Introduction

It has long been recognized that immunoassays cannot accurately quantify steroid hormones such as testosterone, estradiol, and aldosterone in certain patient populations. While these immunoassays are available as US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved tests, laboratory-developed liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) assays have become the cornerstone of clinical care when low concentrations of these hormones are present in patient samples. Historically, LC-MS/MS assays have been developed and validated in clinical laboratories under the auspices of the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988 (CLIA '88). However, the Verifying Accurate Leading-edge IVCT Development Act of 2022 proposes that the validation of these LC-MS/MS assays should be reviewed by the FDA. This mini-review focuses specifically on testosterone, estradiol, and aldosterone in terms of the clinical utility of laboratory-developed LC-MS/MS assays to quantify these hormones, discussing immunoassay limitations common to all analytes, and highlighting the need for these laboratory-developed LC-MS/MS assays to remain under the purview of CLIA’88.

Testosterone

Testosterone is a steroid hormone responsible for the development of male characteristics and spermatogenesis. It circulates in the body bound to sex hormone binding globulin (∼44 % in men and 66 % in women) and albumin (∼33–54 %) [1]. A small percentage of testosterone is bound to cortisol-binding protein and alpha-1-acid glycoprotein, with the rest remaining free [1]. Clinically, total testosterone concentrations are measured in pediatric patients with ambiguous genitalia, precocious or delayed puberty; adult males with hypogonadism; and females with suspected polycystic ovarian syndrome, irregular menstrual periods, or androgen excess [[2], [3], [4]]. Further, in transgender individuals, testosterone may be measured to verify if gender-affirming therapy is successfully increasing or decreasing total testosterone concentrations [[5], [6]]. Reference intervals for testosterone vary widely depending on age and gender; however, the lower concentration of the reference interval in certain age groups can be as low as 2 ng/dL [[7], [8]].

Historically, testosterone was measured clinically by solvent extraction followed by radioimmunoassay (RIA) or by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC–MS), the latter of which required derivatization and a sample preparation step [9]. Direct immunoassays, which do not require sample preparation, were later introduced and were commonly used in clinical laboratories [9]. While this increased access to testing and the throughput of samples, it became clear that immunoassays were neither as specific nor sensitive as either RIA or mass spectrometry-based assays, due to their cross-reactivity with other analytes in the sample and differential matrix effects between patient samples [[9], [10]]. When liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) started being introduced into clinical laboratories, it was realized that testosterone could be measured using this technology without derivatization, while retaining the highly specific and sensitive quantification of GC–MS [11]. Consequently, LC-MS/MS has become the gold standard technique for measuring testosterone in certain patient populations [11].

A further complicating factor in the historical measurement of testosterone was the lack of standardization between assays designed to quantify this steroid hormone. This issue was brought to the forefront in 2007 when the Endocrine Society released a position statement acknowledging this issue and recommending improvement [9]. In response, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Center for Environmental Health, Division of Laboratory Sciences (CDC/NCEH/DLS) started the Hormone Standardization Program (HoSt), initially focusing on testosterone [12]. This program determined the desired performance specification for testosterone assays of an overall mean bias of ±6.4 % based on biological variation [13]. It then focused on developing a Candidate Reference Measurement Procedure (RMP) for testosterone using LC-MS/MS [14]. Manufacturers of immunoassays, and/or laboratories with laboratory-developed mass spectrometry assays, could then voluntarily participate in the HoSt program by comparing their method to the CDC RMP, using samples provided by the CDC for a charge. Methods that pass the desired performance specifications are then listed on the CDC website [15].

In a recent College of American Pathologists (CAP) proficiency testing survey for testosterone (Y-B 2022), it was seen that the vast majority of laboratories measured testosterone by immunoassay (n = 1558), while 40 labs measured testosterone by mass spectrometry. For laboratories that are accredited by CAP, participation in this CAP survey is compulsory if they are measuring testosterone and/or estradiol. Fig. 1 and Table 1 show the mean testosterone results for one of the survey samples (Y-06) for the five most commonly used immunoassays and the mass spectrometry peer group. It can be seen that the concentrations reported for the mass spectrometry assays and three of the immunoassays were close (84–86 ng/dL), while one of the immunoassays reported a mean result that was ∼ 11 % lower (76 ng/dL) and another immunoassay reported a result that was ∼ 6 % higher (90 ng/dL). It can also be seen that the SD of the mass spectrometry assays is wider than that of the immunoassays, which is expected since the mass spectrometry assays are all laboratory-developed, likely using different reagents and methods, while the immunoassay peer groups will all be using the same instrument and/or reagents.

Fig. 1.

Mean testosterone results of a College of American Pathologists Y-B 2022 proficiency testing survey sample for the five most commonly used immunoassay (IA) peer groups and the mass spectrometry peer group. Error bars = ±2 standard deviations.

Table 1.

