Abstract

The associations between blood pressure and cannabis use remain inconsistent. The purpose of our study was to examine gender stratified associations of cannabis use and blood pressure [systolic, diastolic blood pressure (BP), pulse pressure (PP)] levels among the general UK Biobank population based study. Among 91,161 volunteers of the UK Biobank population, cannabis use status was assessed by questionnaire and range as heavy, moderate, low and never users. Associations between cannabis use and BP were estimated using multiple gender linear regressions. In adjusted covariates models, lifetime heavy cannabis use was associated with decrease in both SBP, DBP and PP in both genders, but with a higher effect among women (for SBP in men, b = − 1.09 (0.27), p < 0.001; in women, b = − 1.85 (0.36), p < 0.001; for DBP in men, b = − 0.50 (0.15), p < 0.001; in women, b = − 0.87 (0.17), p < 0.001; and for PP in men, b = − 0.60 (0.20), p < 0.001; in women, b = − 0.97 (0.27), p < 0.001. Among men, lower SBP and DBP levels were observed with participants without dyslipidemia and lower PP in participants with high income levels. Among women, lower SBP, DBP and PP were observed with current smokers, moderate/low alcohol levels and participants without dyslipidemia. Current cannabis use was associated with lower SBP levels in men (b = − 0.63 (0.25), p = 0.012) and in women (b = − 1.17 (0.31), p < 0.001). Same results were observed for DBP and PP. Negative association between BP in men was found but not in women. The small association in BP differences between heavy users and never users remains too small to adopt cannabis-blood pressure public policy in clinical practice.

Subject terms: Cardiology, Risk factors

Introduction

Cannabis is the main used illicit drug. There is a worldwide trend toward to legalize cannabis, thus, it remains important to better understand the health impacts associated with its regular use. Recent studies have shown growing evidence in better cardiometabolic health associated with cannabis use1–3, whereas other studies suggested that cannabis use increases cardiovascular (CV) risks4–7. Nevertheless, these studies focused on limited populations leading to influence the impact of cannabis use on CV health8,9 and few studies have examined gender differences in cannabis use10,11. The use of medical cannabis is growing rapidly12, but on a limited knowledge regarding safety and efficacy in varied indications13. High values in blood pressure (BP) have been correlated with CV morbidity and mortality14. However, the association between BP and the use of cannabis remains inconsistent10,15. Nevertheless, a study has described that cannabis can lead to decrease BP due to vasodilatation along with tachycardia16. The cannabidiol (CBD), one of the major compound of cannabis, could reduce blood pressure17. CBD may have a sympathoinhibition action leading to decrease BP17. Old studies have focused on the relation between BP levels and cannabis use. Chronic use of cannabis was associated with decrease in BP18–20 leading to studies showing that endocannabinoid system could be a novel therapeutic way in hypertension treatment21. Moreover, a recent longitudinal studies showed a negative association with BP only in men22 whereas non-gender stratified cross-sectional studies showed positive association15. To date, the association between BP and cannabis use remains few studied in general populations. Thus, the purpose of our study was to examine gender stratified associations and interactions of the different lifetime aspects of cannabis use and BP levels among the general UK Biobank population.

Methods

UK Biobank population

The UK Biobank is a prospective cohort for the investigation, prevention, diagnosis and treatment of chronic diseases, such as CV diseases in adults. 502,478 Britons across 22 UK cities from the UK National Health Service Register were included between 2006 and 2010. The cohort was phenotyped and genotyped, by participants who responded to a questionnaire; a computer-assisted interview; physical and functional measures; and blood, urine, and saliva samples23. Data included socio-economic, behavior and lifestyle, mental health battery, clinical diagnoses and therapies, genetics, imaging and physiological biomarkers from blood and urine samples. The cohort protocol can be found in literature24.

Ethical considerations

All participants provided electronic informed consent and UK Biobank received ethical approval from the North-West Multi-center Research Ethics Committee (MREC) covering the whole of UK. The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the North West—Haydock Research Ethics Committee (protocol code: 21/NW/0157, date of approval: 21 June 2021). For details: https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/learn-more-about-uk-biobank/about-us/ethics.

Study population

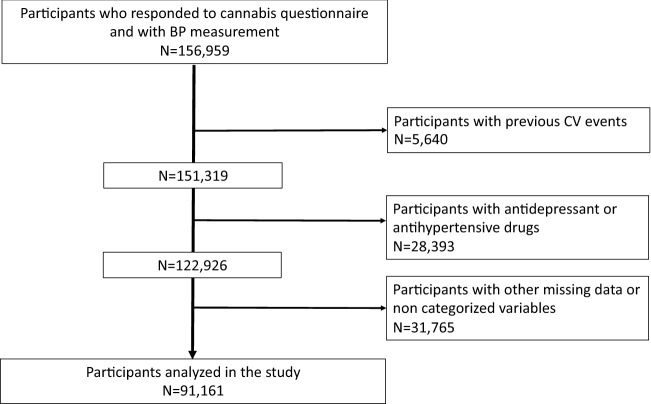

156,959 volunteers of the UK Biobank who responded to the question of cannabis use and with BP measurement were recruited. Of them, we excluded 65,798 for data missing and not categorized variables and excluding participants with antihypertensive drugs, antidepressant drugs and previous CV events (Supplementary Table 1). CV events were excluded from the analyses due to the inconsistent role of cannabis in CV disorders25. Antidepressant drugs use were excluded due to the association between cannabis use and depression26. The list of antidepressant drugs was available at27. We therefore analyzed 91,161 volunteers (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart.

Blood pressure measurement

Systolic and diastolic blood pressure (SBD, DBP) were measured twice at the assessment center by the use of an automated BP device (Omron 705 IT electronic blood pressure monitor; OMRON Healthcare Europe B.V. Kruisweg 577 2132 NA Hoofddorp), or manually by the use of a sphygmomanometer with an inflatable cuff in association with a stethoscope if the blood pressure device failed to measure the BP or if the largest inflatable cuff of the device did not fit around the individual’s arm28.

The participant was sitting in a chair for performing all the measures. The measures were carried out by nurses trained in performing BP measures29. Multiple available measures for one participant were averaged. The Omron 705 IT BP monitor has satisfied the Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation SP10 standard and was validated by the British Hypertension Society protocol, with an overall “A” grade for both SBP and DBP30. 5295 participants (5.8% of the study population) had a manual sphygmomanometer BP measurement. Nevertheless, automated devices measure lower BP in comparison to manual sphygmomanometers31, thus, and according to previous works for UK Biobank data32–34, we adjusted both SBP and DBP which were measured using the automated device using algorithms:

For SBP, we performed the following algorithm:

For DBP, we performed the following algorithm:

Pulse pressure (PP) was calculated as = SBP − DBP.

Cannabis use

Cannabis use was reported by self-reported questionnaire. Participants were asked about their cumulative lifetime cannabis use: ‘Have you taken cannabis (marijuana, grass, hash, ganja, blow, draw, skunk, weed, spliff, dope), even if it was a long time ago?’. Those who responded ‘no’ were classified as controls and those endorsing ‘yes’ options were classified as cannabis users. We separated these users into three groups according to categories reported in the questionnaire: those reporting initial cannabis use (‘yes, 1–2 times’, ‘yes, 3–10 times’) and continued cannabis use (‘yes, 11–100 times’: moderate users; ‘yes, more than 100 times’: heavy users). Cannabis users were asked “About how old were you when you last had cannabis?”. Cannabis user participants reporting this information and showing difference between age at inclusion and age of last cannabis use strictly inferior to 1 year were classified as “current users”, the others as “past users”. Among cannabis users, participants were asked about their cannabis frequencies use during taking: ‘Considering when you were taking cannabis most regularly, how often did you take it?’. The participants were classified into four groups, as: ‘every day’, ‘once a week or more, but not every day’, ‘once a month or more, but nor every week’, ‘less than once a month’.

Covariates

Diabetes status was defined on either receiving anti-diabetic medication or diabetes diagnosed by a doctor or a fasting glucose concentration ≥ 7 mmol/L. Dyslipidemia was defined as having a fasting plasma total-cholesterol or triglycerides level of ≥ 6.61 mmol/L (255 mg/dL) or > 1.7 mmol/L (150 mg/dL) respectively or having statins medication35. Hypertension was defined as systolic blood pressure (SBP) at least 140 mm Hg and/or diastolic BP (DBP) at least 90 mm Hg36. Medications were characterized by the question: “Do you regularly take any of the following medications?”.

