic findings that may be encountered on chest CT scans (Table 2).33,34, 35, 36

Consolidation is one of the more commonly encountered radiographic findings in cases of OP, although it is more likely to be secondary to infection in patients presenting with cough, dyspnea, and fever. When there is a persistent opacity or there are migratory opacities that are unresponsive to antibiotics, a differential diagnosis including OP must be considered.

Migratory opacities can indicate infection, vasculitis, and recurrent hemorrhage. Adenocarcinoma and low-grade B-cell lymphoma (especially associated with mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue) are considered in the absence of migratory opacities.1,24,25

Consolidation in OP is often peripheral.27,43,59 When peripheral consolidation is present, a number of entities may be considered, including chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, pulmonary lymphoma, pulmonary infarct, alveolar hemorrhage, viral infection, and aspiration pneumonia.34 Similarly, conditions that may mimic the peribronchovascular distribution of consolidation also often seen in OP35 include sarcoidosis, Kaposi sarcoma, follicular bronchiolitis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, lung cancer, and lymphoma.

OP also may manifest as a solitary nodule or multiple nodules or masses, which may raise concern for malignancy. The differential diagnosis of small, solitary nodules includes adenocarcinoma, especially in the upper lobe, and infection. The differential diagnosis for larger masses and/or foci of mass-like consolidation includes lymphoma, multicentric adenocarcinoma, and invasive fungal infections (especially in patients who are immunocompromised).20,25 Biopsies often are performed to evaluate for either primary bronchogenic carcinoma or metastatic disease when solitary or multiple nodules are present. In addition, infection and sarcoidosis may have similar radiologic findings.

GGO, either alone, or in a crazy-paving pattern, is another common chest CT scanning finding in OP. Once again, there is a broad differential diagnosis for such findings.37 The differential diagnosis includes alveolar proteinosis, infection (eg, Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia), sarcoidosis, exogenous lipoid pneumonia, and mucinous adenocarcinoma, among others, and nitrofurantoin-induced OP.25 Of current relevance, the typical appearance of COVID-19 has significant overlap with that of OP (Fig 27).60 e-Cigarette or vaping product use-associated lung injury is another entity with an increasing prevalence that may have findings identical to those of OP (Fig 28).61

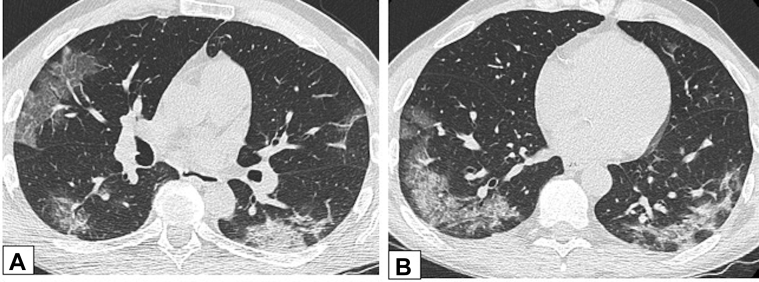

Figure 27.

A, B, COVID-19 and organizing pneumonia (OP). A 55-year-old man had confirmed COVID-19 with a typical imaging appearance on CT scans. Axial unenhanced CT scan images through the middle (A) and lower (B) lung zones show ground-glass opacification (GGO) with intralobular septal thickening in the right upper lobe and GGO and consolidative opacities in the periphery of each lower lobe, with a perilobular pattern in the left lower lobe. These findings are also typical of OP.

Figure 28.

e-Cigarette or vaping product use-associated lung injury (EVALI) and organizing pneumonia (OP). A 36-year-old man with a history of vaping tobacco presented with severe shortness of breath and hypoxemia. An unenhanced thin-section axial CT scan image shows large areas of consolidation and ground-glass opacification with superimposed intralobular lines bilaterally. Surgical lung biopsy results showed diffuse alveolar damage, thought to be due to EVALI. This pattern of imaging could also be seen with OP.

A perilobular pattern at CT scanning refers to poorly defined arcade-like and polygonal opacities bordering the interlobular septa, and they occasionally may be found in OP.33 However, this appearance may be encountered in infection, chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, lymphoproliferative disorders, and lung cancers as well.

The atoll sign, or reverse halo sign, is another CT scanning pattern potentially seen with OP. Although considered to be a suggestive finding, this is not a specific finding, because invasive fungal infections, chronic eosinophilic pneumonia, anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody-associated vasculitis, pulmonary infarct, COVID-19, sarcoidosis, lymphoma, and lepidic adenocarcinoma also may produce this pattern.59

Parenchymal bands may extend along the track of a bronchus toward the pleura in cases of OP.59 This appearance may be mistaken for scar due to infection or ARDS or may be seen in patients with asbestosis.

