Abstract

Background

Magnesium is an antagonist of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor. This study aimed to investigate the anti-edematous effect of magnesium sulfate (MS) in different protocols of use and the possible mechanism of its action.

Methods

In a rat model of carrageenan-induced paw inflammation, the anti-edematous activity of MS was assessed with a plethysmometer. The effects of the nonselective inhibitor (L-NAME), selective inhibitor of neuronal (L-NPA) and inducible (SMT) nitric oxide synthase on the effects of MS were evaluated.

Results

MS administered systemically before or after inflammation reduced edema by 30% (5 mg/kg, P < .05) and 55% (30 mg/kg, P < .05). MS administered locally (.5 mg/paw, P < .05) significantly prevented the development of inflammatory edema by 60%. L-NAME, intraperitoneally administered before MS, potentiated (5 mg/kg, P < .05) or reduced (3 mg/kg, P < .05), while in the highest tested dose L-NPA (2 mg/kg, P < .01) and SMT (.015 mg/kg, P < .01) reduced the anti-edematous effect of MS.

Conclusions

Magnesium is a more effective anti-edematous drug in therapy than for preventing inflammatory edema. The effect of MS is achieved after systemic and local peripheral administration and when MS is administered as a single drug in a single dose. This effect is mediated at least in part via the production of nitric oxide.

Keywords: magnesium, anti-inflammatory, anti-edematous, preemptive therapy, emptive therapy, NOS inhibitors

Introduction

Inflammation underlies many diseases and conditions, such as tissue injury and trauma, rheumatoid arthritis, inflammatory bowel syndrome, asthma, and atherosclerosis.1 Inflammatory edema is characterized by mediator-induced high vascular permeability and leukocyte infiltration into tissues. Standard anti-inflammatory therapy by corticosteroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and biological therapy are limited by serious adverse effects. Therefore, there is a constant search for new or adjuvant drugs to improve the efficacy and safety of the drugs used in treating inflammatory conditions.2

Magnesium is an interesting target for research since it is well known that a deficit of magnesium causes and worsens inflammation3 and new research has shown that magnesium as a single drug and in a single dose has an analgesic effect in somatic and visceral inflammatory pain.4-7 Recently published results show that magnesium sulfate reduced vasogenic edema formation in a rat model of acute ischemic stroke, partly via antioxidant mechanisms.8 In patients with diabetic retinopathy a higher physiological range of magnesium in the serum was associated with a lower risk of diabetic macular edema.9 In rats, the use of bittern water, which enables the effective intake of magnesium ion (Mg2+), prevented the development of paw edema in arthritis.10 Also, magnesium is a widely used dietary supplement in the general population. More detailed studies on magnesium are needed to determine its anti-inflammatory effect and mechanisms of action. This mineral is an important regulator of transmembrane ion fluxes (as it acts on channels, pumps and carriers), a regulator of neurotransmitter release (acetylcholine, norepinephrine), and it serves as a cofactor for enzymes involved in many metabolic processes (protein and nucleic acid synthesis, glycolysis, Krebs cycle, β-oxidation, etc.).11,12 A recently published meta-analysis of randomized control trials showed that magnesium supplementation lowered the parameters of inflammation, including C-reactive protein and interleukin 1 in human serum.13 Magnesium upregulates the activities of the antioxidant enzymes superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase, and increases antioxidant protection of tissue.8 It is well known that magnesium acts as an N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist, blocking the ion channel associated with the receptor and that glutamatergic and nitrergic signaling pathways separately contribute to its analgesic effect in somatic inflammatory pain.4,6 Activation of NMDA receptors by glutamate results in an increase in intracellular calcium, which leads to nitric oxide (NO) production.14 NO is a well-known vasodilator molecule.15 Our recently published results showed that the NMDA antagonist MK-801, through increased production of NO reduced inflammatory edema.16

In this study, we investigated the potential anti-edematous effect of magnesium sulfate in different protocols of use and whether the production of NO modulates the effect of magnesium sulfate in the carrageenan-induced somatic inflammatory model in rats as the most suitable in vivo inflammatory model in preclinical research. This model has a high predictive value for screening the drugs used in treating human inflammatory disease.17

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

Animal handling was carried out in accordance with the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) Guidelines for the Use of Animals in Research. The experiments were approved by the local Ethics Committee for Animal Research and Welfare of the Medical University (Approval No. 323-07-02286/2013-05, March 25, 2013) and the Ethics Council for the Protection of Experimental Animals of the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Water Management of the Republic of Serbia, which are in compliance with the National Institute of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Animals

