Abstract

Evidence that climate change will impact the ecology and evolution of individual plant species is growing. However, little, as yet, is known about how climate change will affect interactions between plants and their pathogens. Climate drivers could affect the physiology, and thus demography, and ultimately evolutionary processes affecting both plant hosts and their pathogens. Because the impacts of climate drivers may operate in different directions at different scales of infection, and, furthermore, may be nonlinear, abstracting across these processes may mis-specify outcomes. Here, we use mechanistic models of plant–pathogen interactions to illustrate how counterintuitive outcomes are possible, and we introduce how such framing may contribute to understanding climate effects on plant–pathogen systems. We discuss the evidence-base derived from wild and agricultural plant–pathogen systems that could inform such models, specifically in the direction of estimates of physiological, demographic and evolutionary responses to climate change. We conclude by providing an overview of knowledge gaps and directions for future research in this important area.

This article is part of the theme issue ‘Infectious disease ecology and evolution in a changing world’.

Keywords: plant pathogen, climate change, mechanistic model

1. Introduction

Plant pathogens exert tremendous influence on both wild and cultivated systems. In wild systems, they moderate the stability of plant communities [1]. They can in equal turns promote species diversity by depressing the fitness of a host species at high densities [2,3] and decrease diversity by devastating hosts with fewer defenses, the latter exemplified by invasive pathogens altering the composition of forests in the eastern United States [4]. Climate change is poised to considerably alter disease dynamics through increased temperatures, altered precipitation patterns and increased extreme weather events. These changes will affect the physiology, epidemiology, demography and evolution of wild plant–pathogen systems in complex ways. Furthermore, climate and weather interact with processes at different scales and steps in plant infection, causing feedbacks that might drive counterintuitive outcomes for plant and pathogen populations. Knowledge of the epidemiological dynamics of plant–pathogen systems is growing, but it still is difficult to predict how climate change will alter the diseases that are so important to ecosystem composition. This question is of clear fundamental and applied importance.

One of the reasons for this knowledge gap is that much of what we know about plant pathogens derives from agriculture and forestry, and this entails a particular agenda and associated set of measurements. Because plant pathogens cause huge losses to food and natural resources in these systems [5,6], control measures often disallow measurement of relevant epidemiological parameters. Furthermore, mechanistic models (also called process-based models) that explicitly capture the steps associated with the process of transmission (i.e. from initial host plant colonization to infection of another plant) necessitate extensive amounts of data. As a result, they are time- and labour-intensive and may not be worth the financial investment in many agricultural systems [7–9]. As a result, mechanistic models have not been as widely adopted, and instead, broad phenomenological characterizations have been widely used. For example, a common approach has been correlating disease incidence with weather variables [10–12], often to create species distribution models [13,14]. These models abstract the intermediate steps of pathogen colonization, such as growth on the plant host and transmission to new hosts (box 1; figure 1). Divergent impacts of climate on different steps in the infection and transmission process could mean that these correlations provide misleading projections of future plant pathogen impacts.

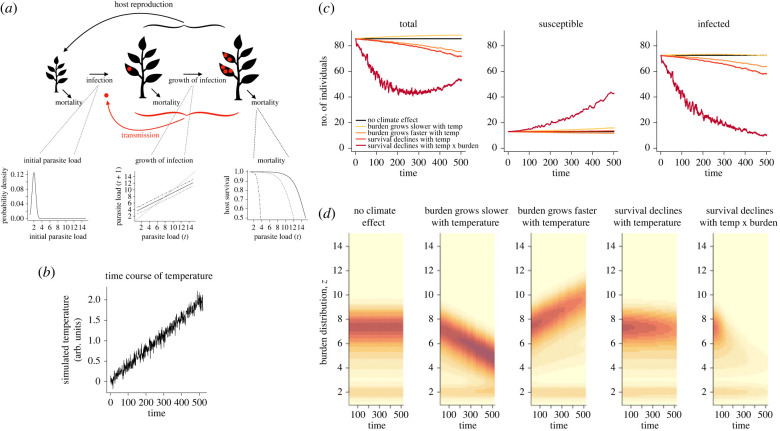

Box 1. A simple model of epidemiological feedbacks in plant pathogens.

Climate drivers can affect both plant host demography and pathogen life cycles via their effects on physiology. Since pathogen spread is shaped by host demography, while host demography responds to pathogen burden, the impacts of climate change on dynamics may be hard to predict. We illustrate this using a toy model of a very simple life history (figure 1a). The host modelled reflects a short-lived aseasonal perennial, and the pathogen is based on a fungal pathogen with frequency-dependent transmission [19] with high initial prevalence and no environmental reservoir. Following germination, a host plant may be infected with a pathogen, with some initial distribution of pathogen material or burden across infected host plants (figure 1b). The burden of the pathogen grows over the course of the plant's life as the pathogen replicates on the host (figure 1c), and we assume that there is no recovery from infection and that plants with higher burdens are more infectious. Host mortality risk increases with increasing disease burden (figure 1d). We can capture this life cycle using a modified integral projection model (IPM) [20]. We assume that host plants do not undergo strong demographic shifts with age or size and that all individuals are capable of reproducing, which they do at rate f. Seedlings recruit with probability , which is set to reflect density dependence in seedling establishment.

Climate drivers may affect many parts of this cycle, for example increasing or decreasing pathogen transmission (if temperature increases the survival of pathogen propagules, for example), or increasing or decreasing the within-host growth of the pathogen, or increasing or decreasing features of host demography. For simplicity, we model a single climatic variable, c, responding to climate change that increases linearly with time (figure 1b). We also do not allow host or pathogen evolution. With S(t) defining susceptible host plant individuals at time t, I(z,t) as infected host plant individuals at time t and with pathogen burden z, the dynamics are captured by

Host demographic rates are reflected in fertility, f, and survival, s(c), where c indicates possible dependence on a climate driver; survival may be further reduced by the burden of the pathogen, and this effect may also be shaped by the climate, a combination captured by the parameter . The force of infection , or rate at which susceptible individuals become infected, is defined by

where is the overall transmission rate, which may also depend on a climate driver c, and is multiplied by the sum of the number of infectious individuals in each class weighted by their burden of infection (), and divided by the total host population size . Qualitatively similar results are obtained by dropping from the denominator, which captures density-dependent transmission. The initial distribution of burden on infection is captured by a normal distribution, (figure 1a panel 1), and growth in the burden defines the number of individuals with burden z’ at t + 1 based on the number of individuals with burden z at t, and how their burden has changed (figure 1a panel 2). We can solve this IPM numerically using the midpoint rule [21] and explore what happens in the circumstance of an increasing climate driver, here referred to as temperature. Parameters and their descriptions are provided in table 1.

