Abstract

Street Medicine is a volunteer-run initiative for low-resource healthcare settings. Formed to bridge gaps in care for persons experiencing homelessness, these organisations work to provide preventative medicine through maintenance care and follow-up. However, there are limits to what Street Medicine can accomplish given the geographical radius covered, lack of available transportation options and vulnerable sleeping locations night to night for the patients served. The subject of this case report is a middle-aged Spanish-speaking unsheltered man who began his care with a Street Medicine team. He was unable to attend medical appointments due to relocation, complicating his disease course and resulting in hospital intervention for cellulitis. Post-discharge, he stayed within radius and was treated by the street team. Increased emphasis on the effects of housing insecurity and addressing social determinants of health could prevent deterioration of manageable diseases and should be an area of active interest for Street Medicine team expansion.

Keywords: Public health, Global Health, Occupational and environmental medicine

Background

The concept of ‘Street Medicine’ originated in the early 1990s by American physician Dr Jim Withers and involves directly providing medical care to unsheltered persons experiencing homelessness (PEH).1 Street Medicine organisations are typically not regulated by a central authority and instead have different approaches to healthcare delivery. Many Street Medicine organisations are volunteer based and composed of a multidisciplinary team of physicians, medical students, ancillary providers and social workers.1 The voluntary nature of these organisations means that funding relies on charitable contributions and grants, with limited institutional support. As a result, medical supplies and medications may be insufficient to properly address health issues encountered.

Connecting patients from extraclinical to clinical settings is primarily composed of weekly outreach whereby medical care is provided at locations such as parks, bridges and encampments. Frequent concerns of PEH during this outreach are skin diseases such as rashes and wounds.2 Specialists like dermatologists are often required to manage complicated disease presentations but the initial and most crucial step is building rapport with this population. Sustained outreach can therefore be instrumental in recruiting this vulnerable patient cohort.1 A suggested engagement approach by Street Medicine organisations involves the eventual addition of ‘care coordinators’ who are social workers well versed in shelters and low-income health resources for PEH (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Summarised engagement approach employed by Street Medicine organisations. Longitudinal care has the best outcomes but is often complicated by high attrition rates. (Illustrated and prepared using Microsoft PowerPoint by Taha Faiz Rasul)

While many medical issues encountered by PEH are manageable at first, the lack of access to primary care and preventative treatment leads to health deterioration, ultimately resulting in hospital visits for disease exacerbation.3 The present case exemplifies this common phenomenon but with a novel resolution. The case also highlights the vulnerabilities faced by unsheltered PEH and how housing insecurity can result in illnesses worsening until they require hospitalisation. The inclusion of a holistic picture of each patient by evaluating housing instability, nutrition, mental health and overall functional status is how Street Medicine aims to improve delivery of care to a vulnerable population.

Case presentation

A Spanish-speaking man in his 50s was encountered during regular street outreach in South-Eastern Florida. His chief report was pain, itching and swelling prominently on his left leg. He faced housing insecurity and oscillated between living with estranged family or in squatter-driven encampments. The patient fractured his left ankle 7 months prior and was a wheelchair user. Due to physical and financial constraints, he was unable to follow up with his surgeon or primary physician post-fracture fixation. His medical history was also significant for diabetes, alcohol use disorder, cirrhosis and hypertension.

Physical examination revealed his left leg was swollen with visible oedema, skin cracking and fissuring (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Initial photograph of left ankle. Discrete, circumferential patches on the lower leg as well as erythematous and scaly skin. Additional scale was noted on pruritic areas. The bandage was covering a superficial erosion whose origin was not known to the patient.

Due to diagnostic uncertainty, a volunteer dermatologist was consulted via telehealth and gave the impression of venous stasis dermatitis exacerbated by prolonged immobility. He was provided on-hand supplies including wound dressings, compression wraps, topical emollients and hydrocortisone cream. Due to clinical severity being past the point of conservative management, he was recommended seeking additional clinical care immediately. During the initial encounter, the patient provided written consent for the Street Medicine team to remain involved in his care, including electronic medical record access to his charts and the ability to contact physician teams in the event of hospitalisation.