Mean, standard deviation and % coefficient of variation (%CV) of testosterone results from a College of American Pathologists Y-B 2022 proficiency testing survey sample for the five most commonly used immunoassay (IA) peer groups and the mass spectrometry peer group.

| Assay number | n | Y-06 mean concentration ng/dL | Standard Deviation | %CV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IA 1 | 247 | 84.18 | 6.05 | 7.2 |

| IA 2 | 219 | 85.8 | 4.19 | 4.9 |

| IA 3 | 199 | 89.97 | 4.53 | 5 |

| IA 4 | 154 | 75.68 | 5.3 | 7 |

| IA 5 | 148 | 84.8 | 4.37 | 5.2 |

| Mass spectrometry | 40 | 83.96 | 10.28 | 12.2 |

Since participation in the CDC hormone standardization program is cost-prohibitive for some, an alternative way to measure accuracy is to participate in the voluntary Accuracy-Based Proficiency Survey for testosterone, available from CAP with target values set by the CDC RMP [16]. In a recent accuracy-based CAP proficiency testing survey for testosterone (ABS-B 2022), a total of 65 labs reported results, with 25 of the labs using mass spectrometry and the remainder using immunoassay. Table 2 lists the reported median testosterone concentrations for the five most commonly used immunoassays and for the mass spectrometry peer group, as well as the testosterone concentration determined by the CDC RMP, which was 36.7 ng/dL. As can be seen, the mass spectrometry peer group has a median of 37 ng/dL, which is very close to the CDC RMP concentration. Two of the immunoassays have medians close to the CDC RMP concentration at 38 and 40 ng/dL, respectively. However, the other immunoassays have medians that are up to 44 % different from the CDC RMP concentration. It can also be seen from Table 1 that the difference between the minimum and maximum concentrations reported for each of the methods can be significant, especially for the mass spectrometry peer group. This is likely due to differences in calibration between the testosterone mass spectrometry assays; however, it has been shown that harmonization of testosterone LC-MS/MS assays across different laboratories is possible [17].

Table 2.

Median, minimum and maximum testosterone results of a College of American Pathologists ABS-B 2022 proficiency testing survey sample for the five most commonly used immunoassay (IA) peer groups and the mass spectrometry peer group. Reference method is the CDC reference method performed by the Clinical Chemistry Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, Georgia).

| Assay number | n | ABS-06 median concentration (ng/dL) | Minimum reported concentration (ng/dL) | Maximum reported concentration (ng/dL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IA 1 | 8 | 40 | 39 | 43 |

| IA 2 | 7 | 51 | 40 | 54 |

| IA 3 | 7 | 21 | 19 | 24 |

| IA 4 | 6 | 38 | 34 | 40 |

| IA 5 | 5 | 24 | 23 | 26 |

| Mass spectrometry | 25 | 37 | 25 | 54 |

Reference method 36.7 ng/dL.

While improvements have been made in the standardization efforts for measuring testosterone, published studies still indicate inaccuracies in immunoassays compared to LC-MS/MS assays. Immunoassays tend to overestimate testosterone concentrations when they are < 100 ng/dL, which is the range in which female adult and pediatric samples tend to occur, and they underestimate concentrations when they are > 100 ng/dL [18]. Cross-reactivity of testosterone immunoassays with fetal and placental steroids, as well as dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (Fig. 2), has been implicated as a cause of the inaccuracy [[19], [20]]. In one clinical case, a pediatric patient had an unexpectedly high testosterone concentration by immunoassay, but when measured by LC-MS/MS, the result was over 85 % lower. When the sample was extracted with methanol and re-run on the immunoassay, the concentration decreased by over half, indicating the presence of an unidentified interfering substance that was not completely alleviated by adding this extraction step before immunoassay measurement [21]. Furthermore, a study on samples from newborns found that the testosterone concentration measured by two different second-generation immunoassays was overestimated compared to LC-MS/MS, particularly in the first few days after birth [22].

Fig. 2.

The steroid hormone pathway.

In patients with prostate cancer who are undergoing androgen deprivation therapy, testosterone concentrations are frequently measured to ensure adequate suppression [23]. In one study that compared testosterone concentrations measured in prostate cancer patients by LC-MS/MS and four different immunoassays, it was found that 88 % of the patient samples had testosterone concentrations below the limit of quantification for one of the immunoassays. Additionally, the testosterone concentrations were significantly higher when measured by all of the immunoassays compared to the LC-MS/MS assay, making them unsuitable for use in this patient population [23].

Estradiol

Estradiol circulates in the body bound to sex hormone-binding globulin and albumin [24]. It is clinically measured in postmenopausal breast cancer patients treated with aromatase inhibitors, pregnant patients and those using assisted reproductive technology (ART), and postmenopausal women on hormone replacement therapy [25]. Additionally, it is measured in pediatric patients in cases of precocious or delayed puberty and in males to evaluate gynecomastia and/or feminization [[25], [26]].

Like testosterone, estradiol has historically been measured by GC–MS, RIA, and more recently, by immunoassay on automated instruments [25]. However, it has been determined that automated immunoassay instruments do not accurately measure estradiol at low concentrations, nor do they have the specificity to measure only estradiol [25]. Laboratory-developed tests using LC-MS/MS have become a more common way to measure estradiol, as they offer greater ease of use than GC–MS, but still maintain sensitivity and specificity.

One of the biggest challenges in measuring estradiol is the large variation in concentrations present in different patient populations. Concentrations in breast cancer patients treated with aromatase inhibitors are < 2 pg/mL, while concentrations in patients undergoing in-vitro fertilization treatment can be up to 10,000 pg/mL [[25], [27]]. Using a laboratory-developed test such as an LC-MS/MS method can be developed specifically for the patient populations that will be tested in the laboratory, unlike an immunoassay, which is developed by the manufacturer to cover a wide range of concentrations, potentially forgoing accuracy.