To illustrate the role of demographic feedbacks, we explored different scenarios that varied the effects of temperature on pathogen demographic traits (GP), host demographic traits (GH) and the GP × GH interaction. Figure 1c illustrates demographic effects and figure 1d depicts the distribution of disease burden. The first scenario explored is a control where temperature has no effect (figure 1c, black lines). In the second scenario, increasing temperature leads to slower pathogen growth on infected plants (e.g. as in [22]; dotted line on figure 1a) and thus transmission. This situation results in slight growth of the plant population (figure 1c, yellow lines) and a lower average disease burden compared to the control (figure 1d, panel 2). In scenario 3, increasing temperature leads to faster pathogen growth (e.g. as in [23,24]; dot-dash lines on figure 1a, middle and right-hand bottom insets) and thus faster transmission of the pathogen. Faster growth results in more virulent infections (figure 1d, panel 3), which shifts the system to lower prevalence as infected plants have a higher average burden of disease and die more quickly (figure 1c, orange lines). In scenario 4, host survival declines with increasing temperature as heat stress increases background mortality (e.g. as in [25]; dotted line on figure 1d). Population size is further reduced relative to scenario 3, and the prevalence of disease also declines over time (figure 1c, red lines), although the average burden of infected plants remains relatively constant (figure 1, panel 4). In scenario 5, survival declines with increasing temperature and increasing burden (dot-dash line on figure 1a). This might occur if increased temperatures led to decreased disease resistance [26,27] or tolerance [28]. In this situation, the increased mortality causes the host population to crash, leading to a corresponding crash in the parasite population, which allows the host's numbers to rebound (figure 1c, dark red lines).

Figure 1.

(a) Life cycle diagram of the plant where individuals from seeds recruit (black arrows produced by all plants) and then may become infected (red arrow indicates transmission, plots below show the initial distribution of the pathogen burden, z(t), on host plants), after which the burden of infection grows (red dots on the leaves, plot below shows how the pathogen burden grows from z(t) to z(t + 1) in one time step (arbitrary units, e.g. weeks) showing a baseline scenario (solid line), a scenario where temperature increases (dot-dash line) or decreases (dashed line) pathogen burden growth). Throughout, host plants may die (plot to the right shows host survival in one time step, showing a baseline scenario (solid line) and a situation where temperature might decrease survival (dotted line), or decrease survival even more at higher pathogen burdens (dash-dotted line)). (b) Simulated trajectory of a monotonically increasing climate variable such as temperature (arbitrary units) and (c) resulting dynamics of numbers of total, susceptible and infected host plant individuals. (d) Corresponding distribution of burden (z) across infected host plant individuals is shown in the bottom panels for each of the five scenarios, with darker red indicating more individuals. Each panel has a concentration of individuals at the lowest end of the burden scale, indicating newly infected individuals (i.e. following the distribution in (a)) and one around the asymptote of burden growth (intersection of the x = y line and the burden growth curve in (a)). The location of this latter concentration then shifts according to the effects of temperature on the growth of burden, first declining and then increasing (panels 2 and 3), and total number is shaped by survival, e.g. falling off rapidly on the last panel. Parameter values are shown in table 1, and model extensions are delineated in table 2. Time is in arbitrary units. (Figure 1 was created with BioRender.com.)

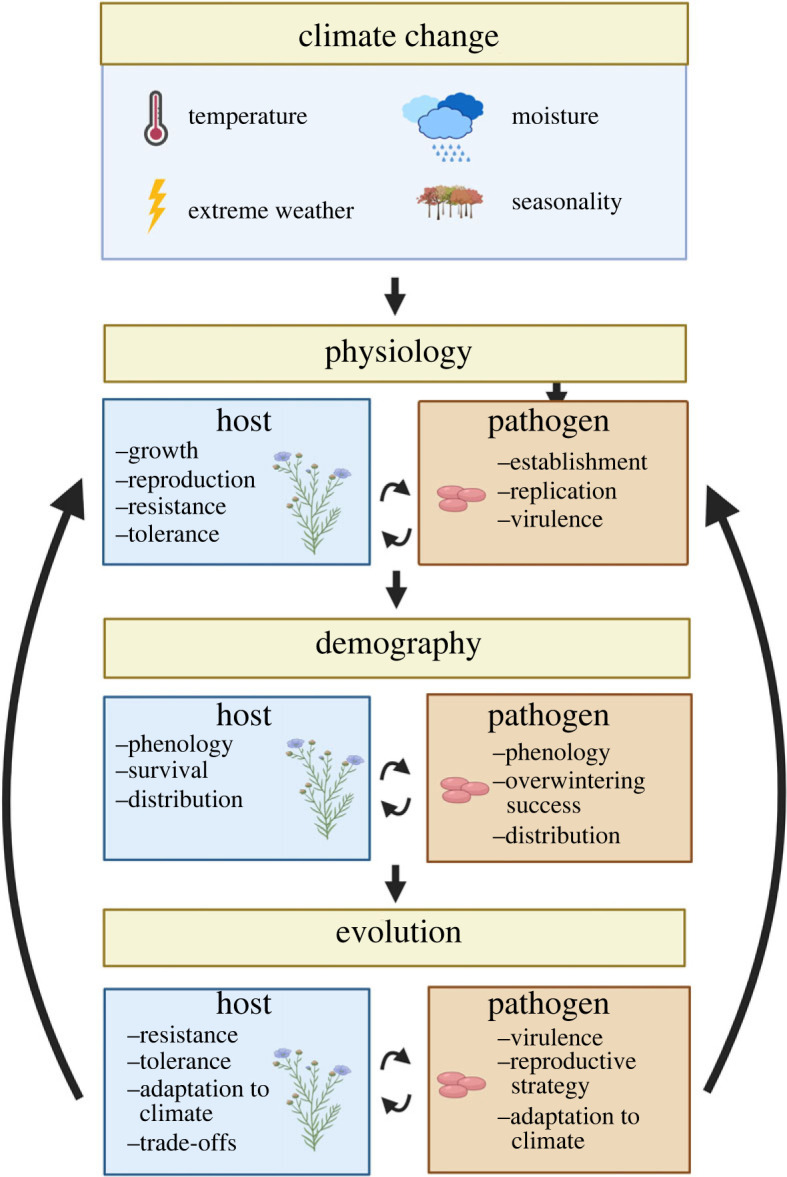

Here, we first introduce how mechanistic models have the potential to change our expectations for dynamics in pathogen systems under climate change relative to models that abstract across the mechanisms of infection. We then present examples, primarily from wild plant–pathogen systems, to illustrate how climate change may alter plant–pathogen epidemiology through changes to physiological, demographic and evolutionary processes (figure 2). We conclude by summarizing the opportunities and challenges of leveraging wild plant–pathogen systems to make better predictions of climate impacts in the long term, of relevance for both natural and agricultural systems.

Figure 2.

Climate drivers and wild plant–pathogen systems. Arrows indicate multiple scales of influence and feedbacks between climate change, physiology, demography and evolution. Climate influences processes at all three scales of plant pathogen epidemiology.

2. Towards mechanistic models for plant–pathogen systems

There is growing evidence that plant diseases operate within the context of a GHxGPxE (host genotype x pathogen genotype × environment) interaction [15]. First conceptualized by the plant pathologist George McNew in what is now known as the ‘disease triangle’ [16], this framework recognizes that the combination of pathogen genetic traits, host genetic traits and environmental context dictates the severity of infection. Work in animal systems has indicated that incorporating GHxGPxE into mechanistic models can alter predictions. For example, Mordecai et al. [17] demonstrated that incorporating the thermal performance of mosquitoes into malaria burden projections under warming temperatures resulted in a much lower estimate for optimal transmission temperature. Another way that encompassing individual-scale mechanisms can alter climate predictions is through resolving contradictions between climate effects on different scales of transmission. Successful infections require multiple connected, sequential steps, and some of these may be facilitated by global change, while others are impeded. This point was illustrated in Shocket et al. [18]. The authors used a trait-based model in a zooplankton–fungus system, finding that increases in transmission rate outweighed spore production decreases to drive projected epidemic size increases under warming.

