Abstract

Over the last 25 years, community-based participatory research (CBPR) has emerged as an innovative methodological approach to break down the barriers toward health equity in biopsychosocial research. Although there are several methods one can use to conduct CBPR research, one widely used established tool that has shown to be effective for engaging community meaningfully in research is community advisory boards (CABs). CABs are formalized collaborative bodies consisting of community and research stakeholders and have been integral in engaging underserved groups experiencing HIV-related health inequities at the early stages of the AIDS crisis. Even though evidence suggests that CABs are an effective tool for conducting high-quality, rigorous, and community-centered HIV-related research, there are minimal guidelines summarizing the steps needed for developing and maintaining a CAB. Therefore, to fill this gap in the literature, this article offers a practical guide to help researchers with minimal experience, particularly graduate students and early-stage investigators, feel more comfortable with establishing a CAB for equity-focused HIV-related research. This article synthesizes already established guidelines and frameworks for CAB development while specifically outlining unique steps related to the three main stages of CAB formation – establishment, implementation, and sustainment. Throughout this article, the authors offer tension points, generated from the literature and with consultation from a CAB working alongside the authors, that researchers and community partners may need to navigate during each of these three stages. In addition, best practices from the literature are identified for each step in the guidelines so that readers can see firsthand how research groups have carried out these steps in their own practice.

Keywords: community based participatory research, community advisory boards, HIV prevention, health equity

Introduction

According to both the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and World Health Organization, health equity ‘is achieved when every person has the opportunity to attain [their] full health potential’ regardless of ‘social position or other socially determined circumstances’.1,2 Operating within these definitions, health equity exists as an ideal goal that society should continuously strive for but has not yet reached.3 Numerous challenges to achieving health equity exist, including acknowledging power differentials between researchers and minoritized communities and developing accessible resources for underserved groups. Thus, it is important for researchers and practitioners to employ strategies to overcome these challenges and build a more health equitable society. One such strategy is community-based participatory research (CBPR).

CBPR has emerged over the last 25 years as an innovative methodological approach which recognizes the need for active cooperation between researchers and the community to drive research questions and produce pragmatic outcomes relevant to the needs of the community.4 A collaborative approach that equitably involves all partners in the research process, CBPR represents a ‘democratization’ of the research process by recognizing the unique strengths that each partner brings.5 This approach deviates from hierarchical methods of scientific inquiry in which researchers often operate from positions of omnipotent power, isolated from the ‘subjects’ of a research hypothesis, which may increase the risk of research-related harm.6 In contrast, CBPR actively centers the needs of the community and elevates the researcher–participant relationship to that of research–collaborator, further informing the iterative research process.

At its core, CBPR focuses on utilizing community engagement to identify actionable outcomes that are important to the partnering communities. CBPR projects often aim to combine knowledge and action for social change to improve community health and eliminate health disparities more broadly among marginalized groups. To do this effectively, components of CBPR include recognizing the value and strengths of communities and community members, ensuring that community stakeholders are involved in all aspects of research from hypothesis to dissemination, working toward mutually beneficial outcomes, and addressing issues from a multidimensional (e.g. looking at community, culture, and systems rather than just the individual) framework.4,7 Building off these integral components, the recently updated CBPR conceptual logic model further outlines that the success of a CBPR relationship hinges on four constructs: trust development, capacity building, mutual learning, and power dynamics.8

CBPR has been used as a tool for achieving health equity within HIV research and practice since the early 1990s and has been particularly relevant in addressing persistent HIV disparities. Even with significant advancements in HIV prevention and treatment over the past two decades, HIV still disproportionately affects certain racial, ethnic, and sexual populations. In 2019, despite only making up 13% of the US population, 40% of new HIV diagnoses were among Black individuals.9,10 Similarly, people who identify as Latino experienced 24% of new HIV diagnoses in 2019, a significantly larger share than their overall US population make up of 18.5%.9,10 Moreover, sexual minority (e.g. gay, bisexual, a man who has sex with men) Black and Latino men as well as trans women of all races face the greatest burden of HIV incidence compared with all others groups.9

In 2019, Fauci et al.11 announced the ‘Ending the HIV Epidemic’ (EHE) plan for the United States, which seeks to bring evidence-based HIV interventions equitably to scale. The EHE plan recognizes that a vital ‘component for the success of the initiative are active partnerships with city, county, and state public health departments, local and regional clinics and health care facilities, clinicians, providers of medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder, and community- and faith-based organizations’, highlighting the relevance of CBPR to achieving these EHE goals.11 First, CBPR aligns with the goals of patient-centered research,7 which may reduce distrust of medical systems and providers and improve intervention effects and recruitment of Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) in clinical trials12 including those who are gender diverse. Second, CBPR can serve as an effective tool for recruiting marginalized populations for biobehavioral health research through their active involvement in community work,13 and has been shown to improve health outcomes across varying conditions.14 Although there are several methods one can use to conduct CBPR research, one established tool that is widely used and shown to be effective for engaging community meaningfully in research is community advisory boards (CABs).15–17

CABs are formalized collaborative bodies consisting of community and research stakeholders15,18 that primarily serve as a method for equitably engaging community members within the broader framework of CBPR. CABs can be an effective tool15 for building a partnership between researchers and the larger community and overcoming a lack of trust due to historical exploitation of community members. CABs can also help with some of the methodological challenges of CBPR such as ensuring communities are aware of the research being conducted, gathering and interpreting data, as well as disseminating results in a manner that centers the needs of the community rather than those of the academics.