In an effort to standardize estradiol quantification, this steroid hormone was added to the CDC Hormone Standardization (HoSt) program in 2014. Like testosterone, a Reference Measurement Procedure (RMP) was developed [28], and desirable method performance was established (±12.5 % bias for samples > 20 pg/mL and ±2.5 pg/mL absolute bias for samples ≤ 20 pg/mL). Successful participation in the voluntary program is documented on the CDC website [29].

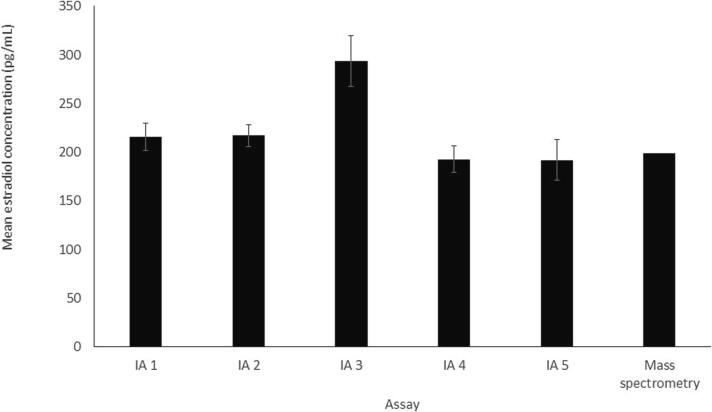

In a recent CAP proficiency testing survey for estradiol (Y-B 2022) required for CAP-accredited laboratories measuring estradiol, the majority of laboratories (n = 1481) measured estradiol by immunoassay, while only nine labs used mass spectrometry. Fig. 3 and Table 3 show the mean estradiol results for one of the survey samples (Y-06) for the five most commonly used immunoassays and the mass spectrometry peer group. It can be seen that the mean concentrations reported for all of the assays vary from 192 to 294 pg/mL, with one immunoassay reporting the highest mean value of 294 pg/mL, significantly higher than the means reported for the other assays. The mass spectrometry peer group reported a mean concentration of 199 pg/mL. Additionally, the SDs for the immunoassays were fairly large; however, due to the small number of participants, an SD was not reported for the mass spectrometry peer group. It should be noted that this CAP survey concentration is not very low, and thus, larger variation is likely at lower, clinically relevant concentrations.

Fig. 3.

Mean estradiol results of a College of American Pathologists Y-B 2022 proficiency testing survey sample for the five most commonly used immunoassay (IA) peer groups and the mass spectrometry peer group. Error bars = ±2 standard deviations (SD). SD was not available for the mass spectrometry peer group.

Table 3.

Mean, standard deviation and % coefficient of variation (%CV) of estradiol results from a College of American Pathologists Y-B 2022 proficiency testing survey sample for the five most commonly used immunoassay (IA) peer groups and the mass spectrometry peer group.

| Assay number | n | Y-06 mean concentration pg/mL | Standard Deviation | %CV |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IA 1 | 201 | 215.7 | 7.1 | 3.3 |

| IA 2 | 199 | 216.9 | 5.7 | 2.6 |

| IA 3 | 135 | 293.6 | 13.1 | 4.5 |

| IA 4 | 124 | 192.7 | 6.7 | 3.5 |

| IA 5 | 119 | 191.7 | 10.5 | 5.5 |

| Mass spectrometry | 9 | 199 | n/a | n/a |

In addition to testosterone, estradiol is also available in the voluntary Accuracy Based Proficiency Survey from CAP [16]. In a recent accuracy-based CAP proficiency testing survey for estradiol (ABS-B 2022), a total of 42 labs reported results with 12 of the labs using mass spectrometry and the remaining using immunoassay. Table 4 lists the reported median estradiol concentrations for the five most commonly used immunoassays and for the mass spectrometry peer group. It also lists the estradiol concentration determined by the CDC RMP as 27.3 pg/mL. As can be seen, the mass spectrometry peer group has a median of 25 pg/mL, which is fairly close to the CDC RMP concentration. One immunoassay had a median close to the CDC RMP concentration at 29 pg/mL, but the other immunoassays had medians that were up to 28 % different from the CDC RMP concentration. Table 2 also shows that the difference between the minimum and maximum concentration reported for each of the methods can be significant, especially for some of the immunoassay peer groups. Improvements have been made in the harmonization of estradiol concentrations, but it is clear that there is still room for improvement.

Table 4.

Median, minimum and maximum estradiol results of a College of American Pathologists ABS-B 2022 proficiency testing survey sample for the five most commonly used immunoassay (IA) peer groups and the mass spectrometry peer group. Reference method is the CDC reference method performed by the Clinical Chemistry Branch, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Atlanta, Georgia).

| Assay number | n | ABS-04 median concentration (pg/mL) | Minimum reported concentration (pg/mL) | Maximum reported concentration (pg/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IA 1 | 7 | 33 | 15 | 36 |

| IA 2 | 6 | 29 | 25 | 36 |

| IA 3 | 4 | 34 | 31 | 34 |

| IA 4 | 3 | 31 | 28 | 35 |

| IA 5 | 3 | 35 | 30 | 37 |

| Mass spectrometry | 12 | 25 | 23 | 28 |

Reference Concentration 27.3 pg/mL.