The experiments were carried out on 204 adult male Wistar rats (230–280 g). Animals were maintained under standard laboratory conditions as follows: housed three per cage in a Plexiglass cage (42.5 × 27 × 19 cm), 22 ± 1°C, 60% relative humidity, 12 h light/dark cycle. Animals were fed with standard rat pellets (Veterinary Institute, Subotica, Serbia) and tap water ad libitum, except during the experiments. The animals in all groups had the same origin and were fed with standard pellets that contained the optimal amount of magnesium for rat nutrition (.5 g/kg body weight) (Subotica Veterinary Institute, Serbia). In the laboratory, the rats were routinely subjected to biochemical analyses, including the magnesium concentration in the serum, which was in the reference range from .8 to 1.5 mmol/L. Three days before the experiments, the animals were habituated to handling. Experiments were always performed at the same time to avoid diurnal variations in the behavioral tests. At the end of each experiment, rats were killed with a 200 mg/kg intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of sodium thiopental.

Drugs

Magnesium sulfate was purchased from S.A.L.F. Spa-Cenate Sotto, Bergamo, Italy. N-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester hydrochloride (L-NAME), L-arginine hydrochloride and λ-carrageenan were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA. N-ω-Propyl-L-arginine hydrochloride (L-NPA) and S-methylisothiourea (SMT) were purchased from Tocris Bioscience, Bristol, Great Britain.

Drug Administration

Magnesium sulfate, L-NAME, L-NPA, SMT, L-arginine, and λ-carrageenan were dissolved in .9% NaCl and injected subcutaneously (s.c.) (magnesium sulfate, L-arginine) in the back, or intraperitoneally (i.p.) (L-NAME, L-NPA, SMT) at a final volume of 2 mL/kg, and intraplantarly (i.pl.) (carrageenan, magnesium sulfate) at a final volume of .1 mL per paw.

In three separate groups of animals, the magnesium sulfate was evaluated after systemic and local peripheral administration in the following prophylactic and therapeutic protocols of use:

1. Systemic (s.c.) administration of magnesium sulfate (.5–30 mg/kg) 5 minutes before carrageenan to evaluate the systemic prophylactic (preventive) effect of magnesium on the development of edema.

2. Systemic (s.c.) administration of magnesium sulfate (5 and 30 mg/kg) 2 hours after carrageenan because the edema was maximally developed 2-3 hours after the injection, to evaluate the systemic therapeutic (curative) effect of magnesium on developed edema.

3. Local peripheral (i.pl.) co-administration of magnesium sulfate (.05–.5 mg/paw) with carrageenan to evaluate the local prophylactic (preventive) effect of magnesium on edema development. To exclude systemic effects, the highest dose of magnesium was administered to the contralateral paw.

For magnesium sulfate, the doses were selected to correspond to doses used for magnesium supplementation in humans,6 and the next steps were adjusted based to the results obtained from the previous experiment.4,6

The possible mechanism of action of prophylactic magnesium sulfate was investigated through the interaction between magnesium sulfate and NO precursor and/or inhibitors using the following protocols:

1. L-NAME (3 and 5 mg/kg), L-NPA (.5–2 mg/kg) or SMT (.005–.015 mg/kg) were administered i.p. 10 minutes before magnesium sulfate,

2. L-arginine (.4 mg/kg, s.c.) was administered simultaneously with magnesium sulfate to confirm the role of NO.

In Vivo Model of Somatic Inflammatory Edema and Calculation of Anti-Edematous Activity

Inflammation on the rat hind paw was induced with s.c. injection of carrageenan (.5% w/v, .1 mL/paw) into the plantar surface of the right hind paw. Measurement and calculation procedures were described in detail.16 Briefly, the changes in paw volume (ml) were detected using a plethysmometer (Model Almemo 2390-5, IITC Life Science, Woodland Hills, USA). The paw volume was measured before injection of carrageenan with/without the tested drugs and thereafter at each time point during the six-hour time interval to calculate the difference in paw volume (dv). Reduction of the difference in paw volume (dv) indicated anti-edematous activity (AE%) and was calculated for each rat in one group using the following formula:16

The time of the effect of the tested drugs and their combinations were constructed by plotting the average changes in paw volumes in rats as a function of time.

The percentage inhibition (%I) of the anti-edematous effect after pretreatment with NOS inhibitor was expressed as follows:4

Statistical Analysis

Results are presented as mean differences in volume (dv) (ml) ± standard error of the mean (SEM) obtained in six animals per group. Student’s t-test or analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s HSD post hoc test were used to verify the difference between the corresponding mean of the volume. A P < .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Model of Carrageenan-Induced Inflammatory Edema

Inflammation of the hind paw caused by carrageenan was accompanied by local erythema, pain, and edema. Paw edema developed after 1 hour, reached a maximum at 3.5 hours and declined after 6.5 hours. There were no significant differences in baseline paw volume between and within the tested groups (average: 2.1 ± .1 mL, not shown).

