Abstract

The SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant has continued to evolve. XBB is a recombinant between two BA.2 sublineages, XBB.1 includes the G252V mutation, and XBB.1.5 includes the G252V and F486P mutations. XBB.1.5 has rapidly increased in frequency and has become the dominant virus in New England. The bivalent mRNA vaccine boosters have been shown to increase neutralizing antibody (NAb) titers to multiple variants, but the durability of these responses remains to be determined. We assessed humoral and cellular immune responses in 30 participants who received the bivalent mRNA boosters and performed assays at baseline prior to boosting, at week 3 after boosting, and at month 3 after boosting. Our data demonstrate that XBB.1.5 substantially escapes NAb responses but not T cell responses after bivalent mRNA boosting. NAb titers to XBB.1 and XBB.1.5 were similar, suggesting that the F486P mutation confers greater transmissibility but not increased immune escape. By month 3, NAb titers to XBB.1 and XBB.1.5 declined essentially to baseline levels prior to boosting, while NAb titers to other variants declined less strikingly.

The SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant has continued to evolve. XBB is a recombinant between two BA.2 sublineages, XBB.1 includes the G252V mutation, and XBB.1.5 includes the G252V and F486P mutations (Fig. 1A). XBB.1.5 has rapidly increased in frequency and has become the dominant virus in New England (Fig. S1). The bivalent mRNA vaccine boosters have been shown to increase neutralizing antibody (NAb) titers to multiple variants1–4, but the durability of these responses remains to be determined.

Figure 1. Humoral and cellular immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variants.

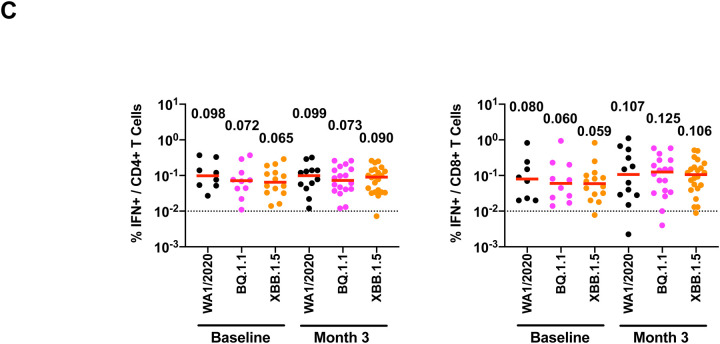

A. Spike sequences for BA.2, BA.5, BQ.1.1, XBB parental sequences BJ.1 (BA.2.10.1) and a sublineage of BA.2.75 (BM.1.1.1), XBB.1, and XBB.1.5 are depicted. Mutations compared with the ancestral WA1/2020 Spike are shown in black, and additional mutations relative to BA.2 are highlighted in colors corresponding to individual variants. For the XBB.1 and XBB.1.5 sequences, black reflects mutations from BA.2, red reflects additional mutations from BJ.1, blue reflects additional mutations from BA.2.75, and green reflects new mutations. NTD, N-terminal domain; RBD, receptor binding domain. B. Neutralizing antibody (NAb) titers against the WA1/2020, BA.2, BA.5, BQ.1.1, XBB.1, and XBB.1.5 variants by luciferase-based pseudovirus neutralization assays at baseline prior to boosting, at week 3 after boosting, and at month 3 after boosting in nucleocapsid seronegative participants. C. Spike-specific, IFN-γ CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses to pooled WA1/2020, BQ.1.1, and XBB.1.5 peptides by intracellular cytokine staining assays at baseline prior to boosting and at month 3 after boosting. Dotted lines reflect limits of quantitation. Medians (red bars) are depicted and shown numerically.

We assessed humoral and cellular immune responses in 30 participants who received the bivalent mRNA boosters and performed assays at baseline prior to boosting, at week 3 after boosting, and at month 3 after boosting (Table S1). By month 3, 43% of participants had a known COVID-19 infection, although we speculate that this represents an underestimate of the true rate of infection. At baseline, median NAb titers to WA1/2020, BA.2, BA.5, BQ.1.1, XBB.1, and XBB.1.5 were 5015, 118, 104, 59, 46, and 74, respectively, in nucleocapsid seronegative participants (Fig. 1B). At week 3, median NAb titers to WA1/2020, BA.2, BA.5, BQ.1.1, XBB.1, and XBB.1.5 were 25,954, 5318, 2285, 379, 125, and 137, respectively (Fig. 1B). At month 3, median NAb titers to WA1/2020, BA.2, BA.5, BQ.1.1, XBB.1, and XBB.1.5 were 21,804, 3996, 1241, 142, 59, and 76, reflecting 1.2-, 1.3-, 1.8-, 2.7-, 2.1-, and 1.8-fold declines from week 3, respectively (Fig. 1B).

Spike-specific T cell responses were assessed by intracellular cytokine staining assays. Median CD4+ T cell responses to WA1/2020, BQ.1.1, and XBB.1.5 were 0.098%, 0.072%, and 0.065% at baseline and 0.099%, 0.073%, and 0.090% at month 3, respectively (Fig. 1C). Median CD8+ T cell responses to WA1/2020, BQ.1.1, and XBB.1.5 were 0.080%, 0.060%, and 0.059% at baseline and 0.107%, 0.125%, and 0.106% at month 3, respectively (Fig. 1C).

Our data demonstrate that XBB.1.5 substantially escapes NAb responses but not T cell responses after bivalent mRNA boosting. NAb titers to XBB.1 and XBB.1.5 were similar, suggesting that the F486P mutation confers greater transmissibility but not increased immune escape. By month 3, NAb titers to XBB.1 and XBB.1.5 declined essentially to baseline levels prior to boosting, while NAb titers to other variants declined less strikingly. The combination of low magnitude and rapidly waning NAb titers to XBB.1.5 will likely reduce the efficacy of the bivalent mRNA boosters5, but cross-reactive T cell responses, which were present prior to boosting, may continue to provide protection against severe disease.

Supplementary Material

Funding

The authors acknowledge NIH grant CA260476, the Massachusetts Consortium for Pathogen Readiness, and the Ragon Institute (D.H.B.), as well as NIH grant AI69309 (A.Y.C.).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Collier AY, Miller J, Hachmann NP, et al. Immunogenicity of BA.5 Bivalent mRNA Vaccine Boosters. N Engl J Med 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miller J, Hachmann NP, Collier AY, et al. Substantial Neutralization Escape by SARS-CoV-2 Omicron Variants BQ.1.1 and XBB.1. N Engl J Med 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang Q, Bowen A, Valdez R, et al. Antibody Response to Omicron BA.4-BA.5 Bivalent Booster. N Engl J Med 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davis-Gardner ME, Lai L, Wali B, et al. Neutralization against BA.2.75.2, BQ.1.1, and XBB from mRNA Bivalent Booster. N Engl J Med 2023;388:183–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Link-Gelles R, Ciesla AA, Fleming-Dutra KE, et al. Effectiveness of Bivalent mRNA Vaccines in Preventing Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection - Increasing Community Access to Testing Program, United States, September-November 2022. MMWR Morbidity and mortality weekly report 2022;71:1526–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.