Similar processes are likely to operate in plant systems. Box 1 demonstrates how different interactions and feedbacks between hosts and pathogens can lead to altered scenarios under climate change that would be missed by larger-scale correlational analyses.

The diversity of outcomes across scenarios in box 1 illustrates the critical need to understand the underlying GHxGPxE interactions in a disease process in order to make accurate predictions of outcomes under climate change. Modelling plant–pathogen interactions as dynamical systems makes feedbacks between hosts, pathogens and the environment explicit. Model development must, of course, be grounded in empirical evidence of the underlying processes. Climate and weather will shape outcomes for plants and pathogens both independently and in combination at three broadly hierarchical scales: physiology, demography and evolution (figure 2), and we use these three scales to consider the available empirical knowledge base. For each, we review examples of how climate impacts on host and pathogen traits can create dynamical feedbacks. We identify key knowledge gaps and discuss ways in which wild plant–pathogen systems could be used to develop expectations for wild and agricultural plant pathogens in a changing climate.

3. Feedbacks between climate, epidemiology and physiology

(a) . Host physiology

Climate change can have a range of impacts on plant physiology. First, it could alter plant growth and reproduction. In general, temperature increases have been shown to accelerate development and cause early senescence, leading to a shorter reproductive window and lower numbers of offspring; to decrease water use efficiency; and to damage plant cells through heat stress [31,32]. High temperature and reduced water availability can also lead to decreases in growth and leaf formation [33]. However, decreases in plant fitness may be offset by greater availability of CO2 and fewer frost events associated with global change. Furthermore, impacts will be species-specific because plants use metabolic pathways with different temperature optima [31].

Host growth and reproduction are tied to epidemiological dynamics across many systems. Miller et al. [34] showed that taller Linum lewisii plants were at greater risk of infection with their fungal pathogen Melampsora lini, likely because they had more susceptible tissue for spores to colonize. Similarly, Susi et al. [35] found that the largest plants in their populations often were repeatedly infected by a rust pathogen over the course of their multi-year study. In some systems, young plants are more susceptible to disease [36], so faster development may decrease this window of increased susceptibility. In vector-borne pathogens, morphological changes to plant and flower structure brought on by climate change may alter vector behaviour, leading to changed disease dynamics. Traits such as flower number and size may make a plant more attractive to a pollinator [37], and there is some evidence that in a pollinator-vectored fungal pathogen system, plants with greater pollen deposition also received more fungal spores borne by their pollinators [38].

Second, climate change has the potential to alter plant immunity. For example, increased temperature has been shown to interfere with effector-triggered immunity, a type of immune response where the plant immune system recognizes pathogen virulence factors, by disrupting cellular signalling [26,27]. As plant growth and reproduction often trade-off with immunity [39–41], plants that have fewer resources due to climate stressors may downregulate their resistance pathways.

(b) . Pathogen physiology

Climate change also is likely to alter many aspects of pathogen physiology. On the most basic level, climate change will alter pathogen establishment and replication. Many pathogens require precise temperature, humidity and nutrient optima for certain parts of their life cycles, especially those that include free-living stages [42]. Pathogens' thermal performance can increase steadily from a minimum temperature to an optimum temperature and then decrease rapidly [43]. Whether this causes a pathogen to spread faster or decline depends on how current temperatures relate to optimum temperatures. For example, Inman et al. [44] found that warmer temperatures increased the infection success of pitch canker on pine trees, but Elmqvist [38] observed ‘heat curing’ of infected plants above a certain temperature threshold in a wild carnation–smut system. Laine [22] showed that pathogens can be locally adapted to temperature, although many fungal populations are characterized by high rates of gene flow between different microclimates, which weakens this adaptation. On the other hand, many pathogens have natural plasticity and genetic variation in thermal performance that may allow them to adapt to changes in temperature. Le May et al. [45] uncovered plasticity in pathogen traits depending on the time of emergence, finding that winter-emerging fungi were more aggressive than genetically similar spring-emerging fungi in their pea–ascochyta blight system.

Temperature is an important variable, but of course it is not the only one undergoing change. Various studies have investigated what impacts other features of global change might have on pathogens. Mitchell & Power [46] found greater foliar fungal pathogen growth when they manipulated plots to match the predictions of elevated CO2 and nitrogen and decreased diversity under climate change. In the pine and pitch canker disease system, Elvira-Recuenco et al. [47] reported that greater moisture levels increased pathogen aggressiveness regardless of the pathogen's genotype.

Additionally, climate change will likely affect pathogen qualitative virulence, otherwise known as infectivity. Some work has shown that environmental factors may be more important than genetic factors in determining pathogen fitness. In a greenhouse inoculation study, Laine [48] found that the relative infectivity and transmission potential of fungal pathogen strains changed with temperature. Furthermore, pathogen replication rate has been shown to negatively covary with infectivity [49], so temperature-induced changes in replication rate may alter the costs and benefits of being able to infect more host genotypes.

Table 1.

Parameters used in the Integral Projection Model. Values shown in square brackets indicate a range of parameter values explored. Code is provided as electronic supplementary material.

| description | parameter symbol | values, relationship |

|---|---|---|

| overall probability of survival in one time step, which may depend on a climate variable c (in the current illustration set to a constant independent of climate for simplicity) | 0.9 | |

| average fertility rate in one time step | 0.4 | |

| probability of seedling establishment, which sets density dependence in the system; recalculated at every time step based on the number of seeds produced and the number of successful seedling recruits in every time step, here set to | ||

| mean and variance of the distribution of burden across hosts at the start of an infection | ||

| distribution of the burden after one time step (), as a function of the growth in the burden () based on intercept and slope , and possible effect of a climate variable c, reflected by the parameter cg and variance around this growth | ||

| survival of infected plants (multiplying overall survival) as a function of disease burden and climate, with an overall intercept , an effect of burden , a direct effect of climate , and an interaction between climate and burden | ||

| magnitude of transmission , potentially climate-dependent | ||

| limits (L = lower and U = upper) and resolution (n = number of bins) of integration of the projection model | ||

Table 2.