Prophylactic Effect of Systemic Magnesium Sulfate Administration on Inflammatory Edema

The s.c. administration of magnesium sulfate (.5, 5, 15, or 30 mg/kg) before carrageenan-induced inflammation produced a dose-independent reduction in paw swelling. A statistically significant (P < .05) effect of 29.1 ± 6.1% (dv = .6 ± .1 mL) was achieved only at a dose of 5 mg/kg at 4.5 hours after inflammation induction (Figure 1). There were no significant differences in baseline paw volume between the groups tested (not shown).

Figure 1.

The time-response curves represent the prophylactic effect of subcutaneous magnesium sulfate (MS) administered 5 minutes before the carrageenan (Carr)-induced hind paw inflammatory edema test. Each point is the mean ± SE of differences between paw volumes in ml (dv). Compared to .9% NaCl, MS applied on its own at a dose of 5 mg/kg significantly (*P < .05) reduced edema.

Therapeutic Effect of Systemic Magnesium Sulfate Administration on Inflammatory Edema

When carrageenan-induced inflammation was maximally developed, s.c. administration of magnesium sulfate produced a statistically significant reduction in paw edema only with the high dose of 30 mg/kg (Figure 2). The anti-edematous effects were 51.1 ± 4.7% (dv = .5 ± .0 mL), 47.3 ± 3.9% (dv = .5 ± .0 mL) and 37.3 ± 7.4% (dv = .6 ± .0 mL) at the 3.5-, 4.5-, and 5.5-hour time points, respectively. There were no significant differences in the baseline paw volume between the tested groups (not shown).

Figure 2.

The time-response curves represent the therapeutic effect of subcutaneous magnesium sulfate (MS) administered 2 hours after the carrageenan (Carr)-induced hind paw inflammatory edema test. Each point is the mean ± SE of differences between paw volumes in ml (dv). Compared to .9% NaCl, MS applied on its own at a dose of 30 mg/kg significantly (*P < .05, **P < .01) reduced edema. There was a significant difference (+P < .05, ++P < .01) in comparison with doses of MS of 5 and 30 mg/kg.

Local Peripheral Prophylactic Effect of Magnesium Sulfate on Inflammatory Edema

Magnesium sulfate at doses of .05, .1, and .5 mg/paw that were co-administered i.pl. with carrageenan produced a dose-dependent effect on the development of edema, with only the highest local dose of magnesium sulfate (.5 mg/paw) producing a statistically significant (P < .05) reduction in paw edema (Figure 3). The anti-edematous effect of magnesium sulfate (.5 mg/paw) started 3.5 hours after inflammation and reached maximum expression 6.5 hours after inflammation. The anti-edematous effects were 43.6 ± 4.7% (dv = .6 ± .1 mL), 50.7 ± 7.7% (dv = .5 ± .1 mL), 55.8 ± 4.9% (dv = .4 ± .0 mL), and 58.6 ± 4.3% (dv = .4 ± .0 mL) at the 3.5-, 4.5-, 5.5-, and 6.5-hour time points, respectively. The effect was of local character and when the highest locally applied dose of magnesium sulfate (.5 mg/paw) was injected into the contralateral paw, there was no statistically significant (P > .05) change in edema in the paw injected with carrageenan (not shown).

Figure 3.

Time-response curves for the local peripheral effect of magnesium sulfate (MS) in the carrageenan (Carr)-induced hind paw inflammatory edema test. MS was co-administered with Carr. Each point is the mean ± SE of differences between paw volumes in ml (dv). Compared to .9% NaCl, MS applied on its own at a dose of .5 mg/paw significantly (*P < .05, **P < .01) reduced edema. There was a significant difference (+P < .05, ++P < .01) in comparison with the curve for the dose of MS .5 of mg/paw.