Another challenge in accurately measuring estradiol is the large number of endogenous estradiol metabolites that are present and can cross-react with immunoassays; over 100 of these have been identified [30]. Additionally, endogenous conjugated estrogens like estrone sulfate, which are present at high concentrations, may also cross-react with estradiol immunoassays [30].

Estradiol is commonly measured during treatment with exogenous estradiol, for example, in transgender women. In one study, three immunoassays—including one first-generation and one second-generation immunoassay from the same manufacturer—were used to measure estradiol concentrations in 89 transgender patients undergoing feminizing treatment with estradiol and compared with a LC-MS/MS assay [31]. It was found that in the transgender patients taking oral estrogen, the immunoassays underestimated or overestimated the estradiol concentration by up to 40 % compared to LC-MS/MS; however, this bias was reduced in patients taking the estradiol patch or injections (up to 22 %) [31]. Additionally, a postmenopausal breast cancer patient treated with fulvestrant, an estrogen receptor antagonist, had gradually increasing estradiol concentrations measured by immunoassay. When the same samples were measured by LC-MS/MS, the estradiol concentrations were in the postmenopausal reference interval, as expected [32]. As can be appreciated, the added specificity available through use of LC-MS/MS mitigates the issues that immunoassays may have with cross-reactivity.

Aromatase converts testosterone to estradiol (Fig. 2). In postmenopausal breast cancer patients treated with aromatase inhibitors, estradiol is measured to ensure adequate suppression of this conversion, which leads to improved clinical outcomes. In a study of 77 postmenopausal breast cancer patients treated with an aromatase inhibitor, LC-MS/MS found that 70 % of the samples had estradiol concentrations of < 5 pg/mL [33]. However, two immunoassays could not detect down to 5 pg/mL, three immunoassays gave concentrations substantially higher than those from LC-MS/MS, and the sixth immunoassay significantly underestimated the estradiol concentrations compared to LC-MS/MS [33]. Thus, using the immunoassays to measure estradiol in this group of patients could lead to misinformed clinical decisions.

Estradiol concentrations in adult males are normally below 30 pg/mL and decrease with age. In pediatric patients, the lower limit of the normal reference interval can be as low as 1 pg/mL [25]. Therefore, LC-MS/MS is essential for estradiol quantification in these populations due to its improved sensitivity and specificity compared to immunoassays. In one study of adult males, estradiol immunoassay concentrations and LC-MS/MS concentrations measured on the same samples showed only poor to moderate correlation [34]. Additionally, the immunoassay estradiol concentration appeared to be correlated to a low extent with the C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration, whereas the LC-MS/MS estradiol concentration was not. This suggested a possible interference in the immunoassay by CRP or a CRP-associated factor [34].

Aldosterone

Aldosterone circulates predominantly bound to albumin [24] and is measured clinically when screening for primary aldosteronism, a condition in which aldosterone production occurs independently of angiotensin II stimulation [35]. Historically, aldosterone was measured using extraction followed by RIA; however, due to increased automation, immunoassay was more recently employed [36]. Nonetheless, LC-MS/MS has become the recommended way to measure aldosterone to ensure adequate sensitivity and specificity [35].

One challenge for aldosterone quantification is that the normal reference interval for this hormone in pediatric patients can be as low as 1 ng/dL. In the most recent CAP proficiency testing survey for aldosterone (RAP-B 2022), only 94 laboratories reported results, 79 of which reported results from immunoassays and 15 from mass spectrometry assays. For one of the proficiency survey samples (RAP-06), the mean reported concentration across different methodologies ranged from 0.5 to 24.80 ng/dL—a clinically significant difference that could impact patient care. (It should be noted, however, that the matrix of the CAP survey samples can be problematic for some assays in some cases, yet this issue is not seen in patient samples). Moreover, there are far fewer laboratories running aldosterone methods, resulting in some of the peer groups for the CAP surveys being very small, especially for the lower concentration samples, and the coefficient of variation between labs running the same method being high. Additionally, unlike testosterone and estradiol, there is no CDC RMP or CAP accuracy-based proficiency survey for aldosterone, making it harder for both immunoassay manufacturers and laboratories developing LC-MS/MS assays to ensure the accuracy of their methods.

A few studies have shown that immunoassays tend to yield higher aldosterone concentrations than LC-MS/MS when measuring the same samples [[37], [38]]. In one case report, a patient had high aldosterone concentrations measured by immunoassay, resulting in adrenal vein sampling to confirm a diagnosis of primary aldosteronism and an indication for left adrenal gland removal [39]. However, upon measuring the same samples by LC-MS/MS as part of a clinical research protocol, it was discovered that the aldosterone concentrations were in fact lower, indicating misdiagnosis [39]. Issues with aldosterone measurement by immunoassay are thought to be due to the numerous endogenous compounds that can potentially interfere with aldosterone quantification [40]. It has also been shown that in patients with renal impairment, aldosterone concentrations can be significantly overestimated using immunoassays, likely due to cross-reactivity with polar metabolites [[40], [41]]. However, this overestimation is eliminated when the same patient samples are subjected to sample preparation and LC-MS/MS analysis [[37], [40]].