Model extensions that encompass more complex pathogen life cycles (noting that expanding host life cycles beyond the aseasonal perennial with no seed bank is described in [29], including monocarpic, multi-stage, etc.). As is generally the case in developing population models (matrix models, IPMs, etc.), the models can only be as good as the data they are founded upon. IPMs may not be the right choice to model pathogen burden if pathogen impacts on the host are effectively binary (presence/absence), or where pathogen burden growth is both small relative to the range of pathogen burden considered and highly variable. In the latter case, the trajectory across pathogen burden classes will be hard to capture using distributions and when numerically solving the Integral Projection Model.

| pathogen life cycle | description of model modifications |

|---|---|

| aseasonal, no environmental reservoir, directly transmitted | As described in Box 1. |

| + environmental reservoir | The model is extended to encompass dynamics of the pathogen load within the environmental reservoir, e.g. with an equation for I(e,t) (as well as existing equations for S(t) and I(z,t)) that contributes to the transmission term, and is depleted by decay out of and augmented by transmission into the environmental reservoir. |

| + seasonality | If seasonality is shaped by climate, climate drivers relevant to the pathogen life cycle (e.g. temperature in Box 1) can be made periodic (as well as non-stationary) reflecting seasonal fluctuations at the desired time-scale. |

| If seasonality is independent of climate, but reflects, e.g. survival as spores over the winter, additional stages can be added to the life cycle (as for the environmental reservoir) but with the model controlling transition between sequences of stages. | |

| If the same driver affects hosts and pathogens but in different ways (e.g. perhaps pathogens are dormant, and thus unaffected during winter, but host survival is affected), this should be modelled separately. | |

| If hosts are annual, then mortality must occur at the end of season and the pathogen re-seeds from the environmental reservoir. | |

| + different scaling of transmission (e.g. density-dependent, frequency-dependent) | Dividing the transmission term by the host population size yields frequency-dependent transmission (the number of new infections per infection is broadly independent of population size), thought to be most appropriate for vector-borne transmission; not doing so captures density-dependent transmission (the number of new infections per infection grows with population size) [30]. In reality, natural systems may be somewhere between the two, which can be captured by raising the denominator to a power. |

4. Feedbacks between climate, epidemiology and demography

The physiological processes described and their dependencies on climate will shape both host and pathogen demographic rates (growth, survival and fertility). Demography in turn defines feedbacks in host–pathogen systems: host demography defines the substrate that pathogens spread on by providing (reproduction) or depleting (mortality) suitable hosts; the latter can also be shaped by pathogen impacts. Climate-driven changes thus have the potential to alter pathogen dynamics both by directly affecting pathogen survival and reproduction, but also indirectly, by affecting host plant life cycles, leading to potentially intricate feedback across scales (box 1) and counterintuitive outcomes.

(a) . Host demography

How climate drivers and pathogens independently affect host demography has been studied in a number of systems. Their combined effects have much more rarely been characterized. Broadly, climate drivers may alter four features of host demography. First, changes in temperature and water availability can shift the seasonal timing of plant life cycle events, or phenology. In temperate regions, spring and summer phases may start earlier in the year, and senescence at the end of the growing season may come later [50]. Plants' growth will be enhanced by longer growing seasons, but pathogens might benefit too, potentially resulting in heavier disease burdens. The overall impact on plant populations will depend on the balance between beneficial growing conditions and higher disease burden.

Second, climate drivers affect host survival [35,51]. Survival is often reduced in harsh conditions such as drought, an effect that might be amplified by disease [52]. Third, fecundity may be affected by both climate and pathogen burden. Unexpected patterns have been reported: Susi et al. [35] found that flax plants that were more heavily infected with the fungus M. lini produced more seeds. Greater recruitment of plants due to disease-amplified seed production and/or reduced competition could tilt populations towards a younger age structure, especially if climate changes also reduce adult plant survival. Conversely, longer growing seasons and higher survival alongside reduced seed production (from disease or climate) could drive impacts in the other direction. Plant survival and reproduction will define population densities, which could also impact disease spread. For example, lower prevalence of disease has been reported in lower-density populations [53].

Finally, both disease and climate have the potential to alter the distribution of plant populations. Climatic conditions [54] and/or pathogen burden [46] may alter the range under which plants flourish, making plant range an emergent property between the interaction between the changing climate and pathogen dispersal. Furthermore, plant range expansions and contractions may alter metapopulation structure, which can affect pathogen transmission dynamics [55] and rates of gene flow between host populations, thus altering their evolutionary potential [56]. Climate change also has the potential to alter host community composition, which relates to disease risk. Halliday et al. [57] showed that along an elevational gradient, higher temperatures led to decreased species richness, which in turn led to increased community disease pressure.

(b) . Pathogen demography

Changes in the phenology of pathogens' life cycles have the potential to greatly alter their population sizes. Longer growing seasons in temperate climates provide more opportunities for pathogen growth, which could allow pathogens to infect more hosts and cause increased severity of disease [58,59]. Additionally, host adaptations to environmental phenology may preclude adaptation to pathogen pressures: for example, in an oak–mildew fungus interaction, the timing of flushing allowed trees to avoid late frosts, but left them more vulnerable to disease [60,61]. Phenological mismatches also have the potential to decrease population sizes of species such as heteroecious rust fungi, which alternate between two very different plant hosts. However, this effect may be tempered by long distance spore dispersal.

Additionally, milder winters may also facilitate persistence of pathogens between seasons [62]. Many plant–pathogen systems are characterized by high pathogen overwintering mortality, meaning that stochastic pathogen extinctions are common, and many populations are recolonized by propagules dispersing from another population [63–65]. If overwintering mortality decreases, it could increase the number of populations where a pathogen persists and the length of the pathogen growing season within those populations. Both of these factors may result in larger pathogen populations, generating more evolutionary potential, which is further discussed below.

5. Feedbacks between climate, epidemiology and evolution

Demography is the engine of evolution [66], and the demographic processes described and their climatic dependencies will also shape evolutionary outcomes. Evolution of both host resistance and pathogen infectivity can occur rapidly in natural plant–pathogen systems [53], feeding back to affect disease spread [67,68]. Moreover, a growing body of work shows that pathogen infectivity and aggressiveness are affected by the interaction of host genotype, pathogen genotype and environment (GHxGPxE; [22,69]). In 2006, Garrett et al. [70] stressed the importance of understanding host and pathogen evolutionary responses to climate change. Yet, evolutionary feedbacks are challenging to study, and few climate models of plant disease in natural populations consider the role of evolution.

Evolutionary response to selection is driven both by the strength of selection and by the evolutionary potential of the population [71], both of which have the potential to be affected by climate change. The strength of selection will be affected by both the incidence and severity of disease, which can shift in response to climate change (see above). Evolutionary potential is influenced by the amount of standing genetic variation for resistance or infectivity, which is influenced by population size, gene flow and breeding system [71,72]. The genetic architecture of resistance and infectivity traits will also affect the evolutionary potential. For example, whether a trait is discrete or polygenic and the degree to which it is correlated, either through pleiotropy, linkage or selection, with other critical fitness traits will affect its evolution. We explore how climate changes may shape plant host and pathogen evolution in turn.

(a) . Host evolution

Genetically based resistance mechanisms play a critical role in determining the epidemic dynamics of disease in natural plant populations. For example, Antonovics [73] found that populations of Silene latifolia with a higher average susceptibility level had consistently higher prevalence of anther-smut disease, and similar findings have been identified in a range of other systems [74–76]. If climate change drives increased levels of pathogen incidence and prevalence, this will increase the strength of selection for host defense mechanisms. If host populations have the capacity to respond to selection, the evolution of host resistance could, in theory, feedback to reduce pathogen pressure. The type of resistance, fitness costs, rate of evolutionary change and pathogen evolutionary potential will determine the impact of evolution on disease transmission and thus the impacts of climate change.

Genetic mechanisms of resistance to pathogens take many forms, including constitutive and induced resistance, qualitative and quantitative resistance, and tolerance. Much has been written about the evolution of these different forms of resistance [77–79], and it is not our intention to review them fully here. However, it is important to point out that these different forms of defense can lead to different epidemic and coevolutionary outcomes. For example, the evolution of qualitative, major gene resistance can strongly reduce disease prevalence [80], but generates strong selection for corresponding pathogen infectivity [81]. By contrast, the evolution of tolerance or quantitative resistance [82] does not have as large an effect on disease prevalence (indeed, tolerance can lead to increased prevalence [83]), but it can reduce the cost of infection to the host and slow the rate of pathogen evolution [82].