In the context of HIV prevention and treatment, the use of CABs has been integral in engaging underserved groups experiencing HIV-related health inequities. In the early stages of the HIV epidemic, a significant push to elevate the voices of people living with HIV to help inform research questions and clinical trials was championed by some healthcare providers, activists, and people living with HIV alike.16 Supporters of this initiative believed that providing people living with HIV with a more active role in HIV-related health research would not only allow for greater community representation in decisions regarding clinical trials that were being conducted primarily by ‘outsider’ doctors but also center the needs of people living with HIV in all aspects of research.16 In the 1990s, this advocacy resulted in changes at the federal funding level, such that the National Institute of Allergies and Infectious Disease (NIAID) required all grantees conducting HIV-related clinical research to establish and maintain CABs as a requirement for funding. Since then, CBPR has become a more prominent and effective approach to conducting various forms of HIV-related research.19,20

Although there is ample evidence suggesting that CABs are an effective tool for conducting high-quality, rigorous, and community-centered HIV-related research (see Newman et al.15 and Morin et al.21), there are few guidelines outlining the steps needed for establishing and maintaining a CAB. Therefore, to facilitate the process, this article offers a practical guide to CAB formation, implementation, and sustainment to help researchers with minimal experience, particularly early-stage investigators (ESIs) and graduate students, feel more comfortable developing a CAB for equity-focused research. The steps we outline synthesize existing frameworks and guidelines while taking them a step further by reviewing practical examples from the literature and discussing potential ‘tension points’ that researchers and community partners may need to navigate that correspond with each stage highlighted in the guidelines.

Overview of CAB formation guidelines

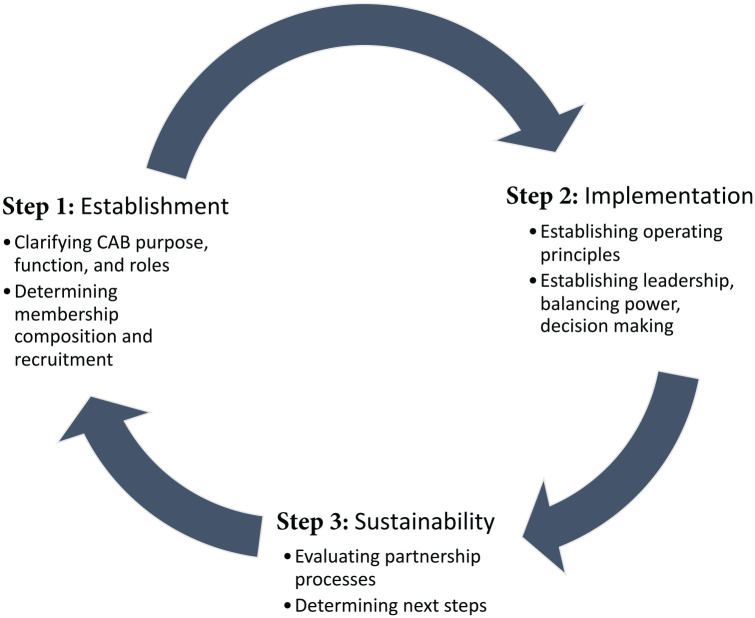

Establishing, implementing, and evaluating successful CABs require a set of processes that are contingent upon the goals of the researchers and community partners in the CAB. Engaging in CBPR necessitates a sense of flexibility on the part of all team members due to the dynamism of communities and their evolving needs; therefore, it is worthwhile for researchers to have a tentative outline from the start that addresses various aspects related to CAB establishment, implementation, and sustainment. Building from Newman et al.’s15 manuscript synthesizing strategies for forming, operating, and maintaining CABs, the following sections provide specific guidelines (see Figure 1 for overview) and potential tension points for each stage of CAB development that ESIs and graduate students can utilize as they begin the process of organizing HIV and equity-focused CABs. These tension points were generated based on reviewing the literature and from direct feedback from a CAB that the first and senior authors are working with, focused on Latino sexual minority men’s health. It is important to note that there are a handful of instances throughout this article in which the authors offer insights from their own experiences partnering with or being members of a CAB focused on Latino sexual minority men’s health. We recognize that the experiences gleaned from our own experiences and referenced throughout this article may not be generalizable to other CABs, and therefore, should be considered anecdotal information only. In addition, we outline ‘success stories’ from the literature in which research groups successfully utilized components from every stage of this guide as they established, implemented, and sustained their own CABs (see Table 1). Finally, although there are various types of CABs (e.g. entire hospital systems, new business ventures), this article will focus on CABs within research contexts.

Figure 1.

Stages of CAB formation and maintenance.

Table 1.

‘Success stories’ from the literature for components in the CAB establishment, implementation, and sustainability stages.

| Topic stage | Research team | CAB focus | Best practice(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Establishment: Practical examples of CAB Responsibilities | Oswaldo Cruz Foundation and General Hospital of Nova Iguaçu Brazil.22 | Low-resourced communities in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. | CAB responsibilities included (a) spearheading community engagement activities related to research, (b) assisting with study recruitment, (c) organizing frequent lectures known as palestras on HIV-related education for the community, and (d) establishing partnerships with other community organizations. |

| Establishment: Practical examples of CAB Responsibilities | CHAMP.23 | Nine months of in-home mental health treatment for people with HIV and mental health issues. | Functions of the CAB included (a) adapting the evidence-based Illness Management and Recovery treatment model for people living with HIV and (b) advising on intervention implementation procedures. |

| Establishment: Practical examples on how CABs adopt a shared partnership approach | Michigan Center for Urban African American Aging Research.17 | Recruiting and retaining older Black patients. | CAB members’ feedback and perspectives were equal to those of the research team in decisions like (a) how community events were conducted (e.g. menu items, venue location) and (b) how to frame health information in a positive and empowering light. |

