Abstract

Background

The management of feline hindlimb full-thickness skin defects is challenging. On the other hand, the use of a semitendinosus (ST) myocutaneous flap for their coverage has not been reported.

Objectives

To describe the ST flap and compare it with second intention healing for managing hindlimb full-thickness skin defects.

Methods

In 12 purpose-bred laboratory domestic short-haired cats, two wounds were made on each tibia. The wounds in group A (n = 12) were covered with ST flaps, and those in group B (n = 12) were left to heal by second intention. In both groups, clinical assessment scoring and planimetry were performed between one–30 d postoperatively. Computed tomography-angiography (CTA) was performed on days zero, 10, and 30, and histological examinations were performed on days zero and 14 and at 6 and 12 mon postoperatively.

Results

Statistically significant differences in the clinical assessment scores were observed between groups A and B on days 14 (p = 0.046) and 21 (p = 0.016). On the other hand, the time for complete healing was similar in the two groups. CTA revealed significant differences in the muscle width (day 0 compared to days 10 and 30 [p = 0.001, p = 0.026, respectively], and days 10 to 30 [p = 0.022]), ST muscle density, and the caliber of the distal caudal femoral artery and vein (day 0 compared to day 10 [p < 0.001], and days 10 to 30 [p < 0.001]). Histologically significant differences in inflammation, degeneration, edema, neovascularization, and fibrosis were observed on day 14 compared to zero and 6 mon, but no differences were found between the time interval of 6 and 12 mon.

Conclusions

An ST flap can be used effectively to manage hindlimb full-thickness skin defects.

Keywords: Cats, myocutaneous flap, semitendinosus muscle

INTRODUCTION

Management of wounds on the distal limbs in small animals is often challenging because of the paucity of elastic skin, the absence of the panniculus muscle, and the greater distance from potential donor areas [1,2]. Traumas and shearing injuries, burns, ablative tumor management procedures and radiation therapy wounds, chronic ulcers, and congenital defects on the distal limbs may lead to massive soft tissue loss, blood supply disruption, wound contamination, exposed anatomical structures (vessels, peripheral nerves, tendons, and bones), fractures, and osteomyelitis [1,3]. The treatment options for such wounds include second intention healing, tension relieving and skin advancement techniques, axial pattern flaps, skin grafts, and muscle and myocutaneous flaps [4,5,6].

Myocutaneous flaps incorporate a specific muscle with its overlying skin based on a vascular pedicle, which can be transferred as a composite unit to an adjacent defect in a one-stage procedure [7,8]. Their use in small animal surgery is limited by skin looseness and the presence of direct cutaneous arteries [9]. On distal limb wounds, myocutaneous flaps provide bulky tissue to cover complex defects and denuded bones, regulate blood supply to the recipient area and deliver host defense mechanisms and angiogenic factors [7,9]. These flaps were reported to be more resistant to infections, improve healing times compared to other methods, and are considered more appropriate when osteomyelitis is present [10,11,12,13,14,15].

Semitendinosus (ST) muscle is classified as a type III muscle, depending on the vascular pattern, being fed by two dominant pedicles, both capable of supplying blood to the whole muscle and covering its requirements in the case of ligation of any of them [10,16]. The ST muscle, depending on the blood supply of the proximal gluteal artery and vein, has been transferred for the repair of perineal hernia and external anal sphincter augmentation in dogs and the repair of perineal herniation in a cat [17,18]. Transposition of the ST muscle, as a myocutaneous flap, based on the distal caudal femoral artery and vein in one dog, has been used to manage an open tibial fracture [10]. To the authors’ knowledge, the use of ST myocutaneous flap (ST flap) for managing hindlimb full-thickness skin defects with exposed bone in cats has not been reported in veterinary surgery. Moreover, although various techniques may be used to close distal limb wounds in cats, there are no reports describing the potential benefits of using ST flaps.

This paper describes the ST flap as a reconstructive technique and compares it to second intention healing managing hindlimb skin defects with exposed bone in cats. The study was designed to determine if there would be any superiority of ST flap over second intention healing or if the two techniques would be equivalent. The hypothesis evaluated during the study was that in cats, advancement of the ST flap could be used as an alternative treatment for distal limb defects of at least equivalent safety and efficacy to second intention healing.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The study included twelve purpose-bred laboratory domestic short-haired cats aged 1–4 yr (seven castrated males and five spayed females). Before the study, their health status was assessed by a physical examination and hematology, serum biochemical analysis, urinalysis, fecal parasitology and feline leukemia virus, feline immunodeficiency virus, and feline infectious peritonitis tests. No drugs had been administered in the 2 mon prior to the experiment. The animals included in the study had no pathological skin or musculoskeletal conditions. The study was approved by the National Animal Ethics Committee (license number: 2734/12-6-2015), in accordance with the European Union directive 2010/63/EU, and by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Veterinary Science, University of Thessaly (license number: 15/16-6-2015). All procedures were performed in accordance with the above regulations. Throughout the study, cats were housed in the Department of Surgery of the Faculty of Veterinary Science of the University of Thessaly (Greece). The license also determined the number of animals to the minimum possible based on welfare considerations. G-power analysis was performed for sample size calculations and showed an actual power of 94.5%. The cats were adopted after the completion of the study.

In each cat, two identical wounds were produced on the distal medial surface of both tibial areas. The wounds were allocated randomly into two groups (A and B) using a computer program (Random Number Generator). Six and six animals had ST flaps on the right and left hindlimbs, respectively. The wounds in group A (n = 12) were covered with ST flaps, and those in group B (n = 12) were left to heal by second intention. In both groups, clinical assessment scoring and planimetry were performed at zero, seven, 14, 21, and 30 d postoperatively. Computed tomography-angiography (CTA) was performed on days zero, 10, and 30, and a histological examination was performed on days zero and 14 and at 6 and 12 mon postoperatively.