Common immunoassay limitations mitigated by laboratory developed LC-MS/MS assays

Clinical laboratories have complete control over the development and calibration of LC-MS/MS assays. They can test and optimize accuracy using the CDC Hormone Standardization Program, the CAP accuracy-based proficiency samples, or using the Standard Reference Material (SRM) available from the National Institutes of Science and Technology (NIST), all of which have accurately assigned testosterone or estradiol concentrations [[18], [42]]. In contrast, if using an FDA-approved immunoassay, laboratories rely on the manufacturer to determine accurate calibration during method development and validation. Proficiency testing results show concentrations can vary significantly depending on the immunoassay manufacturer used. When a laboratory has a specific manufacturer's equipment, laboratory directors may not be able to purchase different equipment to improve accuracy, unless the lab adds mass spectrometry testing.

While immunoassays are designed to quantify-one analyte at a time, they can have issues with specificity when measuring steroid hormones due to their similarities in structure [[21], [30], [40]]. To mitigate this, LC-MS/MS assays are used to detect specific masses for each analyte in a method. However, this technique cannot distinguish between isomers, for example, testosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone so the analytes need to be separated in time on the liquid chromatography column before they enter the mass spectrometer in order to quantify them separately [[43], [44], [45]]. Additionally, ion ratios for each analyte in the method can be used to add another layer of specificity. For each analyte in a particular LC-MS/MS method, two mass transitions are utilized and then the ratio of the peak areas of these mass transitions can be calculated. These ratios should remain consistent in all samples including calibrators, quality control materials and patient samples. If the ion ratio for a particular patient sample is not consistent with the other samples, it could be indicative of an interference and the result for that patient sample would not be reported [43].

As described above, immunoassays are designed to quantify-one analyte at a time; however, one of the major advantages of using LC-MS/MS is that it is possible to develop assays that measure multiple analytes at once. Steroid hormone panels are a common example of this [[44], [45]]. When using panels, the time it takes to perform the sample preparation required before LC-MS/MS is similar to measuring single analytes, so panels can decrease hands-on time; however, the chromatographic method may need to be lengthened so that any necessary separation of analytes on the chromatography column before they enter the mass spectrometer can be achieved [[44], [45]].

The presence of heterophile antibodies is a well-known phenomenon that can affect immunoassay quantification [46]. In one report, a female patient's testosterone concentration was falsely elevated when measured by immunoassay, but the concentration was normal when the same sample was measured by a LC-MS/MS assay [47]. Another report revealed that anti-bovine alkaline phosphatase antibodies in a patient sample interfered with an immunoassay measurement that utilizes bovine alkaline phosphatase in the assay reagent for amplification [48]. Additionally, a third report described a patient whose persistently elevated estradiol concentration measured by immunoassay led to an oncology work-up for a granulosa cell tumor of the ovary, including laparoscopy surgery and considerable stress to the patient [49]. After benign pathology results were reported, the clinicians suspected a false elevation and used a different immunoassay, which gave estradiol concentrations within the normal reference interval. While no specific cause for the falsely elevated estradiol concentrations with the initial immunoassay was determined, it was postulated to be a heterophile antibody [49]. LC-MS/MS assays, on the other hand, can provide accurate results in the presence of heterophile antibodies, as they do not affect quantification by this methodology.

Another issue that has recently come to light is biotin (vitamin B7) interference in certain immunoassays [[50], [51]]. Biotin, an over-the-counter supplement used to strengthen nails and hair, is becoming more common, and supraphysiological high dose biotin has been used in clinical trials to try to slow down the progression of multiple sclerosis [52]. This interference is analytical, where biotin in the patient sample can lead to falsely elevated results in a competitive immunoassay design, and falsely low results in a non-competitive immunoassay design that uses streptavidin binding in the detection mechanism. One study found that approximately 7.4 % of Emergency Department patients had biotin concentrations of ≥ 10 ng/mL [53]. A case report documented that specific immunoassays for testosterone and estradiol gave falsely increased concentrations of up to 3-fold and 138-fold, respectively, in a newborn treated with high dose biotin [54]. In another study, the authors found that when spiking pooled patient serum with biotin, there was a positive bias for quantification of low levels of aldosterone of up to 3484 % in the presence of very high concentrations of 500 ng/mL biotin in one immunoassay [55]. Due to the specificity of LC-MS/MS assays, biotin does not cause interference even at high concentrations. Although immunoassay manufacturers have developed mitigation strategies to reduce the potential interference, reformulation of immunoassay reagents can take some time. Therefore, laboratorians and clinicians should be mindful about potential biotin interference in laboratory tests, and patients should alert their clinician if they are taking high dose biotin [51].

Conclusion

LC-MS/MS is a highly complex but powerful technique, and laboratories wishing to use this technique for clinical testing of steroid hormones are required to develop and clinically validate the assay themselves as, to date, there are no FDA-approved assays for any steroid hormones, including testosterone, estradiol, and aldosterone. The clinical validation is currently performed under the purview of the Clinical Laboratory Improvements Amendments of 1988, whereby laboratories are required to show that the LC-MS/MS method meets the performance criteria required for clinical testing in terms of analytical validity—including documentation of linearity, accuracy, imprecision, sensitivity, specificity, matrix effects, carryover, reportable range, and reference intervals, among others. If a laboratory were to submit an LC-MS/MS assay to the FDA for approval, extra data would be required, including broader analytical validity and proof of clinical validity, as well as a significant cost associated with this submission. Further, the submission to the FDA must occur before the LC-MS/MS assay is used in the laboratory, which would delay implementation and affect patient care. If the CLIA validation avenue was not available, as proposed by the Verifying Accurate Leading-edge IVCT Development Act of 2022 (VALID), as can be appreciated for the specific steroid hormones listed above, laboratories may have to use subpar immunoassays to measure these hormones in their patients, if clinically indicated, potentially leading to misdiagnosis and mistreatment.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of “MSACL”.