| Establishment: Practical examples on how CABs adopt a shared partnership approach | Project Eban.24 | Multisite intervention to reduce HIV transmission among serodiscordant heterosexual Black couples. | CAB shared partnership approaches included (a)shaping language used in the recruitment materials and assessments to be destigmatizing, (b) guiding researchers to integrate Black community values into the intervention, (c) critiquing the structure of the intervention, and (d) providing opportunities to help present the information and research findings in community settings. |

| Establishment: Broad community and population specific models | Shape Up: Barbers Building Better Brothers.25 | HIV prevention intervention that centered Black young adults. | This CAB utilized a population specific model so members were Black/African American barbers and barbershop owners, which represented both the population served and culturally relevant context of the intervention. |

| Establishment: Broad community and population specific models | The REACH 2010: Charleston and Georgetown Diabetes Coalition.26 | Diabetes-related disparities amongst Black identified individuals. | This CAB utilized a broad community model and was comprised of 28 partnering organizations with a range of members (e.g. individuals living with diabetes, academic organizations, and college sororities). |

| Establishment: General and targeted recruitment methods | Lima, Peru CAB.27 | The CAB was formed with the goal of studying the prevalence of HIV, HIV treatment interventions, and an array of topics related to HIV and sexual health. | The Lima CAB implemented a general approach and recruited PLWH, representatives from both nongovernmental organizations and governmental organizations, and members representing ‘at-risk’ populations including MSM and sex workers. |

| Establishment: General and targeted recruitment methods | Exercise Intervention CAB.28 | Improving exercise habits through engaging romantic partners in the process amongst Black couples. | The Exercise Intervention CAB illustrates an example of targeted recruitment. The researchers compiled a list of relevant organizations and reached out to specific individuals who they identified as having both a vested stake in the community and research interests. |

| Implementation: Developing operating principles | Menominee, Lac du Flambeu, and Bad River CABs.29 | Diabetes-related disparities amongst American Indian communities. | Operating procedures for the CAB included (a) having the facilitator develop the meeting agendas and lead the beginning of each meeting, (b) opening the meeting to any potentially interested individuals, (c) not paying for travel expenses/participation in the CAB, (d) having a flexible schedule, and (e) guidelines on orienting new members. |

| Implementation: Developing operating principles | ‘Imi Hale.30 | Provide guidance on building Native Hawaiian capacity in cancer research and programming. | Three distinct yet interconnected bodies were at the crux of operating principles: (a) community council advised specifically on issues related to cultural competency, (b) scientific council advised on the scientific merit of research projects, and (c) steering committee established policy and approved research projects for funding. |

| Implementation: Establishing leadership, balancing power, and decision-making | The HIV Cost Study.31 | Intervention focused on integrated treatment for substance abuse, mental health, and HIV/AIDS. | Each site chose a consumer rep who developed a consumer advisory board at their site, relayed feedback from the local CAB to the consumer liaison who worked across all sites, who then relayed feedback to Steering Committee. |

| Implementation: Establishing leadership, balancing power, and decision-making | CHAMP Family Intervention.32 | Adapting adolescent HIV/AIDS intervention for South Africa and Trinidad and Tobago. | US-based research teams concede power inherent in their lead role by articulating the following issues: (a) respecting the local partners’ rights and responsibilities to question aspects of their actions, (b) being explicit about institutional constraints, and (c) yielding ground in areas not constrained by external guidelines and expectations. |

| Sustainability: Evaluating CAB partnership processes | Mayo Clinic Center for Clinical and Translational Science.33 | Quality control for research conducted at Mayo Clinic centers in Jacksonville, FL, Rochester, MN, and Scottsdale/Phoenix, AZ. | CAB members provide feedback on CAB progress and each meeting and assisted in developing yearly refresher trainings related to CAB membership and duties alongside the organizing research team. |

| Sustainability: Evaluating CAB partnership processes | Center for Equal Health (CEH) CAB.34 | Cancer disparities across disproportionately impacted communities. | Formal and semi-structured interviews were used to assess CAB membership processes with an emphasis on soliciting feedback, crowdsource potential solutions, and effectively address any issues that were brought up. |

| Sustainability: Incentivizing participation and retention | Project EAST.35 | Understand attitudes toward HIV research and co-develop an intervention for people in a rural setting. | Members were provided a stipend, given a meal at each meeting, compensated for the mileage spent in order to attend the CAB meetings in-person, invited to collaborate on manuscripts as co-authors, and supported in the development of academic writing skills. |

| Sustainability: Incentivizing participation and retention | Massachusetts Department of Public Health CAB.36 | Adolescent sexual and reproductive health inequities | CAB members were compensated financially via US$25 per meeting distributed through Tango, a gift card services program. |

CAB: community advisory board; MSM, men who have sex with men; PLWH, people living with HIV.

Establishment

The establishment stage of forming a CAB includes activities such as defining the role of the CAB, establishing the CAB’s mission and purpose, and identifying potential CAB members that ensure full representation from the community as much as possible.15 It is important for researchers to work with the CAB members on these establishment activities prior to engaging in the ‘work’ of the CAB to not only create more equity throughout this process, but also increase the likelihood for a more balanced power differential between CAB organizers (researchers) and members. This type of bidirectional communication prior to the work beginning serves to facilitate partnership and a shared vision of goals, tasks, and responsibilities for all involved.