Current tobacco smokers were defined as participants who responded “yes, on most or all days” at the question “do you smoke tobacco now”. CV diseases were defined by heart attack, angina and stroke, as diagnosed by a doctor and reported in questionnaires. Body mass index was calculated as weight (in kg) divided by height2 (meter), and categorized as high (BMI > 30 kg/m2), moderate (BMI between 25 and 30 kg/m2) and low (less than 25 kg/m2). Biological parameters were detailed in the UK Biobank protocol37. Education level was defined in three categories high (college or university degree), intermediate (A/AS levels or equivalent, O levels/GCSEs or equivalent), and low (none of the aforementioned)38. Income level was defined as, high level (‘greater than £52,000 per year’), moderate level (between £18,000 and £51,999 per year), and low level (‘less than £18,000 per year)39. Alcohol level consumption was defined as reported in questionnaire: high level (‘daily or almost daily’), moderate level (‘three or four times a week’, or ‘once or twice a week’, or ‘one to three times a month’), and low level (‘special occasions only’ or ‘never’).

Statistical analysis

Characteristics of the study population were described as the means with standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables. Categorical variables were described as numbers and proportions. Comparisons between groups were performed using Student’s test for continuous variables. Pearson’s χ2 test was performed for categorical variables. Statistical analyses were stratified on gender since blood pressure differs between men and women40 and a difference in cannabis consumption between gender41.

Firstly, this study explored the association between cumulative lifetime cannabis use and BP levels, secondly, the current or past use of cannabis consumption with BP and then, the frequency of cannabis use during taking with BP.

Associations between cannabis use and BP levels were examined with linear regression models computing regression coefficients (b) and their standard errors (SE). Firstly, gender models were adjusted for age. Secondly, gender models were adjusted for age, education, income level, alcohol consumption, tobacco habits, BMI categories, diabetes and dyslipidemia. “Never users” was considered as the referent group in the analyses. Subgroup analyses by education, income level, BMI, diabetes, dyslipidemia, alcohol and tobacco habits were performed. Interactions were examined by including simultaneously cannabis use status and one of the covariates, their interaction term and adjustment for all other covariates. Statistics were performed using SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Institute, Carry, NC). A p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Informed consent

Written informed consent has been obtained from the patients.

Results

Men presented higher BP levels compared to women (SBP: 137 (15) mmHg for men vs. 124 (16) mmHg for women p < 0.001 and DBP: 84 (8) mmHg for men vs. 79 (8) mmHg for women, p < 0.001), higher proportion of heavy cannabis users (4.37% vs 2.12%, p < 0.001), higher proportion of current cannabis users (3.91% vs. 2.20%, p < 0.001), higher proportion of current smokers (5.63% vs 4.29%, p < 0.001), and higher proportion of high alcohol level (28.47% vs 19.67%, p < 0.001).

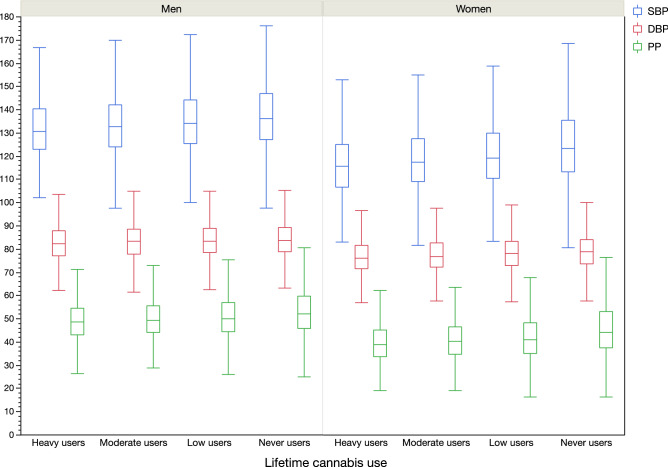

In comparison to never users, heavy users were younger, more likely current smokers and presented higher alcohol consumption, higher levels of income and education, but lower BMI levels in both genders (Table 1). The cannabis consumption frequency was associated with the status of users. Heavy users consumed cannabis every day for 47.76% of women, and for 46.90% for men while only and 0.21% for women and 0.16% for men among low users (p < 0.001). For both SBP, DBP and PP, heavy cannabis users presented lower levels of BP compared to never users (p < 0.001) (Table 1, Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population according to gender and cannabis use status [categorical variables with n and percentages, continuous variables with mean and standard deviation (SD)].

| Men | Heavy users N = 1762 (4.4%) |

Moderate users N = 2489 (6.2%) |

Low users N = 7316 (18.1%) |

Never users N = 28,799 (71.3%) |

P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI level | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| High | 234 | 13.28% | 374 | 15.03% | 1231 | 16.83% | 4927 | 17.11% | |

| Moderate | 811 | 46.03% | 1181 | 47.45% | 3581 | 48.95% | 14,408 | 50.03% | |

| Low | 717 | 40.69% | 934 | 37.53% | 2504 | 34.23% | 9464 | 32.86% | |

| Alcohol level | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| High | 647 | 36.72% | 868 | 34.87% | 2355 | 32.19% | 7624 | 26.47% | |

| Moderate | 954 | 54.14% | 1475 | 59.26% | 4553 | 62.23% | 18,290 | 63.51% | |

| Low | 161 | 9.14% | 146 | 5.87% | 408 | 5.58% | 2885 | 10.02% | |

| Income | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| High | 765 | 43.42% | 1351 | 54.28% | 3704 | 50.63% | 10,622 | 36.88% | |

| Moderate | 783 | 44.44% | 956 | 38.41% | 3080 | 42.10% | 15,244 | 52.93% | |

| Low | 214 | 12.15% | 182 | 7.31% | 532 | 7.27% | 2933 | 10.18% | |

| Education | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| High | 1038 | 58.91% | 1635 | 65.69% | 4566 | 62.41% | 13,999 | 48.61% | |

| Moderate | 529 | 30.02% | 612 | 24.59% | 1924 | 26.30% | 9144 | 31.75% | |

| Low | 195 | 11.07% | 242 | 9.72% | 826 | 11.29% | 5656 | 19.64% | |

| Diabetes | 55 | 3.12% | 66 | 2.65% | 234 | 3.20% | 1028 | 3.57% | 0.039 |

| Dyslipidemia | 972 | 55.16% | 1351 | 54.28% | 4082 | 55.80% | 16,238 | 56.38% | 0.159 |

| Tobacco habits | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Current smokers | 411 | 23.33% | 233 | 9.36% | 573 | 7.83% | 1054 | 3.66% | |

| No current smokers | 1351 | 76.67% | 2256 | 90.64% | 6743 | 92.17% | 27,745 | 96.34% | |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 132.5 | 14.02 | 134 | 14.14 | 135.5 | 14.77 | 137.8 | 15.37 | < 0.001 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 82.87 | 7.913 | 83.47 | 8.002 | 83.98 | 7.879 | 84.24 | 7.834 | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 526 | 29.89% | 822 | 33.04% | 2714 | 37.10% | 12,327 | 42.81% | < 0.001 |

| Pulse pressure, mmHg | 49.63 | 9.276 | 50.51 | 9.462 | 51.52 | 10.26 | 53.58 | 11.12 | < 0.001 |

| Age years | 50.24 | 6.825 | 51.28 | 6.933 | 53 | 7.382 | 56.47 | 7.756 | < 0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.24 | 3.743 | 26.47 | 3.701 | 26.78 | 3.791 | 26.83 | 3.682 | < 0.001 |

| Glucose, mmol/L | 4.978 | 0.957 | 4.93 | 0.919 | 5 | 1.009 | 5.017 | 1.057 | < 0.001 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 5.691 | 1.039 | 5.719 | 1.009 | 5.75 | 1.039 | 5.71 | 1.028 | 0.021 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 1.93 | 1.17 | 1.867 | 1.119 | 1.903 | 1.129 | 1.88 | 1.077 | 0.111 |

| Cannabis frequency | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Every day | 824 | 46.90% | 89 | 3.23% | 11 | 0.16% | – | – | |

| Once a week or more | 805 | 45.82% | 1017 | 41.06% | 185 | 2.62% | – | – | |

| Once a month or more | 107 | 6.09% | 770 | 31.09% | 493 | 6.97% | – | – | |

| Less than once a month | 21 | 1.20% | 610 | 24.63% | 6384 | 90.26% | – | – | |

| Cannabis users | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Current | 748 | 42.45% | 386 | 15.51% | 446 | 6.10% | 0 | 0% | |