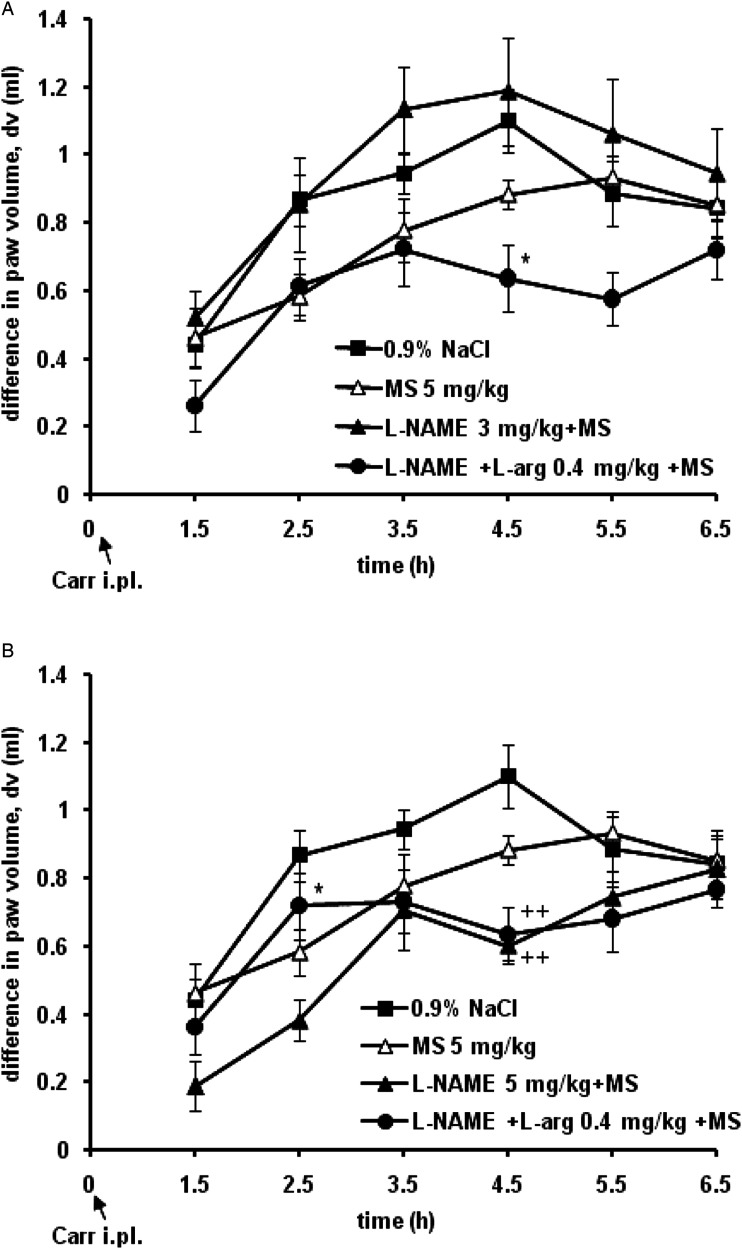

The Influence of Precursor and Nonselective Inhibitor of NOS on the Anti-edematous Effect of Magnesium Sulfate

L-NAME, a nonselective inhibitor of NOS, at a dose of 3 mg/kg i.p. abolished the anti-edematous effect of magnesium sulfate (5 mg/kg), with L-arginine (.4 mg/kg, s.c.) reversing the influence of L-NAME on the effect of magnesium sulfate (Figure 4A). L-NAME at a higher dose of 5 mg/kg increased the anti-edematous effect of magnesium sulfate (5 mg/kg) by 41.2% (dv = .2 ± .1 mL), 22.8% (dv = .4 ± .1 mL), and 25.2% (dv = .6 ± .0 mL) at the 1.5-, 2.5-, 4.5-hour time points, respectively, and L-arginine (.4 mg/kg, s.c.) significantly (P < .05) reduced the effect of L-NAME on the effect of magnesium sulfate by 57.8% (dv = .7 ± .1 mL) at the 2.5 hours time point (Figure 4B). Magnesium sulfate alone at a dose of 5 mg/kg s.c. produced a statistically significant (P < .05) decrease in inflammatory edema of the paw by 34 ± 7.6% (dv = .6 ± .1 mL), 20.1 ± 9.3% (dv = .8 ± .1 mL) and 20.9 ± 3.9% (dv = .9 ± .1 mL) at the 2.5-, 3.5-, and 4.5-hour time points, respectively. When administered alone, L-NAME and L-arginine had no effect on carrageenan-induced paw edema (not shown).

Figure 4.

Time-response curves for the effect of L-NAME (3 or 5 mg/kg) and L-arginine (L-arg. .4 mg/kg) on the effect of prophylactically administered systemic magnesium sulfate (MS 5 mg/kg) in the carrageenan (Carr)-induced hind paw inflammatory edema test. Each point is the mean ± SE of differences between paw volumes in ml (dv). L-arginine significantly decreased the effect of L-NAME on the anti-edematous effect of MS. A – *P < .05, comparison with the curve for L-NAME 3 mg/kg + MS 5 mg/kg; B – ++P < .01, comparison with the curve for .9% NaCl; *P < .05, comparison with the curve for the combination L-NAME 5 mg/kg + MS 5 mg/kg.