By using charitable clinic resources and leveraging physician connections, he was promptly scheduled for high-priority appointments with his surgeon and primary provider as well as street-based follow-up in 1 week (figure 3). He was unable to make the primary care or surgery clinic due to mobility limitations. During follow-up, his condition worsened considerably: his left ankle was considerably more swollen and erythematous, and he reported significant pain alongside subjective fevers. His pain persisted after self-treatment with acetaminophen. Considering risks of soft tissue disease, the decision was made to transport him to the emergency department (ED).

Figure 3.

Flow chart of the timeline from injury to presentation. (Illustrated and prepared using Google documents draw feature by Taha Faiz Rasul).

Upon arrival to the ED, his blood pressure was 104/65 mm Hg, heart rate 67 beats/min and temperature of 36.7°C. His physical examination displayed swelling, erythema and tenderness to palpation on the left lower extremity (figure 4). An approximate 3×8 cm ulcer on the left lateral malleolus was noted.

Figure 4.

Left lower extremity at admission. Notice the 3×8 cm superficial ulceration as well as oedema and erythema. This is the same spot previously bandaged.

Initial laboratory studies included a comprehensive metabolic panel as well as a complete blood count (CBC). Details can be found in table 1.

Table 1.

Notable laboratory studies on initial admission

| Laboratory test | Patient values | Reference ranges |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 184 | 70–100 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 1.7 | 0.1–1.2 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase (units/L) | 79 | 5–40 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (units/L) | 38 | 7–56 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 248 | 44–147 |

| Lactic acid (mmol/L) | 3.1 | 0.5–2.2 |

| C reactive protein (mg/L) | 1.1 | <1.0 |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (mm/hour) | 36 | 1–13: males 1–20: females |

| White cell count (109/L) | 11.5 | 4.5–11.0 |

Differential diagnosis stems primarily from infectious aetiology, although non-infectious causes had to be ruled out. Lipodermatosclerosis is an inflammatory condition that is commonly associated with venous stasis dermatitis. This is due to increased leucocyte migration into tissue surrounding venous stasis. The acute phase may often mimic cellulitis, accompanied by erythema, pain, itching and oedema. However, laboratory findings such as leucocytosis and systemic inflammation via erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C reactive protein (CRP) would not be expected.

Cellulitis was suspected due to the progressive pain, erythema and swelling on his leg. A systemic inflammatory condition was inferred by elevated lactate, ESR, CRP and leucocytosis, which pointed towards cellulitis in the setting of pre-existing dermatitis. Most cases of cellulitis are accompanied by leucocytosis, which was demonstrated on the patient’s CBC. Based on his clinical presentation and laboratory findings, his probable cellulitis was immediately treated with empirical antibiotics. Cefepime 2 g two times per day and vancomycin 1 mg two times per day were administered to cover gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria as well as methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Regular wound care and weight-bearing physical therapy were also provided. His condition improved and he was discharged from the hospital after 5 days.

The patient was discharged temporarily to a family member’s house with instructions to follow up at outpatient clinics for further management. Due to conflicts from alcohol use, he was unable to stay housed long term with his family. His unstable housing situation and risk disease relapse necessitated close follow-up by Street Medicine providers. During outreach 1 week later, he was immediately scheduled for outpatient primary care follow-up. Additionally, social workers in the team helped move forward the process of Medicaid enrolment in addition to applications for disability payments and food stamps. In discussing his care with the Street Medicine team, he displayed limited understanding of the next best steps to manage his health concerns. He was provided counselling on his medical conditions and how to appropriately manage them. Using a teach-back method with providers fluent in Spanish, his understanding of his current health condition improved, and questions were addressed. Referrals to support groups for low-income patients suffering from alcohol use disorder were also provided and extra emphasis was placed on addressing this problem in a timely manner. The total time elapsed between initial and follow-up Street Medicine visits was approximately 3 weeks. His venous stasis dermatitis continues to be managed during weekly street-based evaluations where he is provided compression bandages and socks to prevent recurrence. At these appointments, he is also treated by the Street Medicine team of multidisciplinary providers including physicians and social workers with a goal of continuing treatment and addressing social determinants to improve his overall health.

Global health problem list

Homelessness and social determinants of health.

A cycle of deterioration starting with a fracture.

Health literacy and cultural competence.

Improving delivery of care to unsheltered patients.

Intersections of substance use, mental health, poverty and marginalisation.