The typical imaging findings associated with OP on chest CT scans are not pathognomonic. Each has a broad differential diagnosis, often leading to a delay in diagnosis. However, when taken in combination with the patient’s history and clinical scenario, they may assist the physician in arriving at the correct diagnosis.

Conclusions

In this article, we provide a review of OP with a focus on radiologic and pathologic manifestations. An algorithmic guide for physicians to diagnose this clinical entity with its common subtypes is included. A high index of suspicion is required because of the nonspecific nature of OP, with neither clinical nor laboratory markers that are specific. HRCT scanning is the appropriate next diagnostic tool. There are no distinct radiologic findings at HRCT scanning that are diagnostic of OP. Bibasal, peribronchovascular, and/or peripheral consolidation are the most typical radiologic findings, present in 75% of cases.30 Other radiologic features include solitary or multiple nodules and linear or reticular findings. Histopathologic confirmation may be required by means of either surgical biopsy or bronchoscopy, BAL, and TBBX. Adequate tissue sampling, in correlation with radiologic findings, is essential for definite pathologic diagnosis. OPP on tissue biopsy specimens cannot be used to distinguish COP from SOP, although certain pathologic features may be suggestive of the underlying cause of SOP. OPP must be distinguished from other ILDs, particularly the organizing phase of DAD. Empiric therapy can be initiated if there are high clinical suspicion, typical radiologic findings, and high risk for an invasive procedure. A multidisciplinary approach correlating clinical, radiologic, and histologic findings is often required for proper diagnosis, management, and follow-up of OP.

Acknowledgments

Financial/nonfinancial disclosures: None declared.