The Influence of Neuronal Inhibitor of NOS on the Anti-Edematous Effect of Magnesium Sulfate

L-NPA, a selective nNOS inhibitor, at a dose of 2 mg/kg significantly (P < .01) reduced the anti-edematous effect of magnesium sulfate (5 mg/kg) by 72.3% (dv = 1.0 ± .1 mL) at 4.5 hours, while lower doses of 1 and .5 mg/kg had weak or no influence on the anti-edematous effect of magnesium sulfate (Figure 5). When applied alone, magnesium sulfate (5 mg/kg, s.c.) significantly (P < .05) prevented the development of paw edema by 30.9 ± 4.7% (dv = .6 ± .1 mL) at 4.5 hours. In control rats, L-NPA given alone did not influence (P > .05) paw edema after carrageenan injection (not shown).

Figure 5.

Time-response curves for the effect of L-NPA on the anti-edematous effect of magnesium sulfate (MS) in the carrageenan (Carr)-induced hind paw inflammatory edema test. Results are the mean ± SE of differences between paw volumes in ml (dv). L-NPA (2 mg/kg) significantly reduced the anti-edematous effect of MS 5 mg/kg. *P < .05, comparison with the curve for .9% NaCl; +P < .05, comparison with the curve for MS 5 mg/kg; #P < .05, comparison with the combination L-NPA 2 mg/kg + MS 5 mg/kg.

The Influence of the Inducible Inhibitor of NOS on the Anti-Edematous Effect of Magnesium Sulfate

SMT, a potent and selective iNOS inhibitor, at doses of .005 and .01 mg/kg did not produce any statistically significant (P > .05) outcomes on the anti-edematous effect of magnesium sulfate (5 mg/kg) in carrageenan-induced inflammation. Only at the highest tested dose of .015 mg/kg did SMT significantly (P < .01) abolish (dv = 1.1 ± .1 mL) the anti-edematous effect of magnesium sulfate (dv = .6 ± .1 mL) at 4.5 hours (Figure 6). In control rats, SMT itself (.015 mg/kg) did not have a significant effect (P > .05) on paw edema (not shown).

Figure 6.

Time-response curves for the effect of SMT on the anti-edematous effect of magnesium sulfate (MS) in the carrageenan (Carr)-induced hind paw inflammatory edema test. Results are the mean ± SE of differences between paw volumes in mL (dv). SMT (.015 mg/kg) significantly (*P < .05) reduced the anti-edematous effect of MS 5 mg/kg.

Discussion

This study for the first time shows that (1) systemic administration of magnesium sulfate has therapeutic and slightly less pronounced prophylactic anti-edematous effects on inflammation; (2) local peripheral administration of magnesium sulfate prevents the development of inflammatory edema; (3) the protocol of magnesium use in inflammatory edema can be different; (4) in prophylaxis and treatment with magnesium a better anti-edematous effects in inflammation are achieved after local prophylactic and systemic therapeutic administration; and (5) magnesium partially reduces inflammatory edema via NO production.

These findings are important because they illustrate the impact of timing, dose, and route of magnesium administration in the treatment of acute and local inflammatory edema, which includes both neurogenic and non-neurogenic inflammatory responses.

Inflammatory edema is very common in clinical practice and usually develops after trauma, surgery, and rheumatic diseases. Also, the in vivo model of carrageenan-induced inflammation used in the current study mimics persistent inflammation without injury or damage to the tissue.18 This model is used for the screening of novel anti-inflammatory drugs for rheumatoid arthritis.17 Based on the above data, the clinical significance of this study is that magnesium in doses used for supplementation in humans6 can be effective in reducing inflammatory edema associated with rheumatic diseases.17

Our results show that the peak of the anti-edematous effects of magnesium sulfate after systemic or local applications, as well as after pretreatment and treatment, was about 25–65%, and were registered at the time of maximally developed carrageenan-induced edema. Also, our results indicate that in reducing inflammatory edema, local administration of magnesium is more efficient than systemic administration because the effect is greater and lasts longer. However, systemic magnesium is more effective for treating rather than preventing inflammatory edema, although its effect is short-acting, it amounts to about 50% and is achieved after the administration of one dose of magnesium and without administration other drugs. Also, it is important to note that the systemic anti-edematous doses of magnesium sulfate used in the current study correspond to the human dose used for magnesium supplementation (350 mg/day; Tolerable Upper Intake Level), or are slightly above it, and human equivalent doses are between 1 and 6 mg/kg of body weight.6 The doses of magnesium sulfate used in the present study do not affect motor coordination,5 do not change the serum concentration of magnesium above the reference range,7 and do not cause a toxic increase in plasma magnesium concentration (above 3 mM).19 Also, hypomagnesemia is associated with the onset of inflammation or can worsen it.3 Rats in our laboratory setting have optimal feed and the regular control of blood magnesium concentration; also, we previously showed that rats from our laboratory have a normal basal blood magnesium concentration.7