Presurgical management

The cats were premedicated with dexmedetomidine (20 μg/kg, intramuscularly [IM], Dexdomitor 0.5 mg/mL; Elanco, Greece) and butorphanol (0.3 mg/kg, IM, Dolorex 10 mg/mL; MSD, Greece). Anesthesia was induced with propofol 1% (2–4 mg/kg, intravenously [IV], Propofol MCT/LCT 1%; Fresenius Kabi Hellas, Greece) and maintained with isoflurane (2%, Isoflo; Abbott Laboratories, UK) in oxygen (2 L/min). An NS 0.9% solution IV was administered at 4 mL/kg/h during anesthesia. Preoperatively, amoxicillin and clavulanic acid (20 mg/kg, subcutaneously [SC], Synulox RTU Inj. 100 mL; Zoetis, Greece) and carprofen (2 mg/kg, IV, Rimadyl; Zoetis) were administered.

Surgical procedure

A full-thickness rectangular skin defect was produced on the medial surface of the distal tibia of each hindlimb, 1 cm cranial to the tarsal joint, measuring 2 cm in length and 1 cm in width. The caudal tibial and medial digital flexor muscle tendons were retracted caudally to reveal the tibial bone. The tibial periosteum was incised, elevated, and removed. In group B, the skin edges were tacked to the underlying tissues using simple interrupted sutures to leave the bone denuded (Fig. 1). The sutures were removed on day seven after firm adhesions had formed between the skin and underlying tissues [19].

Fig. 1. Full-thickness skin defects with exposed bone formed on the medial surface of the distal tibia. In group B, skin edges were tacked to the underlying tissues by simple interrupted sutures.

For ST flap development, skin incisions were made along the caudal border of the ischial tuberosity and continued distally to the popliteal area. The ST origin was cut by electrocautery (Diatermo MB 122; Gima, Italy) from the ischial tuberosity. Care was taken when the undermining area approached the popliteal fat to preserve the distal caudal femoral artery, vein, and nerve branch of the muscle(Supplementary Fig. 1). A bridging skin incision was made between the base of the ST flap and the defect on the medial surface of the distal tibia, and the flap was rotated 150°–170° distally to cover the defect (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Semitendinosus myocutaneous flap sutured at the recipient area to cover the defect.

Postoperative management

Morphine hydrochloride (0.2 mg/kg, IM, Morfina cloridrato; Molteni, Italy) was administered for analgesia at the end of surgery and every 4–6 h for 2 d. Amoxycillin and clavulanic acid (20 mg/kg, sid, SC, Synulox RTU Inj. 100 mL; Zoetis) were administered until complete healing, and carprofen (2 mg/kg, sid, SC, Rimadyl; Zoetis) was administered for 5 d. Elizabethan collars were used in all cats. All wounds were covered with a three-layer padded bandage that was changed daily during the first week and then every other day until complete healing. During bandage changes and planimetry measurements, the cats were sedated with dexmedetomidine (20 μg/kg, IM, Dexdomitor 0.5 mg/mL; Elanco) and butorphanol (0.2 mg/kg, IM, Dolorex 10 mg/mL; MSD).

Clinical assessment scoring

In both groups, a clinical assessment was performed at zero, seven, 14, 21, and 30 d after surgery by the same person (ED). Flap and wound assessment scoring systems were used to quantify the clinical observations. The pain was evaluated using the Colorado State University Feline Acute Pain Scale [20,21] while cats were alert before and after bandage changing. Based on wound evaluation in both groups, on the previous days, a healing score was calculated based on the criteria described in recent reports on wound assessment [22,23,24], as shown in Table 1 for group A and Table 2 for group B.

Table 1. Scoring criteria for clinical assessment of flaps in group A.

| Criteria | Score | |

|---|---|---|

| A. Pain | ||

| Minimal | 0 | |

| Mild | 1 | |

| Mild to moderate | 2 | |

| Moderate | 3 | |

| Moderate to severe | 4 | |

| B. Extremity appearance | ||

| Normal | 0 | |

| Minimal edematous | 1 | |

| Mild edematous | 2 | |

| Moderate edematous | 3 | |

| Severe edematous | 4 | |

| C. Surrounding skin appearance | ||

| Intact | 0 | |

| Erythematic | 1 | |

| Granulation tissue | 2 | |

| Hypergranulation tissue | 3 | |

| Indurated | 4 | |

| Macerated | 5 | |

| Excoriated | 6 | |

| Necrotic | 7 | |

| D. Skin flap appearance | ||

| Normal skin | 0 | |

| Erythematic | 1 | |

| Congested | 2 | |

| Slough | 3 | |

| Necrotic | 4 | |

| Eschar | 5 | |

| No skin | 6 | |

| E. Skin tissue involvement | ||

| Normal skin | 0 | |

| Partial thickness | 1 | |

| Full thickness | 2 | |

| F. Part of the flap affected | ||

| None | 0 | |

| Distal | 1 | |

| Central | 2 | |

| Whole flap | 3 | |

| G. Skin adherence to deep tissues (to the transported muscle) | ||

| Firmly adherent | 0 | |

| Loosely adherent | 1 | |

| Non adherent | 2 | |

| No skin | 3 | |

| H. Flap edges attachment | ||

| Attached to adjacent skin | 0 | |

| Nonattached to adjacent skin | 1 | |

| No skin | 2 | |

| I. Exudate amount | ||

| None | 0 | |

| Slight | 1 | |

| Moderate | 2 | |

| Heavy | 3 | |

| J. Exudate appearance | ||

| None | 0 | |

| Serous | 1 | |

| Serosanguineous | 2 | |

| Sanguineous | 3 | |

| Purulent | 4 | |

| K. Odor present after cleansing | ||

| No | 0 | |

| Yes | 1 | |

| Total score | 0–39 | |

Table 2. Scoring criteria for the clinical assessment of second intention healing in group B.