Gauging the utility of Street Medicine and similar programmes.

Global health problem analysis

Homelessness and social determinants of health

According to the WHO, social determinants play a major role in the overall health outcomes of patients.4 Housing insecurity was likely a major social determinant which led to the deterioration of the patient’s health, although other factors like health literacy, poverty and substance use certainly contributed. Basic shelter has been shown to greatly improve the physical and psychological well-being of PEH.5 The rough street environment is high risk for the development of skin lesions which can act as a nidus for downstream subcutaneous infections.6 Cellulitis particularly is a common skin complication resulting in hospital admission among PEH.7 The lack of public funding for homeless shelters as well as encampment-clearing policies from public land further contribute to housing instability for PEH.8 From a medical perspective, personal belongings such as medical instructions and medications may be lost regularly due to theft or encampment clearing. This has a net negative effect on appointment adherence and ability to care for chronic health conditions.

A cycle of deterioration starting with a fracture

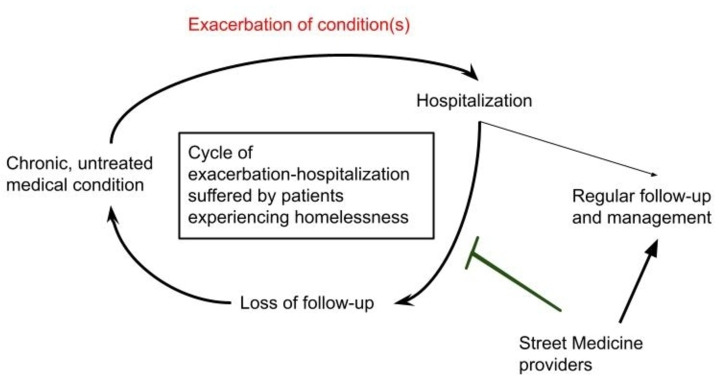

Our patient was housing insecure and unable to manage his chronic health conditions. His orthopaedic injury 7 months prior and surgical fixation through trauma surgery were completed in a timely manner, but a lack of appropriate follow-up started the cycle of deterioration which would eventually lead to hospitalisation again. After initial discharge post-fracture, the patient’s need for shelter made his daily location unpredictable and he was lost to follow-up care (figure 5). The first 3–8 weeks after surgical fixation are crucial in adequate healing of the bone defect and regular follow-up care is essential.9 Due to being unable to access services like physical therapy, he could not improve his mobility status and remained a wheelchair user. Additionally, his immobility contributed to his venous stasis, dermatitis and eventually cellulitis (figure 5).10 Ultimately, through a series of compounding events, lack of stable shelter after surgery discharge led to rehospitalisation. This may represent the increased vulnerability suffered by PEH where an initial injury can lead to a downward spiral of health.

Figure 5.

Illustrated flow diagram representing the potential role of Street Medicine organisations in improving longitudinal care among persons experiencing homelessness, particularly after hospital discharges for acute exacerbation of chronic conditions. (Illustrated and prepared using Google documents draw feature by Taha Faiz Rasul).

Health literacy and cultural competence

Even past his unsheltered status, the patient had other social determinants that resulted in unique circumstances complicating his care. He could only communicate in Spanish, requiring the use of interpreter services in the hospital. As a result, he may not have completely understood the post-discharge follow-up instructions as well as his new medication regimen. This was evidenced when Street Medicine providers had to re-explain his diagnoses and arrange transportation to his outpatient appointments after he was discharged. Lack of health literacy is a pervasive issue among PEH and represents a significant barrier to care.11 12 Street Medicine organisations can work with PEH during their transition out of the hospital to help educate them on long-term health management strategies. Expanded education on appropriate follow-up care can effectively reduce disease burden for PEH and decrease the risk of rehospitalisation.13

Improving delivery of care to unsheltered patients

Street Medicine providers can fill a needed transition of care role for PEH. Hospitals do not necessarily have mechanisms in place to stay in contact with these patients after discharge.11 Many times, patient files only contain a single phone number or home address as a means of contact, which for PEH would have several notable limitations in communication channels.11 Losing a phone or not having a permanent address makes follow-up difficult if not impossible. Street Medicine teams do not rely on such structural methods of communication and deliver care face-to-face with PEH. By routinely covering a radius during times made known to the community via consistency and word of mouth, PEH know exactly where to find the mobile clinic to obtain care. Engaging with PEH where they reside is an important tool for maintaining contact, thus reducing loss to follow-up.