Although studies suggest that magnesium have anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects,3,13,20,21 to the best of our knowledge, there is only one study of the anti-edematous effect of magnesium in inflammation, and our results are in agreement with Nagai et al,10 who showed that preventive systemic administration of magnesium (Mg2+10–200 mg/L) reduced edema in experimental mycobacteria-induced arthritis. There are, however, some differences between our studies: the type of inflammation (acute vs chronic), the choice of inflammatory substances (carrageenan vs Mycobacterium butyricum), administration of magnesium (s.c. and single administration and per os via drinking water, repeated daily for 42 days), evaluation of dose-dependent vs dose-independent effects.

The mechanisms of action of magnesium in edema are seldom investigated.8,9 The anti-inflammatory effects of magnesium were shown only after magnesium supplementation in rats and humans during hypomagnesemia where magnesium deficiency produces a proinflammatory condition through the release of substance P, the activation of immune cells and release of histamine and cytokines, as well as an increase in the level of NO and reactive oxygen free radicals.3,20 Additionally, magnesium sulfate reduces the production of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin 6 (IL-6) in postoperative patient serum.21 As a natural calcium antagonist, magnesium can limit the intracellular increase in calcium levels and the activation of processes that contribute to inflammation. Some of these mechanisms may have contributed to the development of inflammation induced by carrageenan, and this suggests that magnesium achieves are anti-inflammatory effects in carrageenan-induced inflammation, at least in part through some of these mechanisms.22 The administration of carrageenan into the rat paw leads to the development of edema through the production and release of different proinflammatory mediators in two phases.22-24 In the first hour, vasoactive amines such as histamine, serotonin, and bradykinin are released.23 During the late phase (3 hours after administration of carrageenan), when the edema is maximally developed, prostaglandins, NO and different cytokines are involved.22,24,25 It was in this research that we showed that the systemic anti-edematous effects of magnesium are most pronounced at those time points that correspond to the highest production of NO, and the effects of magnesium decreased and stops afterward. It should be noted once again that in this research we used magnesium as the only drug and administered it in one single dose, which makes the anti-edematous effects of one mineral even more important. Specifically, in our research we investigated the role of NO in the mechanism of the anti-edematous effect of magnesium in inflammation, and the association of the NMDA-NO signaling pathway.

Our results suggest that after systemic administration of magnesium, the anti-edematous effect at least partially occurs through a blockade of the NMDA-dependent mechanism, and after local peripheral administration, the anti-edematous effect is probably achieved by another mechanism. This can be explained by the blockage of NMDA receptors in the spinal cord by NMDA antagonists that results in a peripheral anti-edematous effect, while blockage of these receptors at the site of inflammation has no effect on edema.26-28 Although different NMDA receptor antagonists (dizocilpine, ketamine, dextromethorphan, or memantine) or modulators of the NMDA receptor (zinc) reduce inflammatory edema,16,27,29 this is probably not the main mechanism of the anti-edematous effect of magnesium. This could be explained by our finding that indicates sub-effective doses of NOS inhibitors have no effect, that they potentiate or inhibit the systemic influence on the anti-edematous effects of magnesium sulfate depending on the dose and form of enzyme inhibition, and that the precursor of NO reversed NO production. Since NO production through both nNOS and iNOS is responsible for the anti-edematous effects of systemic magnesium, this suggests that magnesium activated the nitrergic pathway through NMDA-independent mechanism(s). Additionally, dizocilpine exhibits a similar anti-edematous mechanism in inflammation.16 A likely explanation is that as nNOS is a Ca-dependent enzyme, after blockage of the NMDA-nNOS pathway in neurons by magnesium, negative feedback takes over control of the proinflammatory response and increased NO production by nNOS in mast cells and leukocytes.30,31 Additionally, ketamine, an NMDA antagonist, during peripheral inflammation in rats reduces the expression of nNOS and increases the expression of iNOS (which is Ca-independent) in the dorsal horns of the spinal cord.32 Possible additional systemic, and especially local anti-edematous mechanisms of magnesium in inflammation, occur via the production of NO at a local peripheral site since magnesium locally induces the production of NO by nNOS and iNOS33; additionally, locally reduced production of NO at the inflammation site has a proinflammatory effect due to the increased production of histamine, LTB4 and reactive oxygen species,34 and through the action on transient receptor potential cation channel vanilloid type 1 (TRPV1) and ankyrin type 1 (TRPA1) proteins.35-37 To summarize, based in our study, possible anti-inflammatory mechanisms of magnesium actions may be the blocking of NMDA receptors and NMDA-independent NO modulation, as we have shown that the sub-effective doses of L-NAME (a nonselective NOS inhibitor), L-NPA (a selective nNOS inhibitor) and SMT (a potent and selective inhibitor of iNOS) antagonized the anti-edematous effects of magnesium sulfate.