| Criteria | Score | |

|---|---|---|

| A. Pain | ||

| Minimal | 0 | |

| Mild | 1 | |

| Mild to moderate | 2 | |

| Moderate | 3 | |

| Moderate to severe | 4 | |

| B. Extremity appearance | ||

| Normal | 0 | |

| Minimal edematous | 1 | |

| Mild edematous | 2 | |

| Moderate edematous | 3 | |

| Severe edematous | 4 | |

| C. Surrounding skin appearance | ||

| Intact | 0 | |

| Erythematic | 1 | |

| Granulation tissue | 2 | |

| Hypergranulation tissue | 3 | |

| Indurated | 4 | |

| Macerated | 5 | |

| Excoriated | 6 | |

| Necrotic | 7 | |

| D. Tissue type appearance | ||

| Closed/Resurfaced | 0 | |

| Epithelial | 1 | |

| Granulation | 2 | |

| Hypergranulation tissue | 3 | |

| Slough | 4 | |

| Necrotic | 5 | |

| Eschar | 6 | |

| E. Skin adherence to deep tissues | ||

| Firmly adherent | 0 | |

| Loosely adherent | 1 | |

| Non adherent | 2 | |

| No skin | 3 | |

| F. Exudate amount | ||

| None | 0 | |

| Slight | 1 | |

| Moderate | 2 | |

| Heavy | 3 | |

| G. Exudate appearance | ||

| Normal | 0 | |

| Serous | 1 | |

| Serosanguineous | 2 | |

| Sanguineous | 3 | |

| Purulent | 4 | |

| H. Odor present after cleansing | ||

| No | 0 | |

| Yes | 1 | |

| Total score | 0–32 | |

Planimetry

Digital images of the wounds and computer software (AutoCAD, version 2018; Autodesk, USA) were used for the planimetry evaluation. Images were taken on days zero, seven, 14, 21, and 30 after surgery (Supplementary Fig. 2).

In group A, planimetry of the myocutaneous flaps was used to measure the flap dimensions (width and length [cm]) and total skin flap surface on day 0 (initial total flap area [cm2]). The percentage of skin flap area viable on day 30 was considered the final total flap area (cm2) and was calculated using the previously reported formula [25,26,27] as follows:

| % Final Total Flap Area on Day (30) = (Viable Skin Surface on Day (30)/Initial Total Flap Area) × 100 |

The percentage of flap necrosis was calculated according to the previously reported formula as follows [25,26,27]:

| % Flap Necrosis on Day (n) = (Total Area of Skin Necrosis on Day (n)/Initial Total Flap Area) × 100 |

In group B, planimetry was used to estimate the initial wound area, the area covered by epithelium, and the unhealed area. The percentage of epithelialization, wound contraction, and total wound healing was calculated for each wound according to the previously reported formula [25,26,27].

CTA

CT of the pelvis and hindlimbs, pre and post-intravenous contrast medium administration, iobitridol (2 mL/kg, IV, Xenetix inj. sol. 300 mg/mL; Guerbet, France), was performed to evaluate the arterial and venous phase. The following parameters were evaluated on a dedicated workstation on a soft tissue window: ST muscle length (cm) and width (cm), the caliber of the proximal gluteal and distal caudal femoral artery and vein (mm), and the density of ST muscle (10 mm2) at three different points (dP: proximal, dM: medial, and dD: distal) in three different phases (pre-contrast agent, arterial and venous phase) (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Excess neovascularization of the semitendinosus myocutaneous flap and vascular anastomoses at the donor site (white arrows) on a 3-dimensional computed tomography-angiography, 10 d postoperatively.

Histological evaluation of the ST flap

Tissue samples were collected using a 6 mm biopsy punch (Biopsy punch; Kruuse, Denmark). The specimens were obtained from the distal tip of the flap on day zero. In contrast, on day 14, specimens were obtained from the most medial part of the distal edge of each flap to prevent disturbing the flap microcirculation.

At 6 and 12 mon, specimens measuring 1 cm in width × 2 cm in length were obtained from each flap. All samples were processed using standard techniques and stained with haematoxylin and eosin. The stained sections were evaluated to assess inflammation, muscle cell degeneration, muscle cell necrosis, neovascularization, fibrosis, and edema quantitatively classified as follows: 0 (normal), no alterations present; 1 (+), alterations up to 33%; 2 (++), alterations between 34% and 66%; 3 (+++), alterations between 67% and 100% [28,29,30,31].

Statistical analysis

The normality of the data distribution was assessed using a Shapiro-Wilk test. Continuous data following a normal distribution are presented as the mean ± SD. The qualitative data are presented as frequency and percentages.

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to conduct paired differences of the repeated measurements of each group in the clinical assessment scores, planimetry, CTA, and histological evaluation. The comparison of the differences between the independent variables of the two groups in subjective evaluation clinical assessment scores and planimetry was performed using a Mann-Whitney U test. The Pearson correlation coefficient was used to evaluate the linear relationship between two continuous variables. A Spearman’s Rank-Order correlation test was used to reveal associations between the different evaluation methods.