| Past | 1014 | 57.55% | 2103 | 84.49% | 6870 | 93.90% | 0 | 0% | |

| Never | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 28,799 | 100.00% | |

| Time since last cannabis taking (years) for past users | 16.00 | 10.04 | 20.69 | 10.35 | 25.18 | 10.98 | – | – | < 0.001 |

| Women | Heavy users N = 1075 (2.1%) |

Moderate users N = 2265 (4.5%) |

Low users N = 7944 (15.6%) |

Never users N = 39,511 (77.8%) |

P value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BMI level | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| High | 114 | 10.60% | 280 | 12.36% | 1073 | 13.51% | 6347 | 16.06% | |

| Moderate | 354 | 32.93% | 647 | 28.57% | 2610 | 32.85% | 13,861 | 35.08% | |

| Low | 607 | 56.47% | 1338 | 59.07% | 4261 | 53.64% | 19,303 | 48.85% | |

| Alcohol level | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| High | 287 | 26.70% | 621 | 27.42% | 1980 | 24.92% | 7105 | 17.98% | |

| Moderate | 640 | 59.53% | 1429 | 63.09% | 5145 | 64.77% | 25,390 | 64.26% | |

| Low | 148 | 13.77% | 215 | 9.49% | 819 | 10.31% | 7016 | 17.76% | |

| Income | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| High | 379 | 35.26% | 977 | 43.13% | 3517 | 44.27% | 12,497 | 31.63% | |

| Moderate | 514 | 47.81% | 1063 | 46.93% | 3658 | 46.05% | 21,236 | 53.75% | |

| Low | 182 | 16.93% | 225 | 9.93% | 769 | 9.68% | 5778 | 14.62% | |

| Education | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| High | 717 | 66.70% | 1636 | 72.23% | 5216 | 65.66% | 18,068 | 45.73% | |

| Moderate | 286 | 26.60% | 532 | 23.49% | 2256 | 28.40% | 15,906 | 40.26% | |

| Low | 72 | 6.70% | 97 | 4.28% | 472 | 5.94% | 5537 | 14.01% | |

| Diabetes | 24 | 2.23% | 65 | 2.87% | 188 | 2.37% | 1033 | 2.61% | 0.402 |

| Dyslipidemia | 384 | 35.72% | 728 | 32.14% | 2774 | 34.92% | 16,626 | 42.08% | < 0.001 |

| Tobacco habits | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Current smokers | 239 | 22.23% | 209 | 9.23% | 555 | 6.99% | 1177 | 2.98% | |

| No current smokers | 836 | 77.77% | 2056 | 90.77% | 7389 | 93.01% | 38,334 | 97.02% | |

| Systolic BP, mmHg | 117.4 | 14.82 | 119.3 | 14.63 | 121.2 | 15.36 | 125.4 | 16.61 | < 0.001 |

| Diastolic BP, mmHg | 76.88 | 7.731 | 77.69 | 7.705 | 78.4 | 7.83 | 79.14 | 7.801 | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 103 | 9.58% | 258 | 11.40% | 1136 | 14.31% | 7983 | 20.22% | < 0.001 |

| Pulse pressure, mmHg | 40.47 | 9.85 | 41.61 | 9.952 | 42.77 | 10.67 | 46.26 | 12.28 | < 0.001 |

| Age years | 50.28 | 6.658 | 50.89 | 6.752 | 51.98 | 7.128 | 55.13 | 7.581 | < 0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 25.05 | 4.016 | 25.13 | 4.459 | 25.5 | 4.41 | 25.96 | 4.541 | < 0.001 |

| Glucose, mmol/L | 4.917 | 0.814 | 4.94 | 0.791 | 4.934 | 0.83 | 4.96 | 0.799 | 0.016 |

| Total cholesterol, mmol/L | 5.713 | 1.084 | 5.684 | 1.042 | 5.779 | 1.064 | 5.937 | 1.08 | < 0.001 |

| Triglycerides, mmol/L | 1.396 | 0.837 | 1.304 | 0.722 | 1.323 | 0.722 | 1.417 | 0.761 | < 0.001 |

| Cannabis frequency | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Every day | 512 | 47.76% | 81 | 3.62% | 16 | 0.21% | – | – | |

| Once a week or more | 499 | 46.55% | 969 | 43.30% | 202 | 2.66% | – | – | |

| Once a month or more | 49 | 4.57% | 717 | 32.04% | 569 | 7.49% | – | – | |

| Less than once a month | 12 | 1.12% | 471 | 21.05% | 6813 | 89.64% | – | – | |

| Cannabis users | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| Current | 396 | 36.84% | 320 | 14.13% | 402 | 5.06% | 0 | 0% | |

| Past | 679 | 63.16% | 1945 | 85.87% | 7542 | 94.94% | 0 | 0% | |

| Never | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 39,511 | 100.00% | |

| Time since last cannabis taking (years) for past users | 15.71 | 10.06 | 20.81 | 9.95 | 24.80 | 10.41 | – | – | < 0.001 |

BMI: body mass index, BP: blood pressure.

Figure 2.

Blood pressure parameters (SBP, DBP and PP) according to gender and cannabis use groups (p < 0.001 in all subgroups).

Compared to never users, heavy cannabis use was associated with lower SBP in men (b = − 1.25 (0.28), p < 0.001) in age-adjusted model. Adjustment for all covariates did not affect the negative association (b = − 1.09 (0.27), p < 0.001). Same results have been observed for DBP in men with a negative association in both models (after adjustment for covariates: b = − 0.50 (0.15), p < 0.001) and for PP in men (after adjustment for covariates: b = − 0.60 (0.20), p = 0.002 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Multiple gender linear regression models for the relationship between cannabis use and blood pressure (SBP, DBP and PP).

| Men | SBP | DBP | PP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta (SE) | P value | Beta (SE) | P value | Beta (SE) | P value | |||

| Cannabis | < 0.001 | Cannabis | < 0.001 | Cannabis | < 0.001 | |||

| Heavy users | − 1.09 (0.27) | < 0.001 | Heavy users | − 0.50 (0.15) | < 0.001 | Heavy users | − 0.60 (0.20) | 0.002 |

| Moderate users | − 0.17 (0.24) | 0.362 | Moderate users | − 0.09 (0.12) | 0.465 | Moderate users | − 0.08 (0.17) | 0.649 |

| Low users | 0.35 (0.17) | 0.040 | Low users | 0.22 (0.09) | 0.010 | Low users | 0.12 (0.12) | 0.313 |

| Never users | Ref. | Never users | Ref. | Never users | Ref. | |||

| Age | 0.43 (0.01) | < 0.001 | Age | 0.02 (0.01) | < 0.001 | Age | 0.42 (0.01) | < 0.001 |

| Current smokers | − 0.37 (0.16) | 0.019 | Current smokers | − 0.22 (0.08) | 0.008 | Current smokers | − 0.15 (0.11) | 0.179 |

| Alcohol level | < 0.001 | Alcohol level | < 0.001 | Alcohol level | < 0.001 | |||

| High | 1.88 (0.12) | < 0.001 | High | 1.03 (0.07) | < 0.001 | High | 0.85 (0.09) | < 0.001 |

| Moderate | − 0.02 (0.11) | 0.839 | Moderate | − 0.02 (0.06) | 0.749 | Moderate | − 0.001 (0.08) | 0.959 |

| Low | Ref. | Low | Ref. | Low | Ref. | |||

| Income | < 0.001 | Income | 0.025 | Income | < 0.001 | |||

| High | − 0.73 (0.12) | < 0.001 | High | − 0.07 (0.06) | 0.271 | High | − 0.67 (0.09) | < 0.001 |

| Moderate | 0.25 (0.11) | 0.023 | Moderate | 0.14 (0.06) | 0.015 | Moderate | 0.11 (0.08) | 0.158 |

| Low | Ref. | Low | Ref. | Low | Ref. | |||

| Education | < 0.001 | Education | < 0.001 | Education | < 0.001 | |||

| High | − 0.80 (0.10) | < 0.001 | High | − 0.33 (0.05) | < 0.001 | High | − 0.47 (0.07) | < 0.001 |

| Moderate | − 0.03 (0.11) | 0.767 | Moderate | − 0.01 (0.06) | 0.919 | Moderate | − 0.02 (0.07) | 0.732 |

| Low | Ref. | Low | Ref. | Low | Ref. | |||

| BMI | < 0.001 | BMI | < 0.001 | BMI | < 0.001 | |||

| High | 3.40 (0.13) | < 0.001 | High | 2.89 (0.07) | < 0.001 | High | 0.51 (0.09) | < 0.001 |