The care initially provided to the patient was in resource-limited settings and included medications and supplies which were on hand. Whereas higher potency topical steroids like triamcinolone were needed to properly address the venous stasis-induced dermatitis, the less potent hydrocortisone was likely insufficient to adequately reduce the inflammation. Additionally, topical antibiotic ointments have some utility in venous dermatitis management but over-the-counter preparations such as triple antibiotics (neomycin, bacitracin and polymyxin b) have a high risk of triggering contact dermatitis.14 15 Had care been initially offered in a first-line manner, there may have been more effective resolution of his condition without the need of hospitalisation. This was more of a resource limitation than a lack of knowledge, as some of the evaluating providers were familiar with standard-of-care management for this condition.

Our patient, though still vulnerable, had more of a medical support system than many other PEH. Street Medicine providers were in contact with him before, during and after his hospitalisation. This longitudinal model could provide continuous care to patients who would otherwise fall in the gaps of the traditional medical system. Months after hospital discharge, Street Medicine providers continue to evaluate his conditions and provide maintenance care, often in a resource-limited setting. The long-term follow-up will be crucial for this patient, as it determines whether his issues of venous stasis and alcohol use will truly be treated or if he will relapse. Increased funding and expansion of Street Medicine programmes, including efforts to help patients find stable shelter, could improve health outcomes in PEH with chronic conditions.

Factors essential to patients and subsequent delivery of services hinge around accessibility, especially for individuals with financial limitations. This must be balanced with traditional metrics of quality of care such as clinical quality, perceived quality and responsiveness.16 The delivery of care for vulnerable patients must therefore be accessible without sacrificing quality, both objectively and subjectively. This is because perception of quality can be a function of power differentials in society. A 2006 study conducted in Russia found that pregnant women suffering from poverty were more likely to undergo pregnancy-related procedures as their low social status prevented them from being able to negotiate treatment plans in line with their goals of care.17 Hence, power dynamics may be overlooked in the case of complex patients but are essential in providing quality care to PEH with respect to their choices and health priorities.

Intersections of substance use, mental health, poverty and marginalisation

Homelessness does not often exist in a vacuum. Rather, it can be thought of as an intersection of many social determinants of health. Mental health concerns which may coexist with substance use disorders are perhaps the most challenging to treat, especially in the context of low resources. When combined with abject poverty and a lack of social support, it becomes exceedingly difficult to exit the cycle of homelessness. Therefore, our patient’s cellulitis is only one aspect of the overall fragile circumstances that led to his worsening health. Deeper issues of mistrust of the medical system may be common among PEH due to previous traumatic experiences.18

Therefore, keeping all of these in mind is essential in better understanding and building rapport with this patient population. Some studies have found that trust and healthcare utilisation are often directly proportional. It would make sense that PEH having limited healthcare access would deteriorate their level of trust in providers and institutions alike. Low levels of trust in primary care have also been correlated with high rates of ED use. Cultural factors are also important for providers as patients of different backgrounds may have different expectations of the healthcare system in general. Instead of the previously adopted notion of cultural competency, cultural safety is defined as improvement in care through addressing differences, considering power dynamics and allowing the patients themselves to dictate the setting of the clinical encounter. Cultural safety therefore is a preferable goal rather than simple cultural competency.19 This is because the burden of change is on the provider, society or institution rather than the patient. For vulnerable populations like recent immigrants or PEH, approaching their care from a cultural safety perspective is necessary to ensure they receive appropriate care with respect to their cultural identities and rights.

The true role of Street Medicine providers in caring for the underserved is not simply the ability to see PEH in an extraclinical setting. More importantly, it lies in the ability to holistically evaluate the most vulnerable patients in society, taking into account their shelter status, background, social support, and other factors directly or indirectly influencing their health. However, Street Medicine should not occupy a permanent role in patient care, but rather be a vehicle for advocacy to allow PEH to get the medical care they desperately deserve.