The level of statistical significance for all comparisons was set to 5%. All tests in this analysis were performed using SPSS Statistical software (SPSS, version 28.0; IBM-SPSS Science, USA).

RESULTS

Clinical assessment scoring

The median time to complete flap healing in group A (30.33 d, range: 20–52) was similar to complete epithelial coverage in group B (27.50 d, range: 19–45).

Table 3 lists the clinical assessment scores in groups A and B. Statistically significant differences were observed in group A between days seven and 30 (p = 0.027), 14 and 30 (p = 0.002), and 21 and 30 (p = 0.016). In group B, statistically significant differences were observed between days seven and 14 (p < 0.001), 14 and 21 (p < 0.001), 21 and 30 (p < 0.001), 7 and 30 (p < 0.001) and, 14 and 30 (p < 0.001).

Table 3. Clinical assessment scores.

| Clinical assessment score | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 21 | Day 30 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | 8.00 ± 2.13a | 8.92 ± 6.79b,f | 7.42 ± 6.36c,g | 3.67 ± 6.10a,b,c |

| Group B | 7.25 ± 1.14a,d | 4.83 ± 1.52a,b,e,f | 2.41 ± 1.44b,c,g | 1.41 ± 1.00c,d,e |

The values are presented as the mean ± SD.

a-eSame superscripts within the same row indicate significant differences between respectively marked groups.

f-gSame superscripts within the same column indicate significant differences between respectively marked groups.

Group A showed statistically significant higher assessment scores on days 14 (p = 0.046) and 21 (p = 0.016) than group B.

Planimetry

Table 4 lists the planimetric measurements in groups A and B. In group A, a significant difference in % flap necrosis was observed between days seven and 14 (p = 0.011). In group B, significant differences were found between days seven to 14, 14 to 21, and 21 to 30 in % epithelialization (p < 0.001, p < 0.001 and p = 0.002), % wound contraction (p = 0.002, p < 0.001 and p < 0.001), and % total wound healing (p < 0.001, p < 0.001 and p = 0.004), respectively.

Table 4. Planimetric measurements in groups A and B.

| Group | Day 0 | Day 7 | Day 14 | Day 21 | Day 30 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A | ||||||

| Flap width (cm) | 1.6 ± 0.3 | |||||

| Flap length (cm) | 7.3 ± 0.5 | |||||

| Initial total flap area (cm2) | 11.7 ± 1.5 | |||||

| % final total flap area | 66.9 ± 29.2 | |||||

| % flap necrosis | 12.1 ± 28.8a | 28.2 ± 28.1a | 21.9 ± 29.8 | 8.9 ± 17.5 | ||

| Group B | ||||||

| % epithelialisation | 0a,* | 41.6 ± 13.2a,b | 68.2 ± 23.1b,c | 91.7 ± 19.7c | ||

| % wound contraction | −8 ± 16.8a,† | 20.2 ± 36.1a,b | 60.7 ± 21.1b,c | 78.8 ± 14.6c | ||

| % total wound healing | −7.8 ± 17a,† | 51.7 ± 28.2a,b | 86 ± 16.3b,c | 95.9 ± 9.7c | ||

The values are presented as the mean ± SD.

a-cSame superscripts within the same row indicate significant differences between respectively marked groups.

*There is no detectable epithelialization on day 7.

†Negative numbers indicate enlargement of wound size due to retraction of the wound edges from sutures placement.

A significant positive correlation was observed in group A between flap assessment score and % flap necrosis on day 14 (p < 0.001) and day 21 (p = 0.002). A significant positive correlation was found in group B between the wound assessment score and % total wound healing on day 21 (p = 0.016) and day 30 (p < 0.001).

CTA

Table 5 lists the parameters CTA studied in group A. Significant differences in muscle width were observed, which was higher on day 10 compared to day 0 (p = 0.001), on day 30 compared to day zero (p = 0.026), and on day 10 compared to day 30 (p = 0.022). Significant differences in ST muscle density were observed, which was higher on day 10 compared to day zero, and on day 10 compared to day 30 (p < 0.001) on all points in all three different phases, except for dD point at the arterial phase between days zero and 10. Significant differences in the caliber of the distal caudal femoral artery and vein were observed, which was higher on day 10 than on day zero and on day 10 compared to day 30 (p < 0.001).

Table 5. Parameters studied on computed tomography-angiographies in group A.

| Parameters | Day 0 | Day 10 | Day 30 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Muscle length (cm) | 10.73 ± 1.05 | NA† | NA† |

| Muscle width day (cm) | 2.12 ± 0.21a,c | 2.25 ± 0.28a,b | 2.15 ± 0.22b,c |

| Proximal gluteal artery caliber (mm) | 0.86 ± 0.03 | NA* | NA* |

| Proximal gluteal vein caliber (mm) | 1.25 ± 0.05 | NA* | NA* |

| Distal caudal femoral artery caliber (mm) | 0.87 ± 0.05a | 1.03 ± 0.05a,b | 0.87 ± 0.04b |

| Distal caudal femoral vein caliber (mm) | 1.27 ± 0.04a | 1.50 ± 0.05a,b | 1.26 ± 0.02b |

| Muscle density on the proximal point when no contrast agent is given (dP) | 52.22 ± 3.98a | 57.9 ± 3.59a,b | 55.9 ± 3.51b |

| Muscle density on the medial point when no contrast agent is given (dM) | 53.77 ± 3.97a | 55.03 ± 3.59a,b | 54.30 ± 3.51b |