The evolution of host resistance is also mediated by the strength of tradeoffs between resistance and other aspects of plant fitness. Stressful abiotic conditions associated with a warming climate may lead to steeper fitness tradeoffs, which could limit the ability of plant populations to evolve higher levels of resistance. For example, Franks [84] found that wild populations of Brassica rapa in southern California evolved an adaptive earlier flowering time in response to a severe drought. However, this also led to an evolved increase in susceptibility to the necrotrophic pathogen Altrenaria brassicae [85]. These studies highlight that changing environmental conditions could exacerbate tradeoffs forcing plants to ‘choose’ between adaptation to abiotic conditions or natural enemies.

Climate-driven changes in host demographics could also affect the evolutionary potential of host populations, e.g. by shrinking or fragmenting host populations and reducing effective population size. For example, Carlsson-Granér & Thrall [56] showed that isolated inland populations of Viscaria alpina in Sweden were more susceptible to anther-smut disease on average than continuous alpine populations that were more well-connected. They hypothesized that higher levels of gene flow and increased population size of the alpine plants facilitated the evolution of resistance. Jousimo et al. [55] report a similar finding in metapopulation of Plantago lanceolata: well-connected populations had higher levels of disease resistance then isolated populations.

(b) . Pathogen evolution

Changing climates will drive pathogen populations to evolve adaptations in response to abiotic factors such as temperature, as well as to changes in host resistance. Genetic variation for infectivity and aggressiveness are well documented in natural populations [86] and rapid evolution of pathogen populations in response to changes in host resistance is commonplace both in agriculture and natural populations [49,68]. Tradeoffs are important in shaping these evolutionary outcomes. In rust fungi, for example, infectivity (the ability to infect a wide range of host genotypes) is negatively correlated with sporulation [49] and latent period [87].

Less well studied is the interaction between thermal optima and infectivity. Are there tradeoffs wherein the evolution of increased thermal tolerance comes at a cost of infectivity or within-host reproduction? One way that this question has been approached has been to collect pathogens from different climates and compare their genetic variation for infectivity against a common set of host genotypes. At a continental scale, Chen et al. [88] compared aggressiveness of Zymoseptoria tritici from five wheat populations spread across three continents on two different cultivars of wheat. They found that pathogen populations from warmer climates had lower lesion growth on a susceptible wheat cultivar than populations from warmer climates, but did not differ in lesion growth on a more resistant wheat cultivar. However, numerous factors differ across continents, including favoured cultivars, growing practices and abundances of other pathogen species, making it difficult to single out temperature as the main driver. We note that this general approach would work well for replicate elevational clines, where pathogens experience significant differences in climates over relatively small geographical distances.

Climate-driven changes in demography also can feedback to affect the evolutionary potential of pathogen populations. For example, longer growing seasons could lead to additional asexual generations in polycyclic pathogens, or greater overwintering survival of sexual spores [62], both of which would increase the effective population size and thus the evolutionary potential of pathogens.

6. Synthesis

Climate change impacts on global weather patterns will alter both wild and agricultural plant–pathogen systems. Predicting the direction of changes is complicated by nonlinearities and feedbacks (box 1) that could lead to deviations from predictions based on phenomenological associations. Mechanistic models reflecting how host genotype, pathogen genotype and the environment interact (GHxGPxE) can be developed from empirical data on wild plant and pathogen physiology, demography and evolutionary responses to climate drivers. Wild systems have considerable potential for describing climate impacts on key aspects of host and pathogen life history without the disruptions to agricultural and forest resources that would be necessary to collect comparable data.

Many challenges remain, and in very few systems have both pathogen and climate interactions been described at any scale. In particular, despite their likely importance given the potential speed of host and pathogen adaptation, quantifying evolutionary responses of resistance and infectivity in response to climate change seems particularly daunting given the array of underlying interactions. Nevertheless, there are many advantages to wild plant systems relative to other systems where the intersection between climate and disease has been tackled. Disease is often visible (e.g. foliar fungal pathogens can be easily detected); reciprocal transplants are relatively straightforward, at least for smaller host species; and both reciprocal transplants and common garden experiments can be used to probe local adaptation of hosts and pathogens to climate variables such as temperature.

The potential applications of a mechanistic approach may be obvious for natural systems such as forests, but what do studies of wild plant pathogens and climate change have to offer agriculture? After all, wild plant disease dynamics are inherently more complicated than those in annual crop systems due to demographic and evolutionary feedbacks, making climate effects more difficult to predict. However, this richer complexity also has the potential to offer insight into climate resiliency that might not be observed in traditional cropping systems. For example, host evolutionary changes in response to temperature and changes in disease pressure are possible in wild systems, and could provide insight for crop breeders dealing with these same challenges. In addition, understanding how seasonal changes and demographic feedbacks drive epidemics in natural populations could also inform planting strategies, such as timing of planting and crop rotations to maximize phenological mismatch for pathogens. In the past, observations that wild plant systems have richer genetic diversity than crop systems led to the development of crop mixture strategies [64,89], an ecological solution that can substantially lower disease spread [90,91]. Just as insights from plant pathology have expanded our knowledge of natural disease systems [16,92], observations from wild plant–pathogen systems may help guide disease management strategies as we chart our way through coping with a warming planet.

Much remains to be done to increase our understanding of plant pathogens. Bacteria and viruses are especially understudied in wild plants because they are harder to detect, and the techniques to observe them have emerged relatively recently [93]. Finally, much of what we know is rooted in temperate climates, and the changes in wild hosts and pathogens associated with changing climatic variables in tropical regions remain critically understudied. Studying the climate-based mechanisms driving changes to physiology, demography and evolution in wild plant–pathogen interactions will increase our understanding of how their epidemiology might change into the future, providing useful insights for agriculture and conservation under climate change.

Data accessibility

The data are provided in the electronic supplementary material [94].

Authors' contributions

J.J.: conceptualization, visualization, writing—original draft and writing—review and editing; I.F.M.: conceptualization, visualization, writing—original draft and writing—review and editing; R.A.: conceptualization and writing—review and editing; E.B.: conceptualization, writing—original draft and writing—review and editing; C.J.E.M.: conceptualization, formal analysis, supervision, visualization and writing—original draft.

All authors gave final approval for publication and agreed to be held accountable for the work performed therein.

Conflict of interest declaration

We declare we have no competing interests.

Funding

C.J.E.M., I.F.M. and J.J. acknowledge funding from the High Meadows Environmental Institute at Princeton University.

Glossary

- Defense:

plant hosts can marshal an array of defenses against pathogens, from macro-scale changes such as closing stomata, through to hardening of cell walls or interfering with pathogen molecular pathways.

- Disease triangle:

a conceptual model used to illustrate that disease is an emergent property of the set of interactions between the environment, the host and the infectious (or in some cases abiotic) agent. This framing echoes the concept denoted by GxGxE interactions.

- GxGxE:

a term capturing the fact that the expression of the disease may vary as a function of the genotype of the host, the genotype of the pathogen and the environmental context.