This study has important clinical implications for inflammatory diseases, such as rheumatoid diseases, which is associated with increased NO production, edema and pain. Our data suggest that Mg as the sole drug, in doses used for supplementation in humans and even lower, could be of therapeutic value as an anti-inflammatory drug in the prevention of inflammatory edema after local administration and in treatment after systemic administration. Also, increased NO production by nNOS and iNOS may have immunomodulatory properties in rheumatic diseases.

Conclusions

Magnesium as a dietary supplement and old drug could be a novel, effective and safe drug for prophylaxis and especially in the treatment of edema in somatic inflammation that is not caused by tissue injury or damage. The anti-edematous effects of magnesium are achieved after systemic and local peripheral administration when magnesium is administered as a single drug in a single dose. The mechanism of the anti-edematous effect includes, at least in part, a blockade of NMDA ionotropic receptors and NMDA-independent increased production of NO via both nNOS and iNOS.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the Ministry of Education and Science of the Republic of Serbia (Grant No. 200110).

ORCID iDs

Dragana Srebro https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9680-0840

Katarina Savic Vujovic https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4701-6291

Branislava Medic Brkic https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7012-6766

References

- 1.Nathan C. Points of control in inflammation. Nature. 2002;420(6917):846-852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tandoh A, Danquah CA, Benneh CK, Adongo DW, Boakye-Gyasi E, Woode E. Effect of diclofenac and andrographolide combination on carrageenan-induced paw edema and hyperalgesia in rats. Dose Response. 2022;20(2):15593258221103846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mazur A, Maier JA, Rock E, Gueux E, Nowacki W, Rayssiguier Y. Magnesium and the inflammatory response: Potential physiopathological implications. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;458(1):48-56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Srebro DP, Vučković S, Vujović KS, Prostran M. Anti-hyperalgesic effect of systemic magnesium sulfate in carrageenan-induced inflammatory pain in rats: Influence of the nitric oxide pathway. Magnes Res. 2014;27(2):77-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vuckovic S, Srebro D, Savic Vujovic K, Prostran M. The antinociceptive effects of magnesium sulfate and MK-801 in visceral inflammatory pain model: The role of NO/cGMP/K(+)ATP pathway. Pharm Biol. 2015;53(11):1621-1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Srebro D, Vuckovic S, Milovanovic A, Kosutic J, Vujovic KS, Prostran M. Magnesium in pain research: State of the art. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24(4):424-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Srebro DP, Vučković SM, Dožić IS, et al. Magnesium sulfate reduces formalin-induced orofacial pain in rats with normal magnesium serum levels. Pharmacol Rep. 2018;70(1):81-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shadman J, Sadeghian N, Moradi A, Bohlooli S, Panahpour H. Magnesium sulfate protects blood-brain barrier integrity and reduces brain edema after acute ischemic stroke in rats. Metab Brain Dis. 2019;34(4):1221-1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xiang X, Ji Z, Jiang T, Huang Z, Yan J. Reduced serum magnesium is associated with the occurrence of diabetic macular edema in patients with diabetic retinopathy: A retrospective study. Front Med. 2022;9:923282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagai N, Fukuhata T, Ito Y, Tai H, Hataguchi Y, Nakagawa K. Preventive effect of water containing magnesium ion on paw edema in adjuvant-induced arthritis rat. Biol Pharm Bull. 2007;30(10):1934-1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shimosawa T, Takano K, Ando K, Fujita T. Magnesium inhibits norepinephrine release by blocking N-type calcium channels at peripheral sympathetic nerve endings. Hypertension. 2004;44(6):897-902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guiet-Bara A, Durlach J, Bara M. Magnesium ions and ionic channels: Activation, inhibition or block—a hypothesis. Magnes Res. 2007;20(2):100-106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veronese N, Pizzol D, Smith L, Dominguez LJ, Barbagallo M. Effect of magnesium supplementation on inflammatory parameters: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients. 2022;14(3):679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Freire MA, Guimarães JS, Leal WG, Pereira A. Pain modulation by nitric oxide in the spinal cord. Front Neurosci. 2009;3(2):175-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujii E, Irie K, Uchida Y, Tsukahara F, Muraki T. Possible role of nitric oxide in 5-hydroxytryptamine-induced increase in vascular permeability in mouse skin. Naunyn-Schmiedeberg’s Arch Pharmacol. 1994;350(4):361-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Srebro DP, Vučković S, Milovanović A, Vujović KS, Vučetić Č, Prostran M. Preventive treatment with dizocilpine attenuates oedema in a carrageenan model of inflammation: The interaction of glutamatergic and nitrergic signaling. Inflammopharmacology. 