| Muscle density on the distal point when no contrast agent is given (dD) | 52.66 ± 3.96a | 54.27 ± 3.42a,b | 51.77 ± 4.09b |

| Muscle density on the proximal point - arterial phase (dPa) | 67.65 ± 5.97a | 87.60 ± 5.36a,b | 81.79 ± 3.55b |

| Muscle density on the medial point - arterial phase (dMa) | 72.04 ± 5.43a | 79.48 ± 2.93a,b | 74.26 ± 2.80b |

| Muscle density on the distal point - arterial phase (dDa) | 69.58 ± 5.77 | 71.88 ± 1.91b | 67.83 ± 2.31b |

| Muscle density on the proximal point - venous phase (dPv) | 74.26 ± 5.56a | 93.75 ± 6.17a,b | 87.34 ± 3.89b |

| Muscle density on the medial point - venous phase (dMv) | 78.51 ± 6.12a | 84.06 ± 3.08a,b | 77.90 ± 2.67b |

| Muscle density on the distal point - venous phase (dDv) | 75.74 ± 5.40b | 78.87 ± 2.63a,b | 73.23 ± 1.59b |

The values are presented as the mean ± SD.

NA, not applicable.

a-cSame superscripts within the same row indicate significant differences between respectively marked groups.

*Parameters could not be measured as the proximal gluteal artery and vein were dissected during the surgery.

†Parameters could not be measured as the semitendinosus muscles were transferred to the new area in order to cover the defect.

A significant positive correlation was observed in the following: between a) dP and dM point and between dM and dD point on day 30 when no contrast agent was given (p < 0.001, p = 0.045 respectively); b) between dP and dM point at the arterial phase on day 30 (p < 0.001); c) between dP and dM point at the arterial phase with dP point at the venous phase on day 30 (p < 0.001, p = 0.001 respectively); d) between dM point at the arterial phase with dD point at the venous phase on day 30 (p = 0.03).

No significant correlation was observed on all days between % flap necrosis and muscle density, between % flap necrosis and caliber of the distal caudal femoral artery and vein, between the histological parameters and muscle density, and between the histological parameters and the caliber of the distal caudal femoral artery and vein.

Histological evaluation of the ST flap

Table 6 lists the results of the histological evaluation of the various parameters examined in the tissue samples.

Table 6. Results of the various parameters studied during the histological evaluation of tissue samples in group A.

| Histological score | Day 0 (n = 12) | Day 14 (n = 12) | 6 mon (n = 6) | 12 mon (n = 6) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inflammation | 0a | 2.00 ± 0.95a,b | 0.08 ± 0.29b | 0.33 ± 0.65 |

| Degeneration/Necrosis | 1.67 ± 0.49a | 2.33 ± 0.98a,b | 1.67 ± 0.52b | 1.50 ± 1.38 |

| Neovascularization | 0a | 0.83 ± 0.94a | 0 | 0.17 ± 0.41 |

| Fibrosis | 0a | 0.92 ± 1.08a | 0.17 ± 0.41 | 0.17 ± 0.41 |

| Edema | 0.58 ± 0.51a | 1.42 ± 0.51a,b | 0.50 ± 0.55b | 0.67 ± 0.82 |

| Total score | 0.45 ± 0.73 | 1.50 ± 0.66 | 0.48 ± 0.69 | 0.57 ± 0.56 |

The values are presented as the mean ± SD.

a,bSame superscripts within the same row indicate significant differences between respectively marked groups.

On day zero, ischemic lesions and edema were mostly observed in the samples. Significant differences were observed in inflammation, muscle cell degeneration, and edema, which were higher on day 14 than on day zero and 6 mon (p < 0.001, p = 0.039, p = 0.012, p = 0.002, p = 0.012, respectively). Neovascularization and fibrosis were scored significantly higher on day 14 than on day zero (p = 0.010 and p = 0.014, respectively). No statistically significant differences in any of the parameters were observed between 6 and 12 mon.

No significant correlation was observed between the flap assessment scores and histological parameters on day 14.

DISCUSSION

The effectiveness of ST muscle flap as a distal limb reconstructive technique in cats has not been studied. Moreover, there are no reports on whether the entire muscle can survive on the distal vascular pedicle alone. These findings suggest that the ST flap is an effective reconstructive technique for distal limb defects in cats with favorable outcomes and without affecting motor function. Based on these results, the ST flap is of equivalent safety and efficacy to second intention healing because the healing times were similar in the two groups. The blood supply of the distal vascular pedicle alone was sufficient for the survival of the ST flap.

ST flap development was easy to perform but more technically demanding than a non-sutured wound and offered adequate coverage of tibial wounds with a stable blood supply. When left to heal by second intention, such open wounds with exposed bone in cats usually require at least daily patient sedation for lavage and bandage changes. This is time-consuming, expensive, and has higher infection risk and bandage-changing problems than other surgical methods [4,27,32].