References

- 1.Cottin V., Cordier J.F. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;33(5):462–475. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1325157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Davison A.G., Heard B.E., McAllister W.A., Turner-Warwick M.E. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonitis. Q J Med. 1983;52(207):382–394. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Epler G.R., Colby T.V., McLoud T.C., Carrington C.B., Gaensler E.A. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 1985;312(3):152–158. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501173120304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society International Multidisciplinary Consensus Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. This joint statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) was adopted by the ATS board of directors, June 2001 and by the ERS Executive Committee, June 2001. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165(2):277–304. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.2.ats01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Travis W.D., Costabel U., Hansell D.M., et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(6):733–748. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201308-1483ST. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spencer H. Interstitial pneumonia. Annu Rev Med. 1967;18:423–442. doi: 10.1146/annurev.me.18.020167.002231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Basset F., Ferrans V.J., Soler P., Takemura T., Fukuda Y., Crystal R.G. Intraluminal fibrosis in interstitial lung disorders. Am J Pathol. 1986;122(3):443–461. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cordier J.F. Organising pneumonia. Thorax. 2000;55(4):318–328. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.4.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gudmundsson G., Sveinsson O., Isaksson H.J., Jonsson S., Frodadottir H., Aspelund T. Epidemiology of organising pneumonia in Iceland. Thorax. 2006;61(9):805–808. doi: 10.1136/thx.2006.059469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alasaly K., Muller N., Ostrow D.N., Champion P., FitzGerald J.M. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia: a report of 25 cases and a review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 1995;74(4):201–211. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199507000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cordier J.F. Cryptogenic organising pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 2006;28(2):422–446. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00013505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.King T.E., Jr., Mortenson R.L. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonitis: the North American experience. Chest. 1992;102(1 suppl):8s–13s. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cordier J.F., Loire R., Brune J. Idiopathic bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia: definition of characteristic clinical profiles in a series of 16 patients. Chest. 1989;96(5):999–1004. doi: 10.1378/chest.96.5.999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Travis W.D., Matsui K., Moss J., Ferrans V.J. Idiopathic nonspecific interstitial pneumonia: prognostic significance of cellular and fibrosing patterns—survival comparison with usual interstitial pneumonia and desquamative interstitial pneumonia. Am J Surg Pathol. 2000;24(1):19–33. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200001000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fernández Pérez E.R., Travis W.D., Lynch D.A., et al. Diagnosis and evaluation of hypersensitivity pneumonitis: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest. 2021;160(2):e97–e156. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.03.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Enomoto N., Sumikawa H., Sugiura H., et al. Clinical, radiological, and pathological evaluation of “NSIP with OP overlap” pattern compared with NSIP in patients with idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Respir Med. 2020;174:106201. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Drakopanagiotakis F., Paschalaki K., Abu-Hijleh M., et al. Cryptogenic and secondary organizing pneumonia: clinical presentation, radiographic findings, treatment response, and prognosis. Chest. 2011;139(4):893–900. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lohr R.H., Boland B.J., Douglas W.W., et al. Organizing pneumonia: features and prognosis of cryptogenic, secondary, and focal variants. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(12):1323–1329. doi: 10.1001/archinte.157.12.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vasu T.S., Cavallazzi R., Hirani A., Sharma D., Weibel S.B., Kane G.C. Clinical and radiologic distinctions between secondary bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia and cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Respir Care. 2009;54(8):1028–1032. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bradley B., Branley H.M., Egan J.J., et al. Interstitial lung disease guideline: the British Thoracic Society in collaboration with the Thoracic Society of Australia and New Zealand and the Irish Thoracic Society. Thorax. 2008;63(suppl 5):v1–v58. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.101691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cordier J.F. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonitis: bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Clin Chest Med. 1993;14(4):677–692. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maldonado F., Daniels C.E., Hoffman E.A., Yi E.S., Ryu J.H. Focal organizing pneumonia on surgical lung biopsy: causes, clinicoradiologic features, and outcomes. Chest. 2007;132(5):1579–1583. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Poletti V., Cazzato S., Minicuci N., Zompatori M., Burzi M., Schiattone M.L. The diagnostic value of bronchoalveolar lavage and transbronchial lung biopsy in cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Eur Respir J. 1996;9(12):2513–2516. doi: 10.1183/09031936.96.09122513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Epler G.R. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia, 25 years: a variety of causes, but what are the treatment options? Expert Rev Respir Med. 2011;5(3):353–361. doi: 10.1586/ers.11.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luna C.M. C-reactive protein in pneumonia: let me try again. Chest. 2004;125(4):1192–1195. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.4.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baha A., Yıldırım F., Köktürk N., et al. Cryptogenic and secondary organizing pneumonia: clinical presentation, radiological and laboratory findings, treatment, and prognosis in 56 cases. Turk Thorac J. 2018;19(4):201–208. doi: 10.5152/TurkThoracJ.2018.18008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Baque-Juston M., Pellegrin A., Leroy S., Marquette C.H., Padovani B. Organizing pneumonia: what is it? A conceptual approach and pictorial review. Diagn Interv Imaging. 2014;95(9):771–777. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2014.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cordier J.F. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Clin Chest Med. 2004;25(4):727–738. doi: 10.1016/j.ccm.2004.06.003. vi-vii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee K.S., Kullnig P., Hartman T.E., Müller N.L. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia: CT findings in 43 patients. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1994;162(3):543–546. doi: 10.2214/ajr.162.3.8109493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Roberton B., Hansell D. Organizing pneumonia: a kaleidoscope of concepts and morphologies. Eur Radiol. 2011;21:2244–2254. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2191-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torrealba J.R., Fisher S., Kanne J.P., et al. Pathology-radiology correlation of common and uncommon computed tomographic patterns of organizing pneumonia. Hum Pathol. 2018;71:30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2017.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wells A.U. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;22(4):449–460. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-17387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ujita M., Renzoni E.A., Veeraraghavan S., Wells A.U., Hansell D.M. Organizing pneumonia: perilobular pattern at thin-section CT. Radiology. 2004;232(3):757–761. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2323031059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marchiori E., Hochhegger B., Zanetti G. Peripheral consolidation/ground-glass opacities. J Bras Pneumol. 2020;46(1) doi: 10.1590/1806-3713/e20190384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ko J.P., Girvin F., Moore W., Naidich D.P. Approach to peribronchovascular disease on CT. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2019;40(3):187–199. doi: 10.1053/j.sult.2018.12.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Godoy M.C., Viswanathan C., Marchiori E., et al. The reversed halo sign: update and differential diagnosis. Br J Radiol. 2012;85(1017):1226–1235. doi: 10.1259/bjr/54532316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rossi S.E., Erasmus J.J., Volpacchio M., Franquet T., Castiglioni T., McAdams H.P. “Crazy-paving” pattern at thin-section CT of the lungs: radiologic-pathologic overview. Radiographics. 2003;23(6):1509–1519. doi: 10.1148/rg.236035101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lebargy F., Picard D., Hagenburg J., et al. Micronodular pattern of organizing pneumonia: case report and systematic literature review. Medicine (Baltimore) 2017;96(3):e5788. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000005788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Akira M., Yamamoto S., Sakatani M. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia manifesting as multiple large nodules or masses. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170(2):291–295. doi: 10.2214/ajr.170.2.9456931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melloni G., Cremona G., Bandiera A., et al. Localized organizing pneumonia: report of 21 cases. Ann Thorac Surg. 2007;83(6):1946–1951. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2007.01.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhao F., Yan S.X., Wang G.F., et al. CT features of focal organizing pneumonia: an analysis of consecutive histopathologically confirmed 45 cases. Eur J Radiol. 2014;83(1):73–78. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zheng Z., Pan Y., Song C., et al. Focal organizing pneumonia mimicking lung cancer: a surgeon's view. Am Surg. 2012;78(1):133–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Johkoh T., Müller N.L., Ichikado K., Nakamura H., Itoh H., Nagareda T. Perilobular pulmonary opacities: high-resolution CT findings and pathologic correlation. J Thorac Imaging. 1999;14(3):172–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kim S.J., Lee K.S., Ryu Y.H., et al. Reversed halo sign on high-resolution CT of cryptogenic organizing pneumonia: diagnostic implications. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180(5):1251–1254. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.5.1801251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Churg A., Wright J.L., Bilawich A. Cicatricial organising pneumonia mimicking a fibrosing interstitial pneumonia. Histopathology. 2018;72(5):846–854. doi: 10.1111/his.13443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Woge M.J., Ryu J.H., Bartholmai B.J., Yi E.S. Cicatricial organizing pneumonia: a clinicopathologic and radiologic study on a cohort diagnosed by surgical lung biopsy at a single institution. Hum Pathol. 2020;101:58–63. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2020.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Todd N.W., Marciniak E.T., Sachdeva A., et al. Organizing pneumonia/non-specific interstitial pneumonia overlap is associated with unfavorable lung disease progression. Respir Med. 2015;109(11):1460–1468. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2015.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Travis W.D., Colby T.V., Koss M.N., Rosado-de-Christenson M.L., Müller N.L., King T.E., Jr. Non-Neoplastic Disorders of the Lower Respiratory Tract. American Registry of Pathology; Arlington, VA: 2002. Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia) pp. 82–88. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Domingo J.A., Pérez-Calvo J.I., Carretero J.A., Ferrando J., Cay A., Civeira F. Bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia: an unusual cause of solitary pulmonary nodule. Chest. 1993;103(5):1621–1623. doi: 10.1378/chest.103.5.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yousem S.A. Cicatricial variant of cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Hum Pathol. 2017;64:76–82. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2017.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Beasley M.B., Franks T.J., Galvin J.R., Gochuico B., Travis W.D. Acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia: a histological pattern of lung injury and possible variant of diffuse alveolar damage. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2002;126(9):1064–1070. doi: 10.5858/2002-126-1064-AFAOP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Feinstein M.B., DeSouza S.A., Moreira A.L., et al. A comparison of the pathological, clinical and radiographical, features of cryptogenic organising pneumonia, acute fibrinous and organising pneumonia and granulomatous organising pneumonia. J Clin Pathol. 2015;68(6):441–447. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2014-202626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kligerman S.J., Franks T.J., Galvin J.R. From the radiologic pathology archives: organization and fibrosis as a response to lung injury in diffuse alveolar damage, organizing pneumonia, and acute fibrinous and organizing pneumonia. Radiographics. 2013;33(7):1951–1975. doi: 10.1148/rg.337130057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Parambil J.G., Myers J.L., Ryu J.H. Histopathologic features and outcome of patients with acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis undergoing surgical lung biopsy. Chest. 2005;128(5):3310–3315. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.5.3310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Churg A., Müller N.L., Silva C.I., Wright J.L. Acute exacerbation (acute lung injury of unknown cause) in UIP and other forms of fibrotic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31(2):277–284. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000213341.70852.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Churg A., Wright J.L., Tazelaar H.D. Acute exacerbations of fibrotic interstitial lung disease. Histopathology. 2011;58(4):525–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2010.03650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Miyamoto A., Sharma A., Nishino M., Mino-Kenudson M., Matsubara O., Mark E.J. Expanded acceptance of acute exacerbation of nonspecific interstitial pneumonia, including 7 additional cases with detailed clinical pathologic correlation. Pathol Int. 2018;68(7):401–408. doi: 10.1111/pin.12676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Olopade C.O., Crotty T.B., Douglas W.W., Colby T.V., Sur S. Chronic eosinophilic pneumonia and idiopathic bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia: comparison of eosinophil number and degranulation by immunofluorescence staining for eosinophil-derived major basic protein. Mayo Clin Proc. 1995;70(2):137–142. doi: 10.4065/70.2.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zare Mehrjardi M., Kahkouee S., Pourabdollah M. Radio-pathological correlation of organizing pneumonia (OP): a pictorial review. Br J Radiol. 2017;90(1071):20160723. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20160723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Byrne D., O'Neill S.B., Müller N.L., et al. RSNA expert consensus statement on reporting chest CT findings related to COVID-19: interobserver agreement between chest radiologists. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2021;72(1):159–166. doi: 10.1177/0846537120938328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kligerman S., Raptis C., Larsen B., et al. Radiologic, pathologic, clinical, and physiologic findings of electronic cigarette or vaping product use-associated lung injury (EVALI): evolving knowledge and remaining questions. Radiology. 2020;294(3):491–505. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020192585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]