2019;27(1):121-128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otterness IG, Wiseman EH, Gans DJ. A comparison of the carrageenan edema test and ultraviolet light-induced erythema test as predictors of the clinical dose in rheumatoid arthritis. Agents Actions. 1979;9(2):177-183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morris C. Carrageenan-induced paw edema in the rat and mouse. Methods Mol Biol. 2003;225:115-121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Felsby S, Nielsen J, Arendt-Nielsen L, Jensen TS. NMDA receptor blockade in chronic neuropathic pain: A comparison of ketamine and magnesium chloride. Pain. 1996;64(2):283-291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yokoyama T, Oono H, Miyamoto A, Ishiguro S, Nishio A. Magnesium-deficient medium enhances NO production in alveolar macrophages isolated from rats. Life Sci. 2003;72(11):1247-1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aryana P, Rajaei S, Bagheri A, Karimi F, Dabbagh A. Acute effect of intravenous administration of magnesium sulfate on serum levels of interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α in patients undergoing elective coronary bypass graft with cardiopulmonary bypass. Anesth Pain Med. 2014;4(3):e16316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta AK, Parasar D, Sagar A, et al. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory properties of gelsolin in acetic acid induced writhing, tail immersion and carrageenan induced paw edema in mice. PLoS One. 2015;10(8):e0135558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Crunkhorn P, Meacock SC. Mediators of the inflammation induced in the rat paw by carrageenin. Br J Pharmacol. 1971;42(3):392-402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Omote K, Hazama K, Kawamata T, et al. Peripheral nitric oxide in carrageenan-induced inflammation. Brain Res. 2001;912(2):171-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Odabasoglu F, Halici Z, Aygun H, et al. α-Lipoic acid has anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidative properties: An experimental study in rats with carrageenan-induced acute and cotton pellet-induced chronic inflammations. Br J Nutr. 2011;105(1):31-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beirith A, Santos AR, Calixto JB. Mechanisms underlying the nociception and paw oedema caused by injection of glutamate into the mouse paw. Brain Res. 2002;924(2):219-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sawynok J, Reid A. Modulation of formalin-induced behaviors and edema by local and systemic administration of dextromethorphan, memantine and ketamine. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;450(2):153-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zanchet EM, Cury Y. Peripheral tackykinin and excitatory amino acid receptors mediate hyperalgesia induced by Phoneutria nigriventer venom. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;467(1-3):111-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jarosz M, Szkaradek N, Marona H, Nowak G, Młyniec K, Librowski T. Evaluation of anti-inflammatory and ulcerogenic potential of zinc-ibuprofen and zinc-naproxen complexes in rats. Inflammopharmacology. 2017;25(6):653-663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kubes P, Kanwar S, Niu NF, Gaboury JP. Nitric oxide synthesis inhibition induces leukocyte adhesion via superoxide and mast cells. FASEB J. 1993;7(13):1293-1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Masini E, Salvemini D, Pistelli A, Mannaioni PF, Vane JR. Rat mast cells synthesize a nitric oxide like-factor which modulates the release of histamine. Agents Actions. 1991;33(1-2):61-63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Infante C, Díaz M, Hernández A, Constandil L, Pelissier T. Expression of nitric oxide synthase isoforms in the dorsal horn of monoarthritic rats: Effects of competitive and uncompetitive N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonists. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9(3):R53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Srebro DP, Vučković SM, Savić Vujović KR, Prostran MŠ. TRPA1, NMDA receptors and nitric oxide mediate mechanical hyperalgesia induced by local injection of magnesium sulfate into the rat hind paw. Physiol Behav. 2015;139:267-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paul-Clark MJ, Gilroy DW, Willis D, Willoughby DA, Tomlinson A. Nitric oxide synthase inhibitors have opposite effects on acute inflammation depending on their route of administration. J Immunol. 2001;166(2):1169-1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moilanen LJ, Laavola M, Kukkonen M, et al. TRPA1 contributes to the acute inflammatory response and mediates carrageenan-induced paw edema in the mouse. Sci Rep. 2012;2:380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Srebro D, Vučković S, Prostran M. Participation of peripheral TRPV1, TRPV4, TRPA1 and ASIC in a magnesium sulfate-induced local pain model in rat. Neuroscience. 2016;339:1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oliveira PA, de Almeida TB, de Oliveira RG, et al. Evaluation of the antinociceptive and anti-inflammatory activities of piperic acid: Involvement of the cholinergic and vanilloid systems. Eur J Pharmacol. 2018;834:54-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]