Gauging the utility of Street Medicine and similar programmes

The fundamental objective of programmes such as Street Medicine is the establishment of long-term primary care for uninsured and underinsured patients. Gauging the effectiveness of these initiatives can be difficult as they share challenges such as sparse funding, high attrition rates and a lack of governmental support.20 Paradoxically, these patients are more likely to suffer from advanced stages of disease and more often resort to emergency rooms for treatment.21 Successes of programmes like Street Medicine may be seen as a function of how many uninsured or underinsured patients can be seen on a longitudinal basis and resulting cost savings for emergency rooms. Preliminary data from a Los Angeles-based Street Medicine organisation demonstrated a high morbidity patient cohort, with an average of 2.7 hospital admissions per patient per year.22 Additionally, the most common conditions encountered were congestive heart failure exacerbation (19.4%) and cellulitis (6.8%). These patients were already admitted to an adjacent safety net hospital and were followed by Street Medicine providers 1 week after discharge. Whereas anecdotal statements were provided about housing placement, the long-term health parameters of Street Medicine-based follow-up are not well-known.

Therefore, the novelty of such programmes and limited data on long-term outcomes require more robust data collection and analysis. An improvement in patient health parameters or cost-saving for local health systems could present a compelling argument for the further expansion of these initiatives. Other organisations involved in this work include Operation Safety Net, which is a Pennsylvania-based full-time Street Medicine programme.23 These organisations primarily care for people who use injection drugs by ‘harm reduction’ principles, which aim to decrease health consequences of behaviours without elimination of the behaviour entirely. This is accomplished by syringe exchange services, naloxone distribution and providing opioid use disorder treatments like buprenorphine.

The future of healthcare access and delivery for vulnerable populations within the USA may increasingly become intertwined with programmes like Street Medicine. An increasing amount of government funds are being allotted towards Healthcare for the Homeless (HCH) initiatives.24 These initiatives provide federal funding for community health centres providing care for Medicaid-insured clients. The process of enrolling PEH into Medicaid can be lengthy which is why these programmes make extensive use of case managers and social workers. The next logical direction for HCH could therefore be increased funding for direct, street-based outreach organisations which can connect PEH to the healthcare system by not only addressing their insurance status, but a holistic evaluation of their overall determinants of health.

Patient’s perspective.

(Translated from Spanish by Street Medicine staff member)

I was injured crossing the road last year, a car hit me and drove away. I had a terrible injury to my leg which needed surgery and I was in the hospital for quite some time. The doctor who operated on me, God bless him, encouraged me to keep elevation and compression. He also told me to get physical therapy. When I left the hospital on a wheelchair, I had nowhere to go, as my family does not let me stay due to my drinking. The street doctors have taken care of me, God bless them. My leg stayed in pain and was infected. They took me to the hospital and made sure to heal me. I want to thank them for all their help. I see them and they are always happy to help me. I have been facing many difficulties in money and food and medicines. The street doctors give me medicine and help my legs and blood pressure. I thank God that he has given me health through these doctors.

Learning points.

Persons experiencing homelessness (PEH) suffer from suboptimal skin health and are at risk of complications like cellulitis.

Pre-emptive management of these conditions can improve their overall disease burden.

A thorough history and physical examination can be employed alongside a holistic evaluation of the patient’s shelter status, mental health, poverty level and other determinants of health.

PEH are at high risk of being lost to follow-up, which can create a cycle of disease deterioration and hospitalisation.

Street Medicine providers can bridge the care of PEH from the street to the clinical setting and can maintain an appropriate level of follow-up.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the volunteers at the Miami Street Medicine institute for their tireless work in treating Miami’s unsheltered who have otherwise remained at the periphery of society. Specifically, Daniel Bergholz for leading the organisation through its most critical times and ensuring the best care to his patients both inside and outside of the hospital. We also want to thank Emily Eachus for translating and interpreting communications with our patient.

Footnotes

Contributors: TFR—manuscript preparation, initial thesis, direct patient care, image and flow chart illustration. OM—manuscript revision and corrections. AE—manuscript revision and corrections. AH—direct patient care and manuscript revision.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Case reports provide a valuable learning resource for the scientific community and can indicate areas of interest for future research. They should not be used in isolation to guide treatment choices or public health policy.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Obtained.