| Moderate | 0.31 (0.09) | 0.001 | Moderate | 0.03 (0.05) | 0.517 | Moderate | 0.28 (0.07) | < 0.001 |

| Low | Ref. | Low | Ref. | Low | Ref. | |||

| Diabetes | 0.24 (0.19) | 0.223 | Diabetes | − 0.64 (0.10) | < 0.001 | Diabetes | 0.89 (0.14) | < 0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 0.95 (0.07) | < 0.001 | Dyslipidemia | 0.60 (0.04) | < 0.001 | Dyslipidemia | 0.3( (0.05) | < 0.001 |

| Women | SBP | DBP | PP | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta (SE) | P value | Beta (SE) | P value | Beta (SE) | P value | |||

| Cannabis | < 0.001 | Cannabis | < 0.001 | Cannabis | < 0.001 | |||

| Heavy users | − 1.85 (0.36) | < 0.001 | Heavy users | − 0.87 (0.17) | < 0.001 | Heavy users | − 0.97 (0.26) | < 0.001 |

| Moderate users | − 0.38 (0.27) | 0.153 | Moderate users | − 0.09 (0.13) | 0.463 | Moderate users | − 0.29 (0.19) | 0.139 |

| Low users | 0.38 (0.19) | 0.046 | Low users | 0.32 (0.09) | < 0.001 | Low users | 0.06 (0.14) | 0.686 |

| Never users | Ref. | Never users | Ref. | Never users | Ref. | |||

| Age | 0.64 (0.01) | < 0.001 | Age | 0.04 (0.01) | < 0.001 | Age | 0.60 (0.01) | < 0.001 |

| Current smokers | − 1.05 (0.17) | < 0.001 | Current smokers | − 0.25 (0.08) | 0.002 | Current smokers | − 0.78 (0.09) | < 0.001 |

| Alcohol level | < 0.001 | Alcohol level | < 0.001 | Alcohol level | < 0.001 | |||

| High | 1.34 (0.12) | < 0.001 | High | 0.89 (0.06) | < 0.001 | High | 0.46 (0.09) | < 0.001 |

| Moderate | − 0.16 (0.09) | 0.083 | Moderate | − 0.16 (0.05) | < 0.001 | Moderate | − 0.001 (0.07) | 0.920 |

| Low | Ref. | Low | Ref. | Low | Ref. | |||

| Income | 0.017 | Income | 0.397 | Income | < 0.001 | |||

| High | − 0.30 (0.11) | 0.007 | High | 0.001 (0.05) | 0.934 | High | − 0.31 (0.08) | < 0.001 |

| Moderate | 0.11 (0.09) | 0.227 | Moderate | 0.06 (0.04) | 0.181 | Moderate | 0.05 (0.07) | 0.447 |

| Low | Ref. | Low | Ref. | Low | Ref. | |||

| Education | < 0.001 | Education | < 0.001 | Education | < 0.001 | |||

| High | − 1.09 (0.10) | < 0.001 | High | − 0.25 (0.05) | < 0.001 | High | − 0.85 (0.07) | < 0.001 |

| Moderate | 0.32 (0.10) | 0.001 | Moderate | 0.16 (0.05) | 0.001 | Moderate | 0.16 (0.15) | 0.024 |

| Low | Ref. | Low | Ref. | Low | Ref. | |||

| BMI | < 0.001 | BMI | < 0.001 | BMI | < 0.001 | |||

| High | 3.93 (0.13) | < 0.001 | High | 3.29 (0.06) | < 0.001 | High | 0.64 (0.09) | < 0.001 |

| Moderate | − 0.18 (0.10) | 0.071 | Moderate | − 0.26 (0.05) | < 0.001 | Moderate | 0.08 (0.07) | 0.271 |

| Low | Ref. | Low | Ref. | Low | Ref. | |||

| Diabetes | 0.61 (0.21) | 0.004 | Diabetes | − 0.53 (0.10) | < 0.001 | Diabetes | 1.15 (0.15) | < 0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia | 1.28 (0.07) | < 0.001 | Dyslipidemia | 0.68 (0.03) | < 0.001 | Dyslipidemia | 0.60 (0.05) | < 0.001 |

SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, PP pulse pressure, BMI body mass index.

In women, compared to never users, heavy cannabis use was associated with lower SBP (b = − 2.14 (0.36), p < 0.001) in age-adjusted model. Adjustment for all covariates did not affect the negative association (b = − 1.85 (0.36), p < 0.001). Same results have been observed for DBP in women with a negative association in both models (after adjustment for covariates: b = − 0.87 (0.17), p < 0.001) and for PP in women (after adjustment for covariates: b = − 0.97 (0.26), p < 0.001 (Table 2).

Table 3 showed the interaction results of the study for men. We found no interaction for men SBP between cannabis use and education (p = 0.720), income (p = 0.346), alcohol consumption (p = 0.263), BMI categories (p = 0.553). One interaction was observed with dyslipidemia (p = 0.019). The mean SBP difference for heavy cannabis users was lowered among dyslipidemia participants (b = − 0.88 (0.37), p = 0.018) compared to non-dyslipidemia participants (b = − 1.37 (0.41), p < 0.001). The interactions were significant for DBP between cannabis use and dyslipidemia (p = 0.004) with lower mean DBP difference among dyslipidemia participants. An interaction between alcohol level and cannabis use was observed (p = 0.003) for DBP among men. The mean DBP difference for heavy cannabis users was significant and higher among high alcohol consumption (b = − 0.78 (0.24), p = 0.001). The mean PP difference for heavy cannabis users was lowered among high income level (p for interaction = 0.022, with b = − 0.43 (0.27), p = 0.019).

Table 3.

Associations of heavy cannabis users* and blood pressure levels among men, using linear regression models.

| Men | SBP | DBP | PP | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Age adjusted Estimated difference | Covariate adjusted Estimated difference | Interaction** | Age adjusted Estimated difference | Covariate adjusted Estimated difference | Interaction** | Age adjusted Estimated difference | Covariate adjusted Estimated difference | Interaction** | ||||||

| Current smokers | − 2.76 (0.64) | < 0.001 | − 2.25 (0.63) | < 0.001 | 0.843 | − 1.45 (0.35) | < 0.001 | − 1.00 (0.40) | 0.003 | 0.513 | − 1.30 (0.43) | 0.003 | − 1.24 (0.44) | 0.005 | 0.563 |

| No current smokers | − 0.95 (0.31) | 0.002 | − 0.95 (0.31) | 0.002 | − 0.52 (0.17) | 0.002 | − 0.46 (0.16) | 0.004 | − 0.43 (0.22) | 0.048 | − 0.49 (0.22) | 0.026 | |||

| Alcohol | 0.263 | 0.003 | 0.813 | ||||||||||||

| High | − 1.67 (0.48) | < 0.001 | − 1.56 (0.48) | < 0.001 | − 0.97 (0.24) | < 0.001 | − 0.78 (0.24) | 0.001 | − 0.69 (0.33) | 0.039 | − 0.78 (0.34) | 0.020 | |||

| Moderate | − 1.10 (0.37) | 0.003 | − 0.77 (0.37) | 0.034 | − 0.57 (0.19) | 0.004 | − 0.31 (0.19) | 0.099 | − 0.53 (0.26) | 0.038 | − 0.45 (0.25) | 0.079 | |||

| Low | − 1.61 (0.92) | 0.081 | − 1.18 (0.91) | 0.193 | − 1.19 (0.51) | 0.019 | − 0.73 (0.48) | 0.134 | − 0.42 (0.66) | 0.519 | − 0.46 (0.66) | 0.490 | |||

| Income | 0.346 | 0.998 | 0.022 | ||||||||||||

| High | − 1.05 (0.40) | 0.008 | − 0.86 (0.40) | 0.029 | − 0.56 (0.22) | 0.011 | − 0.42 (0.21) | 0.047 | − 0.50 (0.27) | 0.058 | − 0.43 (0.27) | 0.019 | |||

| Moderate | − 1.34 (0.43) | 0.002 | − 1.03 (0.42) | 0.014 | − 0.77 (0.22) | < 0.001 | − 0.50 (0.21) | 0.020 | − 0.56 (0.30) | 0.061 | − 0.53 (0.30) | 0.077 | |||

| Low | − 1.93 (0.89) | 0.031 | − 1.73 (0.90) | 0.053 | − 1.00 (0.46) | 0.030 | − 0.81 (0.45) | 0.071 | − 0.93 (0.63) | 0.141 | − 0.91 (0.64) | 0.154 | |||