- Infectivity:

the ability of a pathogen agent to colonize and cause disease in a host, also referred to as ‘qualitative virulence’ (see below).

- Qualitative virulence:

in plant pathology, a pathogenic agent is described as ‘virulent’ when it can cause disease in a host (and is described as ‘avirulent’ otherwise). This is also referred to as a pathogenic agent's ‘infectivity’ (see above). To distinguish this concept from the way the term ‘virulence’ is used in animal pathology (generally capturing the magnitude of harm to the host caused by the pathogen), we distinguish between qualitative virulence (ability to cause harm) and quantitative virulence (magnitude of harm caused).

- Quantitative and qualitative resistance:

a host is considered qualitatively ‘resistant’ when it can entirely exclude a particular pathogen; the variable ability to diminish pathogen replication over the course of the infection can be described as ‘quantitative resistance.’

- Constitutive and induced defense:

Constitutive defenses are always ‘turned on’ and often include structural defenses such as waxy cuticles. Induced defense responses are turned on following contact with a pathogen. Induced defense can be qualitative or quantitative, and vary from highly localized to systemic responses.

- Tolerance:

a host is described as ‘tolerant’ when colonization and replication of a pathogen can occur without the host demonstrating any serious symptoms or death. Tolerance is often framed as an alternative mechanism to resistance in the host arsenal of defenses.