The length of the flaps allowed adequate coverage of the defects without stressing the vascular pedicle [18]. Despite gentle tissue handling during the procedures, shearing forces at the most distal part of the flaps could not be avoided. As a result, the skin and subcutaneous tissue at this point were partially detached from the underlying fascia. This is possible when handling narrow myocutaneous flaps, such as ST, and can lead to focal vascular disruption [33]. This might explain the higher clinical assessment scores in group A than in group B on days 14 and 21 because necrotic areas at the most distal part of the flap were recorded in group A. Furthermore, clinical scoring could not be done using the same parameters on control wounds and flaps (second intention healing versus primary suturing) and scoring of the flaps concerned their entire surface which was significantly larger than that of controls. The clinical appearance of the skin flap evolved from erythematic to congested the first 2 d, possibly due to unstable blood flow and compromised venous drainage that can occur after the flap is raised [34,35]. Gradually, the skin regained its normal color or became necrotic after day 6. The necrotic lesions of the skin appeared to be stable by day 14 because the % flap necrosis was statistically different only between days seven and 14. On day 30, the mean viable final total skin area of the flap was 67%. The full-thickness skin necrosis observed at the distal tip of the myocutaneous flaps was attributed to hemodynamic changes leading to insufficient perfusion of the skin or due to a disruption in the microcirculation, such as thrombosis of arterioles or venules, reperfusion injury, and local injury of the plexus by shearing forces [34,35,36,37]. Minor surgical complications, such as skin necrosis, were observed in 10 animals (83.3%), which finally healed by the second intention. On the other hand, the ST muscle underneath the skin surface remained viable in all cases (100%). Major surgical complications, such as partial or complete flap loss, were not observed.

Although the time to complete healing was similar in the two groups, the wound contraction rate in group B was slower from day 21 to 30 as wounds were gradually epithelialized, whereas the wounds healed faster in group A (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5). This was attributed to the capability of the main vessels, to provide stable blood supply to the flap and deliver healing factors at the wound area. Furthermore, the apposition of a myocutaneous flap on a specific defect prevents the early-stage excessive wound contraction at the wound site, which occurs during second intention healing [25].

CTA on day 10 showed that flap technique errors, such as injury, kinking, twisting, or thrombosis of the distal caudal femoral artery and vein, were not present in any cat. A significant increase in muscle density observed on day 10 compared to day 0 indicates that gradual vasodilatation, neovascularization, and new vascular anastomoses established reliable blood flow in the whole muscle [9]. This finding is further supported by the larger caliber measurements of the distal vascular pedicle on day 10. The significantly larger caliber on day 10 than on day 30 and the absence of differences between day zero and day 30 indicates a return to their initial size on day 30. The changes in muscle density were similar. These findings indicate recovery in the flap blood flow after transfer and ligation of the proximal gluteal artery and vein and maintenance of adequate perfusion by day 30 [16]. This is consistent with the clinical assessment scores in group A where the % flap necrosis seemed to be stable by day 14, and necrotic lesions were confined only to the overlying skin.

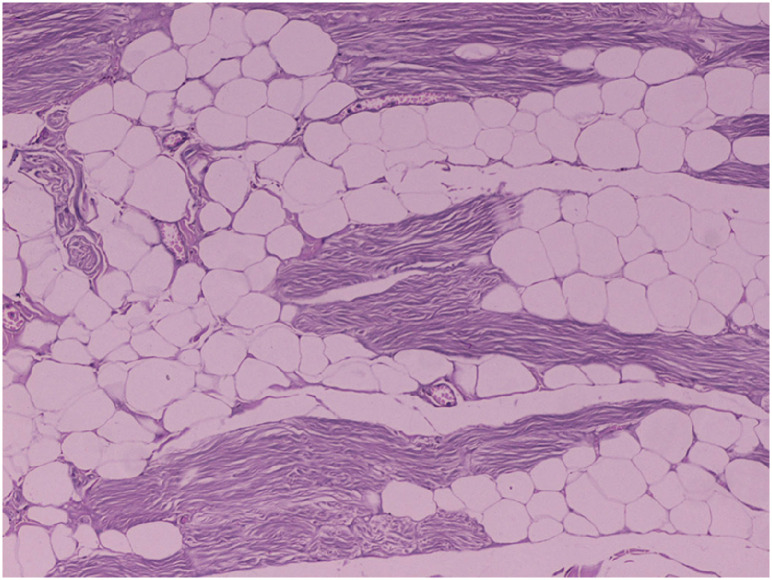

The histology evaluation showed that ST flaps were well nourished depending on their distal caudal femoral pedicle because no major muscle necrosis was observed during the entire experimental procedure [9,16,30]. On day zero, necrosis and edema were observed in some specimens and attributed to tissue handling at the sampling points and electrocautery to control bleeding at the muscle origin when detached from the ischial tuberosity. By day 14, significantly higher scores were recorded in all parameters than on day zero. These scores probably represent the effects of the inflammatory response during wound healing, compromised blood flow, and the reperfusion injury that the ST flap normally developed 2 wk postoperatively at its distal part, where the sample points were harvested [28,29,30,31]. The 6- and 12-mon examination samples were characterized mostly by muscle cell degeneration (Fig. 4), probably due to the gradual loss of the normal muscle fibers and their replacement by fatty and fibrous tissue after the neurovascular division of the upper third of the ST muscle [29].

Fig. 4. Histology in group A, 6 mon postoperatively. Multifocal fatty degeneration and atrophy of myofibers (haematoxylin and eosin stain, ×100 magnification).

The study limitations include the small number of animals because welfare concerns precluded using a larger number. Clean surgical wounds supported a favorable outcome even in wounds left to heal by the second intention. In contrast, managing such wounds in clinical cases may influence the outcome of the healing process. The techniques for myocutaneous flap development follow specific anatomic guidelines. Therefore, these flaps might be precluded in some clinical cases. Evaluation of healing scores could not be performed with a blind evaluation. Imaging methods to assess flap skin perfusions, such as laser Doppler flowmetry or fluorescein dye, were not performed [38,39,40]. Further studies will be needed to establish the potential influence of blood flow based only on the distal vascular pedicle at the skin. The extent of the arc of rotation of the ST flap, based on its distal vascular pedicle, was not defined. Therefore, further research is indicated. In future studies, it would be interesting to compare the ST flap with second intention healing using various dressing materials.