| Education | 0.720 | 0.565 | 0.897 | ||||||||||||

| High | − 1.22 (0.36) | < 0.001 | − 1.15 (0.35) | 0.001 | − 0.55 (0.19) | 0.005 | − 0.44 (0.19) | 0.019 | − 0.67 (0.25) | 0.006 | − 0.72 (0.24) | 0.004 | |||

| Moderate | − 1.09 (0.51) | 0.032 | − 0.81 (0.51) | 0.107 | − 0.83 (0.27) | 0.002 | − 0.57 (0.26) | 0.030 | − 0.26 (0.36) | 0.470 | − 0.24 (0.36) | 0.053 | |||

| Low | − 1.81 (0.81) | 0.033 | − 1.55 (0.85) | 0.068 | − 1.05 (0.44) | 0.017 | − 0.66 (0.43) | 0.128 | − 0.76 (0.61) | 0.212 | − 0.89 (0.61) | 0.148 | |||

| Diabetes | − 1.59 (1.58) | 0.316 | − 1.54 (1.61) | 0.334 | 0.986 | − 0.40 (0.83) | 0.631 | − 0.46(0.81) | 0.576 | 0.357 | − 1.19 (1.20) | 0.319 | − 1.09 (1.21) | 0.369 | 0.662 |

| No diabetes | − 1.25 (0.28) | < 0.001 | − 1.06 (0.24) | 0.472 | − 0.79 (0.15) | < 0.001 | − 0.49 (0.15) | < 0.001 | − 0.55 (0.19) | 0.005 | − 0.47 (0.19) | 0.004 | |||

| Dyslipidemia | − 1.13 (0.37) | 0.002 | − 0.88 (0.37) | 0.018 | 0.019 | − 0.72 (0.19) | < 0.001 | − 0.42 (0.19) | 0.029 | 0.004 | − 0.42 (0.26) | 0.113 | − 0.45 (0.26) | 0.085 | 0.298 |

| No dyslipidemia | − 1.46 (0.41) | < 0.001 | − 1.37 (0.41) | < 0.001 | − 0.71 (0.22) | 0.001 | − 0.62 (0.23) | 0.004 | − 0.77 (0.28) | 0.007 | − 0.74 (0.29) | 0.010 | |||

| BMI | 0.553 | 0.159 | 0.913 | ||||||||||||

| High | − 0.15 (0.48) | 0.763 | − 0.18 (0.76) | 0.817 | − 0.14 (0.40) | 0.735 | − 0.07 (0.40) | 0.861 | − 0.03 (0.54) | 0.954 | − 0.11 (0.45) | 0.844 | |||

| Moderate | − 0.78 (0.25) | 0.002 | − 1.17 (0.39) | 0.003 | − 0.61 (0.21) | 0.003 | − 0.61 (0.21) | 0.003 | − 0.52 (0.28) | 0.067 | − 0.55 (0.28) | 0.049 | |||

| Low | − 0.57 (0.27) | 0.037 | − 1.37 (0.44) | 0.002 | − 0.36 (0.22) | 0.108 | − 0.52 (0.23) | 0.021 | − 0.64 (0.30) | 0.035 | − 0.84 (0.31) | 0.006 | |||

SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, PP pulse pressure, BMI body mass index.

*Referent group is never user of cannabis.

**Interaction were performed among covariate adjusted models.

Covariates adjusted estimated differences were adjusted for age, education, income level, tobacco habits, alcohol consumption, BMI categories, dyslipidemia, and diabetes, except for the stratified variables.

Table 4 showed the interaction results of the study for women. We found significant interactions for SBP between cannabis use and tobacco status (p = 0.017) and alcohol level (p = 0.039). The mean SBP difference for heavy cannabis users was higher among high current smokers (b = − 2.71 (0.76), p < 0.001) but lower among high level of alcohol (b = − 1.38 (0.71), p = 0.043). We found for women the same interactions for DBP between cannabis use and tobacco status (p = 0.031) and alcohol level (p = 0.008) in which the DBP difference for heavy cannabis users was higher among current smokers (b = − 1.49 (0.39), p < 0.001) but with no significant association with high alcohol level (only significant association with moderate alcohol level, p < 0.001). An interaction, among women, between income level and cannabis use was observed (p = 0.041) with higher DBP difference among high income level (b = − 1.25 (0.29), p < 0.001). Only on interaction between dyslipidemia and cannabis use was shown among women for PP, in which heavy cannabis users had lower mean PP difference (b = − 0.92 (0.30), p = 0.003).

Table 4.

Associations of heavy cannabis users (Referent group is never user of cannabis) and blood pressure levels among women, using linear regression models.

| WOMEN | SBP | DBP | PP | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | Age adjusted Estimated difference | Covariate adjusted Estimated difference | Interaction* | Age adjusted Estimated difference | Covariate adjusted Estimated difference | Interaction* | Age adjusted Estimated difference | Covariate adjusted Estimated difference | Interaction* | ||||||

| Current smokers | − 2.95 (0.78) | < 0.001 | − 2.71 (0.76) | < 0.001 | 0.017 | − 1.76 (0.41) | < 0.001 | − 1.49 (0.39) | < 0.001 | 0.031 | − 1.21 (0.53) | 0.025 | − 1.21 (0.54) | 0.025 | 0.059 |

| No current smokers | − 1.88 (0.41) | < 0.001 | − 1.78 (0.41) | < 0.001 | − 0.83 (0.21) | < 0.001 | − 0.75 (0.19) | < 0.001 | − 1.06 (0.29) | < 0.001 | − 1.03 (0.29) | < 0.001 | |||

| Alcohol | 0.039 | 0.008 | < 0.001 | 0.407 | |||||||||||

| High | − 1.77 (0.72) | 0.014 | − 1.38 (0.71) | 0.043 | 0.76 (0.36) | 0.035 | − 0.61 (0.35) | 0.083 | − 1.01 (0.51) | 0.049 | − 0.77 (0.51) | 0.132 | |||

| Moderate | − 2.16 (0.46) | < 0.001 | − 2.00 (0.46) | < 0.001 | − 1.06 (0.23) | < 0.001 | − 0.98 (0.22) | < 0.001 | − 1.09 (0.33) | < 0.001 | − 1.01 (0.32) | 0.002 | |||

| Low | − 2.87 (1.02) | 0.005 | − 2.15 (0.99) | 0.031 | − 1.25 (0.52) | 0.017 | − 0.88 (0.49) | 0.072 | − 1.63 (0.72) | 0.025 | − 1.26 (0.72) | 0.081 | |||

| Income | 0.489 | < 0.001 | 0.041 | < 0.001 | 0.377 | ||||||||||

| High | − 0.83 (0.11) | < 0.001 | − 2.61 (0.57) | < 0.001 | − 1.30 (0.30) | < 0.001 | − 1.25 (0.29) | < 0.001 | − 1.47 (0.39) | < 0.001 | − 1.36 (0.40) | < 0.001 | |||

| Moderate | 0.23 (0.09) | 0.019 | − 1.52 (0.52) | 0.004 | − 0.93 (0.26) | < 0.001 | − 0.80 (0.25) | 0.002 | − 0.98 (0.38) | 0.011 | − 0.72 (0.38) | 0.060 | |||

| Low | Ref. | − 0.98 (0.94) | 0.298 | − 0.75 (0.47) | 0.109 | − 0.34 (0.45) | 0.446 | − 0.97 (0.69) | 0.166 | − 0.63 (0.70) | 0.363 | ||||

| Education | 0.997 | < 0.001 | 0.308 | < 0.001 | 0.742 | ||||||||||

| High | − 1.93 (0.43) | < 0.001 | − 1.86 (0.43) | < 0.001 | − 0.80 (0.22) | < 0.001 | − 0.77 (0.22) | < 0.001 | − 1.13 (0.30) | < 0.001 | − 1.09 (0.31) | < 0.001 | |||

| Moderate | − 2.23 (0.71) | 0.002 | − 1.86 (0.70) | 0.008 | − 1.12 (0.35) | 0.002 | − 0.94 (0.34) | 0.005 | − 1.11 (0.51) | 0.028 | − 0.91 (0.51) | 0.074 | |||

| Low | − 2.94 (1.48) | 0.047 | − 2.06 (1.46) | 0.159 | − 2.13 (0.72) | 0.003 | − 1.67 (0.69) | 0.016 | − 0.81 (1.09) | 0.456 | − 0.39 (1.09) | 0.719 | |||