Step 1: clarifying purpose, function, and roles

Overall, CABs should be an implicit part of any research program so that researchers maintain meaningful, power-balanced engagement with marginalized communities to ensure that the research remains grounded. Consistent with the larger mission of CBPR, the most common reason CABs are organized in research contexts is to provide a pathway through which community members can meaningfully engage in a wide range of research-related processes and to establish bidirectional communication, trust, and benefit between community members and researchers.15,37 CABs are essential to provide guidance regarding a specific aspect of a research project, a comprehensive research agenda, or the needs of a particular community more broadly. These responsibilities come in various forms including but not limited to: (a) generating important research questions relevant to the community, (b) refining an already drafted study protocol to enhance alignment with community needs, (c) brainstorming culturally relevant and effective participant recruitment techniques, (d) facilitating buy-in with community members who may be hesitant about a new intervention, treatment, or research project, (e) advising or partnering on the development of intervention or educational materials, (f) disseminating findings within their social networks and to the larger community, and (g) advocating for social change via policy legislation and lobbying.

Depending on the purpose of the CAB, members can take on varying roles and responsibilities; therefore, establishing – ideally in partnership with the CAB members themselves – members’ roles and expectations is the next step during the establishment stage. Similarly, this stage requires a sense of accountability on the part of all partners so that all members, no matter their background (i.e. academic researcher or community member), can hold each other to the expectations established by the group. Yuen et al.38 describe a continuum of roles that community partners can have on community-engaged research. They describe three models that are likely common in the context of CAB development: involve, shared leadership, and community-driven.

Even though both the ‘involve’ and ‘shared leadership’ models of CAB development are community driven, there are slight differences in the roles CAB members embody in these two models. In the ‘involve’ model of a CAB, members would provide guidance and suggestions on behalf of the community with the understanding that organizing research teams’ have the final word in accepting, tabling, or declining to integrate CAB members input.21,39 In this way, an ‘involve’ role does not influence the research hierarchy to the same extent as a ‘shared leadership’ or ‘community-driven’ CAB. Alternatively, CAB members in a ‘shared leadership’ role38 advocate for their communities by helping to resolve issues pertinent to the community in collaboration with the organizing research team with the understanding that decisions will be made as a unit.21 Within the context of HIV research, we advocate for researchers to ensure that CAB members have a ‘shared leadership’ role from the onset rather than solely an ‘involve’ role to increase transparency between groups and allow for the ideals of CBPR to be fully realized, if this is the goal.38,39

Determining a CAB’s mission can be a tension point because it sets the tone for the future of the partnership. Navigating this tension point requires researchers to first identify their CAB’s ‘why’ and then determine whether a broad community model or population-specific model best aligns with the goals of the research program at large.21 In a broad community model, CAB members range in background and experience so to represent a vast cross-sectional swath of the larger community of interest. In the context of HIV prevention and treatment studies, this may include key leaders across a variety of industries [e.g. government, nongovernmental organization (NGOs), religious organizations] as well as members of HIV-affected communities. CABs that reflect a broad community model require more investment and long-term resources and are often more oriented toward the future in establishing systems to help researchers respond to potential community-initiated research projects in the long-term.21,29

Alternatively, a population-specific model for CAB formation may be a more feasible model for researchers and teams who are focused on exploring the needs of a specific group or subpopulation. This model is predominantly used when a research team has a specific project or linked set of projects they are planning, thereby making it a popular choice for ESIs and graduate students, whose resources might also be limited to that specific project. Examples of a population-specific model of CABs in the context of HIV-related research include high incidence substance using populations in major metropolitan areas,40 people living with HIV in an international low-resource setting,22 or Latino sexual minority men in a US HIV epicenter (current CAB in partnership with first and senior authors). CABs operating within this model are often composed of members primarily from the subpopulation of interest and focused on strengthening existing protocols rather than anticipating future research projects.

Step 2: determining membership, composition, and recruitment strategies

Once the mission and purpose of the CAB is defined, research teams can begin to focus on identifying, engaging, and welcoming potential CAB members. As with research studies, research teams should be clear on who is ‘eligible’ to be a part of a particular CAB.41 It can be helpful to have discussions with all members of the research team (e.g., principal investigator, co-investigators, study staff members, study therapists, any existing community partners) to identify gaps that the unique perspectives/lived experiences of potential CAB members may fill. CABs that are composed of community members with tailored and complementary skillsets related to the research scope will be the most sustainable and successful.15 In some cases, researchers may already have established collaborations and partnerships with community-based organizations; these relationships can be a helpful place to start in terms of identifying potential CAB members as they are often well-connected to community members and could help to make trusted connections to build the CAB.17 Finally, the process of CAB formation should be iterative in that recruitment methods are continuously improved based on the needs of the research team at a given time.37 For example, as a CAB begins to meet and the research program advances, the CAB can collaboratively decide whether to expand membership by inviting other community members, agency leaders, or health providers to participate based on any evolving gaps in CAB needs.

Deciding whether to invite specific, known community members to join the CAB or recruit more broadly (e.g., posting advertisements in public settings) can be a tension point at this stage of CAB formation. Benefits of a more tailored recruitment strategy in which specific community members are approached from the onset include the potential for members to already have a shared mission with the organizing research team which may, in turn, allow the CAB to form more easily. On the contrary, advantages related to a more broad-based recruitment of CAB members who the research team is not already connected with include (a) meeting people who may offer unique perspectives/lived experiences that differ from existing CAB members, (b) engaging members who self-select in and therefore may be more motivated to join and stay meaningfully involved, and (c) promoting a more democratic process of CAB membership.