References

- 1.Jasuja R., Pencina K.M., Peng L., Bhasin S. Accurate measurement and harmonized reference ranges for total and free testosterone levels. Endocrinol. Metab. Clin. North Am. 2022;51:63–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2021.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oliveira L.R., Longui C.A., Fuaragna-Filho G., Costa J.L., Lanaro R., Silva D.A., Chiamolera M.I., de Mello M.P., Morcillo A.M., Maciel-Guerra A.T., Guerra-Junior G. Androgens by immunoassay and mass spectrometry in children with 46, XY disorder of sex development. Endocr. Connect. 2020;9(11):1085–1094. doi: 10.1530/EC-20-0454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bhasin S., Brito J.P., Cunningham G.R., Hayes F.J., Hodis H.N., Matsumoto A.M., Snyder P.J., Swerdloff R.S., Wu F.C., Yialamas M.A. Testosterone therapy in men with hypogonadism: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018;103(5):1715–1744. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-00229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Martin K.A., Anderson R.R., Chang R.J., Ehrmann D.A., Lobo R.A., Murad M.H., Pugeat M.M., Rosenfield R.L. Evaluation and treatment of hirsutism in premenopausal women: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2018;103(4):1233–1257. doi: 10.1210/jc.2018-00241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greene D.N., Schmidt R.L., Winston-McPherson G., Rongitsch J., Imborek K.L., Dickerson J.A., Drees J.C., Humble R.M., Nisly N., Dole N.J., Dane S.K., Frerichs J., Krasowski M.D. Reproductive endocrinology reference intervals for transgender men on stable hormone therapy. J. Appl. Lab. Med. 2021;6(1):41–50. doi: 10.1093/jalm/jfaa169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Greene D.N., Schmidt R.L., Winston-McPherson G., Rongitsch J., Imborek K.L., Dickerson J.A., Drees J.C., Humble R.M., Nisly N., Dole N.J., Dane S.K., Frerichs J., Krasowski M.D. Reproductive endocrinology reference intervals for transgender women on stable hormone therapy. J. Appl. Lab. Med. 2021;6(1):15–26. doi: 10.1093/jalm/jfaa028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Salameh W.A., Redor-Goldman M.M., Clarke N.J., Reitz R.E., Caulfield M.P. Validation of a total testosterone assay using high-turbulence liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry: total and free testosterone reference ranges. Steroids. 2010;75:169–175. doi: 10.1016/j.steroids.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kushnir M.M., Blamires T., Rockwood A.L., Roberts W.L., Yue B., Erdogan E., Bunker A.M., Meikle A.W. Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry assay for androstenedione, dehydroepiandrosterone and testosterone with pediatric and adult reference intervals. Clin. Chem. 2010;56(7):1138–1147. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.143222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosner W., Auchus R.J., Aziz R., Sluss P.M., Raff H. Position statement: utility, limitations, and pitfalls in measuring testosterone: an Endocrine Society position statement. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2007;92(2):405–413. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taieb J., Mathian B., Millot F., Patricot M.C., Mathieu E., Queyrel N., Lacroiz I., Somma-Delpero C., Boudou P. Testosterone measured by 10 immunoassays and by isotope-dilution gas chromatography-mass spectrometry in sera from 116 men, women, and children. Clin. Chem. 2003;49(8):1381–1395. doi: 10.1373/49.8.1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stanczyk F.Z., Clarke N.J. Advantages and challenges of mass spectrometry assays for steroid hormones. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010;121:491–495. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vesper H.W., Botelho J.C. Standardization of testosterone measurements in humans. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2010;121(3–5):513–519. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2010.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yun Y.M., Botelho J.C., Chandler D.W., Katayev A., Roberts W.L., Stanczyk F.Z., Vesper H.W., Nakamoto J.M., Garibaldi L., Clarke N.J., Fitzgerald R.L. Performance criteria for testosterone measurements based on biological variation in adult males: Recommendations from the Partnership for the Accurate Testing of Hormones. Clin. Chem. 2012;58(12):1703–1710. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.186569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Botelho J.C., Shacklady C., Cooper H.C., Tai S.S.C., Van Uytfanghe K., Thienpont L.M., Vesper H.W. Isotope-dilution liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry candidate reference method for total testosterone in human serum. Clin. Chem. 2013;59(2):372–380. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2012.190934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Testosterone Hormone Standardization Program list of certified participants. https://www.cdc.gov/labstandards/pdf/hs/CDC_Certified_Testosterone_Assays-508.pdf (accessed December 6th 2022).

- 16.College of American Pathologists Accuracy-based Proficiency Testing Program for Testosterone, Estradiol - ABS. https://estore.cap.org/OA_HTML/xxCAPibeCCtpItmDspRte.jsp?section=10763&item=744608&sitex=10020:22372:US (accessed December 6th 2022).