| Diabetes | − 0.23 (2.47) | 0.924 | − 0.29 (2.41) | 0.902 | 0.639 | − 1.18 (1.24) | 0.342 | − 1.34 (1.17) | 0.250 | 0.295 | 0.95 (1.89) | 0.604 | 1.04 (1.83) | 0.567 | 0.711 |

| No diabetes | − 2.18 (0.36) | < 0.001 | − 1.89 (0.36) | < 0.001 | − 0.99 (0.18) | < 0.001 | − 0.86 (0.18) | < 0.001 | − 1.19 (0.26) | < 0.001 | − 1.03 (0.26) | < 0.001 | |||

| Dyslipidemia | − 2.47 (0.63) | < 0.001 | − 1.86 (0.63) | 0.003 | 0.411 | − 1.07 (0.31) | < 0.001 | − 0.77 (0.30) | 0.011 | 0.648 | − 1.06 (0.30) | < 0.001 | − 0.92 (0.30) | 0.003 | 0.029 |

| No dyslipidemia | − 2.12 (0.43) | < 0.001 | − 1.87 (0.43) | < 0.001 | − 1.06 (0.22) | < 0.001 | − 0.95 (0.22) | < 0.001 | − 1.40 (0.46) | 0.003 | − 1.09 (0.46) | 0.018 | |||

| BMI | 0.209 | 0.490 | 0.152 | ||||||||||||

| High | − 2.71 (1.10) | 0.014 | − 2.65 (1.10) | 0.016 | − 1.43 (0.54) | 0.008 | − 1.41 (0.54) | 0.009 | − 1.28 (0.81) | 0.116 | − 1.23 (0.81) | 0.129 | |||

| Moderate | − 1.47 (0.62) | 0.019 | − 1.21 (0.68) | 0.055 | − 0.84 (0.31) | 0.006 | − 0.79 (0.31) | 0.009 | − 0.62 (0.45) | 0.168 | − 0.41 (0.45) | 0.373 | |||

| Low | − 2.12 (0.35) | < 0.001 | − 2.07 (0.47) | < 0.001 | − 0.78 (0.23) | < 0.001 | − 0.82 (0.23) | < 0.001 | − 1.35 (0.33) | < 0.001 | − 1.25 (0.33) | < 0.001 | |||

SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, PP pulse pressure, BMI body mass index.

*Interaction were performed among covariate adjusted models.

Covariates adjusted estimated differences were adjusted for age, education, income level, tobacco habits, alcohol consumption, BMI categories, dyslipidemia, and diabetes, except for the stratified variables.

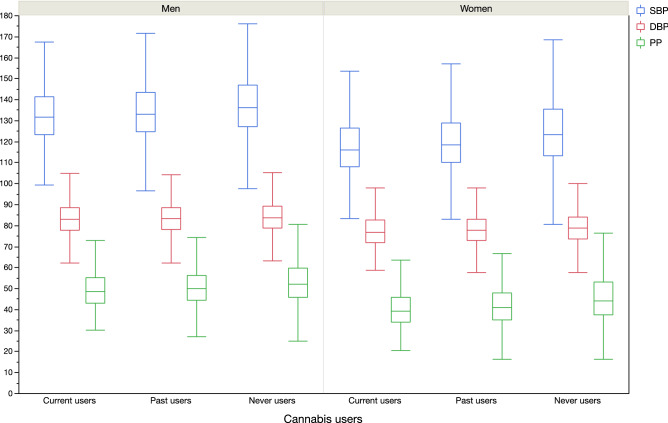

In men, compared to never users, current cannabis use was associated with lower SBP (b = − 071 (0.25), p = 0.005) in age-adjusted model. Adjustment for all covariates did not affect the negative association (b = − 0.63 (0.25), p = 0.012). In women, compared to never users, current cannabis use was associated with lower SBP (b = − 1.35 (0.31), p < 0.001) in age-adjusted model. Adjustment for all covariates did not affect the negative association (b = − 1.17 (0.31), p < 0.001). Same results were observed for DBP and PP (Table 5, Fig. 3).

Table 5.

Gender linear regression models for the relationship between current or past cannabis use and blood pressure (SBP, DBP and PP).

| SBP | DBP | PP | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age-adjusted | P value | All-covariates-adjusted* | P value | Age-adjusted | P value | All-covariates-adjusted* | P value | Age-adjusted | P value | All-covariates-adjusted* | P value | |

| Men | ||||||||||||

| Cannabis | ||||||||||||

| Current users | − 0.71 (0.25) | 0.005 | − 0.63 (0.25) | 0.012 | − 0.37 (0.13) | 0.006 | − 0.25 (0.13) | 0.044 | − 0.34 (0.18) | 0.045 | − 0.38 (0.18) | < 0.001 |

| Past users | − 0.13 (0.16) | 0.406 | − 0.08 (0.16) | 0.592 | − 0.01 (0.09) | 0.886 | − 0.01 (0.08) | 0.942 | − 0.15 (0.11) | 0.193 | − 0.08 (0.06) | 0.035 |

| Never users | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | |||||||

| Women | ||||||||||||

| Cannabis | ||||||||||||

| Current users | − 1.35 (0.31) | < 0.001 | − 1.17 (0.31) | < 0.001 | − 0.59 (0.16) | < 0.001 | − 0.54 (0.15) | < 0.001 | − 0.76 (0.22) | < 0.001 | − 0.63 (0.22) | < 0.001 |

| Past users | − 0.48 (0.19) | 0.010 | − 0.29 (0.18) | 0.120 | − 0.04 (0.09) | 0.641 | − 0.05 (0.09) | 0.609 | − 0.44 (0.13) | < 0.001 | − 0.33 (0.13) | 0.012 |

| Never users | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | Ref. | ||||||

SBP systolic blood pressure, DBP diastolic blood pressure, PP pulse pressure, BMI body mass index.

*model adjusted for age, education, income level, alcohol consumption, tobacco habits, BMI categories, diabetes and dyslipidemia.

Figure 3.

Blood pressure parameters (SBP, DBP and PP) according to gender and cannabis use groups (p < 0.001 in all subgroups).

In our study, we showed that no association and no interaction between frequencies of cannabis use during taking cannabis and blood pressure (SBP, DBP, PP) levels in both genders among the different groups of cannabis users (Supplementary Table 2).

Sensitivity analysis

When considering the overall study population, heavy cannabis users showed lower SBP (b = − 1.14 (0.23), p < 0.001, with a gender interaction effect with cannabis use (p for interaction < 0.001). Same results were observed for DBP (b = − 0.68 (0.11), p < 0.001, with a p for interaction = 0.008 between gender and cannabis use), and for PP (b = − 0.74 (0.16), p < 0.001, with a p for interaction < 0.001). Same results were observed in overall study population for current cannabis use with SBP (b = − 0.73 (0.20), p < 0.001), with DBP (b = − 0.36 (0.10), p < 0.001) and with PP (b = − 0.37 (0.14), p = 0.009), with a p for interaction with gender, p < 0.001). This interaction between gender and cannabis use allows us to compare the BP effects of cannabis use between gender.

To consider the possible effect of white coat hypertension, a sensitivity analysis was performed only on the second BP measure. Spearman correlation between first and second SBP measures was very high (measure one: 131 (18) mmHg, measure two: 129 (17) mmHg, ρ = 0.895, p < 0.001), as between first and second DBP measures (measure on 81 (9) mmHg, measure two: 81 (8) mmHg, ρ = 0.869, p < 0.001). The results remained consistent for both SBP, DBP and PP when only considering second BP measurement (Supplemental Table 3).

Discussion

The main finding of our study was that heavy cannabis use was associated with lower BP (i.e. SBP, DBP, PP) levels in both genders but in a higher manner in women (p for interaction < 0.001 in overall study population). It seems that a lifetime cannabis use was mainly associated with decrease in BP, as observed with smoking pack year42.

Cannabis joint-years

As observed in our study the potential impact of time effect of cannabis use (as number of times participants took cannabis), future studies could investigated the role of cannabis with BP through a cannabis joint-years. Pack-years, for tobacco, investigates the combination of information about smoking duration and intensity43. A cumulative joint-years could be estimated by the equivalent of daily cannabis use for one year. At this effect, recent studies showed that the cumulative consumption of cannabis was not associate with decline in health compared to tobacco smoking22. Nevertheless, the cannabinoid system remains complex and it remains unclear if it can associated with worsening or improvement of metabolic health44.