References

- 1.Howe EC, Buck DS, Withers J. Delivering health care on the streets: challenges and opportunities for quality management. Qual Manag Health Care 2009;18:239–46. 10.1097/QMH.0b013e3181bee2d9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stratigos AJ, Katsambas AD. Medical and cutaneous disorders associated with homelessness. Skinmed 2003;2:168–72; 10.1111/j.1540-9740.2003.01881.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baggett TP, O’Connell JJ, Singer DE, et al. The unmet health care needs of homeless adults: a national study. Am J Public Health 2010;100:1326–33. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.180109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep 2014;129 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):19–31. 10.1177/00333549141291S206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Solar O, Irwin A. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. social determinants of health discussion paper 2 (policy and practice). Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2010. Available: http://www.who.int/social_determinants/thecommission/finalreport/en/index.html [accessed 5 May 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Institute of Medicine (US) . Homelessness, health, and human needs. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US), 1988. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK218236/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis SD, Peter GS, Gómez-Marín O, et al. Risk factors for recurrent lower extremity cellulitis in a U.S. veterans medical center population. Am J Med Sci 2006;332:304–7. 10.1097/00000441-200612000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olson N, Pauly B. Homeless encampments: connecting public health and human rights. Can J Public Health 2021;112:988–91. 10.17269/s41997-021-00581-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marsell R, Einhorn TA. The biology of fracture healing. Injury 2011;42:551–5. 10.1016/j.injury.2011.03.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arpaia G, Bavera PM, Caputo D, et al. Risk of deep venous thrombosis (DVT) in bedridden or wheelchair-bound multiple sclerosis patients: a prospective study. Thromb Res 2010;125:315–7. 10.1016/j.thromres.2009.06.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jenkinson J, Wheeler A, Wong C, et al. Hospital discharge planning for people experiencing homelessness leaving acute care: a neglected issue. Healthc Policy 2020;16:14–21. 10.12927/hcpol.2020.26294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Odoh C, Vidrine JI, Businelle MS, et al. Health literacy and self-rated health among homeless adults. Health Behav Res 2019;2:13. 10.4148/2572-1836.1055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Omori DM, Potyk RP, Kroenke K. The adverse effects of hospitalization on drug regimens. Arch Intern Med 1991;151:1562–4. 10.1001/archinte.1991.00400080064011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spring S, Pratt M, Chaplin A. Contact dermatitis to topical medicaments: a retrospective chart review from the Ottawa hospital patch test clinic. Dermatitis 2012;23:210–3. 10.1097/DER.0b013e31826e443c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Draelos ZD, Rizer RL, Trookman NS. A comparison of postprocedural wound care treatments: do antibiotic-based ointments improve outcomes? J Am Acad Dermatol 2011;64(3 Suppl):S23–9. 10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van den Berk-Clark C, McGuire J. Trust in health care providers: factors predicting trust among homeless veterans over time. J Health Care Poor Underserved 2014;25:1278–90. 10.1353/hpu.2014.0115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Danishevski K, Balabanova D, McKee M, et al. Delivering babies in a time of transition in Tula, Russia. Health Policy Plan 2006;21:195–205. 10.1093/heapol/czl001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanefeld J, Powell-Jackson T, Balabanova D. Understanding and measuring quality of care: dealing with complexity. Bull World Health Organ 2017;95:368–74. 10.2471/BLT.16.179309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Curtis E, Jones R, Tipene-Leach D, et al. Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: a literature review and recommended definition. Int J Equity Health 2019;18:174. 10.1186/s12939-019-1082-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Davis K. Uninsured in America: problems and possible solutions. BMJ 2007;334:346–8. 10.1136/bmj.39091.493588.BE [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Collins SR, Davis K, Doty MM, et al. Gaps in health insurance coverage: an all-American problem. New York: Commonwealth Fund, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feldman BJ, Kim JS, Mosqueda L, et al. From the hospital to the streets: bringing care to the unsheltered homeless in los angeles. Healthc (Amst) 2021;9. 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2021.100557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frankeberger J, Gagnon K, Withers J, et al. Harm reduction principles in a street medicine program: A qualitative study. Cult Med Psychiatry 2022:1–17. 10.1007/s11013-022-09807-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zlotnick C, Zerger S, Wolfe PB. Health care for the homeless: what we have learned in the past 30 years and what’s next. Am J Public Health 2013;103 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S199–205. 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]