Whether CAB members are invited to participate via targeted or broad recruitment, it is important that all members go through the same starting process after determining that they are a fit for the CAB and that they would like to join. First, the organizing research team should meet with each potential CAB member to review expectations both parties possess regarding CAB engagement. This discussion could include an overview of the intended role of the CAB member (e.g., advisory versus partner), a delineation of specific responsibilities associated with membership, an established communication plan for contacting the CAB member and researchers, and a list of responsibilities of the researcher to the CAB members (e.g., compensation, processes for how community feedback will be considered). One strategy for formalizing the commitment between the researcher and community member could be to collaboratively develop and sign a letter of commitment signed by the lead researcher and CAB member. This type of formal agreement strengthens the importance of this partnership and reduces potential miscommunication moving forward. Furthermore, these agreements could be renegotiated so that any changes in duties, responsibilities, and expectations of both the CAB members and researchers can be reflected. Overall, the discussion between potential CAB members and the organizing research team should foster authenticity and openness. Researchers who are transparent in articulating their reasons for establishing the CAB at the onset help to create an environment of mutual understanding and egalitarianism that furthers the overall goals of the research program.

Implementation

An important element of starting up a CAB is developing a plan for managing logistics. Clarifying both operating procedures (i.e. what a CAB does) and operating principles (i.e. how it gets them done) is helpful for ensuring that the CAB runs smoothly and, in a way, consistent with the overall mission and values of the CAB. Both operating procedures and principles can be defined by the CAB themselves, with facilitation from the lead researcher.

Step 3: concretizing operating principles

Developing a set of guiding principles that complements a CAB’s operating procedures is another essential component of the CAB implementation process. As with all CBPR tools, CABs are inherently community oriented; therefore, integrating CAB members’ values and standards harnessed from their communities as a ‘moral code’ that will inform CAB procedures can help to bolster trust and affiliation between members and organizing researchers.15,39 Principles associated with mutual respect, inclusivity over division, letting members agree to disagree, speaking from the ‘I’ perspective, and active listening are all examples of core ethics that can not only guide internal CAB procedures but also serve as a template for evaluating research-related materials that honor and safeguard the values associated with the communities from which the CAB represents.41,42 Similar to the set of operating procedures, CAB members should have access to resources that outline CAB operating principles so that they can periodically be revisited and updated as evolving situations arise.

One tension point that can come up in this stage is determining whether operations should be more structured vs. free-form. In the authors’ own experience, we navigated whether to have a structured, goal-driven CAB versus a more unstructured CAB that focused on emergent issues. In our case, some CAB members preferred clear deliverables and timelines, whereas others preferred a more open approach, in which CAB meetings could be responsive to ongoing issues and not as goal driven. As a CAB, we decided to respect both the process of generating new ideas responsive to community needs as a CAB (resulting in new, CAB-initiated projects further described elsewhere) and soliciting feedback on ongoing projects that the research team had underway based on existing timelines (e.g. meaningfully integrating CAB members’ perspectives into ongoing projects). Regularly checking in with the CAB throughout its implementation about the balance between structured and unstructured/CAB-driven projects can help to ensure that all members’ (including the researchers) needs are met.

Step 4: establishing leadership, balancing power, and making decisions

One of the most critical components in fostering equity within the CAB implementation stage is determining guidelines around fair, bidirectional leadership and decision-making. Although establishing a balance of power is always challenging when working with groups, creating an equitable distribution of power within a CAB may be particularly complex due to the varying academic, cultural, and social backgrounds of CAB members and researchers.43 CAB members may come from communities that hold a significant amount of warranted medical mistrust due to ongoing and historical abuses of power and mistreatment within in medical/research settings.44 Therefore, developing a clear and equitable system of shared power among researchers and CAB members may help to alleviate some of that valid mistrust and ensure that the work of the CAB (and research team) is grounded in community needs and priorities. More broadly, a model of equitable leadership will aid in the overall success of the CAB by bolstering members’ desire to participate, satisfaction with their experience, and consensus-building in general decision-making.39,41

Determining how decisions will be made within the CAB can be a tension point within this stage of CAB establishment. It is important to be clear about whether research decisions will be made that are ‘informed’ by the CAB (i.e., the researchers consider CAB perspectives, but make ultimate decisions on projects) or if the CAB has the ability to fully decide an outcome (e.g. the CAB can decide not to pursue a particular grant, or to remove certain questions from a survey, which could potentially differ from the researchers’ perspective). It is also possible that there may be some projects that the CAB works on where the CAB makes final decisions (e.g., CAB-initiated projects) and others where the researcher may make final decisions (e.g., ongoing funded projects in which the researcher may have specific deliverables they must meet to comply with funding requirements). Being transparent about decision-making power and processes can not only increase meaningful engagement from CAB members but also strengthen the overall success and sustainability of the CAB. Another strategy that CABs might take is the ‘a select few’ approach in which one to two leaders among the CAB members are selected to represent the CAB interests. Although this approach may streamline the decision-making process, it can place pressure on the specific individuals making the decisions and generate some mistrust or frustration among CAB members who are not part of the group making final decisions – a challenge to navigate. Furthermore, taking a more democratic process to decision-making could facilitate a united CAB by acknowledging everyone’s opinion regarding CAB business and improve group solidarity.

Sustainability

The final stage of CAB maintenance reflects the processes related to evaluating the CAB’s impact and determining any adaptations needed to improve the overall functioning of the CAB. This stage is iterative in nature and is composed of two distinct steps that encompass underlying themes of reflection and flexibility. Being reflective and adaptable are particularly important in HIV prevention and treatment research due to the rapidly evolving nature of the field.