Cannabis use and BP

Recent studies have suggested a strongly association between cannabis use and SBP than cannabis use and DBP45,46. Nevertheless, the relationship between cannabis and BP remains unclear. Prospective studies have found that the increase in SBP observed for cannabis use could be mainly cofounded by a higher alcohol consumption in cannabis users47. In our study, we have shown an interaction between cannabis use and alcohol consumption among women, which could partly explain the higher decrease in SBP and DBP in women compared to men. In contrast, men presented an interaction between alcohol and cannabis for PP. PP is a marker of CV risk factors and arterial stiffness48. This relationship allows us to the possibility of cannabis use against arterial stiffness. Other recent studies have shown a better cardio-metabolic profile of cannabis users compared to non-users44,49,50, this could be added by the interaction observed in our study between dyslipidemia and cannabis use for SBP and DBP among men and for PP among women.

Physiological relationship between BP and cannabis

Cannabinoids (CBs) are compounds of the Cannabis sativa plant. There are over 80 types of phytocannabinoids. The THC (Delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol) is responsible for the psychoactive properties of cannabis51 while the other main phytocannainoid is the cannabidiol (CBD) which does not have psychoactive properties but interesting properties in several diseases52. CBD presented vasorelaxation actions in arteries53. Recent studies showed that CBD could reduce blood pressure17. This effect may be secondary to the anxiolytic properties of CBD. CBD was also responsible for endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation in mesenteric arteries. CBD could have a sympathoinhibition action leading to decrease BP17. Endocannabinoid system can activate CB1 receptor which increases cardiac contractile performance and reduces peripheral vascular resistance leading to lowered BP21. However, studies conducted in blood vessel vasomotion remain inconsistent. Even if THC may be associated with vasorelaxation, THC could enhance methoxamine-induced vasoconstriction25. These results may suggest that THC present different effects on vessels depending on central or peripheral properties of arteries. Nevertheless, the abrupt cessation of cannabis use was associated with increase in BP54.

Alcohol consumption and cannabis use with BP levels

Prospective studies showed a possible cofounding action of alcohol consumption on the association between cannabis use and systolic BP47. In our study, high levels of alcohol consumption and current tobacco smoking showed associations with BP in both genders. However, interactions between heavy cannabis use with alcohol consumption and tobacco were observed only in women but not in men (except for DBP in men). This showed that the effect of heavy cannabis use on BP was higher among current women smokers than among no current women smokers. However, the effect of heavy cannabis use on BP was higher among low women alcohol users than among high women alcohol users. Alcohol consumption was considered as a main confounding factor of cannabis use impact55. The use of both cannabis and alcohol was the most frequent combination observed worldwide among cannabis users47. However, pharmacokinetic interactions have not been yet explained in depth. Nevertheless, cannabis in association with alcohol is a common administration route. A recent study has shown that high alcohol consumption was associated with increased blood THC concentration55. Other studies provided limited pharmacokinetics information for cannabis and alcohol due to their controlled-administration experiments56. Nevertheless, the mode of administration could be important in the impact of BP levels. Alcohol before smoking cannabis should not affect THC blood levels57. However, blood THC level was lower over 4 h after smoking with alcohol than placebo57 but this effect did not consider the individual cannabis use history of participants.

Gender difference for cannabis use and BP

Gender difference effects of cannabis use have been observed in our study for BP levels with lower BP effect of heavy cannabis consumption in women compared to men. When considering all the study population, an interaction was observed between gender and cannabis use (p for interaction < 0.001, after adjustment for all covariates). Previous studies presented gender differences in frequency of cannabis use and cardiovascular response10. Some evidence from animal models may suggest that gonadal hormones are implicated in the cannabinoid modulation of metabolism balance and can influence cannabinoid receptor density in a gender-dependent manner58. Sensitivity of cannabinoid receptors were differently modulated by estrogen and testosterone probably explaining the gender differences observed. However, for the similar time duration of consumption, a previous study have shown that women smoked fewer cigarettes of cannabis compared to men and received low concentrations levels of THC in blood due to different titrate of amount cannabis smoked in response to different cannabis potencies59. However, higher effect has been observed among women in our study, the endocannabinoid system could mainly affect this relation even if women may have lower titrate in cannabis smoked use.

Strengths and limitations

The major strength of the study is the large sample size of the UK Biobank cohort. The cross-sectional design can limit the causality relationship, thus reverse causation can’t be ruled out. The UK Biobank study presented a low 5.5% rate of response leading to the involvement of possible participants bias. However, given the large sample size and high internal validity, these limitations may unlikely affect the observed associations60,61. Moreover, the study investigation was focused on middle-aged UK participants, so our results could not be generalized to other age and ethnic populations. Nevertheless, the UK Biobank used standardized protocols to collect data, such as BP measurements. This standardization ensures replication of data collection for all participants regardless of when, where and by whom they are performed and adds external validity to our findings. Nevertheless, our study shows many limitations: socio-economic data, medical history and comorbidities were collected by self-reported questionnaires or by physician assertion during medical examination in health centers. Data of the UK Biobank were collected from 2006 to 2010. This could bias the generalization of the results to actual existing cannabis use patterns and risks. Cannabis use was self-reported by questionnaire and not by urine or blood testing. Nevertheless, the validity of self-reported cannabis use presented an overall congruence estimated at 89.8% compared to drug tests of urine specimens62. In our study, no data on the frequency of cannabis use around the 30 days prior to the interview was established and hence it is difficult to distinguish whether the interrelationship of cannabis use and BP is of a short term or of a chronic nature. Moreover, no data indicated current, recent or past use and should limit the results observed. No clear data were covered for THC estimation or CBD considerations. Moreover, no data were presented for smoking method, as vaping vs oral. These lack of information should be a major limitation in this study and should be investigated in further studies.

Conclusion

We found a negative association between BP and cannabis use in both genders but with a higher manner in women. As observed for tobacco, it would be interested to develop a pack year cannabis smoking to clearly investigated the relationship between cannabis time effect consumption (as cannabis joint-years) and BP. Nevertheless, the small association in BP differences between heavy cannabis users and never users or between current cannabis users and never users remain too small to adopt cannabis-blood pressure policy in clinical practice. Longitudinal studies are needed in general populations and then, in hypertensive patients to highlight the potential lowered BP effect of cannabis in a medical use.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

Conceptualization, A.V.; methodology, A.V.; formal analysis, A.V.; writing—original draft preparation, A.V.; The author has read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Competing interests

The author declares no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-22841-6.