- 17.French D., Drees J., Stone J.A., Holmes D.T., van der Gugten J.G. Comparison of four clinically validated testosterone LC-MS/MS assays: Harmonization is an attainable goal. Clin. Mass Spectrom. 2018;11:12–20. doi: 10.1016/j.clinms.2018.11.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi J., Bird R., Schmeling M.W., Hoofnagle A.N. Using mass spectrometry to overcome the longstanding inaccuracy of a commercially-available clinical testosterone immunoassay. J. Chromatogr. B. 2021;1183 doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2021.122969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fuqua J.S., Sher E.S., Migeon C.J., Berkovitz G.D. Assay of plasma testosterone during the first six months of life: importance of chromatographic purification of steroids. Clin. Chem. 1995;41(8 pt1):1146–1149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Warner M.H., Kane J.W., Atkin S.L., Kilpatrick E.S. Dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate interferes with the Abbott Architect direct immunoassay for testosterone. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2006;43(Pt3):196–199. doi: 10.1258/000456306776865034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cresta F., Arcuri L., Bianchin S., Castellani C., Casciaro R., Cavedagna T.M., Maghnie M., Barco S., Cangemi G. A case of interference in testosterone, DHEA-S and progesterone measurements by second generation immunoassays. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2021;59(7):e275–e277. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2020-1786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hamer H.M., Finken M.J.J., van Herwaarden A.E., du Toit T., Swart A.C., Heijboer A.C. Falsely elevated plasma testosterone concentrations in neonates: importance of LC-MS/MS measurements. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2018;56(6):e141–e143. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2017-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Winden L.J., Lentjes E.G.W.M., Demir A.Y., Huijgen J.H., Berman A.M., van der Poel H.G., van Rossum H.H. Testosterone analysis in castrated prostate cancer patients: suitability of the castration cut-off and analytical accuracy of the present-day clinical immunoassays. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2022;60(10):1661–1668. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2022-0506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hammond G.L. Plasma steroid-binding proteins: primary gatekeepers of steroid hormone action. J. Endocrinol. 2016;230(1):R13–R25. doi: 10.1530/JOE-16-0070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosner W., Hankinson S.E., Sluss P.M., Vesper H.W., Wierman M.E. Challenges to the measurement of estradiol: an Endocrine Society Position Statement. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;98(4):1376–1387. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanakis G.A., Nordkap L., Bang A.K., Calogero A.E., Bártfai G., Corona G., Forti G., Toppari J., Goulis D.G., Jørgensen N. EAA clinical practice guidelines – gynecomastia evaluation and management. Andrology. 2019;7(6):778–793. doi: 10.1111/andr.12636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stanczyk F.Z., Clarke N.J. Measurement of estradiol – challenges ahead. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2014;99(1):56–58. doi: 10.1210/jc.2013-2905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Botelho J.C., Ribera A., Cooper H.C., Vesper H.W. Evaluation of an isotope dilution HPLC Tandem Mass Spectrometry Candidate Reference Measurement Procedure for Total 17-β estradiol in human serum. Anal. Chem. 2016;88(22):11123–11129. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b03220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Estradiol Hormone Standardization Program list of certified participants. https://www.cdc.gov/labstandards/pdf/hs/CDC_Certified_Estradiol_Procedures-508.pdf (Accessed December 6th 2022).

- 30.Stanczyk F.Z., Jurow J., Hsing A.W. Limitations of direct immunoassays for measuring estradiol levels in postmenopausal women and men in epidemiologic studies. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2010;19(4):903–906. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cirrincione L.R., Crews B.O., Dickerson J.A., Krasowski M.D., Rongitsch J., Imborek K.L., Goldstein Z., Greene D.N. Oral estrogen leads to falsely low concentrations of estradiol in a common immunoassay. Endocr. Connect. 2022;11:e210550. doi: 10.1530/EC-21-0550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ding J., Cao Y., Guo Y. Fulvestrant may falsely increase 17β-estradiol levels in immunoassays: a case report of a 57-year-old postmenopausal patient with recurrent estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022;12 doi: 10.3389/fonc.2022.832763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaque J., Macdonald H., Brueggmann D., Patel S.K., Azen C., Clarke N., Stanczyk F.Z. Deficiencies in immunoassay methods used to monitor serum estradiol levels during aromatase inhibitor treatment in postmenopausal breast cancer patients. Springerplus. 2013;2:5. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ohlsson C., Nilsson M.E., Tivesten A., Ryberg H., Mellström D., Karlsson M.K., Ljunggren O., Labrie F., Orwoll E.S., Lee D.M., Pye S.R., O’Neill T.W., Finn J.D., Adams J.E., Ward K.A., Boonen S., Bartfai G., Casanueva F.F., Forti G., Giwercman A., Han T.S., Huhtaniemi I.T., Kula K., Lean M.E.J., Pendleton N., Punab M., Vanderschueren D., Wu F.C.W., the EMAS Study Group, Vandenput L. Comparisons of immunoassay and mass spectrometry measurements of serum estradiol levels and their influence on clinical association studies in men. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013;98(6):E1097–E1102. doi: 10.1210/jc.2012-3861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Funder J.W., Carey R.M., Mantero F., Murad M.H., Reincke M., Shibata H., Stowasser M., Young W.F. The management of primary aldosteronism: case detection, diagnosis and treatment: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2016;101:1889–1916. doi: 10.1210/jc.2015-4061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schirpenbach C., Seiler L., Maser-Gluth C., Beuschlein F., Reincke M., Bidlingmaier M. Automated chemiluminescence-immunoassay for aldosterone during dynamic testing: comparison to radioimmunoassays with and without extraction steps. Clin. Chem. 2006;52(9):1749–1755. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.068502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ray J.A., Kushnir M.M., Palmer J., Sadjadi S., Rockwood A.L., Meikle A.W. Enhancement of specificity of aldosterone measurement in human serum and plasma using 2D-LC-MS/MS and comparison with commercial immunoassays. J. Chromatogr. B. 2014;970:102–107. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2014.08.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brown J.M., Auchus R.J., Honzel B., Luther J.M., Yozamp N., Vaidya A. Recalibrating interpretations of aldosterone assays across the physiologic range: immunoassay and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry measurement under multiple controlled conditions. J. Endocr. Soc. 2022;6:1–9. doi: 10.1210/jendso/bvac049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Constantinescu G., Bidlingmaier M., Gruber M., Peitzsch M., Poitz D.M., van Herwaarden A.E., Langton K., Kunath C., Reincke M., Deinum J., Lenders J.W.M., Hofmockel T., Bornstein S.R., Eisenhofer G. Mass spectrometry reveals misdiagnosis of primary aldosteronism with scheduling for adrenalectomy due to immunoassay interference. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2020;507:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rehan M., Raizman J.E., Cavalier E., Don-Wauchope A.C., Holmes D.T. Laboratory challenges in primary aldosteronism screening and diagnosis. Clin. Biochem. 2015;48:377–387. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jones J.C., Carter G.D., MacGregor G.A. Interference by polar metabolites in a direct radioimmunoassay for plasma aldosterone. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 1981;18:54–59. doi: 10.1177/000456328101800111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.French D. Development and validation of a serum total testosterone liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) assay calibrated to NIST SRM 971. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2013;415:109–117. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.CLSI. Mass spectrometry for androgen and estrogen measurements in serum. 1st edition. CLSI guideline C57. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2015.