In conclusion, the ST flap based on the distal vascular pedicle is a reliable method for the one-stage management of hindlimb full-thickness skin defects with exposed bone in cats.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank Mr. Konstantinos Krikonis, Head of Data Analysis, for his significant support in statistical data analysis and Associate professor P.G. Gouletsou for her assistance in editing some of the figures. In addition, the authors are grateful to Pharmacell Greece for providing some of the products used in the study.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

- Conceptualization: Tsioli V.

- Data curation: Dermisiadou E, Tsioli V.

- Formal analysis: Dermisiadou E, Sideri , Galatos , Tsioli V.

- Investigation: Dermisiadou E, Panopoulos I, Psalla D, Georgiou S, Tsioli V.

- Methodology: Dermisiadou E, Tsioli V.

- Project administration: Tsioli V.

- Supervision: Tsioli V.

- Visualization: Dermisiadou E.

- Writing - original draft: Dermisiadou E.

- Writing - review & editing: Psalla D, Sideri A, Galatos A, Tsioli V.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Semitendinosus myocutaneous flap development. The tip of the forceps points at the distal caudal femoral artery and vein and the distal nerve branch of the muscle through the abundant popliteal fat.

Planimetry evaluation with a computer software. (A) Measurement of skin flap necrosis area in group A, on day 14. (B) Measurements of the total wound area (represented by the whole area within the outer line), the area covered by new epithelium (area that is depicted between the outer and the inner line) and the unhealed area (area within the inner line) in group B, on day 14.

Computed tomography. Evaluation of the density of semitendinosus muscle (10 mm2) at three different points [proximal (A), medial (B) and distal (C)] in three different phases [pre-contrast agent (1), arterial phase (2) and venous phase (3)].

The healing process of a semitendinosus myocutaneous flap in group A depicted on day 7 (A), day 21 (B), day 30 (C) and 6 mon (D) postoperatively.

The healing process of a wound in group B depicted on day 7 (A), day 14 (B), day 21 (C) and 6 mon (D) postoperatively.