Step 5: assessing overall impact of the partnership

Multimethod approaches can be helpful for evaluating the impact of CABs. Employing a diverse set of measurement tools, both quantitative (e.g., surveys, activity logs) and qualitative (e.g., focus groups, meeting observations), can facilitate a more comprehensive assessment of CAB operations, functionality, and impact. A mixed-methods approach to CAB evaluation allows for CAB members and the organizing research team to both quantify impact, learn more about qualitative processes that could explain this impact, and in turn, identify target points for improvement. It is important to note that evaluation can be structured (e.g., interviews or mid-semester surveys) or more ongoing and informal (e.g., temperature checks at CAB meetings).

Process evaluations should examine several issues related to CAB functioning including but not limited to assessing group dynamics within the CAB, protocols related to shared leadership and decision-making, methods of communication between members and the organizing research team, and overall impact/outcomes of the CAB.8,45 Evaluating CAB functioning could focus on issues such as engaging and retaining CAB members, members’ perceptions of benefits and cons of CAB participation, and the degree to which current procedures are sustainable over time.29,46 Periodic assessment and subsequent improvements in these two domains could increase the probability of the CAB’s long-term sustainability.

A tension point that can arise in this phase is creating assessment procedures that balance thoroughness versus burdensomeness. Behavioral researchers may be inclined to collect as much data as possible to improve systems; however, data collection and analysis require energy and resources of both the researchers and CAB members. The needs of the CAB might dictate the extent to which to formally versus informally evaluate the CAB. For instance, if a new leadership structure has recently been introduced, it may be helpful to focus on evaluating how CAB members experience that new leadership structure, and then move on to evaluate other aspects of the CAB later in the process. Another related issue could be the extent to which the CAB uses meeting time to reflect on CAB processes and experiences, versus using the time to engage in more ‘action-oriented’ activities such as developing new research and providing feedback on existing projects. Paying close attention to CAB dynamics and needs can help to inform this balance. This allows for continuous reflection and improvement to the CAB operations while also reducing the risk of fatiguing members and researchers.

Step 6: determining next steps

As a final stage in this process, it is important to determine the next steps for the CAB, including developing a plan for ending a CAB (if project-focused and the project is ending) or longer-term maintenance (if the CAB is meant to be ongoing). Although ‘determining next steps’ is most closely associated with the CAB sustainability stage, it is useful to begin considering the longer-term plans for the CAB during the initiation stage of the CAB. Throughout the process of determining next steps, CAB members play an active role in deciding whether and how to maintain the CAB over time. Having a plan for maintaining a CAB over time is helpful for building meaningful community partnerships. As such, part of CAB maintenance planning might involve considering how to support and sustain the CAB in times of funding uncertainty, and under what circumstances it might be best to discontinue a CAB (e.g., if project goals have been met, the CAB does not see that ongoing membership is needed, or long-term sustainment is otherwise not possible). If the CAB decides to end, intentional decision-making can inform what ongoing communication between the organizing research team, CAB, and the larger community might entail, and how ongoing relationships could support future collaborations.17

A tension point that can arise in determining next steps is the balance between ongoing engagement and sustainability. Being a part of a CAB is a commitment that requires time, consistency, and in many cases, some degree of vulnerability in sharing one’s own experiences to inform research. It is therefore critical that the experience of being on a CAB also yields meaningful benefits to the members (and their own organizations and communities), which can also support the long-term sustainability of the CAB by way of members remaining actively engaged. If the CAB is not bidirectional in benefits (i.e., the research team benefits from the CAB, but the CAB does not experience benefits from being part of the CAB), it is likely that members will not wish to remain engaged long-term. One set of benefits to being a part of a CAB can be compensation. It is important for research teams to acknowledge the significant amount of time, energy, and resources CAB members offer in their participation in the CAB, and providing financial compensation is one way to make this acknowledgment. In situations in which financial incentives are not available (e.g., a graduate student or ESI without funding), it may be possible to think creatively with the CAB about whether it is possible to compensate for their time in a way that still feels fair and equitable, and if so, how. Other strategies that might be appropriate, but would require CAB feedback to confirm, include recognition of CAB members’ efforts via other inexpensive remuneration strategies (e.g., awards/honors bestowed by organizing research institution, ability to take free courses at the organizing research institution, public recognition in local media, and events for CAB family members).24,47

In addition to tangible forms of compensation, another way of promoting bidirectional benefits within a CAB is providing opportunities for personal and professional development. CAB members are uniquely situated to enact real change within their community. As such, given the resources researchers may have available to them, the research team can support CAB members via professional development, resources, and training to help CAB members achieve their own personal and professional goals. For example, research teams could offer trainings on the principles of CBPR, general research methods, health-specific research topics, or general leadership skills coaching to bolster CAB members’ self-efficacy regarding behavioral health research and policy work. Providing opportunities for CAB members to get involved with manuscript publications, presenting at conferences, hosting workshops within their communities, or receiving special certification/accreditation in community-based research honored by the organizing research institution are other strategies for engaging CAB members over time.

Future directions of CABs in HIV prevention and treatment research

Building on the successful CAB partnerships from the past two decades, innovative strategies for community engagement are emerging in the field of HIV prevention and treatment research. For example, community partnerships are increasingly recognized as key to achieving HIV prevention and treatment research endeavors. Beginning in 2019, the National Institutes of Health have been funding EHE administrative supplements that require investigators to fully partner with communities and implementers to ensure maximum impact.11 Some EHE supplements have even required grants to be submitted with both a university and community principal investigator.