- 44.Fiet J., Le Bouc Y., Guéchot J., Hélin N., Maubert M.A., Farabos D., Lamazière A. A liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry profile of 16 serum steroids, including 21-deoxycortisol and 21-deoxycortisone, for management of congenital adrenal hyperplasia. J. Endocr. Soc. 2017;1(3):186–201. doi: 10.1210/js.2016-1048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schiffer L., Shaheen F., Gilligan L.C., Storbeck K.H., Hawley J.M., Keevil B.G., Arlt W., Taylor A.E. Multi-steroid profiling by UHPLC-MS/MS with post-column infusion of ammonium fluoride. J. Chromatogr. B. 2022;1209 doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2022.123413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.A. Dasgupta, A. Wahed, Chapter 2: Immunoassay design and issues of interferences, in: A. Dasgupta, A. Wahed (Eds.), Clinical Chemistry, Immunology and Laboratory Quality Control, second ed., Academic Press, Elsevier Science Ltd, San Diego, 1, pp. 25–45.

- 47.Cheng I., Norian J.M., Jacobson J.D. Falsely elevated testosterone due to heterophile antibodies. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;120(2 Pt 2):455–458. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318253d211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Maharjan A.S., Wyness S.P., Ray J.A., Willcox T.L., Seiter J.D., Genzen J.R. Detection and characterization of estradiol (E2) and unconjugated estriol (uE3) immunoassay interference due to anti-bovine alkaline phosphatase (ALP) antibodies. Practical Laboratory Medicine. 2019;17:e00131. doi: 10.1016/j.plabm.2019.e00131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang J., Xu L., Qiao L. Falsely elevated serum estradiol in woman of reproductive age led to unnecessary intervention and delayed fertility opportunity: a case report and literature review. BMC Women’s Health. 2022;22:232. doi: 10.1186/s12905-022-01828-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li D., Radulescu A., Shrestha R.T., Root M., Karger A.B., Killeen A.A., Hodges J.S., Fan S.-L., Ferguson A., Garg U., Sokoll L.J., Burmeister L.A. Association of biotin ingestion with performance of hormone and non-hormone assays in healthy adults. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2017;318(12):1150–1160. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.13705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li D., Ferguson A., Cervinski M.A., Lynch K.L., Kyle P.B. AACC guidance document on biotin interference in laboratory tests. J. Appl. Lab. Med. 2020;05(03):575–587. doi: 10.1093/jalm/jfz010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Espiritu A.I., Remalante-Rayco P.P.M. High dose biotin for multiple sclerosis: A systematic review and meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. Mult. Scler. Relat. Disord. 2021;55 doi: 10.1016/j.msard.2021.103159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Katzman B.M., Lueke A.J., Donato L.J., Jaffe A.S., Baumann N.A. Prevalence of biotin supplement usage in outpatients and plasma biotin concentrations in patients presenting to the emergency department. Clin. Biochem. 2018;60:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2018.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wijeratne N.G., Doery J.C., Lu Z.X. Positive and negative interference in immunoassays following biotin ingestion: a pharmacokinetic study. Pathology. 2012;44(7):674–675. doi: 10.1097/PAT.0b013e32835a3c17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Knudsen C.S., Adelborg K., Søndergaard E., Parkner T. Biotin interference in routine IDS-iSYS immunoassays for aldosterone, renin, insulin-like growth factor 1, growth hormone and bone alkaline phosphatase. Scandinav. J. Clin. Investig. 2022;82(1):6–11. doi: 10.1080/00365513.2021.2003854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]