References

- 1.Mordecai EA. 2011. Pathogen impacts on plant communities: unifying theory, concepts, and empirical work. Ecol. Monogr. 81, 429-441. ( 10.1890/10-2241.1) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janzen DH. 1970. Herbivores and the number of tree species in tropical forests. Am. Nat. 104, 501-528. ( 10.1086/282687) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Packer A, Clay K. 2000. Soil pathogens and spatial patterns of seedling mortality in a temperate tree. Nature 404, 278-281. ( 10.1038/35005072) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Woods FW, Shanks RE. 1959. Natural replacement of chestnut by other species in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Ecology 40, 349-361. ( 10.2307/1929751) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Savary S, Willocquet L, Pethybridge SJ, Esker P, McRoberts N, Nelson A. 2019. The global burden of pathogens and pests on major food crops. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 3, 430. ( 10.1038/s41559-018-0793-y) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chakraborty S, Luck J, Hollaway G, Freeman A, Norton R, Garrett KA. 2008. Impacts of global change on diseases of agricultural crops and forest trees. CAB Rev. Perspect. Agricult. Vet. Sci. Nutrit. Natural Resour. 3, 1-15. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Launay M, Caubel J, Bourgeois G, Huard F, de Cortazar-Atauri I G, Bancal MO, Brisson N. 2014. Climatic indicators for crop infection risk: application to climate change impacts on five major foliar fungal diseases in Northern France. Agricult. Ecosyst. Environ. 197, 147-158. ( 10.1016/j.agee.2014.07.020) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pinkard EA, Kriticos DJ, Wardlaw TJ, Carnegie AJ, Leriche A. 2010. Estimating the spatio-temporal risk of disease epidemics using a bioclimatic niche model. Ecol. Model. 221, 2828-2838. ( 10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2010.08.017) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sparks AH, Forbes GA, Hijmans RJ, Garrett KA. 2014. Climate change may have limited effect on global risk of potato late blight. Glob. Change Biol. 20, 3621-3631. ( 10.1111/gcb.12587) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fabre B, Piou D, Desprez-Loustau ML, Marçais B. 2011. Can the emergence of pine Diplodia shoot blight in France be explained by changes in pathogen pressure linked to climate change? Glob. Change Biol. 17, 3218-3227. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02428.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaw MW, Osborne TM. 2011. Geographic distribution of plant pathogens in response to climate change. Plant Pathol. 60, 31-43. ( 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2010.02407.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhan J, Ericson L, Burdon JJ. 2018. Climate change accelerates local disease extinction rates in a long-term wild host–pathogen association. Glob. Change Biol. 24, 3526-3536. ( 10.1111/gcb.14111) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shabani F, Kumar L. 2013. Risk levels of invasive Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. in areas suitable for date palm (Phoenix dactylifera) cultivation under various climate change projections. PLoS ONE 8, e83404. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0083404) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chaloner TM, Gurr SJ, Bebber DP. 2021. Plant pathogen infection risk tracks global crop yields under climate change. Nat. Clim. Change 11, 710-715. ( 10.1038/s41558-021-01104-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolinska J, King KC. 2009. Environment can alter selection in host–parasite interactions. Trends Parasitol. 25, 236-244. ( 10.1016/j.pt.2009.02.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNew G. 1960. The nature, origin, and evolution of parasitism. In Plant pathology: an advanced treatise (eds Horsfall JG, Dimond AE), pp. 19-69. New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mordecai EA, et al. 2013. Optimal temperature for malaria transmission is dramatically lower than previously predicted. Ecol. Lett. 16, 22-30. ( 10.1111/ele.12015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shocket MS, Strauss AT, Hite JL, Šljivar M, Civitello DJ, Duffy MA, Cáceres CE, Hall SR. 2018. Temperature drives epidemics in a zooplankton-fungus disease system: a trait-driven approach points to transmission via host foraging. Am. Nat. 191, 435-451. ( 10.1086/696096) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McCallum H, Barlow N, Hone J. 2002. Modelling transmission: mass action and beyond. Trends Ecol. Evol. 17, 64-65. ( 10.1016/S0169-5347(01)02399-0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Metcalf CJE, Graham AL, Martinez-Bakker M, Childs DZ. 2016. Opportunities and challenges of Integral Projection Models for modelling host–parasite dynamics. J. Anim. Ecol. 85, 343-355. ( 10.1111/1365-2656.12456) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rees M, Childs DZ, Ellner SP. 2014. Building integral projection models: a user's guide. J. Anim. Ecol. 83, 528-545. ( 10.1111/1365-2656.12178) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laine AL. 2008. Temperature-mediated patterns of local adaptation in a natural plant–pathogen metapopulation. Ecol. Lett. 11, 327-337. ( 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2007.01146.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Huot B, et al. 2017. Dual impact of elevated temperature on plant defence and bacterial virulence in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 8, 1808. ( 10.1038/s41467-017-01674-2) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nnadi NE, Carter DA. 2021. Climate change and the emergence of fungal pathogens. PLoS Pathog. 17, e1009503. ( 10.1371/journal.ppat.1009503) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Niu S, Luo Y, Li D, Cao S, Xia J, Li J, Smith MD. 2014. Plant growth and mortality under climatic extremes: an overview. Environ. Exp. Bot. 98, 13-19. ( 10.1016/j.envexpbot.2013.10.004) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Velásquez AC, Castroverde CDM, He SY. 2018. Plant and pathogen warfare under changing climate conditions. Curr. Biol. 28, R619-R634. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2018.03.054) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cheng C, Gao X, Feng B, Sheen J, Shan L, He P. 2013. Plant immune response to pathogens differs with changing temperatures. Nat. Commun. 4, 2530. ( 10.1038/ncomms3530) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kumar R, Mina U, Gogoi R, Bhatia A, Harit RC. 2016. Effect of elevated temperature and carbon dioxide levels on maydis leaf blight disease tolerance attributes in maize. Agricult. Ecosyst. Environ. 231, 98-104. ( 10.1016/j.agee.2016.06.029) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellner SP, Rees M. 2006. Integral projection models for species with complex demography. Am. Nat. 167, 410-428. ( 10.1086/499438) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McCallum H, Barlow N, Hone J. 2001. How should pathogen transmission be modelled? Trends Ecol. Evol. 16, 295-300. ( 10.1016/s0169-5347(01)02144-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lobell DB, Gourdji SM. 2012. The influence of climate change on global crop productivity. Plant Physiol. 160, 1686-1697. ( 10.1104/pp.112.208298) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fahad S, et al. 2017. Crop production under drought and heat stress: plant responses and management options. Front. Plant Sci. 8, 1147. ( 10.3389/fpls.2017.01147) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Assmann SM. 2013. Natural variation in abiotic stress and climate change responses in Arabidopsis: implications for twenty-first-century agriculture. Int. J. Plant Sci. 174, 3-26. ( 10.1086/667798) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Miller IF, Jiranek J, Brownell M, Coffey S, Gray B, Stahl M, Metcalf CJE. 2022. Predicting the effects of climate change on the cross-scale epidemiological dynamics of a fungal plant pathogen. Sci. Rep. 12, 14823. ( 10.1038/s41598-022-18851-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Susi H, Thrall PH, Barrett LG, Burdon JJ. 2017. Local demographic and epidemiological patterns in the Linum marginale–Melampsora lini association: a multi-year study. J. Ecol. 105, 1399-1412. ( 10.1111/1365-2745.12740) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bruns EL, Antonovics J, Carasso V, Hood M. 2017. Transmission and temporal dynamics of anther-smut disease (Microbotryum) on alpine carnation (Dianthus pavonius). J. Ecol. 105, 1413-1424. ( 10.1111/1365-2745.12751) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Conner JK, Rush S. 1996. Effects of flower size and number on pollinator visitation to wild radish, Raphanus raphanistrum. Oecologia 105, 509-516. ( 10.1007/BF00330014) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Elmqvist T, Liu D, Carlsson U, Giles BE. 1993. Anther-smut infection in Silene dioica: variation in floral morphology and patterns of spore deposition. Oikos 68, 207-216. ( 10.2307/3544832) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tian D, Traw MB, Chen JQ, Kreitman M, Bergelson J. 2003. Fitness costs of R-gene-mediated resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nature 423, 74-77. ( 10.1038/nature01588) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Biere A, Antonovics J. 1996. Sex-specific costs of resistance to the fungal pathogen Ustilago violacea (Microbotryum violaceum) in Silene alba. Evolution 50, 1098-1110. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1996.tb02350.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chae E, Tran DT, Weigel D. 2016. Cooperation and conflict in the plant immune system. PLoS Pathog. 12, e1005452. ( 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005452) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Truscott JE, Gilligan CA. 2003. Response of a deterministic epidemiological system to a stochastically varying environment. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 100, 9067-9072. ( 10.1073/pnas.1436273100) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chaloner TM, Gurr SJ, Bebber DP. 2020. Geometry and evolution of the ecological niche in plant-associated microbes. Nat. Commun. 11, 2955. ( 10.1038/s41467-020-16778-5) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Inman AR, Kirkpatrick SC, Gordon TR, Shaw DV. 2008. Limiting effects of low temperature on growth and spore germination in Gibberella circinata, the cause of pitch canker in pine species. Plant Dis. 92, 542-545. ( 10.1094/PDIS-92-4-0542) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Le May C, Guibert M, Leclerc A, Andrivon D, Tivoli B. 2012. A single, plastic population of Mycosphaerella pinodes causes ascochyta blight on winter and spring peas (Pisum sativum) in France. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 8431-8440. ( 10.1128/AEM.01543-12) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mitchell CE, Power AG. 2003. Release of invasive plants from fungal and viral pathogens. Nature 421, 625-627. ( 10.1038/nature01317) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Elvira-Recuenco M, Pando V, Berbegal M, Manzano Muñoz A, Iturritxa E, Raposo R. 2021. Influence of temperature and moisture duration on pathogenic life history traits of predominant haplotypes of Fusarium circinatum on Pinus spp. in Spain. Phytopathology 111, 2002-2009. ( 10.1094/PHYTO-10-20-0445-R) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Laine AL. 2007. Pathogen fitness components and genotypes differ in their sensitivity to nutrient and temperature variation in a wild plant–pathogen association. J. Evol. Biol. 20, 2371-2378. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2007.01406.