Adopting this model would transform CABs from advisors into full-fledged partners on research and may encourage researchers to begin developing partnerships earlier in the research process, rather than as an ‘add on’ after a project is already funded. This model would also help facilitate a closer connection between researchers and community members by engaging them at every step of the research process, from determining what grant mechanisms to apply for, to developing the specific aims and procedures for conducting studies, and even up and through manuscript publication and dissemination of findings. Inviting CAB members to serve as co-authors on each community-engaged publication would increase transparency within the research process and demonstrate an endorsement by the community in signing off on the research findings. In addition, our CAB recommended that in the future, CABs should hold hybrid community forums (in person and virtual) on a regular basis to continue facilitating openness between the organizing research team, CAB, and larger community. The main purpose of these forums would be bidirectional in that community members can be kept abreast of study updates, preliminary findings, and study conclusions while providing iterative feedback during all stages of the project. CAB members also become integral when the results of research program become published, and advocacy –for further research or to change policies and existing infrastructure – becomes the priority.

As we have described throughout this article, CABs offer researchers a unique opportunity to work with community toward health equity in both social and medical science research. At their core, CABs require continuous input from community members so that research is permanently influenced by the needs, perspectives, and lived experiences of those living within the population of interest. When implemented effectively, CABs can reduce power imbalances between researchers and communities, amplify and center the perspectives and experiences of marginalized groups, and help to shift the discourse closer to equitable health outcomes. It is important for future research to evaluate in greater depth what components make a CAB partnership successful so that more resources related to CAB establishment, implementation, and sustainability can be utilized in CBPR contexts so to conduct the most impactful and rigorous research possible. Hopefully, as the roles of CABs and community members continue to grow in HIV prevention and treatment research, the field can further concretize its commitment to addressing barriers to health equity and lead the charge in create a more just scientific process for all.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Daniel Hernandez Altamirano, Naomie Payen, Eddie Orozco, and Hans Schenk for their assistance with this project.

Footnotes

ORCID iDs: Elliott R. Weinstein  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5085-7470

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5085-7470

Audrey Harkness  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2290-9904

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2290-9904

Contributor Information

Elliott R. Weinstein, University of Miami, Miami, FL 33146, USA.

Christian M. Herrera, Texas A&M University System, College Station, TX, USA

Lorenzo Pla Serrano, Florida International University, Miami, FL, USA.

Edward Martí Kring, Georgetown University, Washington, DC, USA.

Audrey Harkness, University of Miami, Miami, FL, USA.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Not applicable.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Author contributions: Elliott R. Weinstein: Conceptualization; Data curation; Methodology; Supervision; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Christian M. Herrera: Data curation; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Lorenzo Pla Serrano: Conceptualization; Writing – review & editing.

Edward Martí Kring: Conceptualization; Writing – review & editing.

Audrey Harkness: Conceptualization; Funding acquisition; Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Some author time was funded via K23MD015690 (Harkness). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Availability of data and materials: Not applicable.

Code availability: All codes for data cleaning and analysis are available upon request from E.R.W.

References

- 1. CDC. Health equity, https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/healthequity/index.htm (2022, accessed 6 August 2022).

- 2. Health equity – global, https://www.who.int/health-topics/health-equity (accessed 6 August 2022).

- 3. Ibrahim SA, Thomas SB, Fine MJ. Achieving health equity: an incremental journey. Am J Pub Health 2003; 93: 1619–1621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, et al. Community-based participatory research: policy recommendations for promoting a partnership approach in health research. Educ Health 2001; 14: 182–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Adelman C. Kurt Lewin and the origins of action research. Educ Action Res 1993; 1: 7–24. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Alsan M, Wanamaker M. Tuskegee and the health of black men. Q J Econ 2018; 133: 407–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Collins SE, Clifasefi SL, Stanton J, et al. Community-based participatory research (CBPR): towards equitable involvement of community in psychology research. Am Psychol 2018; 73: 884–898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Belone L, Lucero JE, Duran B, et al. Community-based participatory research conceptual model: community partner consultation and face validity. Qual Health Res 2016; 26: 117–135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV in the United States and dependent areas, https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/ataglance.html (2020, accessed 24 August 2020).

- 10. US Census Bureau. 2019 national and state population estimates, https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-kits/2019/national-state-estimates.html (2019, accessed 8 October 2020).