References

- 1.Beardsley SL, Schrader SC. Treatment of dogs with wounds of the limbs caused by shearing forces: 98 cases (1975-1993) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1995;207(8):1071–1075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hosgood G. Stages of wound healing and their clinical relevance. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2006;36(4):667–685. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fowler D. Distal limb and paw injuries. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2006;36(4):819–845. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Corr S. Intensive, extensive, expensive. Management of distal limb shearing injuries in cats. J Feline Med Surg. 2009;11(9):747–757. doi: 10.1016/j.jfms.2009.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aper RL, Smeak DD. Clinical evaluation of caudal superficial epigastric axial pattern flap reconstruction of skin defects in 10 dogs (1989-2001) J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 2005;41(3):185–192. doi: 10.5326/0410185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aper R, Smeak D. Complications and outcome after thoracodorsal axial pattern flap reconstruction of forelimb skin defects in 10 dogs, 1989-2001. Vet Surg. 2003;32(4):378–384. doi: 10.1053/jvet.2003.50043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCraw JB, Dibbell DG, Carraway JH. Clinical definition of independent myocutaneous vascular territories. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977;60(3):341–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mathes SJ, Nahai F. Classification of the vascular anatomy of muscles: experimental and clinical correlation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1981;67(2):177–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pavletic MM. Introduction to myocutaneous and muscle flaps. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1990;20(1):127–146. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(90)50007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Puerto DA, Aronson LR. Use of a semitendinosus myocutaneous flap for soft-tissue reconstruction of a grade IIIB open tibial fracture in a dog. Vet Surg. 2004;33(6):629–635. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.2004.04092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chambers JN, Purinton PT, Moore JL, Allen SW. Treatment of trochanteric ulcers with cranial sartorius and rectus femoris muscle flaps. Vet Surg. 1990;19(6):424–428. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950x.1990.tb01226.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chambers JN, Purinton PT, Allen SW, Schneider TA, Smith JD. Flexor carpi ulnaris (humeral head) muscle flap for reconstruction of distal forelimb injuries in two dogs. Vet Surg. 1998;27(4):342–347. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950x.1998.tb00137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pavletic MM, Kostolich M, Koblik P, Engler S. A comparison of the cutaneous trunci myocutaneous flap and latissimus dorsi myocutaneous flap in the dog. Vet Surg. 1987;16(4):283–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950x.1987.tb00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Weinstein MJ, Pavletic MM, Boudrieau RJ. Caudal sartorius muscle flap in the dog. Vet Surg. 1988;17(4):203–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950x.1988.tb00999.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weinstein MJ, Pavletic MM, Boudrieau RJ, Engler SJ. Cranial sartorius muscle flap in the dog. Vet Surg. 1989;18(4):286–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950x.1989.tb01087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Solano M, Purinton PT, Chambers JN, Munnell JF. Effects of vascular pedicle ligation on blood flow in canine semitendinosus muscle. Am J Vet Res. 1995;56(6):731–735. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chambers JN, Rawlings CA. Applications of a semitendinosus muscle flap in two dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1991;199(1):84–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vnuk D, Babić T, Stejskal M, Capak D, Harapin I, Pirkić B. Application of a semitendinosus muscle flap in the treatment of perineal hernia in a cat. Vet Rec. 2005;156(6):182–184. doi: 10.1136/vr.156.6.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Winkler JT, Swaim SF, Sartin EA, Henderson RA, Welch JA. The effect of a porcine-derived small intestinal submucosa product on wounds with exposed bone in dogs. Vet Surg. 2002;31(6):541–551. doi: 10.1053/jvet.2002.34669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Epstein ME, Rodanm I, Griffenhagen G, Kadrlik J, Petty MC, Robertson SA, et al. 2015 AAHA/AAFP pain management guidelines for dogs and cats. J Feline Med Surg. 2015;17(3):251–272. doi: 10.1177/1098612X15572062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathews K, Kronen PW, Lascelles D, Nolan A, Robertson S, Steagall PV, et al. Guidelines for recognition, assessment and treatment of pain: WSAVA Global Pain Council members and co-authors of this document. J Small Anim Pract. 2014;55(6):E10–E68. doi: 10.1111/jsap.12200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lazarus GS, Cooper DM, Knighton DR, Margolis DJ, Pecoraro RE, Rodeheaver G, et al. Definitions and guidelines for assessment of wounds and evaluation of healing. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130(4):489–493. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grey JE, Enoch S, Harding KG. Wound assessment. BMJ. 2006;332(7536):285–288. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7536.285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ousey K, Cook L. Wound assessment: made easy. Wounds UK. 2012;8(2):1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bohling MW, Henderson RA, Swaim SF, Kincaid SA, Wright JC. Cutaneous wound healing in the cat: a macroscopic description and comparison with cutaneous wound healing in the dog. Vet Surg. 2004;33(6):579–587. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.2004.04081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bohling MW, Henderson RA. Differences in cutaneous wound healing between dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2006;36(4):687–692. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bohling MW, Henderson RA, Swaim SF, Kincaid SA, Wright JC. Comparison of the role of the subcutaneous tissues in cutaneous wound healing in the dog and cat. Vet Surg. 2006;35(1):3–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950X.2005.00105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Costa W, Silva AL, Costa GR, Nunes TA. Histology of the rectus abdominis muscle in rats subjected to cranial and caudal devascularization. Acta Cir Bras. 2012;27(2):162–167. doi: 10.1590/s0102-86502012000200011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Degner DA, Walshaw R, Arnoczky SP, Smith RJ, Patterson JS, Degner LA, et al. Evaluation of the cranial rectus abdominus muscle pedicle flap as a blood supply for the caudal superficial epigastric skin flap in dogs. Vet Surg. 1996;25(4):292–299. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-950x.1996.tb01416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greaves P, Chouinard L, Ernst H, Mecklenburg L, Pruimboom-Brees IM, Rinke M, et al. Proliferative and non-proliferative lesions of the rat and mouse soft tissue, skeletal muscle and mesothelium. J Toxicol Pathol. 2013;26(3) Suppl:1S–26S. doi: 10.1293/tox.26.1S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Siemionow M, Manikowski W, Gawronski M. Histopathology of muscle flap microcirculation following prolonged ischemia. Microsurgery. 1995;16(8):515–521. doi: 10.1002/micr.1920160802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campbell BG. Dressings, bandages, and splints for wound management in dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 2006;36(4):759–791. doi: 10.1016/j.cvsm.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pavletic MM. Vascular supply to the skin of the dog: a review. Vet Surg. 1980;9(2):77–80. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pavletic MM. Axial pattern flaps in small animal practice. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1990;20(1):105–125. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(90)50006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pavletic MM. Canine axial pattern flaps, using the omocervical, thoracodorsal, and deep circumflex iliac direct cutaneous arteries. Am J Vet Res. 1981;42(3):391–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pang CY. Ischemia-induced reperfusion injury in muscle flaps: pathogenesis and major source of free radicals. J Reconstr Microsurg. 1990;6(1):77–83. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1006807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kerrigan CL, Stotland MA. Ischemia reperfusion injury: a review. Microsurgery. 1993;14(3):165–175. doi: 10.1002/micr.1920140307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lanthier T, Miller C, McDonell WN, Yager JA, Roth JH. Use of laser Doppler flowmetry to determine blood flow in and viability of island axial pattern skin flaps in rabbits. Am J Vet Res. 1990;51(12):1914–1921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pratt GF, Rozen WM, Chubb D, Whitaker IS, Grinsell D, Ashton MW, et al. Modern adjuncts and technologies in microsurgery: an historical and evidence-based review. Microsurgery. 2010;30(8):657–666. doi: 10.1002/micr.20809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Losken A, Styblo TM, Schaefer TG, Carlson GW. The use of fluorescein dye as a predictor of mastectomy skin flap viability following autologous tissue reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2008;61(1):24–29. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e318156621d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Semitendinosus myocutaneous flap development. The tip of the forceps points at the distal caudal femoral artery and vein and the distal nerve branch of the muscle through the abundant popliteal fat.

Planimetry evaluation with a computer software. (A) Measurement of skin flap necrosis area in group A, on day 14. (B) Measurements of the total wound area (represented by the whole area within the outer line), the area covered by new epithelium (area that is depicted between the outer and the inner line) and the unhealed area (area within the inner line) in group B, on day 14.

Computed tomography. Evaluation of the density of semitendinosus muscle (10 mm2) at three different points [proximal (A), medial (B) and distal (C)] in three different phases [pre-contrast agent (1), arterial phase (2) and venous phase (3)].

The healing process of a semitendinosus myocutaneous flap in group A depicted on day 7 (A), day 21 (B), day 30 (C) and 6 mon (D) postoperatively.

The healing process of a wound in group B depicted on day 7 (A), day 14 (B), day 21 (C) and 6 mon (D) postoperatively.