References

- 1.Waterreus A, et al. Metabolic syndrome in people with a psychotic illness: Is cannabis protective? Psychol. Med. 2016;46:1651–1662. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715002883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vidot DC, et al. Metabolic syndrome among Marijuana users in the United States: An analysis of national health and nutrition examination survey data. Am. J. Med. 2016;129:173–179. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schoeler T, et al. Effects of continuation, frequency, and type of cannabis use on relapse in the first 2 years after onset of psychosis: an observational study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3:947–953. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30188-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Thomas G, Kloner RA, Rezkalla S. Adverse cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and peripheral vascular effects of marijuana inhalation: What cardiologists need to know. Am. J. Cardiol. 2014;113:187–190. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.09.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mittleman MA, Lewis RA, Maclure M, Sherwood JB, Muller JE. Triggering myocardial infarction by marijuana. Circulation. 2001;103:2805–2809. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.23.2805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolff V, et al. Cannabis-related stroke: Myth or reality? Stroke. 2013;44:558–563. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.112.671347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jouanjus E, Raymond V, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Wolff V. What is the current knowledge about the cardiovascular risk for users of cannabis-based products? A systematic review. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 2017;19:26. doi: 10.1007/s11883-017-0663-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jouanjus E, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Micallef J, French Association of the Regional Abuse and Dependence Monitoring Centres (CEIP-A) Working Group on Cannabis Complications Cannabis use: Signal of increasing risk of serious cardiovascular disorders. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2014;3:e000638. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reis JP, et al. Cumulative lifetime marijuana use and incident cardiovascular disease in middle age: The coronary artery risk development in young adults (CARDIA) study. Am. J. Public Health. 2017;107:601–606. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2017.303654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Waterreus A, Di Prinzio P, Martin-Iverson MT, Morgan VA. Sex differences in the cardiometabolic health of cannabis users with a psychotic illness. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;194:447–452. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wetherington CL. Sex-gender differences in drug abuse: A shift in the burden of proof? Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2007;15:411–417. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.5.411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Park J-Y, Wu L-T. Prevalence, reasons, perceived effects, and correlates of medical marijuana use: A review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2017;177:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whiting PF, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313:2456–2473. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kjeldsen SE. Hypertension and cardiovascular risk: General aspects. Pharmacol. Res. 2018;129:95–99. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alshaarawy O, Elbaz HA. Cannabis use and blood pressure levels: United States National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005–2012. J. Hypertens. 2016;34:1507–1512. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bryson EO, Frost EAM. The perioperative implications of tobacco, marijuana, and other inhaled toxins. Int. Anesthesiol. Clin. 2011;49:103–118. doi: 10.1097/AIA.0b013e3181dd4f53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jadoon KA, Tan GD, O’Sullivan SE. A single dose of cannabidiol reduces blood pressure in healthy volunteers in a randomized crossover study. JCI Insight. 2017;2:93760. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.93760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenkrantz H, Braude M. Acute, subacute and 23-day chronic marihuana inhalation toxicities in the rat. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1974;28:428–441. doi: 10.1016/0041-008x(74)90228-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Benowitz NL, Jones RT. Cardiovascular effects of prolonged delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol ingestion. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1975;18:287–297. doi: 10.1002/cpt1975183287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pacher P, Bátkai S, Kunos G. The endocannabinoid system as an emerging target of pharmacotherapy. Pharmacol. Rev. 2006;58:389–462. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bátkai S, et al. Endocannabinoids acting at cannabinoid-1 receptors regulate cardiovascular function in hypertension. Circulation. 2004;110:1996–2002. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000143230.23252.D2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meier MH, et al. Associations between cannabis use and physical health problems in early midlife: A Longitudinal comparison of persistent cannabis vs tobacco users. JAMA Psychiat. 2016;73:731–740. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sudlow C, et al. UK biobank: an open access resource for identifying the causes of a wide range of complex diseases of middle and old age. PLoS Med. 2015;12:e1001779. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bycroft C, et al. The UK Biobank resource with deep phenotyping and genomic data. Nature. 2018;562:203–209. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0579-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Goyal H, Awad HH, Ghali JK. Role of cannabis in cardiovascular disorders. J. Thorac. Dis. 2017;9:2079–2092. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.06.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lev-Ran S, et al. The association between cannabis use and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol. Med. 2014;44:797–810. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davis KAS, et al. Indicators of mental disorders in UK Biobank: A comparison of approaches. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2019;28:e1796. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.UK Biobank. Arterial Pulse-Wave Velocity. https://biobank.ndph.ox.ac.uk/ukb/ukb/docs/Pulsewave.pdf.

- 29.UK Biobank. UK Biobank Blood Pressure. https://biobank.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/crystal/docs/Bloodpressure.pdf.

- 30.Coleman A, Freeman P, Steel S, Shennan A. Validation of the Omron 705IT (HEM-759-E) oscillometric blood pressure monitoring device according to the British Hypertension Society protocol. Blood Press. Monit. 2006;11:27–32. doi: 10.1097/01.mbp.0000189788.05736.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stang A, et al. Algorithms for converting random-zero to automated oscillometric blood pressure values, and vice versa. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2006;164:85–94. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Said MA, Eppinga RN, Lipsic E, Verweij N, van der Harst P. Relationship of arterial stiffness index and pulse pressure with cardiovascular disease and mortality. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 2018;7:e007621. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.117.007621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Badji A, Cohen-Adad J, Girouard H. Relationship between arterial stiffness index, pulse pressure, and magnetic resonance imaging markers of white matter integrity: A UK Biobank study. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2022;14:856782. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.856782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vallée A. Association between serum uric acid and arterial stiffness in a large-aged 40–70 years old population. J. Clin. Hypertens. 2022;24:885–897. doi: 10.1111/jch.14527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vallée A. Arterial stiffness nomogram identification by cluster analysis: A new approach of vascular phenotype modeling. J. Clin. Hypertens. Greenwich Conn. 2022 doi: 10.1111/jch.14571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Williams B, et al. 2018 practice guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension of the European society of hypertension and the European society of cardiology: ESH/ESC task force for the management of arterial hypertension. J. Hypertens. 2018;36:2284–2309. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000001961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.UK Biobank. Biomarker assay quality procedures: Approaches used to minimise systematic and random errors (and the wider epidemiological implications). https://biobank.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/crystal/crystal/docs/biomarker_issues.pdf. (2019).

- 38.Chadeau-Hyam M, et al. Education, biological ageing, all-cause and cause-specific mortality and morbidity: UK biobank cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 2020;29–30:100658. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tyrrell J, et al. Height, body mass index, and socioeconomic status: Mendelian randomisation study in UK Biobank. BMJ. 2016;352:i582. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vallée A, et al. Patterns of hypertension management in France in 2015: The ESTEBAN survey. J. Clin. Hypertens. Greenwich Conn. 2020 doi: 10.1111/jch.13834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Matheson J, et al. Sex differences in the acute effects of smoked cannabis: Evidence from a human laboratory study of young adults. Psychopharmacology. 2020;237:305–316. doi: 10.1007/s00213-019-05369-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang M, et al. The paradox association between smoking and blood pressure among half million Chinese people. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health. 2020;17:E2824. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17082824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas DC. Invited commentary: Is it time to retire the ‘pack-years’ variable? Maybe not! Am. J. Epidemiol. 2014;179:299–302. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Penner EA, Buettner H, Mittleman MA. The impact of marijuana use on glucose, insulin, and insulin resistance among US adults. Am. J. Med. 2013;126:583–589. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strandberg TE, Pitkala K. What is the most important component of blood pressure: systolic, diastolic or pulse pressure? Curr. Opin. Nephrol. Hypertens. 2003;12:293–297. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200305000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams B, Lindholm LH, Sever P. Systolic pressure is all that matters. Lancet Lond. Engl. 2008;371:2219–2221. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60804-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rodondi N, et al. Marijuana use, diet, body mass index, and cardiovascular risk factors (from the CARDIA study) Am. J. Cardiol. 2006;98:478–484. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Niiranen TJ, Kalesan B, Mitchell GF, Vasan RS. Relative contributions of pulse pressure and arterial stiffness to cardiovascular disease. Hypertension. 2019;73:712–717. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.118.12289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Alshaarawy O, Anthony JC. Cannabis smoking and diabetes mellitus: Results from meta-analysis with eight independent replication samples. Epidemiol. Camb. Mass. 2015;26:597–600. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Le Strat Y, Le Foll B. Obesity and cannabis use: Results from 2 representative national surveys. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2011;174:929–933. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Costa B. On the pharmacological properties of Delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) Chem. Biodivers. 2007;4:1664–1677. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200790146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vallée A, Lecarpentier Y, Guillevin R, Vallée J-N. Effects of cannabidiol interactions with Wnt/β-catenin pathway and PPARγ on oxidative stress and neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 2017;49:853–866. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmx073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stanley CP, Hind WH, Tufarelli C, O’Sullivan SE. Cannabidiol causes endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation of human mesenteric arteries via CB1 activation. Cardiovasc. Res. 2015;107:568–578. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvv179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vandrey R, Umbricht A, Strain EC. Increased blood pressure after abrupt cessation of daily cannabis use. J. Addict. Med. 2011;5:16–20. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0b013e3181d2b309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hartman RL, et al. Controlled cannabis vaporizer administration: Blood and plasma cannabinoids with and without alcohol. Clin. Chem. 2015;61:850–869. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.238287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Legrand S-A, et al. Alcohol and drugs in seriously injured drivers in six European countries. Drug Test. Anal. 2013;5:156–165. doi: 10.1002/dta.1393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Toennes SW, et al. Influence of ethanol on cannabinoid pharmacokinetic parameters in chronic users. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2011;400:145–152. doi: 10.1007/s00216-010-4449-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cooper ZD, Craft RM. Sex-dependent effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: A translational perspective. Neuropsychopharmacol. Off. Publ. Am. Coll. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;43:34–51. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fogel JS, Kelly TH, Westgate PM, Lile JA. Sex differences in the subjective effects of oral Δ9-THC in cannabis users. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 2017;152:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Richiardi L, Pizzi C, Pearce N. Commentary: Representativeness is usually not necessary and often should be avoided. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013;42:1018–1022. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyt103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rothman KJ, Gallacher JEJ, Hatch EE. Why representativeness should be avoided. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2013;42:1012–1014. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Harrison L. The validity of self-reported drug use in survey research: An overview and critique of research methods. NIDA Res. Monogr. 1997;167:17–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.