- 11. Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, et al. Ending the HIV epidemic: a plan for the United States. JAMA 2019; 321: 844–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. De Las Nueces D, Hacker K, DiGirolamo A, et al. A systematic review of community-based participatory research to enhance clinical trials in racial and ethnic minority groups. Health Serv Res 2012; 47: 1363–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wallerstein NB, Duran B. Using community-based participatory research to address health disparities. Health Promot Pract 2016; 7: 312–323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Salimi Y, Shahandeh K, Malekafzali H, et al. Is community-based participatory research (CBPR) useful? a systematic review on papers in a decade. Int J Prev Med 2012; 3: 386–393. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Newman SD, Andrews JO, Magwood GS, et al. Community advisory boards in community-based participatory research: a synthesis of best processes. Prev Chronic Dis 2011; 8: A70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cox LE, Rouff JR, Svendsen KH, et al. Community advisory boards: their role in AIDS clinical trials. Health Soc Work 1998; 23: 290–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mitchell J, Perry T, Rorai V, et al. Building and sustaining a community advisory board of African American older adults as the foundation for volunteer research recruitment and retention in health sciences. Ethn Dis 2020; 30(Suppl. 2): 755–764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Strauss RP, Sengupta S, Quinn SC, et al. The role of community advisory boards: involving communities in the informed consent process. Am J Public Health 2001; 91: 1938–1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Berkley-Patton J, Bowe-Thompson C, Bradley-Ewing A, et al. Taking it to the pews: a CBPR-guided HIV awareness and screening project with black churches. AIDS Educ Prev 2010; 22: 218–237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rhodes SD, Malow RM, Jolly C. Community-based participatory research (CBPR): a new and not-so-new approach to HIV/AIDS prevention, care, and treatment. AIDS Educ Prev 2010; 22: 173–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Morin SF, Maiorana A, Koester KA, et al. Community consultation in HIV prevention research: a study of community advisory boards at 6 research sites. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2003; 33: 513–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Milnor JR, Santana CS, Martos AJ, et al. Utilizing an HIV community advisory board as an agent of community action and health promotion in a low-resource setting: a case-study from Nova Iguaçu, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Glob Health Promot 2020; 27: 56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Reif SS, Pence BW, LeGrand S, et al. In-home mental health treatment for individuals with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2012; 26: 655–661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mott L, Crawford E. The role of community advisory boards in project Eban. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008; 49(Suppl. 1): S68–S74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB, Lanier Y, et al. Development of a barbershop-based HIV/STI risk reduction intervention for young heterosexual African American men. Health Promot Pract 2017; 18: 110–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Jenkins C, McNary S, Carlson BA, et al. Reducing disparities for African Americans with diabetes: progress made by the REACH 2010 Charleston and Georgetown diabetes coalition. Public Health Rep 2004; 119: 322–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Morin SF, Shade SB, Steward WT, et al. A behavioral intervention reduces HIV transmission risk by promoting sustained serosorting practices among HIV-infected men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008; 49: 544–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hornbuckle LM, Rauer A. Engaging a community advisory board to inform an exercise intervention in older African-American couples. J Prim Prev 2020; 41: 261–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Adams AK, Scott JR, Prince R, et al. Using community advisory boards to reduce environmental barriers to health in American Indian communities, Wisconsin, 2007-2012. Prev Chronic Dis 2014; 11: E160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Braun KL, Tsark JU, Santos L, et al. Building Native Hawaiian capacity in cancer research and programming. Cancer 2006; 107(Suppl. 8): 2082–2090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Klinkenberg WD and, Sacks S; HIV/AIDS Treatment Adherence, Health Outcomes and Cost Study Group. Mental disorders and drug abuse in persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care 2004; 16(Suppl. 1): S22–S42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Baptiste DR, Bhana A, Petersen I, et al. Community collaborative youth-focused HIV/AIDS prevention in South Africa and Trinidad: preliminary findings. J Pediatr Psychol 2006; 31: 905–916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Brockman TA, Balls-Berry JE, West IW, et al. Researchers’ experiences working with community advisory boards: how community member feedback impacted the research. J Clin Transl Sci 2021; 5: e117, https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-clinical-and-translational-science/article/researchers-experiences-working-with-community-advisory-boards-how-community-member-feedback-impacted-the-research/7288CF029EB17244F2D90CBF691DB82F# [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Walsh M, Rivers D, Pinzon M, et al. Assessment of the perceived role and function of a community advisory board in a NIH center of excellence: lessons learned. J Health Disparities Res Pract 2015; 8: 5, https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/jhdrp/vol8/iss3/5 [Google Scholar]

- 35. Isler MR, Miles MS, Banks B, et al. Across the miles: process and impacts of collaboration with a rural community advisory board in HIV research. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2015; 9: 41–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Valdez ES, Gubrium A. Shifting to virtual CBPR protocols in the time of corona virus/COVID-19. Int J Qual Methods 2020; 19: 1609406920977315. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Norris KC, Brusuelas R, Jones L, et al. Partnering with community-based organizations: an academic institution’s evolving perspective. Ethn Dis 2007; 17(Suppl. 1): S27–S32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yuen T, Park AN, Seifer SD, et al. A systematic review of community engagement in the US environmental protection agency’s extramural research solicitations: implications for research funders. Am J Public Health 2015; 105: e44–e52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schlechter CR, Del Fiol G, Lam CY, et al. Application of community – engaged dissemination and implementation science to improve health equity. Prev Med Rep 2021; 24: 101620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Switzer S, Chan Carusone S, Guta A, et al. A seat at the table: designing an activity-based community advisory committee with people living with HIV who use drugs. Qual Health Res 2019; 29: 1029–1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Butterfoss FD. Coalitions and partnerships in community health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Israel BA, Lichtenstein R, Lantz P, et al. The Detroit Community-Academic Urban Research Center: development, implementation, and evaluation. J Public Health Manag Pract 2001; 7: 1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Becker AB, Israel BA, Gustat J, et al. Strategies and techniques for effective group process in community-based participatory research partnerships. In: Israel BA, Eng E, Schulz AJ, et al. (eds) Methods in community-based participatory research for health. 2nd ed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, 2012, pp. 69–96. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Suite DH, La Bril R, Primm A, et al. Beyond misdiagnosis, misunderstanding and mistrust: relevance of the historical perspective in the medical and mental health treatment of people of color. J Natl Med Assoc 2007; 99: 879–885. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Edgren KK, Parker EA, Israel BA, et al. Community involvement in the conduct of a health education intervention and research project: community action against asthma. Health Promot Pract 2005; 6: 263–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Feinberg ME, Gomez BJ, Puddy RW, et al. Evaluation and community prevention coalitions: validation of an integrated web-based/technical assistance consultant model. Health Educ Behav 2008; 35: 9–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Halladay JR, Donahue KE, Sleath B, et al. Community advisory boards guiding engaged research efforts within a clinical translational sciences award: key contextual factors explored. Prog Community Health Partnersh 2017; 11: 367–377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]