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thrall PH, Burdon JJ. 2003. Evolution of virulence in a plant host–pathogen metapopulation. Science 299, 1735-1737. ( 10.1126/science.1080070) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Menzel A, Yuan Y, Matiu M, Sparks T, Scheifinger H, Gehrig R, Estrella N. 2020. Climate change fingerprints in recent European plant phenology. Glob. Change Biol. 26, 2599-2612. ( 10.1111/gcb.15000) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Susi H, Sallinen S, Laine AL. 2022. Coinfection with a virus constrains within-host infection load but increases transmission potential of a highly virulent fungal plant pathogen. Ecol. Evol. 12, e8673. ( 10.1002/ece3.8673) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jarosz AM, Burdon JJ. 1992. Host-pathogen interactions in natural populations of Linum marginale and Melampsora lini. Oecologia 89, 53-61. ( 10.1007/BF00319015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Knops JM, et al. 1999. Effects of plant species richness on invasion dynamics, disease outbreaks, insect abundances and diversity. Ecol. Lett. 2, 286-293. ( 10.1046/j.1461-0248.1999.00083.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kelly AE, Goulden ML. 2008. Rapid shifts in plant distribution with recent climate change. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 105, 11 823-11 826. ( 10.1073/pnas.0802891105) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Jousimo J, Tack AJM, Ovaskainen O, Mononen T, Susi H, Tollenaere C, Laine AL. 2014. Ecological and evolutionary effects of fragmentation on infectious disease dynamics. Science 344, 1289-1293. ( 10.1126/science.1253621) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carlsson-Granér U, Thrall PH. 2015. Host resistance and pathogen infectivity in host populations with varying connectivity. Evolution 69, 926-938. ( 10.1111/evo.12631) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Halliday FW, Jalo M, Laine AL. 2021. The effect of host community functional traits on plant disease risk varies along an elevational gradient. eLife 10, e67340. ( 10.7554/eLife.67340) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sturrock RN. 2011. Climate change and forest diseases. Plant Pathol. 60, 133-149. ( 10.1111/j.1365-3059.2010.02406.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kaczmarek J, Kedziora A, Brachaczek A, Latunde-Dada AO, Dakowska S, Karg G, Jedryczka M. 2016. Effect of climate change on sporulation of the teleomorphs of Leptosphaeria species causing stem canker of brassicas. Aerobiologia 32, 39-51. ( 10.1007/s10453-015-9404-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dantec CF, Ducasse H, Capdevielle X, Fabreguettes O, Delzon S, Desprez-Loustau ML. 2015. Escape of spring frost and disease through phenological variations in oak populations along elevation gradients. J. Ecol. 103, 1044-1056. ( 10.1111/1365-2745.12403) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Desprez-Loustau ML, Vitasse Y, Delzon S, Capdevielle X, Marçais B, Kremer A. 2010. Are plant pathogen populations adapted for encounter with their host? A case study of phenological synchrony between oak and an obligate fungal parasite along an altitudinal gradient. J. Evol. Biol. 23, 87-97. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2009.01881.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Penczykowski RM, Walker E, Soubeyrand S, Laine AL. 2015. Linking winter conditions to regional disease dynamics in a wild plant–pathogen metapopulation. New Phytol. 205, 1142-1152. ( 10.1111/nph.13145) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Laine AL, Hanski I. 2006. Large-scale spatial dynamics of a specialist plant pathogen in a fragmented landscape. J. Ecol. 94, 217-226. ( 10.1111/j.1365-2745.2005.01075.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Burdon JJ, Jarosz AM. 1991. Host-pathogen interactions in natural populations of Linum marginale and Melampsora lini: I. patterns of resistance and racial variation in a large host population. Evolution 45, 205-217. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1991.tb05278.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smith DL, Ericson L, Burdon JJ. 2003. Epidemiological patterns at multiple spatial scales: an 11-year study of a Triphragmium ulmariae–Filipendula ulmaria metapopulation. J. Ecol. 91, 890-903. ( 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2003.00811.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Metcalf CJE, Pavard S. 2007. Why evolutionary biologists should be demographers. Trends Ecol. Evol. 22, 205-212. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2006.12.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Thrall PH, Jarosz AM. 1994. Host–pathogen dynamics in experimental populations of Silene alba and Ustilago violacea. I. Ecological and genetic determinants of disease spread. J. Ecol. 82, 549-559. ( 10.2307/2261263) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Thrall PH, Laine AL, Ravensdale M, Nemri A, Dodds PN, Barrett LG, Burdon JJ. 2012. Rapid genetic change underpins antagonistic coevolution in a natural host-pathogen metapopulation. Ecol. Lett. 15, 425-435. ( 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2012.01749.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhan J, McDonald BA. 2011. Thermal adaptation in the fungal pathogen Mycosphaerella graminicola. Mol. Ecol. 20, 1689-1701. ( 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2011.05023.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Garrett KA, Dendy SP, Frank EE, Rouse MN, Travers SE. 2006. Climate change effects on plant disease: genomes to ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 44, 489-509. ( 10.1146/annurev.phyto.44.070505.143420) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.McDonald BA, Linde C. 2002. Pathogen population genetics, evolutionary potential, and durable resistance. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 40, 349-379. ( 10.1146/annurev.phyto.40.120501.101443) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Barrett LG, Thrall PH, Burdon JJ, Linde CC. 2008. Life history determines genetic structure and evolutionary potential of host–parasite interactions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 23, 678-685. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2008.06.017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Antonovics J, Thrall P, Jarosz A, Stratton DA. 1994. Ecological genetics of metapopulations: the Silene-Ustilago plant–pathogen system. In Ecological genetics (ed. Real L), pp. 146-170. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Carlsson-Granér U, Pettersson TM. 2005. Host susceptibility and spread of disease in a metapopulation of Silene dioica. Evol. Ecol. Res. 7, 353-369. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Springer YP. 2007. Clinal resistance structure and pathogen local adaptation in a serpentine flax–flax rust interaction. Evolution 61, 1812-1822. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2007.00156.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gibson AK, Jokela J, Lively CM. 2016. Fine-scale spatial covariation between infection prevalence and susceptibility in a natural population. Am. Nat. 188, 1-14. ( 10.1086/686767) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jones JDG, Dangl JL. 2006. The plant immune system. Nature 444, 323. ( 10.1038/nature05286) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Thompson JN, Burdon JJ. 1992. Gene-for-gene coevolution between plants and parasites. Nature 360, 121-125. ( 10.1038/360121a0) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Poland JA, Balint-Kurti PJ, Wisser RJ, Pratt RC, Nelson RJ. 2009. Shades of gray: the world of quantitative disease resistance. Trends Plant Sci. 14, 21-29. ( 10.1016/j.tplants.2008.10.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Antonovics J, Thrall PH. 1994. The cost of resistance and the maintenance of genetic polymorphism in host–pathogen systems. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 257, 105-110. ( 10.1098/rspb.1994.0101) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tellier A, Brown JKM. 2007. Polymorphism in multilocus host–parasite coevolutionary interactions. Genetics 177, 1777-1790. ( 10.1534/genetics.107.074393) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Fabre F, Burie JB, Ducrot A, Lion S, Richard Q, Djidjou-Demasse R. 2022. An epi-evolutionary model for predicting the adaptation of spore-producing pathogens to quantitative resistance in heterogeneous environments. Evol. Appl. 15, 95-110. ( 10.1111/eva.13328) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Roy BA, Kirchner JW. 2000. Evolutionary dynamics of pathogen resistance and tolerance. Evolution 54, 51-63. ( 10.1111/j.0014-3820.2000.tb00007.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Franks SJ. 2011. Plasticity and evolution in drought avoidance and escape in the annual plant Brassica rapa. New Phytol. 190, 249-257. ( 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03603.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.O'Hara NB, Rest JS, Franks SJ. 2016. Increased susceptibility to fungal disease accompanies adaptation to drought in Brassica rapa. Evolution 70, 241-248. ( 10.1111/evo.12833) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tack AJM, Thrall PH, Barrett LG, Burdon JJ, Laine AL. 2012. Variation in infectivity and aggressiveness in space and time in wild host–pathogen systems: causes and consequences. J. Evol. Biol. 25, 1918-1936. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2012.02588.x) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bruns E, Carson ML, May G. 2014. The jack of all trades is master of none: a pathogen's ability to infect a greater number of host genotypes comes at a cost of delayed reproduction. Evolution 68, 2453-2466. ( 10.1111/evo.12461) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chen F, Duan GH, Li DL, Zhan J. 2017. Host resistance and temperature-dependent evolution of aggressiveness in the plant pathogen Zymoseptoria tritici. Front. Microbiol. 8, 1217. ( 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01217) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Garrett KA, Mundt CC. 1999. Epidemiology in mixed host populations. Phytopathology® 89, 984-990. ( 10.1094/PHYTO.1999.89.11.984) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhu Y, et al. 2000. Genetic diversity and disease control in rice. Nature 406, 718-722. ( 10.1038/35021046) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Gibson AK, Nguyen AE. 2021. Does genetic diversity protect host populations from parasites? A meta-analysis across natural and agricultural systems. Evol. Lett. 5, 16-32. ( 10.1002/evl3.206) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Flor HH. 1956. The complementary genic systems in flax and flax rust. In Advances in genetics (ed. Demerec M), pp. 29-54. New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jones R. 2012. Influence of climate change on plant disease infections and epidemics caused by viruses and bacteria. CAB Rev. Perspect. Agricult. Vet. Sci. Nutrit. Natural Resour. 7, 1-33. ( 10.1079/PAVSNNR20127022) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jiranek J, Miller I, An R, Bruns E, Metcalf CJE. 2023. Mechanistic models to meet the challenge of climate change in plant–pathogen systems. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6360040) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Jiranek J, Miller I, An R, Bruns E, Metcalf CJE. 2023. Mechanistic models to meet the challenge of climate change in plant–pathogen systems. Figshare. ( 10.6084/m9.figshare.c.6360040) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Data Availability Statement

The data are provided in the electronic supplementary material [94].